Abel Bonnard ou l’exemple de la cohérence

par Philippe Baillet

Ex: http://www.zentropa.info

« Croyez-moi, les hommes qui par leurs sentiments appartiennent au passé, et par leurs pensées à l’avenir, trouvent difficilement leur place dans le présent » (Louis de Bonald à Joseph de Maistre, 22 mars 1817)

« Nous n’aimons que les choses rares, les pierres, le cristal pareil à du soleil gelé, le corail, sceptre de l’aurore, les perles, larmes de la lune » (Abel Bonnard)

« L’homme considère les actes, mais Dieu pèse les intentions » (Imitation de Jésus-Christ, II, 6, 2)

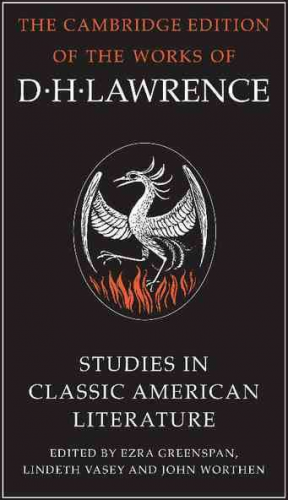

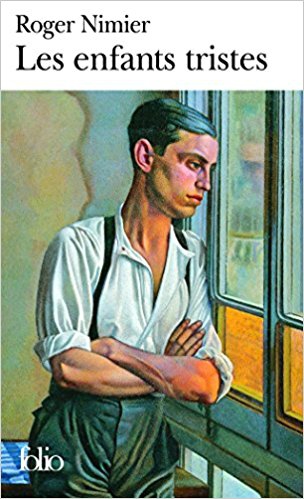

Les Modérés sont l’ouvrage le plus célèbre d’Abel Bonnard (1883-1968), le meilleur aussi et le plus important, de l’avis unanime de ceux qui s’intéressent à son œuvre. Sa parution chez Grasset en 1936 marque un tournant décisif dans la vie et l’œuvre de Bonnard. on que celui-ci ne se fût jamais soucié auparavant de la politique, mais il l’avait fait jusque-là de façon marginale, soit par des articles, donnés pour l’essentiel au Figaro et au Journal des débats(accessoirement aussi à la Revue de Paris), soit à travers des digressions et réflexions glissées dans ses nombreux récits de voyages. Il importe d’insister sur ce point, pour ne pas faire de Bonnard ce qu’il ne fut pas : un théoricien ou un doctrinaire. Il fut avant tout un artiste et un esthète, et son engagement politique à partir de 1936 ne doit pas cacher ce qui demeura toujours, pour lui, sa raison de vivre. Parvenu au soir de sa vie, Bonnard déclare le 22 mars 1960 devant la Haute Cour de justice : « … je puis assurer que, toutes les fois que j’ai exercé une activité politique, je m’y suis livré sans réserve, mais non pas tout entier, car la partie profonde de mon être restait toujours attachée à l’activité littéraire et artistique que je considérais comme la plus haute justification de mon existence » (1).

Les Modérés sont en fait l’aboutissement d’une longue réflexion, entamée vingt ans plus tôt environ, sur les malheurs de la France et leurs causes lointaines, sur la montée aussi d’une espèce de nouvelle barbarie universelle destinée à effacer tout ordre et toute civilisation dignes de ce nom. Face à l’uniformisation croissante des modes de vie et des cultures, face à la laideur qui s’étend partout, le clerc authentique est appelé à témoigner pour les valeurs de l’esprit, d’abord en se faisant le chantre du retour à l’ordre et le défenseur de la civilisation.

Les Modérés ont pour sous-titre Le drame du présent. Le caractère dramatique du XXe siècle est presque une obsession chez Bonnard. Son époque lui paraît dramatique pour la France — parvenue, dit-il dans le présent livre, « au terme d’une phase de son histoire, qui a ses commencements visibles au XVIIIe siècle » —, d’autant plus que s’y ajoute le « défaut, si répandu parmi les Français, de ne pas ressentir un drame dramatiquement ». « Ils oublient », en effet, « que, dans une tragédie, tout est question de temps ». Cette époque est dramatique également pour l’homme européen, et même pour l’homme blanc en général : reculant sur tous les fronts, il est contraint de se redéfinir impérativement.

On cherchera donc à expliquer pourquoi Bonnard, brillant causeur de salon dont le sens de la repartie et les mots d’esprit faisaient la joie des “gens du monde”, est devenu le contempteur impitoyable du triomphe de la rhétorique, mal français par excellence. Pourquoi, en somme, ce « petit monsieur, tiré à quatre épingles, au complet très repassé, aux bottines à tiges, à la cravate soyeuse, à la chevelure très floue, très grise, très ramenée, à la voix fluette » (3), ne faisait qu’un avec l’homme qui, le 30 janvier 1943, achève ainsi un discours prononcé devant les rugueux chefs miliciens réunis à Marseille : « Camarades, la Révolution ne se fera pas toute seule. Elle se fera parce que nous la ferons, la Révolution nécessaire, la Révolution sacrée, la Révolution de renaissance » (4).

À l’écart des modes et des chapelles

Ce qui frappe sans doute le plus lorsqu’on essaie de prendre une vue d’ensemble de l’œuvre et de la personne d’Abel Bonnard, c’est une singulière indépendance d’esprit. Bonnard donne toujours l’impression de traverser les salons littéraires et artistiques, qu’il fréquenta pourtant en grand nombre, comme s’ils n’avaient d’autre raison d’être que de lui permettre de satisfaire sa curiosité et d’approfondir sa connaissance des hommes. Jusqu’au début des années trente, il n’est pas touché par le virus de la politique, et l’esprit de chapelle, qui exerce déjà tant de ravages, lui demeure profondément étranger. De son “splendide isolement” intellectuel, Bonnard avait une conscience très nette. C’est ainsi qu’il écrit le 5 mars 1940 à l’un de ses lecteurs les plus attentifs, l’abbé irlandais Farnar : « Je crois que ce qui me caractérise, sans que je songe à me prévaloir le moins du monde de ce trait particulier, c’est que je me suis toujours formé hors des influences de mon temps, et aussi loin des modes courantes que des étroites chapelles » (5).

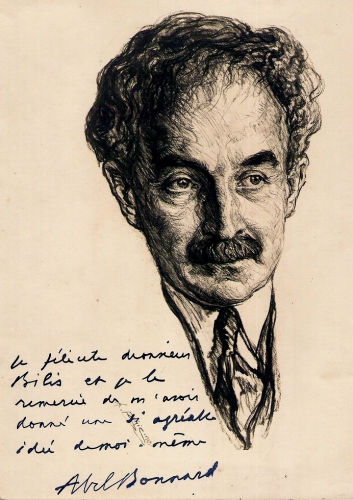

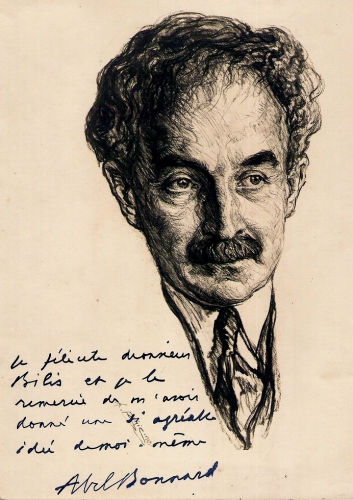

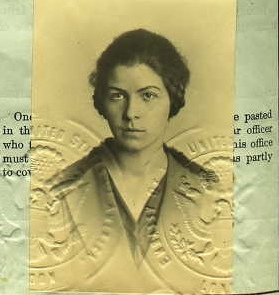

Bonnard naît à Poitiers le 19 décembre 1883. Il est le fils selon l’état-civil d’Ernest Bonnard, ancien gardien de prison devenu directeur des prisons de la Vienne. Son vrai père, comme l’a établi Olivier Mathieu, est Joseph Napoléon Primoli, né à Rome le 2 mai 1851, arrière-petit-fils, par sa mère, de Lucien et Joseph Bonaparte. Mécène, collectionneur, bibliophile, Primoli se piquait volontiers de littérature et collabora notamment à la Revue des Deux Mondes et à la Revue de Paris. Après avoir vécu à Marseille à partir de l’année 1893, Abel Bonnard s’installe à Paris en 1900. Il sera élève au lycée Henri-IV, puis en khâgne à Louis-le-Grand. Il échoue au concours d’entrée de l’École Normale Supérieure, se contentant d’une modeste licence ès Lettres. Déjà attiré par l’histoire de l’art, il va bientôt suivre les cours de l’École du Louvre.

Il publie son premier recueil de poèmes, Les Familiers, en 1906. Le poète François Coppée salue la qualité de ces pièces où s’exprime l’amour de Bonnard pour les animaux. Dans les années qui précèdent la Première Guerre mondiale, Bonnard entame une carrière journalistique au Figaro. C’est à cette époque qu’il noue de nombreuses relations dans les milieux littéraires, faisant la connaissance d’Anna de Noailles, Proust (avec qui il correspond pendant plusieurs années), Morand, Alfred Fabre-Luce, D’Annunzio, Barrès, Bergson, André Maurois. Plus tard, il connaîtra aussi Cocteau et Julien Benda et se liera d’amitié — point qui n’est pas sans intérêt — avec des auteurs d’origine juive comme le dramaturge Henri Bernstein et l’écrivain André Suarès.

Lorsque la guerre éclate, Bonnard, ambulancier, demande à passer au service armé. Simple soldat en Champagne jusqu’en 1916, il est ensuite nommé officier et plus précisément commissaire de la Marine sur le Marceau, basé à Brindisi. Son patriotisme et son comportement au front lui valent la Croix de Guerre, la Légion d’Honneur et plusieurs citations. À l’époque, Bonnard n’est pas spécialement germanophile. En 1918, il écrit par exemple dans son Journal, à propos des Allemands : « … il faut être aussi peu cultivé que certains de leurs docteurs pour croire à une race élue qui va régenter la terre » (6).

Dans le même Journal, intitulé Caractère de la guerre et toujours inédit, Bonnard impute aux philosophes du XVIIIesiècle la perte du « sens profond de la destinée », du « sentiment amer et grand du drame humain ». Les jugeant responsables d’une « vulgarisation » et d’une « laïcisation de la pensée », il affirme nettement que la pensée, pour ne pas déchoir, doit demeurer un exercice solitaire et désintéressé. Le modèle traditionnel du clerc occupé à ne réfléchir que sur les questions métaphysiques doit recouvrer toute sa dignité, après que « les philosophes se sont mis à penser à plusieurs, avec les autres, pour les autres ». Or, pour Bonnard, « on ne pense pas en commun » (7).

Bonnard constate par ailleurs, avec amertume, que le sursaut national provoqué par la guerre, qui a rappelé les Français au sens de la discipline et à l’esprit de sacrifice, s’est aussitôt perdu dans les méandres de la routine parlementaire, une fois la paix revenue. « De tous les régimes des peuples en guerre — écrit-il alors —, celui de la France est celui qui a le moins consenti à se modifier, et pourtant la guerre n’a été aussi tragique pour aucune autre nation que pour la France qui a eu la Mort à sa porte » (8). On voit déjà se dessiner ici l’un des thèmes récurrents de la critique politique de Bonnard : la République française, nonobstant sa rhétorique héritée de 89, est un régime profondément conservateur, mais conservateur du pire.

À la même époque pourtant, Bonnard, revenant sur l’affaire Dreyfus, y trouve rétrospectivement matière à tempérer son pessimisme. Les événements lui donneront tort, mais il n’est pas indifférent de savoir, pour mieux comprendre les raisons de son futur engagement politique, ce qu’elle signifia pour lui : « Ce triomphe de la mystique républicaine fut comme bien des triomphes : ce fut une fin. Là pour la dernière fois les idées républicaines, égalitaires, mystiques, apparurent avec le prestige étincelant, avec l’ascendant des idées à qui l’avenir et le présent appartiennent. Là pour la dernière fois les idées contraires d’ordre, de discipline, d’autorité, apparurent avec on ne sait quoi de suranné ou d’étroit, un manque d’ascendant, quelque chose d’embarrassé, de gêné, d’un peu ridicule, de caduc » (9).

C’est également du lendemain de la Première Guerre mondiale que datent les premiers articles donnés par Bonnard au Journal des débats, hebdomadaire à l’audience relativement restreinte mais jouissant d’un certain prestige. Cette collaboration régulière se poursuivra jusqu’au milieu des années trente. En 1928, Bonnard publiera, à 150 exemplaires seulement, un recueil rassemblant cinquante-quatre de ses chroniques parues dans le Journal des débats, sous le titre Le Solitaire du toit (toujours le “splendide isolement” !), recueil dont on ne peut que souhaiter vivement une prochaine réédition. Pendant quinze ans, de 1918 à 1933, Bonnard va faire de nombreux voyages, souvent sous la forme de croisières. D’un long séjour de huit mois, en 1920-21, dans l’ex-“Empire du Milieu”, il rapporte les matériaux de son premier grand livre, En Chine (1924), qui vaut à son auteur le grand prix de littérature décerné par l’Académie française. En Chine sera suivi de Au Maroc (1927), Océan et Brésil (1929), Rome (1931),Navarre et vieille Castille (1937), Le Bouquet du monde (1938).

Toujours dans les années vingt, période décidément très fertile dans la vie de Bonnard, celui-ci fait paraître une série de courts essais, à vrai dire de valeur inégale : La vie amoureuse d’Henri Beyle (1926), L’Amitié et L’Argent(1928), sans oublier un très réactionnaire Éloge de l’ignorance (1926) et, surtout, un remarquable Saint François d’Assise (1929) aux antipodes de l’hagiographie fade et stéréotypée. À l’époque, Bonnard est un auteur connu, qui ne semble pas avoir rencontré de difficultés particulières pour se faire publier, souvent, par les plus grands éditeurs : Flammarion, Fayard, Hachette, Albin Michel.

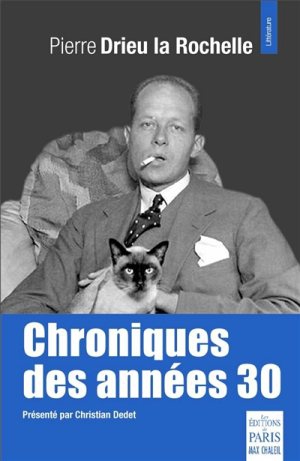

En 1936, on est donc encore loin du ton très militant adopté par Bonnard devant les chefs miliciens. Mais ce lettré solitaire, élu à l’Académie française en 1932 et reçu sous la Coupole le 16 mars1933, s’engage de plus en plus. Le 4 octobre 1935, il figure parmi les signataires du Manifeste des intellectuels français pour la défense de la paix en Europe ; l’année où paraissent Les Modérés, il préface un recueil, L’Éducation et l’idée de patrie, que publie le Cercle Fustel de Coulanges, proche de l’Action française ; en 1937, il devient président des Cercles populaires français, côtoyant dans cette courroie de transmission du PPF de Jacques Doriot à destination des intellectuels, des hommes comme Bertrand de Jouvenel, Alexis Carrel, Ramon Fernandez, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Robert Brasillach. Peu après, il fait partie d’un comité de défense des cagoulards emprisonnés après l’arrestation de membres de la Cagoule en novembre et décembre 1937.

Quand il arrive à la culture officielle de parler de Bonnard, c’est uniquement pour évoquer cet engagement et les responsabilités qu’il assuma sous le régime de Vichy, au détriment de son œuvre littéraire, qu’elle ignore systématiquement. Les idées et les choix politiques de Bonnard ayant donné lieu à des condamnations unilatérales ou à des apologies délirantes et simplificatrices (10), il convient de profiter de cette troisième édition des Modérés pour en étudier les origines et en dégager les grandes lignes, alors qu’on assiste à un regain d’intérêt pour son auteur (11).

À la recherche de la doctrine perdue

Très tôt, Bonnard a perçu que ce qui manquait aux défenseurs de l’ordre en Occident au XXe siècle, c’était une doctrine. Dans son Journal intime de soldat de la Grande Guerre, il écrit : « … si le régime politique va s’affaiblissant en France toujours davantage […], il ne faut pas en conclure que sa ruine soit inévitable. […] Les éléments qui lui sont hostiles ne disposent pas d’une doctrine positive sur laquelle se rassembler : ils restent épars » (12). Cette appréciation revient fréquemment dans ses écrits des années vingt, où elle est même étendue à l’Occident dans son ensemble. C’est ainsi qu’on lit dans En Chine : « Parmi toutes les causes de faiblesse qui affectent l’action des nations blanches, la plus profonde, de beaucoup, est de n’avoir pas de doctrine » (13). Et plus loin, à propos de l’homme blanc : « C’est seulement lorsqu’il se sera refait une doctrine qu’il sera, à la fois, plus noble et plus fort » (14).

Si Bonnard ne se montre pas plus précis sur ce qu’il entend par “doctrine”, c’est sans doute parce que sa nature artiste répugne à la démonstration et aux syllogismes. Mais sa sensibilité nous laisse deviner que, conscient de la crise très profonde engendrée par les Lumières et par le ralliement à celles-ci d’une grande partie de la noblesse française, il a compris que l’idée d’ordre ne retrouvera son prestige qu’en s’appuyant sur des enseignements immémoriaux et universels, valables partout et toujours. Il affirmera dans Les Modérés : « On voit de quelle importance a été la victoire des philosophes au XVIIIe siècle ; ils ont découronné l’ordre pour longtemps : ils l’ont décrédité dans l’âme même de ses défenseurs ». Ceux-ci désormais, pour être à la hauteur du drame universel qui se joue, doivent opposer à la cohorte des fils légitimes et illégitimes des Lumières les plus hautes productions de l’esprit : cela signifie qu’il leur faut faire appel à l’œuvre de Maurras et à l’école contre-révolutionnaire du XIXesiècle, mais plus encore à La République de Platon, à la Politique d’Aristote, à saint Thomas d’Aquin et au Dante du De Monarchia, ou encore — pourquoi pas ? — au Tao Te King de Lao-tseu et à l’Arthashâstra indien, tous textes de la “politique traditionnelle” qui ignorent superbement les anti-principes démocratiques.

L’esprit du temps est en outre propice à l’évasion. Au début des années vingt, Bonnard, comme bien d’autres, ressent l’appel de l’Asie, dont il dit dans En Chine : « Au moment où le matérialisme moderne envahissait son domaine, elle s’emparait, en Europe, de tous ceux que ce matérialisme comblait de dégoût » (15). Il est en cela le compagnon d’esprits aussi différents que Romain Rolland, Hermann von Keyserling, René Guénon, Julius Evola, René Daumal, etc.

On peut d’ailleurs observer sans plus attendre que, dans le domaine oriental, Bonnard faisait preuve d’un jugement très sûr, ne confondant pas les élucubrations de Madame Blavatsky et de sa Société Théosophique, ou les cosmologies syncrétistes et embrouillées de Rudolf Steiner, avec les enseignements traditionnels. Son jugement sur Keyserling — personnage surfait qui eut précisément son heure de gloire dans les années vingt — recoupe parfaitement celui de Julius Evola, auteur avec lequel Bonnard, il est vrai, présente plus d’un point commun (16). Bonnard écrit en effet à propos du pontifiant “penseur” germano-balte : « L’explicateur international, le conférencier universel. […] Il ne pense plus, il se répète, cartonné et magistral. Les livres où il explique tout, écrits à la hâte, sans examen sérieux, il les appelle ses méditations. Ce fabricant fournit des idées générales à des gens qui n’en ont pas de particulières » (17). Cette “bonnardise” d’une ironie mordante est confirmée par Evola, qui eut l’occasion de rencontrer Keyserling : « Le fait de le connaître directement me fit voir clairement que j’avais en face de moi un simple “Philosophe de salon”, vaniteux, narcissique et présomptueux au-delà de toute description » (18).

Par sa façon de traduire partout dans la société la hiérarchie invisible présidant à l’ordonnance de l’univers, la Chine ancienne fait figure de modèle aux yeux de Bonnard : « jamais, peut-être, écrit-il, une société humaine n’a été plus étroitement liée à l’ordre du monde. Chaque fonctionnaire n’était que le dédoublement et la transfiguration d’un agent naturel. Chaque trouble de l’univers avertissait d’un dérangement dans l’État » (19).

En Asie, Bonnard rencontre également un trait qui s’accorde particulièrement bien à sa nature : la communion de l’homme avec tout ce qui est vivant. Elle a pour corollaire le rejet radical de l’individualisme, de tous les Moi dilatés qui étalent leur néant de fatuité sur les tristes tréteaux du monde moderne. Songeant à l’influence du bouddhisme sur la civilisation chinoise, Bonnard saisit admirablement ce qui fait la force de la conception extrême-orientale de la vie : « Le sentiment de la parenté des êtres, la croyance aux renaissances sans nombre, tout concourt à faire qu’un homme, heureux ou misérable, ne se confonde jamais complètement avec sa condition du moment. Il garde sur elle une supériorité passive et ne la considère que comme un vêtement emprunté, qu’il va bientôt rendre et changer au grand vestiaire » (20). Quelques années avant sa mort, dans l’un des quatre articles qu’il donna au Spectacle du Monde, Bonnard confessa toute sa reconnaissance envers saint François d’Assise qui, « en étendant si largement son amour sur tout ce qui vit, et particulièrement les animaux (…) répare en quelque mesure l’immense infériorité de l’âme européenne par rapport à l’âme asiatique », ajoutant aussitôt à cela une réflexion d’inspiration très “guénonienne” : « Sans doute, on trouverait dans le catholicisme du Moyen Âge quelques témoignages des mêmes tendances, car il ne faut pas oublier qu’en dépit de la différence des religions, l’âme du Moyen Âge et celle de l’Asie se sont étendues sur le même plan, et c’est la Renaissance qui a rompu cette continuité, par la prépondérance qu’elle a donnée à l’homme comme être de raison » (21).

Chez Bonnard, l’amour de l’Asie allait donc bien au-delà de l’attirance esthétique pour les laques, ou les étoffes et les estampes dont il tapissa son cabinet de travail. Son livre sur la Chine prouve qu’il avait lu les meilleurs sinologues de l’époque et l’on sait qu’il était abonné au Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. En 1925, il rend compte élogieusement, dans le journal des Débats, d’un ouvrage de René Guénon, L’Homme et son devenir selon le Vêdânta, qu’il range parmi les livres pouvant donner de l’Asie « une idée profonde et vraie » (22). Quelques années plus tard, dans un numéro de la Nouvelle Revue Française consacré à Gobineau, Bonnard rend hommage en ces termes à l’auteur de l’essai intitulé Les Religions et les philosophies de l’Asie centrale : « Ayant moi-même cette Asie pour patrie personnelle et pour immense refuge, loin du vulgaire Occident, je lui suis reconnaissant d’avoir été l’un de ceux qui la dévoilèrent » (23). Les fracas de l’histoire ne pourront rien contre cette dilection qui, à elle seule, fait de Bonnard un cas à part au sein de la culture de droite en France au XXe siècle. Le 5 mars 1940, il écrit en effet à l’abbé Farnar qu’il rencontre en Extrême-Orient « des façons de comprendre la vie et de contempler le monde en m’associant à lui qui répondent à ma nature » (24).

La poésie de l’ordre

Bonnard, de toute évidence, ne partageait pas les vues anti-orientales de l’école maurrassienne, toujours prête à ne déceler que du “panthéisme” en dehors du catholicisme romain ou, au mieux, des formes de la “mystique naturelle” annonçant la Révélation chrétienne. Mais c’est surtout sa vision poétique de l’ordre qui l’éloigne de Maurras. Pour celui-ci, la solution monarchique est la conclusion nécessaire d’un raisonnement rigoureux, même si le sentiment y entre pour une part ; pour Bonnard, c’est d’abord une affaire de cœur. Il est en cela beaucoup plus proche — sinon par l’écriture, du moins par la sensibilité — des royalistes pré-maurrassiens, donc du légitimisme, qu’illustrèrent sur le mode de la nostalgie poignante des écrivains comme Barbey d’Aurevilly et Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. Bonnard dit d’ailleurs du mouvement légitimiste qu’il « fut certainement ce qu’il y eut de plus noble dans la vie politique de la France au XIXe siècle, précisément parce qu’il ne fut pas un parti, mais, dans le siècle des individus, la réunion des âmes fidèles qui gardaient la nostalgie d’un ordre plus réellement humain ».

« L’ordre est le nom social de la beauté » : partant de cet axiome, Bonnard définit ici, en quelques pages magnifiques, une sorte d’esthétique de l’ordre. Pour cela, il fait appel au général Gneisenau et à l’expression de son loyalisme envers le roi Frédéric-Guillaume de Prusse ; il évoque ses souvenirs d’avant la Première Guerre mondiale, lorsque, se promenant de nuit dans une capitale endormie, peuplée seulement des statues de ses héros et de quelques soldats veillant sur elles, il voyait alors « les deux extrémités d’une hiérarchie où tout se tenait ». Il n’y a en effet aucune contradiction, sinon pour les petits esprits qui réduisent la culture à l’exercice de l’intelligence, entre le service des armes et celui de l’art, le premier étant même, souvent, la condition indispensable à l’épanouissement du second. « Le soldat allait et venait régulièrement — écrit Bonnard — et j’écoutais avec plaisir son pas bien frappé résonner dans le solennel silence : il me semblait entendre les lourds spondées de ce poème de l’ordre, dont les dactyles délicats vibraient au haut des palais, dans le clair de lune ».

Une société noble est une société policée, dans tous les sens du terme. Et il est permis de penser que sa fréquentation assidue des cultures chinoise et japonaise renforça chez Bonnard son penchant pour la poésie de l’ordre, que résumaient si bien, au Japon, l’alliance du tranchant du sabre et de la pureté du chrysanthème dans l’âme du guerrier, ou le contraste entre la fragilité des pétales de la fleur de cerisier et la rigidité de l’armure du samouraï sur laquelle la brise les répand.

Il est significatif que Bonnard, dans l’un de ses derniers écrits, ait de nouveau fait appel à l’ancien Japon pour illustrer de façon particulièrement forte l’opposition entre monde de la Tradition et modernité. « On conservait, rappelle-t-il, au fond des familles nobles du Japon, des lames d’une trempe incomparable qui, au lieu des jolis fourreaux que l’art a concédés là-bas aux moindres poignards, n’ont pour gaines que de simples étuis de bois blanc, par un goût très japonais qui introduit parfois une affectation de rudesse parmi des raffinements infinis. Ces sabres sacrés représentaient, avec une force presque magique, l’honneur intraitable, le dévouement sans bornes, la fidélité sans conditions, la chevalerie la plus scrupuleuse. J’ai lu il y a quelque temps dans un journal qu’ils sont présentement recherchés et acquis par des Américains qui les emportent chez eux, où ils finiront comme des choses mortes dans une armoire ou une vitrine. Cette idée a suffi à me rendre triste tout un soir » (25).

Dans son remarquable essai consacré à plusieurs écrivains qui choisirent la voie de la Collaboration, Paul Sérant a dit de Bonnard : « Ses réflexions religieuses et métaphysiques sont dominées par le souci esthétique » (26). Cette remarque vaut plus encore pour ses idées politiques. Peut-être est-ce dans son livre sur saint François d’Assise que Bonnard a livré l’une des clés permettant de comprendre ses choix, lorsqu’il dit du Poverello, en qui le dépouillement s’associait à la délicatesse : « Comme pour toutes les âmes exquises, le Bien et le Mal devaient lui apparaître sous les espèces du Beau et du Laid » (27).

Or, la République est laide, puisqu’elle « ne peut pas organiser une cérémonie convenable. Cette répugnance esthétique pour un régime privé de toute majesté a pour pendant chez Bonnard le rejet quasi phobique du type humain qui en est comme le précipité final : l’“individu”.

“… Jusqu’à ce que la Révolution détruise la République, la République servira la Révolution”

Peu de livres vont aussi loin que Les Modérés dans la critique contre-révolutionnaire du régime républicain et de ses origines. Rien de la Révolution de 89 ne trouve grâce aux yeux de Bonnard : « Une nation qui veut vivre ne peut tirer de la Révolution française aucun principe de pensée ni de conduite », ne craint-il pas d’affirmer. La Révolution marque la grande rupture d’avec la vieille France, et la seule continuité existant entre l’Ancien Régime et la République est l’obstination dans les défauts de la noblesse du XVIIIe siècle : « La démocratie française est au bas des deux derniers siècles comme un marais sous une cascade : c’est la vulgarisation finale de toutes les erreurs qui ont d’abord enivré les gentilshommes et les beaux esprits ».

L’appartenance future de Bonnard au camp des ultras de la Collaboration n’autorise pas à sous-estimer la réalité de ses sentiments contre-révolutionnaires. Il a eu, certes, des mots favorables pour les régimes dictatoriaux d’Italie et d’Allemagne, mais où ne percent en vérité ni admiration ni enthousiasme. Nous dirons que Bonnard, par sa formation, ses lectures, ses inclinations profondes, ses fréquentations, venait de trop loin pour “tomber” dans le fascisme, a fortiori pour y voir une “Seconde Révolution”, éventuellement étendue à l’Europe tout entière, susceptible d’annuler les effets de la première en retournant contre elle les armes dont les Jacobins s’étaient servis.

Bonnard est contre-révolutionnaire par la nature même de l’analyse qu’il applique à la Révolution. Lorsqu’il la dépouille des oripeaux romantiques dont elle a été affublée depuis Michelet, il rejoint toute l’historiographie contre-révolutionnaire. Certaines de ses réflexions rappellent de très près Augustin Cochin. Témoin celle-ci : « Les révolutions sont les temps de l’humiliation de l’homme et les moments les plus matériels de l’histoire. Elles marquent moins la revanche des malheureux que celle des inférieurs. Ce sont des drames énormes dont les acteurs sont très petits ». Cette interprétation de la Révolution française comme entrée dans l’ère des masses et première étape d’un processus d’émergence de forces élémentaires infra-humaines qui vont échapper de plus en plus au contrôle des hommes, est un topos de la pensée contre-révolutionnaire, initialement énoncé par Joseph de Maistre dans un passage resté célèbre : « Enfin, plus on examine les personnages en apparence les plus actifs de la révolution, et plus on trouve en eux quelque chose de passif et de mécanique. On ne saurait trop le répéter, ce ne sont point les hommes qui mènent la révolution, c’est la révolution qui emploie les hommes. On dit fort bien, quand on dit qu’elle va toute seule » (28).

Pour Cochin également — qui fut le premier à mettre en relief le rôle joué, dans la Révolution française, par la “machine” impersonnelle que constituaient les sociétés de pensée —, sous la Révolution « le peuple-roi n’a pas connu de maîtres : ses meneurs ne sont que ses valets, ils le proclament à l’envi, et à les voir de près, on est tenté de les prendre au mot : car les gens de loi tirées de leurs études par la Révolution, qui font la leçon au roi tandis que le flot les porte, retombent à leur mesure dès qu’il les abandonne ; et cette mesure est médiocre. […] Le drame est sombre et poignant, mais joué par une troupe de province, et les situations sont plus grandes que les hommes » (29).

La conviction contre-révolutionnaire est si profonde chez Bonnard qu’au moment où la Troisième République, qui n’est que « de la Révolution ralentie et de la Terreur délayée », succombe sous le poids des circonstances auxquelles elle était bien incapable de faire face, cet incroyant pénétré du sens du sacré note dans son Journal, le 25 juin 1940 : « Si la France s’était repentie une seule fois depuis la Révolution, elle eût retrouvé son destin. Un sentiment profond l’eût ramenée aux vérités salutaires » (30). Ainsi le lettré féru de doctrines orientales, mais français par tout son être, retrouve-t-il une des idées maîtresses de la contre-révolution : l’expiation réparatrice de tous les “péchés” commis par la Révolution contre la France, “fille aînée de l’Église”.

On touche ici du doigt l’une des contradictions de Bonnard, plus sensible dans Les Modérés que partout ailleurs dans son œuvre : cet amoureux du Trône et de l’Autel n’a pas été touché par la grâce. Or, est-il possible d’être vraiment contre-révolutionnaire, quand on est Français, mais que l’on n’est pas catholique ? Bonnard a bien conscience, comme tout contre-révolutionnaire conséquent, de la filiation profonde qui rattache, en-deçà de l’écume des événements, la Révolution française à la Troisième République finissante, ainsi que le prouve ce passage des Modérés: « C’est une des lois les plus certaines de la politique que tout régime a un contenu d’idées et de sentiments qui, de son origine à sa fin, le forcent d’agir selon ce qu’il est […], et cette fatalité n’est jamais plus rigoureuse que lorsqu’il s’agit, comme c’est le cas pour la République française, d’un régime constitué dans les discordes civiles et né avec une âme de parti ».

Il est donc clair que pour Bonnard, tout redressement national effectif « suppose la disparition de la société française née de la démocratie » (31). Mais, parce qu’il n’est pas catholique, Bonnard ne se sent pas obligé de relier son rejet de la Révolution à une tradition religieuse, antérieure et supérieure à la pseudo-tradition républicaine, et de l’appuyer sur une base sociologique qui, qu’on le veuille ou non, appartient aux “tendances lourdes”, profondément enracinées, de la société française : la base que forment, précisément, les “catholiques de tradition”, lesquels étaient évidemment plus nombreux à l’époque des Modérés qu’aujourd’hui, mais peut-être moins conscients des raisons ultimes de leur combat. Cela aussi le sépare de l’Action française.

Bonnard ne se réfère pas non plus à la conception maurrassienne des “quatre États confédérés”, qui eût pu, en principe, lui fournir un argumentaire pour analyser la tare originelle du régime, qu’il énonce comme suit : « Le malheur de la République est d’être née dans la haine : elle date du moment où la France s’est divisée ». Pour Maurras, si la République est un régime de division intestine, c’est aussi parce qu’elle offre en France la particularité d’avoir servi à des minorités plus ou moins organisées à se pousser sur le devant de la scène, afin d’y occuper une place et d’y exercer une influence disproportionnées à leur consistance numérique et à leur contribution à l’ensemble de l’histoire de la nation française. Ébauchée dans L’Action française du 15 août 1904, reprise en 1906 dans Le Dilemme de Marc Sangnier et en 1921 dans La Démocratie religieuse, la conception maurrassienne vise à expliquer « ce qu’on appelle la continuité républicaine » par « l’hégémonie des quatre États confédérés — juif, protestant, maçon, métèque — dont trois au moins sont héréditaires » (32). Ces quatre États, véritables féodalités dans l’État, formeraient l’ossature du régime républicain, par-delà les partis, les étiquettes et les alliances de circonstance : « Sans eux, écrit Maurras, tout se serait effondré dans la plus grossière anarchie, mais ils présentent cet inconvénient politique de ne rien avoir de français tout en possédant la France et d’être intimement hostiles à tout l’intérêt national qu’ils ont cependant assumé le soin de gérer » (33).

On voit ce qu’a d’outré la conception maurrassienne si l’on songe au seul Ancien Régime : il paraît en effet impossible de soutenir que les protestants n’ont, historiquement, « rien de français ». Mais cette conception s’avère plus pertinente lorsqu’on se penche sur le présent. C’est ainsi qu’on pouvait lire dans Le Nouvel Observateur du 31 octobre 1991 : « Depuis 1789, les protestants ont, en effet, conclu avec la gauche un mariage de raison et d’amour.[…] Hormis aux débuts de l’anticléricale IIIe République qu’ils ont portée sur les fonts baptismaux et qui leur demeure si chère, jamais une telle pléiade de huguenots n’a participé à la gestion du pays ». Et cet hebdomadaire d’énumérer complaisamment les noms de Michel Rocard, Lionel Jospin, Pierre Joxe, Georgina Dufoix, du maire de Strasbourg Catherine Trautmann, des financiers Nicolas et Jérôme Seydoux (très liés à l’actuel président de la République) — tous d’origine protestante et tous serviteurs ou soutiens zélés de la pseudo-tradition républicaine la plus hostile au mouvement national. Cela ne saurait d’ailleurs faire oublier la contribution que plusieurs protestants apportèrent au mouvement national, ni la présence, à droite, d’intellectuels d’origine protestante, même s’il s’agit en l’occurrence d’une droite plus ou moins “modérée” au sens de Bonnard. Il suffira de nommer ici Raoul Girardet et Pierre Chaunu.

Du point de vue contre-révolutionnaire le plus rigoureux, ce sont les quatre États confédérés « qui ont imposé en France une autre tradition, une nouvelle tradition, religieuse et nationale, celle des grands principes de 1789, celle de l’anti-catholicisme, celle de la religion démocratique moderne » (34). Tertium non datur : « Car il y a en France deux traditions, inégalement françaises, inégalement anciennes, inégalement traditions. Elles (co)existent sans se confondre » (35).

Bonnard croyait-il, au moment où il écrivait Les Modérés, que la première tradition formant le cœur de l’identité française avait survécu au point de pouvoir être réveillée et de renverser la République ? Sa position sur ce point présente un certain flottement. Tantôt il répète après Maistre que les peuples ont les gouvernements qu’ils méritent et qu’au lieu d’« opposer une nation pourvue de toutes les bonnes qualités à un régime chargé de toutes les mauvaises, fiction lâche et fausse qui ne mène à rien » — ce qui contredit la distinction maurrassienne entre pays légal et pays réel —, il ne faut « pas craindre de connaître le régime et la nation l’un par l’autre » [dans cette optique, est-on tenté d’ajouter, la conception même des quatre États confédérés relèverait d’une vision “conspirationniste” de l’histoire et de la logique du “bouc émissaire” ; c’est Maurras écrivant en 1912 : « Une démocratie en France ne peut vivre qu’appuyée sur des tempéraments républicains qu’il faut chercher surtout dans la minorité protestante et juive » (36). Tantôt Bonnard dit des républicains convaincus : « Que redoutent-ils donc ? Ils connaissent trop bien les modérés pour pouvoir les craindre. Ce qu’ils paraissent appréhender, c’est qu’il ne subsiste, au-dessous des partis, et malgré tout ce qu’ils ont pu faire pour la détruire, une France des profondeurs, une France des siècles, qui les fera tomber si elle remue ».

En résumé, si l’opposition entre une tradition française fondée pour l’essentiel sur le catholicisme et ce que nous préférons appeler (contrairement à Jean Madiran), une “pseudo”-tradition républicaine (puisqu’elle ne s’enracine dans rien qui soit effectivement sacré ou authentiquement religieux) poursuivant jusqu’à son terme la déchristianisation de la France peut sembler trop rigide et simplificatrice, le fait est qu’elle aide à saisir, avec d’autres facteurs d’explication, la longue série des guerres et déchirements franco-français depuis la Révolution : insurrection vendéenne et phénomène de la chouannerie, Restauration, Commune de Paris, effervescence boulangiste, affaire Dreyfus, Vichy et la Résistance, sans oublier la situation créée par la récente montée en puissance du Front national. Ce sont là des signes de contradiction de la France moderne et contemporaine, qu’il y a tout lieu de regretter, mais qu’il serait encore plus vain de prétendre ignorer.

En dépit du danger qu’il y a toujours à se livrer à des comparaisons entre des situations différentes, car l’analogie n’est pas l’identité, on peut tout de même s’offrir une brève digression en rapport avec l’actualité. Il serait à première vue logique de reprocher aux contre-révolutionnaires d’aujourd’hui de vouloir défendre si désespérément l’identité nationale tout en insistant, comme ils le font, sur la rupture inaugurale de 89. Mais c’est une chose de détester la République tout en respectant ses lois et ses usages pour ne pas attenter à l’unité nationale ; et c’en est une autre d’entretenir par médias interposés un climat de guerre civile larvée, en “criminalisant” par exemple 15 % de l’électorat (et plus potentiellement, puisqu’un sondage apparemment fiable a montré qu’un Français sur trois se reconnaît peu ou prou dans les thèses du Front national), en envisageant même froidement, comme certains, d’interdire le parti représentant cette frange de l’électorat.

Il ne s’agit pas ici de sous-entendre que ce parti est, aujourd’hui en France, l’expression politique d’une contre-révolution redevenue consciente de son héritage. Regroupement très composite de plusieurs tendances de la droite française, le Front national, comme les nationalistes de la fin du XIXe siècle, associe le “culte” de Jeanne d’Arc à “La Marseillaise”, qui vient clore ses grandes réunions, sans se soucier de cette contradiction pourtant patente. Mais il compte en son sein une tendance “nationale-catholique” — organisée autour du quotidien Présent et des comités Chrétienté-Solidarité — qui ne craint pas de reprendre la devise de la Pucelle, “Dieu premier servi”, et qui est expressément contre-révolutionnaire.

Il est donc probable qu’en vertu de la coexistence en France d’une tradition nationale catholique et d’une pseudo-tradition républicaine, le Front national incarne d’ores et déjà et plus ou moins bien, quelque chose de beaucoup plus grand que lui et qui s’enracine, que la plupart de ses membres en aient conscience ou non, dans une mentalité qui n’est pas acquise de cœur aux “grands principes” de 89.

Psychologie sociale des “Modérés” : individualisme et verbalisme

La politique, elle aussi, est plus grande que ce qu’elle paraît être, et qui inspire souvent tant de dégoût. Elle est un drame, souligne Bonnard, qui rappelle fort justement que « ce qui fait qu’elle ne pourra jamais être négligée, c’est que le sort de tout ce qui la dépasse se décide en elle ». Voilà précisément ce que ne veulent pas voir les modérés, qui pensent pouvoir tout arranger par le dialogue, la conciliation, le compromis, bientôt suivis de la compromission et de la reddition pure et simple à l’adversaire, à son vocabulaire pour commencer. Ces modérés, Bonnard les a visiblement beaucoup fréquentés : sinon, il ne les décrirait pas si bien. Son travail relève à la fois de l’observation empirique et de la psychologie sociale : c’est une théorie des passions et des faiblesses humaines appliquée à la vie collective. Une théorie qu’on peut juger obsolète aujourd’hui, dans la mesure où Bonnard, très brillant dans la description des phénomènes sociaux de surface, n’arrive jamais à une véritable étiologie sociale. Mais une théorie qui a en tout cas le mérite, pour ce qui est des modérés, d’adhérer étroitement à la réalité des choses.

Les modérés « sont les restes d’une société », celle où l’on s’accommodait tant bien que mal des principes de 89 parce qu’ils ne s’étaient pas encore transformés en pseudo-religion des Droits de l’Homme envahissant tous les domaines de la vie civile et, surtout, parce que la République, en France, s’appuyant sur la solidité de l’État et l’omniprésence de l’administration, a toujours su préserver — hélas ! est-on tenté de dire — une apparence d’ordre. Ce désordre établi, cette subversion installée qui fait que les trains arrivent à l’heure et que la sécurité des personnes et des biens est assurée, voilà ce qui satisfait pleinement la bourgeoisie, qui n’est qu’un autre nom des modérés : depuis la Révolution, elle n’a cessé de préférer, dit Bonnard dans une de ces formules dont il a le secret, « une anarchie avec des gendarmes » à « une monarchie avec des principes ».

Jouissant encore des résidus d’un certain ordre dont ils ont hérité sans en connaître le prix et sans jamais songer à le défendre vraiment, les modérés sont pour Bonnard la quintessence de la médiocrité française, l’expression la plus basse du type humain que fabrique la modernité en général : “l’individu”. C’est en tant qu’il est d’abord un individu — à savoir un homme « réduit par l’exigence de la vanité à l’indigence du Moi […], prompt à se pousser dans une organisation sociale dont il profite sans la soutenir » — que le modéré s’oppose nettement au réactionnaire, « plus fier de l’ensemble auquel il reste attaché que des facultés dont est parée sa nature ».

Débiteur qui ne se sent jamais d’obligation envers le passé de sa nation et la communauté à laquelle il appartient, le modéré est devenu peu à peu le modèle de toutes les classes et ses défauts ont fini par atteindre les couches populaires, donnant lieu à la misérable figure sociale de “l’assisté”, dont Bonnard, près d’un demi-siècle avant que le mot se répande, avait tracé, devant les chefs miliciens, un portrait plus vrai que nature : « L’individu, c’est le dernier produit d’une société qui devient stérile, c’est l’être humain tombé de la plénitude de l’homme dans l’exiguïté du Moi, c’est le nain arrogant, l’avorton prétentieux qui, toujours content de soi, n’est jamais content des autres, qui, restant toujours isolé sans être capable de vivre seul, à la fois dissident et dépendant, est l’atome d’une foule au lieu d’être l’élément d’un peuple. L’individu vit perpétuellement dans un état de désertion sociale. Il prétend être entretenu par une société qu’il n’entretient pas, il demande sans apporter, il voudrait tout recevoir sans rien donner et, dans une société décomposée, il représente un abaissement et une déchéance qui se retrouvent à travers toutes les classes » (37).

Énoncé dans Les Modérés, soit plus ou moins à l’époque où Drieu opposait « la France du camping » à celle de « l’apéro » (on sait que l’une et l’autre se sont très facilement retrouvées depuis), ce rejet du Français-type de la démocratie façon Front Populaire, tout entier résumé dans la formule “j’ai ma combine”, va se durcir encore chez Bonnard pour atteindre à une véritable répulsion qui, dans un style tout différent, n’est pas moins forte que celle de Céline. L’un et l’autre, sous l’Occupation, éprouveront un dégoût physiologique devant la lâcheté, l’attentisme et l’égoïsme de millions d’“individus” français. C’est Céline vilipendant en 1941 les petits-bourgeois gonflés de “droits” : « Ils veulent rester carnes, débraillés, pagayeux, biberonneux, c’est tout. Ils ont pas un autre programme. Ils veulent revendiquer partout, en tout et sur tout et puis c’est marre. C’est des débris qu’ont des droits » (38). Et c’est Bonnard mettant le doigt sur la plaie dans Je suis partout le 25 août 1940 : « Regardez-le, cet homme que la démagogie bourgeoise […] a multiplié chez nous en tant d’exemplaires, à la fois mou et fanfaron, avachi et prétentieux, ne se contentant pas de se relâcher en tout, mais mettant encore un plumet de fatuité à sa négligence » (39).

L’autre point par où la critique de Bonnard s’exerce contre la psychologie sociale des modérés est le verbalisme, le règne des mots, l’inflation verbale. En cela aussi, Bonnard se rattache à toute une lignée de la culture de droite, et plus précisément du traditionalisme anti-moderne, que soude, par-delà des jugements fort différents sur le christianisme, l’insistance sur le thème de la modernité comme âge de la “discussion perpétuelle” (40). Cette dernière formule est de Donoso Cortés, pourfendeur de la bourgeoisie comme “classe discuteuse” par excellence, et qui s’était bien aperçu que, du point de vue de la philosophie démocratique, « la discussion est la vraie loi fondamentale des sociétés humaines et l’unique creuset où, après fusion, la vérité, dégagée de tout alliage d’erreur, apparaît dans sa pureté » (41). Maurras, de son côté, prononcera un jugement analogue : « La République est le régime de la discussion pour la discussion et de la critique pour la critique. Qui cesse de discuter, qui arrête de critiquer, offense les images de la Liberté. La République, c’est le primat de la discussion et de la plus stérile » (dansL’Action française du 22 novembre 1912).

Mais ce qui fait l’originalité de Bonnard, c’est que sa critique de la rhétorique, dont les modérés lui apparaissent comme les champions, s’intègre à une analyse de vieux défauts spécifiquement nationaux que les Français doivent quitter absolument. Le délicat qu’était Bonnard, admirateur de la vie de société portée dans la France du XVIIIesiècle à une manière de perfection, s’était également convaincu que la France moderne « est le pays où les défauts des salons sont descendus dans les rues ». En somme, seuls les charmes de l’ancienne société ne sont plus là, « ses inconvénients durent encore ».

La fatuité bien française qui consiste à croire la bataille gagnée avant de l’avoir engagée, le goût incorrigible pour les bons mots qui évite de penser vraiment et pour la petite anecdote mesquine, le besoin de paraître en toutes circonstances pour masquer le manque d’originalité vraie, la frivolité devenue de longue date une maladie sociale, sont décortiqués dans Les Modérés mieux que dans tout autre livre sur la psychologie nationale. Bonnard estime que les Français, toutes classes sociales confondues, se caractérisent par un « incroyable éloignement du réel » ; leur « curiosité volage pour toutes les idées », qui fait qu’ils se croient généralement très malins, n’est pour lui « que l’incapacité d’en retenir fortement aucune ».

La démocratie, qui érige le café du commerce en système de commentaire permanent de la vie, où le premier crétin venu peut se flatter d’avoir des opinions sur tout à la mesure même de son ignorance, a donc renforcé un vieux défaut national et fourni des conditions idéales, s’il est permis de s’exprimer ainsi, à l’épanouissement béat du phraseur parasitaire. Mais ce que le génie de Bonnard pour saisir la psychologie des peuples met bien en relief, c’est que cet égotisme extrême ne débouche même pas sur une quelconque originalité intéressante.

On sait que l’Angleterre a la réputation justifiée d’être le pays des bizarres et des sociétés d’excentriques. Or Bonnard, dans un écrit postérieur d’un an aux Modérés, avait bien vu tout ce qui sépare l’individualisme français, vêtu de sa seule médiocrité, de l’originalité authentique dont certains Anglais, natifs d’un vieux pays dont l’identité profonde n’a pas été déchirée par les remous de l’histoire, étaient et sont capables de faire preuve. Une intuition infaillible le guide ici, qui lui fait écrire à propos de l’originalité : « En France, elle est ajoutée à l’individu, on pourrait la lui ôter. En Angleterre, elle lui est inhérente. En France, elle est artificieuse et volontaire, en Angleterre ingénue et involontaire. En France, c’est souvent un plumet dont s’attife l’individu ; la prétendue singularité n’est qu’une bravade de l’homme ordinaire. Elle a des origines sociales et non naturelles, c’est une façon de paraître et non d’exister. Elle a des causes mondaines, et ainsi elle est déterminée d’avance par les tendances et par les modes de cette société où l’individu la manifeste. En Angleterre, au contraire, l’originalité visible de l’individu exprime sa singularité réelle […], celui qui la manifeste ainsi se moque de l’opinion, et ne se soucie pas de l’applaudissement social » (42).

Appliquée à la vie politique, la logomachie démocratique fait l’objet de deux remarques essentielles, d’une actualité étonnante, de la part de Bonnard. L’une est d’ordre général et porte sur la guerre sémantique, l’une des caractéristiques majeures du XXe siècle : « Le premier réalisme, en politique, est de connaître les démons qui sont cachés dans les mots ». L’autre est d’ordre local, et chaque jour qui passe en confirme le bien-fondé : « La France est le pays où l’on a peur des mots, comme dans d’autres on a peur des fantômes : en face de ceux qui servent d’épouvantails, il y a ceux qui servent d’appâts ».

La peur française des mots n’empêche pas de parler, bien au contraire. C’est une fausse peur soigneusement calculée qui vise à ahurir par des mots et à couper la parole, à interdire de parole ceux qui ont été préalablement désignés par certains mots employés comme des armes. Cela ne vaut pas seulement pour des termes comme “extrême droite”, “racisme”, “fascisme”, “nazisme”, devenus indéfiniment applicables et extensibles depuis 1945. À l’époque des Modérés, il était déjà admis qu’un “conservateur” est nécessairement hostile à tout “changement”, qu’un “réactionnaire” ne peut que tourner le dos à toute espèce de “progrès”, qu’un catholique convaincu est un homme prisonnier de “dogmes dépassés”, quand d’autres, les francs-maçons par exemple, ont pour eux la “tolérance” et la “liberté d’esprit”.

Mais il est vrai que ces formes de péjoration n’étaient rien en comparaison de la gigantesque imposture lexicale du soi-disant “racisme” d’aujourd’hui. En effet, si les mots avaient encore un sens dans ce pays subverti jusqu’à la moelle, le mot “racisme” devrait désigner exclusivement une idéologie affirmant le caractère central du facteur racial dans le cadre d’une tentative d’explication de l’histoire, ou bien soutenant la supériorité d’une ou plusieurs races sur les autres, et le droit subséquent des premières à exploiter, voire à exterminer les secondes. Or, tout cela n’a strictement rien à voir avec la tradition doctrinale du mouvement national en France, où les théoriciens du “racisme” n’ont jamais eu le moindre succès. Avec l’antiracisme actuel, on sort en fait de toute rationalité, de toute logique, pour tomber dans le conditionnement de masse. Comme l’a bien vu Jules Monnerot, « l’antiracisme est un racisme contre les racistes », ou, plutôt, contre ceux ainsi qualifiés. « Le groupe détesté est construit par le groupe détestateur qui sélectionne des traits réels et même, en plus, des traits imaginaires, traits qui sont l’objet de rites d’exécration et de malédictions collectives à la mode du XXe siècle réputé civilisé, surtout de malédictions médiatiques. Ce sont techniquement les plus parfaites excitations à la haine qu’on ait connues dans l’histoire de l’humanité »(43).

Rééditer Les Modérés, c’est donc aussi participer à l’entreprise de démontage du terrorisme intellectuel savamment mis en œuvre par les défenseurs des idées “généreuses”.

Enfin, il est évident que l’ouvrage de Bonnard est plus actuel que jamais si on le replace dans l’histoire de la droite française au XXe siècle. L’opposition modéré/réactionnaire sur laquelle Bonnard revient à plusieurs reprises, recoupe deux autres oppositions qui n’ont cessé de marquer le mouvement national en France : celle des “nationaux” et des “nationalistes”, celle des notables et des militants. Les réflexions de Bonnard sur les émeutes du 6 février 1934, qu’on lira au détour de plusieurs pages des Modérés, permettent déjà de comprendre ce qu’il pensait de l’agitation brouillonne des “nationaux”. Dans son Journal, il est beaucoup plus clair, c’est-à-dire beaucoup plus méprisant. C’est ainsi qu’il note à propos du colonel de La Rocque, le chef des Croix-de-Feu : « La Rocque, me dit-on, a quelque chose de fonctionnaire en lui. Non. De factionnaire. Un autre me dit : il organise des défilés. Non. Des défilades » (44).

“Le Destin n’attend pas”

Le 7 décembre 1940, Abel Bonnard écrit dans l’un des articles qu’il réunira l’année suivante sous le titre Pensées dans l’action : « Le Destin n’attend pas : dans la vie des nations comme dans celle des individus, il n’y a que de rares moments de choix, dont il faut reconnaître l’insigne importance, si l’on veut profiter pleinement des chances qu’ils nous offrent. L’Occasion est une déesse qui ne s’assied pas » (45).

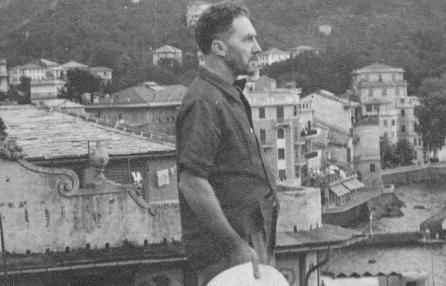

Le futur successeur du latiniste Jérôme Carcopino au ministère de l’Éducation nationale du régime de Vichy, poste qu’il occupera du 18 avril 1942 au 20 août 1944, croit donc que la cuisante défaite de juin 1940 est une occasion à saisir pour répudier la démocratie et tenter de rebâtir de fond en comble un ordre français. Une espérance de renaissance a brillé un instant, à laquelle Bonnard s’est rallié, comme tant d’autres, par détestation de la démocratie et de la République, certes, mais aussi par patriotisme. On ne saurait expliquer ses choix, en revanche, par une germanophilie prononcée. Classique par son style et par sa culture, Bonnard a toujours été beaucoup plus tourné vers la Grèce, Rome ou l’Asie que vers l’Europe du Nord, et il est plus que probable que le “romantisme d’acier” cher au Dr Goebbels n’évoquait rien pour lui. Mais Bonnard a succombé aux sirènes “européanistes” de la propagande allemande et pensé — à tort — que l’Allemagne hitlérienne avait sincèrement renoncé à son pangermanisme devant les nécessités urgentes de la “croisade” antibolchevique à l’Est.

L’explication proposée par un esprit pourtant aussi fin qu’Ernst Jünger, qui mentionne Bonnard à quatre reprises dans son Second Journal parisien (1943-1945), n’est pas convaincante. En date du 31 août 1943, Jünger note : « Pourquoi Bonnard, cet homme sagace, à l’esprit clair, se perd-il dans de tels domaines de la politique ? En le voyant, j’ai pensé à ce mot de Casanova, disant qu’aux fonctions d’un ministre devait être associé un charme qu’il ne parvenait pas à comprendre, mais qui opérait sur tous ceux qu’il avait vus dans un tel poste. Au vingtième siècle, il ne reste plus que le travail et les coups de pied de l’âne que vous donne la populace, et auxquels il faut se résigner tôt ou tard » (46).

Bonnard en conseiller du Prince et homme d’influence, délaissant les croisières d’autrefois, les conversations mondaines et les lectures érudites, pour satisfaire un appétit de pouvoir et savourer encore mieux le goût bien agréable de la revanche sur un régime honni ? Peut-être, ce sont des choses qui arrivent assez souvent aux intellectuels, y compris aux plus raffinés d’entre eux. Mais il nous paraît plus juste de penser que Bonnard, qui n’avait personnellement rien à gagner à s’engager dans cette aventure et qui était très au-dessus de la foire aux vanités, s’est engagé avec l’énergie du désespoir : l’occasion offerte par l’histoire a dû lui sembler la dernière chancepour la France et l’Europe. On lit dans l’un des nombreux manuscrits qu’il a laissé inachevés, et qui date du lendemain de la Première Guerre mondiale : « … il y a une gaieté suprême dans les actions presque désespérées : ce sont en un sens les plus libres » (47).

Cette explication nous paraît confirmée par le silence quasi total de l’exil madrilène de Bonnard. Celui-ci aura vécu vingt-trois ans en Espagne (de 1945 à 1968) sans écrire aucun livre, tout en songeant vaguement à reprendre quelques projets d’ouvrages. La misère d’abord, la pauvreté ensuite connues par lui à Madrid, ne peuvent rendre compte, à elles seules, de cette stérilité. Bonnard s’est volontairement muré dans le silence, choisissant de disparaître avec son monde. Ses tout derniers écrits portent la marque d’un pessimisme et d’une misanthropie accusés. Dans le texte présenté comme son testament politique, et qui date de 1962, Bonnard écrit : « Maintenant, tout est dit. […] Désormais, les événements se font tout seuls. On est entré dans une période géologique de l’histoire, qui peut se caractériser aussi bien par des effondrements subits que par des engourdissements infinis, tandis qu’une réalité inconnue monte lentement vers la surface des choses. Tout se tient, aucun problème ne peut plus être encadré, étudié, résolu isolément par l’esprit. […] Le désastre de l’homme s’étend à toute la terre. […] Où nous avions voulu fonder un ordre, un abîme s’ouvre. Il arrive ce que nous nous étions expressément proposé d’éviter : le monde tombe dans le chaos » (48).

Le 19 février 1962, Bonnard dit, à la manière de Cioran mais avec plus de concision encore : « La Mort nous cache le regret de quitter le monde dans le bonheur de quitter les hommes » (49). Le 6 février 1966, il répond à des amis qui le sollicitent pour la réédition de l’un de ses livres : « Penser à mes papiers me fatigue, outre l’indifférence plénière, foncière, complète, absolue, océanique que j’ai pour ce que les gens peuvent penser de moi » (50).

Que les sombres pronostics de Bonnard sur l’avenir, non pas seulement de la France et de l’Europe, mais de tout ce qui mérite le nom de culture, se vérifient demain ou non, il restera ce joyau que sont Les Modérés, livre écrit dans une langue éblouissante du début à la fin, rempli de phrases à la cadence parfaite et frappées comme des maximes. Céline, qui avait un goût très sûr en matière littéraire et qui savait apprécier les écrivains les plus éloignés de lui par le style, a dit de Bonnard : « Un des plus beaux esprits français […] tout à fait dans la tradition de Rivarol ». Quant au désespoir, nous pourrons toujours lui opposer cette maxime de Bonnard, qui égale celles de la sagesse universelle : « Si l’histoire est une tragédie pour l’âme, elle reste une comédie pour l’esprit ».

► Philippe Baillet, Présentation des Modérés, éd. des Grands Classiques (ELP), 1993.

Notes :

- (1) Cité dans Olivier Mathieu, Abel Bonnard ou l’aventure inachevée, Avalon, Paris, 1987, p. 199.

- (2) Toutes les citations sans appel de note sont extraites des Modérés.

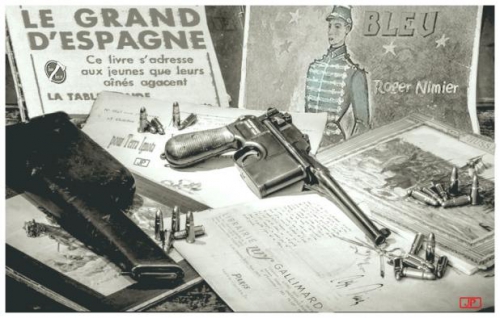

- (3) Henry Muller, Trois pas en arrière, La Table Ronde, Paris, 1952 ; cité dans Olivier Mathieu, op. cit., p. 224.

- (4) Abel Bonnard, « Discours aux chefs miliciens », in : Id., Inédits politiques, Avalon, Paris, 1988, p. 192.

- (5) Cité dans Olivier Mathieu, op. cit., p. 11.

- (6) Ibid., p. 289.

- (7) Ibid., pp. 145-146.

- (8) Ibid., p. 159.

- (9) Ibid., p. 153.

- (10) Concernant ces dernières, nous voulons bien sûr parler de la biographie d’Olivier Mathieu, Abel Bonnard ou l’aventure inachevée et de sa très longue préface aux Inédits politiques de Bonnard (titre qui ne se justifie pas, d’ailleurs, puisque seule une partie des textes réunis dans ce recueil est effectivement composée d’inédits, mais que nous préférons au grotesque et provocateur Berlin, Hitler et moi choisi par Olivier Mathieu). Après avoir écrit une préface très littéraire et très personnelle pour la deuxième édition desModérés (Livre-Club du Labyrinthe, Paris, 1986), Olivier Mathieu s’est enfoncé dans un délire “post-révisionniste” (sic) dont il n’est apparemment pas sorti. Le délire se constate, il s’explique éventuellement, mais il ne se discute pas : nous ne discuterons donc pas les jugements de Mathieu, qui a eu le mérite de rassembler une documentation considérable sur Bonnard et de travailler activement — sinon intelligemment — à sa redécouverte.

- (11) Dont témoigne, outre les rééditions de L’Argent, L’Amitié et de Saint François d’Assise (cf. bibliographie), le récent recueil d’articles et d’aphorismes de Bonnard paru sous le titre Ce monde et moi, Dismas, Haut-le-Wastia, 1991. Cet important recueil permet notamment de mieux comprendre la position de Bonnard à l’égard du christianisme. L’auteur des Modérés ne fut pas un païen panthéiste, comme voudrait le faire croire Olivier Mathieu. Mais le souci de la vérité interdit pareillement d’en faire un catholique. L’aphorisme § 351 de Ce monde et moi livre sans doute la solution : « La grâce peut nous manquer : la foi ne dépend pas de nous, mais il dépend de nous de reconnaître sa nécessité et sa valeur. Il n’est pas besoin d’être un homme croyant pour être un homme religieux » (p. 182).

- (12) Cité dans Olivier Mathieu, op. cit., p. 154.

- (13) Abel Bonnard, En Chine, Fayard, Paris, 1924, pp. 278-279.

- (14) Ibid., p. 340.

- (15) Ibid., pp. 344-345.

- (16) Bonnard et Evola ont en commun la radicalité de leur révolte “antimoderne”, une sensibilité innée pour saisir correctement en quoi consiste la mentalité “traditionnelle”, voire archaïque, le rejet de tout ethnocentrisme culturel, une profonde admiration pour la civilisation extrême-orientale, en particulier pour le bouddhisme. Enfin, tous deux se sont beaucoup intéressés au problème des races, aux modernes théoriciens “racistes”, défendant l’un et l’autre une conception “dynamique” de la race, très différente du biologisme scientiste qui prévalait dans l’entre-deux-guerres. Certaines phrases de Bonnard contenues dans le manuscritLa Question juive (1937) — consacré en fait au problème des races beaucoup plus qu’à la question juive — pourraient avoir été signées par Evola. Quelques exemples : « Il est trop facile de faire observer que la race n’est pas susceptible d’une définition rigoureuse. Beaucoup de choses existent dans le monde humain que l’on ne peut pas définir scientifiquement, la folie par exemple. […] Le mot de racisme peut aussi bien marquer un but qu’un état, une réalité à atteindre qu’une réalité donnée. On peut précisément être raciste pour sortir du mélange où l’on est, tant qu’il en est temps encore. […] Ce qui constitue une race, ce ne sont pas des mensurations. Il faut la saisir dans la vie, dans une façon de sentir le monde et l’existence, de raconter des histoires et des légendes » (citations extraites de : Abel Bonnard, Inédits politiques, op. Cit., pp. 112 et 127).

- (17) Cité dans Olivier Mathieu, op. cit., p. 55.

- (18) Julius Evola, Le Chemin du Cinabre, Archè-Arktos, Milan-Carmagnole, 1983, p. 32.

- (19) Abel Bonnard, En Chine, op. cit., p. 35.

- (20) Ibid., p. 22.

- (21) Abel Bonnard, « Saint François d’Assise, le saint de l’enfance et du bonheur », in : Le Spectacle du Monde, déc. 1963, p. 122.

- (22) Cité par René Guénon dans une lettre du 20 novembre 1925 adressée à Guido De Giorgio. Cf. Guido De Giorgio, L’instant et l’Éternité et autres textes sur la Tradition, Archè, Milan, 1987, p. 257.

- (23) Abel Bonnard, Le Comte de Gobineau, Dynamo, Liège, 1968, pp. 8-9.

- (24) Cité dans Olivier Mathieu, op. cit., pp. 11-12.

- (25) Abel Bonnard, « L’Empire dont l’empereur est poète », in : Le Spectacle du Monde, mars 1963, p. 64.

- (26) Paul Sérant, Le Romantisme fasciste, Fasquelle, Paris, 1959, p. 115.

- (27) Abel Bonnard, Saint François d’Assise, Flammarion, Paris, 1929, p. 214.

- (28) Joseph de Maistre, Considérations sur la France, Garnier, Paris, 1980, p. 34.

- (29) Augustin Cochin, La Révolution et la libre-pensée, Copernic, Paris, 1979, p. 9.

- (30) Cité dans Olivier Mathieu, op. cit., p. 282.

- (31) Paul Sérant, op. cit., p. 20.

- (32) Charles Maurras, La Démocratie religieuse, Nouvelles Éditions Latines, Paris, 1978, p. 90.

- (33) Ibid.

- (34) Jean Madiran, Les quatre ou cinq États confédérés, Supplément-Voltigeur d’Itinéraires, numéro spécial hors série, oct.-nov. 1979, p. 5.

- (35) Ibid., p. 10.

- (36) Charles Maurras, op. cit., p. 200, note 1.

- (37) Abel Bonnard, Inédits politiques, op. cit., pp. 183-184.

- (38) Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Les Beaux draps, Nouvelles Éditions Françaises, Paris, 1941, p. 49.

- (39) Abel Bonnard, « Nos défauts et nous », in Id., Inédits politiques, op. cit., p. 209.

- (40) Pierre-André Taguieff, « Nietzsche dans la rhétorique réactionnaire », in A. Boyer, A. Comte-Sponville, V. Descombes et al., Pourquoi nous ne sommes pas nietzschéens, Grasset, Paris, 1991, p. 219. On peut renvoyer à ce long article pour l’étude de la tradition droitière de la critique de la modernité comme époque de l’inflation verbale. Ici, l’indéniable érudition et les capacités d’analyse du professeur Taguieff ne sortent pas du cadre scientifique pour justifier la répression policière des idées.

- (41) Juan Donoso Cortés, « Lettre au cardinal Fornari sur les erreurs contemporaines » (19 juin 1852), in : Les Deux Étendards, I, 1, sept.-oct. 1988, p. 16. Ce grand texte du penseur espagnol a fait l’objet d’une nouvelle traduction, accompagnée d’une longue présentation d’André Coyné cf. Lettre au cardinal Fornari et textes annexes, L’Âge d’Homme, Lausanne-Paris, 1989.

- (42) Abel Bonnard, Inédits politiques, op. cit., pp. 115-116.

- (43) Jules Monnerot, « Racisme et identité nationale », dans la brochure collective Le soi-disant anti-racisme, Une technique d’assassinat juridique et moral, numéro spécial d’Itinéraires, 3e éd., 1990, p. 40.

- (44) Cité dans Olivier Mathieu, op. cit., p. 259.

- (45) Abel Bonnard, « Franchise ou “habileté” ? », in : Inédits politiques, p. 246.

- (46) Ernst Jünger, Journaux de guerre, Julliard, 1990, p. 556.

- (47) Cité dans Olivier Mathieu, op. cit., p. 162.

- (48) Ibid., pp. 359-360.

- (49) Ibid., p. 362.

- (50) Ibid., p . 368.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

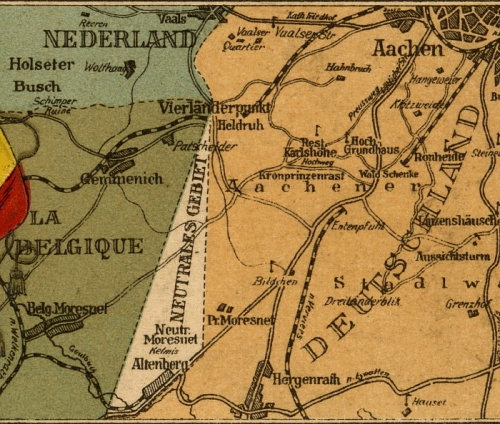

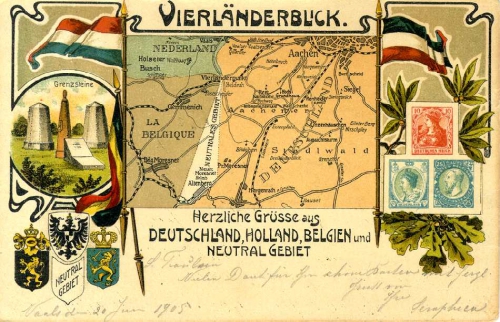

Neutral-Moresnet ne connaissait ni tribunal ni élections ni service militaire : pour autant, l’anarchie n’y régnait pas. L’ordre y était maintenu par des policiers belges et prussiens qui avaient l’autorisation, si cela s’avérait nécessaire, de franchir la frontière pour cueillir des délinquants. La Belgique et la Prusse se partageaient la masse fiscale. Il n’y avait aucune taxe sur les importations et les exportations, ce qui avantageait la contrebande. Le village disposait de trois gares : Hergenrath pour les grandes lignes qui reliaient Liège à l’Allemagne ; une gare cul-de-sac qui avait, elle, un statut de neutralité et qui s’étendait sur quelques centaines de mètres au-delà de la zone neutre ; enfin, une troisième gare en direction de Moresnet sur la ligne Tongres/Aix-la-Chapelle. L’entreprise qui donnait du travail était pour l’essentiel la société des mines. Elle ne négligeait pas le bien-être des travailleurs qui bénéficiaient de temps libres, largement encouragés. Des chœurs et des orchestres de mineurs furent créés ainsi que pas moins de sept associations de « Schützen », une société de pêcheurs et plusieurs sociétés de carnaval. La densité des bistrots y était inégalée. Quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, le petit territoire de Neutral-Moresnet est immédiatement occupé par les armées du Kaiser mais reste, du moins sur le plan formel, administré conjointement par les Belges et les Prussiens. Le Traité de Versailles donne le territoire à la Belgique et s’appelle désormais « Kelmis » (en allemand et en néerlandais) et « La Calamine » (en français). Il s’était appelé « Kalmis » jusqu’en 1972.

Neutral-Moresnet ne connaissait ni tribunal ni élections ni service militaire : pour autant, l’anarchie n’y régnait pas. L’ordre y était maintenu par des policiers belges et prussiens qui avaient l’autorisation, si cela s’avérait nécessaire, de franchir la frontière pour cueillir des délinquants. La Belgique et la Prusse se partageaient la masse fiscale. Il n’y avait aucune taxe sur les importations et les exportations, ce qui avantageait la contrebande. Le village disposait de trois gares : Hergenrath pour les grandes lignes qui reliaient Liège à l’Allemagne ; une gare cul-de-sac qui avait, elle, un statut de neutralité et qui s’étendait sur quelques centaines de mètres au-delà de la zone neutre ; enfin, une troisième gare en direction de Moresnet sur la ligne Tongres/Aix-la-Chapelle. L’entreprise qui donnait du travail était pour l’essentiel la société des mines. Elle ne négligeait pas le bien-être des travailleurs qui bénéficiaient de temps libres, largement encouragés. Des chœurs et des orchestres de mineurs furent créés ainsi que pas moins de sept associations de « Schützen », une société de pêcheurs et plusieurs sociétés de carnaval. La densité des bistrots y était inégalée. Quand éclate la première guerre mondiale, le petit territoire de Neutral-Moresnet est immédiatement occupé par les armées du Kaiser mais reste, du moins sur le plan formel, administré conjointement par les Belges et les Prussiens. Le Traité de Versailles donne le territoire à la Belgique et s’appelle désormais « Kelmis » (en allemand et en néerlandais) et « La Calamine » (en français). Il s’était appelé « Kalmis » jusqu’en 1972.

Ainsi arrive dans cet eldorado de la calamine une certaine Maria Rixen, servante allemande engrossé par son patron. Elle y cherche le bonheur, refuse l’exclusion qu’un siècle encore très pudibond inflige aux filles-mères en Prusse protestante. Elle accouche d’un garçon, confié, comme le veut l’époque, à une famille d’accueil : le petit Joseph Rixen est débaptisé dans la pratique car la maisonnée compte déjà un petit Joseph. On l’appelle Emile Pauly. Un gamin à double identité. En 1914, il devient allemand. En 1919, belge. En 1923, l’armée belge l’appelle comme conscrit. Il doit aller occuper la Ruhr. En 1940, il redevient allemand et est incorporé dans la Wehrmacht, encaserné dans la même caserne qu’il occupait à Krefeld sous l’uniforme belge. Il se sent belge, baptise son septième fils « Léopold », en l’honneur du roi. Il déserte mais est arrêté par des résistants qui le traitent en ennemi. Une belle région qui a été tiraillée entre trois pays. Aujourd’hui existe une structure européenne nommée l’Euroregio qui regroupe les provinces belges de Limbourg et de Liège, l’arrondissement d’Aix-la-Chapelle/Düren et la province néerlandaise du Limbourg (avec Maastricht), ce qui englobe tout le territoire de la « communauté germanophone de Belgique (Eupen, Saint-Vith et Malmédy). Les destins personnels au cours du 20ème siècle sont souvent complexes et peuvent servir de matière à des romans poignants. On aurait espéré plus de biographies personnelles. En effet, que n’ai-je pas entendu de récits trop fragmentaires de tel résistant (qui se germanisera après la guerre en épousant une belle Rhénane), de tel « malgré-lui » expédié en Russie, en France ou en Norvège, de tel Aixois d’origine wallonne mais de nationalité allemande, du prisonnier allemand devenu, contraint et forcé, mineur en pays liégeois (et qui a voulu y rester), de cet adjudant de carrière wallon qui a décidé de finir ses jours en Rhénanie car la vie y est plus conviviale, d’un Verviétois de mère allemande et de père wallon engagé sur le front russe, de tel Volksdeutsche habitant Liège ou natif de la Cité ardente qui ne saura pour qui opter, etc. Nos deux auteurs ont un message : revenir aux temps joyeux de Neutral-Moresnet.

Ainsi arrive dans cet eldorado de la calamine une certaine Maria Rixen, servante allemande engrossé par son patron. Elle y cherche le bonheur, refuse l’exclusion qu’un siècle encore très pudibond inflige aux filles-mères en Prusse protestante. Elle accouche d’un garçon, confié, comme le veut l’époque, à une famille d’accueil : le petit Joseph Rixen est débaptisé dans la pratique car la maisonnée compte déjà un petit Joseph. On l’appelle Emile Pauly. Un gamin à double identité. En 1914, il devient allemand. En 1919, belge. En 1923, l’armée belge l’appelle comme conscrit. Il doit aller occuper la Ruhr. En 1940, il redevient allemand et est incorporé dans la Wehrmacht, encaserné dans la même caserne qu’il occupait à Krefeld sous l’uniforme belge. Il se sent belge, baptise son septième fils « Léopold », en l’honneur du roi. Il déserte mais est arrêté par des résistants qui le traitent en ennemi. Une belle région qui a été tiraillée entre trois pays. Aujourd’hui existe une structure européenne nommée l’Euroregio qui regroupe les provinces belges de Limbourg et de Liège, l’arrondissement d’Aix-la-Chapelle/Düren et la province néerlandaise du Limbourg (avec Maastricht), ce qui englobe tout le territoire de la « communauté germanophone de Belgique (Eupen, Saint-Vith et Malmédy). Les destins personnels au cours du 20ème siècle sont souvent complexes et peuvent servir de matière à des romans poignants. On aurait espéré plus de biographies personnelles. En effet, que n’ai-je pas entendu de récits trop fragmentaires de tel résistant (qui se germanisera après la guerre en épousant une belle Rhénane), de tel « malgré-lui » expédié en Russie, en France ou en Norvège, de tel Aixois d’origine wallonne mais de nationalité allemande, du prisonnier allemand devenu, contraint et forcé, mineur en pays liégeois (et qui a voulu y rester), de cet adjudant de carrière wallon qui a décidé de finir ses jours en Rhénanie car la vie y est plus conviviale, d’un Verviétois de mère allemande et de père wallon engagé sur le front russe, de tel Volksdeutsche habitant Liège ou natif de la Cité ardente qui ne saura pour qui opter, etc. Nos deux auteurs ont un message : revenir aux temps joyeux de Neutral-Moresnet.

Avant Bloy et son âme d’empereur, Flaubert comprend Napoléon (ce génie incompris) et il envoie promener Lamartine, ce « couillon qui n’a jamais pissé que de l’eau claire » :

Avant Bloy et son âme d’empereur, Flaubert comprend Napoléon (ce génie incompris) et il envoie promener Lamartine, ce « couillon qui n’a jamais pissé que de l’eau claire » : « Je crois que plus tard on reconnaîtra que l'amour de l'humanité est quelque chose d'aussi piètre que l'amour de Dieu. On aimera le Juste en soi, pour soi, le Beau pour le beau. Le comble de la civilisation sera de n'avoir besoin d'aucun bon sentiment, ce qui s'appelle. »

« Je crois que plus tard on reconnaîtra que l'amour de l'humanité est quelque chose d'aussi piètre que l'amour de Dieu. On aimera le Juste en soi, pour soi, le Beau pour le beau. Le comble de la civilisation sera de n'avoir besoin d'aucun bon sentiment, ce qui s'appelle. » « Le père et la mère de Julien habitaient un château, au milieu des bois, sur la pente d'une colline. »

« Le père et la mère de Julien habitaient un château, au milieu des bois, sur la pente d'une colline. »

Sélectionnées et ordonnées par Michel Granger, professeur de littérature américaine à l’université Lyon 2 et spécialiste de Thoreau, les Pensées sauvages sont extraites de divers ouvrages du naturaliste, dont le fameux Walden ou la vie dans les bois. Au final, nous tenons entre les mains une remarquable anthologie dans laquelle chacun peut puiser, au gré de ses humeurs, de ses inspirations ou de ses centres d’intérêt, une réflexion aussi dense que stimulante sur notre rapport à la modernité. « Puissent ces idées “excitantes” qui vont à l’encontre de la doxa néolibérale et de l’optimisme de la techno-science être prises en compte pour nourrir la réflexion contemporaine », exhorte le professeur Granger en des termes qui font directement écho à la pensée de Jacques Ellul, de Bernard Charbonneau ou d’Ivan Illich.

Sélectionnées et ordonnées par Michel Granger, professeur de littérature américaine à l’université Lyon 2 et spécialiste de Thoreau, les Pensées sauvages sont extraites de divers ouvrages du naturaliste, dont le fameux Walden ou la vie dans les bois. Au final, nous tenons entre les mains une remarquable anthologie dans laquelle chacun peut puiser, au gré de ses humeurs, de ses inspirations ou de ses centres d’intérêt, une réflexion aussi dense que stimulante sur notre rapport à la modernité. « Puissent ces idées “excitantes” qui vont à l’encontre de la doxa néolibérale et de l’optimisme de la techno-science être prises en compte pour nourrir la réflexion contemporaine », exhorte le professeur Granger en des termes qui font directement écho à la pensée de Jacques Ellul, de Bernard Charbonneau ou d’Ivan Illich.

The sexual marketplace

The sexual marketplace Islamization and traditional resurgence

Islamization and traditional resurgence Reading Houellebecq’s past comments and hearing Submission’s synopsis it would be forgivable to assume that he is a rabid Islamophobe whose thinking lacks all subtlety—an ignorant rabble-rouser. But nothing could be further from the truth. Here’s Adam Gopnik of the

Reading Houellebecq’s past comments and hearing Submission’s synopsis it would be forgivable to assume that he is a rabid Islamophobe whose thinking lacks all subtlety—an ignorant rabble-rouser. But nothing could be further from the truth. Here’s Adam Gopnik of the  Islamophobic

Islamophobic

Cadou était un coup d’essai, un pur fruit du hasard. C’est grâce au peintre Jean Jégoudez qu’on a pu accéder à des archives et constituer ce premier cahier. Cadou est un poète marginal qu’on ne lit pas à Paris : c’est l’une des raisons pour lesquelles mon père s’y est intéressé. Mais c’est Bernanos qui donnera le coup d’envoi effectif aux Cahiers. Mon père avait une forte passion pour Bernanos. Il l’avait découvert adolescent. Et par ma mère, nous avons des liens forts avec Bernanos car mon arrière-grand-père, Robert Vallery-Radot, qui fut l’un de ses intimes, est à l’origine de la publication de Sous le soleil de Satan chez Plon. Le livre lui est d’ailleurs dédié. C’est ainsi que mon père aura accès aux archives de l’écrivain et se liera d’amitié avec l’un de ses fils : Michel Bernanos. Ce cahier, plus volumineux que le précédent, constitue un titre emblématique de ce que va devenir L’Herne.

Cadou était un coup d’essai, un pur fruit du hasard. C’est grâce au peintre Jean Jégoudez qu’on a pu accéder à des archives et constituer ce premier cahier. Cadou est un poète marginal qu’on ne lit pas à Paris : c’est l’une des raisons pour lesquelles mon père s’y est intéressé. Mais c’est Bernanos qui donnera le coup d’envoi effectif aux Cahiers. Mon père avait une forte passion pour Bernanos. Il l’avait découvert adolescent. Et par ma mère, nous avons des liens forts avec Bernanos car mon arrière-grand-père, Robert Vallery-Radot, qui fut l’un de ses intimes, est à l’origine de la publication de Sous le soleil de Satan chez Plon. Le livre lui est d’ailleurs dédié. C’est ainsi que mon père aura accès aux archives de l’écrivain et se liera d’amitié avec l’un de ses fils : Michel Bernanos. Ce cahier, plus volumineux que le précédent, constitue un titre emblématique de ce que va devenir L’Herne.

PHILITT :

PHILITT : PHILITT :

PHILITT :

[…] Mais où est, je vous prie, la garantie du progrès pour le lendemain ? Car les disciples des philosophes de la vapeur et des allumettes chimiques l’entendent ainsi : le progrès ne leur apparaît que sous la forme d’une série indéfinie. Où est cette garantie ? Elle n’existe, dis-je, que dans votre crédulité et votre fatuité.

[…] Mais où est, je vous prie, la garantie du progrès pour le lendemain ? Car les disciples des philosophes de la vapeur et des allumettes chimiques l’entendent ainsi : le progrès ne leur apparaît que sous la forme d’une série indéfinie. Où est cette garantie ? Elle n’existe, dis-je, que dans votre crédulité et votre fatuité.