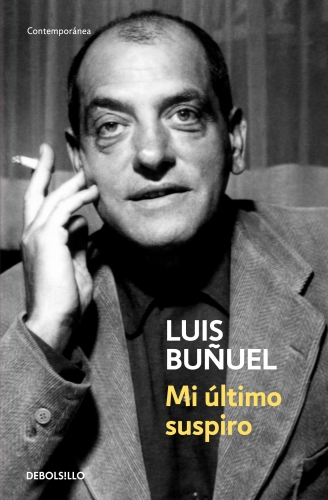

ALAIN SANTACREU : Je suis né à Toulouse, au mitan du dernier siècle. Mes parents étaient des ouvriers catalans, arrivés en France en 1939, en tant que réfugiés politiques. J’ai vécu toute mon enfance et mon adolescence dans cette ville. J’y ai fait mes études, depuis l’école des Sept-Deniers jusqu’à l’ancienne Faculté des Lettres de la rue des Lois, en passant par le lycée Pierre de Fermat et le lycée Nord. C’est au Conservatoire de Toulouse, dans la classe de Simone Turck, que j’ai commencé ma formation théâtrale.

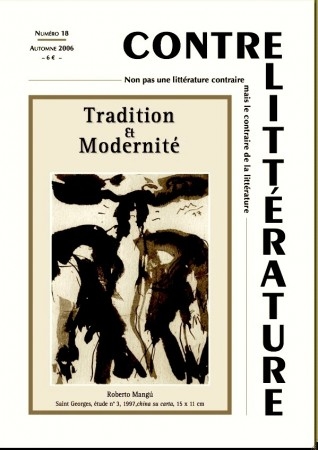

Je me suis marié très jeune et j’ai dû quitter Toulouse. Durant quelques années, j’ai joué dans diverses compagnies théâtrales de l’Est de la France. J’ai aussi été directeur d’un centre culturel, près de Belfort. Finalement, je suis devenu enseignant et j’ai exercé dans des établissements de la région parisienne. C’est au cours de cette période que j’ai écrit mes premiers textes et fondé la revue Contrelittérature. Par la suite mes activités éditoriales se sont diversifiées et, tout en publiant un premier roman et un recueil d’essais, j’ai dirigé plusieurs ouvrages collectifs sur l’art et la spiritualité, dans le cadre de la collection « Contrelittérature » aux éditions L’Harmattan. Quant à mon parcours intellectuel proprement dit, je l’aborderai en répondant à vos autres questions.

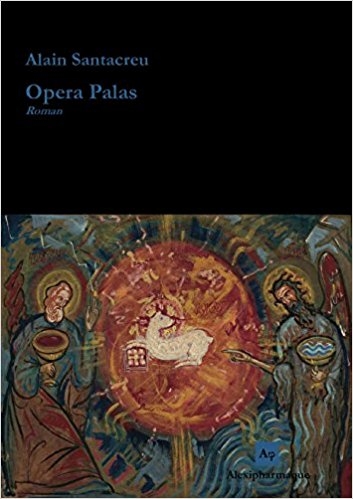

R/ Dans votre dernier roman Opera Palas vous placez le lecteur dans une posture opérative originale. Pensez-vous que le regard du lecteur « fait » vraiment un roman ?

R/ Dans votre dernier roman Opera Palas vous placez le lecteur dans une posture opérative originale. Pensez-vous que le regard du lecteur « fait » vraiment un roman ?

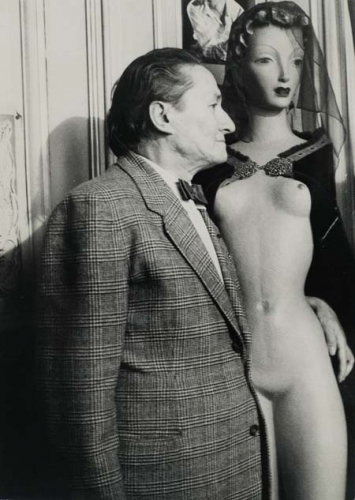

AS/ Toute la stratégie romanesque d’Opera Palas tourne autour de la phrase célèbre de Marcel Duchamp : « Ce sont les regardeurs qui font les tableaux ». C’est un commentaire qu’il a prononcé à propos de ses ready-made [1]. On sait que le ready made inventé par Duchamp est un vulgaire objet préfabriqué, prêt à l’emploi, comme son célèbre urinoir, « Fontaine », devenu un chef-d’oeuvre de l’art du XXe siècle.

Toute oeuvre d’art a deux pôles : le pôle de celui qui fait l’oeuvre et le pôle de celui qui la regarde. Dans le ready made, l’artiste s’efface du pôle créatif puisqu’il ne réalise pas l’objet « tout fait » qu’il donne à voir. Dès lors, la production de l’oeuvre ne dépend plus que du second pôle, du regardeur, celui de la réception. Ainsi, le ready made de Duchamp démontre que le goût esthétique n’est que la projection de l’ego du regardeur sur l’oeuvre.

Le spectacle – ce que j’appelle « littérature », comme j’aurai l’occasion de l’expliciter – est le pouvoir qui veut que je tienne mon rôle dans le jeu social dont il est l’unique metteur en scène. S’opposer à la volonté du spectacle, c’est donc mourir à soi-même, renoncer à ce faisceau de rôles qui me constitue, devenir réfractaire à cette image que la société me renvoie. Un texte signé Alaric Levant, paru récemment sur votre site internet, affirme que ce travail sur soi est un acte révolutionnaire : « Aujourd’hui, nous sommes face à une barricade bien plus difficile à franchir que celle des CRS : c’est l’Ego, c’est-à-dire la représentation que l’on a de soi-même »[2].

La démarche de Duchamp vise à nous extraire de la perspective spectaculaire, en cela elle annonce le situationnisme, la dernière avant-garde artistique et politique qui se soit manifestée dans notre société contemporaine. Le pouvoir du regardeur de décider si une pissotière est une oeuvre d’art est factice ; en réalité, c’est dans les coulisses que le meneur du spectacle décide de la seule norme esthétique qui puisse me faire exister au regard des autres.

Ainsi, les œuvres de l’art fonctionnent comme un immense kaléidoscope de miroirs que le regardeur manipule afin de customiser l’image qu’il a de lui-même. Plus encore : pour la pensée aliénée toute chose n’est que ready-made, marchandise « prête à l’emploi ». Votre goût esthétique est tout simplement le signe que vous êtes un moderne comme tout le monde. Si vous voulez être intégré dans le spectacle, vous devez vous conformer à l’exercice obligatoire de la différenciation mimétique – pour le dire à la manière de René Girard – de façon à vous assurer que vous appartenez bien à la classe de loisir – pour le dire à la manière de Thorstein Veblen.

Opera Palas est l’équivalent contre-littéraire du ready-made duchampien. Marcel Duchamp est un protagoniste du roman et son oeuvre maîtresse, La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même – aussi appelée Le Grand verre – est l’élément déclencheur du récit. La vanité de vouloir jouer un rôle dans la société du spectacle, la quête du succès et son obtention, Duchamp les a analysées dans son oeuvre majeure.

En lisant, le lecteur est renvoyé à son propre acte interprétatif, le roman est le miroir de sa pensée. Cela est rendu possible parce que le moi du narrateur anonyme du roman s’efface au fur et à mesure qu’avance le récit. En effet, une véritable opération alchimique se joue entre le narrateur et son double : Palas.

Le personnage de Palas est le nom générique de tous les lecteurs zélés d’Opera Palas. Il y a deux types possibles de lecteur. Le premier est celui qui se conforte dans la certitude de son moi, le lecteur aliéné qui réagit à partir du prêt-à-penser que la « littérature » lui a inculqué – pour celui-là, ce roman n’est pas un roman et il renoncera très vite à le lire ou même, sous l’emprise de son propre conditionnement idéologique, il l’interprètera comme antisémite, fasciste, homophobe ou conspirationniste. Le second type de lecteur est celui dont le zèle lui permet d’entrer en relation avec l’œuvre, d’établir un dialogue avec elle et de faire de sa lecture une opération de désaliénation de sa pensée. Le lecteur zélé accepte la mise en danger d’une lecture cathartique qui l’amène à oser se regarder lire.

Lorsque le lecteur referme Opera Palas, il prend conscience qu’il n’a fait qu’un tour sur lui-même, étant donné que la dernière page du roman est la description de l’icône qui illustre la couverture du livre. C’est alors qu’il peut traverser le miroir.

R/ Comment définir votre démarche de "Contre-Littérature" ?

R/ Comment définir votre démarche de "Contre-Littérature" ?

AS/ Le texte germinatif de la contrelittérature est Le manifeste contrelittéraire. Ce texte est d’abord paru, en février 1999, dans le n°48 de la revue Alexandre dirigée par André Murcie ; puis, quelques mois plus tard, en postface de mon premier roman, Les sept fils du derviche, (Éditions Jean Curutchet, 1999). Par la suite, il sera repris et étayé dans l’ouvrage éponyme, paru en 2005 aux éditions du Rocher : La contrelittérature : un manifeste pour l’esprit. Dès le début, j’ai préféré lexicaliser le terme pour le différencier du mot composé « contre-littérature » déjà employé par la critique littéraire officielle.

La contrelittérature est donc née à la fin du XXe siècle, pendant cette période d’unipolarisation du monde dans laquelle Fukuyama disait voir la « fin de l’histoire ». L’idéologie postmoderne du consensus global a été façonnée, dès le XVIIIe, par une Weltanschauung qu’Alexis Tocqueville, dans L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution, nomme « l’esprit littéraire » de la modernité. En deux siècles, la littérature avait si intensément « homogénéisé » la pensée, qu’à l’orée du XXIe siècle, une pensée hétérogène, contradictoire, était presque devenue impensable ; d’où la nécessité d’inventer un néologisme pour désigner cet impensable, ce fut : « contrelittérature ».

Cela se fit à partir de la découverte de la logique du contradictoire de Stéphane Lupasco. Pour la contrelittérature, Stéphane Lupasco est un maillon d’une catena aurea qui se manifeste avec Héraclite et les présocratiques, en passant aussi, comme nous le verrons, par Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, un auteur très important dans ma démarche.

Il faut partir de la définition la plus large possible : la littérature, c’est non seulement le corpus de tous les récits à travers lesquels une civilisation se raconte, mais encore tous les textes poétiques où elle prend conscience de son propre être et cherche à le transformer. La littérature doit être perçue comme un organisme vivant, un système dynamique d’antagonismes, pour reprendre la terminologie lupascienne, dont la production dépend de deux sources d’inspiration contraires : une force « homogénéisante » en relation avec les notions d’uniformité, de conservation, de permanence, de répétition, de nivellement, de monotonie, d’égalité, de rationalité, etc. ; et, à l’opposé, une force « hétérogénéisante » en relation avec les notions de diversité, de différenciation, de changement, de dissemblance, d’inégalité, de variation, d’irrationnalité, etc. Ce principe d’antagonisme a été annihilé par la littérature moderne qui a imposé l’actualisation absolue de son principe d’homogénéisation et ainsi tenté d’effacer le pôle de son contraire, l’hétérogène « contrelittéraire ».

Tous les romans étaient devenus semblables, de plates « egobiographies » sans âme, il fallait verticaliser l’horizontalité carcérale à laquelle on voulait nous condamner, retrouver la sacralité de la vie contre sa profanation imposée. C’est pourquoi, dans une première phase, nous nous sommes attachés à valoriser l’impensé de la littérature, le récit mystique qui se fonde sur la désappropriation de l’ego. D’où la redécouverte du roman arthurien et de la quête du graal, la revisitation des grands mystiques de toutes sensibilités religieuses – par exemple le soufisme dans mon premier roman, Les sept fils du derviche. Cela a pu conforter l’image fausse d’une contrelittérature confite en spiritualité et se complaisant dans une forme d’ésotérisme. Très peu ont réellement perçu la dimension révolutionnaire de la contrelittérature.

Tous les romans étaient devenus semblables, de plates « egobiographies » sans âme, il fallait verticaliser l’horizontalité carcérale à laquelle on voulait nous condamner, retrouver la sacralité de la vie contre sa profanation imposée. C’est pourquoi, dans une première phase, nous nous sommes attachés à valoriser l’impensé de la littérature, le récit mystique qui se fonde sur la désappropriation de l’ego. D’où la redécouverte du roman arthurien et de la quête du graal, la revisitation des grands mystiques de toutes sensibilités religieuses – par exemple le soufisme dans mon premier roman, Les sept fils du derviche. Cela a pu conforter l’image fausse d’une contrelittérature confite en spiritualité et se complaisant dans une forme d’ésotérisme. Très peu ont réellement perçu la dimension révolutionnaire de la contrelittérature.

La contrelittérature est une tentative pour redynamiser le système antagoniste de la littérature. Il est évident que ce point d’équilibre des deux sources d’inspiration exerce une attraction sur tous les « grands écrivains ». Leurs oeuvres contiennent les deux antagonismes dans des proportions différentes mais tournent toutes autour de ce « foyer » de mise en tension. Il serait stupide de se demander si un écrivain est « contrelittéraire ». Toute création contient nécessairement à la fois des éléments littéraires et contrelittéraires. C’est le quantum antagoniste qui varie, c’est-à-dire le point de la plus haute tension entre les antagonismes constitutifs de l’oeuvre.

On ne peut percevoir la liberté qu’en surplomblant les contraires, en les envisageant ensemble, d’un seul regard, sans en exclure un au bénéfice de l’autre. Telle est la perpective romanesque d’Opera Palas. Mon roman se construit en effet sur une série d’antagonismes. J’en citerai quelques-uns : la cabale de la puissance et la cabale de l’amour, le bolchévisme stalinien et le slavophilisme de Khomiakov, le sionisme de Buber et le sionisme de Jabotinsky, l’individu (le moi) et la commune (le non-moi, le je collectif) ; le nationalisme politique et le nationalisme de l’intériorité, l’éros et l’agapé ; sans oublier, pour finir, le couplage scandaleux entre Buenaventura Durruti et José Antonio Primo de Rivera, les ennemis politiques absolus.

Ainsi, la contrelittérature reprend le projet fondamental du Manifeste du Surréalisme d’André Breton, à partir du point où les surréalistes l’ont abandonné en choisissant le stalinisme : « Tout porte à croire qu'il existe un certain point de l’esprit d'où la vie et la mort, le réel et l'imaginaire, le passé et le futur, le communicable et l'incommunicable, le haut et le bas cessent d’être perçus contradictoirement. Or c'est en vain qu'on chercherait à l'activité surréaliste un autre mobile que l'espoir de détermination de ce point. »

Le plus haut drame de l’homme, ce n’est pas tant To be or not to be mais bien plutôt To be and not to be. La vraie quête initiatique est celle de ce point d’équilibre entre l’être et le non-être, c’est cela le grand retour du tragique, un lieu où la tension entre les contraires est si intense que nous passons sur un autre plan : un saut de réalité où les contraires entrent en dialogue.

R/ Votre démarche se rapproche pour moi de l'ABC de la lecture d'Ezra Pound. Ce prodigieux poète est-il une influence pour vous ?

AS/ L’ABC de la lecture est un génial manuel de propédeutique à l’usage des étudiants en littérature. On y trouve des réflexions d’une clarté fulgurante, telle cette phrase qui vous plonge dans un puits de lumière : « Toute idée générale ressemble à un chèque bancaire. Sa valeur dépend de celui qui le reçoit. Si M. Rockefeller signe un chèque d’un million de dollars, il est bon. Si je fais un chèque d’un million, c’est une blague, une mystification, il n’a aucune valeur. » [3]

On voit que, pour Ezra Pound aussi, c’est le récepteur qui accorde son crédit à l’émetteur. Si un milliardaire émet un gros chèque, le récepteur l’estime tout de suite valable ; mais, par contre, si le même chèque est émis par un vulgaire péquenot, ce n’est pas crédible. On retrouve ici l’interrogation de la pissotière de Duchamp, qu’est-ce qui en fait une oeuvre d’art pour le regardeur ?

Bien sûr, ce n’est pas exactement ce que veut signifier Pound dans cette phrase de son ABC de la lecture mais je l’ai citée à cause de son allusion « économique », thème prégnant dans d’autres de ses ouvrages. Je pense à un livre comme Travail et usure ou encore au Canto XLV.

Ezra Pound est un des grands prédécesseurs de la contrelittérature. C’est à partir de lui que j’ai compris la similarité du processus d’homogénéisation de la littérature avec celui de l’usure. Pound a perçu de façon très subtile le phénomène de l’ « argent fictif ». Il insiste dans ses écrits sur la constitution et le développement de la Banque d’Angleterre, modèle du système bancaire moderne né en pays protestant où l’usure avait été autorisée par Élisabeth Tudor en 1571.

Ezra Pound est un des grands prédécesseurs de la contrelittérature. C’est à partir de lui que j’ai compris la similarité du processus d’homogénéisation de la littérature avec celui de l’usure. Pound a perçu de façon très subtile le phénomène de l’ « argent fictif ». Il insiste dans ses écrits sur la constitution et le développement de la Banque d’Angleterre, modèle du système bancaire moderne né en pays protestant où l’usure avait été autorisée par Élisabeth Tudor en 1571.

Pour comprendre la nature métaphysique du sacrilège qu’Ezra Pound dénonce sous le concept d’usure, il faudrait se reporter au onzième chant de L’Enfer de Dante – La Divine Comédie est une référence constante dans Les Cantos – qui condamne en même temps les usuriers et les sodomites pour avoir péché contre la bonté de la nature (« spregiando natura e sua bontade »). J’ai moi-même repris ce parallèle dans mon roman Opera Palas en relevant la synchronicité, durant la seconde partie du XVIIIe siècle, de l’émergence des clubs d’homosexuels – équivalents des molly houses – avec l’officialisation de l’usure bancaire – décret du 12 octobre 1789 autorisant le prêt à intérêt.

C’est en 1787, dans ses Éléments de littérature, que François de Marmontel utilisa pour la première fois le terme « littérature » au sens moderne. Il ne me semble pas que ce phénomène de la concomitance entre la littérature et l’usure ait jamais été pris en compte ni étudié avant la contrelittérature [4].

Le concept poundien d’Usura ne se laisse pas circonscrire aux seuls effets de l’économie capitaliste. Dans la société contemporaine globalisée, tous les signes sont devenus des métonymies du signe monétaire, à commencer par les mots de la langue, arbitraires et sans valeur.

L’usure littéraire consiste à vider les mots de leur sens pour leur prêter un sens abstrait. Usura entraîne le progrès de l’abstraction, c’est-à-dire de la séparation – en latin abstrahere signifie retirer, séparer. Usura ouvre le monde de la réalité virtuelle et referme celui de la présence réelle. Par l’usure, l’homme se retrouve séparé du monde.

Durant l’été 1912, Ezra Pound parcourut à pied les paysages du sud de la France, sur les pas des troubadours, afin de s’incorporer les lieux topographiques du jaillissement de la langue d’oc. La poésie poundienne est un combat contre l’usure. Chaque point de l’espace devient un omphalos, un lieu d’émanation du verbe, chaque pas une station hiératique. Ainsi est dépassée l’entropie littéraire du mot, l’érosion du sens par l’usure répétitive.

Ce que Pound, lecteur de Dante, nomme « Provence », correspond géographiquement à l’Occitanie et à la Catalogne. Ce pays évoquait pour lui une civilisation médiévale de l’amour qui s’oppose au capitalisme moderne. L’amour est le contraire de l’usure.

Cependant, Pound n’a pas su reconnaître la surrection du catharisme des troubadours dans l’anarchisme espagnol, ce que Gerald Brenan a très bien vu dans son Labyrinthe espagnol [5]. J’ai soutenu dans Opera Palas cette vision millénariste de la révolution sociale espagnole.

Cependant, Pound n’a pas su reconnaître la surrection du catharisme des troubadours dans l’anarchisme espagnol, ce que Gerald Brenan a très bien vu dans son Labyrinthe espagnol [5]. J’ai soutenu dans Opera Palas cette vision millénariste de la révolution sociale espagnole.

À mes yeux, la véritable trahison politique d’Ezra Pound ne se trouve pas tant dans les causeries qu’il donna sur Radio Rome, entre 1936 et 1944, la plupart consacrées à la littérature et à l’économie, mais dans son aveuglement face à ce moment métahistorique que fut la guerre d’Espagne. Comment n’a-t-il pas vu qu’Usura n’était plus dans les collectivités aragonaises et les usines autogérées de Catalogne ? Comment n’a-t-il pas entendu d’où soufflait le vent du romancero épique, la poésie de Federico García Lorca, d’Antonio Machado, de Rafael Alberti, de Miguel Hernández?

R/ La notion de tradition apparaît dans vos écrits depuis l’origine. Quelle définition en donneriez-vous ? Quel est votre rapport à l’oeuvre de Guénon ?

AS/ Selon moi, le paradigme essentiel de la tradition réside dans la notion d’anthropologie ternaire, tout le reste n’est que littérature ésotérique.

Jusqu’à la fin de la période romane, soit l’articulation des XIIe et XIIIe siècles, la « tripartition anthropologique » a été la référence de notre civilisation chrétienne occidentale [6]. La structure trinitaire de l’homme – Corps-Âme-Esprit – fut simultanément transmise à la « science romane » par les sources grecque et hébraïque. Sans doute, le ternaire grec, « soma-psyché-pneuma », ne correspond-il pas exactement au ternaire hébreu, « gouf-nephesh-rouach », mais les deux se fondent sur une tradition fondamentale qui inclut le spirituel dans l’homme.

Dieu est immanent à l’esprit, mais il est transcendant à l’homme psycho-corporel, telle est l’aporie devant laquelle nous place cette « tradition primordiale » dont parle René Guénon. L’esprit n’est pas humain mais divino-humain ; ou, plus précisément, il est le lieu de la rencontre entre la nature divine et la nature humaine. Il n’y a pas de vie spirituelle sans Dieu et l’homme. C’est comme faire l’amour : il faut être deux ! C’est pourquoi une « spiritualité » laïque ne sera jamais qu’un onanisme de l’esprit.

Cette tradition dialogique entre l’incréé et le créé m’évoque le mot principe « Je-Tu » de Martin Buber. L’existence humaine se joue, selon Buber, entre deux mots principes qui sont deux relations antagonistes : « Je-Tu » et « Je-Cela ». Le mot-principe Je-Tu ne peut être prononcé que par l’être entier mais, au contraire, le mot-principe Je-Cela ne peut jamais l’être : « Dire Tu, c’est n’avoir aucune chose pour objet. Car où il y a une chose, il y a autre chose ; chaque Cela confine à d’autres Cela. Cela n’existe que parce qu’il est limité par d’autres Cela. Mais là où l’on dit Tu, il n’y a aucune chose. Tu ne confine à rien. Celui qui dit Tu n’a aucune chose, il n’a rien. Mais il est dans la relation. » [7]

Cette tradition dialogique entre l’incréé et le créé m’évoque le mot principe « Je-Tu » de Martin Buber. L’existence humaine se joue, selon Buber, entre deux mots principes qui sont deux relations antagonistes : « Je-Tu » et « Je-Cela ». Le mot-principe Je-Tu ne peut être prononcé que par l’être entier mais, au contraire, le mot-principe Je-Cela ne peut jamais l’être : « Dire Tu, c’est n’avoir aucune chose pour objet. Car où il y a une chose, il y a autre chose ; chaque Cela confine à d’autres Cela. Cela n’existe que parce qu’il est limité par d’autres Cela. Mais là où l’on dit Tu, il n’y a aucune chose. Tu ne confine à rien. Celui qui dit Tu n’a aucune chose, il n’a rien. Mais il est dans la relation. » [7]

Cependant, si Buber oppose ainsi le monde du Cela au monde du Tu, il ne méprise pas pour autant un monde au détriment de l’autre. Il met en évidence leur nécessaire antagonisme. L’homme ne peut vivre sans le Cela mais, s’il ne vit qu’avec le Cela, il ne peut réaliser sa vocation d’homme, il demeure le « Vieil homme » et sa misérable vie, dénuée de la Présence réelle, l’ensevelit dans une réalité irreliée.

À l’intérieur de la relation du mot principe « Je-Tu », nous rentrons dans l’ordre du symbole. Le symbole est un langage qui nous permet de saisir l’immanence de la transcendance. Il n’est pas une représentation, il réalise une présence. La Présence divine ne peut être représentée, elle est toujours là.

L’effacement de la conception tripartite de l’homme correspond à la période liminaire de la mécanisation moderne de la technique. Le XIIIe siècle marque ce point d’inflexion du passage à la modernité. C’est durant la crise du XIIIe siècle, comme l’a appelée Claude Tresmontant [8], que la pensée du signe va remplacer la pensée du symbole. Le mot pour l’esprit bourgeois n’est pas l’expression du Verbe, il est un signe arbitraire qui lui permet de désigner l’avoir, la marchandise.

La logique du symbole est une logique du contradictoire. René Guénon, dans un de ses articles [9], affirme qu’un même symbole peut être pris en deux sens qui sont opposés l’un à l’autre. Les deux aspects antagoniques du symbole sont liés entre eux par un rapport d’opposition, si bien que l’un d’eux se présente comme l’inverse, le « négatif » de l’autre. Ainsi, nous retrouvons dans la structure du symbole ce point de passage, situé hors de l’espace-temps, en lequel s’opère la transformation des contraires en complémentaires.

La découverte de l’oeuvre de René Guénon a été décisive dans mon cheminement. Mes parents étaient des anarchistes espagnols et j’ai lu Proudhon, Bakounine et Kropotkine bien avant de lire Guénon. C’est la lecture de René Guénon qui m’a permis de me libérer de la pesanteur de l’idéologie anarchiste.

La découverte de l’oeuvre de René Guénon a été décisive dans mon cheminement. Mes parents étaient des anarchistes espagnols et j’ai lu Proudhon, Bakounine et Kropotkine bien avant de lire Guénon. C’est la lecture de René Guénon qui m’a permis de me libérer de la pesanteur de l’idéologie anarchiste.

Toute erreur moderne n’est que la négation d’une vérité traditionnelle incomprise ou défigurée. Au cours de l’involution du cycle, le rejet d’une grille de lecture métaphysique du monde a provoqué la subversion de l’idée acrate, si chère à Jünger, et sa transformation en idéologie anarchiste. La négation des archétypes inversés de la bourgeoisie, à laquelle s’est justement livrée la révolte anarchiste ne pouvait qu’aboutir à un nihilisme indéfini, puisque son apriorisme idéologique lui interdisait la découverte des « archés » véritables. Cette incapacité fut l’aveu de son impuissance spirituelle à dépasser le système bourgeois. La négation du centre, perçu comme principe de l’autorité, au bénéfice d’une périphérie présupposée non-autoritaire, est l’expression d’une pensée dualiste dont la bourgeoisie elle-même est issue. La logique du symbole transmise par René Guénon ouvre une autre perspective où la tradition se conjugue à la révolution.

R/ Vous avez croisé la route de Jean Parvulesco. Pouvez-vous revenir sur cette personnalité flamboyante qui fut un ami fidéle de Rébellion ?

AS/ Jean Parvulesco et moi ne cheminions pas dans le même sens et nous nous sommes croisés, ce fut un miracle dans ma vie. Il est la plus belle rencontre que j’ai faite sur la talvera. Savez-vous ce qu’est la talvera ?

Les paysans du Midi appellent « talvera » cette partie du champ cultivé qui reste éternellement vierge car c’est l’espace où tourne la charrue, à l’extrémité de chaque raie labourée. Le grand écrivain occitan Jean Boudou a écrit un poème intitulé La talvera où l’on trouve ce vers admirable : « C’est sur la talvera qu’est la liberté » (Es sus la talvèra qu’es la libertat).

Mon intérêt pour la notion de talvera a été suscité par la lecture du sociologue libertaire Yvon Bourdet [10]. La talvera est l’espace du renversement perpétuel du sens, de sa reprise infinie, de son éternel retournement. Elle est la marge nécessaire à la recouvrance du sens perdu, à l’orientation donnée par le centre. Loin de nier le centre, la talvera le rend vivant. La conscience de la vie devenue de plus en plus périphérique, notre aliénation serait irréversible s’il n’y avait un lieu pour concevoir la rencontre, un corps matriciel où l’être, exilé aux confins de son état d’existence, puisse de nouveau se trouver relié à son principe. Sur la talvera se trouve l’éternel féminin de notre liberté, cette dimension mariale que Jean Parvulesco vénérait tant. C’est là que nous nous sommes rencontrés.

Mon intérêt pour la notion de talvera a été suscité par la lecture du sociologue libertaire Yvon Bourdet [10]. La talvera est l’espace du renversement perpétuel du sens, de sa reprise infinie, de son éternel retournement. Elle est la marge nécessaire à la recouvrance du sens perdu, à l’orientation donnée par le centre. Loin de nier le centre, la talvera le rend vivant. La conscience de la vie devenue de plus en plus périphérique, notre aliénation serait irréversible s’il n’y avait un lieu pour concevoir la rencontre, un corps matriciel où l’être, exilé aux confins de son état d’existence, puisse de nouveau se trouver relié à son principe. Sur la talvera se trouve l’éternel féminin de notre liberté, cette dimension mariale que Jean Parvulesco vénérait tant. C’est là que nous nous sommes rencontrés.

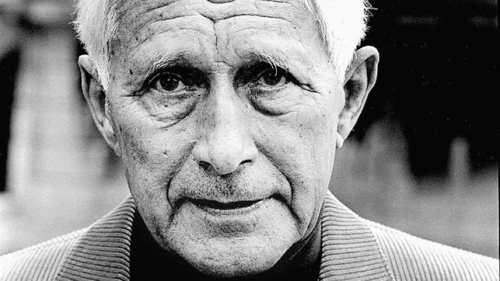

Jean Parvulesco était un « homme différencié », au sens où l’entendait Julius Evola. Il appartenait à cette race spirituelle engagée dans un combat apocalyptique contre la horde des « hommes plats ». Ce fut le dernier « maître de la romance ». Il est l’actualisation absolue de la contrelittérature. C’est-à-dire que Parvulesco inverse totalement le rapport littérature-contrelittérature. Son oeuvre à contre-courant potentialise l’horizontalité littéraire et actualise la verticalité contrelittéraire, pour employer la terminologie de Lupasco. D’un certain point de vue, Jean Parvulesco incarne le contraire de la littérature.

Je comprends aujourd’hui combien ma rencontre avec Parvulesco a été cruciale. Si notre éloignement m’est apparu comme une nécessité, j’ai su intérioriser sa présence, la rendre indispensable à ma propre démarche.

J’ai relu l’autre jour le texte qui a été la cause de notre séparation. C’était durant l’hiver 2002, son article s’intitulait « L’autre Heidegger » et aurait dû paraître dans le n° 8 de la revue Contrelittérature mais j’ai osé le lui refuser [11]. Parvulesco s’y interroge sur la véritable signification de l’œuvre d’Heidegger. Il soutient que la philosophie n’était qu’un moyen pour dissimuler un travail initiatique qu’Heidegger menait sur lui-même et qui se poursuivit jusqu’à son appel à la poésie d’Hölderlin, ultime phase de son oeuvre que Parvulesco nomme son « irrationalisme dogmatique ».

Or, ma démarche se résume à cette quête du point d’équilibre entre le rationalisme dogmatique des Lumières et l’irrationalisme dogmatique des anti-Lumières, ce point de la plus haute tension entre la littérature et la contrelittérature, alors que Jean Parvulesco incarnait le pôle contrelittéraire absolu.

On ne lit pas Jean Parvulesco sans crainte ni tremblement : la voie chrétienne qui s’y découvre est celle de la main gauche, un tantrisme marial aux limites de la transgression dogmatique. Son style crée dans notre langue française une langue étrangère au phrasé boréal. Mon ami, le romancier Jean-Marc Tisserant, qui l’admirait, me disait que Parvulesco était l’ombre portée de la contrelittérature en son midi : « Vous ne parlez pas de la même chose ni du même lieu », me confia-t-il lors de la dernière conversation que j'eus avec lui. Il est vrai que Parvulesco, à partir de notre séparation, a choisi d’orthographier « contre-littérature », en mot composé – sauf dans le petit ouvrage, Cinq chemins secrets dans la nuit, paru en 2007 aux éditions DVX, qu'il m'a dédié ainsi : « Pour Alain Santacreu et sa contrelittérature ».

On ne lit pas Jean Parvulesco sans crainte ni tremblement : la voie chrétienne qui s’y découvre est celle de la main gauche, un tantrisme marial aux limites de la transgression dogmatique. Son style crée dans notre langue française une langue étrangère au phrasé boréal. Mon ami, le romancier Jean-Marc Tisserant, qui l’admirait, me disait que Parvulesco était l’ombre portée de la contrelittérature en son midi : « Vous ne parlez pas de la même chose ni du même lieu », me confia-t-il lors de la dernière conversation que j'eus avec lui. Il est vrai que Parvulesco, à partir de notre séparation, a choisi d’orthographier « contre-littérature », en mot composé – sauf dans le petit ouvrage, Cinq chemins secrets dans la nuit, paru en 2007 aux éditions DVX, qu'il m'a dédié ainsi : « Pour Alain Santacreu et sa contrelittérature ».

J’ai repris dans le texte de mon roman, pour les trois seules occurrences où le mot apparaît, cette graphie « contre-littérature ». Ce mot désignait à ses yeux le combat pour l’être. Oui, finalement, la seule réalité qui vaille, c’est la réalité de ce combat. Il ne faut pas refuser de se battre, si l’on veut vaincre les forces antagonistes !

Ma rencontre avec Jean Parvulesco n’a pas été une « mérencontre », pour reprendre l’expression de Martin Buber, c’est-à-dire une rencontre qui aurait dû être et ne se serait pas faite. Notre rencontre a bien eu lieu, je l’ai compris en écrivant mon roman : Opera Palas, c’est l’accomplissement de ma rencontre avec Jean Parvulesco.

R/ Pour vous, comme pour Orwell, l’histoire s’arrête en 1936. Pourquoi ? Vous évoquez dans votre roman l’expérience de l’anarcho-syndicalisme de la CNT-AIT espagnole. Cette vision fédéraliste et libertaire est-elle la voie pour sortir de l’Âge de fer capitaliste ?

AS/ Comment faire pour s’extraire de l’« Âge de fer » capitaliste ? Alexandre Douguine [12] pense qu’il faut partir de la postmodernité – cette période qui, selon Francis Fukuyama, correspond à la « fin de l’histoire » – mais il commet une erreur de perspective : il faut partir du moment où l’histoire s’est arrêtée.

Selon Douguine, la chute de Berlin, en 1989, marque l’entrée de l’humanité dans l’ère postmoderne. La dernière décennie du XXe siècle aurait vu la victoire de la Première théorie politique de la modernité, le libéralisme, contre la Deuxième, celle du communisme – la Troisième théorie politique, le fascisme, ayant disparu avec la défaite du nazisme.

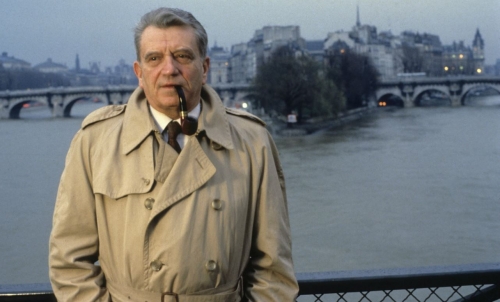

Je ne partage pas ce point de vue. Il n’y a pas eu de victoire de la Première théorie sur la Deuxième mais une fusion des deux dans un capitalisme d’État mondialisé. La postmodernité est anhistorique parce que l’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. C’est cela que j’ai voulu montrer avec Opera Palas. Le prétexte de mon roman est une phrase de George Orwell « Je me rappelle avoir dit un jour à Arthur Koestler : L’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. » Orwell écrit ces mots en 1942, dans un article intitulé « Looking Back on the Spanish War » (Réflexions sur la guerre d’Espagne). Et il poursuit : « En Espagne, pour la première fois, j’ai vu des articles de journaux qui n’avaient aucun rapport avec les faits, ni même l’allure d’un mensonge ordinaire. » Ainsi, parce que la guerre d’Espagne marque la substitution du mensonge médiatique à la vérité objective, l’histoire s’arrête et la période postmoderne s’ouvre alors.

Je ne partage pas ce point de vue. Il n’y a pas eu de victoire de la Première théorie sur la Deuxième mais une fusion des deux dans un capitalisme d’État mondialisé. La postmodernité est anhistorique parce que l’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. C’est cela que j’ai voulu montrer avec Opera Palas. Le prétexte de mon roman est une phrase de George Orwell « Je me rappelle avoir dit un jour à Arthur Koestler : L’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. » Orwell écrit ces mots en 1942, dans un article intitulé « Looking Back on the Spanish War » (Réflexions sur la guerre d’Espagne). Et il poursuit : « En Espagne, pour la première fois, j’ai vu des articles de journaux qui n’avaient aucun rapport avec les faits, ni même l’allure d’un mensonge ordinaire. » Ainsi, parce que la guerre d’Espagne marque la substitution du mensonge médiatique à la vérité objective, l’histoire s’arrête et la période postmoderne s’ouvre alors.

En 1936, contrairement à l’information unanimement répercutée par toute la presse internationale, les ouvriers et paysans espagnols ne se soulevèrent pas contre le fascisme au nom de la « démocratie » ni pour sauver la République bourgeoise ; leur résistance héroïque visait à instaurer une révolution sociale radicale. Les paysans saisirent la terre, les ouvriers s’emparèrent des usines et des moyens de transports. Obéissant à un mouvement spontané, très vite soutenu par les anarcho-syndicalistes de la CNT-FAI, les ouvriers des villes et des campagnes opérèrent une transformation radicale des conditions sociales et économiques. En quelques mois, une révolution communiste libertaire réalisa les théories du fédéralisme anarchiste préconisées par Proudhon et Bakounine. C’est cette réalité révolutionnaire que la presse antifasciste internationale reçut pour mission de camoufler. Du côté franquiste, la presse catholique et fasciste se livra aussi à une intense propagande de désinformation. À Paris, à Londres, comme à Washington ou à Moscou, la communication de guerre passa par le storytelling, la « mise en récit » d’une histoire qui présentait les événements à la manière que l’on voulait imposer à l’opinion. L’alliance des trois théories politiques a voulu détruire en Espagne la capacité communalisante du peuple. Ce que le bolchévisme avait fait subir au peuple russe, il est venu le réitérer en toute impunité en Espagne. C’est pourquoi je fais dans mon roman un parallèle entre les deux événements métahistoriques du XXe siècle où l’âme « communiste » des peuples a été annihilée : Cronstadt, en 1921 et Barcelone, lors des journées sanglantes de mai 1937.

Cronstadt voulait faire revivre le mir (commune rurale) et l’artel (coopérative ouvrière). Supprimer le mir archaïque signifiait supprimer des millions de paysans, c’est ce que firent les bolchéviques, par le crime et la famine.

Comme en Russie, les bolchéviques furent les fossoyeurs de la révolution sociale espagnole. Il suffit pour s’en convaincre de lire Spain Betrayed de Ronald Radosh, Mary R. Habeck et Grigory Sevostianov, un ouvrage qui procède au dépouillement systématique des dernières archives consacrées à la guerre d’Espagne, ouvertes à Moscou (Komintern, Politburo, NKVD – police politique et GRU – service d’espionnage de l’armée) [13]. Ainsi, bien au contraire de ce que dit Alexandre Douguine, si l’on prend la Guerre d’Espagne comme point focal, on comprend qu’il n’y a pas eu combat mais connivence entre les trois théories politiques de la modernité.

La vision fédéraliste et libertaire reste la seule méthode de guérison pour ranimer la capacité communalisante du peuple et lui permettre de retrouver son instinct de solidarité et de liberté.

L’anarcho-syndicalisme de la CNT espagnole n’a pas réussi à s’extraire de l’idéologie anarchiste pour s’ouvrir à l’esprit traditionnel de l’idée libertaire. C’est justement cette opération utopique – ou plutôt uchronique – que tente de mettre en place un des protagonistes du roman : Julius Wood.

Opera Palas établit un couplage insensé entre Buenaventura Durruti et José Antonio Primo de Rivera, une mise en relation scandaleuse et paradoxale qui prend à revers la notion même du politique telle que la résume Carl Schmitt dans cette phrase : « La distinction spécifique du politique, à laquelle peuvent se ramener les actes et les mobiles politiques, c’est la distinction de l’ami et de l’ennemi. » [14]

Le fédéralisme proudhonien repose sur cette mise en dialectique des contraires. Dans la pensée de Proudhon, le passage de l’anarchisme au fédéralisme est lié à cette recherche d’un équilibre entre l’autorité et la liberté dont un État garant du contrat mutualiste doit préserver l’harmonie.

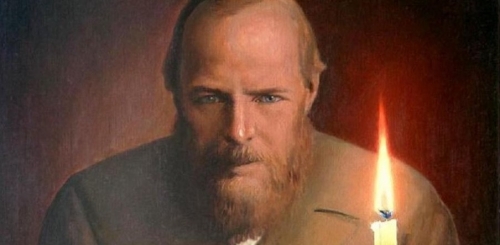

On se rappellera la légende du « Grand Inquisiteur » que Dostoïevski a enchâssée dans Les Frères Karamazov : le Christ réapparaît dans une rue de Séville, à la fin du XVe siècle et, le reconnaissant, le Grand Inquisiteur le fait arrêter. La nuit, dans sa geôle, il vient reprocher au Christ la « folie » du christianisme : la liberté pour l’homme de se déifier en se tournant vers Dieu.

On se rappellera la légende du « Grand Inquisiteur » que Dostoïevski a enchâssée dans Les Frères Karamazov : le Christ réapparaît dans une rue de Séville, à la fin du XVe siècle et, le reconnaissant, le Grand Inquisiteur le fait arrêter. La nuit, dans sa geôle, il vient reprocher au Christ la « folie » du christianisme : la liberté pour l’homme de se déifier en se tournant vers Dieu.

Dans ce récit se trouve la quintessence du mystère du socialisme. Choisir les idées du Grand inquisiteur, comme le fera Carl Schmitt [15], qui en cela se révèle non seulement catholique mais « marxiste », c’est le socialisme d’État ; Bakounine, lui, à l’image de Tolstoï, choisit le Christ contre l’État, et c’est le socialisme anarchiste. Dépasser la contradiction entre Schmitt et Bakounine par la dialectique proudhonienne, telle est la théorie politique de l’avenir.

______________________

NOTES

[1] Marcel Duchamp, Ingénieur du temps perdu, Belfond, 1977, p. 122.

[2] Alaric Levant, « Une révolution de l’intérieur… pour faire avancer notre idéal ? » : http://rebellion-sre.fr/revolution-de-linterieur-faire-av....

[3] Ezra Pound, ABC de la lecture, coll. « Omnia », Éditions Bartillat, 2011, p. 27.

[4] Cf. « Talvera et Usura » paru dans Contrelittérature n° 17, Hiver 2006. Texte repris et développé dans le recueil d’essais Au coeur de la talvera, Arma Artis, 2010.

[5] Gerald Brenan, Le labyrinthe espagnol. Origines sociales et politiques de la guerre civile, Éditions Ruedo Ibérico, 1962.

[6] Jean Borella, « La tripartition anthropologique », in La Charité profanée, Éditions du Cèdre/DMM, 1979, pp.117-133.

[7] Martin Buber, « Je et Tu » in La Vie en dialogue, Aubier 1968, p. 8.

[8] Claude Tresmontant, La métaphysique du christianisme et la crise du treizième siècle, Éditions du Seuil, 1964.

[9] René Guénon, « Le renversement des symboles » in Le Règne de la Quantité et les Signes des Temps, chap. XXX.

[10] Yvon Bourdet, L’espace de l’autogestion, Galilée, 1979.

[11] Cet article a été intégré dans l’ouvrage de Jean Parvulesco, La confirmation boréale, Alexipharmaque éditions, 2012, pp. 223-229.

[12] Alexandre Douguine, La Quatrième théorie politique, Ars Magna Éditions, 2012.

[13] Édité en 2001, aux éditions Yale University, l’ouvrage est paru en Espagnol, en 2002, sous le titre España traicionada, mais n’a toujours pas été traduit en français.

[14] Carl Schmitt, La notion du politique, Calmann-Lévy, 1972, note 1, p.

66.

[15] Cf. Théodore Paléologue, Sous l’œil du grand inquisiteur : Carl Schmitt et l'héritage de la théologie politique, Cerf, 2004.

Jünger constata que la tendencia a la estatización (a la “organización”) se hace más rara a medida que ascendemos en la escala de los animales superiores. En ellos –por ejemplo, en los lobos, en numerosos grupos de aves, etc.- es frecuente hallar ejemplos de socialización, pero muy rara vez asistiremos a los sacrificios que la estatización impone a los insectos. En ese sentido, el hombre ocupa un lugar especial: la estatización no es algo que le sea natural, aunque el proceso de desarrollo de la civilización técnica muestre claras tendencias estatizadoras. En el mundo natural, la tendencia hacia la organización es un rasgo específico de los animales sociales; en el caso de la especie humana, es el síntoma más evidente del avance del proceso de civilización. Y sin embargo, la tendencia a la organización no es inapelable, inevitable; ni siquiera natural. Ese es el sentido de la pregunta que Jünger se formula: ¿Acaso el mundo está lleno de organismos que esperan ser organizados y reivindican tal organización? No, e incluso lo contrario es lo cierto, pues por todas partes puede percibirse como actúa “la tentativa de sustraerse al poder”. De manera que la organización no es un hecho natural, o al menos no lo es más que la resistencia a la organización.

Jünger constata que la tendencia a la estatización (a la “organización”) se hace más rara a medida que ascendemos en la escala de los animales superiores. En ellos –por ejemplo, en los lobos, en numerosos grupos de aves, etc.- es frecuente hallar ejemplos de socialización, pero muy rara vez asistiremos a los sacrificios que la estatización impone a los insectos. En ese sentido, el hombre ocupa un lugar especial: la estatización no es algo que le sea natural, aunque el proceso de desarrollo de la civilización técnica muestre claras tendencias estatizadoras. En el mundo natural, la tendencia hacia la organización es un rasgo específico de los animales sociales; en el caso de la especie humana, es el síntoma más evidente del avance del proceso de civilización. Y sin embargo, la tendencia a la organización no es inapelable, inevitable; ni siquiera natural. Ese es el sentido de la pregunta que Jünger se formula: ¿Acaso el mundo está lleno de organismos que esperan ser organizados y reivindican tal organización? No, e incluso lo contrario es lo cierto, pues por todas partes puede percibirse como actúa “la tentativa de sustraerse al poder”. De manera que la organización no es un hecho natural, o al menos no lo es más que la resistencia a la organización.

« On peut dire que dans la ville où je suis né (22 février 1900) le Moyen Age a duré jusqu'à la Première Guerre mondiale. C'était une société isolée et immobile, dans laquelle les différences de classe étaient bien marquées. Le respect et la subordination des travailleurs aux grands seigneurs, aux propriétaires terriens, profondément enracinés dans les vieilles coutumes, semblaient immuables. La vie se développa, horizontale et monotone, définitivement ordonnée et dirigée par les cloches de l'église d'El Pilar. »

« On peut dire que dans la ville où je suis né (22 février 1900) le Moyen Age a duré jusqu'à la Première Guerre mondiale. C'était une société isolée et immobile, dans laquelle les différences de classe étaient bien marquées. Le respect et la subordination des travailleurs aux grands seigneurs, aux propriétaires terriens, profondément enracinés dans les vieilles coutumes, semblaient immuables. La vie se développa, horizontale et monotone, définitivement ordonnée et dirigée par les cloches de l'église d'El Pilar. » Comme Samuel Beckett alors (« nous sommes tous cons, mais pas au point de voyager », voyez mon Voyageur éveillé ou mon apocalypse touristique), Buñuel envoie digne promener le tourisme :

Comme Samuel Beckett alors (« nous sommes tous cons, mais pas au point de voyager », voyez mon Voyageur éveillé ou mon apocalypse touristique), Buñuel envoie digne promener le tourisme :

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

R/

R/  R/

R/ Tous les romans étaient devenus semblables, de plates « egobiographies » sans âme, il fallait verticaliser l’horizontalité carcérale à laquelle on voulait nous condamner, retrouver la sacralité de la vie contre sa profanation imposée. C’est pourquoi, dans une première phase, nous nous sommes attachés à valoriser l’impensé de la littérature, le récit mystique qui se fonde sur la désappropriation de l’ego. D’où la redécouverte du roman arthurien et de la quête du graal, la revisitation des grands mystiques de toutes sensibilités religieuses – par exemple le soufisme dans mon premier roman, Les sept fils du derviche. Cela a pu conforter l’image fausse d’une contrelittérature confite en spiritualité et se complaisant dans une forme d’ésotérisme. Très peu ont réellement perçu la dimension révolutionnaire de la contrelittérature.

Tous les romans étaient devenus semblables, de plates « egobiographies » sans âme, il fallait verticaliser l’horizontalité carcérale à laquelle on voulait nous condamner, retrouver la sacralité de la vie contre sa profanation imposée. C’est pourquoi, dans une première phase, nous nous sommes attachés à valoriser l’impensé de la littérature, le récit mystique qui se fonde sur la désappropriation de l’ego. D’où la redécouverte du roman arthurien et de la quête du graal, la revisitation des grands mystiques de toutes sensibilités religieuses – par exemple le soufisme dans mon premier roman, Les sept fils du derviche. Cela a pu conforter l’image fausse d’une contrelittérature confite en spiritualité et se complaisant dans une forme d’ésotérisme. Très peu ont réellement perçu la dimension révolutionnaire de la contrelittérature. Ezra Pound est un des grands prédécesseurs de la contrelittérature. C’est à partir de lui que j’ai compris la similarité du processus d’homogénéisation de la littérature avec celui de l’usure. Pound a perçu de façon très subtile le phénomène de l’ « argent fictif ». Il insiste dans ses écrits sur la constitution et le développement de la Banque d’Angleterre, modèle du système bancaire moderne né en pays protestant où l’usure avait été autorisée par Élisabeth Tudor en 1571.

Ezra Pound est un des grands prédécesseurs de la contrelittérature. C’est à partir de lui que j’ai compris la similarité du processus d’homogénéisation de la littérature avec celui de l’usure. Pound a perçu de façon très subtile le phénomène de l’ « argent fictif ». Il insiste dans ses écrits sur la constitution et le développement de la Banque d’Angleterre, modèle du système bancaire moderne né en pays protestant où l’usure avait été autorisée par Élisabeth Tudor en 1571. Cependant, Pound n’a pas su reconnaître la surrection du catharisme des troubadours dans l’anarchisme espagnol, ce que Gerald Brenan a très bien vu dans son Labyrinthe espagnol [5]. J’ai soutenu dans Opera Palas cette vision millénariste de la révolution sociale espagnole.

Cependant, Pound n’a pas su reconnaître la surrection du catharisme des troubadours dans l’anarchisme espagnol, ce que Gerald Brenan a très bien vu dans son Labyrinthe espagnol [5]. J’ai soutenu dans Opera Palas cette vision millénariste de la révolution sociale espagnole.  Cette tradition dialogique entre l’incréé et le créé m’évoque le mot principe « Je-Tu » de Martin Buber. L’existence humaine se joue, selon Buber, entre deux mots principes qui sont deux relations antagonistes : « Je-Tu » et « Je-Cela ». Le mot-principe Je-Tu ne peut être prononcé que par l’être entier mais, au contraire, le mot-principe Je-Cela ne peut jamais l’être : « Dire Tu, c’est n’avoir aucune chose pour objet. Car où il y a une chose, il y a autre chose ; chaque Cela confine à d’autres Cela. Cela n’existe que parce qu’il est limité par d’autres Cela. Mais là où l’on dit Tu, il n’y a aucune chose. Tu ne confine à rien. Celui qui dit Tu n’a aucune chose, il n’a rien. Mais il est dans la relation. » [7]

Cette tradition dialogique entre l’incréé et le créé m’évoque le mot principe « Je-Tu » de Martin Buber. L’existence humaine se joue, selon Buber, entre deux mots principes qui sont deux relations antagonistes : « Je-Tu » et « Je-Cela ». Le mot-principe Je-Tu ne peut être prononcé que par l’être entier mais, au contraire, le mot-principe Je-Cela ne peut jamais l’être : « Dire Tu, c’est n’avoir aucune chose pour objet. Car où il y a une chose, il y a autre chose ; chaque Cela confine à d’autres Cela. Cela n’existe que parce qu’il est limité par d’autres Cela. Mais là où l’on dit Tu, il n’y a aucune chose. Tu ne confine à rien. Celui qui dit Tu n’a aucune chose, il n’a rien. Mais il est dans la relation. » [7]  La découverte de l’oeuvre de René Guénon a été décisive dans mon cheminement. Mes parents étaient des anarchistes espagnols et j’ai lu Proudhon, Bakounine et Kropotkine bien avant de lire Guénon. C’est la lecture de René Guénon qui m’a permis de me libérer de la pesanteur de l’idéologie anarchiste.

La découverte de l’oeuvre de René Guénon a été décisive dans mon cheminement. Mes parents étaient des anarchistes espagnols et j’ai lu Proudhon, Bakounine et Kropotkine bien avant de lire Guénon. C’est la lecture de René Guénon qui m’a permis de me libérer de la pesanteur de l’idéologie anarchiste.

Mon intérêt pour la notion de talvera a été suscité par la lecture du sociologue libertaire Yvon Bourdet [10]. La talvera est l’espace du renversement perpétuel du sens, de sa reprise infinie, de son éternel retournement. Elle est la marge nécessaire à la recouvrance du sens perdu, à l’orientation donnée par le centre. Loin de nier le centre, la talvera le rend vivant. La conscience de la vie devenue de plus en plus périphérique, notre aliénation serait irréversible s’il n’y avait un lieu pour concevoir la rencontre, un corps matriciel où l’être, exilé aux confins de son état d’existence, puisse de nouveau se trouver relié à son principe. Sur la talvera se trouve l’éternel féminin de notre liberté, cette dimension mariale que Jean Parvulesco vénérait tant. C’est là que nous nous sommes rencontrés.

Mon intérêt pour la notion de talvera a été suscité par la lecture du sociologue libertaire Yvon Bourdet [10]. La talvera est l’espace du renversement perpétuel du sens, de sa reprise infinie, de son éternel retournement. Elle est la marge nécessaire à la recouvrance du sens perdu, à l’orientation donnée par le centre. Loin de nier le centre, la talvera le rend vivant. La conscience de la vie devenue de plus en plus périphérique, notre aliénation serait irréversible s’il n’y avait un lieu pour concevoir la rencontre, un corps matriciel où l’être, exilé aux confins de son état d’existence, puisse de nouveau se trouver relié à son principe. Sur la talvera se trouve l’éternel féminin de notre liberté, cette dimension mariale que Jean Parvulesco vénérait tant. C’est là que nous nous sommes rencontrés. On ne lit pas Jean Parvulesco sans crainte ni tremblement : la voie chrétienne qui s’y découvre est celle de la main gauche, un tantrisme marial aux limites de la transgression dogmatique. Son style crée dans notre langue française une langue étrangère au phrasé boréal. Mon ami, le romancier Jean-Marc Tisserant, qui l’admirait, me disait que Parvulesco était l’ombre portée de la contrelittérature en son midi : « Vous ne parlez pas de la même chose ni du même lieu », me confia-t-il lors de la dernière conversation que j'eus avec lui. Il est vrai que Parvulesco, à partir de notre séparation, a choisi d’orthographier « contre-littérature », en mot composé – sauf dans le petit ouvrage, Cinq chemins secrets dans la nuit, paru en 2007 aux éditions DVX, qu'il m'a dédié ainsi : « Pour Alain Santacreu et sa contrelittérature ».

On ne lit pas Jean Parvulesco sans crainte ni tremblement : la voie chrétienne qui s’y découvre est celle de la main gauche, un tantrisme marial aux limites de la transgression dogmatique. Son style crée dans notre langue française une langue étrangère au phrasé boréal. Mon ami, le romancier Jean-Marc Tisserant, qui l’admirait, me disait que Parvulesco était l’ombre portée de la contrelittérature en son midi : « Vous ne parlez pas de la même chose ni du même lieu », me confia-t-il lors de la dernière conversation que j'eus avec lui. Il est vrai que Parvulesco, à partir de notre séparation, a choisi d’orthographier « contre-littérature », en mot composé – sauf dans le petit ouvrage, Cinq chemins secrets dans la nuit, paru en 2007 aux éditions DVX, qu'il m'a dédié ainsi : « Pour Alain Santacreu et sa contrelittérature ».  Je ne partage pas ce point de vue. Il n’y a pas eu de victoire de la Première théorie sur la Deuxième mais une fusion des deux dans un capitalisme d’État mondialisé. La postmodernité est anhistorique parce que l’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. C’est cela que j’ai voulu montrer avec Opera Palas. Le prétexte de mon roman est une phrase de George Orwell « Je me rappelle avoir dit un jour à Arthur Koestler : L’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. » Orwell écrit ces mots en 1942, dans un article intitulé « Looking Back on the Spanish War » (Réflexions sur la guerre d’Espagne). Et il poursuit : « En Espagne, pour la première fois, j’ai vu des articles de journaux qui n’avaient aucun rapport avec les faits, ni même l’allure d’un mensonge ordinaire. » Ainsi, parce que la guerre d’Espagne marque la substitution du mensonge médiatique à la vérité objective, l’histoire s’arrête et la période postmoderne s’ouvre alors.

Je ne partage pas ce point de vue. Il n’y a pas eu de victoire de la Première théorie sur la Deuxième mais une fusion des deux dans un capitalisme d’État mondialisé. La postmodernité est anhistorique parce que l’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. C’est cela que j’ai voulu montrer avec Opera Palas. Le prétexte de mon roman est une phrase de George Orwell « Je me rappelle avoir dit un jour à Arthur Koestler : L’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. » Orwell écrit ces mots en 1942, dans un article intitulé « Looking Back on the Spanish War » (Réflexions sur la guerre d’Espagne). Et il poursuit : « En Espagne, pour la première fois, j’ai vu des articles de journaux qui n’avaient aucun rapport avec les faits, ni même l’allure d’un mensonge ordinaire. » Ainsi, parce que la guerre d’Espagne marque la substitution du mensonge médiatique à la vérité objective, l’histoire s’arrête et la période postmoderne s’ouvre alors.

On se rappellera la légende du « Grand Inquisiteur » que Dostoïevski a enchâssée dans Les Frères Karamazov : le Christ réapparaît dans une rue de Séville, à la fin du XVe siècle et, le reconnaissant, le Grand Inquisiteur le fait arrêter. La nuit, dans sa geôle, il vient reprocher au Christ la « folie » du christianisme : la liberté pour l’homme de se déifier en se tournant vers Dieu.

On se rappellera la légende du « Grand Inquisiteur » que Dostoïevski a enchâssée dans Les Frères Karamazov : le Christ réapparaît dans une rue de Séville, à la fin du XVe siècle et, le reconnaissant, le Grand Inquisiteur le fait arrêter. La nuit, dans sa geôle, il vient reprocher au Christ la « folie » du christianisme : la liberté pour l’homme de se déifier en se tournant vers Dieu.

Passer des écrits d’Ernst Jünger sur la Première Guerre mondiale à la lecture de son journal parisien, tenu entre 1940 et 1944, peut surprendre. Que reste-t-il alors de l’officier héroïque de 1918 ? Que reste-t-il de celui qui célébrait avec une dimension mystique sa plongée dans la fureur de la guerre des tranchées ? Que reste-t-il encore de cette expérience combattante qui fit de lui un des officiers les plus décorés de l’armée allemande ? Au cours de ces 20 années, l’homme a incontestablement changé. De son Journal parisien, ce n’est plus l’ivresse du combat qui saisit mais, tout au contraire, l’atonie confortable de la douceur de vie parisienne. S’y exprime la sensibilité d’un homme qui ne semble avoir conservé du soldat que l’uniforme. La guerre y semble lointaine, étonnamment étrangère, alors que le monde s’embrase. L’homme enivré par le combat, le brave des troupes de choc a désormais disparu. L’écrivain semble traverser ce terrible conflit éloigné de toute ambition belliqueuse, porté par cet esprit contemplatif qu’il gardera jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Celui du poète mais aussi de l’entomologiste, l’homme des « chasses subtiles » comme il appelle lui-même ses recherches d’insectes rares. Et c’est encore, non pas en soldat, mais en naturaliste qu’il semble percevoir, dans le ciel de la capitale occupée, les immersions subites et meurtrières de la guerre. Ainsi, quand il observe, une flûte de champagne à la main, les escadrilles de bombardiers britanniques, la description qu’il en fait prend davantage la forme de celle d’un vol de coléoptères que de l’intrusion soudaine d’engins de morts, prêts à lâcher leurs bombes sur la ville.

Passer des écrits d’Ernst Jünger sur la Première Guerre mondiale à la lecture de son journal parisien, tenu entre 1940 et 1944, peut surprendre. Que reste-t-il alors de l’officier héroïque de 1918 ? Que reste-t-il de celui qui célébrait avec une dimension mystique sa plongée dans la fureur de la guerre des tranchées ? Que reste-t-il encore de cette expérience combattante qui fit de lui un des officiers les plus décorés de l’armée allemande ? Au cours de ces 20 années, l’homme a incontestablement changé. De son Journal parisien, ce n’est plus l’ivresse du combat qui saisit mais, tout au contraire, l’atonie confortable de la douceur de vie parisienne. S’y exprime la sensibilité d’un homme qui ne semble avoir conservé du soldat que l’uniforme. La guerre y semble lointaine, étonnamment étrangère, alors que le monde s’embrase. L’homme enivré par le combat, le brave des troupes de choc a désormais disparu. L’écrivain semble traverser ce terrible conflit éloigné de toute ambition belliqueuse, porté par cet esprit contemplatif qu’il gardera jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Celui du poète mais aussi de l’entomologiste, l’homme des « chasses subtiles » comme il appelle lui-même ses recherches d’insectes rares. Et c’est encore, non pas en soldat, mais en naturaliste qu’il semble percevoir, dans le ciel de la capitale occupée, les immersions subites et meurtrières de la guerre. Ainsi, quand il observe, une flûte de champagne à la main, les escadrilles de bombardiers britanniques, la description qu’il en fait prend davantage la forme de celle d’un vol de coléoptères que de l’intrusion soudaine d’engins de morts, prêts à lâcher leurs bombes sur la ville.

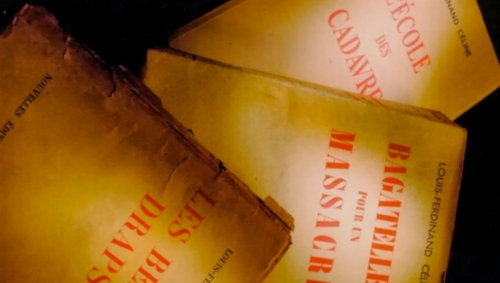

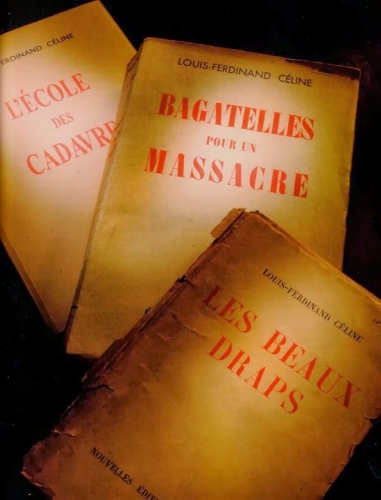

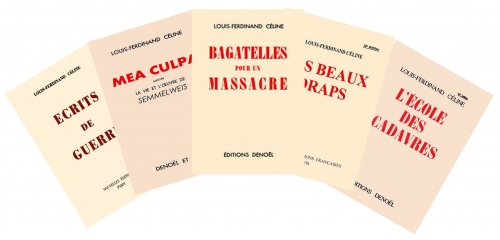

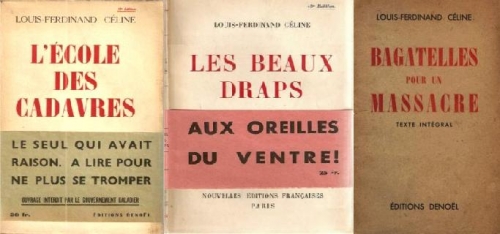

De l’utilité du conditionnel. Dans le Bulletin de janvier, j’aurais dû écrire : « les pamphlets pourraient être réédités par les éditions Gallimard ». Ce numéro fut envoyé aux abonnés le 10 janvier. Le lendemain même, on apprenait qu’Antoine Gallimard jetait l’éponge. C’était à prévoir: les pressions en tous genres furent trop fortes. Dans ce numéro, je rappelle la chronologie des évènements. Ce qui est navrant, c’est qu’en faisant preuve de discrétion, ce naufrage aurait sans doute pu être évité. Il est à relever que l’échéance de mai 2018 circula dans la presse comme date de sortie du volume. Sans doute parce qu’il s’agissait initialement de reprendre tel quel l’appareil critique de l’édition “canadienne” et d’y adjoindre seulement une préface de Pierre Assouline. Certes Sollers commit une indiscrétion en annonçant durant l’été cette réédition. Mais cette confidence n’eut aucun écho car diffusée sur un site internet confidentiel. Lorsque l’information fut reprise sur celui d’un mensuel, il en alla tout autrement. La nouvelle se répandit comme une traînée de poudre et les groupes de pression se mirent en branle avec le succès que l’on sait.

De l’utilité du conditionnel. Dans le Bulletin de janvier, j’aurais dû écrire : « les pamphlets pourraient être réédités par les éditions Gallimard ». Ce numéro fut envoyé aux abonnés le 10 janvier. Le lendemain même, on apprenait qu’Antoine Gallimard jetait l’éponge. C’était à prévoir: les pressions en tous genres furent trop fortes. Dans ce numéro, je rappelle la chronologie des évènements. Ce qui est navrant, c’est qu’en faisant preuve de discrétion, ce naufrage aurait sans doute pu être évité. Il est à relever que l’échéance de mai 2018 circula dans la presse comme date de sortie du volume. Sans doute parce qu’il s’agissait initialement de reprendre tel quel l’appareil critique de l’édition “canadienne” et d’y adjoindre seulement une préface de Pierre Assouline. Certes Sollers commit une indiscrétion en annonçant durant l’été cette réédition. Mais cette confidence n’eut aucun écho car diffusée sur un site internet confidentiel. Lorsque l’information fut reprise sur celui d’un mensuel, il en alla tout autrement. La nouvelle se répandit comme une traînée de poudre et les groupes de pression se mirent en branle avec le succès que l’on sait.

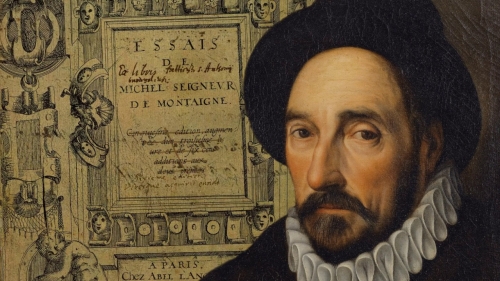

« Tout le monde redoute d’être contrôlé et épié ; les grands le sont jusque dans leurs comportements et leurs pensées, le peuple estimant avoir le droit d’en juger et intérêt à le faire. »

« Tout le monde redoute d’être contrôlé et épié ; les grands le sont jusque dans leurs comportements et leurs pensées, le peuple estimant avoir le droit d’en juger et intérêt à le faire. »

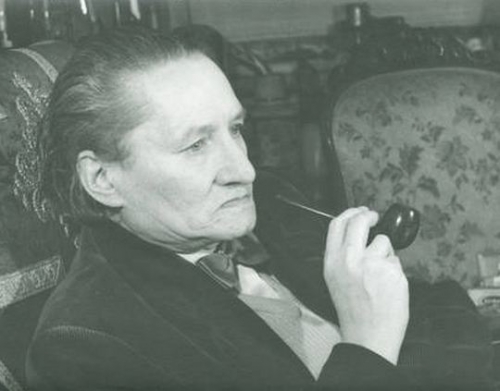

À son père archiviste, il doit sa « passion pour l’ancien ». Son nom de plume date de 1918 et s’inspire de celui d’un petit village des environs de Louvain, région natale de sa mère, qui berce son enfance par la narration de vieilles légendes flamandes.

À son père archiviste, il doit sa « passion pour l’ancien ». Son nom de plume date de 1918 et s’inspire de celui d’un petit village des environs de Louvain, région natale de sa mère, qui berce son enfance par la narration de vieilles légendes flamandes.  La chronique de 1937 consacrée à Bruxelles renferme un superbe éloge du Flâneur, qui « est après tout le dernier avatar de l’homme libre dans une société où personne ne l’est plus guère ». « Ces flâneurs, dont je suis, ne les appelez pas des badauds. Ils méritent mieux, ces attendris, ces lunatiques. La flânerie est une badauderie dirigée, consciente. Et nombre de nos flâneurs ont droit au respect dû aux historiens et archéologues, car ils en savent long sur le passé de leur domaine et vous en révéleront à l’occasion les aspects sensationnels – voire les mystères. »

La chronique de 1937 consacrée à Bruxelles renferme un superbe éloge du Flâneur, qui « est après tout le dernier avatar de l’homme libre dans une société où personne ne l’est plus guère ». « Ces flâneurs, dont je suis, ne les appelez pas des badauds. Ils méritent mieux, ces attendris, ces lunatiques. La flânerie est une badauderie dirigée, consciente. Et nombre de nos flâneurs ont droit au respect dû aux historiens et archéologues, car ils en savent long sur le passé de leur domaine et vous en révéleront à l’occasion les aspects sensationnels – voire les mystères. » Revenons donc à Bruxelles et savourons l’évocation ghelderodienne de la « ville basse », qui « naquit péniblement dans les prés inondés enserrant l’île Saint-Géry » et de la « ville haute [qui] se développe sur le flanc de la vallée couronnée de forêts». Ghelderode est natif de la « ville haute » qui englobe « le pays d’Ixelles, si boisé, riche d’étangs et de terre conventuelles ». L’auteur pense évidemment à l’abbaye de la Cambre, qui abrita la retraite de Sabine d’Egmont, veuve de l’un des deux comtes (Egmont et Harnes) qui conduisirent une révolte anti-espagnole et furent décapités en 1568. Face à « l’homme contemporain de couleur neutre et de cervelle négative battant maussadement l’asphalte de l’Actuel », Ghelderode dresse le modèle du promeneur nostalgique inlassablement motivé par la redécouverte du Passé.

Revenons donc à Bruxelles et savourons l’évocation ghelderodienne de la « ville basse », qui « naquit péniblement dans les prés inondés enserrant l’île Saint-Géry » et de la « ville haute [qui] se développe sur le flanc de la vallée couronnée de forêts». Ghelderode est natif de la « ville haute » qui englobe « le pays d’Ixelles, si boisé, riche d’étangs et de terre conventuelles ». L’auteur pense évidemment à l’abbaye de la Cambre, qui abrita la retraite de Sabine d’Egmont, veuve de l’un des deux comtes (Egmont et Harnes) qui conduisirent une révolte anti-espagnole et furent décapités en 1568. Face à « l’homme contemporain de couleur neutre et de cervelle négative battant maussadement l’asphalte de l’Actuel », Ghelderode dresse le modèle du promeneur nostalgique inlassablement motivé par la redécouverte du Passé.

« Il y a vingt ans que Louis Pauwels est mort. Ce nom ne dit peut-être rien aux jeunes gens d’aujourd’hui ; il disait beaucoup à ceux des années quatre-vingt – ils manifestaient contre « la loi Devaquet », les anciens de 68 les brossaient dans le sens du duvet et Pauwels, lui, « n’ayant pas de minus à courtiser », leur dit virilement qui ils étaient : « les enfants du rock débile, les écoliers de la vulgarité pédagogique, les béats de Coluche et Renaud nourris de soupe infra-idéologique cuite au show-biz, ahuris par les saturnales de “touche pas à mon pote”, et, somme toute, les produits de la culture Lang ». La suite de ce « Monôme des zombies », publié le 6 décembre 1986 dans Le Figaro Magazine, n’était pas moins fouetteur : « Ils ont reçu une imprégnation morale qui leur fait prendre le bas pour le haut. Rien ne leur paraît meilleur que n’être rien, mais tous ensemble, pour n’aller nulle part. […] C’est une jeunesse atteinte d’un sida mental. »

« Il y a vingt ans que Louis Pauwels est mort. Ce nom ne dit peut-être rien aux jeunes gens d’aujourd’hui ; il disait beaucoup à ceux des années quatre-vingt – ils manifestaient contre « la loi Devaquet », les anciens de 68 les brossaient dans le sens du duvet et Pauwels, lui, « n’ayant pas de minus à courtiser », leur dit virilement qui ils étaient : « les enfants du rock débile, les écoliers de la vulgarité pédagogique, les béats de Coluche et Renaud nourris de soupe infra-idéologique cuite au show-biz, ahuris par les saturnales de “touche pas à mon pote”, et, somme toute, les produits de la culture Lang ». La suite de ce « Monôme des zombies », publié le 6 décembre 1986 dans Le Figaro Magazine, n’était pas moins fouetteur : « Ils ont reçu une imprégnation morale qui leur fait prendre le bas pour le haut. Rien ne leur paraît meilleur que n’être rien, mais tous ensemble, pour n’aller nulle part. […] C’est une jeunesse atteinte d’un sida mental. »

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. »

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. » La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) :

La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) : Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt :

Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt : Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé :

Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé : Quant au futur, no comment :

Quant au futur, no comment : Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

En otro momento de la entrevista, Tom Wolfe explica cómo, en su opinión, parte del voto a Donald Trump se comprende por la desolación de quienes se sienten en una status social inferior o de quienes creen que han descendido de status. “En ‘Radical chic’ describí el nacimiento de lo que hoy yo denominaría como ‘izquierda caviar’ o ‘progresismo de limusina’. Se trata de una izquierda que se ha liberado de cualquier responsabilidad con respecto a la clase obrera norteamericana. Es una izquierda que adora el arte contemporáneo, que se identifica con las causas exóticas y el sufrimiento de las minorías… pero que no quiere saber nada de las clases menos sofisticadas y adineradas de Ohio" (...)

En otro momento de la entrevista, Tom Wolfe explica cómo, en su opinión, parte del voto a Donald Trump se comprende por la desolación de quienes se sienten en una status social inferior o de quienes creen que han descendido de status. “En ‘Radical chic’ describí el nacimiento de lo que hoy yo denominaría como ‘izquierda caviar’ o ‘progresismo de limusina’. Se trata de una izquierda que se ha liberado de cualquier responsabilidad con respecto a la clase obrera norteamericana. Es una izquierda que adora el arte contemporáneo, que se identifica con las causas exóticas y el sufrimiento de las minorías… pero que no quiere saber nada de las clases menos sofisticadas y adineradas de Ohio" (...)

One of his earliest influences was Thomas Carlyle, whose concept of the “hero as poet” as described in Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History made a particular impression on him; from a young age, Pessoa saw his vocation as a poet as an heroic, almost messianic calling.

One of his earliest influences was Thomas Carlyle, whose concept of the “hero as poet” as described in Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History made a particular impression on him; from a young age, Pessoa saw his vocation as a poet as an heroic, almost messianic calling.

Pessoa was also fascinated with the occult and wrote extensively on the subject, largely under his own name. In 1915, he began translating theosophist texts and later claimed to have become a medium with the ability to produce automatic writing. He also claimed to have “sudden flashes of ‘etheric vision'” that enabled him to perceive certain symbols and “auras.”

Pessoa was also fascinated with the occult and wrote extensively on the subject, largely under his own name. In 1915, he began translating theosophist texts and later claimed to have become a medium with the ability to produce automatic writing. He also claimed to have “sudden flashes of ‘etheric vision'” that enabled him to perceive certain symbols and “auras.” The theme of decay and the need for national regeneration runs throughout his political writings, particularly his unfinished “History of a Dictatorship,” a survey of modern Portuguese history in which he attempts to outline the causes for Portugal’s decline.

The theme of decay and the need for national regeneration runs throughout his political writings, particularly his unfinished “History of a Dictatorship,” a survey of modern Portuguese history in which he attempts to outline the causes for Portugal’s decline.

Dans Le Rivage des Syrtes, Julien Gracq prend le contre-pied d’une conception exclusivement négative de la barbarie en la présentant comme un renouveau nécessaire à la revivification d’un vieil État somnolent.

Dans Le Rivage des Syrtes, Julien Gracq prend le contre-pied d’une conception exclusivement négative de la barbarie en la présentant comme un renouveau nécessaire à la revivification d’un vieil État somnolent.  Orsenna est l’image même de l’État stable, depuis si longtemps habitué qu’il en a perdu toute vigueur. « Le rassurant de l’équilibre, c’est que rien ne bouge. Le vrai de l’équilibre, c’est qu’il suffit d’un souffle pour faire tout bouger », ainsi que le fait dire Gracq à Marino, le commandant de l’Amirauté, très attaché au maintien de cet équilibre, satisfait de l’existence sans surprise qu’il entraîne et inquiet du moindre changement. Mais à la tête d’Orsenna, un nouveau maître a l’ambition de secouer les choses : « Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans les hasards. Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans le jeu. » Devant un Aldo effaré, Danielo, l’homme fort de la Seigneurie d’Orsenna, expose sa volonté de sauver Orsenna contre elle-même, contre son « assoupissement sans âge », quitte à l’engager sur un chemin de mort et de destruction. « Quand un État a connu de trop de siècles, dit Danielo, la peau épaissie devient un mur, une grande muraille : alors les temps sont venus, alors il est temps que les trompettes sonnent, que les murs s’écroulent, que les siècles se consomment et que les cavaliers entrent par la brèche, les beaux cavaliers qui sentent l’herbe sauvage et la nuit fraîche, avec leurs yeux d’ailleurs et leurs manteaux soulevés par le vent.

Orsenna est l’image même de l’État stable, depuis si longtemps habitué qu’il en a perdu toute vigueur. « Le rassurant de l’équilibre, c’est que rien ne bouge. Le vrai de l’équilibre, c’est qu’il suffit d’un souffle pour faire tout bouger », ainsi que le fait dire Gracq à Marino, le commandant de l’Amirauté, très attaché au maintien de cet équilibre, satisfait de l’existence sans surprise qu’il entraîne et inquiet du moindre changement. Mais à la tête d’Orsenna, un nouveau maître a l’ambition de secouer les choses : « Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans les hasards. Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans le jeu. » Devant un Aldo effaré, Danielo, l’homme fort de la Seigneurie d’Orsenna, expose sa volonté de sauver Orsenna contre elle-même, contre son « assoupissement sans âge », quitte à l’engager sur un chemin de mort et de destruction. « Quand un État a connu de trop de siècles, dit Danielo, la peau épaissie devient un mur, une grande muraille : alors les temps sont venus, alors il est temps que les trompettes sonnent, que les murs s’écroulent, que les siècles se consomment et que les cavaliers entrent par la brèche, les beaux cavaliers qui sentent l’herbe sauvage et la nuit fraîche, avec leurs yeux d’ailleurs et leurs manteaux soulevés par le vent.

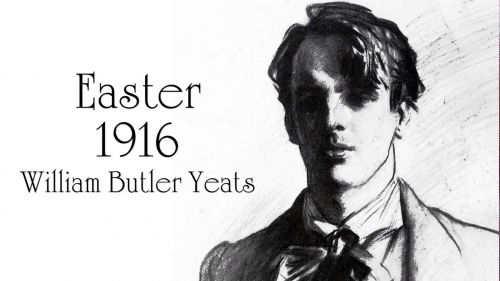

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man.

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man. Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

Celle-ci naît à Vichy en 1902 et y meurt en 1943, ce qui pourrait faire penser à une existence tranquille. C’est tout au contraire un parcours semé d’aventures qui caractérise cette femme dont la première passion est le sculpture. Elle est l’élève et le modèle d’Antoine Bourdelle. Elle obtient une première consécration artistique en 1931 à la faveur d’une exposition de ses œuvres au musée du Luxembourg.

Celle-ci naît à Vichy en 1902 et y meurt en 1943, ce qui pourrait faire penser à une existence tranquille. C’est tout au contraire un parcours semé d’aventures qui caractérise cette femme dont la première passion est le sculpture. Elle est l’élève et le modèle d’Antoine Bourdelle. Elle obtient une première consécration artistique en 1931 à la faveur d’une exposition de ses œuvres au musée du Luxembourg. Voici Terne sortant de prison, disculpé et attendu dans un taxi par son épouse qui lui pardonne son aventure extra-conjugale. « Terne avait appris ce matin de bonne heure qu’il était libre et pouvait rentrer chez lui. La levée d’écrou avait eu lieu. Grisonnant, le teint sali par l’insomnie, le colonel paraissait très vieux, marchant lentement, tête basse, le long du corridor froid et sombre. Le gardien lui avait rendu ses effet. C’est-à-dire son col, sa cravate et ses lacets de soulier. Il tenait à la main le sac de toilette en cuir dont les coins s’étaient usés dans les carlingues d’avions. Terne passa la grande voûte d’entrée et se trouva dans la rue la plus lugubre de Paris.