Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

1. Introduction

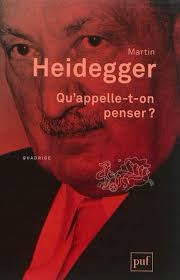

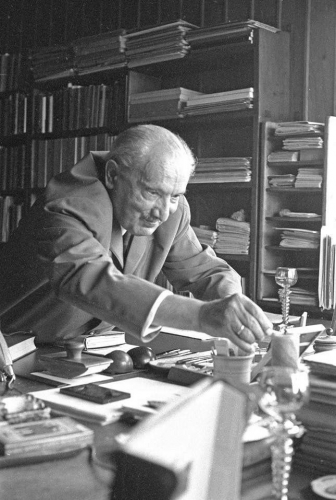

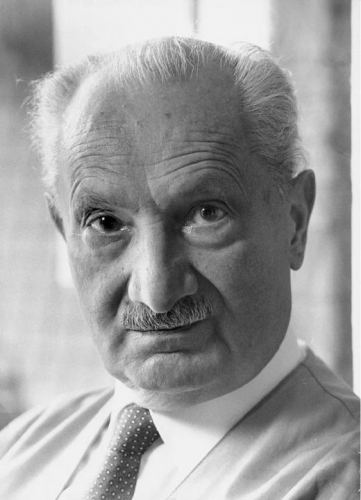

Those on the New Right are bound together partly by shared intellectual interests. Ranking very high indeed on any list of those interests would be the works of Martin Heidegger and those of the Traditionalist [1] [2] school, especially René Guénon and Julius Evola. My own work has been heavily influenced by both Heidegger and Traditionalism. Indeed, my first published essay (“Knowing the Gods [3]”) was strongly Heideggerian, and appeared in the flagship issue of Tyr [4], a journal that describes itself as “radical traditionalist,” and that I co-founded. This is just one example; many of my essays have been influenced by both schools of thought.

In my work, I have made the assumption that Heidegger’s philosophy and Traditionalism are compatible. This assumption is shared by many others on the Right, to the point that it is sometimes tacitly believed that Heidegger was some kind of Traditionalist, or that Heidegger and the Traditionalists had common values and, perhaps, a common project. These assumptions have never really been challenged, and it is high time to do so. The present essay puts into question the Heidegger-Traditionalism relationship.

Doing so will allow us to accomplish three things, at least:

(a) Arrive at a better understanding of Heidegger. This is vital, for my own study of Heidegger (in which I have been engaged, off and on, for over thirty years) has convinced me that he is not only the essential philosopher for the New Right, he is the only great philosopher of the last hundred years — and quite possibly the greatest philosopher who ever lived. I don’t make such claims lightly, and feel that I have only recently come to truly appreciate how much we need Heidegger. Yet reading Heidegger is extremely difficult. The present essay will help to clarify his thought by putting it into dialogue with the Traditionalists, whose writings are much more accessible, and much more familiar to my readers.

(b) Arrive at a better understanding of Traditionalism. We will find that in important ways Heidegger’s thought is not compatible with Traditionalism. The reason for this is that from a Heideggerian perspective Traditionalism is fundamentally flawed: it is thoroughly (and naïvely) invested in the Western metaphysical tradition which, according to Heidegger, sets the stage for modernity. In other words, because Traditionalism uncritically accepts the validity of Western metaphysical categories, it buys into some of the foundational assumptions of modernity. In the end, Traditionalism has to be judged a thoroughly modern movement, an outgrowth of the very epoch reviled by the Traditionalists themselves. All this, again, becomes clear only if we view Traditionalism, and Western intellectual history, from a Heideggerian perspective. I will argue that that perspective is correct. Thus, part of the purpose of this essay is to convince those on the Right that they need to take a more critical approach to Traditionalism.

(c) Arrive at a new philosophical approach. Although I will argue that Heidegger and Traditionalism are not compatible, the case can nonetheless be made that Heidegger is a traditionalist of sorts, and that, for Heidegger, something like a “primordial tradition” does indeed exist (though it is markedly different from the conceptions of Guénon and Evola). In short, through an engagement with Heidegger’s thought, and how it would respond to Traditionalism, we can arrive at a more adequate traditionalist perspective — one that shares a great many of the values and beliefs of Guénon and Evola, while placing these on a surer philosophical footing. In turn, I will also show that there are limits to Heidegger’s own approach, and that it is flawed in certain ways. Here we achieve a perfect symmetry, for these flaws are perceptible from a traditionalist perspective, broadly speaking. What I will have to say on this latter topic will also be of great interest to anyone influenced by Ásatrú, or the Germanic pagan revivalist movement.

In the end, we will not arrive simply at a fusion of Heidegger and Traditionalism, since both are transformed through the dialogue into which I put them. We will arrive instead at a new philosophical perspective, a new beginning and a new “program” for Western philosophy, one that has rejected Western metaphysics and that seeks to prepare the way for something yet to come, something beyond the modern and the “post-modern.” This new beginning is possible because the groundwork was laid by Heidegger, Guénon, and Evola (to name only three).

The project described above is quite ambitious, and it cannot be carried out in a single essay. Thus, the present text is the first in a series of several projected essays. (The outline of the series is presented as an Appendix, at the end of this essay.) Here, I will limit myself to a basic survey of Heidegger in relation to Traditionalism, his knowledge of Traditionalist writings, and the criticisms he would likely have leveled against this school of thought.

2. Anti-Modernism in Heidegger and the Traditionalists

The primary reason Heidegger gets associated with Guénon and Evola is that all three were trenchant critics of modernity. Heidegger and the Traditionalists hold that modernity is a period of decline, that it is a falling away from an “originary” [2] [5] position that was qualitatively different, and immeasurably superior. Further, the terms in which these authors critique modernity are often remarkably similar.

Consider these lines from Heidegger’s Introduction to Metaphysics, worth quoting at length because they sound like they could have come straight out of Guénon’s The Reign of Quantity and Signs of the Times:

When the farthest corner of the globe has been conquered technologically and can be exploited economically; when any incident you like, at any time you like, becomes accessible as fast as you like; when you can simultaneously “experience” an assassination attempt against a king in France and a symphony concert in Tokyo; when time is nothing but speed, instantaneity, and simultaneity, and time as history has vanished from all Dasein of all peoples; when a boxer counts as the great man of a people; when the tallies of millions at mass meetings are a triumph; then, yes then, there still looms like a specter over all this uproar the question: what for? — where to? — and what then? The spiritual decline of the earth has progressed so far that peoples are in danger of losing their last spiritual strength, the strength that makes it possible even to see the decline [which is meant in relation to the fate of “Being”] and to appraise it as such. This simple observation has nothing to do with cultural pessimism — nor with any optimism either, of course; for the darkening of the world, the flight of the gods, the destruction of the earth, the reduction of human beings to a mass, the hatred and mistrust of everything creative and free has already reached such proportions throughout the whole earth that such childish categories as pessimism and optimism have long become laughable. [3] [6]

In a later passage, Heidegger emphatically reiterates much of this: “We said: on the earth, all over it, a darkening of the world is happening. The essential happenings in this darkening are: the flight of the gods, the destruction of the earth, the reduction of human beings to a mass, the preeminence of the mediocre.” [4] [7] Consider also this passage:

All things sank to the same level, to a surface resembling a blind mirror that no longer mirrors, that casts nothing back. The prevailing dimension became that of extension and number. To be able — this no longer means to spend and to lavish, thanks to lofty overabundance and the mastery of energies; instead, it means only practicing a routine in which anyone can be trained, always combined with a certain amount of sweat and display. In America and Russia, then, this all intensified until it turned into the measureless so-on and so-forth of the ever-identical and the indifferent, until finally this quantitative temper became a quality of its own. By now in those countries the predominance of a cross-section of the indifference is no longer something inconsequential and merely barren but is the onslaught of that which aggressively destroys all rank and all that is world-spiritual, and portrays these as a lie. This is the onslaught of what we call the demonic [in the sense of the destructively evil]. [5] [8]

Finally, let us consider a passage from a later text, What Is Called Thinking? (1953):

The African Sahara is only one kind of wasteland. The devastation of the earth can easily go hand in hand with a guaranteed supreme living standard for man, and just as easily with the organized establishment of a uniform state of happiness for all men. Devastation can be the same as both, and can haunt us everywhere in the most unearthly way — by keeping itself hidden. Devastation does not just mean a slow sinking into the sands. Devastation is the high-velocity expulsion of Mnemosyne. The words, “the wasteland grows,” come from another realm than the current appraisals of our age. Nietzsche said, “the wasteland grows” nearly three quarters of a century ago. And he added, “Woe to him who hides wastelands within.” [6] [9]

These passages give a fairly good summation of the essentials of Heidegger’s critique of modernity, which is worked out in much greater detail in his entire oeuvre. (Arguably, Heidegger’s confrontation with modernity is the central feature of his entire philosophy.) We may note here, especially, four major points. [7] [10] I will set these out below, along with quotations from Guénon’s Reign of Quantity, for comparison:

(a) The predominance of the “quantitative” in modernity; the triumph of the quantitative over the qualitative:

Guénon: “The descending movement of manifestation, and consequently that of the cycle of which it is an expression, takes place away from the positive or essential pole of existence toward its negative or substantial pole, and the result is that all things must progressively take on a decreasingly qualitative and an increasingly quantitative aspect; and that is why the last period of the cycle must show a very special tendency toward the establishment of a ‘reign of quantity.’” [8] [11]

(b) The cancellation of distance in the modern period; the increasing “speed” of modernity:

Guénon: “[Events] are being unfolded nowadays with a speed unexampled in the earlier ages, and this speed goes on increasing and will continue to increase up to the end of the cycle; there is thus something like a progressive ‘contraction’ of duration, the limit of which corresponds to the ‘stopping-point’ previously alluded to; it will be necessary to return to a special consideration of these matters later on, and to explain them more fully.” [9] [12]

And:

“The increase in the speed of events, as the end of the cycle draws near, can be compared to the acceleration that takes place in the fall of heavy bodies: the course of the development of the present humanity closely resembles the movement of a mobile body running down a slope and going faster as it approaches the bottom . . .” [10] [13]

(c) Modernity’s leveling effect; the destruction of an order of rank:

Guénon: “It is no less obvious that differences of aptitude cannot in spite of everything be entirely suppressed, so that a uniform education will not give exactly the same results for all; but it is all too true that, although it cannot confer on anyone qualities that he does not possess, it is on the contrary very well fitted to suppress in everyone all possibilities above the common level; thus the ‘leveling’ always works downward: indeed, it could not work in any other way, being itself only an expression of the tendency toward the lowest, that is, toward pure quantity . . .” [11] [14]

(d) Modernity’s reduction of everything to uniformity:

Guénon: “A mere glance at things as they are is enough to make it clear that the aim is everywhere to reduce everything to uniformity, whether it be human beings themselves or the things among which they live, and it is obvious that such a result can only be obtained by suppressing as far as possible every qualitative distinction . . .” [12] [15]

In later works, Heidegger explicitly ties modernity’s will towards uniformity to the “mechanization” of human beings. The spirit of technology becomes so totalizing that finally human beings themselves are “requisitioned” (to use a Heideggerian expression) and integrated as subsidiary mechanisms within the vast machine of modernity. In this connection, consider this passage from Guénon, worth quoting at length:

Servant of the machine, the man must become a machine himself, and thenceforth his work has nothing really human in it, for it no longer implies the putting to work of any of the qualities that really constitute human nature. The end of all this is what is called in present-day jargon ‘mass-production,’ the purpose of which is only to produce the greatest possible quantity of objects, and of objects as exactly alike as possible, intended for the use of men who are supposed to be no less alike; that is indeed the triumph of quantity, as was pointed out earlier, and it is by the same token the triumph of uniformity. These men who are reduced to mere numerical ‘units’ are expected to live in what can scarcely be called houses, for that would be to misuse the word, but in ‘hives’ of which the compartments will all be planned on the same model, and furnished with objects made by ‘mass-production,’ in such a way as to cause to disappear from the environment in which the people live every qualitative difference. [13] [16]

One last quotation from Guénon: “Man ‘mechanized’ everything and ended at last by mechanizing himself, falling little by little into the condition of numerical units, parodying unity, yet lost in the uniformity and indistinction of the ‘masses,’ that is, in pure multiplicity and nothing else. Surely that is the most complete triumph of quantity over quality that can be imagined.” [14] [17]

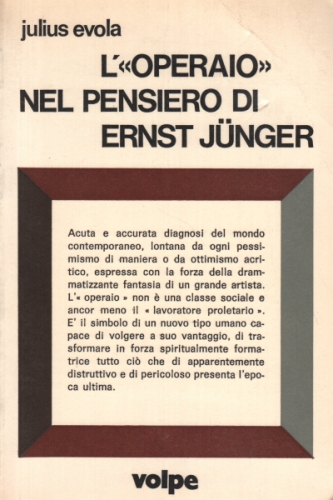

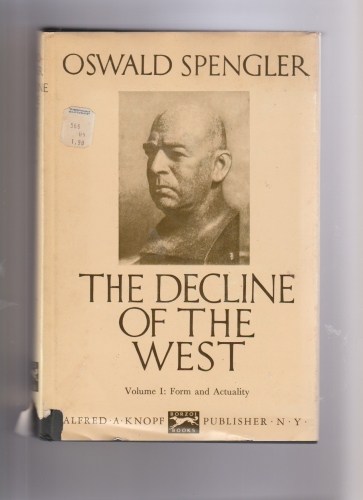

It would be pointless to amass further such quotations from Guénon since his work is replete with them — and since many of my readers are much more familiar with Guénon’s work than with Heidegger’s. It would be equally pointless to quote the many virtually identical observations from Evola (who is probably much more familiar to my readers even than Guénon). A substantial amount of Evola’s work is occupied with elaborating and extending Guénon’s critique of modernity, to which Evola devoted entire volumes (e.g., Revolt Against the Modern World, Ride the Tiger, Men Among the Ruins, etc.). However, their positions diverge when Evola advocates that the superior man respond to modernity by “riding the tiger” (i.e., utilizing certain negative elements of the modern world, which might destroy lesser men, for the positive purpose of self-realization).

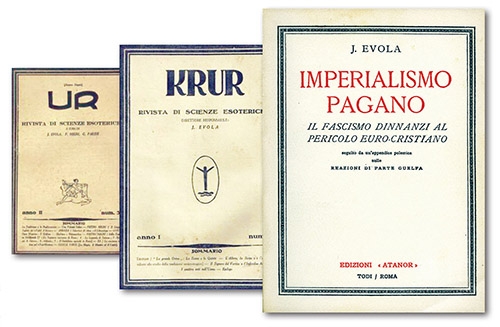

3. The Evola Quotation in Heidegger’s Nachlass

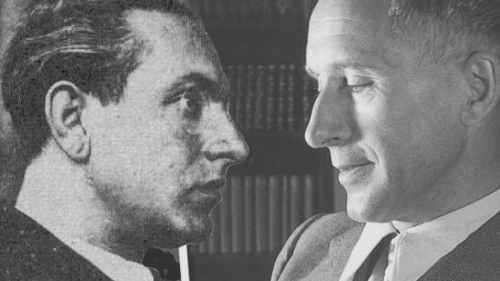

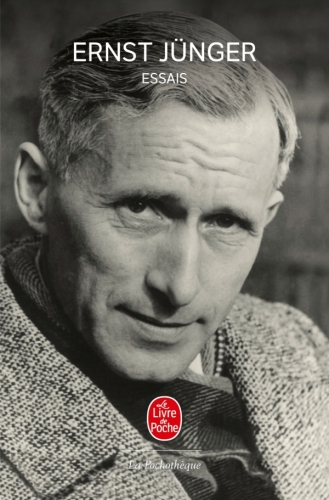

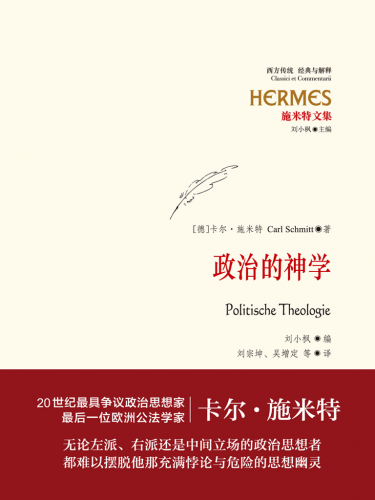

The foregoing has hopefully demonstrated to the reader that Heidegger and Guénon held strikingly similar views on modernity. Although Heidegger knew individuals who respected Guénon (e.g., Carl Schmitt and Ernst Jünger), no evidence has emerged that Heidegger actually read Guénon’s work. Very recently, however, evidence has emerged that Heidegger read Evola. However, far from supporting the idea that Heidegger was influenced by Evola or sympathetic to him, an examination of this evidence will demonstrate exactly where Heidegger parts company with Traditionalism. [15] [20]

Amongst Heidegger’s Nachlass (the papers left behind after his death) a handwritten note has been found in which the philosopher quotes a passage from Friedrich Bauer’s 1935 German translation of Revolt Against the Modern World (Erhebung wider die moderne Welt). Here is the passage as Heidegger copied it out:

Wenn eine Rasse die Berührung mit dem, was allein Beständigkeit hat und geben kann — mit der Welt des Seyns — verloren hat, dann sinken die von ihr gebildeten kollektiven Organismen, welches immer ihre Größe und Macht sei, schicksalhaft in die Welt der Zufälligkeit herab.

And here is a translation:

When a race has lost contact with what alone has and can give it permanence [or “stability,” Beständigkeit] — with the world of Beyng [Seyns] then the collective organisms formed by it, whatever be their greatness and power, are destined to sink down into the world of contingency.

For comparison, here is the entire passage from Bauer’s text:

Wenn eine Rasse die Berührung mit dem, was allein Beständigkeit hat und geben kann — mit der Welt des “Seins” — verloren hat, dann sinken die von ihr gebildeten kollektiven Organismen, welches immer ihre Größe und Macht sei, schicksalhaft in die Welt der Zufälligkeit herab: werden Beute des Irrationalen, des Veränderlichen, des “Geschichtichen,” dessen, was von unten und von außen her bedingt ist. [16] [21]

We immediately notice two things when Heidegger’s handwritten version is compared to the original. First, Heidegger has rendered Sein as Seyn. [17] [22] Second, Heidegger replaces a colon with a period and omits the last part of the sentence entirely. The part after the colon can be translated as follows: “[to] become prey to the irrational, the changeable, the ‘historical,’ of what is conditioned from below and from the outside.” Why did Heidegger make these changes? Fully answering this question will allow us to see that Heidegger actually rejects Evola’s Traditionalism in the most fundamental terms possible.

First of all, it is likely that this undated note comes from sometime in the 1930s. During this time, Heidegger began utilizing Seyn, an archaic German spelling of Sein (Being). [18] [23] But why? What did this signify? It was not simply eccentricity on Heidegger’s part. By Seyn, Heidegger meant something distinct from Sein, which refers to the Being that beings have (“Being as such”). Seyn instead refers to what Heidegger calls elsewhere “the clearing” (die Lichtung). This metaphorical expression refers to a clearing in a forest, which allows light to enter in and illuminate what stands within the clearing. Thomas Sheehan describes Heidegger’s clearing as “the always already opened-up ‘space’ that makes the being of things (phenomenologically: the intelligibility of things) possible and necessary.” [19] [24] The clearing is what “gives” Being.

Heidegger writes in “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking” (1964):

The forest clearing is experienced in contrast to dense forest, called Dickung in our older language. The substantive “opening” [Lichtung] goes back to the verb “open” [lichten]. The adjective licht “open” is the same word as “light.” To open something means: to make something light, free and open, e.g., to make the forest free of trees at one place. The openness thus originating is the clearing. . . . Light can stream into the clearing, into its openness, and let brightness play with darkness in it. But light never first creates openness. Rather, light presupposes openness. However, the clearing, the opening, is not only free for brightness and darkness, but also for resonance and echo, for sounding and the diminishing of sound. The clearing is the open region for everything that becomes present and absent. . . . What the word [opening] designates in the connection we are now thinking, free openness, is a “primal phenomenon” [Urphänomenon], to use a word of Goethe’s. [20] [25]

Consider a simple example. I approach an unfamiliar object sitting on my doorstep. I cannot place it; try as I might it remains a mystery. But as I approach closer still, all is revealed: I see now that it is an Amazon box. In this moment, what has occurred is that the Being of the object — what it is, what its meaning is — becomes present to me. [21] [26] In order for this to be possible at all, I must bear within me a certain special sort of “openness,” within which the Being of something makes itself known or makes itself present. [22] [27]

Contrary to how empiricists tend to conceive things, I don’t actually experience myself as hanging a label onto the object or slotting it within a mental category. This is an analysis after the fact of experience, not what I actually experience. If we are truer to the phenomenon than the empiricists (i.e., if we are good phenomenologists) we have to report that the experience is actually one in which the Being of the thing seems to “come forth,” or to display itself as we explore the object. But, again, this is only possible because of the “openness” referred to earlier. In this openness, Being displays itself; it is “lit up” within the space of the metaphorical “clearing.”

Thus, for Heidegger it is possible to speak of something deeper or more ultimate than Being itself (hence, an Urphänomenon): that which allows our encounter with the Being of beings in the first place; the open clearing. When Heidegger famously refers to “the forgottenness of Being” (Vergessenheit des Seins) he is actually referring to the forgottenness of the clearing. [23] [28] The clearing is forgotten in the sense that we have forgotten that in virtue of which Being is given to us. As I will discuss later, Heidegger holds that the Western metaphysical tradition, beginning with the Pre-Socratics, systematically forgets the clearing, and he traces all of our modern ills to this forgetting. He writes: “In fact, the history of Western thought begins, not by thinking what is most thought-provoking, but by letting it remain forgotten.” [24] [29]

Now, by contrast, when Evola speaks of “the world of being” (Welt des Seins; mondo di essere) in this passage and elsewhere, he is referring to a Platonic realm of timeless essences that are the true beings, in contrast to the changeful, impermanent terrestrial beings we encounter with the five senses. Traditionalism is heavily dependent on this Platonic metaphysics. Consider, for example, Evola’s words from the very beginning of Revolt:

In order to understand both the spirit of Tradition and its antithesis, modern civilization, it is necessary to begin with the fundamental doctrine of the two natures. According to this doctrine there is a physical order of things and a metaphysical one; there is a mortal nature and an immortal one; there is the superior realm of “being” and the inferior realm of “becoming.” Generally speaking, there is a visible and tangible dimension and, prior to and beyond it, an invisible and intangible dimension that is the support, the source, and the true life of the former. [25] [30]

Not only does Heidegger reject this Platonic metaphysics, he sees it as the first major stage in the decline of the West. Its inception is essentially identical with the “forgottenness” of the clearing spoken of a moment ago. All the aspects of modernity Heidegger was quoted earlier as deploring are ultimately traceable, he believes, to Platonic metaphysics. Thus, Heidegger completely rejects the idea that a “race” declines when it has “lost contact” with being, in the Platonic sense of “being” meant by Evola. Quite the reverse: a race — our race — has declined precisely through its turn toward Platonic metaphysics, and its turn away from the clearing. Thus, when Heidegger swaps Sein for Seyn, he is entirely changing the meaning of what Evola is saying. He is rewriting the passage so that it agrees with his own position: the decline of the West stems from its forgottenness of Seyn (the clearing) and its embrace of the Platonic Sein of the Western metaphysical tradition.

Heidegger omits the last part of Evola’s sentence for similar reasons. Let us look again at those words. Evola tells us that when a race has lost contact with “the world of being” it will “become prey to the irrational, the changeable, the ‘historical,’ of what is conditioned from below and from the outside.” Heidegger omits these words because he rejects Evola’s dichotomy between “being” and “the historical.” Heidegger argues, in fact, that Beyng/the clearing is inherently historical (geschichtlich), and changeable (veränderlich). The Being of things actually changes as culture changes. This is the same thing, fundamentally, as saying that the meaning of things changes over time.

But could the Being/meaning of the Amazon box on my doorstep ever change? Of course. Imagine a future world without Amazon, or one in which Amazon has been declared a monopoly and broken up into a number of different, competing entities. No more Amazon boxes on doorsteps. When you do see them, you see them in museums and you no longer see them simply as utilitarian objects. You no longer think, on glimpsing one, “Oh, my copy of Being and Time has arrived,” or some such. Instead, the Amazon box takes on a new meaning: as a symbol of a dark time we are, happily, well beyond; a time in which we allowed companies like Amazon not only to corner the market and put all smaller competitors out of business, but to shape the information we have access to through censorship and the banning of books [31].

Thus, if the Being or meaning that things have for us changes over the course of history, as culture and circumstances change, then, contra Evola, Being is inescapably “changeable” and “historical.” Evola also says that a race which loses contact with his idea of being falls prey to “the irrational” (das Irrational, in the German translation). Would Heidegger endorse this as well? Is his idea of Being “irrational”? Well, Heidegger does argue that historical-cultural shifts in Being/meaning are not fully intelligible to human beings. The reason for this is that it is always within Beyng/the clearing that things are meaningful or intelligible to us. It therefore follows that Beyng/the clearing itself is not ultimately intelligible. In a highly qualified sense, we could thus describe it as “irrational.” That Evola implicitly endorses the equation of being with “the rational” in this passage is extremely ironic. As we will see in a later installment, Heidegger argues that this equation is a key feature of the modern inflection of the Western metaphysical tradition, and that all the modern maladies Evola decries are ultimately attributable to it.

Heidegger would have regarded Guénon and Evola as philosophically naïve—for several reasons. First, they uncritically appropriate the Western metaphysical tradition in the name of combating modernity. Yet, as I have already mentioned, Heidegger argues that that tradition is implicated in the decline of the West. Second, the Traditionalists naïvely assert that this metaphysical tradition is “perennial” or timeless. They take Platonism as preserving elements of a primordial tradition that antedates Plato by millennia. They hold that the time of Plato belongs to the Kali Yuga (the fourth age, the decadent “Iron Age”), but they take Plato (and other ancient philosophers) to be preserving an older, indeed timeless wisdom. However, this is pure speculation, for which there is no solid scholarly evidence. [26] [32]

Heidegger would have regarded Guénon and Evola as philosophically naïve—for several reasons. First, they uncritically appropriate the Western metaphysical tradition in the name of combating modernity. Yet, as I have already mentioned, Heidegger argues that that tradition is implicated in the decline of the West. Second, the Traditionalists naïvely assert that this metaphysical tradition is “perennial” or timeless. They take Platonism as preserving elements of a primordial tradition that antedates Plato by millennia. They hold that the time of Plato belongs to the Kali Yuga (the fourth age, the decadent “Iron Age”), but they take Plato (and other ancient philosophers) to be preserving an older, indeed timeless wisdom. However, this is pure speculation, for which there is no solid scholarly evidence. [26] [32]

A further Heideggerian objection to Traditionalism may be considered at this point, and it is an extremely serious one. Both Heidegger and the Traditionalists decry rootless modern individualism. However, Heidegger’s critique goes much further. Recall that for the philosopher Being is inherently historical and changeable. What things are for us, or what they mean, is determined in part by our historical situation. Human Dasein is always embedded in a set of concrete historical, cultural circumstances. Heidegger writes: “Only insofar as the human being exists in a definite history are beings given, is truth given. There is no truth given in itself; rather, truth is decision and fate for human beings; it is something human.” [27] [33] This does not, however, mean that truth, as human, is something “subjective”:

We are not humanizing the essence of truth: to the contrary, we are determining the essence of human beings on the basis of truth. Man is transposed into the various gradations of truth. Truth is not above or in man, but man is in truth. Man is in truth inasmuch as truth is this happening of the unconcealment of things on the basis of creative projection. Each individual does not consciously carry out this creative projection; instead, he is already born into a community; he already grows up within a quite definite truth, which he confronts to a greater or lesser degree. Man is the one whose history displays the happening of truth. [28] [34]

As a result of this stance, Heidegger rejects both the Enlightenment ideal of a “view from nowhere,” as well as rootless, modern cosmopolitanism.

Consider, however, the following lines from The Reign of Quantity. Guénon writes disapprovingly of “those among the moderns who consider themselves to be outside all religion” — i.e., freethinking individualists. He asserts that such men are “at the extreme opposite point from those who, having penetrated to the principial unity of all the traditions, are no longer tied to any particular form.” This latter position, of course, is that of Guénonian Traditionalism itself. In a footnote, he then approvingly quotes Ibn ‘Arabî: “My heart has become capable of all forms: it is a pasture for gazelles and a monastery for Christian monks, and a temple for idols, and the Kaabah of the pilgrim, and the table of the Thorah and the book of the Quran. I am the religion of Love, whatever road his camels may take; my religion and my faith are the true religion.” [29] [35]

Though Guénon contrasts the position of the modern freethinker to the Traditionalist, Heidegger would doubtless argue that there is a fundamental identity between them. The freethinker imagines that he has freed himself from any cultural-religious context and become a kind of intellectual or spiritual cosmopolitan. Yet the Traditionalist thinks the exact same thing. The only difference is that the freethinker believes he has cast off religion or “spirituality” itself, whereas the Traditionalist imagines that he adheres to a decontextualized, ahistorical, and universal spiritual construct called “Tradition.” This standpoint too is fundamentally modern.

One might object, however, that Guénon’s decision to convert to Islam and “go native” in Cairo, where he spent the last twenty years of his life, indicates that he was aware that tradition could not be a free-floating abstraction, and that to be a true Traditionalist one had to choose a living tradition and immerse oneself in it. This is true, as a statement of Guénon’s views. But the very idea that one can choose a tradition buys into the modern conception of the autonomous self who may, from a standpoint of detachment from any cultural or historical context, survey the different traditions and select one. It is no use here to point out that all Muslims must, in a sense, “choose” Islam, as it is not an ethnic religion but a creedal one, whose faith all adherents must profess, and to which anyone may convert. This is a valid point, but a superficial one. Islam emerged from a cultural and historical context quite alien to the West, and which no Westerner may ever truly enter.

4. Conclusion

Let us now consider a couple of objections to this Heideggerian critique of Traditionalism.

First, defenders of Traditionalism might respond that Guénon and Evola are primarily grounded in the Indian tradition, and not in Western metaphysics at all. There are essentially two pieces of evidence for this claim. The first is Guénon and Evola’s endorsement of the Hindu cyclical account of time, of the yugas, which is indeed quite ancient. Both seem to accept this teaching in very literal terms, right down to the traditional Hindu calculations of the time span of each yuga (which strike most modern readers as arbitrary inventions). Second is the primacy granted by both thinkers to Vedanta. Both Guénon and Evola regard the teachings of the Upanishads as an expression of a very ancient ur-metaphysics, which constitutes a “perennial philosophy.”

The dependence of the Traditionalists on the Indian tradition is very real. The trouble, however, is that they interpret the Indian materials in terms of the categories and terminology of Western metaphysics. Indeed, this is especially true of Guénon, who shows no signs of recognizing that there is anything problematic about understanding the Upanishads in terms derived from Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy. For example, right at the beginning of The Reign of Quantity, Guénon discusses the duality of Purusha and Prakriti using the categories of “essence and substance” — then, a page later, he appeals to “form and matter,” then to “act and potency.” [30] [38] This is all Aristotelian terminology. Moreover, there is no attempt on Guénon’s part to recover the “originary” sense of these terms in Aristotle. Instead, he unhesitatingly adopts the medieval scholastic understanding of these distinctions.

It may be that Guénon thought it was valid to discuss Vedanta in Platonic-Aristotelian terms because he regarded the Platonic tradition as itself an expression of the perennial philosophy. Thus, he simply decided a priori that Vedanta and Platonism are two streams flowing from the same source: primordial Tradition. But, again, this is pure speculation. The bottom line is that Guénon and Evola do accord special primacy to the Indian tradition over Western metaphysics — but they see the former almost entirely through the lens of the latter. Thus, despite their interest in Indian thought, they are still thoroughly beholden to Western metaphysics.

It remains to consider a further, much more significant, objection to these Heideggerian critiques of Traditionalism. The primary objection I have raised against Guénon and Evola is that they are thoroughly committed to Western metaphysics. This is a problem because Heidegger argues that the Western tradition is not only a falling away from a more primordial encounter with Being, it actually makes possible the modern decadence that Traditionalists rightly reject. But why we should follow Heidegger in any of this? Why should we accept Heidegger’s negative evaluation of Western metaphysics? Why should we accept the thesis that Platonic metaphysics made modernity possible? The next essay in this series will be devoted to addressing just these questions. It will be the first of several essays offering a compressed summary and commentary on Heidegger’s history and critique of metaphysics, demonstrating that the claims he makes are both plausible and profound. Heidegger is right in thinking that Western metaphysics lies at the root of modernity. We will begin with Heidegger’s critique of Plato.

What did Heidegger have to say about tradition? In “The Age of the World Picture” (1938) He warns us against “merely negating the age” and writes that “The flight into tradition, out of a combination of humility and presumption, achieves, in itself, nothing, is merely a closing the eyes and blindness towards the historical moment.” [31] [39] But Heidegger also argues that the turn toward metaphysics is a turn away from a more authentic way of encountering Being. It is in this latter conception that we find what may be the equivalent of “primordial tradition” in Heidegger’s thought. One of the conclusions that will be defended in this series of essays is that while Heidegger is clearly not a Guénonian or Evolian Traditionalist, he is actually more traditionalist than the Traditionalists.

Appendix. Outline of the Series:

Part One (the present essay): Why Heidegger and Traditionalism are not compatible; major errors in Traditionalism from a Heideggerian perspective.

Part Two: Heidegger’s history of metaphysics, focusing on his critique of Platonism. This account will deepen our understanding of why Heidegger would regard Traditionalism as a fundamentally modern movement, as well as deepen our understanding of modernity.

Part Three: The continuation of our account of Heidegger’s history of metaphysics, from Plato to Nietzsche. Among other things, Part Three will discuss Evola’s problematic indebtedness to German Idealism, especially J. G. Fichte, whose philosophy (I will argue) is like a vial of fast-acting, concentrated modern poison.

Part Four: From Nietzsche to the present age of post-War modernity, which Heidegger characterizes as das Gestell (“enframing”). Part Four will deal in detail with this fundamental Heideggerian concept, which is central to his critique of technology.

Part Five: How Heidegger proposes that we respond to technological modernity. His project of a “recovery” of a pre-metaphysical standpoint; his “preparation” for the next “dispensation of Beyng.” His phenomenology of authentic human “dwelling” (“the fourfold”), and Gelassenheit.

Part Six: A call for a new philosophical approach, building upon Heidegger and the Traditionalists, while moving beyond them. Three primary components: (1) The recovery of “poetic wisdom” (to borrow a term from G. B. Vico): Heidegger’s project of the recovery of the pre-metaphysical standpoint now applied to myth and folklore, and expanded to include non-Greek sources (e.g., the pre-Christian traditions of Northern Europe); (2) Expanding Heidegger’s project of the “destruction” of the Western tradition to include the Gnostic and Hermetic traditions, Western esotericism, and Western mysticism; (3) Finally, social and cultural criticism from a standpoint informed by the critique of metaphysics, critique of modernity, and recovery of “poetic wisdom.”

Notes

[1] [40] I will capitalize the “t” in Traditionalism to indicate the school of Guénon, Evola, et al., as opposed to “traditionalism” in the looser, broader sense of the term. This device is necessary, as I will be using the term in both senses. I should also note that it is primarily the Traditionalism of Guénon and Evola that I am concerned with here. I am comparatively less interested in the “softer” Traditionalism of figures like Coomaraswamy, Schuon, Huston Smith, etc. Most of the objections raised against Guénon and Evola herein would apply to these authors as well.

[2] [41] “Originary” (ursprünglich) is a term frequently used by Heidegger.

[3] [42] Martin Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, trans. Gregory Fried and Richard Polt (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 40-41. This was originally a lecture course given by Heidegger in 1935. It was published for the first time in German in 1953. The material in square brackets was added by Heidegger when the lecture course was published in 1953.

[4] [43] Fried and Polt, 47.

[5] [44] Fried and Polt, 48-49. Bracketed phrase added by Heidegger for the 1953 edition.

[6] [45] Martin Heidegger, What is Called Thinking?, trans. J. Glenn Gray (New York: Harper Perennial, 1968), 30.

[7] [46] One point is omitted from the discussion below, one which my readers might expect me to discuss: “the flight of the gods.” What Heidegger means by this, however, is complicated, and far from obvious. I will discuss this issue in a later essay.

[8] [47] René Guénon, The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, trans. Lord Northbourne (Hillsdale, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2001), 43.

[9] [48] Reign, 42

[10] [49] Reign, 43. For similar remarks see Julius Evola, Meditations on the Peaks, trans. Guido Stucco (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1998), 45-46.

[11] [50] Reign, 51-52.

[12] [51] Reign, 48.

[13] [52] Reign, pp. 60-61. Compare this to some remarks by Alexandre Kojève: “Hence it would have to be admitted that after the end of history men would construct their edifices and works of art as birds build their nests and spiders spin their webs, would perform their musical concerts after the fashion of frogs and cicadas, would play like young animals and would indulge in love like adult beasts.” See Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, ed. Raymond Queneau and Allan Bloom, trans. James H. Nichols, Jr. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1969), 159 (footnote).

[14] [53] Reign p. 194.

[15] [54] The discovery of the note in 2015 received some attention in the German press. Writing in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung [55], Thomas Vasek claims that “textual comparisons suggest that Heidegger had not only read Evola, as this note indicates, but was also influenced by his ideas from the mid-thirties on, from his critique of science and technology, his anti-humanism and rejection of Christianity, to his ‘spiritual’ racism.” This is a completely baseless, and, indeed, ludicrous assertion, as I will shortly demonstrate. See Greg Johnson’s analysis of the Heidegger note, and Vasek’s article, here [56].

[16] [57] Julius Evola, Erhebung wider die moderne Welt, trans. Friedrich Bauer (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1935), 65. The translator actually leaves out portions of Evola’s text, but since Heidegger only read the translation and not the original, these omissions do not concern us here. For the full passage in English translation, see Julius Evola, Revolt Against the Modern World, trans. Guido Stucco (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 1995), 56-57.

[17] [58] The “s” at the end of Seins/Seyns in the passage simply indicates the genitive case. The nominative is Sein/Seyn.

[18] [59] Anglophone translators of Heidegger have adopted the convention of rendering Seyn as “Beying.”

[19] [60] Thomas Sheehan, Making Sense of Heidegger: A Paradigm Shift (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015), 20.

[20] [61] Martin Heidegger, Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), 384-385. This essay was translated by Joan Stambaugh; italics added.

[21] [62] Sheehan argues at length that, for Heidegger, Being and meaning are identical.

[22] [63] This way of expressing things should be understood as figurative, and preliminary. Actually, Heidegger wants to entirely avoid a “subjective” treatment of the clearing as some sort of “faculty” or Kantian a priori structure that I “bear within me.” The reason, at root, is that this treatment of the clearing is phenomenologically untrue. I do not, in fact, experience the clearing as something “in me” that is “mine.” Still less do I experience it as something over which I have any kind of influence or control. There is thus no real basis for “subjectivizing” the clearing; for locating it “within the subject.” Indeed, Heidegger critiques the subject/object distinction prevailing in philosophy since Descartes, which locates certain “properties” as “within” a subject, as if this subject is a kind of cabinet in which we dwell, removed from an “external world.” See Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. Joan Stambaugh, rev. Dennis J. Schmidt (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2010), 60-61.

[23] [64] Generally speaking, this is correct. Unfortunately, Heidegger is inconsistent with his use of Sein/Seyn, sometimes referring to Being, sometimes to the clearing that gives Being.

[24] [65] What is Called Thinking?, 152.

[25] [66] Revolt, 3.

[26] [67] The Traditionalists are in much the same position as the Renaissance “Hermeticists” who falsely believed that the Corpus Hermeticum contained an Egyptian wisdom that far antedated Plato and the Greeks, and from whom those philosophers had taken their basic doctrines. In reality, the Corpus Hermeticum was no older than the first century BC, and it derived its doctrines, in large measure, from Plato and his school.

[27] [68] Martin Heidegger, Being and Truth, trans. Gregory Fried and Richard Polt (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 210), 134. Italics in original.

[28] [69] Being and Truth, 136. Italics in original.

[29] [70] Reign, 62-63.

[30] [71] Reign, 11-12.

[31] [72] Martin Heidegger, Off the Beaten Track, trans. Julian Young and Kenneth Haynes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 72.

L’empereur reçoit pour dix ans la souveraineté sur Jérusalem, Bethléem et la Haute-Galilée, où se niche, à flanc de colline, la ville de Nazareth, tandis que les mahométans gardent, dans la ville sainte, le contrôle de la mosquée al-Aqsa et le Mont Moriah (soit le quartier du Temple). Cet accord jette le pape dans une fureur prodigieuse : les dévots de Mahomet n’ont pas été étrillés en bataille rangée et une partie de Jérusalem leur est laissée, notamment celle qui intéresse au plus haut point les Chevaliers du Temple, respectueusement soumis au pontife. Le 14 mars 1229, Frédéric fait son entrée solennelle à Jérusalem, où il est sacré roi le 16, en l’église du Saint-Sépulcre, boudé, sur ordre du pape, par le patriarche latin et les chevaliers des Ordres militaires.

L’empereur reçoit pour dix ans la souveraineté sur Jérusalem, Bethléem et la Haute-Galilée, où se niche, à flanc de colline, la ville de Nazareth, tandis que les mahométans gardent, dans la ville sainte, le contrôle de la mosquée al-Aqsa et le Mont Moriah (soit le quartier du Temple). Cet accord jette le pape dans une fureur prodigieuse : les dévots de Mahomet n’ont pas été étrillés en bataille rangée et une partie de Jérusalem leur est laissée, notamment celle qui intéresse au plus haut point les Chevaliers du Temple, respectueusement soumis au pontife. Le 14 mars 1229, Frédéric fait son entrée solennelle à Jérusalem, où il est sacré roi le 16, en l’église du Saint-Sépulcre, boudé, sur ordre du pape, par le patriarche latin et les chevaliers des Ordres militaires.

« Il y a cinquante ans, dans ma chère Allemagne, j’étais, moi, plus à mon aise, mes prédécesseurs ne m’embarrassaient pas ; ils n’étaient pas en état de m’imposer longtemps et de m’arrêter. J’abandonnai donc bien vite la littérature allemande, je ne l’étudiai plus et je m’adonnai tout entier à la vie elle-même, et à la création. Je me développai ainsi peu à peu tout naturellement et me rendis capable des œuvres que je publiais de temps en temps avec succès. Dans ce progrès parallèle de ma vie et de mon développement, jamais mon idée de la perfection n’a été supérieure à ce que j’étais à ce moment-là capable de réaliser. »

« Il y a cinquante ans, dans ma chère Allemagne, j’étais, moi, plus à mon aise, mes prédécesseurs ne m’embarrassaient pas ; ils n’étaient pas en état de m’imposer longtemps et de m’arrêter. J’abandonnai donc bien vite la littérature allemande, je ne l’étudiai plus et je m’adonnai tout entier à la vie elle-même, et à la création. Je me développai ainsi peu à peu tout naturellement et me rendis capable des œuvres que je publiais de temps en temps avec succès. Dans ce progrès parallèle de ma vie et de mon développement, jamais mon idée de la perfection n’a été supérieure à ce que j’étais à ce moment-là capable de réaliser. »

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

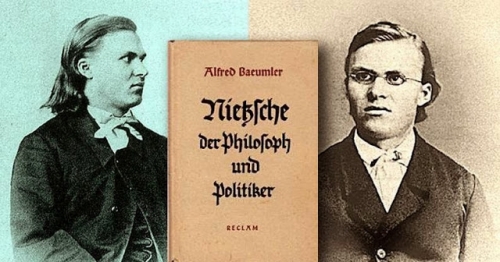

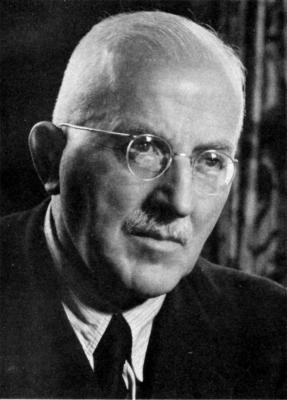

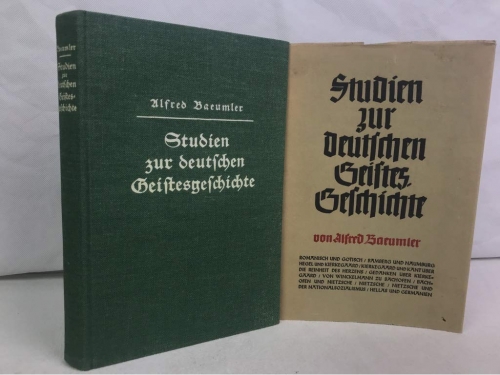

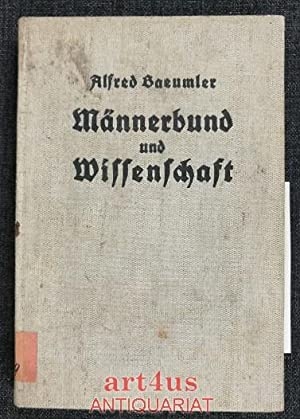

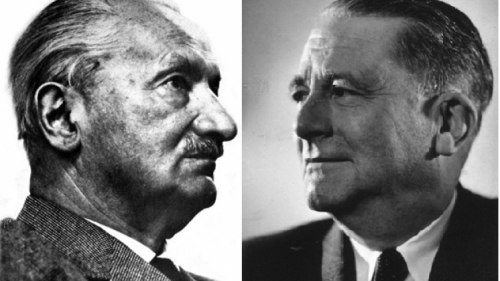

Alfred Baeumler a été le premier philosophe allemand à donner à Nietzsche une interprétation politique. Avant Jaspers et Heidegger, qui ont été influencés par lui, il a vu dans l'Allemagne "hellénique" envisagée par Nietzsche la représentation héroïque d'une révolution des valeurs primordiales incarnées dans la Grèce archaïque, dont le pivot philosophique et idéologique a été perçu dans le texte controversé de Nietzsche sur la volonté de puissance. Non systématique dans la forme, mais très cohérent sur le fond.

Alfred Baeumler a été le premier philosophe allemand à donner à Nietzsche une interprétation politique. Avant Jaspers et Heidegger, qui ont été influencés par lui, il a vu dans l'Allemagne "hellénique" envisagée par Nietzsche la représentation héroïque d'une révolution des valeurs primordiales incarnées dans la Grèce archaïque, dont le pivot philosophique et idéologique a été perçu dans le texte controversé de Nietzsche sur la volonté de puissance. Non systématique dans la forme, mais très cohérent sur le fond.

La publication des écrits de Baeumler - due à la seule maison d'édition italienne qui s'intéresse méthodiquement au philosophe allemand, délibérément occulté à cause des blocages mentaux persistants - s'inscrit dans l'effort culturel pour mettre fin, autant que possible, à l’époque des falsifications dogmatiques. Un document décisif qui va dans le même sens est, entre autres, le travail récent de Domenico Losurdo sur Nietzsche en tant que rebelle aristocratique. Publier Baeumler - comme l'ont fait les Edizioni di Ar avec les précédentes Estetica. e Nietzsche filosofo e politico (= Esthétiques et Nietzsche, philosophe et homme politique) - c'est laisser des traces visibles de cette contre-pensée intimement ancrée dans l'âme européenne et articulée sur la dénonciation du modernisme progressif comme masque du chaos final. Une telle démarche, aujourd'hui, est tout simplement ignorée, faute de moyens intellectuels, ou est pliée aux besoins du pouvoir censurant, ou est reléguée au placard où sont exilées les voix de la dissonance. Ce qui, dans la logique de la pensée unique, signifie condamnation et diffamation.

La publication des écrits de Baeumler - due à la seule maison d'édition italienne qui s'intéresse méthodiquement au philosophe allemand, délibérément occulté à cause des blocages mentaux persistants - s'inscrit dans l'effort culturel pour mettre fin, autant que possible, à l’époque des falsifications dogmatiques. Un document décisif qui va dans le même sens est, entre autres, le travail récent de Domenico Losurdo sur Nietzsche en tant que rebelle aristocratique. Publier Baeumler - comme l'ont fait les Edizioni di Ar avec les précédentes Estetica. e Nietzsche filosofo e politico (= Esthétiques et Nietzsche, philosophe et homme politique) - c'est laisser des traces visibles de cette contre-pensée intimement ancrée dans l'âme européenne et articulée sur la dénonciation du modernisme progressif comme masque du chaos final. Une telle démarche, aujourd'hui, est tout simplement ignorée, faute de moyens intellectuels, ou est pliée aux besoins du pouvoir censurant, ou est reléguée au placard où sont exilées les voix de la dissonance. Ce qui, dans la logique de la pensée unique, signifie condamnation et diffamation.

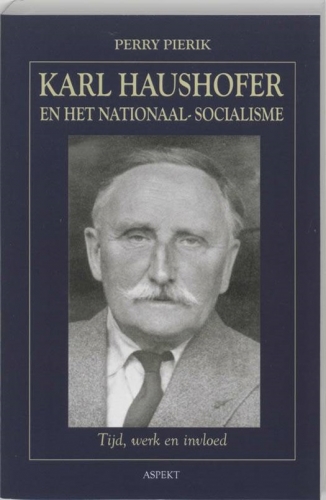

Nu, los daarvan, dit Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme is een redelijk sterk boek. Ook voor wie meer wil weten over geopolitiek, want Pierik gaat uitgebreid op het vakgebied in in het derde hoofdstuk Geopolitik: de mores van het vak. De ideeën van Friedrich Ratzel, Rudolf Kjellén, Halford Mackinder en uiteraard Karl Haushofer en de andere geopoliticus in de familie, zijn zoon Albrecht passeren, samen met die van een aantal mindere goden, uitgeverijen, begunstigers, enzovoort, de revue. Bovendien zijn in het boek 35 bladzijden aan voetnoten opgenomen en 20 bladzijden aan literatuurregister. Daarin zit héél veel over de geopolitiek, zodat wie zich verder wil verdiepen in die wetenschap zich nog lang niet zal gaan vervelen.

Nu, los daarvan, dit Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme is een redelijk sterk boek. Ook voor wie meer wil weten over geopolitiek, want Pierik gaat uitgebreid op het vakgebied in in het derde hoofdstuk Geopolitik: de mores van het vak. De ideeën van Friedrich Ratzel, Rudolf Kjellén, Halford Mackinder en uiteraard Karl Haushofer en de andere geopoliticus in de familie, zijn zoon Albrecht passeren, samen met die van een aantal mindere goden, uitgeverijen, begunstigers, enzovoort, de revue. Bovendien zijn in het boek 35 bladzijden aan voetnoten opgenomen en 20 bladzijden aan literatuurregister. Daarin zit héél veel over de geopolitiek, zodat wie zich verder wil verdiepen in die wetenschap zich nog lang niet zal gaan vervelen. Is het dan eigenlijk wel een wetenschap, kan je je afvragen? En, weerom mijn mening, dat is het en dat is het niet. Is filosofie een wetenschap? Is psychologie een wetenschap? Is economie een wetenschap? Die eerste twee vragen zullen veel mensen meteen met een “nee” beantwoorden, al zullen de beoefenaars van de wetenschap in kwestie daar wellicht een andere mening over hebben, maar economie wordt algemeen gezien als wetenschap. Ik, als economist, zeg dat het dat niet is. Op basis van de economische “wetenschap” zijn systemen gevestigd die zo ver uiteenlopen als communisme en kapitalisme, verdedigt de ene een “miljardairstaks” en de andere een “flat tax”, is de ene in crisistijden voor zware overheidsinvesteringen terwijl de andere pleit voor het buiten de economie blijven van de staat. En elke politicus én elke economist heeft “wetenschappelijke” bewijzen die zijn gelijk staven. En stuk voor stuk zijn ze van oordeel dat hun tegenstanders onwetenschappelijke klungelaars zijn. Of ze negeren die tegenstanders volkomen. Ergo: als we economie als een wetenschap beschouwen, kunnen we geopolitiek óók als een wetenschap beschouwen.

Is het dan eigenlijk wel een wetenschap, kan je je afvragen? En, weerom mijn mening, dat is het en dat is het niet. Is filosofie een wetenschap? Is psychologie een wetenschap? Is economie een wetenschap? Die eerste twee vragen zullen veel mensen meteen met een “nee” beantwoorden, al zullen de beoefenaars van de wetenschap in kwestie daar wellicht een andere mening over hebben, maar economie wordt algemeen gezien als wetenschap. Ik, als economist, zeg dat het dat niet is. Op basis van de economische “wetenschap” zijn systemen gevestigd die zo ver uiteenlopen als communisme en kapitalisme, verdedigt de ene een “miljardairstaks” en de andere een “flat tax”, is de ene in crisistijden voor zware overheidsinvesteringen terwijl de andere pleit voor het buiten de economie blijven van de staat. En elke politicus én elke economist heeft “wetenschappelijke” bewijzen die zijn gelijk staven. En stuk voor stuk zijn ze van oordeel dat hun tegenstanders onwetenschappelijke klungelaars zijn. Of ze negeren die tegenstanders volkomen. Ergo: als we economie als een wetenschap beschouwen, kunnen we geopolitiek óók als een wetenschap beschouwen. Nu, ook los van de rol van Karl Haushofer in de geopolitiek – een rol die eigenlijk nauwelijks kan overschat worden – is dit een interessant boek. De naam van Haushofer zal namelijk zelden genoemd worden zonder ook die van Rudolf Hess te noemen. Rudolf Hess, de gevangene en gehangene van Spandau, de plaatsvervanger van Adolf Hitler, de man met een vredesmissie, is ondanks alle literatuur die over hem gepleegd is nog steeds een van de enigma’s van de twintigste eeuw (daar kom ik bij een latere boekbespreking nog op terug). En hij was jaren een leerling en vriend van Karl Haushofer en diens zoon Albrecht. Hij had hun naamkaartje op zak toen hij naar Schotland vloog. De Haushofers wisten (de zoon in verschillende hoedanigheden) naar alle waarschijnlijkheid van zijn plannen. Al die zaken komen aan bod in Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme – Tijd, werk en invloed, wat toch veel meer is dan wat Wikipedia ter zake vermeldt. Dat spreekt namelijk alleen van Hess die Haushofers ideeën zou geïntroduceerd hebben bij Hitler en van Hess die Haushofers “joodse familie” (Haushofers vrouw was joods) beschermde tegen diezelfde Hitler, maar vertikt het het ook maar met een woord te hebben over de invloed die de Haushofers (zowel Karl als Albrecht) gehad hebben op zijn “vlucht”.

Nu, ook los van de rol van Karl Haushofer in de geopolitiek – een rol die eigenlijk nauwelijks kan overschat worden – is dit een interessant boek. De naam van Haushofer zal namelijk zelden genoemd worden zonder ook die van Rudolf Hess te noemen. Rudolf Hess, de gevangene en gehangene van Spandau, de plaatsvervanger van Adolf Hitler, de man met een vredesmissie, is ondanks alle literatuur die over hem gepleegd is nog steeds een van de enigma’s van de twintigste eeuw (daar kom ik bij een latere boekbespreking nog op terug). En hij was jaren een leerling en vriend van Karl Haushofer en diens zoon Albrecht. Hij had hun naamkaartje op zak toen hij naar Schotland vloog. De Haushofers wisten (de zoon in verschillende hoedanigheden) naar alle waarschijnlijkheid van zijn plannen. Al die zaken komen aan bod in Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme – Tijd, werk en invloed, wat toch veel meer is dan wat Wikipedia ter zake vermeldt. Dat spreekt namelijk alleen van Hess die Haushofers ideeën zou geïntroduceerd hebben bij Hitler en van Hess die Haushofers “joodse familie” (Haushofers vrouw was joods) beschermde tegen diezelfde Hitler, maar vertikt het het ook maar met een woord te hebben over de invloed die de Haushofers (zowel Karl als Albrecht) gehad hebben op zijn “vlucht”.

Ces différences favorisent des lectures non point opposées, ni exclusives l'une de l'autre, mais complémentaires. A l'exception du Travailleur, livre qui définit de façon presque didactique l'émergence d'un Type, Jünger demeure fidèle à ce cheminement que l'on peut définir, avec une grande prudence, comme « romantique » et dont la caractéristique dominante n'est certes point l'effusion sentimentale mais la nature déambulatoire, le goût des sentes forestières, ces « chemins qui ne mènent nulle part » qu'affectionnait Heidegger, à la suite d'Heinrich von Ofterdingen et du « voyageur » de Gènes, de Venise et d'Engadine, toujours accompagné d'une « ombre » qui n'est point celle du désespoir, ni du doute, mais sans doute l'ombre de la Mesure qui suit la marche de ces hommes qui vont vers le soleil sans craindre la démesure.

Ces différences favorisent des lectures non point opposées, ni exclusives l'une de l'autre, mais complémentaires. A l'exception du Travailleur, livre qui définit de façon presque didactique l'émergence d'un Type, Jünger demeure fidèle à ce cheminement que l'on peut définir, avec une grande prudence, comme « romantique » et dont la caractéristique dominante n'est certes point l'effusion sentimentale mais la nature déambulatoire, le goût des sentes forestières, ces « chemins qui ne mènent nulle part » qu'affectionnait Heidegger, à la suite d'Heinrich von Ofterdingen et du « voyageur » de Gènes, de Venise et d'Engadine, toujours accompagné d'une « ombre » qui n'est point celle du désespoir, ni du doute, mais sans doute l'ombre de la Mesure qui suit la marche de ces hommes qui vont vers le soleil sans craindre la démesure.

Qu'est-ce que la Figure ? La Figure, nous dit Jünger, est le tout qui englobe plus que la somme des parties. C'est en ce sens que la Figure échappe au déterminisme, qu'il soit économique ou biologique. L'individu du matérialisme libéral demeure soumis au déterminisme, et de ce fait, il appartient encore au monde animal, au « biologique ». Tout ce qui s'explique en terme de logique linéaire, déterministe, appartient encore à la nature, à l'en-deçà des possibilités surhumaines qui sont le propre de l'humanitas. « L'ordre hiérarchique dans le domaine de la Figure ne résulte pas de la loi de cause et d'effet, écrit Jünger mais d'une loi tout autre, celle du sceau et de l'empreinte. » Par ce renversement herméneutique décisif, la pensée de Jünger s'avère beaucoup plus proche de celle d'Evola que l'on ne pourrait le croire de prime abord. Dans le monde hiérarchique, que décrit Jünger où le monde obéit à la loi du sceau et de l'empreinte, les logiques évolutionnistes ou progressistes, qui s'obstinent (comme le nazisme ou le libéralisme darwinien) dans une vision zoologique du genre humain, perdent toute signification. Telle est exactement la Tradition, à laquelle se réfère toute l'œuvre de Julius Evola: « Pour comprendre aussi bien l'esprit traditionnel que la civilisation moderne, en tant que négation de cet esprit, écrit Julius Evola, il faut partir de cette base fondamentale qu'est l'enseignement relatif aux deux natures. Il y a un ordre physique et il y a un ordre métaphysique. Il y a une nature mortelle et il y a la nature des immortels. Il y a la région supérieure de l'être et il y a la région inférieure du devenir. D'une manière plus générale, il y a un visible et un tangible, et avant et au delà de celui-ci, il y a un invisible et un intangible, qui constituent le supra-monde, le principe et la véritable vie. Partout, dans le monde de la Tradition, en Orient et en Occident, sous une forme ou sous une autre, cette connaissance a toujours été présente comme un axe inébranlable autour duquel tout le reste était hiérarchiquement organisé. »

Qu'est-ce que la Figure ? La Figure, nous dit Jünger, est le tout qui englobe plus que la somme des parties. C'est en ce sens que la Figure échappe au déterminisme, qu'il soit économique ou biologique. L'individu du matérialisme libéral demeure soumis au déterminisme, et de ce fait, il appartient encore au monde animal, au « biologique ». Tout ce qui s'explique en terme de logique linéaire, déterministe, appartient encore à la nature, à l'en-deçà des possibilités surhumaines qui sont le propre de l'humanitas. « L'ordre hiérarchique dans le domaine de la Figure ne résulte pas de la loi de cause et d'effet, écrit Jünger mais d'une loi tout autre, celle du sceau et de l'empreinte. » Par ce renversement herméneutique décisif, la pensée de Jünger s'avère beaucoup plus proche de celle d'Evola que l'on ne pourrait le croire de prime abord. Dans le monde hiérarchique, que décrit Jünger où le monde obéit à la loi du sceau et de l'empreinte, les logiques évolutionnistes ou progressistes, qui s'obstinent (comme le nazisme ou le libéralisme darwinien) dans une vision zoologique du genre humain, perdent toute signification. Telle est exactement la Tradition, à laquelle se réfère toute l'œuvre de Julius Evola: « Pour comprendre aussi bien l'esprit traditionnel que la civilisation moderne, en tant que négation de cet esprit, écrit Julius Evola, il faut partir de cette base fondamentale qu'est l'enseignement relatif aux deux natures. Il y a un ordre physique et il y a un ordre métaphysique. Il y a une nature mortelle et il y a la nature des immortels. Il y a la région supérieure de l'être et il y a la région inférieure du devenir. D'une manière plus générale, il y a un visible et un tangible, et avant et au delà de celui-ci, il y a un invisible et un intangible, qui constituent le supra-monde, le principe et la véritable vie. Partout, dans le monde de la Tradition, en Orient et en Occident, sous une forme ou sous une autre, cette connaissance a toujours été présente comme un axe inébranlable autour duquel tout le reste était hiérarchiquement organisé. »

Apollon n'est pas seulement le dieu de la mesure et de l'harmonie, le dieu des proportions rassurantes et de l'ordre classique, le dieu de Versailles et du Roi-Soleil, c'est aussi le dieu dont l'éclair rend fou. La sculpturale exactitude apollinienne naît d'une intensité lumineuse qui n'est pas moins dangereuse que l'ivresse dionysiaque. Apollon et Dionysos ont des fidèles de rangs divers. Certains rendent à ces dieux des hommages qui ne sont pas dépourvus de banalité, d'autres haussent leur révérence au rang le plus haut. L'Apollon qui se réverbère dans les poèmes d’Hölderlin témoigne d'un ordre de grandeur inconnu jusqu'alors et depuis.

Apollon n'est pas seulement le dieu de la mesure et de l'harmonie, le dieu des proportions rassurantes et de l'ordre classique, le dieu de Versailles et du Roi-Soleil, c'est aussi le dieu dont l'éclair rend fou. La sculpturale exactitude apollinienne naît d'une intensité lumineuse qui n'est pas moins dangereuse que l'ivresse dionysiaque. Apollon et Dionysos ont des fidèles de rangs divers. Certains rendent à ces dieux des hommages qui ne sont pas dépourvus de banalité, d'autres haussent leur révérence au rang le plus haut. L'Apollon qui se réverbère dans les poèmes d’Hölderlin témoigne d'un ordre de grandeur inconnu jusqu'alors et depuis. Une erreur assez répandue consiste à séparer, voire à opposer, l'œuvre de Jünger qui précède la seconde guerre mondiale de celle qui lui succède. Or, si certaines interprétations se nuancent, si le point de vue gagne de la hauteur, la situation décrite par Le Travailleur, Orages d'Acier ou Le Cœur aventureux, première version, n'en demeure pas moins riche d'enseignements. L'œuvre de Jünger n'est point de celles où chaque nouveau livre frappe d'inconsistance le précédent. Certes, à la tonalité expressionniste des premiers écrits succèderont d'autres tonalités,- mais ce serait faire preuve d'un indubitable manque d'oreille que d'entendre la voix de l'auteur des Ciseaux comme moins assurée, plus vague, moins rigoureuse, que celle de l'auteur du Travailleur ou de La Mobilisation Totale. L'accroissement de l'intensité fait passer la pensée dans l'ordre du subtil, selon un engagement plus radical que tout engagement politique ou guerrier. Des considérations de cette sorte ne peuvent être comprises intimement que par ceux qui reconnaissent, par exemple, que l'œuvre d’Hölderlin ne cède en rien en radicalité et en intensité à celle d'Artaud ou d'Ezra Pound.

Une erreur assez répandue consiste à séparer, voire à opposer, l'œuvre de Jünger qui précède la seconde guerre mondiale de celle qui lui succède. Or, si certaines interprétations se nuancent, si le point de vue gagne de la hauteur, la situation décrite par Le Travailleur, Orages d'Acier ou Le Cœur aventureux, première version, n'en demeure pas moins riche d'enseignements. L'œuvre de Jünger n'est point de celles où chaque nouveau livre frappe d'inconsistance le précédent. Certes, à la tonalité expressionniste des premiers écrits succèderont d'autres tonalités,- mais ce serait faire preuve d'un indubitable manque d'oreille que d'entendre la voix de l'auteur des Ciseaux comme moins assurée, plus vague, moins rigoureuse, que celle de l'auteur du Travailleur ou de La Mobilisation Totale. L'accroissement de l'intensité fait passer la pensée dans l'ordre du subtil, selon un engagement plus radical que tout engagement politique ou guerrier. Des considérations de cette sorte ne peuvent être comprises intimement que par ceux qui reconnaissent, par exemple, que l'œuvre d’Hölderlin ne cède en rien en radicalité et en intensité à celle d'Artaud ou d'Ezra Pound.

Le titanisme opère d'abord sur le mode de la distanciation, et ensuite sur le mode de l'enfermement. L'immédiate beauté de la cicindèle témoigne, en la circonstance, de l'immensité du monde étrange, du monde des dieux, qui est aussi le monde de la nature, de la physis. La physis est l'empreinte de la métaphysique. Le monde métaphysique des dieux préfigure, au sens exact, notre entente avec le monde de la nature.

Le titanisme opère d'abord sur le mode de la distanciation, et ensuite sur le mode de l'enfermement. L'immédiate beauté de la cicindèle témoigne, en la circonstance, de l'immensité du monde étrange, du monde des dieux, qui est aussi le monde de la nature, de la physis. La physis est l'empreinte de la métaphysique. Le monde métaphysique des dieux préfigure, au sens exact, notre entente avec le monde de la nature.

Ce qui a pour vocation d'être connu, on nous pardonnera d'y insister, n'est pas seulement l'œuvre dans sa réalité immanente ou l'auteur lui-même, selon qu'on veuille l'aborder sous l'angle de la psychologie ou de l'histoire, mais le monde lui-même. Toute œuvre digne de ce nom, qui s'écarte du souci narcissique ou formaliste, éclaire certains aspects du monde qui, pour ne pouvoir être abordés que par cette œuvre, n'en demeurent pas moins objectifs. Ce que l'œuvre donne à comprendre est certes une connaissance privilégiée, et c'est aussi en ce sens que l'on peut parler d'initiation, mais ce privilège a pour vocation essentielle d'être partagé. L'aspect du monde que l'œuvre éclaire est son privilège mais il est aussi le monde lui-même car l'œuvre fait elle-même partie du monde. Il ne viendrait à l'esprit d'aucun astronome de borner son étude au mécanisme du télescope. Les critiques littéraires souvent sont moins avisés que les astronomes lorsqu'ils refusent de voir ce que l'œuvre donne à voir pour n'en étudier que les mécanismes linguistiques, ou lorsqu'ils tentent d'expliquer par la psychanalyse une oeuvre qui, à la rigueur, expliquerait une démarche psychanalytique mais ne saurait en aucune façon être expliquée par elle.

Ce qui a pour vocation d'être connu, on nous pardonnera d'y insister, n'est pas seulement l'œuvre dans sa réalité immanente ou l'auteur lui-même, selon qu'on veuille l'aborder sous l'angle de la psychologie ou de l'histoire, mais le monde lui-même. Toute œuvre digne de ce nom, qui s'écarte du souci narcissique ou formaliste, éclaire certains aspects du monde qui, pour ne pouvoir être abordés que par cette œuvre, n'en demeurent pas moins objectifs. Ce que l'œuvre donne à comprendre est certes une connaissance privilégiée, et c'est aussi en ce sens que l'on peut parler d'initiation, mais ce privilège a pour vocation essentielle d'être partagé. L'aspect du monde que l'œuvre éclaire est son privilège mais il est aussi le monde lui-même car l'œuvre fait elle-même partie du monde. Il ne viendrait à l'esprit d'aucun astronome de borner son étude au mécanisme du télescope. Les critiques littéraires souvent sont moins avisés que les astronomes lorsqu'ils refusent de voir ce que l'œuvre donne à voir pour n'en étudier que les mécanismes linguistiques, ou lorsqu'ils tentent d'expliquer par la psychanalyse une oeuvre qui, à la rigueur, expliquerait une démarche psychanalytique mais ne saurait en aucune façon être expliquée par elle.

Aux mains de Schwarzenberg, les sciences, en étant détournées de leur usage titanique révèlent leur sens véritable. Ce sens véritable, nous dit Jünger, est lié à la structure et à la croissance. La limite des sciences dévouées à la technique est d'être absurdement linéaire, progressive, de poursuivre leur but dans la preuve technologique au lieu de revenir au dessein originel de la gnose qui permettra de comprendre la structure et la croissance. La connaissance est elle-même structure et croissance, elle ordonne l'entendement selon des lois d'accroissement et d'assomption. Du Mage, Jünger dit encore: « Il ne concevait pas l'Histoire ni les sciences de la nature, ni la cosmogonie comme une évolution telle qu'on se la représente à l'ordinaire, sous la forme de droites, de spirales ou de cercles. Il les voyait plutôt comme une série de sections de sphère, appliquées contre des noyaux étrangers au temps et à l'étendue. C'était de ces noyaux que rayonnaient les structures et les qualités, de plus en plus loin. »

Aux mains de Schwarzenberg, les sciences, en étant détournées de leur usage titanique révèlent leur sens véritable. Ce sens véritable, nous dit Jünger, est lié à la structure et à la croissance. La limite des sciences dévouées à la technique est d'être absurdement linéaire, progressive, de poursuivre leur but dans la preuve technologique au lieu de revenir au dessein originel de la gnose qui permettra de comprendre la structure et la croissance. La connaissance est elle-même structure et croissance, elle ordonne l'entendement selon des lois d'accroissement et d'assomption. Du Mage, Jünger dit encore: « Il ne concevait pas l'Histoire ni les sciences de la nature, ni la cosmogonie comme une évolution telle qu'on se la représente à l'ordinaire, sous la forme de droites, de spirales ou de cercles. Il les voyait plutôt comme une série de sections de sphère, appliquées contre des noyaux étrangers au temps et à l'étendue. C'était de ces noyaux que rayonnaient les structures et les qualités, de plus en plus loin. »

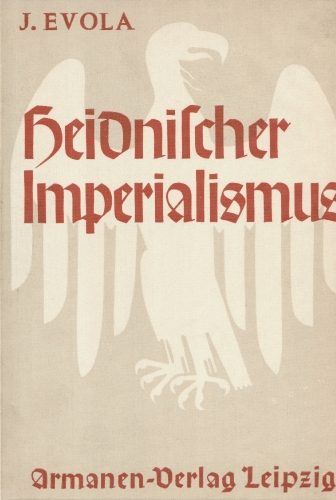

Tout cela est très révélateur de l'influence de la culture allemande sur l'œuvre d'Evola. Mais il faut ajouter d'autres données : en rappelant ici ce qui a été mentionné dans la biographie d’Evola, au premier chapitre, je me souviens de l’évocation des longs séjours d'Evola en Autriche et en Allemagne, des nombreuses conférences qui s'y sont tenues, de ses relations avec les représentants de la tradition aristocratique et conservatrice d'Europe centrale et de la révolution conservatrice, etc. En outre, dans les pays germanophones, Evola jouissait, au moins jusqu'à la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, d'une notoriété différente de celle qu'il avait en Italie, car il y fut reçu comme l'exposant d'un courant particulier de la pensée italienne, et cela depuis 1933, année de la publication de Heidnischer Imperialismus. Voici l'opinion d'Adriano Romualdi sur le sujet : "L'action d'Evola en Allemagne n'était pas politique, même si elle a contribué à dissiper de nombreux malentendus et à préparer une entente entre le fascisme et le national-socialisme. Elle a investi le sens de ces traditions qui, en Italie et en Allemagne, ont été évoquées par les régimes, comme le symbole romain et le mythe nordique, le sens du classicisme et du romantisme, ou des oppositions artificielles, comme celle entre la romanité et le germanisme".

Tout cela est très révélateur de l'influence de la culture allemande sur l'œuvre d'Evola. Mais il faut ajouter d'autres données : en rappelant ici ce qui a été mentionné dans la biographie d’Evola, au premier chapitre, je me souviens de l’évocation des longs séjours d'Evola en Autriche et en Allemagne, des nombreuses conférences qui s'y sont tenues, de ses relations avec les représentants de la tradition aristocratique et conservatrice d'Europe centrale et de la révolution conservatrice, etc. En outre, dans les pays germanophones, Evola jouissait, au moins jusqu'à la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, d'une notoriété différente de celle qu'il avait en Italie, car il y fut reçu comme l'exposant d'un courant particulier de la pensée italienne, et cela depuis 1933, année de la publication de Heidnischer Imperialismus. Voici l'opinion d'Adriano Romualdi sur le sujet : "L'action d'Evola en Allemagne n'était pas politique, même si elle a contribué à dissiper de nombreux malentendus et à préparer une entente entre le fascisme et le national-socialisme. Elle a investi le sens de ces traditions qui, en Italie et en Allemagne, ont été évoquées par les régimes, comme le symbole romain et le mythe nordique, le sens du classicisme et du romantisme, ou des oppositions artificielles, comme celle entre la romanité et le germanisme".

Mais les différences, du point de vue de l’environnement, sont beaucoup plus marquées. Dans son essai sur le Troisième Reich, qui décrit les courants culturels complexes et souvent irréductibles qui ont coopéré à sa genèse, Evola écrit : "Après la Première Guerre mondiale, la situation en Allemagne était nettement différente de celle de l'Italie. [...] Mussolini a dû créer presque tout à partir de rien, en ce sens qu'au moment de combattre la subversion rouge et de remettre l'État sur pied, il ne pouvait pas se référer à une tradition au sens le plus élevé du terme. Tout bien considéré, ce qui était menacé n'était que l'extension de l'Italie démocratique du XIXe siècle, avec un héritage du Risorgimento influencé par les idéologies de la Révolution française, avec une monarchie qui régnait mais ne gouvernait pas et n’avait pas d’articulations sociales solides. En Allemagne, les choses étaient différentes. Même après l'effondrement militaire et la révolution de 1918, et malgré le marasme social, il y avait encore des vestiges profondément enracinés dans ce monde hiérarchique, parfois encore féodal, centré sur les valeurs de l'État et de son autorité, faisant partie de la tradition précédente, en particulier du prussianisme. […]. En fait, en Europe centrale, les idées de la Révolution française n'ont jamais pris autant d'ampleur que dans les autres pays européens" .