Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as.”

To subscribe to our podcasts, click here [3].

Editor’s Note:

This is an unedited transcript of an extemporaneous talk.

Well I don’t really speak to a topic, but you need something to fasten your mind on when you’re engaged in a speech. Speeches are about energy, and are about power, and about how you utilize power and how you channel it. I’m what’s called a mediumistic speaker, so I hear the voice instant by instant before I speak, and when you stand up you hear what you’re going to say a fraction of a second before it comes out of your mouth. What I’d like to talk about is Western civilization and how we can save it.

Now the crisis of the West is ongoing and everybody knows what it is. In the circumstances of the United States — I’ve only ever been here twice — the prognosis for decay is well-advanced. The people who created the United States are on the defensive: they’re on the defensive psychologically, and emotionally, and linguistically, and culturally. People are comfortable, at least those that are, and a lot hit by recession but everyone is worried about what the future will hold. Demographically, the people in this room could well be a minority in 40 years, maybe less than 40 years, maybe more than 40 years, maybe it doesn’t matter if it’s 40 years or 44 or 64 or 35.

What matters is that you’ve become a minority now. You’ve become a minority mentally, because these things happen to people mentally and psycho-spiritually before they have a physical impact. I think people are preparing to be a minority now, long before it happens. I was well aware that President Bill Clinton was once asked about his commitment to political correctness, and he said whites NEED political correctness. He said White Europeans, White Americans need it because they’re going to be a minority relatively soon, and you need to play all of those vanguard games whereby you play off each group against every other group, you make sure that your protest is in early whenever you’re insulted, or you feel there’s the prospect that you might be insulted

And an insult in this trajectory, in this terrain can mean anything. It can mean the denial of future prospect that you might have expected to own and honor. It can be the denial of something which is your right as you perceive it. Your right to dominate the cultural space here in the United States. That the United States is a post-European society. That all of its architecture — Judeo-Christian and otherwise — seems to have the impress of old Europe upon it. I speak as a European obviously, who doesn’t know the United States that well. But everything that’s glorious about the United States is largely created by the people in this room, and those to whom they relate.

Now, the problem that we’re finding is that people are giving away the inheritance that they brought up. It’s as if you have a family business, and you’ve inherited it from a grandfather, and you inherit it from a father, and you have this patriarchal chain of hard work and understanding and excellence and fulfillment, and it comes down to you through the generational sort of structures of the past — and you decided to give it away. You decided to squander it.

It’s very reminiscent of the aristocratic families in Europe: in the era before the Great War, there were big blowouts in aristocracy where people would gamble away their entire fortune, because they were bored. Because they were bored with the Third Republic’s lifestyle, in French terms, in Francophone terms, of endless summers in the sun where people were pining for the destruction which Europeans would wreak on themselves in the Great War, the War that was to end all wars: a war of such manifold destructiveness that people didn’t think there would be another one, and yet within a generation there was another one that was even more destructive.

And that war is the crucial event of the last century, because everything that exists now is a rebounded correction, as it’s perceived, of that struggle and what occurred in it. Even in the United States, it’s almost as if we as a group won that war and lost that war simultaneously, irrespective of what side our forebears fought on. In the United States you fought against Nazi Germany, you fought against Fascist Italy, you fought against Imperial Japan in the Pacific theater, and yet in a strange way you’re the losers of that war. You’ve turned into the apostates of that war, retrospectively, and you’ve partly done it to yourselves, as all continental European people and post-European people have all over the world. That war has been wrenched out of history, and is used as an ideological totem in relation to everything that occurs.

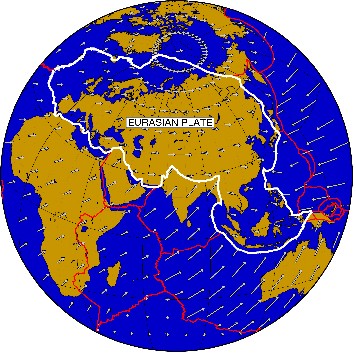

Whether or not the next 18 months or the next six months we’re going to see an attack on Iran, and the Islamic Republic of Iran, is in its own way an extension of post-1945 events. In all sorts of ways, the attack in Iraq which occurred a couple of years ago had as much to do in many people’s minds with the symmetries and the re-symmetries, of the 1939 through ’45 conflicts and everything that resulted from it, then it had anything to do with the dictator in the Iraqi desert. He was a Sunni nationalist, and he held the Kurds down in the North and the Shia down in the South, and America invaded — you remember all this? – America invaded in order to remake the world safe for democracy!

There’s no democracy in Iraq now. All that’s happened is the Sunnis have lost power and the Shias have come up, and the great new hatred, which is Iran, dominates post-war Iraq. America launched a war that cost $2 trillion in order to bring to power Iranian sponsorship and Iranian surrogates inside Iraq. So you have the odd situation now that Iran manifests power through conquered Iraq, conquered under American guns and aegis, with a bit of support from Britain in the South, where the Shia and oil are, and that power that Shia arc of power runs through Iraq: to Lebanon and the Israeli border.

And you’ll find that all of these disputes are intimately connected with the society that was created in 1948 in Israel, and which didn’t exist before. And the need to keep that society safe, the need to watch out for it, the need to prize open this prospect of villainy against it, the need to go to war –conceptually and actually — anyone against anyone who might threaten it in the future, nevermind in the present.

This war, if it ever were to occur with Iran, has been looming for many years. Many years. Ahmadinejad’s speech has almost nothing to do with the Iranian desire to destroy Israel, per se, although you could argue that an extraordinarily foolish speech in many respects. But all he said in Farsi was that the society that was created falsely, and to the detriment of the Palestinians, should cease to exist within world history. Which is a pretty nebulous and “student-fist-in-the-air” sort of speech, but it’s been seized upon to deny the Iranians the prospect of nuclear weapons and to enable the West, through the United States, in yet more warfare: more warfare for peace.

I remember Harry Elmer Barnes once edited a compilation in book form, called Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace. And since 1945, we’ve had war after war: confined to the zero-sum game of the Cold War and now extending beyond it — whereby all of these wars were are fought allegedly for us, allegedly for our betterment, allegedly for our safety, allegedly for our security, and always on the basis of our patriotism.

The bulk of patriotic people from the Right would regard what I’m saying as unpatriotic, because in a Sarah Palin sort of a way, they believe that once should stick up for the West — and our allies — against perceived enemies. Many of these enemies may not be friends of ours, but they are not enemies in the real sense. The enemies that we face here in the West, here in California, are internal. They’re internal to our own societies, they’re even internal to our own minds.

The greatest enemy that we have — to slightly adapt Roosevelt’s slogan about fear, that there’s nothing to be afraid of except fear itself — the greatest enemy we have is raised in our own mind. The grammar of self-intolerance is what we have imposed and allowed others to impose upon us. Political correctness is a white European grammar, which we’ve been taught, and we’ve stumbled through the early phases of, and yet we’ve learned this grammar and the methodology that lies behind it very well.

And we’ve learned it to such a degree that we can’t have an incorrect thought now, without a spasm of guilt that associates with it and goes along with it. Every time we think of a self-affirmative statement, it’s undercut immediately by the idea that there’s something wrong, or something queasy, or something quasi-genocidal, or something not quite right, or something morally ill about us if we have that thought. And this extends out beyond racial and ethnic questions to all other questions. To questions of gender, to questions of group identity and belonging, to questions of cultural affirmation, to questions of history.

Think about what it will be like when White Americans are 10% of the population of the United States — or 12% — 15% — or even 25%. Political correctness will not save you from the marginalization of your history and traditions, which will occur because it’s not much fun being a minority. Which is why all minorities seek through their vanguards to take majorities down. And they seem to take them down physically, conceptually, actually, legally, philosophically, and in other ways. And they form alliances with like-minded groups that wish to do to majorities what minorities feel that they ought to, because it’s a question of survival. Everyone’s interested in surviving, and even getting along with each other in a relatively quiescent and “PC” way is just another way of surviving. Maybe in the current circumstances it’s the only way in which multiple group-based societies can survive.

The Bill Clinton metaphysic is that everyone should mind their own business, and everyone should get along with each other. But it denies the crucial harbinger of identity, which is the heart of all existence and becoming – in Nietzschean terms, or in neopagan terms. All real identity is underpinned by what existed before you. The societies that are being created are tabula rasa societies, where you’ve got essentially a blank piece of paper, and what an American is is written upon this piece of paper, the way you ask a child to do a diagram or an image and they do a face with a smile. And that’s your new American: your new American is straight off the boat, he’s a face with a smile to two dots for the eyes.

Where is the history of what it means to be an American? Where is the historical trajectory which relates to what you are now and to what you have achieved? And if that tabula rasa is such that everything that you have ever achieved in the past is smoothed-down and removed, what will it mean to be an American? What will it mean to be an American – a de-hyphenated American, deconstructed to the degree that [hypenation] doesn’t even occur – because that is all that will exist in the future. “Americans” will be those that wish to be American.

Osama bin Laden and the Al-Qaeda network once did a poll in accordance with their own resources, and a third of the people who live in the Third World would like to come and live in the United States. That’s a third of the global population outside Europe, outside Japan, outside developed East Asia, outside the new Bourgeois India — 200 million out of the billion on the subcontinent who have raised themselves up to a middle-class standard of life and wish to stay on the subcontinent — but a third of those that are outside of those Bourgeois remits want to come here. And when they say “the United States,” they mean “the West.” They mean “Western Europe,” “Northern Europe,” “Southern Europe,” and the new Eastern Europe.

The new Eastern Europe is rather really interesting and will have a lot to say about the future of European man in the next century or so. Eastern Europe was preserved by communism from the decadence of the liberalism which has semi-destroyed Western Europe (and points to the west of that.) Communism was a strange non-exultation. Communism was a strange doctrine, because it preserved under permafrost many of the characteristic social chapters of what it means to be a European. Communism was pretty hellish to live under, particularly materially, and it was almost always the most deformed, the most warped, and the most degraded parts of the society that had been put in charge of you.

I remember someone I know was imprisoned in East Germany in a Stasi prison for putting a slogan on Lenin’s finger. Do you remember those statues with Lenin’s finger, where Lenin addresses the masses, like this? There were hundreds of them in all of the Eastern European societies. And they used to appear in mass posters in East Germany. And one of his friends – very stupidly given the society that East Germany was — put a bubble, a sort of Marvel Comics bubble, on the end of the finger. And the bubble said “Hitler was Right!” And he stepped back to observe — this was his Japanese cousin, and they were on a holiday in East Germany — which is an unusual type of a holiday even then — and he stepped back to examine his handiwork, and said to his relative, “what do you think about that, Bob?” And Bob turned around and there were eight Stasi, eight Stasi — one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight — in their requisite leather jackets and trench coats, because they all had the same uniform. And he got 18 months in a Stasi prison breaking rocks and living on black bread and onions. And that Stasi prison was notorious in East Germany, in East Berlin. And that Stasi condemned him for “acts contrary to proletarian justice and the will of the Socialist Republic.” He was condemned for being out of kilter with the masses in history.

East Germany is now a state that no longer exists. It’s been agglomerated into Western and greater Germany. The Wall has come down, the Stasi have demobilized and are no longer evident, yet in a strange way a spirit of Marxism is abroad in the West. A spirit of Marxism is abroad in the United States, unbelievably so! The number of American Marxist-Leninists you could have gotten in a few taxis to a certain extent, and yet this element of cultural Marxism is abroad in the United States, as it is in Western Europe, as it is in Northern and to a certain extent Southern Europe, as it is much less evidently so in post-Communist Eastern Europe, where there’s been an enormous reaction against it.

It’s taken a little bit of time to examine why Marxism, of all things, has ended up culturally influential in the United States. It’s got little to do with economic theory; it’s got much more to do with self-hatred and negation. Guilt. The extending of your own mental remit into groups that don’t care for you, or that purposefully wish you ill. And it’s got a lot more to do with the architectonics of the Frankfurt school, and its ability to morph and to merge into the general Liberal currency of the last 50 years.

Since the Second World War, White Europeans have felt guilty about being themselves and have been made to feel guilty and are being encouraged to feel more guilty than they have at any other time in their history. There is no period in our history where we have faced such evident self-hatred and such evident insults upon ourselves which are harmful to the prospects of our children’s lives, and their children, and generations as yet unborn. Is this a phase that we’ve gone through, or is it something slightly more sinister and ulterior than that? These are questions which we need to analyze.

Why, here in the United States, is there such guilt about the majority identity when the United States could point to, in its own cognizance, an exemplary war record against Germany and Japan, being on the victor’s side, being on the victor’s table? And yet the guilt for alleged and prior atrocity is such that all White Americans feel ashamed about any push forward in relation to the prospect of their own identity. It’s quite shocking how, since 1960 — I was born in 1962 — the West has lost its fiber and has collapsed internally and morally in terms of its spirituality and in terms of its sense of itself.

Fifty years a blip historically; it’s a click of the fingers. And yet for fifty years we’ve see nothing but funk, nothing but a failure of nerve, nothing but a self-expiration, nothing but the degree to which the historical destiny of the European peoples has been traduced — and has been traduced by elements of themselves and their own leadership, who have accepted at face value the fact that much of what was wrong with the modern world is morally our responsibility and not that of any other group. And that if we ever dare to assert ourselves again in any meaningful way, that we are in turn co-responsible with some of the worst events of human history.

Now, let’s unpackage this a bit. Communism in the 20th century killed tens of millions. Tens of millions. When Mao met Edward Heath, who was the British prime minister, in 1972 in the Forbidden City, he said “I’m regarded as the world’s mass murderer in human history.” Of course he said this in Mandarin and this sort of thing, he had to be exhaustively translated by Foreign Office Sinologists and so on, and Edward Heath was rather shocked by this, and said “and what’s your view of this, Chairman?” – a politician’s answer, he just reflected it back upon Mao – and Mao said, after the laborious translation had intervened, “I’m rather proud of it, actually”; being the worst mass murderer in human history.

Don’t forget the Great Leap Forward, the enormous famine that devastated much of rural China and which was in fact a great leap backwards; claimed by mainstream historians to have claimed 46 million lives — 46 million lives – it’s so large that it’s that the human mind balks at it basically. Once you get beyond the body count of couple thousand, the brain falls silent and listens to these numbers and internal calculus almost in a fantastical way. But even if a scintilla of that is true, and the truth is most of the Communists atrocities and most of the worst sort of data that can be leveled against those regimes turns out to be quite true.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, the KGB figures for those that suffered under Stalin were halfway in the range between what the apologetic individuals in the West said about the regime — the sort of revisionists, if you like, of the Soviet sort — and the exterminationists in Western countries, who tended to be conservative and who tended to be religious. The actual body count was halfway in between. Whether communism killed 100 million in the 20th century is up for grabs. Whether it killed 20 million or between 20 and 100 million is up for grabs.

And yet everywhere one looks the soft Left, the Left untainted by communist atrocity, is everywhere apparent and appears to be everywhere triumphant.

The trick that the soft Left has learned is that if you disavow the hard edge of Leftist slaughter and Siberian camps and Stasi prison cells and you instead excel in the polymorphous rebellions of Herbert Marcuse and the student left of the 1960s, you can actually influence the whole soft spectrum from the moderate Right, through the Center, through the center-Left, through the general-Left/Generic-Left, through the soft Left, up to the softest accretions of the hard Left and to the moderate-hard Left. An enormous spectrum – two-thirds of the political spectrum — can be influenced by Marxist ideas shorn of their hard-edge Stalinist and Maoist filters.

No one wants to know about John-Paul Sartre now, even in France. Partly because he embraced Maoism at the end of his career. He embraced Maoism, with Simone de Beauvoir, and Gorz, and these other people right at the end of his career. He edited a Maoist paper. This was at a time when Pol Pot was wreaking extraordinary havoc in Indochina.

And yet the ideas that these people stood for: the idea that the family is a gun in the hands of the bourgeois class, the idea that humor itself is a gun in the hands of the bourgeois class, the idea that there’s something uniquely oppressive about being male, that there’s something uniquely oppressive about being a Caucasian, that there’s something uniquely oppressive about the Western historical destiny — all these ideas have been shorn of their human rights abuses in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and far Eastern Asia, and have been reflected back into the West and onto the West. To the degree that you can’t set up a student group in an American university now –unless you’re under relatively deep cover — to oppose this sort of thing because the ideas themselves are so hegemonic.

Why has this occurred? Why can’t Counter-Currents exist on American campuses? Why isn’t there a Counter-Currents group or something of a similar order at Berkeley, for example? Why is the idea that there could be such a group at Berkeley absurd, and almost risible, and produces a mild smile? Why is there? Because the physical danger that such a group would be in is largely exaggerated. It’s the moral, mental, and spiritual danger that afflicts our people and that afflicts the young and would-be radical amongst our people, that is the thing to look to.

Why has this occurred? It’s occurred because the radical Left with a culturally Marxian agenda, scorned by the Stalinist hard-line that they were quick to repudiate, marched through the institutions in the United States and elsewhere from the cultural and social revolution of the 1960s and has marched through those institutions for 50-odd years to such a degree that the whole of the media – mainstream — the whole of mainstream politicking outside of the Rightist and Libertarian allowed areas of dissent in the Republican Party and their European equivalents are controlled by nexus of ideas and interconnected thought processes which determine moral valency and morality.

Everyone in this room is regarded as immoral by the ruling dispensation in the United States, and that’s very important, because it prevents people from identifying with ideas which are, quite transparently, in their own interest. If people think an idea is immoral they will shun you, particularly in an era of media exposure. The idea that identifying with yourself and with your own past is somehow immoral is one of the chief factors whereby the identity of post-European people in the United States has been turned: turned back upon themselves, turned back in a vise-like constriction where it can be used to destroy people and disarm them. Because if you’ve disarmed yourself before the struggle begins, you’re easy meat and easy prey for what’s coming. And the future in America is darker than the past. Unless there is a desire amongst people of European ancestry to step outside of the vortex, the zone of chaos which they have allowed to be created for themselves over the last 50 years.

If people think that the circumstances of American life are ill-disposed to your future identity now, what’s it going to be like in 50 years? What’s it going to be like in 150 years? 150 years White Americans could be maybe 20% of the population. This is the future that faces you. And your culture will be disprivileged. Forget political correctness. Political correctness works when minorities aggregate together in a vanguard way. It doesn’t work when majorities fall and stagger into minority status and then look around for allies now that they are themselves a minority in the hope that somehow they will achieve fairness and equity because these things are not about fairness and equity. They are about who can set the standard and the tone for the cultural domination of a civic space. And if it’s not the White identity in the United States — if it’s not post-Europeanism in the USA — it will be other forms of identity. Some of them fractured, broken-down, mixed, and otherwise marginal.

To European eyes the Obama Presidency is the signification of America’s decline. You have a situation where it used to be only B-listed Hollywood films that would show a powerful Black executive President ruling in the Oval Office. Almost a psychic preparation for the real thing. And now the real thing has occurred. With the Obama Presidency, you see the future the United States writ large. And from an external point of view, it will be difficult to unseat Obama because the Republicans are doing all his work for him, it seems at the present time, and I speak as someone who obviously isn’t an American.

The Obama presidency epitomizes the willed decline of majority instinct in the society because if you don’t feel it’s at all offensive that somebody that does not relate to the majority — axioms, forms of entitlement, forms of belief, and historical precedent here in the United States — is actually President of your Union, is President of your society, is your Commander-in-Chief; if the Israeli planes need to be refueled over the Persian Gulf when they attack Iran at some time in the next year to two years to six months, Obama will give the order for that to occur. And he will do so in the name of everyone in this room; everyone beyond this room. And he will do so because he still speaks as the most powerful man in the world.

So the most powerful Western country is now led by a non-Westerner. Something which would’ve been unthinkable in the 1960s, I would imagine; unthinkable in the 1970s, but is now evidently thinkable and thinkable to such a degree that I think a lot of the anger about it which is manifested in Libertarian currents like the Tea Party movement, seems to have evaporated. I speak as an outsider obviously, but it seemed to me that halfway through the Obama presidency there was a mild cultural insurgency against his regime which found a way to channel itself so that it didn’t mention racial questions. And that’s what the Tea Party movement and Libertarianism was about.

And that’s what Libertarianism is. Libertarianism is the allowed Right wing for people who wish to make Ron Paul-esque points but can’t go the whole distance, and in many ways can’t go the whole distance under the present dispensation because many people feel constrained about who they know, and who they’re married to, and who did what their job is, in relation to how explicit they can be in terms of how they reject the current American and European power structures.

Our people are used to being in charge. That’s why they find it so psychologically and emotionally forbidding when they’re no longer in charge. That’s why they feel so bereft in contemporary Western societies, because to fall from a majority and a purpose and position of power, to a more desiccated and a more jaundiced view of oneself and one’s own capabilities, is quite a wrench.

Everything that I’ve said about the United States could’ve been said about my own country if one goes back 50 or 60 years. There was a time early in the 20th century when you could argue Britain was most powerful society in the world. Britain is now a shadow of a shadow of its former state. It is in a precarious and culturally quite a terrible situation. It has decided in its near-death throes to yoke its star to the contemporary United States. Everything about modern Britain is Americana taken to a different level and repositioned in Western Europe. Almost all of our models, speaking as a Briton, are American now. Almost all of our wars are American-led. We always tag along as a sort of surrogate or executive vessel.

All of our politically-correct trajectory has in some ways come retrospectively from the radical Left fringes of the 1960s, and has been filtered by both an indigenous, and a transatlantic, Left. And we’ve allowed all this to occur to ourselves because we have been inured to the prospect of suffering.

And we’ve been inured to it through plenty. There are many who believe that while Western people suffer no economic distress and while the fridge is full, and while there are several sort of four-wheel-drive vehicles in the yard outside, people will never resort to an anti-regime attitude and their default position will always be one of resignation in relation to what is coming. Particularly when they consider that they can negotiate their way out of what is occurring. The problem is that what may well occur in the future will be nonnegotiable, particularly when it hits.

There are those who believe that the white South African Boers or Afrikaners reposition themselves within their own society so as to have a sort of whites-only republic or an area of the country which is theirs. I think that’s an important yardstick that you put out there as a metaphorization. But my private view is more pessimistic than that. I feel that unless you can actually so soak a proportion or a quadrant of the union with yourself that to spit away from it at some unforeseeable time means that you’ve got a totally post-European enclave. I feel such things, such games are not really worth the candle because when you give up the control of a state for duration — particularly the control of the most powerful republic the world has ever seen — you’re partly doomed when you’ve done that. My view is you never restyle from the desire to be the governing echelon of one of the world’s most powerful societies.

It is true that the United States is in a radical — and from a European perspective, terminal — decline. Partly because the European empires of the past: British, French, German, Dutch, Spanish, German and elsewhere, can see the writing on the wall. All of the precedents: of indebtedness, of being beholden to China in relation to the manipulation of the debt and its economic management, by having an ally such as Israel that wags the tail of the dog to such a degree that it’s almost in charge of the Middle Eastern policy of the United States of America – you could say Cuban-Americans are in charge of America’s Cuban policy, yet the policy towards that tiny and redundant Stalinist island is not as important, by any stretch of the imagination, as the policy towards Israel in the Middle East is in relation to the crucible of world expectation.

The CIA don’t get many things right, but they predict a war in the Middle East involving nuclear weapons in the next 25 years, because the depth of the hatred on both sides is so great. No one can stop other countries getting nuclear weapons; this is the irony of the present Iranian situation. Thirty-four other countries are developing, thirty-four other countries are developing nuclear weapons as we speak, including Brazil, and South Africa, and Argentina, and Saudi Arabia, and so on. And there’s many societies, such as South Korea and Japan and modern Germany, that could develop these weapons overnight if they chose to do so.

The point of an increasingly destructive and an increasingly bifurcated and divided world is to reconstitute yourself in such a way as you are least threatened by its exigencies. If you are least threatened by them you have the biggest possibility of reviving your own culture. I regard the cultural health of the civilization to be the elixir of its development and its authorization, its preferment in its sense of itself. Without that cultural overhang and extension, you cannot be worthy of the inheritance of European identity. If you allow your culture to be transparently disfigured by forces which are external and internal to it, and which you could have controlled in previous incarnations, you will witness your own death knell. And you will witness it in your own lifetime.

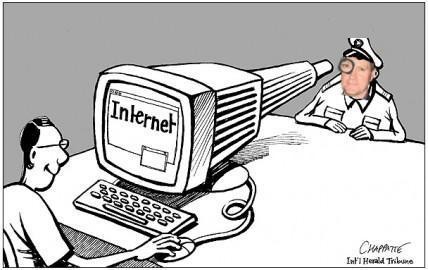

But this is not necessarily to harp totally upon the negative, this speech of mine. Because I regard initiatives like Counter-Currents as very important. Counter-Currents is, to my estimation, a sort of right-wing university. A sort of free access right-wing University on the Internet, a radical Right-wing University. The whole point now is that higher education has locked off the Right end of the spectrum. You can learn about conservative ideas, you can learn about Liberal ideas, you can learn about Socialist ideas, you can learn about Marxist ideas in the University context; you can learn about all forms of pan-religiosity and so forth.

Bbut you can’t learn about radical Right-wing ideas in the University context unless it’s adversarial, unless you’re deconstructive, unless you’re against these ideas in a prior way. “I’m writing a thesis at the moment,” somebody would say, “about the far-Right in the United States.” But the premise for such a remark if they were talking to a fellow university lecturer, would be “I’m writing it from an adversarial point of view.” Because nobody can ever say that they were writing it from a friendly, or an effective, or non-adversarial point of view; because it’s a viewpoint to which you must must be opposed, because all right-minded people are allegedly opposed to it.

The truth is most right-minded people are only opposed to it because they believe that they ought to be. They believe that their own niceness and their sense of themselves and their sense of what their neighbors think of them is tied up with the reflexivity of reverse negation, as I call it. “We will not align ourselves with these haters,” “We will not align ourselves with these people who are depicted by the media in such a bad way,” “We will not align ourselves with people who could be held to be in some ways morally responsible for events in the past that we wish to have nothing to do with.” This is the majority sentiment.

Only when you can break through that permafrost — only when you can get into the majority sentiment and begin to turn it around — will there be a change here in the United States or elsewhere. One of the things that can force a change is the impact of more and more transmigration and migrations of peoples. All peoples indeed, which the future holds open for us. The degree to which the world is now shrinking, and although there are now more Caucasians than ever before, our proportion of overall mankind is going progressively downwards as we have one to two children per family and we do not replicate ourselves to the degree that other peoples are doing elsewhere around the world.

But it’s not necessarily something about which we should be completely negative. The prospect of negativity is so great with our people and with our predilections to look upon the worst side of things particularly when our back is against the wall, that we forget the advantages that we have at the present time. Technology and the creation by our group of many of the instruments of this technology is so fulsome and so extensive that we can communicate with almost everyone on Earth — and we can communicate amongst ourselves — instantaneously at the flick of a button or a switch.

Nobody who wishes to learn about Western civilization and is volitionally moving towards learning about it, cannot do so at the present time. It used to be that only a fraction of our societies could ever hold their minds anything about our past, certainly in an academic or vocational way. Now we have the prospect that vast millions of our people can access the Western tradition of the flick of a switch, and this is all to the good.

The problem is that they retain in their minds a mindset which filters out much of the excellence of the Western tradition. Because only when you realize that what we painted, what we built and what we wrote and what we self-dramatized and what we composed musically, had to do with concepts of our own strength, of our own becoming, of our own purpose of glory — only when you realize that that was the underpinning for much of what was valued, only then will you really accord value and respect to the precedence of the past. If you rip out, for the fear of being hostile to anyone else, all prospect of group identity that is based upon strength, you will end up with a very weak and very effeminate and a very fey doctrine of your own culture, and that is what is occurring at the present time.

Alex Kurtagic is a friend of mine who’s known to certain people in this room, and he wrote a very interesting article a couple of years ago about the decline of the modern face. The decline of the modern face. It was an article in physiognomy which is quite a technique of analysis in the 19th century. Have you noticed that most people when they’re photographed today wish to look as nice as possible, as reflexive as possible, as open-hearted as possible? They’re pleading to be liked. Whereas he dug up all of these photographs of missionaries from the late 19th century and Shakers from New England — remember that cult called the Shakers? — they used to have these ecstatic dances, they all died out because they were frightened of sexual intercourse — which of course will occur, because if you’re frightened of the one you will certainly meet the other. But the face of these Shakers was furious, even just to pose nicely for the camera they would look like this. They would look with a demonic intensity and ferocity and sense of themselves and sense of courageous purpose and that sort of thing.

Today you’re regarded as mentally ill if you look like that for your own portrait, aren’t you? And yet what they were doing is they were putting on a face. They were putting on the way in which they wish to be perceived by the world. It was like sitting for portrait, sitting for an oil portrait. You didn’t show your weakest or your most reflexive or your most kind-hearted side; that, if it existed, was for private use. This was a public face. And in the decline of the West’s public face you can see writ-large the decline in the spirit of ourselves which has occurred over the past last century, and which has accelerated over the last century.

People say today that men are less masculine than they used to be. That man have been emasculated by feminism. That maleness itself is so under threat that most men don’t even wish to mention the concept, certainly not in polite society. There’s nothing more fascistic than a recrudescent male, is the general idea. If you cannot even — and these are ideas that are outside of the racial box, outside of the culturally-specific area, still important ideas in relation to political correctness — but they are a softer area in which it’s possible to be more radical one would have imagined; and yet even here one sees funk and one sees decline and one sees an acceptance of that which will lead to the destruction of forms of identity which existed in the past and that need to exist in the present and the future, if there is to be a future.

To have a future people need to be aware of their past, and they need to be aware of the glory of that past. I believe there are celebrations at the present time in the United States — if celebrations is the word – about the Civil War. The Civil War is American experience of extraordinary intensity and drama, whereby the most elitist experiment ever decided upon on the North American continent was extirpated and destroyed by armed force.

Henry Miller is an unusual character in all sorts of ways, and ended up in Big Sur. Henry Miller wrote a book quite against type and against what you’d imagine his own predilections to be, called The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. He wrote it in 1942 after he had a car journey all around United States of America. In this book he makes several dissentient remarks, one of which he says the South — the old South — is to him the most beautiful part of the United States. People here around the Californian coast might not wish to hear that, but he reckoned that the old South was the only aristocratic society — based as it was upon slavery, of course — that was created here in the North Americas. And that it was an elitist society of an old European sort, the nature of which had to be extirpated if you were to have modern America.

What do you do about the Confederacy, and what do you do about the Civil War? You basically probably prefigure the Black and the female experience, you marginalize the White South, and you marginalize those who fought on behalf of racial consciousness at that time. You marginalize all those people in the North — weren’t they called Copperheads — the people in the North who sympathized with the South — a venomous snake, you see. Why is that when radical forms of White identity are dealt with in the historical tradition, they are always dealt with from a perspective of demonization?

When Haitian militants massacred the White population of Haiti, they would be considered by contemporary historiography to be more radical variations of Blackness, more radical variations of militaristic Republicanism in Haiti at that time. But they would not necessarily be condemned for what they did. There would be an attempt to evaluate and to explain and to provide extenuating circumstances within the discourse.

Why isn’t that done for the White South? Why isn’t there an attempted social experiment on the American soil perceived as one of the trajectories in White politics at that particular time? Why is the double standard of double moral jeopardy applied by the historians of our own group to more radical formulations of Caucasian identity here in the United States, or as then it was the dis-United United States? Why have people allowed a situation to emerge whereby our own historical reckoning and our own traditions of self are turned against us in such a radical way that it’s almost impossible — except by the recession to the absolute right — to defend oneself?

Let’s face it, many people do not want to come on to the Right end of the spectrum, and right at the end of that spectrum as well, in order to defend themselves. They would like to be in the middle. Most people are comfortable in the middle. They’re comfortable when they’re with their fellows, when they’re part of a crowd and feel that they’re mainstream. This is an extraordinary problem that we face: the degree to which people do not wish to stand alone. And it’s understandable that they don’t wish to stand alone, particularly at this time. We must provide them with the courage to do this, and Counter-Currents is one of the means by which people can educate themselves to defend themselves and their own honor and future prospects.

Counter-Currents is what I personally believe the best, most educative Right-wing site that I’ve come across, and it’s used by an enormous plethora of people who want information about their own past and their own future. There’s a great wealth of material on it, and it provides this tertiary education of the mind in a radical Right sensibility. I believe that this is crucial if we’re to have a future.

There are various other websites like Alternative Right and others, the Voice of Reason network, exist to furnish, in my opinion, in a more direct and concrete — and everyday and populist sense — the work that Counter-Currents does. Obviously one wants to see much more of this, and there’s no doubt that the Right has gravitated to the Internet in order to get around the censorship that exists almost everywhere else. Because these views are censored almost everywhere else.

Political correctness is a methodology and a grammar. It is designed to restrict the prospect of a thought before the thought is even enunciated. Chairman Mao had the idea of “magic words.” Magic words. “Racism” is a magic word. Use it, and people fall apart. People begin to disengage even from their own desire to defend themselves. All of the other “–isms”: sexism, disableism, classism, ageism, homophobia, islamaphobia, all the others are pale reflections, in other and slightly less crucial areas, of the original one: “racism.”

“Racism” is a term developed by Leon Trotsky in an article in the Left oppositionist journal in the Soviet Union in 1926 or 1927. It is now universalized from its dissentient communist origins — don’t forget Trotsky was on the way out of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as Stalin engineered his disposal and the disposal the Left opposition that he led — and that word has been extracted now to such a degree that it is a universal. It’s universal, it’s become a moral lexicon of engagement and disengagement. If you wish to condemn somebody in contemporary discourse, you say that they are a racist. And there’s a degree to which nobody can refute you’re saying in the present dispensation.

Only when people gain the courage and the conviction to read what is on Counter-Currents, to internalize it, and to defend their own possibilities — of development, biologically and culturally — will we see a change here in America and elsewhere. Only when people are prepared not to fall down and beg for mercy in relation to the past — or the Shoah, which is a sort of a Moloch, sort of a ceremonial device which is used in order to shame nearly all Caucasian, Aryan, and Indo-European people; it’s become a religious totem, a pseudo-religious totem, which is wheeled out and shunted around and made use of so that people fall down and beg for mercy even before they’ve opened their own mouths. They’re begging for mercy even for the prospect of opening their own mouths.

And although I’m saying nothing the people in this room don’t already know, it’s important to realize that these psychological constructs for the majority of our people are deeply crippling and deeply negative in their effects. You have a situation now where people have so loaded upon themselves the untrammeled forces of guilt and the absence of self-preservation that almost any healthy instinctual or virile capacity is beyond them, except as a reaction to a prior threat.

Only when we recover the sense of dynamism that we seem to have partly lost will we have a future: here in the United States, here in California, or in the Western World as a whole. Many other groups in this world wonder about what is happened to us; wonder what has happened to our energy. Don’t be surprised if you learn that many of the elites in foreign countries, in India and China and so on, view with bemused amazement the trajectory of the present West, the degree to which the West is so self-hating: about its own music, about its own art, about its own architecture, about its own military history — other groups in the world are amazed at this, but will seek to take advantage of it because why wouldn’t they? In the circumstances of group competition which this globe entertains, all groups are partly in competition for scarce resources against all other groups. It doesn’t have to be as merciless as all that.

But it is real, and it is extant, and it is ongoing.

Mass immigration into Britain began with the Nationality Act in 1948, which was passed by the [Clement] Attlee government. And Attlee, who was the-then Labor Prime Minister, in a landslide victory that Labor won immediately after the Second World War; said that, “if the races of the world are mixed together there will be no more war.” “If the races of the world are mixed together there will be no more war,” and he took that idea from the anti-colonial movement of the 1920s and the 1930s.

What you get instead, is you get the internalization of divisions and a bellyaching of a globalist sort inside societies instead of between them. So all that happens is the group dynamics which were Nation-State oriented and National in the past three to five centuries become internal, because human competition and the dynamics of group difference are such that they will always exist, no matter what you do. They will exist inside multiracial marriages. They will exist inside multiracial schools, they will exist inside multiracial cities, they will exist within multiethnic housing developments, and they will certainly exist within multiracial societies.

What then happens, is that each group creates a vanguard that negotiates with the other groups about how big a slice of the pie that they get. And the future politics of societies like United States is the negotiation that occurs electorally — and between elections — between the groups. Obama’s elections is a snapshot. The ball goes on, there’s a flash and he’s there for an instant because for that moment the trajectory of forces between working-class whites who vote Center-Left, between women who are more inclined to vote Center-Left than Center-Right, between Black Americans who will vote overwhelmingly for Obama — even though he is of mixed-race — because they consider him to be one of themselves; towards Latinos, who will vote for an alternative candidate from the Democratic Center-Left because they feel that they will get more of a space under the sun under such a dispensation than they would from a White Republican; together with the apathy of those who don’t vote or those who vote for other candidates; together with the trajectory at that moment of that particular electoral cycle where the Republicans were deeply depressed, where there was a deep alienation from the Jr. Bush second presidency, where there was deep malaise in the society because of the forced nature of the Iraq war, which had created convulsion and dissent within the society; and where you had an enormous economic depression which led to an economic vote for Obama, which may be partially repeated next time but was certainly evident then. That’s a snapshot. All elections are, are snapshots out of the forces that are in coalition at a particular time. And yet notice how broken down and how ethnically fractious that coalition is to be.

The prospect of White Republicans being elected — except to lower levels — probably decreases with each year of demographic change in the United States. Even the number of years Obama has been in probably changes the thing in a game-changing way to his advantage. For each year that goes on — my understanding is that America is now a third nonwhite? — essentially it’s a two-thirds/one-third society — but many Western Europeans still conceive of the United States as a White European society. There was even bemused surprise in parts of Western Europe that a non-White President had been elected. But anyone who knows the United States relatively knowledgeably, and who knows of the Kennedys’ desire to extend immigration out to the whole world, and to end the previous Europeans-only, Whites-only immigration policy which had subsisted from the 1920s, I believe. Everyone knows that realizes that the new political dispensation in the United States is contrary to — and hostile to — the indigenous majority that lives here.

Why won’t Caucasian and European people wake up to Eurocentric verities? The truth is they feel there’s always an excuse to put off the prospect of that waking up, and they are always moments — particularly of media intrusiveness — that people fear in their own lives. One of the major halting elements in the re-energization of our own people is the mass media. And it’s the control of the mass media by forces which are uniquely inimical to our future development. The mass media plays upon every segment of the masses that exist in contemporary Western society — churns them up, holds them against each other, reroutes them, messes up the agenda of everyone that has his own subtext to begin with, which it is forcing and corralling the points of energy in this society towards. Everyone can see this who watches the mass media with half a mind. Then there’s just the effect of “prole-feed” as George Orwell called it in 1984, whereby the masses are just fed a cultural industry of excess and exploitative infotainment and entertainment for their own edification, and which is an important part of the overall project.

Only when you can break through the carapace of the mass media, with all its multiple Gorgon-like heads and its Hydra-like amphitheater — only when you can break through that, using the Internet, have you a chance to embolden the necessary vanguard of our own population. All change and all radical and all revolutionary change is led by minorities. And it always occurs top-down, even though the minority may be the throwing-forwards of a focus or a group tendency that is more generic and more general.

What the Right has to do here in the United States is to build vanguards. Build as many and as purposeful ones as possible. Build them in such a way as they can’t be broken down externally and defeated internally. One of the uses of the Internet is it gets around the extraordinary backbiting and rivalry, even as it expresses it, that exists between different Right-wing individuals and groups. Because people who have a naturally decisive and quasi-authoritarian mindset always believe that they are right. This is why the Right is extraordinarily difficult to arrange and manage and bring forward. Everyone who’s ever been prominent in a Right-wing group knows it involves herding cats. And the reason for that is because of the bloody-mindedness of the maverick people who are part of these tendencies of opinion. Because you have to be bloody-minded in order to attack against that which is comfortable, and that which is “in the zone,” and that which is the managed expectation of mediocrity in decline that is going on at the present time.

The first speaker this morning, Greg Johnson, talked about decadence. And the debate as to whether it’s just a decline — whereas just as I drop this pad it falls to the floor — is it just a decline, or is it a willed decline? Is there a force which is moving this pad down to the floor, metaphorically, and keeping it there and putting a boot on it once it’s there so that’s it’s got no prospect of rising up again or a hand would creep forward and wrench it up from under the boot and raise it back up to the table. That’s a debate that one can have, but one of the things that is most important to realize is that we have our own destiny before us.

There are more of us than ever before, we are better educated than the mass than ever before, and unbelievable though that may sound. When the Boer war happened in 1899, the British did an audit of the slums in Britain, and found that a quarter of the working-class men who came forward to fight in that war were so riddled with disease, and had been so badly educated, that they were militarily of no use. And Winston Churchill said at the time that “an empire that can’t flush its own toilet isn’t much use.” One of very few radical social statements of any sort, glosses or otherwise, that Churchill ever made.

So we have enormous advantages that exist now. But we must not allow comfort and ease to sleepwalk us towards oblivion. Comfort and ease are the enemy of a decisive cultural breakthrough and a decisive implementation of the politics of the future. We have to forget the last 50 to 60 years, but remember the lessons that we should draw from it. And the lessons that we should draw from it is to believe totally in ourselves.

There’s an organization in Ireland called Sinn Fein, which in Gaelic means “ourselves alone.” And ourselves, we are the locomotive of our own destiny. We ourselves will determine what the role that European people have in the United States will be well into the next century. We must not allow other groups to determine it for us. Only when we are fit for power will we find the means to re-exercise it in our own societies. What is happening here and elsewhere in the West is the biggest test that Western people have faced for a very long period. In the past threats are always perceived as external. Another nation, another dictator, another aggressor, another imperial rivalry. In this filament of Empire, in the scrabble for Africa at the end of the 19th century, and so on.

All the enemies that we now face are internal. And the biggest enemies that we face are in our own minds. The feeling that we shouldn’t say this, shouldn’t write this, shouldn’t speak this, shouldn’t think this. These are the biggest enemies that we have. We’re too riddled with post-Christian guilt. We’re too riddled with philo-Semitism. We’re too riddled with a sense of failure, funk, and futility in relation to the European, the Classical, and the High Middle Ages passed. We’re too defensive. We’re not aggressive and assertive enough as a group.

Many White people feel bereft because the leadership that we look to, the upper Bourgeois tier — the most educated part of our own society — seem to have left the majority. The elite has gone global and sees itself as part of a global elite, and the traditional brokers of power from the university lecturer to your senior businessman, to your senior lawyer and so on, always seem to be on the side of giving the line away. And that’s because in the present day it suffices and works for you to be on the side that gives away what the past has bequeathed to you.

What will it take for the bulk of people who leave Western universities to have the middle or common denominator view of the people in this room? It will take an earthquake. But it’s not that difficult to achieve, once you get people thinking in a dissentient way. This involves very much raising the game.

In some ways we have no freedom of speech in Europe. There’s no First Amendment “right” in Europe. Everyone who speaks in Europe and wishes to avoid a prison cell has to adopt in some ways a stylized and rather abstract form of language. Anti-revisionist laws exist in most of the Western European societies. Britain is slightly unusual in not having them. But that is also rather like the old Hollywood censorship which improved a lot of filmmaking because people had become more indirect and more artistic in the way in which they treated things. It can cause people to raise their game. And I’m very much in favor of Right-wing views being put in the highest — rather than the lowest or the median-way. I’m very much in favor of appealing to new elites, and getting them to come forward rather than making populist appeals when we’re not in the right electoral cycle for that.

I was involved with a nationalist party in Britain for quite a long time. With a project that has seemed to failed and have come to nothing, even though people were elected to the European Parliament. But at the end of the day people are only changed when their cultural sensibilities shifts. And when there is a release of energy, and a release of power, and a release of self-assertion. That is the change that you seek. Electoral change and advantage results from that, rather than the other way around. Getting a few people elected will not suffice, in my view, at the present time. What will suffice is a counter-current, and a counter-cultural revolution, which reverses the processes of the 1960s.

The Marxians have marched through the institutions of the last 50 years because the doors were swinging open for them. They hardly had to kick them down because they were swinging open for them.

All the doors are shut to us. We must find ways to work our way around these doors and reconnect with the new minds of our upcoming generations.

One of the reasons that this will happen is that people in the Western world at the moment are chronically bored. There’s a boredom that has settled upon our people. You can sense it. There’s a spiritual torpor out there. And the most exciting ideas, the most threatening ideas, the most psychopathological ideas, the ideas which are beyond all other ideas, are the ideas which are in this room. They are the most dangerous ideas and therefore they have a subtle attraction to radical and dissident minds.

Don’t forget that everything which has occurred in the last 50 years was once so dissident that the people in the 1920s — those who advocate the ultra-Liberalism of today — had to meet in secret because they were frightened of revealing what their views were to the generality, and to their own families, and to work colleagues. See how the entire notion of what it was to be “progressive” or “reactionary” or “unprogressive” or “traditionalist” or otherwise has changed around in a hundred years.

We are now the people stalking. We are now the people who are afraid of media revelation. We are the people who are taught to be frightened and ashamed of our own views. The whole thing has been reversed in a hundred years.

But there is a natural tendency to kick; there is a natural tendency to kick against the system which is in place. And politically correct Liberalism is an enormous target to be attacked. And it is fun to attack it. And it is life-affirming to attack it. And to traduce it and to kick its bottom and to run round and to be chased by it and to be opposed by all these po-faced zealots and that sort of thing.

It’s entertaining, and that’s one of the things that people have to realize that will attract many people to our side. The bloody mindedness of it; the useful cantankerousness of it. Everyone likes a rebel up to a point, as long as they’re not personally and they’re not adversely affected by the consequences of such radicalism. And what we need to do is position ourselves in the way that the International Times and 60s radicals did the other way around.

If we become the lightning rod for cultural revolution in the West, you will see, in the future, student movements that are loyal to the Right rather than Left, even if these terms break down and in increasingly group-based societies no longer have any meaning, as is occurring. But we still use them because it’s an affordable shorthand.

But never forget the thrill of transgression. Right-wing ideas are transgressive. And are therefore interesting, and sexy. Herbert Marcuse once wrote about the eroticism of the Right. Susan Sontag did as well. And the Right is more erotic than the Left, is more exciting than the Left. The Left is boring, the Left is extraordinarily grungy and erotically unexciting, you know, despite its prevalence and its penchant for decadence, there’s a degree to which it is not as radically outside the box.

And my view is that people will be attracted in the future not by reason. They will read up with their reason once they have decided to emotionally commit. The important thing is to get people emotionally. And it’s to appeal to the forces and wellsprings in their mind which are eternal, and which underpin rationality. The power of irrational belief as spiritual codification, of mystical belief, of belief in identity, of the need for communitarianism, and the need to belong, is immensely powerful. Far more powerful than the anything the Left can offer.

If you can tap these forces of — in some respects — codified irrationalism, if you can bring them to the surface, if you can bottle them, and if you can then add on reason and add in the discourse on Counter-Currents, you will tap the energies of future generations of majority Americans. And you will do so because it appears to be extraordinarily interesting. More interesting than anything else. More threatening than anything else. More shocking than anything else. And that is something that the Right should actually in my view heighten, in a civilized and persuasive way.

One should never lose sight of the reason that people are opposed to the our ideas is because they are thrilled to be frightened by them. They are thrilled to be appalled by them. It is the political equivalent of Satanism to many people. I’m saying nothing that is at all original. And in doing so we actually make ourselves tremendously attractive at certain levels of consciousness — not to some Southern Baptist chapter, admittedly. But you make yourself tremendously psychologically appealing. You may not have a halo over your head but you are transfigured in a sort of dark and sepulchral light, which makes you deeply spiritually ambivalent to people who exist now. And that contains the prospect of growth and the prospect of renewal.

I personally believe people agree with ideas long before they moved towards them. They have an instinctual saying of “YES!” They say “YES!” to the idea before they completely have worked out all of the formula for themselves. The Counter-Currents of this world exist to provide the formula for people after they’ve said “YES!”; after they’ve put forward their first step upon the route to identity, and the politics of identity, and the religion of identity.

If I can mention something about that, all the religious divisions that exist amongst people of European ancestry don’t really matter. All that you do is you format a doctrine of psychological inequality. If people believe in equality they can come to it in terms of whatever spiritual system they want. As long as they believe in orders of European inequality, all of the traditions of all of our people can be contained in that.

Thank you very much!

Like primitive Rome, England, during the Middle Ages, had an unusually homogeneous population of farmers, who made a remarkable infantry. Not that the cavalry was defective; on the contrary, from top to bottom of society, every man was a soldier, and the aristocracy had excellent fighting qualities. Many of the kings, like Coeur-de-Lion, Edward III, and Henry V, ranked among the ablest commanders of their day; the Black Prince has always been a hero of chivalry; and earls and barons could be named by the score who were famous in the Hundred Years’ War.

Like primitive Rome, England, during the Middle Ages, had an unusually homogeneous population of farmers, who made a remarkable infantry. Not that the cavalry was defective; on the contrary, from top to bottom of society, every man was a soldier, and the aristocracy had excellent fighting qualities. Many of the kings, like Coeur-de-Lion, Edward III, and Henry V, ranked among the ablest commanders of their day; the Black Prince has always been a hero of chivalry; and earls and barons could be named by the score who were famous in the Hundred Years’ War. At the outset the remedy applied was comparatively mild, for able-bodied mendicants were only to be whipped until they were bloody, returned to their domicile, and there whipped until they put themselves to labor. As no labor was supplied, the legislation failed, and in 1537 the emptying of the convents brought matters to a climax. Meanwhile Parliament tried the experiment of killing off the unemployed; by the second act vagrants were first mutilated and then hanged as felons.[6]

At the outset the remedy applied was comparatively mild, for able-bodied mendicants were only to be whipped until they were bloody, returned to their domicile, and there whipped until they put themselves to labor. As no labor was supplied, the legislation failed, and in 1537 the emptying of the convents brought matters to a climax. Meanwhile Parliament tried the experiment of killing off the unemployed; by the second act vagrants were first mutilated and then hanged as felons.[6]

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

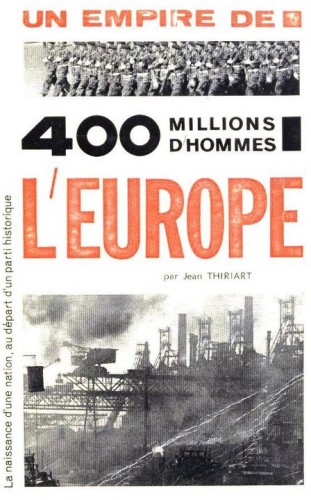

In 1981, a terrorist attack by Zionist criminals against his office in Bruxelles was the decisive input for Thiriart to restart political activity. He kept in touch again with the former dealer of La Nation Européenne, the Spanish historian Bernardo Gil Mugarza, who, during a long interview (108 questions), gave him the chance to newly and better explain his political thought. So a new book could take form: it was a book that Thiriart wanted to publish in Spanish and German languages, but it is still unpublished.

In 1981, a terrorist attack by Zionist criminals against his office in Bruxelles was the decisive input for Thiriart to restart political activity. He kept in touch again with the former dealer of La Nation Européenne, the Spanish historian Bernardo Gil Mugarza, who, during a long interview (108 questions), gave him the chance to newly and better explain his political thought. So a new book could take form: it was a book that Thiriart wanted to publish in Spanish and German languages, but it is still unpublished.

Le wallon a toute sa place dans l’histoire des peuples d’Europe. Wallon vient de Wahl, un vieux mot germanique utilisé par les Germains pour désigner les populations celtophones et romanes. La langue wallonne est très ancienne et comme le picard, le champenois ou encore le normand, elle est une langue d’Oïl qui fait partie du groupe des langues gallo-romanes. Bon nombre des évolutions que l’on considère comme typique du wallon sont apparues entre le 8° et le 12° siècle et vers 1200, la langue wallonne était nettement individualisée. Le wallon n’est donc pas un français abâtardi ou incorrect, c’est une langue en soi qui n’a simplement pas aussi bien réussi que le patois français et nombre des belgicismes découlent directement du wallon. Je rappelle que les peuples wallons n’ont jamais fait partie de la France, sauf quand ils ont été occupés, mais faisaient partie du SERG et particulièrement la Principauté de Liège. La place des wallons de l’Est étaient certainement d’être à l’époque un pont entre les mondes germaniques et romans. Il paraît qu’il y aurait 15 à 20 % des mots wallons qui seraient d’origine germanique et c’est sûrement dans le dialecte du wallon oriental, celui de Liège et d’Ardenne, que cela se retrouve le plus et qui rend notre dialecte si particulier. Je vais me permettre de vous lire comme exemple quelques courtes phrases :

Le wallon a toute sa place dans l’histoire des peuples d’Europe. Wallon vient de Wahl, un vieux mot germanique utilisé par les Germains pour désigner les populations celtophones et romanes. La langue wallonne est très ancienne et comme le picard, le champenois ou encore le normand, elle est une langue d’Oïl qui fait partie du groupe des langues gallo-romanes. Bon nombre des évolutions que l’on considère comme typique du wallon sont apparues entre le 8° et le 12° siècle et vers 1200, la langue wallonne était nettement individualisée. Le wallon n’est donc pas un français abâtardi ou incorrect, c’est une langue en soi qui n’a simplement pas aussi bien réussi que le patois français et nombre des belgicismes découlent directement du wallon. Je rappelle que les peuples wallons n’ont jamais fait partie de la France, sauf quand ils ont été occupés, mais faisaient partie du SERG et particulièrement la Principauté de Liège. La place des wallons de l’Est étaient certainement d’être à l’époque un pont entre les mondes germaniques et romans. Il paraît qu’il y aurait 15 à 20 % des mots wallons qui seraient d’origine germanique et c’est sûrement dans le dialecte du wallon oriental, celui de Liège et d’Ardenne, que cela se retrouve le plus et qui rend notre dialecte si particulier. Je vais me permettre de vous lire comme exemple quelques courtes phrases : Pour résumer, pour retirer un bénéfice quelconque d’une autonomie, ce qu’il nous faut, c’est faire la différence entre Wallons et Francophones. Le wallon est celui qui a ses racines, c’est-à-dire ses ancêtres, en Wallonie et aussi qui parle, qui vit wallon. Et par-dessus tout, ce qu’il nous faut, c’est garder notre fierté. J’entendais à la fin d’un concert d’un groupe acadien ce cri du coeur : soyez toujours fiers de qui vous êtes, et les dieux savent si les Acadiens ont failli perdre leur identité et souffrent encore pour la garder. C’est la fierté qui les sauvent et qui nous sauvera. Tout le reste, programmes, subsides, etc… en dépend.

Pour résumer, pour retirer un bénéfice quelconque d’une autonomie, ce qu’il nous faut, c’est faire la différence entre Wallons et Francophones. Le wallon est celui qui a ses racines, c’est-à-dire ses ancêtres, en Wallonie et aussi qui parle, qui vit wallon. Et par-dessus tout, ce qu’il nous faut, c’est garder notre fierté. J’entendais à la fin d’un concert d’un groupe acadien ce cri du coeur : soyez toujours fiers de qui vous êtes, et les dieux savent si les Acadiens ont failli perdre leur identité et souffrent encore pour la garder. C’est la fierté qui les sauvent et qui nous sauvera. Tout le reste, programmes, subsides, etc… en dépend.