Terra Sarda: il mediterraneo metafisico di Ernst Jünger

Andrea Scarabelli

Ex: http://ilgiornale.it/scarabelli

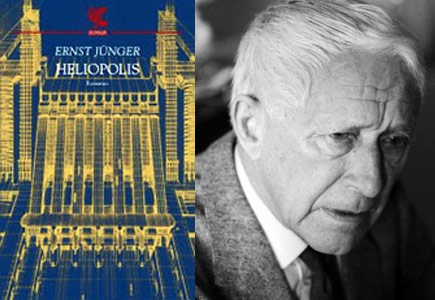

«Insel, insula, isola, Eiland – parole che nominano un segreto, un che di separato e conchiuso»: Ernst Jünger scrisse queste parole a Carloforte. Vi era giunto per la prima volta nel 1955, passando dall’isola di Sant’Antioco, attratto dalla presenza di un insetto che vive solo lì, la Cicindela campestris saphyrina. Le sue impressioni sull’isola sono riportate nel saggio San Pietro (1957), uscito in italiano nel 2015 nella traduzione di Alessandra Iadicicco. Entomologia a parte, era rimasto folgorato dal luogo, trascorrendovi le vacanze fino al 1978, all’età di ottantatré anni. Jünger era un amante delle isole, e i suoi diari (molti dei quali, purtroppo, ancora inediti da noi) stanno a dimostrarlo; del bacino mediterraneo amava soprattutto Sicilia e Sardegna. Il fascino esercitato dalle isole risale all’inizio dei tempi. Per caratteri come quello di Jünger, ogni isola è beata, nel senso di Esiodo (Le opere e i giorni): «Sulle isole beate, presso il profondo gorgo dell’oceano, vivono gli eroi felici col cuore libero da affanni. La terra feconda offre loro il frutto del miele che matura tre volte nell’anno». Anche D. H. Lawrence, tra i molti altri, era stato in Sardegna, precisamente nell’estate del 1921, assieme alla moglie Frieda. Vi era giunto da Taormina e aveva visitato Cagliari, Mandas e Nuoro. Nel suo libro Mare e Sardegna, contenente il racconto di questo viaggio, riporta un’ottima definizione di insulomania, il male di cui soffre chi prova un’attrazione irresistibile verso le isole. «Questi insulomani nati sono diretti discendenti degli Atlantidi e il loro subcosciente anela all’esistenza insulare». Una diagnosi che si attaglia alla perfezione a Jünger, amante del mare e di ciò che il mare circonda, separandolo dalla terraferma.

Come già detto, il futuro Premio Goethe approda a Carloforte nel 1955, ma il suo primo contatto con la Sardegna risale all’anno precedente. Il diario del suo mese trascorso nel piccolo villaggio di Villasimius è uscito in varie edizioni, con il titolo Presso la torre saracena. Tradotto – magistralmente – da Quirino Principe, verrà inserito insieme agli altri “scritti sardi” ne Il contemplatore solitario (Guanda, 2000) e in Terra sarda (Il Maestrale, 1999).

Come già detto, il futuro Premio Goethe approda a Carloforte nel 1955, ma il suo primo contatto con la Sardegna risale all’anno precedente. Il diario del suo mese trascorso nel piccolo villaggio di Villasimius è uscito in varie edizioni, con il titolo Presso la torre saracena. Tradotto – magistralmente – da Quirino Principe, verrà inserito insieme agli altri “scritti sardi” ne Il contemplatore solitario (Guanda, 2000) e in Terra sarda (Il Maestrale, 1999).

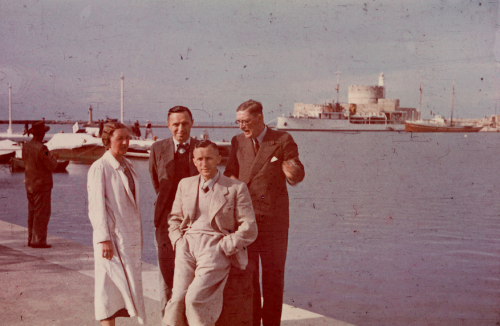

Ecco l’itinerario di quel primo viaggio: partito da Civitavecchia la sera del 6 maggio 1954, il Nostro arriva al porto di Olbia alle prime ore del mattino. Raggiunta Cagliari in treno, un paio d’ore di autobus lo separano da Villasimius (nel diario indicata come Illador): un percorso accidentato, su strade malmesse. Poche case coloniche, il piccolo borgo di Solanas. Dietro a ogni tornante si squadernano panorami mozzafiato, con un mare color zaffiro. Fin da subito capisce di trovarsi in un luogo tagliato fuori dalla civiltà, anche per via di un’epidemia di malaria e una carestia che fino a quel momento hanno reso Villasimius impermeabile al turismo di massa. Ancora per poco, però: proprio nei giorni della sua residenza, gli operai stanno collocando la rete elettrica, dando così il via alla modernizzazione della cittadina, che si concluderà con l’invasione di televisioni, radio, cinema, traffico, caos… La tecnica giungerà, livellando ogni differenza tra sessi e generazioni, demolendo una cultura millenaria e andando a costituire quel brodo di coltura grazie a cui la modernità trionferà anche a Illador. Ma in quel momento di tutto ciò non c’è ancora traccia. La cittadina si trova a un crocevia, e lo scrittore ha modo di fotografarla per quel che fu, «un luogo più cosmico che terrestre, lontano dal mondo». In realtà queste parole sono riferite a Carloforte, ma potrebbero estendersi alla Villasimius di allora, anzi alla Sardegna tutta, che in qualche modo agì su di lui come un «detonatore di emozioni», secondo la definizione di Stenio Solinas, che ha firmato l’introduzione a San Pietro.

Crocevia per la Sardegna, gli anni Cinquanta lo sono anche per Jünger: dopo aver visto l’Europa messa a ferro e fuoco dalle forze scatenate della tecnica, che aveva in qualche modo celebrato nel suo Der Arbeiter, agli inizi degli anni Trenta, il suo sguardo muta radicalmente, dando vita a opere come Il trattato del ribelle, che esce nel 1951, e soprattutto Il libro dell’orologio a polvere, pubblicato lo stesso anno di quel suo primo viaggio sardo. Se il primo è l’invito a riparare in un bosco del tutto interiore, al riparo dalle barbarie della tecnica e della tirannide, l’ultimo è uno studio comparato dedicato agli orologi naturali (clessidre, meridiane, gnomoni e così via) e a quelli meccanici, insieme alle nozioni di tempo che veicolano. Così come c’è un tempo storico, scandito dagli orologi meccanici, ce n’è anche uno cosmico, misurato dalle ombre proiettate dal sole e dall’affastellarsi dei chicchi di grano nelle clessidre. Sarà questa compresenza, come vedremo, a scandire il suo primo soggiorno sardo.

Torniamo alla Villasimius degli anni Cinquanta, la cui case sono ancora illuminate da candele, una cittadina semi-diroccata circondata da immense spiagge deserte e torri in rovina, i cui ospiti non sono miliardari o attricette o parvenu ma pastori, elettricisti, ciabattini e pescatori, insieme a impiegati statali trasferiti lì per qualche oscuro regolamento di conti burocratico. In loro compagnia, annoterà in San Pietro,

«L’uomo della terraferma viene trattato con una benevola superiorità. Gli manca quell’impronta degli elementi che qui ha lasciato il suo segno».

Saranno queste figure semplici, dalla pelle coriacea battuta dal Sole e saggiata dal vento, i compagni di quelle lunghe giornate, anche perché il protagonista della nostra storia si è guardato bene dal portarsi dietro un libro, un giornale o una compagnia umana. Ama stare con la gente comune e partecipa a feste e banchetti, cene e battute di caccia, passeggiate e sessioni di pesca, ben sapendo che è possibile studiare un luogo anche senza orpelli letterario-filosofici. La pensione in cui alloggia – gestita da una certa Signora Bonaria – diventa così il teatro d’interminabili discussioni (ma anche di lunghi silenzi, scanditi da un vino nero come la notte e pranzi pantagruelici). Cogli abitanti del luogo Jünger parla un po’ di tutto, ma perlopiù ascolta, di passato e presente – il futuro, quello, mai – dalle usanze locali alla Storia, che ha ovviamente attraversato anche quei corpi. Dopo cena, talvolta, i doganieri intonano il canto del «Duce Benito», non senza prima essersi tolti le uniformi. Uno dei suoi interlocutori gli dice di esser stato ferito nella Prima Guerra Mondiale e di aver perso un figlio nella seconda. Anche lui ne sa qualcosa. Reclina il capo, mentre il suo pensiero va alle scogliere di marmo di Carrara, dove è caduto suo figlio Ernstel.

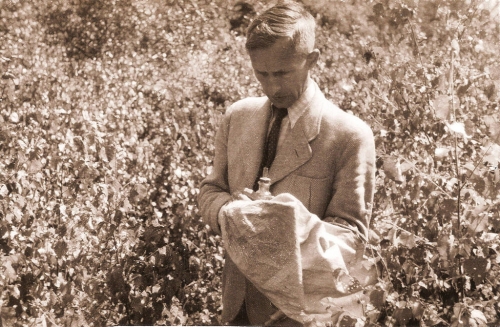

I giorni passano e il Signor Ernesto – così lo chiamano a Illador – fa lunghe passeggiate, attraversando campi imbionditi dai cereali, muraglie di fichi d’India e una macchia mediterranea issatasi eroica sotto un sole sferzante, che dardeggia la costa, irrorata dal mare. Di tanto in tanto il suo sguardo si posa sull’Isola dei Gabbiani e su quella dei Serpenti (oggi Serpentara), nei pressi di Castiadas, sormontate rispettivamente da un castello in rovina e un faro. A colpirlo è l’abbondanza della natura, che non fa economia né lesina in sperperi («è ben oltre la funzionalità», parole che avrebbero sottoscritto Georges Bataille e Marcel Mauss), la stessa che fece esclamare, dall’altra parte del mare, allo Zarathustra nietzschiano:

«Ho imparato questo dal sole, quando il ricchissimo tramonta: getta nel mare l’oro della sua inesauribile ricchezza, così che anche il più povero pescatore rema con remi d’oro! Vidi questo una volta e alla vista non mi saziai di piangere».

Se fu un tramonto ligure a dettare queste parole a Nietzsche, che le scrisse a Rapallo, Jünger cercò il Grande Meriggio di Zarathustra in Sardegna, come disse una volta Banine, sua correttrice di bozze e compagna di viaggio ad Antibes. Ma il Sole e il mare mediterranei gli sussurrano, soprattutto, di avere ancora un’immensa riserva di tempo. E il tempo gli darà ragione, facendolo vivere sino al 1998, all’età di centotré anni.

L’enigma del tempo, che ha incantato Borges e gli spiriti più eletti del Novecento: ecco ciò che Jünger incontra in Sardegna in quella tarda primavera, non ancora estate. Il Contemplatore Solitario si tuffa nel miracolo della storia nei nuraghi presso Macomer, adornati da licheni, che dovettero apparire antichi già ai Fenici. Il suo sguardo si amplia, sfondando gli orizzonti storiografici moderni, andando oltre le sue Colonne d’Ercole, impresa conclusa cinque anni dopo in quello che forse è il suo libro migliore, Al muro del tempo, trattato di metafisica della storia che analizza il tempo storico come una parentesi, nata dalla messa al bando di forze mitiche che stanno per fare ritorno. Ebbene, il passaggio dalla storia del mondo (Weltgeschichte) alla storia della terra (Erdegeschichte) ha luogo forse per la prima volta al cospetto di un nuraghe che, come ha scritto Henri Plard, curatore de Il contemplatore solitario, ricorda a Jünger il fenomeno originario di cui ha parlato il suo maestro Goethe, che si cela dietro a tutte le manifestazioni naturali. Da esso nascerà la torre, il granaio, il castello… Archetipi? Null’affatto. Gli archetipi sono molti, il fenomeno originario è uno.

Questa compresenza, ai suoi occhi, sceglie quello sardo come territorio d’elezione. È come se in certi luoghi la geografia costringesse la storia a venire allo scoperto, esibendo i propri caratteri fondamentali. Anche perché qui il passato vive in una contemporaneità assoluta, plastica. La Sardegna jüngeriana è in grado di cicatrizzare e risanare antiche ferite. Qui tutto è presente, l’eternità coesiste con il tempo: «La storia diventa un mysterium. La successione temporale diventa un’immagine campata nello spazio», parole che – come scrive Quirino Principe – ricordano quelle di Gurmenanz del Parsifal wagneriano: «Figlio mio, qui il tempo diventa spazio». Il cerchio si chiude.

Il sigillo di quel viaggio è una fuoriuscita dalla storia non veicolata dalla ratio ma dalla contemplazione delle forme, del loro stile. È nella continuità delle forme, nella loro metamorfosi, a manifestarsi il fenomeno originario. Che non è un’idea astratta, ma qualcosa d’immanente al reale, la messa in forma di un destino e allo stesso tempo la sua più alta meta. Contemplando il reale e non dissezionandolo, come fa invece la scienza moderna, ci reinseriamo nei meccanismi che regolano il cosmo. Ciò è molto facile in Sardegna – e in Italia – scrive Jünger, dove la compresenza di presente e futuro è visibile a livello geografico, territoriale, elementare, ma anche fisiognomico. Lì può accadere, passeggiando per luoghi affollati, d’incontrare un viso particolare, con tratti inusuali. Allora ci fermiamo, percorsi da un brivido. I tratti intravisti sono antichi, forse addirittura preistorici, e l’osservazione si spinge allora sempre più a ritroso, nelle profondità dei secoli e dei millenni, fino al limite estremo del muro del tempo. «Sentiamo che ci è passato vicino un essere originario, primordiale, venuto a noi da tempi in cui non esistevano né popoli né paesi». Ma la stessa cosa accade anche se ci mettiamo a riflettere su noi stessi: per quale motivo non siamo tutti uguali, ma nutriamo peculiari inclinazioni per la caccia o la pesca, per la contemplazione o l’azione, «per lo scontro in battaglia, per l’occulta magia degli esorcismi? Seguendo le nostre vocazioni, consumiamo la nostra più antica parte di eredità. Abbandoniamo il mondo storico, e antenati sconosciuti festeggiano in noi il loro ritorno».

È la contemplazione e non l’analisi a permettere questa fuoriuscita dal tempo – la stessa di cui parlò Mircea Eliade, che tra l’altro diresse con Jünger «Antaios», dall’inizio degli anni Sessanta a metà dei Settanta. Ebbene, sulle colonne di quella meravigliosa rivista uscì, nel 1963, lo scritto jüngeriano Lo scarabeo spagnolo, sempre nato in terra sarda. Qui la meditazione su uno scarabeo intravisto sul gretto di un fiume (Riu Campus) diventa occasione per riflettere sulla caducità delle cose. Tutto muore e trapassa nell’inorganico, ma guai a chi non lo inserisce in un contesto più alto. Guai a chi si esaurisce nel presente, nella storia. Guai a non vedere nel transeunte l’orma dell’eterno. Chi abbia il coraggio di avventurarsi nei labirinti della contemplazione, tuttavia, scoprirà scenari inediti, all’interno dei quali anche l’uomo acquisisce facoltà nuove:

«Ognuno è re di Thule, è sovrano agli estremi confini, è principe e mendicante. Se sacrifica l’aurea coppa della vita alla profondità, offre testimonianza della pienezza cui la coppa rinvia e che egli incarna senza poterla comprendere. Come lo splendore dello scarabeo spagnolo, così le corone regali alludono a una signoria che nessuna conflagrazione universale distrugge. Nei suoi palazzi la morte non penetra; è solo la guardiana della porta. Il suo portale rimane aperto mentre stirpi di uomini e di dèi si avvicendano e scompaiono».

Avventurandoci in questa Babele di dimensioni storiche e piani dell’essere, lo stesso linguaggio finisce per rivelare la propria insufficienza e naufraga, laddove la traiettoria di un insetto è in grado di ripetere il moto planetario. Servendoci di un’antica immagine, il linguaggio discorsivo è come una canoa utile per attraversare un fiume, ma che una volta espletato questo compito va abbandonata a riva. Il percorso deve proseguire in altro modo. Così sono i nomi, che non si limitano a designare cose, ma rinviano sempre a qualcos’altro,

«ombre d’invisibili soli, orme su vasti specchi d’acqua, colonne di fumo che s’innalzano da incendi il cui sito è nascosto. Là il grande Alessandro non è più grande del suo schiavo, ma è più grande della propria fama. Anche gli dèi, là, sono soltanto simboli. Tramontano come i popoli e le stelle, eppure hanno valore i sacrifici che li onorano».

Come già accennato, i diari di Illador-Villasimius sono dedicati alla Torre Saracena di Capo Carbonara; vi si arriva facilmente, percorrendo un sentiero – nulla di particolarmente impegnativo – che dalla lunga spiaggia bianca porta alle pendici dell’antica torre di vedetta. L’11 maggio, ai piedi della solitaria costruzione arroventata dal sole (oggi conosciuta come Torre di Porto Giunco), Jünger avverte «un alito di nuda potenza, di pallida vigilanza». Un sentore di perenne insicurezza, d’instabilità. Comprende di trovarsi in un luogo di confine, Giano bifronte che unisce e separa a un tempo, linea di frontiera tra Oriente e Occidente, storia e metastoria. Segno liminare tra terra e mare che impone un aut-aut, ci torna una decina di giorni dopo, assieme a un certo Angelo (uomo mercuriale), armato di martello e scalpello. Lascia una traccia, com’era – ed è tutt’ora – uso fare. Quella traccia è ancora lì, a distanza di oltre cinquant’anni: E. J., 22.V.54. Dopodiché ridiscende il sentiero, fino alla spiaggia. Guardandola dall’alto, si è accorto che presenta singolari striature rosate: sono conchiglie frantumate. Frugando, ne trova una semi-intatta, la cui forma lo sgomenta. È una conchiglia a forma di cuore, la cui perfezione formale rimanda a un ordine che è di questo mondo ma in esso non si esaurisce. È come se la bacchetta di un direttore invisibile avesse dato il la a un’esecuzione di cui non udiamo che gli echi. E, ancora una volta, ecco emergere dalla contemplazione la Terra originaria, in una magnifica assenza di umanità. È ad essa che il piccolo oggetto rinvia: una proprietà, annota Jünger, ben nota a quei popoli antichi che utilizzavano le conchiglie come moneta, al posto dell’oro. La sua forma potrebbe condurci

«a fiammeggianti soli. Colui che vaga per la nostra terra la esibisce come un geroglifico. Il guardiano del portone di fiamma vede a quale sublime configurazione è adatta la polvere che turbina su questa stella. Qualcosa d’immortale lo illumina. Dà il suo segnale: la conchiglia si trasforma in ardore incandescente, in luce, in pura irradiazione. Il portone si apre di scatto».

Abbiamo detto che la Sardegna segna, in qualche modo, l’approdo di Jünger ai grandi spazi di una storiografia ultraeuclidea, mostrandogli un territorio innervato da un destino antecedente a quello dei manuali. I nuraghi precedono le piramidi, le mura di Ilio e il palazzo di Agamennone. Un giorno si trova nei pressi di Punta Molentis, al largo della quale si dice esserci un antico porto sommerso. Chissà, magari a questo porto corrisponde anche una città, secondo un’antica leggenda diffusa in tutte le coste mediterranee. È un’immagine molto potente del senso della storia. Come ha scritto Predrag Matvejević nel suo magnifico Breviario mediterraneo,

«un porto affondato è una specie di necropoli. Divide lo stesso destino delle città o delle isole sommerse: circondato dagli stessi misteri, accompagnato da questioni simili, seguito dagli stessi ammonimenti. Ciascuno di noi è talvolta un porto affondato, nel Mediterraneo».

Sempre nei pressi di Punta Molentis, dove un’esile lingua di sabbia separa i due mari, trova un’antichissima grotta, addirittura più vecchia degli stessi nuraghi. È stupefatto: per inquadrare questa rudimentale abitazione, occorre adottare scale temporali molto più ampie di quelle storiografiche. Luoghi del genere intimano al visitatore di confrontarsi con regioni sommerse del proprio Io, abbandonando gli orpelli mentali usuali:

«A volte, l’uomo è costretto dall’urgenza del destino a uscire dai palazzi della storia, a venire al cospetto di questa sua primitiva dimora, a domandarsi se ancora la riconosca, se sia ancora alla sua altezza, se ne sia ancora degno. Qui egli è processato e giudicato dall’Immutabile che persiste al fondo della storia».

L’uomo tende a ricacciare questo Immutabile in un lontanissimo passato, nell’alba dei tempi. Una sciocchezza: esso è «al centro, nel punto più interno della foresta, e le civiltà gli girano intorno». Al pari del mito che, come aveva scritto nel Trattato del ribelle tre anni prima, non è la narrazione dei tempi che furono ma una realtà che si ripresenta quando la storia vacilla sin dalle fondamenta.

Meditando su ciò che ha appena visto, con maschera e tubo respiratorio, si getta nell’acqua poco profonda e attraversa la piccola laguna a nuoto. È una delle sue attività preferite, specie in Sardegna. In quel periodo nessuno degli abitanti fa il bagno, ma lui è abituato ad altre latitudini, e non perde tempo. C’è un vecchio epitaffio, inciso sulle rovine accanto al porto di Giaffa, nei pressi di Tel Aviv, che recita: «Nuoto, il mare è attorno a me, il mare è in me, e io sono il mare. In terra non ci sono e mai ci sarò. Affonderò in me stesso, nel mio proprio mare». In queste antichissime righe, c’è tutto Jünger, sospeso sulla superficie acquea di un mare cristallino, a riflettere sui sottili legami tra passato e presente, mito e storia.

Teatro di queste incursioni è il Mediterraneo, qui inteso in senso più che geografico. Agorà e labirinto, «perduto mare del Sé» (Janvs), archivio e sepolcro, corrente e destino, crepuscolo e aurora, apollineo e dionisiaco, «è una grande patria», scrive Jünger, «una dimora antica. A ogni mia nuova visita me ne accorgo con evidenza sempre maggiore; che esista anche nel cosmo, un Mediterraneo?». Se è vero, come scrive Matvejević nel suo libro già citato, che «il Mediterraneo attende da tempo una nuova grande opera sul proprio destino», quella di Jünger potrebbe esserne la bozza. Un destino osservato sulle rocce e sulle piante, abbrivio a dèi ed eroi omerici, simulacri di battaglie cosmiche che si compiono dall’aurora dei tempi. Tutto ciò è riflesso nei volti che ha modo d’incontrare, nelle calette in cui si avventura e negli insetti che osserva, con la discrezione di un entomologo professionista. Tutte maschere di una sola cosa:

«Terra sarda, rossa, amara, virile, intessuta in un tappeto di stelle, da tempi immemorabili fiorita d’intatta fioritura ogni primavera, culla primordiale. Le isole sono patria nel senso più profondo, ultime sedi terrestri prima che abbia inizio il volo nel cosmo. A esse si addice non il linguaggio, ma piuttosto un canto del destino echeggiante sul mare».

Un mare da cui si accomiaterà il primo giugno, ma solo per qualche tempo (mediterranea è anche, in senso eminente, la certezza del ritorno). Jünger prepara i bagagli, e percorre a ritroso il suo viaggio. Sulla strada verso Cagliari, s’imbatte nei bunker eretti dalla Wehrmacht durante la Seconda guerra mondiale. Forse la foresta se li inghiottirà. Difficile che invecchino bene, come invece il Forte di Michelangelo a Civitavecchia, le macchine da guerra di Leonardo o le prigioni di Piranesi… Prende il treno per Olbia. Dopo settimane di astinenza dalla modernità, compra un giornale, solo per vedere quanto poco il mondo sia cambiato. L’argomento à la page è la bomba atomica, il tono è «come sempre noioso, irritante, indecoroso. Ci si domanda a volte a quale scopo si paghi l’onorario ai filosofi». Chissà cosa direbbe oggi, di fronte a certe querelle da bettola… Dopodiché, in nave fino a Civitavecchia, dove lo attende un treno, diretto a Nord. La linea passa da Carrara, mentre a sinistra c’è sempre il mediterraneo, muto spettatore di un dolore non ancora cicatrizzato. «Il mare è una lingua antichissima che non riesco a decifrare» scrisse il suo amico Jorge Luis Borges nel 1925 (nel saggio Navigazione, uscito ne La luna vicina).

Il congedo di Jünger dalla Sardische Heimat è solo temporaneo. Vi tornerà diverse volte, finché le condizioni di salute glielo permetteranno. Nato sotto costellazioni settentrionali, in quel lontano 1954 ha subito un fascino cui è molto difficile sottrarsi, e ora non può che rispondere periodicamente a quest’appello. «Mare! Mare! Queste parole passavano di bocca in bocca. Tutti corsero in direzione di esso… cominciarono a baciarsi gli uni cogli altri, piangendo» ci rivela Senofonte nelle Anabasi, descrivendo la reazione dei soldati greci, dopo un lungo peregrinare a terra, affacciatisi sul Mediterraneo. Furono forse le stesse parole che rimbombarono nelle orecchie del Contemplatore Solitario a bordo di quell’autobus, tra un tornante e l’altro, tra un mare e l’altro, fino a Illador, oasi di un passato martoriato e misteriosa prefigurazione di un destino a venire.

Tag: Al muro del tempo, D. H. Lawrence, Esiodo, Friedrich Nietzsche, Il contemplatore solitario, Il trattato del ribelle, Mircea Eliade, Predrag Matvejević, Quirino Principe, San Pietro, Stenio Solinas, Villasimius

Lire Bernanos aujourd’hui, c’est donc renouer avec l’idéal de la plus vieille France, celui d’une chrétienté médiévale – peut-être idéalisée – qui, dans toute sa puissance, était restée le marchepied du Royaume des Cieux. Royaume qui ne s’ouvrait qu’à ceux qui n’avaient pas tué en eux l’esprit d’enfance. Une chrétienté virile qui châtiait les usuriers et faisait miséricorde aux putains, qui couvrait la France de monastères, de vignes et de moulins. C’est à cette vieille terre de France que Bernanos songeait lorsqu’il écrivait : « Quand je serai mort, dites au doux royaume de la terre que je l’aimais plus que je n’ai jamais osé le dire ». Et cette terre est la nôtre, alors…

Lire Bernanos aujourd’hui, c’est donc renouer avec l’idéal de la plus vieille France, celui d’une chrétienté médiévale – peut-être idéalisée – qui, dans toute sa puissance, était restée le marchepied du Royaume des Cieux. Royaume qui ne s’ouvrait qu’à ceux qui n’avaient pas tué en eux l’esprit d’enfance. Une chrétienté virile qui châtiait les usuriers et faisait miséricorde aux putains, qui couvrait la France de monastères, de vignes et de moulins. C’est à cette vieille terre de France que Bernanos songeait lorsqu’il écrivait : « Quand je serai mort, dites au doux royaume de la terre que je l’aimais plus que je n’ai jamais osé le dire ». Et cette terre est la nôtre, alors…

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Bulletin célinien, n°412

Bulletin célinien, n°412

Le mannequin, la poupée, l’automate sont plus parfaits que nous :

Le mannequin, la poupée, l’automate sont plus parfaits que nous :

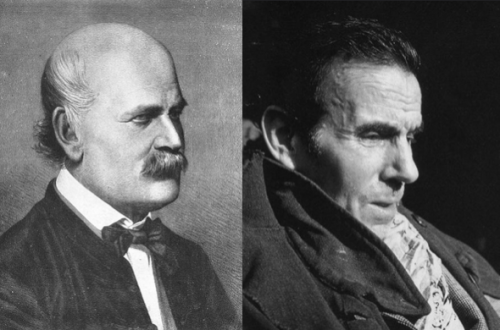

Quel est donc le génie d’un Semmelweis ? Exerçant dans une clinique où la fièvre puerpérale ravage les femmes en couche, surtout lorsque celles-ci sont tripotées par des étudiants ayant plus tôt effectué des dissections, Semmelweis comprend que cette mortalité massive est directement liée à la propagation de miasmes cadavériques dans les organes génitaux féminins. Déjà persuadé que la cause de ces décès se trouve au sein de la clinique même, son déclic survient le jour où son ami Kolletschka, souffrant d’une blessure au scalpel contractée lors d’une dissection, meurt des suites de symptômes similaires à ceux de la fièvre puerpérale.

Quel est donc le génie d’un Semmelweis ? Exerçant dans une clinique où la fièvre puerpérale ravage les femmes en couche, surtout lorsque celles-ci sont tripotées par des étudiants ayant plus tôt effectué des dissections, Semmelweis comprend que cette mortalité massive est directement liée à la propagation de miasmes cadavériques dans les organes génitaux féminins. Déjà persuadé que la cause de ces décès se trouve au sein de la clinique même, son déclic survient le jour où son ami Kolletschka, souffrant d’une blessure au scalpel contractée lors d’une dissection, meurt des suites de symptômes similaires à ceux de la fièvre puerpérale.

Se rangeant derrière l’initiateur du renouveau mitteleuropéen, le Triestin Claudio Magris, Milo Dor résume cette culture centre-européenne comme un fait rendu possible par deux facteurs : « la présence de population juive et l’emploi de la langue allemande comme moyen de communication universellement reconnu ». À l’heure du triomphe étouffant de l’anglais et de la fin de ce pénible XXème siècle — siècle qui, pour Magris, se résume dans l’affrontement entre les éléments juif et allemand —, cette culture est résolument morte. La Cacanie de Musil n’est qu’un vague souvenir et n’excite guère plus que les initiés. Stefan Zweig est adulé en raison de ses nouvelles pour femmes et son touchant exil, alors que sa nostalgie euro-habsbourgeoise est habilement passée sous silence. Berlin est sur toutes les lèvres, Vienne n’est plus rien. Anecdotique ? Non, toute la matière historique des deux derniers siècles est là : Berlin est une anomalie, elle marque le triomphe de la vulgarité belliciste des Hohenzollern sur le prestige pacificateur des Habsbourg — fait historique amorçant le début des convulsions allemandes pour Istv

Se rangeant derrière l’initiateur du renouveau mitteleuropéen, le Triestin Claudio Magris, Milo Dor résume cette culture centre-européenne comme un fait rendu possible par deux facteurs : « la présence de population juive et l’emploi de la langue allemande comme moyen de communication universellement reconnu ». À l’heure du triomphe étouffant de l’anglais et de la fin de ce pénible XXème siècle — siècle qui, pour Magris, se résume dans l’affrontement entre les éléments juif et allemand —, cette culture est résolument morte. La Cacanie de Musil n’est qu’un vague souvenir et n’excite guère plus que les initiés. Stefan Zweig est adulé en raison de ses nouvelles pour femmes et son touchant exil, alors que sa nostalgie euro-habsbourgeoise est habilement passée sous silence. Berlin est sur toutes les lèvres, Vienne n’est plus rien. Anecdotique ? Non, toute la matière historique des deux derniers siècles est là : Berlin est une anomalie, elle marque le triomphe de la vulgarité belliciste des Hohenzollern sur le prestige pacificateur des Habsbourg — fait historique amorçant le début des convulsions allemandes pour Istv

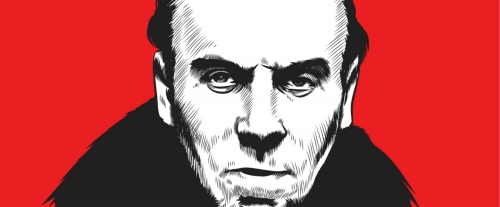

Alla fine degli anni Quaranta, insomma, il futuro premio Goethe è in catene: ma Jünger, il reietto, si metamorfosa, cambia pelle, assumendosi il compito di fari aristocratico del dolore, come dirà pochissimi anni più tardi. È la carne degli sconfitti a reclamare attenzione in queste luminose pagine, che la sapienza europea non potrà a lungo ignorare. Un grido che di certo risulterà sgradito a certe anime belle, ma che fa delle sue parole uno dei canti più intensi del secolo XX.

Alla fine degli anni Quaranta, insomma, il futuro premio Goethe è in catene: ma Jünger, il reietto, si metamorfosa, cambia pelle, assumendosi il compito di fari aristocratico del dolore, come dirà pochissimi anni più tardi. È la carne degli sconfitti a reclamare attenzione in queste luminose pagine, che la sapienza europea non potrà a lungo ignorare. Un grido che di certo risulterà sgradito a certe anime belle, ma che fa delle sue parole uno dei canti più intensi del secolo XX.

Come già detto, il futuro Premio Goethe approda a Carloforte nel 1955, ma il suo primo contatto con la Sardegna risale all’anno precedente. Il diario del suo mese trascorso nel piccolo villaggio di Villasimius è uscito in varie edizioni, con il titolo Presso la torre saracena. Tradotto – magistralmente – da Quirino Principe, verrà inserito insieme agli altri “scritti sardi” ne Il contemplatore solitario (Guanda, 2000) e in Terra sarda (Il Maestrale, 1999).

Come già detto, il futuro Premio Goethe approda a Carloforte nel 1955, ma il suo primo contatto con la Sardegna risale all’anno precedente. Il diario del suo mese trascorso nel piccolo villaggio di Villasimius è uscito in varie edizioni, con il titolo Presso la torre saracena. Tradotto – magistralmente – da Quirino Principe, verrà inserito insieme agli altri “scritti sardi” ne Il contemplatore solitario (Guanda, 2000) e in Terra sarda (Il Maestrale, 1999).

C’est « Paris et le désert français » cent ans avant Jean-François Gravier ; mais pour être honnête Rousseau avait déjà méprisé l’usage inconvenant de l’hyper-capitale Paris pour la France.

C’est « Paris et le désert français » cent ans avant Jean-François Gravier ; mais pour être honnête Rousseau avait déjà méprisé l’usage inconvenant de l’hyper-capitale Paris pour la France.

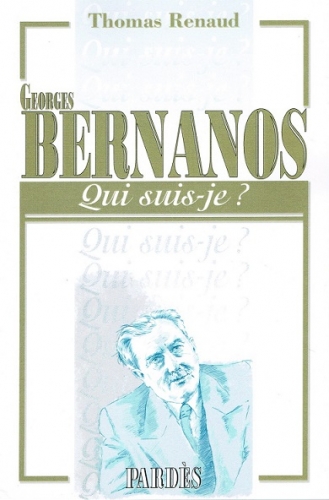

Soixante-dix ans après sa mort, Georges Bernanos fait toujours l’objet d’interprétations intéressées. Certaines se focalisent sur le romancier et ignorent l’essayiste et le polémiste. D’autres, au contraire, valorisent le pamphlétaire et écartent son œuvre romanesque. Thomas Renaud a le mérite de montrer que ces deux facettes forment un seul ensemble de manière irrécupérable. « Complexe et torturé, dans la mesure où il n’a jamais voulu faire taire les appels de son âme, Bernanos a porté avec lui les violents paradoxes de la nature humaine, sans que ne soient jamais trahies ses plus profondes convictions. Catholique, royaliste, anti-démocrate, anti-clérical et anti-moderne, ennemi des bourgeois et partisan des petits jusqu’à la mauvaise foi, il demeura tout cela à la fois, depuis son adolescence jusqu’à son dernier souffle. D’un côté, les “ droitards ” se fourvoient en dénonçant en lui un traître passé à gauche, de l’autre, certains néo-bernanosiens se trompent également en occultant l’admiratif disciple de Drumont, le militant de rue de l’Action française, le solide soldat des tranchées et le chrétien intégral (p. 114). »

Soixante-dix ans après sa mort, Georges Bernanos fait toujours l’objet d’interprétations intéressées. Certaines se focalisent sur le romancier et ignorent l’essayiste et le polémiste. D’autres, au contraire, valorisent le pamphlétaire et écartent son œuvre romanesque. Thomas Renaud a le mérite de montrer que ces deux facettes forment un seul ensemble de manière irrécupérable. « Complexe et torturé, dans la mesure où il n’a jamais voulu faire taire les appels de son âme, Bernanos a porté avec lui les violents paradoxes de la nature humaine, sans que ne soient jamais trahies ses plus profondes convictions. Catholique, royaliste, anti-démocrate, anti-clérical et anti-moderne, ennemi des bourgeois et partisan des petits jusqu’à la mauvaise foi, il demeura tout cela à la fois, depuis son adolescence jusqu’à son dernier souffle. D’un côté, les “ droitards ” se fourvoient en dénonçant en lui un traître passé à gauche, de l’autre, certains néo-bernanosiens se trompent également en occultant l’admiratif disciple de Drumont, le militant de rue de l’Action française, le solide soldat des tranchées et le chrétien intégral (p. 114). » Du fait des impératifs du volume, l’auteur s’intéresse à la vie de Georges Bernanos, quitte à reléguer au second plan sa vision politique. Elle demeure cependant bien présente pour expliquer les prises de position virulentes d’un fervent chrétien inquiet de l’avenir de la foi et des fidèles. Attention au contre-sens ! Bernanos se moque du sort des États modernes. Ce catholique a compris que la modernité est en perdition, elle est la perdition et correspond à la Chute de l’Homme adamique. D’où la démarche de son biographe. « Il nous semblait préférable de présenter aux lecteurs qui le connaissaient mal un Bernanos vivant, sans l’habituelle hémiplégie intellectuelle des lecteurs “ de droite ” et “ de gauche ”. Sébastien Lapaque a fait beaucoup pour rendre ce Bernanos “ en bloc ” que trop de critiques avaient divisé. Cette petite biographie doit ouvrir largement sur l’œuvre et permettre une belle amitié avec un auteur particulièrement attachant, qui n’a jamais souhaité jouer la comédie (1). »

Du fait des impératifs du volume, l’auteur s’intéresse à la vie de Georges Bernanos, quitte à reléguer au second plan sa vision politique. Elle demeure cependant bien présente pour expliquer les prises de position virulentes d’un fervent chrétien inquiet de l’avenir de la foi et des fidèles. Attention au contre-sens ! Bernanos se moque du sort des États modernes. Ce catholique a compris que la modernité est en perdition, elle est la perdition et correspond à la Chute de l’Homme adamique. D’où la démarche de son biographe. « Il nous semblait préférable de présenter aux lecteurs qui le connaissaient mal un Bernanos vivant, sans l’habituelle hémiplégie intellectuelle des lecteurs “ de droite ” et “ de gauche ”. Sébastien Lapaque a fait beaucoup pour rendre ce Bernanos “ en bloc ” que trop de critiques avaient divisé. Cette petite biographie doit ouvrir largement sur l’œuvre et permettre une belle amitié avec un auteur particulièrement attachant, qui n’a jamais souhaité jouer la comédie (1). »

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

Naipaul had a unique background. He was of Hindu Indian origins and grew up in the British Empire’s West Indian colony of Trinidad and Tobago. Naipaul wrote darkly of his region of birth, stating, “History is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was created in the West Indies.”

Naipaul had a unique background. He was of Hindu Indian origins and grew up in the British Empire’s West Indian colony of Trinidad and Tobago. Naipaul wrote darkly of his region of birth, stating, “History is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was created in the West Indies.” The arrival of Islam to the Sind is the disaster which keeps on giving.

The arrival of Islam to the Sind is the disaster which keeps on giving.

The second and obvious respect in which Pound was pagan was that he accepted as valid indigenous images, names, and myths, by which Deity has revealed Itself to the Europeans. He claimed that the only safe guides in religion were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the writings of Confucius.

The second and obvious respect in which Pound was pagan was that he accepted as valid indigenous images, names, and myths, by which Deity has revealed Itself to the Europeans. He claimed that the only safe guides in religion were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the writings of Confucius.

One recognizes a person that one actually knows by sight, by who the person is, not because of the name. A person may be called by different names yet be the same person still. “Tradition inheres in the images of the Gods, and gets lost in dogmatic definitions . . . But the images of the Gods . . . move the soul to contemplation and preserve the tradition of the undivided light.”

One recognizes a person that one actually knows by sight, by who the person is, not because of the name. A person may be called by different names yet be the same person still. “Tradition inheres in the images of the Gods, and gets lost in dogmatic definitions . . . But the images of the Gods . . . move the soul to contemplation and preserve the tradition of the undivided light.”

The Kalevala was first published in 1835, but the tales therein date back to antiquity and were handed down orally. The poems were originally songs, all sung in trochaic tetrameter (now known as the “Kalevala meter”). This oral tradition began to decline after the Reformation and the suppression of paganism by the Lutheran Church. It is largely due to the efforts of collectors like Lönnrot that Finnish folklore has survived.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835, but the tales therein date back to antiquity and were handed down orally. The poems were originally songs, all sung in trochaic tetrameter (now known as the “Kalevala meter”). This oral tradition began to decline after the Reformation and the suppression of paganism by the Lutheran Church. It is largely due to the efforts of collectors like Lönnrot that Finnish folklore has survived.

Autre réflexion: si Céline est reconnu comme un écrivain important, il n’en demeure pas moins qu’il est tenu à l’écart par l’école et l’université. Hormis Voyage au bout de la nuit et, dans une moindre mesure Mort à crédit, ses romans sont absents des programmes scolaires. Quant à l’université, on doit bien constater qu’elle organise très peu de séminaires sur son œuvre et que, parmi les universitaires habilités à diriger des recherches, rares sont ceux qui acceptent de diriger un travail sur Céline. Conséquence : le nombre de thèses à lui consacrées est en nette baisse par rapport au siècle précédent. On se croirait revenu aux années où Frédéric Vitoux puis Henri Godard rencontrèrent tous deux des difficultés à trouver un directeur de thèse. Et cela ne risque pas de s’arranger dans les années à venir.

Autre réflexion: si Céline est reconnu comme un écrivain important, il n’en demeure pas moins qu’il est tenu à l’écart par l’école et l’université. Hormis Voyage au bout de la nuit et, dans une moindre mesure Mort à crédit, ses romans sont absents des programmes scolaires. Quant à l’université, on doit bien constater qu’elle organise très peu de séminaires sur son œuvre et que, parmi les universitaires habilités à diriger des recherches, rares sont ceux qui acceptent de diriger un travail sur Céline. Conséquence : le nombre de thèses à lui consacrées est en nette baisse par rapport au siècle précédent. On se croirait revenu aux années où Frédéric Vitoux puis Henri Godard rencontrèrent tous deux des difficultés à trouver un directeur de thèse. Et cela ne risque pas de s’arranger dans les années à venir.

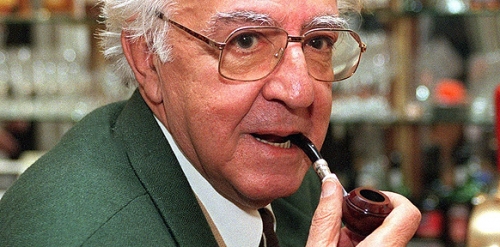

Henri Godard n’écrira plus sur Céline. Il considère qu’il a dit sur le sujet tout ce qu’il avait à dire. Il n’était que temps de lui rendre hommage et de lui exprimer notre gratitude. En publiant la transcription d’un des plus intéressants entretiens qu’il ait donnés à la presse radiophonique. Plus loin, deux céliniens de la nouvelle génération saluent avec reconnaissance leur aîné tandis que Jean-Paul Louis, avec lequel il fonda la revue L’Année Céline, explique pertinemment en quoi son travail d’éditeur dans la Pléiade est digne de tous les éloges.

Henri Godard n’écrira plus sur Céline. Il considère qu’il a dit sur le sujet tout ce qu’il avait à dire. Il n’était que temps de lui rendre hommage et de lui exprimer notre gratitude. En publiant la transcription d’un des plus intéressants entretiens qu’il ait donnés à la presse radiophonique. Plus loin, deux céliniens de la nouvelle génération saluent avec reconnaissance leur aîné tandis que Jean-Paul Louis, avec lequel il fonda la revue L’Année Céline, explique pertinemment en quoi son travail d’éditeur dans la Pléiade est digne de tous les éloges.

C’est une sorte de miracle: à la fin de l’année passée, Rémi Ferland, l’éditeur des Écrits polémiques, découvre au marché aux puces de Québec quelques exemplaires d’une brochure à la couverture bleu ciel: L.-F. Céline / Lettres familières. Au sommaire: trente-deux lettres, soit onze à sa fille Colette et vingt et une à Édith Follet, sa deuxième épouse. Toutes écrites après la guerre : les premières du Danemark, les suivantes de Meudon. La composition, réalisée à l’aide d’une machine à écrire électrique, est rudimentaire. Guère d’indication si ce n’est une mention anonyme d’éditeur : « Petits papiers / près Halifax / chez la Belle Hortense (sur le port) ». Qui a donc pu publier outre-Atlantique ce modeste recueil recelant de vrais trésors ? Le mystère est entier… Toujours est-il que Ferland a eu la bonne idée de rééditer cette correspondance sous la forme d’une élégante plaquette avec, cette fois, comme titre Lettres à Édith et à Colette (voir en dernière page). Dans sa biographie, François Gibault nous en avait déjà révélé quelques unes et il n’avait certes pas eu tort d’écrire que beaucoup de celles adressées à Édith « sont de véritables lettres d’amour ». En témoigne notamment cette lettre qui commence ainsi : « Que tu le veuilles ou non tu seras mon Édith chérie jusqu’à la mort et au-delà ! » et où percent, comme dans bien d’autres, le remords et les regrets: « Mon Édith chérie encore bien pardon je suis bien marri et j’ai bien souffert je t’assure et je suis bien malheureux de penser à ma sottise. » C’est assurément un Céline bien différent de celui que l’on nous dépeint aujourd’hui qui apparaît dans cette correspondance. Un être tout en sensibilité, d’une grande finesse et maniant un humour subtil, comme dans cette lettre où il se plaît à pasticher Mme de Sévigné : « Ma très chère, ma mie, mon cœur, je vais vous narrer une nouvelle, dont tout Versailles est bouleversé, le roi en a tenu Conseil de n’en savoir autant, voici en mille mots, non en dix ! ce qu’il faut que vous gardiez secret… » Et d’enchaîner avec cette observation prosaïque : « Votre plante bretonne, fougère d’eau, a été dépotée, et mise en terre, parfaitement, et paraît s’en trouver très bien… ne le dites à âme qui soit ! La pluie aidant vous la retrouverez géante. » Les lettres à sa fille, écrites en exil, ne sont pas moins émouvantes. L’une d’entre elles se conclut ainsi : « Oh pas de cadeaux ! pas d’envois ! Je les laisse à la douane ! Des baisers ! Des baisers ! C’est tout ! Des paroles d’espoir aussi bien que j’en tienne vraiment une immense provision en stock ! à l’écœurement ! (…) Toute mon affection à tes enfants, à toi. Ton papa. Louis. » Certains n’ont pas compris que Céline, fuyant de nouvelles affections car trop émotif, n’ait pas souhaité rencontrer ses petits-enfants à Meudon. Quant à Colette, on sait que sur le conseil de son avocat, elle renonça à l’héritage de son père. Celui qu’il eût fallu conserver précieusement c’est la correspondance qu’elle reçut de lui lorsqu’elle était enfant. Et Édith, les très nombreuses lettres qu’elle eut de Louis Destouches avant leur mariage. …Hélas !

C’est une sorte de miracle: à la fin de l’année passée, Rémi Ferland, l’éditeur des Écrits polémiques, découvre au marché aux puces de Québec quelques exemplaires d’une brochure à la couverture bleu ciel: L.-F. Céline / Lettres familières. Au sommaire: trente-deux lettres, soit onze à sa fille Colette et vingt et une à Édith Follet, sa deuxième épouse. Toutes écrites après la guerre : les premières du Danemark, les suivantes de Meudon. La composition, réalisée à l’aide d’une machine à écrire électrique, est rudimentaire. Guère d’indication si ce n’est une mention anonyme d’éditeur : « Petits papiers / près Halifax / chez la Belle Hortense (sur le port) ». Qui a donc pu publier outre-Atlantique ce modeste recueil recelant de vrais trésors ? Le mystère est entier… Toujours est-il que Ferland a eu la bonne idée de rééditer cette correspondance sous la forme d’une élégante plaquette avec, cette fois, comme titre Lettres à Édith et à Colette (voir en dernière page). Dans sa biographie, François Gibault nous en avait déjà révélé quelques unes et il n’avait certes pas eu tort d’écrire que beaucoup de celles adressées à Édith « sont de véritables lettres d’amour ». En témoigne notamment cette lettre qui commence ainsi : « Que tu le veuilles ou non tu seras mon Édith chérie jusqu’à la mort et au-delà ! » et où percent, comme dans bien d’autres, le remords et les regrets: « Mon Édith chérie encore bien pardon je suis bien marri et j’ai bien souffert je t’assure et je suis bien malheureux de penser à ma sottise. » C’est assurément un Céline bien différent de celui que l’on nous dépeint aujourd’hui qui apparaît dans cette correspondance. Un être tout en sensibilité, d’une grande finesse et maniant un humour subtil, comme dans cette lettre où il se plaît à pasticher Mme de Sévigné : « Ma très chère, ma mie, mon cœur, je vais vous narrer une nouvelle, dont tout Versailles est bouleversé, le roi en a tenu Conseil de n’en savoir autant, voici en mille mots, non en dix ! ce qu’il faut que vous gardiez secret… » Et d’enchaîner avec cette observation prosaïque : « Votre plante bretonne, fougère d’eau, a été dépotée, et mise en terre, parfaitement, et paraît s’en trouver très bien… ne le dites à âme qui soit ! La pluie aidant vous la retrouverez géante. » Les lettres à sa fille, écrites en exil, ne sont pas moins émouvantes. L’une d’entre elles se conclut ainsi : « Oh pas de cadeaux ! pas d’envois ! Je les laisse à la douane ! Des baisers ! Des baisers ! C’est tout ! Des paroles d’espoir aussi bien que j’en tienne vraiment une immense provision en stock ! à l’écœurement ! (…) Toute mon affection à tes enfants, à toi. Ton papa. Louis. » Certains n’ont pas compris que Céline, fuyant de nouvelles affections car trop émotif, n’ait pas souhaité rencontrer ses petits-enfants à Meudon. Quant à Colette, on sait que sur le conseil de son avocat, elle renonça à l’héritage de son père. Celui qu’il eût fallu conserver précieusement c’est la correspondance qu’elle reçut de lui lorsqu’elle était enfant. Et Édith, les très nombreuses lettres qu’elle eut de Louis Destouches avant leur mariage. …Hélas !