Nota : ce texte est long et dûment référencé. Il apparaîtra pessimiste à certains.

On est en 1957. Sputnik fait rêver les plus conditionnés, mais Aldous Huxley rappelle :

« En 1931, alors que j'écrivais Le Meilleur des Mondes, j'étais convaincu que le temps ne pressait pas encore. La société intégralement organisée, le système scientifique des castes, l'abolition du libre arbitre par conditionnement méthodique, la servitude rendue tolérable par des doses régulières de bonheur chimiquement provoqué, les dogmes orthodoxes enfoncés dans les cervelles pendant le -sommeil au moyen des cours de nuit, tout cela approchait; se réaliserait bien sûr, mais ni de mon vivant, ni même du vivant de mes petits-enfants. »

Il fait un constat après la guerre, comme Bertrand de Jouvenel :

« Vingt-sept ans plus tard, dans ce troisième quart du vingtième siècle après J-C. et bien longtemps avant la fin du premier siècle après F., je suis beaucoup moins optimiste que je l'étais en écrivant Le Meilleur des Mondes. Les prophéties faites en 1931 se réalisent bien plus tôt que je le pensais. L'intervalle béni entre trop de désordre et trop d'ordre n'a pas commencé et rien n'indique qu'il le fera jamais. En Occident, il est vrai, hommes et femmes jouissent encore dans une appréciable mesure de la liberté individuelle, mais même dans les pays qui ont une longue tradition de gouvernement démocratique cette liberté, voire le désir de la posséder, paraissent en déclin. Dans le reste du monde, elle a déjà disparu, ou elle est sur le point de le faire. Le cauchemar de l'organisation intégrale que j'avais situé dans le septième siècle après F. a surgi de lointains dont l'éloignement rassurait et nous guette maintenant au premier tournant. »

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. »

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. »

Le futur c’est la carotte plutôt que le bâton (cf. mes textes sur Tocqueville, Nietzsche ou le film Network) :

« A la lumière de ce que nous avons récemment appris sur le comportement animal en général et sur le comportement humain en particulier, il est devenu évident que le contrôle par répression des attitudes non conformes est moins efficace, au bout du compte, que le contrôle par renforcement des attitudes satisfaisantes au moyen de récompenses et que, dans l'ensemble, la terreur en tant que procédé de gouvernement rend moins bien que la manipulation non violente du milieu, des pensées et des sentiments de l'individu. »

La manipulation est donc à l’ordre du jour :

« Pendant ce temps, des forces impersonnelles sur lesquelles nous n'avons presque aucun contrôle semblent nous pousser tous dans la direction du cauchemar de mon anticipation et cette impulsion déshumanisée est sciemment accélérée par les représentants d'organisations commerciales et politiques qui ont mis au point nombre de nouvelles techniques pour manipuler, dans l'intérêt de quelque minorité, les pensées et les sentiments des masses. »

La clé du système est son renforcement par la démographie explosive :

« De plus, l'accroissement annuel lui-même s'accroît : régulièrement, selon la règle des intérêts composés et irrégulièrement aussi, à chaque application, par une société technologiquement retardataire, des principes de la Santé publique. A l'heure présente, cet excédent atteint 43 millions environ pour l'ensemble du globe, ce qui signifie que tous les quatre ans l'humanité ajoute à ses effectifs l'équivalent de la population actuelle des Etats-Unis - tous les huit ans et demi l'équivalent de la population actuelle des Indes. »

Huxley remet à sa place les blablas sur la pseudo-conquête spatiale :

« Une nouvelle ère est censée avoir commencé le 4 octobre 1957, mais en réalité, dans l'état présent du monde, tout notre exubérant bavardage post-spoutnik est hors de propos, voire même absurde. En ce qui concerne les masses de l'humanité, l'âge qui vient ne sera pas celui de l'Espace cosmique, mais celui de la surpopulation. »

Conséquence ? Les « trous à merde » de Donald :

« Les faits contrôlables semblent indiquer assez nettement que dans la plupart des pays sous-développés, le sort de l'individu s'est détérioré de façon appréciable au cours du dernier demi-siècle. Les habitants sont plus mal nourris; il existe moins de biens de consommation disponibles par tête et pratiquement tous les efforts faits pour améliorer la situation ont été annulés par l'impitoyable pression d'un accroissement continu de la population. »

Le « plus froid des monstres froids » (Nietzsche) va se développer. Une remarque digne de Jouvenel :

« Ainsi, des pouvoirs de plus en plus grands sont concentrés entre les mains de l'exécutif et de ses bureaucrates. Or, la nature du pouvoir est telle que même ceux qui ne l'ont pas recherché mais à qui il a été imposé, ont tendance à y prendre goût… »

Le Deep State (le « minotaure » de Jouvenel) est condamné à croître avec le totalitarisme dans les pays en voie de surpeuplement :

« Insécurité et agitation mènent à un contrôle accru exercé par les gouvernements centraux et à une extension de leurs pouvoirs. En l'absence d'une tradition constitutionnelle, ces pouvoirs accrus seront probablement exercés de manière dictatoriale. »

La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) :

La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) :

« Pour le moment, la surpopulation ne constitue pas pour la liberté individuelle des Américains un danger direct, mais déjà la menace d'une menace. »

Eugéniste, proche de Carrel ici, Huxley annonce un déclin qualitatif de notre population et de notre intelligence, fait aujourd’hui reconnu :

« Malgré les nouvelles drogues-miracle et des traitements plus efficaces (on peut même dire en un certain sens, grâce à eux), la santé physique de la masse ne s'améliorera pas, au contraire, et un déclin de l'intelligence moyenne pourrait bien accompagner cette détérioration. »

Huxley critique froidement les progrès de la médecine (ou leur mauvaise gestion) :

« La mort rapide due à la malaria a été supprimée, mais une existence rendue misérable par la sous-alimentation et le surpeuplement est main- tenant la règle et une mort lente, par inanition, guette un nombre de plus en plus grand d'habitants. »

Huxley ici reprend Bernays sur la montée des élites :

« Nous voyons donc que la technique moderne a conduit à la concentration du pouvoir économique et politique ainsi qu'au développement d'une société contrôlée (avec férocité dans les Etats totalitaires, courtoisie et discrétion dans les démocraties) par les Grosses Affaires et les Gros Gouvernements. »

Notre auteur cite Fromm :

« …Notre société tend à faire de lui un automate qui paie son échec sur le plan humain par des maladies mentales toujours plus fréquentes et un désespoir qui se dissimule sous une frénésie de travail et de prétendu plaisir. »

Puis Huxley évalue la nullité des hommes modernes et par là se rapproche de René Guénon (voyez l’anonymat dans le règne de la quantité) :

« Ces millions d'anormalement normaux vivent sans histoires dans une société dont ils ne s'accommoderaient pas s'ils étaient pleinement humains et s'accrochent encore à « l'illusion de l'individualité », mais en fait, ils ont été dans une large mesure dépersonnalisés. Leur conformité évolue vers l'uniformité. »

Le futur est à la termitière :

« La civilisation este entre autres choses, le processus par lequel les bandes primitives sont transformées en un équivalent, grossier et mécanique, des communautés organiques d'insectes sociaux. A l'heure présente, les pressions du surpeuplement et de l'évolution technique accélèrent ce mouvement. La termitière en est arrivée à représenter un idéal réalisable et même, aux yeux de certains, souhaitable. »

Termitière ? Plus effrayant encore ce passage – car tous les mots sont rentrés dans notre lexique :

« Ainsi que l'a montré Mr. William Whyte dans son remarquable ouvrage, The Organization man, une nouvelle Morale Sociale est en train de remplacer notre système traditionnel qui donne la première place à l'individu. Les mots clefs en sont : « ajustement », « adaptation », « comportement social ou antisocial », « intégration », « acquisition de techniques sociales », « travail d'équipe », « vie communautaire », « loyalisme communautaire », « dynamique communautaire », « pensée communautaire », « activités créatrices communautaires »…

Car l’ingénierie sociale c’est la fin du christianisme et même du Christ :

« Selon la Morale Sociale, Jésus avait complètement tort quand il affirmait que le sabbat a été fait pour l'homme pour l'homme; au contraire, c'est l'homme qui. a été fait pour le sabbat, qui doit sacrifier ses particularités natives et faire semblant d'être la sorte de bon garçon invariablement liant que les organisateurs d'activités collectives considèrent comme le plus propre à leurs fins. »

En bon patricien britannique (voyez mon livre sur Tolkien, mes essais sur Chesterton), Huxley refuse cet assemblage :

« Un gouffre immense sépare l'insecte social du mammifère avec son gros cerveau, son instinct grégaire très mitigé et ce gouffre demeurerait, même si l'éléphant s'efforçait d'imiter la fourmi. Malgré tous leurs efforts, les hommes ne peuvent que créer une organisation et non pas un organisme social. En s'acharnant à réaliser ce dernier, ils parviendront tout juste à un despotisme totalitaire. »

Le futur indolore de la domination est programmé :

« Dans les dictatures plus efficaces de demain, il y aura sans doute beaucoup moins de force déployée. Les sujets des tyrans à venir seront enrégimentés sans douleur par un corps d'ingénieurs sociaux hautement qualifiés. »

Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt :

Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt :

« Les forces impersonnelles du surpeuplement et de l'excès d'organisation jointes aux ingénieurs sociologues qui essaient de les diriger, nous poussent vers un nouveau système médiéval. »

Huxley annonce la propagande à venir en occident :

« La propagande pour une action dictée par des impulsions plus basses que l'intérêt présente des preuves forgées, falsifiées, ou tronquées, évite les arguments logiques et cherche à influencer ses victimes par la simple répétition de slogans, la furieuse dénonciation de boucs émissaires étrangers ou nationaux, et l'association machiavélique des passions les plus viles aux idéaux les plus élevés… »

Huxley méprise la liberté de la presse en rappelant ce simple fait :

« En ce qui concerne la propagande, les premiers partisans de l'instruction obligatoire et d'une presse libre ne l'envisageaient que sous deux aspects : vraie ou fausse. Ils ne prévoyaient pas ce qui, en fait, s'est produit- le développement d'une immense industrie de l'information, ne s'occupant dans l'ensemble ni du vrai, ni du faux, mais de l'irréel et de l'inconséquent à tous les degrés. En un mot, ils n'avaient pas tenu compte de la fringale de distraction éprouvée par les hommes. »

On retombe dans le pain et les jeux de Juvénal :

« Pour trouver une situation comparable, fût-ce de loin, à celle qui existe actuellement, il nous faut remonter jusqu'à la Rome impériale, où la populace était maintenue dans la bonne humeur grâce à des doses fréquentes et gratuites des distractions les plus variées, allant des drames en vers aux combats de gladiateurs, des récitations de Virgile aux séances de pugilat, des concerts aux revues militaires et aux exécutions publiques. Mais même à Rome, il n'existait rien de semblable aux distractions ininterrompues fournies par les journaux, les revues, la radio, la télévision et le cinéma. »

Une prédiction (prédiction ou constatation ?) terrible :

« Une société dont la plupart des membres passent une grande partie de leur temps, non pas dans l'immédiat et l'avenir prévisible, mais quelque part dans les autres mondes inconséquents du sport, des feuilletons, de la mythologie et de la fantaisie métaphysique, aura bien du mal à résister aux empiétements de ceux qui voudraient la manipuler et la dominer. »

Le futur est à la « distraction ininterrompue » qui se mêlera à la propagande.

Huxley cite Albert Speer. Après Hitler on n’a pas arrêté le progrès.

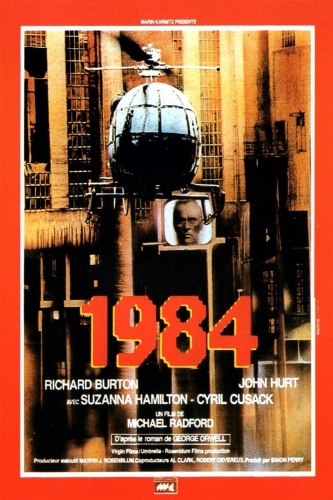

« Depuis l'époque de Hitler, l'arsenal des moyens techniques à la disposition de l'aspirant-dictateur a été considérablement développé! En plus de la radio, du haut-parleur, de la caméra de cinéma et de la presse rotative, le propagandiste contemporain peut faire usage de la télévision pour transmettre non seulement la voix, mais l'image de son client et enregistrer le tout sur des bandes magnétiques. Grâce aux progrès techniques, le Grand Frère peut maintenant être omniprésent presque autant que Dieu. D'ailleurs, il n'y a pas que dans ce domaine que des atouts nouveaux ont été apportés au jeu du dictateur. Depuis Hitler, des travaux considérables ont été faits en psychologie et neurologie appliquées, domaines d'élection du propagandiste, de l'endoctrineur, et du laveur de cerveaux. »

Puis Huxley compare Hitler à Bernays, l’inventeur de la cigarette pour les femmes :

« C'est par la manipulation de « forces cachées » que les experts en publicité vous incitent à acheter leurs produits - une pâte dentifrice, une marque de cigarettes, un candidat politique - et c'est en faisant appel aux mêmes, ainsi qu'à d'autres trop dangereuses pour que s'y frotte Madison Avenue, que Hitler a incité les masses allemandes à s'acheter un Führer, une philosophie insane et une Deuxième Guerre mondiale. »

Après Hitler, la publicité commerciale. Huxley cite Vance Packard et ajoute :

« Nous n'achetons plus des oranges, mais de la vitalité. Nous n'achetons plus une voiture, mais du prestige. » Il en est de même pour tout le reste. Avec un dentifrice, nous achetons non plus un simple détersif antiseptique, mais la libération d'une angoisse : celle d'être sexuellement repoussant. Avec la vodka et le whisky, nous n'achetons pas un poison protoplasmique qui, à doses faibles, peut déprimer le système nerveux de manière utile au point de vue psychologique, nous achetons de l'amabilité, du liant, la chaleur… Avec l'ouvrage à succès du mois, nous acquérons de la culture, l'envie de nos voisins moins intellectuels et le respect des raffinés. »

Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé :

Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé :

« Comme on pouvait s'y attendre, les jeunes sont extrêmement sensibles à la propagande. Ignorants du monde et de ses usages, ils sont absolument sans méfiance, leur esprit critique n'est pas encore développé, les plus petits n'ont pas atteint l'âge de raison et les plus âgés n'ont pas acquis l'expérience sur laquelle leur faculté de raisonnement nouvellement découverte pourrait s'exercer. En Europe, les conscrits étaient désignés sous le nom badin de « chair à canon ». Leurs petits frères et leurs petites sœurs sont maintenant devenus de la chair à radio et à télévision. Dans mon enfance, on nous apprenait à chanter de petites rengaines sans grand sens ou, dans les familles pieuses, des cantiques. Aujourd'hui, les petits gazouillent de la publicité chantée. »

Pas d’illusions sur les élections et la politique :

« Les partis mettent leurs candidats et leurs programmes sur le marché en utilisant les mêmes méthodes que le monde des affaires pour vendre ses produits… Les services de ventes politiques ne font appel qu'aux faiblesses de leurs électeurs, jamais à leur force latente. Ils se gardent bien d'éduquer les masses et de les mettre en mesure de se gouverner elles-mêmes, jugeant très suffisant de les manipuler et de les exploiter. »

Sur le lavage de cerveau pratiqué dans notre planète-prison, Huxley rappelle :

« Si le système nerveux central du chien peut être brisé, celui d'un prisonnier politique aussi. Il s'agit seulement d'appliquer les doses de tension voulues pendant le temps voulu. A la fin du traitement, l'interné sera dans un état de névrose ou d'hystérie tel qu'il avouera ce que ses geôliers voudront. »

Huxley explique pourquoi notre système de suggestibilité encourage le somnambulisme puis il rappelle tristement :

« L'efficacité de la propagande politique et religieuse dépend des méthodes employées et non pas des doctrines enseignées. Ces dernières peuvent être vraies ou fausses, saines ou pernicieuses, peu importe. Si l'endoctrinement est bien fait au stade voulu de l'épuisement nerveux, il réussira. »

Opiomanie ou toxicomanie ? Huxley rappelle ici le fameux soma de son roman :

« La ration de soma quotidienne était une garantie contre l'inquiétude personnelle, l'agitation sociale et la propagation d'idées subversives. Karl Marx déclarait que la religion était l'opium du peuple, mais dans le Meilleur des Mondes la situation se trouvait renversée : l'opium, ou plutôt le soma, était la religion du peuple. »

Huxley rappelle nos progrès en chimie du cerveau et il prophétise l’addiction américaine responsable aujourd’hui de dizaines de milliers de morts :

« …prenez le cas des barbituriques et des tranquillisants. Aux U.S.A., ces remèdes peuvent être obtenus avec une simple ordonnance de docteur, mais l'avidité du public américain pour quelque chose qui rendra un peu plus supportable la vie dans le milieu urbain et industriel est si grande, que les médecins ordonnent actuellement de ces spécialités au rythme de 48 millions de prescriptions par an. »

On contrôlera donc l’opposition politique par les tranquillisants !

« Les masses ne risqueront pas de créer la moindre difficulté à leur maître. Seulement, dans l'état actuel des choses, les tranquillisants peuvent empêcher certaines personnes de créer assez de difficulté, non seulement à leurs dirigeants, mais à elles-mêmes. »

On peut même gagner la guerre par les tranquillisants !

« Lors d'une récente conférence sur le méprobamate, à laquelle je participais, un éminent biochimiste proposa en riant que le gouvernement des U.S.A. envoyât gratuitement au peuple soviétique 50 milliards de doses du plus populaire des tranquillisants. La plaisanterie avait son côté inquiétant. »

Chez Huxley comme chez La Boétie le fond du problème n’est pas la malignité de la science ou des élites sinon la médiocrité de la nature humaine démontrée ici par la science...

« Les idéaux de la démocratie et de la liberté se heurtent au fait brutal de la suggestibilité humaine. Un cinquième de tous les électeurs peut être hypnotisé presque en un clin d'œil, un septième soulagé de ses souffrances par des piqûres d'eau, un quart suggestionné avec rapidité et dans l'enthousiasme par I'hypnopédie. A toutes ces minorités trop promptes à coopérer, on doit ajouter les majorités aux réactions moins rapides dont la suggestibilité plus modérée peut être exploitée par n'importe quel manipulateur connaissant son affaire, prêt à y consacrer le temps et les efforts nécessaires. »

Quant au futur, no comment :

Quant au futur, no comment :

« La liberté individuelle est-elle compatible avec un degré élevé de suggestibilité? Les institutions démocratiques peuvent-elles survivre à la subversion exercée du dedans par des spécialistes habiles dans la science et l'art d'exploiter la suggestibilité à la fois des individus et des foules? »

Il reste que le futur, en 1957, c’est aussi, c’est surtout cent millions de couillonnes sur Instagram admirant et imitant Kylie Jenner. Huxley :

« Et l'uniformisation des êtres était encore parachevée après la naissance par le conditionnement infantile, l'hypnopédie et l'euphorie chimique destinée à remplacer la satisfaction de se sentir libre et créateur. Dans le monde où nous vivons, ainsi qu'il a été indiqué dans des chapitres précédents, d'immenses forces impersonnelles tendent vers l'établissement d'un pouvoir centralisé et d'une société enrégimentée. La standardisation génétique est encore impossible, mais les Gros Gouvernements et les Grosses Affaires possèdent déjà, ou posséderont bientôt, tous les procédés pour la manipulation des esprits décrits dans Le Meilleur des Mondes, avec bien d'autres que mon manque d'imagination m'a empêché d'inventer. »

Le monde une prison, conclue Hamlet avec Rosencrantz et Guildenstern.

Huxley poursuit cruellement par les banalités d’usage sur l’éducation qui nous rendrait résistant :

« Si nous voulons éviter ce genre de tyrannie, il faut que nous commencions sans délai notre éducation et celle de nos enfants pour nous rendre aptes à être libres et à nous gouverner nous-mêmes. »

Cette éducation (cf. la chasse aux fake news) peut aisément être recyclée en ce que l’on sait !

Il rappelle ce truisme :

« Les effets d'une propagande mensongère et pernicieuse ne peuvent être neutralisés que par une solide préparation à l'art d'analyser ses méthodes et de percer à jour ses sophismes. »

Huxley rappelle à temps que personne ne veut de contre-propagande !

« Et pourtant, nulle part on n'enseigne aux enfants une méthode systématique pour faire le départ entre le vrai et le faux, une affirmation sensée et une autre qui ne l'est pas. Pourquoi? Parce que leurs aînés, même dans les pays démocratiques, ne veulent pas qu'ils reçoivent ce genre d'instruction. Dans ce contexte, la brève et triste histoire de l'Institute for Propaganda Analysis est terriblement révélatrice. Il avait été fondé en 1937, alors que la propagande nazie faisait le plus de bruit et de ravages, par Mr. Filene, philanthrope de la Nouvelle-Angleterre. Sous ses auspices, on pratiqua la dissection des méthodes de propagande non rationnelle et l'on prépara plusieurs textes pour l'instruction des lycéens et des étudiants. Puis vint la guerre, une guerre totale, sur tous les fronts, celui des idées au moins autant que celui des corps. Alors que tous les gouvernements alliés se lançaient dans “la guerre psychologique”, cette insistance sur la nécessité de disséquer la propagande sembla quelque peu dépourvue de tact. L'Institut fut fermé en 1941. »

Huxley rappelle les raisons de cette timidité :

« L'examen trop critique par trop de citoyens moyens de ce que disent leurs pasteurs et maîtres pourrait s'avérer profondément subversif. Dans sa forme actuelle, l'ordre social dépend, pour continuer d'exister, de l'acceptation, sans trop de questions embarrassantes, de la propagande mise en circulation par les autorités et de celle qui est consacrée par les traditions locales. »

Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

« Il est parfaitement possible qu'un homme soit hors de prison sans être libre, à l'abri de toute contrainte matérielle et pourtant captif psychologiquement, obligé de penser, de sentir et d'agir comme le veulent les représentants de l'Etat ou de quelque intérêt privé à l'intérieur de la nation. »

Huxley recommande de protéger les lieux publics et la télévision. Or on ne peut protéger les lieux publics et la télévision qui ne sont là que pour vendre et pour puer : il faut donc les éviter. Si ton œil t’est objet de tentation…

Il note justement que « les formes libérales serviront simplement à masquer et à enjoliver un fond situé aux antipodes du libéralisme », et que le futur n’est guère plus joyeux que le présent de Bernays : « Entre-temps, l'oligarchie au pouvoir et son élite hautement qualifiée de soldats, de policiers, de fabricants de pensée, de manipulateurs mentaux mènera tout et tout le monde comme bon lui semblera. »

Sur notre futur monopolistique, Huxley ne se fait guère d’illusions (qui s’en fait encore ?) :

« Mais c'est un fait historique aujourd'hui que les moyens de production sont rapidement centralisés et monopolisés par les Grosses Affaires et les Gros Gouvernements. Par conséquent, si vous avez foi en la démocratie, prenez des mesures pour distribuer les biens aussi largement que possible. »

Huxley, beaucoup moins méchant que ce que pensent pas mal d’antisystèmes, propose une solution de révolution médiévale digne de Chesterton et Belloc :

« Par conséquent, si vous souhaitez éviter l'appauvrissement spirituel des individus et de sociétés entières, quittez les grands centres et faites revivre les petites agglomérations rurales, ou encore humanisez la ville en créant à l'intérieur du réseau de son organisation mécanique, les équivalents urbains des petits centres ruraux où les individus peuvent se rencontrer et coopérer en qualité de personnalités complètes, et non pas comme de simples incarnations de fonctions spécialisées. »

Mais rien n’y fait (on est à l’époque du génial Mumford) :

« Nous savons que, pour la plupart de nos semblables, la vie dans une gigantesque ville moderne est anonyme, atomique, au-dessous du niveau humain, néanmoins les villes deviennent de plus en plus démesurées et le mode de vie urbano-industriel demeure inchangé. »

Huxley, qui finit par citer Dostoïevski et son grand inquisiteur, ne se fait guère d’illusions, sondages à l’appui :

« Aux U.S.A. - et l'Amérique est l'image prophétique de ce que sera le reste du monde urbano-industriel dans quelques années d'ici - des sondages récents de l'opinion publique ont révélé que la majorité des adolescents au-dessous de vingt ans, les votants de demain, ne croient pas aux institutions démocratiques, ne voient pas d'inconvénient à la censure des idées impopulaires, ne jugent pas possible le gouvernement du peuple par le peuple et s'estimeraient parfaitement satisfaits d'être gouvernés d'en haut par une oligarchie d'experts assortis, s'ils pouvaient continuer à vivre dans les conditions auxquelles une période de grande prospérité les a habitués. »

Les jeunes sont soumis, les ados sont pires que les autres, comme je l’ai constaté dans ma jeunesse et comme le montrera le succès mondial de culture sexe, drogue, rock. Huxley :

« Que tant de jeunes spectateurs bien nourris de la télévision, dans la plus puissante démocratie du monde, soient si totalement indifférents à l'idée de se gouverner eux-mêmes, s'intéressent si peu à la liberté d'esprit et au droit d'opposition est navrant, mais assez peu surprenant. »

Il évoque les oiseaux (La Boétie évoquait les chiens) …

« Tout oiseau qui a appris à gratter une bonne pitance d'insectes et de vers sans être obligé de se servir de ses ailes renonce bien vite au privilège du vol et reste définitivement à terre. »

La suite est lyrique !

« Le cri de « Donnez-moi la télévision et des saucisses chaudes, mais ne m'assommez pas avec les responsabilités de l'indépendance », fera peut-être place, dans des circonstances différentes à celui de « La liberté ou la mort ».

Et le maître de conclure :

« Il semble qu'il n'y ait aucune raison valable pour qu'une dictature parfaitement scientifique soit jamais renversée. »

Demandez à Zuckerberg, à la NSA et à Monsanto ce qu’ils en pensent.

Sources complémentaires

Huxley – Le meilleur des mondes ; retour au meilleur des mondes (1957), sur archive.org

Nicolas Bonnal – Comment les peuples sont devenus jetables ; comment les Français sont morts ; la culture comme arme de destruction massive (Amazon.fr)

Umberto Eco – Vers un nouveau moyen âge (1972)

Bertrand de Jouvenel – Du Pouvoir (Pluriel)

Vince Packard – Hidden persuaders

Armand Mattelart – Histoire de l’utopie planétaire (la Découverte)

Chesterton – What I saw in America (Gutenberg.org)

Shakespeare – Mesure pour mesure ; Hamlet ; La tempête (inlibroveritas.net)

La Boétie – Sur la servitude volontaire (Wikisource)

Tocqueville – De la démocratie en Amérique (classiques.Uqac.ca)

Debord – Commentaires

« Il y a vingt ans que Louis Pauwels est mort. Ce nom ne dit peut-être rien aux jeunes gens d’aujourd’hui ; il disait beaucoup à ceux des années quatre-vingt – ils manifestaient contre « la loi Devaquet », les anciens de 68 les brossaient dans le sens du duvet et Pauwels, lui, « n’ayant pas de minus à courtiser », leur dit virilement qui ils étaient : « les enfants du rock débile, les écoliers de la vulgarité pédagogique, les béats de Coluche et Renaud nourris de soupe infra-idéologique cuite au show-biz, ahuris par les saturnales de “touche pas à mon pote”, et, somme toute, les produits de la culture Lang ». La suite de ce « Monôme des zombies », publié le 6 décembre 1986 dans Le Figaro Magazine, n’était pas moins fouetteur : « Ils ont reçu une imprégnation morale qui leur fait prendre le bas pour le haut. Rien ne leur paraît meilleur que n’être rien, mais tous ensemble, pour n’aller nulle part. […] C’est une jeunesse atteinte d’un sida mental. »

« Il y a vingt ans que Louis Pauwels est mort. Ce nom ne dit peut-être rien aux jeunes gens d’aujourd’hui ; il disait beaucoup à ceux des années quatre-vingt – ils manifestaient contre « la loi Devaquet », les anciens de 68 les brossaient dans le sens du duvet et Pauwels, lui, « n’ayant pas de minus à courtiser », leur dit virilement qui ils étaient : « les enfants du rock débile, les écoliers de la vulgarité pédagogique, les béats de Coluche et Renaud nourris de soupe infra-idéologique cuite au show-biz, ahuris par les saturnales de “touche pas à mon pote”, et, somme toute, les produits de la culture Lang ». La suite de ce « Monôme des zombies », publié le 6 décembre 1986 dans Le Figaro Magazine, n’était pas moins fouetteur : « Ils ont reçu une imprégnation morale qui leur fait prendre le bas pour le haut. Rien ne leur paraît meilleur que n’être rien, mais tous ensemble, pour n’aller nulle part. […] C’est une jeunesse atteinte d’un sida mental. »

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. »

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. » La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) :

La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) : Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt :

Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt : Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé :

Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé : Quant au futur, no comment :

Quant au futur, no comment : Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

En otro momento de la entrevista, Tom Wolfe explica cómo, en su opinión, parte del voto a Donald Trump se comprende por la desolación de quienes se sienten en una status social inferior o de quienes creen que han descendido de status. “En ‘Radical chic’ describí el nacimiento de lo que hoy yo denominaría como ‘izquierda caviar’ o ‘progresismo de limusina’. Se trata de una izquierda que se ha liberado de cualquier responsabilidad con respecto a la clase obrera norteamericana. Es una izquierda que adora el arte contemporáneo, que se identifica con las causas exóticas y el sufrimiento de las minorías… pero que no quiere saber nada de las clases menos sofisticadas y adineradas de Ohio" (...)

En otro momento de la entrevista, Tom Wolfe explica cómo, en su opinión, parte del voto a Donald Trump se comprende por la desolación de quienes se sienten en una status social inferior o de quienes creen que han descendido de status. “En ‘Radical chic’ describí el nacimiento de lo que hoy yo denominaría como ‘izquierda caviar’ o ‘progresismo de limusina’. Se trata de una izquierda que se ha liberado de cualquier responsabilidad con respecto a la clase obrera norteamericana. Es una izquierda que adora el arte contemporáneo, que se identifica con las causas exóticas y el sufrimiento de las minorías… pero que no quiere saber nada de las clases menos sofisticadas y adineradas de Ohio" (...)

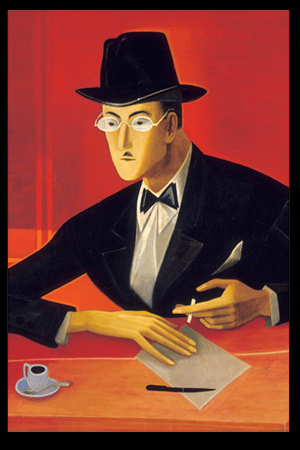

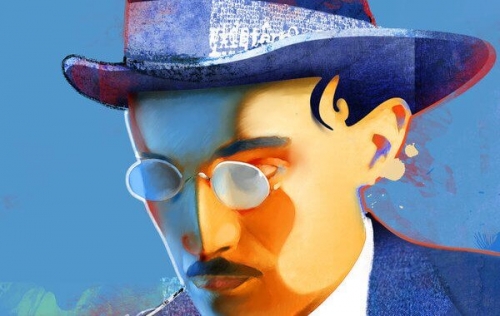

One of his earliest influences was Thomas Carlyle, whose concept of the “hero as poet” as described in Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History made a particular impression on him; from a young age, Pessoa saw his vocation as a poet as an heroic, almost messianic calling.

One of his earliest influences was Thomas Carlyle, whose concept of the “hero as poet” as described in Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History made a particular impression on him; from a young age, Pessoa saw his vocation as a poet as an heroic, almost messianic calling.

Pessoa was also fascinated with the occult and wrote extensively on the subject, largely under his own name. In 1915, he began translating theosophist texts and later claimed to have become a medium with the ability to produce automatic writing. He also claimed to have “sudden flashes of ‘etheric vision'” that enabled him to perceive certain symbols and “auras.”

Pessoa was also fascinated with the occult and wrote extensively on the subject, largely under his own name. In 1915, he began translating theosophist texts and later claimed to have become a medium with the ability to produce automatic writing. He also claimed to have “sudden flashes of ‘etheric vision'” that enabled him to perceive certain symbols and “auras.” The theme of decay and the need for national regeneration runs throughout his political writings, particularly his unfinished “History of a Dictatorship,” a survey of modern Portuguese history in which he attempts to outline the causes for Portugal’s decline.

The theme of decay and the need for national regeneration runs throughout his political writings, particularly his unfinished “History of a Dictatorship,” a survey of modern Portuguese history in which he attempts to outline the causes for Portugal’s decline.

Dans Le Rivage des Syrtes, Julien Gracq prend le contre-pied d’une conception exclusivement négative de la barbarie en la présentant comme un renouveau nécessaire à la revivification d’un vieil État somnolent.

Dans Le Rivage des Syrtes, Julien Gracq prend le contre-pied d’une conception exclusivement négative de la barbarie en la présentant comme un renouveau nécessaire à la revivification d’un vieil État somnolent.  Orsenna est l’image même de l’État stable, depuis si longtemps habitué qu’il en a perdu toute vigueur. « Le rassurant de l’équilibre, c’est que rien ne bouge. Le vrai de l’équilibre, c’est qu’il suffit d’un souffle pour faire tout bouger », ainsi que le fait dire Gracq à Marino, le commandant de l’Amirauté, très attaché au maintien de cet équilibre, satisfait de l’existence sans surprise qu’il entraîne et inquiet du moindre changement. Mais à la tête d’Orsenna, un nouveau maître a l’ambition de secouer les choses : « Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans les hasards. Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans le jeu. » Devant un Aldo effaré, Danielo, l’homme fort de la Seigneurie d’Orsenna, expose sa volonté de sauver Orsenna contre elle-même, contre son « assoupissement sans âge », quitte à l’engager sur un chemin de mort et de destruction. « Quand un État a connu de trop de siècles, dit Danielo, la peau épaissie devient un mur, une grande muraille : alors les temps sont venus, alors il est temps que les trompettes sonnent, que les murs s’écroulent, que les siècles se consomment et que les cavaliers entrent par la brèche, les beaux cavaliers qui sentent l’herbe sauvage et la nuit fraîche, avec leurs yeux d’ailleurs et leurs manteaux soulevés par le vent.

Orsenna est l’image même de l’État stable, depuis si longtemps habitué qu’il en a perdu toute vigueur. « Le rassurant de l’équilibre, c’est que rien ne bouge. Le vrai de l’équilibre, c’est qu’il suffit d’un souffle pour faire tout bouger », ainsi que le fait dire Gracq à Marino, le commandant de l’Amirauté, très attaché au maintien de cet équilibre, satisfait de l’existence sans surprise qu’il entraîne et inquiet du moindre changement. Mais à la tête d’Orsenna, un nouveau maître a l’ambition de secouer les choses : « Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans les hasards. Il y a trop longtemps qu’Orsenna n’a été remise dans le jeu. » Devant un Aldo effaré, Danielo, l’homme fort de la Seigneurie d’Orsenna, expose sa volonté de sauver Orsenna contre elle-même, contre son « assoupissement sans âge », quitte à l’engager sur un chemin de mort et de destruction. « Quand un État a connu de trop de siècles, dit Danielo, la peau épaissie devient un mur, une grande muraille : alors les temps sont venus, alors il est temps que les trompettes sonnent, que les murs s’écroulent, que les siècles se consomment et que les cavaliers entrent par la brèche, les beaux cavaliers qui sentent l’herbe sauvage et la nuit fraîche, avec leurs yeux d’ailleurs et leurs manteaux soulevés par le vent.

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man.

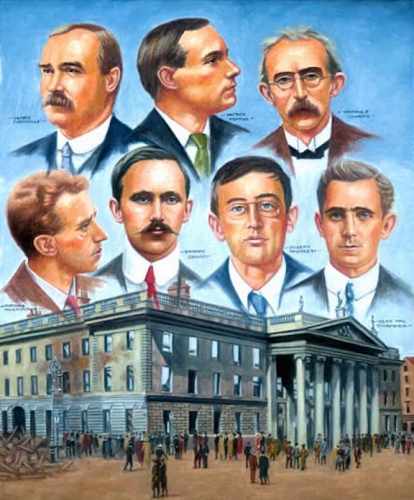

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man. Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

Celle-ci naît à Vichy en 1902 et y meurt en 1943, ce qui pourrait faire penser à une existence tranquille. C’est tout au contraire un parcours semé d’aventures qui caractérise cette femme dont la première passion est le sculpture. Elle est l’élève et le modèle d’Antoine Bourdelle. Elle obtient une première consécration artistique en 1931 à la faveur d’une exposition de ses œuvres au musée du Luxembourg.

Celle-ci naît à Vichy en 1902 et y meurt en 1943, ce qui pourrait faire penser à une existence tranquille. C’est tout au contraire un parcours semé d’aventures qui caractérise cette femme dont la première passion est le sculpture. Elle est l’élève et le modèle d’Antoine Bourdelle. Elle obtient une première consécration artistique en 1931 à la faveur d’une exposition de ses œuvres au musée du Luxembourg. Voici Terne sortant de prison, disculpé et attendu dans un taxi par son épouse qui lui pardonne son aventure extra-conjugale. « Terne avait appris ce matin de bonne heure qu’il était libre et pouvait rentrer chez lui. La levée d’écrou avait eu lieu. Grisonnant, le teint sali par l’insomnie, le colonel paraissait très vieux, marchant lentement, tête basse, le long du corridor froid et sombre. Le gardien lui avait rendu ses effet. C’est-à-dire son col, sa cravate et ses lacets de soulier. Il tenait à la main le sac de toilette en cuir dont les coins s’étaient usés dans les carlingues d’avions. Terne passa la grande voûte d’entrée et se trouva dans la rue la plus lugubre de Paris.

Voici Terne sortant de prison, disculpé et attendu dans un taxi par son épouse qui lui pardonne son aventure extra-conjugale. « Terne avait appris ce matin de bonne heure qu’il était libre et pouvait rentrer chez lui. La levée d’écrou avait eu lieu. Grisonnant, le teint sali par l’insomnie, le colonel paraissait très vieux, marchant lentement, tête basse, le long du corridor froid et sombre. Le gardien lui avait rendu ses effet. C’est-à-dire son col, sa cravate et ses lacets de soulier. Il tenait à la main le sac de toilette en cuir dont les coins s’étaient usés dans les carlingues d’avions. Terne passa la grande voûte d’entrée et se trouva dans la rue la plus lugubre de Paris.

Much of this confusion stems from the fact that National Bolshevism did not have a guiding text or any kind of magnum opus for the proliferation of a workers’ state ruled by nationalist sentiment. The closest to such a founding document is Ernst Junger’s

Much of this confusion stems from the fact that National Bolshevism did not have a guiding text or any kind of magnum opus for the proliferation of a workers’ state ruled by nationalist sentiment. The closest to such a founding document is Ernst Junger’s  Niekisch would become the greatest propagandist for National Bolshevism during the Weimar era. His short-lived journal Widerstand would publish Junger and other German writers who wanted to mix the austere radicalism of the Bolsheviks with that frontline soldier’s dedication to nation.

Niekisch would become the greatest propagandist for National Bolshevism during the Weimar era. His short-lived journal Widerstand would publish Junger and other German writers who wanted to mix the austere radicalism of the Bolsheviks with that frontline soldier’s dedication to nation.

« Ce monde est dérisoire, mais il a mis fin à la possibilité de dire à quel point il est dérisoire ; du moins s’y efforce-t-il, et de bons apôtres se demandent aujourd’hui si l’humour n’a pas tout simplement fait son temps, si on a encore besoin de lui, etc. Ce qui n’est d’ailleurs pas si bête, car le rire, le rire en tant qu’art, n’a en Europe que quelques siècles d’existence derrière lui (il commence avec Rabelais), et il est fort possible que le conformisme tout à fait neuf mais d’une puissance inégalée qui lui mène la guerre (tout en semblant le favoriser sous les diverses formes bidons du fun, du déjanté, etc.) ait en fin de compte raison de lui. En attendant, mon objet étant les civilisations occidentales, et particulièrement la française, qui me semble exemplaire par son marasme extrême, par les contradictions qui l’écrasent, et en même temps par cette bonne volonté qu’elle manifeste, cette bonne volonté typiquement et globalement provinciale de s’enfoncer encore plus vite et plus irrémédiablement que les autres dans le suicide moderne, je crois que le rire peut lui apporter un éclairage fracassant. »

« Ce monde est dérisoire, mais il a mis fin à la possibilité de dire à quel point il est dérisoire ; du moins s’y efforce-t-il, et de bons apôtres se demandent aujourd’hui si l’humour n’a pas tout simplement fait son temps, si on a encore besoin de lui, etc. Ce qui n’est d’ailleurs pas si bête, car le rire, le rire en tant qu’art, n’a en Europe que quelques siècles d’existence derrière lui (il commence avec Rabelais), et il est fort possible que le conformisme tout à fait neuf mais d’une puissance inégalée qui lui mène la guerre (tout en semblant le favoriser sous les diverses formes bidons du fun, du déjanté, etc.) ait en fin de compte raison de lui. En attendant, mon objet étant les civilisations occidentales, et particulièrement la française, qui me semble exemplaire par son marasme extrême, par les contradictions qui l’écrasent, et en même temps par cette bonne volonté qu’elle manifeste, cette bonne volonté typiquement et globalement provinciale de s’enfoncer encore plus vite et plus irrémédiablement que les autres dans le suicide moderne, je crois que le rire peut lui apporter un éclairage fracassant. » « Festivus festivus, qui vient après Homo festivus comme Sapiens sapiens succède à Homo sapiens, est l’individu qui festive qu’il festive : c’est le moderne de la nouvelle génération, dont la métamorphose est presque totalement achevée, qui a presque tout oublié du passé (de toute façon criminel à ses yeux) de l’humanité, qui est déjà pour ainsi dire génétiquement modifié sans même besoin de faire appel à des bricolages techniques comme on nous en promet, qui est tellement poli, épuré jusqu’à l’os, qu’il en est translucide, déjà clone de lui-même sans avoir besoin de clonage, nettoyé sous toutes les coutures, débarrassé de toute extériorité comme de toute transcendance, jumeau de lui-même jusque dans son nom. »

« Festivus festivus, qui vient après Homo festivus comme Sapiens sapiens succède à Homo sapiens, est l’individu qui festive qu’il festive : c’est le moderne de la nouvelle génération, dont la métamorphose est presque totalement achevée, qui a presque tout oublié du passé (de toute façon criminel à ses yeux) de l’humanité, qui est déjà pour ainsi dire génétiquement modifié sans même besoin de faire appel à des bricolages techniques comme on nous en promet, qui est tellement poli, épuré jusqu’à l’os, qu’il en est translucide, déjà clone de lui-même sans avoir besoin de clonage, nettoyé sous toutes les coutures, débarrassé de toute extériorité comme de toute transcendance, jumeau de lui-même jusque dans son nom. » « Dans le nouveau monde, on ne retrouve plus trace du Mal qu’à travers l’interminable procès qui lui est intenté, à la fois en tant que Mal historique (le passé est un chapelet de crimes qu’il convient de ré-instruire sans cesse pour se faire mousser sans risque) et en tant que Mal actuel postiche. »

« Dans le nouveau monde, on ne retrouve plus trace du Mal qu’à travers l’interminable procès qui lui est intenté, à la fois en tant que Mal historique (le passé est un chapelet de crimes qu’il convient de ré-instruire sans cesse pour se faire mousser sans risque) et en tant que Mal actuel postiche. » « …pour en revenir à cette solitude sexuelle d’Homo festivus, qui contient tous les autres traits que vous énumérez, elle ne peut être comprise que comme l’aboutissement de la prétendue libération sexuelle d’il y a trente ans, laquelle n’a servi qu’à faire monter en puissance le pouvoir féminin et à révéler ce que personne au fond n’ignorait (notamment grâce aux romans du passé), à savoir que les femmes ne voulaient pas du sexuel, n’en avaient jamais voulu, mais qu’elles en voulaient dès lors que le sexuel devenait objet d’exhibition, donc de social, donc d’anti-sexuel. »

« …pour en revenir à cette solitude sexuelle d’Homo festivus, qui contient tous les autres traits que vous énumérez, elle ne peut être comprise que comme l’aboutissement de la prétendue libération sexuelle d’il y a trente ans, laquelle n’a servi qu’à faire monter en puissance le pouvoir féminin et à révéler ce que personne au fond n’ignorait (notamment grâce aux romans du passé), à savoir que les femmes ne voulaient pas du sexuel, n’en avaient jamais voulu, mais qu’elles en voulaient dès lors que le sexuel devenait objet d’exhibition, donc de social, donc d’anti-sexuel. »

Polémique pour une autre fois

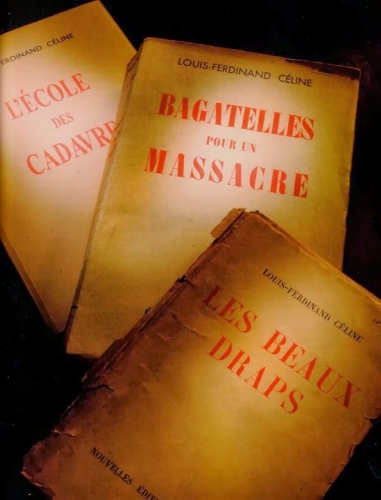

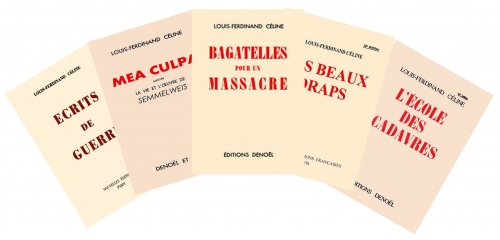

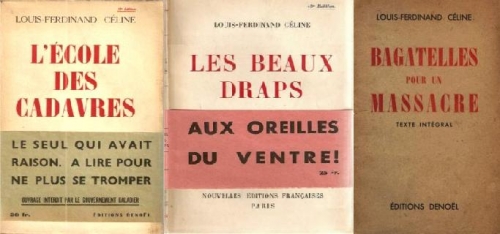

Polémique pour une autre fois Redouter, plus largement, que les pamphlets de Céline ne corrompent la jeunesse, c’est supposer à cette dernière une capacité à lire qu’elle n’a plus. Car Céline n’est pas un écrivain facile, et nullement à la portée de ceux qui, voyous islamistes de banlieue ou petits-bourgeois connectés, ont bénéficié l’enseignement de l’ignorance qui est, selon Michéa, le propre de l’Education nationale. Un état de fait pieusement réfuté, à l’occasion du cinquantenaire de Mai 68, par un magazine officiel qui voit, dans les 50 années qui se sont écoulées, un remarquable progrès de l’enseignement public : ne sommes-nous pas arrivé à 79% de bacheliers, c’est-à-dire un progrès de 20% ? En vérité il faut, en cette matière comme en toutes les autres, inverser le discours : il ne reste plus que 20%, environ, d’élèves à peu près capables de lire et d’écrire correctement le français, et de se représenter l’histoire de France autrement que par le filtre relativiste et mondialiste du néo-historicisme.

Redouter, plus largement, que les pamphlets de Céline ne corrompent la jeunesse, c’est supposer à cette dernière une capacité à lire qu’elle n’a plus. Car Céline n’est pas un écrivain facile, et nullement à la portée de ceux qui, voyous islamistes de banlieue ou petits-bourgeois connectés, ont bénéficié l’enseignement de l’ignorance qui est, selon Michéa, le propre de l’Education nationale. Un état de fait pieusement réfuté, à l’occasion du cinquantenaire de Mai 68, par un magazine officiel qui voit, dans les 50 années qui se sont écoulées, un remarquable progrès de l’enseignement public : ne sommes-nous pas arrivé à 79% de bacheliers, c’est-à-dire un progrès de 20% ? En vérité il faut, en cette matière comme en toutes les autres, inverser le discours : il ne reste plus que 20%, environ, d’élèves à peu près capables de lire et d’écrire correctement le français, et de se représenter l’histoire de France autrement que par le filtre relativiste et mondialiste du néo-historicisme.

Le terme « bushidô », utilisé en ce sens serait apparue pour la première fois dans le koyo gunkan, la chronique militaire de la province du Kai dirigée par le célèbre clan des Takeda (la chronique a été compilée par Kagenori Obata (1572-1663), le fils d’un imminent stratège du clan à partir de 1615. L’historien japonais Yamamoto Hirofumi (Yamamoto Hirofumi, Nihonjin no kokoro : bushidô nyûmon, Chûkei éditions, Tôkyô, 2006), constata au cours de ses recherches l’absence, à l’époque moderne, de textes formulant une éthique des guerriers qui auraient pu être accessibles et respectées par le plus grand nombre des samouraïs. Mieux, les rares textes, formulant et dégageant une éthique propre aux samouraïs (le Hagakure de Yamamoto Tsunetomo et les écrits de Yamaga Sôkô) tous deux intégrés dans le canon des textes de l’idéologie du bushidô, n’ont eu aucune influence avant le XXe siècle.

Le terme « bushidô », utilisé en ce sens serait apparue pour la première fois dans le koyo gunkan, la chronique militaire de la province du Kai dirigée par le célèbre clan des Takeda (la chronique a été compilée par Kagenori Obata (1572-1663), le fils d’un imminent stratège du clan à partir de 1615. L’historien japonais Yamamoto Hirofumi (Yamamoto Hirofumi, Nihonjin no kokoro : bushidô nyûmon, Chûkei éditions, Tôkyô, 2006), constata au cours de ses recherches l’absence, à l’époque moderne, de textes formulant une éthique des guerriers qui auraient pu être accessibles et respectées par le plus grand nombre des samouraïs. Mieux, les rares textes, formulant et dégageant une éthique propre aux samouraïs (le Hagakure de Yamamoto Tsunetomo et les écrits de Yamaga Sôkô) tous deux intégrés dans le canon des textes de l’idéologie du bushidô, n’ont eu aucune influence avant le XXe siècle.

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

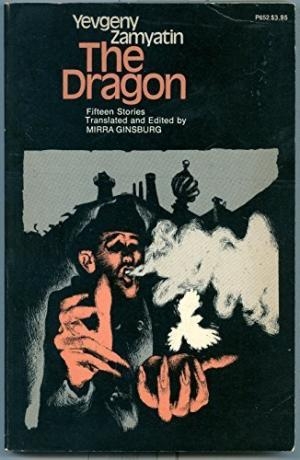

Lo sorprendente es la capacidad de los dragones de unir lo positivo y lo negativo. Matan a los seres humanos, pero son capaces de resucitarles, y devuelven la vida a un ser que está mucho más abajo en la evolución. Por otro lado, vemos que poco significa la vida humana, según el cuento, menos que la de un pájaro. El cuento está lleno de contrastes. Uno de ellos es el personaje del soldado – dragón: asesino y salvador a la vez. Ya la misma ciudad, el espacio en el que se desarrolla la acción está lleno de contradicciones. La ciudad arde, pero está helada. Tenemos las dos fuerzas ancestrales luchando. Estamos en invierno, y la ciudad está congelada, muerta, parada. Al mismo tiempo, el fuego de la revolución la despierta, “ la hace vivir “. Las llamas derriten el hielo, que es la capa que oprime todo, pero también queman, matan.

Lo sorprendente es la capacidad de los dragones de unir lo positivo y lo negativo. Matan a los seres humanos, pero son capaces de resucitarles, y devuelven la vida a un ser que está mucho más abajo en la evolución. Por otro lado, vemos que poco significa la vida humana, según el cuento, menos que la de un pájaro. El cuento está lleno de contrastes. Uno de ellos es el personaje del soldado – dragón: asesino y salvador a la vez. Ya la misma ciudad, el espacio en el que se desarrolla la acción está lleno de contradicciones. La ciudad arde, pero está helada. Tenemos las dos fuerzas ancestrales luchando. Estamos en invierno, y la ciudad está congelada, muerta, parada. Al mismo tiempo, el fuego de la revolución la despierta, “ la hace vivir “. Las llamas derriten el hielo, que es la capa que oprime todo, pero también queman, matan.

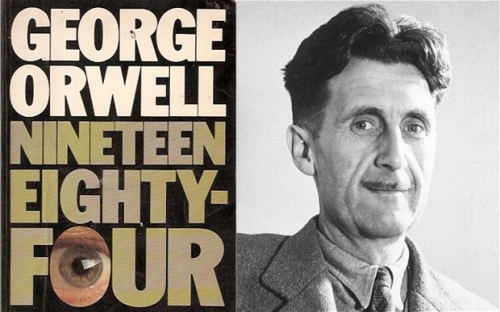

En manipulant les archives, l’on manipule les consciences. Il suffit pour cela de « rectifier » le passé en l’alignant sur les nécessités politiques de l’heure. Si d’aventure il arrive que la mémoire individuelle contredise la mémoire collective ainsi façonnée, la contradiction doit être résolue au profit de la seconde par l’élimination de la première. D’où l’utilité de la « double pensée » pour assurer le triomphe de l’orthodoxie. Il n’y a plus ni réalité ni objectivité. Selon les termes même d’O’Brien, « la réalité n’est pas extérieure. La réalité existe dans l’esprit humain et nulle part ailleurs... Tout ce que le parti tient pour la vérité est la vérité ». Par cette perversion totale de l’histoire et de la conscience historique, on atteint le point extrême de la logique totalitaire.

En manipulant les archives, l’on manipule les consciences. Il suffit pour cela de « rectifier » le passé en l’alignant sur les nécessités politiques de l’heure. Si d’aventure il arrive que la mémoire individuelle contredise la mémoire collective ainsi façonnée, la contradiction doit être résolue au profit de la seconde par l’élimination de la première. D’où l’utilité de la « double pensée » pour assurer le triomphe de l’orthodoxie. Il n’y a plus ni réalité ni objectivité. Selon les termes même d’O’Brien, « la réalité n’est pas extérieure. La réalité existe dans l’esprit humain et nulle part ailleurs... Tout ce que le parti tient pour la vérité est la vérité ». Par cette perversion totale de l’histoire et de la conscience historique, on atteint le point extrême de la logique totalitaire.

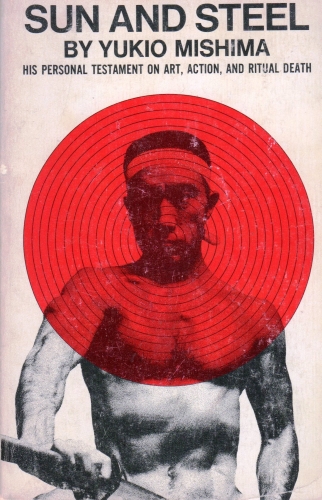

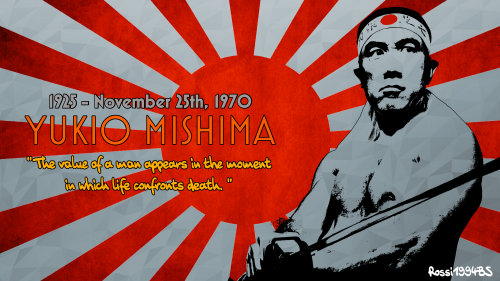

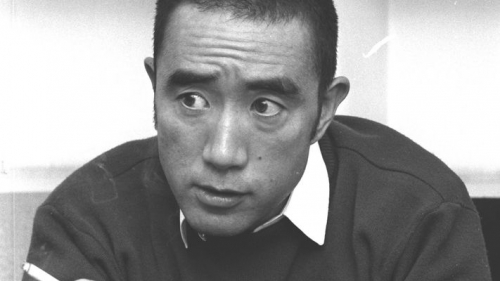

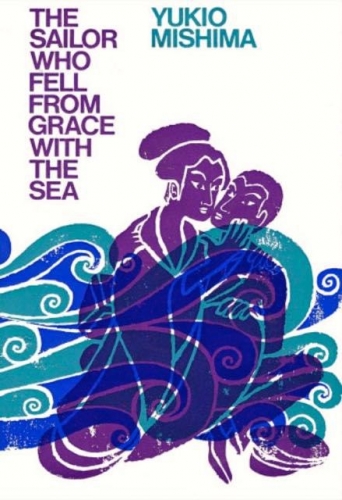

If we take these words out of context but relate them to certain ideas held by Mishima, then these worlds can equally equate to the changing landscape of Japan based on skyscrapers and the dilution of faith and philosophy. In other words, maybe Japan had learned everything under the Meiji Restoration based on the hypocrisy of Western, Catholic, and Islamic empires that utilized fear and control at the drop of a hat. Of course, while Islamization followed the Ottomans and Catholicism followed the Spanish – the British view was that you didn’t have to enslave one hundred percent by destroying indigenous faiths. Instead, the essence of the British Empire was to exploit resources at all costs – while destroying the soul of poor indigenous British nationals based on child labor, the workhouse, and a host of other barbaric realities.

If we take these words out of context but relate them to certain ideas held by Mishima, then these worlds can equally equate to the changing landscape of Japan based on skyscrapers and the dilution of faith and philosophy. In other words, maybe Japan had learned everything under the Meiji Restoration based on the hypocrisy of Western, Catholic, and Islamic empires that utilized fear and control at the drop of a hat. Of course, while Islamization followed the Ottomans and Catholicism followed the Spanish – the British view was that you didn’t have to enslave one hundred percent by destroying indigenous faiths. Instead, the essence of the British Empire was to exploit resources at all costs – while destroying the soul of poor indigenous British nationals based on child labor, the workhouse, and a host of other barbaric realities. Mishima said, “If we value so highly the dignity of life, how can we not also value the dignity of death? No death may be called futile.”

Mishima said, “If we value so highly the dignity of life, how can we not also value the dignity of death? No death may be called futile.”

Ernst Jünger appartient incontestablement à ces lettrés allemands qui s’enracinent dans l’âme germanique afin de mieux la dépasser et ainsi accéder au psyché européen. C’est ce qu’avait compris Dominique Venner dans son Ernst Jünger. Un autre destin européen (Éditions du Rocher, coll. « Biographie », 2009). Venner oublie néanmoins d’évoquer la sortie en 1962 de L’État universel dans lequel Jünger ne cache pas ses intentions mondialistes. « Un mouvement d’importance mondiale, y écrit-il, est, de toute évidence, en quête d’un centre. […] Il s’efforce d’évoluer des États mondiaux à l’État universel, à l’ordonnance terrestre ou globale (L’État universel suivi de La mobilisation totale, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 1990, p. 40). » Pour Jünger, la saturation maximale de la Technique et l’assomption du Travailleur aboutissent à l’État universel. Pourtant, l’intrigue du roman de 1977, Eumeswil, se déroule dans une ère post-historique survenue après l’effondrement de l’État universel et la renaissance des cités-États.

Ernst Jünger appartient incontestablement à ces lettrés allemands qui s’enracinent dans l’âme germanique afin de mieux la dépasser et ainsi accéder au psyché européen. C’est ce qu’avait compris Dominique Venner dans son Ernst Jünger. Un autre destin européen (Éditions du Rocher, coll. « Biographie », 2009). Venner oublie néanmoins d’évoquer la sortie en 1962 de L’État universel dans lequel Jünger ne cache pas ses intentions mondialistes. « Un mouvement d’importance mondiale, y écrit-il, est, de toute évidence, en quête d’un centre. […] Il s’efforce d’évoluer des États mondiaux à l’État universel, à l’ordonnance terrestre ou globale (L’État universel suivi de La mobilisation totale, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 1990, p. 40). » Pour Jünger, la saturation maximale de la Technique et l’assomption du Travailleur aboutissent à l’État universel. Pourtant, l’intrigue du roman de 1977, Eumeswil, se déroule dans une ère post-historique survenue après l’effondrement de l’État universel et la renaissance des cités-États.

Noboru is fascinated with the sea and ships. He convinces his mother to take him to a port, where a sailor by the name of Ryuji Tsukazaki, second mate aboard a freighter ship, shows him around his ship. The reader is introduced to Ryuji when Fusako invites him to the Kurodas’ home and Noboru observes the two embracing through a hole in the wall behind a chest in his bedroom.

Noboru is fascinated with the sea and ships. He convinces his mother to take him to a port, where a sailor by the name of Ryuji Tsukazaki, second mate aboard a freighter ship, shows him around his ship. The reader is introduced to Ryuji when Fusako invites him to the Kurodas’ home and Noboru observes the two embracing through a hole in the wall behind a chest in his bedroom.

The narrator, Mizoguchi, is physically weak, ugly in appearance, and afflicted with a stutter. This isolates him from others, and he becomes a solitary, brooding child. He first learns of the Golden Temple from his father, a frail country priest, and the image of the temple and its beauty becomes for him an idée fixe. The young Mizoguchi worships his vision of temple, but there are omens of what is to come. When a naval cadet visits his village and notices his stutter, Mizoguchi is resentful and retaliates by defacing the cadet’s prized scabbard. From the beginning, he realizes that the beauty of the temple represents an unattainable ideal: “if beauty really did exist there, it meant that my own existence was a thing estranged from beauty” (21). Over time, this seed in his mind metastasizes and begins to consume him.

The narrator, Mizoguchi, is physically weak, ugly in appearance, and afflicted with a stutter. This isolates him from others, and he becomes a solitary, brooding child. He first learns of the Golden Temple from his father, a frail country priest, and the image of the temple and its beauty becomes for him an idée fixe. The young Mizoguchi worships his vision of temple, but there are omens of what is to come. When a naval cadet visits his village and notices his stutter, Mizoguchi is resentful and retaliates by defacing the cadet’s prized scabbard. From the beginning, he realizes that the beauty of the temple represents an unattainable ideal: “if beauty really did exist there, it meant that my own existence was a thing estranged from beauty” (21). Over time, this seed in his mind metastasizes and begins to consume him. All human beings possess a will to power in the Nietzschean sense. This finds its highest expression in self-actualization and self-mastery, and in the achievements of great artists, thinkers, and leaders, but in its lower forms is embodied by the desire of defective beings to assert themselves at all costs. This is manifested in Mizoguchi’s desire to destroy the temple, which intensifies in proportion to his realization that he will never be able to possess it or approach its beauty.

All human beings possess a will to power in the Nietzschean sense. This finds its highest expression in self-actualization and self-mastery, and in the achievements of great artists, thinkers, and leaders, but in its lower forms is embodied by the desire of defective beings to assert themselves at all costs. This is manifested in Mizoguchi’s desire to destroy the temple, which intensifies in proportion to his realization that he will never be able to possess it or approach its beauty.

News of Seth’s victory reaches London where Basil Seal, the ne’er-do-well son of the Conservative Whip and a classmate of Seth’s at Oxford, is recovering from a series of scandalous benders that have forced him to abandon his nascent political career. Desperately in need of money, Seal travels to Azania as a free-lance journalist. Within a short time of his arrival, Basil becomes Seth’s most trusted adviser and is put in charge of the Ministry of Modernization; in effect, Basil has become the real ruler of Azania since Seth spends his time immersed in catalogs and dreaming up more and more ridiculous “progressive” schemes for the betterment of Azanians, such as requiring all citizens to learn Esperanto. The natives who run the other departments are all too happy to refer all business to Basil.

News of Seth’s victory reaches London where Basil Seal, the ne’er-do-well son of the Conservative Whip and a classmate of Seth’s at Oxford, is recovering from a series of scandalous benders that have forced him to abandon his nascent political career. Desperately in need of money, Seal travels to Azania as a free-lance journalist. Within a short time of his arrival, Basil becomes Seth’s most trusted adviser and is put in charge of the Ministry of Modernization; in effect, Basil has become the real ruler of Azania since Seth spends his time immersed in catalogs and dreaming up more and more ridiculous “progressive” schemes for the betterment of Azanians, such as requiring all citizens to learn Esperanto. The natives who run the other departments are all too happy to refer all business to Basil.