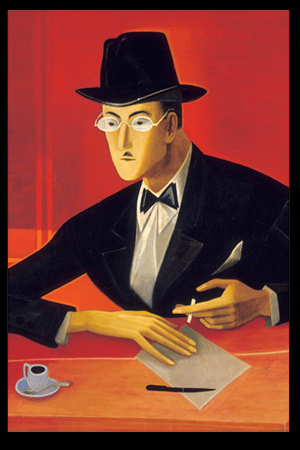

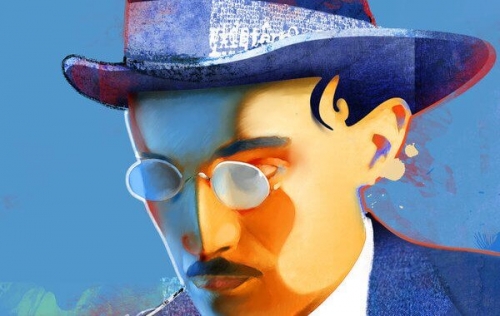

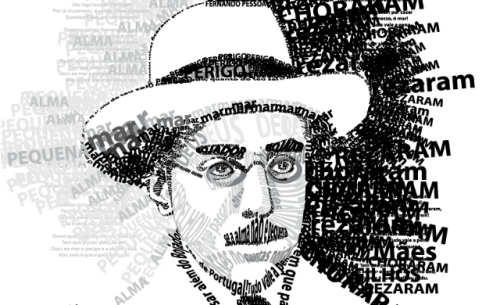

Fernando Pessoa was the greatest Portuguese poet of the modern era and arguably one of the most interesting and protean literary figures of the twentieth century. His vast body of work, some of which remains unpublished, includes hundreds of poems as well as essays on philosophy, religion, literature, and politics. His verse combines avant-garde modernism with pagan mysticism and a vision of national rebirth.

Following the death of his father, his family moved to Durban, South Africa, where the young Pessoa spent most of his childhood. Coincidentally Durban was also the hometown of the South African poet Roy Campbell, who hailed Pessoa as a modern Camões.[1] [2] In Durban Pessoa learned to write fluently in English and received a thorough education in English literature. His first major success came at 15, when he won an award for an English-language essay. He returned to Lisbon two years later and enrolled in the University of Lisbon but dropped out two years later and became an autodidact. During this time he spent his days at the National Library of Portugal and read widely. He spent the rest of his life in Lisbon, making a living as a translator of commercial correspondence.

One of his earliest influences was Thomas Carlyle, whose concept of the “hero as poet” as described in Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History made a particular impression on him; from a young age, Pessoa saw his vocation as a poet as an heroic, almost messianic calling.

One of his earliest influences was Thomas Carlyle, whose concept of the “hero as poet” as described in Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History made a particular impression on him; from a young age, Pessoa saw his vocation as a poet as an heroic, almost messianic calling.

Although Pessoa was active in Portuguese literary circles, he was mostly unknown outside of Portugal during his lifetime. He achieved posthumous literary fame when it was discovered upon his death that he had left behind a trunk full of several thousand pages of unpublished work. The ordeal of editing and cataloguing his works is still in progress.

Pessoa is best known for his use of numerous literary alter egos, which he termed heteronyms. Behind each heteronym was a meticulously crafted persona possessing a complex biography and a distinct temperament, worldview, and writing style. He used more than 70 heteronyms over the course of his life, beginning with adolescent experiments in creating elaborate fictional newspapers complete with news, poems, jokes, and essays authored under various heteronyms. The three main heteronyms he consistently used were Alberto Caeiro, a man of humble origins and lover of nature; Ricardo Reis, a classics scholar and Stoic; and Álvaro de Campos, a naval engineer, world traveler, and Futurist dandy. His heteronyms frequently engaged in dialogues with each other and criticized each other’s works. Pessoa’s work is rife with seeming contradictions, like the man himself: by turns nostalgic and futuristic, cerebral and impassioned, decadent and ascetic, etc.

Among his heteronyms was one “semi-heteronym,” the quasi-autobiographical Bernardo Soares. Pessoa wrote The Book of Disquiet, his greatest prose work, under Soares’s name. (He ascribed the first part to Vicente Guedes and the second to Soares.) The Book of Disquiet is at once a novel, poem, philosophical essay, character study, and “autobiography without events.”[2] [3] Guedes/Soares is an introspective loner with a melancholy temperament, not unlike Pessoa. An bookkeeping assistant by day, he feels imprisoned by the tedium of modern office life and becomes thoroughly disillusioned with the modern world. He finds refuge in cultivating within himself an attitude of aristocratic detachment and complete disinterest in the outside world and escaping into a dreamlike parallel reality. Much of the text reads like fragmentary recollections of dreams and is suffused with rich lyricism and mystical, surreal imagery.

The second phase of the book opens with a statement on religion in the modern world: “I was born at a time when most young people had lost their belief in God for much the same reason that their elders had kept theirs—without knowing why.”[3] [4] Soares then identifies “the worship of Humanity, with its rituals of Liberty and Equality” as a modern substitute for religion and scorns the hollow ideals of liberalism and egalitarianism.[4] [5] Pessoa in his own writings was likewise a fierce critic of the modern cult of “humanity” on the grounds that internationalism had the effect of erasing natural human differences and believed it did little to fill the spiritual vacuum of modernity. In his view this void could only be filled through the creation of art: instead of seeking to express reality, art must itself become reality.

Soares heaps especial scorn upon liberal reformers and their crudely optimistic faith in humanity. Indeed his political apathy and his detachment from the modern world lead him to condemn political revolutionaries of all stripes. Being self-aware, he recognizes that this stance is a symptom of modern decadence but ultimately remains perpetually suspended in a liminal realm between action and inaction (again much like Pessoa himself). This state of unease and ambiguity characterizes The Book of Disquiet both thematically and in a literal sense, as the work was never completed and consists of disjointed fragments, aphorisms, etc. The novel provides a fascinating mirror into the psychology of modern man and the quest to find meaning amid a decaying society.

Pessoa is best known for The Book of Disquiet among the general public, but in his homeland he is primarily known for his 1934 epic poem Message, one of the few works he published during his lifetime and the only one published in Portuguese. He did not write in standard Portuguese but instead in the orthography used before the First World War, which lends the poem an antiquated feel in the original. It consists of 44 short poems grouped into three parts, representing three stages of Portugal’s history. Message became a Portuguese national epic and soon after its publication won second prize in a contest organized by the propaganda branch of António Oliveira de Salazar’s corporatist regime.

The first part, “Brasão” (“Coat of Arms”), has in turn five sections: The Fields, The Castles, The Escutcheons, The Crown, and The Crest, each representing a component of the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Portugal. The coat of arms remains a Portuguese national symbol and is thought to date back to the reign of Afonso I (known as “the Conqueror” and “the Founder”), the first king of Portugal. The shield of the coat of arms can be found on the modern Portuguese flag. The first poem, “The Fields of the Castles,” refers to the bordure of castles in Portugal’s coat of arms that represent Moorish castles conquered by the Kingdom of Portugal during the Reconquista. Pessoa begins by invoking Portugal’s role in the Age of Discovery, describing the European continent as a woman whose face—Portugal—stares westward. The second, “The Fields of the Escutcheons,” refers to the escutcheons in the center of the shield. Each escutcheon bears five white dots, thought to represent the five wounds of Christ, or alternatively the five wounds suffered by Afonso Henriques in the Battle of Ourique (in which he defeated the Moorish Almoravids). Here he defends the notion that glory is borne from misfortune and struggle.

The 17 remaining poems in the first part consist of poems in honor of Portuguese heroes. He begins with Ulysses. According to legend, Lisbon was founded by Ulysses on his journey home from Troy, and Roman authors referred to the city as “Ulyssippo”/”Olissippo.” Pessoa believed that the roots of Portuguese culture lay in ancient Greece and was fascinated with classical antiquity. (Indeed, Lusitanian mythology incorporated the influences of both Celtic and Greco-Roman mythology.) He deems Ulysses one of the founders of the Portuguese nation, despite that he exists only in legend:

Myth is the nothing that is everything.

The very sun that breaks through the skies

Is a bright and speechless myth—

God’s dead body,

Naked and alive.

This hero who cast anchor here,

Because he never was, slowly came to exist.

Without ever being, he sufficed us.

Having never come here,

He came to be our founder.

Thus the legend, little by little,

Seeps into reality

And constantly enriches it.

Life down below, half

Of nothing, perishes.[5] [6]

Next is a poem in honor of Viriathus, a military leader who led the revolts of the Lusitanians (an Indo-European tribe of Celtic origin concentrated in modern-day Portugal) against the Romans during the 2nd century B.C. The remaining titles include Afonso Henriques, who became the first king of Portugal; his parents, the Count and Countess of Portugal; King John I; Prince Henry the Navigator; King Sebastian I; Nuno Álvares Pereira; and others.

King Sebastian I was of particular significance for Pessoa. Toward the end of his life, Sebastian embarked upon a crusade against the Kingdom of Morocco. Ignoring the advice of his top advisors, he marched inland with his entire army. In the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in 1578 (dramatized in Donizetti’s Dom Sébastien), the Portuguese army was routed and it was thought that Sebastian perished, although his body was never found. The absence of an heir to the throne following Sebastian’s death ignited the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580, and Portugal was thrown into turmoil. Philip II of Spain gained control of the Portuguese throne in 1581, uniting Spain and Portugal under the Iberian Union. This marked the beginning of Portugal’s decline. Since Sebastian’s death was never confirmed, many Portuguese hoped that one day he would return to save the nation. A cult grew around this “king in the mountain” myth and Sebastian became Portugal’s equivalent of King Arthur. It was prophesied that one day Sebastian would return and lead Portugal into a new era of imperial glory.

The second part, “Mar Português” (“Portuguese Sea”), is a paean to Portuguese maritime exploration during the Age of Discovery. Here Pessoa eulogizes explorers such as Vasco da Gama, Bartholomeu Dias, and Ferdinand Magellan and describes their journeys at sea. The following short poem describes Vasco da Gama’s ascension following his death, invoking the Titans and the gods of Olympus and comparing da Gama to Jason, leader of the Argonauts:

The Gods of the storm and the giants of Earth

Halt the rage of their war and gape.

In the valley leading up to the skies

A silence falls; then there’s a stirring

And a specter rising in veils of mist.

Fears flank it while it lingers; its vestige

Rumbles in distant clouds and flashes.

On the earth below, the shepherd freezes

And his flute falls as in rapture he sees,

By the light of a thousand thunderbolts,

The sky’s vault open to the Argonaut’s soul.[6] [7]

The title of the third part, “O Encoberto” (“The Hidden One”), refers to a revelation attributed to St. Isidore of Seville, who envisioned that a Messiah would arrive known as “O Encoberto.” This prophecy was popularized during the sixteenth century by a cobbler by the name of Gonçalo Anes (“O Bandarra”); King Sebastian was thought to be “O Encoberto.” In the first two sections, Pessoa invokes the voice of Sebastian and prophesies that he will return, in spirit if not in body, and bring about the Fifth Empire. (He identifies the first four “empires” as Greece, Rome, Christendom, and Europe.) Followers of Sebastianism looked to Daniel 2 in the Bible, in which Daniel interprets the four metals of the statue in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream to signify four great kingdoms that will be followed by a fifth, as a prophecy of the Fifth Empire. In the third section, Pessoa describes the current state of Portugal and states that the hour has come for the prophecy to be fulfilled.

Imperialism deserves criticism from an ethnonationalist point of view. It negates the idea of self-sovereignty and represents the tyranny of commerce and financial greed. Portugal specifically also played a leading role in the Atlantic Slave Trade, which ultimately had disastrous consequences. Nonetheless it is necessary to distinguish the heroism and courage of European explorers during the Age of Discovery from the mercantile greed that was the driving force of colonialist expansion. “Who wants to pass beyond Bojador,” Pessoa writes in “Mar Português” (the Portuguese explorer Gil Eanes was the first to discover a route around Cape Bojador, known for its cold winds and violent storms), “must also pass beyond pain.” Carl Schmitt was highly critical of “thalassocratic” colonial empires but nonetheless admired “the intrepid performance of seamen in their sailing ships, the high art of navigation, the solid training and strict selection of a particular human type fit for it,” which he contrasted with “modern, hazard-free, and technicized maritime traffic.”[7] [8]

Furthermore Pessoa’s vision of the Fifth Empire does not represent a revanchist imperative to conquer the world and reinstate colonialism and imperialism. Rather he envisioned that Portugal would stand at the forefront of a global literary and artistic renaissance and would regain national dignity through cultural renewal. The Sebastianism of Message represented a symbolic national myth that he believed would unite the Portuguese people.

Message has often been compared to Camões’s Os Lusíadas, an epic poem chronicling Vasco da Gama’s discovery of a sea route to India. Both invoke heroic and nationalistic themes. Both are also reminiscent of ancient epics, particularly Os Lusíadas. The opening lines of Os Lusíadas recalls Virgil’s Aeneid and are followed by an episode in which the Olympian gods and goddesses gather to deliberate over Vasco da Gama’s voyage and split into two parties, one favoring the Portuguese and the other in opposition to them. The gods accompany da Gama throughout his journey and Greco-Roman mythology in general figures prominently throughout the poem.

Pessoa’s greatest inspiration was ancient Greece. He was an avid Hellenist and dreamed of a renaissance of the ancient gods. This point of view is shared among his heteronyms. He articulated his views on religion most thoroughly through Antonio Mora, a disciple of Caeiros, who wrote some treatises on the subject and argued that paganism was the religion most in harmony with nature. His most interesting argument here involves a discussion of how a Christian, pantheist, materialist, and pagan would perceive any given object. Regarding Christians, he remarks: “Whoever values something because it was created by ‘God’ values it not for what it is but for what it recalls. His eyes behold the object, but his thoughts lie elsewhere.”[8] [9] For the materialist, each object is simply “a screen through which he atomistically peers, just as for the pantheist it is a screen or window for perceiving the Whole, and for the creationist a screen through which to see God.”[9] [10] Only the pagan is capable of perceiving reality to the full. Pessoa under his own name laid out a similar view in his writings on what he termed “sensationism.”

Mora also cites the polytheism and plurality inherent in paganism and argues that this lends it greater objectivity: “Reality, when it first appears to us, is multiple. By referring all received sensations to our individual consciousness, we impose a false unity (false to our experience) on the original multiplicity of things.”[10] [11] Pessoa believed that metaphysical subjectivism lay at the root of modern decadence. His use of heteronyms thus represented an extension of his religious views and an attempt to reflect nature in all its plurality.

Mora’s remark on being a pagan in the modern world will resonate with dissidents:

What relationship can an age like this one have with a spiritual heir to the race of constructors, with a soul inspired by paganism’s glorious truths? None, except one of instinctive rejection and automatic scorn. We, the only dissenters from decadence, are thus forced to assume an attitude that, by its nature is likewise decadent. An attitude of indifference is a decadent attitude, and our inability to adapt to the current milieu forces us to just such an attitude. We don’t adapt, because healthy people cannot adapt to a sick milieu, and since we don’t adapt, it is we who are sick. This is the paradox in which those of us who are pagans live.[11] [12]

In 1924 Pessoa founded a short-lived literary journal called Athena in which he published essays, poems, and translations under his three main heteronyms as well as his own name. These included translations from the Greek Anthology, Ricardo Reis’s Horace-inspired classical odes, and selections from Alberto Caeiro’s The Keeper of Sheep. The journal both eulogized pagan antiquity and stood at the vanguard of literary modernism; it represented “a denial of the old querelle des Anciens et des Modernes, and an impressive attempt to find an ancient form of dramatic art in modern times.”[12] [13]

Athena was an attempt to revive the movement surrounding the similarly short-lived journal Orpheu, which dissolved after the publication of two issues in 1915. It was responsible for introducing modernism to Portugal and was named for Orpheus to symbolize its forward-looking orientation. Orpheu represented a wide variety of literary currents ranging from Symbolism to Futurism. The most notable poems in Orpheu were the poems of Pessoa’s Álvaro de Campos. In “Opiario,” written while sailing through the Suez Canal on an eastward voyage, he describes with despair his opium addiction and the tedium of life aboard his ship. Directly following was “Ode Triunfal,” which takes place later in his evolution (although in reality Pessoa wrote it earlier), a Futurist ode to modern technology that extols the “great human tropics of iron and fire and strength.” There was also “Ode Maritima,” in which a man on a deserted quay gazes at a faraway steamer; “a steering wheel begins to turn, slowly” in his imagination, launching a stream-of-consciousness ode to “shipwrecks, far-off voyages, dangerous crossings,” pirate adventures, and so forth.

Pessoa was also fascinated with the occult and wrote extensively on the subject, largely under his own name. In 1915, he began translating theosophist texts and later claimed to have become a medium with the ability to produce automatic writing. He also claimed to have “sudden flashes of ‘etheric vision'” that enabled him to perceive certain symbols and “auras.”[13] [14] He later came to distance himself from Theosophy, however, objecting to what he saw as its egalitarian premise and the theosophical ideal of a universal brotherhood of humanity, which in his view rendered it scarcely different from Christianity and liberal humanism (which he referred to as Christianity’s secular equivalent).

Pessoa was also fascinated with the occult and wrote extensively on the subject, largely under his own name. In 1915, he began translating theosophist texts and later claimed to have become a medium with the ability to produce automatic writing. He also claimed to have “sudden flashes of ‘etheric vision'” that enabled him to perceive certain symbols and “auras.”[13] [14] He later came to distance himself from Theosophy, however, objecting to what he saw as its egalitarian premise and the theosophical ideal of a universal brotherhood of humanity, which in his view rendered it scarcely different from Christianity and liberal humanism (which he referred to as Christianity’s secular equivalent).

Pessoa also maintained a correspondence with Aleister Crowley. An avid astrologer, he first made contact with Crowley in 1930 by pointing out an astrological error in his Confessions. Crowley visited Portugal later that year and Pessoa aided him in faking his death. He also translated Crowley’s “Hymn to Pan” into Portuguese.[14] [15]

The glorification of Sebastianism as national myth in Message had an occult component. Pessoa’s vision of the Fifth Empire was a spiritual one and the arc of Message represents a religious quest, both on an individual and national level. The final part of Message alludes to Arthurian legend throughout (the Holy Grail, Excalibur, Sir Galahad). In “O Desejado” (“The Yearned-for One”), the narrator exhorts Sebastian to lift up Excalibur, his “anointed sword.” In “O Encoberto” (the poem that gives the final part its name), Pessoa also links Sebastianism with Rosicrucianism.

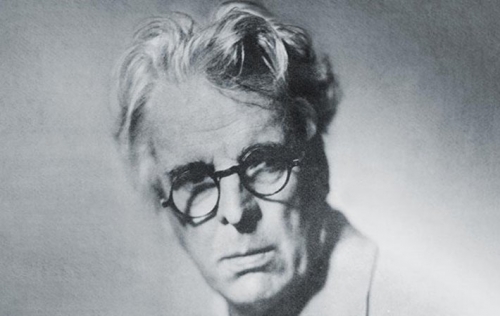

Pessoa is frequently compared to W. B. Yeats: in addition to their shared interest in the occult (Yeats was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn) and their use of alternate personae (Yeats’s “masks” and Pessoa’s heteronyms), both were “mystical nationalists” who wrote poetry of a pagan, heroic character through which they sought to bring about a renaissance in their respective nations. Pessoa admired Yeats’s poetry and was influenced by the Irish Literary Revival. The following lists some parallels between the two regarding their shared “underlying mythopoeic goal” and is worth quoting:

Pessoa’s concept of the ‘Portuguese soul’ is analogous to what Yeats calls ‘the permanent character of the race’ in ‘First Principles.’ Not only that, but he also attributes the same characteristics to it as those which Yeats attributed to the Celts in ‘The Celtic Element in Literature,’ namely an adventurous, tragic and mystical nature. The similarities extend to Pessoa’s characterization of the ‘Portuguese soul’ as originating from ancient dreams, which recalls Yeats’s depiction of his ideal of ‘Unity of Culture’ as ‘a nationwide multiform reverie.’ Yeats believed that by drawing on his country’s legends and folklore, a poet could reveal the Anima Mundi, or rather ‘a Great Memory passing on from generation to generation.’ Pessoa also believed that poets should derive their inspiration from ‘o que nas almas há de superindividual’ [that which is supra-individual in souls].[15] [16]

Also like Yeats, Pessoa was a man of the Right who opposed modern liberalism and egalitarianism. He described the ideal state as an “aristocratic republic” governed by an elite based on merit (rather than birth).[16] [17] Although he had reservations about fascism in his later years, he criticized it nonetheless from a right-wing perspective.

As a young man, Pessoa was a staunch opponent of monarchy and the Catholic Church, which he considered to be corrupt, moribund institutions and to which he attributed Portugal’s decline. (Other factors he associated with Portugal’s decline were “foreign influence, the oligarchy of political bosses, and the decline ofWestern civilization itself.”)[17] [18] He initially supported the First Portuguese Republic and was associated with the Portuguese Renaissance, a movement of intellectuals who sought to lend the republic cultural legitimacy, but turned against the new government when it became clear that it had not improved upon the flaws of the recently deposed monarchy. He supported the military coup d’état on May 28, 1926, which he believed would reinvigorate the nation following the failure of the republic. In a pamphlet written in 1928, he argued that military dictatorship was a useful temporary measure through which national consciousness could be strengthened.[18] [19] He also supported Salazar’s Estado Novo for this reason. However, he later began to grow disillusioned with Salazar and criticized the regime’s ban on Freemasonry and what he perceived as Salazar’s lack of interest in cultural affairs.

The theme of decay and the need for national regeneration runs throughout his political writings, particularly his unfinished “History of a Dictatorship,” a survey of modern Portuguese history in which he attempts to outline the causes for Portugal’s decline.[19] [20] Pessoa viewed the state as akin to an organism that, on account of its inherent plurality, possesses a natural tendency toward disintegration. Like the ancients, he held that unity ought to be the principle aim of politics and that achieving national unity would enable the state to resist decline. He writes in “The Portuguese Regicide and the Political Situation in Portugal”:

The theme of decay and the need for national regeneration runs throughout his political writings, particularly his unfinished “History of a Dictatorship,” a survey of modern Portuguese history in which he attempts to outline the causes for Portugal’s decline.[19] [20] Pessoa viewed the state as akin to an organism that, on account of its inherent plurality, possesses a natural tendency toward disintegration. Like the ancients, he held that unity ought to be the principle aim of politics and that achieving national unity would enable the state to resist decline. He writes in “The Portuguese Regicide and the Political Situation in Portugal”:

Let us apply to the organism called the state the general law of life. Which are the elements (composing the cells) of this organism? Obviously the people, that is, the individuals composing the nation. Which is then, in the state, the force that integrates, which is the force that disintegrates? There is an exact analogy—how could there not be, since both are living “bodies”?—with the individual organism. Thus, in the state, obviously, the disintegrating force is that which makes the people many—their number—and the integrating force is that which makes them one, a people—the unification of sentiments, of character brought about by identity of race, of climate, of history, etc.[20] [21]

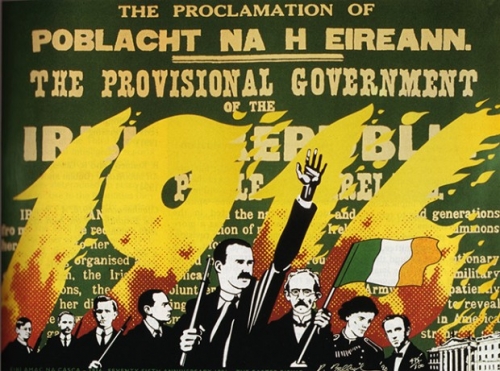

Pessoa also commented on certain political events outside of Portugal, particularly in his English-language poetry. At 16, he wrote a sonnet on the Second Boer War entitled “Joseph Chamberlain,” a scathing indictment of Chamberlain’s role in causing the war and the brutal treatment of the Boers in South Africa. He also drafted a sonnet in which he excoriated Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener, the man responsible for the establishment of concentration camps during the war. He commended the Irish volunteers who had sided with the Boers and also lent support to Irish nationalism.[21] [22]

In his short story The Anarchist Banker, Pessoa takes aim at modern capitalism and classical liberalism. It takes the form of a conversation between a cigar-smoking senior banker and a younger interlocutor. The banker is a left-wing anarchist who sets out to argue that his being a banker does not contradict the ideals of liberty and equality that he espouses. Indeed he argues that financial acquisitiveness is the logical culmination of his ideals, and by extension of modern liberalism. In order to obtain true freedom and equality (the two main pillars of modernity), he argues that man must be freed from all existing social structures. But he is averse to any collective attempts to foment revolution due to the fact that social hierarchies will inevitably arise in any group (the banker is realistic about natural disparities in talent and willpower among humans, in spite of his hope that human inequality will eventually be eliminated). Thus he advocates the pursuit of pure self-interest, arguing that “we should all work for the same end, but separately.”[22] [23] Due to the fact that money/commerce is the prevailing “social fiction” in the modern age, the end goal of social liberation is, to his mind, best achieved by simply making as much money as possible; the erosion of this “social fiction” would then pave the way for complete societal upheaval. It is a compelling argument that sheds light on some of the contradictions behind the underlying axioms of modernity.

The best collections of Pessoa’s work in English translation are The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa (2001), Fernando Pessoa & Co: Selected Poems (1999), and A Little Larger Than the Entire Universe: Selected Poems (2006).

Notes

[1] [24] George Monteiro, “Fernando Pessoa: an Unfinished Manuscript by Roy Campbell,” Portuguese Studies, vol. 10 (1994): 126. Pessoa and Campbell attended the same high school, although not at the same time. Campbell translated some of Pessoa’s poems and had intended to write a book on him.

[2] [25] Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, trans., Margaret Jull Costa (New York: New Directions Books, 2017), 191.

[3] [26] Ibid., 146. Pessoa wrote “opening passage” in the margins of this fragment and Richard Zenith’s translation places it at the beginning of the book.

[4] [27] Ibid., 147.

[5] [28] Zenith’s translation.

[6] [29] Zenith’s translation.

[7] [30] Carl Schmitt, Land and Sea, trans. Simona Draghici (Washington, D.C.: Plutarch Press, 1997), 54.

[8] [31] The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa, trans. Richard Zenith (New York: Grove Atlantic, 2001).

[9] [32] Ibid.

[10] [33] Ibid.

[11] [34] Ibid.

[12] [35] Steffen Dix, Portuguese Modernisms: Multiple Perspectives in Literature and the Visual Arts (New York: Routledge, 2011).

[13] [36] The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa.

[14] [37] For more information on their correspondence see Marco Pasi and Patricio Ferrari, “Fernando Pessoa and Aleister Crowley: New discoveries and a new analysis of the documents in the Gerald Yorke Collection,” Pessoa Plural, vol. 1 (Spring 2012).

[15] [38] Patricia Silva-McNeill, Yeats and Pessoa: Parallel Poetic Styles (New York: Routledge, 2010), 94.

[16] [39] José Barreto, “‘History of a Dictatorship’: An Unfinished Political Essay by the Young Fernando Pessoa,” trans., Mario Pereira. In Patricio Ferrari & Jerónimo Pizarro, eds., Fernando Pessoa as English Reader and Writer (Dartmouth, MA: Tagus Press, 2015): 132.

[17] [40] Barreto, 139.

[18] [41] The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa.

[19] [42] Barreto, 110.

[20] [43] Fernando Pessoa, The Transformation Book, eds., Nuno Ribeiro and Claudia Souza (New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2014), 12-13.

[21] [44] See Carlos Pittella, “Chamberlain, Kitchener, Kropotkine—and the political Pessoa,” Pessoa Plural, vol. 10 (Fall 2016).

[22] [45] The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa.

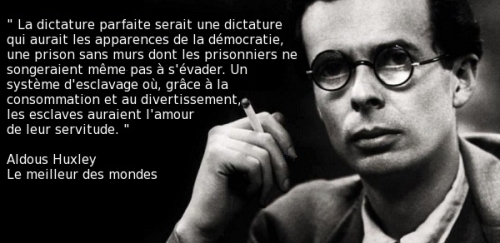

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. »

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. » La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) :

La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) : Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt :

Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt : Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé :

Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé : Quant au futur, no comment :

Quant au futur, no comment : Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

En otro momento de la entrevista, Tom Wolfe explica cómo, en su opinión, parte del voto a Donald Trump se comprende por la desolación de quienes se sienten en una status social inferior o de quienes creen que han descendido de status. “En ‘Radical chic’ describí el nacimiento de lo que hoy yo denominaría como ‘izquierda caviar’ o ‘progresismo de limusina’. Se trata de una izquierda que se ha liberado de cualquier responsabilidad con respecto a la clase obrera norteamericana. Es una izquierda que adora el arte contemporáneo, que se identifica con las causas exóticas y el sufrimiento de las minorías… pero que no quiere saber nada de las clases menos sofisticadas y adineradas de Ohio" (...)

En otro momento de la entrevista, Tom Wolfe explica cómo, en su opinión, parte del voto a Donald Trump se comprende por la desolación de quienes se sienten en una status social inferior o de quienes creen que han descendido de status. “En ‘Radical chic’ describí el nacimiento de lo que hoy yo denominaría como ‘izquierda caviar’ o ‘progresismo de limusina’. Se trata de una izquierda que se ha liberado de cualquier responsabilidad con respecto a la clase obrera norteamericana. Es una izquierda que adora el arte contemporáneo, que se identifica con las causas exóticas y el sufrimiento de las minorías… pero que no quiere saber nada de las clases menos sofisticadas y adineradas de Ohio" (...)

Dans Le Rivage des Syrtes, Julien Gracq prend le contre-pied d’une conception exclusivement négative de la barbarie en la présentant comme un renouveau nécessaire à la revivification d’un vieil État somnolent.

Dans Le Rivage des Syrtes, Julien Gracq prend le contre-pied d’une conception exclusivement négative de la barbarie en la présentant comme un renouveau nécessaire à la revivification d’un vieil État somnolent.  Orsenna est l’image même de l’État stable, depuis si longtemps habitué qu’il en a perdu toute vigueur. « Le rassurant de l’équilibre, c’est que rien ne bouge. Le vrai de l’équilibre, c’est qu’il suffit d’un souffle pour faire tout bouger », ainsi que le fait dire Gracq à Marino, le commandant de l’Amirauté, très attaché au maintien de cet équilibre, satisfait de l’existence sans surprise qu’il entraîne et inquiet du moindre changement. Mais à la tête d’Orsenna, un nouveau maître a l’ambition de secouer les choses : « Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans les hasards. Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans le jeu. » Devant un Aldo effaré, Danielo, l’homme fort de la Seigneurie d’Orsenna, expose sa volonté de sauver Orsenna contre elle-même, contre son « assoupissement sans âge », quitte à l’engager sur un chemin de mort et de destruction. « Quand un État a connu de trop de siècles, dit Danielo, la peau épaissie devient un mur, une grande muraille : alors les temps sont venus, alors il est temps que les trompettes sonnent, que les murs s’écroulent, que les siècles se consomment et que les cavaliers entrent par la brèche, les beaux cavaliers qui sentent l’herbe sauvage et la nuit fraîche, avec leurs yeux d’ailleurs et leurs manteaux soulevés par le vent.

Orsenna est l’image même de l’État stable, depuis si longtemps habitué qu’il en a perdu toute vigueur. « Le rassurant de l’équilibre, c’est que rien ne bouge. Le vrai de l’équilibre, c’est qu’il suffit d’un souffle pour faire tout bouger », ainsi que le fait dire Gracq à Marino, le commandant de l’Amirauté, très attaché au maintien de cet équilibre, satisfait de l’existence sans surprise qu’il entraîne et inquiet du moindre changement. Mais à la tête d’Orsenna, un nouveau maître a l’ambition de secouer les choses : « Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans les hasards. Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans le jeu. » Devant un Aldo effaré, Danielo, l’homme fort de la Seigneurie d’Orsenna, expose sa volonté de sauver Orsenna contre elle-même, contre son « assoupissement sans âge », quitte à l’engager sur un chemin de mort et de destruction. « Quand un État a connu de trop de siècles, dit Danielo, la peau épaissie devient un mur, une grande muraille : alors les temps sont venus, alors il est temps que les trompettes sonnent, que les murs s’écroulent, que les siècles se consomment et que les cavaliers entrent par la brèche, les beaux cavaliers qui sentent l’herbe sauvage et la nuit fraîche, avec leurs yeux d’ailleurs et leurs manteaux soulevés par le vent.

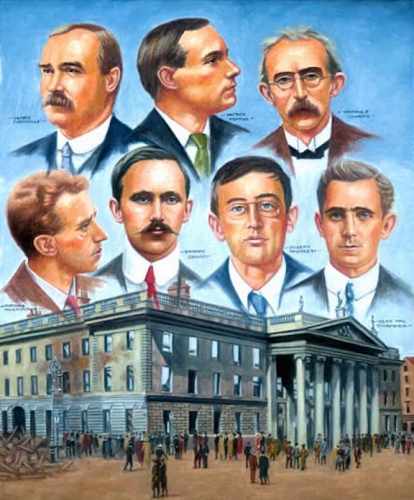

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man.

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man. Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

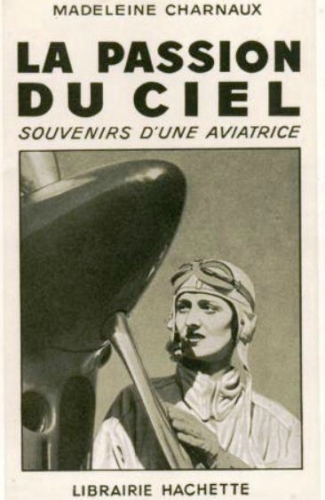

Celle-ci naît à Vichy en 1902 et y meurt en 1943, ce qui pourrait faire penser à une existence tranquille. C’est tout au contraire un parcours semé d’aventures qui caractérise cette femme dont la première passion est le sculpture. Elle est l’élève et le modèle d’Antoine Bourdelle. Elle obtient une première consécration artistique en 1931 à la faveur d’une exposition de ses œuvres au musée du Luxembourg.

Celle-ci naît à Vichy en 1902 et y meurt en 1943, ce qui pourrait faire penser à une existence tranquille. C’est tout au contraire un parcours semé d’aventures qui caractérise cette femme dont la première passion est le sculpture. Elle est l’élève et le modèle d’Antoine Bourdelle. Elle obtient une première consécration artistique en 1931 à la faveur d’une exposition de ses œuvres au musée du Luxembourg. Voici Terne sortant de prison, disculpé et attendu dans un taxi par son épouse qui lui pardonne son aventure extra-conjugale. « Terne avait appris ce matin de bonne heure qu’il était libre et pouvait rentrer chez lui. La levée d’écrou avait eu lieu. Grisonnant, le teint sali par l’insomnie, le colonel paraissait très vieux, marchant lentement, tête basse, le long du corridor froid et sombre. Le gardien lui avait rendu ses effet. C’est-à-dire son col, sa cravate et ses lacets de soulier. Il tenait à la main le sac de toilette en cuir dont les coins s’étaient usés dans les carlingues d’avions. Terne passa la grande voûte d’entrée et se trouva dans la rue la plus lugubre de Paris.

Voici Terne sortant de prison, disculpé et attendu dans un taxi par son épouse qui lui pardonne son aventure extra-conjugale. « Terne avait appris ce matin de bonne heure qu’il était libre et pouvait rentrer chez lui. La levée d’écrou avait eu lieu. Grisonnant, le teint sali par l’insomnie, le colonel paraissait très vieux, marchant lentement, tête basse, le long du corridor froid et sombre. Le gardien lui avait rendu ses effet. C’est-à-dire son col, sa cravate et ses lacets de soulier. Il tenait à la main le sac de toilette en cuir dont les coins s’étaient usés dans les carlingues d’avions. Terne passa la grande voûte d’entrée et se trouva dans la rue la plus lugubre de Paris.

Much of this confusion stems from the fact that National Bolshevism did not have a guiding text or any kind of magnum opus for the proliferation of a workers’ state ruled by nationalist sentiment. The closest to such a founding document is Ernst Junger’s

Much of this confusion stems from the fact that National Bolshevism did not have a guiding text or any kind of magnum opus for the proliferation of a workers’ state ruled by nationalist sentiment. The closest to such a founding document is Ernst Junger’s  Niekisch would become the greatest propagandist for National Bolshevism during the Weimar era. His short-lived journal Widerstand would publish Junger and other German writers who wanted to mix the austere radicalism of the Bolsheviks with that frontline soldier’s dedication to nation.

Niekisch would become the greatest propagandist for National Bolshevism during the Weimar era. His short-lived journal Widerstand would publish Junger and other German writers who wanted to mix the austere radicalism of the Bolsheviks with that frontline soldier’s dedication to nation.

« Ce monde est dérisoire, mais il a mis fin à la possibilité de dire à quel point il est dérisoire ; du moins s’y efforce-t-il, et de bons apôtres se demandent aujourd’hui si l’humour n’a pas tout simplement fait son temps, si on a encore besoin de lui, etc. Ce qui n’est d’ailleurs pas si bête, car le rire, le rire en tant qu’art, n’a en Europe que quelques siècles d’existence derrière lui (il commence avec Rabelais), et il est fort possible que le conformisme tout à fait neuf mais d’une puissance inégalée qui lui mène la guerre (tout en semblant le favoriser sous les diverses formes bidons du fun, du déjanté, etc.) ait en fin de compte raison de lui. En attendant, mon objet étant les civilisations occidentales, et particulièrement la française, qui me semble exemplaire par son marasme extrême, par les contradictions qui l’écrasent, et en même temps par cette bonne volonté qu’elle manifeste, cette bonne volonté typiquement et globalement provinciale de s’enfoncer encore plus vite et plus irrémédiablement que les autres dans le suicide moderne, je crois que le rire peut lui apporter un éclairage fracassant. »

« Ce monde est dérisoire, mais il a mis fin à la possibilité de dire à quel point il est dérisoire ; du moins s’y efforce-t-il, et de bons apôtres se demandent aujourd’hui si l’humour n’a pas tout simplement fait son temps, si on a encore besoin de lui, etc. Ce qui n’est d’ailleurs pas si bête, car le rire, le rire en tant qu’art, n’a en Europe que quelques siècles d’existence derrière lui (il commence avec Rabelais), et il est fort possible que le conformisme tout à fait neuf mais d’une puissance inégalée qui lui mène la guerre (tout en semblant le favoriser sous les diverses formes bidons du fun, du déjanté, etc.) ait en fin de compte raison de lui. En attendant, mon objet étant les civilisations occidentales, et particulièrement la française, qui me semble exemplaire par son marasme extrême, par les contradictions qui l’écrasent, et en même temps par cette bonne volonté qu’elle manifeste, cette bonne volonté typiquement et globalement provinciale de s’enfoncer encore plus vite et plus irrémédiablement que les autres dans le suicide moderne, je crois que le rire peut lui apporter un éclairage fracassant. » « Festivus festivus, qui vient après Homo festivus comme Sapiens sapiens succède à Homo sapiens, est l’individu qui festive qu’il festive : c’est le moderne de la nouvelle génération, dont la métamorphose est presque totalement achevée, qui a presque tout oublié du passé (de toute façon criminel à ses yeux) de l’humanité, qui est déjà pour ainsi dire génétiquement modifié sans même besoin de faire appel à des bricolages techniques comme on nous en promet, qui est tellement poli, épuré jusqu’à l’os, qu’il en est translucide, déjà clone de lui-même sans avoir besoin de clonage, nettoyé sous toutes les coutures, débarrassé de toute extériorité comme de toute transcendance, jumeau de lui-même jusque dans son nom. »

« Festivus festivus, qui vient après Homo festivus comme Sapiens sapiens succède à Homo sapiens, est l’individu qui festive qu’il festive : c’est le moderne de la nouvelle génération, dont la métamorphose est presque totalement achevée, qui a presque tout oublié du passé (de toute façon criminel à ses yeux) de l’humanité, qui est déjà pour ainsi dire génétiquement modifié sans même besoin de faire appel à des bricolages techniques comme on nous en promet, qui est tellement poli, épuré jusqu’à l’os, qu’il en est translucide, déjà clone de lui-même sans avoir besoin de clonage, nettoyé sous toutes les coutures, débarrassé de toute extériorité comme de toute transcendance, jumeau de lui-même jusque dans son nom. » « Dans le nouveau monde, on ne retrouve plus trace du Mal qu’à travers l’interminable procès qui lui est intenté, à la fois en tant que Mal historique (le passé est un chapelet de crimes qu’il convient de ré-instruire sans cesse pour se faire mousser sans risque) et en tant que Mal actuel postiche. »

« Dans le nouveau monde, on ne retrouve plus trace du Mal qu’à travers l’interminable procès qui lui est intenté, à la fois en tant que Mal historique (le passé est un chapelet de crimes qu’il convient de ré-instruire sans cesse pour se faire mousser sans risque) et en tant que Mal actuel postiche. » « …pour en revenir à cette solitude sexuelle d’Homo festivus, qui contient tous les autres traits que vous énumérez, elle ne peut être comprise que comme l’aboutissement de la prétendue libération sexuelle d’il y a trente ans, laquelle n’a servi qu’à faire monter en puissance le pouvoir féminin et à révéler ce que personne au fond n’ignorait (notamment grâce aux romans du passé), à savoir que les femmes ne voulaient pas du sexuel, n’en avaient jamais voulu, mais qu’elles en voulaient dès lors que le sexuel devenait objet d’exhibition, donc de social, donc d’anti-sexuel. »

« …pour en revenir à cette solitude sexuelle d’Homo festivus, qui contient tous les autres traits que vous énumérez, elle ne peut être comprise que comme l’aboutissement de la prétendue libération sexuelle d’il y a trente ans, laquelle n’a servi qu’à faire monter en puissance le pouvoir féminin et à révéler ce que personne au fond n’ignorait (notamment grâce aux romans du passé), à savoir que les femmes ne voulaient pas du sexuel, n’en avaient jamais voulu, mais qu’elles en voulaient dès lors que le sexuel devenait objet d’exhibition, donc de social, donc d’anti-sexuel. »

Polémique pour une autre fois

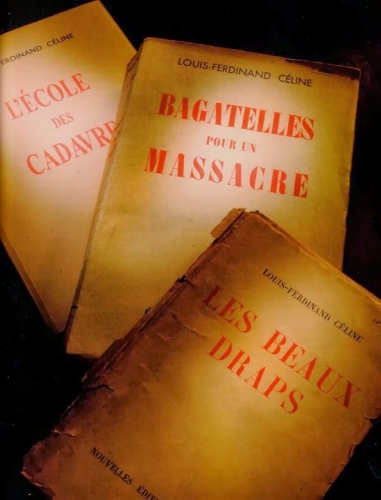

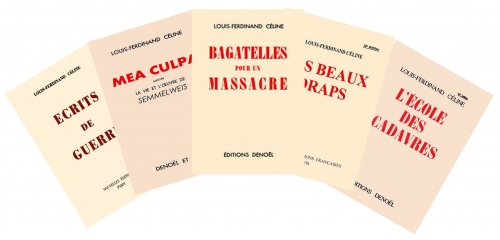

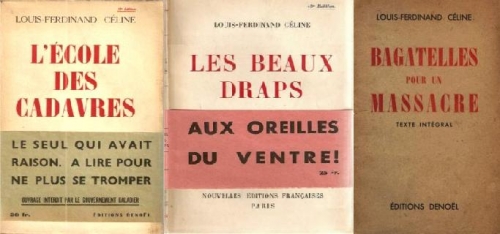

Polémique pour une autre fois Redouter, plus largement, que les pamphlets de Céline ne corrompent la jeunesse, c’est supposer à cette dernière une capacité à lire qu’elle n’a plus. Car Céline n’est pas un écrivain facile, et nullement à la portée de ceux qui, voyous islamistes de banlieue ou petits-bourgeois connectés, ont bénéficié l’enseignement de l’ignorance qui est, selon Michéa, le propre de l’Education nationale. Un état de fait pieusement réfuté, à l’occasion du cinquantenaire de Mai 68, par un magazine officiel qui voit, dans les 50 années qui se sont écoulées, un remarquable progrès de l’enseignement public : ne sommes-nous pas arrivé à 79% de bacheliers, c’est-à-dire un progrès de 20% ? En vérité il faut, en cette matière comme en toutes les autres, inverser le discours : il ne reste plus que 20%, environ, d’élèves à peu près capables de lire et d’écrire correctement le français, et de se représenter l’histoire de France autrement que par le filtre relativiste et mondialiste du néo-historicisme.

Redouter, plus largement, que les pamphlets de Céline ne corrompent la jeunesse, c’est supposer à cette dernière une capacité à lire qu’elle n’a plus. Car Céline n’est pas un écrivain facile, et nullement à la portée de ceux qui, voyous islamistes de banlieue ou petits-bourgeois connectés, ont bénéficié l’enseignement de l’ignorance qui est, selon Michéa, le propre de l’Education nationale. Un état de fait pieusement réfuté, à l’occasion du cinquantenaire de Mai 68, par un magazine officiel qui voit, dans les 50 années qui se sont écoulées, un remarquable progrès de l’enseignement public : ne sommes-nous pas arrivé à 79% de bacheliers, c’est-à-dire un progrès de 20% ? En vérité il faut, en cette matière comme en toutes les autres, inverser le discours : il ne reste plus que 20%, environ, d’élèves à peu près capables de lire et d’écrire correctement le français, et de se représenter l’histoire de France autrement que par le filtre relativiste et mondialiste du néo-historicisme.

Le terme « bushidô », utilisé en ce sens serait apparue pour la première fois dans le koyo gunkan, la chronique militaire de la province du Kai dirigée par le célèbre clan des Takeda (la chronique a été compilée par Kagenori Obata (1572-1663), le fils d’un imminent stratège du clan à partir de 1615. L’historien japonais Yamamoto Hirofumi (Yamamoto Hirofumi, Nihonjin no kokoro : bushidô nyûmon, Chûkei éditions, Tôkyô, 2006), constata au cours de ses recherches l’absence, à l’époque moderne, de textes formulant une éthique des guerriers qui auraient pu être accessibles et respectées par le plus grand nombre des samouraïs. Mieux, les rares textes, formulant et dégageant une éthique propre aux samouraïs (le Hagakure de Yamamoto Tsunetomo et les écrits de Yamaga Sôkô) tous deux intégrés dans le canon des textes de l’idéologie du bushidô, n’ont eu aucune influence avant le XXe siècle.

Le terme « bushidô », utilisé en ce sens serait apparue pour la première fois dans le koyo gunkan, la chronique militaire de la province du Kai dirigée par le célèbre clan des Takeda (la chronique a été compilée par Kagenori Obata (1572-1663), le fils d’un imminent stratège du clan à partir de 1615. L’historien japonais Yamamoto Hirofumi (Yamamoto Hirofumi, Nihonjin no kokoro : bushidô nyûmon, Chûkei éditions, Tôkyô, 2006), constata au cours de ses recherches l’absence, à l’époque moderne, de textes formulant une éthique des guerriers qui auraient pu être accessibles et respectées par le plus grand nombre des samouraïs. Mieux, les rares textes, formulant et dégageant une éthique propre aux samouraïs (le Hagakure de Yamamoto Tsunetomo et les écrits de Yamaga Sôkô) tous deux intégrés dans le canon des textes de l’idéologie du bushidô, n’ont eu aucune influence avant le XXe siècle.

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

Lo sorprendente es la capacidad de los dragones de unir lo positivo y lo negativo. Matan a los seres humanos, pero son capaces de resucitarles, y devuelven la vida a un ser que está mucho más abajo en la evolución. Por otro lado, vemos que poco significa la vida humana, según el cuento, menos que la de un pájaro. El cuento está lleno de contrastes. Uno de ellos es el personaje del soldado – dragón: asesino y salvador a la vez. Ya la misma ciudad, el espacio en el que se desarrolla la acción está lleno de contradicciones. La ciudad arde, pero está helada. Tenemos las dos fuerzas ancestrales luchando. Estamos en invierno, y la ciudad está congelada, muerta, parada. Al mismo tiempo, el fuego de la revolución la despierta, “ la hace vivir “. Las llamas derriten el hielo, que es la capa que oprime todo, pero también queman, matan.

Lo sorprendente es la capacidad de los dragones de unir lo positivo y lo negativo. Matan a los seres humanos, pero son capaces de resucitarles, y devuelven la vida a un ser que está mucho más abajo en la evolución. Por otro lado, vemos que poco significa la vida humana, según el cuento, menos que la de un pájaro. El cuento está lleno de contrastes. Uno de ellos es el personaje del soldado – dragón: asesino y salvador a la vez. Ya la misma ciudad, el espacio en el que se desarrolla la acción está lleno de contradicciones. La ciudad arde, pero está helada. Tenemos las dos fuerzas ancestrales luchando. Estamos en invierno, y la ciudad está congelada, muerta, parada. Al mismo tiempo, el fuego de la revolución la despierta, “ la hace vivir “. Las llamas derriten el hielo, que es la capa que oprime todo, pero también queman, matan.

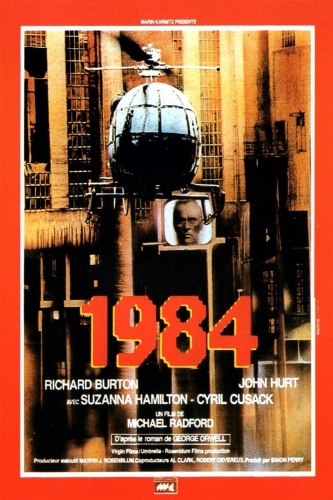

En manipulant les archives, l’on manipule les consciences. Il suffit pour cela de « rectifier » le passé en l’alignant sur les nécessités politiques de l’heure. Si d’aventure il arrive que la mémoire individuelle contredise la mémoire collective ainsi façonnée, la contradiction doit être résolue au profit de la seconde par l’élimination de la première. D’où l’utilité de la « double pensée » pour assurer le triomphe de l’orthodoxie. Il n’y a plus ni réalité ni objectivité. Selon les termes même d’O’Brien, « la réalité n’est pas extérieure. La réalité existe dans l’esprit humain et nulle part ailleurs... Tout ce que le parti tient pour la vérité est la vérité ». Par cette perversion totale de l’histoire et de la conscience historique, on atteint le point extrême de la logique totalitaire.

En manipulant les archives, l’on manipule les consciences. Il suffit pour cela de « rectifier » le passé en l’alignant sur les nécessités politiques de l’heure. Si d’aventure il arrive que la mémoire individuelle contredise la mémoire collective ainsi façonnée, la contradiction doit être résolue au profit de la seconde par l’élimination de la première. D’où l’utilité de la « double pensée » pour assurer le triomphe de l’orthodoxie. Il n’y a plus ni réalité ni objectivité. Selon les termes même d’O’Brien, « la réalité n’est pas extérieure. La réalité existe dans l’esprit humain et nulle part ailleurs... Tout ce que le parti tient pour la vérité est la vérité ». Par cette perversion totale de l’histoire et de la conscience historique, on atteint le point extrême de la logique totalitaire.

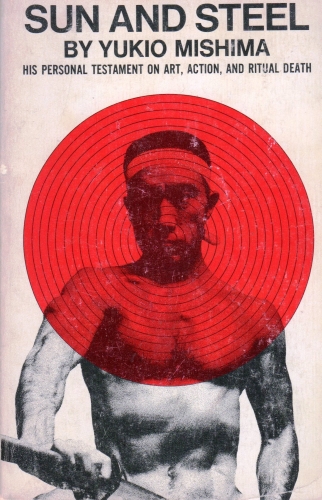

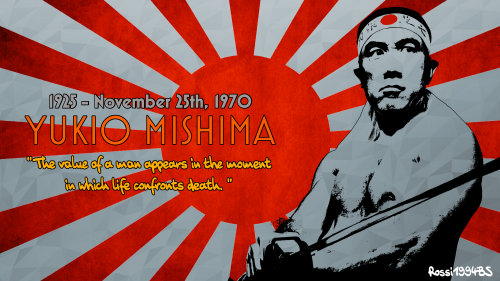

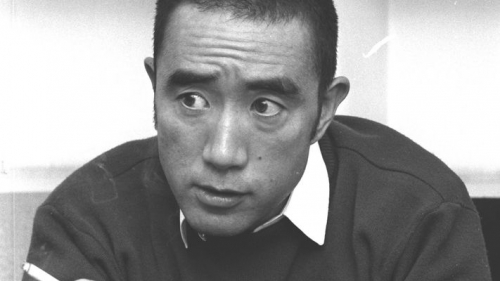

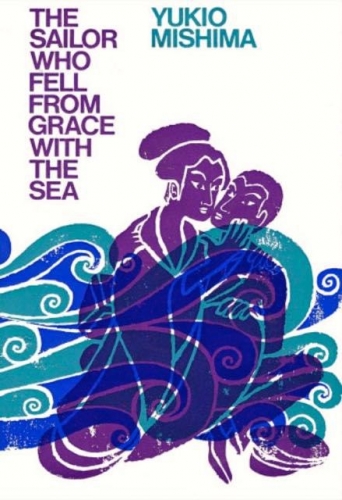

If we take these words out of context but relate them to certain ideas held by Mishima, then these worlds can equally equate to the changing landscape of Japan based on skyscrapers and the dilution of faith and philosophy. In other words, maybe Japan had learned everything under the Meiji Restoration based on the hypocrisy of Western, Catholic, and Islamic empires that utilized fear and control at the drop of a hat. Of course, while Islamization followed the Ottomans and Catholicism followed the Spanish – the British view was that you didn’t have to enslave one hundred percent by destroying indigenous faiths. Instead, the essence of the British Empire was to exploit resources at all costs – while destroying the soul of poor indigenous British nationals based on child labor, the workhouse, and a host of other barbaric realities.

If we take these words out of context but relate them to certain ideas held by Mishima, then these worlds can equally equate to the changing landscape of Japan based on skyscrapers and the dilution of faith and philosophy. In other words, maybe Japan had learned everything under the Meiji Restoration based on the hypocrisy of Western, Catholic, and Islamic empires that utilized fear and control at the drop of a hat. Of course, while Islamization followed the Ottomans and Catholicism followed the Spanish – the British view was that you didn’t have to enslave one hundred percent by destroying indigenous faiths. Instead, the essence of the British Empire was to exploit resources at all costs – while destroying the soul of poor indigenous British nationals based on child labor, the workhouse, and a host of other barbaric realities. Mishima said, “If we value so highly the dignity of life, how can we not also value the dignity of death? No death may be called futile.”

Mishima said, “If we value so highly the dignity of life, how can we not also value the dignity of death? No death may be called futile.”

Ernst Jünger appartient incontestablement à ces lettrés allemands qui s’enracinent dans l’âme germanique afin de mieux la dépasser et ainsi accéder au psyché européen. C’est ce qu’avait compris Dominique Venner dans son Ernst Jünger. Un autre destin européen (Éditions du Rocher, coll. « Biographie », 2009). Venner oublie néanmoins d’évoquer la sortie en 1962 de L’État universel dans lequel Jünger ne cache pas ses intentions mondialistes. « Un mouvement d’importance mondiale, y écrit-il, est, de toute évidence, en quête d’un centre. […] Il s’efforce d’évoluer des États mondiaux à l’État universel, à l’ordonnance terrestre ou globale (L’État universel suivi de La mobilisation totale, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 1990, p. 40). » Pour Jünger, la saturation maximale de la Technique et l’assomption du Travailleur aboutissent à l’État universel. Pourtant, l’intrigue du roman de 1977, Eumeswil, se déroule dans une ère post-historique survenue après l’effondrement de l’État universel et la renaissance des cités-États.

Ernst Jünger appartient incontestablement à ces lettrés allemands qui s’enracinent dans l’âme germanique afin de mieux la dépasser et ainsi accéder au psyché européen. C’est ce qu’avait compris Dominique Venner dans son Ernst Jünger. Un autre destin européen (Éditions du Rocher, coll. « Biographie », 2009). Venner oublie néanmoins d’évoquer la sortie en 1962 de L’État universel dans lequel Jünger ne cache pas ses intentions mondialistes. « Un mouvement d’importance mondiale, y écrit-il, est, de toute évidence, en quête d’un centre. […] Il s’efforce d’évoluer des États mondiaux à l’État universel, à l’ordonnance terrestre ou globale (L’État universel suivi de La mobilisation totale, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 1990, p. 40). » Pour Jünger, la saturation maximale de la Technique et l’assomption du Travailleur aboutissent à l’État universel. Pourtant, l’intrigue du roman de 1977, Eumeswil, se déroule dans une ère post-historique survenue après l’effondrement de l’État universel et la renaissance des cités-États.

Noboru is fascinated with the sea and ships. He convinces his mother to take him to a port, where a sailor by the name of Ryuji Tsukazaki, second mate aboard a freighter ship, shows him around his ship. The reader is introduced to Ryuji when Fusako invites him to the Kurodas’ home and Noboru observes the two embracing through a hole in the wall behind a chest in his bedroom.

Noboru is fascinated with the sea and ships. He convinces his mother to take him to a port, where a sailor by the name of Ryuji Tsukazaki, second mate aboard a freighter ship, shows him around his ship. The reader is introduced to Ryuji when Fusako invites him to the Kurodas’ home and Noboru observes the two embracing through a hole in the wall behind a chest in his bedroom.

The narrator, Mizoguchi, is physically weak, ugly in appearance, and afflicted with a stutter. This isolates him from others, and he becomes a solitary, brooding child. He first learns of the Golden Temple from his father, a frail country priest, and the image of the temple and its beauty becomes for him an idée fixe. The young Mizoguchi worships his vision of temple, but there are omens of what is to come. When a naval cadet visits his village and notices his stutter, Mizoguchi is resentful and retaliates by defacing the cadet’s prized scabbard. From the beginning, he realizes that the beauty of the temple represents an unattainable ideal: “if beauty really did exist there, it meant that my own existence was a thing estranged from beauty” (21). Over time, this seed in his mind metastasizes and begins to consume him.

The narrator, Mizoguchi, is physically weak, ugly in appearance, and afflicted with a stutter. This isolates him from others, and he becomes a solitary, brooding child. He first learns of the Golden Temple from his father, a frail country priest, and the image of the temple and its beauty becomes for him an idée fixe. The young Mizoguchi worships his vision of temple, but there are omens of what is to come. When a naval cadet visits his village and notices his stutter, Mizoguchi is resentful and retaliates by defacing the cadet’s prized scabbard. From the beginning, he realizes that the beauty of the temple represents an unattainable ideal: “if beauty really did exist there, it meant that my own existence was a thing estranged from beauty” (21). Over time, this seed in his mind metastasizes and begins to consume him. All human beings possess a will to power in the Nietzschean sense. This finds its highest expression in self-actualization and self-mastery, and in the achievements of great artists, thinkers, and leaders, but in its lower forms is embodied by the desire of defective beings to assert themselves at all costs. This is manifested in Mizoguchi’s desire to destroy the temple, which intensifies in proportion to his realization that he will never be able to possess it or approach its beauty.

All human beings possess a will to power in the Nietzschean sense. This finds its highest expression in self-actualization and self-mastery, and in the achievements of great artists, thinkers, and leaders, but in its lower forms is embodied by the desire of defective beings to assert themselves at all costs. This is manifested in Mizoguchi’s desire to destroy the temple, which intensifies in proportion to his realization that he will never be able to possess it or approach its beauty.

News of Seth’s victory reaches London where Basil Seal, the ne’er-do-well son of the Conservative Whip and a classmate of Seth’s at Oxford, is recovering from a series of scandalous benders that have forced him to abandon his nascent political career. Desperately in need of money, Seal travels to Azania as a free-lance journalist. Within a short time of his arrival, Basil becomes Seth’s most trusted adviser and is put in charge of the Ministry of Modernization; in effect, Basil has become the real ruler of Azania since Seth spends his time immersed in catalogs and dreaming up more and more ridiculous “progressive” schemes for the betterment of Azanians, such as requiring all citizens to learn Esperanto. The natives who run the other departments are all too happy to refer all business to Basil.

News of Seth’s victory reaches London where Basil Seal, the ne’er-do-well son of the Conservative Whip and a classmate of Seth’s at Oxford, is recovering from a series of scandalous benders that have forced him to abandon his nascent political career. Desperately in need of money, Seal travels to Azania as a free-lance journalist. Within a short time of his arrival, Basil becomes Seth’s most trusted adviser and is put in charge of the Ministry of Modernization; in effect, Basil has become the real ruler of Azania since Seth spends his time immersed in catalogs and dreaming up more and more ridiculous “progressive” schemes for the betterment of Azanians, such as requiring all citizens to learn Esperanto. The natives who run the other departments are all too happy to refer all business to Basil.

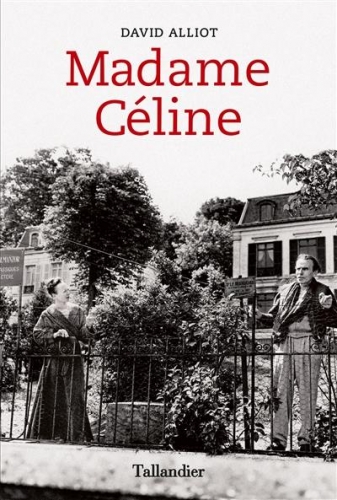

Il y a quelques années, André Derval a signé un recueil des critiques parues en 1938 sur Bagatelles pour un massacre (Éd. Écriture). Curieusement l’article d’Emmanuel Berl, paru le 21 janvier de cette année-là, n’y figure pas. Article pourtant connu des céliniens pour avoir été recensé par J.-P. Dauphin dès 1977 (Minard éd.). Et puis, Berl, ce n’est tout de même pas une petite pointure. Éviction due au fait que sa critique de Bagatelles empruntait le mode du pastiche ? Toujours est-il qu’elle est peu banale compte tenu des origines de l’auteur. Cet article, exhumé ici même par Éric Mazet il y a un an, se conclut par cette constatation: « Le lyrisme emporte dans son flux la malice et la méchanceté », ce qui était assez bien vu. Et de conclure : « Juif ou pas juif, zut et zut ! j’ai dit que j’aimais Céline. Je ne m’en dédirai pas. » Curieux personnage que ce Berl marqué comme Destouches par la Grande Guerre, comme lui, pacifiste viscéral (et donc partisan des accords de Munich au grand dam de ses coreligionnaires). Et qui rédigera, autre paradoxe, deux allocutions de Pétain en juin 40. En 1933, il avait vainement sollicité la collaboration de Céline à l’hebdomadaire (de gauche) Marianne qu’il dirigeait mais obtint l’autorisation d’y publier le discours de Médan. Lorsqu’en mai 1939, le décret Marchandeau entraîne le retrait de la vente des pamphlets, Berl s’insurge : « Qu’il soit antisémite, je le déplore. Pour ma part, je l’ai déjà dit, je ne serai pas anticélinien » (!). C’est que ce philosophe égaré en politique n’était pas un sectaire: non seulement il apprécie ses adversaires mais en outre admet l’idée de l’antisémitisme politique. En écho, Céline lui aurait adressé cette promesse : « Tu ne seras pas pendu. Tu seras Führer à Jérusalem. Je t’en donne ma parole. » (De la même manière, Céline eut des échanges furieux avec Jean Renoir, dont il détestait l’idéologie diffusée dans ses films, et… qui était payé en retour par l’admiration indéfectible du cinéaste pour le romancier.)

Il y a quelques années, André Derval a signé un recueil des critiques parues en 1938 sur Bagatelles pour un massacre (Éd. Écriture). Curieusement l’article d’Emmanuel Berl, paru le 21 janvier de cette année-là, n’y figure pas. Article pourtant connu des céliniens pour avoir été recensé par J.-P. Dauphin dès 1977 (Minard éd.). Et puis, Berl, ce n’est tout de même pas une petite pointure. Éviction due au fait que sa critique de Bagatelles empruntait le mode du pastiche ? Toujours est-il qu’elle est peu banale compte tenu des origines de l’auteur. Cet article, exhumé ici même par Éric Mazet il y a un an, se conclut par cette constatation: « Le lyrisme emporte dans son flux la malice et la méchanceté », ce qui était assez bien vu. Et de conclure : « Juif ou pas juif, zut et zut ! j’ai dit que j’aimais Céline. Je ne m’en dédirai pas. » Curieux personnage que ce Berl marqué comme Destouches par la Grande Guerre, comme lui, pacifiste viscéral (et donc partisan des accords de Munich au grand dam de ses coreligionnaires). Et qui rédigera, autre paradoxe, deux allocutions de Pétain en juin 40. En 1933, il avait vainement sollicité la collaboration de Céline à l’hebdomadaire (de gauche) Marianne qu’il dirigeait mais obtint l’autorisation d’y publier le discours de Médan. Lorsqu’en mai 1939, le décret Marchandeau entraîne le retrait de la vente des pamphlets, Berl s’insurge : « Qu’il soit antisémite, je le déplore. Pour ma part, je l’ai déjà dit, je ne serai pas anticélinien » (!). C’est que ce philosophe égaré en politique n’était pas un sectaire: non seulement il apprécie ses adversaires mais en outre admet l’idée de l’antisémitisme politique. En écho, Céline lui aurait adressé cette promesse : « Tu ne seras pas pendu. Tu seras Führer à Jérusalem. Je t’en donne ma parole. » (De la même manière, Céline eut des échanges furieux avec Jean Renoir, dont il détestait l’idéologie diffusée dans ses films, et… qui était payé en retour par l’admiration indéfectible du cinéaste pour le romancier.)