Bulletin célinien, n°410, septembre 2018

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

Céline et Joyce

Un débat sur la réédition des pamphlets

Clément Rosset et Céline

Maurice Lemaître et l’ “Association israélite pour la réconciliation des Français”

Un grand livre sur Roger Nimier

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

Bulletin célinien, n°410, septembre 2018

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

Céline et Joyce

Un débat sur la réédition des pamphlets

Clément Rosset et Céline

Maurice Lemaître et l’ “Association israélite pour la réconciliation des Français”

Un grand livre sur Roger Nimier

En arrière-plan de ce colloque : la polémique suscitée par le projet de réédition des pamphlets par les éditions Gallimard. Une table ronde réunissant diverses personnalités fut organisée en ouverture du colloque. Nous en rendons compte dans ce numéro. À l’exception notable de Philippe Roussin, directeur de recherches au CNRS, il faut noter que tous les spécialistes de Céline sont favorables à cette réédition. Hormis François Gibault, qui s’est fait durant un demi-siècle le porte-parole de l’ayant droit ³, observons que cela a toujours été le cas. Il y a plus de trente ans déjà, nous avons publié ici leurs appréciations 4. Dont celle de Henri Godard qui, contrairement à ce qui fut sous-entendu lors de cette table ronde, s’exprima dès le début de manière claire : « Plus l’audience des textes disponibles en librairie s’accroît, plus il devient anormal que les mêmes lecteurs n’aient accès qu’en bibliothèque ou au prix du commerce spécialisé, aux écrits qu’ils trouvent cités, interprétés et jugés dans des travaux critiques. »

18:59 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises, revue, marc laudelout |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

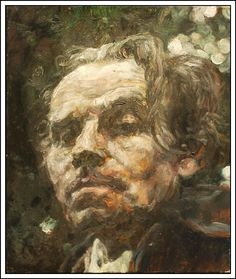

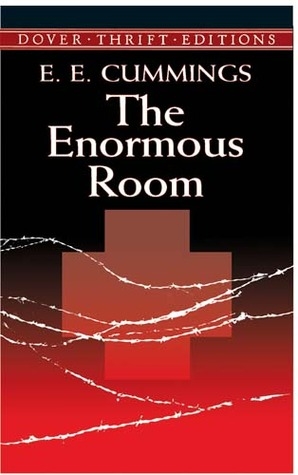

V. S. Naipaul

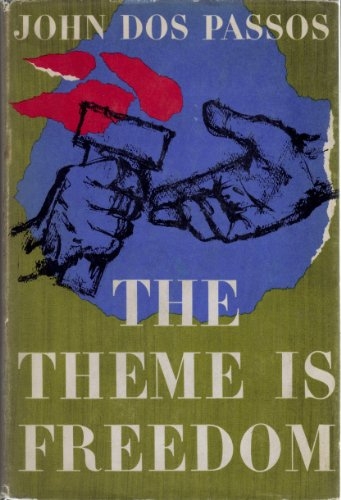

Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981

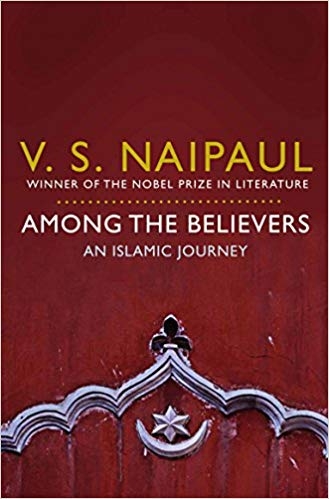

The further to the political Right one gets, the easier it is to connect with the mentality and ideas of those of a Hindu background while becoming increasingly alienated from the Bible’s Old Testament and its vicious cast of desert-dwelling thieves, murderers, perverts, and swindlers. One example of this phenomenon is the late V. S. Naipaul’s (1932–2018) look at one prickly Abrahamic faith of the desert: Islam, entitled Among the Believers (1981).

Naipaul had a unique background. He was of Hindu Indian origins and grew up in the British Empire’s West Indian colony of Trinidad and Tobago. Naipaul wrote darkly of his region of birth, stating, “History is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was created in the West Indies.”[1] [2] His gloomy take on the region is a bit inaccurate; the racially whiter places such as Cuba have produced societies of a sort of dynamism. Cubans did field a large mercenary force on behalf of the Soviet Union in Africa late in the Cold War, and the mostly white Costa Rica is a nice place to live. But Haiti is a super-ghetto of Africanism. In some cases, the West Indians can’t even give themselves away. At a time when the American people were enthusiastic for expansion, the US Senate bitterly opposed the Grant administration’s attempt to annex what is now the Dominican Republic. Who wants to take over Hispaniola’s problems?[2] [3] Naipaul’s prose is so good that he will be extensively quoted throughout this review.

Naipaul had a unique background. He was of Hindu Indian origins and grew up in the British Empire’s West Indian colony of Trinidad and Tobago. Naipaul wrote darkly of his region of birth, stating, “History is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was created in the West Indies.”[1] [2] His gloomy take on the region is a bit inaccurate; the racially whiter places such as Cuba have produced societies of a sort of dynamism. Cubans did field a large mercenary force on behalf of the Soviet Union in Africa late in the Cold War, and the mostly white Costa Rica is a nice place to live. But Haiti is a super-ghetto of Africanism. In some cases, the West Indians can’t even give themselves away. At a time when the American people were enthusiastic for expansion, the US Senate bitterly opposed the Grant administration’s attempt to annex what is now the Dominican Republic. Who wants to take over Hispaniola’s problems?[2] [3] Naipaul’s prose is so good that he will be extensively quoted throughout this review.

In Among the Believers, Naipaul takes a look at the nations where Islam dominates the culture but where the populations are not Arabs. He wrote this book in the immediate aftermath of the Iranian Revolution, so we are seeing what happens when a people with a rich heritage attempt to closely follow the religion of their alien Arab conquerors. What you get is a people at war with themselves, and a people who, to put it mildly, turn away from the light of reason. He can express this in civilizational terms as well as individually. For example, in highly readable prose, Naipaul writes of a Malay woman who courts a “born again” Muslim man. Before she got with him, the young lady danced, dived, and went camping, but afterwards she took to the hijab and the drab long gowns, “and her mind began correspondingly to dull.”[3] [4]

When one reads Naipaul’s work, one comes to appreciate Islam; not the sort of pretend appreciation that virtue-signaling liberals have right up until a group of fanatics run them over with a car and then knife them to death as they lie injured [5], but an appreciation of just how terribly the Islamic worldview impacts all of society. After reading this book, one can see that Islam is the following:

Quite possibly the most interesting part of this book is Naipaul’s account of the Arab conquest of what is now Pakistan, but which was then called the Sind. Starting around 634, the Muslim Arabs began attempting to conquer the region. They launched at least ten campaigns over seventy years; all were unsuccessful. However, the Arabs eventually won. During the time of the Arab menace, the people of the Sind were weakened by a prophecy of doom, and palace intrigue had weakened their political elite. The Sind people were also awed by the apparent unity and discipline of the Muslims. The common people surrendered in droves, and the Sind’s King was killed in an avoidable death, or glory battle.

For the people of the Sind and their Hindu/Buddhist culture, the Arab conquest was a disaster. “At Banbhore [13], a remote outpost of the earliest Arab empires, you walked on human bones.”[10] [14] However, the Pakistanis today cannot admit to themselves that they lost their traditional culture. The story of the Arab conquest is told in a work called the Chachnama. Naipaul argues that the Chachnama is like Bernal Díaz’s great work, The Conquest of New Spain, except for the fact that the Chachnama’s author was not a soldier in the campaign as was Bernal Díaz; it was written by a Persian scribe centuries after the event. Like all things in Islam, the insights offered by the Chachama are dull at best, and “The intervening five centuries [since the publication of the Chachama] have added no extra moral or historical sense to the Persian narrative, no wonder or compassion, no idea of what is cruel and what is not cruel, such as Bernal Díaz, the Spanish soldier, possesses.”[11] [15]

The arrival of Islam to the Sind is the disaster which keeps on giving. Pakistan’s economy [16] lags behind India’s, although India has a large population of low IQ, low-caste people. Pakistan also cannot produce world-class cultural works like India does. There is no Pakistani version of Bollywood. The best thing the Pakistani government can do is to provide exit visas for its people to go and work elsewhere, as well as advice on the immigration laws of receiving countries.

The arrival of Islam to the Sind is the disaster which keeps on giving. Pakistan’s economy [16] lags behind India’s, although India has a large population of low IQ, low-caste people. Pakistan also cannot produce world-class cultural works like India does. There is no Pakistani version of Bollywood. The best thing the Pakistani government can do is to provide exit visas for its people to go and work elsewhere, as well as advice on the immigration laws of receiving countries.

Perhaps because Naipaul is from the West Indies – a Third World region which has long touched the more dynamic societies of the white man – he is able to so accurately describe the disaster of Third World immigration, especially as it applies to Pakistan and its pitiable people. He is worth quoting at length:

The idea of the Muslim state as God had never converted into anything less exalted, had never converted into political or economic organization. Pakistan – a thousand miles long from the sea to the Himalayas, and with a population of more than seventy million – was a remittance economy. The property boom in Karachi was sustained in part by the remittances of overseas workers, and they were everywhere, legally and illegally. They were not only in Muslim countries – Arabia, the Gulf states, Libya; they were also in Canada and the United States and in many of the countries of Europe. The business was organized. Like accountants studying tax laws, the manpower-export experts of Pakistan studied the world’s immigration laws and competitively gambled with their emigrant battalions: visitor’s visas overstayable here (most European countries), dependents shippable there (England), student’s visas convertible there (Canada and the United States), political asylum to be asked for there (Austria and West Berlin), still no visas needed here, just below the Arctic Circle (Finland). They went by the planeload. Karachi airport was equipped for this emigrant traffic. Some got through; some were turned back.[12] [17]

Once they got there:

. . . the emigrants threw themselves on the mercies of civil-liberties organizations. They sought the protection of the laws of the countries where the planes had brought them. They or their representatives spoke correct words about the difference between poor countries and rich, South and North. They spoke of the crime of racial discrimination and the brotherhood of man. They appealed to the ideals of the alien civilizations whose virtue they denied at home.[13] [18]

Naipaul shows that Islam is a tremendous, though retarding, metapolitical force that works its way into all areas of human societies: the law, philosophy, medicine, and even city planning. He shows the power of its simple theology over less intelligent, Third World minds. He shows its dark, violent core. Once the virus of Islam infects a society, whatever higher culture that society had is destroyed. Islam’s ultimate endpoint is a world of barren desert dunes squabbled over by uncreative, violent fanatics. In short, Islam is so powerful because it is fortified by its own failures and contradictions rather than defeated by them.

Naipaul’s criticism of Islam has drawn its own critics, such as Salman Rushdie [19] and the late Edward Said [20], but in light of the Global War on Terror and the rapid descent of many Islamic lands into even deeper, darker forms of barbarism, they have been given extended life by the imported lights of the white man’s science and technology, and Naipaul has become something of a prophet.

In conclusion, from the perspective of the white man who believes in civilization, Islam must be resisted by all means. Furthermore, “civil rights” is a tool of white displacement. Dismantling “civil rights” agencies is critical. Of the greatest importance, though, is to break free of the tremendous sense of guilt and self-loathing in the Western world. As long as whites continue to worship Emmett Till, Martin Luther King, and the rest of the pantheon of non-white idols, the dull, slack society of Islam will punch above its weigh.

Don’t let your nation become one of those counted as among the Believers.

Notes

[1] [21] Patrick French, The World Is What It Is: The Authorized Biography of V. S. Naipaul (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), p. 203.

[2] [22] Unfortunately, the US did purchase the Danish Virgin Islands and capture Puerto Rico. The 2017 hurricane season was the scene of two vicious storms: one devastated Houston, Texas, which recovered rapidly. The other storm destroyed Puerto Rico, which took months to recover basics such as electricity.

[3] [23] Ibid., p. 302.

[4] [24] I’ve had to condense the prose here to generalize what Naipaul is saying about several Iranians during the Islamic Revolution. See p. 80 for the full quote in context.

[5] [25] Ibid., p. 15.

[6] [26] Ibid., p. 169.

[7] [27] Ibid., p. 12.

[8] [28] Ibid., p. 7.

[9] [29] Ibid., p. 124.

[10] [30] Ibid., p. 131.

[11] [31] Ibid., p. 133.

[12] [32] Ibid., p. 101.

[13] [33] Ibid.

01:00 Publié dans Islam, Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : v. s. naipaul, naipaul, littérature, littérature anglaise, lettres, lettres anglaises, islam, livre, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

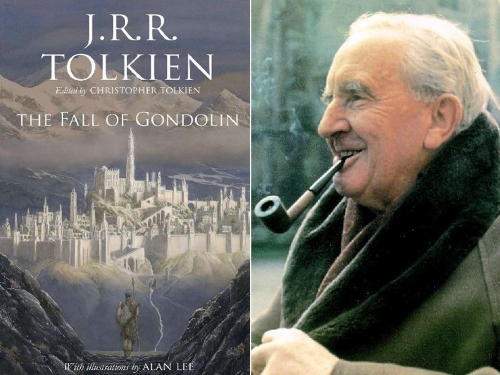

J. R. R. Tolkien (Christopher Tolkien, ed.)

The Fall of Gondolin

New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018

The Fall of Gondolin is Tolkien’s final posthumous publication and the third of his “Great Tales,” alongside The Children of Húrin and Beren and Lúthien. It was compiled and edited by his son and literary executor, Christopher Tolkien, and contains multiple versions of the story, accompanied by the younger Tolkien’s commentary and Alan Lee’s sublime illustrations, as well as a list of names and places, additional notes, genealogies, and a glossary.

The centerpiece of the book consists of the original story and the final version, written thirty-five years apart. Christopher Tolkien compares the two in his accompanying essay. All of the material here appears in other collections of Tolkien’s writings (e.g., The Silmarillion, The History of Middle-earth), but grouping them together in one volume allows the reader to compare them more directly and see how the story evolved.

Tolkien began writing The Fall of Gondolin in 1916, making it the first story belonging to the Middle-earth mythos that he ever wrote. Like the other “Great Tales,” it takes place during the First Age, about six thousand years before The Lord of the Rings. Its protagonist is Tuor, son of Huor and cousin of Túrin Turambar. He is visited by Ulmo, Vala of Waters and the “mightiest of all Valar next to Manwë,” who arises from the water amid a storm and instructs him to find Gondolin and tell Turgon, King of Gondolin, to prepare to battle Morgoth. He then embarks on his journey, guided by an Elf called Voronwë.

When Turgon rejects this advice, Tuor tells him to lead the Gondothlim to safety in Valinor. But Turgon insists on remaining in Gondolin. Tuor marries Idril, Turgon’s daughter; their son is Eärendel (later known for his sea voyages and for being the father of Elrond).

The hidden city of Gondolin was founded by Turgon and is located in Beleriand in Middle-earth. It is described as an idyllic city characterized by “fair houses and courts amid gardens of bright flowers” and “many towers of great slenderness and beauty builded of white marble.” Its inhabitants are Noldorin Elves, known for their skill in lore and crafts. They are similar to Europeans in appearance and are described elsewhere as having fair skin, grey/blue eyes, and brown, red, or silver hair. The Gondothlim are also known for their warlike prowess and are skilled archers. They were the only Noldor who did not fall to Morgoth (here called Melko/Melkor) after the catastrophic Battle of Unnumbered Tears. The location of their city remained unknown to Morgoth for nearly four centuries.

The enmity between Morgoth and the Noldor dates back to their days in Valinor. Morgoth envied Noldorin craftsmanship and lusted after the Silmarils (created by Fëanor, son of Finwë, High King of the Noldor). After sowing lies and discord among them, he destroyed the Two Trees of Valinor, killed Finwë, and stole the three Silmarils. Led by Fëanor, the Noldor rebelled against the Valar and pursued Morgoth, crossing the sea to Middle-earth. (These events are detailed in The Silmarillion.)

Gondolin is ultimately betrayed by Turgon’s nephew, Meglin, after he is captured by Orcs. Fearing for his life, he offers to reveal Gondolin’s location to Morgoth and ends up assisting him in his plan to capture the city. Christopher Tolkien calls this “the most infamous treachery in the history of Middle-earth.” Interestingly, Meglin is described as having a swarthy complexion and is rumored to have some Orcish blood.

Morgoth launches an attack on Gondolin with Balrogs, dragons, and Orcs. The ensuing battle is described at length in the earliest version of the story. The Gondothlim fight valiantly, but the battle is a decisive victory for Morgoth. The city goes up in flames, and Turgon is killed. Tuor, Idril, and Eärendel, along with other survivors – including the warrior Glorfindel (whose name means “golden-haired”) – escape through a secret tunnel and flee. They are ambushed by a Balrog and some Orcs. Glorfindel heroically battles the Balrog atop a precipice, perishing in the act. Thorondor (Lord of the Eagles) gives him a proper burial.

Tolkien began writing The Fall of Gondolin while in the hospital after having fought in the Battle of the Somme, and there are echoes of his wartime experiences in the battle scene. This passage evokes the horror of modern technological warfare:

Some were all iron so cunningly linked that they might flow like slow rivers of metal or coil themselves around and above all obstacles before them, and these were filled in their innermost depths with the grimmest of the Orcs with scimitars and spears; others of bronze and copper were given hearts and spirits of blazing fire, and they blasted all that stood before them with the terror of their snorting or trampled whatso escaped the ardour of their breath.

The fall of Gondolin marked Morgoth’s triumph over Middle-earth. He was not defeated until Eärendel persuaded the Valar to unite against Morgoth during the War of Wrath, ushering in the Second Age.

The essential story remains the same across each version presented here, though there are minor differences. The last version is most unlike the others. It depicts Tuor’s meeting with Ulmo and his journey with Voronwë in detail but stops abruptly upon his arrival at Gondolin. This is unfortunate, because it is the most well-written of the lot. The scenes depicting Ulmo’s appearance before Tuor (“clad in a gleaming coat, close-fitted as the mail of a mighty fish, and in a kirtle of deep green that flashed and flickered with sea-fire as he strode slowly toward the land”) and Tuor’s entrance through the seven gates of Gondolin are particularly striking.

As the last Elvish stronghold amid a sea of Balrogs, Orcs, and other mutant creatures, Gondolin cannot help but bring to mind examples of white enclaves located in non-white countries – the Germans in Jamaica, the Poles in Haiti, the Confederates in Brazil, and so forth. None of these groups still exist. It is a very grim prognosis, but whites under such conditions are doomed to the same fate as Gondolin (albeit through the subtler means of miscegenation), and such conditions will eventually become the norm if present trends continue.

I recommend The Fall of Gondolin to all Tolkien fans. The commentary and notes shed light on the story, and it’s interesting to compare the different versions side-by-side. Christopher Tolkien writes that this is “indubitably the last” Tolkien publication. It is really the end of an era.

14:07 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tolkien, littérature, littérature anglaise, lettres, lettres anglaises |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

The following is the text of a talk given in London on May 27, 2018 at The Poet at War, an event convened by Vortex Londinium.

“We want an European religion. Christianity is verminous with semitic infections. What we really believe is the pre-Christian element which Christianity has not stamped out . . .”[1] [2]

“If a race NEGLECTS to create its own gods, it gets the bump.”[2] [3]

“The glory of the polytheistic anschauung is that it never asserted a single and obligatory path for everyone. It never caused the assertion that everyone was fit for initiation and it never caused an attempt to force people into a path alien to their sensibilities.

Paganism never feared knowledge. It feared ignorance, and under a flood of ignorance it was driven out of its temples.”[3] [4]

Pound is a forest and one is in need of principles by which to navigate him, otherwise one is apt to lose sight of the wood for the trees, as we say in English. What I shall call Pound’s paganism can, I submit, offer one of the more direct routes into the man and his work, and in particular, into the heart of his most difficult: The Cantos.

At the same time, in the opposite direction, his poetry and prose can bring one to a better understanding of this part of our heritage and its potentialities, and here I intend no narrowly partisan point. By paganism I mean a central stream in European civilization, something that has participated in the formation of Christianity just as much as offering alternative visions of life. To give one example, the theologically fundamental doctrine of the Trinity is arguably a modified form of the Neo-Platonic triad of the One, Intellect, and Soul, in which the latter two emanate from the One and yet both are equivalent to it and yet not equivalent to it. St. Augustine in his Confessions confirms [5] that he and other Christian intellectuals believed thus that the Neo-Platonists had already had an awareness of the persons of the Trinity.

Pound was pagan in three respects. First, he accepted as true ideas from the pre- and non-Christian philosophers. One finds a Neo-Platonic orientation of mind, in the foreground or background, from the very first poem in his first published anthology, “Grace Before Song,” to the very last words of the final Canto, “Canto CXVI”:

To confess wrong without losing rightness:

Charity I have had sometimes,

I cannot make it flow thru.

A little light, like a rushlight

to lead back to splendour.[4] [6]

It is the idea of light as the symbol for a higher form of reality, of a more real reality, which all things may draw closer towards and so perfect themselves – it is this idea that unites how he speaks of the ethical precepts of Confucius, the financial theories of Major Douglas, the politics of John Adams, and the poetry of Cavalcanti, all aids towards the perfected man and the perfected society.

This is that first poem, from A Lume Spento, in 1908:

Lord God of heaven that with mercy dight

Th’alternate prayer wheel of the night and light

Eternal hath to thee, and in whose sight

Our days as rain drops in the sea surge fall,

As bright white drops upon a leaden sea

Grant so my songs to this grey folk may be:

As drops that dream and gleam and falling catch the sun

Evan’scent mirrors every opal one

Of such his splendor as their compass is,

So, bold My Songs, seek ye such death as this.[5] [7]

The second and obvious respect in which Pound was pagan was that he accepted as valid indigenous images, names, and myths, by which Deity has revealed Itself to the Europeans. He claimed that the only safe guides in religion were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the writings of Confucius.[6] [8]

The second and obvious respect in which Pound was pagan was that he accepted as valid indigenous images, names, and myths, by which Deity has revealed Itself to the Europeans. He claimed that the only safe guides in religion were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the writings of Confucius.[6] [8]

Which brings one to the third respect. He was pagan in his ethics, in the sense that he sought precepts that had arisen through tradition, were enshrined in custom, and were implicit in the natural order and man’s place within it. When he was captured by the partisans after the war and assumed he was about to face execution, it was the Analects of Confucius that he took with him, which he considered a better guide to moral behavior than the Bible: “The unshakable wisdom of Confucius . . . in comparison with which Christianity is a fad.”[7] [9]

In Pagan Ethics: Paganism as a World Religion,[8] [10] Professor Michael York unambiguously speaks of Confucianism as a religion, with its principles of solicitous care, decency, and benevolence, and the obverse of the Golden Rule: Do not do to others as you would not have done to yourself. Another example: Act in such a way that your descendants will be glad. In its emphasis on correct relationships between oneself and one’s family, between oneself and those above one and below one in society, between oneself and those who came before one in time, and between oneself and those who will come after one, Pound perceived the same multi-directional communitarian values that he found in Fascism.

Cut to London in the years following 1908, when Pound settled here. With the rise of science and biblical scholarship precipitating a crisis of faith in the mid-nineteenth century, some of the space hitherto occupied by the established denominations began to be filled by mysticism, occultism, and philosophies drawn from earlier times or from other parts of the world; and this was nowhere more evident than within the artistic circles in which Pound would move. The Theosophical Society was founded by Madame Blavatsky in 1875, and one of the emblematic texts of the aesthetic movement, Walter Pater’s work of fiction, Marius the Epicurean, appeared ten years later, providing a fully fleshed-out account of how non-Christian, Classical concepts of spirituality and the Good might be just as valid a way to live well as the prevailing religious norms.

The major source which fed Pound’s development as a religious thinker was, as has been indicated, Neo-Platonism, which is simply the continuation of Plato’s ideas, namely their elaboration and exegesis, principally through Plotinus but also through a host of others, including Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola in Italy, and later through the translations of the eighteenth-century English Neo-Platonist Thomas Taylor, whose books were read by and influenced poets such as Blake, Shelley, and Yeats.

What Pound found within Neo-Platonism was:

It seems Pound was congenitally disposed to such ideas. When interviewed during his stay in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital after his return to America in 1946, he said he had been under the influence of mysticism between the ages of 16 to 24.[10] [12] Later in his life, he wrote two refreshingly precise and disciplined statements of his own philosophy: “Religio, or the Child’s Guide to Knowledge (1918) and “Axiomata” (1923). The first is a catechism, a series of simple questions and answers which enunciates a pagan theology as well as any other text of such brevity of which I am aware.

He was drawn to Plotinus because Plotinus defended the value of worldly sensations and attacked their rejection by the Gnostics, who thought physicality evil in some sense. He was drawn to the idea in Plotinus that the beauty of this world is the manifestation of a celestial beauty, which we may not be able to grasp but which is yet a glimpse of a paradise that imparts to us, within a limited time, an unlimited joy.

But unlike Plotinus, who thought that this glimpse into the world of ideal forms was but the penultimate stage in the union with the One, a union with the absolute, an entity without parts or qualities, Pound seemed to believe that this was an unwarranted assumption, which one’s highest experiences neither legitimated nor needed. His type of paganism was without dogmatism or unnecessary abstraction: “To replace the marble Goddess on Her pedestal at Terracina is worth more than any metaphysical argument.”[11] [13]

The vast, sprawling, expansive sequence of poems called The Cantos is Pound’s attempt to fashion a work that embraced all things that seemed relevant, all things that needed to be said. It makes use of twenty-five languages – twenty-six if one includes musical notation. It draws on Dante’s Divine Comedy in the progression from the dark depths to the upper regions; Ovid’s Metamorphoses in the treatment of impermanence and change, and of the human and the mythic; and Homer’s Odyssey, in the hero’s endeavor to succeed over obstacles and achieve victory, and victory not merely in worldly terms.

Plotinus regarded Homer’s Odyssey as a metaphor for the journey of the individual soul to return home into the Great Soul of the absolute, and this became for Pound almost a foundational myth for civilization. The Cantos begins therefore with an account of Odysseus making landfall and offering sacrifice to the gods. Paganism, in its Hellenic manifestation, he saw as the golden thread that ran overtly through the Classical era, covertly through the Middle Ages, and surfaced again in the Renaissance, indeed being implicit alongside the explicit Christianity of his favorite author, Dante Alighieri.

In the essay “Psychology and Troubadours” (1912), he posited a continuity of Classical paganism in the south of France:

Provence was less disturbed than the rest of Europe by invasion . . . if paganism survived anywhere, it would have been, unofficially, in the Langue d’Oc. That the spirit was, in Provence, Hellenic, is seen readily enough by anyone who will compare the Greek Anthology with the work of the Troubadours. They have, in some way, lost the names of the Gods, and remembered the names of lovers.[12] [14]

One recognizes a person that one actually knows by sight, by who the person is, not because of the name. A person may be called by different names yet be the same person still. “Tradition inheres in the images of the Gods, and gets lost in dogmatic definitions . . . But the images of the Gods . . . move the soul to contemplation and preserve the tradition of the undivided light.”[13] [15]

One recognizes a person that one actually knows by sight, by who the person is, not because of the name. A person may be called by different names yet be the same person still. “Tradition inheres in the images of the Gods, and gets lost in dogmatic definitions . . . But the images of the Gods . . . move the soul to contemplation and preserve the tradition of the undivided light.”[13] [15]

Before I close with a poem, I should like to put forward two conclusions.

First, with the insights into the Cantos offered by Neoplatonic paganism, one can put to one side some of the less inspiring critical readings – that it is a record of a lifetime’s reading, or an old man’s descent into confusion – and it becomes again the epic he intended it to be, the struggle of light against darkness, of heroes with themselves and with the world to reach a blessed place.

And second, with Pound’s veneration for the past and his appetite for the future, for making it new, as he put it, with his courage and capacity for friendship, with the range of his enthusiasms, and the range of what he was not satisfied with, he is an ideal figure to head any movement of European rebirth. And this poem, “Surgit Fama”[14] [16] (“it rises to fame”), seems to be about that more than anything else. The first stanza depicts a stirring in the world, the coming of Korè who is Persephone, the returning and reborn Spring; in consort with Leuconoë, the girl to whom Horace addresses the famous injunction to seize the day, carpe diem.[15] [17] In the second stanza, when the poet tries to render this into verse, he has to resist any superfluity, any unnecessary words that may be circulated as rumor or bent in their meaning, which he feels Hermes may tempt him to, and he addresses himself, exhorting himself to speak true. And in the final stanza that is what he does, when he says how in Delos, the island where it was said Apollo and Artemis were born, once again shall rites be enacted and the story continued.

There is a truce among the Gods,

Korè is seen in the North

Skirting the blue-gray sea

In gilded and russet mantle.

The corn has again its mother and she, Leuconoë,

That failed never women,

Fails not the earth now.

The tricksome Hermes is here;

He moves behind me

Eager to catch my words,

Eager to spread them with rumour;

To set upon them his change

Crafty and subtle;

To alter them to his purpose;

But do thou speak true, even to the letter:

“Once more in Delos, once more is the altar a quiver.

Once more is the chant heard.

Once more are the never abandoned gardens

Full of gossip and old tales.”

Notes

[1] [18] Ezra Pound, “Statues of Gods,” The Townsman, August 1939; in William Cookson (ed.), Ezra Pound, Selected Prose 1909-1965 (London: Faber and Faber, 1973), p. 71.

[2] [19] Ezra Pound, “Deus et Amor,” The Townsman, June 1940; Selected Prose, p. 72.

[3] [20] Ezra Pound, “Terra Italica,” The New Review, Winter, 1931-2; Selected Prose, p. 56.

[4] [21] Ezra Pound, The Cantos (London: Faber and Faber, 1975), p. 743.

[5] [22] Michael John King (ed.), The Collected Early Poems of Ezra Pound, ed. Michael John King (London: Faber and Faber, 1977), p. 7.

[6] [23] In a letter from 1922 to Dr. Felix E. Schelling, in D. D. Paige (ed.), The Selected Letters of Ezra Pound, 1907-1941 (London: Faber and Faber, 1950), p. 182.

[7] [24] “Statues of Gods,” Selected Prose, p. 71.

[8] [25] Michael York, Pagan Ethics: Paganism as a World Religion (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016), p. 356.

[9] [26] Porphyry, The Life of Plotinus, in Plotinus, vol. I, trans. Arthur Hilary Armstrong (Cambridge, Mass.: Loeb Classics, Harvard University Press, 1995), p. 7.

[10] [27] Peter Liebregts, Ezra Pound and Neoplatonism (Madison: Rosemont Publishing, 2004), p. 34.

[11] [28] Ezra Pound, “A Visiting Card,” written in Italian and first published in Rome in 1942; the translation by John Drummond was first published by Peter Russell in 1952; Selected Prose, p. 290.

[12] [29] Ezra Pound, The Spirit of Romance (London: Peter Owen, 1952), p. 90.

[13] [30] “A Visiting Card”; Selected Prose, p. 277.

[14] [31] Ezra Pound, Collected Shorter Poems (London: Faber and Faber, 1952), p. 99.

[15] [32] Horace, Odes, I, XI.

01:22 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ezra pound, poésie, paganisme, littérature, lettres, lettres américaines, littérature américaine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

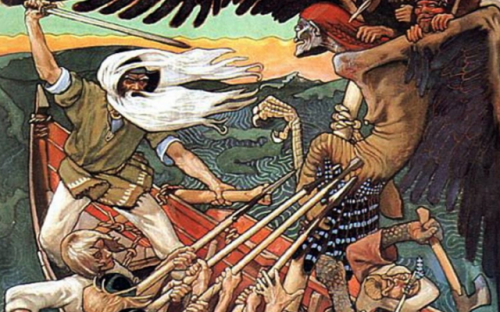

Among the vast array of sources that influenced Tolkien in the creation of his legendarium was the Kalevala, a collection of Finnish folk poetry compiled and edited by the Finnish physician and philologist Elias Lönnrot. Much scholarship exists on Tolkien’s Norse, Germanic, and Anglo-Saxon influences, but his interest in the Kalevala is not as often discussed.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835, but the tales therein date back to antiquity and were handed down orally. The poems were originally songs, all sung in trochaic tetrameter (now known as the “Kalevala meter”). This oral tradition began to decline after the Reformation and the suppression of paganism by the Lutheran Church. It is largely due to the efforts of collectors like Lönnrot that Finnish folklore has survived.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835, but the tales therein date back to antiquity and were handed down orally. The poems were originally songs, all sung in trochaic tetrameter (now known as the “Kalevala meter”). This oral tradition began to decline after the Reformation and the suppression of paganism by the Lutheran Church. It is largely due to the efforts of collectors like Lönnrot that Finnish folklore has survived.

Lönnrot’s task in creating the Kalevala was to arrange the raw material of the poems he collected into a single literary work with a coherent arc. He made minor modifications to about half of the oral poetry used in the Kalevala and also penned some verses himself. Lönnrot gathered more material in subsequent years, and a second edition of the Kalevala was published in 1849. The second edition consists of nearly 23,000 verses, which are divided into 50 poems (or runos), further divided into ten song cycles. This is the version most commonly read today.

The main character in the Kalevala is Väinämöinen, an ancient hero and sage, or tietäjä, a man whose vast knowledge of lore and song endows him with supernatural abilities. Other characters include the smithing god Ilmarinen, who forges the Sampo; the reckless warrior Lemminkäinen; the wicked queen Louhi, ruler of the northern realm of Pohjola; and the vengeful orphan Kullervo.

Much of the plot concerns the Sampo, a mysterious magical object that can produce grain, salt, and gold out of thin air. The exact nature of the Sampo is ambiguous, though it is akin to the concept of the world pillar or axis mundi. Ilmarinen forges the Sampo for Louhi in return for the hand of her daughter. Louhi locks the Sampo in a mountain, but the three heroes (Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen, and Lemminkäinen) sail to Pohjola and steal it back. During their journey homeward, Louhi summons the sea monster Iku-Turso to destroy them and commands Ukko, the god of the sky and thunder, to incite a storm. Väinämöinen wards off Iku-Turso but loses his kantele (a traditional Finnish stringed instrument that Väinämöinen is said to have created). A climax is reached when Louhi morphs into an eagle and attacks the heroes. She seizes the Sampo, but Väinämöinen attacks her, and it falls into the sea and is destroyed. Väinämöinen collects the fragments of the Sampo afterward and creates a new kantele. In nineteenth-century Finland, Väinämöinen’s fight against Louhi was seen as the embodiment of Finland’s struggle for nationhood.

It is likely that Finland would not exist as an independent nation were it not for the Kalevala. The poem was central to the Finnish national awakening, which began in the 1840s and eventually resulted in Finland’s declaration of independence from Russia in December 1917. It also played a role in the movement to elevate the Finnish language to official status.

The publication of the Kalevala brought about a flowering of artistic and literary achievement in Finland. The art of Finland’s greatest painter, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, is heavily influenced by Finnish mythology and folk art, and many of his works (The Defence of the Sampo, The Forging of the Sampo, Lemminkäinen’s Mother, Kullervo Rides to War, Kullervo’s Curse, Joukahainen’s Revenge) depict scenes from the Kalevala. The Kalevala has also influenced a number of composers, most notably Sibelius, whose Kalevala-inspired compositions include his Kullervo, Tapiola, Lemminkäinen Suite, Luonnotar, and Pohjola’s Daughter.

Tolkien first read the Kalevala at the age of 19. The poem had a great impact on him and remained one of his lifelong influences. While still at Oxford, he wrote a prose retelling of the Kullervo cycle. This was his first short story and “the germ of [his] attempt to write legends of [his] own.”[1] His fascination with the Kalevala during this time also inspired him to learn Finnish, which he likened to an “amazing wine” that intoxicated him.[2] Finnish was an important influence on the Elvish language Quenya.

In the Kalevala, Kullervo is an orphan whose tribe was massacred by his uncle Untamo. After attempting in vain to kill the young Kullervo, Untamo sells him as a slave to Ilmarinen and his wife. Kullervo later escapes and learns that some of his family are still alive, though his sister is still considered missing. He then seduces a girl who turns out to be his sister; she kills herself upon this realization. Kullervo vows to gain revenge on Untamo and massacres Untamo’s tribe, killing each member. He returns home to find the rest of his family dead and finally kills himself in the spot where he seduced his sister. The character of Kullervo was the main inspiration for Túrin Turambar in The Silmarillion.

There are a handful of other parallels. The hero Väinämöinen likely provided inspiration for the characters of Gandalf and Tom Bombadil, particularly the latter.[3] Tom Bombadil is as old as creation itself, and his gift of song gives him magical powers. The magical properties of singing also feature in The Silmarillion when Finrod and Sauron duel through song and when Lúthien sings Morgoth to sleep (as when Väinämöinen sings the people of Pohjola to sleep). Ilmarinen likely inspired the character of Fëanor, creator of the Silmarils.[4] The Silmarils are much like the Sampo in nature, and the quest to retrieve them parallels the heroes’ quest to capture the Sampo.

The animism that pervades Tolkien’s mythology (as when Caradhras “the Cruel” attempts to sabotage the Fellowship’s journey or when the stones of Eregion speak of the Elves who once lived there) also hearkens back to the Kalevala, in which trees, hills, swords, and even beer possess consciousness.

For Tolkien, the appeal of the Kalevala lay in its “weird tales” and “sorceries,” which to him evinced a “very primitive undergrowth that the literature of Europe has on the whole been steadily cutting away and reducing for many centuries . . . .” He continues: “I would that we had more of it left — something of the same sort that belonged to the English . . . .”[5]

The desire to create a national mythology for England in the vein of Lönnrot’s Kalevala was the impetus behind Tolkien’s own legendarium. Not unlike Lönnrot, he envisioned himself as a collector of ancient stories whose role it was to craft an epic that would capture the spirit of the nation. He writes in a letter:

. . . I was from early days grieved by the poverty of my own beloved country: it had no stories of its own (bound up with its tongue and soil), not of the quality that I sought, and found (as an ingredient) in legends of other lands. There was Greek, and Celtic, and Romance, Germanic, Scandinavian, and Finnish (which greatly affected me); but nothing in English . . . . I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and the cosmogonic, to the level of romantic fairy-story — the larger founded on the lesser in contact with the earth, the lesser drawing splendour from the vast backcloths — which I could dedicate simply to England; to my country . . . . The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama.[6]

Tolkien had England in mind, but his mythology is one that all whites can unite around, in the same manner that the races of the Fellowship united to save Middle-earth. The heroic and racialist themes in Tolkien’s mythology are readily apparent, and the fight against the forces of evil parallels the current struggle.

The role of the Kalevala in Finland’s fight for independence attests to the revolutionary potential of literature and art. Tolkien’s mythology offers rich material from which to draw and indeed has already inspired many works of art, music, literature, etc., as Tolkien himself hoped.[7] Perhaps the revolution will be led by Tolkien fans.

Notes

1. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Story of Kullervo, ed. Verlyn Flieger (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017), 52.

2. Ibid., 136.

3. Gandalf’s departure to Valinor also brings to mind when Väinämöinen sails away to a realm located in “the upper reaches of the world, the lower reaches of the heavens” at the end of the Kalevala.

4. Ilmarin, the domed palace of Manwë and Varda, is another possible allusion to Ilmarinen, who created the dome of the sky. The region of the stars and celestial bodies in Tolkien’s cosmology is called Ilmen (“ilma” means “air” in Finnish). Eru Ilúvatar also recalls Ilmatar (an ancient “air spirit” and the mother of Väinämöinen).

5. The Story of Kullervo, 105. This comes from his revised essay, which was written sometime in the late 1910s or early 20s.

6. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1981), 144.

7. Here could be the place to note that a major exhibit of Tolkien’s papers, illustrations, and maps recently opened in Oxford and will soon be accompanied by a book (Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth).

11:03 Publié dans Littérature, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : kalevala, tolkien, littérature, littérature anglaise, lettres, lettres anglaises, traditions, mythologie, finlande, sibelius, épopée finnoise |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

par Nicolas Bonnal

Ex: http://www.dedefensa.org

Reparlons de la fin de l’histoire…

La catastrophe est arrivée avec Louis-Philippe, tout le monde devrait le savoir (cela me rappelle je ne sais quel journaliste royaliste qui me demandait si j’étais orléaniste ou légitimiste. On est légitimiste ou on n’est pas monarchiste, voilà tout). Depuis, on barbote. Voyez l’autre avec sa banque Rothschild et sa soumission aux patrons anglo-saxons.

Balzac c’est la comédie humaine et c’est aussi la recherche de l’absolu qui n’aboutit plus - et on n’a rien fait de mieux depuis. Car Balzac a compris mieux que tout le monde le monde moderne, peut-être mieux que Guénon même (à savoir que les résurrections et recommandations spirituelles seraient des potions, des simulacres).

Extraits de Z. Marcas, petite nouvelle méconnue, prodigieuse. On commence par la chambre de bonne :

« Comment espère-t-on faire rester les jeunes gens dans de pareils hôtels garnis ? Aussi les étudiants étudient-ils dans les cafés, au théâtre, dans les allées du Luxembourg, chez les grisettes, partout, même à l’École de Droit, excepté dans leur horrible chambre, horrible s’il s’agit d’étudier, charmante dès qu’on y babille et qu’on y fume. »

Les études professionnelles comme on dit au Pérou, de médecin, d’avocat, sont déjà des voies bouchées, observe le narrateur avec son ami Juste :

« Juste et moi, nous n’apercevions aucune place à prendre dans les deux professions que nos parents nous forçaient d’embrasser. Il y a cent avocats, cent médecins pour un. La foule obstrue ces deux voies, qui semblent mener à la fortune et qui sont deux arènes… »

Une observation sur la pléthorique médecine qui eût amusé notre Céline :

« L’affluence des postulants a forcé la médecine à se diviser en catégories : il y a le médecin qui écrit, le médecin qui professe, le médecin politique et le médecin militant ; quatre manières différentes d’être médecin, quatre sections déjà pleines. Quant à la cinquième division, celle des docteurs qui vendent des remèdes, il y a concurrence, et l’on s’y bat à coups d’affiches infâmes sur les murs de Paris. »

Oh, le complexe militaro-pharmaceutique ! Oh, le règne de la quantité !

Les avocats et l’Etat :

« Dans tous les tribunaux, il y a presque autant d’avocats que de causes. L’avocat s’est rejeté sur le journalisme, sur la politique, sur la littérature. Enfin l’État, assailli pour les moindres places de la magistrature, a fini par demander une certaine fortune aux solliciteurs. »

Cinquante ans avant Villiers de l’Isle-Adam Balzac explique le triomphe de la médiocrité qui maintenant connaît son apothéose en Europe avec la bureaucratie continentale :

« Aujourd’hui, le talent doit avoir le bonheur qui fait réussir l’incapacité ; bien plus, s’il manque aux basses conditions qui donnent le succès à la rampante médiocrité, il n’arrivera jamais. »

Balzac recommande donc comme Salluste (et votre serviteur sur un plateau télé) la discrétion, l’éloignement :

« Si nous connaissions parfaitement notre époque, nous nous connaissions aussi nous-mêmes, et nous préférions l’oisiveté des penseurs à une activité sans but, la nonchalance et le plaisir à des travaux inutiles qui eussent lassé notre courage et usé le vif de notre intelligence. Nous avions analysé l’état social en riant, en fumant, en nous promenant. Pour se faire ainsi, nos réflexions, nos discours n’en étaient ni moins sages, ni moins profonds. »

On se plaint en 2018 du niveau de la jeunesse ? Balzac :

« Tout en remarquant l’ilotisme auquel est condamnée la jeunesse, nous étions étonnés de la brutale indifférence du pouvoir pour tout ce qui tient à l’intelligence, à la pensée, à la poésie. »

Liquidation de la culture, triomphe idolâtre de la politique et de l’économie :

« Quels regards, Juste et moi, nous échangions souvent en lisant les journaux, en apprenant les événements de la politique, en parcourant les débats des Chambres, en discutant la conduite d’une cour dont la volontaire ignorance ne peut se comparer qu’à la platitude des courtisans, à la médiocrité des hommes qui forment une haie autour du nouveau trône, tous sans esprit ni portée, sans gloire ni science, sans influence ni grandeur. »

Comme Stendhal, Chateaubriand et même Toussenel, Balzac sera un nostalgique de Charles X :

« Quel éloge de la cour de Charles X, que la cour actuelle, si tant est que ce soit une cour ! Quelle haine contre le pays dans la naturalisation de vulgaires étrangers sans talent, intronisés à la Chambre des Pairs ! Quel déni de justice ! quelle insulte faite aux jeunes illustrations, aux ambitions nées sur le sol ! Nous regardions toutes ces choses comme un spectacle, et nous en gémissions sans prendre un parti sur nous-mêmes. »

Balzac évoque la conspiration et cette époque sur un ton qui annonce Drumont aussi (en prison, Balzac, au bûcher !) :

« Juste, que personne n’est venu chercher, et qui ne serait allé chercher personne, était, à

vingt-cinq ans, un profond politique, un homme d’une aptitude merveilleuse à saisir les rapports lointains entre les faits présents et les faits à venir. Il m’a dit en 1831 ce qui devait arriver et ce qui est arrivé : les assassinats, les conspirations, le règne des juifs, la gêne des mouvements de la France, la disette d’intelligences dans la sphère supérieure, et l’abondance de talents dans les bas-fonds où les plus beaux courages s’éteignent sous les cendres du cigare. Que devenir ? »

Les Français de souche qui en bavent et qui s’expatrient ? Lisez Balzac !

« Être médecin n’était-ce pas attendre pendant vingt ans une clientèle ? Vous savez ce qu’il est devenu ? Non. Eh ! bien, il est médecin ; mais il a quitté la France, il est en Asie. »

La conclusion du jeune grand homme :

« J’imite Juste, je déserte la France, où l’on dépense à se faire faire place le temps et l’énergie nécessaires aux plus hautes créations. Imitez-moi, mes amis, je vais là où l’on dirige à son gré sa destinée. »

Homo festivus… Chez Balzac il y a toujours une dérision bien française face aux échecs de la vie et du monde moderne et déceptif.

Il y a une vingtaine d’années j’avais rappelé à Philippe Muray que chez Hermann Broch comme chez Musil (génie juif plus connu mais moins passionnant) il y avait une dénonciation de la dimension carnavalesque dans l’écroulement austro-hongrois.

Chez Balzac déjà on veut s’amuser, s’éclater, fût-ce à l’étranger. Il cite même Palmyre :

« Après nous être longtemps promenés dans les ruines de Palmyre, nous les oubliâmes, nous étions si jeunes ! Puis vint le carnaval, ce carnaval parisien qui, désormais, effacera l’ancien carnaval de Venise, et qui dans quelques années attirera l’Europe à Paris, si de malencontreux préfets de police ne s’y opposent. On devrait tolérer le jeu pendant le carnaval ; mais les niais moralistes qui ont fait supprimer le jeu sont des calculateurs imbéciles qui ne rétabliront cette plaie nécessaire que quand il sera prouvé que la France laisse des millions en Allemagne. Ce joyeux carnaval amena, comme chez tous les étudiants, une grande misère… »

Puis Balzac présente son Marcas – très actuel comme on verra :

« Il savait le Droit des gens et connaissait tous les traités européens, les coutumes internationales. Il avait étudié les hommes et les choses dans cinq capitales : Londres, Berlin, Vienne, Petersburg et Constantinople. Nul mieux que lui ne connaissait les précédents de la Chambre. »

Les élites ? Balzac :

« Marcas avait appris tout ce qu’un véritable homme d’État doit savoir ; aussi son étonnement fut-il excessif quand il eut occasion de vérifier la profonde ignorance des gens parvenus en France aux affaires publiques. »

Il devine le futur de la France :

« En France, il n’y aura plus qu’un combat de courte durée, au siège même du gouvernement, et qui terminera la guerre morale que des intelligences d’élite auront faite auparavant. »

Les politiques, les sénateurs US comme des marionnettes, comme dans le Parrain. Balzac :

« En trois ans, Marcas créa une des cinquante prétendues capacités politiques qui sont les raquettes avec lesquelles deux mains sournoises se renvoient les portefeuilles, absolument comme un directeur de marionnettes heurte l’un contre l’autre le commissaire et Polichinelle dans son théâtre en plein vent, en espérant toujours faire sa recette. »

Corleone Marcas est comme un boss, dira Cochin, qui manipule ses mannequins :

« Sans démasquer encore toutes les batteries de sa supériorité, Marcas s’avança plus que la première fois, il montra la moitié de son savoir-faire ; le ministère ne dura que cent quatre-vingts jours, il fut dévoré. Marcas, mis en rapport avec quelques députés, les avait maniés comme pâte, en laissant chez tous une haute idée de ses talents. Son mannequin fit de nouveau partie d’un ministère, et le journal devint ministériel. »

Puis Balzac explique l’homme moderne, électeur, citoyen, consommateur, politicard, et « ce que Marcas appelait les stratagèmes de la bêtise : on frappe sur un homme, il paraît convaincu, il hoche la tête, tout va s’arranger ; le lendemain, cette gomme élastique, un moment comprimée, a repris pendant la nuit sa consistance, elle s’est même gonflée, et tout est à recommencer ; vous retravaillez jusqu’à ce que vous ayez reconnu que vous n’avez pas affaire à un homme, mais à du mastic qui se sèche au soleil. »

Et comme s’il pensait à Trump ou à nos ex-vingtième siècle, aux promesses bâclées des politiciens, Balzac dénonce « la difficulté d’opérer le bien, l’incroyable facilité de faire le mal. »

Et comme s’il fallait prouver que Balzac est le maître :

« …il y a pour les hommes supérieurs des Shibolet, et nous étions de la tribu des lévites modernes, sans être encore dans le Temple. Comme je vous l’ai dit, notre vie frivole couvrait les desseins que Juste a exécutés pour sa part et ceux que je vais mettre à fin. »

Et sur l’éternel présent de la jeunesse mécontente :

« La jeunesse n’a pas d’issue en France, elle y amasse une avalanche de capacités méconnues, d’ambitions légitimes et inquiètes, elle se marie peu, les familles ne savent que faire de leurs enfants ; quel sera le bruit qui ébranlera ces masses, je ne sais ; mais elles se précipiteront dans l’état de choses actuel et le bouleverseront. »

Vingt ans plus tard Flaubert dira que le peuple aussi est mort, après les nobles, les clercs et les bourgeois, et qu’il ne reste que la tourbe canaille et imbécile qui a gobé le Second Empire, qui marque le début de notre déclin littéraire. Si on sait pour qui vote la tourbe, on ne sait toujours pas pourquoi.

Balzac rajoute :

« Louis XIV, Napoléon, l’Angleterre étaient et sont avides de jeunesse intelligente. En France, la jeunesse est condamnée par la légalité nouvelle, par les conditions mauvaises du principe électif, par les vices de la constitution ministérielle. »

C’est JMLP qui disait un jour à notre amie Marie que 80% de nos jeunes diplômés fichent le camp. On était en 2012 ! Circulez, y’a de l’espoir…

Le piège républicain expliqué en une phrase par notre plus garnd esprit moderne (royaliste et légitimiste comme Tocqueville et Chateaubriand et Baudelaire aussi à sa manière) :

« En ce moment, on pousse la jeunesse entière à se faire républicaine, parce qu’elle voudra voir dans la république son émancipation. »

La république donnera comme on sait le radical replet, le maçon obtus, le libéral Ubu et le socialiste ventru !

Z. Marcas. Lisez cette nouvelle de seize pages, qui énonce aussi l’opposition moderne entre Russie et monde anglo-saxon !

On laisse le maître conclure : « vous appartenez à cette masse décrépite que l’intérêt rend hideuse, qui tremble, qui se recroqueville et qui veut rapetisser la France parce qu’elle se rapetisse. »

Et le patriote Marcas en mourra, prophète du déclin français :

« Marcas nous manifesta le plus profond mépris pour le gouvernement ; il nous parut douter des destinées de la France, et ce doute avait causé sa maladie…Marcas ne laissa pas de quoi se faire enterrer…

01:18 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, honoré de balzac, balzac, france, déclin, décadence |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

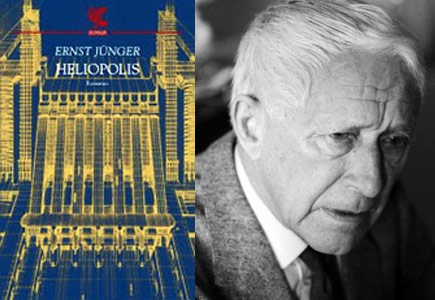

Marcello Veneziani

Ex: http://www.marcelloveneziani.com

A leggerlo con gli occhi miopi del presente, L’operaio di Ernst Jünger sembra la grandiosa metafora dell’avvento dei tecnici al potere. Anzi il Tecnico stesso sembra l’Operaio in loden, versione estrema della borghesia che si è fatta globale e immateriale come la finanza rispetto all’epoca dell’oro e del decoro.

Ma più in profondità, lo sguardo profetico di Jünger è rivolto a un’epoca planetaria dominata dalla tecnica, che ha un esito a sorpresa rispetto alle sue premesse: la tecnica «spiritualizza la terra». Dopo gli dei, dopo il monoteismo, verrà lo Spirito, signore dell’Età dell’acquario, che appare attraverso i sogni e agisce mediante la magia.

Lo spirito verrà tramite la tecnica, scrive Jünger, nel suo linguaggio oracolare, a volte allusivo, in alcuni tratti reticente, ed esoterico. Dopo la catastrofe e in fondo al tunnel del nichilismo il suo pensiero intuitivo scorge una luce inattesa. Non la luce di un nuovo umanesimo, come pensavano da differenti postazioni i suoi contemporanei Maritain e Gentile, Bloch e Sartre. Ma un disumanesimo integrale, una sorta di superamento dell’umano e non in una dimensione sovrumana, alla Nietzsche, ma compiutamente inumana, geologica e spirituale.

In questa chiave, l’Operaio è un nuovo titano, quasi una figura mitologica, della razza di Anteo, Atlante e Prometeo, che mobilita il mondo tramite la tecnica, che è il suo linguaggio. L’operaio di Jünger – o Milite del lavoro, come preferivano tradurre Delio Cantimori e anche Julius Evola – compie 80 anni e per l’occasione esce finalmente in Italia Maxima-Minima, un libro breve e intenso che fu la prosecuzione dell’opera jüngeriana del ’32 a 32 anni di distanza, nel 1964.

Quando dirigevo da ragazzo una casa editrice, negli anni Ottanta, tentai temerariamente di farlo tradurre in Italia; ma alla Buchmesse, la Fiera del libro di Francoforte, l’agente letterario di Klett Cotta, l’editore tedesco, mi disse che quest’opera era già opzionata in Italia. Ci sono voluti quasi trent’anni per vederla alla luce ora, a cura e con la postfazione di Alessandra Jadicicco.

Un’opera oracolare di minima loquacità e massima densità, in cui si avverte il respiro della grandezza, dove l’eco dell’Operaio si mescola all’eco dello Stato mondiale, Le forbici, Al muro del tempo e altre opere jüngeriane del suo personale «Nuovo Testamento», come egli stesso diceva.

La tesi metafisica è quella: dalla Macchina, per inattese vie, sorgerà lo Spirito; il Mito, il Gioco, la Geologia e l’Astrologia lo porteranno a compimento. Ma dalla Tecnica sorge anche il nemico: laddove il tecnico «conquisti il governo politico, se non dittatoriale, grava la peggiore delle minacce».

Il condensato deteriore della tecnica è l’automatismo, che è il peggiore degli autoritarismi, un dispotismo che uccide la libertà alla radice. E qui Ernst Jünger ritrova suo fratello Friedrich Georg che alla Perfezione della tecnica e all’avvento degli automi aveva dedicato un lucido saggio, degno del suo germano (tradotto in Italia dal Settimo Sigillo nel 2000).

La tesi metapolitica di Jünger è invece l’avvento auspicato dello Stato planetario, dopo l’unificazione del mondo compiuta dalla Tecnica, di cui scriveva negli stessi anni in Italia anche Ugo Spirito. Dopo la patria il mondo intero sarà amato come «Terra Natia». Destra e sinistra, rivoluzione e conservazione, sono per Jünger braccia di uno stesso corpo.

Ma il politico, rispetto a questi fenomeni grandiosi, è inadeguato, si occupa dell’ovvio dei popoli, si cura del successo e dell’attualità, non si sporge nell’avvenire e, a differenza dell’artista, non dispone di uno sguardo ulteriore. La miseria della politica propizia il dominio della tecnica (sembrano glosse al presente…). A rimorchio della politica va la giustizia che «segue la politica come gli avvoltoi le campagne degli eserciti». Dei, padri, autorità, eroi tramontano nell’era in cui la prosperità cresce con l’insicurezza.

Tocca all’outsider, che Jünger aveva battezzato già l’Anarca o il Ribelle, avvertire come un sismografo il tempo che verrà. «L’amarezza riguardo ai contemporanei è comprensibile in chi ha da dire cose immense». Pensieri lucidi e affilati come lame si susseguono nella prosa asciutta e ad alta temperatura di Jünger; a volte sfiorano la storia, i popoli, le culture, le razze.

Precorrendo o incrociando le tesi della Scuola di Francoforte e di Herbert Marcuse in particolare, Jünger nota che la nuova schiavitù e la nuova alienazione non si concentrano più nel tempo della produzione, ma nel tempo libero. La dipendenza si sposta dal lavoro al consumo. Jünger intuisce che la globalizzazione coinvolgerà non solo i popoli più avanzati, ma anche le società feudali e primitive, che rientreranno in pieno nel ciclo della tecnica: e ci pare di vedere le tigri asiatiche, la Cina, l’India e la Corea nel suo sguardo profetico.

Jünger critica la pur grandiosa morfologia della civiltà di Oswald Spengler e incontra invece il nichilismo attivo e poetico di Gottfried Benn e soprattutto il pensiero di Martin Heidegger, che a sua volta studia e fa studiare nei suoi seminari L’operaio e per altri sentieri raggiunge la stessa radura di Jüger, al di là dell’umano.

Ho letto in questi giorni, accanto a Jünger, gli appunti heideggeriani raccolti sotto il titolo La storia dell’Essere dove si respira in altre forme e linguaggi la stessa aria jüngeriana: il dominio planetario della tecnica, la rivoluzione conservatrice, il realismo eroico, il potere di cui i potenti sono esecutori e non dignitari, la guerra e la mobilitazione, la scomparsa dell’umano.

E affiora esplicito il nome di Jünger. Sullo sfondo, come un’allusione che vuol restare in ombra, la tragedia della Germania e dell’Europa. Quel che alla fine apre all’apocalittico Jünger uno spiraglio di luce nella notte è l’Amor fati, l’accettazione istintiva del destino.

«Tutto ciò che accade è adorabile» scrive Jünger citando Leon Bloy. E una leggera euforia attraversa il paesaggio catastrofico, quasi una musica sorgiva tra le rovine e gli automi.

MV, Il Giornale 2 aprile 2012

00:47 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ernst jünger, marcello veneziani, révolution conservatrice, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature, littérature allemande |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Bulletin célinien n°408 (juin 2018)

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

En marge des “Lettres familières”

Céline, le négatif et le trait d’union

Enquête sur le procès Céline [1950]

Lettres d’Alphonse Juilland à Éric Mazet (2)

Antoine Gallimard et Pierre Assouline parlent.

Angie David

En revanche, une part de son œuvre est assurément maudite au point qu’un projet de réédition a suscité de vives réactions que la plus haute autorité de l’État a estimé légitimes. La plupart des célinistes, eux, ressassent la même antienne : certes ces écrits sont intolérables mais certains passages peuvent en être sauvés. Et de citer invariablement la description de Leningrad dans Bagatelles et l’épilogue des Beaux draps. C’est perdre de vue que Céline ne perd nullement son talent dans l’invective même lorsqu’il est outrancier. Si l’on se reporte au dossier de presse de Bagatelles, on voit, au-delà des clivages idéologiques, à quel point les critiques littéraires pouvaient alors le reconnaître. « La frénésie, l’éloquence, les trouvailles de mots, le lyrisme enfin sont très souvent étonnants », relevait Marcel Arland dans La Nouvelle Revue Française. Charles Plisnier, peu suspect de complaisance envers l’antisémitisme, évoquait « un chef-d’œuvre de la plus haute classe » ². Dans une récente émission télévisée, un célinien en lut plusieurs extraits qu’il jugeait littérairement réussis, notamment l’un daubant la Russie soviétique. Passage coupé au montage. Seule la description de Leningrad a précisément été retenue. Autre réflexion: si Céline est reconnu comme un écrivain important, il n’en demeure pas moins qu’il est tenu à l’écart par l’école et l’université. Hormis Voyage au bout de la nuit et, dans une moindre mesure Mort à crédit, ses romans sont absents des programmes scolaires. Quant à l’université, on doit bien constater qu’elle organise très peu de séminaires sur son œuvre et que, parmi les universitaires habilités à diriger des recherches, rares sont ceux qui acceptent de diriger un travail sur Céline. Conséquence : le nombre de thèses à lui consacrées est en nette baisse par rapport au siècle précédent. On se croirait revenu aux années où Frédéric Vitoux puis Henri Godard rencontrèrent tous deux des difficultés à trouver un directeur de thèse. Et cela ne risque pas de s’arranger dans les années à venir.

Autre réflexion: si Céline est reconnu comme un écrivain important, il n’en demeure pas moins qu’il est tenu à l’écart par l’école et l’université. Hormis Voyage au bout de la nuit et, dans une moindre mesure Mort à crédit, ses romans sont absents des programmes scolaires. Quant à l’université, on doit bien constater qu’elle organise très peu de séminaires sur son œuvre et que, parmi les universitaires habilités à diriger des recherches, rares sont ceux qui acceptent de diriger un travail sur Céline. Conséquence : le nombre de thèses à lui consacrées est en nette baisse par rapport au siècle précédent. On se croirait revenu aux années où Frédéric Vitoux puis Henri Godard rencontrèrent tous deux des difficultés à trouver un directeur de thèse. Et cela ne risque pas de s’arranger dans les années à venir.

• Angie DAVID (éd.), Réprouvés, bannis, infréquentables, Éditions Léo Scheer, 2018, 275 p. (20 €).

00:31 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, angie david, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, revue |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

14:02 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises, censure, francis bergeron |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Bulletin célinien n°407

Sommaire :

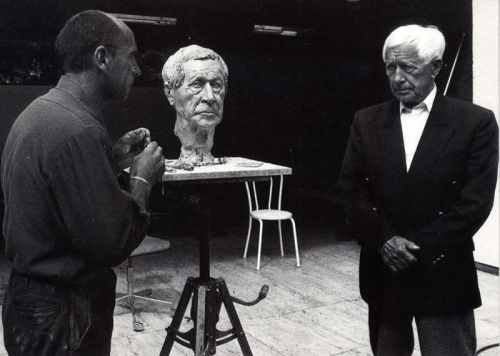

Entretien avec Henri Godard

Éditeur de Céline

L’intercesseur

Quarante années de recherches céliniennes.

La dette que les céliniens ont contractée envers Henri Godard est considérable. On songe évidemment en premier lieu à cette magistrale édition critique de l’œuvre romanesque dans la Pléiade. Que ce soit sur la génétique des textes, l’établissement des variantes, les liens entre création et expérience vécue, l’étude narrative et stylistique, il a accompli un travail à la fois rigoureux et éclairant. De sa thèse de doctorat sur la poétique de Céline soutenue il y a plus de trente ans à sa biographie qui vient d’être rééditée en collection de poche ¹, il aura sans nul doute été l’exégète le plus pénétrant de Céline. Et il a constamment mis l’accent sur l’unité d’une œuvre qui « contrairement à l’impression générale, demeure assez mal connue dans son ensemble comme dans sa distribution ² ».

La dette que les céliniens ont contractée envers Henri Godard est considérable. On songe évidemment en premier lieu à cette magistrale édition critique de l’œuvre romanesque dans la Pléiade. Que ce soit sur la génétique des textes, l’établissement des variantes, les liens entre création et expérience vécue, l’étude narrative et stylistique, il a accompli un travail à la fois rigoureux et éclairant. De sa thèse de doctorat sur la poétique de Céline soutenue il y a plus de trente ans à sa biographie qui vient d’être rééditée en collection de poche ¹, il aura sans nul doute été l’exégète le plus pénétrant de Céline. Et il a constamment mis l’accent sur l’unité d’une œuvre qui « contrairement à l’impression générale, demeure assez mal connue dans son ensemble comme dans sa distribution ² ».

« Nous avons en commun de travailler à donner à Céline, en dépit des handicaps, toute la place qui est la sienne », m’a-t-il écrit un jour. C’était aussi reconnaître implicitement tout ce qui nous sépare. L’un des mérites d’Henri Godard aura été de surmonter ce qui aurait pu l’empêcher de vouer une grande partie de sa carrière à l’œuvre d’un homme dont il est si éloigné. Dans son dernier livre sur Céline, il ne dissimule pas les tourments que cela a pu susciter sur le plan personnel : « Autour de moi, dans mon entourage proche, même si on a depuis longtemps cessé de me le dire, pour certains – mes amis juifs naturellement en particulier –, ce choix n’en continue pas moins à faire problème. Ils auraient préféré que je m’attache à un autre auteur. Entre eux et moi, par intermittence, à l’occasion d’une nouvelle publication par exemple, je sens passer une onde à peine perceptible de gêne. » Et les choses vont parfois plus loin comme lorsque l’un de ses pairs l’accuse de complaisance envers l’écrivain ³.

Henri Godard n’écrira plus sur Céline. Il considère qu’il a dit sur le sujet tout ce qu’il avait à dire. Il n’était que temps de lui rendre hommage et de lui exprimer notre gratitude. En publiant la transcription d’un des plus intéressants entretiens qu’il ait donnés à la presse radiophonique. Plus loin, deux céliniens de la nouvelle génération saluent avec reconnaissance leur aîné tandis que Jean-Paul Louis, avec lequel il fonda la revue L’Année Céline, explique pertinemment en quoi son travail d’éditeur dans la Pléiade est digne de tous les éloges.

Henri Godard n’écrira plus sur Céline. Il considère qu’il a dit sur le sujet tout ce qu’il avait à dire. Il n’était que temps de lui rendre hommage et de lui exprimer notre gratitude. En publiant la transcription d’un des plus intéressants entretiens qu’il ait donnés à la presse radiophonique. Plus loin, deux céliniens de la nouvelle génération saluent avec reconnaissance leur aîné tandis que Jean-Paul Louis, avec lequel il fonda la revue L’Année Céline, explique pertinemment en quoi son travail d’éditeur dans la Pléiade est digne de tous les éloges.

Ce passionné de littérature n’a jamais méconnu le pamphlétaire intraitable que fut Céline. En revanche il s’est toujours insurgé lorsque certains voulaient le repeindre en « un second Drumont », c’est-à-dire « un individu qui n’[aurait] jamais pensé qu’à propager son credo raciste, utilisant à l’occasion pour cela la voie indirecte ou camouflée du roman 4. » C’est tout l’honneur d’Henri Godard d’avoir défendu l’écrivain malgré les préventions, les embûches et les dénigreurs de tout acabit.

05:24 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, revue, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, céline, henri godard |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://www.lefigaro.fr

FIGAROVOX/GRAND ENTRETIEN - Kévin Boucaud-Victoire présente dans un essai passionnant les multiples facettes de l'oeuvre de George Orwell.

Kévin Boucaud-Victoire est journaliste et essayiste. Il vient de publier Orwell, écrivain des gens ordinaires (Première Partie, 2018).

FIGAROVOX.- Vous consacrez un petit essai à George Orwell. Celui-ci est souvent résumé à ses deux classiques: La Ferme des animaux (1945) et 1984 (1949). Est-ce réducteur? Pour vous, Orwell est le plus grand écrivain politique du XXe siècle. Pourquoi?

Kévin BOUCAUD-VICTOIRE.- George Orwell reste prisonnier de ses deux derniers grands romans. Il faut dire qu'avant La Ferme des animaux, l'écrivain a connu échec sur échec depuis 1933 et la sortie de Dans la dèche à Paris et à Londres. Il y a plusieurs raisons à cela. Déjà, Orwell tâtonne pour trouver son style, et bien qu'intéressants, ses premiers écrits sont parfois un peu brouillons. Ensuite ses deux premiers grands essais politiques, Le quai de Wigan (1937) et Hommage à la Catalogne (1938) sont très subversifs. La seconde partie du premier est une critique impitoyable de son camp politique. Il reproche à la gauche petite bourgeoise son mépris implicite des classes populaires, son intellectualisme et son idolâtrie du progrès. Au point que son éditeur Victor Gollancz ne voulait au départ pas publier le livre d'Orwell avec cette partie, qu'il ne lui avait pas commandée. Hommage à la Catalogne dénonce le rôle des communistes espagnols durant la révolution de 1936. Il est alors victime d'une intense campagne pour le discréditer et doit changer d'éditeur pour le publier. À sa mort en 1950, les 1 500 ouvrages imprimés ne sont pas écoulés. Il a d'ailleurs aussi beaucoup de mal à faire publier La Ferme des animaux au départ. Ces deux ouvrages essentiels sont encore trop mal connus aujourd'hui. Je ne parle même pas de ses nombreux articles ou petits essais qui précisent sa pensée ou Un peu d'air frais, mon roman préféré d'Orwell, publié en 1939.

Sinon, l'Anglais a voulu faire de l'écriture politique une nouvelle forme d'art, à la fois esthétique, simple et compréhensible de tous. Aucun roman selon moi n'a eu au XXe siècle l'impact politique de 1984 et La Ferme des animaux. C'est ce qui explique qu'il a été ensuite, et très tôt après sa mort, récupéré par tout le monde, même ceux qu'il considérait comme ses adversaires politiques.

Vous jugez que l'utilisation qui est faite d'Orwell est une récupération politique?

Tout le monde est orwellien !

«Tout ce que j'ai écrit de sérieux depuis 1936, chaque mot, chaque ligne, a été écrit, directement ou indirectement, contre le totalitarisme et pour le socialisme démocratique tel que je le conçois», écrit en 1946 Orwell dans un court essai intitulé Pourquoi j'écris? Mais il a surtout été connu pour ses deux romans qui attaquent frontalement le totalitarisme. À partir de là, libéraux et conservateurs avaient un boulevard pour le récupérer. Ainsi, en pleine guerre froide, la CIA a produit une bande-dessinée et un dessin-animé de La Ferme des animaux, parfois en déformant légèrement son propos, diffusés un peu partout dans le monde. L'objectif était alors de stopper l'avancée du communisme dans le monde.

Depuis quelques années, «Orwell est invité à toutes les tables», comme l'explique le journaliste Robin Verner dans un excellent article pour Slate.fr. De l'essayiste Laurent Obertone à l'ENA, tout le monde est orwellien! Les récupérations ne sont pas que l'œuvre de la droite. Ainsi, depuis deux ou trois ans, Laurent Joffrin, directeur de la rédaction de Libération, s'est fait le héraut de la réhabilitation d'un Orwell de gauche. Pourtant, il a tout du prototype de la gauche petite bourgeoise sur laquelle a vomi l'écrivain dans Le Quai de Wigan, particulièrement dans les chapitres X à XIII.

Mais si Orwell est aussi récupérable c'est parce que la vérité était pour lui prioritaire, plus que l'esprit de camp politique. «L'argument selon lequel il ne faudrait pas dire certaines vérités, car cela “ferait le jeu de” telle ou telle force sinistre est malhonnête, en ce sens que les gens n'y ont recours que lorsque cela leur convient personnellement», écrit-il. «La liberté, c'est la liberté de dire que deux et deux font quatre. Lorsque cela est accordé, le reste suit», pouvons-nous lire aussi dans 1984. Après, je ne fais pas parler les morts, mais je doute qu'Orwell se serait insurgé contre le fait d'être cité par des adversaires politiques, lui qui avait des amis conservateurs ou libéraux.

Orwell n'est donc ni conservateur, ni socialiste?

On peut déjà relever qu'à partir de 1936, il s'est réclamé du socialisme démocratique plus d'une fois dans ses écrits. Malgré des penchants parfois conservateurs, il a aussi récusé appartenir à ce camp. Il écrit dans Le lion et la licorne, son deuxième plus grand essai politique, que son patriotisme «n'a rien à voir avec le conservatisme. Bien au contraire, il s'y oppose, puisqu'il est essentiellement une fidélité à une réalité sans cesse changeante et que l'on sent pourtant mystiquement identique à elle-même».

Orwell est un socialiste qui apprécie les traditions, se veut patriote, anti-progressiste et très démocrate !

Effectivement, Orwell est très complexe et un peu inclassable. «Trop égalitariste et révolutionnaire pour être social-démocrate ou travailliste, mais trop démocrate et antitotalitaire pour être communiste ; trop lucide sur la réalité des rapports de force entre les hommes et entre les États pour être anarchiste, mais trop confiant dans la droiture et dans le refus de l'injustice parmi les gens ordinaires pour basculer comme tant d'autres dans le pessimisme conservateur», écrit Jean-Jacques Rosat, un des grands connaisseurs actuels de l'écrivain. Mais pour lui, «le véritable socialiste est celui qui souhaite - activement, et non à titre de simple vœu pieux - le renversement de la tyrannie» (Le Quai de Wigan) et c'est comme cela qu'il se définit. Mais c'est un socialiste qui apprécie les traditions, se veut patriote, anti-progressiste et très démocrate!