Apuntes sobre el Mitraismo

Enrique RAVELLO

Ex: http://identidadytradicion.blogia.com/

La historiografía utiliza el término de «cultos mistéricos» para todo el conjunto de formas religiosas que, procedentes de Oriente, irrumpen en el Imperio romano tardío. El engañoso término de cultos mistéricos podría hacernos pensar en una unidad interna de los mismos; nada más lejos de la realidad, poco tenían que ver entre sí los cultos a Attis, Cibeles, Serapis, Isis o Júpiter - Amón , pero si uno de ellos merece mención aparte es, sin duda, el culto a Mitra.

Es precisamente lo que le diferencia del resto lo que le hace interesante para nosotros y lo que motiva el sentido de este artículo: a diferencia del resto de divinidades «orientales» llegadas a la Urbs desde el cambio de Era, Mitra sólo tiene de «oriental» la procedencia geográfica: Persia, siendo una de las divinidades que los indoeuropeos de origen nordeuropeo (medos, persas, hindúes y mitanios) llevaron a Asia durante sus migraciones e invasiones de aquellas tierras. Divinidad indoeuropea que, como tal no podía ser extraña a los romanos, los que pronto la asimilaron con sus dioses solares; así Mitra no era uno más de los cultos de «religiosidad segunda» del Bajo imperio , sino que propuso una posibilidad de enderezamiento espiritual -siguiendo el concepto evoliano- en un momento en que la Tradición romana parecía haber entrado en una fase de crisis

Mitra y su ascesis son profundamente indoeuropeos :«Los misterios mitraicos nos llevan al seno de la gran tradición mágica occidental , a un mundo todo él de afirmaciones , todo de luz y de grandeza , de una espiritualidad que es realeza y de una realeza que es espiritualidad , a un mundo en el que todo lo que es huída de la realidad , ascesis , mortificación en humildad y devoción , pálida renuncia y abstracción contemplativa , no tienen ningún lugar . Es la vía de la acción de la potencia solar» (1).

MITRA : DEL MUNDO INDO-IRANIO A ROMA.

Mitra como divinidad ario-irania

Para determinar los orígenes de Mitra hay que remontarse a la religión preavéstica donde aparece junto a Varuna y Surya entre los dioses soberanos o de la primera función indoeuropea. Mitra preside las alianzas y asegura la soberanía de los persas en las tierras recientemente conquistadas, asegura también la feliz doma de animales (2). Es un dios común a los indo-arios de la India y Persia, pero entre estos últimos tiene una función más guerrera que entre los primeros. Su nombre significa a la vez «alianza» y «el amigo» (3) . Mitra aparece en el panteón de tres pueblos indoeuropeos étnicamente muy relacionados: indo-arios, iranios y mitanos, de los que todo hace pensar que se trató de una rama de los indo-arios que se desgajó hacia zonas más occidentales. Siempre aparece como divinidad de la primera función junto a Varuna con quien está en una relación de complementariedad, en todos los sentidos «si los principios conjuntos se consideran en su reciprocidad, el Dios manifestado es el poder masculino y la Divinidad no manifestada es el poder femenino, reserva inagotable de toda posibilidad incluida en la manifestación: es pues Mitra, quien fecunda a Varuna (PB XXX10,10)» (4).

Etimológicamente la raíz de su nombre sería la indoeuropea *mei/*moi- con la idea de intercambio, seguido del instrumental -tra. Ésta es al menos la opinión de Meillet y la que más consenso tiene entre los estudiosos. Así Mitra inicialmente habría sido el garante de los acuerdos, el orden del mundo y del orden social, en definitiva de la relación de los dioses con los hombres y de éstos entre ellos mismos. Mitra engloba los conceptos de amigo y de contrato, y, siguiendo a G Bonafonte la evolución conceptual habrá comenzado desde esa raíz *mei/* moi (intercambio) -obligación mutua (por intercambio de bienes) -amigo, amistad - dios Mitra (5). Siendo el garante de la palabra dada, y, en definitiva, de las relaciones entre los dioses y los hombres y de éstos entre sí. Mitra es quien «sostiene el cielo y la tierra» (Rg Veda, 3, 59).

En el espacio temporal que va desde la época védica hasta la reforma zoroastriana, la figura de Mitra también experimentará ciertos cambios, más bien matices, en la naturaleza y función de su divinidad.

En el mundo védico, Mitra y Varuna son las dos caras complementarias (que no antitéticas) de la función soberana del panteón indoeuropeo, una relación semejante en el mundo latino sería la de Rómulo- Numa (6). El Mitra védico encarna los aspectos jurídico soberanos, luminosos, siendo un dios cercano al mundo y a los hombres «la función de este culto (el de Mitra) es por lo tanto la de orientar religiosamente y consolidar la cohesión familiar, de amistad, social y, por lo tanto, la red de relaciones interpersonales que constituyen el tejido constitutivo de la vida de una tribu, de un pueblo, de una etnia» (7). Por su parte, Varuna encarna el aspecto mágico, violento, invisible y lejano.

Para conocer la figura del Mitra del mundo iranio antiguo, tenemos una gran escasez de fuentes para el periodo más arcaico. Durante la predicación de Zaratustra , todos los dioses del panteón persa se subordinan a Ahura Mazda y, aunque el nombre de Mitra aparezca en el Avesta, donde se le dedica un himno , lo hace de forma casi ocasional , esto ha sido interpretado por los estudiosos como un «eclipse» de esta divinidad , «relegada» por Zaratustra a un papel secundario , aunque hay otro tipo de opiniones : «Los estudiosos occidentales han sacado la errónea conclusión de que Mitra había sido rechazado por Zaratustra sólo porque no es mencionado en los Gatha , como si Zaratustra no hubiese compuesto más que los himnos de fragmentario corpus que han llegado a nosotros» (8). Aparece en el décimo Yashts (cántico) del Avesta, y se enfatiza su aspecto guerrero, y su función de guardián de la moral (9).

A. Loisy confirma que el origen de Mitra se encuentra en la religión preavéstica , en la que es el mediador entre el mundo superior y luminoso donde impera Ahura Mazda y el inferior donde ejerce su influencia Arimán (10).En el Mitra -Yasht , un himno religioso en su honor fechado entre el siglo V y VI a. C. aparece como el dios de la luz , de los guerreros , de los pactos y de la palabra dada, algo que protege muy especialmente y cuya alteración o incumplimiento queda determinado como un sacrilegio y una grave perturbación del orden social y cósmico. Está claramente relacionado con la luz y el sol. Es descrito como «el más victorioso de los dioses que marchan sobre esta tierra», «el más fuerte de los fuertes» y físicamente como «el dios de los cabellos blancos», siendo -como ya sabemos- muy frecuentes los elementos fenotípicamente nórdicos en las descripciones físicas de las divinidades indo-ario-persas.

Bajo el reinado de Aqueménida, es la divinidad principal con la diosa Anahita y Ahura Mazda, siendo al dios que invocan los reyes en sus testamentos y combates. La religión medo-persa no tenía imágenes, que llegaron con la helenización del Asia menor, a la divinidad que más afectó este proceso fue precisamente a Mitra, que desde estos momentos pasó a un primer plano. Además durante el Helenismo muchas divinidades son asimiladas a los dioses greco-latinos, Ahura Mazda lo será con Júpiter; Ahrimán se convertirá en Hades; mientras que Mitra, conservará su nombre, ya que no tiene correspondencia exacta con los dioses greco-latinos, y aunque durante el Helenismo es el segundo dios en importancia, sin duda es el más adorado.

F. Cumont pone de relieve la importancia y la admiración que se tuvo entre los griegos y los romanos hacia el Imperio aqueménida , y cómo muchas de sus instituciones fueron adoptadas por los emperadores romanos por ejemplo los amici Augusti, del mismo modo que llevar delante del César el fuego sagrado como emblema de la perennidad del poder (11) . Lo que ya es más difícil es seguir los caminos, bastante más ocultos, por los que se transmitieron las ideas de unos pueblos a otros. Parece cierto que a comienzos de nuestra Era, determinadas concepciones mazdeas se habían difundido más allá de Asia. La conquista macedónica de Asia Menor puso a los griegos en contacto directo con el mazdeísmo y hubo un interés general entre los filósofos por su conocimiento. Así como la «ciencia» que se extendía entre las clases populares con el nombre de magia, tenía, como su propio nombre indica, en gran parte origen persa. Antes de la conquista de Asia por Roma, algunas instituciones persas ya habían hallado en el mundo greco-oriental imitadores y adeptos a sus creencias. Los más activos agentes de esta difusión parecen haber sido para el mazdeísmo -como, por otro lado también para el judaísmo -las colonias de fieles que habían emigrado lejos de la madre patria (12).

Aún así es conveniente recordar la opinión de Julius Evola respecto a la relación entre el culto de Mitra y la religión zoroástrica: «Emanación del antiguo mazdeísmo iránico, el mitraísmo retomaba el tema central de una lucha entre las potencias de la luz y las de las tinieblas y el mal. Podía tener también formas religiosas, exotéricas, pero su núcleo central estaba constituido por sus Misterios, o sea por una iniciación en el verdadero sentido. Ello constituía un límite, aunque así se hacía una forma tradicional más completa. Sucesivamente, se debía, sin embargo, asistir a una cada vez más decidida separación entre la religión y la iniciación» (13)

De Persia a Roma.

Fue F. Cumont el primero en afirmar la continuidad entre el Mitra iranio y el del culto de época romana, tesis admitida por la práctica totalidad de los estudiosos. S. Wikander negó esta identificación, pero su tesis es paradoxal e insostenible, otro en negarla más recientemente ha sido David Ulansey (14) en su libro, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries(15) quien centra exclusivamente su interpretación del mitraísmo como religión astrológica y la representación del Mitra tauróctono únicamente desde el punto de vista astrológico zodiacal, si bien los datos que aporta sí son interesantes , la interpretación de fondo no deja de ser limitada por reduccionista.

En cuanto a la propagación propiamente dicha del mitraísmo en Occidente, data de la fecha de la anexión de Asia Menor y Siria. Y aunque parece haber existido ya en Roma , en la época de Pompeyo, una comunidad de adeptos, la auténtica difusión no comenzó hasta el tiempo de los Flavios, y fue cada vez más importante con los Antoninos y los Severos, para ser hasta finales del siglo IV el culto más importante del paganismo. Aunque hay que tener en cuenta que la influencia de Persia, no fue sólo religiosa, sobre todo desde el 88 d. C; con la llegada al poder de la dinastía Sasánida. En la propia corte de Diocleciano se adoptaron las genuflexiones ante el emperador, igualado a la divinidad. Así que la propagación de la religión mitraica, que siempre se proclamó orgullosamente persa, se vio acompañada de una influencia persa en la política, la cultura y el arte.

En cuanto al proceso concreto de llegada de Mitra desde Irán a la península itálica, tenemos una dramática ausencia de fuentes, dos líneas de Plutarco, y una referencia de un mediocre escolástico de Estancio, Lactancio Plácido. Ambos autores coinciden en situar en Asia Menor el origen de la religión irania que se difundió por Occidente, así el mitraísmo se había constituido, antes de que fuese descubierto por los romanos, en las monarquías anatólicas de épocas precedentes, allí llego en la época de dominio Aqueménida, donde los persas se convirtieron en la aristocracia dominante de Capadocia, Ponto o Armenia, y seguirían siendo los amos de la zona después de la muerte de Alejandro. Esta aristocracia militar y feudal propició a Mitríades Eupator, un buen número de oficiales que ayudaron a desafiar a Roma y a defender la independencia de Armenia. Estos guerreros adoraban a Mitra como genio militar de sus ejércitos, y es por esto por lo que siguió siendo siempre, incluso en el mundo latino, el dios «invencible», tutelar de los ejércitos y honrado, sobre todo, por los soldados.

Paralelamente a esta nobleza, otra clase también persa se había establecido en Asia Menor, los «magos» estaban diseminados por todo el Levante y conservaron escrupulosamente sus ritos. Sería el máximo fundamento de la grandeza de los misterios de Mitra.

La religión mazdeísta fue a los ojos de los griegos puramente bárbara y no tuvo ningún eco entre los helenos, como sí pudo tener el culto de Isis y Serapis, los griegos jamás aceptaron una divinidad que viniera de sus eternos enemigos. Mitra pasó directamente al mundo latino, además la transmisión fue de una rapidez fulminante, pues los romanos nada más conocer la doctrina de los mazdeos, la adoptaron con entusiasmo. Y llevado hacia fines del siglo I por los soldados a todas las fronteras, el culto de Mitra llegó al Danubio, al Rin, Britania, fronteras del Sáhara y valles de Asturias. Mitra conquistó pronto el favor de los altos funcionarios y del propio emperador. A finales del siglo II, Cómodo se hizo iniciar en los misterios, cien años después su poder era tal que eclipsó a todos sus rivales en Occidente y en Oriente. En 307 Diocleciano, Galeno y Licio le consagraron como protector del Imperio, fautori Imperio sui.

MISTERIA MITRAE

Los mitreos

El de Mitra es un culto totalmente mistérico que celebraban los iniciados para sí. Las cofradías mitraicas admitían solamente a hombres. El primitivo lugar de adoración de Mitra debieron ser las grutas de las montañas, especie de cavernas, en la época que nos ocupa, eran ya los mitreos que consistían en una pequeña capilla, pero, en definitiva seguían siendo grutas, a los que los iniciados se referían como specus. La distribución de la nave parece un comedor, pues el rito principal consistía en una comida para los iniciados, «en efecto, el Mithraeum no es, como el templo greco-romano, la casa de dios, sino un lugar de comunión entre los hombres y los dioses» (16). Había en los mitreos una mesa de piedra en la que estaba representado Mitra matando al toro, montado sobre un eje y esculpida a ambos lados, donde se combinaban imágenes del sol. Este pequeño santuario representaba el mundo, además toda su decoración tenía un alto contenido simbólico, aunque difícil de interpretar por la ausencia de textos contemporáneos. El Mitra tauróctono representa el sacrificio del toro, el tauribolio, como principio de la vida bienaventurada prometida al iniciado.

El acceso al mitreo era por una sola puerta, para descender algunos escalones, la capacidad no excedía las 100-120 personas, el lugar sagrado estaba reservado a los iniciados, el resto estaba en salas adyacentes. La disposición interna es constante, la imagen de Mitra está siempre en el centro o en la pared del fondo y en las escenas representadas aparece matando al toro y rodeado de los dadóforos, bien visible está el altar o la mesa sobre las que se apoyan las ofrendas y los alimentos, a los lados los bancos para los sacerdotes, destacando siempre el podium para el pater que preside la asamblea. En el mitreo no hay ventanas, y, al ser las reuniones nocturnas, la luz constituía un elemento de suma importancia, siendo el reclamo al Sol. En el ingreso al mitreo había un zodiaco, representando al universo, en el centro se reúne y canta la comunidad iniciática, reforzando la solidaridad fraterna del grupo.

El culto a Mitra conocía la semana con consagración de los siete días a las siete esferas planetarias, santificándose especialmente el primer día dedicado al Sol. Había también fiestas estacionales, se cree que tuvo cierta importancia la del equinoccio de primavera, común a otras iniciaciones, pero sin duda la más importante fue la de la Natividad del Sol, fiesta del Sol Invictus, que se celebraba, coincidiendo con el solsticio de invierno, el 25 de Diciembre. Mitra nace entre un buey y una mula en una gruta, con dos pastores de testigos: Cautes y Cautópates, Cautes tiene una antorcha encendida hacia arriba (el día), Cautópates tiene una antorcha encendida hacia abajo (la noche).

Los grados iniciáticos

La religión de Mitra no era un conocimiento sagrado escrito y codificado, que se podía aprender leyendo, la verdad sobre la que se sustenta, la base de sus misterios, son transmitidos de boca a oído entre los fieles y adeptos de las distintas jerarquías internas.

Siete eran los grados por los que debía de pasar un iniciado que pretendiera llegar al grado supremo: el cuervo, el oculto, el soldado, el león, el persa, el mensajero del Sol, y el padre. Se piensa que se determinaron según los siete planetas y son las siete esferas planetarias que el alma tendría que atravesar hasta llegar a la morada de los bienaventurados. No ajeno a este concepto es la expresión aún hoy coloquial de «llegar al séptimo cielo», para hacerlo el iniciado mitraísta tenía que atravesar siete puertas anteriores:

La primera es de plomo y frente a Saturno, debe despojarse del peso del cuerpo y de su vinculación a la vida y la tierra.

Venus le espera en la segunda, hecha de estaño, y le exige el abandono de la belleza física y del placer sexual.

En la siguiente puerta, que es de bronce, se encontrará con Júpiter ante el que tendrá que despojarse de la seguridad personal y la confianza en sí mismo y su pequeño yo.

La cuarta es de hierro y Mercurio es quien la custodia, ya no sirven ni inteligencia ni cultura, tampoco la antorcha luminosa ilumina nada ante la verdadera luz que es dios.

Frente a la puerta de Marte - de bronce y hierro - nada puede hacer la espada que es sustituida por la fuerza divina.

La Luna vela la puerta de plata donde se dejan orgullo, ambiciones y amor a sí mismo, amor que sólo merece dios.

La última puerta es de oro y la cuida el Sol, quién tiende la mano al adepto pidiéndose un último gesto, ir más allá de sí mismo aceptando la mano que el propio Sol le está ofreciendo .

También, cada uno de los siete grados estaba influenciado por una diferente esfera planetaria:

korax (cuervo) Mercurio

nymphus Venus

miles (soldado) Marte

leo (león) Júpiter

perses (persa) Luna

Heliodromus Sol

Pater Saturno (17)

Según Porcino (18) los cuervos serían una especie de auxiliares de los misterios, puede que en algún tiempo fuesen niños.

Este primer grado toma su nombre del animal que en la tauroctonía lleva a Mitra el mensaje de dios en el que le ordena matar al toro. Así el iniciado que tiene este grado, protegido por Mercurio, «es portador de mensajes» (19). Téngase presente también la relación entre las aves y el «lenguaje simbólico». Según los restos que nos han llegado, especialmente del mitreo de Capua, sabemos que viste una capa blanca con bandas rojas. En las ceremonias tiene la función de servir los alimentos que él no puede probar, el sentido es desposeer al iniciado de primer grado de los restos de ego profano.

El segundo grado tiene dos nombres, el de cryphius y el de nimphos. El primero (el oculto) ha sido relacionado con el hecho de que permanece escondido, no aparece en los bajorrelieves, sólo se les mostraba una vez y parece que era una ceremonia especialmente solemne. Puede que primitivamente fueran adolescentes, antes de llegar a soldados, que vivían en un régimen de separación especial. Pero realmente si hay presencia de este grado en los restos arqueológicos, con lo que habrá que centrarse en su segundo nombre nimphus o nymphos para darle una interpretación correcta. Así mismo, nymphos puede tener dos significados, el de esposo o mejor prometido, que lo relacionaría con Venus, su esfera protectora, y el Amor (en sentido iniciático) que debe tener hacia Mitra. También puede significar ninfa-crisálida, haciéndose referencia a una especie de proceso metamórfico en el que « de gusano» (= el ser ligado a lo terreno, a las pasiones y a los instintos), pasa al estado de «crisálida» (=el huevo, el estado de clausura de aislamiento y de preparación), para propiciar el nacimiento de esa abeja o «mariposa» (=la capacidad en acto del alma de alzar el vuelo, de desvincularse de las ataduras terrenas)» (20). En este grado viste un velo amarillo sobre su rostro -de ahí lo de oculto -y tiene como atributo una lámpara, símbolo de la luz necesaria para la consagración de este grado,

El soldado, es un iniciado propiamente dicho. En la Antigüedad ya guerreros plenamente dedicados al combate y a la caza. Su iniciación era una especie de bautismo, con la imposición de una marca en la frente, similar al cristiano. Sus símbolos son la espada y la corona. Corona que, simbolizando el poder, se le ofrece y debe rechazar al grito de «Mitra es mi corona ». En los mitreos de Capua y Ostia aparece con una capa ornada en púrpura y un gorro frigio. Su misión es garantizar la justicia y el orden. En los ritos de iniciación es el «liberador» y en las asambleas el encargado de mantener el orden.

En la exaltación al grado de los leones, se vierte miel en vez de agua, sobre sus manos y se les invita a conservarlas puras de todo mal, mala acción y de toda mancha, también con la miel se les purifica la lengua de toda falta. La miel tiene una gran importancia en la tradición persa, se cree que es una sustancia celestial, llegada de la luna, es superior al agua en su virtud, y comparable desde el punto de vista místico al brebaje sagrado del haoma. En los restos arqueológicos aparece con una toga roja y un manto rojo, en algunas ocasiones con remates amarillos. Es importante hacer notar que, a diferencia de los grados inferiores, es ahora -como leo- cuando el adepto recibe un nuevo nombre. Para este grado -protegido por Júpiter- su atributo simbólico es el rayo, símbolo presente en varias tradiciones indoeuropeas: Zeus, Odín, Indra y Varuna también lo tienen como iconografía propia. El rayo, símbolo de la luz y potencia, estaría aludiendo a una experiencia de iluminación interior, el paso a un estado superior de conciencia.

El nombre del persa, es una clara referencia a la patria de origen del dios Mitra. También se usa la miel en su consagración, pero con un simbolismo diferente, «es considerado como el guardián de los frutos en amplio sentido (incluidos los cereales) y en la Antigüedad la miel usada de azúcar fue símbolo de conservación» (21). En cierta medida representaría a Mitra en su relación con la vegetación y la fecundidad de la tierra.

Sin embargo mucho más interesante nos parece la interpelación de este grado y su relación con la Luna que hace Stefano Arcella en su libro, I Misteri del Sole, aplicando criterios tradicionales y evolianos donde otros autores positivistas se limitan a criterios racionalistas, arqueológicos e incluso artísticos con los que es imposible penetrar y descifrar el mito. Para Arcella la Luna sería su numen titular, al ser el astro que da luz durante la noche, leído interior y simbólicamente, se estaría dando a entender que el iniciado-durante esta fase- tendría que sumergirse en su propio mundo interior «sin luz» -asimilado con la noche- tomar conciencia de él y ser capaz de dominarlo, ese viaje nocturno sólo podría hacerse bajo la protección de la Luna que ilumina las tinieblas. Así -intuye el autor italiano -habría que pensar que la iniciación de este grado sería durante la noche, y, posiblemente, las pruebas consistieran en cumplir determinadas encomiendas aun a pesar de la nocturnidad y la oscuridad, es decir «venciendo la noche». En las ceremonias del culto llevaba el traje persa y el gorro frigio que también llevaba Mitra.

Heliodromus es el corredor del Sol, Arcella también lo califica como «la puerta del Cielo». Se asimila al Sol, pues no corre delante del Sol, sino que sube con él en un carro, es el grado anterior al supremo, y se muestra al adepto sobre el carro del cielo, adonde le basta penetrar con Mitra para alcanzar la esfera de la divinidad. «Heliodromus está subordinado al Pater, como el Sol lo está a Mitra, verdadero Sol Invictus» (22).Viste túnica roja con cinturón amarillo y se le representa con una antorcha encendida. En este grado se le vuelve a ofrecer la corona -rechazada anteriormente-y esta vez la asume, porque ahora la corona no está simbolizado el poder mundano sino que es la corona-rayo que simboliza los rayos solares y significa la apertura del iniciado a la Luz del Sol espiritual. La corona tiene siete rayos, cifra presente en varias tradiciones, por lo menos desde el Pitagorismo, según el cual cada planeta irradia una propia vibración sonora, siete son los planetas a los que están ligados los adeptos mitraicos, así como siete son los días de la semana. Sin duda el requisito para llegar a Heliodromus era ser capaz de dominar los impulsos concupiscibles e irascibles del alma «La iniciación al grado de Heliodromos sucedía, verosímilmente, cuando cantaba el gallo, a la primera luz del alba, ya que el iniciado debía entrar en sintonía con el sentido anímico de abrirse a la luz» (23). Durante los banquetes guía a los comensales y hace los honores de la casa.

El padre es el grado supremo, su dignidad corresponde a la de Mitra en el cielo. Son los perfectos iniciados que participan plenamente de Mitra. A su cabeza está el padre de los padres (24). Cumbre de la jerarquía, lleva un gorro frigio ornado con perlas y un manto púrpura sobre una túnica roja con bandas amarillas, lleva un anillo y en la mano derecha el bastón que simboliza mando y poder. Es el guía de la comunidad. Entre sus atributos estaba la hoz. El cetro del mago y el gorro de persa. En un mitreo encontrado en Mesopotamia los padres estaban representados con hábitos persas, sentados en tronos, el cetro del mago en la mano derecha y en la izquierda un pergamino, que simboliza su conocimiento de los textos rituales y su significado religioso. Eso, y la elección del vocablo Pater los relaciona con la tradición jurídica y religiosa romana, de la misma estirpe que la indo-aria.

Lejos de considerar el paso por los diferentes grados iniciáticos como una convención o algo parecido a una representación teatral para adeptos, hay que reflexionar sobre las indicaciones que, al respecto, da Evola: «Existe un nivel en el que resulta por evidencia inmediata que los mitos misteriosóficos son, esencialmente, transcripciones alusivas de una serie de estados de conciencia a lo largo de la autorrealización. Las diferentes gestas y las varias vivencias de los héroes míticos no son ficciones poéticas, sino realidades- son actos bien determinados del ser interior que relampaguean uniformemente en cualquiera que quiere avanzar en la dirección de la iniciación, esto es, en la dirección, de un cumplimiento más allá del estado humano de existencia» (25).

Iniciaciones y celebraciones.

Aunque se ignora cuál era el ritual de las iniciaciones, se sabe que entre las condiciones preliminares de admisibilidad a los distintos grados había «pruebas» bastante duras y que incluso el ritual de las iniciaciones, sobre todo para el soldado, mantenía cuanto menos un simulacro de luchas y peligros. A juzgar por los restos encontrados en los mitreos los sacrificios de animales debían ser numerosos.

Además existía la oblación del pan del brebaje sagrado, imitado luego por los cristianos, y en esta «comunión» se repetían las palabras «éste es mi cuerpo» y «ésta es mi sangre», pues representaban la sustancia del toro mítico y divino que era Mitra, entendido como Ser supremo. El líquido que se servía pudo ser agua o en ocasiones vino, aunque en su inicio era ahoma (el soma de la India védica), que se mantuvo en el ritual ascético, pero ante la imposibilidad de obtener la planta sagrada, se sustituyó el líquido aunque no el significado.

Las imágenes que tenemos de escenas iniciáticas corresponden a los frescos del mitreo de Capua, en todas vemos características comunes: el iniciado desnudo, vendado y/o arrodillado; el oficiante poniéndole una túnica blanca, el pater con un gorro y una capa roja.

En otro mitreo cercano a Roma, se han encontrado dos series de representaciones que corresponden a las procesiones de los leones; la primera serie está fechada en 202, en ambas los iniciados de cuarto grado, aparecen desfilando ante el Pater, al que le ofrecen algunos dones. En estos tipos de ritos mitraicos dos elementos son constantes y tienen una importante función simbólica; el incienso; común a varias tradiciones espirituales, siempre con un sentido de purificación; y el fuego , como símbolo de luz y vida, doblemente como símbolo de sacralidad solar, y como símbolo de la «cadena» que forman los iniciados en los misterios mitraicos, que-cada uno de ellos individualmente -una vez establecido el contacto con esa Luz son capaces de transformar y dominar su elemento telúrico- lunar- taurino, otro de los significados -y no el menos importante del simbolismo de la tauroctonía mitraica.

La comida sagrada, otra celebración importante para la comunidad mitraica, simbolizaba el encuentro entre Mitra y el Sol. El pan consagrado remitía a la unión mística del grupo que, ingiriéndolo se apropiaba de una determinada energía, que les transmutaba en algo diferente (el paralelismo con la eucaristía cristiana es más que evidente). También se consagraba el vino, que en el mitraísmo romano había sustituido definitivamente al ahoma iranio, que ya nadie sabía cómo lograr preparar. Para S. Arcella cabría otra lectura de este banquete: «...inherente a la realización individual: una vez vencida, sacrificada y transformada la propia componente "taurina", el iniciado se encuentra y se reúne con su Principio solar (en el símbolo: el banquete entre Mitra y el Sol): utiliza toda la energía de la naturaleza inferior, a favor de un empuje ascendente y de una estabilidad en la realización espiritual» (26).

En cuanto al aspecto de la autorrealización individual , y de la posibilidad de potenciar determinadas facultades innatas en sentido de lograr una identificación ontológica con la divinidad, tenemos pruebas documentales en el llamado Ritual Mitraico del Gran Papiro Mágico de París, en el que se habla claramente de un rito no comunitario sino individual, en el que el iniciado a los «misterios mayores» -es decir grados superiores- entra en disposición de lograr un contacto unificador con el dios, venciendo el elemento «taurino-telúrico» y lo hace con la pronunciación de nuevo logos, que cada uno de ellos abre sucesivas puertas sutiles, produciéndose los correspondientes saltos de calidad ontológica . Estos logos serían parte de la técnica tradicional de la sonoridad ritual capaz de dar vibraciones «sutiles» que producen cambios a nivel interno y externo, es el mantra hindú.

Iconografía

Mitra nace de una piedra, y siempre -desde el momento de su nacimiento -es representado con un puñal en la mano derecha y una antorcha en la izquierda, los cabellos en forma de rayos solares. También existe otra versión menos extendida en la que el dios nace de un árbol o de la parte inferior del «huevo cósmico». La lectura desde el simbolismo tradicional infiere que el nacimiento de una roca alude a la materialidad que encierra un elemento luminoso y vivificar, que ahora -con el nacimiento- es capaz de regenerar su naturaleza anterior, si Mitra nace de la piedra, su cuerpo es el templo -no la cárcel- de su espíritu desde el cual puede manifestar todo su poder y luminosidad «la organización corpórea es el signo de un cierto núcleo de potencia cualificada, y la iniciación mágica no consiste en disolver tal núcleo en la indistinta fluctuación de la vida universal, al contrario, en potenciarlo, en integrarlo, en llevarlo no hacia atrás, sino adelante» (27) la piedra sería también símbolo de la incorruptibilidad, «estaríamos tentados de establecer una analogía entre esta génesis de Mitra y un tema del ciclo artúrico, en el que figura una espada que hay que extraer de una piedra que flota sobre las aguas» (28). El nacimiento de un árbol podría tener el mismo significado, el de la potencial sacralidad de la naturaleza, pero también podría relacionarse con la imagen del árbol como guardián y fuente de la sabiduría eterna, en paralelo con el caso de Wotan y el Yggdrasil. El nacimiento desde el Huevo Cósmico, símbolo de la potencialidad que origina la Manifestación Universal, remite a la fuerza espiritual parte de esta manifestación.

En varias escenas de su nacimiento, vemos que Mitra está acompañado por un grupo de pastores, interpretados por Evola como ciertas «superiores presencias espirituales » que ayudan en el nacimiento iniciático (29). En otras tantas, vemos que en su nacimiento, Mitra está acompañado de dos personajes: Cautes y Cautópates, el primero, Cautes, lleva una antorcha con el fuego hacia arriba, representa la luz del Sol ascendiente, del día que crece: del solsticio de invierno al solsticio de verano, también el amanecer; la antorcha de Cautópates está hacia abajo representando la luz del Sol que decrece: del solsticio de verano al solsticio de invierno, también el atardecer.

Ética mitraica. La dexiosis.

F. Cumont se pregunta el porqué del éxito del mitraísmo. Según él esta religión, la última de las orientales en llegar a Roma, aporta una nueva idea: el dualismo. Se identificó el principio del Mal, rival del dios supremo; con este sistema, que proporcionaba una solución simple al problema de la existencia del mal-escollo para tantas teologías- sedujo tanto a mentes cultas como a las masas. Pero esta concepción dualista, no basta para que la gente se convirtiera a la nueva religión, además el mitraísmo ofrecía razones para creer, motivos para actuar y temas de esperanza, esta religión fue el fundamento de una ética y una moral muy eficaz y concreta, esto fue lo que en la sociedad romana de los siglos I y III, llena de insatisfechas aspiraciones hacia una justicia y una ética más perfecta, garantizó el éxito de los misterios mitraicos. Según el emperador Juliano, Mitra daba a sus iniciados entolai o mandamientos y recompensas en éste y en el otro mundo a su fiel cumplimento. Y así el mazdeísmo trajo una satisfacción largo tiempo esperada y los latinos vieron en ella una religión con eficacia práctica y que imponía unas reglas de conducta a los individuos que contribuían al bien del Estado.

Mitra, antiguo genio de la luz, se convirtió en el zoroastrismo y continuó siéndolo en Occidente, en el dios de la verdad y de la justicia. Fue siempre el dios de la palabra dada y que asegura estrictamente el cumplimiento de los acuerdos y pactos. En su culto, se exaltaba, la lealtad y sin duda se buscaba inspirar sentimientos muy similares a los de la moderna noción de honor. También se predicaba el respeto a la autoridad y la fraternidad, al considerarse los iniciados como hijos de un mismo padre, pero a diferencia de la «fraternidad cristiana» basada en la compasión o en la mansedumbre, la fraternidad de estos iniciados, que tomaban el nombre de soldados era más afín a la camaradería de un regimiento, y se basaba en aspectos viriles y guerreros.

En la religión de Mitra tiene gran importancia la lucha y la acción, es loable la resistencia a la sensualidad y la búsqueda de la virtud, pero para llegar a la pureza espiritual, hace falta algo más, es la lucha constante contra la obra del espíritu infernal, sus creaciones demoníacas salen constantemente de los abismos para errar por la superficie de la Tierra, se meten por todas partes y llevan la corrupción, la miseria y la muerte. Los guías celestiales y guardianes de la piedad deben impedir que triunfen. La lucha es continua y se refleja en el corazón y la conciencia del hombre, miniatura del universo, entre la divina ley del poder y las sugestiones de los espíritus perfectos. La vida es una guerra sin cuartel, una continua lucha. Los mitraístas no se perdían en misticismos contemplativos, su moral agonal, favorecía sobre todo la acción y en una época de anarquía y desconcierto los iniciados hallaban en sus preceptos un estímulo en consuelo y orgullo. El cielo se merece, se gana en la guerra, el mismo concepto lo tenemos en otro extremo del mundo indoeuropeo, entre los vikingos y su idea del Walhalla, como morada de los guerreros.

El italiano Tullio Ossana dedica la mayor parte de su libro La stretta di mano . Il contenuto etico della Religione di Mitra, -tras la correspondiente explicación de orígenes, difusión, estructura interna y ritos- precisamente a ese rasgo tan propio de la religión mitraica, sin duda una de sus principales activos a la hora de ganar adhesiones, que fue la elaboración de una ética propia de raíz guerrera. Esta ética tendría tres objetivos:

- Hacer del hombre un hombre consciente, maduro, comprometido, por lo tanto capaz de actuar según sus capacidades y de poner su vida en acción.

- El segundo objetivo sería entrar en armonía en el Cosmos y cumplir su gran misión de ser intermediario entre dioses y hombres, entre hombres y la creación.

-Ser parte del plan de Mitra, revelado a el por el Sol. Representar el orden divino allí donde esté presente, con las implicaciones escatológicas y de ultratumba que ello implicaría.

Habría, según F. Cumont (30) una especie de decálogo que la religión mitraíca trazaría para que cada uno de sus adeptos fuese capaz de llegar a cumplir los tres objetivos mencionados. Cumont no llega a explicitar dicho decálogo, pero Tulio Ossana sí que nos da pistas para poder hacernos una certera idea de en qué podría haber consistido.

-Ética de la luz. Indicando el aporte de la inteligencia a la acción, la sabiduría en toda realización y la fidelidad a la verdad y a la palabra dada.

- Ética de la espada, como símbolo trascendente de la fuerza física, de la que queda excluido su uso prepotente e irracional.

-Ética de la transformación -preferimos este término al de «progreso» utilizado por T. Ossana-. En la acción de Mitra y sus iniciados existe una evidente transformación cuyo objetivo final es la transformación y la gloria.

-Ética de la amistad. Que liga a los adeptos con Mitra -el amigo- y a los adeptos entre sí en una fraternidad guerrera: la militia Mithrae.

Ética del servicio. Mitra, ejemplo de sus adeptos, pone su superioridad al servicio de la lucha por el bien y el orden. Rechazando cualquier pasividad (auto)-contemplativa.

Ética de la salvación. El fiel, salvado por el conocimiento de Mitra, se empeña en la salvación de sus hermanos, como éstos debe entenderse sólo a los miembros de la militia Mithrae.

Ética de la acción. La ética mitraica despierta al hombre a la acción, que estará en relación con sus capacidades interiores innatas que ahora debe poner a actuar.

Ética de la lucha contra el mal. Recordemos la visión dualista del mitraismo y su implícita obligatoriedad para luchar activa y firmemente frente al mal representado por Ahrimán.

Ética de la jerarquía-también aquí preferimos este término que los utilizados por T Ossana: orden y obediencia-. Evidentemente se refiere a la obediencia de los grados inferiores hacia los superiores.

Si hay un gesto que resume visualmente todo el contenido ético del que estamos hablando es la destrarum iunctio o dexiosis que convierte a los mitraístas en syndexioi (literalmente «unidos por la mano derecha»). En las civilizaciones arcaicas la mano se considera como un centro de potencia y un punto de focalización de energía (31), especialmente la derecha se ha relacionado con las capacidades creativas y guerreras del hombre. En el zazen la derecha es considerada la mano masculina o yang, en el típico mudra que se utiliza durante la meditación, ésta protege a la izquierda considerada como la femenina o yin. Así el gesto de unir las manos derechas alude tanto a la comunidad de camaradería que era la milicia mitraica como al hecho de abrir circuitos sutiles de energía que circularían entre todos los miembros de la misma, no lejano es el simbolismo de la cadena de algunas sociedades medievales iniciáticas e incorporado-una vez «desactivado» como es típico de esta institución-por la masonería.

Siguiendo estos preceptos éticos el adepto mitraista alcanzaba una serie de virtudes que, al parecer realmente, fueron características propias de los miembros de la militia mitraica a lo largo de su existencia: coherencia interna y externa, fidelidad, disponibilidad, coraje, humildad y alegría, entendida como plenitud. Lo que ayudó mucho a que las autoridades romanas vieran en el mitraísmo una religión que aportaba buenos ciudadanos siempre dispuestos a la defensa del Imperio.

El dualismo también condicionó las creencias escatológicas de los mitraístas. La oposición entre cielo e infierno continuaba en la existencia de ultratumba. Mitra también es el antagonista de los poderes infernales y asegura la salvación de sus protegidos en el más allá. Según el profesor Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, el alma se someterá a un juicio presidido por Mitra si sus méritos pasados en la balanza del dios, son mayores que los fallos, él lo defenderá frente a los agentes de Ahrimán, que tratarán de llevarla a los abismos infernales. Las almas de los justos se van a habitar a la Luz infinita, que se extiende por encima de las estrellas, se despojan de toda sensualidad y codicia al pasar a través de las esferas planetarias y de este modo se convierten en tan puras como las de los dioses, que serán, en adelante, sus compañeros. Al final de los tiempos, resucitará a todos los hombres y dará a los buenos un maravilloso brebaje que les garantizará la inmortalidad definitiva, mientras que los malos serán aniquilados por el fuego junto al propio Ahrimán.

El mitraísmo fue el culto mistérico que ofreció un sistema más rico, fue el que alcanzó una mayor elevación espiritual y ética, ninguno de ellos atrajo tantas mentes ni tantos corazones. El mazdeísmo mitráico fue una especie de religión de Estado del Imperio romano en el siglo III, de ahí la conocida frase de Renán: «si el cristianismo se hubiese detenido en su crecimiento por alguna enfermedad mortal, el mundo hubiera sido mitraísta».

EL MITRAÍSMO EN EL IMPERIO ROMANO.

Expansión y relación con el poder.

Es en el siglo I d. C. cuando el mitraísmo se instala en la Urbs romana, desde un primer momento, lo hace en círculos cercanos al imperial. La representación más antigua del dios sacrificando al toro data del año 102 bajo el reinado de Trajano. Fuera del Lacio es Etruria meridional la zona con mayor número de mitreos, siendo Campania y la Cisalpina dos importantes zonas de penetración.

La difusión del rito mitraísta se manifiesta en Retia y especialmente en Nórica. En el reinado de Adriano, poco antes de 130, llega a Germania, y con Antonino Pío hasta la Panonia. Desde la época de Marco Aurelio hasta los Severos -es decir entre 161-235- los santuarios se suceden a ambos lados del Rin y en las provincias danubianas, siendo también frecuentes en Tracia y Dalmacia, mucho menos en Macedonia y Grecia, donde solo tenemos noticia de un mitreo cercano a Eleusis que había sido consagrado por legionarios claramente itálicos. El Asia helenizada fue muy refractaria a este culto. Por el contrario sí hay constatación de templos consagrados a Mitra en Capadocia, en el Ponto, en Frigia, en Lidia y en Cilicia, cerca del mar Negro hay restos arqueológicos en Crimea, donde habría penetrado desde Trevisonda. También se han encontrado en Siria y en el Eúfrates, casi siempre relacionados con campamentos de legionarios, lo mismo que en Egipto.

A finales del siglo II su culto alcanza la cúpula de la jerarquía militar imperial e incluso hay emperadores que se hacen iniciar en estos misterios. El caso de Nerón es aún dudoso, M. Yourcenar en sus célebres Memorias de Adriano, da el dato de este emperador hispano, pero del primer emperador que hay constancia cierta es de Cómodo que habilitó una dependencia subterránea de la residencia imperial de Ostia para la práctica de este culto. También es claro el caso de Séptimo Severo, por el contrario, el emperador oriental y orientalizante Caracalla tuvo como dios a Serapis. La primera mención clara, pública y oficial en la que Galeno, Diocleciano y Licinio, en 307 califican al dios de fautor imperii sui (protector de su poder), el primero de ellos fue, sin duda, adepto al culto de Mitra. Mucho se ha dicho, en este sentido, sobre Juliano el Apóstata, aunque la única prueba concreta de la que se tiene constancia es la mención a Mitra en su Banquete de los Césares, emperador que ha pasado a la historia con el sobrenombre despectivo del Apóstata, aunque otros, con mejor criterio se refieren a Juliano Flavio, como Juliano Emperador (32), «porque en rigor si alguien debe ser llamado "apóstata" debería ser el caso de los que abandonaron las tradiciones sacras y los cultos hacedores del alma y la grandeza de la Roma antigua(...) no debería ser, por el contrario, el caso de quien tuvo el coraje de ser tradicional y de intentar reafirmar el ideal "solar" y sacro del Imperio, como fue el intento de Juliano Flavio» (33).

Mitra tuvo numerosos fieles en el orden senatorial de la Urbs. El medio urbano es, a lo largo y ancho de todo el Imperio, el más propicio para el culto mitraico y donde se encuentra a sus seguidores y adeptos, el medio rural, mucho más conservador, lo rechazó claramente, como posteriormente haría con el cristianismo (34). Socialmente vemos que está presente «en su fase más antigua, entre siervos y libertos, posteriormente, en el curso del siglo II, en el estamento militar. Se difunde, a lo largo del siglo III, en el ordo equester y en el siglo IV en el senatorial»(35). El hecho de que al principio fueran siervos y libertos habla claramente de la gran tolerancia religiosa del mundo romano y de sus clases dirigentes, otro ejemplo curioso es que está datada la existencia de un pater mitraísta que a la vez era sacerdos de la domus Augusta, evidenciando la postura oficial de tolerancia y reconocimiento hacia el culto mitraico. En general las inscripciones del siglo III-IV revelan la gran importancia que tuvo el componente militar en la composición de los adeptos de Mitra y en su difusión por el Imperio.

El culto a Mitra en Hispania

En cuanto a la presencia del mitraismo en la península ibérica, según García y Bellido es, de los cultos mistéricos practicados en la Antigüedad, el que menos representado está arqueológicamente. Hispania es el país de Europa occidental más pobre en restos mitraicos. La explicación es bastante sencilla, el culto a Mitra estuvo íntimamente relacionado con el movimiento y el asentamiento de las legiones, e Hispania en los siglos II y III, época de expansión y culto, vive una existencia bastante pacífica y al margen del movimiento de tropas, tan frecuente en otras partes del Imperio, y por tanto al margen de las vías de penetración del mitraísmo (36).

Testimonios arqueológicos de presencia mitraica hay en las antiguas tres provincias de la Hispania de época imperial, siempre en zonas periféricas de la Meseta. En el Tarraconense hay ejemplos en sus dos extremos: la zona noroeste y el territorio astur y centros urbanos del litoral mediterráneo, como Barcino, Tarraco, Cabrera del Mar y, en la Comunidad de Valencia hay atestiguada una inscripción encontrada en 1922, en la localidad de Benifayó, en un lugar donde se han encontrado varios restos romanos. El epígrafe allí encontrado, tiene 65 cm de altura y se conserva en el Museo Provincial de Valencia. El texto dice:

Invicto/Mithrae/Lucanus/Ser(vus)

En Lusitania los restos arqueológicos están esparcidos por todo el territorio, pero indudablemente el centro principal e irradiador del mitraísmo estuvo en Emerita Augusta. Para la Bética la zona de hallazgos corresponde a la zona interior: Itálica, Corduba, Munda e Igagrum (actual Capra), donde se encontró una gran estatua de Mitra tauróctono, con Mitra vestido con pantalón persa, túnica con mangas y gorro frigio (37), exceptuando algún dato en la ciudad portuaria de Malaca.

«En general, el material que disponemos, procede de capitales de provincias, conventus, de colonias y municipios, es decir de zonas fuertemente romanizadas, donde hubo arraigo municipal. Fueron al mismo tiempo ciudades portuarias, administrativas o militares, asiento de soldados y comerciantes que transportaron el culto en su bagaje» (38). Siendo indudablemente el elemento militar el numéricamente más importante entre los adeptos al mitraísmo y el que ejerce principalmente la función de difusor por el territorio hispano. Otra vía fueron los comerciantes llegados a puertos del Mediterráneo hispánico.

FINAL Y PERVIVENCIAS DE UN CULTO GUERRERO

El fin del mitraísmo.

Al no incluir mujeres entre sus adeptos el mitraísmo limitó su campo de crecimiento y se encontró en desventaja frente a otros cultos como por ejemplo el cristianismo. Su segundo problema fue que siempre conservó la «marca persa» y Persia nunca se integró en el imperio, siendo por el contrario, enemigo hereditario y amenaza constante.

Constantino, el primer emperador cristiano, manifestó una particular hostilidad hacia el mitraísmo, así en 324 prohibió expresamente el sacrificio a «ídolos» y la celebración de cultos mistéricos. El rito mitraico tenía circunstancias agravantes: el sacrificio terminaba con un banquete con el dios y los emperadores cristianos tenían presentes las palabras de Pablo en su I carta a los corintios: «No quiero que entréis en comunión con los demonios». La legislación se hace más dura en el siglo IV cuando se prohíbe cualquier sacrificio nocturno, precisamente la hora del ritual mitraico. El culto mitraico está en decadencia cuando Constancio II en 357 llega a Roma, circunstancia que aprovecha la aristocracia senatorial para obligarle a recortar las «leyes antipaganas», el reinado de Juliano el Apóstata (361-363) reactiva los cultos paganos, y de forma muy clara al mitraico, pero esta tendencia dura poco, en 391 una ley prohíbe toda clase de culto o manifestación pagana, y en 394 el mitraísmo desaparecerá de la Urbs, en el resto del Imperio las dos últimas dedicatorias epigráficas a Mitra tendrían fecha de 325 y 367.

Influencias y permanencias mitraicas en el cristianismo.

Sin embargo hay testimonios que indican que, aún después de la destrucción de los mitreos, la vitalidad de culto permaneció durante largo tiempo. Es lógico inferir que continuó teniendo influencia en importantes capas de la sociedad, y que el cristianismo- nuevo culto dominante-recogió y adaptó muchos de sus temas e iconografías:

La influencia más evidente históricamente confirmadas del culto solar sobre el cristianismo en el Imperio tardío es la elección del 25 de Diciembre como la del nacimiento de Cristo, es decir la misma fecha que Aureliano consagró en 274 al Natalis Sol Invicti, fecha que también era celebrada por los mitraistas, que no dejaban de ser un culto solar particular.

Trascendente fue también el cambio del sábado al domingo como «día del Señor», lo que se explica al renunciar al calendario lunar semita y adoptar el solar en que el domingo (día del sol = Sunday en inglés, Sonntag en alemán) da comienzo a la semana.

También hubo influencia mitraica directa en los rituales comunitarios, es de resaltar la afinidad entre el ritual de consagración mitraica y los sacramentos cristianos del bautizo, comunión y confirmación, sacramentos que entre ellos no serán autónomos hasta el siglo XI. Según expresión de Santo Tomás de Aquino el bautizado se convierte en «soldado de Cristo» lo que nos recuerda claramente a la idea al adepto como miembro de la «milicia de Mitra», y en la comunión se da la idea espiritual de «luchar contra los enemigos de la fe», en el mismo sentido del culto mitraico.

Por otro lado resulta llamativo que los cristianos conservaran el nombre de pater para sus sacerdotes y que los obispos sigan llevando un gorro que recibe el nombre de mitra. No lo es menos la imagen del Arcángel San Miguel con la espada en la mano para matar al dragón que puede recordarnos a la imagen de Mitra, puñal en mano matando al toro; en ambos casos estaríamos ante la imagen de «la lucha victoriosa de una figura trascendente contra una bestia que primero es domada y luego sacrificada» (39).

Otra influencia irania y zoroástrica, aunque no es definitivo que sea también mitraica, es la adoración de los Reyes Magos. Herodoto define a los « magos» como una casta sacerdotal irania que ejercía su función primero entre los medas y luego entre los persas. Los regalos que le llevan tienen un claro simbolismo tradicional: el oro siempre ha sido símbolo del sol y, en consecuencia de la realeza, que es la representación en la tierra de lo que el sol es en el sistema solar, precisamente Melchor regala oro por tratarse de un rey, Gaspar incienso por ser un dios y Baltasar mirra por ser un hombre. Siguiendo con los Magos que visitan a Jesucristo recién nacido es obligatorio referirse a los cambios iconográficos que ha hecho la iglesia en su iconografía, mucho han variado desde la representación de los mosaicos de Rávena a la actualidad, en un primer momento son hombres de una misma edad e igualmente de raza blanca, es en el siglo XV cuando Petrus Natalibus establece arbitrariamente que Melchor tiene 60 años, Gaspar 40, y Baltasar 20. Durante la Edad media habían incorporado una iconografía alquímica, representando -por los atributos-cada uno de ellos una de las fases alquímicas: blanco/Melchor-rojo/Gaspar-negro/Baltasar/África, es desde esa fecha cuando se representa a Baltasar como un hombre «negro», en este caso nos negamos a decir: como un hombre «subsahariano».

¿Fue posible la supervivencia?

Es lógico pensar que una ley no fue suficiente para terminar de un plumazo con un culto tan extendido y con un gran número de adeptos cual fue el mitraísmo. Hay restos y testimonios dispersos que infieren la existencia de núcleos de resistencia mitraísta en el siglo V. En el siglo XX las obras de inspiración tradicional y evoliana se encargan de buscar restos aún vivos de tradiciones europeas precristianas, especialmente de la continuidad de la tradición romana y de pervivencias mitraicas. Así la revista Mos maiorum en un número de 1996(40) llega a afirmar que «el culto mistérico de Mitra, a consecuencia de la hostilidad del Estado, desaparece de la superficie de la historia, conservándose en una tradición oculta y operando invisiblemente sobre las grandes corrientes de la historia occidental. El resurgir de la sacralidad del Imperium en la tradición gibelina medieval, el trasfondo iniciático de los poemas épicos y caballerescos de la Edad Media, los vestigios de la tradición hermética hasta el Renacimiento y el renacimiento espiritual evidenciados en tiempos mucho más recientes, testimonian en modo vivo y concreto la continuidad de la fuerza de la herencia sapiencial pagana en Occidente».

También en Oriente se atestiguan presencia mitraica en épocas muy posteriores. En la tradición épica de Armenia hasta el siglo XIX se hace referencia a un gigante de nombre Mehr, cuya descripción y función nos recuerda llamativamente a la del dios Mitra.

Varios estudiosos - entre ellos Mircea Eliade (41) y Ellemire Zolla(42)- han dado certezas de la continuidad del culto zoroástrico en Irán hasta, por lo menos, los años 70 del siglo XX . En este sentido conocido es el hecho de que en 1.964, Mary Boyce visitó una serie de pueblos y aldeas iraníes en los que pervivía la fe en Zaratustra, constatando que veneraban a un dios-héroe llamado Mihr, con enormes paralelismos con Mitra. No se sabe cuál es actualmente la situación de estos parsis bajo el régimen integrista de Teherán. Nos tememos que están atravesando tiempos difíciles que amenazan la perpetuación de su religión, mantenida durante milenios.

También conocida es la comunidad parsi de Bombay, es el mismo E. Zolla quien en su libro Aure nos narra su encuentro con un adepto al mitraismo de esta comunidad, que le habla-desde el conocimiento operativo- de los ritos de la llamada «Cámara del Consejo» en el palacio de Darío, así como del poder y la efectividad de la misteriosa secuencia vocálica («mántrica» podríamos decir) del Ritual Mitraico del Gran Papiro Mágico de París(43), que incluye técnicas sobre el dominio de las corrientes de la respiración -cálida y fría - que es necesario armonizar , en mismo modo a cómo las técnicas yóguicas lo determinan .

No quisiéramos cerrar este apartado sin hacer mención de una curiosa e interesante entrevista(44) aparecida en el número 4- solsticio de verano 1994 de la revista belga Antaios , número titulado precisamente «Mysteria Mithrae», el entrevistado, se identifica con el nombre de Corax (el cuervo) primer grado de iniciación mitraica, y se define a sí mismo como «joven universitario europeo, me definiría a riesgo de pasar por un provocador , como un seguidor de Mitra, un fiel del Sol Invictus, en la línea espiritual de Akenatón, y del emperador Juliano llamado el Apóstata. Al igual que ellos, mi toma de conciencia solar fue resultado del reencuentro con una tradición y una búsqueda personal», si bien deja claro que «No pretendemos en absoluto, contrariamente a ciertos druidas modernos, ninguna filiación iniciática (aunque hayamos buscado durante años en vano esos "testigos")».

Más allá de supervivencias reales, imaginadas o deseadas hemos querido dar las claves del culto mitraico que no hace más que repetir el mundo de valores indoeuropeos. Si pretendemos un verdadero enderezamiento espiritual tendremos necesariamente que recuperarlos y remitirnos a ellos, sea cual sea la forma religiosa exterior que los englobe.

Enrique Ravello

Notas

--------

1 J. Evola, «La via della realizzazione di sé secondo i Misteri di Mitra»(1926) en La via della realizzazione di sé secondo i misteri di Mitra (recop). Quaderni di Testi Evoliani, nº 4. Fundazione Julius Evola . Roma, p.5.

2 J Varenne, Zoroastro. El profeta del Avesta. Ed Edaf, Madrid 1989, p,23.

3 Ibídem, p, 56.

4 A. Coomaraswamy, El Vedanta y la tradición occidental.

Ed. Siruela, Madrid 2001, p, 269.

5 Cfr: G Bonfante, «The Name of Mitra» en Etudes mitrhriaques (= Acta Iranica,17)-Teherán-Lieja,1978.p.47 y ss.

6 Sobre la realidad de la mitología romana como manifestación de la ideología indoeuropea, v. G Dumézil, Iupiter, Mars, Quirinus. Essai sur la conception indoeuropéene de la Societé et sur les origines de Rome, París 1944, y La religion romaine archaïque. París 1966.

7 S. Arcella I Misteridel Sole. Ed Controcorrente, Nápoles 2002, p.26.

8 S.S Hakim, «I misteri di Mitra visti da un zoroastriano», en Conoscenza religiosa I 1976.

9 Ibídem, p.87.

10 A. Loisy; Los misterios paganos y el misterio cristiano. Ed Paidos Oriental, Barcelona 1990,p.119.

11 F. Cumont , Las religiones orientales y el paganismo romano. Ed. Akal universitaria. Madrid 1987 p.129.

12 Ibídem, p. 121.

13 J. Evola, «Note sui Misteridi Mithra» en op.cit. (recop) p.18.

14 David Ulansey, profesor de Filosofía y Religión en el Californian Institute of Integral Studies.

15 D. Ulansey, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries. Cosmology & Salvation in the Ancient World. Ed Oxford University Press. Nueva York 1989.

16 R. Turcan, op.cit, p.103.

17 Eliade, M y Couliano, I. P, Diccionario de las religiones. Circulo de lectores. Ed. Paidós, Barcelona 1997.

18 A. Loisy: op, cit, p.129

19 T. Ossana, La stretta di mano. Il contenuto etico della Religione di Mitra. Ed Borla, Nápoles 1988.

20 S. Arcella , I Misterio del Sole. Ed. Controcorrente, Nápoles2002,p.119.

21 R.Turcan, Mithra et le Mithriacisme .Ed. Les Belles Lettres . París 2000, p.119

22 R. Turcan.op.cit,p.90.

23 S. Arcella, op.cit,p.134.

24 A. Loisy, op.cit, p.129-135.

25 J. Evola,op.cit, p.5

26 S. Arcella,op.cit,p.102

27 J. Evola ,op.cit, p.7

28 J Evola «Note sui Misteri di Mithra » (1950).op.cit (recop) p.19.

29 J Evola ,«La via della realizzazione di sé secondo i Misteri di Mitra» (1926).Recogido en op. cit (recop.) Fundazione Julius Evola. Roma.p.7

30 F. Cumont, Le religione orientali nel paganesimo romano, Bari 1967, p.183 y Les mystéres de Mitra, Bruselas 1919, p.141.

31 Técnicas autocurativas japonesas como el reiki o el katsugen se basan principalmente en esto.

32 Cfr: R. Prati en la traducción al italiano de los escritos de Juliano Imperador con el título: Sugli dei e sugli uomini.

33 J. Evola «Giuliano Imperatore» (1932) en op.cit. (recop.) p.15.

34 R. Turcan ,op. cit, pp.41-43

35 S. Arcella .«I collegi mithraici nella Roma imperiale», en Arthos nº 9 (nueva serie) , 2001.

36 A. García y Bellido. Les religiones orientales dan l Éspagne romaine. Leiden1967, p.21.

37 Cfr JL Jiménez y M. Martín- Bueno, La casa del Mithra, Capra-Córdoba. Ilmo.Ayto de Cabra 1992.

38 Mª Antonia de Francisco Casado, El culto de Mitra en Hispania. Ed Universidad de Granada. Granada 1989. p.64.

39 S. Arcella, op.cit p. 211.

40 Mos maiorum, Revista trimestrale di Studi tradizionali. Año II, nº4,1996,pp.34.

41 M. Eliade, Storia, pp.338-344.

42 E. Zolla, Il Signore delle grotte, pp.64 y ss.

43 Para un mayor conocimiento sobre la realidad, potencialidad y operatividad del Gran Papiro Mágico de París, cfr: «Apathanatismos. Rituale Mithraico del Gran Papiro Magico di Parigi» en , Grupo UR, Introduzione alla Magia . Vol I . Ed Mediterranee, Roma 1971.pp.114-139.

44 «Corax, entretien avec un adepte du culte socaire» en Antaios nº4, solsticio de verano de 1994, Bruselas.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

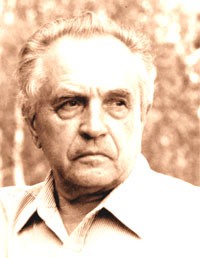

Students and observers of communism consistently encounter the same paradox: On the one hand they attempt to predict the future of communism, yet on the other they must regularly face up to a system that appears unusually static. At Academic gatherings and seminars, and in scholarly treatises, one often hears and reads that communist systems are marred by economic troubles, power sclerosis, ethnic upheavals, and that it is only a matter of time before communism disintegrates. Numerous authors and observers assert that communist systems are maintained in power by the highly secretive nomenklatura, which consists of party potentates who are intensely disliked by the entire civil society. In addition, a growing number of authors argue that with the so-called economic linkages to Western economies, communist systems will eventually sway into the orbit of liberal democracies, or change their legal structure to the point where ideological differences between liberalism and communism will become almost negligible.

Students and observers of communism consistently encounter the same paradox: On the one hand they attempt to predict the future of communism, yet on the other they must regularly face up to a system that appears unusually static. At Academic gatherings and seminars, and in scholarly treatises, one often hears and reads that communist systems are marred by economic troubles, power sclerosis, ethnic upheavals, and that it is only a matter of time before communism disintegrates. Numerous authors and observers assert that communist systems are maintained in power by the highly secretive nomenklatura, which consists of party potentates who are intensely disliked by the entire civil society. In addition, a growing number of authors argue that with the so-called economic linkages to Western economies, communist systems will eventually sway into the orbit of liberal democracies, or change their legal structure to the point where ideological differences between liberalism and communism will become almost negligible.  Zinoviev refutes the widespread belief that communist power is vested only among party officials, or the so-called nomenklatura. As dismal as the reality of communism is, the system must be understood as a way of life shared by millions of government official, workers, and countless ordinary people scattered in their basic working units, whose chief function is to operate as protective pillars of the society. Crucial to the stability of the communist system is the blending of the party and the people into one whole, and as Zinoviev observes, “the Soviet saying the party and the people are one and the same, is not just a propagandistic password.” The Communist Party is only the repository of an ideology whose purpose is not only to further the objectives of the party members, but primarily to serve as the operating philosophical principle governing social conduct. Zinoviev remarks that Catholicism in the earlier centuries not only served the Pope and clergy; it also provided a pattern of social behavior countless individuals irrespective of their personal feelings toward Christian dogma. Contrary to the assumption of liberal theorists, in communist societies the cleavage between the people and the party is almost nonexistent since rank-and-file party members are recruited from all walks of life and not just from one specific social stratum. To speculate therefore about a hypothetical line that divides the rulers from the ruled, writes Zinoviev in his usual paradoxical tone, is like comparing how “a disemboweled and carved out animal, destined for gastronomic purposes, differs from its original biological whole.”

Zinoviev refutes the widespread belief that communist power is vested only among party officials, or the so-called nomenklatura. As dismal as the reality of communism is, the system must be understood as a way of life shared by millions of government official, workers, and countless ordinary people scattered in their basic working units, whose chief function is to operate as protective pillars of the society. Crucial to the stability of the communist system is the blending of the party and the people into one whole, and as Zinoviev observes, “the Soviet saying the party and the people are one and the same, is not just a propagandistic password.” The Communist Party is only the repository of an ideology whose purpose is not only to further the objectives of the party members, but primarily to serve as the operating philosophical principle governing social conduct. Zinoviev remarks that Catholicism in the earlier centuries not only served the Pope and clergy; it also provided a pattern of social behavior countless individuals irrespective of their personal feelings toward Christian dogma. Contrary to the assumption of liberal theorists, in communist societies the cleavage between the people and the party is almost nonexistent since rank-and-file party members are recruited from all walks of life and not just from one specific social stratum. To speculate therefore about a hypothetical line that divides the rulers from the ruled, writes Zinoviev in his usual paradoxical tone, is like comparing how “a disemboweled and carved out animal, destined for gastronomic purposes, differs from its original biological whole.”  Hebben we daar niet allemaal baat bij gehad?

Hebben we daar niet allemaal baat bij gehad?

Há um outro ponto fundamental a sublinhar: é difícil adotar a ciência e a técnica circunscrevendo-as dentro dos limites materiais e como instrumentos de uma civilização; ao revés, é praticamente inevitável que empapem-se da concepção do mundo sobre que baseia-se a moderna ciência profana, concepção praticamente inculcada em nossos espíritos pelos métodos de instrução habitual que tem, sobre o plano espiritual, um efeito destrutivo. O conceito mesmo do verdadeiro conhecimento vem assim a ser falseado totalmente.

Há um outro ponto fundamental a sublinhar: é difícil adotar a ciência e a técnica circunscrevendo-as dentro dos limites materiais e como instrumentos de uma civilização; ao revés, é praticamente inevitável que empapem-se da concepção do mundo sobre que baseia-se a moderna ciência profana, concepção praticamente inculcada em nossos espíritos pelos métodos de instrução habitual que tem, sobre o plano espiritual, um efeito destrutivo. O conceito mesmo do verdadeiro conhecimento vem assim a ser falseado totalmente. Um "Reich Europeu", não uma "Nação Européia", seria a única fórmula aceitável desde o ponto de vista tradicional para a realização de uma unificação autêntica e orgânica da Europa. Quanto à possibilidade de realizar a unidade européia desse modo, não posso não ser pessimista pelas mesmas razões que induziram-me a dizer que hoje, há pouco espaço para um renascimento do "guibelinismo": não há um ponto de referência superior, não existe um fundamento para dar solidez e legitimidade a um princípio de autoridade supranacional. Não pode-se em efeito descuidar deste ponto fundamental e conformar-se em recorrer à "solidariedade ativa" dos europeus contra as potências antieuropéias, passando por cima das divergências ideológicas. Inclusive quando chegara-se, com este método pragmático, a fazer da Europa uma unidade, sempre existiria o perigo de ver nascer, nesta Europa, novas contradições desagregadoras, em particular no que concerne às divergências ideológicas e e as causadas pela falta de um princípio de autoridade superior. Hoje é difícil falar de uma "cultura comum européia": a cultura moderna não conhece fronteiras; a Europa importa e exporta "bens culturais"; não somente no domínio da cultura, senão também no domínio do modo de vida, manifesta cada vez mais uma nivelação geral que, conjugada com a nivelação produzida pela ciência e pela técnica, providencia argumentos não aos que querem uma Europa unitária, senão aos que desejariam edificar um Estado mundial. Novamente, nos deparamos com o obstáculo constituído pela inexistência de uma verdadeira idéia superior diferenciadora, que deveria ser o núcleo do império europeu. Mais além de tudo isto, o clima geral é desfavorável: o estado espiritual de devoção, de heroísmo, de fidelidade, de honra na unidade, que deveria servir de cimento ao sistema orgânico de uma Ordem européia imperial é hoje, por assim dizer, inexistente. O primeiro a fazer deveria ser uma purificação sistemática dos espíritos, antidemocráta e antimarxista, nas nações européias. Sucessivamente, far-se-ia necessário poder sacudir as grandes massas de nossos povos com meios diferentes, seja recorrendo aos interesses materiais, seja com uma ação de caráter demagógico e fanático, que necessariamente, influiria na capa subpessoal e irracional do homem. Estes meios implicariam fatalmente certos riscos. Porém todos estes problemas são extremadamente difíceis de solucionar na prática; por outra parte, já tive ocasião de falar disso em um de meus livros, Homens Entre as Ruínas.

Um "Reich Europeu", não uma "Nação Européia", seria a única fórmula aceitável desde o ponto de vista tradicional para a realização de uma unificação autêntica e orgânica da Europa. Quanto à possibilidade de realizar a unidade européia desse modo, não posso não ser pessimista pelas mesmas razões que induziram-me a dizer que hoje, há pouco espaço para um renascimento do "guibelinismo": não há um ponto de referência superior, não existe um fundamento para dar solidez e legitimidade a um princípio de autoridade supranacional. Não pode-se em efeito descuidar deste ponto fundamental e conformar-se em recorrer à "solidariedade ativa" dos europeus contra as potências antieuropéias, passando por cima das divergências ideológicas. Inclusive quando chegara-se, com este método pragmático, a fazer da Europa uma unidade, sempre existiria o perigo de ver nascer, nesta Europa, novas contradições desagregadoras, em particular no que concerne às divergências ideológicas e e as causadas pela falta de um princípio de autoridade superior. Hoje é difícil falar de uma "cultura comum européia": a cultura moderna não conhece fronteiras; a Europa importa e exporta "bens culturais"; não somente no domínio da cultura, senão também no domínio do modo de vida, manifesta cada vez mais uma nivelação geral que, conjugada com a nivelação produzida pela ciência e pela técnica, providencia argumentos não aos que querem uma Europa unitária, senão aos que desejariam edificar um Estado mundial. Novamente, nos deparamos com o obstáculo constituído pela inexistência de uma verdadeira idéia superior diferenciadora, que deveria ser o núcleo do império europeu. Mais além de tudo isto, o clima geral é desfavorável: o estado espiritual de devoção, de heroísmo, de fidelidade, de honra na unidade, que deveria servir de cimento ao sistema orgânico de uma Ordem européia imperial é hoje, por assim dizer, inexistente. O primeiro a fazer deveria ser uma purificação sistemática dos espíritos, antidemocráta e antimarxista, nas nações européias. Sucessivamente, far-se-ia necessário poder sacudir as grandes massas de nossos povos com meios diferentes, seja recorrendo aos interesses materiais, seja com uma ação de caráter demagógico e fanático, que necessariamente, influiria na capa subpessoal e irracional do homem. Estes meios implicariam fatalmente certos riscos. Porém todos estes problemas são extremadamente difíceis de solucionar na prática; por outra parte, já tive ocasião de falar disso em um de meus livros, Homens Entre as Ruínas.

Since 1945 Western nations have witnessed a dramatic reduction in the variety of positions in political theory and jurisprudence. Political argument has been virtually reduced to contests within liberal-democratic theory. Even radicals now take representative democracy as their unquestioned point of departure. There are, of course, some benefits following from this restriction of political debate. Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist political ideologies are now beyond the pale. But the hegemony of liberal-democratic political agreement tends to obscure the fact that we are thinking in terms which were already obsolete at the end of the nineteenth century.

Since 1945 Western nations have witnessed a dramatic reduction in the variety of positions in political theory and jurisprudence. Political argument has been virtually reduced to contests within liberal-democratic theory. Even radicals now take representative democracy as their unquestioned point of departure. There are, of course, some benefits following from this restriction of political debate. Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist political ideologies are now beyond the pale. But the hegemony of liberal-democratic political agreement tends to obscure the fact that we are thinking in terms which were already obsolete at the end of the nineteenth century.