by Keith Preston - http://attackthesystem.com/

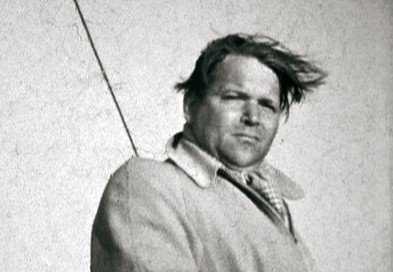

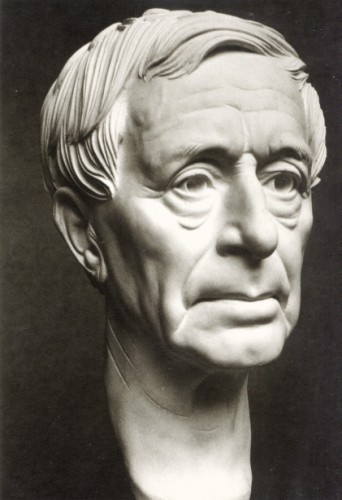

Perhaps the most interesting, poignant and, possibly, threatening type of writer and thinker is the one who not only defies conventional categorizations of thought but also offers a deeply penetrating critique of those illusions many hold to be the most sacred. Ernst Junger (1895-1998), who first came to literary prominence during Germany’s Weimar era as a diarist of the experiences of a front line stormtrooper during the Great War, is one such writer. Both the controversial nature of his writing and its staying power are demonstrated by the fact that he remains one of the most important yet widely disliked literary and cultural figures of twentieth century Germany. As recently as 1993, when Junger would have been ninety-eight years of age, he was the subject of an intensely hostile exchange in the “New York Review of Books” between an admirer and a detractor of his work.(1) On the occasion of his one hundreth birthday in 1995, Junger was the subject of a scathing, derisive musical performed in East Berlin. Yet Junger was also the recipient of Germany’s most prestigious literary awards, the Goethe Prize and the Schiller Memorial Prize. Junger, who converted to Catholicism at the age of 101, received a commendation from Pope John Paul II and was an honored guest of French President Francois Mitterand and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl at the Franco-German reconciliation ceremony at Verdun in 1984. Though he was an exceptional achiever during virtually every stage of his extraordinarily long life, it was his work during the Weimar period that not only secured for a Junger a presence in German cultural and political history, but also became the standard by which much of his later work was evaluated and by which his reputation was, and still is, debated. (2)

Ernst Junger was born on March 29, 1895 in Heidelberg, but was raised in Hanover. His father, also named Ernst, was an academically trained chemist who became wealthy as the owner of a pharmaceutical manufacturing business, finding himself successful enough to essentially retire while he was still in his forties. Though raised as an evangelical Protestant, Junger’s father did not believe in any formal religion, nor did his mother, Karoline, an educated middle class German woman whose interests included Germany’s rich literary tradition and the cause of women’s emancipation. His parents’ politics seem to have been liberal, though not radical, in the manner not uncommon to the rising bourgeoise of Germany’s upper middle class during the pre-war period. It was in this affluent, secure bourgeoise environment that Ernst Junger grew up. Indeed, many of Junger’s later activities and professed beliefs are easily understood as a revolt against the comfort and safety of his upbringing. As a child, he was an avid reader of the tales of adventurers and soldiers, but a poor academic student who did not adjust well to the regimented Prussian educational system. Junger’s instructors consistently complained of his inattentiveness. As an adolescent, he became involved with the Wandervogel, roughly the German equivalent of the Boy Scouts.(3)

It was while attending a boarding school near his parents’ home in 1913, at the age of seventeen, that Junger first demonstrated his first propensity for what might be called an “adventurist” way of life. With only six months left before graduation, Junger left school, leaving no word to his family as to his destination. Using money given to him for school-related fees and expenses to buy a firearm and a railroad ticket to Verdun, Junger subsequently enlisted in the French Foreign Legion, an elite military unit of the French armed forces that accepted enlistees of any nationality and had a reputation for attracting fugitives, criminals and career mercenaries. Junger had no intention of staying with the Legion. He only wanted to be posted to Africa, as he eventually was. Junger then deserted, only to be captured and sentenced to jail. Eventually his father found a capable lawyer for his wayward son and secured his release. Junger then returned to his studies and underwent a belated high school graduation. However, it was only a very short time later that Junger was back in uniform. (4)

Warrior and War Diarist

Ernst Junger immediately volunteered for military service when he heard the news that Germany was at war in the summer of 1914. After two months of training, Junger was assigned to a reserve unit stationed at Champagne. He was afraid the war would end before he had the opportunity to see any action. This attitude was not uncommon among many recruits or conscripts who fought in the war for their respective states. The question immediately arises at to why so many young people would wish to look into the face of death with such enthusiasm. Perhaps they really did not understand the horrors that awaited them. In Junger’s case, his rebellion against the security and luxury of his bourgeoise upbringing had already been ably demonstrated by his excursion with the French Foreign Legion. Because of his high school education, something that soldiers of more proletarian origins lacked, Junger was selected to train to become an officer. Shortly before beginning his officer’s training, Junger was exposed to combat for the first time. From the start, he carried pocket-sized notebooks with him and recorded his observations on the front lines. His writings while at the front exhibit a distinctive tone of detachment, as though he is simply an observer watching while the enemy fires at others. In the middle part of 1915, Junger suffered his first war wound, a bullet graze to the thigh that required only two weeks of recovery time. Afterwards, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant.(5)

At age twenty-one, Junger was the leader of a reconnaissance team at the Somme whose purpose was to go out at night and search for British landmines. Early on, he acquired the reputation of a brave soldier who lacked the preoccupation with his own safety common to most of the fighting men. The introduction of steel artifacts into the war, tanks for the British side and steel helmets for the Germans, made a deep impression on Junger. Wounded three times at the Somme, Junger was awarded the Iron Medal First Class. Upon recovery, he returned to the front lines. A combat daredevil, he once held out against a much larger British force with only twenty men. After being transferred to fight the French at Flanders, he lost ten of his fourteen men and was wounded in the left hand by a blast from French shelling. After being harshly criticized by a superior officer for the number of men lost on that particular mission, Junger began to develop a contempt for the military hierarchy whom he regarded as having achieved their status as a result of their class position, frequently lacking combat experience of their own. In late 1917, having already experienced nearly three full years of combat, Junger was wounded for the fifth time during a surprise assault by the British. He was grazed in the head by a bullet, acquiring two holes in his helmet in the process. His performance in this battle won him the Knights Cross of the Hohenzollerns. In March 1918, Junger participated in another fierce battle with the British, losing 87 of his 150 men. (6)

Nothing impressed Junger more than personal bravery and endurance on the part of soldiers. He once “fell to the ground in tears” at the sight of a young recruit who had only days earlier been unable to carry an ammunition case by himself suddenly being able to carry two cases of missles after surviving an attack of British shells. A recurring theme in Junger’s writings on his war experiences is the way in which war brings out the most savage human impulses. Essentially, human beings are given full license to engage in behavior that would be considered criminal during peacetime. He wrote casually about burning occupied towns during the course of retreat or a shift of position. However, Junger also demonstrated a capacity for merciful behavior during his combat efforts. He refrained from shooting a cornered British soldier after the foe displayed a portrait of his family to Junger. He was wounded yet again in August of 1918. Having been shot in the chest and directly through a lung, this was his most serious wound yet. After being hit, he still managed to shoot dead yet another British officer. As Junger was being carried off the battlefield on a stretcher, one of the stretcher carriers was killed by a British bullet. Another German soldier attempted to carry Junger on his back, but the soldier was shot dead himself and Junger fell to the ground. Finally, a medic recovered him and pulled him out of harm’s way. This episode would be the end of his battle experiences during the Great War.(7)

In Storms of Steel

Junger’s keeping of his wartime diaries paid off quite well in the long run. They were to become the basis of his first and most famous book, In Storms of Steel, published in 1920. The title was given to the book by Junger himself, having found the phrase in an old Icelandic saga. It was at the suggestion of his father that Junger first sought to have his wartime memoirs published. Initially, he found no takers, antiwar sentiment being extremely high in Germany at the time, until his father at last arranged to have the work published privately. In Storms of Steel differs considerably from similar works published by war veterans during the same era, such as Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front and John Dos Passos’ Three Soldiers. Junger’s book reflects none of the disillusionment with war by those experienced in its horrors of the kind found in these other works. Instead, Junger depicted warfare as an adventure in which the soldier faced the highest possible challenge, a battle to the death with a mortal enemy. Though Junger certainly considered himself to be a patriot and, under the influence of Maurice Barres (8), eventually became a strident German nationalist, his depiction of military combat as an idyllic setting where human wills face the supreme test rose far above ordinary nationalist sentiments. Junger’s warrior ideal was not merely the patriot fighting out of a profound sense of loyalty to his country nor the stereotype of the dutiful soldier whose sense of honor and obedience compels him to follow the orders of his superiors in a headlong march towards death. Nor was the warrior prototype exalted by Junger necessarily an idealist fighting for some alleged greater good such as a political ideal or religious devotion. Instead, war itself is the ideal for Junger. On this question, he was profoundly influenced by Nietzsche, whose dictum “a good war justifies any cause”, provides an apt characterization of Junger’s depiction of the life (and death) of the combat soldier. (9)

This aspect of Junger’s outlook is illustrated quite well by the ending he chose to give to the first edition of In Storms of Steel. Although the second edition (published in 1926) ends with the nationalist rallying cry, “Germany lives and shall never go under!”, a sentiment that was deleted for the third edition published in 1934 at the onset of the Nazi era, the original edition ends simply with Junger in the hospital after being wounded for the final time and receiving word that he has received yet another commendation for his valor as a combat soldier. There is no mention of Germany’s defeat a few months later. Nationalism aside, the book is clearly about Junger, not about Germany, and Junger’s depiction of the war simultaneously displays an extraordinary level detachment for someone who lived in the face of death for four years and a highly personalized account of the war where battle is first and foremost about the assertion of one’s own “will to power” with cliched patriotic pieties being of secondary concern.

Indeed, Junger goes so far as to say there were winners and losers on both sides of the war. The true winners were not those who fought in a particular army or for a particular country, but who rose to the challenge placed before them and essentially achieved what Junger regarded as a higher state of enlightenment. He believed the war had revealed certain fundamental truths about the human condition. First, the illusions of the old bourgeoise order concerning peace, progress and prosperity had been inalterably shattered. This was not an uncommon sentiment during that time, but it is a revelation that Junger seems to revel in while others found it to be overwhelmingly devastating. Indeed, the lifelong champion of Enlightenment liberalism, Bertrand Russell, whose life was almost as long as Junger’s and who observed many of the same events from a much different philosophical perspective, once remarked that no one who had been born before 1914 knew what it was like to be truly happy.(10) A second observation advanced by Junger had to do with the role of technology in transforming the nature of war, not only in a purely mechanical sense, but on a much greater existential level. Before, man had commanded weaponry in the course of combat. Now weaponry of the kind made possible by modern technology and industrial civilization essentially commanded man. The machines did the fighting. Man simply resisted this external domination. Lastly, the supremacy of might and the ruthless nature of human existence had been demonstrated. Nietzsche was right. The tragic, Darwinian nature of the human condition had been revealed as an irrevocable law.

In Storms of Steel was only the first of several works based on his experiences as a combat officer that were produced by Junger during the 1920s. Copse 125 described a battle between two small groups of combatants. In this work, Junger continued to explore the philosophical themes present in his first work. The type of technologically driven warfare that emerged during the Great War is characterized as reducing men to automatons driven by airplanes, tanks and machine guns. Once again, jingoistic nationalism is downplayed as a contributing factor to the essence of combat soldier’s spirit. Another work of Junger’s from the early 1920s, Battle as Inner Experience, explored the psychology of war. Junger suggested that civilization itself was but a mere mask for the “primordial” nature of humanity that once again reveals itself during war. Indeed, war had the effect of elevating humanity to a higher level. The warrior becomes a kind of god-like animal, divine in his superhuman qualities, but animalistic in his bloodlust. The perpetual threat of imminent death is a kind of intoxicant. Life is at its finest when death is closest. Junger described war as a struggle for a cause that overshadows the respective political or cultural ideals of the combatants. This overarching cause is courage. The fighter is honor bound to respect the courage of his mortal enemy. Drawing on the philosophy of Nietzsche, Junger argued that the war had produced a “new race” that had replaced the old pieties, such as those drawn from religion, with a new recognition of the primacy of the “will to power”.(11)

Conservative Revolutionary

Junger’s writings about the war quickly earned him the status of a celebrity during the Weimar period. Battle as Inner Experience contained the prescient suggestion that the young men who had experienced the greatest war the world had yet to see at that point could never be successfully re-integrated into the old bougeoise order from which they came. For these fighters, the war had been a spiritual experience. Having endured so much only to see their side lose on such seemingly humiliating terms, the veterans of the war were aliens to the rationalistic, anti-militarist, liberal republic that emerged in 1918 at the close of the war. Junger was at his parents’ home recovering from war wounds during the time of the attempted coup by the leftist workers’ and soldiers’ councils and subsequent suppression of these by the Freikorps. He experimented with psychoactive drugs such as cocaine and opium during this time, something that he would continue to do much later in life. Upon recovery, he went back into active duty in the much diminished Germany army. Junger’s earliest works, such as In Storms of Steel, were published during this time and he also wrote for military journals on the more technical and specialized aspects of combat and military technology. Interestingly, Junger attributed Germany’s defeat in the war simply to poor leadership, both military and civilian, and rejected the “stab in the back” legend that consoled less keen veterans.

After leaving the army in 1923, Junger continued to write, producing a novella about a soldier during the war titled Sturm, and also began to study the philosophy of Oswald Spengler. His first work as a philosopher of nationalism appeared the Nazi paper Volkischer Beobachter in September, 1923.

Critiquing the failed Marxist revolution of 1918, Junger argued that the leftist coup failed because of its lacking of fresh ideas. It was simply a regurgitation of the egalitarian outllook of the French Revolution. The revolutionary left appealed only to the material wants of the Germany people in Junger’s views. A successful revolution would have to be much more than that. It would have to appeal to their spiritual or “folkish” instincts as well. Over the next few years Junger studied the natural sciences at the University of Leipzig and in 1925, at age thirty, he married nineteen-year-old Gretha von Jeinsen. Around this time, he also became a full-time political writer. Junger was hostile to Weimar democracy and its commercial bourgeiose society. His emerging political ideal was one of an elite warrior caste that stood above petty partisan politics and the middle class obsession with material acquisition. Junger became involved with the the Stahlhelm, a right-wing veterans group, and was a contributer to its paper, Die Standardite. He associated himself with the younger, more militant members of the organization who favored an uncompromised nationalist revolution and eschewed the parliamentary system. Junger’s weekly column in Die Standardite disseminated his nationalist ideology to his less educated readers. Junger’s views at this point were a mixture of Spengler, Social Darwinism, the traditionalist philosophy of the French rightist Maurice Barres, opposition to the internationalism of the left that had seemingly been discredited by the events of 1914, irrationalism and anti-parliamentarianism. He took a favorable view of the working class and praised the Nazis’ efforts to win proletarian sympathies. Junger also argued that a nationalist outlook need not be attached to one particular form of government, even suggesting that a liberal monarchy would be inferior to a nationalist republic.(12)

In an essay for Die Standardite titled “The Machine”, Junger argued that the principal struggle was not between social classes or political parties but between man and technology. He was not anti-technological in a Luddite sense, but regarded the technological apparatus of modernity to have achieved a position of superiority over mankind which needed to be reversed. He was concerned that the mechanized efficiency of modern life produced a corrosive effect on the human spirit. Junger considered the Nazis’ glorification of peasant life to be antiquated. Ever the realist, he believed the world of the rural people to be in a state of irreversible decline. Instead, Junger espoused a “metropolitan nationalism” centered on the urban working class. Nationalism was the antidote to the anti-particularist materialism of the Marxists who, in Junger’s views, simply mirrored the liberals in their efforts to reduce the individual to a component of a mechanized mass society. The humanitarian rhetoric of the left Junger dismissed as the hypocritical cant of power-seekers feigning benevolence. He began to pin his hopes for a nationalist revolution on the younger veterans who comprised much of the urban working class.

In 1926, Junger became editor of Arminius, which also featured the writings of Nazi leaders like Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels. In 1927, he contributed his final article to the Nazi paper, calling for a new definition of the “worker”, one not rooted in Marxist ideology but the idea of the worker as a civilian counterpart to the soldier who struggles fervently for the nationalist ideal. Junger and Hitler had exchanged copies of their respective writings and a scheduled meeting between the two was canceled due to a change in Hitler’s itinerary. Junger respected Hitler’s abilities as an orator, but came to feel he lacked the ability to become a true leader. He also found Nazi ideology to be intellectually shallow, many of the Nazi movement’s leaders to be talentless and was displeased by the vulgarity, crassly opportunistic and overly theatrical aspects of Nazi public rallies. Always an elitist, Junger considered the Nazis’ pandering the common people to be debased. As he became more skeptical of the Nazis, Junger began writing for a wider circle of readers beyond that of the militant nationalist right-wing. His works began to appear in the Jewish liberal Leopold Schwarzchild’s Das Tagebuch and the “national-bolshevik” Ernst Niekisch’s Widerstand.

Junger began to assemble around himself an elite corps of bohemian, eccentric intellectuals who would meet regularly on Friday evenings. This group included some of the most interesting personalities of the Weimar period. Among them were the Freikorps veteran Ernst von Salomon, Otto von Strasser, who with his brother Gregor led a leftist anti-Hitler faction of the Nazi movement, the national-bolshevik Niekisch, the Jewish anarchist Erich Muhsam who had figured prominently in the early phase of the failed leftist revolution of 1918, the American writer Thomas Wolfe and the expressionist writer Arnolt Bronnen. Many among this group espoused a type of revolutionary socialism based on nationalism rather than class, disdaining the Nazis’ opportunistic outreach efforts to the middle class. Some, like Niekisch, favored an alliance between Germany and Soviet Russia against the liberal-capitalist powers of the West. Occasionally, Joseph Goebbels would turn up at these meetings hoping to convert the group, particularly Junger himself, whose war writings he had admired, to the Nazi cause. These efforts by the Nazi propaganda master proved unsuccessful. Junger regarded Goebbels as a shallow ideologue who spoke in platitudes even in private conversation.(13)

The final break between Ernst Junger and the NSDAP occurred in September 1929. Junger published an article in Schwarzchild’s Tagebuch attacking and ridiculing the Nazis as sell outs for having reinvented themselves as a parliamentary party. He also dismissed their racism and anti-Semitism as ridiculous, stating that according to the Nazis a nationalist is simply someone who “eats three Jews for breakfast.” He condemned the Nazis for pandering to the liberal middle class and reactionary traditional conservatives “with lengthy tirades against the decline in morals, against abortion, strikes, lockouts, and the reduction of police and military forces.” Goebbels responded by attacking Junger in the Nazi press, accusing him being motivated by personal literary ambition, and insisting this had caused him “to vilify the national socialist movement, probably so as to make himself popular in his new kosher surroundings” and dismissing Junger’s attacks by proclaiming the Nazis did not “debate with renegades who abuse us in the smutty press of Jewish traitors.”(14)

Junger on the Jewish Question

Junger held complicated views on the question of German Jews. He considered anti-Semitism of the type espoused by Hitler to be crude and reactionary. Yet his own version of nationalism required a level of homogeneity that was difficult to reconcile with the subnational status of Germany Jewry. Junger suggested that Jews should assimilate and pledge their loyalty to Germany once and for all. Yet he expressed admiration for Orthodox Judaism and indifference to Zionism. Junger maintained personal friendships with Jews and wrote for a Jewish owned publication. During this time his Jewish publisher Schwarzchild published an article examining Junger’s views on the Jews of Germany. Schwarzchild insisted that Junger was nothing like his Nazi rivals on the far right. Junger’s nationalism was based on an aristocratic warrior ethos, while Hitler’s was more comparable to the criminal underworld. Hitler’s men were “plebian alley scum”. However, Schwarzchild also characterized Junger’s rendition of nationalism as motivated by little more than a fervent rejection of bourgeoise society and lacking in attention to political realities and serious economic questions.(15)

The Worker

Other than In Storms of Steel, Junger’s The Worker: Mastery and Form was his most influential work from the Weimar era. Junger would later distance himself from this work, published in 1932, and it was reprinted in the 1950s only after Junger was prompted to do so by Martin Heidegger.

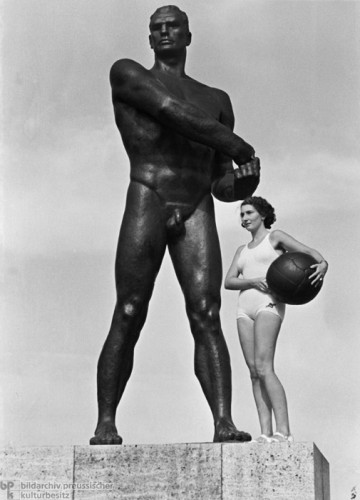

In The Worker, Junger outlines his vision of a future state ordered as a technocracy based on workers and soldiers led by a warrior elite. Workers are no longer simply components of an industrial machine, whether capitalist or communist, but have become a kind of civilian-soldier operating as an economic warrior. Just as the soldier glories in his accomplishments in battle, so does the worker glory in the achievements expressed through his work. Junger predicted that continued technological advancements would render the worker/capitalist dichotomy obsolete. He also incorporated the political philosophy of his friend Carl Schmitt into his worldview. As Schmitt saw international relations as a Hobbesian battle between rival powers, Junger believed each state would eventually adopt a system not unlike what he described in The Worker. Each state would maintain its own technocratic order with the workers and soldiers of each country playing essentially the same role on behalf of their respective nations. International affairs would be a crucible where the will to power of the different nations would be tested.

Junger’s vision contains a certain amount prescience. The general trend in politics at the time was a movement towards the kind of technocratic state Junger described. These took on many varied forms including German National Socialism, Italian Fascism, Soviet Communism, the growing welfare states of Western Europe and America’s New Deal. Coming on the eve of World War Two, Junger’s prediction of a global Hobbesian struggle between national collectives possessing previously unimagined levels of technological sophistication also seems rather prophetic. Junger once again attacked the bourgeoise as anachronistic. Its values of material luxury and safety he regarded as unfit for the violent world of the future. (16)

The National Socialist Era

By the time Hitler took power in 1933, Junger’s war writings had become commonly used in high schools and universities as examples of wartime literature, and Junger enjoyed success within the context of German popular culture as well. Excerpts of Junger’s works were featured in military journals. The Nazis tried to coopt his semi-celebrity status, but he was uncooperative. Junger was appointed to the Nazified German Academcy of Poetry, but declined the position. When the Nazi Party’s paper published some of his work in 1934, Junger wrote a letter of protest. The Nazi regime, despite its best efforts to capitalize on his reputation, viewed Junger with suspicioun. His past association with the national-bolshevik Ersnt Niekisch, the Jewish anarchist Erich Muhsam and the anti-Hitler Nazi Otto von Strasser, all of whom were either eventually killed or exiled by the Third Reich, led the Nazis to regard Junger as a potential subversive. On several occasions, Junger received visits from the Gestapo in search of some of his former friends. During the early years of the Nazi regime, Junger was in the fortunate position of being able to economically afford travel outside of Germany. He journeyed to Norway, Brazil, Greece and Morocco during this time, and published several works based on his travels.(17)

Junger’s most significant work from the Nazi period is the novel On the Marble Cliffs. The book is an allegorical attack on the Hitler regime. It was written in 1939, the same year that Junger reentered the German army. The book describes a mysterious villian that threatens a community, a sinister warlord called the “Head Ranger”. This character is never featured in the plot of the novel, but maintains a forboding presence that is universal (much like “Big Brother” in George Orwell’s 1984). Another character in the novel, “Braquemart”, is described as having physical characteristics remarkably similar to those of Goebbels. The book sold fourteen thousand copies during its first two weeks in publication. Swiss reviewers immediately recognized the allegorical references to the Nazi state in the novel. The Nazi Party’s organ, Volkische Beobachter, stated that Ernst Jünger was flirting with a bullet to the head. Goebbels urged Hitler to ban the book, but Hitler refused, probably not wanting to show his hand. Indeed, Hitler gave orders that Junger not be harmed.(18)

Junger was stationed in France for most of the Second World War. Once again, he kept diaries of the experience. Once again, he expressed concern that he might not get to see any action before the war was over. While Junger did not have the opportunity to experience the level of danger and daredevil heroics he had during the Great War, he did receive yet another medal, the Iron Cross, for retrieving the body of a dead corporal while under heavy fire. Junger also published some of his war diaries during this time. However, the German government took a dim view of these, viewing them as too sympathetic to the occupied French. Junger’s duties included censorship of the mail coming into France from German civilians. He took a rather liberal approach to this responsibility and simply disposed of incriminating documents rather than turning them over for investigation. In doing so, he probably saved lives. He also encountered members of France’s literary and cultural elite, among them the actor Louis Ferdinand Celine, a raving anti-Semite and pro-Vichyite who suggested Hitler’s harsh measures against the Jews had not been heavy handed enough. As rumors of the Nazi extermination programs began to spread, Junger wrote in his diary that the mechanization of the human spirit of the type he had written about in the past had apparently generated a higher level of human depravity. When he saw three young French-Jewish girls wearing the yellow stars required by the Nazis, he wrote that he felt embarrassed to be in the Nazi army. In July of 1942, Junger observed the mass arrest of French Jews, the beginning of implementation of the “Final Solution”. He described the scene as follows:

“Parents were first separated from their children, so there was wailing to be heard in the streets. At no moment may I forget that I am surrounded by the unfortunate, by those suffering to the very depths, else what sort of person, what sort of officer would I be? The uniform obliges one to grant protection wherever it goes. Of course one has the impression that one must also, like Don Quixote, take on millions.”(19)

An entry into Junger’s diary from October 16, 1943 suggests that an unnamed army officer had told Junger about the use of crematoria and poison gas to murder Jews en masse. Rumors of plots against Hitler circulated among the officers with whom Junger maintained contact. His son, Ernstl, was arrested after an informant claimed he had spoken critically of Hitler. Ernstl Junger was imprisoned for three months, then placed in a penal battalion where he was killed in action in Italy. On July 20, 1944 an unsuccessful assassination attempt was carried out against Hitler. It is still disputed as to whether or not Junger knew of the plot or had a role in its planning. Among those arrested for their role in the attemt on Hitler’s life were members of Junger’s immediate circle of associates and superior officers within the German army. Junger was dishonorably discharged shortly afterward.(20)

Following the close of the Second World War, Junger came under suspicion from the Allied occupational authorities because of his far right-wing nationalist and militarist past. He refused to cooperate with the Allies De-Nazification programs and was barred from publishing for four years. He would go on to live another half century, producing many more literary works, becoming a close friend of Albert Hoffman, the inventor of the hallucinogen LSD, with which he experimented. In a 1977 novel, Eumeswil, he took his tendency towards viewing the world around him with detachment to a newer, more clearly articulated level with his invention of the concept of the “Anarch”. This idea, heavily influenced by the writings of the early nineteenth century German philosopher Max Stirner, championed the solitary individual who remains true to himself within the context of whatever external circumstances happen to be present. Some sample quotations from this work illustrate the philosophy and worldview of the elderly Junger quite well:

“For the anarch, if he remains free of being ruled, whether by sovereign or society, this does not mean he refuses to serve in any way. In general, he serves no worse than anyone else, and sometimes even better, if he likes the game. He only holds back from the pledge, the sacrifice, the ultimate devotion … I serve in the Casbah; if, while doing this, I die for the Condor, it would be an accident, perhaps even an obliging gesture, but nothing more.”

“The egalitarian mania of demagogues is even more dangerous than the brutality of men in gallooned coats. For the anarch, this remains theoretical, because he avoids both sides. Anyone who has been oppressed can get back on his feet if the oppression did not cost him his life. A man who has been equalized is physically and morally ruined. Anyone who is different is not equal; that is one of the reasons why the Jews are so often targeted.”

“The anarch, recognizing no government, but not indulging in paradisal dreams as the anarchist does, is, for that very reason, a neutral observer.”

“Opposition is collaboration.”

“A basic theme for the anarch is how man, left to his own devices, can defy superior force - whether state, society or the elements - by making use of their rules without submitting to them.”

“… malcontents… prowl through the institutions eternally dissatisfied, always disappointed. Connected with this is their love of cellars and rooftops, exile and prisons, and also banishment, on which they actually pride themselves. When the structure finally caves in they are the first to be killed in the collapse. Why do they not know that the world remains inalterable in change? Because they never find their way down to its real depth, their own. That is the sole place of essence, safety. And so they do themselves in.”

“The anarch may not be spared prisons - as one fluke of existence among others. He will then find the fault in himself.”

“We are touching one a … distinction between anarch and anarchist; the relation to authority, to legislative power. The anarchist is their mortal enemy, while the anarch refuses to acknowledge them. He seeks neither to gain hold of them, nor to topple them, nor to alter them - their impact bypasses him. He must resign himself only to the whirlwinds they generate.”

“The anarch is no individualist, either. He wishes to present himself neither as a Great Man nor as a Free Spirit. His own measure is enough for him; freedom is not his goal; it is his property. He does not come on as foe or reformer: one can get along nicely with him in shacks or in palaces. Life is too short and too beautiful to sacrifice for ideas, although contamination is not always avoidable. But hats off to the martyrs.”

“We can expect as little from society as from the state. Salvation lies in the individual.” (21)

Notes:

1. Ian Buruma, “The Anarch at Twilight”, New York Review of Books, Volume 40, No. 12, June 24, 1993. Hilary Barr, “An Exchange on Ernst Junger”, New York Review of Books, Volume 40, No. 21, December 16, 1993.

2. Nevin, Thomas. Ernst Junger and Germany: Into the Abyss, 1914-1945. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1996, pp. 1-7. Loose, Gerhard. Ernst Junger. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1974, preface.

3. Nevin, pp. 9-26. Loose, p. 21

4. Loose, p. 22. Nevin, pp. 27-37.

5. Nevin. p. 49.

6. Ibid., p. 57

7. Ibid., p. 61

8. Maurice Barrès (September 22, 1862 - December 4, 1923) was a French novelist, journalist, an anti-semite, nationalist politician and agitator. Leaning towards the far-left in his youth as a Boulangist deputy, he progressively developed a theory close to Romantic nationalism and shifted to the right during the Dreyfus Affair, leading the Anti-Dreyfusards alongside Charles Maurras. In 1906, he was elected both to the Académie française and as deputy of the Seine department, and until his death he sat with the conservative Entente républicaine démocratique. A strong supporter of the Union sacrée(Holy Union) during World War I, Barrès remained a major influence of generations of French writers, as well as of monarchists, although he was not a monarchist himself. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice_Barr%C3%A8s

9. Nevin, pp. 58, 71, 97.

10. Schilpp, P. A. “The Philosophy of Bertrand Russell”. Reviewed Hermann Weyl, The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 53, No. 4 (Apr., 1946), pp. 208-214.

11. Nevin, pp. 122, 125, 134, 136, 140, 173.

12. Ibid., pp. 75-91.

13. Ibid., p. 107.

14. Ibid., p. 108.

15. Ibid., pp. 109-111.

16. Ibid., pp. 114-140.

17. Ibid., p. 145.

18. Ibid., p. 162.

19. Ibid., p. 189.

20. Ibid., p. 209.

21. Junger, Ernst. Eumeswil. New York: Marion Publishers, 1980, 1993.

Bibliography

Barr, Hilary. “An Exchange on Ernst Junger”, New York Review of Books, Volume 40, No. 21, December 16, 1993.

Braun, Abdalbarr. “Warrior, Waldgaenger, Anarch: An Essay on Ernst Junger’s Concept of the Sovereign Individual”. Archived at http://www.fluxeuropa.com/juenger-anarch.htm

Buruma, Ian. “The Anarch at Twilight”, New York Review of Books, Volume 40, No. 12, June 24, 1993.

Hofmann, Albert. LSD: My Problem Child, Chapter Seven, “Radiance From Ernst Junger”. Archived at http://www.flashback.se/archive/my_problem_child/chapter7.html

Loose, Gerhard. Ernst Junger. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1974.

Hervier, Julien. The Details of Time: Conversations with Ernst Junger. New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1986.

Junger, Ernst. Eumeswil. New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1980, 1993.

Junger, Ernst. In Storms of Steel. New York: Penguin Books, 1920, 1963, 2003.

Junger, Ernst. On the Marble Cliffs. New York: Duenewald Printing Corporation, 1947.

Nevin, Thomas. Ernst Junger and Germnay: Into the Abyss, 1914-1945. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1996.

Schilpp, P. A. “The Philosophy of Bertrand Russell”. Reviewed Hermann Weyl, The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 53, No. 4 (Apr., 1946), pp. 208-214.

Stern, J. P. Ernst Junger. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953.

Zavrel, Consul B. John. “Ernst Junger is Still Working at 102″. Archived at http://www.meaus.com/Ernst%20Junger%20at%20102.html

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

DURING THE CLOSING YEARS of the 19th century, the limitations and inadequacies of the superficial positivism that had dominated European thought for so many decades were becoming increasingly apparent to critical observers. The wholesale repudiation of metaphysics that Tyndall, Haeckel and Büchner had proclaimed as a liberation from the superstitions and false doctrines that had misled benighted investigators of earlier times, was now seen as having contributed significantly to the bankruptcy of positivism itself. Ironically, a critical examination of the unacknowledged epistemological assumptions of the positivists clearly revealed that not only had Haeckel and his ilk been unsuccessful in their attempt to free themselves from metaphysical presuppositions, but they had, in effect, merely switched their allegiance from the grand systems of speculative metaphysics that had been constructed in previous eras by the Platonists, medieval scholastics, and post-Kantian idealists whom they abominated, in order to adhere to a ludicrous, ersatz metaphysics of whose existence they were completely unaware.

DURING THE CLOSING YEARS of the 19th century, the limitations and inadequacies of the superficial positivism that had dominated European thought for so many decades were becoming increasingly apparent to critical observers. The wholesale repudiation of metaphysics that Tyndall, Haeckel and Büchner had proclaimed as a liberation from the superstitions and false doctrines that had misled benighted investigators of earlier times, was now seen as having contributed significantly to the bankruptcy of positivism itself. Ironically, a critical examination of the unacknowledged epistemological assumptions of the positivists clearly revealed that not only had Haeckel and his ilk been unsuccessful in their attempt to free themselves from metaphysical presuppositions, but they had, in effect, merely switched their allegiance from the grand systems of speculative metaphysics that had been constructed in previous eras by the Platonists, medieval scholastics, and post-Kantian idealists whom they abominated, in order to adhere to a ludicrous, ersatz metaphysics of whose existence they were completely unaware.

sich zu bezeichnen angewohnt hat. Insbesondere sein sowohl wissenschaftlichen Ansprüchen wie allgemeinverständlicher Darstellung gerecht werdendes Buch „Preußen. Geschichte eines Staates“ (1) ist als geschichtliche Einführung bis heute unübertroffen. Eine von Schoeps veranstaltete Preußen-Anthologie „Das war Preußen. Zeugnisse der Jahrhunderte“ wurde im übrigen von Julius Evola ins Italienische übersetzt. (2)

sich zu bezeichnen angewohnt hat. Insbesondere sein sowohl wissenschaftlichen Ansprüchen wie allgemeinverständlicher Darstellung gerecht werdendes Buch „Preußen. Geschichte eines Staates“ (1) ist als geschichtliche Einführung bis heute unübertroffen. Eine von Schoeps veranstaltete Preußen-Anthologie „Das war Preußen. Zeugnisse der Jahrhunderte“ wurde im übrigen von Julius Evola ins Italienische übersetzt. (2)

In seinem Buch „Gottheit und Menschheit. Die großen Religionsstifter und ihre Lehren“ (Stuttgart: Steingrüben 1950) nimmt Schoeps auch zum Islam Stellung, es hat aber den Anschein, dies geschähe mehr der Vollständigkeit halber als von Interesse oder Kompetenz her. Schoeps reiht einige der Platitüden der Orientalistik über den unoriginellen, allzumenschlichen usw. Propheten des Islam aneinander und charakterisiert den Islam als in seinem Prädestitationsdenken und seiner Schicksalsgläubigkeit „calvinistisch“, was genauso sinnvoll ist, wie das Christentum – unter Ausblendung all seiner anderen Strömungen – als calvinistisch zu bezeichnen. Tatsächlich schreibt Schoeps auch von der entgegengesetzten „pantheistischen“ Strömung, die Einseitigkeit durch eine zweite ergänzend. Denn in Wirklichkeit ist Ibn Arabi als wichtigster Vertreter des esoterischen Islam genausowenig pantheistisch wie Shankara, Meister Eckart oder Lao-Tse, deren grundsätzliche Identität mit seiner „Mystik“ oder vielmehr Gnosis aufgezeigt werden kann. Auch das beklagte „allzumenschliche“ also anscheinend unethische Verhalten des Propheten muß hinterfragt werden, denn es beruht auf einigen späten Hadithen. Träte uns Muhammad als fehlerlose Idealgestalt entgegen, wären die Orientalisten sofort bei der Stelle, um den geschichtlichen Wahrheitsgehalt dieser Stellen in Zweifel zu ziehen. Tatsächlich sind diese Berichte über Fehler und unmoralisches Verhalten aber Hadithen – vorwiegend aus der „Hadithfabrik“ von

In seinem Buch „Gottheit und Menschheit. Die großen Religionsstifter und ihre Lehren“ (Stuttgart: Steingrüben 1950) nimmt Schoeps auch zum Islam Stellung, es hat aber den Anschein, dies geschähe mehr der Vollständigkeit halber als von Interesse oder Kompetenz her. Schoeps reiht einige der Platitüden der Orientalistik über den unoriginellen, allzumenschlichen usw. Propheten des Islam aneinander und charakterisiert den Islam als in seinem Prädestitationsdenken und seiner Schicksalsgläubigkeit „calvinistisch“, was genauso sinnvoll ist, wie das Christentum – unter Ausblendung all seiner anderen Strömungen – als calvinistisch zu bezeichnen. Tatsächlich schreibt Schoeps auch von der entgegengesetzten „pantheistischen“ Strömung, die Einseitigkeit durch eine zweite ergänzend. Denn in Wirklichkeit ist Ibn Arabi als wichtigster Vertreter des esoterischen Islam genausowenig pantheistisch wie Shankara, Meister Eckart oder Lao-Tse, deren grundsätzliche Identität mit seiner „Mystik“ oder vielmehr Gnosis aufgezeigt werden kann. Auch das beklagte „allzumenschliche“ also anscheinend unethische Verhalten des Propheten muß hinterfragt werden, denn es beruht auf einigen späten Hadithen. Träte uns Muhammad als fehlerlose Idealgestalt entgegen, wären die Orientalisten sofort bei der Stelle, um den geschichtlichen Wahrheitsgehalt dieser Stellen in Zweifel zu ziehen. Tatsächlich sind diese Berichte über Fehler und unmoralisches Verhalten aber Hadithen – vorwiegend aus der „Hadithfabrik“ von