"Vivre-ensemble": quand l'Etat dépossède la nation

Ex: http://ideocratie2012.blogspot.com

Nous reproduisons en intégralité une réflexion profonde et exigeante consacrée aux impératifs de l’être-en-commun. Loin des formules en vogue dans le marketing politique, tel le bien mièvre « vivre-ensemble », il rappelle que la relation vient en premier dans une société authentique, et rejaillit même en célébration dans la communauté de vie, tandis que le contrat tisse une toile artificielle dans laquelle l’Etat s’évertue à mettre en forme les individus normés (i.e. citoyens de droit) en fonction de sa logique comptable.

Comme François Hollande s'est toujours plus intéressé à l'état de l'opinion qu'à celui de la France, il affirmait sans rire, pendant l'été 2015 : « on voit bien qu'il y a des sujets qui s'installent, comme le terrorisme, la question de l'immigration, l'islam, etc ». Des sujets qui s'installent ! Derrière ces sujets se sont sans doute installées, préalablement, certaines réalités dont il est permis de penser qu'elles ont contribué au délitement des liens profonds de la nation et à l'inquiétude des Français. Les effets de ce délitement souterrain apparaissent désormais au grand jour, mais nos dirigeants se souciant fort peu d'en prendre l'exacte mesure, ils persistent dans les mêmes discours. Ainsi nous assène-t-on plus que jamais les prétendus mérites du fameux « vivre-ensemble ».

En ces temps de novlangue triomphante, personne n'ignore le sens idéologique de cette expression, dont la neutralité première est passée à l'arrière-plan depuis belle lurette. Le « vivre-ensemble » renvoie ainsi à un type de rassemblement, censé être pacifique, d'individus et de groupes disparates, en lieu et place d'un mode de socialité reposant sur le partage d'une « chose commune ». De fait, c'est un slogan politique. On pourrait le croire emprunté à une publicité vantant la convivialité de surface ayant cours entre membres d'un vulgaire club de vacances, tant il est proche de l'imaginaire puéril contemporain. Toujours est-il qu'il a désormais du mal à convaincre. Il semblerait en effet que de plus en plus de gens ne veulent plus vivre ensemble. Ce que traduisent à leur manière les communautarismes en plein essor, mais aussi le rejet de ceux-ci exprimé dans les urnes, ou encore les tensions multiples au quotidien. Pour autant, envers et contre tout, nos élites ne cessent de promouvoir la coexistence de communautés hétérogènes, la grande juxtaposition blafarde. Les différents communautarismes ne sont d'ailleurs perçus par une partie de ces « élites » que sous la forme d'une velléité passagère, d'une simple étape. Dans l'esprit des Attali, manifestement inspirés par des horizons inconnus à l'homme ordinaire, c'est l'atomisation nécessairement pacifique du corps social qui doit ainsi l'emporter à terme sur toutes velléités contraires, celles-ci étant momentanément utiles cependant pour affaiblir le sentiment du partage d'une « chose commune ».

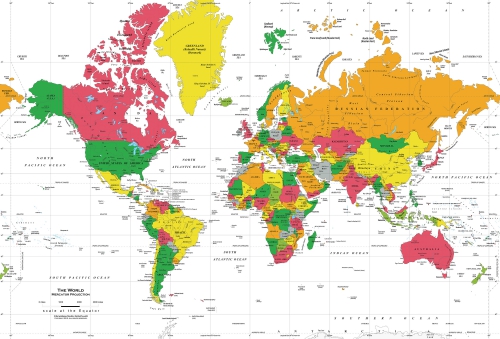

Il est utile de le préciser, la notion de « chose commune », l'un des fondements du politique, n'est pas extensible à l'infini. N'en déplaise aux politiciens qui s'emparent parfois de l'expression dans le but étrange de justifier le mouvement vers l'universellement indifférencié, ce nivellement général dont les ravages s'étendent sous nos yeux. L'idée d'un ensemble humain indifférencié renvoie certes à un certain type de commun, de communauté, mais on peut se demander s’il s'agit là d'une communauté proprement humaine, c'est-à-dire dont les liens constitutifs sont d'une certaine qualité, ou si l’on n’est pas plutôt en présence d'un groupe d'individus dont les liens, à force d’être mécanisés, réifiés, relèvent en définitive d'un ordre infra-humain. Reconnaissons-le, loin de constituer un progrès, cette caricature du commun, son double parodique, nous ramène vers les temps les plus archaïques, vers cet état d'avant le devenir-homme tel que l'imaginait Vico au XVIIIe siècle : « l'infâme communauté des choses de l'âge bestial ». Pierre Manent, qui énonce cette citation dans « Les métamorphoses de la cité », prend soin d'ajouter : « quand tout était commun, rien n'était commun. » Le commun n'est possible que précédé par une activation du propre, du différencié, condition cruciale pour l'émergence, en chacun, des valeurs de l' « humanitas » selon les Anciens, autrement dit de l'humain parvenant à maturité. Il faut l'admettre en conséquence, le commun n'est possible que dans un cadre fini, doté de limites protégeant la naissance et l'essor de ce différencié.

La diversité contre la variété

Cela peut surprendre a priori, mais la marche actuelle vers l'indifférenciation générale est grandement servie par cette idée de diversité que martèlent à l'envi les tenants du « vivre-ensemble ». Pourtant, à l’examen, tout-à-fait cohérente s'avère la démarche des gens de Terra Nova, qui mettent en oeuvre, par leur rhétorique, une technique de fragmentation de la civilisation, un manuel de décomposition. Briser l'unité d'un ensemble vivant en ciblant la complexité de ses liens structurants. Puis, à partir des éléments épars et désormais perçus comme interchangeables, recréer d'autres liens, totalement artificiels. Car, il ne faut s'y tromper, ces déconstructeurs sont des constructivistes. C'est aussi le sens de l'incantation systématique de l' « autre » qui mène, au bout du compte, à la destruction de toute altérité et à la réorganisation implacable de tous sous une norme unique.

Quasiment élevée au rang de dogme, cette idée de diversité constitue la contrefaçon d'une notion apparemment semblable mais qu'un abîme sépare, la « varietas », surgie dans le monde gréco-romain (poïkilia, en grec, déjà présente chez Homère). Utilisée surtout dans le domaine esthétique, parfois dans le domaine politique, cette dernière a constitué chez les Anciens l'une des toiles de fond cognitives sur laquelle a pu s'esquisser la notion de commun, qu'elle contient en germe. Sous le soleil antique, « varietas » et commun se répondent dans une féconde complémentarité. Ainsi, selon cette vision des choses qui doit beaucoup à l'observation du vivant, l'unité émane de la pluralité parce que la pluralité en question ne se conçoit elle-même qu'ordonnée de l'intérieur. Elle n'est pas chaotique mais intimement harmonique. La « varietas » recèle donc un ordre à la fois souple et ferme, riche et ouvert, mais non ouvert à tous les vents, comme c'est le cas avec la « diversité » propre au « vivre-ensemble ». Cet ordre intérieur, se situant à égale distance du chaos et de l'uniformité, échappe donc à ces deux fléaux, qui sont eux aussi complémentaires dans le système que nous subissons. A l'évidence, ce souci d'équilibre harmonique, pourtant au tréfonds de la psyché européenne, a fini par s'affaiblir au fil des siècles au profit de l'esprit de géométrie. La vigueur séculaire de la notion de commun en politique s’en est trouvée atteinte.

De fait, le sentiment du commun dans la population diminue aujourd'hui à vue d'oeil, et comme l'esprit du « vivre-ensemble », censé le remplacer, suscite quelque résistance, le ciment réel de la société française consiste finalement en une situation passive de concorde générale. Par nature instable, ce simple état de non-conflictualité, de plus en plus relatif au demeurant, s'appuie surtout sur les intérêts à court terme des volontés individuelles, aveuglément réglées sur les multiples passions étroites qu'érigent en habitus les stimulations du système marchand. Constat désormais bien établi. Comment remédier alors au déséquilibre inhérent à un tel état de dissociété, avec sa dialectique entre concorde et discorde, la seconde venant sans cesse saper la part encore traditionnelle des bases de la première, c'est-à-dire les divers liens de solidarité fondés sur le temps long, un territoire donné et le consentement à une commune perception du monde ? Dès lors que l'on ne fait pas le choix de changer de paradigme en mettant l'accent sur ces liens sociaux véritables, il n'est d'autre voie que la fuite en avant idéologique.

Solution d'une difficulté croissante pour les gouvernants, tant s'exacerbent sur le terrain le mouvement des atomes en concurrence et celui des groupes en voie de sécession culturelle. Acheter la paix civile par toutes sortes de concessions ne suffit plus. Il faut alors envisager les choses selon la perspective d'une véritable ingénierie sociale (et faire toute leur place aux idées de Terra Nova). De ce point de vue, la mise en oeuvre, sans cesse renouvelée, de la même idéologie, à chaque fois plus précise, constitue un choix moins absurde qu'il n'y paraît. Bien pesée et inscrite dans un projet cohérent de remodelage du corps social, telle se révèle à la longue cette injonction du « vivre-ensemble », lancée à une population qui la reçoit pourtant de moins en moins docilement, comprenant peut-être enfin qu'il s'agit là d'un commandement.

Un commandement ? Au-delà de la surface rhétorique, c'est le rapport entre gouvernants et gouvernés, autrement dit la dialectique politique réellement existante aujourd'hui, qui sous-tend la politique du « vivre-ensemble ». Décidée au sommet pour maintenir artificiellement la concorde et imposée au pays sans énoncer clairement le choix radical dont elle procède, cette politique traduit avec force la dynamique de plus en plus unilatérale de l'Etat moderne. On sait que Tocqueville avait noté la nature « tutélaire » de ce dernier, et avec le temps, force est de constater la permanence de cette empreinte génétique. C’est là un point essentiel, qui fait néanmoins l'objet de malentendus. Il arrive en effet que le caractère unilatéral en question soit assimilé, à tort, avec la souveraineté et avec le principe vertical d'autorité assurant l'exercice des fonctions régaliennes. Sur les soubassements de cet unilatéralisme, quelques précisions s'imposent donc.

Caractère hybride de l'Etat et unilatéralisme

Il n'est évidemment pas question ici de définir ce qu'est l'Etat ni d'en tracer la généalogie, mais de clarifier quelques points élémentaires liés à notre sujet. Ainsi, on ne confondra pas la spécificité de l'Etat moderne avec les caractéristiques de la cité, cette dernière entendue dans notre propos au sens de forme politique traditionnelle (ou « Etat traditionnel ») et non, à la différence de Pierre Manent, au sens de forme politique historique (même si, par ailleurs, cette forme traditionnelle provient essentiellement de la « res publica » romaine). Distinction d'autant plus nécessaire que les deux structures sont étroitement imbriquées depuis des siècles et couramment prises l'une pour l'autre, bien que relevant de logiques différentes. Il faut en prendre acte, l'Etat en France a une nature hybride.

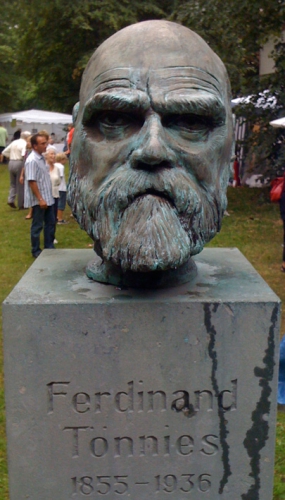

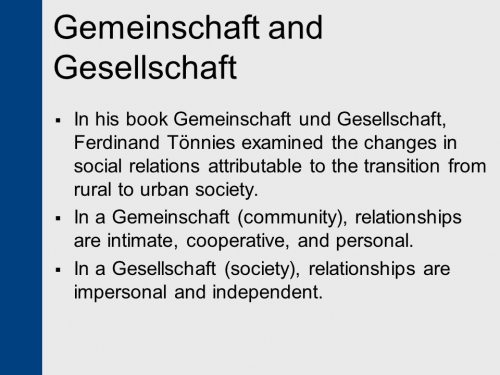

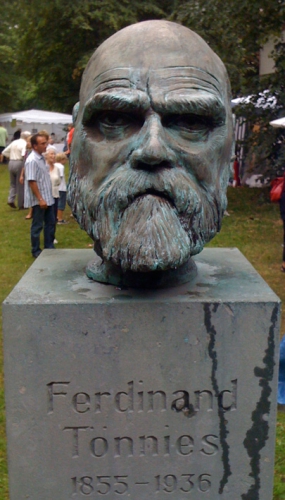

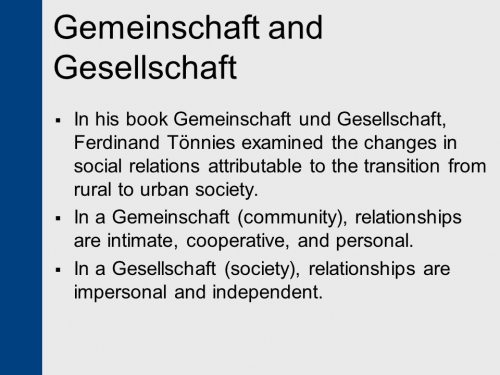

Rappelons simplement que l'Etat moderne en tant que tel, fondé historiquement, entre autres notions juridiques, sur celle de « persona ficta » et adossé au principe de représentation politique, phagocyte le modèle de la cité. Ce dernier repose, quant à lui, sur le souci initial d'une « chose commune » et sur l'exigence de sa maîtrise par une communauté concrète (c'est-à-dire par une « Gemeinschaft » et non par une « Gesellschaft », selon les catégories de Tönnies). La cité naît même de l'exigence d'une telle maîtrise, comme l'indique Cicéron qui, dans une période troublée où le politique semblait privé de boussole, rappelait dans le « De republica » que « la cité est l'institution collective (con-stitutio) de la communauté (populus) ». C'est la communauté qui institue la cité et non l'inverse. Laissons de côté le fait qu'en pratique, la genèse de la cité et celle de la communauté qui en est l'assise sont des processus complexes qui interagissent. L'idée principale réside ici dans cette conscience vive, chez l'illustre sénateur, que la dynamique politique se déploie dans un sens précis, c'est-à-dire à partir des solides liens internes d'une communauté humaine donnée, avec son territoire, ses coutumes et ses représentations mentales collectives (toutes choses auxquelles renvoie la notion de « populus » dans le droit public romain) et que, dans les moments de crise institutionnelle, c'est sur cette base qu'il faut reprendre appui avant de procéder aux réformes nécessaires. Dans la cité, le rapport entre gouvernés et gouvernants est déterminé par la communauté politique qui, de ce fait, maîtrise ses choix. Sans que le régime soit nécessairement démocratique pour autant (de fait, il l'a peu été) et sans que fasse défaut la verticalité du principe d'autorité, bien au contraire.

Rappelons simplement que l'Etat moderne en tant que tel, fondé historiquement, entre autres notions juridiques, sur celle de « persona ficta » et adossé au principe de représentation politique, phagocyte le modèle de la cité. Ce dernier repose, quant à lui, sur le souci initial d'une « chose commune » et sur l'exigence de sa maîtrise par une communauté concrète (c'est-à-dire par une « Gemeinschaft » et non par une « Gesellschaft », selon les catégories de Tönnies). La cité naît même de l'exigence d'une telle maîtrise, comme l'indique Cicéron qui, dans une période troublée où le politique semblait privé de boussole, rappelait dans le « De republica » que « la cité est l'institution collective (con-stitutio) de la communauté (populus) ». C'est la communauté qui institue la cité et non l'inverse. Laissons de côté le fait qu'en pratique, la genèse de la cité et celle de la communauté qui en est l'assise sont des processus complexes qui interagissent. L'idée principale réside ici dans cette conscience vive, chez l'illustre sénateur, que la dynamique politique se déploie dans un sens précis, c'est-à-dire à partir des solides liens internes d'une communauté humaine donnée, avec son territoire, ses coutumes et ses représentations mentales collectives (toutes choses auxquelles renvoie la notion de « populus » dans le droit public romain) et que, dans les moments de crise institutionnelle, c'est sur cette base qu'il faut reprendre appui avant de procéder aux réformes nécessaires. Dans la cité, le rapport entre gouvernés et gouvernants est déterminé par la communauté politique qui, de ce fait, maîtrise ses choix. Sans que le régime soit nécessairement démocratique pour autant (de fait, il l'a peu été) et sans que fasse défaut la verticalité du principe d'autorité, bien au contraire.

En ce qui le concerne, l'Etat moderne utilise, dès ses prémisses médiévales, des institutions héritées de la cité en les englobant dans une structure unilatérale qui les nie peu à peu, tant sa démarche est autre. Volonté d'imposer un ordre de l'extérieur, désir de symétrie forcée, cet unilatéralisme en mouvement se traduit lentement mais sûrement par un principe d'uniformité qui tourne le dos à la « varietas » traditionnelle. On le sait, le déroulement de ce processus historique n’a nullement été paisible. Les populations ont souvent résisté à ce qu'elles percevaient comme une atteinte à la chose commune, garantie alors par les principes coutumiers. D'où les appels incessants à la « reformatio » (littéralement, retour - de ce qui est devenu informe - à une forme). Depuis le XIVe siècle et la réaffirmation aristocratique des libertés normandes face aux audaces inédites de l'administration centrale, suivie des premières grandes révoltes populaires, nombre des secousses politiques de notre histoire ont été des réactions à ce phénomène, vivement ressenti à tous les échelons. Mais ce n'est que parvenu à un stade avancé de son évolution que l'Etat déploie toutes les conséquences de ce caractère unilatéral. Il faut d’ailleurs le noter, ce dernier n'a pas toujours été bien discerné, puisque, même après Hobbes, même après Hegel, observateurs conscients d'une telle évolution, nombreux sont les auteurs qui ont traité pertinemment des propriétés de l'Etat moderne sans avoir pris la mesure d'une telle singularité. Pour établir ce point avec un minimum de justesse, compte tenu de l'interpénétration des deux modèles d'Etat dans la réalité empirique, il est souhaitable d’user d'instruments d'analyse multiples et bien coordonnés. Retenons, à ce titre, l'intérêt du droit public romain, sur lequel nous reviendrons.

En observant la structure politique globale de la nation à l’échelle du temps long, on constate donc que la dynamique unilatérale marque des points et l'emporte peu à peu sur la logique communautaire. Sous ce rapport, les fameux « légistes » médiévaux ont finalement gagné et, dans leur sillage, la Révolution et la centralisation napoléonienne ont constitué des jalons décisifs bien connus. A l'issue de ce long processus, il apparaît alors qu'un Etat moderne est ce que devient un Etat traditionnel qui ne s'appartient plus. De ce phénomène de dépossession, la situation actuelle est hélas riche en symptômes alarmants, parmi lesquels l'impuissance de l'Etat à maîtriser ses frontières et à garantir la sécurité intérieure de façon satisfaisante, autrement dit à assurer les premières de ses missions régaliennes. Le fait que cette impuissance se double par ailleurs d'un contrôle renforcé de la population, accentuant par là le hiatus entre l'institution étatique et la communauté nationale, est un indice significatif de la nature intrinsèque de cette étonnante dépossession des fonctions légitimes de l'Etat par l'Etat : une dépossession de volonté politique. Grave préjudice, s'il en est, dont il faut préciser qu'il s'est produit techniquement au niveau du mode de formation de la volonté commune nationale. Au terme d'un cycle séculaire, la nation s'est vu confisquer la maîtrise réelle des décisions qu'une communauté doit prendre pour persévérer dans son être. En matière de consentement, il ne lui reste plus, dès lors, que l'adhésion aux orientations décidées à l'extérieur de son être propre. Par ailleurs, l'effort constant déployé par le pouvoir et ses relais, pour formater l'esprit public en vue de cette adhésion, confirme l'unilatéralisme en cause. Il faut, d'une manière ou d'une autre, que le peuple consente aux choix d'en-haut et, un jour, rien n'empêchera peut-être que la mise en scène de cette adhésion puisse tenir lieu d'adhésion réelle.

Vice du consentement politique

Cette subversion du consentement qui aboutit aujourd'hui à l'impératif du « vivre-ensemble », sa phase la plus avancée, n'est donc possible, on le voit, que parce que la communauté nationale se trouve préalablement privée de la formation effective de sa volonté propre. Lorsqu'on parle de formation de volonté, on touche un point essentiel dont nous avons en partie perdu le sens. Aussi ne voyons-nous plus clairement que solliciter l'expression d'une volonté qui n'a pas pu se former vraiment, faute des conditions requises, relève d'un vice du consentement. Lequel est cause de nullité en droit privé. Les choses se présentent sous un jour spécifique en droit public, avec le procédé de la représentation. La formation de la volonté commune y est tenue pour acquise par le simple fait de son expression, réduite en l'occurrence à la désignation de représentants dont les décisions ne sont pas soumises à validation. Ce qui suscite depuis longtemps une interrogation devenue classique sur la nature réelle du débat démocratique. Devant la crise actuelle du concept de représentation, sans solution pour l'heure (la notion vague de démocratie participative étant plus un révélateur de cette crise qu'un début de solution), une partie de la doctrine parle d'un « blocage théorique ». Dans ce contexte, il est utile de prêter attention à la critique radicale de certains universitaires italiens spécialistes de droit romain, qui se livrent à une rigoureuse analyse des mécanismes en question.

Les concepts du droit romain, produits d'une longue maturation qui a fait d'eux des outils « inactuels », au sens nietzschéen, s'avèrent en effet précieux. Ils permettent notamment de faire surgir l'alternative existant entre les grands types de processus décisionnels relatifs aux communautés, publiques ou privées, au-delà des modalités variant selon époques et contextes. Giovanni Lobrano oppose ainsi aux organisations humaines modernes régies par le principe de personnalité juridique (la « persona ficta » théorisée et mise en oeuvre à partir du XIIIe siècle, d'où est sortie la « persona artificialis » du Léviathan de Hobbes au XVIIe siècle) celles qui sont régies par le principe sociétaire, fondé quant à lui sur le très classique et très romain contrat de société (que l'on ne confondra évidemment pas avec l'idée moderne de contrat social). Il fait observer que le modèle sociétaire a le mérite d'être construit sur la nécessité d'une « communio » entre les membres de la « societas » concernée, c'est-à-dire sur des liens internes forts, conçus par analogie aux liens intrafamiliaux (mais sur un mode libre et volontaire permettant de constituer des consortiums gérant des biens, des organisations professionnelles, des sociétés commerciales). Ce modèle, étranger au contractualisme, s'enracine dans une réalité anthropologique, toute « relatio » tirant sa validité du « mos majorum » (les mœurs, l’éthique commune des ancêtres) et n’étant ainsi pas réduite au pur intérêt calculé des modernes. A l’opposé d’un tel enracinement surgit le principe de personne juridique, création artificielle de la loi.

De cette différence cruciale, il résulte que, d'un modèle à l'autre, le rapport fondamental entre l'un et le multiple est quasiment inversé. Dans la communauté régie par le principe sociétaire, ce sont les liens internes, faits d'obligations réciproques, qui sont le ferment de l'unité rassemblant cette pluralité d'hommes et qui déterminent la formation de la volonté commune. Aussi les dirigeants issus de l'expression de cette volonté restent-ils subordonnés à cette dernière dans l'exercice de leur charge, tout en disposant de larges pouvoirs d'initiative et d'exécution. Quels que puissent être leur pouvoir et le prestige de leur titre, ils restent des délégués. L’administrateur d’une société privée, mais aussi le consul, l’empereur, le roi de France (bien que pris entre deux logiques) se considèrent comme des dépositaires. Au contraire, dans la communauté régie par le principe de personnalité juridique (ou fictive), l'unité de la pluralité d'hommes qui la constituent est assurée de l'extérieur. C'est la fonction de la « persona » comme structure englobante, avec ce qu'elle recèle d'irrémédiablement arbitraire et de malléable et qui, à son tour, détermine les conditions de formation de la volonté commune. Celle-ci peut alors se voir absorbée par le mécanisme de la représentation, issu d'une distorsion de la notion romaine de mandat, en l'occurrence d'une distorsion du lien entre mandant et mandataire. A cet égard, Lobrano montre, au moyen d'une analyse acérée, que représentation et personnalité fictive procèdent de la même matrice conceptuelle : ces principes ont été élaborés pour fonctionner ensemble. On constate que les dirigeants qui émanent de ce dispositif, véritable saut quantique par rapport à la conception ancienne en matière de gestion de toute affaire commune, bénéficient d'une autonomie inouïe, puisqu'en pratique, la volonté du représentant se substitue à celle du représenté (la communauté).

Dans ce domaine, ce qui vaut en droit privé vaut aussi en droit public. Le passage du régime sociétaire au régime de la personnalité juridique-représentation bouleverse structure interne et mode de gestion, autant pour la communauté nationale que pour une simple entreprise. La nation a connu cette évolution complexe, prise dans la dynamique un Etat moderne (la « persona artificialis » et ses représentants) qui n'a désormais de cesse de liquider ce qui reste de l'ancestrale politique du bien commun : elle s'en trouve profondément affectée dans sa substance. En définitive, on doit tenir pour essentiel le phénomène suivant : les modes de formation de la volonté commune rétroagissent sur la nature des liens internes de la communauté. La réciproque est vraie, comme l'atteste le triste spectacle offert par la nation : son état de dissolution interne la rend toujours plus vulnérable et passive face aux politiques imposées, notamment celles qui travaillent au remodelage de la population et accentuent ainsi cette dissolution. Telle est la spirale infernale du « vivre-ensemble ». A ce titre, on s’aperçoit que ce processus aboutit finalement à l’inversion de l’ordonnancement que décrivait Cicéron. Ce n’est plus le peuple (la communauté politique) qui institue la cité, c’est l’Etat qui veut instituer le peuple, le recréer de toutes pièces.

Pour tenter de sortir de cette spirale, accordons quelque attention aux mécanismes de dépossession en jeu. L'édifice national menace ruine. Il est temps de s'occuper des murs porteurs et de la manière dont ils sont agencés. Plaider pour une politique du bien commun et pour une souveraineté digne de ce nom, sans se soucier de leurs conditions profondes, c'est en rester au stade des voeux. Une voie plus conséquente consisterait à puiser des forces dans une volonté commune réellement formée, non subvertie, pour renforcer, dans le même mouvement, les liens de la communauté nationale et les prérogatives régaliennes. Il ne s'agit pas de miser sur les prétendues vertus de la démocratie directe mais de libérer le consentement par la mise en œuvre réelle du principe de subsidiarité. Un tel changement est envisageable à faible coût, l’objectif étant de « désétatiser le bien commun » pour mieux assurer ce bien commun. A la fois souple et ferme comme un muscle puissant, l' « Etat subsidiaire », pour employer l'expression de Chantal Delsol, est de nature à offrir un cadre approprié au modèle sociétaire et à la décision vigoureuse qu’il permet. Il apparaît bien ainsi comme la condition d'un « hard power » qui serait enfin à la hauteur des enjeux présents. Il n'y a pas de remède miracle, seulement des données cruciales à prendre en compte si l'on pense qu'un redressement est possible. Le cadre et la structure de la volonté commune, conditionnant la qualité de la décision, comptent au nombre de ces données. Aussi, convient-il d’en être conscient pour pouvoir opposer un jour, avec succès, aux tenants du « vivre-ensemble » les exigences toujours vives de l'être-ensemble, ce rapport existentiel d'une population avec son passé et son territoire.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Klages does not think highly of most psychology. It is based on misunderstandings, it has limited possibilities to describe personalities, and it is not a science of the soul. This means that modern psychology and older wisdom about the soul are strangers to each other. Klages does connect to such wisdom. Among other things, he is interested in the psychological insights of folk-language. People are “seeing red”, they get “high” or “carried away”, and become “blue”. Klages is interesting to read when he studies this area.

Klages does not think highly of most psychology. It is based on misunderstandings, it has limited possibilities to describe personalities, and it is not a science of the soul. This means that modern psychology and older wisdom about the soul are strangers to each other. Klages does connect to such wisdom. Among other things, he is interested in the psychological insights of folk-language. People are “seeing red”, they get “high” or “carried away”, and become “blue”. Klages is interesting to read when he studies this area.

Rappelons simplement que l'Etat moderne en tant que tel, fondé historiquement, entre autres notions juridiques, sur celle de « persona ficta » et adossé au principe de représentation politique, phagocyte le modèle de la cité. Ce dernier repose, quant à lui, sur le souci initial d'une « chose commune » et sur l'exigence de sa maîtrise par une communauté concrète (c'est-à-dire par une « Gemeinschaft » et non par une « Gesellschaft », selon les catégories de Tönnies). La cité naît même de l'exigence d'une telle maîtrise, comme l'indique Cicéron qui, dans une période troublée où le politique semblait privé de boussole, rappelait dans le « De republica » que « la cité est l'institution collective (con-stitutio) de la communauté (populus) ». C'est la communauté qui institue la cité et non l'inverse. Laissons de côté le fait qu'en pratique, la genèse de la cité et celle de la communauté qui en est l'assise sont des processus complexes qui interagissent. L'idée principale réside ici dans cette conscience vive, chez l'illustre sénateur, que la dynamique politique se déploie dans un sens précis, c'est-à-dire à partir des solides liens internes d'une communauté humaine donnée, avec son territoire, ses coutumes et ses représentations mentales collectives (toutes choses auxquelles renvoie la notion de « populus » dans le droit public romain) et que, dans les moments de crise institutionnelle, c'est sur cette base qu'il faut reprendre appui avant de procéder aux réformes nécessaires. Dans la cité, le rapport entre gouvernés et gouvernants est déterminé par la communauté politique qui, de ce fait, maîtrise ses choix. Sans que le régime soit nécessairement démocratique pour autant (de fait, il l'a peu été) et sans que fasse défaut la verticalité du principe d'autorité, bien au contraire.

Rappelons simplement que l'Etat moderne en tant que tel, fondé historiquement, entre autres notions juridiques, sur celle de « persona ficta » et adossé au principe de représentation politique, phagocyte le modèle de la cité. Ce dernier repose, quant à lui, sur le souci initial d'une « chose commune » et sur l'exigence de sa maîtrise par une communauté concrète (c'est-à-dire par une « Gemeinschaft » et non par une « Gesellschaft », selon les catégories de Tönnies). La cité naît même de l'exigence d'une telle maîtrise, comme l'indique Cicéron qui, dans une période troublée où le politique semblait privé de boussole, rappelait dans le « De republica » que « la cité est l'institution collective (con-stitutio) de la communauté (populus) ». C'est la communauté qui institue la cité et non l'inverse. Laissons de côté le fait qu'en pratique, la genèse de la cité et celle de la communauté qui en est l'assise sont des processus complexes qui interagissent. L'idée principale réside ici dans cette conscience vive, chez l'illustre sénateur, que la dynamique politique se déploie dans un sens précis, c'est-à-dire à partir des solides liens internes d'une communauté humaine donnée, avec son territoire, ses coutumes et ses représentations mentales collectives (toutes choses auxquelles renvoie la notion de « populus » dans le droit public romain) et que, dans les moments de crise institutionnelle, c'est sur cette base qu'il faut reprendre appui avant de procéder aux réformes nécessaires. Dans la cité, le rapport entre gouvernés et gouvernants est déterminé par la communauté politique qui, de ce fait, maîtrise ses choix. Sans que le régime soit nécessairement démocratique pour autant (de fait, il l'a peu été) et sans que fasse défaut la verticalité du principe d'autorité, bien au contraire.

On trouve trace du « projet » chez un Rousseau qui dans son Contrat social expliquait que le « grand législateur » est celui qui ose « instituer un peuple » (C.S. II,7). Instituer, c’est-à-dire « fonder » et « créer ». Ce grand législateur doit être le « mécanicien qui invente la machine » en changeant la « nature humaine », « transformant chaque individu », lui rognant son « indépendance » et ses « forces propres » pour en faire une simple « partie d’un grand tout » (C.S. II,7). Tout y est déjà !

On trouve trace du « projet » chez un Rousseau qui dans son Contrat social expliquait que le « grand législateur » est celui qui ose « instituer un peuple » (C.S. II,7). Instituer, c’est-à-dire « fonder » et « créer ». Ce grand législateur doit être le « mécanicien qui invente la machine » en changeant la « nature humaine », « transformant chaque individu », lui rognant son « indépendance » et ses « forces propres » pour en faire une simple « partie d’un grand tout » (C.S. II,7). Tout y est déjà !

Le comte nommé Allamistakéo, la momie donc, donne sa vision du progrès :

Le comte nommé Allamistakéo, la momie donc, donne sa vision du progrès :

Furthermore, in the decades following World War 2, we have seen student political movements whose precise goal was radical individualism, masquerading as communism or socialism. Thus you find statements like that of 60s radical John Sinclair who demanded, “Total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the streets.” The roots of this style of thinking lie in the Situationist movement, which influenced the Punk subculture (Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren was notably influenced by the movement). Situationism emerged from the anti-authoritarian left in France to advocate attacking capitalism through the construction of “situations,” to quote Debord, “Our central idea is the construction of situations, that is to say, the concrete construction of momentary ambiences of life and their transformation into a superior passional quality.”2 These situations took the form of radical individual liberation and experimentation, avant-garde artistic movements, and the celebration of free play and leisure. While Situationism situated itself on the communist left, it replicated the individualism of capitalism, as Kazys Varnelis notes3:

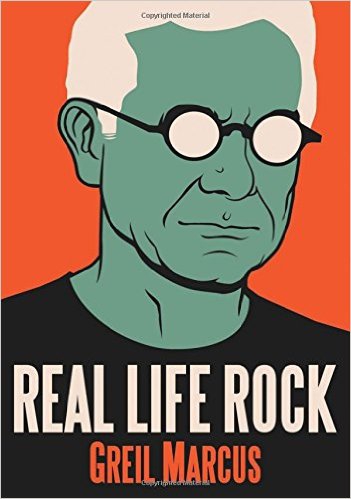

Furthermore, in the decades following World War 2, we have seen student political movements whose precise goal was radical individualism, masquerading as communism or socialism. Thus you find statements like that of 60s radical John Sinclair who demanded, “Total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the streets.” The roots of this style of thinking lie in the Situationist movement, which influenced the Punk subculture (Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren was notably influenced by the movement). Situationism emerged from the anti-authoritarian left in France to advocate attacking capitalism through the construction of “situations,” to quote Debord, “Our central idea is the construction of situations, that is to say, the concrete construction of momentary ambiences of life and their transformation into a superior passional quality.”2 These situations took the form of radical individual liberation and experimentation, avant-garde artistic movements, and the celebration of free play and leisure. While Situationism situated itself on the communist left, it replicated the individualism of capitalism, as Kazys Varnelis notes3: Deliberately obscure, Situationism was cool, and thus the perfect ideology for the knowledge-work generation. What could be better to provoke conversation at the local Starbucks or the company cantina, especially once Marcus’s, which traced a dubious red thread between Debord and Malcolm McLaren, hit the presses? Rock and roll plus neoliberal politics masquerading as leftism: a perfect mix. For the generation that came of age with Situationism-via-Marcus and the

Deliberately obscure, Situationism was cool, and thus the perfect ideology for the knowledge-work generation. What could be better to provoke conversation at the local Starbucks or the company cantina, especially once Marcus’s, which traced a dubious red thread between Debord and Malcolm McLaren, hit the presses? Rock and roll plus neoliberal politics masquerading as leftism: a perfect mix. For the generation that came of age with Situationism-via-Marcus and the  But there was also another Mai 68, of strictly hedonist and individualist inspiration. Far from exalting a revolutionary discipline, its partisans wanted above all “forbidding to forbid” and “unhindered enjoyment.” But, they quickly realized that doesn’t make a revolution nor will “satisfying these desires” put them in the service of the people. On the contrary, they rapidly understood that those would be most surely satisfied by a permissive liberal society. Thus they all naturally rallied to liberal capitalism, which was not, for most of them, without material and financial advantages.

But there was also another Mai 68, of strictly hedonist and individualist inspiration. Far from exalting a revolutionary discipline, its partisans wanted above all “forbidding to forbid” and “unhindered enjoyment.” But, they quickly realized that doesn’t make a revolution nor will “satisfying these desires” put them in the service of the people. On the contrary, they rapidly understood that those would be most surely satisfied by a permissive liberal society. Thus they all naturally rallied to liberal capitalism, which was not, for most of them, without material and financial advantages.

Recensé : Hamit Bozarslan et Gaëlle Demelemestre,

Recensé : Hamit Bozarslan et Gaëlle Demelemestre,

Désormais, une manif ne se disperse plus mais se disloque. Le verbe générer a remplacé susciter, tandis qu’impacter (avoir un impact sur) s’est imposé. On parle de déroulé (et non de déroulement) ou de ressenti (sentiment). Or, regrette-t-elle, cet appauvrissement du vocabulaire conduit parfois à des erreurs. Ainsi des violences qui se font désormais «en marge» des manifestations, alors qu’elles les accompagnent. «En marge» également, les agressions sexuelles de la place Tahrir en Égypte? Pourtant, les violeurs étaient aussi des manifestants.

Désormais, une manif ne se disperse plus mais se disloque. Le verbe générer a remplacé susciter, tandis qu’impacter (avoir un impact sur) s’est imposé. On parle de déroulé (et non de déroulement) ou de ressenti (sentiment). Or, regrette-t-elle, cet appauvrissement du vocabulaire conduit parfois à des erreurs. Ainsi des violences qui se font désormais «en marge» des manifestations, alors qu’elles les accompagnent. «En marge» également, les agressions sexuelles de la place Tahrir en Égypte? Pourtant, les violeurs étaient aussi des manifestants. Deux ans après, un assassinat similaire survient (le meurtre du jeune Kilian, en juin 2012). Le Monde choisit de désigner le suspect comme un… Vladimir avant de préciser que «le prénom a été changé». S’ensuit un courrier des lecteurs auquel répond le médiateur: il s’agissait de respecter l’anonymat du suspect «conformément à la loi» – argument fallacieux tant cette précaution est rarement respectée par ailleurs.

Deux ans après, un assassinat similaire survient (le meurtre du jeune Kilian, en juin 2012). Le Monde choisit de désigner le suspect comme un… Vladimir avant de préciser que «le prénom a été changé». S’ensuit un courrier des lecteurs auquel répond le médiateur: il s’agissait de respecter l’anonymat du suspect «conformément à la loi» – argument fallacieux tant cette précaution est rarement respectée par ailleurs.

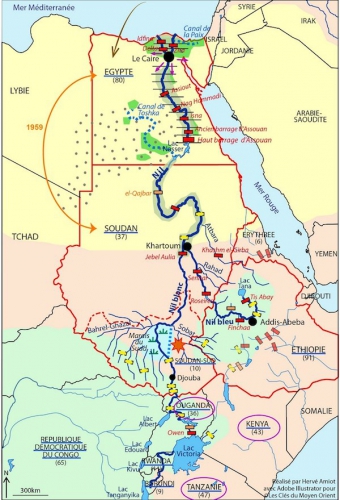

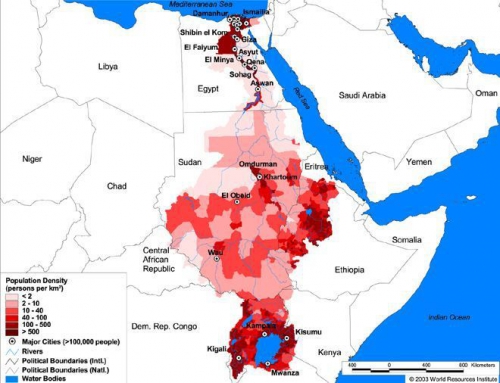

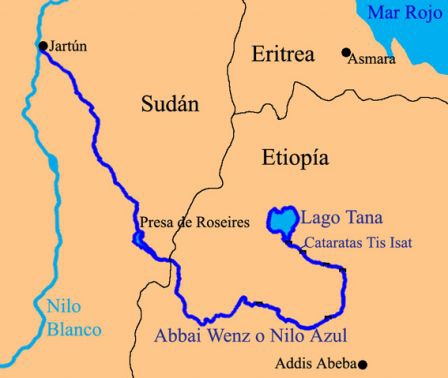

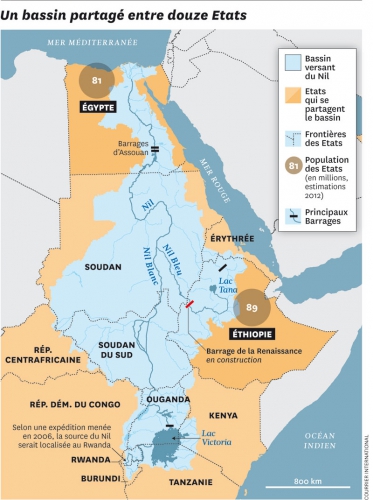

Con todo ello, Etiopía pasaría de ser un país donde tan sólo un tercio de la población tiene acceso a energía eléctrica a ser el mayor exportador de energía de África oriental. Al mismo tiempo, los problemas derivados de la sequía se verían enormemente reducidos y se experimentaría un notable estímulo del desarrollo económico. O desde luego así lo creen las autoridades etíopes, que consideran que un fracaso en la construcción de la presa constituiría un fracaso de Etiopía en su totalidad. Tal es la importancia de la GERD para ellos que han financiado las obras con recursos públicos propios.

Con todo ello, Etiopía pasaría de ser un país donde tan sólo un tercio de la población tiene acceso a energía eléctrica a ser el mayor exportador de energía de África oriental. Al mismo tiempo, los problemas derivados de la sequía se verían enormemente reducidos y se experimentaría un notable estímulo del desarrollo económico. O desde luego así lo creen las autoridades etíopes, que consideran que un fracaso en la construcción de la presa constituiría un fracaso de Etiopía en su totalidad. Tal es la importancia de la GERD para ellos que han financiado las obras con recursos públicos propios. Así, la NBI ha logrado que el eje gravitacional de la región se haya desplazado al sur. Con ello Egipto, a pesar de sus esfuerzos de mantener el statu quo con su participación de la iniciativa, tendrá que cambiar su estrategia, y aceptar la necesidad de tejer alianzas con las naciones meridionales de la cuenca; será ésta la única vía por la que podrá capear su inminente crisis hídrica sin provocar una escalada de tensiones armadas en la región, a la vez que se beneficia del desarrollo económico de la zona.

Así, la NBI ha logrado que el eje gravitacional de la región se haya desplazado al sur. Con ello Egipto, a pesar de sus esfuerzos de mantener el statu quo con su participación de la iniciativa, tendrá que cambiar su estrategia, y aceptar la necesidad de tejer alianzas con las naciones meridionales de la cuenca; será ésta la única vía por la que podrá capear su inminente crisis hídrica sin provocar una escalada de tensiones armadas en la región, a la vez que se beneficia del desarrollo económico de la zona.

Parmi les philosophies antiques, le stoïcisme tient une grande place. Traversant l'antiquité grecque et l'antiquité romaine sur près de six siècles, symbole du sérieux et de l'abnégation de tout un peuple, l'école du Portique apprend à ses disciples à vivre en harmonie avec l'univers et ses lois. Maîtrise de soi, courage, tenue, éthique, ce sont là quelques mots clés pour comprendre le stoïcisme. Le Manuel 1 d'Epictète, condensé de cette sagesse, permet à chaque Européen de renouer avec les plus rigoureuses racines de notre civilisation. Brillant exemple de ce que pouvait produire l'univers mental propre au paganisme européen, le stoïcisme continuera d'irriguer la pensée européenne sur la longue durée (avec notamment le mouvement du néo-stoïcisme de la Renaissance). Et au delà de la longue durée, il est important de souligner l'actualité de la philosophie stoïcienne. Philosophie de temps de crise comme le souligne son histoire, le stoïcisme redirige l'homme vers l'action.

Parmi les philosophies antiques, le stoïcisme tient une grande place. Traversant l'antiquité grecque et l'antiquité romaine sur près de six siècles, symbole du sérieux et de l'abnégation de tout un peuple, l'école du Portique apprend à ses disciples à vivre en harmonie avec l'univers et ses lois. Maîtrise de soi, courage, tenue, éthique, ce sont là quelques mots clés pour comprendre le stoïcisme. Le Manuel 1 d'Epictète, condensé de cette sagesse, permet à chaque Européen de renouer avec les plus rigoureuses racines de notre civilisation. Brillant exemple de ce que pouvait produire l'univers mental propre au paganisme européen, le stoïcisme continuera d'irriguer la pensée européenne sur la longue durée (avec notamment le mouvement du néo-stoïcisme de la Renaissance). Et au delà de la longue durée, il est important de souligner l'actualité de la philosophie stoïcienne. Philosophie de temps de crise comme le souligne son histoire, le stoïcisme redirige l'homme vers l'action. La pensée stoïcienne dégage à ses origines trois grands axes d'étude: la physique (l'étude du monde environnant), la logique et l'éthique (qui concerne l'action). La pensée d'Epictète a ceci de particulier qu'elle ne s'intéresse pas à l'étude de la physique et ne s'attarde que peu sur celle de la logique, même si Epictète rappelle la prééminence de cette dernière dans l'un de ses aphorismes: Le Manuel, LII, 1-2. Car en effet, toute éthique doit être démontrable.

La pensée stoïcienne dégage à ses origines trois grands axes d'étude: la physique (l'étude du monde environnant), la logique et l'éthique (qui concerne l'action). La pensée d'Epictète a ceci de particulier qu'elle ne s'intéresse pas à l'étude de la physique et ne s'attarde que peu sur celle de la logique, même si Epictète rappelle la prééminence de cette dernière dans l'un de ses aphorismes: Le Manuel, LII, 1-2. Car en effet, toute éthique doit être démontrable.

Et c'est cet Honneur au-dessus de tout, au-dessus de la vie elle-même qui est invoqué par la pensée d'Epictète. Car rappelons-le, la tenue est la base de la pensée stoïcienne. Sans Honneur, point de tenue. Sans tenue, point de voie d'accès à la Sagesse. Et sans Sagesse, on ne saurait faire le Bien. Il faut d'abord et avant tout vivre dans l'honneur et savoir quitter la scène le jour où notre honneur nous le commandera. C'est ce que ce grand Européen que fut Friedrich Nietzsche rappelle dans Le Crépuscule des Idoles 4 (Erreur de la confusion entre la cause et l'effet, 36): Il faut « Mourir fièrement lorsqu'il n'est plus possible de vivre fièrement ». Et s'exercer à contempler la mort jusqu'à ne plus la craindre, jusqu'à lui être supérieur est une des principales méditations stoïciennes : Le Manuel, XXI: « Que la mort, l'exil et tout ce qui paraît effrayant soient sous tes yeux chaque jour ; mais plus que tout, la mort. Jamais plus tu ne diras rien de vil, et tu ne désireras rien outre mesure ». Celui qui se délivrera de l'emprise de la mort sur son existence pourra alors vivre dans l'Honneur jusqu'à sa dernière heure.

Et c'est cet Honneur au-dessus de tout, au-dessus de la vie elle-même qui est invoqué par la pensée d'Epictète. Car rappelons-le, la tenue est la base de la pensée stoïcienne. Sans Honneur, point de tenue. Sans tenue, point de voie d'accès à la Sagesse. Et sans Sagesse, on ne saurait faire le Bien. Il faut d'abord et avant tout vivre dans l'honneur et savoir quitter la scène le jour où notre honneur nous le commandera. C'est ce que ce grand Européen que fut Friedrich Nietzsche rappelle dans Le Crépuscule des Idoles 4 (Erreur de la confusion entre la cause et l'effet, 36): Il faut « Mourir fièrement lorsqu'il n'est plus possible de vivre fièrement ». Et s'exercer à contempler la mort jusqu'à ne plus la craindre, jusqu'à lui être supérieur est une des principales méditations stoïciennes : Le Manuel, XXI: « Que la mort, l'exil et tout ce qui paraît effrayant soient sous tes yeux chaque jour ; mais plus que tout, la mort. Jamais plus tu ne diras rien de vil, et tu ne désireras rien outre mesure ». Celui qui se délivrera de l'emprise de la mort sur son existence pourra alors vivre dans l'Honneur jusqu'à sa dernière heure. Nous devons donc ne nous préoccuper que de ce qui ne dépend que de nous car selon Epictète, l'une des plus grandes dichotomies à réaliser c'est celle existante entre les choses qui dépendent de nous et celles qui n'en dépendent pas. Parmi les choses qui dépendent de nous, le jugement que l'on se fait de soi et de l'univers qui nous entoure. Ce qui dépend de nous, c'est tout ce qui a trait à notre âme et à notre libre-arbitre. Et parmi les choses qui ne dépendent pas de nous : la mort, la maladie, la gloire, les honneurs et les richesses, les coups du sort tout comme les actions et pensées de nos contemporains. L'homme sage ne s'attachera donc qu'à ce qui dépend de lui et ne souciera point de ce qui n'en dépend point. C'est là la seule manière d'être libéré de toute forme de servilité. Car l'on peut courir après richesses et gloires mais elles sont par définition éphémères. Elles ne trouvent pas leur origine dans notre être profond et lorsque la mort viendra nous trouver, à quoi nous serviront-elles ? Pour être libre, il convient donc de d'abord s'attacher à découvrir ce qui dépend de nous et ce qui n'en dépend pas. C'est bel et bien la première discipline du stoïcisme : celle du discernement. En se plongeant dans Le Manuel d'Epictète, on apprendra vite qu'il faut d'abord et avant tout s'attacher à ce que l'on peut et au rôle dont le destin nous a gratifié. Le rôle qui nous est donné l'a été par l'univers (que ce soit par l'entremise des Dieux ou par la voie des causes et des conséquences) et c'est donc avec ferveur que nous devons le remplir. C'est en faisant ainsi, cheminant aux côtés de ses semblables, modeste et loyal, que l'on sera le plus utile aux siens et à sa patrie. C'est bel et bien une vision fataliste de l'existence, un amor fati très européen. Rappelons-nous qu'aller à l'encontre du destin, c'est défier les Dieux et l'univers. Et pourtant... cela nous est bel et bien permis à nous Européens. La Sagesse consiste à savoir que cela ne peut se faire que lorsque tel acte est commandé par l'absolue nécessité et en étant prêt à en payer le prix. On se replongera dans l'Iliade pour se le remémorer. Mais comme il est donné à bien peu d'entre nous de connaître ce que le destin leur réserve, notre existence reste toujours ouverte. Il n'y a pas de fatalité, seulement un appel à ne jamais se dérober lorsque l'histoire nous appelle. Voici une autre raison de s'exercer chaque jour à contempler la mort. Car si nous ne nous livrons pas quotidiennement à cette méditation, comment réagirons-nous le jour où il nous faudra prendre de véritables risques, voir mettre notre peau au bout de nos idées ? Lorsque le Destin frappera à notre porte, qu'il n'y aura d'autre choix possible qu'entre l'affrontement et la soumission, le stoïcien n'hésitera pas. Que seul le premier choix nous soit accessible, voici le présent que nous fait le stoïcisme. Le Manuel, XXXII, 3: « Ainsi donc, lorsqu'il faut s'exposer au danger pour un ami ou pour sa patrie, ne va pas demander au devin s'il faut s'exposer au danger. Car si le devin te déclare que les augures sont mauvais, il est évident qu'il t'annonce, ou la mort, ou la mutilation de quelque membre du corps, ou l'exil. Mais la raison prescrit, même avec de telles perspectives, de secourir un ami et de s'exposer au danger pour sa patrie. Prends garde donc au plus grand des devins, à Apollon Pythien, qui chassa de son temple celui qui n'avait point porté secours à l'ami que l'on assassinait ».

Nous devons donc ne nous préoccuper que de ce qui ne dépend que de nous car selon Epictète, l'une des plus grandes dichotomies à réaliser c'est celle existante entre les choses qui dépendent de nous et celles qui n'en dépendent pas. Parmi les choses qui dépendent de nous, le jugement que l'on se fait de soi et de l'univers qui nous entoure. Ce qui dépend de nous, c'est tout ce qui a trait à notre âme et à notre libre-arbitre. Et parmi les choses qui ne dépendent pas de nous : la mort, la maladie, la gloire, les honneurs et les richesses, les coups du sort tout comme les actions et pensées de nos contemporains. L'homme sage ne s'attachera donc qu'à ce qui dépend de lui et ne souciera point de ce qui n'en dépend point. C'est là la seule manière d'être libéré de toute forme de servilité. Car l'on peut courir après richesses et gloires mais elles sont par définition éphémères. Elles ne trouvent pas leur origine dans notre être profond et lorsque la mort viendra nous trouver, à quoi nous serviront-elles ? Pour être libre, il convient donc de d'abord s'attacher à découvrir ce qui dépend de nous et ce qui n'en dépend pas. C'est bel et bien la première discipline du stoïcisme : celle du discernement. En se plongeant dans Le Manuel d'Epictète, on apprendra vite qu'il faut d'abord et avant tout s'attacher à ce que l'on peut et au rôle dont le destin nous a gratifié. Le rôle qui nous est donné l'a été par l'univers (que ce soit par l'entremise des Dieux ou par la voie des causes et des conséquences) et c'est donc avec ferveur que nous devons le remplir. C'est en faisant ainsi, cheminant aux côtés de ses semblables, modeste et loyal, que l'on sera le plus utile aux siens et à sa patrie. C'est bel et bien une vision fataliste de l'existence, un amor fati très européen. Rappelons-nous qu'aller à l'encontre du destin, c'est défier les Dieux et l'univers. Et pourtant... cela nous est bel et bien permis à nous Européens. La Sagesse consiste à savoir que cela ne peut se faire que lorsque tel acte est commandé par l'absolue nécessité et en étant prêt à en payer le prix. On se replongera dans l'Iliade pour se le remémorer. Mais comme il est donné à bien peu d'entre nous de connaître ce que le destin leur réserve, notre existence reste toujours ouverte. Il n'y a pas de fatalité, seulement un appel à ne jamais se dérober lorsque l'histoire nous appelle. Voici une autre raison de s'exercer chaque jour à contempler la mort. Car si nous ne nous livrons pas quotidiennement à cette méditation, comment réagirons-nous le jour où il nous faudra prendre de véritables risques, voir mettre notre peau au bout de nos idées ? Lorsque le Destin frappera à notre porte, qu'il n'y aura d'autre choix possible qu'entre l'affrontement et la soumission, le stoïcien n'hésitera pas. Que seul le premier choix nous soit accessible, voici le présent que nous fait le stoïcisme. Le Manuel, XXXII, 3: « Ainsi donc, lorsqu'il faut s'exposer au danger pour un ami ou pour sa patrie, ne va pas demander au devin s'il faut s'exposer au danger. Car si le devin te déclare que les augures sont mauvais, il est évident qu'il t'annonce, ou la mort, ou la mutilation de quelque membre du corps, ou l'exil. Mais la raison prescrit, même avec de telles perspectives, de secourir un ami et de s'exposer au danger pour sa patrie. Prends garde donc au plus grand des devins, à Apollon Pythien, qui chassa de son temple celui qui n'avait point porté secours à l'ami que l'on assassinait ». Il convient de s'attarder maintenant sur ces définitions de l'être et de l'action. Comme nous le voyons, non seulement nous devons aller dans la bonne direction mais qui plus est nous interdire tout ce qui pourrait nous en détourner. Vivre en stoïque, c'est vivre de manière radicale. Que l'on vive le stoïcisme en philosophe ou en citoyen ne change rien à cela. Il n'y a pas de place pour la demi-mesure. Une droite parfaitement rectiligne, c'est ce qui doit symboliser le chemin parcouru par l'homme antique, l'homme stoïque. Il a été dit plus haut que tout était éphémère, que tout n'était que changement. A partir de cette constatation, sachant que nous ne devons point désirer et accorder d'importance à ce qui ne dépend point de nous, il devient dès lors impossible de s'attacher à ses possessions, à ses amis, à sa famille. Ceux-ci ne nous appartiennent pas et rien de ces choses et de ces personnes ne sont une extension de nous-même. Hommes ou objets, nous n'en jouissons que temporairement. Et cela ne doit pas être vu comme un appel à l'indifférence et à l'égoïsme. L'enseignement qui doit en être retiré est que la vérité et l'exigence de tenue ne doivent pas tenir compte de ces que nos contemporains, si proches soient-ils de nous, peuvent en penser. De même, l'argent et les biens matériels ne sont que des outils. Des outils au service du bien, de la cité, de la patrie. Celui qui se laisse posséder par ce qui est extérieur à lui-même ne mérite pas le titre de stoïcien, le qualificatif de stoïque. Et à ceux qui verront le stoïcisme comme trop dur, Epictète répond que la Sagesse a un prix. Nous ne pouvons désirer la paix de l'âme et les fruits d'une vie de servitude. A vrai dire, à vouloir les deux à la fois, on n'obtient bien souvent ni l'un ni l'autre. Et à ceux qui se décourageront en chemin, Epictète rappelle que nous pouvons trouver en nous tous les outils pour persévérer. Face à l'abattement, invoquons la ferveur, face à la fatigue, invoquons l'endurance, face aux insultes et aux coups, invoquons le courage.

Il convient de s'attarder maintenant sur ces définitions de l'être et de l'action. Comme nous le voyons, non seulement nous devons aller dans la bonne direction mais qui plus est nous interdire tout ce qui pourrait nous en détourner. Vivre en stoïque, c'est vivre de manière radicale. Que l'on vive le stoïcisme en philosophe ou en citoyen ne change rien à cela. Il n'y a pas de place pour la demi-mesure. Une droite parfaitement rectiligne, c'est ce qui doit symboliser le chemin parcouru par l'homme antique, l'homme stoïque. Il a été dit plus haut que tout était éphémère, que tout n'était que changement. A partir de cette constatation, sachant que nous ne devons point désirer et accorder d'importance à ce qui ne dépend point de nous, il devient dès lors impossible de s'attacher à ses possessions, à ses amis, à sa famille. Ceux-ci ne nous appartiennent pas et rien de ces choses et de ces personnes ne sont une extension de nous-même. Hommes ou objets, nous n'en jouissons que temporairement. Et cela ne doit pas être vu comme un appel à l'indifférence et à l'égoïsme. L'enseignement qui doit en être retiré est que la vérité et l'exigence de tenue ne doivent pas tenir compte de ces que nos contemporains, si proches soient-ils de nous, peuvent en penser. De même, l'argent et les biens matériels ne sont que des outils. Des outils au service du bien, de la cité, de la patrie. Celui qui se laisse posséder par ce qui est extérieur à lui-même ne mérite pas le titre de stoïcien, le qualificatif de stoïque. Et à ceux qui verront le stoïcisme comme trop dur, Epictète répond que la Sagesse a un prix. Nous ne pouvons désirer la paix de l'âme et les fruits d'une vie de servitude. A vrai dire, à vouloir les deux à la fois, on n'obtient bien souvent ni l'un ni l'autre. Et à ceux qui se décourageront en chemin, Epictète rappelle que nous pouvons trouver en nous tous les outils pour persévérer. Face à l'abattement, invoquons la ferveur, face à la fatigue, invoquons l'endurance, face aux insultes et aux coups, invoquons le courage.  Aller au-devant du monde le cœur serein. Rester droit face aux pires menaces et affronter la mort sans faillir, voilà la grande ambition du stoïcisme. En des temps troublés, l'Européen, quel que soit son rang, trouvera dans le Manuel tous les outils pour y arriver. Par la méditation, la raison et la maîtrise de soi il pourra se forger jour après jour une antique et véritable tenue. Le stoïcisme est également l'une des traditions par laquelle on peut se rapprocher du divin puis enfin mériter soi-même ce qualificatif. Devenir « pareil au Dieux » fut l'une des grandes inspirations de nos plus lointains ancêtres au sein de toute l'Europe. Germains et Celtes aux ancêtres divins ou Latins et Hellènes rêvant de prendre place à la table des Dieux, tous étaient habités par cette métaphysique de l'absolu qui guide nos âmes depuis nos origines. Une métaphysique de l'absolu qui les poussait à rechercher la perfection, l'harmonie, la beauté. Avec la raison menant au divin et le divin menant à la raison, le stoïcisme réussit un syncrétisme que beaucoup ont cherché à réaliser en vain pendant des siècles. Et cette sagesse n'est nullement incompatible avec les fois chrétiennes comme avec nos antiques fois européennes. Le libre penseur, l'incroyant lui-même n'en est pas exclu. Voilà pourquoi celui qui ouvre Le Manuel aura alors pour horizon l'Europe toute entière et ce, à travers toutes ses époques. Que celui qui contemple alors notre histoire se rappelle ces paroles d'Hector dans L'Iliade 5 (XII, 243) : « Il n'est qu'un bon présage, celui de combattre pour sa patrie ».

Aller au-devant du monde le cœur serein. Rester droit face aux pires menaces et affronter la mort sans faillir, voilà la grande ambition du stoïcisme. En des temps troublés, l'Européen, quel que soit son rang, trouvera dans le Manuel tous les outils pour y arriver. Par la méditation, la raison et la maîtrise de soi il pourra se forger jour après jour une antique et véritable tenue. Le stoïcisme est également l'une des traditions par laquelle on peut se rapprocher du divin puis enfin mériter soi-même ce qualificatif. Devenir « pareil au Dieux » fut l'une des grandes inspirations de nos plus lointains ancêtres au sein de toute l'Europe. Germains et Celtes aux ancêtres divins ou Latins et Hellènes rêvant de prendre place à la table des Dieux, tous étaient habités par cette métaphysique de l'absolu qui guide nos âmes depuis nos origines. Une métaphysique de l'absolu qui les poussait à rechercher la perfection, l'harmonie, la beauté. Avec la raison menant au divin et le divin menant à la raison, le stoïcisme réussit un syncrétisme que beaucoup ont cherché à réaliser en vain pendant des siècles. Et cette sagesse n'est nullement incompatible avec les fois chrétiennes comme avec nos antiques fois européennes. Le libre penseur, l'incroyant lui-même n'en est pas exclu. Voilà pourquoi celui qui ouvre Le Manuel aura alors pour horizon l'Europe toute entière et ce, à travers toutes ses époques. Que celui qui contemple alors notre histoire se rappelle ces paroles d'Hector dans L'Iliade 5 (XII, 243) : « Il n'est qu'un bon présage, celui de combattre pour sa patrie ».