dimanche, 19 janvier 2014

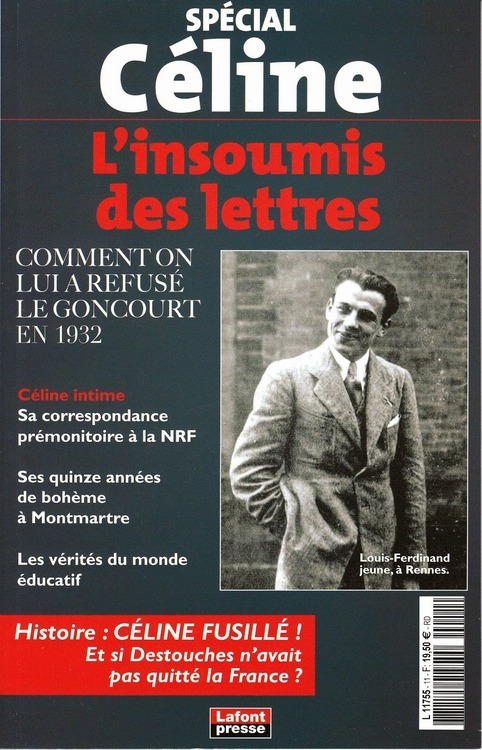

Proust et Céline

Proust et Céline

par Marc Laudelout

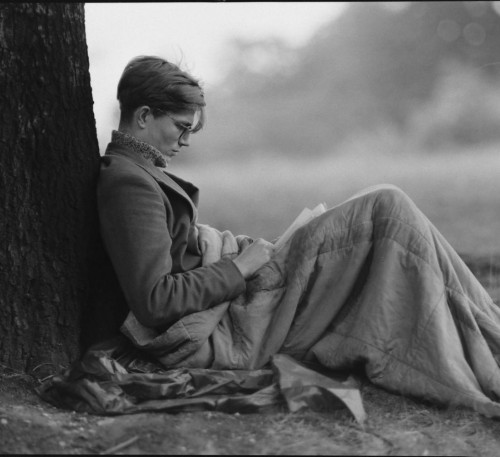

Opposer Proust à Céline aura été une constante de la critique depuis près d’un siècle. Dès 1932, Léon Daudet écrivait ceci : « Proust, avec toute sa puissance, que j’ai célébrée un des premiers, c’est aussi un recueil de toutes les observations et médisances salonnières dans une société en décomposition. Il est le Balzac du papotage. De là une certaine fatigue dont M. Céline va libérer sa génération ¹. » Céline lui-même s’est voulu en quelque sorte l’antithèse de celui qu’il considéra parfois comme un rival. Mais les auteurs d’un récent Dictionnaire amoureux de Proust ² ont tort de croire qu’il n’a jamais varié dans ses appréciations. Il fut un temps où Céline se devait de s’opposer à lui pour édifier une œuvre aussi émotive que celle de son illustre aîné mais assurément moins bavarde, ou à tout le moins ne se perdant pas dans les dédales d’une infinie introspection. À la fin de sa vie, Céline admettra que « Proust est le dernier, le grand écrivain de notre génération ³ », ce qui n’est tout de même pas rien. L’un des co-auteurs de ce dictionnaire note que les ressemblances entre les deux œuvres sont plus grandes qu’on ne le croit généralement. Et d’affirmer, par exemple, que la compassion de Bardamu à l’égard du sergent Alcide s’applique exactement à celle éprouvée par le baron de Charlus envers les soldats de la Grande Guerre. Et que le fameux aphorisme célinien, « La grande défaite, en tout, c’est d’oublier », est une phrase que Proust aurait pu signer, voulant dire par là que tous deux détestent l’oubli – ce qui n’est pas faux mais n’a rien d’original.

Voilà un rapprochement qui aurait le don d’exaspérer l’inénarrable Charles Dantzig, proustolâtre éperdu et anticélinien primaire. Anxieux, il imagine, dans un avenir proche, l’équivalent (anti)proustien du Contre Céline qui nous fut infligé il y a une quinzaine d’années : « J’ai été frappé au moment d’une querelle littéraire contre le réalisme, que j’ai eue il y a quelques mois, de voir qu’on s’en servait pour défendre Céline au détriment de Proust. Dans les temps haineux qui se sont réveillés, je ne serais pas surpris si, dans cinq ans, paraissait un pamphlet contre Proust, la mollesse et la décadence. Et on regrettera alors ce qui, rétrospectivement, sera devenue une époque. L’époque “Proust friendly” 4». Allusion, on l’aura compris, à l’expression « gay friendly » chère à l’auteur ; « les temps haineux » évoquant les manifestations contre « le mariage pour tous ». Cela étant, c’est méconnaître l’œuvre célinienne que de la réduire au « réalisme » ; hier au « populisme ». Déjà dans un de ses bouquins, ne faisait-il pas sien le commentaire navrant d’un Malraux vieillissant qui comparait la verve de Céline à celle d’un chauffeur de taxi ? Ailleurs il qualifie Céline et Beethoven de « génies des adolescents incultes 5» [sic]. Lorsque la bêtise culmine à ce point, on demeure sans voix.

Marc LAUDELOUT

1. Léon Daudet, « L.-F. Céline : “Voyage au bout de la nuit” », Candide, 22 décembre 1932.

2. Jean-Paul et Raphaël Enthoven, Dictionnaire amoureux de Proust, Plon / Grasset, 2013. Voir les propos du second [sur Proust et Céline] recueillis par Philippe Delaroche, « L’autre questionnaire de Proust », Lire, n° 419, octobre 2013, p. 8. Sur les deux auteurs, voir le portrait qu’en dresse Emmanuel Ratier dans Faits & Documents, n° 368, 15 décembre-15 janvier 2013 (B.P. 254-09, 75424 Paris Cedex 09).

3. Jean Guenot (éd.), Céline à Meudon (Transcription des entretiens avec Jacques d’Arribehaude et Jean Guenot), Éd. Guenot, 1995.

4. Charles Dantzig, Émission « Secret professionnel » (Du côté de chez Swann), France Culture, 6 octobre 2013. Cette émission peut actuellement être écoutée sur le site internet de France Culture.

5. Idem, Encyclopédie capricieuse du tout et du rien, Grasset, 2009.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, marc laudelout, littérature, marcel proust, céline |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 17 janvier 2014

Fiodor Tioutchev

Fiodor Tioutchev

Recension: Fjodor Tjutschew, Russland und der Westen. Politische Aufsätze, Verlag Ernst Kuhn (PF 47, 0-1080 Berlin), Berlin, 1992, 112 S., DM 29,80, ISBN 3-928864-02-5.

Recension: Fjodor Tjutschew, Russland und der Westen. Politische Aufsätze, Verlag Ernst Kuhn (PF 47, 0-1080 Berlin), Berlin, 1992, 112 S., DM 29,80, ISBN 3-928864-02-5.

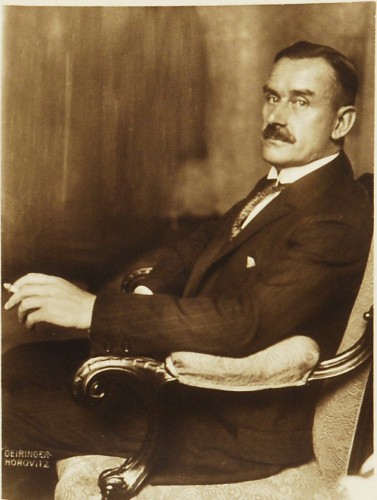

Totalement oublié, bien qu’il fut l’inspirateur de Dostoïevski et de Tolstoï, qui ne tarissaient pas d’éloges à son égard, Fiodor Ivanovitch Tioutchev (1804-1873) a été, sa vie durant, une personnalité écartelée entre tradition et modernité, entre l’athéisme et la volonté de trouver ancrage et refuge en Dieu, entre l’Europe et la Russie. L’éditeur berlinois Ernst Kuhn propose une traduction allemande des trois principaux textes politiques de Tioutchev, rédigés au départ en français (la langue qu’il maîtrisait le mieux); ces trois textes sont: “La Russie et l’Allemagne” (1844), une réponse au pamphlet malveillant qu’avait publié le Marquis de Custine sur l’Empire de Nicolas I, “La Russie et la révolution” (1849), une lettre adressée au Tsar rendant compte des événements de Paris en 1848, “La question romaine et la Papauté” (1849) qui est un rapport sur la situation en Italie.

Dans ces trois écrits, Tioutchev oppose radicalement la Russie à l’Europe occidentale. La Russie est intacte dans sa foi orthodoxe; l’Europe est pourrie par l’individualisme, issue de l’infaillibilité pontificale, de la Réforme et de la Révolution française, trois manifestations idéologiques qui ont épuisé les sources créatrices de l’Ouest du continent. La Russie est le dernier barrage qui s’opposera à cette “maladie française” (allusion à la syphilis). Cette vision prophétique de l’histoire, apocalyptique, le rapproche d’un Donoso Cortès: au bout du chemin, la Russie, incarnation du principe chrétien (orthodoxe) affrontera l’Occident, incarnation du principe antichrétien. Cette bataille sera décisive. Plusieurs idées-forces ont conduit Tioutchev à esquisser cet Armageddon slavophile. Pour lui, le besoin de lier toujours le passé au présent est “ce qui a de plus humain en l’homme”. On ne peut donc regarder l’histoire avec l’oeil froid de l’empiriste; il faut la rendre effervescente et vivante en y injectant ses émotions, en lui donnant sans cesse une dimension mystique. Celle-ci est un “principe de vie” (“natchalo”), encore actif en Russie, alors qu’en Europe occidentale, où Tioutchev a passé vingt-deux ans de sa vie, règne la “besnatchalié” (l’absence de principe de vie). C’est ce principe de vie qui est Dieu pour notre auteur. C’est ce principe qui est ancre et stabilité, pour un homme comme lui, qui n’a guère la fibre religieuse et ne parvient pas à croire vraiment. Mais la foi est nécessaire car sans Dieu, le pouvoir, le politique, n’est plus possible.

Mais cette mobilisation du conservatisme, qu’il a prônée pendant le règne de Nicolas I, a échoué devant la coalition anglo-franco-turque lors de la Guerre de Crimée. Ces puissances voulaient empêcher la Russie de parfaire l’unité de tous les Slaves, notamment ceux des Balkans. L’avènement d’Alexandre II le déçoit: “Que peut le matérialisme banal du gouvernement contre le matérialisme révolutionnaire?”, interroge-t-il, inquiet des progrès du libéralisme en Russie.

Tioutchev n’a pas seulement émis des réflexions d’ordre métaphysique. Pendant toute sa carrière, il a tenté d’élaborer une politique russe à l’intérieur du concert européen, s’éloignant, dans cette optique, de l‘isolationnisme des slavophiles. Ceux-ci exaltaient le paysannat russe et critiquaient la politique de Pierre le Grand. Tioutchev, lui, exaltait cette figure car elle avait établi la Russie comme grande puissance dans le Concert européen. Il optait pour une alliance avec la Prusse, contre la France et l’Autriche. Il voulait mater le nationalisme polonais et favoriser l’unité italienne. En ce sens, il était “moderne”, à cheval entre deux tendances.

Un auteur à méditer, à l’heure où la Russie, une nouvelle fois, est écartelée entre deux volontés: repli sur elle-même ou occidentalisation.

Robert Steuckers.

(recension parue dans “Vouloir”, n°105/108, juillet-septembre 1993).

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Livre, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : révolution conservatrice, révolution conservatrice russe, russie, 19ème siècle, russie impériale, littérature, lettres, lettres russes, littérature russes, fiodor tioutchev |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 15 janvier 2014

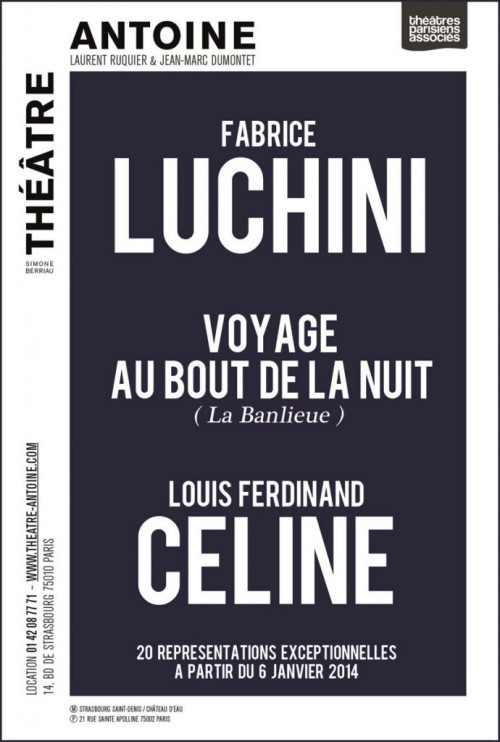

F. Luchini: Voyage au bout de la nuit

15:40 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : fabrice luchini, éline, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature, littérature française, théâtre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 10 janvier 2014

Entrevista a José Luís Ontiveros, escritor mexicano

Por Juan Carlos Vergara y Gonzalo Geraldo Peláez

Bestia inclasificable, escritor heterodoxo y sumamente molesto, a contracorriente de las bagatelas y mercachifles a la orden del dólar en nuestra literatura más reciente. Lobo estepario, vive solitario en una isla de Aztlán donde espera pacientemente los signos de lo Alto que le anuncien su último viaje, el viaje a la Ciudad de Los Césares. Mítica ciudad donde se encontrará con los más fieles: el maestro del estilo, Ernesto Giménez Caballero; el profeta de la Tercera Roma, Fédor Dostoievski; el escritor anarco-fascista mexicano Rubén Sálazar Mallén; el emboscado Ernst Jünger; el abominable Louis-Ferdinad Céline; el mártir y trovador Ezra Pound y el último guerrero de Oriente, Yukio Mishima.

Bestia inclasificable, escritor heterodoxo y sumamente molesto, a contracorriente de las bagatelas y mercachifles a la orden del dólar en nuestra literatura más reciente. Lobo estepario, vive solitario en una isla de Aztlán donde espera pacientemente los signos de lo Alto que le anuncien su último viaje, el viaje a la Ciudad de Los Césares. Mítica ciudad donde se encontrará con los más fieles: el maestro del estilo, Ernesto Giménez Caballero; el profeta de la Tercera Roma, Fédor Dostoievski; el escritor anarco-fascista mexicano Rubén Sálazar Mallén; el emboscado Ernst Jünger; el abominable Louis-Ferdinad Céline; el mártir y trovador Ezra Pound y el último guerrero de Oriente, Yukio Mishima.

1. ¿Cuál es el papel de México en el contexto del desarrollo de un “nacionalismo continental” y quiénes son sus representantes?

Creo que la idea de una Federación de Naciones Hispánicas está contenida en el origen mismo del ser imperial de México con el emperador Iturbide. Don Agustín de Iturbide –que es el realizador y no sólo el consumador de la Independencia, como a su vez el creador de la Bandera Nacional Trigarante, la de las tres garantías: “religión, unión e independencia”– se pone de acuerdo con el Libertador Simón Bolívar para convocar, en lo que hoy es el territorio de Panamá segregado por los gringos de Colombia, a las naciones iberoamericanas para crear una Federación de Pueblos Hispánicos en una Junta Anfictiónica. Puede decirse entonces que desde su nacimiento a la independencia política bajo la forma imperial, México está marcado por un principio geopolítico y meta-político a la vez, en que lo importante es la vertebración de los pueblos iberoamericanos en una Gran Nación para poder enfrentar tanto a los anglosajones como a las potencias europeas.

Durante el siglo XIX, México sufrirá la guerra de agresión estadounidense, que ya estaba en el destino manifiesto de aquel país y que no es más que la transposición secular del mesianismo del pueblo elegido: la “judeocracia” como raíz de los Estados Unidos –por eso decía von Salomon, aquel nacional-bolchevique tan extraordinario y de una altura escritural semejante a la de Jünger, en su libro El Cuestionario, que le parecía obsceno que la gente tuviera que jurar bajo la Biblia, como si ella no contuviera muchos pasajes genocidas y otros de aberraciones morales-. Pero volviendo al tema de México, en el siglo XIX, cuando los yanquis cumplen con esa parte de su destino manifiesto que es la conquista de la Tierra Prometida y se apoderan de más de la mitad del territorio nacional, de la parte más rica de México, ello provoca que los conservadores, con sus limitaciones reaccionarias y güelfas, decidan en un momento determinado buscar en un país europeo un contrapeso a la expansión yanqui; es el caso de Francia, con Napoleón III que aprovechará la Guerra de Secesión en EE.UU. para intentar crear un Imperio Latino (de allí el término Latinoamérica acuñado por los franceses). Cuál es la idea entonces, ver en la figura de un príncipe europeo el restablecimiento del Imperio Mexicano, y eso se hace con el emperador Maximiliano de Habsburgo, quien tiene un fin trágico porque nunca los franceses quisieron en realidad un ejército imperial mexicano, independiente y poderoso. Los generales conservadores con mayor perspectiva, como era Miramón, que defendió el alcázar del castillo de Chapultepec con los cadetes del Colegio Militar en el último bastión de resistencia a la invasión gringa, y que es mandado al exterior, lo mismo que el general Mejías, son parte de aquel fin trágico consumado en manos del traidor Benito Juárez, quien firma el tratado McLane-Ocampo: un oprobio, algo indefendible, que los mismos liberales condenan en su obra magna México a través de los siglos. Es la venta de Baja California, el otorgamiento libre a las campañas punitivas yanquis en el norte y el paso a perpetuidad por el istmo de Tehuantepec. Prácticamente una entrega completa de México a los EE. UU. encabezada por el traidor Benito Juárez, quien con el apoyo yanqui arrastra a la derrota del ejército imperial y fusila al emperador Maximiliano, al general Miramón y al general Mejías en el Cerro de las Campanas.

De ahí se pasa a otra etapa del país, pero siempre está latente en el mexicano el propósito de una revancha contra los gringos, lo que ocurrirá en la Primera Guerra Mundial cuando la Alemania del Káiser manda un telegrama a Venustiano Carranza, primer jefe del Ejército Constitucionalista, y quien honra la memoria de Iturbide, primer jefe de las tropas insurgentes. Este telegrama es el telegrama Zimmermann, donde Alemania ofrece a México que si se une a la guerra en un nuevo frente contra los EE. UU. le serán devueltos en recompensa los territorios perdidos en 1847. México está desangrado por la revolución, no tiene capacidad operativa, pero de cualquier forma esto marca también otro hito muy claro de su trayectoria política más pura.

Pero ya llegando al terreno de las ideas, será, en principio, José Vasconcelos quien perfila la noción metafísica del águila y el cóndor en los motivos de la Universidad Nacional, de la que será rector y cuyo lema es “Por mi raza hablará el Espíritu”. Precisamente el lugar del águila bicéfala del imperio español, el cóndor y el águila, por una parte, y los motivos del escudo, por otra, como símbolos de la Unidad Continental de los Pueblos de América. Esto se encuentra también en la invitación que Vasconcelos hace a Gabriela Mistral a México, en donde desarrolla una gran labor que provoca la envidia de los pigmeos, fomentada por los mediocres que nunca faltan en ningún país nuestro y que son una mayoría. Entonces, Mistral regresa a Chile, pero la “idea iberoamericana” que forma parte de la Revolución Mexicana alienta al APRA peruano (Víctor Haya de la Torre) como al joven Sandino y, luego, al Peronismo.

A propósito del Peronismo, la Revolución Mexicana tiene una confluencia natural con éste. Hay una visita de una comisión mexicana en la etapa peronista recibida por Eva Duarte de Perón en la que figuran dos diputados que serán futuros presidentes mexicanos, Adolfo López Mateos y Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. Se puede decir que la misión vinculatoria de México en Latinoamérica, en la América Románica, en Iberoamérica, en Indo-América o como se le quiera designar, se mantiene hasta que se firma el Tratado de Libre Comercio en la época de la entropía de la Revolución Mexicana bajo el dominio tecnocrático de Carlos Salinas de Gortari. Se establece entonces el Tratado que da lugar al alejamiento de México de su “misión iberoamericana”.

Finalmente, hay que considerar que la Revolución Cubana es una forma en que México proyecta su Independencia. En México tuvo lugar el primer viaje que hacen los revolucionarios cubanos a bordo del Granma y que da inicio a la Revolución Cubana, donde juega un papel muy importante don Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios, de quien fui asesor y allegado y que fungía como agente especial de la Dirección Federal de Seguridad de los órganos de inteligencia mexicanos, bajo la dirección del presidente López Mateos. En esa ocasión dimos un golpe muy sensible a los gringos: cuando en la OEA todos los países latinoamericanos se inclinan ante el poder yanqui y piden que sea expulsada Cuba, el único país que defiende a Cuba es México.

Pero de toda esa trayectoria histórica y doctrinaria, se pasa a un estado de neocolonialismo cada vez más grave y abyecto.

2. ¿Cuáles serían las lecciones históricas de la Revolución Mexicana en cuanto origen de una tradición de pensamiento continental y revolucionario?

La Revolución Mexicana como todo nacionalismo tiene su raíz en la Revolución Francesa; por eso no debemos mitificar al nacionalismo en la medida que es una creación de la Ilustración. La fragmentación entre naciones también nos ha conducido a guerras fratricidas, especialmente en Sudamérica, como esa infame alianza entre Argentina, Brasil y Uruguay contra Paraguay, una verdadera abyección. También Chile, en ese sentido, tiene que revisar su papel respecto a Perú y Bolivia. Debemos estar conscientes por lo mismo que si no superamos el nacionalismo como cantonalidad de “pensamiento aldeano” y no pensamos en una “unidad superior política” como es el Imperio Iberoamericano, los latinoamericanos –donde quepan los brasileños pero no como poder suprematista sino en una relación de equidad– estaremos perdidos.

La Revolución Mexicana expresa el “ethos” más profundo de la nación mexicana, genera un movimiento literario, la “novela de la Revolución”, un movimiento pictórico como el muralismo, igualmente una importante corriente musical donde está el Huapango de Moncayo por ejemplo, con lo cual el mexicano vuelve a sentirse orgulloso de su ser mexicano. Esto es muy importante: tenemos que tener orgullo cada uno de nuestra particularidad pero sin que ello nos lleve a confrontarnos o a decir que nuestro particularismo es mejor que el otro.

En México, actualmente la Revolución Mexicana ha sido desmantelada por el partido que se dice heredero de la misma, el P.R.I. que también tiene etapas diversas desde su origen, con el gran geoestratega, el General Calles, creador del Partido Nacional Revolucionario, el partido de la Revolución Mexicana y fundamento del P.R.I., que ha retornado al poder tras el fracaso estruendoso de la derechona pro-yanqui y pro-sionista. Sin embargo, en estos momentos México atraviesa una crisis interna provocada por el desbordamiento de la violencia de los carteles del narcotráfico. Esto habría que revisarlo en otro punto: la cuestión de las drogas, su uso tradicional y mistérico como iniciación. También, como dijo el Che que había que llenar Latinoamérica de Vietnams, hay que llenar a los gringos de droga porque no pueden vivir sin ella, eso es evidente y es una verdad tan contundente como aromática es la marihuana.

3. ¿Qué examen realizas actualmente respecto al rechazo y el desprecio de la Cultura, y sus efectos de creciente despolitización?

Todo esto se explica en referencia a los ciclos cósmicos, por lo que no podemos para nada olvidar que estamos en el cierre de un ciclo, como dice Julius Evola, y como también explica don Miguel Serrano mencionando el Kaliyuga. Uno de los rasgos de la Edad Sombría, de la Edad de Hierro que mencionara Hesíodo, es el rechazo a toda vida comunitaria, a una axiología superior, a las raíces identitarias, a la personalidad histórica y a la definición del hombre por la palabra y el lenguaje. Es entonces una época de negacionismo, de nihilismo colectivo, en que los pueblos pierden su personalidad, es decir, su identidad y se vuelven consumidores, de ahí que estemos grupos como la revista chilena Ciudad de los Césares, el revisionismo histórico que representa Héctor Buela en Argentina desde la Video Editora El Walhalla. Distintas manifestaciones, algunas no organizadas en corrientes de opinión, pero sí en escritores simbólicos que las encarnan para volver a revitalizar el alma de los pueblos: “esa es la gran labor y el desafío cultural y político”. Y no hay que olvidar nunca la enseña poética de José Antonio Primo de Rivera: “A los pueblos no los han movido nunca más que los poetas”.

El hombre de la América Románica o de Indo-América, en particular, tiene el desafío de pensar un bloque geoestratégico Iberoamericano: “Iberoamérica como una unidad de destino en lo Universal”, como una exigencia de confrontación con la civilización gangrenada y occidentafílica, dominada por la “usurocracia judía”. Creo entonces que bajo la ecuación “amigo/enemigo” de Carl Schmitt tenemos muy claramente definidos a los enemigos: el lobby judío internacional, el Sanedrín, lo que llamaba ya San Pablo muy poéticamente “la sinagoga de Satanás”, y por otra parte sus siervos, los gringos, y sus aliados európidos otanescos. Ellos son el enemigo, que busca nuestro subyugamiento y la pérdida de nuestra lengua, nuestras creencias y nuestra manera de ser. Tenemos por tanto que afinar todos los medios estratégicos para vertebrar una resistencia iberoamericana que nos conduzca a una genuina “Segunda Guerra de Independencia”.

4. ¿Cuáles serían los modos de movilizar las fuerzas metafísicas o espirituales del bloque continental iberoamericano?

Ciertamente son los escritores y los poetas los que determinarán un nuevo ciclo para Iberoamérica. Como han citado a Jünger muy acertadamente, se trata de la <<movilización total>> de los “poderes metafísicos” del alma indestructible de nuestra estirpe: “mientras tengamos palabra y alma no podremos ser vencidos”. En sí considero, en ese sentido, que el fascismo como doctrina y revelación a los pueblos no fue vencido en la Segunda Guerra Mundial, y la prueba es que estamos aquí reunidos nosotros bajo un haz de flecha y bajo la bendición de la palabra y el Poder de lo Alto. Yo creo indudablemente que debemos buscar fórmulas políticas novedosas que no contengan en sí el uso de términos que muchas veces han sido satanizados, demonizados por la industria de Hollywood y el aparato de propaganda mundialista; de tal modo que estamos en desventaja táctica ante esos poderes que dominan el mundo, pero mientras mantengamos una relación y una comunión con el Poder de lo Alto y con los “magmas secretos que mueven la historia” podemos decir que un escritor en su buhardilla decide la historia del mundo.

5. ¿A quiénes consideras como los más caros representantes de la tradición político-cultural iberoamericana?

Cada uno de nuestros pueblos tiene una tradición literaria, tanto en historiografía como en teoría del Estado, suficiente como referencia para trazar un destino. Debemos, sin embargo, ver más allá de nosotros mismos, no para seguir de manera epigonal, servil, o como caricatura a pensadores de otras latitudes, sino para no perdernos en una visión de autosuficiencia y aislacionismo.

Así, yo diría que los puntos de referencia, más que en los pensadores políticos, está en los grandes escritores. Dostoievski es la referencia máxima que podemos encontrar respecto a la Santa Rusia, la Tercera Roma; Jünger es el que nos proporciona el medio más eficaz para actuar con inteligencia en las actuales condiciones de adversidad, en su obra La Emboscadura. Giménez Caballero (“Gecé”), en España, nos marca la necesidad de la imaginación y de la renovación del estilo como una forma de permanecer fieles y adelantarnos a los tiempos, porque creo que nuestra misión es “unir la Tradición con la Modernidad”. En términos posmodernos, es crear un sistema cultural autónomo pero flexible; no hablo necesariamente de sincretismo o eclecticismo, pero sí de cierta porosidad que permita animar a los nuevos bárbaros, y me refiero a mi libro Apología de la Barbarie, que se reeditará en España y Argentina en su edición definitiva, y cuyo sentido es ese retorno a los valores bárbaros, en los términos de Nietzsche, como generadores de nuevos significados. Necesitamos arrollar y terminar con la civilización senecta y gangrenada, insustentable, del neo-capitalismo usurocrático y reconstituir el “arte en la vida”, el arte de la guerra, el valor del guerrero, el valor del poeta. Creo que esto es lo fundamental. Cada uno de nuestros pueblos tiene en sus simientes la marca misma de la genialidad, de la originalidad y de un sentido propio, lo que no nos puede llevar a perder de vista la universalidad.

6. ¿Qué vínculos secretos o profundos se pueden establecer entre México, Japón y la Europa fascista?

Hay tradiciones fundamentales que, pese a que no han tenido, como en Japón, el cuidado de una descendencia dinástica –la de la Casa del Sol, el Imperio del Sol Naciente y el Emperador como hijo de la diosa Amaterasu–, mantienen un vínculo trascendente. Los símbolos imperiales de la tradición pre-hispánica son un ejemplo. Está como afinidad fundamental la doctrina azteca de “lucha y victoria” que se manifiesta en los caballeros águilas y tigres, y que estudian en el Calmécac no solamente el arte de la guerra sino el sentido sacro de su misión guerrera. Esto es similar a la imagen del samurái, que si bien con la dinastía Meiji y la modernización del Japón se ha visto humillado, despojándosele de la katana, alma del guerrero, en la Segunda Guerra la ha recuperado como símbolo del honor. Creo, a propósito del Japón, que no hubo ejército más decidido y fanático como “habitantes del templo” –su sentido etimológico– que ese, y que hay necesidad del fanatismo, no como obcecación y exclusión automática del otro, ni como satanización de enemigos cuya perversidad es intrínseca de una Iglesia Católica, sino como un aliento inclaudicable como el que tuvieron los japoneses en su combate, incluso superior, me atrevería a decir –con lo que les admiro–, a la Wehrmacht y las SS.

Pero digamos, para finalizar, lo siguiente: podemos constituir un “eje Aztlán-Austral-Yamato”, un nuevo eje Metafísico, un nuevo Poder Geopolítico Mundial. Mientras nuestros pueblos Iberoamericanos sigamos perdidos en nuestras insignificancias, en nuestros problemas locales, en las pequeñas cosas de la vida cotidiana, no podremos alzar al cielo nuestra palabra.

7. ¿Es el escritor e intelectual Octavio Paz el padre de la literatura mexicana moderna?

Es indudable que el príncipe Paz tuvo su corte, y que frente a las actuales pequeñas bestias y bestezuelas letradas, él fue de otra categoría, tanto por su estilo como por su obra ensayística y poética. El problema fundamental de Paz, sin embargo, es que no quería tener amigos ni seguidores sino lacayos, como todos los monarcas. México había sido regido antes de Paz por Alfonso Reyes, que se llevó muy bien con Borges; ha sido, en ese sentido, tierra pródiga en asilos y en la protección de los escritores iberoamericanos bajo persecución en épocas de gobiernos sin respeto a las letras ni a la diversidad espiritual. Entre todos los pueblos iberoamericanos, pocos pueden hablar de una historia de asilo y protección como la ha tenido México en muy diversas etapas de su historia, tanto a los españoles republicanos como al exilio chileno que produjo el Golpe militar.

Ahora bien, Paz es una referencia indudable en la vida literaria mexicana, y yo diría más, en la vida cultural e incluso política. Sin embargo, hay que ver también sus etapas. Está el joven Paz, que va a luchar junto a la Liga de Artistas y Escritores Revolucionarios (que era un engendro stalinista) en la Guerra Civil Española, donde naturalmente no disparó ni un solo tiro –quizá alguna flatulencia. Luego, el Paz que se vuelve “demócrata profesional” pero al mismo tiempo goza de todos los privilegios que da el P.R.I. en el poder, y que en 1968, hace el gesto, aunque más bien mueca, de renunciar a la embajada en India por la pretendida masacre de los estudiantes –que no pasarían de 500 y que fue una decisión patriótica y obligada de un gran presidente mexicano como fue don Gustavo Díaz Ordaz–. Renunciando puramente al título de embajador sigue cobrando la nómina. Es decir, Paz, como ejemplo de coraje, de la consistencia y del arrojo, no lo es. No es ningún tipo de Ezra Pound, ni nada semejante. Aunque sí tuvo la virtud de enfrentarse al mandarinato de la dictadura infrarroja en el pensamiento y logró de alguna forma abrir cauces a la expresión de otras tendencias políticas, pese a que actualmente su herencia sea usufructuada por el perverso judío Enrique Krauze, quien dirige la revista Letras Libres, que yo llamo “letras vencidas” o “letras en venta”. No hay ninguna similitud entre el gran escritor Paz y el amanuense Krauze, por lo que de alguna manera aquí no pasó como con Zeus y Kronos porque no hay que confiar nunca en un judío –aunque yo, como el Führer, admiro a un gran judío: León Bloy–.

8. ¿Qué nos puedes comentar de la experiencia de la “diáspora” o del “exilio” de los escritores o intelectuales vinculados a un pensamiento disidente, a una tercera vía de pensamiento?

Por principio no utilicemos el término diáspora, que eso es del pueblo judío errante; de lo que sí hablaría es del “exilio interior” y en esa perspectiva creo que sí es muy claro que somos como Robinsones. Lo de Robinsón Literario, dicho sea de paso, proviene de Ernesto Giménez Caballero (“Gecé”), que publicó el Robinsón Literario antes de la Guerra Civil Española como una proclama de que él vivía en su ínsula y que no quería entrar en una contienda fratricida; aunque al final, cuando se dieron las cosas, Giménez Caballero fue de alguna manera el Goebbels español, en las proporciones debidas.

Volviendo a lo nuestro, estamos los Robinsones, los que somos forajidos de la opinión, disidentes del espíritu, francotiradores, trotabosques, andariegos, vagabundos, transterrados: no tenemos el arraigo a una tierra que nos proteja porque le reprochamos a aquella donde hemos nacido su tendencia a la abyección, a la falta de creatividad, al aletargamiento del ser; somos profundamente antipáticos e incluso abominables, de alguna manera somos espectros de bestias negras, porque de un bestiario se trata, desde el Yeti, abominable hombre que vive en Aztlán, hasta Erwin Robertson y la gente que reafirma el ser más profundo de su pueblo, todos ellos abominables. Es lo que debemos considerar como la cuota obligada a cumplir, no tendremos reconocimiento nunca: nadie valorará nuestra obra, estamos solos, pero con nosotros está el Espíritu Santo.

9. ¿Cuáles serían los lazos profundos, esotéricos entre Iberoamérica y el mundo del Islam?

Un principio fundamental para reconocernos como Imperio Indo-americano, Iberoamericano o de la América Románica, es tener presente aquel factor fundamental en la constitución de nuestra “psique” como es el Islam. No solamente por su aportación a la actual lengua española, donde hablamos más de cuatro mil palabras de origen árabe –sin olvidar que el Profeta Muhammad, que bendito y protegido sea por Allah, surge de la tribu de los Qurays, que practicaba torneos de oratoria, perfeccionando y dando forma lingüística al árabe– no sólo por ello. También porque los ochos siglos que los árabes, el Islam, estuvo en España, son los siglos imborrables del gran califato de Córdoba, en donde se vivió la mayor riqueza espiritual de España, pese a la islamofobia actual provocada por el Sionismo.

Quien desarrolla la medicina, la arquitectura, la alquimia, es el Islam. En el Islam guardamos mucho del sentido patriarcal Iberoamericano: nuestra forma de considerar a la mujer es islámica, nuestra forma de combatir y hacer la guerra es islámica y proviene de la Yihâd, es decir de la “Guerra Santa”, nuestra forma de ser católicos es islámica… ¿qué no es islámico?...bueno, el vino, que es mediterráneo, griego. Pero todo lo demás está permeado del Islam, nuestra hospitalidad, nuestra forma de la cortesía, de la amabilidad, del tratamiento con las personas, del respeto, es Islámica y también nuestra concepción de la autoridad hierática es Islámica: somos tributarios de una profunda herencia islámica. Y yo diría que en estos momentos Siria, con su Islam profundo y tolerante, arraigado en el pueblo y no vuelto una herramienta de dominio, se convierte en el símbolo de los derechos de los pueblos. No hay ningún país más asediado, no hay ningún país más ultrajado, no hay ninguno que sufra más en carne propia esa agresión artera que proviene de todas las corrientes del Imperialismo Yanqui, del Sionismo y de los traidores al Islam bajo la careta de una falsa posición de purismo como es el Wahabbismo. Entonces, Siria es Chile, Siria es México, Siria es Argentina: “Siria es Iberoamérica”.

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : josé luis ontiveros, entretien, mexique, lettres, littérature, lettres mexicaines, littérature mexicaine, amérique latine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 07 janvier 2014

Une thèse sur Valentin Raspoutine

Une thèse sur Valentin Raspoutine

par Robert Steuckers

Recension: Günther HASENKAMP, Gedächtnis und Leben in der Prose Valentin Rasputins, Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, 1990, VII + 302 S., ISBN 3-447-03002-X.

Recension: Günther HASENKAMP, Gedächtnis und Leben in der Prose Valentin Rasputins, Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, 1990, VII + 302 S., ISBN 3-447-03002-X.

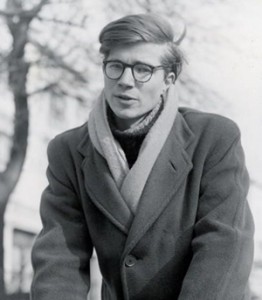

Valentin Grigorevitch Raspoutine, né le 15 mars 1937 en Sibérie, est le petit-fils d’un chasseur de la taïga et de Mariia Guerassimovna qui lui a raconté, pendant son enfance, les contes populaires de sa région. Ce qui lui a donné à jamais le sens de la continuité et de la durée, un goût indélébile pour tout ce qui est “archétype”. Son oeuvre de grand prosateur russe est placée entièrement sous le signe de la “perte de conscience” qui affecte nos contemporains, du passage d’une conscience mythique-intégrative à une attitude totalement démythifiée. Tel est le déficit —la plaie béante— de nos temps modernes. Cette crise doit être dénoncée et combattue. Après la période de stagnation brejnévienne (la “kosnost”), Raspoutine retrouve pleinement son rôle d’“écrivain-prédicateur”, qui va s’engager pour son peuple, afin qu’il retrouve une morale basée sur les acquis de son histoire et de sa tradition. Avec les autres “ruralistes” de la littérature russe contemporaine, il mènera la “guerre civile” des écrivains contre les “libéraux”, c’est-à-dire ceux qui veulent introduire en Russie les idées occidentales et la culture de masse calquée sur le modèle américain. Contre cette vision purement “sociétaire” qui ne reconnaît aucune présence ni récurrence potentielle aux moments forts du passé, qui ignore délibérément toute “saveur diachronique”, Raspoutine et les ruralistes défendent le statut mythique de la nation, révalorisent la pensée archétypique, réhabilitent l’unité substantielle avec les générations passées.

Le slaviste allemand Hasenkamp démontre que cet engagement nationaliste repose sur une “conscience mythique” traditionnelle où il n’y a pas de séparation entre le microcosme et le macrocosme, entre la chose et le signe, la réalité et le symbole. Dans Adieu à Matiora, son plus célèbre roman, l’île qui va être engloutie par le fleuve représente la totalité du monde, sa continuité, qui va être submergée par la pensée calculante, techniciste, administrative. Matiora est la continuité, face au “temps nouveau”, qui déracine les habitants et prépare l’inondation finale. Cette ère nouvelle sera une ère de discontinuité qui claudiquera d’interruption en interruption, de retour furtif à une vague stabilité en nouveau déracinement. Cette fragmentation conduit au malheur et à la dépravation morale. Les axes majeurs de la pensée philosophique de Raspoutine, qui ne s’exprime pas par de sèches théories mais dans des romans poignants, où l’on retrouve des linéaments d’apocalypse ou de Ragnarök, sont: la mméoire et la réalité transcendantale. Derrière la réalité empirique, derrière les misères quotidiennes et la banalité de tous les jours, se profile, pour qui sait l’apercevoir et l’honorer, une réalité supérieure, immortelle. Le monde moderne a voulu faire du passé table rase, a jugé que la mémoire n’était plus une valeur et la faculté de se souvenir n’était plus une vertu. Contre l’idéologie dominante, qui veut nous arracher nos histoires pour nous rendre dociles, l’oeuvre de Raspoutine, sa simplicité poignante et didactique, son universalité et sa russéité indissociables, sont des armes redoutables. A nous de nous en servir, à nous de diffuser son message. Qui est aussi le nôtre.

Le slaviste allemand Hasenkamp démontre que cet engagement nationaliste repose sur une “conscience mythique” traditionnelle où il n’y a pas de séparation entre le microcosme et le macrocosme, entre la chose et le signe, la réalité et le symbole. Dans Adieu à Matiora, son plus célèbre roman, l’île qui va être engloutie par le fleuve représente la totalité du monde, sa continuité, qui va être submergée par la pensée calculante, techniciste, administrative. Matiora est la continuité, face au “temps nouveau”, qui déracine les habitants et prépare l’inondation finale. Cette ère nouvelle sera une ère de discontinuité qui claudiquera d’interruption en interruption, de retour furtif à une vague stabilité en nouveau déracinement. Cette fragmentation conduit au malheur et à la dépravation morale. Les axes majeurs de la pensée philosophique de Raspoutine, qui ne s’exprime pas par de sèches théories mais dans des romans poignants, où l’on retrouve des linéaments d’apocalypse ou de Ragnarök, sont: la mméoire et la réalité transcendantale. Derrière la réalité empirique, derrière les misères quotidiennes et la banalité de tous les jours, se profile, pour qui sait l’apercevoir et l’honorer, une réalité supérieure, immortelle. Le monde moderne a voulu faire du passé table rase, a jugé que la mémoire n’était plus une valeur et la faculté de se souvenir n’était plus une vertu. Contre l’idéologie dominante, qui veut nous arracher nos histoires pour nous rendre dociles, l’oeuvre de Raspoutine, sa simplicité poignante et didactique, son universalité et sa russéité indissociables, sont des armes redoutables. A nous de nous en servir, à nous de diffuser son message. Qui est aussi le nôtre.

(recension parue dans “Vouloir”, n°105-108, juillet-septembre 1993, p. 23).

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : russie, littérature, lettres, lettres russes, littérature russe, valentin raspoutine, valentin rasputin |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 03 janvier 2014

Martin Heidegger, Ernst Jünger, sur la ligne

Martin Heidegger, Ernst Jünger, sur la ligne

par Luc-Olivier d'Algange

ex: http://aucoeurdunationalisme.blogspot.com

La radicalité même de la différence entre ces deux âges du monde nous interdit généralement d'en percevoir la nature. Le plus grand nombre de nos contemporains, lorsqu'ils ne cultivent plus le mythe d'une modernité libératrice, en viennent à croire que le cours du temps n'a pas affecté considérablement les données fondamentales de l'existence humaine. Ils se trouvent si bien imprégnés par la vulgarité et les préjugés de leur temps qu'ils n'en perçoivent plus le caractère odieux ou dérisoire ou s'imaginent que ce caractère fut également répandu dans le cours des siècles. La simple raison s'avère ici insuffisante. Une autre expérience est requise qui appartient en propre au domaine de la beauté et de la poésie. L'accusation d'esthétisme régulièrement proférée à l'encontre de l'œuvre de Jünger provient de cette approche plus subtile des phénomènes propres au nihilisme. Certes, un esthétisme qui n'aurait aucun souci du vrai et du bien serait lui-même une forme de nihilisme accompli. Mais ce qui est à l'œuvre dans le cheminement de Jünger est d'une autre nature. Loin de substituer la considération du Beau à toute autre, il l'ajoute, comme un instrument de détection plus subtil aux considérations issues de l'approche rationnelle. La vertu de l'approche esthétique jüngérienne se révèle ainsi dans la confrontation avec le nihilisme. Pour distinguer les caractères propres aux deux âges du monde dont il est question, encore faut-il rendre son entendement sensible aussi bien à la beauté familière qu'à l'étrangeté.

Sur la ligne, les soufis diraient « sur le fil du rasoir », le moindre risque est bien d'être coupé en deux, ou d'être comme Janus, une créature à deux faces, contemplant à la fois le monde révolu et le monde futur. Que l'on veuille alors aveugler l'une ou l'autre face, en tenir pour la nostalgie pure du passé ou pour la croyance éperdue en l'avenir meilleur, cela ne change rien à l'emprise sur nous du nihilisme. Penser le nihilisme trans lineam exige ce préalable: penser le nihilisme de linea. Le réactionnaire et le progressiste succombent à la même erreur: ils sont également tranchés en deux. La fuite en avant comme la fuite en arrière interdit de penser la ligne elle-même. Toute l'attention du penseur-poète, c'est-à-dire du Cœur aventureux consistera à se tenir sur le méridien zéro afin d'interroger l'essence même du nihilisme, au lieu de se précipiter dans quelque échappatoire. En l'occurrence, Jünger, comme Heidegger nous dit que toute échappatoire, aussi pompeuse qu'elle soit (et comment ne pas voir que notre XXème siècle fut saturé jusqu'à l'écœurement par la pomposité progressiste et réactionnaire ?) n'est jamais qu'une impardonnable futilité.

Sur la ligne, nous dit Jünger, « c'est le tout qui est en jeu ». Sur la ligne, nous le sommes au moment où le nihilisme passif et le nihilisme actif ont laissé place au nihilisme accompli. Le site du nihilisme accompli est celui à partir duquel nous pouvons interroger l'essence du nihilisme. Après la destruction des formes, les temps ne sont plus à séparer le bon grain de l'ivraie. Le nihilisme, écrit Nietzsche est « l'hôte le plus étrange », et Heidegger précise, « « le plus étrange parce que ce qu'il veut, en tant que volonté inconditionnée de vouloir, c'est l'étrangeté, l'apatridité comme telle. C'est pourquoi il est vain de vouloir le mettre à la porte, puisqu'il est déjà partout depuis longtemps, invisible et hantant la maison. »

L'illusion du réactionnaire est de croire pouvoir « assainir », alors que l'illusion du progressiste est de croire pouvoir fonder cette étrangeté en une nouvelle et heureuse familiarité planétaire. Or, précise Heidegger: « L'essence du nihilisme n'est ni ce qu'on pourrait assainir, ni ce qu'on pourrait ne pas assainir. Elle est l'in-sane, mais en tant que telle elle est une indication vers l'in-demne. La pensée doit-elle se rapprocher du domaine de l'essence du nihilisme, alors elle se risque nécessairement en précurseur, et donc elle change. »

La destruction, qui est le signe du nihilisme moderne, serait donc à la fois l'instauration généralisée de l'insane et une indication vers l'indemne. Si le poète et le penseur doivent parier sur l'esprit qui vivifie contre la lettre morte, il n'est pas exclu que par l'accomplissement du nihilisme, c'est-à- dire la destruction de la lettre morte, une chance ne nous soit pas offerte de ressaisir dans son resplendissement essentiel l'esprit qui vivifie. Le précurseur sera ainsi celui qui ose et qui change et dont la pensée, à ceux qui se tiennent encore dans le nihilisme passif ou le nihilisme actif, paraîtra réactionnaire ou subversive alors qu'elle est déjà au-delà, ou plus exactement au-dessus.

Comment ne point aveugler l'un des visages de Janus, comment tenir en soi, en une même exigence et une même attention, la crainte, l'espérance, la déréliction et la sérénité ? Il n'est pas vain de recourir à la raison, sous condition que l'on en vienne à s'interroger ensuite sur la raison même de la raison. Que nous dit cette raison agissante et audacieuse ? Elle nous révèle pour commencer qu'il ne suffit pas de reconnaître dans tel ou tel aspect du monde moderne l'essence du nihilisme. La définition et la description du nihilisme, pour satisfaisantes qu’elles paraissent au premier regard, nous entraînent pourtant dans le cercle vicieux du nihilisme lui-même, avec son cortège de remèdes pires que les maux et de solutions fallacieuses. Vouloir localiser le nihilisme serait ainsi lui succomber à notre insu. Cependant l'intelligence humaine répugne à renoncer à définir, à discriminer: elle garde en elle cette arme mais dépourvue de Maître d'arme et d'une légitimité conséquente, elle en use à mauvais escient. Telle est exactement la raison moderne, détachée de sa pertinence onto-théologique. Etre sur la ligne, penser l'essence du nihilisme accompli, c'est ainsi reconnaître le moment de la défaillance de la raison. Cette reconnaissance, pour autant qu'elle pense l'essence du nihilisme accompli ne sera pas davantage une concession l'irrationalité. « Le renoncement à toute définition qui s'exprime ici, écrit Heidegger, semble faire bon marché de la rigueur de la pensée. Mais il pourrait se faire aussi que seule cette renonciation mette la pensée sur le chemin d'une certaine astreinte, qui lui permette d'éprouver de quelle nature est la rigueur requise d'elle par la chose même ».

Le Cœur aventureux jüngérien est appelé à se faire précurseur et à suivre « le chemin d'une certaine astreinte ». La raison n'est pas congédiée mais interrogée; elle n'est point récusée, en faveur de son en-deçà mais requise à une astreinte nouvelle qui rend caduque les définitions, les descriptions, les discriminations dont elle se contentait jusqu'alors. « Que l'hégémonie de la raison s'établisse comme la rationalisation de tous les ordres, comme la normalisation, comme le nivellement, et cela dans le sillage du nihilisme européen, c'est là quelque chose qui donne autant à penser que la tentative de fuite vers l'irrationnel qui lui correspond. » A celui qui se tient sur la ligne, en précurseur et soumis à une astreinte nouvelle, il est donné de voir le rationnel et l'irrationnel comme deux formes concomitantes de superstition.

Le Cœur aventureux jüngérien est appelé à se faire précurseur et à suivre « le chemin d'une certaine astreinte ». La raison n'est pas congédiée mais interrogée; elle n'est point récusée, en faveur de son en-deçà mais requise à une astreinte nouvelle qui rend caduque les définitions, les descriptions, les discriminations dont elle se contentait jusqu'alors. « Que l'hégémonie de la raison s'établisse comme la rationalisation de tous les ordres, comme la normalisation, comme le nivellement, et cela dans le sillage du nihilisme européen, c'est là quelque chose qui donne autant à penser que la tentative de fuite vers l'irrationnel qui lui correspond. » A celui qui se tient sur la ligne, en précurseur et soumis à une astreinte nouvelle, il est donné de voir le rationnel et l'irrationnel comme deux formes concomitantes de superstition.

Qu'est-ce qu'une superstition? Rien d'autre qu'un signe qui survit à la disparition du sens. La superstition rationaliste emprisonne la raison dans l'ignorance de sa provenance et de sa destination, et dans sa propre folie planificatrice, de même que la superstition religieuse emprisonne la Théologie dans l'ignorance de la vertu d'intercession de ses propres symboles. L'insane au comble de sa puissance généralise cette idolâtrie de la lettre morte, de la fonction détachée de l'essence qui la manifeste. Aux temps du nihilisme accompli le dire ayant perdu toute vertu d'intercession se réduit à son seul pouvoir de fascination, comme en témoignent les mots d'ordre des idéologies et les slogans de la publicité. Dans sa nouvelle astreinte, le précurseur ne doit pas être davantage enclin à céder à la superstition de l'irrationnel qu'à la superstition de la raison. En effet, souligne Heidegger, « le plus inquiétant c'est encore le processus selon lequel le rationalisme et l'irrationalisme s'empêtrent identiquement dans une convertibilité réciproque, dont non seulement ils ne trouvent pas l'issue, mais dont ils ne veulent plus l'issue. C'est pourquoi l'on dénie à la pensée toute possibilité de parvenir à une vocation qui se tiennent en dehors du ou bien ou bien du rationnel et de l'irrationnel. »

La nouvelle astreinte du précurseur consistera précisément à rassembler en soi les signes et les intersignes infimes qui échappent à la fois au rationalisme planificateur et à l'irrationalisme. La difficulté féconde surgit au moment où l'exigence la plus haute de la pensée, sa requête la plus radicale devient un refus de l'alternative en même temps qu'un refus du compromis. Ne point choisir entre le rationnel et l'irrationnel, et encore moins mélanger ce qu'il y aurait « de mieux » dans l'un et dans l'autre, telle est l'astreinte nouvelle de celui qui consent héroïquement à se tenir sur le méridien zéro du nihilisme accompli. Conscient de l'installation planétaire de l'insane, son attention vers l'indemne doit le porter non vers une logique thérapeutique, qui traiterait les symptômes ou les causes, mais au cœur même de cette attention et de cette attente pour lesquels nous n'avons pas trouvé jusqu'à présent d'autre mots que ceux de méditation et de prière, quand bien même il faudrait désormais charger ces mots d'une signification nouvelle et inattendue.

L'entretien sur la ligne d’Ernst Jünger et de Martin Heidegger ouvre ainsi à la raison qui s'interroge sur ses propres ressources des perspectives qui n'ont rien de passéistes et dont on est même en droit de penser désormais qu'elles seules n'apparaissent pas comme touchées dans leur être même par le passéisme, étant entendu que le passéisme progressiste est peut-être, par son refus de retour critique sur lui-même, et par la méconnaissance de sa propre généalogie, plus réactionnaire encore dans son essence que le passéisme nostalgique ou néoromantique.

L'attention du précurseur, sa théorie, au sens retrouvé de contemplation, sera d'abord un art de ne pas refuser de voir. Quant à l'astreinte nouvelle, elle éveillera la possibilité d'une autre hiérarchie des importances où le vol de l'infime cicindèle n'aura pas moins de sens que les désastres colossaux du monde moderne. " De même, écrit Jünger, les dangers et la sécurité changent de sens". Comment ne pas voir que les modernes doivent précisément à leur goût de la sécurité les pires dangers auxquels ils se trouvent exposés ? Et qu'à l'inverse l'audace, voire la témérité de quelques uns furent toujours les prémisses d'un établissement dans ces grandes et sereines sécurités que sont les civilisations dignes de ce nom ?

L'homme moderne, ne croyant qu'à son individualité et à son corps, désirant d'abord la sécurité de son corps, ne désirant, en vérité, rien d'autre, est l'inventeur du monde où la vie humaine est si dévaluée qu'il n'y a presque plus aucune différence entre les vivants et les morts. C'est bien pourquoi le massacre de millions d'êtres humains dans son siècle "rationnel, démocratique et progressiste" le choque moins que la violence d'un combat antique ou d'une échauffourée médiévale, pour autant que sa sécurité, son individualité ou, dans une plus faible mesure, celles des siens, ont été épargnées. Le nihilisme de sa propre sécurité s'établit dans le refus de voir le nihilisme du péril auquel il n'a cessé de consentir que d'autre que lui fussent livrés, et se livrant ainsi lui-même à leur vindicte. Les Empereurs chinois savaient ce que nous avons oublié, eux qui considéraient leurs armes défensives comme les pires dangers pour eux-mêmes. Les Cœurs aventureux, ou selon la terminologie heideggérienne, les précurseurs, trouveront la plus grande sécurité dans leur consentement même à se reconnaître dans le site du plus grand danger. De même qu'au cœur de l'insane est l'incitation vers l'indemne, au cœur du danger se trouve le site de la plus grande sécurité possible. Comment sortir indemne de l'insane péril (qui prétend par surcroît avoir inventé la sécurité comme Monsieur Jourdain la prose !) où nous a précipité le nihilisme ? Quelle est la ligne de risque ?

Certes, le méridien zéro n'est nullement ce « compteur remis à zéro » dont rêve la sentimentalité révolutionnaire. Ce méridien, s'il faut préciser, n'est point une métaphore de la table rase, ou le site d'un oubli redimant. Le méridien zéro est exactement le lieu où rien ne peut être oublié, où toute sollicitation extérieure répond d'une réminiscence, comme le son répond à la corde que l'on touche, où l'empreinte ne prétend point à sa précellence sur le sceau. Ce qui advient, pas davantage que ce qui fut, ne peut prétendre à un autre titre que celui d'empreinte, le sceau étant l'hors-d'atteinte lui-même: l'indemne qui gît au secret du cœur du plus grand danger. La ligne de risque de la vie et de l'œuvre jüngériennes répond de cette certitude acquise sur la ligne.

Toute interrogation fondamentale concernant la liberté est liée à la Forme. Si le supra-formel, en langage métaphysique, bien l'absolu de la liberté, le propre de ceux que l'hindouisme nomme les libérés vivants, l'informe, quant à lui, est le comble de la soumission. La question de la Forme se tient sur cette ligne critique, sur ce méridien zéro qui ouvre à la fois sur le comble de l'esclavage et sur la souveraineté la plus libre qui se puisse imaginer. Dès Le Travailleur, et ensuite à travers toute son œuvre, Jünger poursuivit, comme nous l'avons vu, une méditation sur la Forme. Or, cette méditation, platonicienne à maints égards, est aussi inaugurale si l'on ose la situer non plus dans l'histoire de la philosophie, comme un moment révolu de celle-ci mais sur la ligne, comme une promesse de franchissement de la ligne. Ce qu'il importe désormais de savoir, c'est en quoi la Forme contient en elle à la fois la possibilité du déclin dans le nihilisme (dont l'étape d'accomplissement serait la confusion de toutes les formes: l'uniformité) et la possibilité d'une recréation de la Forme, voire d'un dépassement de la Forme dans une souveraineté jusqu'ici encore impressentie. Par les figures successivement interrogées du Travailleur, du Rebelle et de l'Anarque, Jünger s'achemine vers cette souveraineté. Pour qu'il y eût une Forme, au sens grec d'Idéa, et non seulement au sens moderne de « représentation », il importe que la réalité du sceau ne soit pas oubliée.

Une lecture extrêmement sommaire des œuvres de Jünger et de Heidegger donnerait à penser que lorsque Heidegger tenterait un dépassement, voire un renversement ou une « déconstruction » du platonisme, Jünger, lui s'en tiendrait à une philosophie strictement néo-platonicienne. Le dépassement heideggérien de la métaphysique, qui tant séduisit ses disciples français « déconstructivistes » (et surtout acharnés, sous l'influence de Marx, à détacher toute philosophie de ses origines théologiques) laissa, et laisse encore, d'immenses carrières à l'erreur. Les modernes qui instrumentalisent l'œuvre de Heidegger en vue d'un renversement du platonisme et de la métaphysique méconnaissent que, pour Heidegger, dépassement de la métaphysique signifie non point destruction de la métaphysique mais bien couronnement de la métaphysique. Il s'agit moins, en l'occurrence, de se libérer de la métaphysique que de libérer la métaphysique.

Il n'est pas question de déconstruire la métaphysique, pour en faire table rase, mais d'en établir la souveraineté en la dépassant par le haut, c'est à dire par la question de l'être. Pour un grand nombre d'exégètes français la différence essentielle entre une antimétaphysique et une métaphysique couronnée demeure obscure. Heidegger ne reproche point à la métaphysique de s'interroger sur l'essence, il lui impose au contraire, comme une astreinte nouvelle, de s'interroger plus essentiellement encore sur l'essence de son propre déploiement dans le Logos. A la métaphysique déclinante des théologies exotériques, des sciences humaines, de la didactique, de la Technique et du matérialisme, Heidegger oppose une interrogation essentielle sur le déclin lui-même.

En établissant clairement son dépassement de la métaphysique comme un couronnement de la métaphysique, Heidegger suggère qu'il y a bien deux façons de dépasser, l'une par le bas (qui serait le matérialisme) l'autre par le haut, et qui est de l'ordre du couronnement. Loin de vouloir « en finir », au sens vulgaire, avec la métaphysique, Heidegger entend en rétablir sa royauté. Par l'interrogation incessante sur les fins et sur la finalité de la métaphysique, Heidegger œuvre à la recouvrance de la métaphysique et non à sa solidification. Qu'est-ce qu'une métaphysique couronnée ? De quelle nature est ce dépassement par le haut ? Que le déclin de la métaphysique eût conduit celle-ci de la didactique à la superstition de la technique, du nihilisme passif jusqu'au nihilisme accompli, en témoignent les théories modernes du langage et l'humanisme qui ne voit en l'homme qu'un animal « amélioré » par le langage. Ce que Heidegger reproche à ces théories du langage et de l'homme est d'ignorer la question de l'essence de l'homme et de l'essence du langage, et d'être en somme, des métaphysiques oublieuses de leurs propres ressources.

Le dialogue entre Jünger et Heidegger, que le bon lecteur ne doit pas circonscrire à l'échange hommagial et épistolaire sur le passage de la ligne mais étendre aussi aux autres œuvres, prend tout son sens à partir des méditations jüngériennes sur le langage et l'herméneutique. En effet, loin de rompre avec la source théologique, Heidegger en fut le revivificateur éminent par l'art herméneutique qu'il ne cessa d'exercer au contact des œuvres anciennes, les présocratiques, Aristote, ou modernes, Hölderlin, Trakl, ou Stephan George. De même Jünger, en amont des gloses, des analyses et des explications poursuivit le dessein de retrouver, dans les signes et les intersignes, la trace des dieux enfuis. Entre les noms des dieux et leurs puissances, entre l'empreinte et le sceau, entre le langage et la langue, entre ce que doit être dit et ce qui est dit, l'Auteur s'établit avec une inquiétude créatrice. Ce serait se méprendre grandement sur la méditation sur la Forme qui est à l'œuvre dans les essais de Jünger que de n'y voir qu'une reproduction d'un néoplatonisme acquis et défini une fois pour toute, et réduit, pour ainsi dire à des schémas purement scolaires ou didactiques. Se tenir sur la ligne, c'est déjà refuser d'être dans la pure représentation. Entre la présence et son miroitement se joue toute véritable et féconde inquiétude spéculative.

Luc-Olivier d’Algange

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ernst jünger, martin heidegger, heidegger, philosophie, allemagne, révolution conservatrice, lettres, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres allemandes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 01 janvier 2014

Arthur C. Clarke, La Cité et les Astres

Chronique littéraire: Arthur C. Clarke, La Cité et les Astres, 1956.

Ex: http://cerclenonconforme.hautetfort.com

Le Paradis Galactique perdu

Ecrit il y a plus d’un demi siècle, la Cité et les Astres est un roman-clé de la science-fiction dite « classique ». C’est aussi l’un des ouvrages les plus riches d’Arthur C. Clarke, l’auteur britannique de 2001, l’Odyssée de l’Espace.

Dans un futur extrêmement lointain, Diaspar – anagramme de Paradis - est le dernier bastion d’humanité sur terre. Une bonne partie de l’univers a été ravagé par une guerre entre empires galactiques, et les rares hommes survivants ont constitué une sorte de base autonome durable ultime au cœur de la vaste étendue désertique que constitue désormais la Terre, à mi-chemin entre Matrix et la Cité idéale de Brunelleschi. Un jeune adolescent un peu à part, Alvin, choisit de se détourner du petit confort ultime de Diaspar pour diriger son regard vers les Astres, vers les contrées lointaines, qui terrifient ses congénères…

Jusque-là, rien de bien original. Et pourtant, il me semble qu’on aurait tort de passer son chemin.

Ce qui frappe dans cet ouvrage, c’est tout d’abord le foisonnement des sujets abordés. On y trouve en effet la plupart des thèmes chers aux auteurs de SF classiques : l’immortalité, l’eugénisme, la mise en question du divin, mais aussi un certain nombre d’éléments propres au space-opéra : les robots, les extra-terrestres et autres envahisseurs, les pouvoirs télépathiques, télékinésiques, la téléportation, etc., le tout mâtiné d’un certain nombre d’éléments issus des civilisations indo-européenne : l’ aspect cyclique du temps, la philosophie, l’omniprésence de l’art - mosaïques, sculptures intégrées à l’espace publique -, permanence de la vie culturelle, de l’architecture qui défie les âges…

A première vue, Diaspar se présente comme une sorte de société idéale : plutôt qu’à un monde post-apocalyptique, on est confronté à un univers propret, auto-suffisant et quasi-immuable, caractérisé par une sorte d’état de béatitude perpétuel. La guerre, la maladie, et même la mort elle-même ont été éradiqués.

Même si le terme n’est jamais mentionné directement, on ne peut s’empêcher de songer à un retour à l’Âge d’or, après plusieurs millénaires d’une interminable décadence intergalactique, ayant atteint son paroxysme avec la destruction de la majorité de l’humanité par de mystérieux Envahisseurs : ainsi la cité s’organise-t-elle autour d’une colline, réminiscence de la montagne sacrée, de l’axe cosmique, du nombril de la terre[1], au sommet de laquelle se trouve un édicule abritant la statue du Créateur de la cité, un peu à la manière d’un temple ; de plus, la réincarnation et la réminiscence des vies antérieures assure virtuellement sur Diaspar l’immortalité, et donne d’ailleurs à la mort un visage totalement différent de celui qu’on lui trouve habituellement : certains protagonistes, dans le livre de Clarke, se donnent volontairement la mort pour échapper à tout problème qui leur semble de trop grande envergure, presque sans état d’âme, parce qu’ils sont assurés de se réincarner plus tard. L’homme n’ayant plus à craindre la mort, les problèmes existentiels récurrents subissent des inflexions monumentales. On trouve aussi le thème de la prééminence de l’esprit sur la matière, puisque les hommes de Diaspar peuvent créer et détruire à volonté tous les objets de la vie quotidienne, par la seule force de la pensée.

Bien que Clarke ne fournissent que peu de détails quant à ces étranges pouvoirs, il semble que toutes ces mystérieuses facultés psychiques soient fournis par une sorte de processeur hypertrophié, tout à la fois cœur et cerveau de cette cité idéale aux allures de Paradis perdu et pourtant dystopique à maints égards…

Le versant dystopique

Car ce mystérieux Âge d’or n’aurait probablement pas trouvé grâce aux yeux d’un Guénon ou d’un Evola. La première dissonance perceptible dans l’ouvrage de Clarke consiste en une phobie insurmontable pour tous les habitants de Diaspar : celle de l’éventualité même de se confronter à quoi que ce soit ayant un rapport avec le monde extérieur à la cité. Les grands espaces inspirent aux hommes de Diaspar une peur qui semble venue du fond des âges. Ce premier élément discordant est très révélateur de la mentalité d’une société qui pense avoir atteint une sorte d’état de grâce en empruntant la voie de la technologie. Car au-delà des apparences, Diaspar n’est rien d’autre qu’une société régie en totalité par les seuls moyens matériels. Les robots sont quasi-invisibles mais omniprésents, et assurent le bon fonctionnement de la Cité ; un cerveau-machine, appelé Calculatrice Centrale, fait office de divinité locale - et universelle en raison du caractère unique de Diaspar. Les hommes de Diaspar se sont donné les moyens matériels de maîtriser à la perfection leur microcosme et chacun de ses composants, et il semble donc tout naturel que ce soit une machine omnipotente qui leur tienne lieu d’entité divine.

Le confort de tous les instants implique un autre phénomène : la seule notion d’effort physique, et partant, tout ce qui peut constituer une aventure authentique, est devenue étrangère aux habitants de la cité ; le héros du roman en fera d’ailleurs l’expérience au cours de ses pérégrinations. Dès lors un grand nombre de qualités humaines parfois triviales mais absolument essentielles - le courage, la patience, le dévouement… ne trouve plus de champ d’expression. Il en va de même des liens entre les hommes, qui se trouvent totalement dénaturés : immortels, les habitants de Diaspar se connaissent ou se reconnaissent tous, mais ne sont même pas en mesure d’éprouver l’authenticité des liens qui semblent pourtant unir certain d’entre eux : l’amitié comme l’amour sont sur Diaspar des abstractions supplantées par des éléments plus directement sensibles et superficiels, comme la simple attirance physique par exemple.

Les dissemblances avec la société traditionnelle apparaissent à mesure que l’on progresse dans la lecture de La Cité et les Astres. La conception de la cellule familiale, par exemple, est réduite à peau de chagrin : la procréation elle-même n’a plus de finalité génésique ; la maternité n’existe plus, et l’éducation à proprement parler se réduit à une simple formalité, les individus de Diaspar sortent préfabriqués idéalement d’un « temple de la Création », déjà physiquement âgés d’une vingtaine d’années, et les parents de chaque individu sont attribués de manière aléatoire.

Ajoutons qu’au cours du roman, l’auteur nous gratifie d’une confrontation particulièrement éclairante avec un autre type de société régie par un système de valeurs radicalement différent, ce qui a le mérite de procurer plus de profondeur encore au propos, et de donner un second souffle à l’intrigue.

Un bon exemple de roman de science-fiction intelligent

Le microcosme que Clarke nous fait entrevoir semble donc idéal, et fondé en apparence sur un système traditionnel ; pourtant il ne faut pas longtemps pour découvrir au contraire une société hédoniste, nombriliste et dont la vanité est à peine voilée par les avancées technologiques éblouissantes, qui agissent comme autant de narcotiques sur la conscience de chacun. Bien à l’abri au cœur de leur petit monde contemplatif, esthétisant, intellectualisant, désacralisé au possible, aux antipodes des protagonistes de la République du Mont Blanc de Saint Loup, les habitants de Diaspar sont des « super-hommes » sur le plan physique ou même culturel, mais sont à des années-lumière du surhomme de Nietzsche. Une vie passée à méditer et à créer n’a aucun sens, aucune valeur, si rien ne vient mettre quoi que ce soit en péril, si rien ne vient troubler la quiétude égocentrique de l’homme, car c’est seulement lorsqu’il est confronté aux difficultés que celui-ci est capable de s’élever au-dessus de sa médiocre condition.

Le microcosme que Clarke nous fait entrevoir semble donc idéal, et fondé en apparence sur un système traditionnel ; pourtant il ne faut pas longtemps pour découvrir au contraire une société hédoniste, nombriliste et dont la vanité est à peine voilée par les avancées technologiques éblouissantes, qui agissent comme autant de narcotiques sur la conscience de chacun. Bien à l’abri au cœur de leur petit monde contemplatif, esthétisant, intellectualisant, désacralisé au possible, aux antipodes des protagonistes de la République du Mont Blanc de Saint Loup, les habitants de Diaspar sont des « super-hommes » sur le plan physique ou même culturel, mais sont à des années-lumière du surhomme de Nietzsche. Une vie passée à méditer et à créer n’a aucun sens, aucune valeur, si rien ne vient mettre quoi que ce soit en péril, si rien ne vient troubler la quiétude égocentrique de l’homme, car c’est seulement lorsqu’il est confronté aux difficultés que celui-ci est capable de s’élever au-dessus de sa médiocre condition.

Toute ressemblance avec une société existante ou ayant existé n’est donc plus tout à fait fortuite : l’idéal d’une société capitaliste, fondée sur la soumission de l’essentiel aux seuls impératifs économiques, censés apporter le Salut à l’homme occidental par le confort matériel, sécularisée jusqu’à la corde, ne constitue-t-il pas un prototype de Diaspar ?

Les parallèles que l’on pourrait établir avec le monde actuel ne s’arrêtent pas là : on peut lire aussi La Cité et les Astres comme un prolongement de 1984, puisque la société qu’on y trouve est bâtie sur une série de mensonges complaisamment entretenus par un système donné. Tout comme dans 1984, un seul individu, le personnage principal de l’œuvre, semble avoir les yeux décillés. C’est à partir de son expérience, dissidente, déstabilisante, comme le serait un virus dans un système informatique, que se développe le roman.

Plusieurs éléments du roman de Clarke renvoient au thème de la religion, parfois d’une manière très allusive ; de façon générale on peut remarquer que l’auteur met en cause, si ce n’est la spiritualité dans son ensemble, au moins l’idéal dogmatique des religions révélées. Je ne vous en dis pas davantage afin de ne pas déflorer ce qui est sans doute l’un des passages les plus surprenants et les plus inventifs de tout le roman, mais je ne ferais pas preuve d’une grande honnêteté en présentant ce livre comme un plaidoyer pour un retour à la spiritualité. A mon avis Clarke a plutôt choisi dans cet ouvrage d’insister sur l’importance vitale de l’éducation, de l’épreuve, et d’autres vertus propres à l’homme – ce qui, dans le fond, n’a rien de théologique, mais présente au moins le mérite de faire appel à un ensemble de valeurs supérieures.

L’auteur nous livre, au final, une vision relativement positive de ce que peut devenir l’homme dans une société hypermatérialiste, puisque d’une part la société de Diaspar échappe à la guerre de tous contre tous, et que d’autre part, à l’inverse de ce que l’on peut lire dans certains classiques d’anticipation tels que 1984 ou Farenheit 451, on trouve sur Diaspar des aspects de vie culturelle ou philosophique. Mais les habitants de cette petite utopie sont dépourvus de vitalité, de sève, de force intérieure ; la vie sur Diaspar se développe exclusivement sur le plan horizontal. Ce roman met en scène de façon assez intelligente l’éradication de la troisième dimension de l’homme, qui fait que chaque individu devient non pas un être humain doté de sens critique, mai un logiciel incarné.

Lyderic

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise, arthur c. clarke, science-fiction |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 30 décembre 2013

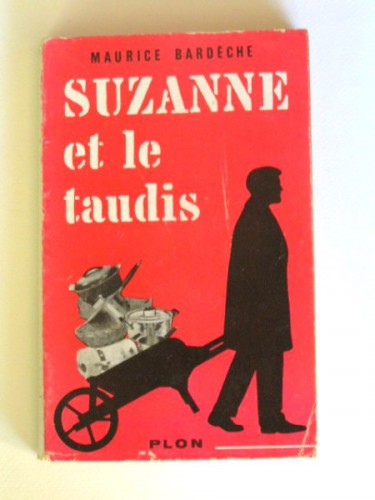

Chronique littéraire: Maurice Bardèche, Suzanne et le Taudis

Chronique littéraire: Maurice Bardèche, Suzanne et le Taudis, Plon, 1957

Ex: http://cerclenonconforme.hautetfort.com

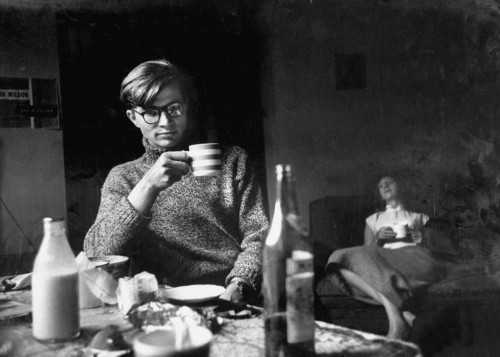

« Je rendais grâce au ciel d’avoir fait de moi un cuistre obscur. Et aussi de m’avoir donné un taudis d’une pièce et demie, quand la moitié de l’Europe logeait dans des caves. »

1 – Maurice Bardèche et la politique

2 – Le Taudis, frêle esquif au milieu des flots tumultueux

3 – Un récit sur la condition de l’écrivain dissident

1 – Maurice Bardèche et la politique

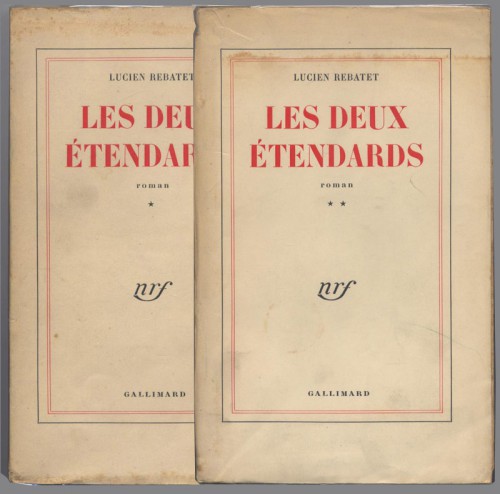

La production littéraire de Maurice Bardèche ayant trait à la politique, radicale dans son fond et souvent très attrayante dans sa forme, n’est pas le fruit de l’assimilation particulièrement réussie de la pensée d’illustres prédécesseurs maurassiens, ni même la somme d’un nombre quelconque de réflexions antérieures, forgées à chaud à cette époque désormais révolue où l’expression « presse d’opinion » avait encore un sens. Au contraire, comme le révèle Jacques Bardèche, son propre fils, dans l’entrevue qu’il a bien voulu accorder à nos camarades de MZ récemment, Maurice Bardèche a commencé à vraiment s’intéresser à la politique à partir d’un moment historique bien précis : l’exécution de son ami et beau-frère Robert Brasillach, le 6 février 1945. De fil en aiguille, la pensée politique de Bardèche a donc émergé en réaction à un certain nombre d’événements, qu’il juge insupportables : l’exécution sommaire et injustifiée de son ami, les horreurs de l’épuration, le climat d’hypocrisie exacerbée d’après-guerre… Pour autant, jamais la plume de Bardèche n’accouche de propos haineux, contrairement à ce que laisse souvent entendre une certaine littérature engagée à gauche. Bien loin des pamphlets outranciers de Céline, des présages sombres et du pessimisme de Drieu, des intransigeances de Rebatet ou de Coston, la prose de Bardèche invite souvent le lecteur à entrevoir des rivages plus sereins : la recherche d’une forme d’équilibre, de justice, ou tout simplement de common decency, pour reprendre la formule d’Orwell. La pensée de Bardèche, c’est peut-être d’abord l’expression du bon sens appliquée à la politique. C’est un véritable antidote à la langue de bois.

La production littéraire de Maurice Bardèche ayant trait à la politique, radicale dans son fond et souvent très attrayante dans sa forme, n’est pas le fruit de l’assimilation particulièrement réussie de la pensée d’illustres prédécesseurs maurassiens, ni même la somme d’un nombre quelconque de réflexions antérieures, forgées à chaud à cette époque désormais révolue où l’expression « presse d’opinion » avait encore un sens. Au contraire, comme le révèle Jacques Bardèche, son propre fils, dans l’entrevue qu’il a bien voulu accorder à nos camarades de MZ récemment, Maurice Bardèche a commencé à vraiment s’intéresser à la politique à partir d’un moment historique bien précis : l’exécution de son ami et beau-frère Robert Brasillach, le 6 février 1945. De fil en aiguille, la pensée politique de Bardèche a donc émergé en réaction à un certain nombre d’événements, qu’il juge insupportables : l’exécution sommaire et injustifiée de son ami, les horreurs de l’épuration, le climat d’hypocrisie exacerbée d’après-guerre… Pour autant, jamais la plume de Bardèche n’accouche de propos haineux, contrairement à ce que laisse souvent entendre une certaine littérature engagée à gauche. Bien loin des pamphlets outranciers de Céline, des présages sombres et du pessimisme de Drieu, des intransigeances de Rebatet ou de Coston, la prose de Bardèche invite souvent le lecteur à entrevoir des rivages plus sereins : la recherche d’une forme d’équilibre, de justice, ou tout simplement de common decency, pour reprendre la formule d’Orwell. La pensée de Bardèche, c’est peut-être d’abord l’expression du bon sens appliquée à la politique. C’est un véritable antidote à la langue de bois.

Suzanne et le Taudis s’inscrit parfaitement bien dans cette forme littéraire très particulière, issue d’une radicalité qui ne sacrifie jamais à l’outrance ou à la provocation. Il en résulte un véritable pamphlet dans un gant de velours

2 - Le Taudis, frêle esquif au milieu des flots tumultueux

D’un point de vue formel, Suzanne et le Taudis se présente comme un récit plein de saveurs axé sur les conditions matérielles de Maurice Bardèche et de sa femme, Suzanne, la sœur de Robert Brasillach, après que le couple, qui habitait jusqu'alors avec celui-ci, se soit vu dépossédé de son appartement, "réputé être indispensable aux nécessités de la Défense nationale" au moment de la Libération.

De logis insalubre en appartement de fortune, en passant, bien sûr, par la case prison, sans jamais d'atermoiements, toujours avec un ton caustique, Bardèche nous livre un florilège de souvenirs où l’on entrevoit pêle-mêle d’indolentes femmes de chambres, de vertueux jeunes garçons animés d’idéaux maudits, d’improbables compagnons de cellules, mais aussi de bien espiègles marmots.

On croise au fil des pages de nombreux intellectuels plus ou moins proches de Bardèche : François Brigneau, Roland Laudenbach, le célèbre dessinateur Jean Effel, Marcelle Tassencourt et Thierry Maulnier, Henri Poulain, ou encore Marcel Aymé, à propos duquel Bardèche écrit : « il a l’air d’un saint de pierre du douzième siècle. Il est long, stylisé, hiératique, il s’assied tout droit, les mains sagement posées sur les genoux comme un pharaon et il fait descendre sur ses yeux une sorte de taie épaisse pour laquelle le nom de paupière m’a toujours paru un peu faible ». Cette icône byzantine incarnée, sans partager nécessairement les idées politiques de Bardèche, engage pourtant une campagne en faveur de celui-ci à l’occasion de son procès, dans un article publié dans Carrefour le 26 mars 1952, intitulé « La Liberté de l’écrivain est menacée ».

On découvre aussi dans ce roman, bien entendu, Suzanne, toute entière dévouée à l'éducation de ses enfants, fière, pragmatique, essayant tant bien que mal d'endiguer le flot continuel de trouvailles plus ou moins bien venues de la part de sa progéniture, au milieu des intellectuels pas toujours fréquentables que Bardèche recevait parfois chez lui. A ce titre, on pourra louer la lucidité de l’auteur quant aux travers récurrents et indéboulonnables des individus, parfois tout à fait valeureux mais bien trop souvent en dehors du réel, qui se réclamaient du fascisme encore après la guerre. Bardèche fustige leurs travers d'alcooliques ou leurs élans despotiques sans pour autant leur tourner le dos, à aucun moment.

A travers ces tranches de vie tour à tour drôles, touchantes, poignantes, Maurice Bardèche, de son style limpide, dresse l’autoportrait d’un écrivain voué à l’exclusion et à la misère, un homme sincère et droit dans ses bottes, volontiers porté sur l’autodérision, terriblement humain, au fond.

3 – Un récit sur la condition de l’écrivain dissident

Maurice Bardèche aurait pu poursuivre la très belle carrière qu’il s’était taillée avant la guerre. Successivement élève de ENS, agrégé de Lettres, docteur ès Lettres, professeur à la Sorbonne puis à l’université de Lille, on lui doit d’admirables ouvrages encore aujourd’hui unanimement reconnus sur Balzac, Flaubert, Stendhal, Bloy et Céline.