Ex: http://gestion-des-risques-interculturels.com

Confirmation du diagnostic

Wikileaks a permis de lever le voile sur ce qui était déjà une évidence : les Américains sont clairement engagés dans une stratégie d’influence de vaste ampleur vis-à-vis des minorités en France. Pour les lecteurs de ce blog, et notamment de l’article du 16 septembre dernier Les banlieues françaises, cibles de l’influence culturelle américaine, il ne s’agit pas là d’une découverte mais d’une confirmation : oui, il y a une claire et nette entreprise de manipulation des minorités en France par les Américains. Les opérations mises en œuvre sont scrupuleusement planifiées, suivies et évaluées.

Tel est le constat auquel on parvient à la lecture du rapport de l’actuel ambassadeur des Etats-Unis en France, Charles Rivkin, envoyé le 19 janvier 2010 au Secrétariat d’Etat américain, sous le titre : EMBASSY PARIS – MINORITY ENGAGEMENT STRATEGY (Ambassade de Paris – Stratégie d’engagement envers les minorités). Je vous propose donc une sélection et une traduction d’extraits de ce rapport.

Voici le plan de ce rapport dont le vocabulaire offensif ne laisse pas de doute sur l’ambition des actions initiées :

- SUMMARY (Résumé)

- BACKGROUND: THE CRISIS OF REPRESENTATION IN FRANCE (Arrière-plan: la crise de la représentation en France)

- A STRATEGY FOR FRANCE: OUR AIMS (Une stratégie pour la France: nos objectifs)

- TACTIC 1: ENGAGE IN POSITIVE DISCOURSE (S’engager dans un discours positif)

- TACTIC 2: SET A STRONG EXAMPLE (Mettre en avant un exemple fort)

- TACTIC 3: LAUNCH AGGRESSIVE YOUTH OUTREACH (Lancer un programme agressif de mobilisation de la jeunesse)

- TACTIC 4: ENCOURAGE MODERATE VOICES (Encourager les voix modérées)

- TACTIC 5: PROPAGATE BEST PRACTICES (Diffuser les meilleures pratiques)

- TACTIC 6: DEEPEN OUR UNDERSTANDING OF THE PROBLEM (Approfondir notre compréhension du problème)

- TACTIC 7: INTEGRATE, TARGET, AND EVALUATE OUR EFFORTS (Intégrer, cibler et évaluer nos efforts)

SUMMARY (Résumé)

« In keeping with France’s unique history and circumstances, Embassy Paris has created a Minority Engagement Strategy that encompasses, among other groups, the French Muslim population and responds to the goals outlined in reftel A. Our aim is to engage the French population at all levels in order to amplify France’s efforts to realize its own egalitarian ideals, thereby advancing U.S. national interests. While France is justifiably proud of its leading role in conceiving democratic ideals and championing human rights and the rule of law, French institutions have not proven themselves flexible enough to adjust to an increasingly heterodox demography. »

« Au regard des circonstances et de l’histoire uniques de la France, l’Ambassade de Paris a créé une Stratégie d’Engagement envers les Minorités qui concerne, parmi d’autres groupes, les musulmans français, et qui répond aux objectifs définis dans le reftel A [référence télégramme A]. Notre objectif est de mobiliser la population française à tous les niveaux afin d’amplifier les efforts de la France pour réaliser ses propres idéaux égalitaires, ce qui par suite fera progresser les intérêts nationaux américains. Alors que la France est à juste titre fière de son rôle moteur dans la conception des idéaux démocratiques et dans la promotion des droits de l’homme et de l’Etat de droit, les institutions françaises ne se sont pas montrées elles-mêmes assez flexibles pour s’adapter à une démographie de plus en plus hétérodoxe. »

Notons que l’essentiel de la démarche américaine consiste à aider la France à se réaliser dans les faits. En somme, il s’agit de pousser les Français à passer de la parole aux actes en matière d’égalitarisme. Cette volonté d’aider la France n’est évidemment pas désintéressée : l’objectif indirect est de faire progresser les intérêts nationaux américains.

BACKGROUND: THE CRISIS OF REPRESENTATION IN FRANCE (Arrière-plan: la crise de la représentation en France)

« France has long championed human rights and the rule of law, both at home and abroad, and justifiably perceives itself as a historic leader among democratic nations. This history and self-perception will serve us well as we implement the strategy outlined here, in which we press France toward a fuller application of the democratic values it espouses. »

« La France a longtemps fait la promotion des droits de l’homme et de l’Etat de droit, à la fois sur son territoire et à l’étranger, et se perçoit elle-même à juste titre comme un leader historique parmi les nations démocratiques. Cette histoire et cette perception de soi nous serviront d’autant plus que nous mettrons en œuvre la stratégie exposée ici, et qui consiste à faire pression sur la France afin qu’elle s’oriente vers une application plus complète des valeurs démocratiques qu’elle promeut. »

Le point de vue qui sous-tend le projet américain est que la France n’est pas assez démocratique, et donc pas à la hauteur de ses propres idéaux. L’idée des Américains n’est donc pas de jouer la France contre elle-même mais de reprendre à leur compte le discours français dans une stratégie d’influence.

« The French media remains overwhelmingly white, with only modest increases in minority representation on camera for major news broadcasts. Among French elite educational institutions, we are only aware that Sciences Po has taken serious steps to integrate. While slightly better represented in private organizations, minorities in France lead very few corporations and foundations. Thus the reality of French public life defies the nation’s egalitarian ideals. In-group, elitist politics still characterize French public institutions, while extreme right, xenophobic policies hold appeal for a small (but occasionally influential) minority. »

« Les médias français restent très largement blancs, avec seulement une modeste amélioration de la représentation des minorités face aux caméras des principaux journaux télévisés. Parmi les institutions éducatives de l’élite française, nous ne connaissons que Sciences-Po qui ait pris d’importantes mesures en faveur de l’intégration. Alors qu’on note une légère amélioration de leur représentation dans les organisations privées, les minorités en France sont à la tête de très peu d’entreprises et de fondations. Ainsi, la réalité de la vie publique française s’oppose aux idéaux égalitaires de la nation. Les institutions publiques françaises se définissent encore par des groupes d’initiés et des politiques élitistes, tandis que l’extrême droite et les mesures xénophobes ne présentent de l’intérêt que pour une petite minorité (mais occasionnellement influente). »

Dans le passage précédent (non traduit ici), l’ambassadeur remarquait la sous-représentation politique des minorités en France. Il en va de même au niveau médiatique et dans le secteur privé. Il démontre clairement et simplement en quoi la France vit en permanence dans une tension contradictoire entre les principes affichés et la réalité de la vie publique.

« We believe France has not benefited fully from the energy, drive, and ideas of its minorities. Despite some French claims to serve as a model of assimilation and meritocracy, undeniable inequities tarnish France’s global image and diminish its influence abroad. In our view, a sustained failure to increase opportunity and provide genuine political representation for its minority populations could render France a weaker, more divided country. The geopolitical consequences of France’s weakness and division will adversely affect U.S. interests, as we need strong partners in the heart of Europe to help us promote democratic values. »

« Nous croyons que la France n’a pas profité complètement de l’énergie, du dynamisme et des idées de ses minorités. Malgré certaines prétentions françaises à servir de modèle à l’assimilation et à la méritocratie, d’indéniables inégalités ternissent l’image globale de la France et affaiblissent son influence à l’étranger. Selon notre point de vue, un échec durable pour développer les opportunités et fournir une authentique représentation politique à sa population minoritaire pourrait faire de la France un pays plus faible et plus divisé. Les conséquences géopolitiques de la faiblesse et de la division de la France affecteront négativement les intérêts américains, dans la mesure où nous avons besoin de partenaires forts au cœur de l’Europe pour nous aider à promouvoir les valeurs démocratiques. »

Les Américains vont donc utiliser à leur profit cette contradiction française. Leur crainte est de voir là un possible affaiblissement de la France, et donc des intérêts américains en Europe. Implicitement, il est affirmé que la France reste une tête de pont essentielle pour les intérêts américains en Europe.

A STRATEGY FOR FRANCE: OUR AIMS (Une stratégie pour la France: nos objectifs)

« The overarching goal of our minority outreach strategy is to engage the French population at all levels in order to help France to realize its own egalitarian ideals. Our strategy has three broad target audiences in mind: (1) the majority, especially the elites; (2) minorities, with a focus on their leaders; (3) and the general population. Employing the seven tactics described below, we aim (1) to increase awareness among France’s elites of the benefits of expanding opportunity and the costs of maintaining the status quo; (2) to improve the skills and grow the confidence of minority leaders who seek to increase their influence; (3) and to communicate to the general population in France that we particularly admire the diversity and dynamism of its population, while emphasizing the advantages of profiting from those qualities by expanding opportunities for all. »

« L’objectif essentiel de notre stratégie de sensibilisation envers les minorités consiste à mobiliser la population française à tous les niveaux afin de l’aider à réaliser ses propres objectifs égalitaires. Notre stratégie est concentrée sur trois grands publics cibles : (1) la majorité, et spécialement les élites ; (2) les minorités, avec une attention particulière pour les leaders ; (3) et la population en général. En utilisant les sept tactiques ci-dessous, nous visons (1) à accroître la conscience des élites de France à propos des bénéfices qu’il y a à élargir les opportunités et des coûts qu’il y a à maintenir le statu quo ; (2) à améliorer les compétences et développer la confiance des leaders de la minorité qui cherchent à augmenter leur influence ; (3) et à communiquer à la population générale de France notre admiration particulière pour la diversité et le dynamisme de sa population, tout en insistant sur les avantages qu’il y a à bénéficier de ses qualités en ouvrant les opportunités pour tous. »

TACTIC 1: ENGAGE IN POSITIVE DISCOURSE (S’engager dans un discours positif)

« First, we will focus our discourse on the issue of equal opportunity. When we give public addresses about the community of democracies, we will emphasize, among the qualities of democracy, the right to be different, protection of minority rights, the value of equal opportunity, and the importance of genuine political representation. »

« Premièrement, nous concentrerons nos discours sur le problème de l’égalité des chances. Quand nous ferons des déclarations publiques au sujet de la communauté des démocraties, nous insisterons sur les qualités de la démocratie, dont le droit à être différent, la protection des droits des minorités, la valeur de l’égalité des chances et l’importance d’une authentique représentation politique. »

« We will endeavor to convey the costs to France of the under-representation of minorities, highlighting the benefits we have accumulated, over time, by working hard to chip away at the various impediments faced by American minorities. We will, of course, continue to adopt a humble attitude regarding our own situation in the U.S., but nevertheless will stress the innumerable benefits accruing from a proactive approach to broad social inclusion, complementing our French partners on any positive steps they take. »

« Nous nous efforcerons d’informer sur les coûts liés à une sous-représentation des minorités en France, tout en soulignant les avantages que nous avons accumulés dans le temps en travaillant durement pour éliminer les obstacles rencontrés par les minorités américaines. »

Le projet des Américains consiste à dire aux Français qu’ils peuvent réussir à valoriser les minorités comme eux-mêmes l’ont fait aux Etats-Unis. Ce passage est important dans la mesure où il démontre en quoi l’ambassadeur plaque sur la réalité française une grille de lecture américaine et idéologique. Américaine, car l’ambassadeur ne prend absolument pas en compte le fait que les minorités aux Etats-Unis et en France n’ont pas la même histoire ni le même devenir. Ce n’est pas parce qu’il y a en France des Noirs que l’on peut aborder la question de leur représentation et de leur reconnaissance de la même façon qu’aux Etats-Unis.

Cette grille de lecture est également idéologique car elle suppose que les Américains ont vraiment résolu la question de la représentation et de la reconnaissance des minorités. Or, les barrières du communautarismes sont encore plus grandes aux Etats-Unis qu’en France. En outre, face à la question des minorités indiennes qui reste toujours aujourd’hui très problématique, on ne peut pas dire que les Etats-Unis aient fait preuve d’un grand zèle pour éliminer les obstacles rencontrés par ces dernières.

« In addition, we will continue and intensify our work with French museums and educators to reform the history curriculum taught in French schools, so that it takes into account the role and perspectives of minorities in French history. »

« De plus, nous poursuivrons et intensifierons notre travail avec les musées français et les enseignants pour réformer les programmes d’histoire enseignés dans les écoles françaises, de telle sorte qu’ils prennent en compte le rôle et le point de vue des minorités dans l’histoire de France. »

A la lecture de ce passage, il faut avouer notre étonnement devant l’ampleur des actions d’influence des Américains qui cherchent à orienter les politiques culturelles et les programmes scolaires. Nous aimerions en savoir plus sur les actions d’influence initiées par les Américains auprès des musées et enseignants…

TACTIC 2: SET A STRONG EXAMPLE (Mettre en avant un exemple fort)

« Second, we will employ the tool of example. We will continue and expand our efforts to bring minority leaders from the U.S. to France, working with these American leaders to convey an honest sense of their experience to French minority and non-minority leaders alike. When we send French leaders to America, we will include, as often as possible, a component of their trip that focuses on equal opportunity. In the Embassy, we will continue to invite a broad spectrum of French society to our events, and avoid, as appropriate, hosting white-only events, or minority-only events. »

« Deuxièmement, nous utiliserons le moyen de l’exemple. Nous poursuivrons et élargirons nos efforts pour faire venir en France des leaders des minorités des Etats-Unis, en travaillant avec ces leaders américains pour communiquer un jugement honnête de leur expérience aux mêmes leaders français issus des minorités ou non. Quand nous enverrons des leaders français en Amérique, nous inclurons aussi souvent que possible un élément de leur séjour qui concernera l’égalité des chances. A l’Ambassade, nous continuerons à inviter à nos événements un large spectre de la société française et nous éviterons ainsi d’organiser des événements où il n’y aurait que des blancs ou que des minorités. »

Je vous renvoie ici aux nombreux exemples rassemblés sur ce blog dans Les banlieues françaises, cibles de l’influence culturelle américaine.

TACTIC 3: LAUNCH AGGRESSIVE YOUTH OUTREACH (Lancer un programme agressif de mobilisation de la jeunesse)

« Third, we will continue and expand our youth outreach efforts in order to communicate about our shared values with young French audiences of all socio-cultural backgrounds. Leading the charge on this effort, the Ambassador’s inter-agency Youth Outreach Initiative aims to engender a positive dynamic among French youth that leads to greater support for U.S. objectives and values. »

« Troisièmement, nous poursuivrons et étendrons nos efforts de sensibilisation de la jeunesse afin de communiquer sur nos valeurs communes avec le jeune public français de quelque origine socioculturelle que ce soit. En soutenant le poids de cet effort, l’interagence Youth Outreach Initiative de l’Ambassadeur vise à produire une dynamique positive parmi la jeunesse française qui mène à un soutien plus grand pour les objectifs et les valeurs des Etats-Unis. »

« To achieve these aims, we will build on the expansive Public Diplomacy programs already in place at post, and develop creative, additional means to influence the youth of France, employing new media, corporate partnerships, nationwide competitions, targeted outreach events, especially invited U.S. guests.

- We will also develop new tools to identify, learn from, and influence future French leaders.

- As we expand training and exchange opportunities for the youth of France, we will continue to make absolutely certain that the exchanges we support are inclusive.

- We will build on existing youth networks in France, and create new ones in cyberspace, connecting France’s future leaders to each other in a forum whose values we help to shape — values of inclusion, mutual respect, and open dialogue. »

« Afin de réaliser ces objectifs, nous nous appuierons sur les ambitieux programmes de Diplomatie Publique déjà en place au poste et nous développerons des moyens créatifs et complémentaires pour influencer la jeunesse de France en employant les nouveaux médias, des partenariats privés, des concours sur le plan national, des événements de sensibilisation ciblés, notamment des hôtes américains invités.

- Nous développerons aussi de nouveaux outils pour identifier les futurs leaders français, apprendre d’eux et les influencer.

- Dans la mesure où nous développons les opportunités de formation et d’échange pour la jeunesse de France, nous continuerons à nous assurer d’une façon absolument certaine que les échanges que nous soutenons soient inclusifs.

- Nous nous appuierons sur les réseaux de la jeunesse existant en France et nous en créerons de nouveaux dans le cyberespace en reliant entre eux les futurs leaders de France au sein d’un forum dont nous aiderons à former les valeurs, des valeurs d’inclusion, de respect mutuel et de dialogue ouvert. »

Influencer la jeunesse de France et les futurs leaders français. Nous sommes bien là dans la « diplomatie publique » dans sa version la plus offensive, c’est-à-dire comme effort d’un Etat pour façonner les cœurs et les esprits d’une population étrangère dans le sens de ses intérêts. Dans les différentes affirmations et convictions que l’ambassadeur exprime ici, on peut noter une sorte d’ivresse de la puissance douce : les Américains peuvent tout faire, même influence la jeunesse de tout un pays, et de surcroît de la France.

Ainsi, la France serait-elle aussi facilement manipulable qu’un pays du tiers-monde ? Il faut croire que tel est le cas, car on sent dans ce passage une ferme volonté des Américains pour prendre en main les minorités et la jeunesse françaises littéralement laissées en jachère par les autorités françaises. Cet extrait du rapport de l’ambassadeur résonne comme un humiliant désaveu de trente années de politiques publiques en matière d’intégration. Tout responsable politique qui lirait ce passage et qui aurait un minimum de conscience des intérêts nationaux devrait d’urgence réunir les acteurs sociaux qui sont sous son autorité pour réfléchir à un tel désastre.

TACTIC 4: ENCOURAGE MODERATE VOICES (Encourager les voix modérées)

« Fourth, we will encourage moderate voices of tolerance to express themselves with courage and conviction. Building on our work with two prominent websites geared toward young French-speaking Muslims — oumma.fr and saphirnews.com — we will support, train, and engage media and political activists who share our values. »

« Quatrièmement, nous encouragerons les voix modérées de la tolérance à s’exprimer elles-mêmes avec courage et conviction. En appuyant notre action sur deux sites internet très en vue tournés vers les jeunes musulmans francophones – oumma.fr et saphirnews.com – nous soutiendrons, nous formerons et nous mobiliserons les militants médiatiques et politiques qui partagent nos valeurs. »

Ce passage a obligé les sites oumma.com (et non .fr) et saphirnews à une sorte de coming out sur leurs relations avec l’ambassade des Etats-Unis en France:

1. oumma.com : « Nous entretenons effectivement des rapports cordiaux avec le personnel de l’ambassade et ce contact privilégié nous a permis, par exemple, de décrocher l’exclusivité d’un entretien avec Farah Pandith, membre de l’Administration Obama. »

2. saphirnews : « Des liens ont en effet été tissés depuis longtemps entre les officiels américains en France et Saphirnews, qui a été amené, par exemple, à rencontrer la porte-parole du Congrès américain, Lynne Weil, en décembre 2008, pour discuter de l’état de la société française. Entre autres rencontres, soulignons aussi la présence de Farah Pandith, représentante spéciale pour les communautés musulmanes au département d’État américain, à l’occasion du premier anniversaire de Salamnews, le premier mensuel gratuit des cultures musulmanes. »

« We will share in France, with faith communities and with the Ministry of the Interior, the most effective techniques for teaching tolerance currently employed in American mosques, synagogues, churches, and other religious institutions. We will engage directly with the Ministry of Interior to compare U.S. and French approaches to supporting minority leaders who seek moderation and mutual understanding, while also comparing our responses to those who seek to sow hatred and discord. »

« Nous partagerons en France – avec les communautés religieuses et avec le Ministère de l’Intérieur – les techniques les plus efficaces pour enseigner la tolérance actuellement utilisées dans les mosquées américaines, les synagogues, les églises et les autres institutions religieuses. Nous nous impliquerons directement avec le Ministère de l’Intérieur afin de comparer les approches françaises et américaines en matière de soutien aux leaders des minorités qui promeuvent la modération et la compréhension mutuelle, tout en comparant nos réponses à celles de ceux qui cherchent à semer la haine et la discorde. »

TACTIC 5: PROPAGATE BEST PRACTICES (Diffuser les meilleures pratiques)

« Fifth, we will continue our project of sharing best practices with young leaders in all fields, including young political leaders of all moderate parties so that they have the toolkits and mentoring to move ahead. We will create or support training and exchange programs that teach the enduring value of broad inclusion to schools, civil society groups, bloggers, political advisors, and local politicians. »

« Cinquièmement, nous poursuivrons ce projet visant à partager les meilleures pratiques avec les jeunes leaders dans tous les domaines, y compris les jeunes leaders politiques de tous les partis modérés, telle sorte qu’ils disposent de la boîte à outils et de l’accompagnement nécessaires à leur progrès. Nous créerons et soutiendrons les programmes de formation et d’échanges pour enseigner les bienfaits durables d’une large inclusion aux écoles, aux groupes de la société civile, aux blogueurs, aux conseillers politiques et aux responsables politiques locaux. »

Au sujet de cet accompagnement des futurs leaders français, je vous renvoie à l’interview d’Ali Soumaré où ce dernier décrit ses contacts et entretiens avec le personnel de l’ambassade américaine à Paris.

TACTIC 6: DEEPEN OUR UNDERSTANDING OF THE PROBLEM (Approfondir notre compréhension du problème)

« Examining significant developments in depth, such as the debate on national identity (reftel B), we plan to track trends and, ideally, predict change in the status of minorities in France, estimating how this change will impact U.S. interests. »

« En examinant en profondeur des développements importants, tel que le débat sur l’identité nationale, nous projetons de suivre les tendances et, idéalement, de prédire les changements concernant le statut des minorités en France, en évaluant comment ce changement affectera les intérêts américains. »

TACTIC 7: INTEGRATE, TARGET, AND EVALUATE OUR EFFORTS (Intégrer, cibler et évaluer nos efforts)

« Finally, a Minority Working Group will integrate the discourse, actions, and analysis of relevant sections and agencies in the Embassy. This group, working in tandem with the Youth Outreach Initiative, will identify and target influential leaders and groups among our primary audiences. »

« Enfin, un Groupe de Travail sur les Minorités intégrera les discours, actions et analyses des sections concernées et des agences de l’Ambassade. Ce groupe travaillera en tandem avec le Youth Outreach Initiative, il identifiera et ciblera les leaders et les groupes influents au sein de notre public principal. »

« It will also evaluate our impact over the course of the year, by examining both tangible and intangible indicators of success. Tangible changes include a measurable increase in the number of minorities leading and participating in public and private organizations, including elite educational institutions; growth in the number of constructive efforts by minority leaders to organize political support both within and beyond their own minority communities; new, proactive policies to enhance social inclusion adopted by non-minority level; decrease in popular support for xenophobic political parties and platforms. While we could never claim credit for these positive developments, we will focus our efforts in carrying out activities, described above, that prod, urge and stimulate movement in the right direction. »

« Il évaluera également notre impact au cours d’une année en examinant des indicateurs de succès à la fois matériels et immatériels. Les changements matériels incluent une augmentation mesurable du nombre de minorités dirigeantes ou membres d’organisations publiques ou privées, y compris au sein des établissements d’enseignement de l’élite ; une croissance du nombre d’efforts constructifs par les leaders des minorités pour obtenir un soutien politique à la fois au sein et au-delà de leur propre communauté minoritaire ; un reflux du soutien populaire pour les partis et programmes politiques xénophobes. Comme nous ne pourrons jamais revendiquer le crédit pour de tels développements positifs, nous concentrerons nos efforts sur les activités décrites ci-dessus qui encouragent, poussent et stimulent le mouvement dans la bonne direction. »

Important ici : même si les Américains réussissent à inspirer des progrès en matière de reconnaissance et de promotion de la diversité en France, ils ne pourront jamais en revendiquer le crédit. C’est en effet la vraie marque de l’action d’influence que de ne pouvoir être revendiquée par son initiateur. Tout l’enjeu consiste donc à disparaître derrière des relais d’opinion et d’influence dont le crédit est garanti par la transparence de leurs actions et de leurs idées. Voilà qui tombe à l’eau pour les Américains : nous savons désormais que derrière le discours et les actes de certains se profile l’ombre américaine.

Cependant, il ne faut pas voir dans ces dernières lignes une obsession pour la théorie du complot. Si le document dont vous venez de lire ici des extraits renforce l’idée que la France est sous influence américaine, c’est tout simplement parce que les Américains ne font qu’exploiter les béances qui caractérisent la société française. Tout comme la nature, la société a horreur du vide. Les Américains ont bien compris qu’il y avait un réel danger pour la France, et par suite pour leurs propres intérêts, à laisser ces béances s’aggraver.

Cependant, il ne faut pas voir dans ces dernières lignes une obsession pour la théorie du complot. Si le document dont vous venez de lire ici des extraits renforce l’idée que la France est sous influence américaine, c’est tout simplement parce que les Américains ne font qu’exploiter les béances qui caractérisent la société française. Tout comme la nature, la société a horreur du vide. Les Américains ont bien compris qu’il y avait un réel danger pour la France, et par suite pour leurs propres intérêts, à laisser ces béances s’aggraver.

En somme, les actions d’influence des Américains en France ne font que révéler l’échec complet de nos élites politiques en matière de reconnaissance et de promotion de la diversité. Laisser les Américains le faire à notre place revient à laisser s’imposer en France une grille américaine de lecture de la société française. Ce filtre biaisé appelle une approche critique pour ne pas renoncer à la maîtrise de ce que nous sommes et de ce que nous souhaitons devenir. En effet, en restant passifs, nous courons un double risque :

1. de ne pas relever le défi de nos contradictions en produisant par nous-mêmes les outils et moyens de les résoudre – à ce titre, le travail du sociologue Hugues Lagrange dans son livre Le déni des cultures mérite une lecture attentive, notamment lorsque ce dernier démarque la problématique française des minorités de la problématique américaine,

2. de voir se multiplier en France les relais d’influence et du point de vue des Etats-Unis, aujourd’hui lycéens, étudiants, jeunes militants ou créateurs qui feront la France de demain – car contrairement aux clichés, les Américains sont capables de se projeter dans le long terme et ils savent pertinemment que les petites actions entreprises aujourd’hui en faveur de la diversité en France produiront plus tard de vastes effets en faveur des intérêts politiques, mais aussi économiques, des Etats-Unis.

* * *

- Vous avez un projet de formation pour vos expatriés, une demande de cours ou de conférence sur le management interculturel?

- Vous souhaitez engager le dialogue sur vos retours d’expérience ou partager une lecture ou une ressource ?

- Vous pouvez consulter mon profil, la page des formations et des cours et conférences et me contacter pour accompagner votre réflexion.

Quelques suggestions de lecture:

La politique est cette « activité contingente, qui s’exprime dans des institutions variables et dans des évènements historiques de toutes sortes » : non seulement la politique politicienne, celle de tous les jours, mais encore les changements de régimes et systèmes politiques, ne sont que des épiphénomènes qui obéissent, en vérité, à une série d’invariants liés à la nature humaine.

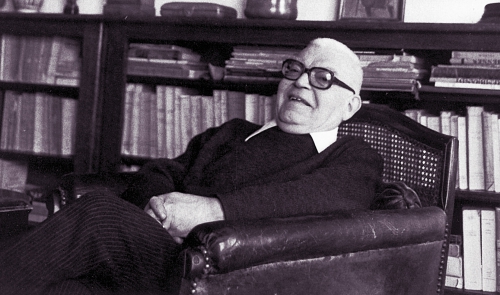

La politique est cette « activité contingente, qui s’exprime dans des institutions variables et dans des évènements historiques de toutes sortes » : non seulement la politique politicienne, celle de tous les jours, mais encore les changements de régimes et systèmes politiques, ne sont que des épiphénomènes qui obéissent, en vérité, à une série d’invariants liés à la nature humaine.  La relation privé - public, attribuée au « Julien Freund libéral », définit la frontière de la sphère privée au sein de la société, celle où l'individu est libre de ses choix, en tout cas par rapport à la collectivité. La position de cette frontière peut certes fluctuer selon les lieux et les époques, mais de même que pour le principe de puissance, il est impossible de s'en débarrasser. Même dans les régimes totalitaires, il existe toujours quelques activités et relations qui échappent au contrôle de l’État. Sous cet angle, l'histoire de l'Occident semble animée par une aspiration permanente à étendre cette sphère privée, alors que le totalitarisme est un effort pour effacer la distinction entre privé et public. Cette dialectique entre sphère privée et publique est vitale, car c'est elle qui est source de la vie et du dynamisme de la société: ce ne sont pas les institutions encadrant le génie et l'activité individuelles qui produisent les innovations, mais à l'inverse, sans ce cadre, les initiatives individuelles ne pourraient s'épanouir et bénéficier à l'ensemble de la société.

La relation privé - public, attribuée au « Julien Freund libéral », définit la frontière de la sphère privée au sein de la société, celle où l'individu est libre de ses choix, en tout cas par rapport à la collectivité. La position de cette frontière peut certes fluctuer selon les lieux et les époques, mais de même que pour le principe de puissance, il est impossible de s'en débarrasser. Même dans les régimes totalitaires, il existe toujours quelques activités et relations qui échappent au contrôle de l’État. Sous cet angle, l'histoire de l'Occident semble animée par une aspiration permanente à étendre cette sphère privée, alors que le totalitarisme est un effort pour effacer la distinction entre privé et public. Cette dialectique entre sphère privée et publique est vitale, car c'est elle qui est source de la vie et du dynamisme de la société: ce ne sont pas les institutions encadrant le génie et l'activité individuelles qui produisent les innovations, mais à l'inverse, sans ce cadre, les initiatives individuelles ne pourraient s'épanouir et bénéficier à l'ensemble de la société. Q: Cette inimitié entre sociétés et les guerres qui en résultent sont présentées comme naturelles à l'homme. Faut-il comprendre naturelles à l'homme déchu ou à l'homme tel que Dieu l'a créé originellement?

Q: Cette inimitié entre sociétés et les guerres qui en résultent sont présentées comme naturelles à l'homme. Faut-il comprendre naturelles à l'homme déchu ou à l'homme tel que Dieu l'a créé originellement?

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Ce signe montre la dynamique du nombre trois. Les trois points qui entourent celui du centre (invariable milieu) permettent de tracer un triangle équilatéral. Simultanément, on les voit emportés dans le mouvement continu de doubles spirales métaphoriques de la force vitale universelle. Pareil ternaire c’est, au niveau humain, le père, la mère et l’enfant, constitutifs d’une famille, ou encore les trois générations nécessaires à la transmission du savoir. Symbole tournoyant, le triskèle sera repris par l’art gothique. Dans son livre intitulé « L’Art Gaulois », Jean Varagnac, ancien conservateur en chef du Musée des Antiquités nationales de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, affirmait, preuves à l’appui, que le monde celtique s’était prolongé sous un vêtement spirituel chrétien durant tout le Moyen Âge. Contrairement, donc, à ce qu’affirment les histrions actuels pour qui il serait vain de chercher une continuité entre la Gaule et les temps médiévaux.

Ce signe montre la dynamique du nombre trois. Les trois points qui entourent celui du centre (invariable milieu) permettent de tracer un triangle équilatéral. Simultanément, on les voit emportés dans le mouvement continu de doubles spirales métaphoriques de la force vitale universelle. Pareil ternaire c’est, au niveau humain, le père, la mère et l’enfant, constitutifs d’une famille, ou encore les trois générations nécessaires à la transmission du savoir. Symbole tournoyant, le triskèle sera repris par l’art gothique. Dans son livre intitulé « L’Art Gaulois », Jean Varagnac, ancien conservateur en chef du Musée des Antiquités nationales de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, affirmait, preuves à l’appui, que le monde celtique s’était prolongé sous un vêtement spirituel chrétien durant tout le Moyen Âge. Contrairement, donc, à ce qu’affirment les histrions actuels pour qui il serait vain de chercher une continuité entre la Gaule et les temps médiévaux.

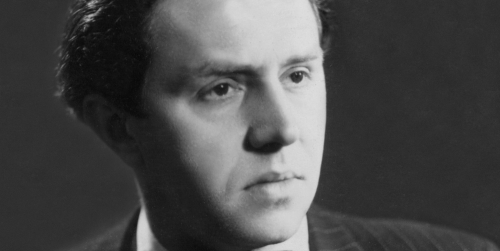

Il a le sourire chafouin, les yeux cendrés au fond desquels un feu puissant s’accroche, une blancheur crue qui enchâsse la passion dans le corps. Lucien Rebatet publie Les Deux Étendards en 1952. Du même geste, il met la littérature de son temps à la remorque. Pavillon de mots troué par l’envie et la jeunesse, la musique et la littérature, l’œuvre s’empare dès son titre de la question religieuse comme un bloc épais et total liant l’amour charnel au renoncement chrétien, clouant la nervosité d’une foi véritable à un nietzschéisme libérateur. Car c’est bien un double tableau ignacien entre la Jérusalem promise et la plaine de Babylone qui charpente ce grand roman d’amour dans une tension vitale, « de deux étendards, l’un de Jésus-Christ, notre Chef suprême et Seigneur, l’autre de Lucifer, mortel ennemi de notre nature humaine ».

Il a le sourire chafouin, les yeux cendrés au fond desquels un feu puissant s’accroche, une blancheur crue qui enchâsse la passion dans le corps. Lucien Rebatet publie Les Deux Étendards en 1952. Du même geste, il met la littérature de son temps à la remorque. Pavillon de mots troué par l’envie et la jeunesse, la musique et la littérature, l’œuvre s’empare dès son titre de la question religieuse comme un bloc épais et total liant l’amour charnel au renoncement chrétien, clouant la nervosité d’une foi véritable à un nietzschéisme libérateur. Car c’est bien un double tableau ignacien entre la Jérusalem promise et la plaine de Babylone qui charpente ce grand roman d’amour dans une tension vitale, « de deux étendards, l’un de Jésus-Christ, notre Chef suprême et Seigneur, l’autre de Lucifer, mortel ennemi de notre nature humaine ». Rebatet propose donc une refondation du christianisme sur son nerf premier

Rebatet propose donc une refondation du christianisme sur son nerf premier

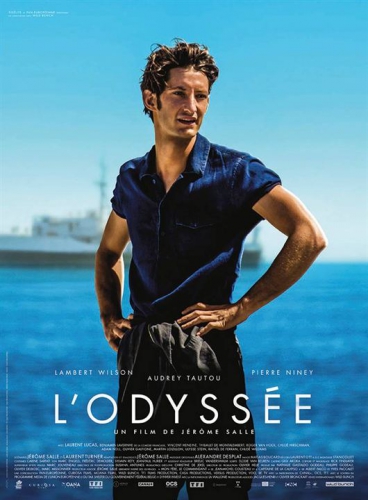

Autour de la figure de Jacques-Yves Cousteau, interprété par Lambert Wilson, L'Odyssée, film de Jérôme Salle, César du meilleur premier film pour Anthony Zimmer, nous entraîne dans trente années qui vont forger un mythe en même temps que changer le monde : 1949-1979. Deux mondes que toute oppose. Derrière l'Odyssée, nous assistons plutôt à une série d'odyssées, celle de la famille Cousteau, celle de la France triomphante des Trente Glorieuses, celle, au final, de l'écologie balbutiante.

Autour de la figure de Jacques-Yves Cousteau, interprété par Lambert Wilson, L'Odyssée, film de Jérôme Salle, César du meilleur premier film pour Anthony Zimmer, nous entraîne dans trente années qui vont forger un mythe en même temps que changer le monde : 1949-1979. Deux mondes que toute oppose. Derrière l'Odyssée, nous assistons plutôt à une série d'odyssées, celle de la famille Cousteau, celle de la France triomphante des Trente Glorieuses, celle, au final, de l'écologie balbutiante. Le rêve Cousteau se transforme ainsi peu à peu en cauchemar pour son équipage et son épouse, attachés à la Calypso, alors que le Commandant se rend dans les soirées mondaines à New-York ou à Paris. La décrépitude de son épouse, qui ressemble de plus en plus à une tenancière de bistrot de province, contraste avec l'allure de son mari, toujours impeccablement habillé, signant des autographes et séduisant les femmes. L'archétype de l'homme français, séducteur et agaçant qui parvient parfois à conquérir l'Amérique.

Le rêve Cousteau se transforme ainsi peu à peu en cauchemar pour son équipage et son épouse, attachés à la Calypso, alors que le Commandant se rend dans les soirées mondaines à New-York ou à Paris. La décrépitude de son épouse, qui ressemble de plus en plus à une tenancière de bistrot de province, contraste avec l'allure de son mari, toujours impeccablement habillé, signant des autographes et séduisant les femmes. L'archétype de l'homme français, séducteur et agaçant qui parvient parfois à conquérir l'Amérique.

Avec 21,7% des voix, l’Union de la Patrie (Tevynes Sajunga - LKD) avait remporté légèrement le premier tour, avec 0.17% de plus que le parti centriste des Paysans et Verts (LVZS = Lietuvos Valstieciu ir Zaliuju Sajunga, ex LVLS). Il avait obtenu 20 sièges contre 19 pour ces derniers. Mais le vote uninominal a inversé la donne car le LVZS a obtenu 35 sièges contre seulement 9 pour le TS-LKD, obtenant en tout 54 sièges sur 140. La majorité est éloignée mais au sein d’une coalition de centre-droit, le LVZS sera en position de force, le TS-LKD devant se contenter de 29 sièges. A eux deux néanmoins, ils sont majoritaires.

Avec 21,7% des voix, l’Union de la Patrie (Tevynes Sajunga - LKD) avait remporté légèrement le premier tour, avec 0.17% de plus que le parti centriste des Paysans et Verts (LVZS = Lietuvos Valstieciu ir Zaliuju Sajunga, ex LVLS). Il avait obtenu 20 sièges contre 19 pour ces derniers. Mais le vote uninominal a inversé la donne car le LVZS a obtenu 35 sièges contre seulement 9 pour le TS-LKD, obtenant en tout 54 sièges sur 140. La majorité est éloignée mais au sein d’une coalition de centre-droit, le LVZS sera en position de force, le TS-LKD devant se contenter de 29 sièges. A eux deux néanmoins, ils sont majoritaires.

Tant que l'Union européenne se développait d’une manière relativement réussie, les eurosceptiques étaient plutôt une force politique marginale, sans être un concurrent pour les grands partis politiques soutenant l'intégration européenne. Début 2008, la crise économique, dont la cause est le fruit d’une série de facteurs internes et externes interdépendants, se répand dans le monde. Le principal facteur interne était la crise de la zone euro associée à divers indicateurs économiques du « noyau » européen représenté par l'Allemagne, la France, la Grande-Bretagne et la Scandinavie, et la « périphérie »7. « Le noyau » européen a alors été contraint de maintenir à flot les pays « périphériques » situés dans l'arc « Atlantique-Méditerranée », de l'Irlande à la Grèce.

Tant que l'Union européenne se développait d’une manière relativement réussie, les eurosceptiques étaient plutôt une force politique marginale, sans être un concurrent pour les grands partis politiques soutenant l'intégration européenne. Début 2008, la crise économique, dont la cause est le fruit d’une série de facteurs internes et externes interdépendants, se répand dans le monde. Le principal facteur interne était la crise de la zone euro associée à divers indicateurs économiques du « noyau » européen représenté par l'Allemagne, la France, la Grande-Bretagne et la Scandinavie, et la « périphérie »7. « Le noyau » européen a alors été contraint de maintenir à flot les pays « périphériques » situés dans l'arc « Atlantique-Méditerranée », de l'Irlande à la Grèce. À la fin de 2010 les leaders européens tels que Angela MERKEL, la chancelière allemande, et David CAMERON, désormais l’ancien Premier ministre britannique, ont reconnu que les tentatives pour construire une société multiculturelle dans le continent ont échoué. Cependant, des moyens pratiques pour sortir de cette situation n'ont pas été proposés. Monsieur CAMERON a déclaré la nécessité de recourir au « libéralisme musclé »16 ce qui signifie en fait une continuation de l'ancienne politique non justifiée, mais par des méthodes encore plus forcées. Madame MERKEL a déploré le fait que les migrants ne soient pas particulièrement désireux d'intégrer la société allemande et d'apprendre l'allemand17. Malgré cela, à l’été de 2016, juste après les nouvelles attaques terroristes des islamistes en Europe, la chancelière allemande a confirmé qu'elle continuerait une politique de portes ouvertes aux migrants des pays musulmans18.

À la fin de 2010 les leaders européens tels que Angela MERKEL, la chancelière allemande, et David CAMERON, désormais l’ancien Premier ministre britannique, ont reconnu que les tentatives pour construire une société multiculturelle dans le continent ont échoué. Cependant, des moyens pratiques pour sortir de cette situation n'ont pas été proposés. Monsieur CAMERON a déclaré la nécessité de recourir au « libéralisme musclé »16 ce qui signifie en fait une continuation de l'ancienne politique non justifiée, mais par des méthodes encore plus forcées. Madame MERKEL a déploré le fait que les migrants ne soient pas particulièrement désireux d'intégrer la société allemande et d'apprendre l'allemand17. Malgré cela, à l’été de 2016, juste après les nouvelles attaques terroristes des islamistes en Europe, la chancelière allemande a confirmé qu'elle continuerait une politique de portes ouvertes aux migrants des pays musulmans18.

Pourquoi le Moyen-Orient avec ses communautés musulmanes, chrétiennes et juives a toujours été dévasté dans un état de “conflit perpétuel” qui est décidément insolvable et je ne me réfère pas seulement à ces 50-70 dernières années (depuis que l’état juif d’Israël fut fourbement établi), mais à une ère qui remonte à bien longtemps.

Pourquoi le Moyen-Orient avec ses communautés musulmanes, chrétiennes et juives a toujours été dévasté dans un état de “conflit perpétuel” qui est décidément insolvable et je ne me réfère pas seulement à ces 50-70 dernières années (depuis que l’état juif d’Israël fut fourbement établi), mais à une ère qui remonte à bien longtemps. Dans mon récent livre “Egypt knew no Pharaohs nor Israelites” j’ai élaboré sur les bases culturelles et géographiques communes que partagent à la fois le judaïsme et l’islam.

Dans mon récent livre “Egypt knew no Pharaohs nor Israelites” j’ai élaboré sur les bases culturelles et géographiques communes que partagent à la fois le judaïsme et l’islam.

Cependant, il ne faut pas voir dans ces dernières lignes une obsession pour la théorie du complot. Si le document dont vous venez de lire ici des extraits renforce l’idée que la France est sous influence américaine, c’est tout simplement parce que les Américains ne font qu’exploiter les béances qui caractérisent la société française. Tout comme la nature, la société a horreur du vide. Les Américains ont bien compris qu’il y avait un réel danger pour la France, et par suite pour leurs propres intérêts, à laisser ces béances s’aggraver.

Cependant, il ne faut pas voir dans ces dernières lignes une obsession pour la théorie du complot. Si le document dont vous venez de lire ici des extraits renforce l’idée que la France est sous influence américaine, c’est tout simplement parce que les Américains ne font qu’exploiter les béances qui caractérisent la société française. Tout comme la nature, la société a horreur du vide. Les Américains ont bien compris qu’il y avait un réel danger pour la France, et par suite pour leurs propres intérêts, à laisser ces béances s’aggraver.

Gagnée par l’ivresse de cette hybris puritaine qui s’étend à des domaines politiques, esthétiques ou métaphysique où elle n’a que faire, cette morale débordante, cette griserie narcissique du Bien abstrait, envahit et subjugue les consciences et les entendements humains au point de les aveugler sur le beau et sur le vrai qui, par essence, ne sont jamais acquis mais toujours à conquérir et appartiennent tout autant aux réalités sensibles, au frémissement de l’immanence, qu’aux réalités intelligibles.

Gagnée par l’ivresse de cette hybris puritaine qui s’étend à des domaines politiques, esthétiques ou métaphysique où elle n’a que faire, cette morale débordante, cette griserie narcissique du Bien abstrait, envahit et subjugue les consciences et les entendements humains au point de les aveugler sur le beau et sur le vrai qui, par essence, ne sont jamais acquis mais toujours à conquérir et appartiennent tout autant aux réalités sensibles, au frémissement de l’immanence, qu’aux réalités intelligibles.

Doneer Café Weltschmerz, we hebben uw steun hard nodig! NL23 TRIO 0390 4379 13 (Disclaimer: Wij betalen over uw gift in Nederland belasting)

Doneer Café Weltschmerz, we hebben uw steun hard nodig! NL23 TRIO 0390 4379 13 (Disclaimer: Wij betalen over uw gift in Nederland belasting)