jeudi, 02 juin 2022

"Lobbyland": un ancien député allemand explique comment l'Allemagne est prise en otage par les lobbies

"Lobbyland": un ancien député allemand explique comment l'Allemagne est prise en otage par les lobbies

Eugen Zentner

Source: https://geopol.pt/2022/06/01/lobbyland-ex-deputado-alemao-explica-como-a-alemanha-esta-refem-dos-lobis/ & https://www.nachdenkseiten.de/?p=84388

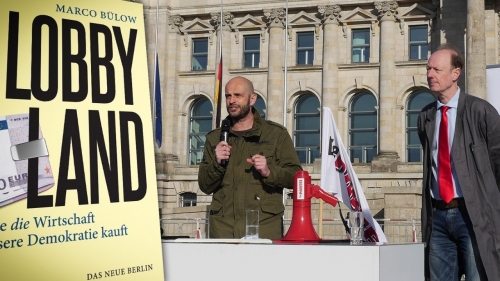

Le pouvoir des associations de lobbyistes est énorme. Dans le système politique allemand, presque rien ne fonctionne sans eux. Leur influence atteint le point où de nombreux textes législatifs sont écrits mot à mot par eux. L'ancien politicien du SPD Marco Bülow parle dans ce contexte de "Lobbyland", c'est-à-dire d'un État qui subordonne tout au principe des grands et des puissants et des profits qu'ils engrangent. Dans son livre du même nom, il s'appuie sur son expérience de député pour décrire les mécanismes et les règles de fonctionnement de la politique en Allemagne.

Jusqu'à ce que notre auteur arrive à son vrai sujet, tire ses conclusions, il s'était frayé un long chemin à travers son ancien parti social-démocrate. Bülow avait en effet rejoint la SPD en 1992, s'était d'abord impliqué dans les Jusos [la branche jeunesse du parti] pendant plusieurs années et avait acquis progressivement une réelle notoriété politique dans sa ville natale de Dortmund. Il a rapidement gagné la sympathie des électeurs. En 2002, il entre enfin au Bundestag en tant que candidat direct. Entre 2005 et 2009, il a été porte-parole de son groupe parlementaire pour l'environnement, la conservation de la nature et la sûreté des réacteurs. En 2018, il y a eu une rupture. Bülow a quitté la SPD après 26 ans de militantisme, en réponse à des conflits survenus de longue date avec la direction son parti quant au contenu idéologico-politique et au personnel. Jusqu'en novembre 2020, il a continué à siéger au Parlement en tant qu'homme politique sans parti, qui n'était inféodé à aucun groupe parlementaire, mais il a ensuite rejoint DIE PARTEI, dont il a été député au Parlement jusqu'à la fin de la législature.

L'auteur esquisse la rupture entre lui et la SPD sur la base de certaines positions qui furent particulièrement formatrices au cours de sa carrière. Comme s'il s'agissait d'une sorte de chemin de Damas, il décrit sa déception croissante face au style de gouvernement du chancelier de l'époque, Gerhard Schröder, qui lui a montré ce qu'il en était réellement derrière la façade politique: "On peut nommer des gens selon ses propres idées, qui sont à son goût, qui dictent tout ce qui est ensuite approuvé par une majorité au Bundestag. Et si c'est serré, alors vous faites pression sur les dissidents ou menacez de ne plus les impliquer. À la fin, vous avez votre décision sans le moindre changement et vous êtes étonnés de voir comment vous avez simplement suspendu la représentation du peuple".

À Berlin, il y aurait 6000 lobbyistes en activité, soit presque dix fois plus que de parlementaires. La majorité absolue sont des lobbyistes dits à but lucratif pour les industries pharmaceutiques, de l'armement ou de la finance.

On comprend que l'indignation de Bülow fut grande, d'autant plus lorsqu'un collègue expérimenté du parti lui a dit carrément que le jeu se jouait de cette façon et non pas d'une autre: "Vous avez deux options. Si vous acceptez les règles du jeu, vous aurez peut-être la possibilité de jouer plus haut dans la hiérarchie du parti à un moment donné et peut-être de vous faire accepter pour un ou deux postes. Si vous ne les acceptez pas, alors vous devrez quitter le terrain rapidement". Ces passages sont parmi les plus forts du livre. Ils donnent un aperçu des coulisses, montrent comment la politique se fait réellement au parlement et au sein des partis. Bülow ouvre le débat en dehors des sentiers battus, de l'omerta, pour ainsi dire, mais ne va malheureusement pas en profondeur.

L'exposition des principales structures, des paramètres du système et des formes typiques de comportement reste malgré tout rudimentaire dans son livre. Les principaux projecteurs qu'il allume ne sont pas très éclairants. Au lieu de cela, l'auteur allume une simple torche ici et là, et surtout s'arrête de nous éclairer au moment où les choses commencent vraiment à devenir intéressantes. Cependant, certaines déclarations sélectives confirment les soupçons de nombreux observateurs critiques et semblent encore plus authentiques venant de la bouche d'un ancien député. Il s'agit, par exemple, de son expérience selon laquelle "aucun des projets de loi parlementaires n'a été adopté sans la consultation et l'approbation du gouvernement". La même explosivité est contenue dans sa description de la pratique et de la manière dont les amendements législatifs sont effectués. Selon M. Bülow, les politiciens experts ne peuvent influencer certaines nuances qu'au prix de nombreux efforts. La plupart des changements ont toutefois résulté de la pression exercée par les lobbyistes.

On peut également apprendre de l'ancien parlementaire que la participation d'un parti au gouvernement rend son groupe parlementaire plus intéressant pour les associations de lobbying. Cela explique, entre autres, pourquoi certains politiciens ont changé d'avis si rapidement - comme, par exemple, le leader de la FDP Christian Lindner, qui s'était prononcé contre la vaccination obligatoire avant les dernières élections fédérales, mais qui a adopté une position exactement inverse lorsque son parti devint partie prenante de la coalition [actuelle] dite des feux tricolores (SPD-Verts-FDP). Qu'en est-il des groupes parlementaires eux-mêmes? La situation est-elle plus démocratique à ce niveau-là qu'au niveau des non-partis? Bülow dément catégoriquement et fait savoir que de nombreux postes sont formellement élus, mais qu'en réalité ils sont pourvus. Il n'y a pas de culture du débat ouvert. Les députés sont inconditionnellement soumis à la pression du groupe parlementaire.

Lorsque l'auteur aborde enfin son véritable sujet, on voit rapidement quels conflits internes et externes avec son parti l'ont conduit à le quitter: "S'il y a un fort lobby économique, écrit-il, la SPD s'y ralliera. Tant dans la question des voitures que dans celles de l'énergie, de l'agriculture, de l'industrie pharmaceutique. Il se liera même avec les militaires, même si cela est contraire aux principes de la social-démocratie." Comme les autres partis, la SPD s'est éloignée de sa propre base et de sa classe, a noté Bülow, surtout pendant la période de la Grande Coalition (CDU/CSU-SPD). Le budget, a-t-il dit, était un "budget déterminé par les lobbies" dans lequel les offres faites aux groupes d'intérêt respectifs étaient dissimulées de manière déguisée, souvent sous la forme de subventions dont personne ne pouvait suivre la trace.

À Berlin, il y aurait 6000 lobbyistes, soit presque dix fois plus que de parlementaires. La majorité absolue de ceux-ci sont des lobbyistes dits à but lucratif pour les industries pharmaceutiques, de l'armement ou de la finance. Contrairement aux "lobbyistes d'intérêt public", ils disposent de plus de moyens, mais ils sont également mieux formés et ont de meilleurs contacts en politique. Cela révèle la misère de tout le système. La relation étroite entre les politiciens et les lobbyistes produit ce que Bülow appelle "l'effet de porte tournante": "Il y a de plus en plus de politiciens qui utilisent leur mandat comme tremplin pour se lancer ensuite dans les affaires en tant que lobbyistes". Plus importants que les qualifications, dit-il, sont les numéros de téléphone. "Et, bien sûr, en tant que lobbyiste, vous avez un meilleur accès à vos anciens collègues. C'est une situation gagnant-gagnant".

Alors, que faire? L'ancien député estime qu'un registre des lobbyistes n'a pas beaucoup de sens, du moins s'il n'est pas contrôlé de manière indépendante et si les violations des règles n'entraînent pas de sanctions sévères. Au lieu de cela, il préconise des instruments qui rendent transparents ce dont les politiciens et les lobbyistes parlent vraiment, les accords qu'ils concluent réellement. Selon lui, les structures en place doivent être complètement révisées. Il ne sert à rien de remplacer les personnes ou le parti. À la fin de son livre, Bülow illustre ce à quoi pourraient ressembler des changements significatifs à l'aide de quelques points clés. L'accent est mis sur ce qu'il appelle le "triangle de l'avenir": "La base de ce triangle, soit le côté inférieur, est la véritable démocratie avec toutes ses obligations et ses droits. Les deux autres côtés sont constitués des besoins sociaux et des nécessités de base de la vie. Sous le terme "social", je voudrais également comprendre la justice générale et la cohésion. Par moyens de subsistance, j'entends l'environnement, le climat, la nature dans son ensemble".

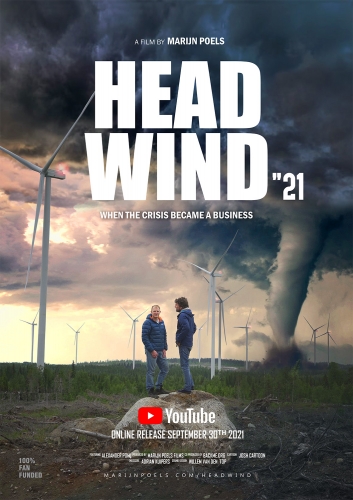

Les propositions de Bülow sont idéologiquement colorées et contiennent à l'évidence des éléments de la politique verte-gauchiste. A priori, il n'y a rien de répréhensible à cela, mais en de nombreux endroits apparaît ce qui a discrédité ses représentants au cours de ces dernières années: l'horizon étroit de la critique qu'ils formulent. Par exemple, Marco Bülow se plaint de l'influence limitée du lobby des énergies renouvelables, qu'il considère comme agissant dans l'intérêt public. Ce faisant, il ne se rend pas compte que ce secteur est également devenu une entreprise à but lucratif dans laquelle ce sont principalement les grandes entreprises qui gagnent de l'argent. Il s'agit moins d'une question d'environnement que d'argent, comme l'a clairement montré le documentaire d'investigation "Headwind '21" du cinéaste néerlandais Marjin Poels. Il montre le côté sombre des soi-disant parcs éoliens, pour lesquels non seulement des surfaces entières de terrain ont été défrichées, mais où des matières premières sont également nécessaires, dont l'extraction cause de réels dommages à l'environnement.

La vision critique est également brouillée lorsque Bülow met en avant les réactions positives aux mauvaises politiques. Si les mouvements de protestation sont loués, ce sont uniquement les mouvements verts comme les "Vendredis pour l'avenir". Le fait que des centaines de milliers de personnes soient descendues dans la rue depuis les mesures Covid pour manifester contre des politiques de plus en plus autoritaires n'est même pas mentionné - tout comme l'émergence du parti die Basis. Au lieu de cela, l'auteur cite DIE PARTEI comme preuve de la façon dont les nouveaux partis émergent du mécontentement envers le système. Les expériences autour du Covid sont au moins partiellement incluses dans le livre. Bülow l'a écrit pendant cette période et a, entre autres, traité de plusieurs scandales de mascarade impliquant des politiciens de la CDU. Ici aussi, il est évident que sa critique omet des aspects importants. Bülow ne mentionne pas d'un mot les nombreuses manipulations, les contradictions dans le récit officiel sur le Covid et les incitations à la corruption des institutions de santé, dont le camp politique gauche-vert est également en partie responsable.

L'auteur couronne le tout lorsqu'il cite Correctiv et Tilo Jung de Jung & Naiv comme exemples de journalisme indépendant et critique dans sa conclusion. Pendant la crise du Covid, cependant, les deux ont montré leur vrai visage. Correctiv, financé par les fonds de fondations et de grandes entreprises numériques, a dénigré tous ceux qui s'écartaient de la ligne de conduite du gouvernement avec ses prétendues vérifications des faits. En revanche, leur mauvaise conduite et leurs confusions n'ont pas été abordées. Et Tilo Jung a qualifié tous les détracteurs des mesures gouvernementales dans le cadre de la pandémie d'"extrémistes de droite". C'est du journalisme partisan particulièrement flagrant et cela n'a rien à voir avec un reportage objectif et indépendant. À cet égard, ils font également partie, en un sens, d'un lobby dont les pratiques devraient être critiquées tout autant que l'influence compliquée d'autres groupes d'intérêt.

17:14 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, marco bülow, allemagne, politique, lobbying, lobbies, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 31 mai 2022

Ukraine, la défaite du modèle allemand: du leader au "paria" du Vieux Continent

Ukraine, la défaite du modèle allemand: du leader à "paria" du Vieux Continent

par Roberto Iannuzzi

Source : Il Fatto quotidiano & https://www.ariannaeditrice.it/articoli/ucraina-la-sconfitta-del-modello-germania-da-leader-a-paria-del-vecchio-continente

La guerre en cours en Ukraine n'est pas seulement un conflit par procuration entre la Russie et l'OTAN, mais un affrontement qui redéfinit l'équilibre des forces entre les deux côtés de l'Atlantique et l'équilibre même des forces au sein du continent européen. Une Europe qui ne peut pas profiter des ressources énergétiques bon marché de la Russie ni commercer avec Moscou (et qui sait, peut-être même pas avec la Chine demain) est fatalement plus dépendante du gaz liquéfié et du marché américain. L'augmentation de la facture énergétique (une tendance déjà amorcée avant le conflit) entraînera une hausse spectaculaire des coûts de production, ce qui se traduira par une baisse de la compétitivité des entreprises européennes et, en fin de compte, par un appauvrissement du vieux continent.

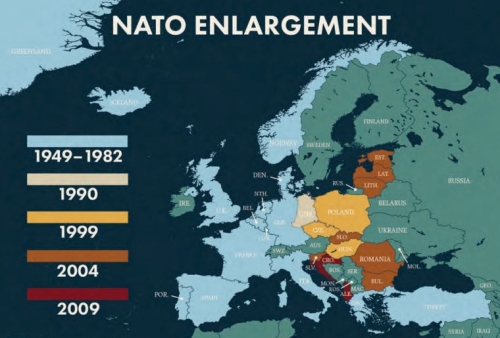

Le cas allemand est vraiment emblématique dans ce contexte. Berlin s'était consacré à la construction d'un modèle économique performant sans prêter attention aux fondements géopolitiques contradictoires sur lesquels il reposait. L'Allemagne a alimenté son industrie en hydrocarbures russes et a utilisé la main-d'œuvre bon marché des pays d'Europe de l'Est, accueillis dans l'UE depuis 2004. Grâce à l'euro, relativement plus faible que le mark, elle a pu facilement exporter ses produits vers le marché unique européen et dans le monde entier, où elle compte les États-Unis et la Chine parmi ses principaux clients. Elle a ainsi accumulé des excédents commerciaux compris entre 5,6 et 7,6 % du PIB au cours des dix dernières années. Bien qu'elle ait fini par dépendre énergiquement et économiquement de la Russie et de la Chine (deux adversaires stratégiques des États-Unis), Berlin est cependant restée militairement subordonnée à Washington, en restant au sein de l'OTAN et en soutenant son élargissement à l'Est, sans développer cette autonomie stratégique européenne dont la force motrice aurait dû être le soi-disant "axe franco-allemand".

Au sein de l'UE, Berlin s'est imposé comme un acteur économiquement hégémonique sans élaborer une vision politique qui renforcerait la cohésion des Etats membres, ni imaginer de solution pour aplanir les inégalités au sein de l'Union. Comme l'a écrit le journaliste allemand Wolfgang Münchau dans le Financial Times en 2020 - sous la direction d'Angela Merkel, l'Allemagne n'a toujours fait que le strict minimum pour assurer la survie de la zone euro, la laissant se traîner d'une crise à l'autre. En Ukraine, Berlin a essentiellement suivi les politiques anti-russes de Washington, croyant naïvement que cela profiterait à la "profondeur stratégique" allemande. Merkel a ainsi soutenu le soulèvement de Maidan à Kiev en 2014, et appuyé les sanctions imposées à Moscou après l'occupation russe de la Crimée. Mais cela ne suffit pas aux États-Unis, longtemps agacés par le modèle mercantiliste allemand et l'Ostpolitik de Berlin.

Washington avait compris depuis longtemps que Moscou, Pékin et le continent asiatique étaient désormais en mesure d'offrir à l'Allemagne et à l'Europe des possibilités de commerce et d'investissement plus avantageuses que celles des États-Unis. N'ayant plus la force économique de lier le vieux continent à eux comme ils l'avaient fait dans l'après-guerre, les États-Unis n'avaient plus que l'outil coercitif suivant : 1) attirer la Russie dans un conflit en Ukraine, en l'accusant d'être l'agresseur ; 2) construire un nouveau rideau de fer en Europe, en le renforçant par un système de sanctions qui maintiendrait ses alliés dans l'orbite économique américaine ; 3) isoler Moscou, en créant les conditions d'une rupture économique avec la Chine. Transformer l'Ukraine en un pion à jeter en pâture à la Russie a servi à effacer l'alignement naissant entre Berlin, Moscou et Pékin.

L'objectif russe était initialement opposé à l'objectif américain: couper le cordon ombilical qui lie le vieux continent à l'Amérique et créer, avec la Chine et l'Europe dirigée par l'Allemagne, un ordre multipolaire fondé sur l'intégration économique de l'Eurasie. En intervenant en Ukraine, Moscou a manifestement estimé que Berlin et l'Europe n'étaient pas récupérables, et s'est résigné à s'appuyer sur l'axe avec Pékin, se pliant en fait au projet américain d'une nouvelle confrontation des blocs. Dans ce cadre, l'Allemagne, qui était le chef de file de la composante européenne de l'"île-monde" eurasienne, se voit reléguée au rang de "paria" dans un vieux continent qui est à nouveau dirigé par les Américains. Bien qu'il se soit conformé au régime de sanctions voulu par Washington (également destiné à saper les fondements de la compétitivité allemande), le successeur de Mme Merkel, Olaf Scholz, est montré du doigt par les extrémistes européens pro-Kiev, et par le gouvernement ukrainien lui-même, comme un "pacifiste" pro-Poutine parce qu'il rechigne à adopter des politiques encore plus autodestructrices.

Pendant ce temps, le centre de gravité européen de l'OTAN s'éloigne de l'axe franco-allemand au profit d'un arc de pays - de la Grande-Bretagne aux nouveaux candidats à l'OTAN, la Finlande et la Suède, en passant par les républiques baltes et la Pologne - qui ont pris la tête de la croisade anti-russe. Avec Londres qui, ironiquement, pousse l'Ukraine à adhérer à l'UE après le Brexit !

* Auteur du livre Se Washington perde il controllo. Crisi dell'unipolarismo americano in Medio Oriente e nel mondo (2017).

Twitter : @riannuzziGPC

https://robertoiannuzzi.substack.com/

18:19 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, europe, allemagne, affaires européennes, géopolitique, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 30 mai 2022

Le Mexique dans la Grande Guerre

Le Mexique dans la Grande Guerre

Par Gastón Pardo

Le rôle discret du Mexique pendant la première guerre mondiale doit s'aborder en évoquant une confluence d'événements historiques dont on ne nous parle pas à l'école, qui font partie du mythe selon lequel le Mexique n'a pas participé à la Première Guerre mondiale parce que nous étions dans un processus révolutionnaire encouragé par les États-Unis et la Standard Oil. À l'inverse, certains pensent que, si la Première Guerre mondiale s'était déroulée aussi au Mexique, l'Allemagne et les États-Unis se seraient combattus de toutes leurs forces dans le pays. Ainsi, les Mexicains auraient été tellement occupés à s'entretuer qu'ils n'auraient pas su que les puissances se servaient d'eux.

L'historien allemand Friedrich Katz, dans son livre "La guerre secrète au Mexique", tente de ne pas aller trop loin dans ses révélations sur les activités secrètes des Allemands au Mexique, activités parallèles à celles des Britanniques et des Américains dans la lutte pour le pétrole. Il lui semblait plus important de servir les groupes dominants au Mexique que de dire la vérité.

En 1909, l'épisode dont personne ne nous parle a eu lieu lors de l'entrevue à El Paso (Texas) et à Ciudad Juarez entre Porfirio Diaz et le président américain William Taft, au cours de laquelle ont commencé les préparatifs visant à renverser le président mexicain Porfirio Diaz qui avait ouvert la côte Pacifique aux Japonais, qui avaient armé Salina Cruz, dans l'État de Oaxaca.

Lorsque Taft est venu au Mexique, il a demandé à Porfirio Díaz de ne pas construire le projet du canal sec de Tehuantepec parce qu'il ferait concurrence au canal de Panama et de permettre aux États-Unis d'avoir une base militaire en Basse-Californie du Sud pour infiltrer l'Amérique latine à partir de là.

Il a également demandé à Porfirio Diaz (photo) de cesser d'acheter des armes pour l'armée mexicaine auprès du nouvel empire allemand émergeant et de les acheter plutôt aux États-Unis, ce à quoi Porfirio Diaz a répondu non. Plus important encore, Taft est venu demander que des concessions spéciales soient accordées aux hommes d'affaires américains pour l'extraction du pétrole mexicain, ce à quoi Porfirio Diaz a également répondu non.

Mais le général Alvaro Obregón, lorsqu'il était président du Mexique en 1923, a dit oui et a signé les traités Bucareli avec les États-Unis, qui, sur la base du droit international, accordaient aux États-Unis une situation privilégiée dans l'exploitation du pétrole. Ces traités demeurent en vigueur, après 100 ans de politiques désastreuses qui ont soumis les Indiens Huastec à l'utilisation abusive de leurs terres au profit de l'exploitation pétrolière.

Le pétrole mexicain était extrait à cette époque par l'Anglais Weetman Dickinson Pearson, ce qui laisse supposer qu'en 1909, il y avait un conflit entre les puissances anglo-saxonnes au sujet du pétrole mexicain, notamment parce que l'Empire allemand, né en 1871, était déjà la première puissance en Europe en 1910, lorsque la révolution mexicaine a commencé, et constituait déjà une menace pour l'Empire britannique. L'exploitation du pétrole au Mexique remonte à 1901 par le truchement d'une société américaine, suivie par El Aguila, une société anglaise.

Il ne fait donc aucun doute que la révolution mexicaine a commencé avec des armes et un soutien logistique américains pour Francisco I. Madero et a réussi à renverser Porfirio Diaz. Bien sûr, les gringos ne donnèrent rien. Comme nous le savons, le pays de Madero s'effondrait sous sa présidence et les gringos ont pris sur eux de l'éliminer. Un autre épisode peu connu est qu'en 1912, Winston Churchill, alors Lord of the Admiralty, le chef de la marine britannique, a demandé que le budget de guerre soit doublé pour faire face à la menace allemande, car les Britanniques et les Allemands se disputaient des territoires qui pourraient devenir des colonies dans le monde entier et en même temps ils se disputaient le pétrole.

L'Allemagne a été le premier pays européen à changer toute sa flotte fonctionnant au charbon pour une flotte fonctionnant au pétrole, et Churchill a donc demandé à l'Angleterre de faire de même. Le détail qui retient l'attention est qu'à cette époque, on n'avait pas encore découvert le pétrole de la mer du Nord ; par conséquent, l'Angleterre n'avait pas de pétrole et l'Allemagne non plus, et ils ont dû mettre les flottes les plus puissantes du monde en mouvement avec du pétrole venu d'ailleurs. Cela signifiait que les deux nations devaient se battre pour le pétrole du Moyen-Orient, qui était à l'époque le pétrole de la Mésopotamie, partie de l'Empire turc, depuis lors allié de l'Empire allemand.

Bien que les hommes d'affaires qui ont extrait le pétrole étaient anglais et que l'autre grande source de pétrole à cette époque n'était autre que le Mexique, l'Angleterre avait donc déjà l'homme d'affaires Weetman qui possédait la propriété du pétrole du Mexique.

Les Allemands voulaient venir exploiter le pétrole mexicain, les gringos voulaient aussi venir exploiter le pétrole mexicain, le président du Mexique, Porfirio Díaz, avait 80 ans et ils ont donc commencé à bouger les pièces nécessaires pour le renverser et mettre un président à leur convenance à sa place. Les gringos ont d'abord essayé avec Francisco I. Madero et plus tard avec Venustiano Carranza, tandis que les Allemands ont soutenu Victoriano Huerta (photo). Selon le récit historique conventionnel, la Révolution au Mexique a commencé le 20 novembre 1910, mais ce qui s'est passé n'est qu'un soulèvement armé qui a abouti à la démission de Porfirio Diaz et à l'arrivée au pouvoir de Francisco I. Madero en 1911. Telle était la situation à la veille de l'année 1912.

Madero "gouvernait" soi-disant le Mexique et le pays était devenu une véritable poudrière. C'est alors que les gringos eux-mêmes ont planifié de renverser Madero et ont tenté de le renverser en faveur du général Felix Diaz, neveu du président déchu Porfirio Diaz.

Puis apparaît Victoriano Huerta, qui, avec le soutien de l'ambassadeur américain Henry Lane Wilson et après avoir négocié avec l'ambassadeur allemand Heinrich von Eckardt, renverse également Madero. Pour de nombreux spécialistes, la véritable révolution mexicaine commence en 1913 avec le renversement de Madero et cette étape révolutionnaire est liée à la Grande Guerre.

Les troupes constitutionnalistes s'approchaient du port de Veracruz en mars 1914 et étaient sur le point d'en prendre le port; ensuite, en avril de la même année, lorsque 100 navires yankees ont bloqué le port de Veracruz, un fait inexplicable car il n'y avait pas de guerre déclarée contre eux, il s'avère qu'il y a eu un incident dans le port de Tampico, où quelques marins américains y descendent avec leur drapeau et sont arrêtés par des militaires mexicains.

Un conflit international a alors éclaté et les États-Unis ont demandé que le drapeau gringo soit salué et honoré sur le sol mexicain. Le gouvernement mexicain refuse et les Américains envahissent alors la côte du Golfe. En réalité, ils étaient venus pour protéger les puits et les installations pétrolières et surveiller les douanes de Veracruz et de Tampico ; en outre, les gringos ont découvert que le navire Ipiranga, le nom du navire allemand avec lequel Porfirio Diaz a quitté le pays, était sur le point d'accoster dans le port de Veracruz pour livrer des armes allemandes au gouvernement de Victoriano Huerta, qui a promis de mettre le pétrole mexicain à la disposition des Allemands; les gringos ont alors empêché ces armes d'être livrées aux troupes du gouvernement de Huerta, facilitant ainsi sa défaite.

Lorsque Huerta s'exile, il arrive à La Corogne, en Espagne, où des agents du Kaiser allemand l'attendent pour lui offrir des armes et un soutien pour retourner au Mexique et prendre le pouvoir, ainsi que des facilités pour son retour via New York. C'est là, en effet, qu'il entre en contact avec un espion allemand et commence son voyage vers la frontière mexicaine, où des sous-marins allemands l'attendent avec des armes pour le soutenir pour qu'ils reviennent au pouvoir.

Mais Huerta n'a pas pu franchir la frontière car il a été fait prisonnier par les Texas Rangers qui l'ont mis en prison. Un autre épisode s'est produit lorsqu'un espion allemand, Felix Sommerfeld, a infiltré les rangs de Francisco Villa et a convaincu le général mexicain d'exécuter 25 Américains dans l'État de Chihuahua.

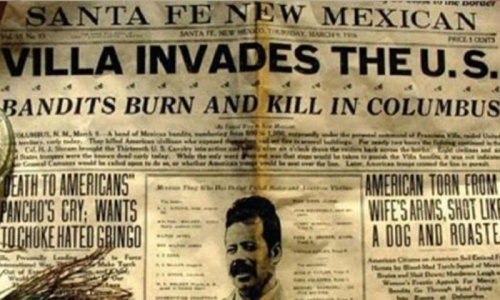

Le journaliste Fernando Moraga a affirmé dans ses reportages pour le journal mexicain "El Universal" en 1974 que l'attaque de Francisco Villa contre Columbus était un acte de guerre pro-allemand.

Lorsque les gringos ont été exécutés sur les ordres de Villa, le président Woodrow Wilson n'a pas déclaré la guerre au Mexique, mais c'est le même espion Felix Sommerfeld qui a planifié l'attaque de Columbus, ceci étant l'une des versions de l'attaque de Columbus (New Mexico, USA) en mars 1916, essayant de provoquer les États-Unis parce qu'ils voulaient que le Mexique entre une guerre contre les États-Unis, pour que ceux-ci ne soient pas impliqués dans la guerre en Europe; si les Allemands ne pouvaient pas obtenir le pétrole, alors ils devaient entretenir le conflit.

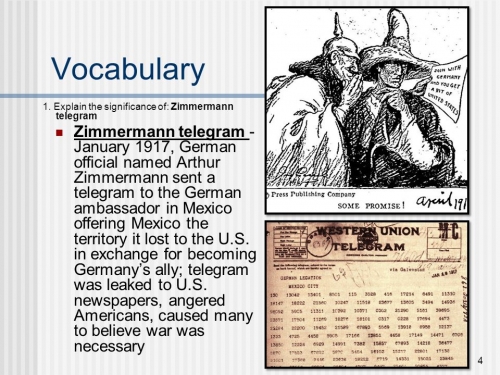

Il existe encore un autre épisode de la tentative allemande de s'immiscer dans la politique mexicaine lorsqu'en 1917. Les Allemands envoient à Venustiano Carranza le célèbre télégramme Zimmermann, dans lequel la chancellerie allemande propose au Mexique d'entrer en guerre du côté de l'Allemagne avec, comme autre allié, l'empire japonais, dans le but d'envahir les États-Unis.

De tout ce que nous avons mentionné, y compris le rejet de l'option allemande, derrière se trouve le magnat anglais qui domine déjà le pétrole mexicain, plus la concurrence entre Rockefeller qui veut dominer le pétrole mexicain et l'empire allemand qui a besoin du pétrole mexicain pour faire sa guerre et possède une grande flotte, qui ne peut fonctionner sans pétrole, et le pétrole de l'empire turc ne coule pas comme prévu parce que les Anglais sont en guerre contre l'empire ottoman. Les Allemands ont donc perdu la guerre sans le pétrole mexicain.

18:19 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, mexique, états-unis, allemagne, télégramme zimmermann, première guerre mondiale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 11 mai 2022

L'alliance entre les chevaliers et le peuple dans la guerre des paysans comme mythe politique dans la révolution conservatrice

L'alliance entre les chevaliers et le peuple dans la guerre des paysans comme mythe politique dans la révolution conservatrice

Giovanni Pucci

Source: https://www.ereticamente.net/2018/03/lalleanza-tra-cavalieri-e-popolo-nella-guerra-dei-contadini-come-mito-politico-nella-rivoluzione-conservatrice-giovanni-pucci.html

Parmi les nombreux thèmes qui ont joué un rôle évocateur dans le mouvement culturel connu sous le nom de "révolution conservatrice", qui a joué un rôle non négligeable en Allemagne dans l'entre-deux-guerres, nous pouvons inclure la "guerre des paysans", cette série d'émeutes qui s'est déroulée entre 1524 et 1526 au cœur du Saint Empire romain germanique et qui a débouché sur quelque chose de bien plus grand avant d'être étouffée dans le sang. Connue dans l'histoire sous le nom de guerre, elle se distingue des révoltes précédentes par le nombre de personnes mobilisées, l'étendue géographique des zones concernées et la nature radicale des revendications. On peut en trouver des anticipations dans la formation de la Bundschuh (ou Ligue de la Botte) en 1513 et dans la révolte de l'Armer Konrad en 1514. Mais son prodrome a sans aucun doute été la "révolte des chevaliers", un mouvement qui a débuté à l'été 1522 et qui a vu 5000 fantassins et 1500 cavaliers sous le commandement d'Ulrich von Hutten et Franz von Sickingen (1481-1523) tenir en échec les mercenaires des évêques de Trèves, Mayence et Cologne avant de capituler en 1523 au siège de Landsstuhl.

Les ressorts sociaux qui ont poussé la petite aristocratie rurale allemande à former une alliance avec les pauvres et les opprimés afin de tenter une réforme radicale du pays et de l'état des choses sont les conditions sociales modifiées qui ont jeté à la rue une classe autrefois puissante au profit de la nouvelle et riche bourgeoisie des villes, des marchands affamés et des familles bancaires de plus en plus influentes qui avaient désormais l'empereur sous leur emprise, réduit à un symbole vide, avec le parasitisme des princes guelfes et un clergé de plus en plus corrompu. C'est probablement cette "alliance populaire" rudimentaire entre certains éléments des classes guerrières et ouvrières contre les couches improductives et les éléments étrangers à la nation germanique (en premier lieu les évêques envoyés par Rome) qui voulaient faire une révolution pour corriger un ordre désormais inversé et non pour accélérer son inversion qui a fasciné les intellectuels allemands qui ont adhéré de diverses manières à la Révolution conservatrice au 20e siècle. La figure de von Sickingen, soldat des Freikorps au XVIe siècle, était gravée dans le cœur de ceux qui aspiraient à une renaissance allemande après l'humiliation de Versailles et la trahison de novembre, la déclaration de reddition proclamée par le gouvernement de Berlin avec l'armée allemande non conquise sur le terrain et les lignes de front profondément enfoncées dans le territoire français. Le leader envisageait l'élimination des princes ecclésiastiques, la création d'une Église authentiquement allemande, l'annulation du commerce bancaire, l'établissement d'un gouvernement tenu par l'empereur avec un conseil composé uniquement de chevaliers : une vision qui unissait idéalement les exigences d'un rang social en déclin, celui des chevaliers, avec celles du peuple, intéressé à combattre les anciens et nouveaux profiteurs sociaux.

La guerre des paysans a commencé en 1524 par une série de soulèvements de paysans qui, au début de l'année suivante, se sont organisés en rangs armés (haufen). Le plus célèbre d'entre eux, le Schwarzer Haufen, était dirigé par l'ancien chef des Lansquenets, Floryan Geyer (1490-1525). Noble de naissance, adepte de la Réforme luthérienne qui avait créé le contexte culturel des révoltes (même si Luther condamnera plus tard violemment les insurgés et leurs intentions), il réclame la restauration du pouvoir impérial, la destitution des princes et la saisie des biens ecclésiastiques. Il meurt le 9 juin 1525, assassiné à Rimpar après avoir échappé à la destruction du château d'Ingolstadt, où il avait organisé la dernière résistance du Bataillon noir. Son nom restera dans la légende.

Une autre figure charismatique reprise par les révolutionnaires-conservateurs au 20e siècle est Gotz von Berlichingen (1480-1562) qui, avec un membre en fer pour remplacer le bras droit perdu au combat en 1508, a mené les rebelles du district d'Odenwald contre les princes du Saint Empire romain germanique. Les noms de Geyer, von Berlichingen, von Hutten et von Sickingen reviennent plusieurs fois dans les écrits d'Arthur Moeller van der Bruck (une figure de proue des Jungkorservativen et un élément central de la RC), de l'historien Friedrich Stieve ou de l'écrivain populaire Hermann Löns. Soit dit en passant, Gotz von Berlichingen et Floryan Geyer, héros connus de toutes les couches de la population, portaient le nom d'autant de divisions de la Waffen SS pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, n'en déplaise à ceux qui nient tout lien entre la Révolution conservatrice et le régime national-socialiste qui a suivi.

L'urbanisation qui a érodé les terres agricoles et laissé les petits propriétaires sans terre et incapables de subvenir à leurs besoins, l'accumulation de capital bancaire par l'usure et les rentes financières, l'appauvrissement progressif et la perte de prestige de l'ancienne noblesse rurale, la corruption et l'arrogance du clergé romain : voilà les conditions qui nous ont permis de voir des bandes de paysans encadrées comme des chevaliers. Avec le passage de l'économie féodale aux premiers balbutiements d'un système capitaliste, une telle agitation sociale est apparue dans les campagnes qu'elle a inévitablement trouvé un exutoire violent. Un débouché qui, après des victoires initiales, s'est arrêté et a été réprimé de manière belliqueuse comme un avertissement à venir. Ainsi, à défaut, la guerre des paysans n'a pas bouleversé l'ordre social mais l'a définitivement consolidé. S'arrêtant aux cas que nous avons mentionnés, la soudure entre le peuple et la tradition nationale n'a pas été complètement réalisée et les 12 thèses qui représentaient les doléances du mouvement sont restées inapplicables, ce dernier se contentant de vendettas personnelles individuelles sur les nobles et leurs propriétés, d'ailleurs limitées aux étapes initiales. L'intérêt commun de restaurer les symboles de justice et de rédemption sociale, à rechercher à travers l'unité du peuple allemand, ne s'est en fait pas concrétisé. Bien que les auteurs de la Révolution conservatrice aient idéalisé les figures mentionnées ci-dessus, ils avaient très clairement cette idée en tête et l'ont couchée sur papier dans leurs écrits qui appelaient à une rédemption nationale-populaire. C'est également de ces suggestions que s'est inspiré le mouvement politique qui a pris le pouvoir en Allemagne, avec un programme qui visait à rectifier les écarts économiques et sociaux de la modernité sans la nier, et qui, par le pragmatisme et la pratique quotidienne, mettait en pratique les théorisations des penseurs qui l'avaient précédé et auxquels un très grand nombre d'entre eux adhéraient, voyant en lui la suite politique logique de leurs idées.

Giovanni Pucci

21:05 Publié dans Histoire, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : guerre des paysans, histoire, allemagne, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 28 avril 2022

Langage clair à la télévision russe: "Les Allemands sont de la chair à canon dans la guerre économique"

Langage clair à la télévision russe: "Les Allemands sont de la chair à canon dans la guerre économique"

Source: https://www.compact-online.de/klartext-im-russischen-fernsehen-deutsche-sind-kanonenfutter-im-wirtschaftskrieg/?mc_cid=3b95b79c94&mc_eid=128c71e308

Les sanctions contre la Russie nuisent énormément à l'UE, mais Bruxelles travaille déjà sur le sixième paquet de sanctions. L'économie allemande, en particulier, ne doit plus servir que de chair à canon dans la guerre économique.

par Thomas Röper

La pression monte au sein de l'UE pour que le pétrole et le gaz russes soient également sanctionnés. En outre, il n'y a pas encore d'accord sur l'opportunité de répondre aux exigences russes de payer le gaz en roubles. La Commission européenne, du moins, a déjà fait savoir qu'elle considérait qu'accepter les conditions russes constituait une violation des sanctions de l'UE à l'encontre de la Russie. Dans la revue hebdomadaire d'actualité de la télévision russe, le correspondant russe en Allemagne a énuméré sans ménagement les problèmes actuels de l'Allemagne dans ce contexte de sanctions. Comme il est toujours intéressant de voir comment la Russie rend compte de la situation politique en Allemagne, j'ai traduit le reportage de la télévision russe.

Début de la traduction :

Les Européens hésitent toujours à payer le gaz russe en roubles. Ils sont trop occupés à inventer un nouveau paquet de sanctions, le sixième, contre la Russie. Même les protestations, l'appauvrissement de leur propre population, la hausse vertigineuse des prix du chauffage, de l'essence et de la nourriture ne les arrêtent pas.

Pas de rouble, pas de gaz

Moscou a déclaré sans ambages: si le paiement n'est pas effectué en roubles, il n'y aura pas de gaz. Jusqu'à présent, seuls quelques pays européens ont accepté de payer le gaz en roubles et de ne pas détruire leur économie. Il s'agit de la Hongrie, de la Bulgarie, de la Moldavie, de la Serbie et de l'Arménie.

Le président allemand Frank-Walter Steinmeier (SPD) tolère jusqu'à présent les insultes de l'ambassadeur ukrainien Andrej Melnyk et garde un calme stoïque.

Pourquoi Steinmeier a-t-il été insulté de la sorte? Depuis mardi soir, lorsqu'il a été annoncé que le président allemand ne pourrait pas se rendre à Kiev, les hommes politiques et les médias allemands analysent les raisons de cette démarche diplomatique. Steinmeier lui-même ne s'est pas exprimé à ce sujet, se limitant aux faits. Il s'est exprimé ainsi :

"Mon collègue et ami, le président polonais Duda, a proposé l'autre jour que nous visitions Kiev avec les présidents de Lettonie, de Lituanie et d'Estonie et que nous envoyions un message de solidarité européenne à l'Ukraine. J'étais prêt à le faire, mais apparemment, je dois prendre acte du fait que ce n'était pas dans l'esprit de Kiev".

En quoi le parrain de l'actuel régime ukrainien a-t-il contrarié ses protégés ? On s'est souvenu du soutien de Steinmeier au Nord Stream 2, de ses contacts avec Moscou et de la formule Steinmeier, de son nom, pour appliquer les accords de Minsk, détestés par Kiev.

"Une insulte qui n'aide aucune partie"

Même le président de la CDU, Friedrich Merz, s'est exprimé :

"J'interprète cette insulte, qui a un arrière-plan politico-historique, comme une réaction émotionnelle des dirigeants ukrainiens qui n'aide aucune partie".

D'autre part, Zelensky n'aurait guère osé insulter l'Allemagne sans consulter - directement ou indirectement - Washington, comme le montre la participation de la Pologne à la provocation. Et bien sûr, la véritable cible n'était pas Steinmeier, mais son camarade de parti, Olaf Scholz. Le chancelier allemand ne veut pas partir à la guerre et, si l'on en croit le diplomate en chef de l'UE, M. Borrell, l'Europe définit le processus dans lequel elle est engagée en Ukraine comme une guerre pour elle-même, sans euphémisme ni demi-teinte.

La rébellion des amis des armes

Le premier reproche fait à Scholz est de ne pas vouloir envoyer d'armes lourdes en Ukraine. Le groupe Reinmetall a décidé de se faire un peu d'argent supplémentaire et a rendu un mauvais service au chancelier en annonçant au monde entier qu'il avait en stock cinq douzaines de chars Leopard 1 obsolètes et une soixantaine de véhicules de combat d'infanterie Marder, eux aussi très anciens, et que ces équipements pouvaient encore être utilisés. Cette nouvelle a provoqué un grand émoi parmi les partenaires de la coalition qui demandent à Scholz de donner son feu vert à ces livraisons.

Le magazine Der Spiegel a fait remarquer ce qui suit :

"Le chancelier est de plus en plus sous pression - à Bruxelles et à Berlin - en raison de sa politique réservée à l'égard de l'Ukraine. Une rébellion a éclaté au sein de la coalition. L'incompréhension grandit dans les rangs des partenaires du chef de gouvernement silencieux et extrêmement faible".

Et Anton Hofreiter, président de la commission des affaires européennes au Bundestag, a fait remarquer :

"Nous ternissons notre réputation aux yeux de tous nos voisins. Nous devons enfin commencer à fournir à l'Ukraine ce dont elle a besoin, y compris des armes lourdes. Et l'Allemagne doit cesser de bloquer l'embargo énergétique, notamment sur le pétrole et le charbon".

"Une zone d'exclusion aérienne franchirait la ligne rouge"

Les Verts allemands ont été si actifs qu'au cours de la semaine, des rumeurs ont effectivement circulé selon lesquelles l'Allemagne était sur le point d'envoyer du matériel dans le Donbass, d'autant plus que des convois militaires se dirigeaient effectivement quelque part vers l'est. Le gouverneur de la région de Mykolaïv a tweeté avec excitation que des chars allemands allaient à nouveau traverser l'Ukraine et tirer sur les Russes. Mais la rumeur n'a pas été confirmée: les images qui ont tant inspiré l'homme politique ukrainien ont apparemment donné au chancelier un sentiment si sombre qu'il a pour l'instant émis un "non" ferme.

Olaf Scholz a en revanche souligné :

"Permettez-moi de le dire encore une fois très clairement. Je suis impressionné par le nombre de personnes qui parviennent à googler rapidement quelque chose et à devenir immédiatement des experts en armes. Bien sûr, dans une telle situation, il y aura toujours quelqu'un pour dire: je veux que les événements se déroulent de cette manière. Mais je voudrais dire à certains de ces garçons et filles: je gouverne le pays précisément parce que je ne fais pas les choses comme vous le voudriez".

Il est clair que par "garçon", Scholz entend le député Hofreiter. Mais par "fille", voulait-il évoquer la ministre des Affaires étrangères Baerbock ? D'ailleurs, tous les Verts ne sont pas contre Scholz. Son allié inattendu sur la question de la livraison d'armes lourdes était l'un de leurs leaders, le ministre de l'Économie Habeck. Comme on pouvait s'y attendre, le respecté ministre-président chrétien-démocrate de Saxe, Michael Kretschmer, s'est également rangé du côté de Scholz.

Il a déclaré :

"Nous franchirions une limite si nous fournissions des chars ou des avions, ou même si nous établissions une zone d'exclusion aérienne. Cette ligne doit être maintenue".

Aller en Biélorussie pour faire le plein

Une concession au "parti de la guerre" a été la décision de Scholz d'augmenter immédiatement les dépenses de défense de deux milliards d'euros - dont une grande partie pour l'achat d'armes pour l'armée ukrainienne, qui ne nécessitent pas une longue formation. Cependant, pour satisfaire la deuxième exigence, M. Scholz a besoin de beaucoup plus d'argent et surtout de ce dont il dispose le moins - du temps. Les partenaires demandent un embargo sur l'énergie. La décision a été prise pour le charbon - les importations doivent cesser à la mi-août - mais comment vivre sans pétrole russe ?

Le ministre lituanien des Affaires étrangères, Gabrielius Landsbergis, a quant à lui déclaré:

"Nous commençons maintenant à travailler sur le sixième paquet de sanctions. Avec des options sur le pétrole. Cela signifie que nous avons déjà commencé à travailler pour parvenir à un consensus, et j'espère que cette fois-ci, nous y arriverons".

Rien que des mots

En tout cas, cela va marcher. En fait, tout a déjà fonctionné dans le pays dont la diplomatie est dirigée par M. Landsbergis, sauf qu'on n'entend plus parler de l'industrie lituanienne depuis longtemps et que les citoyens vont faire le plein en Biélorussie.

On peut dire que l'Allemagne, son économie et ses ménages, n'apprécieront pas une telle victoire sur les Russes. De plus, l'OPEP a fortement déçu cette semaine; l'Organisation des pays exportateurs de pétrole ne sera pas en mesure de compenser le retrait de la Russie du marché et l'agence de notation Moody's prévoit que, dans ce cas, le prix du pétrole atteindra immédiatement 160 dollars le baril. Berlin veut élaborer une stratégie progressive de sortie du pétrole russe, mais ce ne sont pour l'instant que des mots.

La situation sur le marché du gaz est encore plus incertaine et menace de diviser l'UE - la date limite pour le passage au rouble approche. La Commission européenne a émis cette semaine un avis selon lequel cela serait contraire à la politique de sanctions de l'UE, qui vise à dévaluer la monnaie russe. On ne peut que constater: oui, l'UE a un gros problème avec cette partie des sanctions.

Ainsi, le chancelier autrichien Karl Nehammer a déclaré :

"L'Autriche n'est pas seule à s'opposer à l'embargo sur le gaz. L'Allemagne, la Hongrie et d'autres États membres de l'UE sont du même avis. D'autre part, l'Autriche soutient fermement, avec les États de l'UE, les sanctions contre la Russie. Mais les sanctions devraient frapper la Russie plus durement que l'UE".

Et le ministre hongrois des Affaires étrangères Péter Szijjártó a déclaré :

"Pour nous, il y a une ligne rouge: la sécurité énergétique de la Hongrie. C'est pourquoi nous avons décidé que nous ne pouvions pas signer de sanctions contre le pétrole et le gaz".

Lutte pour le gaz du Qatar

Si l'approvisionnement en gaz russe est interrompu, l'économie allemande perdra environ 220 milliards d'euros au cours des deux prochaines années. Elle les perdrait même si elle trouvait une sorte de substitut pour les volumes supprimés, car il n'y aura jamais de prix aussi avantageux que ceux que Gazprom peut offrir. Le GNL australien ou colombien ne peut pas coûter la même chose que le gaz de pipeline russe. D'ailleurs, la Chine a plus que quintuplé ses achats de GNL par rapport à l'année dernière, ce qui signifie qu'il y aura également une bataille pour le gaz du Qatar. Dans l'ensemble, une autolimitation et une économie strictes seront la clé de sa survie dans les années à venir.

Robert Habeck, ministre de l'Économie et vice-chancelier de la République fédérale d'Allemagne, a déclaré :

"Je demande à chacun de faire sa part pour économiser l'énergie. A titre indicatif, j'essaierais d'économiser 10 pour cent, c'est faisable. Si vous chauffez votre appartement et fermez les rideaux le soir, vous pouvez économiser jusqu'à 5 pour cent d'énergie. Et si vous baissez la température de la pièce d'un degré, cela représente environ 6 pour cent. Bien sûr, ce n'est pas très confortable, mais personne n'aura froid. Une situation dans laquelle il y aurait des problèmes d'approvisionnement ou des entreprises qui devraient fermer serait un cauchemar politico-économique".

Il appelle ses concitoyens à économiser presque chaque semaine, c'est-à-dire avec la même fréquence que celle avec laquelle la Grande-Bretagne, par exemple, ment. Pour maintenir la folie des sanctions sur le continent, National Grid promet d'augmenter le transit du gaz produit en Norvège, mais on a pu voir comment la Grande-Bretagne se comporte réellement en cas de crise au plus fort de la pandémie, lorsqu'elle a réussi à faire passer tous les vaccins sous le nez de la Commission européenne. Et la Grande-Bretagne connaît déjà une crise du carburant. L'inflation explose, elle a atteint 7% en mars. Du jamais vu depuis 30 ans. Et cela vaut pour toute l'Europe.

Christine Lagarde, la présidente de la Banque centrale européenne, s'est exprimée à ce sujet :

"L'inflation a atteint 7,5 pour cent en mars, contre 5,9 pour cent en février. Les prix de l'énergie ont augmenté depuis le début de la guerre et sont maintenant 45 pour cent plus élevés qu'il y a un an".

Vers une pauvreté assistée

Friedrich Merz en est convaincu:

"De toute façon, le sommet de notre prospérité est probablement derrière nous depuis longtemps. La situation devient de plus en plus difficile. Ce n'est pas seulement moi, en tant que chef de l'opposition, mais aussi le chancelier Olaf Scholz qui doit le dire à la population".

La fin de l'ère de la prospérité, il est amusant que ce diagnostic soit posé par le multimillionnaire et président du parti CDU, qui représente les intérêts des moyennes et grandes entreprises. Mais sur le fond, le pessimisme public est juste. L'inflation en Allemagne est déjà perçue par les consommateurs comme étant de 14%, soit le double de ce qu'elle est en réalité, ce qui signifie que le niveau de frustration augmente plus rapidement que le niveau de vie réel ne diminue. Et c'est là que diverses pensées malheureuses viennent à l'esprit.

Le Süddeutsche Zeitung écrit ainsi :

"Quel est le double standard aujourd'hui ? Il s'agit de condamner l'attaque russe, mais de refuser l'embargo sur le gaz. Il s'agit de condamner la guerre en Europe, mais de ne pas voir la guerre dans le reste du monde. C'est condamner la propagande russe, mais rester silencieux sur la guerre en Irak, qui a été déclenchée sur des mensonges. Il s'agit de diaboliser le gaz de Poutine, mais de ramper devant les Émirats. Et il faut en tout cas admettre comment on a été induit en erreur par Poutine, par les exigences démesurées de la Russie et par l'âme russe elle-même".

La citation du journal allemand sonne comme une invitation à réfléchir à ses propres erreurs.

Et bien sûr, on peut réfléchir, mais on ne peut rien changer. Le naufrage est un sentiment qui se répand lentement dans la société allemande. La situation avec Steinmeier, les accusations constantes de faiblesse contre le chancelier Scholz, la fissure au sein de la coalition, la pression de ceux qui considèrent les Allemands comme des alliés - on commence à comprendre son propre rôle dans le conflit entre l'Occident et la Russie. Pour le dire sans détour : même une guerre économique a besoin de chair à canon.

Fin de la traduction

12:16 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, europe, affaires européennes, sanctions, sanctions antirusses, gaz |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

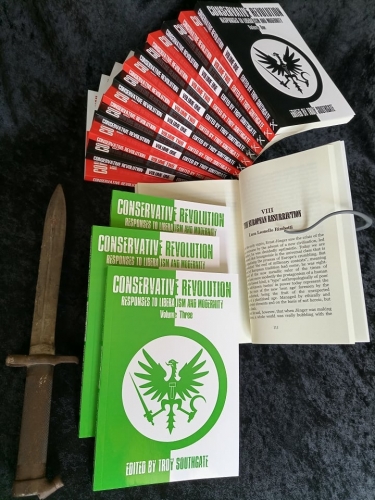

Volume Four of CONSERVATIVE REVOLUTION: RESPONSES TO LIBERALISM AND MODERNITY

As the first three volumes in this series have demonstrated, the Revolutionary Conservative milieu of 1920s, 1930s and 1940s Germany continues to fascinate and inspire those of us living in the first quarter of the twenty-first century. Thanks to our diligent translator, Robert Steuckers, as well as a host of other prestigious writers, Black Front Press is now in a position to offer readers a fourth volume on this topic and one which matches the high standard that was set by its predecessors.

Chapters include Ernst Jünger and the Conservative Revolution; Spengler's Criticism of Marx is That He Did Not Understand Modern Capitalism; Ernst von Salomon: Memorialist of the German Conservative Revolution; Terra Sarda: Ernst Jünger's Metaphysical Mediterranean; Under Occupation: Ernst Röhm in the Bavarian Soviet Republic; Ernst Jünger: Decipherer and Memorialist; Spengler and the Russian Soul: Ancient Russia and Enlightenment "Pseudomorphosis; Ernst Jünger: Between Panic, System and Rebellion; Oswald Spengler: From "Stur" Magazine, 1937; Ernst Niekisch and the "Kingdom of Demons"; The Atlantic Journey of the Unpublishable Jünger; The Constraints of Ernst von Salomon; and Ernst Jünger Between Technophile Modernity and a Return to the Natural. The contributors include Troy Southgate (Editor), Robert Steuckers, Adriano Romualdi, Francesco Lamendola, Andrea Scarabelli, Francis Bergeron, Luc-Olivier d'Algange, Stefano Arcella, Nicolas Bonnal, Roger Hervé, Daniele Perra and Markus Klein.

10:33 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : révolution conservatrice, livre, troy southgate, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Le général de brigade à la retraite Erich Vad: il règle maintenant ses comptes avec les écolos fauteurs de guerre

Le général de brigade à la retraite Erich Vad: il règle maintenant ses comptes avec les écolos fauteurs de guerre

Par Sven Reuth

Source: https://www.compact-online.de/brigadegeneral-a-d-erich-vad-jetzt-rechnet-er-mit-gruenen-kriegstreibern-ab/?mc_cid=3b95b79c94&mc_eid=128c71e308

Une escalade de la guerre en Ukraine comporte d'énormes risques pour l'Allemagne. C'est ce que le général de brigade à la retraite Erich Vad n'a cessé de rappeler ces dernières semaines. Il s'est exprimé clairement sur le bellicisme des Verts.

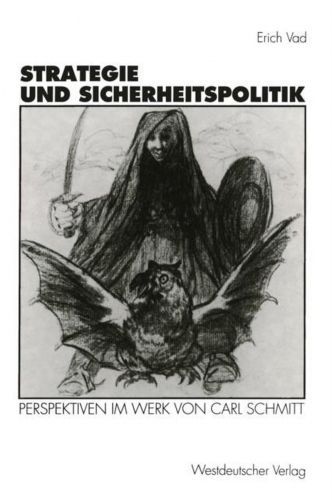

Erich Vad est un homme qui possède la plus grande expérience et a occupé les plus hauts postes de direction. De 2006 à 2013, il a été chef de groupe à la Chancellerie fédérale, secrétaire du Conseil fédéral de sécurité et conseiller en politique militaire de la chancelière Angela Merkel. Cette ascension a été possible malgré le fait que Vad ait donné en 2003 une conférence à l'Institut für Staatspolitik sur le thème "Le maintien de la paix et la géopolitique dans la pensée de Carl Schmitt". En 1996, Vad avait déjà publié le livre Stratégie et politique de sécurité. Perspectives dans l'œuvre de Carl Schmitt.

"Nous n'avons pas besoin d'une guerre par procuration"

Il y a deux semaines à peine, Vad avait déjà provoqué un scandale selon l'ambassadeur ukrainien Melnyk parce que, dans une interview accordée à Die Welt, il ne voulait pas attribuer à Poutine une intention de bombarder une clinique et faisait en outre référence au nombre élevé de victimes que les guerres menées par l'Occident avaient fait au cours des dernières décennies. Son message principal à l'époque était le suivant:

"Si nous ne voulons pas de la troisième guerre mondiale, nous devrons tôt ou tard sortir de cette logique d'escalade militaire et entamer des négociations".

Hier, dans le talk-show Maybritt Illner, Erich Vad a de nouveau suscité l'irritation en critiquant à la fois la ligne belliciste des Verts et l'attitude complètement naïve de la majorité de la société allemande face à une éventuelle escalade de la guerre en Ukraine. Son message de base était que l'établissement d'un cessez-le-feu rapide devrait être prioritaire par rapport à la question de savoir quel camp remporterait la victoire à la fin.

Vad a déclaré à ce sujet:

"Nous n'avons pas besoin en Europe centrale d'une guerre par procuration pendant des années, qui a le potentiel de dégénérer en guerre nucléaire".

"Nous ne voulons pas d'une victoire de l'Ukraine"

Toute "rhétorique guerrière" devrait être évitée. Afin de montrer clairement que la négociation rapide d'un cessez-le-feu et la recherche d'une solution politique à long terme au conflit sont prioritaires, aussi le gouvernement allemand devrait enfin déclarer :

"Nous ne voulons pas la victoire de l'Ukraine".

Il s'est montré particulièrement critique à l'égard du rôle actuel des Verts dans la politique fédérale. Il a déclaré à ce sujet :

"Ce qui me dérange, c'est quand les politiciens des Verts présentent les solutions militaires comme l'objectif ultime. C'est complètement fou ! Ce sont des politiciens Verts qui ont refusé et condamné le service militaire à l'époque !"

Vad avait déjà déclaré dans son interview à Die Welt qu'il estimait totalement erroné de dénier au président russe son humanité et de le qualifier de despote pathologique avec lequel personne ne peut plus parler. Après tout, il y a eu dans un passé récent d'autres guerres terribles et contraires au droit international, en Irak, en Syrie, en Libye et en Afghanistan, menées par des puissances occidentales.

Voici revenu le temps du nazisme

La bulle de gauche libérale et woke de Twitter est déjà en ébullition suite aux déclarations de Vad. On y fait notamment référence à un texte de Vad paru il y a 19 ans dans le magazine intellectuel de droite Sezession pour justifier l'interdiction imposée à cet expert patenté de participer à un talk-show. Si la campagne devait aboutir, l'un des rares critiques de la guerre encore en vie disparaîtrait de la scène publique.

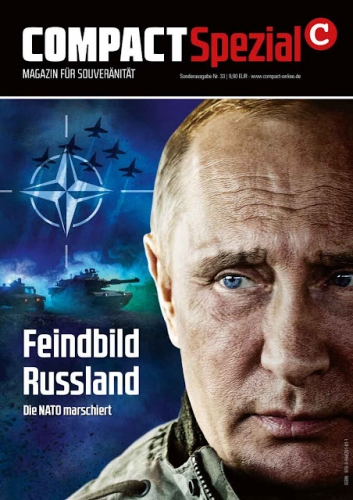

COMPACT-Spécial "L'image de l'ennemi russe - L'OTAN en marche" fournit les arguments pour un nouveau mouvement pour la paix. L'Allemagne doit rester neutre dans le conflit ukrainien - c'est la seule façon de protéger notre pays ! Commandez ici: https://www.compact-shop.de/shop/compact-spezial/compact-... !

10:25 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, ukraine, allemagne, verts, écologistes, erich vad, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 26 avril 2022

Bismarck entre tradition et innovation: les discours du chancelier de fer

Bismarck entre tradition et innovation: les discours du chancelier de fer

Giovanni Sessa

Source: https://www.paginefilosofali.it/bismarck-tra-tradizione-e-innovazione-i-discorsi-del-cancelliere-di-ferro-giovanni-sessa/

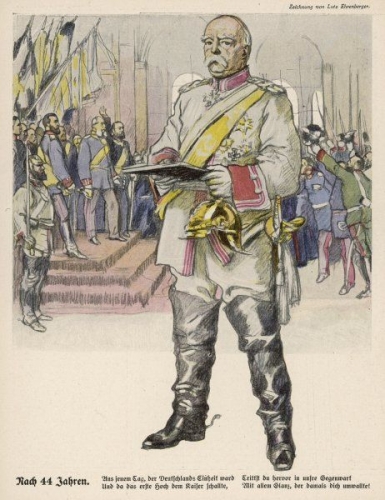

Otto von Bismarck est sans aucun doute un personnage historique de grande importance. Ses choix politiques ont conditionné non seulement l'histoire de l'Allemagne moderne, mais aussi les événements de la première moitié du 20e siècle. Afin de mieux connaître l'homme et le chancelier, nous vous recommandons vivement la lecture d'un de ses livres, Kulturkampf. Discorsi politici, récemment en librairie par la maison d'édition Oaks (pour les commandes : info@oakseditrice.it, pp.291, €24.00). Le volume est enrichi par la préface clarifiante du germaniste Marino Freschi. Né en 1815, une année fatidique pour le destin de l'Europe, Bismarck, comme le note la préface, "est resté attaché aux racines de l'aristocratie foncière" (p. I). Dans sa jeunesse, ses débuts dans l'administration prussienne ne sont pas brillants. Il a été impliqué dans un certain nombre de scandales et a mené une vie inconvenante. Cependant, ce n'était qu'un moment passager: bientôt, la spiritualité piétiste, basée sur la dévotion mystique et visant l'éveil intérieur, s'enracine dans son âme.

Dans les cercles piétistes, il a rencontré sa femme et quelques futurs collaborateurs. Parmi eux se trouvait von Roon, qui l'a introduit dans le cercle du futur Wilhelm I. Son éducation politique et culturelle a eu un impact sur sa vie. Son éducation politique et culturelle culmine dans sa fréquentation du cercle conservateur animé par les frères von Gerlach. Il acquiert une expérience administrative au niveau municipal et provincial jusqu'à ce que, après l'accession de Wilhelm Ier au trône en 1862, il soit appelé à la Diète de Francfort en tant que représentant du souverain. Ses discours étaient caractérisés par un esprit anti-révolutionnaire et démontraient ses qualités oratoires incontestables, comme le montre le livre que nous présentons ici. L'art oratoire de Bismarck, tout en montrant en maints endroits la vaste culture du chancelier, avec des références à Goethe, Lessing, Schiller, Heine, son auteur préféré plus que tout autre, était direct: " il était fondé sur la franchise et l'attaque [...] au-delà de toute pratique rhétorique" (p. III). Il a toujours été conscient du lien entre les choix de politique intérieure et étrangère, en raison de son long séjour en tant qu'ambassadeur à Saint-Pétersbourg et, pour une période plus courte, à Paris. Il se trouvait dans la capitale française lorsqu'il a été rappelé par le nouveau monarque, qui lui a confié la chancellerie.

Dans les cercles piétistes, il a rencontré sa femme et quelques futurs collaborateurs. Parmi eux se trouvait von Roon, qui l'a introduit dans le cercle du futur Wilhelm I. Son éducation politique et culturelle a eu un impact sur sa vie. Son éducation politique et culturelle culmine dans sa fréquentation du cercle conservateur animé par les frères von Gerlach. Il acquiert une expérience administrative au niveau municipal et provincial jusqu'à ce que, après l'accession de Wilhelm Ier au trône en 1862, il soit appelé à la Diète de Francfort en tant que représentant du souverain. Ses discours étaient caractérisés par un esprit anti-révolutionnaire et démontraient ses qualités oratoires incontestables, comme le montre le livre que nous présentons ici. L'art oratoire de Bismarck, tout en montrant en maints endroits la vaste culture du chancelier, avec des références à Goethe, Lessing, Schiller, Heine, son auteur préféré plus que tout autre, était direct: " il était fondé sur la franchise et l'attaque [...] au-delà de toute pratique rhétorique" (p. III). Il a toujours été conscient du lien entre les choix de politique intérieure et étrangère, en raison de son long séjour en tant qu'ambassadeur à Saint-Pétersbourg et, pour une période plus courte, à Paris. Il se trouvait dans la capitale française lorsqu'il a été rappelé par le nouveau monarque, qui lui a confié la chancellerie.

Dès son premier discours parlementaire, il a exprimé clairement ses idées. L'avenir de la Prusse "devait être réalisé non pas avec des discours, mais par "le fer et le feu", suggérant que l'unification allemande ne serait possible qu'avec une Prusse en armes" (p. V). En 1863, il soutient la répression tsariste des soulèvements polonais. L'opinion publique libérale se dresse alors, ce qui provoque l'affaiblissement politique de Bismarck pendant un moment et conduit à la réapparition des ambitions hégémoniques de François-Joseph.

Avec l'habileté d'un grand stratège, le chancelier s'est rapproché de l'Autriche à l'occasion de la guerre avec le Danemark pour la crise des duchés de Schleswig et de Holstein, mais a ensuite fait déclarer la guerre à son allié dans ce qui est pour nous la troisième guerre d'indépendance: "L'empire séculaire des Habsbourg a été démantelé en quelques batailles" (p. VI). Après la victoire, le chancelier a eu le mérite d'apaiser le désir d'anéantir l'Autriche qui grandissait dans les milieux militaires. Afin de devenir la puissance hégémonique en Europe et de procéder à l'unification allemande, la France doit être vaincue. Le signal a été fourni par la crise dynastique espagnole. Bismarck modifie la dépêche d'Ems rédigée par Wilhelm Ier et lui donne une tournure péremptoire.

La France, malgré une tentative du prudent Thiers pour apaiser les esprits, déclare la guerre et subit une défaite retentissante. La nation française, pendant des décennies, a vu monter les esprits de la revanche alors qu'elle se sentait au bord de la fin: désemparée par la défaite militaire et les troubles de la Commune. Pendant ce temps, le Second Reich est en fait né. Wilhelm devient empereur d'Allemagne, couronné à Versailles le 18 janvier. Malgré cela, le chancelier n'a jamais baissé la garde contre la France, convaincu que seul un renforcement militaire allemand garantirait la stabilité politique sur le continent. Selon lui, l'Alsace et la Lorraine sont stratégiquement importantes pour la défense de l'Allemagne. Il devient ainsi un défenseur de l'autonomie alsacienne, déclarant: "plus les habitants de l'Alsace se sentiront alsaciens, plus ils cesseront d'utiliser le français" (p. XVI). Le Kulturkampf, mené contre l'Église catholique et le "Parti du Centre", aliène les sympathies des Alsaciens, fidèles à l'Église de Rome. Cette bataille était essentiellement un conflit de pouvoir: "c'est la lutte entre la monarchie et le sacerdoce [...] Le but qui a toujours clignoté devant les yeux de la papauté était la soumission du pouvoir séculier au spirituel" (p. XVIII). Bismarck, en tant que piétiste, voyait l'autorité divine incarnée par le roi.

Ce n'est qu'avec l'accession de Léon XIII à la papauté qu'un rapprochement s'opère entre les parties. Après s'être mis en congé de la politique, Bismarck fait un retour en force sur la scène publique avec la promulgation de lois anti-socialistes. Influencé par Lassalle et les "socialistes de la chaire", afin d'ôter toute marge de manœuvre aux sociaux-démocrates, il promeut une législation sociale d'avant-garde, annoncée dans son discours du 15 février 1884. En 1883, il avait introduit une loi prévoyant une assurance contre la maladie, en 1884 pour les accidents du travail, et en 1889 pour l'invalidité et la vieillesse. Une sorte de socialisme d'État, de "socialisme prussien", ou, comme l'a dit le chancelier, de "christianisme pratique".

La politique de Bismarck évolue entre deux pôles, qu'il parvient à intégrer de manière dialectique, la tradition et l'innovation. Lorsque les milieux industriels allemands, qui auraient voulu que le Reich s'implique dans la politique coloniale, se sont débarrassés de lui, avec la complicité de Guillaume II, il a cédé la place, comme le confirme ce recueil de discours, celle d'un homme politique d'une grande profondeur, dont l'Europe aurait encore besoin.

Giovanni Sessa.

18:15 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : bismarck, livre, histoire, allemagne, 19ème siècle |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Après la conquête de la mer d'Azov

Après la conquête de la mer d'Azov

par Federico Dezzani

Source: https://www.ariannaeditrice.it/articoli/dopo-la-conquista-del-mare-di-azov & Federico Dezzani

Au 57e jour de la guerre russo-ukrainienne, le ministère russe de la Défense a annoncé la conquête de la ville de Marioupol. Il est temps d'analyser comment la campagne militaire a évolué au cours des deux derniers mois, comment elle pourrait évoluer dans un avenir proche et, surtout, quelles seront ses répercussions internationales: il est de plus en plus évident que les puissances anglo-saxonnes veulent utiliser le conflit pour affaiblir la Russie et, en même temps, déstabiliser l'Allemagne et l'Italie.

Une guerre par procuration tous azimuts

Un peu moins de deux mois après le début des hostilités russo-ukrainiennes, le ministère russe de la Défense a annoncé la conquête de la ville de Marioupol, qui compte environ 400.000 âmeset est située sur le littoral de la mer d'Azov: seul le grand complexe sidérurgique, qui fait partie du kombinat de l'acier construit dans le Donbass dans les années 1930, reste encore aux mains des troupes ukrainiennes désormais clairsemées, mais sa chute est une question de temps. La Russie a donc obtenu un premier résultat stratégique tangible: elle a recréé un pont terrestre avec la péninsule de Crimée (annexée en 2014) et transformé la mer d'Azov en un lac intérieur. Les frontières russes sont donc revenues, sur le front sud, à la conformation de la première moitié du XVIIIe siècle, lorsque l'empire tsariste a réussi à arracher la mer d'Azov aux Turcs et à entrer dans les mers chaudes.

Il est particulièrement utile de reconstituer comment la Russie est parvenue à ce résultat en l'espace de deux mois. Dans notre analyse effectuée au "jour -1", nous avions supposé une campagne militaire de grande envergure, d'une durée de 30 à 40 jours, qui conduirait les Russes jusqu'au Dniepr et à partir Odessa jusqu'au Dniestr. Les faits montrent toutefois que cette option, une campagne militaire de grande envergure sur le territoire ukrainien, n'a jamais été envisagée par les stratèges russes qui pensaient à tort pouvoir se limiter à une "opération militaire spéciale" aux fins éminemment politiques, à savoir le renversement du gouvernement Zelensky et l'avènement d'une junte militaire qui rétablirait la coopération traditionnelle entre la Russie et l'Ukraine. Appeler les opérations qui ont duré du 25 février au 31 mars la "bataille de Kiev" est erroné: on peut tout au plus parler d'une "intimidation de Kiev", car les Russes n'ont jamais envisagé de conquérir la ville dans cette phase de la guerre. La "première phase" de la campagne militaire peut être résumée par l'appel lancé par Poutine aux militaires ukrainiens le 26 février 2022 pour qu'ils prennent le pouvoir et se débarrassent de la "bande de drogués et de néonazis", facilitant ainsi le début des négociations.

Ces calculs se sont révélés erronés, car Moscou a sous-estimé le degré de pénétration des puissances anglo-saxonnes dans l'appareil ukrainien: en huit ans (le temps écoulé entre la révolution colorée de 2014 et aujourd'hui), Londres et Washington ont eu les moyens de s'insinuer jusque dans le coin le plus caché de l'État et de l'armée ukrainiens, éliminant les éléments qui auraient pu accepter l'appel de Poutine et renverser Zelensky. À ce moment-là, les Russes se sont retrouvés dans une position militaire aussi inconfortable qu'improductive: une tête de pont autour de Kiev, alimentée avec de grandes difficultés logistiques par la Biélorussie et exposée à la guérilla des nationalistes ukrainiens. Tant qu'il y avait la possibilité d'un règlement politique du conflit (les négociations tenues en Biélorussie puis en Turquie), les Russes sont restés aux portes de Kiev. Une fois ce scénario écarté, ils se sont retirés en bon ordre du nord de l'Ukraine pour poursuivre des objectifs militaires plus concrets dans le sud-est de l'Ukraine: c'est la "phase deux", annoncée dans les derniers jours de mars. La nomination du général Aleksandr Dvornikov, déjà en charge des opérations militaires en Syrie, comme commandant unique du front ukrainien, annoncée le 9 avril, peut être considérée comme le tournant de la campagne, qui prend de moins en moins de connotations politiques et de plus en plus de connotations militaires. Il convient toutefois de noter que deux mois après l'ouverture du conflit, la Russie ne s'était pas encore lancée dans la destruction systématique des infrastructures ukrainiennes, qui, si une approche purement militaire avait été suivie, aurait dû avoir lieu dès les premières heures de la campagne.

La conquête de Mariupol (avec ses aciéries, photo ci-dessus) annoncée le 21 avril, avec le déploiement consécutif des troupes engagées dans la ville, devrait être le prodrome de la déjà célèbre "bataille du Donbass", dont les Russes ont jeté les bases en conquérant, le 24 mars, le saillant d'Izyum: sur le papier, elle se préfigure ainsi comme une grande tenaille qui, partant du nord et du sud, devrait se refermer sur la ville de Kramatosk. Les avantages que pourraient obtenir les Russes seraient multiples: la destruction de l'armée ukrainienne concentrée depuis le début des hostilités dans le Donbass (estimée à environ 40.000-60.000 unités) et l'affinement des futures frontières, de manière à rendre compacte la région à annexer à la Russie. Quoi qu'il en soit, même en cas de défaite sévère de l'armée ukrainienne, il est peu probable que la "bataille du Donbass" marque la fin des hostilités.

Les puissances anglo-saxonnes ont intérêt à prolonger le conflit le plus longtemps possible et, à cette fin, s'apprêtent à déverser de plus en plus d'armes en Ukraine pour alimenter la "résistance". Le Royaume-Uni, en particulier, qui joue un rôle de premier plan en Ukraine, comme en témoigne le voyage de Johnson à Kiev le 9 avril, a promis d'envoyer des instructeurs, de l'artillerie, des missiles anti-navires Harpoon et même des véhicules blindés pour transporter les systèmes anti-aériens Starstreak. Cet activisme britannique s'explique par le fait que dans la "troisième guerre mondiale" menée par les puissances anglo-saxonnes contre les puissances continentales pour le contrôle du Rimland, le quadrant européen de l'Eurasie a été mis entre les mains de Londres, tandis que Washington et Canberra doivent se concentrer sur le Pacifique et la Chine.

Qu'est-ce que les puissances anglo-saxonnes espèrent gagner en prolongeant jusqu'au bout la guerre en Ukraine, à créer une nouvelle "Syrie" au cœur de l'Europe? Comme nous l'avons souligné à plusieurs reprises dans nos analyses, toute compréhension géopolitique des événements actuels doit englober l'Eurasie dans son ensemble et donc l'axe horizontal Chine-Russie-Allemagne (avec ses nombreuses branches verticales en Birmanie, au Pakistan, en Iran, en Italie, etc.). En prolongeant le conflit pour au moins toute l'année 2022, en jetant de plus en plus d'armes létales sur le théâtre ukrainien, les puissances maritimes anglo-saxonnes espèrent :

- affaiblir davantage la Russie, de manière à rendre possible la chute de Poutine et la relocalisation stratégique du pays dans une fonction anti-chinoise (ou du moins la disparition de la Russie en tant que facteur de puissance, dans le sillage d'une crise politique et d'un effondrement socio-économique) ;

- mener à bien la déstabilisation de l'Europe, en mettant un accent particulier sur l'Allemagne et l'Italie.

A plusieurs reprises, en effet, il a été souligné que les objectifs anglo-saxons de la guerre en Ukraine se situaient sur deux fronts: le russe et l'allemand. Les invectives de plus en plus violentes de Zelensky à l'encontre des dirigeants allemands, coupables de ne pas fournir suffisamment d'armes et de faire obstacle à l'embargo total sur la Russie, illustrent bien ce phénomène. En exacerbant le conflit en Ukraine et en le faisant traîner jusqu'à l'automne prochain, les Anglo-Américains espèrent imposer le blocus convoité sur les approvisionnements énergétiques en provenance de Russie, plongeant ainsi l'Allemagne et l'Italie, qui sont les plus dépendantes du gaz russe, dans une récession économique grave et prolongée. À ce moment-là, l'"axe médian" de l'Europe, qui a son prolongement naturel en Algérie et qui tend naturellement à converger vers la Russie et la Chine, serait jeté dans le chaos ou, du moins, sérieusement affaibli, également parce que les Anglo-Saxons travaillent activement à faire de la terre brûlée partout où les Italiens et les Allemands peuvent s'approvisionner, en Libye comme en Angola. Chaque missile Starstreak envoyé par les Britanniques en Ukraine est un missile visant à laisser l'Allemagne et l'Italie sans énergie: tout porte à croire que l'automne 2022 sera l'un des plus difficiles de mémoire d'homme.

16:03 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, ukraine, géopolitique, mer d'azov, mer noire, espace pontique, russie, allemagne, italie, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 25 avril 2022

Nord Stream 2, une des clés de la guerre en Ukraine

Nord Stream 2, une des clés de la guerre en Ukraine

Daniel Miguel López Rodríguez

Source: https://posmodernia.com/nord-stream-2-una-de-las-claves-de-la-guerra-de-ucrania/

Le flux du Nord

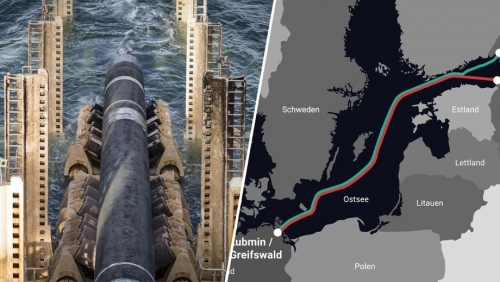

Le sous-sol ukrainien contient un réseau de gazoducs par lequel passe une partie de l'approvisionnement russe vers l'Europe. Entre 2004 et 2005, 80 % du gaz russe destiné à l'Europe a transité par le sous-sol ukrainien. Lorsque Gazprom (le géant russe de l'énergie appartenant à l'État) a interrompu l'approvisionnement des Ukrainiens en janvier 2006 et en janvier 2009, ces derniers ont saisi le gaz destiné à l'Europe, ce qui a entraîné des pertes énormes pour ces pays, qui sont très dépendants du gaz russe, et a jeté un sérieux discrédit sur la Russie en tant que fournisseur.

Afin d'éviter ce transit ukrainien, les Russes ont décidé de construire deux nouveaux gazoducs. Gazprom a fait valoir que le fait de relier un gazoduc directement à l'Allemagne sans avoir besoin de passer par des pays de transit permettrait d'éviter que les exportations de gaz russe vers l'Europe occidentale ne soient coupées, comme cela s'est produit deux fois auparavant. C'est ainsi qu'est né le projet Nord Stream (Севеверный поток), un gazoduc qui relierait la Russie à l'Europe (directement à l'Allemagne via la mer Baltique) sans devoir passer par l'Ukraine ou la Biélorussie.

En avril 2006 déjà, le ministre polonais de la défense, Radek Sikorski, comparait les accords sur la construction d'un gazoduc au pacte de non-agression germano-soviétique, le pacte Ribbentrop-Molotov signé aux premières heures du 24 août 1939, car la Pologne est particulièrement sensible aux accords passés par-dessus sa tête (https://www.voanews.com/a/a-13-polish-defense-minister-pi... ). Tout pacte conclu par la Russie et l'Allemagne y fera penser et sera diabolisé (telle est la simplicité de la propagande, mais elle est tout aussi efficace non pas en raison du mérite des propagandistes mais du démérite du vulgaire ignorant, qui abonde).

Le ministre suédois de la défense, Mikael Odenberg, a indiqué que le projet constituait un danger pour la politique de sécurité de la Suède, car le gazoduc traversant la Baltique entraînerait la présence de la marine russe dans la zone économique de la Suède, ce que les Russes utiliseraient au profit de leurs renseignements militaires. En fait, Poutine justifierait la présence de la marine russe pour assurer la sécurité écologique.