Descargar con scribd.com

Descargar con docs.google.com

Sumario.-

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

Ständig gegen den Westen protestierend

Gemeinsamkeiten von »konservativen Revolutionären« in Deutschland und russischen Slawophilen

Alexander Krassnov

Ex: http://www.deutsche-stimme.de

Der Konservatismus in Deutschland und Rußland weist eine lange Geschichte der Zusammenarbeit und gemeinsamer Traditionen auf. Ungeachtet aller Unterschiede und fatalen Fehler in der Außenpolitik gab es viele Berührungspunkte rechter Denker beider Völker, z.B. der Kampf gegen den Marxismus und Liberalismus als der beiden wirklich extremistischen Strömungen in der Weltpolitik. Dieser Beitrag spürt dem Einfluß des russischen Dichters Fjodor Dostojewski auf die »konservativen Revolutionäre« Arthur Moeller van den Bruck und Oswald Spengler nach.

Zur Einführung sei ein Zitat aus dem zweiten Band von Oswald Spenglers »Der Untergang des Abendlandes« angeführt, das sich völlig mit den Positionen der russischen Slawophilen von damals und heute deckt. Wenn Spengler über Rußland sprach, stellte er stets Lew Tolstoi und Fjodor Dostojewski gegeneinander. Den ersten Dichterdenker hielt er für einen Repräsentanten des europäisierten Rußlands, den zweiten hingegen für einen Vertreter des uralten und zugleich kommenden Volksrußlands.

So formulierte Oswald Spengler: »Tolstoi ist das vergangene, Dostojewski ist das kommende Rußland. Tolstoi ist mit seinem ganzen Inneren mit dem Westen verbunden. (…) Sein mächtiger Haß redet gegen Europa, von dem er selbst sich nicht befreien kann. Er haßt es in sich, er haßt sich. Er wird damit der Vater des Bolschewismus. (…) Diesen Haß kennt Dostojewski nicht. Er hat alles Westliche mit einer ebenso leidenschaftlichen Liebe umfaßt. Seine Seele ist apokalyptisch, sehnsüchtig, verzweifelt, aber dieser Zukunft gewiß. (…)

Tolstoi ist durchaus ein großer Verstand, ,aufgeklärt‘ und ,sozial gesinnt‘. Alles, was er um sich sieht, nimmt die späte, großstädtische und westliche Form des Problems ein. Jener ist ein Ereignis jenseits der europäischen Zivilisation. Er steht in der Mitte zwischen Peter dem Großen und dem Bolschewismus. Die russische Erde haben sie alle nicht zu Gesicht bekommen. Sein (Tolstois) Haß gegen Besitz ist nationalökonomischer, sein Haß gegen die Gesellschaft sozial-ethischer Natur; sein Haß gegen den Staat ist eine politische Theorie. Daher seine gewaltige Wirkung auf den Westen. Er gehörte irgendwie zu Marx, Ibsen und Zola. Seine Werke sind nicht Evangelien, sondern späte geistige Literatur.

Dostojewski gehört zu niemand, wenn nicht zu den Aposteln des Urchristentums. Dostojewski lebt schon in der Wirklichkeit einer unmittelbar bevorstehenden religiösen Schöpfung. (…) Dostojewski ist ein Heiliger, Tolstoi ist nur Revolutionär. Von ihm allein, dem echten Nachfolger Peters, geht der Bolschewismus aus: nicht das Gegenteil, sondern die letzte Konsequenz des Petrinismus (…) Das Christentum Tolstois war ein Mißverständnis. Er sprach von Christus und meinte Marx. Dem Christentum Dostojewskis gehört das nächste Jahrtausend.«

Diese tiefgründige Gegenüberstellung von Tolstoi und Dostojewski wirft die Frage auf: Woher hat ein deutscher Denker, der ein so fulminantes Werk über den Untergang der abendländischen Zivilisation geschaffen hat, solch eine »slawophilen-übliche« Einstellung zu diesem Problem?

Eine Erklärung: Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts wurden in Deutschland die Werke des Dichters Fjodor Dostojewski geistig entdeckt. Einen entscheidenden Beitrag dazu leistete der herausragende konservativ-revolutionäre Denker Arthur Moeller van den Bruck sowie das Ehepaar Mereschkowski. Dem Ideenkreis der konservativen Revolutionäre gehörte auch Oswald Spengler an. Nicht zuletzt unter dem Einfluß von Dostojewski schrieb Moeller van den Bruck sein berühmtestes Werk »Das dritte Reich« (1923), das zu einem Katechismus der Konservativen Revolution wurde.

Die Idee eines dritten Reiches

Man sollte auch erwähnen, daß die Vision Moellers vom dritten Reich eine bestimmte Verbindung mit den Ideen des russischen Intellektuellen Dimitri Mereschkowski aufwies. Bereits im Jahre 1903 schuf Mereschkowski sein kritisches Werk »Lew Tolstoi und Dostojewski«. Neben einer Analyse des Schaffens und der ethischen Konzepte beider Denker entwickelte er dort seine Vorstellung einer neuen christlichen Besinnung. Das historische Christentum habe in der Religion zu stark das Geistige betont, was zu einer Vernachlässigung des Materiellen geführt habe. Seine Lehre bezeichnete Mereschkowski als »mystischen Materialismus« und plädierte für eine mystische Einigung des Geistigen und des Materiellen. Die Weltgeschichte faßte er dabei im Sinne Hegels als eine dialektische Dreiheit auf, wobei er das Heidentum für eine These und das Christentum für eine Antithese hielt. Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts sollte es nach seiner Meinung zu einer Synthese kommen, deren Realisierung er als eine Art »Drittes Testament« verstand. Das Dritte Testament hielt Mereschkowski für ein neues Religionszeitalter im Leben der ganzen Menschheit.

In seinem Werk schuf Moeller van den Bruck eine ähnliche Triade im Bereich der Politik; er träumte von einem neuen politischen System ohne Linke und ohne Rechte, in dem die Idee des Reiches und die Idee des Menschen verknüpft wären.

In diesem Zusammenhang ist zu betonen, daß die konservativen Revolutionäre in Deutschland eine allgemein positive Einstellung zu Rußland hatten. Ihre russenfreundlichen Aussagen zeugen davon, daß sie im geistigen Leben Rußlands das erraten zu haben glaubten, was wohl keine Umsetzung ihrer Ideale in der Gegenwart verkörperte, aber eine Umsetzung in der Zukunft versprach. Rußlandfreundliche Stimmungen waren in den entsprechenden Denkzirkeln weitverbreitet und beständig, und es läßt sich dies für eines der Hauptmerkmale des revolutionären Konservatismus in Deutschland halten.

Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts nahm der kulturelle Dialog einen besonderen Platz im deutsch-russischen Verhältnis ein. Es war eine Zeit gewaltiger Wandlungen in allen Bereichen des menschlichen Lebens und der Umwertung der Werte in beiden Richtungen. Deshalb ist es kein Zufall, daß viele Vertreter der Konservativen Revolution – neben Moeller van den Bruck und Oswald Spengler auch der frühe Thomas Mann – in ihrem Schaffen einen großen Einfluß russischer Kultur und Literatur, in erster Linie von Dostojewski, verraten. Dank Fjodor Dostojewski kehrten nach Deutschland die Ideen zurück, die einst die Slawophilen von den deutschen Romantikern geerbt hatten. Viele deutsche Konservative, wie z.B. Thomas Mann, haben die antiwestlichen Ideen Dostojewskis ausgedeutet und von Deutschland als von einem Staat geschrieben, der ständig gegen den Westen und dessen Nihilismus protestiert.

Die Publizistik Moellers war von seinem kulturellen und politischen Interesse an den östlichen Nachbarstaaten geprägt. Dieses Interesse hatte mehrere Wurzeln, darunter die außenpolitischen Traditionen Preußens im 19. Jahrhundert sowie die Entgegensetzung der lebendigen Kultur des Ostens und der sterbenden Zivilisation des Westens in den Werken deutscher Kulturphilosophen.

Wenn Moeller über seine Faszination von Dostojewski sprach, redete er ständig über die Jugend des Russentums, das die Kontakte mit seinen Ursprüngen noch nicht verloren habe und voll von schöpferischen Kräften sei. Moellers Propagierung des russischen Genies führte dazu, daß in Deutschland eine Art Dostojewski-Kult entstand. Er beließ es aber nicht bei der Herausgabe der Werke des Russen, sondern interpretierte sie samt der geheimnisvollen russischen Seele. Dies war naheliegend, da Dostojewskis Werke um scharfe Fragen der Freiheit und des Willens, der Gewalt und des Rechtes, des Guten und des Bösen in enger Verbindung mit dem russischen Inneren kreisten. In der Tiefe der russischen Seele erblickte der konservative Revolutionär Spuren einer ständigen Konfrontation mit dem westlichen Einfluß. Russische Literatur widerspiegelte für ihn alles Ursprüngliche, Reingehaltene und Fremde im Gegensatz zur entfremdeten und sterilen Lebenswelt des Westens.

Der Verfasser des »Dritten Reiches« sah in Dostojewskis Werken »die Beschreibung des Lebens, das wir gestern gelebt haben (…) Die von Dostojewski dargestellten Leute sind russische Leute. Aber wir erraten an ihnen vieles von uns selbst.« In diesem Sinne war der russische Schriftsteller ein echter Lehrer für den deutschen konservativen Denker. Moeller van den Bruck, der geistige Leitstern des legendären Juni-Klubs, lernte von dem Russen in erster Linie, an die große Mission seines Volkes zu glauben und dieses als größten Wert zu betrachten.

Absage an westliche »Werte«

Besonders anziehend wirkte an Dostojewski stets seine Ablehnung hohler westlicher »Werte«. Auch Moeller war von der Überzeugung durchdrungen, im Westen sterbe der Volksgeist und das organische Ganze des Volkes. Er behauptete, daß es den Deutschen an russischer Geistigkeit fehle, die Deutschland als Antithese gegen den Westen brauche. Aus Dostojewskis Erbe speiste sich auch die Wahrnehmung Deutschlands als eines stets gegen den Westen protestierenden Landes sowie die Idee der jungen Völker, welche die alten Nationen Europas herausfordern. Die Vorstellung der Slawophilen von der Jugend slawischer Völker verwandelte sich in Moellers Publizistik in die der Jugend des deutschen Volkes. Dabei kritisierte dieser wie die Slawophilen die westlichen »Werte« von Rationalismus, Individualismus und Materialismus. Solche Gegenüberstellung war eine Art kulturkritische Abstraktion des Gegensatzes von Westen und Osten.

Es sei auch erwähnt, daß der Weg Dostojewskis zu den Herzen deutscher Leser gar nicht leicht war. Das Interesse erreichte seinen Höhepunkt, als die Prozesse der gesellschaftlichen Modernisierung in Deutschland immer gewaltiger und schneller wurden. Eine ganze Generation deutscher Neuromantiker nahm den Mystiker aus dem Osten begeistert auf. Seitdem war das Thema Rußland immer häufiger in Kreisen deutscher Intellektueller zu finden. Stephan Zweig sagte zum Beispiel: »Nur über einen deutschen Dostojewski kann die Welt zum russischen Original kommen.« Viele deutsche Schriftsteller – genannt seien nur Friedrich Nietzsche, Rainer Maria Rilke, Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse – bezeichneten die Werke Dostojewskis als die gewaltigste Erfahrung, die ihr Schaffen geprägt habe. Der Kulturphilosoph Oswald Spengler begann sogar unter dem Einfluß seiner Romane die russische Sprache zu lernen.

Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg wurden die Gedanken des Russen über die Rettung Europas durch junge Völker und über Deutschland als ständig gegen den Westen protestierendes Land zu einem der Hauptthemen konservativer deutscher Denker.

Der Einfluß von Dostojewskis russischem Messianismus im Hinblick auf das europäisierte Rußland läßt sich in den Werken Oswald Spenglers und des Panslawisten Nikolaj Danilewski ausmachen. Spenglers Gedanken zu der Pseudomorphose Rußlands unter Peter dem Großen ähneln der Kritik Danilewskis am »Europawahnsinn«, die er in seinem Werk »Rußland und Europa« an die Adresse der russischen Oberschicht richtete. Spengler benannte das Problem so: »Eine zweite Pseudomorphose liegt heute vor unseren Augen: das petrinische Rußland. (…) Auf diese Moskowiterzeit der großen Bojarengeschlechter und Patriarchen, in der beständig eine altrussische Partei gegen die Freunde westlicher Kultur kämpfte, folgt mit der Gründung von Petersburg (1703) die Pseudomorphose, welche die primitive russische Seele erst in die fremden Formen des hohen Barock, dann der Aufklärung, dann des 19. Jahrhunderts zwang. Peter der Große ist das Verhängnis des Russentums geworden. (…)

Der primitive Zarismus von Moskau ist die einzige Form, welche noch heute dem Russentum gemäß ist, aber er ist in Petersburg in die dynastische Form Westeuropas umgefälscht worden. Der Zug nach dem heiligen Süden, nach Byzanz und Jerusalem, der tief in allen rechtgläubigen Seelen lag, wurde in eine weltmännische Diplomatie mit dem Blick nach Westen verwandelt. (…) Ein Volkstum (dessen Bestimmung es war, noch auf Generationen hin geschichtslos zu leben,) wurde in eine künstliche und unechte Geschichte gezwängt, deren Geist vom Urrussentum gar nicht begriffen werden konnte.«

In der Schrift »Preußentum und Sozialismus« ging Spengler – ganz im Sinne der Slawophilen – mit dem »Europawahnsinn« der russischen Oberschicht ins Gericht: »Dies kindlich dumpfe und ahnungsschwere Russentum ist nun von Europa aus durch die aufgezwungenen Formen einer bereits männlich vollendeten, fremden und herrischen Kultur gequält, verstört, verwundet und vergiftet worden. Städte von unserer Art, mit dem Anspruch unserer geistigen Haltung, wurden in das Fleisch dieses Volkstums gebohrt, überreife Denkwesen, Lebensansichten, Staatsideen, Wissenschaften dem unentwickelten Bewußtsein eingeimpft.

Um 1700 drängt Peter der Große dem Volk den politischen Barockstil, Kabinettdiplomatie, Hausmachtpolitik, Verwaltung und Heer nach westlichem Muster auf; um 1800 kommen die diesen Menschen ganz unverständlich englischen Ideen in der Fassung französischer Schriftsteller herüber, um die Köpfe der dünnen Oberschicht zu verwirren; noch vor 1900 führen die Büchernarren der russischen Intelligenz den Marxismus, ein äußerst kompliziertes Produkt westeuropäischer Dialektik, ein, von dessen Hintergründen sie nicht den geringsten Begriff haben. Peter der Große hat das echt russische Zarentum zu einer Großmacht im westlichen Staatssystem umgeformt und damit seine natürliche Entwicklung verdorben, und die Intelligenz, selbst ein Stück des in diesen fremdartigen Städten verdorbenen echt russischen Geistes, verzerrte das primitive Denken des Landes mit seiner dunklen Sehnsucht nach eigenen, in ferner Zukunft liegenden Gestaltungen wie dem Gemeinbesitz von Grund und Boden zu kindischen und leeren Theorien im Geschmack französischer Berufsrevolutionäre.

Petrinismus und Bolschewismus haben gleich sinnlos und verhängnisvoll mißverstandene Schöpfungen des Westens, wie den Hof von Versailles und die Kommune von Paris, dank der unendlichen russischen Demut und Opferfreude in starke Wirklichkeiten umgesetzt.«

Auch in »Preußentum und Sozialismus« wurde der abendländischen Welt die russische entgegengesetzt, und damit die kommende, noch schwer begreifbare Kultur des Ostens positiv von dem in die bloße Zivilisation absinkenden Westen abgesetzt: »Ich habe bis jetzt von Rußland geschwiegen; mit Absicht, denn hier trennen sich nicht zwei Völker, sondern zwei Welten. Die Russen sind überhaupt kein Volk wie das deutsche und englische, sie enthalten die Möglichkeiten vieler Völker der Zukunft in sich, wie die Germanen der Karolingerzeit. Das Russentum ist das Versprechen einer kommenden Kultur, während die Abendschatten über dem Westen länger und länger werden. Die Scheidung zwischen dem russischen und abendländischen Geist kann nicht scharf genug vollzogen werden. Mag der seelische und also der religiöse, politische, wirtschaftliche Gegensatz zwischen Engländern, Deutschen, Amerikanern, Franzosen noch so tief sein, im Vergleich zum Russentum rücken sie sofort zu einer geschlossenen Welt zusammen.«

Spengler war sich sicher, daß das untergehende Abendland durch ein junges Rußland abgelöst werde, obgleich seine mentalen und geographischen Umrisse für ihn noch unklar waren. Er glaubte fest daran, daß europäische Institutionen wie Kapitalismus und Bolschewismus bald an der russischen Kultur zugrundegehen würden.

Diese Hoffnung auf Rettung des je Eigenen gegen die Nivellierungsmacht der westlichen Zivilisation verband die konservativen Revolutionäre in Deutschland mit den Slawophilen in Rußland – eine Ideenverbindung, die heute nötiger denn je ist, um die westlichen Demokraturen geschichtlich entsorgen zu können. Denn wie formulierte der Nationalbolschewist Ernst Niekisch in seinem Beitrag »Revolutionäre Politik« (1926) zeitlos: »Westlerisch sein heißt: mit der Phrase der Freiheit auf Betrug ausgehen, mit dem Bekenntnis zur Menschlichkeit Verbrechen in die Wege leiten, mit dem Aufruf zur Völkerversöhnung Völker zugrunderichten.«

Alexander Krassnov

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, russe, moeller van den bruck, lettres, littérature, littérature russe, lettres russes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

ELEMENTOS Nº 55. EZRA POUND. LOCURA CONTRA LA USURA

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Nouvelle Droite, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, littérature américaine, lettres américaines, ezra pound, nouvelle droite, revue |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://fahrenheit451.hautetfort.com

Pour écrire ce livre, Paolo Rumiz a entrepris un périple original de 33 jours sur plus de 6000 km, à travers 10 pays, en bus, en train, en auto-stop, à pied, simplement muni d’un sac à dos de 6 kilos contenant le strict minimum : de quoi se vêtir et de quoi écrire. Pourquoi alors traverser l’Europe à la verticale, depuis le cap Nord en Norvège jusqu’à Odessa en Ukraine ? Né en 1947 à Trieste, ville carrefour, à cheval entre l’occident et l’orient, aux premières loges des bouleversements géopolitiques des confins de l’Europe, Paolo Rumiz est parti à la recherche de la frontière, cette ligne d'ombre que l’on franchit avec le sentiment de l'interdit, mais aussi à la poursuite de l’âme slave, cette chimère disséminée toujours plus à l’Est.

Pour écrire ce livre, Paolo Rumiz a entrepris un périple original de 33 jours sur plus de 6000 km, à travers 10 pays, en bus, en train, en auto-stop, à pied, simplement muni d’un sac à dos de 6 kilos contenant le strict minimum : de quoi se vêtir et de quoi écrire. Pourquoi alors traverser l’Europe à la verticale, depuis le cap Nord en Norvège jusqu’à Odessa en Ukraine ? Né en 1947 à Trieste, ville carrefour, à cheval entre l’occident et l’orient, aux premières loges des bouleversements géopolitiques des confins de l’Europe, Paolo Rumiz est parti à la recherche de la frontière, cette ligne d'ombre que l’on franchit avec le sentiment de l'interdit, mais aussi à la poursuite de l’âme slave, cette chimère disséminée toujours plus à l’Est.

C’est donc un voyage intéressant qui nous conduit dans ces terres oubliées du tourisme, aux noms exotiques disparus dans le grand chambardement géopolitique du siècle dernier, voire bien avant (Botnie, Livonie, Latgale, Polésie, Carélie, Courlande, Mazurie, Volhynie, Ruthénie, Podolie, Bucovine, Bessarabie, Dobrogée). Tous ces noms à la magie incertaine sont de formidables lieux de rencontres diverses et marquantes qui dessinent par petites touches, par micro récits du quotidien ou du passé, une autre Europe. Voici, les Samis, les derniers pasteurs de rennes dans la péninsule de Kola, le jeune Alexandre, un orphelin au grand coeur qui rentre chez lui après 2 ans de prison, les pélerins ou les moines des îles Solovki et encore tant d’autres.

Il y a dans l’écriture de Paolo Rumiz beaucoup de tendresse et de mélancolie par rapport à ces endroits qu’il traverse et ces personnages qu’il rencontre. On sent qu’il a un amour profond pour cette région du monde, pour le style de vie des personnes qu’il rencontre et pour ce qu’il appelle l'âme slave. Il a envie de montrer à quel point cette âme slave est partie intégrante de l’Europe alors même que cette dernière ne cesse de prendre ses distances avec elle et de la maintenir plus ou moins à l’écart, à sa périphérie. Mais qu’est-ce que cette âme slave au juste ? Difficile à dire exactement. Et c’est peut-être là où le bât blesse avec le livre de Paolo Rumiz.

Ce voyage à la marge de l’Europe finit par être un voyage chez des gens plus ou moins en marge. Paolo Rumiz fait-il l’éloge de la rusticité, de la simplicité, voire du dénuement – pour ne pas utiliser le terme pauvreté? Serait-ce alors ça la fameuse âme slave ? L’âme du pauvre ? Certainement pas, et j’exagère sans doute un peu mais il est clair qu’un certain dégoût de l’Europe occidentale et de son développement est présent de manière plus que diffuse dans le livre. S’il ne s’agissait seulement que de la détestation de l’Europe bureaucratique et de sa forme institutionnelle (UE), passe encore, mais il s’agit de quelque chose de plus viscéral et qui présente le monde ouest-européen comme faux, artificiel, superficiel, chronophage, loin de la nature etc.

Alors quoi, la solution, ce serait pour les autres parties de l’Europe de rester dans cette marge, ce dénuement que Paolo Rumiz décrit durant son périple ? Alors quoi, on ne rencontre pas de gens simples, authentiques, partageant des valeurs de partage, d’empathie en Europe occidentale, admirateurs de la nature (ok, peut-être un peu moins) ? Alors quoi la solution, c’est juste ça ; aller à l’Est, l’âme slave ? Paolo Rumiz n’est certes pas dans une totale idéalisation de cette partie du monde (un peu quand même), mais clairement la violence, le racisme latent, le myticisme inquiétant, le culte de l’argent ou de la fraude ou encore les ravages de l’alcoolisme - pour citer en vrac quelques éléments – ne sont qu’à la périphérie de son propos. Le livre n’avait pas vraiment besoin d’être accompagné de cette sourde antipathie – qui n’est pas une critique – de l’Europe occidentale.

Malgré cet aspect parfois irritant, le livre de paolo Rumiz est intéressant en nous faisant découvrir des contrées peu courues et en revenant sur l’existence de frontières dures, de leurs logiques de mur, de périphérie et d’exclusion dont l’Européen lambda peut avoir de nos jours perdu la notion, la tangibilité.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Voyage | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : italie, voyage, livre, littérature, littérature italienne, lettres, lettres italiennes, paolo rumiz |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

November 1-3, 2013

November 1-3, 2013

Friday, November 1

5:00-7:00 PM - Registration

7:00-10:00 PM - Banquet

Introduction - Richard Spencer

Presidential Address - Paul Gottfried

Life on the Traditionalist Fringe - Tito Perdue

Saturday, November 2nd

9:00-10:15 AM - Panel 1: Decadence and the Family

Moderator: Byron Roth

Dysgenics and Genetic Decline - Henry Harpending

The War on Masculinity and the Traditional Family - Steven Baskerville

10:45 AM – 12:00 PM - Panel 2: Social Decadence

Moderator: Keith Preston

The “Inclusion” Obsession - James Kalb

In Defense of Decadence - Richard Spencer

An Introduction to Decadence - Thomas Bertonneau

12:30-2:00 PM - Lunch

12:30-2:00 PM - Lunch

The Normalization of Perversity - Special Guest

2:30-4:00 PM - Panel 3: Political Decadence

Moderator: Robert Weissberg

Decadence and Democracy - Michael Hart

The End of Citizenship - Carl Horowitz

Politics and Intelligence - John Derbyshire

7:00-10:00 PM - Banquet: Thrown off the Bus

William Regnery, John Derbyshire, Paul Gottfried, Robert Weissberg

Saturday, November 3rd

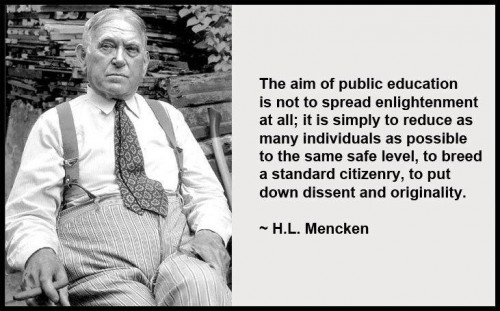

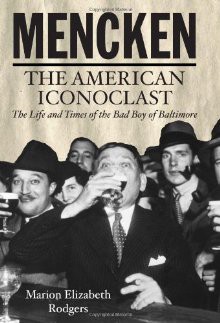

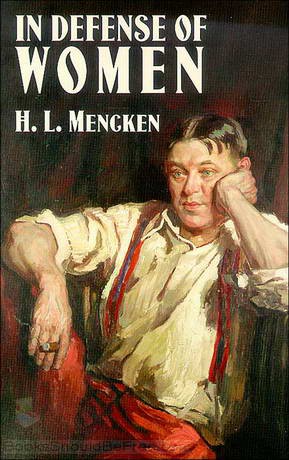

9:00-11:00 AM - Breakfast for H.L. Mencken Club Members Only

Steven Baskerville

Stephen Baskerville is Associate Professor of Government at Patrick Henry College and Research Fellow at the Howard Center for Family, Religion, and Society, the Independent Institute, and the Inter-American Institute. He holds a PhD from the London School of Economics and has taught political science and international affairs at Howard University, Palacky University in the Czech Republic, and most recently as a visiting Fulbright scholar at the Russian National University for the Humanities. More recently, he has turned his full attention to the politics of the family in global perspective, and his most recenty book is Taken Into Custody: The War against Fathers, Marriage, and the Family (Cumberland House, 2007).

Thomas Bertonneau, visiting Professor of English at the State University of New York College, Oswego, New York. He holds a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from UCLA. He has contributed to numerous journals and websites including Alternative Right, and is co-author of The Truth Is Out There: Christian Faith and the Classics of TV Science Fiction.

Thomas Bertonneau

John Derbyshire

John Derbyshire is a mathematician and cultural commentator. He is the author of several other books including Prime Obsession: Bernhard Riemann and the Greatest Unsolved Problem in Mathematics (2003). He writes for VDare.com and TakiMag.com.

Paul Gottfried is the President and Co-founder of the H.L. Mencken Club, and the author of nine books including Leo Strauss and the Conservative Movement in America (2012)

Paul Gottfried

Henry Harpending

Henry Harpending is distinguished professor of anthropology and Thomas Chair at the University of Utah, and co-author of the book The 10,000 Year Explosion (2009). Together with Gregory Cochran, he contributes to the blog “West Hunter“.

Michael Hart is the author of three books on history, various scientific papers, and controversial articles on various other subjects. His best known book is The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History. His most recent book is The Newon Awards: A History of Genius in Science and Technology , published this year by Washington Summit Publishers.

Michael Hart

Carl Horowitz

Carl F. Horowitz is affiliated with the National Legal and Policy Center, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting ethics and accountability in public life. He holds a Ph.D. in urban planning, and specializes in labor, immigration and housing policy issues. Previously, he had been Washington correspondent with Investor’s Business Daily, housing and urban affairs policy analyst with The Heritage Foundation, and assistant professor of urban and regional planning at Virginia Polytechnic Institute.

Jim Kalb is a lawyer (J.D., Yale Law School) and author, The Tyranny of Liberalism: Understanding and Overcoming Administered Freedom, Inquisatorial Tolerance, and Equality by Command (2008). His latest book is Against Inclusiveness: How the Diversity Regime Is Flattening America and the West and What to Do about It .

James Kalb

Tito Perdue

Tito Perdue is the author of several works of fiction. He has been dubbed “one of the most important contemporary Southern writers” by the New York Press, and his iconic character Lee Pefley has been called “a reactionary snob” by Publisher’s Weekly.

Keith Preston is the chief editor of AttacktheSystem.com. He was awarded the 2008 Chris R. Tame Memorial Prize by the United Kingdom’s Libertarian Alliance for his essay, “Free Enterprise: The Antidote to Corporate Plutocracy.”

Keith Preston

William Regnery is the founder of the Charles Martel society, publisher of The Occidental Quarterly and a past chairman of the National Policy Institute, which he co-founded with Sam Francis.

Byron Roth is Professor Emeritus of Psychology, Dowling College and is author, most recently, of The Perils of Diversity: Immigration and Human Nature. His work has appeared in The Journal of Conflict Resolution, The Public Interest, Academic Questions, and Encounter. His books include, Decision Making: Its Logic and Practice, co-authored with John D. Mullen and Prescription for Failure: Race Relations in the Age of Social Science.

Richard Spencer is a former assistant editor at The American Conservative and Executive Editor at Taki’s Magazine (takimag.com); he was the founder and Editor of AlternativeRight.com (2010-2012). Currently, he is President and Director of the National Policy Institute and Washington Summit Publishing and Editor of Radix Journal.

Richard Spencer

Robert Weissberg

Robert Weissberg is author of Pernicious Tolerance and other books including Bad Students, not Bad Schools (2012). He is a Professor Emeritus of Political Science, University of Illinois

00:05 Publié dans Evénement, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, philosophie, lettres, lettres américaines, littérature américaine, h. l. mencken, événement, états-unis |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

par Pierre Lafarge

Ex: http://aucoeurdunationalisme.blogspot.com

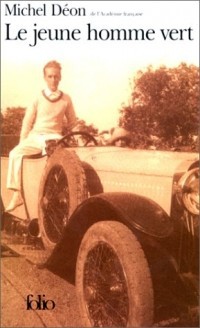

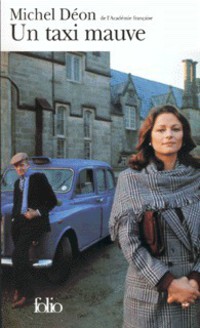

Michel Déon est né en août 1919 à Paris. Il grandit à Monaco où son père, royaliste maurrassien, est directeur de la Sûreté. Ce dernier meurt alors que Déon n’’a que treize ans. Il retourne vivre à Paris avec sa mère et adhère à l’’Action française au lendemain du 6 février 1934. C’’est son condisciple François Perier, le futur acteur, qui lui a vendu la carte. Son bac en poche, Déon s’’inscrit à la faculté de droit et commence à travailler en parallèle à l’’imprimerie de l’AF.

Michel Déon est né en août 1919 à Paris. Il grandit à Monaco où son père, royaliste maurrassien, est directeur de la Sûreté. Ce dernier meurt alors que Déon n’’a que treize ans. Il retourne vivre à Paris avec sa mère et adhère à l’’Action française au lendemain du 6 février 1934. C’’est son condisciple François Perier, le futur acteur, qui lui a vendu la carte. Son bac en poche, Déon s’’inscrit à la faculté de droit et commence à travailler en parallèle à l’’imprimerie de l’AF. Dans ce volume Quarto on trouvera notamment les trois romans les plus importants pour la compréhension des lignes de force de l’œ’œuvre de Déon : Les Poneys sauvages, pour la politique, Un déjeuner de soleil pour le romanesque et La Montée du soir pour l’’ouverture métaphysique. À travers les aventures de trois camarades de collège, de Georges Saval, de Barry Roots et de Horace Mc-Kay, Les Poneys sauvage nous content la confrontation tragique (2) entre l’’Histoire et l’’amitié dans le fracas du XXe siècle, de 1938 et 1968. Horace sera agent secret, Barry, militant communiste, et Georges, grand reporter courant « le monde pour empêcher la bassesse d’’ensevelir les vérités séditieuses » (Vandromme).

Dans ce volume Quarto on trouvera notamment les trois romans les plus importants pour la compréhension des lignes de force de l’œ’œuvre de Déon : Les Poneys sauvages, pour la politique, Un déjeuner de soleil pour le romanesque et La Montée du soir pour l’’ouverture métaphysique. À travers les aventures de trois camarades de collège, de Georges Saval, de Barry Roots et de Horace Mc-Kay, Les Poneys sauvage nous content la confrontation tragique (2) entre l’’Histoire et l’’amitié dans le fracas du XXe siècle, de 1938 et 1968. Horace sera agent secret, Barry, militant communiste, et Georges, grand reporter courant « le monde pour empêcher la bassesse d’’ensevelir les vérités séditieuses » (Vandromme).

Un Déjeuner de soleil, est pour sa part le roman d’’un romancier, la vie imaginaire de l’’écrivain Stanislas Beren. S’’y entremêlent subtilement la vie de Beren, ses œœuvres imaginés et le rythme du siècle, puisque chez Michel Déon on n’’est jamais très loin de l’’actualité. Réalité et imaginaire, par leur proximité, font ici plonger le lecteur au cœœur de la création romanesque.

« Livre quasi-mystique » dira Renaud Matignon de La Montée du soir qui consiste en une approche métaphysique de la vieillesse. Un homme d’’âge mûr voit, en effet, dans ce livre publié en 1987, s’éloigner malgré lui les êtres et les objets qu’’il a aimés. Pol Vandromme a fort justement rapproché ce texte aux accents panthéistes des Quatre nuits de Provence de Maurras. Mais on peut tout autant trouver des accents pascaliens à cette méditation sur les effets du temps.

Grâce et intégrité

Michel Déon a-t-il une postérité littéraire, nous demandera-t-on à juste titre ? Assurément, et dans cette veine nous avouons préférer sans hésitation les romans de Christian Authier à Eric Neuhoff (3). Saluons également à ce propos les travaux de la revue L’’Atelier du roman, dirigée par Lakis Prodigis, qui doit beaucoup à l’’auteur de Je ne veux jamais l’’oublier.

Michel Déon, conciliant grâce et intégrité, est bien de la race de ceux qui depuis deux siècles conservent envers et contre tout une attitude salutaire, parfaitement résumée par Montherlant dans Le Maître de Santiago : « Je ne suis pas de ceux qui aiment leur pays en raison de son indignité. »

Pierre Lafarge

L’’Action Française 2000 du 19 octobre au 1er novembre 2006

* Michel Déon, Œœuvres, Quarto Gallimard, 1372 p., 30 euros.

(1) : Dans son remarquable essai Michel Déon. Le nomade sédentaire, La Table Ronde, 1990.

(2) : Au sens que lui donnait Thierry Maulnier dans son Racine : « La tragédie ne peint pas des êtres : elle révèle des êtres au contact d’’une certaine fatalité. »

(3) : Auteur de Michel Déon, Éd. du Rocher, 1994.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : michel déon, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

10:34 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : revue, littérature, lettres, livr'arbitres |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

por Evgueni Golovín*

Ex: http://paginatransversal.wordpress.com

Muchos libros en nuestro siglo se han escrito sobre la visión del mundo femenina, sobre la psicología femenina y el erotismo femenino. Muy pocos fueron escritos sobre los hombres. Y estos pocos estudios dejan una impresión bastante desoladora. Dos de ellos, escritos por conocidos sociólogos son especialmente sombríos: Paul Duval – “Hombres. El sexo en vías de extinción”, David Riseman – “El mito del hombre en América”. La multitud masculina de rostros variopintos no inspira optimismo. Al contemplar a la multitud masculina uno se entristece: “él”, “ello”, “ellos”… con sus discretos trajes, corbatas mal atadas… sus estereotipados movimientos y gestos están sometidos a la fatal estrategia de la más pulcra pesadilla. Tienen prisa porque “están ocupados”. ¿Ocupados en qué? En conseguir el dinero para sus hembras y los pequeños vampiros que están creciendo.

Muchos libros en nuestro siglo se han escrito sobre la visión del mundo femenina, sobre la psicología femenina y el erotismo femenino. Muy pocos fueron escritos sobre los hombres. Y estos pocos estudios dejan una impresión bastante desoladora. Dos de ellos, escritos por conocidos sociólogos son especialmente sombríos: Paul Duval – “Hombres. El sexo en vías de extinción”, David Riseman – “El mito del hombre en América”. La multitud masculina de rostros variopintos no inspira optimismo. Al contemplar a la multitud masculina uno se entristece: “él”, “ello”, “ellos”… con sus discretos trajes, corbatas mal atadas… sus estereotipados movimientos y gestos están sometidos a la fatal estrategia de la más pulcra pesadilla. Tienen prisa porque “están ocupados”. ¿Ocupados en qué? En conseguir el dinero para sus hembras y los pequeños vampiros que están creciendo.

Son cobardes y por eso les gusta juntarse en manadas. Si prescindimos de las refinadas divagaciones, la cobardía no es más que una tendencia centrípeta, deseo de encontrar un centro seguro y estable. Los hombres tienen miedo de sus propias ideas, de los bandidos, de los jefes, de “la opinión pública”, de las arañas que se chupan el dinero y que lo dan. Pero las mujeres son las que más miedo les dan. “Ella” camina multicolor y bien centrada, su pecho vibra tentadoramente… y los ansiosos ojos siguen sus curvas, y la carne se rebela dolorosamente. Su frialdad – qué desgracia, su compasión erótica – ¡qué felicidad! “Ella” es la materia formada de manera atrayente en este mundo material, en el que vivimos solo una vez, “ella” – es una idea, un ídolo, sus emergentes encantos saltan de los carteles, portadas de revistas y pantallas. “Ella” es un bien concreto. El cuerpo femenino bonito cuesta caro, tal vez más barato que “La maja desnuda” de Goya, pero hay que pagarlo. Una prostituta cobra por horas, la amante o la esposa, naturalmente, piden mucho más. El lema del matrimonio estadounidense es sex for support. Las puertas del paraíso sexual se abren con la llavecita de oro. El cuerpo masculino sin cualificar y sin muscular no vale nada.

La realidad de la civilización burguesa

Aunque nos acusen de cargar las tintas, la situación sigue siendo triste. La igualdad, emancipación, feminismo son los síntomas del creciente dominio femenino, porque la “igualdad de los sexos” no es más que otro fantasma demagógico de turno. El hombre y la mujer debido a la marcada diferencia de su orientación están luchando permanentemente de forma abierta o encubierta, y el carácter del ciclo histórico-social depende del dominio de uno u otro sexo. El hombre por naturaleza es centrípeto, se mueve de izquierda a derecha, hacia adelante, de abajo a arriba. En la mujer es todo al revés. El impulso “puramente masculino” es entregar y apartar, el impulso “puramente femenino” es quitar y conservar. Claro que se trata de impulsos muy esquemáticos, porque cada ser en mayor o menor medida es andrógino, pero está claro que de la ordenación y armonización de estos impulsos depende el bienestar del individuo en particular y de la sociedad en su conjunto, pero semejante armonía es imposible sin la activa irracionalidad del eje del ser, convencimiento intuitivo de la certeza del sistema de valores propios, la instintiva fe en lo acertado del camino propio. De otro modo la energía centrípeta o destrozará al hombre, o le obligará a buscar algún centro y punto de aplicación de sus fuerzas en el mundo exterior. Lo cual lleva a la destrucción de la individualidad y a la total pérdida de control del principio masculino propio. La energía erótica en vez de activar y templar el cuerpo, como ocurre en un organismo normal, comienza a dictar al cuerpo sus propias condiciones vitales.

La androginia del ser está provocada por la presencia femenina en la estructura psicosomática masculina. La “mujer oculta” se manifiesta en el nivel anímico y espiritual como el principio regulador que sujeta o el ideal estrellado del “cielo interior”. El hombre debe mantener la fidelidad hacia esta “bella dama”, la aventura amorosa es la búsqueda de su equivalente terrenal. En el caso contrario estará cometiendo una infidelidad cardinal, existencial.

¿Pero de qué estamos hablando?

Del amor.

La mayoría de los hombres actuales pensarán que se trata de tonterías románticas, que solo valen cuando se habla de los trovadores y caballeros. Oigan, nos dirán, todos nosotros – mujeres y hombres – vivimos en un mundo cruel y tecnificado en condiciones de lucha y competencia. Todos por igual dependemos de estas duras realidades, y en este sentido se puede hablar de la igualdad de los sexos. En cuanto a la dependencia del sexo, sabrá que en todos los tiempos ha habido obsesos y erotómanos. En efecto, las mujeres ahora juegan mucho mayor papel, pero no es suficiente para hablar de no se sabe qué “matriarcado”.

Ciertamente, no se puede hablar del “matriarcado” en la actualidad en el sentido estricto. Según Bachofen, el matriarcado es más bien un concepto jurídico, relacionado con el “derecho de las madres”. Pero perfectamente podemos ocuparnos de la ginecocracia, del dominio de la mujer, debido a la orientación eminentemente femenina de la Historia Moderna. Aquí está la definición de Bachofen:

“El ser ginecocrático es el naturalismo ordenado, el predominio de lo material, la supremacía del desarrollo físico”

J.J. Bachofen. Mutterrecht, 1926, p. 118

Nadie podrá negar el éxito de la Época Moderna en este sentido. A lo largo de los últimos dos siglos en la psicología humana se ha producido un cambio fundamental. De entrada a la naturaleza masculina le son antipáticas las categorías existenciales tales como “la propiedad” y el tiempo en el sentido de “duración”. El carácter centrípeto, explosivo del falicismo exige instantes y “segundos” que están fuera de la “duración”, que no se componen en “duración”. El destino ideal del hombre es avanzar hacia adelante, superar la pesadez terrenal, buscar y conquistar nuevos horizontes del ser, despreciando su vida, si por vida se entiende la existencia homogénea, rutinaria, prolongada en el tiempo. Los valores masculinos son el desinterés, la bondad, el honor, la interpretación celestial de la belleza. Desde este punto de vista, “Lord Jim” de Joseph Conrad es casi la última novela europea sobre un “hombre de verdad”. Jim, simple marinero, ofendido en su honor, no lo puede perdonar, ni superar. Por eso el autor le concedió el título, porque el honor es el privilegio y el valor de la nobleza. El justo y el caballero errante son los auténticos hombres.

Podrán replicar: si todos se ponen a hacer de Quijote o a hablar con los pájaros ¿en qué se convertirá la sociedad humana? Es difícil contestar a esta pregunta, pero es fácil observar en qué se convertiría dicha sociedad sin San Francisco y sin Don Quijote. Don Quijote es mucho más necesario para la sociedad que una docena de consorcios automovilísticos.

La civilización burguesa es medio civilización, es un sinsentido. Para crear la civilización hacen falta los esfuerzos conjuntos de los cuatro estamentos.

Decimos: centralización, centrípeto. Sin embargo no es nada fácil definir el concepto “centro”. El centro puede ser estático o errante, manifestado o no, se puede amarlo u odiarlo, se puede saber de él, o sospechar, o presentirlo con la sutilísima y engañosa antena de la intuición. Es posible haber vivido la vida sin tener ni idea acerca del centro de la existencia propia. Se trata del paradójico e inmóvil móvil de Aristóteles. En el centro coinciden las fuerzas centrífugas y las centrípetas. Cuando una de ellas apaga a la otra el sistema o explota o se detiene en una muerte gélida. Es evidente: lo incognoscible del centro garantiza su centralidad, porque el centro percibido y explicado siempre se arriesga a trasladarse hacia la periferia. De ahí la conclusión: el centro permanente no se puede conocer, hay que creer en él. Por eso Dios, honor, bien, belleza son centros permanentes. Es la condición principal de la actividad masculina dirigida, radial.

En los dos primeros estamentos – el sacerdotal y el de la nobleza – la actividad masculina, entendida de esta forma, domina sobre la femenina. Y únicamente con la posición normal, es decir alta, de estos estamentos se crea la civilización, en todo caso la civilización patriarcal. El burgués reconoce los valores ideales nominalmente, pero prefiere las virtudes más prácticas: el honor se sustituye por la honradez, la justicia por la decencia, el valor por el riesgo razonable. En el burgués la energía centrífuga está sometida a la centrípeta, pero el centro no se encuentra dentro de la esfera de su individualidad, el centro hay que afirmarlo en algún lugar del mundo exterior para convertirse en su satélite. La tendencia de “entregar y apartar” en este caso es posible como una maniobra táctica de la tendencia de “quitar, conservar, adquirir, aumentar”.

Después de la revolución burguesa francesa y la fundación de los estados unidos norteamericanos vino el derrumbe definitivo de la civilización patriarcal. La rebelión de La Vendée, seguramente, fue la última llamarada del fuego sagrado. En el siglo XIX el principio masculino se desperdigó por el mundo orientado hacia lo material, haciéndose notar en el dandismo, en las corrientes artísticas, en el pensamiento filosófico independiente, en las aventuras de los exploradores de los países desconocidos. Pero sus representantes, naturalmente, no podían detener el progreso positivista. La sociedad expresaba la admiración por sus libros, cuadros y hazañas, pero los veía con bastante suspicacia. Marx y Freud contribuyeron bastante al triunfo de la ginecocracia materialista. El primero proclamó la tendencia al bienestar económico como la principal fuerza motriz de la historia, mientras que el segundo expresó la duda global acerca de la salud psíquica de aquellas personas, cuyos intereses espirituales no sirven al “bien común”. Los portadores del auténtico principio masculino paulatinamente se convirtieron en los “hombres sobrantes” al estilo de algunos protagonistas de la literatura rusa. “Wozu ein Dichter?” (¿Para qué el poeta?) – preguntaba Hölderlin con ironía todavía a principios del siglo XIX. Ciertamente ¿para qué hacen falta en una sociedad pragmática los soñadores, los inventores de espejismos, de las doctrinas peligrosas y demás maestros de la presencia inquietante? Gotfied Benn reflejó la situación con exactitud en su maravilloso ensayo “Palas Atenea”:

“… representantes de un sexo que se está muriendo, útiles tan solo en su calidad de copartícipes en la apertura de las puertas del nacimiento… Ellos intentan conquistar la autonomía con sus sistemas, sus ilusiones negativas o contradictorias – todos estos lamas, budas, reyes divinos, santos y salvadores, quienes en realidad nunca han salvado a nadie, ni a nada – todos estos hombres trágicos, solitarios, ajenos a lo material, sordos ante la secreta llamada de la madre-tierra, lúgubres caminantes… En los estados de alta organización social, en los estados de duras alas, donde todo acaba en la normalidad con el apareamiento, los odian y toleran tan solo hasta que llegue el momento”.

Los estados de los insectos, sociedades de abejas y termitas están perfectamente organizados para los seres que “solo viven una vez”. La civilización occidental muy exitosamente se dirige hacia semejante orden ideal y en este sentido representa un episodio bastante raro en la historia. Es difícil encontrar en el pasado abarcable una formación humana, afianzada sobre las bases del ateísmo y una construcción estrictamente material del universo. Aquí no importa qué es lo que se coloca exactamente como la piedra angular: el materialismo vulgar o el materialismo dialéctico o los procesos microfísicos paradójicos. Cuando la religión se reduce al moralismo, cuando la alegría del ser se reduce a una decena de primitivos “placeres”, por los que además hay que pagar ni se sabe cuánto, cuando la muerte física aparece como “el final del todo” ¿acaso se puede hablar del impulso irracional y de la sublimación? Por eso en los años veinte Max Scheler ha desarrollado su conocida tesis sobre la “resublimación” como una de las principales tendencias del siglo. Según Scheler la joven generación ya no desea, a la manera de sus padres y abuelos, gastar las fuerzas en las improductivas búsquedas del absoluto: continuas especulaciones intelectuales exigen demasiada energía vital, que es mucho más práctico utilizar para la mejora de las condiciones concretas corporales, financieras y demás. Los hombres actuales ansían la ingenuidad, despreocupación, deporte, desean prolongar la juventud. El famoso filósofo Scheler, al parecer, saludaba semejante tendencia. ¡Si viera en lo que se ha convertido ahora este joven y empeñado en rejuvenecerse rebaño y de paso contemplara en lo que se ha convertido el deporte y otros entretenimientos saludables!

Y además.

¿Acaso la sublimación se reduce a las especulaciones intelectuales? ¿Acaso el impulso hacia adelante y hacia lo alto se reduce a los saltos de longitud y de altitud? La sublimación no se realiza en los minutos del buen estado de humor y no se acaba con la flojera. Tampoco es el éxtasis. Es un trabajo permanente y dinámico del alma para ampliar la percepción y transformar el cuerpo, es el conocimiento del mundo y de los mundos, atormentado aprendizaje del alpinismo celestial. Y además se trata de un proceso natural.

Si un hombre tiene miedo, rehúye o ni siquiera reconoce la llamada de la sublimación, es que, propiamente, no puede llamarse hombre, es decir un ser con un sistema irracional de valores marcadamente pronunciado. Incluso con la barba canosa o los bíceps imponentes seguirá siendo un niño, que depende totalmente de los caprichos de la “gran madre”. Obligando el espíritu a resolver los problemas pragmáticos, agotando el alma con la vanidad y la lascivia, siempre se arrastrará hasta sus rodillas buscando la consolación, los ánimos y el cariño.

Pero la “gran madre” no es en absoluto la amorosa Eva patriarcal, carne de la carne del hombre, es la siniestra creación de la eterna oscuridad, pariente próxima del caos primordial, no creado: bajo el nombre de Afrodita Pandemos envenena la sangre masculina con la pesadilla sexual, con el nombre de Cibeles le amenaza con la castración, la locura y le arrastra al suicidio. Algunos se preguntarán ¿qué relación tiene toda esta mitología con el conocimiento racional y ateísta? La más directa. El ateísmo no es más que una forma de teología negativa, asimilada de manera poco crítica o incluso inconsciente. El ateo cree ingenuamente en el poder total de la razón como instrumento fálico, capaz de penetrar hasta donde se quiera en las profundidades de la “madre-naturaleza”. Sucesivamente admirando la “sorprendente armonía que reina en la naturaleza” e indignándose ante las “fuerzas elementales, ciegas de la naturaleza” es como un niño mimado que quiere recibir de ella todo sin dar nada a cambio. Aunque últimamente, asustado ante las catástrofes ecológicas y la perspectiva de ser trasladado en un futuro próximo a las hospitalarias superficies de otros planetas, apela a la compasión y el humanismo.

Pero el “sol de la razón” no es más que el fuego fatuo del pantano y el instrumento fálico no es más que un juguete en las depredadoras manos de la “gran madre”. No se debe acercar al principio femenino que crea y que también mata con la misma intensidad. “Dama Natura” exige mantener la distancia y la veneración. Lo entendían bien nuestros patriarcales antepasados, teniendo cuidado de no inventar el automóvil, ni la bomba atómica, que ponían en los caminos la imagen del dios Término y escribían en las columnas de Hércules “non plus ultra”.

El espíritu se despierta en el hombre bruscamente y este proceso es duro, – esta es la tesis principal de Erich Neumann, un original seguidor de Jung, en su “Historia de la aparición de la conciencia”. El mundo orientado ginecocráticamente odia estas manifestaciones y procura acabar con ellas utilizando diferentes métodos. Lo que en la época moderna se entiende por “espiritualidad”, destaca por sus características específicamente femeninas: hacen falta memoria, erudición, conocimientos serios, profundos, un estudio pormenorizado del material – en una palabra, todo lo que se puede conseguir en las bibliotecas, archivos, museos, donde, cual si fuera el baúl de la vieja, se guardan todas las bagatelas. Si alguien se rebela contra semejante espiritualidad, siempre podrán acusarlo de ligereza, superficialidad, diletantismo, aventurerismo – características esencialmente masculinas. De aquí los degradantes compromisos y el miedo del individuo ante las leyes ginecocráticas del mundo exterior, que la psicología profunda en general y Erich Neumann en particular denominan el “miedo ante la castración”. “Tendencia a resistir, – escribe Erich Neumann, – el miedo ante la “gran madre”, miedo ante la castración son los primeros síntomas del rumbo centrípeto tomado y de la autoformación”. Y continúa:

“La superación del miedo ante la castración es el primer éxito en la superación del dominio de la materia”.

Erich Neumann. Urspruggeschichte des Bewusstseins, Munchen, 1975, p. 83

Ahora, en la era de la ginecocracia, semejante concepción constituye en verdad un acto heroico. Pero el “auténtico hombre” no tiene otro camino. Leamos unas líneas de Gotfried Benn del ya citado ensayo:

“De los procesos históricos y materiales sin sentido surge la nueva realidad, creada por la exigencia del paradigma eidético, segunda realidad, elaborada por la acción de la decisión intelectual. No existe el camino de retorno. Rezos a Ishtar, retournons a la grand mere, invocaciones al reino de la madre, entronización de Gretchen sobre Nietzsche – todo es inútil: no volveremos al estado natural”.

¿Es así?

Por un lado: conocimiento dulce, embriagador: sus vibraciones, movimientos gráciles, zonas erógenas… paraíso sexual.

Por el otro:

“Atenas, nacida de la sien de Zeus, de ojos azules, resplandeciente armadura, diosa nacida sin madre. Palas – la alegría del combate y la destrucción, cabeza de Medusa en su escudo, sobre su cabeza el lúgubre pájaro nocturno; retrocede un poco y de golpe levanta la gigantesca piedra que servía de linde – contra Marte, quien está del lado de Troya, de Helena… Palas, siempre con su casco, no fecundada, diosa sin hijos, fría y solitaria”.

1 de enero de 1999.

* Evgueni Golovín (1938-2010) fue un genio inclasificable. Situado completamente fuera del mundo actual, cuya legitimidad rechazaba de plano. “Quien camina contra el día no debe temer a la noche” – era su lema vital. Profundo conocedor de alquimia y de tradición hermética europea, también era especialista en los “autores malditos” franceses, románticos y expresionistas alemanes, traductor de libros de escritores europeos cuya obra está catalogada como “de la presencia inquietante”. Su identificación con el mundo pagano griego llegó al punto de que algunos que le conocieron íntimamente llegaron a definirlo como “Divinidad” (para empezar por el principio, Golovín aprendió el griego a los 16 años y comenzó con la lectura de Homero). En los años 60 del siglo pasado se convirtió en la figura más carismática de la llamada “clandestinidad mística moscovita”, conocido como “Almirante” (de la flotilla hermética, formada por los “místicos”). Fue el primero en la URSS en difundir la obra de autores tradicionalistas como Guénon y Évola. Ya en los años 90 y 2000 redactó la revista Splendor Solis, publicó varios libros y una recopilación de sus poemas. Veía con recelo las doctrinas orientales que consideraba poco adecuadas para el hombre europeo. Y, sobre todo, nunca buscó el centro de gravedad del ser en el mundo exterior. En su “navegación” sin fin siempre se mantuvo firmemente anclado a su interiore terra. El encuentro con Evgueni Golovín, en distintas etapas de sus vidas, fue decisivo para la formación de futuras figuras clave en la vida intelectual rusa como Geidar Dzhemal o

Alexandr Duguin

24/08/2012

Fuente: Poistine.com

(Traducido del ruso por Arturo Marián Llanos)

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : evgueni golovin, russie, littérature, littérature russe, lettres, lettres russes, traditions, gynécocratie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Jünger und Mohler

Karlheinz Weißmann

Ex: http://www.sezession.de

Die Beziehung zwischen Ernst Jünger und Armin Mohler hat sich über mehr als fünf Jahrzehnte erstreckt. Sie wird – wenn in der Literatur erwähnt – als Teil der Biographie Jüngers behandelt. Man hebt auf Mohlers Arbeit als Jüngers Sekretär ab und gelegentlich auf das Zerwürfnis zwischen beiden. Mit den Wilflinger Jahren hatte dieser Streit nichts zu tun. Seine Ursache waren Meinungsverschiedenheiten über die erste Ausgabe der Werke Jüngers. Der Konflikt beendete für lange das Gespräch der beiden, das mit einer Korrespondenz begonnen hatte, im direkten Austausch und dann wieder im – manchmal täglichen – Briefwechsel zwischen der Oberförsterei und dem neuen französischen Domizil Mohlers in Bourg-la-Reine fortgesetzt wurde. Von 1949, als Mohler seinen Posten in Ravensburg antrat, bis 1955, als Jünger seinen 60. Geburtstag feierte, war ihre Verbindung am intensivsten, aber es gab auch eine Vor- und eine Nachgeschichte von Bedeutung.

Die Beziehung zwischen Ernst Jünger und Armin Mohler hat sich über mehr als fünf Jahrzehnte erstreckt. Sie wird – wenn in der Literatur erwähnt – als Teil der Biographie Jüngers behandelt. Man hebt auf Mohlers Arbeit als Jüngers Sekretär ab und gelegentlich auf das Zerwürfnis zwischen beiden. Mit den Wilflinger Jahren hatte dieser Streit nichts zu tun. Seine Ursache waren Meinungsverschiedenheiten über die erste Ausgabe der Werke Jüngers. Der Konflikt beendete für lange das Gespräch der beiden, das mit einer Korrespondenz begonnen hatte, im direkten Austausch und dann wieder im – manchmal täglichen – Briefwechsel zwischen der Oberförsterei und dem neuen französischen Domizil Mohlers in Bourg-la-Reine fortgesetzt wurde. Von 1949, als Mohler seinen Posten in Ravensburg antrat, bis 1955, als Jünger seinen 60. Geburtstag feierte, war ihre Verbindung am intensivsten, aber es gab auch eine Vor- und eine Nachgeschichte von Bedeutung.

Die Vorgeschichte hängt zusammen mit Mohlers abenteuerlichem Grenzübertritt vom Februar 1942. Er selbst hat für den Entschluß, aus der Schweizer Heimat ins Reich zu gehen und sich freiwillig zur Waffen-SS zu melden, zwei Motive angegeben: die Nachrichten von der Ostfront, damit verknüpft das Empfinden, hier gehe es um das Schicksal Deutschlands, und die Lektüre von Jüngers Arbeiter. Die Verknüpfung mag heute irritieren, der Eindruck würde sich aber bei genauerer Untersuchung der Wirkungsgeschichte Jüngers verlieren. Denn, was er im Schlußkapitel des Arbeiters über den „Eintritt in den imperialen Raum“ gesagt hatte, war mit einem Imperativ verknüpft gewesen: „Nicht anders als mit Ergriffenheit kann man den Menschen betrachten, wie er inmitten chaotischer Zonen an der Stählung der Waffen und Herzen beschäftigt ist, und wie er auf den Ausweg des Glückes zu verzichten weiß. Hier Anteil und Dienst zu nehmen: das ist die Aufgabe, die von uns erwartet wird.“

Mohlers Absicht war eben: „Anteil und Dienst zu nehmen“. Es ging ihm nicht um „deutsche Spiele“, nicht um eine Wiederholung von Jüngers Abenteuer in der Fremdenlegion, sondern darum, in einer für ihn bezeichnenden Weise, Ernst zu machen. Daß daraus nichts wurde, hatte dann – auch in einer für ihn bezeichnenden Weise – mit romantischen Impulsen zu tun: der Sehnsucht nach intensiver Erfahrung, nach großen Gefühlen, dem „Bedürfnis nach Monumentalität“, ein Diktum des Architekturtheoretikers Sigfried Giedion, das Mohler häufig zitierte. Daß der nationalsozialistische „Kommissarstaat“ kein Interesse hatte, solches Bedürfnis abzusättigen, mußte Mohler rasch erkennen. Er zog sein Gesuch zurück und ging bis Dezember 1942 zum Studium nach Berlin. Dort saß er im Seminar von Wilhelm Pinder und hörte Kunstgeschichte. Vor allem aber verbrachte er Stunde um Stunde in der Staatsbibliothek, wo er seltene Schriften der „Konservativen Revolution“ exzerpierte oder abschrieb, darunter die von ihm als „Manifeste“ bezeichneten Aufsätze Jüngers aus den nationalrevolutionären Blättern. Dieser Textkorpus bildete neben dem Arbeiter, der ersten Fassung des Abenteuerlichen Herzens sowie Blätter und Steine die Grundlage für Mohlers Faszination an Jünger.

Zehn Jahre später schrieb er über die Wirkung des Autors Jünger auf den Leser Mohler: „Sein Stil könnte mit seiner Oberfläche auf mathematische Genauigkeit schließen lassen. Aber diese Gestanztheit ist Notwehr. Durch sie hindurch spiegelt sich im Ineinander von Begriff und Bild eine Vieldeutigkeit, welche den verwirrt, der nur die Eingleisigkeit einer universalistisch verankerten Welt kennt. In Jüngers Werk … ist die Welt nominalistisch wieder zum Wunder geworden.“ Wer das Denken Mohlers etwas genauer kennt, weiß, welche Bedeutung das Stichwort „Nominalismus“ für ihn hatte, wie er sich bis zum Schluß auf immer neuen Wegen eine eigenartige, den Phänomenen zugewandte Weltsicht, zu erschließen suchte. Er hatte dafür als „Augenmensch“ bei dem „Augenmenschen“ Jünger eine Anregung gefunden, wie sonst nur in der Kunst.

Es wäre deshalb ein Mißverständnis, anzunehmen, daß Mohler Jünger auf Grund der besonderen Bedeutung, die er den Arbeiten zwischen den Kriegsbüchern und der zweiten Fassung des Abenteuerlichen Herzens beimaß, keine Weiterentwicklung zugestanden hätte. Ihm war durchaus bewußt, daß Gärten und Straßen das Alterswerk einleitete und zu einer deutlichen – und aus seiner Sicht legitimen – Veränderung des Stils geführt hatte. Es ging ihm auch nicht darum, Jünger auf die Weltanschauung der zwanziger Jahre festzulegen, wenngleich das Politische für seine Zuwendung eine entscheidende Rolle gespielt und zum Bruch mit der Linken geführte hatte. Sein Freund Werner Schmalenbach schilderte die Verblüffung des Basler Milieus aus Intellektuellen und Emigranten, in dem sich Mohler bis dahin bewegte, als dessen Begeisterung für Deutschland und für Jünger klarer erkennbar wurde. Nach seiner Rückkehr in die Schweiz und dem Bekanntwerden seines Abenteuers wurde er in diesen Kreisen selbstverständlich als „Nazi“ gemieden. Beirrt hat Mohler das aber nicht, weder in seinem Interesse an der Konservativen Revolution, noch in seiner Verehrung für Jünger.

Die persönliche Begegnung zwischen beiden wurde dadurch angebahnt, daß Mohler 1946 in der Zeitung Weltwoche einen Aufsatz über Jünger veröffentlichte, der weit von den üblichen Verurteilungen entfernt war. Es folgte ein Briefwechsel und dann die Aufforderung Jüngers, Mohler solle nach Abschluß seiner Dissertation eine Stelle als Sekretär bei ihm antreten. Als Mohler dann nach Ravensburg kam, wo Jünger vorläufig Quartier genommen hatte, war die Atmosphäre noch ganz vom Nachkrieg geprägt. Man bewegte sich wie in der Waffenstillstandszeit von 1918/19 in einer Art Traumland – zwischen Zusammenbruch und Währungsreform –, und alle möglichen politischen Kombinationen schienen denkbar. Der Korrespondenz zwischen Mohler und seinem engsten Freund Hans Fleig kann man entnehmen, daß damals beide die Wiederbelebung der „Konservativen Revolution“ erwarteten: die „antikapitalistische Sehnsucht“ des deutschen Volkes, von der Gregor Strasser 1932 gesprochen hatte, war in der neuen Not ungestillt, ein „heroischer Realismus“ konnte angesichts der verzweifelten Lage als Forderung des Tages erscheinen, auch die intellektuelle Linke glaubte, daß die „Frontgeneration“ ein besonderes Recht auf Mitsprache besitze, und das Ausreizen der geopolitischen Situation mochte als Chance gelten, die Teilung Deutschlands zwischen den Blöcken zu verhindern. Wie man Mohlers Ravensburger Tagebuch, aber auch anderen Dokumenten entnehmen kann, waren Jünger solche Gedanken nicht fremd, wenngleich die Erwägungen – bis hin zu nationalbolschewistischen Projekten – eher spielerischen Charakter hatten.

Differenzen zwischen beiden ergaben sich auf literarischem Feld. Mohler hatte Schwierigkeiten mit den letzten Veröffentlichungen Jüngers. Ihn irritierten die Friedensschrift (1945) und der große Essay Über die Linie (1951), und den Roman Heliopolis (1949) hielt er für mißlungen. Die Sorge, daß Jünger sich untreu werden könnte, schwand erst nach dem Erscheinen von Der Waldgang (1951). Mohler begrüßte das Buch enthusiastisch und als Bestätigung seiner Auffassung, daß man angesichts der Lage den Einzelgänger stärken müsse. Was sonst zu sagen sei, sollte getarnt werden, wegen der „ausgesprochenen Bürgerkriegssituation“, in der man schreibe. Er erwartete zwar, daß der „Antifa-Komplex“ bald erledigt sei, aber noch wirkte die Gefährdung erheblich und der „Waldgänger“ war eine geeignetere Leitfigur als „Soldat“ oder „Arbeiter“.

Mohler betrachtete den Waldgang vor allem als erste politische Stellungnahme Jüngers nach dem Zusammenbruch, eine notwendige Stellungnahme auch deshalb, weil die Strahlungen und die darin enthaltene Auseinandersetzung mit den Verbrechen der NS-Zeit viele Leser Jüngers befremdet hatte. In der aufgeheizten Atmosphäre der Schulddebatten fürchteten sie, Jünger habe die Seiten gewechselt und wolle sich den Siegern andienen; Mohler vermerkte, daß in Wilflingen kartonweise Briefe standen, deren Absender Unverständnis und Ablehnung zum Ausdruck brachten.

Mohler betrachtete den Waldgang vor allem als erste politische Stellungnahme Jüngers nach dem Zusammenbruch, eine notwendige Stellungnahme auch deshalb, weil die Strahlungen und die darin enthaltene Auseinandersetzung mit den Verbrechen der NS-Zeit viele Leser Jüngers befremdet hatte. In der aufgeheizten Atmosphäre der Schulddebatten fürchteten sie, Jünger habe die Seiten gewechselt und wolle sich den Siegern andienen; Mohler vermerkte, daß in Wilflingen kartonweise Briefe standen, deren Absender Unverständnis und Ablehnung zum Ausdruck brachten.

Mohler schloß sich dieser Kritik ausdrücklich nicht an und hielt ihr entgegen, daß sie am Kern der Sache vorbeigehe. „Der deutsche ‚Nationalismus‘ oder das ‚nationale Lager‘ oder die ‚Rechte‘ … wirkt heute oft erschreckend verstaubt und antiquiert – und dies gerade in einem Augenblick, wo [ein] bestes nationales Lager nötiger denn je wäre. Die Verstaubtheit scheint mir daher zu kommen, daß man glaubt, man könne einfach wieder da anknüpfen, wo 1933 oder 1945 der Faden abgerissen war.“ Einige arbeiteten an einer neuen „Dolchstoß-Legende“, andere suchten die Schlachten des Krieges noch einmal zu führen und nun zu gewinnen, wieder andere setzten auf einen „positiven Nationalsozialismus“ oder auf eine Wiederbelebung sonstiger Formen, die längst überholt und abgestorben waren. In der Überzeugung, daß eine Restauration nicht möglich und auch nicht wünschenswert sei, trafen sich Mohler und Jünger.

Die Stellung Mohlers als „Zerberus“ des „Chefs“ war nie auf Dauer gedacht. Mohler plante eine akademische Karriere und betrachtete seine Tätigkeit als Zeitungskorrespondent, die er 1953 aufnahm, auch nur als Vorbereitung. Der Kontakt zu Jünger riß trotz der Entfernung nie ab. interessanterweise bemühten sich in dieser Phase beide um eine Neufassung des Begriffs „konservativ“, die ausdrücklich dem Ziel dienen sollte, einen weltanschaulichen Bezugspunkt zu schaffen.

Wie optimistisch Jünger diesbezüglich war, ist einer Bemerkung in einem Brief an Carl Schmitt zu entnehmen, dem er am 8. Januar 1954 schrieb, er beobachte „an der gesamten Elite“ eine „entschiedene Wendung zu konservativen Gedanken“, und im Vorwort zu seinem Rivarol – ein Text, der in der neueren Jünger-Literatur regelmäßig übergangen wird – geht es an zentraler Stelle um die „Schwierigkeit, ein neues, glaubwürdiges Wort für ‚konservativ‘ zu finden“. Jünger hatte ursprünglich vor, gegen ältere Versuche eines Ersatzes zu polemisieren, verzichtete aber darauf, weil er dann auch den Terminus „Konservative Revolution“ hätte einbeziehen müssen, was er aus Rücksicht auf Mohler nicht tat. Daß ihn seine intensive Beschäftigung mit den Maximen des französischen Gegenrevolutionärs „stark in die politische Materie“ führte, war Jünger klar. Wenn dagegen so wenig Vorbehalte zu erkennen sind, dann hing das auch mit dem Erfolg und der wachsenden Anerkennung zusammen, die er in der ersten Hälfte der fünfziger Jahre erfuhr. Zeitgenössische Beobachter glaubten, daß er zum wichtigsten Autor der deutschen Nachkriegszeit werde.

Dieser „Boom“ erreichte einen Höhepunkt mit Jüngers sechzigstem Geburtstag. Es gab zwar auch heftige Kritik am „Militaristen“ und „Antidemokraten“, aber die positiven Stimmen überwogen. Mohler hatte für diesen Anlaß nicht nur eine Festschrift vorbereitet, sondern auch eine Anthologie zusammengestellt, die unter dem Titel Die Schleife erschien. Der notwendige Aufwand an Zeit und Energie war sehr groß gewesen, die prominentesten Beiträger für die Festschrift, Martin Heidegger, Gottfried Benn, Carl Schmitt, bei Laune zu halten, ein schwieriges Unterfangen – Heidegger zog seinen Beitrag aus nichtigen Gründen zweimal zurück. Ganz zufrieden war der Jubilar aber nicht; Jünger mißfiel die geringe Zahl ausländischer Autoren, und bei der Schleife hatte er den Verdacht, daß hier suggeriert werde, es handele sich um ein Buch aus seiner Feder. Die Ursache dieser Verstimmung war eine kleine Manipulation des schweizerischen Arche-Verlags, in dem Die Schleife erschienen war, und der auf den Umschlag eine Titelei gesetzt hatte, die einen solchen Irrtum möglich machte.

Im Hintergrund spielte außerdem der Wettbewerb verschiedener Häuser um das Werk Jüngers mit, dessen Bücher in der Nachkriegszeit zuerst im Furche-, den man ihm zu Ehren in Heliopolis-Verlag umbenannt hatte, dann bei Neske und bei Klostermann erschienen waren. Außerdem versuchte ihn Ernst Klett für sich zu gewinnen. Wenn Klostermann die Festschrift herausbrachte, obwohl er davon kaum finanziellen Gewinn erwarten durfte, hatte das mit der Absicht zu tun, die Bindung Jüngers zu festigen. Deshalb korrespondierte der Verleger mit Mohler nicht nur wegen der Ehrengabe, sondern gleichzeitig auch wegen einer Edition des Gesamtwerks, die Jünger dringend wünschte.

Klostermann und Mohler waren einig, daß eine solche Sammlung nach „Wachstumsringen“ geordnet werden müsse, jedenfalls der Chronologie zu folgen und die ursprünglichen Fassungen zu bringen beziehungsweise Änderungen kenntlich zu machen habe. Bekanntermaßen ist dieser Plan nicht in die Tat umgesetzt worden. Rivarol war das letzte Buch, das Jünger bei Klostermann veröffentlichte, danach wechselte er zu Klett, dem er gleichzeitig die Verantwortung für die „Werke“ übertrug. In einem Brief vom 15. Dezember 1960 schrieb Klostermann voller Bitterkeit an Mohler, daß er die Ausgabe im Grunde für unbenutzbar halte und mit Bedauern feststelle, daß Jünger gegen Kritik immer unduldsamer werde. Zwei Wochen später veröffentlichte Mohler einen Artikel über die Werkausgabe in der Züricher Tat. Jüngers „Übergang in das Lager der ‚Universalisten‘“ wurde nur konstatiert, aber die Eingriffe in die früheren Texte scharf getadelt.

Noch grundsätzlicher faßte Mohler seine Kritik für einen großen Aufsatz zusammen, der im Dezember 1961 in der konservativen Wochenzeitung Christ und Welt erschien und von vielen als Absage an Jünger gelesen wurde. Mohler verurteilte hier nicht nur die Änderung der Texte, er mutmaßte auch, sie folgten dem Prinzip der Anbiederung, man habe „ad usum democratorum frisiert“, es gebe außerdem ein immer deutlicher werdendes „Gefälle“ im Hinblick auf die Qualität der Diagnostik, was bei den letzten Veröffentlichungen Jüngers wie An der Zeitmauer (1959) und Der Weltstaat (1960) zu einer Beliebigkeit geführt habe, die wieder zusammenpasse mit anderen Konzessionen Jüngers, um „sich mit der bis dahin gemiedenen Öffentlichkeit auszugleichen“. Mohler deutete diese Tendenz nicht einfach als Schwäche oder Verrat, sondern als negativen Aspekt jener„osmotischen“ Verfassung, die Jünger früher so sensibel für kommende Veränderungen gemacht habe.

Jünger brach nach Erscheinen des Textes den Kontakt ab. Daß Mohler das beabsichtigte, ist unwahrscheinlich. Noch im Juni 1960 hatte Jünger ihn in Paris besucht, kurz bevor Mohler nach Deutschland zurückkehrte, und im Gästebuch stand der Eintrag: „Wenige sind wert, daß man ihnen widerspricht. Bei Armin Mohler mache ich eine Ausnahme. Ihm widerspreche ich gerne.“ Jetzt warf Jünger Mohler vor, ihn ideologisch mißzuverstehen und äußerte in einem Brief an Curt Hohoff: „Das Politische hat mich nur an den Säumen beschäftigt und mir nicht gerade die beste Klientel zugeführt. Würden Mohlers Bemühungen dazu beitragen, daß ich diese Gesellschaft gründlich loswürde, so wäre immerhin ein Gutes dabei. Aber solche Geister haben ein starkes Beharrungsvermögen; sie verwandeln sich von lästigen Anhängern in unverschämte Gläubiger.“

Sollte Jünger Mohlers Text tatsächlich nicht gelesen haben, wie er hier behauptete, wäre ihm auch der Schlußpassus entgangen, in dem Mohler zwar nicht zurücknahm, was er gesagt hatte, aber festhielt, daß ein einziges der großen Bücher Jüngers genügt hätte, um diesen „für immer in den Himmel der Schriftsteller“ eingehen zu lassen: „An dessen Scheiben wir Kritiker uns die Nase plattdrücken.“ Die Ursache für Mohlers Schärfe war Enttäuschung, eine Enttäuschung trotz bleibender Bewunderung. Mohler warf Jünger mit gutem Grund vor, daß dieser in der zweiten Hälfte der fünfziger Jahre ohne Erklärung den Kurs geändert hatte und sich in einer Weise stilisierte, die ihn nicht mehr als „großen Beunruhiger“ erkennen ließ. Man konnte das wahlweise auf Jüngers „Platonismus“ oder sein Bemühen um Klassizität zurückführen. Tendenzen, mit denen Mohler schon aus Temperamentsgründen wenig anzufangen wußte.

Die Wiederannäherung kam deshalb erst nach langer Zeit und angesichts der Wahrnehmung zustande, daß Jünger eine weitere Kehre vollzog. Das Interview, das der Schriftsteller am 22. Februar 1973 Le Monde gab, wirkte auf Mohler elektrisierend, was vor allem mit jenen Schlüsselzitaten zusammenhing, die von der deutschen Presse regelmäßig unterschlagen wurden: Zwar hatte man mit einer gewissen Irritation Jüngers Äußerung gemeldet, er könne weder Wilhelm II. noch Hitler verzeihen, „ein so wundervolles Instrument wie unsere Armee vergeudet zu haben“, aber niemand wagte sein Diktum hinzuzufügen: „Wie hat der deutsche Soldat zweimal hintereinander unter einer unfähigen politischen Führung gegen die ganze wider ihn verbündete Welt sich halten können? Das ist die einzige Frage, die man meiner Ansicht nach in 100 Jahren stellen wird.“ Und nirgends zu finden war die Prophetie über das Schicksal, das den Deutschen im Geistigen bevorstand: „Alles, was sie heute von sich weisen, wird eines schönen Tages zur Hintertüre wieder hereinkommen.“

Mohler stellte die Rückkehr zum Konkret-Politischen mit der Wirkung von Jüngers Roman Die Zwille zusammen, ein „erzreaktionäres Buch“, so sein Urteil, das in seinen besten Passagen jene Fähigkeit zum „stereoskopischen“ Blick zeigte, die von Mohler bewunderte Fähigkeit, das Besondere und das Typische – nicht das Allgemeine! – gleichzeitig zu erkennen. Obwohl Mohler an seiner Auffassung vom „Bruch“ im Werk festhielt, hat der Aufsatz Ernst Jüngers Wiederkehr wesentlich dazu beigetragen, den alten Streit zu beenden. Die Verbindung gewann allmählich ihre alte Herzlichkeit zurück, und seinen Beitrag in der Festschrift zu Mohlers 75. Geburtstag versah Jünger mit der Zeile „Für Armin Mohler in alter Freundschaft“; beide telefonierten häufig und ausführlich miteinander, und wenige Monate vor dem Tod Jüngers, im Herbst 1997, kam es zu einer letzten persönlichen Begegnung in Wilflingen.

Nachdem Jünger gestorben war, gab ihm Mohler, obwohl selbst betagt und krank, das letzte Geleit. Er empfand das mit besonderer Genugtuung, weil es ihm nicht möglich gewesen war, Carl Schmitt diese letzte Ehre zu erweisen. Jünger und Schmitt hatten nach Mohlers Meinung den größten Einfluß auf sein Denken, mit beiden war er enge Verbindungen eingegangen, die von Schwankungen, Mißverständnissen und intellektuellen Eitelkeiten nicht frei waren, zuletzt aber Bestand hatten. Den Unterschied zwischen ihnen hat Mohler auf die Begriffe „Idol“ und „Lehrer“ gebracht: Schmitt war der „Lehrer“, Jünger das „Idol“. Wenn man „Idol“ zum Nennwert nimmt, dann war Mohlers Verehrung eine besondere – von manchen Heiden sagt man, daß sie ihre Götter züchtigen, wenn sie nicht tun, was erwartet wird.

Article printed from Sezession im Netz: http://www.sezession.de

URL to article: http://www.sezession.de/2066/juenger-und-mohler.html

URLs in this post:

[1] pdf der Druckfassung: http://www.sezession.de/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/weissmann_junger-und-mohler.pdf

[2] Image: http://www.sezession.de/heftseiten/heft-22-februar-2008

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Nouvelle Droite, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature allemande, armin mohler, ernst jünger, nouvelle droite, philosophie, révolution conservatrice, droite, droite allemande |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://aucoeurdunationalisme.blogspot.com

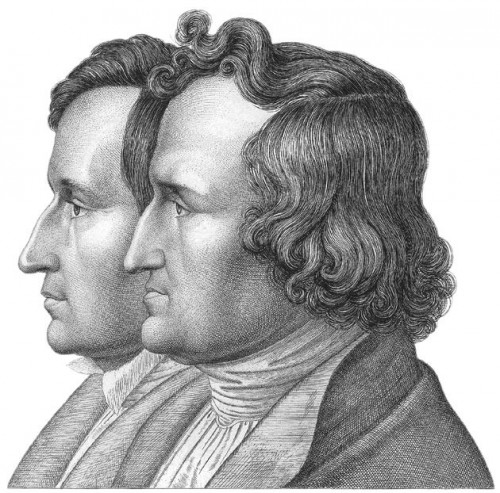

À l'heure de l’éveil des nationalités, l'entreprise des frères Grimm vise donc à faire prendre conscience aux Allemands de la richesse du patrimoine culturel qui leur est commun et à leur montrer que ce patrimoine, qui représente "l’âme germanique" dans son essence, en même temps que la "conscience nationale courbée sous l'occupation", peut servir aussi de base à leur unité politique.

À l'heure de l’éveil des nationalités, l'entreprise des frères Grimm vise donc à faire prendre conscience aux Allemands de la richesse du patrimoine culturel qui leur est commun et à leur montrer que ce patrimoine, qui représente "l’âme germanique" dans son essence, en même temps que la "conscience nationale courbée sous l'occupation", peut servir aussi de base à leur unité politique.

C’est dans la même intention qu'Achim von Arnim et C. Brentano collectent les vieilles poésies populaires. En septembre 1806, Arnim écrit à Brentano : "Celui qui oublie la détresse de la patrie sera oublié de Dieu en sa détresse". Quelques jours plus tard, à la veille de la bataille d'Iéna, il distribue aux soldats de Blücher des chants guerriers de sa composition. Parallèlement, il jette les bases de la théorie de l'État populaire (Volksstaat). Systématiquement, le groupe de Heidelberg s'emploie ainsi à mettre au jour les relations qui existent entre la culture populaire et les traditions historiques. Influencé par Schelling, Carl von Savigny oppose sa conception historique du droit aux tenants du jusnaturalisme [droit naturel]. Il affirme qu'aucune institution ne peut être imposée du dehors à une nation et que le droit civil est avant tout le produit d’une tradition spécifique mise en forme par la conscience populaire au cours de l'histoire. Le droit, dit-il, est comme la langue : "Il grandit avec le peuple, se développe et meurt avec lui lorsque celui-ci vient à perdre ses particularités profondes" (De la vocation de notre temps pour la législation et la science du droit).

Avec les romantiques, J. Grimm proteste lui aussi contre le rationalisme des Lumières. Il exalte le peuple contre la culture des "élites". Il célèbre l'excellence des institutions du passé. Revenu à Kassel, où Jérôme Bonaparte, roi de Westphalie, s’installe en 1807 au Château de Wilhelmshöhe (construit au pied d'une colline dominant la ville par le prince-électeur Guillaume Ier), il occupe avec son frère diverses fonctions dans l'administration et à la bibliothèque. À partir de 1808, ils collaborent tous 2 à la Zeitung für Einsiedler, où l'on retrouve les signatures de Brentano, Arnim, Josef Görres, etc. En 1813, ils lanceront leur propre publication, les Altdeutsche Wälder.