Depuis sa création en 1945 par sept pays arabes, dont la Syrie, la « Ligue des États arabes » a pour objectif d’unifier la « nation arabe », de défendre les intérêts des États membres, de faire face à toute ingérence des puissances dans la région. Elle se voulait aussi une force de proposition et d’impulsion. Mais les divergences sont telles que ses actions et initiatives, même de paix, restent au mieux à effets modestes. Les 22 États membres connaissent des divisions liées aux vicissitudes des relations dues à la nature de leurs systèmes politiques souvent antinomiques.

Deux visions politiques s’affrontent à ce jour. L’une “pro-occidentale” que mène l’axe monarchique, l’autre plus indépendantiste que mène l’axe républicain. Sur la trentaine de sommets organisés entre 1946 et 2011, dont 12 sommets en urgence – où les résolutions les plus importantes concernent la Palestine – on ne relève aucun qui eut un impact signification. Le semblant d’unité apparait plutôt dans l’hostilité à Israël ; quoi que… car, le dossier palestinien n’a pas vraiment unis les membres même lors de l’agression israélienne contre Ghaza, le Qatar, pays hôte du sommet de 2009, avait tenté de mener un camp favorable au Hamas contre l’Autorité palestinienne, ou contre le Liban. Il y a aussi ce « lâchage » de la Syrie qui avait refusé, avec le Liban, d’adhérer à la convention sur le « terrorisme » qui ne distingue pas ceux qui luttent pour la liberté et l’indépendance ; allusion au Hezbollah. Ajoutons la partition du Soudan, le chaos de la Somalie, l’invasion de l’Irak, l’agression du Liban et de la Libye et maintenant les provocations et menaces sur la Syrie. La ligue arabe a été non seulement d’aucune utilité, mais a joué un rôle négatif contre certains de ses propres membres.

La géniale maxime anonyme, (elle n’est pas d’Ibn Khaldoun) qui dit que « les arabes se sont entendus pour ne pas s’entendre » est d’une réalité affligeante qui va plus loin puisque c’est la première fois qu’ils « s’entendent », dans la même année, mais pour… autoriser l’agression par l’Otan de la Libye ; suspendre, sanctionner et menacer la Syrie. Une première dans l’art de se faire châtier par l’organisation censée protéger ses membres. Un grand progrès dans le…ridicule et l’abaissement !

Les peuples arabes savent que cette organisation a perdu son sens pour s’être laissé pervertir en un instrument au service du Grand Capital comme le sont toutes les organisations internationales, y compris droits de l’homme, l’AIEA. La plupart dépendantes des multinationales, leurs donatrices. L’ONU et ses institutions ne servent plus qu’à produire des alibis contre les pays ciblés ; que les ONG et les “journalistes” font dans l’espionnage ; que la CPI s’utilise pour criminaliser les dirigeants indociles ; que le FMI sert à ruiner et gager les pays ; que la presse dites « mainstream » se consacre à la manipulation, la tromperie et le contrôle de l’opinion ; que l’OTAN se réserve pour l’agression et dévastation.

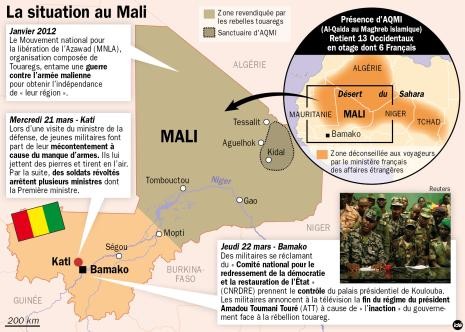

La Ligue arabe ne peut échapper aux plans des lobbies militaro-financiers, de quadrillage du monde pour mieux se servir. Ce sont ces lobbies qui commanditent les guerres, déstabilisent et assassinent et qui, après l’Irak, l’Afghanistan, le Liban et la Libye, bousculent à une confrontation avec l’Iran via la déstabilisation de la Syrie. L’Afrique en paie le prix le plus cher avec l’assassinat de 21 présidents depuis 1960 : de Sylvanus Olympio en 1963 président du Togo à Kadhafi.

Quel autre moyen le plus sûr pour déstabiliser États arabes – qui présentent un danger pour leurs intérêts et Israël ou seraient un mauvais exemple pour les monarchies vassales – que celui de le faire par les arabes eux-mêmes en leur faisant la guerre avec leurs propres citoyens ! La Syrie reste le dernier « verrou » tenace pour sa résistance, dans la région.

L’État le mieux indiqué pour mener la tâche de manipuler et de piéger, tel un cheval de Troie, la Ligue Arabe – après l’éviction par leur peuple des deux renégats Moubarak et Ben Ali – est bien le Qatar en la personne de son Emir – ce vaguemestre des américano-sionistes, celui qui a renversé son père, – et ce, pour sa forte dépendance de l’Occident et ses prédispositions à la félonie. Ce Qatar qui offre aussi des possibilités d’actions militaires proches des zones convoitées. Il est assisté par la Turquie d’Erdogan, un nouveau ottoman, chargée de servir de base pour les actions armées et subversives.

Le choix de la Libye, en priorité, est stratégique – car un carrefour entre le MO, l’Afrique et l’Occident et constituant de plus, une porte moins risquée pour l’Afrique – puis tactique car, pays riche, moins peuplé et moins puissante militairement, dont la chute donnerait d’une part, selon leur vision, un exemple aux autres africains et d’autre part plus d’ardeur pour faire abdiquer la Syrie ; le point d’achoppement des velléités occidentales et sionistes. Cette indomptable Syrie qui fait le poids dans l’équilibre des forces entre l’Occident et l’Asie que représente en particulier la Russie et la Chine, dans ce que l’on appelle l’Organisation de Coopération de Shanghai (OCS) créée à Shanghai en 2001 dont l’Iran est membre.

Ce complot de l’Occident que pilote les EU pour le contrôle des richesses du MO – qui vise à neutraliser ces puissances adverses traditionnelles afin de les rendre plus dépendante et donc plus vulnérables – semble trouver en la Ligue un allié de taille au moment où des États Arabes traversent une période d’incertitudes politiques que l’Occident n’arrive pas à décrypter. D’où ses ingérences pour récupérer ces « révoltes » incontrôlée – qui remettent en cause les fondements et structures politiques archaïques – dans le sens de leurs intérêts sinon en susciter d’autres “contrôlées” pour ensuite intervenir et recomposer dans le sens souhaité en usant des fallacieux prétextes humanistes et nouvellement du grotesque « protection des populations civils ».

Ce masochisme de la Ligue arrange bien certains. Nietzsche disait bien que « si la souffrance, si même la douleur a un sens, il faut bien qu’elle fasse plaisir à quelqu’un… ». Ce sont bien les États-liges du Golfe – organisés dans le « Conseil de Coopération des États arabes du Golfe », qu’appui la Turquie d’Erdogan – qui sont chargés d’engager le bellicisme diplomatique en dictant à la Ligue ce qui doit et ne doit pas se faire. Ces monarchies ont le même rôle dans les institutions et organisations arabes que les sionistes dans les organisations et gouvernements Occidentaux ; celui de déstabiliser tous ceux qui présentent un danger « idéologique » pour les monarchies ou « d’intérêts » pour le Grand Capital. D’où ce “Conseil” des « six pétromonarchies » – qui se voulait un « bloc commercial » – mais qui travaille en fait pour des objectifs sournois ceux de servir les intérêts stratégiques de domination américaine et sioniste. Son influence est telle que ce CCG est surnommé le « bureau politique » de la Ligue puisque les résolutions sont décidées avant même que cette Ligue se réunisse. Avec le CCG, les valeurs sont inversées dans le sens où ce sont les monarchies qui gouvernent leurs contrées sans légitimité, que celle que leur fournit leurs protecteurs occidentaux, qui prennent le bâton de pèlerin pour imposer la démocratie et la liberté aux “républiques”. Et la Turquie ? Les analyses soutiennent qu’Obama aurait répondu favorablement aux dirigeants d’Ankara pour un « sous-impérialisme néo-ottoman » contrôlé par Washington après les inquiétudes de la Turquie de la domination exercée au M.O par Israël et les USA.

Par la Ligue, on se permet désormais d’exclure, de sanctionner et de menacer d’une intervention militaire étrangère, les États membres dont les politiques ne concordent pas avec les vues et objectifs de l’Occident sur la région, dont la prédominance d’Israël, conformément au projet du « Grand Moyen-Orient ».

Ce projet, devant dissoudre le monde musulman dans les fondements euro-atlantistes, consiste à agiter les peuples – en mettant en conflit les arabes musulmans et les chrétiens, les musulmans sunnites et chiites, les ethnies – ensuite, recomposer dans le sens désiré. Le grand capital n’ayant pas de limite géographique ou morale considère le MO, d’un intérêt vital, région qu’il faut dominer par tous les moyens.

Il a été déployé un monstrueux dispositif d’endoctrinement et d’actions psychologiques que mènent des chaînes occidentales et les chaînes des pétromonarchies à savoir Aljazeera et Alarabia. Leur matraquage médiatique, a dérouté les plus éveillés. Beaucoup ont épousé leur cabale médiatique qu’a légitimé la Ligue du méprisant Amr Moussa et que semble aussi accepter l’autre nouveau égyptien Nabil Al-Arabi puisqu’il ne fait que lire ce qu’on lui présente sous l’œil du ministre Qatari des AE. Pour avoir encore plus de légitimité, on instrumentalise même la religion en obtenant la caution de Cheikhs réputés qui décrètent des “fatwas” scélérates rendant licites ou illicites les mêmes choses et comportements en fonction des objectifs attendus du pays concerné, en s’appuyant sur des interprétations orientées et calculées de certains préceptes de l’Islam, allant jusqu’à rendre licite l’agression de la Libye par l’Otan ou bien appelant carrément à un bain de sang en Syrie comme le fait l’imam sunnite syrien al-Aroor, réfugié en Arabie Séoudite. Voilà encore le sinistre Cheikh Al-Qardawi, le protégé de l’Émir du Qatar, l’auteur de la “fatwa” autorisant l’invasion de la Libye et l’assassinat de Kadhafi, qui appelle maintenant les libyens à se… « réconcilier » en même temps qu’il autorise les « opposants syriens » à faire appel à l’Otan. Cet « Islam » là, modulable au gré des intérêts des puissants du moment et de leurs chimères, est bien étrange !

Dans cette offensive, on remarque bien que ce sont les régimes « républicains » réfractaire et pas les monarchies, que l’on vise pour les rendre au moins obéissants en installant des gouvernements composés souvent d’opposants, félons et renégats. Sinon des États dit « Islamiques » sous forme d’« Émirat » en soutenant les tendances rétrogrades, obscurantistes et violentes désignés par « terroristes islamistes », que l’occident dit combattre, mais qu’il instrumentalise, comme en Libye, selon ses désidératas.

Que constate-t-on en Libye ? Un CNT – installé par l’Otan « représentant légitime du peuple libyen » pour réinstaurer un État-lige – dans la panique et aux abois qui n’arrive pas à mettre en place un gouvernement représentatif et qui fait appel, à nouveau, à la « communauté internationale » pour l’aider à se débarrasser des mêmes rebelles qu’il a employés pour installer le chaos. Un CNT qui cherche à récupérer les cadres de l’ancien régime pour reconstituer un état et redémarrer car, impossible de le faire avec l’armée de miliciens ignorants que l’on a utilisé comme chair à canon pour détruire leur pays et qui sombrent dans le désœuvrement. Un CNT qui constate des Benghazi se retourner contre lui par des manifestants réclamant une “nouvelle révolution”. Des libyens, ayant vécu dans la Jamahiriya mieux que beaucoup d’européens par les facilités et les biens gratuits que permet le système, qui se retrouvent maintenant par leur perfidie et prétention en abattant l’ « nourricier », avec rien ; obligés de quémander la nourriture ou de s’adonner au pillage, au racket et au trafic d’armes. Un pays déstructuré et insécurisé aux mains de brigands et d’aventuriers qui ont tué des dizaines de milliers (entre 50 et 70 000 morts) de leurs compatriotes civils que l’Otan a aidés par les bombardements aux missiles. Un pays où le peuple, de tempérament vengeur et tribal, n’oubliera jamais le sang innocent versé et les viols commis. Un pays réduit à la mendicité et aux pénuries y compris d’argent après des dizaines d’années de vie dans l’aisance. Des milices au début “unies” mais qui maintenant, divisées, se font la guerre. Des « révolutionnaires » – composés de prisonniers libérés, de frustrés, d’ignares, de paumés – floués et livrés au pillage et à la rapine, qui deviennent une armée de chômeurs…en arme défiant la nouvelle autorité. Une autorité – composée en grande majorité d’opposants opportunistes et cupides, de tendances contradictoires sous tutelle de la NED/CIA et le MI6 ou de renégats – qui n’arrive pas à s’installer sur le territoire libyen à cause de l’insécurité et des attentats. Un pays ou les libyens, habitués au bien-être et au confort, ne sauront jamais faire le travail réservé à la main-d’œuvre immigrée qui représentait plus de 50 % de la population active ; oui comment demander à 2 millions de libyens de remplacer les 2 millions d’immigrés qui sont partis. Même les candidats à l’émigration ne s’y aventureront plus à cause de l’insécurité et des caisses vides. Un pays où l’on a cédé la place au désordre et où l’on a éveillé l’esprit de résistance avec la naissance d’un « Front de libération ». L’État libyen, avec ses institutions, est bien cassé et pour longtemps ! « Mais que croyaient ces zozos du CNT ? » disait Allain Jules. Citons aussi Félix Houphouët-Boigny « on n’apprécie le vrai bonheur que lorsqu’on l’a perdu ».

Dans le cas de la Libye, le sinistre Bernard-Henri Lévy « philosophe » du mal a été l’entremetteur chargé de faire sous-traiter par la France de Sarkozy cette « opération Libye » et la Ligue arabe servir de caution. Avant même que la Libye ne tombe, ce manipulateur sioniste franco-israélien avait déclaré, à l’Université de Tel Aviv, en compagnie de Tzipi Livni, « si nous réussissons à faire tomber Kadhafi ce sera un message pour Assad ». Par affront, il a déclaré aussi lors d’une réunion du CRIF « c’est en tant que juif que j’ai participé à cette aventure politique, que j’ai contribué à définir des fronts militants, que j’ai contribué à élaborer pour mon pays et pour un autre pays une stratégie et des tactiques ». Malgré les déclarations de Rasmussen, qui avait affirmé le mois d’octobre que l’alliance n’avait « … aucunement l’intention d’intervenir en Syrie… la seule façon d’avancer en Syrie … est de tenir compte des aspirations légitimes du peuple syrien… nous avons pris la responsabilité de l’opération en Libye parce qu’il y avait un mandat clair des Nations unies, car nous avons eu un soutien fort et actif des pays de la région…aucune de ces conditions n’est remplie en Syrie », les choses ont évolué autrement.

Nous revoilà en Syrie avec les mêmes tactiques, mensonges et diversions avec l’usage des mêmes méthodes et procédés ! C’est-à-dire : 1/ Faire infiltrer les manifestations pacifiques et légitimes par des groupes chargés de détourner les revendications en révoltes contre le régime tout en chargeant d’autres embusqués de tirer sur les manifestants ; en même temps on active les cellules dormantes de passer à l’action armée 2/ Imputer les exactions et crimes au « régime » en l’accusant de « tuer des civils qui manifestent pacifiquement ». 3/ Tromper les opinions en leur faisant croire à un régime « dictatorial, répressif » pour le faire condamner par la « communauté internationale ». 4/ Introduite auprès du CS des résolutions pour des sanctions économiques afin d’exacerber les choses et pousser le peuple à se révolter contre ses dirigeants. 5/ Faire admettre des « enquêteurs » et autres « journalistes » qui sont en fait des espions de guerre. 6/ Intervenir militairement sous des prétextes « humanitaire » en particulier « protéger les civils ». 7/ Instaurer le chaos. 8/ Créer une entité, en lieu et place du gouvernement composée d’éléments à leur solde 9/ Traduire les responsables comme des criminels de guerre devant un Tribunal Spécial.

Cependant, le monde a bien changé dans les relations politiques et économiques, dans les rapports de force avec la fin de la “guerre froide”, dans les alliances stratégiques à cause surtout des crises et des contradictions que génère le capitalisme actuel fait de spéculations et d’injustices suscitant des conflits d’intérêts voire d’existence.

C’est donc sans compter, cette fois, sur le double véto russe et chinois qui ne veulent pas s’y faire prendre comme en Libye où l’Otan a bafoué toutes les règles. Le même scénario en Syrie a d’autres portées autrement plus stratégiques car, il vise à resserrer le “noeud coulant” autour du puissant Iran en mettant en place, en Syrie, un « pont littoral » qui puisse servir à attaquer ce pays et par conséquent affaiblir irréversiblement la Russie et la Chine.

Il ne restait que « Ligue arabe » pour réaliser ce qu’ils n’ont pas pu faire passer par le C.S et faire, par cette pression, abdiquer ces deux puissances. L’objectif étant, par la Ligue, de mettre « au pas » tous les régimes présentant des obstacles à la politique hégémonique des lobbies financiers et industriels que soutiennent, par vassalité, les monarchies arabes et par nature, Israël. La Syrie étant l’obstacle primordial, il s’agit, pour l’Otan, de prêter main forte, par la Turquie, à l’insurrection armée – intégrée préalablement par des islamistes “djihadistes” et des mercenaires – en l’entrainant, l’armant puis en répandant de grandes quantités d’armes variées dans les régions en trouble, comme du temps de la guerre soviéto-afghane, plutôt que de réitérer la méthode désastreuse des frappes comme en Libye.

Le coup d’envoi a été donné à Deraa pour s’étendre à Homs puis à d’autres villes. On tend des embuscades aux éléments de l’armée et des services de sécurité tuant plus de 1100 ; leur armement est acheminé depuis la Turquie et la frontière libanaise. On assassine des centaines citoyens, des responsables civils, des intellectuels, des médecins, des commerçants (on parle de 5000). On viole les domiciles et kidnappe des citoyens pour des rançons. On détruit, incendie et sabote les infrastructures économiques comme les gazoducs, les usines et les voies ferrées. On réserve des camps sur le territoire Turc pour accueillir des mercenaires, essentiellement des « rats » libyens, dont-on a plus quoi faire, puis ériger avec quelques apostats et révoltés une « armée syrienne libre ». On “décrète”, avec menace, une grève générale qui a échoué. On lance un appel au boycottage des élections locales, issues des nouvelles réformes, qui a aussi échoué au regard de la participation. On s’acharne à en faire une « guerre civile » pour neutraliser ce pays et laisser faire les prédateurs. Le Qatar s’engage une nouvelle fois à tout financer. On requiert, via la Ligue, des sanctions économiques.

Des sanctions qui semblent n’avoir aucune chance de faire plier le gouvernement syrien. D’abord, parce que 95 % des avoirs ont été rapatriés et en

plus, ce sont les États arabes de la région qui pâtiront d’un éventuel boycott des produits syriens dont-ils dépendent en grande partie, mais qui ne représentent qu’une modeste proportion des exportations de la Syrie. La grande part est absorbée par l’Irak, qui refuse les sanctions et la Turquie qui se retrouve en situation de « l’arroseur arrosé » puisque les Turcs grognent déjà contre leur gouvernement pour les effets néfastes qu’ils commencent à sentir mais, le verdict vient de l’Iran qui annonce un important accord de libre-échange et d’investissements avec la Syrie ! Quant à l’embargo sur son pétrole, il a déjà trouvé preneur.

Ils continueront jusqu’à à la dernière carte à accuser trompeusement le gouvernement syrien des pires atrocités que commettent en réalité des terroristes à leur solde – selon les témoignages de journalistes indépendants, des délégations ayant visité la Syrie ou le reportage récent d’une agence américaine – contrairement aux soldats qui ripostent pour se protéger ou empêcher le chaos. Ils continueront avec leur “merdias” à travestir la réalité, à fabriquer des faits made Aljazeera, Alarabia, BBC arabic et France 24. Cependant, au regard de l’évolution des choses et devant le haut niveau de conscience des syriens, la puissance et l’expérience de leur armée qui n’a pas encore utilisé ses moyens et capacités, la modestie et la persévérance de leur président, les manifestations de masses contre l’ingérence et les décisions de la Ligue, le complot semble en phase d’échec.

Malgré cela, le gouvernement Syriens, a pris plusieurs mesures pour reformer les institutions et le régime dans le sens d’une démocratisation effective avec projet d’une nouvelle. Il s’emploie à s’ouvrir aux tendances par le dialogue, y compris avec « l’opposition à l’étranger », en leur proposant de régler pacifiquement la crise entre syriens « en Syrie » avec toutes les garanties, en acceptant même des médiateurs. Malheureusement, c’est sans compter sur les « décideurs/brigands », ceux qui jouent les grandes marionnettes, qui bloquent tout ce qui permet l’apaisement en incitant l’opposition à renoncer au dialogue et en avisant les groupes armés de ne pas déposer les armes.

Voilà que la Russie sonne le tocsin en mettant en garde contre toute velléité de déstabilisation ou de guerre contre la Syrie en même temps qu’elle annonce s’opposer à toute ingérence étrangère dans les affaires de ce pays. Elle y met les moyens en dépêchant son armada dissuasif dans la région afin « d’empêcher une guerre aux conséquences graves ». Lavrov met aussi en garde contre le langage par « les avertissements et les menaces » à l’endroit de la Syrie après avoir dénoncé, devant le conseil de l’OSCE, l’utilisation des résolutions des Nations Unies visant à « mettre fin illégalement » à des conflits et cette pratique du « deux poids, deux mesures ». La Chine prend le relais en annonçant s’opposer aux ingérences tout en déclarant soutenir toutes les initiatives qui permettent d’instaurer le calme et la stabilité. L’Inde fait de même à Moscou lors de la visite du PM Manmohan Singh. Mieux, selon Farsnews qui se réfère au bulletin du département d’État US (Europian Union Times), le président chinois aurait averti, devant son homologue russe et son premier ministre, que la seule voie permettant de stopper une intervention militaire américaine contre l’Iran est une action armée. « On fera la guerre même si cela déclenche la troisième guerre mondiale » aurait prévenu Jin Tao. Cet aboutissement est déjà signalé, en novembre, par le chef d’État-major général russe Nikolaï Makarov, lors de son intervention devant la Chambre civile (Kremlin). L’agence “Novosti” avait rapporté que ce général, en se référant à l’expansion de l’Otan en Europe de l’Est avec le bouclier antimissiles et le contexte post-Libye de pression sur la Syrie et l’Iran, avait lancé un message sans équivoque en affirmant qu’« il devient évident que le risque d’implication de la Russie dans des conflits locaux a augmenté… sous certaines conditions, les conflits régionaux risquent de dégénérer en conflits d’envergure avec un possible emploi d’armes nucléaires ». La messe donc est dite !

Tant que les Russes et les Chinois soutiendront la Syrie, les va-t-en-guerre n’auront aucune chance de réussir.

Au même moment les iraniens font atterrir, par une prouesse technologique hors-pair le drone-espion américain furtif de type RQ170 le plus sophistiqué ; sa destruction comme prévu en cas d’interception n’a pas réussi. Les USA, sonnés par ce revers, perdent ainsi un atout technologique majeur en le mettant “gratuitement” à disposition de l’Iran. Ils échouent aussi dans cet essai débile de création d’une « ambassade virtuelle » au « service » des iraniens pour mieux, en fait, espionner et manipuler.

Mais l’impérialisme n’est pas encore épuisé ses forces.

Il essayera encore de réintroduire le dossier syrien auprès du CS via encore…la Ligue “arabe” avec d’autres ruses comme nous le constatons avec la sortie “émouvante” de l’ambassadeur de France à l’Onu, Gérard Araud – qui ressemble au “chant du cygne” – qui ose qualifier la situation syrienne d’ « épouvantable et d’effroyable » pour les 5000 morts en majorité tués par les groupes armés que la France soutient ; oubliant que son pays a participé aux massacres par l’OTAN des libyens et l’assassinat programmé de Kadhafi. Cette France suiviste sarkozienne divisée, stigmatisée qui redonne une image colonialiste par ses ingérences et actions de déstabilisation des États africain. Cette France qui sombre dans la récession ; qui paie des rançons aux terroristes. On s’essaye, par revanche, à déstabiliser, cette fois, la… Russie, en sautant sur l’occasion des élections, pour exacerber les mécontentements dus à quelques cas de fraudes. C’est la Clinton qui donne le coup d’envoi avec son « aspirations du peuple russe à espérer un avenir meilleur » à propos des manifestations. Mais le ministre russe de l’Intérieur Nourgaliev averti qu’il mettrait fin à « toute tentative d’organiser un événement non autorisé ». Vladimir Poutine lance – à propos des ONG russes, en particulier “Golos” que finance la NED et l’UE pour le recrutement de ses membres à travers les services Suédois – devant ses partisans « premièrement, Judas n’est pas le personnage biblique le plus respecté chez les Russes [en référence à la trahison], deuxièmement, ils feraient mieux d’utiliser cet argent pour payer leur déficit public et d’arrêter de dépenser de l’argent pour des politiques étrangères coûteuses et inefficaces ». La « Ligue arabes » osera-t-elle ce genre de réplique ? Qu’avaient répondu les arabes lorsque Martin Van Crevel, historien militaire israélien avait souhaité la « déportation collective » des palestiniens dans une interview ? Qu’elle est la répondre leur « Ligue », à la récente ineptie de l’idiot « utile » Newt Gingrich ex “speaker” de la Chambre des représentants, qui brigue l’investiture républicaine, à la déclaration, sur la chaine “The Jewish Channel”, par une inversion accusatoire, que le peuple palestinien est une « invention » et que les palestiniens « … faisaient partie de l’empire ottoman avant la création d’Israël » ? (Ce sot est diplômé en… histoire). Aux dernières nouvelles, il y aurait divergence entre les membres de la Ligue sur les mécanismes appropriés pour régler cette crise syrienne. Le Qatar, l’Arabie Saoudite, les Emirat, le Bahreïn, le Koweït, la Tunisie et le CNT Libyen sont pour l’introduction du dossier auprès du CS alors que l’ Égypte, l’Algérie, le Liban, l’Irak, Oman et le Soudan sont pour le dialogue entre syriens.

Enfin, l’Occident est bien au bord d’une crise majeure, conséquence de son capitalisme sauvage sans limites, qui martyrise les populations de la planète, où l’homme est une marchandise. On observe une tendance vers un effondrement spectaculaire de son économie sous les poids de ses défaites militaires et de ses crises économiques internes, mais aussi de son immoralité. Le monde de la finance se retrouvant agonisant, il se débat, telle une bête blessée, en voulant s’en sortie au détriment des autres États en piétinent toutes les règles internationales et morales. Il veut faire payer, comme toujours, aux peuples les crises qu’il engendre.

Ce qui se déroule dans le monde arabe a été planifié par les américano-sionistes, comme 1ère étape, pour trouver une sortie de crise. Pour eux, il n’y a de morale qui n’intervienne que pour l’exiger aux autres. Ce sont des criminels qui s’habillent d’oripeaux élogieux – droits de l’homme, liberté et démocratie – pour faire croire en une quelconque vertu afin de mieux tromper les consciences et spolier. Leurs prétentions les aveugles au point où ils perdent la raison. « On passe sa vie à vouloir atteindre un objectif, à courir après des rêves, à croire qu’obtenir ce que l’on veut nous ouvrira les portes du bonheur. Mais ça ne se passe pas ainsi. C’est le chemin qui fait l’existence, pas l’aboutissement… dit Jorge Molist (Le Rubis des Templiers).

Pourtant, la déstabilisation d’une région entière, carrefour de trois continents, aurait des retombées catastrophiques sur tous les pays. Ce n’est rentable à personne ; ni aux pays de la région, ni aux EU, ni à l’Europe, ni à la Russie, ni à la Chine encore moins à Israël que l’on croit protéger. Un embrasement sera fatal aussi aux monarchies. Les islamistes salafistes ou les terroristes d’Al Qaida ou autres mercenaires que l’on croit dompter et instrumentaliser par l’argent, qu’appui des Cheikhs opportunistes, ne seront d’aucun secours dans le cas d’une guerre totale.

Faudra-t-il une autre guerre mondiale à cause de quelques trusts et cartels puissants qui s’évertuant à vouloir dominer le monde par la force ? L’humanité ne donne pas d’exemple de réussite de cette nature.

Quand on sait que les monarchies du golfe, qui dirigent cette Ligue, sont déjà sous la protection des EU, de quelle autre mission est chargée alors cette Ligue si ce n’est de contrôler les faits et gestes des pays membres récalcitrants pour dominer cette région. Surprise de dernière minute, la Russie introduit un projet de résolution, qui s’apparente à un contre-pied aux occidentaux, condamnant les violences des « deux côtés » ainsi que les ingérences, exigeant l’apaisement et le dialogue entre et les syriens. Ce projet, qui ne demande pas l’éviction de Bachar, a mis dans l’embarra les occidentaux qui veulent apporter des “modifications” mais aussi la Ligue « arabe » qui a …reporté ses « décisions » certainement, par subordination, pour voir vers où penche le rapport de force.

À notre sens, certains pays arabes doivent en urgence se retirer de cette funeste « Ligue », qui devient plus un attrape-nigaud qu’un bouclier de protection. Il leur sera plus avantageux, à l’avenir, de se regrouper en pôles régionaux d’intérêts communs, sur des bases réelles c’est-à-dire économiques, culturelles et de défense que sur une base « identitaire » chimérique, contre-productive comme on le constate.

Il est certain qu’avec l’axe Russie-Chine-Iran-Syrie-Liban, qu’appuieront les autres États du « BRICS », les complots en cours ou en gestation seront un coup d’épée dans l’eau et qu’en lieu et place du « Grand Moyen Orient » planifié par les EU, c’est un « Nouveau Moyen Orient », à l’opposé de celui espéré, qui surgira pour un autre ordre mondial basé sur d’autres règles, d’autres principes !

Amar DJERRAD

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Lente en van de Egyptische politiek. Ook al Qaradawi heeft heel wat aan Al Jazeera te danken en aan de media-aandacht die hij erdoor kreeg. Wekelijks was hij te zien en te horen in een uitzending “de sjaria en het leven”, waar hij vragen beantwoordde van toehoorders uit de ganse islamitische wereld.

Lente en van de Egyptische politiek. Ook al Qaradawi heeft heel wat aan Al Jazeera te danken en aan de media-aandacht die hij erdoor kreeg. Wekelijks was hij te zien en te horen in een uitzending “de sjaria en het leven”, waar hij vragen beantwoordde van toehoorders uit de ganse islamitische wereld. Neen, daarmee houdt het niet op, want ook in het conflict in Aghanistan is Qatar actief. Eerste zichtbare resultaat hiervan: de radikaal-islamitische Taliban opende in januari een officiële vertegenwoordiging in het emiraat. Via dit kantoor zouden vredesgesprekken op gang komen. En in die vredesgesprekken zouden ook de VSA en de EU kunnen worden betrokken. Kaboel houdt de boot voorlopig af en heeft aangedrongen op bilaterale gesprekken …met Qatar.

Neen, daarmee houdt het niet op, want ook in het conflict in Aghanistan is Qatar actief. Eerste zichtbare resultaat hiervan: de radikaal-islamitische Taliban opende in januari een officiële vertegenwoordiging in het emiraat. Via dit kantoor zouden vredesgesprekken op gang komen. En in die vredesgesprekken zouden ook de VSA en de EU kunnen worden betrokken. Kaboel houdt de boot voorlopig af en heeft aangedrongen op bilaterale gesprekken …met Qatar.