mardi, 01 avril 2014

Art contemporain et Etat culturel...

Art contemporain et Etat culturel...

Ex: http://metapoinfos.hautetfort.com

Nous reproduisons ci-dessous un entretien avec Aude de Kerros, cueilli sur Contrepoint et consacré à l'art contemporain, un "art" très largement subventionné en France...

Aude de Kerros est l'auteur de plusieurs essais consacré à la question de l'art, comme L'art caché - Les dissidents de l'art contemporain (Eyrolles, 2007), Sacré Art Contemporain (Jean-Cyrille Godefroy, 2012) ou 1983-2013 Années noires de la peinture (Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, 2013), avec Marie Sallantin et Pierre-Marie Ziegler.

Aude De Kerros : « L’Etat culturel a détruit la création française »

Qu’est-ce que l’art contemporain ? Quelle est sa caractéristique principale ?

L’art contemporain est une forme de création centrée, contrairement à l’art, sur le concept. Depuis les années 60 il a connu plusieurs métamorphoses Aujourd’hui l’AC veut être une expression de la mondialisation. Pour cela il doit être hyper-visible et rentable. Ainsi l’artiste d’AC1 est devenu un concepteur d’objets, mis en forme par des designers, fabriqués en « factory », sous différents formats et en nombres adaptés aux stratégies de diffusion. Ces objets sont conçus pour habiter tous les circuits de consécration, de l’espace urbain au musée et à la galerie. Cette adaptabilité à chaque lieu assure sa visibilité et sa vente. L’objet destiné aux Institutions et au grand collectionneur rapporte souvent moins que la vente de tous les produits dérivés et des droits sur l’image. Aujourd’hui l’AC fonctionne comme un produit financier composite, fondé sur un produit manufacturé sur mesure. Ce produit financier voit fabriquer sa valeur en réseau dont le centre est le grand collectionneur et ses amis. Ce système fonctionne comme un trust et une entente réunis. Il satellise marchands, salle des ventes, institutions et médias. Son privilège sur les autres marchés financiers est de ne pas être régulé.

Sur quelles structures repose l’art contemporain ?

La consécration de « l’art » se faisait lentement par la reconnaissance des pairs, des amateurs et d’un marchand. « L’art contemporain » a changé la donne, sa valorisation se fait en réseau. Au début des années 60, la consécration devient rapide grâce à des réseaux centrés autour de grandes galeries qui lancent un nom en deux ans. A partir de la fin des années 90 c’est autour des grands collectionneurs que se fabrique la valeur, cette fois-ci en réseau fermé. Il faut y appartenir pour collectionner sans risques mais pour ce faire il faut une fortune hors normes. Le marché de l’AC comprend un deuxième cercle de « suiveurs », collectionneurs solitaires qui ont les moyens de « se faire plaisir ». Ils se veulent découvreurs, à leurs risques et périls d’artistes « émergeants » encore accessibles parce que non cooptés par le premier cercle. Grâce à cela, ils côtoient le monde prestigieux des grandes fortunes internationales. Certains manifestent ainsi leur candidature à entrer dans la cour des grands.

Le troisième cercle, celui des « innocents » appartiennent à ceux qui croient en l’AC comme on croit à une religion. Ils pratiquent le culte en achetant l’œuvre d’artistes candidats à l’émergence.

Comment expliquer que c’est l’art contemporain qui est devenu cette clé d’accès ? Qu’est-ce qui le caractérise ?

C’est un art visuel accessible au-delà des langues et des cultures car il a adopté les images de la grande consommation culturelle, dite « mainstream ». L’AC a capté les codes des marques internationales, du pop, de toutes les représentations partagées d’un bout de la planète à l’autre. L’AC acquiert ainsi un pouvoir fédérateur grâce à ce langage minimum, non verbal. C’est une communion dans le presque rien. Son contenu est souvent critique, nihiliste et dérisoire, il permet un consensus négatif et passe ainsi par dessus les obstacles liés à la foi religieuse, aux goûts culturels, à l’attachement national, aux convictions intellectuelles et politiques.

Mais pourquoi ce réseau s’est-il structuré autour d’un art ? Après tout, les associations de riches ne sont pas récentes…

Après la chute du mur de Berlin et la fin de la guerre froide culturelle, l’AC a été « reprogrammé ». Il est devenu à la fois produit financier, industrie culturelle, divertissement planétaire. Il a été le prétexte le plus adapté d’évènements et de fêtes destinées à une hyper-classe internationale liée par des intérêts d’argent. Lieux de rencontre aux quatre coins du monde, occasions périodiques, sans qu’aucune idée commune ne soit nécessaire à partager… Quoi rêver de mieux ? En résumé l’art contemporain, c’est le réseau social des très riches.

Pour autant, lorsque l’on regarde la nouvelle génération d’entrepreneurs (Marc Zuckerberg, Elon, Musk, Richard Bronson, Jeff Bezos et en France Xavier Niel), semble-t-elle répondre aux mêmes codes comportementaux ? N’y a-t-il pas chez eux un rejet de ce type de réseau ?

Il m’est difficile de juger ces personnes, il faudrait que je les connaisse mieux. Cependant je constate que l’hégémonie culturelle américaine en vigueur depuis la chute du mur de Berlin, se trouve confrontée à une résistance de plus en plus forte de la part des pays émergents qui ont l’ambition de développer leur singularité culturelle. Si l’Amérique défend « le multiculturalisme dans tous les pays », les pays qui ont les moyens financiers souhaitent créer leurs propres industries culturelles et exprimer leur identité sur leur propre sol et rayonner au-delà en particulier auprès des pays du même « bassin culturel ».

Dans votre livre vous expliquez qu’il y a un problème spécifiquement français. Pouvez-vous nous expliquer ce dont il s’agit ?

Marie Sallantin, Pierre Marie Ziegler et moi-même avons décrit, dans « 1983-2013 – Les Années Noires de la Peinture – Une mise à mort bureaucratique ? » 2, le système si particulier qui régit l’art en France. Nous avons évoqué avec précision le domaine des arts plastiques mais il n’en demeure pas moins que l’interventionnisme radical est aussi appliqué dans les autres domaines de l’art.

La situation actuelle est le résultat d’une longue histoire qui a mis la France au cœur de la guerre froide culturelle après la 2ème guerre mondiale. Son pouvoir de référence et son prestige devaient disparaître au profit des deux grandes puissances en conflit. L’Amérique a gagné cette guerre en faisant de New York la place de consécration financière de l’art dans le monde et en rendant obsolète toute autre forme de consécration.

En France à partir de 1983, le Ministère de la Culture se transforme en Ministère de la création. En l’espace de trois mois sont créées des institutions bureaucratiques dotées d’un budget conséquent qui vont permettre l’encadrement de la vie artistique.

Pendant trente ans, cette administration, grâce à l’action d’un nouveau corps de fonctionnaires : les « inspecteurs de la création », a dit promouvoir un art d’avant-garde, révolutionnaire, d’essence conceptuelle. En réalité ces « experts » ont dépensé, pendant 30 ans, 60% du budget destiné à acheter des œuvres à des artistes vivants, à New York, dans des galeries newyorkaises, d’artistes « vivant et travaillant à New York ». Ainsi mourut la place de Paris.

Pourquoi cette exclusion de la peinture ?

La peinture, la sculpture, la gravure, ne surgissent pas de nulle part, elles sont la suite d’une longue histoire. C’est vrai de tous les lieux qui ont produit un grand art. L’exception française réside en ce que tous les moments de la peinture y ont été reçus et assimilés… un avenir de la peinture y est donc possible.

La direction étatique de la création en France, cas unique dans un Etat non totalitaire, a eu pour conséquence l’existence d’un art officiel. L’administration a fait le choix exclusif du conceptualisme et a donc rejeté de façon systématique la peinture, comme n’allant pas « dans le sens de l’Histoire ». En peu de temps l’Etat est devenu le seul réseau de consécration en France. Il a satellisé grands médias, université et quelques collectionneurs, mécènes et galeries. Ce qui est surprenant c’est que la peinture n’a pas été simplement exclue mais diabolisée. Nous en apportons la preuve dans les « Années Noires ». La conséquence a été que les marchands du secteur privé n’ont pas pu supporter la concurrence déloyale de l’Etat. L’invisibilité médiatique, la disparition des commandes et achats de l’Etat ajoutés à la condamnation officielle de la peinture ont rendu toute consécration impossible par des circuits privés.

Pour que l’art conceptuel puisse être « le seul art contemporain » il fallait que la peinture disparaisse. Pour que cela soit définitif, l’administration a interrompu la transmission du grand métier, en changeant le contenu des enseignements des Ecoles d’Art dépendant de l’Etat,

En 1983 l’Etat français a nationalisé banques et assurances mais a échoué dans sa tentative de monopole de l’éducation en raison d’un soulèvement populaire. La « nationalisation » de l’Art a eu lieu sans provoquer une telle indignation. Aujourd’hui le conformisme de droite et de gauche s’en accommode. Il est vrai que les médias ont occulté systématiquement tout débat sur ce sujet pendant trente ans (exception faite entre novembre 1996 et mai 1997). Les élites françaises sont peu intéressées par ce sujet dont ils ne comprennent pas les tenants et aboutissants et en ignorent l’Histoire.

Les banques et les sociétés d’assurance ont été re-privatisées mais l’art est resté en France un monopole d’Etat. Les « inspecteurs de la création » sont toujours là alors que les « ingénieurs des âmes » créés par Staline pour remplir les mêmes fonctions d’encadrement et de distribution de subventions ont disparu depuis un quart de siècle.

Ne voyez-vous aucun signe d’amélioration ces toutes dernières années ?

Les médias ont célébré en 2013 le trentième anniversaire des institutions culturelles crées en 1983 : trente ans d’art dirigé donc ! Ils y ont interviewé les fonctionnaires. Ceux-ci ont ajouté un zeste élégant d’autocritique. Colloques, rapports et écrits faisant un bilan critique de cette longue administration n’ont eu de visibilité que sur Internet, malgré la sollicitation qui a été faite aux grands médias d’en tenir compte où de publier dans leurs « pages débat » des points de vue plus critiques.

Ce positionnement dans le refus du débat concerne également les grands médias de droite où de gauche. De même, si la dissidence française dans le domaine de l’art a produit une critique cultivée et approfondie du système en place, c’est en dehors d’un positionnement politique. C’est un problème de liberté nécessaire à l’art.

Il y a cependant progrès puisque le débat sur l’art est aujourd’hui présent sur Internet de façon intense. Les internautes ont le choix, je citerais entre autres les sites : « Sauvons l’art », « Face à l’Art », « Les chroniques de Nicole Esterolle », « Le grain de sel » de Christine Sourgins, etc.

Le débat sur l’art est accueilli par ailleurs, à droite comme à gauche, par les différents sites d’information générale, de Médiapart à Causeur en passant par Contrepoints et tant d’autres supports représentant enfin le kaléidoscope de l’opinion française.

Aude de Kerros , propos recueillis par PLG (Contrepoint, 22 mars 2014)

Notes

1. AC, acronyme de Art contemporain employé par Christine Sourgins dans « Les Mirages de l’Art contemporain », aux Editions de la Table Ronde. Cela permet de distinguer cet art conceptuel qui se dit seul contemporain avec tout l’art d’aujourd’hui et la peinture notamment.

2. Editions Pierre Guillaume de Roux, 2013.

00:09 Publié dans art, Entretiens | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, entretien, aude de kerros, france |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 31 mars 2014

Life is Always Right

Life is Always Right:

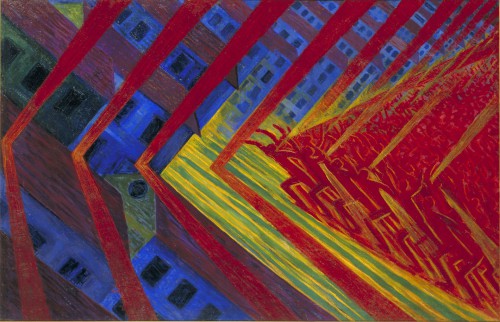

Futurism & Man in Revolt

By Mark Dyal

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

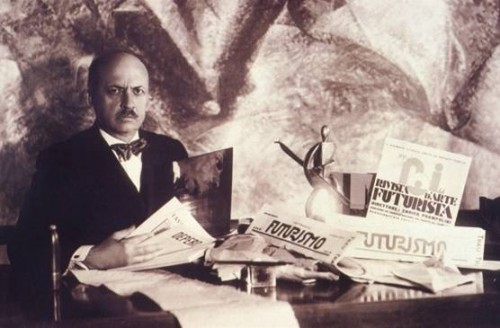

“We are not only more revolutionary than you, but we are beyond your revolution.” – F. T. Marinetti[1]

“You must know that blood has no value or splendor unless it has been freed from the prison of the arteries by iron or fire.” – F. T. Marinetti[2]

In the early days of July 1923, a heroic and blasphemous storm blew across the Carso plain and down into the Po river valley. Its daring speed and electrified energy created an atmosphere that transfixed those who scrambled for the safety of porticoes, sensing that this storm would put to a test all that had survived such storms in the past. Indeed, by the time it reached the flag-ringed buildings of Milan’s Piazza San Sepolcro the conflagration seemed to laugh at the memory of the structures that fell in its wake. And in that great and hallowed piazza, Giuseppe Prezzolini cowered away from the window, intent to finish the work that taxed his overwrought senses.

Prezzolini, the fine journalist and literary critic, was deep in rumination about perspective. How, he wondered, could those who sought to revolutionize the world champion something as amorphous and changing as perspective? How could revolt, of all things, proceed without the order and precision of truth and objectivity? How could the pathetic moans of an amateurish whore be confused with an ecstatic symphony of pleasure; or worse, how could the exalted battle cries of the world’s new masters be merely the cacophonous baying of a frightened herd of sheep? With this problem in mind, he tapped out his work, “Fascism and Futurism,” and thereby gave his readers a new perspective on the storm blowing through his proud and sanctified abode.

From Prezzolini’s perspective, the storm was violent and uncontrollable. It raged without memory with the instruments of war: grenades, mortars, and bombs seemed to explode in response to the piercing thrusts of rifle-bound bayonets, lashing wildly at the orderly and sensible piazza below. With every blow he shrank deeper into the comfort of his writing chair. Soon, however, a dreadful thought occurred to him, and he rushed to the window. Relieved and gratified, he smiled a knowing smile when he saw that the tattered symbols of reason, truth, and morality were still on guard against the vile anarchic forces besieging them.

From Prezzolini’s perspective, reason, truth, and morality were synonymous with the successful Revolution that had climaxed nine months earlier, bringing humanity one step closer to the perfection of liberty – a political and mystical right of men properly bound by duty and responsibility to the State.[3] Of course, much had happened in the meantime, and the soon-to-dissipate storm outside his window would be just as soon forgotten. As he remembered, Fascism and Futurism once had much in common. Especially in the days following the Great War, when Marinetti’s men led the revolutionary syndicalists, arditi, and critical artists into the fascist movement – back then they even called themselves “ardito-futuristi,” each with his own love of danger, violence, and reawakened instincts of the man of war.[4]

In they came, he remembered, crowding into the Industrial and Commercial Hall just outside his door. They were drunk on Sorel, proclaiming conflict a “permanent necessity” in the fight against a passive and flaccid existence. The failure of social revolution, one of them said, especially in the wake of industrialization and the creation of the urbanized mass man, was due to cowardice; the syndicalists just failed to act – and were ultimately betrayed by the Movement and Party crazed socialists.

This, according to Marinetti – the leader of this band of misfits, is one reason the Futurists claimed to be “mystics of action,” seeing the nation-State as a bastion of conservatism, repression, bureaucracy, and clericalism: even with neo-classical rulers, one might say, the State is and will always be the enemy of free men – men on the outside, in the beyond, in the nether regions of what is permissible and “good for business.”

As such, they would move against the State in the squadristi bands that almost became the ruin of The Revolution. Disdainful of the police, they were illegal, spontaneous, often haphazard, and arbitrary – hardly the stuff that goes into the establishment and defense of law and order!

So, this perpetually violent man in revolt, freed from moral and historical constraints and Statist duties and responsibilities, was to become the new “Futurist man:” a man, as Marinetti said, that is not human (for without the essential elements of the human – rationality, morality, and memory – all perfectly suited to justify slavish adherence to being-bourgeois – then one is no longer human, but something else – something monstrous, something rapacious, something joyous). Marinetti said that the bourgeois State corrodes vital energy, that it feeds upon humanized herd-animals with deadened wills yoked to universalized assumptions of natural goodness and happiness. But Prezzolini would ask him today as he did then, what good could this Futurist man bring to The Revolt? He is be too reckless, too free, and too dangerous to be of any use to men trying to build a State.

Squadrismo! Yes, he remembered, that’s what it was about: embodied radicalism, joyful violence, and the destruction of the forces of order that so perfectly connected mind, body, and State. Ruefully, he shook his head, eager to forget the ravages of such unchecked, unscripted, and useless virility. The Futurists’ virility – the cult of speed, the contempt for the masses, and the antipathy toward bureaucracy – had certainly infected the early days of the Fascist Revolution. But fighting to become-other, to move beyond duties and responsibilities while embracing the flux and chaosmos of the man in revolt, this is a far cry from fighting for the honor and glory of the State. In the former the heroic man will die alone, but in the other – in the fight that we men of the State promise and demand – the heroic man never dies. Instead he is made grander and more meaningful than he ever could have been on his own.

However, standing here in the afterglow of the creation of the Fascist State – the very symbol of victory! – Prezzolini began to laugh aloud at the memory of what would one day be called the creation of the “two fascisms.”[5]

But then, in the summer of 1921, it was the moment of truth for Prezzolini’s Revolt. Would it follow the disdainful revolutionary violence of the Futurists and arditi into an unknowable future? Or would it turn toward the bourgeois shopkeepers and landowners who sought a stable and prosperous State built on the foundations of a glorious national past? Would it be swept up in the unbridled action of the men in revolt, or would it become The Revolution? Would it maintain its core as a pack of elite and daring fighting men – those who dared, in fact, to cast off all bourgeois duties and responsibilities, to “cut all roots and understand nothing but the delight of danger and quotidian heroism?”[6] Or would it embrace its historical responsibility and create something lasting, something immortal, like a Party and State?

Indeed it would, and did – disposing of both the Futurists and ardito-squadristi alike in several purging acts of political rationality – and set itself up as the apotheosis of “hierarchy, tradition, and authority.”[7] But as the storm blew, and the rotary engines intoxicated with their own speed and sound blasted at the security of the paving stones below his window, Prezzolini felt uneasy, as if something violent, cruel, and beyond the strictures of justice was seeping through the cracks in his sanctified workspace.

At once he knew its source: Marinetti. Blasphemer! Madman! The fool who wanted to use violence to destabilize the subjective – and subjectifying – forces of the bourgeois form of life! And to what end? Well, Prezzolini knew quite well to what end. Look at this, he screamed to his soul as he grabbed the tear sheet:

And so, let the glad arsonists with charred fingers come! Here they are! Here they are! Go ahead! Set fire to the shelves of the libraries! Turn aside the course of the canals to flood the museums! . . . Seize your pickaxes, axes, and hammers, and tear down, pitilessly tear down the venerable cities! . . . You raise objections? Stop! Stop! We know them. We’ve understood! The refined and mendacious mind tells us that we are the summation and continuation of our ancestors – maybe! Suppose it so! But what difference does it make? We don’t want to listen![8]

And so Prezzolini wrote a serendipitous march, a pointed and reserved tome in defense of the tradition and past splendor that found itself under attack from these irresponsible derelicts. Look again, his tormented cogito demanded; they actually call themselves “barbarians – the recalcitrant defaulters of the Ideal!”[9]

“Fascism, if I am not mistaken,” he began to write, “wants hierarchy, tradition, and observance of authority. Fascism is content when it invokes Rome and the classical past. Fascism wants to stay within the lines of thought that have been traced by the great Italians and the great Italian institutions, including Catholicism. Futurism, instead, is quite the opposite of this. Futurism is a war against tradition; it is a struggle against museums, classicism, and scholastic honors. How can this be reconciled with Fascism, which instead is trying to restore all our moral values?”[10]

Thank God, he murmured. Thank God! Thank God we had the decency, the sensibility, and the duty to distance our glorious Party and State from these lunatics. Perspective had made Prezzolini wise, for he knew that revolution had no future. The future, as history had already shown, is with the State. So be it if Fascism had to become a counter-reformation that betrayed the revolutionary energies and critical vitalism of its founding members:[11] the State and nothing but the State, as Mussolini said – a “spiritual and moral fact!”[12] We will properly manage the social domain, he thought defiantly. We will bring continuity and regularity to all that is in flux. We will make sedentary all that flows freely.[13] We will make homogenous all that is different. We will bring law and order, rationality and peace![14] If the people are not up to the task, if they chafe at the imposition of their rulers’ and bosses’ sovereignty, if they feel no allegiance to their duties and responsibilities to the State, then . . . let them go and play with Marinetti!

Does he not understand? We are the State, we are law, and we are order, sanctified by God and international treaty! What do his Futurists wish to be? Outside! Beyond the State! Don’t they know? There is no outside – we are “the Logos, the philosopher-king, the transcendence of the Idea, the interiority of the concept, the republic of minds, the tribunal of reason, the bureaucrats of thought, man as legislator and subject, . . . the interiorized image of a world order!”[15] When you leave that, dear Marinetti – dear “recalcitrant traitor of the Idea,” where do you go?

To war, was Marinetti’s answer. Only war, he said, can create the conditions and assemblages conducive to revolution. And when you are a man alone – a man in a pack, perhaps – and find yourself without a war, well, what then? You create the necessary conditions and assemblages of your own life. You “murder the moonlight,” you “destroy time and space,” living instead in “eternal and omnipresent velocity” – the velocity of courage and aggression, of “words and thought-in-freedom,” destroying any and all stagnant prudence, “utilitarianism, opportunistic cowardice” and reactive ressentiment that you used to think justified your élan vital.[16] You create mayhem – you live without tradition, without dogma, incessantly inventing new means with which to astonish your bourgeois instincts, nurtured instead by the “new sensibility” that will decompose all that you know about beauty, greatness, religiousness, solemnity, and cultivation.[17]

Live without tradition! Prezzolini was aghast. Live without memory! Again he wondered if Marinetti and these Futurists understood the implications of their ideas. Memory, he would remind them, serves a great purpose, for it alone creates a person capable of repaying debt;[18] and debt is the basis of civilization – for indeed, how can civilization proceed without all comic, bodily, and social tributes necessarily paid?[19] And just what do the Futurists think they are forgetting? What is the purpose, if you will, of forgetting? What responsibilities, duties, and debts, must they forget? They will say that forgetting laziness, slowness, and feminine sensibility so as to affirm life as acceleration. Like Bergson they want to make time a subjective duration and bundle of intensities – a velocity carrying other velocities –

Our life should always be a velocity carrying other velocities: mental velocity + velocity of the body + velocity of the vehicle that carries the body + velocity of the element that carries the vehicle. We should dislocate thought from its mental road and put it in a material one. Velocity destroys the laws of gravity, renders the values of time and space subjective . . . Kilometers and hours are not universally the same; for the speeding man they vary in length and duration . . . Increasing lightness. You’ve triumphed over the law which forces man to crawl . . . Gasoline is divine . . . Speed in a straight line is massive, crude, unthinking. Speed with and after a curve is velocity that has become agile, acquired consciousness.[20]

Thought and existence in the production of time as flows and affects (+ and + and + and + . . . until life bursts forth from any attempts to negate and strangle its potential), extricating time itself from its rightful and natural milieu as a universal constraint of matter.[21]

But everyone knows not only that this is madness, but also that is just the beginning. Look how Marinetti dances with the sirens of our doom – with the very forces that will bring the logic of historical progress to a halt – when he advises us to “exalt the aggressive will of man, without remembrance, and to emphasize yet again the ridiculous vacuity of nostalgic memory, of shortsighted history, and of the past that is dead.”[22] And his friend Boccioni says that Futurism is here to destroy the past so as to create a “void populated by primitives and barbarians” – all with an anti-artistic sensibility connected and driven only by rhythmic movement, planes, and lines – without the sublimity of ideal forms and archetypes.[23]

But what can Boccioni possibly mean with this ridiculous suggestion? Is he trying to offer a basis of re-differentiation for the un-differentiated man? But haven’t we moved beyond such quaint notions of a return to primitivism? Just then Prezzolini was alarmed by a loud crash amongst the din of the storm. It sounded like the screech of rubber tires spinning out of control, hurling machine and life aloft like a nomadic arrow in flight – au milieu, fixed by neither the archer who shot it nor the target at which it was aimed – dancing its way to the horizon in a fiery rainbow of exploding and shrapnelizing glass and metal, the particles of each in conjunction with the other, as well as any body upon which they impacted.

To his horror the detonation was followed by a chorus of voices explaining the storm to a pair of young punks, “Life is always right,” it said, “The artificial paradises with which you hope to assassinate it are worthless.”[24] Woe to any man who goes outside in times like this, he thought; better to die now than continue this risk. And with that he cursed his ears for having been party to the impudence of these foolish men, ever more fearful that they could link his dear and tender soul to what they had overheard. He shrank evermore, and decided that a drink might calm his nerves.

And anyway, he realized as he savored his cup of hot milk, isn’t Boccioni a Futurist? Of all people he should know better. And what does a “barbarian void” offer that the State does not? Carlo Carrà gave us a sense of what the barbarian void seeks in distancing itself from the State: creation – to understand life in terms far removed from the purely representational form of rational bureaucratic thought that he called “illustrationism.” Illustrationism involves a tracing of life’s potentials, always governed by traditions, conventions, and the all-seeing Ideal.[25]

What Futurism proposes instead is an unbridled creationism, in which painters paint sound, movement, and uncover all of the affective qualities awaiting a revolt in the quantities of human instincts:

. . . Words unmoored, ideas unbound, free of the enslavement of instinctual energy and techniques of living to forms and ideas that castrate as much as they create. Outside of work we find invention. Outside of schools we find free thought. Outside of del giorno concepts, theories, estimations, and potentials — beyond the straight and narrow path that they delineate: an echo of the refrain of the walking dead! . . . the funereal normality of thinking and being in the service of forces that demand so little of us: the ease of believing and submitting to banality and commonality – we seek and demand of ourselves a life taken out of bounds.

Painting smells, he had to laugh at that one. That would be like legislating or commanding revolution. He was shocked at himself, as for one horrifying moment he found himself talking just like them! But his uncertainty brought his mind back to its work. How do these barbarian Futurists plan to create anything, especially in light of Marinetti’s war against grammar and linguistic convention, he thought. “Words-in-freedom,” Marinetti says, will undermine and disrupt the codifying principles of language – principles that shape consciousness and the functional interplay with reality. He asks us to abandon the use of “I,” which anthropomorphizes a particularly bourgeois understanding of the subject, positing instead a “return to the molecular” and an understanding of the splinters and shards of our subjectivity that hold the keys to our revolutionary potentials.[26]

He asks us to “destroy syntax and scatter one’s nouns at random, just as they are born,” to “abolish adjectives and adverbs,” which force, and presume, a pause in the flow of experience, and create a “tedious unity of tone,” which only exists in language. What’s more, he suggests that verbs only be used in their infinitive form, so as to create an elasticity of relations (in contrast to an enslavement of the moving and doing verb to the parasitic “I”) and to “give a sense of the continuity of life and the elasticity of intuition.”[27]

In this light, Prezzolini quickly realized that what the Futurists were doing was dangerous and a threat to the victory of the Fascist State. The human being, it is true, can be herded into vast conglomerates and easily convinced of its universal values and properties. But just because man can so readily live in a herd, is this its optimal potential? This is the question that Prezzolini now discovered at the heart of the Futurist manifestos. With their attacks on language as an automation machine commanding the interconnection and coordination of beings for territorializing despotic tasks that serve only the most slavish of the herd, Futurists were attempting to short circuit the ties of the social contract. They understood that the conscious organism must be compatible with the social system in which it exists.[28]

Shifts in the modalities of social life – like barbarian voids or packs – must entail a concomitant shift in consciousness and functional interplay with existence. Attention, cognitive processing, decision-making, and expression all undergo constant mutation in order to maintain their association with sense-making apparatuses of the particular collective modality.[29] Understood even in this simplified way, one sees very clearly the implications of the State presenting itself as “the rational and reasonable organization of a community,” with the “interior or moral spirit of the people” as the organizing principle of a “harmonious universal absolute spirit.” The State justly becomes the nexus of correct-thinking, pure reason, and personal mastery.[30] If those links are broken, and sense no longer can be made (or made to be made), then the duties, debts, and responsibilities yoking man to a sociality that makes a mockery of his instincts make no sense. Mayhem!

Our Father in heaven, Prezzolini stuttered as he began pacing the room. Suddenly the storm seemed to rage much louder. Our Father, he said again, if only those were marching boots I hear and not the dissonant hum of warplanes and failing power generators. His work now seemed to have the importance of a Papal Bull. This throwing the past into the sea so as to increase one’s agility in evading roadblocks – surely these roadblocks, these very barriers to chaos are the keys to our victory! – can only lead to ruin. But to destroy the very bases of order and right thinking in the present is even more egregious. Men of this type must be led – for their own good and for the good of The Revolt. Yes! They must be led, or be eliminated.

Certainly this is clear when we read in Marinetti’s “War, the Only Hygiene of the World,” of his disappointment with the disarmament of revolutionary energy when it is handed over to the leaders of The Revolt, who, as he says, are “fatally interested in preserving the status quo, calming down violence, and opposing every desire for adventure, risk, and heroism.”[31] But again, we must reproach Marinetti for failing to understand the importance of prudence, opportunism, and building a mass-based organization of great political and social potential.

And when we say that this organization with universal appeal and dedication to wisdom and order is to be immortal, what does Marinetti say? He says that the Futurist “lovers and defenders of heroic instincts” feel “only repugnance at the idea of striving for immortality, for at bottom it is no more than the dream of minds vitiated by usury.”[32]

To him and the others, he would return their repugnance with interest! He smiled at the irony, for now he was the one who had the ear of the Duce. Perhaps, he thought furiously, the entirely contingent circumstances that aligned these maniacs with The Revolt once justified their cancerous dereliction, but they have no role to play in the State. And so he returned to his oft-interrupted work:

Fascism cannot accept the destructive program of Futurism, and instead it will have to restore the very values that clash with Futurism. Political discipline and hierarchy are also literary discipline and hierarchy. Words are rendered empty when political hierarchies are made pointless. Fascism, if it truly wants to win its battle, has to consider Futurism as having already been absorbed for what it could provide as a stimulus, and has to repress it for whatever it may still possess that is revolutionary, anticlassical, and unruly.[33]

And so, while Marinetti and his merry band of Futurist revolutionaries waged a war without frontlines against the Parties, values, representations, and power of the bourgeois world – bringing a storm of uncontrollable aggression and dereliction to all of the hallowed halls that glorified the empire of the Last Man, Giuseppe Prezzolini finished his work, its last sentences littered with defenses of hierarchy and order, and “words in their proper place, obeying the rules, and respecting nature.”[34] He then mailed it to the appropriate governmental commission appointed to reform education for their approval and enlightened council.

Notes

[1] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Beyond Communism,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 260.

[2] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Let’s Murder the Moonlight,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 55.

[3] Emilio Gentile, The Struggle for Modernity: Nationalism, Futurism, and Fascism (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003), 21.

[4] Adrian Lyttleton, The Seizure of Power: Fascism in Italy, 1919–1929, Revised Edition (London: Routledge, 2004), 46–49.

[5] Lyttleton 55.

[6] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “We Abjure our Symbolist Masters,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 93–95.

[7] Giuseppe Prezzolini, “Fascism and Futurism,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 276.

[8] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 53.

[9] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Quarter Hour of Poetry of the Decima MAS,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 505

[10] Prezzolini, 276.

[11] Lyttleton, 370.

[12] Benito Mussolini, The Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism, translated by Jane Soames (New York: The Gordon Press, 1976), 21.

[13] James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 2.

[14] Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1870–1920 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1967), 154.

[15] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, On the Line, translated by John Johnston (New York: Semiotext(e), 1983), 56.

[16] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 51.

[17] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “The Variety Theater,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 159–61.

[18] Maurizio Lazzarato, The Making of the Indebted Man: An Essay on the Neoliberal Condition, translated by Joshua David Jordan (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2012), 40.

[19] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality, translated by Carol Dithe, edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 41.

[20] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “The New Religion-Morality of Speed,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 224–29.

[21] Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2012), 90–92.

[22] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Critical Writings (New Edition), translated by Doug Thompson, edited by Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2006), 252.

[23] Umberto Boccioni, “Futurist Sculpture,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 118.

[24] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Tactilism,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 266.

[25] Carlo Carrà, “Warpainting (Extracts),” in Futurist Manifestos, edited by Umbro Apollonio (Boston: MFA Publications, 2001), 202–5.

[26] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Words-in-Freedom,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 147.

[27] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 119–20.

[28] Berardi 17.

[29] Berardi 123.

[30] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Nomadology: The War Machine, translated by Brian Massumi (New York: Semiotext(e), 1986), 42–43.

[31] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “War, the Only Hygiene of the World,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 85.

[32] Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Multiplied Man and the Reign of the Machine,” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 89.

[33] Prezzolini 277–78.

[34] Prezzolini 278.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/03/life-is-always-right-futurism-and-man-in-revolt/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Pannaggi-7701-586x478.jpg

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, avant-gardes, futurisme, italie, marinetti |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 21 mars 2014

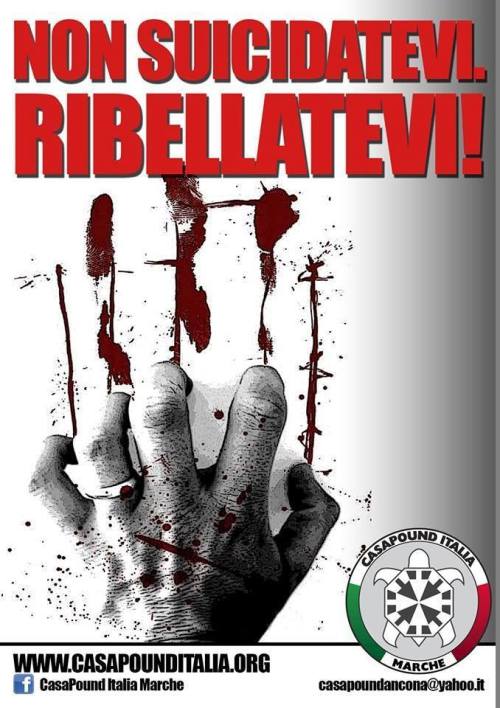

Non suicidatevi. Ribellatevi!

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, affiche, rébellion, casa pound |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 12 mars 2014

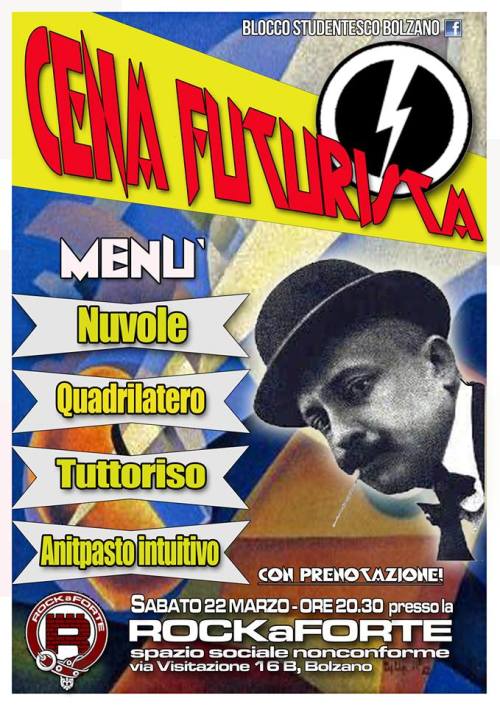

Cena futurista

00:07 Publié dans art, Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, avant-gardes, événement, italie, bolzano, futurisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

The Paintings of Julius Evola

The Paintings of Julius Evola

Ex: http://aristocratsofthesoul.wordpress.com

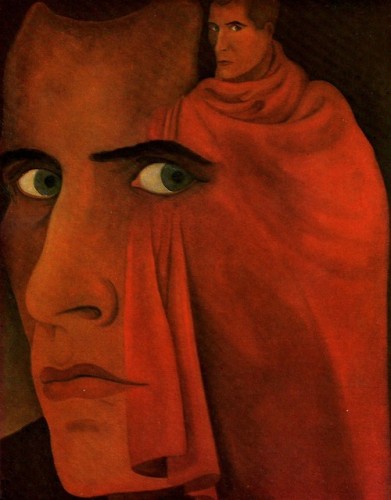

The esotericist Julius Evola came to view Dadaism as decadent later in his life, and only spent a few years as a painter. But for fans of his writing and philosophy, the paintings he did in his youth hold a special fascination, and provide insights into his later philosophy.

Evola has been called “Italy’s foremost exponent on Dadaism between 1920 and 1923″ (according to Roger Griffin’s Modernism and Fascism, pg. 39). Fifty-four of his paintings were exhibited in Rome in 1920, and an exhibition in Berlin included 60 paintings by Evola. and According to an essay on Dada on the website of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Evola launched a Rome Dada season in April 1921, which included an exhibition at the Galleria d’Arte Bragaglia that included works by Mantuan Dadaists Gino Cantarelli and Aldo Fiozzi, as well as performances at the Grotte dell’Augusteo cabaret. Evola did readings from Tristan Tzara’s Manifeste dada 1918 and said that Futurism was dead, causing an uproar.

Evola’s intellectual autobiography, The Path of Cinnabar, provides insights into Evola’s foray into the art world in the chapter “Abstract Art and Dadaism.” He was attracted to Dada for its radicalism, since it “stood for an outlook on life which expressed a tendency towards total liberation, conjoined with the upsetting of all logic, ethic and aesthetic categories, in the most paradoxical and baffling ways” (pg. 19). He quotes Tzara: “What is divine within us, is the awakening of an anti-human action” and cites a Dadaist philosophy with a premise in keeping with Evola’s thoughts on the Kali Yuga:

Let each person shout: there is a vast, destructive, negative task to fulfil. To swipe away, and blot out.In a world left in the hands of bandits who are ripping apart and destroying all centuries, an individual’s purity is affirmed by a condition of folly, of aggressive and utter folly. (pg. 19)

Evola says that such an emphasis on the absurd seems, at an external level, analogous methods used by schools of the Far East such as Zen, Ch’an, and Lao Tzu’s writings.

If some of Evola’s paintings seem ugly, it’s not without purpose and intent from the artist. In 1920′s Arte astratta, Evola outlined his theory that “passive aesthetic needs were subordinate to the expression of an impulse towards the unconditioned.” Dadasim, as Evola understood it, was not to create art as it’s usually understood, but “signalled the self-dissolution of art into a higher level of freedom” (Cinnabar, pg. 20-21).

It was during the Dadaist period of his life that Evola started reading about esotericism. He met neo-Pythagorean occultist Arturo Reghini in the early 1920s. He quit painting in the early 1920s, and stopped writing poetry in 1924–not to pursue either again for more than 40 years (according to Gwendolyn Toynton’s essay “Mercury Rising” at Primordial Traditions). Although Evola left the Dadaist movement after a few years, in an interview in 1970 he said that the movement even today “remains unsurpassed in the radicalism of its attempt to overturn not only the world of art, but all aspects of life” (Cinnabar, pg. 257).

The following paintings are compiled from numerous sites on the Internet. I believe this is the most complete and detailed collection of Evola paintings on the web (in English, at least).

Early works (1916-1918):

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

The painting below appears to have sold at Christie’s for $43,152. A different source gives the date as 1920-21:

The following painting, according to the book Alchemical Mercury: A Theory of Ambivalence by Karen Pinkus, is now in the Kunsthaus of Zurich. On one of the many geometric blocks, Evola has written “Hg” (the symbol for Mercury) in red ink. According to Pinkus, “this is a very interesting gesture, especially as the inscription seems entirely disjoined from the composition itself, as if it had been an afterthought, and a reflection of the troubled relationship between modern chemistry as abstraction and alchemical materiality.”

This oil painting is hanging on a wall of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome (according to Guido Stucco’s introduction to The Yoga of Power, pg x):

* * *

This oil-on-cardboard painting comes up in past auction searches for Evola’s work:

The following two works were published in Evola’s 1920 book Arte astratta: Posizione teorica, 10 poemi, 4 composizioni (Rome: P. Maglione & G. Strini). You can see the other two compositions in a online scan of the book at the website of The International Dada Archive at the University of Iowa Libraries. Evola’s essay “Abstract Art” is available in English translation in the book Dadas on Art.

* * *

Middle Works (early 1920s):

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

Julius Evola, “Paesaggio interire, aperture del diaframma” (“Interior landscape, the opening of the diaphragm”), 1920-21

* * *

* * *

Late paintings:

Numerous sources on the web, including academic papers and art auction houses, show paintings by Evola that he did much later in his life, several which are shown below. If any readers know where to find information about Evola’s later works in English, I would greatly appreciate being contacted in order to update this section.

This painting was listed at an art auction website, and said to be painted in 1945:

The following two paintings are cited in Julius Evola: L’Altra Faccia Della Modernita by Francesca Ricci and on the website of the Fondazione Julius Evola.

* * *

* * *

Readers interested in seeing more of Evola’s artwork can check out this video, which has additional images:

And this French TV interview, with English subtitles, is Evola on Dada:

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, tradition, julius evola, traditionalisme, avant-gardes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 07 mars 2014

Futurism in Venice

00:05 Publié dans art, Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : venise, ityalie, futurisme, art, avant-gardes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 05 mars 2014

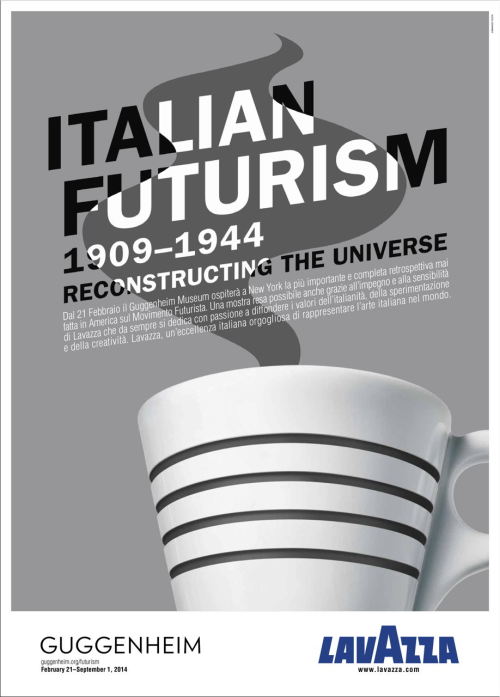

Italian Futurism

00:05 Publié dans art, Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : italie, événement, futurisme, art, avant-gardes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 12 février 2014

P'tit Père des peuples

18:23 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : caricature |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 22 janvier 2014

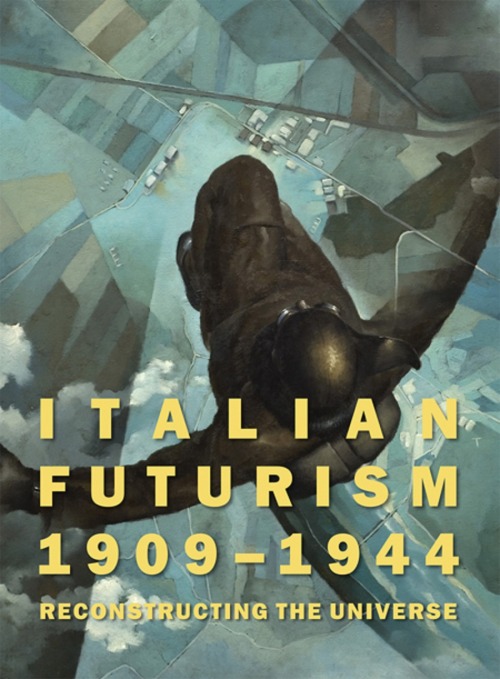

Italian Futurism 1909-1944

Edited and with introduction by Vivien Greene. Text by Walter Adamson, Silvia Barisione, Gabriella Belli, Fabio Benzi, Günter Berghaus, Emily Braun, Marta Braun, Esther da Costa Meyer, Enrico Crispolti, Massimo Duranti, Flavio Fergonzi, Matteo Fochessati, Daniela Fonti, Simonetta Fraquelli, Emilio Gentile, Romy Golan, Vivien Greene, Marina Isgro, Giovanni Lista, Adrian Lyttelton, Lisa Panzera, Maria Antonella Pelizzari, Christine Poggi, Lucia Re, Michelangelo Sabatino, Claudia Salaris, Jeffrey T. Schnapp, Susan Thompson, Patrizia Veroli.

Published to accompany the exhibition Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe opening at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2014, this catalogue considerably advances the scholarship and understanding of an influential yet little-known twentieth- century artistic movement. As part of the first comprehensive overview of Italian Futurism to be presented in the United States, this publication examines the historical sweep of Futurism from its inception with F.T. Marinetti’s manifesto in 1909 through the movement’s demise at the end of World War II. Presenting over 300 works created between 1909 and 1944, by artists, writers, designers and composers such as Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Fortunato Depero, Gerardo Dottori, Marinetti, Ivo Pannaggi, Rosa Rosà, Luigi Russolo, Tato and many others, this publication encompasses not only painting and sculpture, but also architecture, design, ceramics, fashion, film, photography, advertising, free-form poetry, publications, music, theater and performance. A wealth of scholarly essays discuss Italian Futurism’s diverse themes and incarnations.

00:05 Publié dans art, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, italie, futurisme, avant-gardes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 11 novembre 2013

Art contemporain : les élites contre le peuple

Art contemporain : les élites contre le peuple

L’art contemporain revendique volontiers l’héritage des « maudits » et des scandales du passé. Et cependant, « artistes » et laudateurs d’aujourd’hui ne réalisent pas que leurs scandales ne combattent plus les tenants de l’ordre dominant, mais ne constituent en fait qu’un outil de plus de la domination bourgeoise. Par ce qu’il prétend dénoncer, l’« art » dit « dérangeant » participe de la domination libérale, capitaliste, oligarchique et ploutocratique, à la destruction du sens collectif au profit de sa privatisation, à cette démophobie qui a remplacé dans le cœur d’une certaine gauche la haine des puissants et des possédants. Cet « art » dit « dérangeant » est en parfaite harmonie avec ces derniers.

Épargnons-nous un discours qui, trop abstrait, serait rejeté par les concernés, les défenseurs de cette pitrerie libérale-libertaire nommée « art contemporain ». Prenons donc quelques exemples, quelques « scandales » ou actions représentatives de ces dix dernières années. En 2002, l’Espagnol Santiago Sierra fait creuser 3000 trous (3000 huecos, en castillan) à des ouvriers africains pour un salaire dérisoire afin de, nous apprend-on, dénoncer l’exploitation capitaliste, revendiquant une « inspiration contestataire axée sur la critique de la mondialisation, de l’exploitation de l’homme par l’homme, de l’inégalité des rapports Nord-Sud et de la corruption capitaliste. Il n’hésite pas à faire intervenir dans ses performances des sans-papiers, des prostituées, des drogués et à les rémunérer pour leur présence », apprend-on en effet, par exemple sur le site d’Arte TV [1]. Exploiter pour dénoncer l’exploitation : à ce titre, on pourrait bien aller jusqu’à voir un artiste supérieur en Lakshmi Mittal, par exemple.

En 2009, le costaricien Guillermo Habacuc Vargas (cf. site personnel) organise, pour l’inauguration d’une expo à Milan, un banquet préparé avec la sueur des immigrants (littéralement : la nourriture contenait la sueur collectée des immigrants qui l’avaient préparée). Deux ans plus tôt, il s’était fait connaître parce qu’il aurait laissé mourir un chien, cela constituant une « œuvre » (la réalité de l’évènement – le galeriste a annoncé par la suite que le chien avait en fait été libéré – s’est effacée derrière la rumeur mondiale, qui fit l’affaire de ce médiocre). Fin 2012, le Belge Jan Fabre provoque un violent scandale – qui lui vaut d’ailleurs des coups et menaces physiques – pour un lancer de chats dans l’hôtel de ville d’Anvers. Pourquoi cette « performance » ? Pour un hommage au cliché Dali Atomicus…

Tenons-nous en à ce court inventaire pour l’instant : d’autres exemples suivront.

Merde aux petites gens : les élites contre le peuple

Qui donc dérange l’art dit « dérangeant » ? Que cherche-t-il à déranger ? Sont-ce les oppresseurs qui sont visés ? Bien sûr que non. Les dominants (le système capitaliste et ses organisateurs, le marché de l’art, les institutions validatrices et promotrices de l’art, les bourgeois cons-sommateurs de ce non-art con-tant-pour-rien), habitués aux registres de la parodie, de la provocation, de l’outrance, se satisfont du renouvellement des pitreries et des gesticulations.

Ceux que visent les provocations de l’art contemporain, dans bien des cas, sont surtout les gens ordinaires, ceux que les merdias appellent les « anonymes » parce que leur donner un nom, un droit à s’exprimer, est hors de question pour ces fameux « démocrates » – entendre le mot davantage au sens du parti politique américain capitaliste et libéral, qu’au sens antique et étymologique. Ce sont bien les « non-initiés » aux prétendus arcanes de l’« art » contemporain qui sont visés, les personnes extérieures à cet incestueux milieu, à ces coquetteries conceptuelles de bourgeois et de larbins wannabe. Pourquoi « déranger » ces gens ordinaires ? Parce qu’ils seraient dangereux ? rétrogrades ? secrètement puissants ? Parce qu’ils porteraient en eux le-germe-de-la-Bête-immonde-qui-rappelle-les-heures-les-plus-sombres-blablabla ?

« Ceux que visent les provocations de l’art contemporain, dans bien des cas, sont surtout les gens ordinaires, ceux que les merdias appellent les « anonymes » parce que leur donner un nom, un droit à s’exprimer, est hors de question pour ces fameux « démocrates »

Rapporté à l’énorme puissance financière, médiatique et symbolique du milieu – bourgeois – de l’art contemporain et de ceux qui le défendent, c’est pourtant dérisoire. C’est aussi piteux et veule que l’attitude des « éditocrates », cette bavarde racaille de naintellectuels médiatiques, à l’endroit des dominés et des « anonymes » (fermeté, mépris ou indifférence) [2]… mais toujours serviles devant le Capital et la ploutocratie libérale. Car n’est-il pas connu que les classes laborieuses sont des classes dangereuses, réactionnaires et mal éduquées ? Et que, à l’inverse, les grands patrons, les décisionnaires économiques et la jet-set politique sont dans le camp du Bien et du Progrès, celui qui se réunit en club de gens bien éduqués, au Siècle et qui toujours dira non à la Bête-immonde-et-aux-heures-les-plus-sombres ? D’ailleurs, les ploutocrates bien éduqués tels que Pinault ou Cartier, ne sont-ils pas de gentils progressistes amoureux de l’art et de la culture, comme l’atteste leur fondation ?

À la vérité, il y a que les gens ordinaires, les classes populaires, les campagnards, les banlieusards, mais encore les personnes de conviction (religieuse, politique, patriotique, culturelle…) ne méritent pas le respect – ni pour les policaillons arrivistes, ni pour les fonctionnaires validateurs de l’ââârt d’État, ni pour les pirates de la ploutocratie mondialisée… ni pour les « artistes » dits « dérangeants », communiant dans le mépris du peuple avec les maîtres du monde.

C’est pourquoi, est légitime et logique, d’un point de vue démophobique, un commando de femmes déguisées en Blanche-Neige et armées de – fausses – kalach qui s’en va donner une série de « performances » dans des villages de la Vienne… Quoi de plus logique en effet, au nom de l’ââârt démophobique, que de faire atterrir en hélicoptère (il ne serait pas inintéressant de savoir qui a financé cette pitrerie forcément coûteuse) des femmes déguisées en Blanche-Neige et armées et de les laisser défiler entre les étals d’un marché provincial ? Qu’importe si ça colle la pétoche à ces gueux [3] ; oui, qu’importe si le « sale peuple » ne voit que la kalachnikov et les déguisements de Blanche-Neige… Qu’importe s’il ne comprend pas l’ââârt de Catherine Baÿ et que pour elle « ce qui est important, c’est de créer des occasions de communiquer, de parler »[4], car le peuple n’est qu’un ramassis d’indécrottables arriérés – au fond, Patrick Le Lay avait sans doute raison de parler du « temps de cerveau humain disponible » que l’on vend à Coca-Cola, car il n’y a rien d’autre à tirer de cette chair à consommation que sont « les gens »… Heureusement pour son ââârt, Catherine Baÿ (cf. vidéo en tête de l’article), soutenue par les ronds-de-cuir validant l’art officiel d’État, aura par ailleurs la chance de faire l’intéressante au sein de l’institution beaubourgeoise… et de trouver ainsi un public d’esprits éclairés à la hauteur de son ââârt, qu’on appelle les élites, c’est-à-dire plus exactement ce que Christopher Lasch nommait « les nouvelles élites du capitalisme avancé ».

Dans un registre proche, citons un passage relatif à un certain Joseph Van Lieshout, qui rappelle que tout ce néant n’est au fond pas si « dérangeant » pour le système et qu’il ne vaut au fond guère mieux que des jeux de grands gamins inconséquents, indifférents au monde extérieur : « Lorsque Van Lieshout, à Rabastens, dans le Tarn, sillonne avec ses petites copines les rues de la bourgade à bord d’une Mercedes surmontée d’une mitrailleuse, installe un « baisodrome » sur la place du marché, entre vendeurs de coupons de tissu et de boudin noir et mime avec des gestes stéréotypés des poses de beuveries, il défraye à bon compte le landerneau. Mais en quoi cela gêne-t-il le système ? Au contraire, le spectaculaire, le burlesque, l’alimentent » [5].

Ce prétendu « art », au fond, n’a aucune vertu positive : il n’éclaire ni ne grandit l’individu ; il ne l’exhausse pas, il ne lui enseigne rien, il ne lui montre nulle part ce qu’il peut avoir de meilleur ou de grand – ni d’ailleurs de pitoyable – parce que, au fond, il ne croit en rien et n’a rien à enseigner, aucune valeur civilisante. Il refuse d’élaborer des repères symboliques, de défendre une vision, qui peuvent donner à une société et aux individus qui la composent de la dignité. Pour l’essentiel il dégrade l’individu, ajoute de l’incompréhension et de l’absurde à un monde absurde et opaque, à des existences morcelées, à une société en éclats conforme au projet libéral parcellitariste et au fameux mot de Margaret Thatcher selon lequel « il n’existe rien de tel que la « société » » (lire en anglais la citation intégrale), mais seulement des individus.

Ce prétendu « art » ne fait que célébrer le règne de l’arbitraire individuel, où le symbole d’un seul — exigeant qu’on en passe par sa tête ou l’intromission des experts théoriciens ou « critiques », ces néo-oracles chargés de déchiffrer ce qui n’a guère de sens et qui occupent dans le champ artistique une place comparable à celle des « experts » toujours néolibéraux de l’économie qui par leur amour de la complexité sont les grands confiscateurs de la démocratie, grands empêcheurs d’appréhension par la collectivité de sa destinée – vaut mieux que l’effort d’un langage commun. Tandis que l’art fut à travers l’histoire en majorité la production de formes, de signes, de symboles donnant leur cohérence à une culture, donnant à l’individu et au Je, le cadre de sa liberté parce qu’intégrée à la collectivité et au Nous, cet « art » affirme haut et fort le règne sadien de la pulsion égoïste d’êtres avant tout corporels, où les corps et la chair mêmes semblent réduits à n’être qu’un matériau indifférencié des autres, et où le souci d’autrui s’efface derrière un mépris tantôt diffus et tantôt éclatant de l’être humain.

Détruire les tabous, détruire la civilisation

« Car que recouvrent les appels répétés à transgresser, à dénoncer et détruire les tabous ? Une ambition sadienne : un retour à l’état de nature, la destruction des principes civilisants, la préférence à la pulsion égoïste plutôt qu’aux normes sociales, une conception au fond arriérée, pré-civilisationnelle de la liberté »

Car que recouvrent les appels répétés à transgresser, à dénoncer et détruire les tabous ? Une ambition sadienne : un retour à l’état de nature, la destruction des principes civilisants, la préférence à la pulsion égoïste plutôt qu’aux normes sociales, une conception au fond arriérée, pré-civilisationnelle de la liberté. Sur cette liberté-là, il y a lieu de s’interroger. Sigmund Freud traitait déjà en 1929, dans le chapitre III de Malaise dans la civilisation : « Cette tendance à l’agression, que nous pouvons déceler en nous-mêmes et dont nous supposons à bon droit l’existence chez autrui, constitue le facteur principal de perturbation dans nos rapports avec notre prochain ; c’est elle qui impose à la civilisation tant d’efforts. Par suite de cette hostilité primaire qui dresse les hommes les uns contre les autres, la société civilisée est constamment menacée de ruine. L’intérêt du travail solidaire ne suffirait pas à la maintenir : les passions instinctives sont plus fortes que les intérêts rationnels. La civilisation doit tout mettre en œuvre pour limiter l’agressivité humaine et pour en réduire les manifestations à l’aide de réactions psychiques d’ordre éthique (…). Si la civilisation impose d’aussi lourds sacrifices, non seulement à la sexualité mais encore à l’agressivité, nous comprenons mieux qu’il soit si difficile à l’homme d’y trouver son bonheur. En ce sens, l’homme primitif avait en fait la part belle puisqu’il ne connaissait aucune restriction à ses instincts. En revanche, sa certitude de jouir longtemps d’un tel bonheur était très minime. L’homme civilisé a fait l’échange d’une part de bonheur possible contre une part de sécurité ».

Merde aux tabous : Il est interdit d’interdire ! Et c’est bien ce à quoi s’attelle ce soi-disant « art contemporain », selon une logique libérale-libertaire et progressiste : chacun fait ce qu’il veut et sans se soumettre à des critères communs, car il faut aller vers un homme meilleur, débarrassé de ses pudeurs, ces archaïsmes. Dès lors, l’art peut consister en – littéralement – une série de branlettes (performance « Seedbed », de Vito Acconci, 1972), en des vomissements sur toile accompagnés d’un duo chantant (performance de Millie Brown, en 2011), en l’utilisation de : son sang (le boudin que fait avec son propre sang Michel Journiac, les orgies de sang de porc des Actionnistes viennois, la performance « Barbed Hoola » à l’alibi politique de Sigalit Landau ; citons encore Gina Pane, Marina Abramovic… ou, plus récemment, les popstars junkies Amy Winehouse et Peter Doherty) ; sa merde (le fondateur Piero Manzoni, mais aussi Jacques Lizène, Pierrick Sorin, David Nebreda…) ; les tourments de son intimité (Sophie Calle, Jonathan Meese, Louise Bourgeois et autres charlatans des « mythologies personnelles ») ; son arbitraire (ne citons que la ridiculissime Audrey Cottin) ; ou du vide, littéralement : Exposition des vides, à Beaubourg – sic – mais ne riez pas, philistins ! N’avez-vous donc pas compris qu’il est ici question d’ « interrogation de l’espace » ? Êtes-vous donc si incapables d’« [expérimenter] (…) un vide où advient la conscience de son propre corps dans un espace qui n’est pas neutre » ?

« Les provocations du XIXe siècle voulaient émanciper ; celle d’aujourd’hui veulent humilier, ringardiser, taire, tourner en dérision toute valeur, détruire les cadres et repères civilisants, ajouter un rire imbécile à l’universelle imbécillité de la Société du Spectacle et de la postmodernité. »

Pour éviter d’étirer à l’infini cet article, renvoyons enfin à quelques « artistes » dont la démarche consiste à sauter par-delà le tabou, au fondement même de la civilisation, du respect du cadavre : Teresa Margolles et le groupe SEMEFO (Mexique), le groupe Cadavre (Chine), dont les « œuvres » sont notamment une tête de fœtus humain sur un corps de mouette ou la « performance » Eating People de Zhu Yu consistant à manger un fœtus humain. Mentionnons encore le grand photographe américain Joel Peter Witkin, dont les mises en scènes macabres et hautement esthétiques ont pour matériau des morceaux de cadavres. Sur cette thématique, difficile de ne pas rappeler les cadavres plastinés de Günther von Hagens (1/3 Victor Frankenstein, 1/3 Josef Mengele, 1/3 Honoré Fragonard), succès massif partout dans le monde, fut interrompue à Paris en 2009, puis cette année à Bruxelles ; entre autres abjections dont il s’est rendu maître, signalons encore son « supermarché de la mort ». Mentionnons encore ce symptomatique article relatant l’exposition « Tous cannibales ! » à la Maison Rouge en 2011, dont l’auteur invitant à « déculpabiliser le cannibale qui sommeille en nous »… « Le tabou, c’est tabou, nous en viendrons tous à bout », pourraient entonner les « artistes » cons, tant, pour rien.

Serait donc risible et condamnable, fatalement « arriéré » et « réactionnaire » qui s’oppose à cette vision libérale-progressiste selon laquelle tout principe, tout tabou, toute limite, est un mur à abattre, non un cadre et un ensemble de repères, certes discutables, mais surtout structurants. L’art contemporain constitue donc bien souvent une attaque massive contre les principes de pudeur et de cette « décence ordinaire » chère à George Orwell. Les provocations du XIXe siècle voulaient émanciper ; celles d’aujourd’hui veulent humilier, ringardiser, taire, tourner en dérision toute valeur, détruire les cadres et repères civilisants, ajouter un rire imbécile à l’universelle imbécillité de la Société du Spectacle et de la postmodernité. Pure cochonnerie de cette ère où une expression si courante consiste à dire que « de toute façon, tout est relatif ».

Toutes ces manifestations « provocantes », tous ces artistes « dérangeants » visant à se « défaire des tabous »[6], sont radicalement semblables à tout ce mépris qui n’en finit plus de déferler dans la bouche des élites démophobes en sécession contre le peuple : « propos de PMU », « populistes ! », etc. Car c’est une éthique censitaire qu’il y a là derrière. Et toutes les poses vaines des « rebellocrates » n’y font rien : le capitalisme n’est pas menacé par ces âneries ; il est, au contraire, conforté dans sa dynamique de destruction des limites morales, repères symboliques, frontières et enracinements, tout cela qui permet à chacun d’avoir une dignité en s’inscrivant dans une histoire, des particularismes culturels, des symboles collectifs, de s’appuyer pour se construire en tant qu’individu sur des repères identitaires qui seuls permettent de s’ouvrir sur le monde – et non de se penser comme une monade.

L’art contemporain contre la démocratie

« Cet art n’est ni politique ni démocratique : il se fiche de la polis et méprise le démos ; il est foncièrement anti-culturel et anti-civilisationnel puisque les deux exigent que le Nous prime sur le Je, que le Nous soit la condition – limitée, encadrée, donc civilisée – de la liberté du Je»

Cet « art » dit « dérangeant » n’élève pas : il dégrade. Il valorise l’idée d’individus comme monades, comme îlots, comme isolats. Tout ce dont, précisément, le système marchand se repaît : plus l’être est isolé, moins il a de repères et plus il en cherche. Et ceux, inaccessibles, que lui propose le système des représentations de la Société du Spectacle, ne génèrent que de la frustration. La solitude et la honte de soi sont les conditions mêmes du consumérisme de masse. Et contre cela, malgré des dénonciations çà et là dans le monde de l’art contemporain, rien n’est énoncé, ou si peu. La dynamique générale est précisément celle de la privatisation du sens, du repli sur son nombril et sa « mythologie personnelle ».

Il n’est donc guère surprenant que, rejetant la culture, la civilisation, les critères, les frontières, l’art contemporain soit si souvent égocentrique, pleurnichard, autistique, de Sophie Calle à David Nebreda, en passant par Louise Bourgeois, Jonathan Meese. Des démarches toutes en phase avec l’individualisme de masse du temps, qu’on aurait tort de qualifier de narcissisme, puisque Narcisse était amoureux de son image, tandis que bien des artistes ont d’eux-mêmes une image dévalorisante d’éternels adolescents incapables de devenir adultes en prenant en compte pleinement l’existence d’autrui, la société, donc les symboles et les limites qui bornent l’affirmation d’une singularité. Autant de démarches qui rappellent les propos de Tocqueville selon qui la pulsion individualiste « fait oublier à chaque homme ses aïeux, mais lui cache ses descendants et le sépare de ses contemporains ; elle le ramène sans cesse vers lui seul et menace de le renfermer enfin tout entier dans la solitude de son propre cœur » [7].

L’art contemporain, dans son versant « provocant », ne menace ni ne dénonce le consumérisme, l’addiction aux nouvelles technologies, le culte du choc, du sexe et du bling-bling, la haine de la Beauté et des symboles. Même quand il prétend le faire, ce n’est que pour reproduire à l’identique — sans sublimation, donc — ce qu’il dénonce. Ce faisant, il participe de la même dynamique de « culture » globalitaire. Par son caractère abscons, voire autistique, parce que rejetant les symboles, codes et langages permettant un sens commun, il privatise le sens, rend illisible ce qu’il énonce (puisqu’il faut passer par sa tête, par tel texte abscons ou tel « médiateur » récitant le catéchisme de l’orthodoxie de l’art), si bien qu’il est impossible à cet art de nourrir l’esprit, d’aider à se percevoir, à se comprendre soi dans son rapport au monde, à autrui, aux limites, donc à la société, à la communauté, à la civilisation. Cet art n’est ni politique ni démocratique : il se fiche de la polis et méprise le démos ; il est foncièrement anti-culturel et anti-civilisationnel puisque les deux exigent que le Nous prime sur le Je, que le Nous soit la condition – limitée, encadrée, donc civilisée – de la liberté du Je.

Et cet art méprise d’autant plus la polis et le démos qu’il n’est, en fait, de nulle part. Que, tout comme McDonald’s ou H&M, il peut indistinctement s’exposer à Tokyo, à Rome, à New York ou à Johannesburg, car il est sans ancrage, sans passé, sans langage. Apatride comme les élites bourgeoises et les néoféodales oligarchies ploutocratiques, qui partout détruisent la démocratie au profit du marché et de l’État répressif.

Cet « art »-là n’a rien de politique, donc, et encore moins de révolutionnaire – sauf à comprendre le mot au sens le plus strict d’un retour aux origines, d’une grande boucle consistant à revenir à la sauvagerie pré-civilisationnelle, cette bonne vieille aspiration sadienne. La sécession qu’il propose, n’est pas celle d’avec les élites capitalistes et antidémocratiques, mais d’avec le peuple, d’avec l’histoire, d’avec la tradition, d’avec les tabous, les normes, les cadres – et pourquoi pas les lois elles-mêmes ? Loin d’être révolutionnaire au sens de rupture avec l’ordre établi, il y est en fait totalement intégré, et ses « provocations » et « dérangements » sans cesse vantés ne sont que les formes perpétuellement régénérées de la culture de masse dont parlait Christopher Lasch, nécessaires au renouvellement du capitalisme libéral-libertaire, en tant que culture de l’illimitation et d’indifférence à l’Autre.

Or, sans morale, sans limites à la liberté de chacun, il n’y a pas de civilisation possible. Tous les chefs-d’œuvre du passé s’inscrivaient dans les limites morales et politiques, les codes artistiques, qui étaient les conditions mêmes de l’existence d’une civilisation. Même lorsque le scandale existait, il restait circonscrit au cadre de l’art, c’est-à-dire à un jugement à la fois éthique et esthétique, les deux étant indissociablement reliés – il suffit de se souvenir que pour Diderot, l’art avait une vocation civique, donc une responsabilité (« Obligation faite à une personne de répondre de ses actes du fait du rôle, des charges qu’elle doit assumer et d’en supporter toutes les conséquences », CNRTL). Que des critiques jugeassent que Van Gogh n’était pas un artiste ou que les productions des Expressionnistes traduisissent une dégénérescence de l’esprit selon la théorie de Max Nordau, cela signalait précisément l’existence d’un abord d’où juger, donc des critères moraux, sociaux, esthétiques – lesquels ne sont pour autant pas figés à jamais (l’art du temps de Robert Campin n’est pas celui du temps de Jacques-Louis David, et cependant dans les deux cas des critères existent, qui ne relèvent pas de l’arbitraire d’une caste confisquant le mot « art »).

Si l’on examine de près l’idéologie qu’est « l’art contemporain », il en ressort que ce fatras d’imbécillités libérales et progressistes, n’est au fond qu’un vaste mouvement contre la culture et, partant, contre la civilisation. Proclamant le règne de la pulsion et de l’arbitraire individuels, il rejette de fait le sens commun et la possibilité de faire communauté. À ce titre, l’art contemporain n’est que l’alibi « culturel » et le bras armé du capitalisme néolibéral et des valeurs libérales-libertaires où communient les élites de droite et celles qui se pensent encore de gauche cependant qu’elles ont du peuple le plus profond mépris.

Notes :

[1] Sur le site du centre d’art andalou Fundación NMAC, on peut lire cet explicatif : « Ses œuvres reflètent son inconformité face au système social dans lequel nous vivons et mettent en évidence les différences sociales et raciales. Le concept principal sur lequel se base sa trajectoire artistique est relié avec le travail, surtout celui des immigrants et des marginaux de la société, avec l’absence d’opportunités et la soumission à l’activité du travail ayant pour fin le salaire et l’entretien du système capitaliste. Selon ces prémices, dans quelques-uns de ses travaux, l’artiste a engagé contractuellement des travailleurs pour réaliser des actions inutiles durant une journée de travail ». (« Sus obras reflejan su inconformidad ante el sistema social en el que vivimos y ponen en evidencia las diferencias sociales y raciales. El concepto principal en el que se basa su trayectoria artística está relacionado con el trabajo, sobre todo con el de los inmigrantes y los marginados sociales, con la falta de oportunidades y la sumisión a la actividad laboral con el fin de recibir un salario y permitir el funcionamiento del sistema capitalista. Siguiendo esta premisa, en algunos de sus trabajos, el artista ha contratado a trabajadores para realizar acciones inútiles durante una jornada laboral »).

[2] Qu’on se souvienne de la leçon de civisme que donne du haut de son surplomb bourgeois ce nabot de Pujudas à Monsieur Xavier Mathieu, délégué syndical CGT de Continental ; qu’on se souvienne l’indifférence et le mépris de l’éditocratie à l’encontre de Mademoiselle Nafissatou Diallo, lorsque le bien aimé ploutocrate-acronyme DSK fut accusé de viol ; et plus généralement, idem pour les banlieusards, les immigrés, le monde ouvrier, la paysannerie, les précaires, etc.

[3] Le Parisien rapporte ces propos d’une femme relayés par le journal local Centre Presse : « J’ai cru qu’ils allaient faire un hold-up ! ».

[4] Ne faisons pas preuve de philistinisme facile : la vraie intention de Catherine Baÿ, c’est de générer des rumeurs, afin que les gens se parlent. Cette conception d’un art consistant en somme à faire quelque chose d’absurde pour faire se parler les gens, est aussi celle du Belge Francis Alÿs, lorsqu’il pousse un grand cube de glace dans les rues de Mexico (Paradox of Praxis (Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing), 1997) : « La dispersion laisse voir un paradoxe, comme le titre le suggère. Si l’objet disparaît (le bloc de glace), son effacement produit en retour un déplacement vers une autre sorte de mobilité où c’est le geste qui survit par le récit de ceux et celles qui raconteront leur version ou plutôt leur portion de l’histoire de cette étrange glace. Raconter implique de disséminer dans l’espace et dans le temps » (Marie Fraser, à lire ici)…

[5] Alain Georges Leduc, Art morbide / Morbid Art, de la présence de signes et de formes fascistes, racistes, sexistes et eugénistes dans l’art contemporain, éd. Delga, 2007, p. 45

[6] Citons un seul récent exemple, symptomatique, à savoir le texte de présentation du festival parisien Zone d’occupation artistique (ZOA), organisé par Sabrina Weldman et qui s’est tenu en octobre 2012 à La Loge (Paris) : « Rebelle, hors-cadre, ZOA, Zone d’occupation Artistique, est une nouvelle manifestation qui souhaite mettre en lumière la jeune génération de chorégraphes et de performeurs. En un refus de se plier aux convenances et aux tabous, ce festival entend donner une visibilité à des artistes émergents : inscrits dans notre temps, ils lui font écho par des propositions brassant l’identité, la relation à l’autre, le collectif, la norme, le politique, l’érotisme, la fantasmagorie, l’inconscient,… ».

[7] De la démocratie en Amérique (Garnier-Flammarion, 1981, vol. 2, p. 127).

- Source : Ragemag

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : art, art contemporain, mystification |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 17 octobre 2013

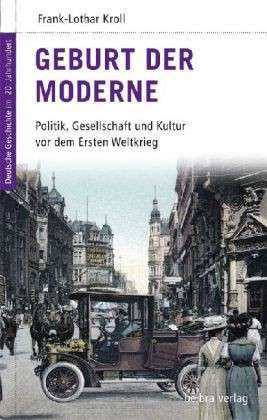

Die Geburt der Moderne

Die Geburt der Moderne

von Benjamin Jahn Zschocke

Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de

Der Nationalsozialismus ist der absolute Fixpunkt der deutschen Geschichte – wirklich alles ballt sich zu ihm hin. Alle zeitlich daran angrenzenden Epochen verschwinden in seinem Schatten.

Der Nationalsozialismus ist der absolute Fixpunkt der deutschen Geschichte – wirklich alles ballt sich zu ihm hin. Alle zeitlich daran angrenzenden Epochen verschwinden in seinem Schatten.