mardi, 20 septembre 2011

Pierre Vial: Pourquoi fêtons-nous le cochon?

00:05 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cochon, traditions, nouvelle droite |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Die Schlagkraft des Aussenseiters: Das Werk Friedrich Sieburgs

|

Die Schlagkraft des Aussenseiters: Das Werk Friedrich Sieburgs Geschrieben von: Daniel Bigalke Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de

|

|

Die frühe Bundesrepublik galt Sieburg als entwurzelt Anfangs dem George-Kreis nahe stehend und später einer großen Öffentlichkeit bekannt durch seine Zeitungsartikel und Bücher, wie etwa Gott in Frankreich? von 1929, wurden einige seiner Schriften in der Sowjetischen Besatzungszone auf die Liste der auszusondernden Literatur gesetzt. Dies war auch dem Umstand zu verdanken, dass Sieburg anfänglich die nationalsozialistische Machtergreifung begrüßte und für das „neue Deutschland” warb. Dem westlichen Deutschland blieben seine politischen und philosophischen Urteile nicht verborgen. Denn Sieburg wurde nicht müde, sie plakativ in den Mittelpunkt der Debatte zu rücken. Ihm erschien die Bundesrepublik als entwurzelte Zone, die vom Konformismus ohne eigene geistige Leistungen geprägt sei.

Präzise Analyse der deutschen Mentalität Wo liegen für Sieburg die Ursachen dieser Entwicklung? Als Motor dafür macht er die Traditionslosigkeit der Deutschen aus, die sich nach dem Kriege ohne Vorbehalte der Gegenwart verschrieben, den Verlockungen des Konsums erlagen und sich durch Suche nach Vorteilen in neue Abhängigkeiten begaben. Damit eröffnet sich auch schon sein bedeutsames Schwerpunktthema: Das mangelnde Identitätsbewusstsein der Deutschen, die fehlende „deutsche Ganzheit“ im Vergleich zur englischen oder französischen Situation. Sieburg knüpft damit an eine Idee an, welche schon der Philosoph Rudolf Eucken (1846-1926) in seiner Schrift Zur Sammlung der Geister (1914) – freilich in einem anderen historischen Zusammenhalt - formulierte. Identität, Sorgfalt, feste Bindungen und inneres Wachstum des Menschen seien in Deutschland zu erstreben anstelle materialistischer Indienstnahme. Zugleich bestehe bei den Deutschen – folgt man nun wieder Sieburg - gerade durch den Anspruch des inneren Wachstums des Menschen eine Position des Schwankens zwischen extremen Zuständen. Größenwahn und Selbsthass, Provinzialismus und Weltbürgertum etwa würden sich von Zeit zu Zeit im politischen Handeln und geistigen Wirken der Deutschen kundtun. Die Lust am Untergang (Selbstgespräche auf Bundesebene) In der Tat sind dies etwa für die deutsche Philosophie über Fichte oder Hegel teilweise typische Eigenschaften. Für Sieburg können diese sich sogar im Politischen ebenso wie im Geistigen konkret über großartigen Ideenreichtum aber auch über schreckliche Selbstüberheblichkeit auswirken. Kaum ein anderer deutscher Intellektueller erkannte nach dem Weltkrieg diese geistige Disposition so wie Sieburg. Er brachte das quasi dialektische Problem auf den Punkt indem er meinte, die Deutschen litten am Unvermögen zur pragmatischen Lebensform auf der einen Seite und am (idealistischen) Hang zum Absoluten und zur Freiheit auf der anderen Seite. Besonders scharf formulierte Sieburg dies in seiner Essaysammlung Die Lust am Untergang (Selbstgespräche auf Bundesebene) von 1954. Hegel würde in seiner Staatsphilosophie hier noch zustimmend meinen, daß gerade der deutsche Drang zur absoluten Freiheit besonders charakteristisch gegenüber anderen europäischen Völkern sei. Demgemäß hätten sich die Deutschen nicht der Herrschaft eines einzigen Staates oder einer einzigen Religion aus Rom unterworfen. Sieburg steht aber mit seiner Erkenntnis des dialektischen Problems der deutschen Mentalität nicht in der Tradition eines deutschen Sonderbewusstseins. Sein nietzscheanisches Pathos der Distanz beschritt erfolgreich den Weg, nationale Identität zu stiften durch die Bewunderung der geistigen Ausstrahlung und der Leistungsfähigkeit, deren das Deutsche zeitweise fähig sei, ohne die dabei ebenso möglichen Risiken und tiefen Abgründe auszublenden. Das Los des schöpferischen Menschen Sieburg verkörpert das Los des schöpferischen Menschen. Er litt an seiner Heimat, ohne sie entbehren zu können. Er verachtete ihre Mittelmäßigkeit, nahm diese aber ernst und analysierte sie, um aus der Erkenntnis ihrer Ursachen neue Wege der Identitätsfindung für das Deutschland der Nachkriegszeit abzuleiten. Er liefert damit auch eine pragmatische Definition des Konservativismus, die aus einer freien Haltung heraus resultiert. Konservatismus möchte für Sieburg mehr, als die simplen Denkschablonen der sogenannten „Mitte“ und ihre immer wiederkehrenden Reproduktionen politischer Feindbilder. Die öden Versprechen von dauerhaftem Wohlstand und Konsumkraft seien nur ein Beispiel des wiederkehrenden deutschen Abgrundes und seiner idealistischen Ziele, denen es an Pragmatismus und Realismus fehle. Sieburgs Überlegungen beeindrucken durch die Schlagkraft des Exoten. Sie vermitteln zwischen deutscher idealistischer Tradition in der Philosophie und der Notwendigkeit des politischen Realismus in der frühen Nachkriegszeit. Sieburg und Thomas Mann Dieser Realismus benötige laut ihm keine Heilsversprechen. Zugleich findet man eine überzeugend formulierte mediale Inkompatibilität vor, die mit ihren Reflexionen zu den Folgen einer absoluten Demokratisierung des Menschen und der Gesellschaft oder mit der schlüssigen Analyse der deutschen Mentalität herzhaft erfrischt und an Thomas Manns Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen (1918) erinnert. Freilich sind die Schriften Sieburgs wesentlich authentischer, da dieser sich nicht von seinen Analysen distanzierte, wie dies Thomas Mann schon recht früh mit Blick auf seine Betrachtungen von 1918 tat. Zugleich lobte Sieburg Thomas Manns Gesamtwerk überschwänglich. Das spiegeln auch zahlreiche Urteile literarischer Zeitgenossen über Sieburg wider. Damit hat Friedrich Sieburg heute in seiner analytischen Tiefe viel mehr zu bieten als so manche stilisierte Ikone der deutschen Literatur nach 1945. |

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature, littérature allemande, allemagne, france, années 40, années 50, révolution conservatirce, friedrich sieburg |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 19 septembre 2011

Débat entre Aymeric Chauprade et Pierre Conesa sur la nécessité de l’ennemi pour imposer sa puissance

00:24 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : ennemi, carl schmitt, géopolitique, ayméric chauprade, pierre conesa, guerre, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Dr. R. Schmoeckel - Die Indoeuropäer

Reinhard SchmoeckelDie IndoeuropäerAufbruch aus der VorgeschichteBastei-Lübbe-Verlag (Taschenbuch)576 S. mit 24 Karten und Übersichten ISBN 3-404-64162-0 1. Auflage 1999, 4. Auflage vergriffen Überarbeitete und aktualisierte Neuauflage des erstmals 1982 im Rowohlt Verlag erschie- nenen Buches "Die Hirten, die die Welt ver- änderten – Der Aufbruch der indoeuropä- ischen Völker" |

Ganze Bibliotheken füllen die Bücher über die Geschichte der Griechen und Römer, Völker, die oft und gerne als Wiege unserer Zivilisation zitiert werden. Doch was geschah eigentlich, bevor die Griechen ihre Tempel bauten und die Römer ihre Legionen ausschickten ? Wer waren die Menschen, die dafür sorgten, dass man von Indien bis hin zu den äußersten Gestaden Westeuropas Sprachen spricht, die denselben geheimnisvollen Ursprung zu haben scheinen ?

Dr. Reinhard Schmoeckel machte sich auf die Suche nach unseren Ahnen, den Ahnen fast aller Europäer . Dieses Buch ist jenen Völkern gewidmet, aus deren Zeit keine oder so gut wie keine Dokumente überliefert sind: der Vorgeschichte. Dennoch weiß man heute schon sehr viel darüber. Man muss es nur wagen und das in Tausenden von dicken wissenschaftlichen Büchern verstreute Wissen allgemein verständlich darstellen. Das Buch versucht, die frühen Erlebnisse unserer Vorfahren, über die der historisch Normalgebildete sonst praktisch nie etwas erfährt, wenigstens in einem groben Überblick zu erhellen, Zusammenhänge deutlich zu machen und das Wichtigste über die wichtigsten frühen Kulturen und Völker indoeuropäischer Abstammung zu erzählen.

Stimmen zum Buch

(Rheinische Post)

...Spannender als mancher Abenteuerroman...

(Fuldaer Zeitung)

Dieses Buch beinhaltet all das Wissen über die indoeuropäischen Völker, das ich mir mühevoll aus zig Büchern zusammensuchen musste. Nie war umfassender komplexes Wissen so zugänglich.

(Leserurteil bei Amazon)

Een vulgair-wetenschappelijke inleiding tot de problematiek, die evenwel vlot leest en wetenschappelijke feiten afwisselt met een fictief verhaal.

00:05 Publié dans Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, proto-histoire, indo-européens |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Furiose Zeitkritik aus dem Geist des Pessimismus

Furiose Zeitkritik aus dem Geist des Pessimismus

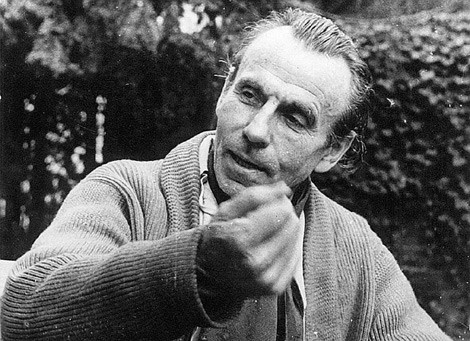

Erinnerungswürdig: Vor 50 Jahren verstarb der französische Dichter und Deutschenfreund Céline

Im Europa der 1930er Jahre, als rechtsautoritäre Bewegungen den überlebten Liberalismus fortspülten und einem neuen Leben den Weg ebneten, wollten auch viele Dichter nicht abseits stehen. In Frankreich war Louis-Ferdinand Céline einer der schroffsten Kritiker der liberalkapitalistischen Gesellschaftsordnung, die er für jüdisch durchsetzt hielt.

1894 wurde Louis-Ferdinand Destouches, der sich später Céline nannte, in kleinbürgerliche Verhältnisse hineingeboren. Achtzehnjährig meldete er sich zu einem Reiterregiment, mit dem er an der Flandernfront den Weltkrieg erlebte. Nach einem Aufenthalt in Kamerun studierte der Kriegsversehrte Medizin, dem sich in Amerika und Europa eine medizinische Gutachtertätigkeit für den Völkerbund anschloß. Ab 1927 arbeitete der Franzose in seiner Heimat als Armenarzt. Neben dem Kriegserlebnis schärfte dies seinen Wirklichkeitsblick und ließ ihn zu einem anarchischen Melancholiker werden.

Mit seinem Erstling »Reise ans Ende der Nacht« wurde Céline 1932 zu einem der großen Erneuerer der Literatur. Die Anerkennung für sein bahnbrechendes Schaffen können ihm selbst jene nicht verweigern, die Grund haben, ihm politisch ablehnend gegenüberzustehen. So stellte der jüdisch-amerikanische Gegenwartsautor Philip Roth über den Romancier fest: »Er ist wirklich ein sehr großer Schriftsteller. Auch wenn sein Antisemitismus ihn zu einer widerwärtigen, unerträglichen Gestalt macht. Um ihn zu lesen, muß ich mein jüdisches Bewußtsein abschalten, aber das tue ich, denn der Antisemitismus ist nicht der Kern seiner Romane. Céline ist ein großer Befreier.«

Noch 1995 unterstrich Ernst Jünger die nachhaltige Wirkung, die Céline auf ihn hatte. »Sein Roman machte großen Eindruck auf mich«, erklärte der damals Hundertjährige, »sowohl durch die Kraft des Stils als auch durch die nihilistische Atmosphäre, die er hervorrief und die in vollkommener Weise die Situation dieser Jahre widerspiegelte.« Noch viel stärker mußte sich der Jünger der 1920er und 30er Jahre von dem Werk angezogen fühlen, das dem bürgerlichen Zeitalter seine erschütternde Schadensbilanz präsentierte. So positiv Jünger die literarische Leistung und illusionsfreie Lebenssicht des Romanciers bewertete, so negativ fiel die Bewertung der Person und ihres »plakativen Antisemitismus« aus.

Eine neue Ästhetik

Mit Sprache, Form und Inhalt der »Reise ans Ende der Nacht« setzte sein Autor neue Akzente: Umgangs- und Schriftsprache wurden zu einer lebendigen Einheit verschmolzen, und der umstandslose Wechsel von Zeiten und Orten sprengte das konventionelle Erzählschema. Vor allem aber zog der Inhalt in seinen Bann. Mit einer Mischung aus bösartigem Spott, grimmigem Humor und kalter Abgeklärtheit wird eine kapitalistische Welt gezeigt, die es besser gar nicht gäbe. Welt und Mensch erscheinen als abgrundtief schlecht und berechtigen weder zu romantischen Fluchtbewegungen noch zu revolutionären Aufbrüchen.

Célines erzählerische Kraft erhält der Roman durch den autobiographischen Charakter. Die »Reise ans Ende der Nacht« zeichnet den Lebensweg eines jungen Franzosen nach, der durch die Schrecknisse des Ersten Weltkrieges, den Stumpfsinn des Lebens in einem afrikanischen Kolonialstützpunkt, die menschliche Kälte in der kapitalistischen Metropolis New York und das soziale Elend der Pariser Vorstädte um jegliches Weltvertrauen gebracht wird.

Auf den nordfranzösischen Schlachtfeldern durchleidet der Protagonist Ferdinand Bardamus – in seinem erbärmlichen Leben wie das Sturmgepäck eines Soldaten (franz.: barda) hin- und hergeworfen – das »Schlachthaus« und die »Riesenraserei« des Weltkrieges.

In düsteren Worten geißelte Céline die Sinnfreiheit des Krieges einschließlich des Sadismus der Vorgesetzten und des Zynismus der Heimatfront. Diese radikal negative Sicht auf das Kriegsgeschehen übersteigerte er jedoch derart, daß Waffendienst an der Nation, Heldentum und Vaterlandsliebe generell als niederer Wahn erscheinen. Damit fiel Célines grenzenlosem Nihilismus auch alles das zum Opfer, was Millionen seiner Zeitgenossen heilig war. Im Gegensatz zu Ernst Jünger wollte er im Krieg auch keine Gelegenheit zu einem vitalisierenden Stahlbad und zur Steigerung aller Erfahrungsmöglichkeiten sehen. In seinem unnationalen und unheldischen Zug ist der Roman Célines befremdlich.

Viel eher stimmt man der Darstellung des entmenschlichten Lebensalltags im amerikanischen Kapitalismus zu. Erschreckend gegenwärtig mutet es an, wenn der Autor sezierend den modernen Herdenmenschen mustert. »Unheilbare Melancholie« ergreift Ferdinand Bardamus, mehr noch, Lebensekel packt ihn angesichts der »gräßlich feindlichen Welt«, die er in New York vorfindet. Vereinsamung, billige Zerstreuungen, »Zwangsarbeit« in den Tretmühlen der Kapitalbesitzer und Kommerz (»dieses Krebsgeschwür der Welt«) münden in die Essenz der Célineschen Weltauffassung: »Ein Scheißspiel, das Leben.«

Antikommunismus und Antijudaismus

Die »Reise ans Ende der Nacht« wurde sowohl bei radikalen Rechten als auch Linken positiv aufgenommen, weil jede Seite eigene Gesinnungselemente zu entdecken glaubte: Die Linke rühmte Célines Antimilitarismus und Ablehnung des Hurrapatriotismus, die Rechte faszinierte seine Verdammung der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft, sein illusionsloser Blick auf das menschliche Wesen und seine Resistenz gegenüber Utopie- und Fortschrittsglauben.

Das für die politische Biographie entscheidende Damaskuserlebnis war eine Reise in die Sowjetunion, die der Autor 1936 in dem Buch »Mea culpa« verarbeitete. Der Bolschewismus stellte für den Franzosen den totalen Bankrott jeder Ethik dar. In den roten Revolutionären sah er Heuchler, die eine Besserung der Welt versprechen, aber nur Verbrechen begehen. Als Antikommunist und Judengegner war dann Célines Weg in das »faschistische« Lager vorgezeichnet.

Schon 1916 fand sich in Briefen des Autors Judenkritisches, das 1938 in dem Buch »Bagatelles pour un massacre« (in Deutschland unter dem Titel »Die Judenverschwörung in Frankreich« erschienen) radikalisiert wurde. Aufgrund ihrer Überrepräsentanz in den Schaltstellen der Macht seien die Juden für Dekadenz und Elend der westlichen Welt verantwortlich. In dem Buch »L’Ecole des cadavres« (1939) vertrat Céline zudem die Auffassung, daß der Untergang Frankreichs nicht zu beweinen sei, weil sich die Franzosen der jüdischen Macht ergeben und damit alle Chancen zu einer rassischen Auslese vertan hätten. Dem nationalsozialistischen Deutschland bleibe dieses Schicksal hingegen erspart, weil die Deutschen ihr Volkstum pflegten.

Von Adolf Hitler erwartete er auch für die Masse der Franzosen Hilfe, weil der »Führer« gezeigt habe, wie man ein Volk zu Nationalbewußtsein und Selbstachtung führe – ein deutlicher Positionswechsel gegenüber früher, wo er Patriotismus als Herrschaftsmittel zu entlarven suchte.

Die Schrift »Les beaux draps« (1941) ist eine Hymne auf die militärische Niederlage Frankreichs im Juni 1940 und die Möglichkeit eines deutsch-französischen Bündnisses. Die Schuld am Scheitern dieser Perspektive gab er seinen Landsleuten, weil sie nur halbherzig mit den Deutschen zusammengearbeitet hätten. Es kam nicht die ersehnte Einheitspartei – eine »Partei der sozialistischen Arier« und nationalgesinnten (nichtjüdischen) Franzosen –, sondern das verhaßte Parteiensystem blieb auch nach der Niederlage bestehen.

In der Besatzungszeit unterhielt Céline Kontakte zu zahlreichen Persönlichkeiten des öffentlichen Lebens. Damals war der Dichter längst zu einer Figur auf dem politischen Parkett geworden, der an Veranstaltungen für die Kollaboration teilnahm und die »Parti Populaire Français« des Jacques Doriot aufgrund ihres antikommunistischen und antijüdischen Programms unterstützte.

Im Dezember 1941 begegnete Ernst Jünger Céline im Deutschen Institut in Paris und hielt über dessen Forderung an die deutsche Besatzungspolitik fest: »Er sprach sein Befremden, sein Erstaunen darüber aus, daß wir Soldaten die Juden nicht erschießen, aufhängen, ausrotten – sein Erstaunen darüber, daß jemand, dem die Bajonette zur Verfügung stehen, nicht unbeschränkten Gebrauch davon mache.« – Interessante Ansichten eines Franzosen, die zeigen, wie die deutsche Besatzungspolitik in Frankreich entgegen den Behauptungen der Umerziehungshistoriker eben nicht war.

Im Juni 1944 floh Céline mit seiner Frau ins deutsche Sigmaringen, wo sich bereits die Vichy-Regierung befand. Gegen Ende des Krieges setzte er sich nach Dänemark ab, wo er einige Jahre in Gefängnissen und Krankenhäusern zubrachte. In seinem Heimatland wurde Louis-Ferdinand Céline als Landesverräter verurteilt, aber 1950 amnestiert. In der »deutschen Trilogie« verarbeitete er seine Erlebnisse im Zweiten Weltkrieg und »drückte seine subversive Freude am Untergang der westlichen Zivilisation aus« (Franz W. Seidler).

Subversive Untergangsfreude

Was kann einem Céline heute noch sagen? Der Befund einer aus den Fugen geratenen, gänzlich entwerteten Welt ist aktueller denn je. Dabei hat sich der im Juli 1961 – vor ziemlich genau 50 Jahren – Verstorbene wohl nicht vorstellen können, daß seine Zeit verglichen mit dem Hier und Heute noch beinah intakte Bestände des Menschlichen aufwies. Es dürfte für ihn unvorstellbar gewesen sein, daß die »Reise ans Ende der Nacht« erst im 21. Jahrhundert als Höllenfahrt Europas richtig an Fahrt gewinnt.

Der von Céline so erschütternd und gleichzeitig großartig beschriebenen Nacht des Niedergangs muß ein neuer Morgen folgen. Bleibt er aus, gähnt wirklich nur noch das große Nichts und der Tod der europäischen Kulturvölker.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, france |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

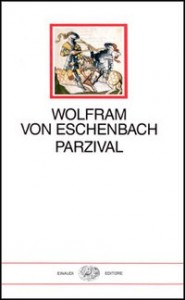

Wolfram von Eschenbach e i Custodi del Graal

Wolfram von Eschenbach e i Custodi del Graal

Ex: http://www.centrostudilaruna.it/

Fra gli autori dei racconti del Graal Wolfram von Eschenbach occupa un posto speciale dovuto non solo al particolare impianto narrativo della sua opera, ma soprattutto ai numerosissimi elementi dottrinali che l’arricchiscono di un simbolismo e di prospettive spirituali persino islamiche non sempre emerse con chiarezza negli altri compositori del ciclo del Graal.

Wolfram intende dare voce ad una speciale tradizione spirituale sulla quale addirittura dichiara di aver costruito il suo Parzival. Questa tradizione è personificata in “Kyot il Provenzale”, un personaggio straordinario al quale difficilmente potrà essere data una fisionomia precisa. Nel Parzival appare poche volte (VIII, 417, 431, IX, 453-454, 455, XVI, 827), tutte tese a dare importanza a questa fonte e a rimarcare la diversità di molti simboli del Parzival rispetto a quelli emersi nel Perceval di Chrétien de Troyes. Ciò che rende particolarmente interessante la funzione di “Kyot il Provenzale”, di questo maestro “cantore”, o forse e più esattamente “incantatore” [= schianture], è il contatto che tramite lui sembra essersi stabilito fra la tradizione cristiana, quella giudaica e l’Islam, con tutto ciò che questi contatti hanno potuto comportare sul piano dottrinale, simbolico e, forse, rituale. I cenni a Toledo, alla Spagna, alla Provenza, a Baghdad, al Baruc, a Feirefiz, così come il legame fra Flegetanis, Kyot e Salomone, sono a questo riguardo molto significativi e richiamano la presenza eccezionale di kabbalisti, sufi e contemplativi cristiani presso le corti musulmane di Spagna e in quelle della Provenza trovadorica.

Senza supporre una fonte islamica diretta resterebbe enigmatica la presenza nel Parzival di termini e di dottrine astrologiche sicuramente arabe. Si potrebbe anche menzionare l’enigmatico riferimento di Wolfram a quel cavaliere musulmano che in un duello con Anfortas, “re e patrono del Graal”, ferisce inguaribilmente il sovrano cristiano con la sua lancia, un cavaliere “nativo di Ethnise [=“la terra originaria”], là dove scorre il Tigri giù dal Paradiso” (IX, 479). Come chiarisce Wolfram subito dopo (IX, 481), questo Tigri è uno dei quattro fiumi del Paradiso terrestre e perciò assume un rilievo simbolico rilevante la correlazione fra Ethnise, il Paradiso e l’Islam che rimanda ai tanti cenni similari contenuti in quasi tutte le composizioni di questa materia. La ferita di Anfortas è provocata da un cavaliere islamico “nativo di Ethnise” e la sua “insufficienza” come re del Graal scaturisce dal “colpo di lancia” di un rappresentante dell’Islam. Con apparente casualità, Wolfram presenta l’Islam come una tradizione radicata nella rivelazione “originaria” (=Ethnise), ma nel contempo evidenzia caratteri “escatologici” che sembrerebbero indicare nell’Islam la tradizione più idonea a combattere contro le perversioni dei tempi ultimi.

Senza supporre una fonte islamica diretta resterebbe enigmatica la presenza nel Parzival di termini e di dottrine astrologiche sicuramente arabe. Si potrebbe anche menzionare l’enigmatico riferimento di Wolfram a quel cavaliere musulmano che in un duello con Anfortas, “re e patrono del Graal”, ferisce inguaribilmente il sovrano cristiano con la sua lancia, un cavaliere “nativo di Ethnise [=“la terra originaria”], là dove scorre il Tigri giù dal Paradiso” (IX, 479). Come chiarisce Wolfram subito dopo (IX, 481), questo Tigri è uno dei quattro fiumi del Paradiso terrestre e perciò assume un rilievo simbolico rilevante la correlazione fra Ethnise, il Paradiso e l’Islam che rimanda ai tanti cenni similari contenuti in quasi tutte le composizioni di questa materia. La ferita di Anfortas è provocata da un cavaliere islamico “nativo di Ethnise” e la sua “insufficienza” come re del Graal scaturisce dal “colpo di lancia” di un rappresentante dell’Islam. Con apparente casualità, Wolfram presenta l’Islam come una tradizione radicata nella rivelazione “originaria” (=Ethnise), ma nel contempo evidenzia caratteri “escatologici” che sembrerebbero indicare nell’Islam la tradizione più idonea a combattere contro le perversioni dei tempi ultimi.

Un altro elemento fondamentale che mostra la profondità della presenza islamica in Wolfram è lo strano destino di Feirefiz, “Bianco-Nero”, che accompagnerà il fratello Parzival a Munsalvaetsche e dopo il suo battesimo sposerà la Fanciulla del Graal, Repanse de Schoye, “la Dispensatrice di Gioia”, la personificazione della Sedes Sapientiae. Un terzo dato è la descrizione del palazzo reale che si trova in XIII, 589-590, tanto precisa ed articolata da convincere Hermann Göetz che qui si ha la trasposizione dello schema-base del palazzo dei Califfi di Baghdad e, forse, persino un cenno ad un famoso stûpa del re kushana Kanishka. Da parte sua Lars-Ivar Ringbom ha mostrato che anche la pianta architettonica del Tempio del Graal descritta da Albrecht von Scharfenberg nel suo poema può essere compresa solo comparandola alla struttura del palazzo di Taxt-i Sulayman,“il Trono di Salomone”, l’antico santuario mazdeo del fuoco chiamato Taxt-i Taqdis, ”il Trono degli Archi”, costruito dal re Chosroe II e poi distrutto dall’imperatore bizantino Eraclio nel 629, quando inseguì le truppe sassanidi sconfitte e recuperò la “Vera Croce” razziata precedentemente dai Persiani a Gerusalemme.

L’insieme di questi dati e la loro articolazione attentamente contessuta con l’intreccio cristiano e con il sostrato antico-celtico della saga, mostra molto più di una semplice, vaga “influenza” islamica e ci conduce invece nell’ambito di una realtà teofanica, l’âlam al-mithâl che secondo Henry Corbin sostanziava la futuwwa, la “cavalleria spirituale” iranica.

L’insieme di questi dati e la loro articolazione attentamente contessuta con l’intreccio cristiano e con il sostrato antico-celtico della saga, mostra molto più di una semplice, vaga “influenza” islamica e ci conduce invece nell’ambito di una realtà teofanica, l’âlam al-mithâl che secondo Henry Corbin sostanziava la futuwwa, la “cavalleria spirituale” iranica.

Per designare il “Paradiso perduto” mèta di ogni cavaliere, Wolfram introduce lo strano termine di Munsalvaetsche, “Monte Selvaggio”, introvabile nella letteratura precedente. Munsalvaetsche si ritrova almeno una trentina di volte nel Parzival e addirittura in V, 251 è associato ad una straordinaria dinastia regale. Esso è poi ripreso senza nessuna variazione nello Jüngerer Titurel del suo continuatore Albrecht von Scharfenberg, fra i compilatori di questi scritti l’unico ad evidenziare con forza elementi dottrinali rapportabili al mondo spirituale iranico e, più in generale, al simbolismo islamico-orientale che sembrerebbe trovarsi sotteso nell’opera di Wolfram. Anche Albrecht pone il Tempio del Graal a Munt Salvaesch, nel cuore di Salvaterre, una regione protetta dall’impenetrabile Foreist Salvaesch. Aggiunge poi che dopo che gli angeli lo hanno trasportato a Munt Salvaesch, Titurel decide di costruirvi un tempio per intronarvi degnamente il Graal.

Il simbolismo della montagna è ben conosciuto. La particolare strutturazione di ogni montagna ne fa per eccellenza un’immagine dell’axis mundi che congiunge la terra e il Cielo, il mondo del divenire e delle apparenze con la realtà dell’essere immutabile e “lucente”. Per questa sua “assialità” la montagna cosmica non può trovarsi che al centro della manifestazione universale, nel punto dal quale si dipartono tutti i raggi che come infiniti lampi di luce si riverberano sui vari piani cosmici. E’ il luogo privilegiato di ogni teofania, là dove il divino si svela e si fa riconoscere dagli uomini.

Nell’Islam la montagna Qâf, considerata inaccessibile agli uomini comuni, è detta la “montagna della saggezza”, un simbolismo che accosta la sapienza divina e la montagna. Nei Vangeli si usa distinguere il monte dove il Cristo si ritira spesso a pregare, dalla pianura in cui si trovano i semplici fedeli. La Trasfigurazione si compie sul Tabor, un “alto monte” dice Matteo 17, 1. È il luogo in cui il Cristo si mostra “così come Egli è”, nello Splendore divino che da significato alle tradizioni concernenti Mosé e Elia e nel quale si svela la Volontà celeste. Il Sermone delle Beatitudini viene pronunciato su un monte (Matteo 5, 1 sgg.; Luca, 6, 17 sgg.), ed è qui che si ha l’indicazione delle basi spirituali della dottrina cristiana, la rivelazione delle condizioni per accedere alla stessa realtà “immacolata” delle origini. Secondo una tradizione molto diffusa nell’Oriente Ortodosso, anche il Golgota era una montagna posta “al centro del mondo” dove fu sepolta “la testa” del Primo Uomo e nel quale verrà piantata la croce del Cristo: la rivelazione primordiale “ferita” dal peccato di Adamo, viene riscattata dal Cristo “nuovo Adamo”.

Wolfram aggiunge (V, 251) che Munsalvaetsche si trova al centro di un regno posto nella Terra de Salvaetsche, “la Terra Selvaggia” nella quale “non è stato mai tagliato albero o pietra”, ossia un luogo che gode di una condizione immacolata, la proiezione nel tempo e nello spazio della “gioia” perpetua che regna a Munsalvaetsche, nella perfetta rispondenza fra la condizione spirituale sperimentata dal re Titurel e l’ambiente cosmico nel quale si riversano le “qualità divine”, quelle che dal punto di vista umano vengono colte come semplici virtù. Per la sua particolare ambientazione molto prossima a quella riferita al simbolismo del Paradiso perduto, risulta impossibile che con “selvaggia” si volesse indicare la sede del Graal caratterizzandola come “brutale”, “istintiva”, etc. La stessa sua collocazione in medio mundi, il suo custodire il Graal e le “virtù” che esso veicola ne rende assurda l’ipotesi. In realtà, nelle opere del XII e del XIII secolo, al nascere delle varie letterature cosiddette nazionali, si trovano abbastanza diffusamente espressioni similari che danno un’indicazione preziosa su quello di cui si tratta. L’esempio più conosciuto è senza dubbio il “vulgare illustre” di Dante, un’espressione enigmatica ed in sé persino contraddittoria. Nel suo De vulgari eloquentia Dante precisa che con tale formula intende riferirsi alla lingua naturale, quella parlata allo origini stesse della creazione, alla “forma locutionis creata dallo stesso Dio insieme alla prima anima”, la lingua appresa da Adamo nell’Eden per comunicazione diretta dello stesso Creatore. Una lingua rivelata direttamente da Dio costituisce di per sé una particolare forma di teofania ed un veicolo di salvezza, ed è perciò evidente che l’espressione “vulgare illustre” non può indicare una lingua priva di radicamenti nella dimensione del sacro, parlata dal “volgo”, “popolare”. Al contrario, designa lo stesso “linguaggio primordiale” che nei termini medievali è la tradizione primigenia, la condizione spirituale dell’umanità delle origini, prima che il peccato originale allontanasse gli uomini dall’Eden.

Wolfram aggiunge (V, 251) che Munsalvaetsche si trova al centro di un regno posto nella Terra de Salvaetsche, “la Terra Selvaggia” nella quale “non è stato mai tagliato albero o pietra”, ossia un luogo che gode di una condizione immacolata, la proiezione nel tempo e nello spazio della “gioia” perpetua che regna a Munsalvaetsche, nella perfetta rispondenza fra la condizione spirituale sperimentata dal re Titurel e l’ambiente cosmico nel quale si riversano le “qualità divine”, quelle che dal punto di vista umano vengono colte come semplici virtù. Per la sua particolare ambientazione molto prossima a quella riferita al simbolismo del Paradiso perduto, risulta impossibile che con “selvaggia” si volesse indicare la sede del Graal caratterizzandola come “brutale”, “istintiva”, etc. La stessa sua collocazione in medio mundi, il suo custodire il Graal e le “virtù” che esso veicola ne rende assurda l’ipotesi. In realtà, nelle opere del XII e del XIII secolo, al nascere delle varie letterature cosiddette nazionali, si trovano abbastanza diffusamente espressioni similari che danno un’indicazione preziosa su quello di cui si tratta. L’esempio più conosciuto è senza dubbio il “vulgare illustre” di Dante, un’espressione enigmatica ed in sé persino contraddittoria. Nel suo De vulgari eloquentia Dante precisa che con tale formula intende riferirsi alla lingua naturale, quella parlata allo origini stesse della creazione, alla “forma locutionis creata dallo stesso Dio insieme alla prima anima”, la lingua appresa da Adamo nell’Eden per comunicazione diretta dello stesso Creatore. Una lingua rivelata direttamente da Dio costituisce di per sé una particolare forma di teofania ed un veicolo di salvezza, ed è perciò evidente che l’espressione “vulgare illustre” non può indicare una lingua priva di radicamenti nella dimensione del sacro, parlata dal “volgo”, “popolare”. Al contrario, designa lo stesso “linguaggio primordiale” che nei termini medievali è la tradizione primigenia, la condizione spirituale dell’umanità delle origini, prima che il peccato originale allontanasse gli uomini dall’Eden.

Allo stesso modo, l’accostamento del simbolo della montagna all’aggettivo “selvaggio” in un contesto complessivo nel quale è centrale il Graal e il suo simbolismo, non intende indirizzare verso l’”istintivo” o il “brutale”, ma completa il simbolo della montagna cosmica con l’indicazione di un tipo di spiritualità aurorale. L’aggettivo “selvaggio” si trova usato come l’equivalente di “originario”, “primordiale”, “naturale”, esattamente come il “vulgare” di Dante. La “Montagna Selvaggia” di Wolfram è perciò la “Montagna originaria” nella quale il cavaliere che ha potuto contemplare il Graal si ritrova in condizioni spirituali “naturali”, reintegrato nella stessa “interezza” goduta da Adamo, in un Eden che questi testi indicano non come un giardino, ma come una montagna inaccessibile.

E tuttavia Munsalvaetsche è solo uno dei tanti termini criptici di cui abbonda il testo di Wolfram, termini e nomi costruiti secondo necessità d’ordine simbolico. Si è sostenuto che Herzeloyde, Condwiramurs, Gahmuret, Shoye de la Kurte, Feirefiz, Terdelaschoye, etc., corrispondano ad esempi di virtù cavalleresche, a particolari ideali raccomandati agli ascoltatori dei racconti, a sentimenti capaci di rendere universale il dramma vissuto da questo o quel protagonista. In realtà, il tecnicismo e lo stesso valore ermeneutico con il quale si caratterizzano i tanti nomi dei personaggi, dei luoghi o delle ambientazioni, risponde a necessità di un ordine completamente diverso da quello di un semplice ideale cavalleresco. Nell’intento di Wolfram si tratta di vere e proprie personificazioni di “entità spirituali” tese a determinare comportamenti, “modi di essere” che incidono nelle profondità dell’anima umana, trasformazioni interiori che scaturiscono da una dimensione superiore, precedente a quella del mondo fenomenico, “forme formanti” che rivelano modalità dell’”agire divino” nella storia, “epifanie” che indirizzano verso il significato veritiero dell’essere cosmico ed umano.

E tuttavia Munsalvaetsche è solo uno dei tanti termini criptici di cui abbonda il testo di Wolfram, termini e nomi costruiti secondo necessità d’ordine simbolico. Si è sostenuto che Herzeloyde, Condwiramurs, Gahmuret, Shoye de la Kurte, Feirefiz, Terdelaschoye, etc., corrispondano ad esempi di virtù cavalleresche, a particolari ideali raccomandati agli ascoltatori dei racconti, a sentimenti capaci di rendere universale il dramma vissuto da questo o quel protagonista. In realtà, il tecnicismo e lo stesso valore ermeneutico con il quale si caratterizzano i tanti nomi dei personaggi, dei luoghi o delle ambientazioni, risponde a necessità di un ordine completamente diverso da quello di un semplice ideale cavalleresco. Nell’intento di Wolfram si tratta di vere e proprie personificazioni di “entità spirituali” tese a determinare comportamenti, “modi di essere” che incidono nelle profondità dell’anima umana, trasformazioni interiori che scaturiscono da una dimensione superiore, precedente a quella del mondo fenomenico, “forme formanti” che rivelano modalità dell’”agire divino” nella storia, “epifanie” che indirizzano verso il significato veritiero dell’essere cosmico ed umano.

Lo stesso ritmo narrativo sembra essere ordinato attorno ad un simbolismo onnipervadente. Si pensi per esempio al significato di Parzival (XVI, 822) inteso a raccontare l’origine della dinastia del “prete Gianni”: “Repanse de Schoye fu lieta del suo viaggio. In India ella diede alla luce un figlio che si chiamò Giovanni. I re di quelle terre da allora presero quel nome”, una frase che potrebbe essere resa così: “La “Dispensatrice di Gioia=Grazie” dà alla luce Giovanni [=”Grazia di Dio”] dal quale si origina una linea di sovrani-sacerdoti che elargiscono “gioia-grazie” sino alla fine dei tempi”. Dalla grazia, attraverso la grazia, grazie infinite. Questo tipo di costruzione ritmica si trova ovunque nel Parzival, tocca i dialoghi, le dispute, la configurazione dell’iter narrativo, l’ambientazione, le spiegazioni dottrinali, il significato attribuito ad un dato personaggio e indica un intero universo simbolico, rimanda ad un ordine di valori originatisi dall’âlam al-mithâl, il mundus imaginalis delle dottrine shiite, il “luogo” delle teofanie e degli archetipi divini dal quale si originano le “forme formanti” che danno consistenza alla manifestazione cosmica.

Un tale simbolismo affiora in modo determinante nei due capitoli iniziali del Parzival, quelli più estranei all’opera di Chrétien e nei quali Wolfram sembra volere precisare il significato del suo racconto distinguendolo completamente da quelli dei narratori precedenti, compresi i quattro autori delle Continuations. Sono le pagine nelle quali appare Gahmuret l’Anschouwe, ”l’Angioino”, assolutamente sconosciuto a Chrétien, ai compositori franco-normanni e al ciclo del Lancelot-Graal. Alla morte del padre Gahmuret va a combattere al servizio del califfo di Baghdad e dopo una serie interminabile di avventure, da un fuggevole amore con la regina musulmana Belakane, “Nera come la notte”, senza neanche sospettarlo ha un figlio di nome Feirefiz, “Bianco-Nero”. Le sue successive avventure lo portano in Spagna dove apprende la morte del fratello, diventa l’erede della propria dinastia, vince un torneo e ottiene in sposa Herzeloyde, “Cuore doloroso”, la regina di Valois “Bianca come la luce del sole”, che 14 giorni dopo la morte di Gahmuret darà alla luce Parzival: “il nome significa trapassare [o “penetrare”] nel mezzo”, dice Wolfram (Parzival, III, 140) con un evidente gioco fonetico costruito sull’antico francese percer, “trapassare”, “penetrare”, fatto perchè Parzival, il re del Graal, diventi il simbolico “Colui che passa per il centro”, l’Asse cosmico.

Un tale simbolismo affiora in modo determinante nei due capitoli iniziali del Parzival, quelli più estranei all’opera di Chrétien e nei quali Wolfram sembra volere precisare il significato del suo racconto distinguendolo completamente da quelli dei narratori precedenti, compresi i quattro autori delle Continuations. Sono le pagine nelle quali appare Gahmuret l’Anschouwe, ”l’Angioino”, assolutamente sconosciuto a Chrétien, ai compositori franco-normanni e al ciclo del Lancelot-Graal. Alla morte del padre Gahmuret va a combattere al servizio del califfo di Baghdad e dopo una serie interminabile di avventure, da un fuggevole amore con la regina musulmana Belakane, “Nera come la notte”, senza neanche sospettarlo ha un figlio di nome Feirefiz, “Bianco-Nero”. Le sue successive avventure lo portano in Spagna dove apprende la morte del fratello, diventa l’erede della propria dinastia, vince un torneo e ottiene in sposa Herzeloyde, “Cuore doloroso”, la regina di Valois “Bianca come la luce del sole”, che 14 giorni dopo la morte di Gahmuret darà alla luce Parzival: “il nome significa trapassare [o “penetrare”] nel mezzo”, dice Wolfram (Parzival, III, 140) con un evidente gioco fonetico costruito sull’antico francese percer, “trapassare”, “penetrare”, fatto perchè Parzival, il re del Graal, diventi il simbolico “Colui che passa per il centro”, l’Asse cosmico.

Gahmuret discende da Mazadan e dalla “fata” Terdelashoye, “la Terra della Gioia”, che nei termini indù corrispondono al “re divino” e alla sua shakti = sposa-potenza. Mazadan è il Primo Uomo, il prototipo dell’umanità che necessariamente deve personificare una forma di perfetta sovranità universale, mentre Terdelaschoye in virtù del suo status di “fata”, di entità del mondo intermedio, incarna la “potenza divina”, la “gioia celeste” divenuta la stessa creazione immacolata di Dio, la manifestazione cosmica nella sua purezza originaria, prima che a causa della ribellione di Lucifero fosse imprigionata nella sfera temporale e transeunte. Questa linea di cavalieri-sovrani si concluderà col “prete Gianni”, colui che più di tutti dovrà perpetuare anche nei tempi ultimi la “pienezza” spirituale attribuita al tempo di Mazadan.

Dall’unione di Mazadan e Terdelaschoye si sviluppa una continuità dinastica che si concluderà con i due figli di Gandin, il cui cadetto sarà Gahmuret restato “cavaliere errante” fino alla morte del fratello. Il passaggio dalla dimensione individuale di Gahmuret alla sua condizione di centralità cosmica tipica di ogni sovrano universale è indicata da Wolfram con un particolare che doveva risultare chiarissimo agli ascoltatori del suo romanzo. Quando ancora era un “cavaliere errante” il blasone raffigurato sulle sue armi e sullo scudo era l’anker (=l’àncora, “che conviene ad un cavaliere errante”, II, 99; forse un simbolo di “radicamento” volutamente opposto allo status di “cavaliere errante” del giovane Gahmuret), ma poi avendo acquisito la dignità di sovrano dopo la morte del fratello, eredita l’insegna araldica della pantera (“Sul suo scudo fu incisa sull’ermellino la pantherther che portava suo padre”, II, 101). Il simbolismo che in questo caso Wolfram inserisce per caratterizzare il passaggio di Gahmuret da “cavaliere errante” a “sovrano” riproduce sotto molti aspetti quello, con caratterizzazioni archetipali, del viaggio spirituale intrapreso da ogni “pellegrino-straniero” che alla fine delle proprie vicissitudini raggiunge una sorta di “terra promessa”. È lo schema di trasformazione interiore che si ritrova in una molteplicità di racconti, tutti mirati all’ottenimento di un nuovo e diverso status spirituale e al raggiungimento di una straordinaria Terra Santa. Il particolare termine usato da Wolfram per indicare il blasone di Gahmuret illumina sul significato della sua “centralità sovrana” e sui motivi della sua adozione di un emblema appartenuto da sempre agli Anschouwe. Secondo gli studiosi di araldica, infatti, pantherther significa “tutto divino”, ”ciò che unisce molteplici forme divine”, mentre la stessa picchettatura del manto dell’animale è stata interpretata come l’immagine del cielo stellato. La pantera del blasone degli Anschouwe che adorna lo scudo di Gahmuret, nipote di Uther Pendragon e lontano prozio del “prete Gianni”, sembrerebbe confermare perciò la condizione di un re con attribuzioni cosmiche, un Sovrano Universale.

Ma perché Wolfram insiste tanto sulle radici angioine della famiglia di Gahmuret ? Persino a proposito di suo figlio Feirefiz, “Bianco-Nero”, si trova una inusuale insistenza su questo casato che non trova alcuna giustificazione in una, d’altronde molto vaga, eventuale sua influenza e forza politica nei territori imperiali nei quali si muoveva Wolfram. L’importanza storica degli Angioini non può essere misconosciuta. La più antica insegna araldica del casato era una pantera. Il nonno di Enrico II, Folco d’Anjou, fu uno dei primi cavalieri templari e amico del fondatore dell’Ordine Ugo de Payns, e addirittura nel 1131 divenne re di Gerusalemme. Il figlio Goffredo sposò Matilde, l’unica erede del re d’Inghilterra, un matrimonio dalle conseguenze fatidiche che dopo una serie interminabile di guerre dinastiche portò al trono il giovane Enrico II. Con una intuizione straordinaria che affondava le proprie ragioni nelle tradizioni più arcaiche del suo regno, Enrico si sposò con la potentissima Eleonora d’Aquitania e favorì una forma di cultura che s’incentrava sulla sintesi del patrimonio spirituale antico-celtico, con quegli aspetti delle dottrine cristiane che affondavano le proprie radici in una esperienza mistico-visionaria, sino a fare emergere tutta una serie di scritti fortemente pervasi di un simbolismo che nell’opera di Chrétien de Troyes trovò il modo più adeguato per esprimersi.

E tuttavia l’insistenza di Wolfram sul ruolo degli Anschouwe può essere spiegata anche senza il ricorso alla storia dello straordinario casato degli Anjou, ma restando all’interno della stessa ambientazione dottrinale del Parzival e al simbolismo che lo permea. In una memoria che ha perduto pochissimo della sua importanza nonostante il tempo trascorso, Bodo Mergell faceva notare che nel Parzival il termine anschouwe, pur essendo con ogni evidenza costruito sul francese Anjou, non indica sempre il casato francese. Seguendo anche in questo caso la particolare tecnica di strutturazione dei fonemi e del simbolismo delle parole a lui così congeniale, anschouwe appare costruito sul termine das schouwen o beschouwen, “visione”, che si riferirebbe non ad un casato, ma più coerentemente con la struttura complessiva del Parzival, alla “visione” del Graal. Lo stesso musulmano Feirefiz, pur fratello di Parzival ed erede come lui di Gahmuret, per non aver ricevuto il battesimo manca della necessaria “grazia” e perciò non può “vedere” il Graal. Giocando sull’ambivalenza simbolica del termine, Gahmuret l’Anschouwe, il capostipite della dinastia che custodirà il Graal, diventa contemporaneamente l’“Angioino” e “Colui che vede il Graal”, “il Contemplativo del Graal”.

E tuttavia l’insistenza di Wolfram sul ruolo degli Anschouwe può essere spiegata anche senza il ricorso alla storia dello straordinario casato degli Anjou, ma restando all’interno della stessa ambientazione dottrinale del Parzival e al simbolismo che lo permea. In una memoria che ha perduto pochissimo della sua importanza nonostante il tempo trascorso, Bodo Mergell faceva notare che nel Parzival il termine anschouwe, pur essendo con ogni evidenza costruito sul francese Anjou, non indica sempre il casato francese. Seguendo anche in questo caso la particolare tecnica di strutturazione dei fonemi e del simbolismo delle parole a lui così congeniale, anschouwe appare costruito sul termine das schouwen o beschouwen, “visione”, che si riferirebbe non ad un casato, ma più coerentemente con la struttura complessiva del Parzival, alla “visione” del Graal. Lo stesso musulmano Feirefiz, pur fratello di Parzival ed erede come lui di Gahmuret, per non aver ricevuto il battesimo manca della necessaria “grazia” e perciò non può “vedere” il Graal. Giocando sull’ambivalenza simbolica del termine, Gahmuret l’Anschouwe, il capostipite della dinastia che custodirà il Graal, diventa contemporaneamente l’“Angioino” e “Colui che vede il Graal”, “il Contemplativo del Graal”.

Tutto il romanzo è percorso dalla presenza del Graal che giustifica la “cerca” e dà significato all’intera impostazione del racconto. In V, 232 Wolfram descrive il Corteo del Graal sostanzialmente ordinato ancora attorno allo stesso schema del Perceval, ma aggiunge una serie di particolari assenti in Chrétien. Il Graal non è più un piatto, un gradalis, un vaso o una coppa, ma una straordinaria “pietra preziosa” (“di un tipo purissimo” dice Wolfram) che viene chiamata lapsit exillis (Parzival, IX, 469) assimilabile sotto tutti gli aspetti al Cintamani buddhista, “il gioiello perfetto”, “la pietra pura” o “splendente” dalla quale si riverbera la Luce spirituale, l’”Aureola di Gloria” che risplende dalla persona dei Buddha e da quella di ogni Sovrano Universale. Nelle iconografie il Cintamani appare spesso coronato da una triplice fiamma radiante che ha il potere di preservare da tutti i mali e di esaudire ogni desiderio. È lo stesso “Splendore di Luce” emanato dalla “Roccia di smeraldo” (=Sakhra) che nelle dottrine islamiche sfolgora sulla sommità di Qâf, la montagna cosmica identica in tutto a Munsalvaetsche.

Nei settantacinque manoscritti che hanno conservato l’opera di Wolfram a volte si trovano altre formulazioni grafiche, come lapis exilis oppure lapis exilix; nello stesso Jüngerer Titurel di Albrecht von Scharfenberg, che si dispiega sull’idea ispiratrice centrale di Wolfram e ne sviluppa le implicazioni più “orientaleggianti”, si trova jaspis exilis, jaspis und silix, “diaspro e silice”. René Nelli privilegiava la dizione lapis exillis dalla quale sarebbe derivato poi lapis e coelis (“pietra caduta dal cielo”), un’espressione comunque facilmente derivabile dalle spiegazioni dottrinali sviluppate da Wolfram nel suo racconto. La tesi di René Nelli ha il pregio di mostrare la sostanziale “macchinosità” dell’ipotesi di un lapsit exillis ottenuto per contrazione fonetica di un lapis lapsus ex coelis cui pensavano gli studiosi francesi d’inizio Novecento, o del più recente e troppo elaborato lapis lapsus in terram ex illis stellis di Bodo Mergell.

Nei settantacinque manoscritti che hanno conservato l’opera di Wolfram a volte si trovano altre formulazioni grafiche, come lapis exilis oppure lapis exilix; nello stesso Jüngerer Titurel di Albrecht von Scharfenberg, che si dispiega sull’idea ispiratrice centrale di Wolfram e ne sviluppa le implicazioni più “orientaleggianti”, si trova jaspis exilis, jaspis und silix, “diaspro e silice”. René Nelli privilegiava la dizione lapis exillis dalla quale sarebbe derivato poi lapis e coelis (“pietra caduta dal cielo”), un’espressione comunque facilmente derivabile dalle spiegazioni dottrinali sviluppate da Wolfram nel suo racconto. La tesi di René Nelli ha il pregio di mostrare la sostanziale “macchinosità” dell’ipotesi di un lapsit exillis ottenuto per contrazione fonetica di un lapis lapsus ex coelis cui pensavano gli studiosi francesi d’inizio Novecento, o del più recente e troppo elaborato lapis lapsus in terram ex illis stellis di Bodo Mergell.

Un lapsit exillis, un lapis e coelis, una “pietra caduta dal cielo”, stabilisce un rapporto fra il cielo e la terra, introduce una scintilla di “sacralità celeste” nel mondo, è il veicolo di una rivelazione, una ierofania che trasforma lo stesso luogo in cui cade in uno spazio sacro totalmente differente da ogni altro esistente al mondo, diventa la “sede” di un’attività rituale intesa a “fare parlare” la pietra sacra, ad interrogarla sui misteri del cosmo. D’altronde, cos’altro è l’oracolo se non una modalità per stabilire un rapporto con i ritmi del cosmo, “farlo parlare” e ordinare su quei ritmi ogni pur insignificante aspetto della vita umana? La dimensione oracolare del lapsit exillis è evidente e rimanda ad un mondo arcaico, ai ritmi di un’umanità primordiale. Le scritte che appaiono sulla pietra e spariscono appena comprese ricordano con stupefacente somiglianza i riti oracolari delle tradizioni più antiche dell’umanità, quando il Verbum Dei si riteneva potesse essere compreso nei simboli che coprivano il cosmo e nei segni con i quali si svelava agli uomini. Anche le sue “virtù” mostrano aspetti arcaici. La sua luce folgorante, l’inesauribile capacità di fornire cibo e bevande ai convenuti, il dono di non fare invecchiare “le ossa e la carne”, di restituire la giovinezza, i poteri di guarigione, le connessioni con i ritmi astrologici, la stessa sapienza oracolare, indirizzano verso quella “radice e coronamento di ciò che si anela in Paradiso” che secondo Wolfram contrassegna gli aspetti fondamentali del Graal.

Ogni Venerdì Santo una colomba depone un’Ostia bianca sul Graal e lo rende capace di elargire le sue virtù “eucaristiche”: lo Spirito Celeste dà “ai cavalieri quanto vive di selvaggio, vola, corra o nuoti, sotto il cielo. La virtù del Graal dà vita a tutta la Compagnia dei Cavalieri” (IX, 470). Come si vede, il lapsit exillis non è solamente il sacro Oggetto che in una pura contemplazione stacca l’eletto dal mondo e lo “assorbe” in uno splendore senza fine. Nella prospettiva di Wolfram la dimensione contemplativa e la sua “grazia agente” appaiono in una specie di sintesi principiale, il Graal “ritorna nel mondo”, “ridiscende nel creato”, esercita i suoi poteri, alimenta la vita cosmica con una specie di “azione immobile” all’interno del mistico Castello, a Munsalvaetsche, in medio mundi.

Ogni Venerdì Santo una colomba depone un’Ostia bianca sul Graal e lo rende capace di elargire le sue virtù “eucaristiche”: lo Spirito Celeste dà “ai cavalieri quanto vive di selvaggio, vola, corra o nuoti, sotto il cielo. La virtù del Graal dà vita a tutta la Compagnia dei Cavalieri” (IX, 470). Come si vede, il lapsit exillis non è solamente il sacro Oggetto che in una pura contemplazione stacca l’eletto dal mondo e lo “assorbe” in uno splendore senza fine. Nella prospettiva di Wolfram la dimensione contemplativa e la sua “grazia agente” appaiono in una specie di sintesi principiale, il Graal “ritorna nel mondo”, “ridiscende nel creato”, esercita i suoi poteri, alimenta la vita cosmica con una specie di “azione immobile” all’interno del mistico Castello, a Munsalvaetsche, in medio mundi.

Il Graal è custodito da cavalieri che vengono mantenuti sempre giovani, in pienezza di salute e nutriti solo e soltanto dalla sua luce radiante: “A Munsalvaetsche, presso il Graal, si trova una schiera di cavalieri armati. Questi Templari spesso cavalcano lontano in cerca di avventure. Sia che acquistino gloria o danno, compiono le loro gesta come espiazione dei loro peccati. Questa Compagnia è bene armata. Ma voglio dirvi come si nutrono: vivono di una pietra di tipo purissimo. Se non ne avete mai sentito parlare vi dico il nome: lapsit exillis si chiama. […]. La pietra è anche chiamata Graal” (IX, 469). Più avanti (IX, 471), Wolfram aggiunge che questa straordinaria “pietra sempre pura”, questo “gioiello splendente” dopo la caduta degli angeli ribelli è affidata “a coloro che furono destinati da Dio, ai quali mandò un angelo. Ecco cos’è il Graal”.

Cerchiamo di capire i molteplici elementi che emergono da questo conosciutissimo brano:

- viene stabilito un rapporto fra il Graal e Munsalvaetsche, la “Montagna originaria” immagine del Paradiso terrestre;

- Munsalvaetsche è custodita da una Compagnia di cavalieri;

- questi cavalieri vengono chiamati Templaisen,“Templari”; spesso questi cavalieri-templari vanno in cerca di avventure;

- la gloria che ne deriva o l’eventuale sconfitta costituisce una forma di “espiazione” di colpe;

- i cavalieri sono “bene armati” e contemporaneamente sono “nutriti” dalla luce della “pietra splendente” che essi sono chiamati a custodire e che dà significato alla loro vita;

- Dio ha inviato ai cavalieri del Graal un angelo la cui funzione “conoscitiva” e “selettiva” rende intellegibile la loro condizione di “custodi eletti”.

Come si vede, Wolfram stabilisce un legame strettissimo da un lato fra il Graal, il Paradiso perduto, una Compagnia di cavalieri i cui combattimenti vengono presentati come offerte sacrificali, e dall’altro con la duplice dimensione del loro status, l’essere “bene armati” e il vivere “nutriti” perpetuamente dal lapsit exillis, dal Graal. Non solo, ma Wolfram aggiunge che a questa schiera di cavalieri custodi del Graal non si accede per un qualsiasi merito “umano” che, anzi, sembra costituire un limite insuperabile, ma quando “sulla superficie della Pietra appare una scritta che indica il nome e la schiatta di colui che farà il viaggio fortunato, fanciullo o ragazzo; nessuno cancella la scritta perché subito scompare” (IX, 470). Questa “pietra caduta dal cielo” come i meteoriti dei tempi primordiali è carica di sacralità celeste, perciò è anche una “pietra parlante” capace di indicare il nome degli Eletti, di rivelarne il ruolo nella storia, di nutrirli con la propria luce radiante e di elargire l’Ostia santa portata dalla Colomba. La sua ricchezza simbolica è evidente e sottolinea l’esistenza di una specie di confraternita di Custodi del Graal dagli attributi assolutamente non comparabili con l’etica individualistica dei cavalieri di quel tempo.

Il rapporto stabilito fra i membri di questa straordinaria confraternita nella quale viene assorbita la loro individualità in una sorta di “funzione collettiva”, lo stesso loro status di cavalieri “sempre in guardia”, sono aspetti che riconducono alla corte di re Arthur e ai cavalieri della Tavola Rotonda e ne fanno una specie di suo equivalente simbolico. Anche qui, una esigua consorteria di Eletti va in cerca del Graal, affronta prove estenuanti, riesce finalmente a trovarlo e considera un privilegio la sua custodia. Non tutti i nomi di questi cavalieri sono stati preservati. Oltre Parzival e Galahad, i puri contemplativi del Graal, e ser Lancillotto del Lago, la cui personalità presenta caratteri molto vari con le sue attribuzioni derivate da un complesso mitologico arcaico assai diversificato, troviamo un gruppo di personaggi veramente particolari. Keu, il siniscalco del re, è chiaramente una trasposizione del personaggio di Kai del racconto gallese Kulhwch e Olwen, dove appare con alcuni tipici poteri sciamanici: respira sott’acqua per “nove notti e nove giorni” e, come una particolare classe di asceti dell’India vedica che grazie alle loro tecniche yoghiche erano in grado di evocare il tapas (=calore interiore; cfr. lat. tepor), il “calore naturale” emanato dal corpo di Keu asciuga l’acqua, riscalda i compagni e può trasformare il proprio corpo sino a farlo crescere indefinitamente. Girflet, corrisponde al gallese Gilvaethwy, il fratello di un mago e figlio di una dèa; la sua figura appartiene ad una dimensione non umana, scaturisce dal mondo intermedio degli incantatori e delle “fate”. La leggenda collega sempre Yder di Northumbria con i cervi e gli orsi; lo stesso famoso Yvain, figlio di Uryen, può contare su uno stormo di corvi [il simbolo della casta guerriera] che corre sempre in suo aiuto. Infine Galvano, riadattazione del Gwalchmai del Kulhwch e Olwen, ha il nome composto su gwen, “bianco” e gwalc’h, “falcone”, perciò si chiama “Falcone bianco”. I poteri attribuiti ad alcuni di questi personaggi sul proprio corpo, sugli elementi, su animali caratteristici come l’orso, il cervo, il corvo, il falcone, dei quali sono patroni o assumono il nome, ci portano nel mondo dei guerrieri antico-celtici, evidenziano simboli correnti nelle confraternite dei guerrieri primordiali prima della conversione della Celtide al Cristianesimo, quei simboli che sembrano indirizzare verso l’armonizzazione di poteri sciamanici, forza guerriera, magia e sacralità.

Il ciclo irlandese della provincia di Leinster che racconta le gesta del re Finn e della consorteria degli arcaici guerrieri Fiana, sembra costituire lo sfondo rituale e la forma mitologica che sostanzia questi aspetti della saga arthuriana. Il vero nome di Finn, re e guida di questa consorteria di guerrieri-predoni, è Demné, “il Daino”, suo figlio Oisin è “il Cerbiatto”, suo nipote Oscar è “il Cervo”, mentre la stessa moglie di Finn, la figlia del fabbro-sciamano Lochan dal quale l’eroe riceve le straordinarie armi che lo rendono invincibile, si dice fosse stata trasformata da un druido in una cerva. I Fiana erano straordinari guerrieri-cervi che cacciavano e vivevano una vita semi-nomade. Avevano il compito di sorvegliare le entrate delle case e dei villaggi ed erano persino incaricati di riscuotere le imposte. In estate si trasformavano in feroci cacciatori-guerrieri e andavano a scovare i malfattori, i briganti, i trasgressori delle leggi che regolavano la vita sociale. Il simbolo del cervo che li caratterizza, la loro azione sociale e il ruolo di custodia li rendono simili a quel tipo di consorteria di guerrieri sacri diffusi in tutta l’enorme area geografica coperta dalle invasioni indoeuropee, ed ha lasciato consistenti tracce archeologiche persino nei territori del Nord Europa, nell’area che ha conservato le vestigia e i simboli della preistorica “civiltà della renna” del periodo magdéleniano. Esattamente come i loro confratelli di altre culture, i membri di questi gruppi erano usi indossare maschere di cervo durante le processioni rituali e coprivano un ruolo, ad un tempo sacro e “sociale”.

Il ciclo irlandese della provincia di Leinster che racconta le gesta del re Finn e della consorteria degli arcaici guerrieri Fiana, sembra costituire lo sfondo rituale e la forma mitologica che sostanzia questi aspetti della saga arthuriana. Il vero nome di Finn, re e guida di questa consorteria di guerrieri-predoni, è Demné, “il Daino”, suo figlio Oisin è “il Cerbiatto”, suo nipote Oscar è “il Cervo”, mentre la stessa moglie di Finn, la figlia del fabbro-sciamano Lochan dal quale l’eroe riceve le straordinarie armi che lo rendono invincibile, si dice fosse stata trasformata da un druido in una cerva. I Fiana erano straordinari guerrieri-cervi che cacciavano e vivevano una vita semi-nomade. Avevano il compito di sorvegliare le entrate delle case e dei villaggi ed erano persino incaricati di riscuotere le imposte. In estate si trasformavano in feroci cacciatori-guerrieri e andavano a scovare i malfattori, i briganti, i trasgressori delle leggi che regolavano la vita sociale. Il simbolo del cervo che li caratterizza, la loro azione sociale e il ruolo di custodia li rendono simili a quel tipo di consorteria di guerrieri sacri diffusi in tutta l’enorme area geografica coperta dalle invasioni indoeuropee, ed ha lasciato consistenti tracce archeologiche persino nei territori del Nord Europa, nell’area che ha conservato le vestigia e i simboli della preistorica “civiltà della renna” del periodo magdéleniano. Esattamente come i loro confratelli di altre culture, i membri di questi gruppi erano usi indossare maschere di cervo durante le processioni rituali e coprivano un ruolo, ad un tempo sacro e “sociale”.

La preistoria, i miti irlandesi e la saga graalica sembrano indicarci un unico filo che lega i più antichi guerrieri irlandesi, i cavalieri di Arthur e i Custodi del Graal di Wolfram.

Esattamente dopo la prima metà del suo romanzo, all’inizio della seconda parte, quando Parzival riesce ad accostarsi al saggio eremita Trevrizent, vero e proprio erede degli asceti, dei monaci e degli eremiti dell’Irlanda celtica, e riceve una serie d’insegnamenti che finalmente lo avviano verso la comprensione della “cerca” e del vero significato del Graal, con apparente ovvietà Wolfram dà per ben due volte di seguito ad un cavaliere l’appellativo di Templaise von Munsalvaetsche, “Templare del Monte Selvaggio” (IX, 445). Subito dopo (IX, 446) si accenna ad “una schiera dei cavalieri di Munsalvaetsche” la cui formulazione è congegnata in modo da identificare “naturalmente” questi cavalieri con i Templari dei capoversi appena precedenti. Segue il celebre passo (IX, 469) che parla del Graal e del lapsit exillis. Qui la schiera di cavalieri armati che va in cerca di avventure sono sic et simpliciter i Templari e la formulazione espressiva non ammette dubbi: “die selben Templaise”. Il termine ritorna in XVI, 818. Al momento del battesimo di Feirefiz sul lapsit exillis appare una scritta che identifica ancora i cavalieri del Graal con i Templari: ”Il Templare sul quale si posa la mano di Dio per farlo signore di una gente straniera, non deve permettere domande sul nome o sulla sua schiatta. Deve aiutare quella gente”[…]“I cavalieri del Graal non volevano che si ponessero loro domande”.

La prima notazione da fare è che l’appellativo di “templari” dato ai cavalieri del Graal emerge senza nessuna motivazione narrativa, senza nessun ordinamento preventivo del racconto e senza alcun riferimento precedente ad un eventuale tempio, chiesa o monastero, qui assolutamente inesistenti. La stessa ambientazione complessiva che privilegia la presenza di un eremita, esclude l’eventuale richiamo ad un tempio o ad una comunità di contemplativi e tutto il contesto essenzialmente cavalleresco richiederebbe, piuttosto, la presenza di un castello. Il particolare appellativo, pur usato con molta parsimonia, non è certo secondario e riprende lo strano modo di Wolfram di comporre le parole e di specificare il loro significato simbolico. Il secondo aspetto che emerge con chiarezza è l’accostamento dei Templari assimilati ai Cavalieri del Graal con il Munsalvaetsche. Ne scaturisce la delineazione di una precisa funzione: i Templari sono i custodi del “Monte Selvaggio” e sono “nutriti” dalla luce radiante che si effonde dal lapsit exillis. Il terzo elemento che emerge in questi brevi cenni è l’assimilazione dei “templari” con i Cavalieri del Graal fatta derivare direttamente “dalla mano di Dio”. Quando, infatti, sul Graal appare la solita scritta “oracolare” viene detto che è lo stesso Dio a stabilire la sovranità di un determinato cavaliere templare su una “gente straniera”.

La prima notazione da fare è che l’appellativo di “templari” dato ai cavalieri del Graal emerge senza nessuna motivazione narrativa, senza nessun ordinamento preventivo del racconto e senza alcun riferimento precedente ad un eventuale tempio, chiesa o monastero, qui assolutamente inesistenti. La stessa ambientazione complessiva che privilegia la presenza di un eremita, esclude l’eventuale richiamo ad un tempio o ad una comunità di contemplativi e tutto il contesto essenzialmente cavalleresco richiederebbe, piuttosto, la presenza di un castello. Il particolare appellativo, pur usato con molta parsimonia, non è certo secondario e riprende lo strano modo di Wolfram di comporre le parole e di specificare il loro significato simbolico. Il secondo aspetto che emerge con chiarezza è l’accostamento dei Templari assimilati ai Cavalieri del Graal con il Munsalvaetsche. Ne scaturisce la delineazione di una precisa funzione: i Templari sono i custodi del “Monte Selvaggio” e sono “nutriti” dalla luce radiante che si effonde dal lapsit exillis. Il terzo elemento che emerge in questi brevi cenni è l’assimilazione dei “templari” con i Cavalieri del Graal fatta derivare direttamente “dalla mano di Dio”. Quando, infatti, sul Graal appare la solita scritta “oracolare” viene detto che è lo stesso Dio a stabilire la sovranità di un determinato cavaliere templare su una “gente straniera”.

L’assimilazione dei Templari ai Cavalieri del Graal comporta l’assunzione di un preciso compito: con la custodia di Munsalvaetsche, “la Montagna originaria” sulla quale troneggia il Graal, i Templari diventano i custodi del “Centro sacro” che regge il cosmo. E’ qui che il Graal li nutre, li guarisce, garantisce la loro eterna giovinezza e di volta in volta designa qualcuno di loro ad assumere funzioni sovrane quando le circostanze della storia lo richiedono. Per usare il simbolismo di Wolfram, quando occorre i Cavalieri del Graal “escono in cerca di avventure”, ossia intervengono nello svolgimento delle vicende umane e offrono al Sovrano Celeste gli eventuali insuccessi o le vittorie come una specie di “offerta sacrificale” della loro insufficienza nell’adempimento del compito affidato. Si tratta dell’indicazione piuttosto precisa di un particolarissimo “rituale di espiazione” comprensibile pienamente solo nell’ambito di una dottrina assimilabile a quella ecclesiale della “Comunione dei Santi”, che qui sostanzia la strutturazione a Confraternita di questi cavalieri e dà significato anche al chiaro intento di Wolfram di statuire, pel tramite di questi Templari, forme di relazione con le tre tradizioni spirituali (celtica, cristiana e islamica) che hanno trovato una loro espressione simbolica, una specie di “armonia unitaria”, nel suo Parzival.

A causa della ripetuta menzione dei Templari nei suoi scritti, delle modalità con le quali vengono menzionati questi straordinari cavalieri-monaci che hanno percorso i due secoli “centrali” del Medio Evo, del ruolo da essi coperto accanto al Graal, al Castello del Graal e a Munsalvaetsche, si è pensato che Wolfram fosse un membro dell’Ordine e che nel suo poema si trovino esposte alcune delle dottrine che i Templari consideravano essenziali per spiegare il significato della loro particolare funzione spirituale. Il suo statuto di cavaliere e cantore che vagava di corte in corte non può essere considerato un vero ostacolo alla sua eventuale ammissione a questo misterioso Ordine: anche Folco d’Anjou fu un templare, sposato e poi diventato re. Pur non possedendo attestazioni nette di una simile possibilità, l’uso di una terminologia tecnica non certo usuale negli scrittori del tempo che con precisione delinea la funzione dei Templari, e il costante richiamo ad enigmatici “maestri” che lo avrebbero ispirato, costringe a dare giusto rilievo alle ripetute attestazioni di Wolfram che il Parzival non è una sua creazione assolutamente personale o originale, tesa ad arricchire il gaudio di questa o quella corte, ma affonda le proprie ragioni in una speciale tradizione che nella saga del Graal ha trovato il veicolo più adatto per svelare una complessa simbologia spirituale.

Sembrerebbe impossibile riuscire a provare con esattezza se i Templaisen di Wolfram siano effettivamente i cavalieri-monaci dell’Ordine del Tempio. Qualcuno ha pensato persino che la loro menzione nel Parzival possa essere la semplice eco di un Ordine che spesso assumeva contorni leggendari; altri, che si sia voluto evidenziare nettamente la natura profonda dei rapporti dell’Ordine del Tempio con il Graal e con il Paradiso perduto, il “Centro del mondo”. È possibile che queste ipotesi siano vicine alla realtà. Il rilievo assunto dall’assimilazione dei Templaisen con i “Cavalieri del Graal” nella seconda parte del romanzo, dopo le indicazioni sul ruolo centrale di Gahmuret e dell’Islam, è troppo circostanziato, attento ai particolari e alle funzioni simboliche perché si possa pensare ad una semplice casualità. Pur in un linguaggio criptico, come se i vari simboli dovessero essere compresi solamente da una esigua èlite, l’assimilazione fatta da Wolfram fra i Cavalieri del Graal e i Templari sembra indicare una direzione precisa, un enigmatico legame fra la realtà storica dei Cavalieri-monaci e il Graal.

Così, attorno allo sfondo dottrinale incentrato nella “cerca” di una misteriosa Pietra sacra “caduta dal cielo”, a poco a poco emerge il simbolo di un “Luogo sacro” dal quale s’irradia la Luce del Graal, un specie di “Tabernacolo radiante” posto in medio mundi e protetto da una speciale Confraternita di Cavalieri. E d’altronde, la stessa espressione Templaisen von Munsalvaetsche non è l’equivalente esatto dell’attribuzione più famosa dei Templari, “Custodi della Terra Santa” ?

* * *

Articolo pubblicato con la cortese concessione della Redazione di “Arthos” e dell’Autore.

Nuccio D'Anna

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : moyen âge, allemagne, littérature, littérature allemande, littérature médiévale, lettres allemandes, lettres, lettres médiévales, wolfram von eschenbach |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 18 septembre 2011

Céline - Hergé, le théorème du perroquet

Céline - Hergé, le théorème du perroquet

par David ALLIOT (2005)

Ex: http://lepetitcelinien.com/

Dans son dernier ouvrage intitulé Céline, Hergé et l’affaire Haddock ¹, Émile Brami, nous expose sa théorie sur les origines céliniennes des célèbres jurons du non moins célèbre capitaine. Même s’il ne dispose pas de "preuves" en tant que telles, l’on ne peut être que troublé par ces faisceaux qui lorgnent tous dans la même direction. En attendant l’hypothétique découverte d’une lettre entre les deux susnommés ou d’un exemplaire de Bagatelles pour un massacre dans la bibliothèque Hergé, nous en sommes malheureusement réduits aux conjectures. Pendant la rédaction de son livre, j'indiquais à Émile Brami quelques hypothèses susceptibles de conforter sa thèse. Par exemple, est-ce que le professeur Tournesol et Courtial de Pereires partagent le même géniteur ? etc. C'est un heureux hasard qui me fit découvrir un autre point commun entre le dessinateur de Bruxelles et l'ermite de Meudon. Hasard d'autant plus intéressant, qu'à l'instar de Bagatelles pour un massacre, les dates concordent. Si les premières recherches furent encourageantes, l'on en est également réduit aux hypothèses, faute de preuve matérielle.

Dans son dernier ouvrage intitulé Céline, Hergé et l’affaire Haddock ¹, Émile Brami, nous expose sa théorie sur les origines céliniennes des célèbres jurons du non moins célèbre capitaine. Même s’il ne dispose pas de "preuves" en tant que telles, l’on ne peut être que troublé par ces faisceaux qui lorgnent tous dans la même direction. En attendant l’hypothétique découverte d’une lettre entre les deux susnommés ou d’un exemplaire de Bagatelles pour un massacre dans la bibliothèque Hergé, nous en sommes malheureusement réduits aux conjectures. Pendant la rédaction de son livre, j'indiquais à Émile Brami quelques hypothèses susceptibles de conforter sa thèse. Par exemple, est-ce que le professeur Tournesol et Courtial de Pereires partagent le même géniteur ? etc. C'est un heureux hasard qui me fit découvrir un autre point commun entre le dessinateur de Bruxelles et l'ermite de Meudon. Hasard d'autant plus intéressant, qu'à l'instar de Bagatelles pour un massacre, les dates concordent. Si les premières recherches furent encourageantes, l'on en est également réduit aux hypothèses, faute de preuve matérielle.

Grâce aux nombreuses publications dont Hergé est l'objet, l'on en sait beaucoup plus sur la genèse de son œuvre. Grâce aux travaux de Benoît Mouchard ², on connaît maintenant le rôle primordial qu’a joué Jacques Van Melkebeke dans les apports "littéraires" de Tintin. Mais surtout les travaux d'Émile Brami ont permis, pour la première fois, de faire un lien entre les deux, et de replacer la naissance du capitaine Haddock et la publication de Bagatelles pour un massacre dans une perspective chronologique et culturelle cohérente. Néanmoins, il n'est pas impossible que d'autres liens entre Céline et Hergé figurent dans certains albums postérieurs du Crabe aux Pinces d’or.

Le lien le plus "parlant", si l'on ose dire, entre le dessinateur belge et l'imprécateur antisémite est un perroquet, héros bien involontaire des Bijoux de la Castafiore.

Lorsque Hergé entame la rédaction de cet album au début des années 1960, il choisit pour la première (et seule fois) un album intimiste. Coincé entre Tintin au Tibet et Vol 714 pour Sydney, Les Bijoux de la Castafiore a pour cadre exclusif le château de Moulinsart. Tintin, Milou, Tournesol et le capitaine Haddock ne partent pas à l'aventure dans une contrée lointaine, c'est l'aventure qui débarque (en masse) chez eux. Et visiblement, l'arrivée de la Castafiore perturbe le train-train habituel de nos héros. Les Bijoux de la Castafiore offre également l'intérêt d'être un album très "lourd" du point de vue autobiographique, avec des rapports ambigus entre la Castafiore et Haddock (projets de mariage), des dialogues emplis de sous-entendus ("Ciel mes bijoux") et, au final, bien peu de rebondissements et d’action. Néanmoins, au milieu de ce joyeux bazar, émerge un élément comique qui va mener la vie dure au vieux capitaine. C’est Coco le "des îles", qui partage de nombreux points communs avec Toto, le non moins célèbre perroquet de Meudon.

|

| Illustration de David Brami |

L'autre élément qui accrédite l'hypothèse du perroquet est chronologique. La conception des Bijoux de la Castafiore et la mort de Céline sont concomitantes. Alors qu'Hergé est en train de construire l'album, Céline décède, en juillet 1961. Si peu de journaux ont fait grand cas de cette nouvelle, Paris-Match évoquera, dans un numéro en juillet et un autre, en septembre 1961, la disparition de Céline (et d’Hemingway, mort le même jour). Largement illustrés de photographies, deux thèmes récurrents se retrouvent d’un numéro l’autre: Céline et son perroquet Toto. Dans son numéro de juin, Paris Match s’extasie devant la table de travail de Céline sur laquelle veille le perroquet, dernier témoin (presque muet) de la rédaction de Rigodon... Dans le numéro de septembre, l'on peut voir la photographie de Céline dans son canapé, avec Toto, ultime compagnon de solitude.

Grâce aux biographes d'Hergé, on sait que ce dernier ne lisait pour ainsi dire jamais de livres. Quand il s'agissait de ses albums, il demandait à ses collaborateurs de préparer une documentation importante afin qu'il n'ait plus qu'à se concentrer sur le scénario et le dessin. Éventuellement, il lui arrivait de rencontrer des personnes idoines qu'il interrogeait sur un sujet qui toucherait de près ou de loin un aspect de ses futurs albums (Bernard Heuvelmans, pour le Yéti, par exemple.). Si Hergé lisait peu de livres, on sait, par contre, qu'il était friand de magazines (5) et qu’il puisait une partie de son inspiration dans l’actualité du moment. La grande question est : a-t-il eu dans les mains les numéros de Paris-Match relatant la mort de Céline ? C’est hautement probable car l’on sait qu’il lisait très régulièrement ce magazine. S’en est-il servi pour Les Bijoux de la Castafiore ? Pour cela, il suffit de comparer la photographie de Céline dans son canapé à Meudon, à celle de Haddock dans son fauteuil, à Moulinsart. La comparaison est probante.

En voyant ainsi Céline et son perroquet dans Paris-Match, Hergé s'est-il souvenu des conversations qu'il avait eu autrefois à ce sujet avec Melkebeke ou Robert Poulet ? A-t-il admiré autrefois Céline, non pas forcément comme écrivain, mais comme "éologue" antisémite ? A-t-il décidé de faire un petit clin d'œil discret au disparu en reprenant son fidèle perroquet ? Malheureusement, il est encore impossible de répondre. Lentement, les éditions Moulinsart ouvrent les "archives Hergé" en publiant chaque année un important volume chronologique sur la genèse des différentes œuvres du dessinateur. À ce jour, ces publications courent jusqu’aux années 1943, et il faudra attendre un petit peu pour en savoir plus sur la genèse des Bijoux de la Castafiore et de son célèbre perroquet.

Reste néanmoins un élément troublant. Dans son livre, Le Monde d’Hergé (6), Benoît Peeters publie la planche qui annonce la publication des Bijoux de la Castafiore dans les prochaines livraisons du Journal de Tintin. Sur cette planche apparaissent tous les protagonistes du futur album, Tintin, Haddock, les Dupond(t)s, Tournesol, Nestor, la Castafiore, Irma, Milou, le chat, l'alouette, les romanichels, etc. Mais point de perroquet, qui pourtant a une place beaucoup plus importante que certains protagonistes précédemment cités. Hergé a-t-il rajouté Coco en catastrophe? Coco était-il prévu dans le scénario d'origine ? Pourquoi Hergé fait-il parler un perroquet qui ne le pouvait pas ? Erreur due à la précipitation ? Ou à une mauvaise documentation ? Est-ce la vision de Céline et de son compagnon à plumes qui ont influencé in extremis cette décision en cours de création ? Détail intéressant, dans ses derniers entretiens avec Benoît Peeters, Hergé avoue qu'il aime se laisser surprendre: " J’ai besoin d’être surpris par mes propres inventions. D’ailleurs, mes histoires se font toujours de cette manière. Je sais toujours d’où je pars, je sais à peu près où je veux arriver, mais le chemin que je vais prendre dépend de ma fantaisie du moment " (7). Coco est-il le fruit de cette "surprise" ? À ce jour, le mystère reste entier, mais peut-être que les publications futures nous éclaireront sur ce point. Il serait temps ! Mille sabords !

David ALLIOT

Article paru dans Le Bulletin célinien n°260 de janvier 2005,

Repris dans Le Petit Célinien n°1 du 20 avril 2009.

Emile Brami, Céline, Hergé et l'affaire Haddock, Ed. Ecriture, 2004.

Notes

1. Éditions Écriture. Les travaux d'Émile Brami sur Hergé et Céline ont été présentés au colloque de la Société d'Études céliniennes de juin 2004 à Budapest, et partiellement publiés par le magazine Lire de septembre 2004.