[1]Author’s Note:

This is the text of my talk at the fourth meeting of the Scandza Forum in Copenhagen, Denmark, on September 15, 2018. In my previous Scandza Forum talk [2], I argued that we need to craft ethnonationalist messages for all white groups, even Trekkies. This is my Epistle to the Trekkies. I want to thank everybody who was there, and everybody who made the Forum possible.

The idea of creating a utopian society through scientific and technological progress goes back to such founders of modern philosophy as Bacon and Descartes, although the idea was already hinted at by Machiavelli. But today, most people’s visions of technological utopia are derived from science fiction. With the notable exception of Frank Herbert’s Dune series [3], science fiction tends to identify progress with political liberalism and globalism. Just think of Star Trek, in which the liberal, multi-racial Federation is constantly battling against perennial evils like nationalism and eugenics. Thus it is worth asking: Is ethnic nationalism—which is illiberal and anti-globalist—compatible with technological utopianism or not?

My view is that technological utopianism is not only compatible with ethnic nationalism but also that liberalism and globalization undermine technological progress, and that the ethnostate is actually the ideal incubator for mankind’s technological apotheosis.

Before arguing these points, however, I need to say a bit about what technological utopianism entails and why people think it is a natural fit with globalization. The word utopia literally means nowhere and designates a society that cannot be realized. But the progress of science and technology are all about the conquest of nature, i.e., the expansion of man’s power and reach, so that utopia becomes attainable. Specific ambitions of scientific utopianism include the abolition of material scarcity, the exploration and settlement of the galaxy, the prolongation of human life, and the upward evolution of the human species.

It is natural to think that scientific and technological progress go hand in hand with globalization. Reality is one, therefore the science that understands reality and the technology that manipulates it must be one as well. Science and technology speak a universal language. They are cumulative collaborative enterprises that can mobilize the contributions of the best people from across the globe. So it seems reasonable that the road to technological utopia can only be impeded by national borders. I shall offer three arguments why this is not so.

1. Globalization vs. Innovation

I define globalization as breaking down barriers to sameness: the same market, the same culture, the same form of government, the same way of life—what Alexandre Kojève called the “universal homogeneous state.”

As Peter Thiel argues persuasively in Zero to One [4], globalization and technological innovation are actually two very different modes of progress. Technological innovation creates something new. Globalization merely copies new things and spreads them around. Thiel argues, furthermore, that globalization without technological innovation is not sustainable. For instance, it is simply not possible for China and India to consume as much fossil fuel as the First World countries, but that is entailed by globalization within the present technological context. In the short run, this sort of globalization will have catastrophic environmental effects. In the long run, it will hasten the day when our present form of civilization collapses when fossil fuels are exhausted. To stave off this apocalypse, we need new innovations, particularly in the area of energy.

As Peter Thiel argues persuasively in Zero to One [4], globalization and technological innovation are actually two very different modes of progress. Technological innovation creates something new. Globalization merely copies new things and spreads them around. Thiel argues, furthermore, that globalization without technological innovation is not sustainable. For instance, it is simply not possible for China and India to consume as much fossil fuel as the First World countries, but that is entailed by globalization within the present technological context. In the short run, this sort of globalization will have catastrophic environmental effects. In the long run, it will hasten the day when our present form of civilization collapses when fossil fuels are exhausted. To stave off this apocalypse, we need new innovations, particularly in the area of energy.

The most important technological innovations of the twentieth century are arguably splitting the atom and the conquest of space. Neither was accomplished by private enterprise spurred by consumer demand in a global liberal-democratic society. Instead, they were created by rival governments locked in hot and cold warfare: first the United States and its Allies against the Axis powers in World War II, then the United States and the capitalist West versus the Soviet Bloc until the collapse of Communism in 1989–1991.

Indeed, one can argue that the rivalry between capitalism and communism began to lose its technological dynamism because of the statesmanship of Richard Nixon, who began détente with the USSR with the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks in 1969, then went to China in 1971, lessening the threat that the Communist powers would recoalesce into a single bloc. Détente ended with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative could have spurred major technological advances, but merely threatening it was enough to persuade Gorbachev to seek a political solution. So the ideal situation for spurring technological growth is political rivalry without political resolution, thereby necessitating immense expenditures on research and development to gain technological advantages.

Since the collapse of Communism and the rise of a unipolar liberal-democratic world order, however, the driving force of technological change has been consumer demand. Atomic energy and sending men into space have been pretty much abandoned, and technological progress has been primarily channeled into information technology, which has made some of us more productive but for the most part just allows us to amuse ourselves with smartphones as society declines around us.

But we are not going to be able to Tweet ourselves out of looming environmental crises and Malthusian traps. Only fundamental innovations in energy technology will do the trick. And only the state, which can command enormous resources and unite a society around a common purpose, has a record of accomplishment in this area.

Of course none of the parties to the great conflicts that spurred technological growth were ethnonationalists in the strict sense, not even the Axis powers. Indeed, liberal democracy and communism were merely rival visions of global society. But when rival visions of globalization are slugging it out for power, that means that the globe is divided among a plurality of different political actors.

Pluralism and rivalry have spurred states to the greatest technological advances in history. Globalization, pacification, and liberalism have not only halted progress but have bred complacency in the face of potential global disasters. A global marketplace will never take mankind to the stars. It will simply distract us until civilization collapses and the Earth becomes a scorched boneyard.

2. Innovation vs. Cost-Cutting

In economics, productivity is defined as a mathematical formula: outputs divided by inputs, i.e., the cost per widget. Mathematically speaking, you can increase productivity either by making labor more productive, chiefly through technological innovation, or simply by cutting costs.

Most of the productivity gains that come from economic globalization are a matter of cost-cutting, primarily cutting the costs of labor. The Third World has a vast supply of cheap labor. Economic globalization allows the free movement of labor and capital. Businesses can cut labor costs by moving factories overseas or by importing new workers to drive down wages at home.

Historically speaking, the greatest economic spur to technological innovation has been high labor costs. The way to raise labor costs is to end economic globalization [5], by cutting off immigration and by putting high tariffs on foreign manufactured goods. In short, we need economic nationalism. Indeed, only economic nationalism can lead to a post-scarcity economy.

What exactly is a “post-scarcity economy,” and how can we get there from here? First of all, not all forms of scarcity can be abolished. Unique and handcrafted items will always be scarce. There will only be one Mona Lisa. Scarcity can only be abolished with identical, mass-produced items. Second, the cost of these items will only approach zero in terms of labor. Basically, we will arrive at a post-scarcity economy when machines put everyone involved in mass production out of work. But the machines, raw materials, and energy used in production will still have some costs. Thus the post-scarcity economy will arrive through innovation in robotics and energy production. The best image of a post-scarcity world is the “replicator” in Star Trek, which can change the atomic structure of basic inputs to materialize things out of thin air.

Of course workers who are replaced by machines can’t be allowed to starve. The products of machines have to be consumed by someone. Production can be automated but consumption cannot. It would be an absurdist dystopia if mechanization led to the starvation of workers, so consumption had to be automated as well. One set of robots would produce things, then another set of robots would consume them and add zeroes to the bank balances of a few lonely plutocrats.

Of course workers who are replaced by machines can’t be allowed to starve. The products of machines have to be consumed by someone. Production can be automated but consumption cannot. It would be an absurdist dystopia if mechanization led to the starvation of workers, so consumption had to be automated as well. One set of robots would produce things, then another set of robots would consume them and add zeroes to the bank balances of a few lonely plutocrats.

To make the post-scarcity economy work, we need to ensure that people can afford to buy its products. There are two basic ways this can be done.

First, the productivity gains of capital have to be shared with the workers, through rising wages or shrinking work weeks. When workers are eliminated entirely, they need to receive generous pensions.

Second, every economic system requires a medium of exchange. Under the present system, the state gives private banks the ability to create money and charge interest on its use. The state also provides a whole range of direct payments to individuals: welfare, old-age pensions, etc. A universal basic income [6] is a direct government payment to all citizens that is sufficient to ensure basic survival in a First-World country. Such an income would allow the state to ensure economic liquidity, so that every product has a buyer, while eliminating two very costly middlemen: banks and social welfare bureaucracies.

All of this sounds pretty far out. But it is only unattainable in the present globalized system, in which cost-cutting is turning high-tech, First World industrial economies into low-tech Third World cheap-labor plantation economies. Only economic nationalism can spur the technological innovations necessary to create a post-scarcity economy by raising labor costs, both through immigration controls and tariff walls against cheap foreign manufactured goods.

3. Ethnonationalism & Science

So far we have established that scientific and technological progress are undermined by globalization and encouraged by nationalist economic policies and the rivalries between nations and civilizational blocs. But we need a more specific argument to establish that ethnonationalism is especially in harmony with scientific and technological progress.

My first premise is: No form of government is fully compatible with scientific and technological progress if it is founded on dogmas that are contrary to fact. For instance, the republic of Oceania might have a population of intelligent and industrious people, an excellent educational system, first rate infrastructure, and a booming economy. But if the state religion of Oceania mandates that the Earth is flat and lies at the center of the universe, Oceania is not going to take us to the stars.

My second premise is: The advocacy of racially and ethnically diverse societies—regardless of whether they have liberal or conservative regimes—is premised on the denial of political experience and the science of human biological diversity.

The history of human societies offers abundant evidence that putting multiple ethnic groups under the same political system is a recipe for otherwise avoidable ethnic tensions and conflicts. Furthermore, science indicates that the most important factors for scientific and technological advancement—intelligence and creativity—are primarily genetic, and they are not equally distributed among the races. Finally, Genetic Similarity Theory predicts that the most harmonious and happy societies will be the most genetically homogeneous, with social conflict increasing with genetic diversity.

Denying these facts is anti-scientific in two ways. First and most obviously, it is simply the refusal to look at objective facts that contradict the dogma that diversity improves society. Second, basing a society on this dogma undermines the genetic and social conditions necessary for progress and innovation, for instance by lowering the average IQ and creating greater social conflict. Other things being equal, these factors will make a society less likely to foster scientific and technological innovation.

My third premise is: Ethnonationalism is based on both political experience and the science of human biological diversity—and does not deny any other facts. Therefore, ethnonationalism is more compatible with scientific and technological progress than are racially and ethnically diverse societies—other things being equal.

Of course some research and development projects require so much money and expertise that they can only be undertaken by large countries like the United States, China, India, or Russia. Although we can predict with confidence that all of these societies would improve their research and development records if they were more racially and culturally homogeneous, even in their present states they can accomplish things that small, homogeneous ethnostates simply cannot dream of.

For instance, if a country of two million people like Slovenia were to adopt ethnonationalism, it would probably outperform a more diverse society with the same size and resources in research and development. But it would not be able to colonize Mars. However, just as small countries can defend themselves from big countries by creating alliances, small states can work together on scientific and technological projects too big to undertake on their own. No alliance is stronger than its weakest member. Since diversity is a weakness and homogeneity is a strength, we can predict that cooperative research and development efforts among ethnostates will probably be more fruitful than those among diverse societies.

Now someone might object that one can improve upon the ethnostate by taking in only high-IQ immigrants from races. Somehow Americans went to the Moon without importing Asians and Indians. Such people are being imported today for two reasons. First, importing foreign brains allows us to evade problems with producing our own, namely, dysgenic fertility and the collapse of American STEM education, largely due to political correctness, i.e., racial integration and the denial of biological intelligence differences. Second, the productivity gains attributed to diversity in technology are simply due to cost-cutting. But the real answer is: The Internet allows whites to collaborate with the best scientists around the world. But we don’t need to live with them.

To sum up: The idea that technological utopia will go hand-in-hand with the emergence of a global homogeneous society is false. The greatest advances in technology were spurred by the rivalries of hostile political powers, and with the emergence of a unipolar world, technological development has been flagging.

The idea that technological utopia goes hand-in-hand with liberal democracy is false. Liberalism from its very inception has been opposed to the idea that there is a common good of society. Liberalism is all about empowering individuals to pursue private aims and advantages. It denies that the common good exists; or, if the common good exists, liberalism denies that it is knowable; or if the common good exists and is knowable, liberalism denies that it can be pursued by the state, but instead will be brought about by an invisible hand if we just allow private individuals to go about their business.

The only thing that can bring liberal democrats together to pursue great common aims is the threat of war. This is what sent Americans to the Moon. America’s greatest technological achievements were fostered by the government, not private enterprise, and in times of hot and cold war, not peace. Since the end of the Cold War, however, victory has defeated us. America is no longer a serious country.

The solution, though, is not to go back to war, but to junk liberalism and return to the classical idea that there is a common good that can and must be pursued by the state. A liberal democracy can only be a serious country if someone like the Russians threatens to nuke them every minute of the day. Normal men and normal societies pursue the common good, because once one is convinced something really is good, one needs no additional reason to pursue it. But if you need some extra incentives, consider the environmental devastation and civilizational collapse that await us as the fossil fuel economy continues to expand like an algae bloom to its global limits. That should concentrate the mind wonderfully.

The idea that technological utopia will go hand-in-hand with global capitalism is false. Globalization has undermined technological innovation by allowing businesses to raise profits merely by cutting costs. The greatest advances in manufacturing technology have been spurred by high labor costs, which are products of a strong labor movement, closed borders, and protectionism.

Finally, the idea that technological utopianism will go hand-in-hand with racially and ethnically diverse societies is false. This is where ethnonationalism proves its superiority. Diversity promotes social conflict and removes barriers to dysgenic breeding. The global average IQ is too low to create a technological utopia. Global race-mixing will make Europeans more like the global average. Therefore, it will extinguish all dreams of progress. Ethnonationalists, however, are actually willing to replace dysgenic reproductive trends with eugenic ones, to ensure that every future generation has more geniuses, including scientific ones. And if you need an extra incentive, consider the fact that China is pursuing eugenics while in the West it is fashionable to adopt Haitian babies. Ethnonationalism, moreover, promotes social harmony and cohesion, which make possible coordinated efforts toward common goals.

What sort of society will conquer scarcity, conquer death, and settle the cosmos? A society that practices economic nationalism to encourage automation. A homogeneous, high-IQ society with eugenic rather than dysgenic reproductive trends. A harmonious, cohesive, high-trust society that can work together on common projects. An illiberal society that is willing to mobilize its people and resources to achieve great common aims. In short, if liberal democracy and global capitalism are returning us to the mud, it is ethnonationalism that will take us to the stars.

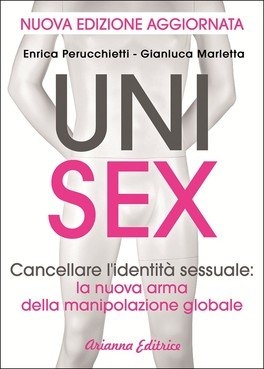

Esiste un libro “speciale” in Italia dal titolo UNISEX e con sottotitolo “Cancellare l’identità sessuale: la nuova arma della manipolazione globale” pubblicato da Arianna Editrice. Gli autori sono la giornalista Enrica Perucchietti e lo scrittore Gianluca Marletta.

Esiste un libro “speciale” in Italia dal titolo UNISEX e con sottotitolo “Cancellare l’identità sessuale: la nuova arma della manipolazione globale” pubblicato da Arianna Editrice. Gli autori sono la giornalista Enrica Perucchietti e lo scrittore Gianluca Marletta.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Soixante-dix ans après sa mort, Georges Bernanos fait toujours l’objet d’interprétations intéressées. Certaines se focalisent sur le romancier et ignorent l’essayiste et le polémiste. D’autres, au contraire, valorisent le pamphlétaire et écartent son œuvre romanesque. Thomas Renaud a le mérite de montrer que ces deux facettes forment un seul ensemble de manière irrécupérable. « Complexe et torturé, dans la mesure où il n’a jamais voulu faire taire les appels de son âme, Bernanos a porté avec lui les violents paradoxes de la nature humaine, sans que ne soient jamais trahies ses plus profondes convictions. Catholique, royaliste, anti-démocrate, anti-clérical et anti-moderne, ennemi des bourgeois et partisan des petits jusqu’à la mauvaise foi, il demeura tout cela à la fois, depuis son adolescence jusqu’à son dernier souffle. D’un côté, les “ droitards ” se fourvoient en dénonçant en lui un traître passé à gauche, de l’autre, certains néo-bernanosiens se trompent également en occultant l’admiratif disciple de Drumont, le militant de rue de l’Action française, le solide soldat des tranchées et le chrétien intégral (p. 114). »

Soixante-dix ans après sa mort, Georges Bernanos fait toujours l’objet d’interprétations intéressées. Certaines se focalisent sur le romancier et ignorent l’essayiste et le polémiste. D’autres, au contraire, valorisent le pamphlétaire et écartent son œuvre romanesque. Thomas Renaud a le mérite de montrer que ces deux facettes forment un seul ensemble de manière irrécupérable. « Complexe et torturé, dans la mesure où il n’a jamais voulu faire taire les appels de son âme, Bernanos a porté avec lui les violents paradoxes de la nature humaine, sans que ne soient jamais trahies ses plus profondes convictions. Catholique, royaliste, anti-démocrate, anti-clérical et anti-moderne, ennemi des bourgeois et partisan des petits jusqu’à la mauvaise foi, il demeura tout cela à la fois, depuis son adolescence jusqu’à son dernier souffle. D’un côté, les “ droitards ” se fourvoient en dénonçant en lui un traître passé à gauche, de l’autre, certains néo-bernanosiens se trompent également en occultant l’admiratif disciple de Drumont, le militant de rue de l’Action française, le solide soldat des tranchées et le chrétien intégral (p. 114). » Du fait des impératifs du volume, l’auteur s’intéresse à la vie de Georges Bernanos, quitte à reléguer au second plan sa vision politique. Elle demeure cependant bien présente pour expliquer les prises de position virulentes d’un fervent chrétien inquiet de l’avenir de la foi et des fidèles. Attention au contre-sens ! Bernanos se moque du sort des États modernes. Ce catholique a compris que la modernité est en perdition, elle est la perdition et correspond à la Chute de l’Homme adamique. D’où la démarche de son biographe. « Il nous semblait préférable de présenter aux lecteurs qui le connaissaient mal un Bernanos vivant, sans l’habituelle hémiplégie intellectuelle des lecteurs “ de droite ” et “ de gauche ”. Sébastien Lapaque a fait beaucoup pour rendre ce Bernanos “ en bloc ” que trop de critiques avaient divisé. Cette petite biographie doit ouvrir largement sur l’œuvre et permettre une belle amitié avec un auteur particulièrement attachant, qui n’a jamais souhaité jouer la comédie (1). »

Du fait des impératifs du volume, l’auteur s’intéresse à la vie de Georges Bernanos, quitte à reléguer au second plan sa vision politique. Elle demeure cependant bien présente pour expliquer les prises de position virulentes d’un fervent chrétien inquiet de l’avenir de la foi et des fidèles. Attention au contre-sens ! Bernanos se moque du sort des États modernes. Ce catholique a compris que la modernité est en perdition, elle est la perdition et correspond à la Chute de l’Homme adamique. D’où la démarche de son biographe. « Il nous semblait préférable de présenter aux lecteurs qui le connaissaient mal un Bernanos vivant, sans l’habituelle hémiplégie intellectuelle des lecteurs “ de droite ” et “ de gauche ”. Sébastien Lapaque a fait beaucoup pour rendre ce Bernanos “ en bloc ” que trop de critiques avaient divisé. Cette petite biographie doit ouvrir largement sur l’œuvre et permettre une belle amitié avec un auteur particulièrement attachant, qui n’a jamais souhaité jouer la comédie (1). »

Les mystères de l’Eurasie sont désormais disponibles en français grâce aux excellentes éditions Ars Magna dans la collection « Heartland » (2018, 415 p. 30 €). L’ouvrage accorde une très large place au symbolisme, à l’étude des runes russes, à l’eschatologie chrétienne orthodoxe et à l’ésotérisme. Cependant, politique et géopolitique ne sont jamais loin chez Alexandre Douguine qui, dès cette époque, rejoint un néo-eurasisme balbutiant. Ne voit-il pas en « Gengis Khan, le restaurateur de l’Empire eurasien (p. 142) » ? En se fondant sur les recherches des traditionalistes Guénon, Evola et Georgel, il explique que « la Sibérie est toujours restée cachée, inconnue et mystérieuse à travers l’histoire, comme si elle était sous la protection d’une force spéciale du destin, d’un archange inconnu (p. 134) ».

Les mystères de l’Eurasie sont désormais disponibles en français grâce aux excellentes éditions Ars Magna dans la collection « Heartland » (2018, 415 p. 30 €). L’ouvrage accorde une très large place au symbolisme, à l’étude des runes russes, à l’eschatologie chrétienne orthodoxe et à l’ésotérisme. Cependant, politique et géopolitique ne sont jamais loin chez Alexandre Douguine qui, dès cette époque, rejoint un néo-eurasisme balbutiant. Ne voit-il pas en « Gengis Khan, le restaurateur de l’Empire eurasien (p. 142) » ? En se fondant sur les recherches des traditionalistes Guénon, Evola et Georgel, il explique que « la Sibérie est toujours restée cachée, inconnue et mystérieuse à travers l’histoire, comme si elle était sous la protection d’une force spéciale du destin, d’un archange inconnu (p. 134) ».

Negli anni Sessanta, in qualità di giovanissimo militante della Giovane Europa, l’organizzazione da lui diretta, ebbi modo di vederlo diverse volte. Lo conobbi a Parma, nel 1964, accanto a un monumento che colpì in maniera particolare la sua sensibilità di “eurafricano”: quello di Vittorio Bottego, l’esploratore del corso del Giuba. Poi lo incontrai in occasione di alcune riunioni della Giovane Europa e in un campeggio sulle Alpi. Nel 1967, alla vigilia dell’aggressione sionista contro l’Egitto e la Siria, fui presente a un’affollata conferenza che egli tenne in una sala di Bologna, dove spiegò perché l’Europa doveva schierarsi a fianco del mondo arabo e contro l’entità sionista. Nel 1968, a Ferrara, partecipai a un convegno di dirigenti della Giovane Europa, nel corso del quale Thiriart sviluppò a tutto campo la linea antimperialista: “Qui in Europa, la sola leva antiamericana è e resterà un nazionalismo europeo ‘di sinistra’ (…) Quello che voglio dire è che all’Europa sarà necessario un nazionalismo di carattere popolare (…) Un nazionalcomunismo europeo avrebbe sollevato un’ondata enorme di entusiasmo. (…) Guevara ha detto che sono necessari molti Vietnam; e aveva ragione. Bisogna trasformare la Palestina in un nuovo Vietnam”. Fu l’ultimo suo discorso che ebbi modo di ascoltare.

Negli anni Sessanta, in qualità di giovanissimo militante della Giovane Europa, l’organizzazione da lui diretta, ebbi modo di vederlo diverse volte. Lo conobbi a Parma, nel 1964, accanto a un monumento che colpì in maniera particolare la sua sensibilità di “eurafricano”: quello di Vittorio Bottego, l’esploratore del corso del Giuba. Poi lo incontrai in occasione di alcune riunioni della Giovane Europa e in un campeggio sulle Alpi. Nel 1967, alla vigilia dell’aggressione sionista contro l’Egitto e la Siria, fui presente a un’affollata conferenza che egli tenne in una sala di Bologna, dove spiegò perché l’Europa doveva schierarsi a fianco del mondo arabo e contro l’entità sionista. Nel 1968, a Ferrara, partecipai a un convegno di dirigenti della Giovane Europa, nel corso del quale Thiriart sviluppò a tutto campo la linea antimperialista: “Qui in Europa, la sola leva antiamericana è e resterà un nazionalismo europeo ‘di sinistra’ (…) Quello che voglio dire è che all’Europa sarà necessario un nazionalismo di carattere popolare (…) Un nazionalcomunismo europeo avrebbe sollevato un’ondata enorme di entusiasmo. (…) Guevara ha detto che sono necessari molti Vietnam; e aveva ragione. Bisogna trasformare la Palestina in un nuovo Vietnam”. Fu l’ultimo suo discorso che ebbi modo di ascoltare. All’inizio degli anni Ottanta, Thiriart lavora a un libro che non ha mai visto la luce: L’Empire euro-soviétique de Vladivostok à Dublin. Il piano dell’opera prevede quindici capitoli, ciascuno dei quali si articola in numerosi paragrafi. Come appare evidente dal titolo di quest’opera, la posizione di Thiriart nei confronti dell’Unione Sovietica è notevolmente cambiata. Abbandonata la vecchia parola d’ordine “Né Mosca né Washington”, Thiriart assume ora una posizione che potrebbe essere riassunta così: “Con Mosca contro Washington”. Già tredici anni prima, d’altronde, in un articolo intitolato Prague, l’URSS et l’Europe (“La Nation Européenne”, n. 29, novembre 1968), denunciando gli intrighi sionisti nella cosiddetta “primavera di Praga”, Thiriart aveva espresso una certa soddisfazione per l’intervento sovietico e aveva cominciato a delineare una “strategia dell’attenzione” nei confronti dell’URSS. “Un’Europa occidentale NON AMERICANA – aveva scritto – permetterebbe all’Unione Sovietica di svolgere un ruolo quasi antagonista degli USA. Un’Europa occidentale alleata, o un’Europa occidentale AGGREGATA all’URSS sarebbe la fine dell’imperialismo americano (…) Se i Russi vogliono staccare gli Europei dall’America – e a lungo termine essi devono necessariamente lavorare per questo scopo – bisogna che ci offrano, in cambio della SCHIAVITU’ DORATA americana, la possibilità di costruire un’entità politica europea. Se la temono, il modo migliore di scongiurarla consiste nell’integrarvisi”.

All’inizio degli anni Ottanta, Thiriart lavora a un libro che non ha mai visto la luce: L’Empire euro-soviétique de Vladivostok à Dublin. Il piano dell’opera prevede quindici capitoli, ciascuno dei quali si articola in numerosi paragrafi. Come appare evidente dal titolo di quest’opera, la posizione di Thiriart nei confronti dell’Unione Sovietica è notevolmente cambiata. Abbandonata la vecchia parola d’ordine “Né Mosca né Washington”, Thiriart assume ora una posizione che potrebbe essere riassunta così: “Con Mosca contro Washington”. Già tredici anni prima, d’altronde, in un articolo intitolato Prague, l’URSS et l’Europe (“La Nation Européenne”, n. 29, novembre 1968), denunciando gli intrighi sionisti nella cosiddetta “primavera di Praga”, Thiriart aveva espresso una certa soddisfazione per l’intervento sovietico e aveva cominciato a delineare una “strategia dell’attenzione” nei confronti dell’URSS. “Un’Europa occidentale NON AMERICANA – aveva scritto – permetterebbe all’Unione Sovietica di svolgere un ruolo quasi antagonista degli USA. Un’Europa occidentale alleata, o un’Europa occidentale AGGREGATA all’URSS sarebbe la fine dell’imperialismo americano (…) Se i Russi vogliono staccare gli Europei dall’America – e a lungo termine essi devono necessariamente lavorare per questo scopo – bisogna che ci offrano, in cambio della SCHIAVITU’ DORATA americana, la possibilità di costruire un’entità politica europea. Se la temono, il modo migliore di scongiurarla consiste nell’integrarvisi”. Apparso nel 1964 in lingua francese, nel giro di due anni Un Empire de 400 millions d’hommes: l’Europe vide la luce in altre sei lingue europee. La traduzione italiana venne eseguita da Massimo Costanzo, (all’epoca redattore di “Europa Combattente”, organo italofono della Giovane Europa), il quale presentò l’opera con queste parole: “Il libro di Jean Thiriart è destinato a suscitare, per la sua profondità e per la sua chiarezza, un forte interesse. Ma da dove deriva questa chiarezza? Da un fatto molto semplice: l’autore ha usato un linguaggio essenzialmente politico, lontano dai fumi dell’ideologia e dalle costruzioni astratte o pseudometafisiche. Dopo una lettura attenta, nel libro si possono anche trovare impostazioni ideologiche, ma queste traspaiono dalle tesi politiche e non il contrario, come fino ad oggi è avvenuto nel campo nazionaleuropeo”. Nonostante le riserve che alcune “impostazioni ideologiche” dell’Autore (eurocentrismo, razionalismo, giacobinismo ecc.) potranno suscitare, il lettore di questa seconda edizione italiana probabilmente concorderà con quanto scriveva Massimo Costanzo quarant’anni or sono; anzi, si renderà conto che questo libro, senza dubbio il più famoso dei testi redatti da Thiriart

Apparso nel 1964 in lingua francese, nel giro di due anni Un Empire de 400 millions d’hommes: l’Europe vide la luce in altre sei lingue europee. La traduzione italiana venne eseguita da Massimo Costanzo, (all’epoca redattore di “Europa Combattente”, organo italofono della Giovane Europa), il quale presentò l’opera con queste parole: “Il libro di Jean Thiriart è destinato a suscitare, per la sua profondità e per la sua chiarezza, un forte interesse. Ma da dove deriva questa chiarezza? Da un fatto molto semplice: l’autore ha usato un linguaggio essenzialmente politico, lontano dai fumi dell’ideologia e dalle costruzioni astratte o pseudometafisiche. Dopo una lettura attenta, nel libro si possono anche trovare impostazioni ideologiche, ma queste traspaiono dalle tesi politiche e non il contrario, come fino ad oggi è avvenuto nel campo nazionaleuropeo”. Nonostante le riserve che alcune “impostazioni ideologiche” dell’Autore (eurocentrismo, razionalismo, giacobinismo ecc.) potranno suscitare, il lettore di questa seconda edizione italiana probabilmente concorderà con quanto scriveva Massimo Costanzo quarant’anni or sono; anzi, si renderà conto che questo libro, senza dubbio il più famoso dei testi redatti da Thiriart

Truyens considera que la elección de Emmanuel Macron es, sin duda, un efecto de la estrategia popperiana de Georges Soros. Macron no tenía un partido detrás, sino un movimiento de muy reciente constitución, puesto en marcha rápidamente según las tácticas aprobadas por la fundación que Soros había aplicado en otras partes del mundo. Tanto si Soros ha financiado como si no el movimiento “En marcha” de Macron, la política de éste, como la de Merkel y otros supuestos “líderes” europeos sigue una lógica Popper-sorosiana de disolución de los pueblos, sociedades y Estados en mayor medida que la lógica sesentayochista derivada de la Escuela de Frankfurt, instrumento que ahora consideran inadecuado porque podría tener los efectos contrarios a los esperados.

Truyens considera que la elección de Emmanuel Macron es, sin duda, un efecto de la estrategia popperiana de Georges Soros. Macron no tenía un partido detrás, sino un movimiento de muy reciente constitución, puesto en marcha rápidamente según las tácticas aprobadas por la fundación que Soros había aplicado en otras partes del mundo. Tanto si Soros ha financiado como si no el movimiento “En marcha” de Macron, la política de éste, como la de Merkel y otros supuestos “líderes” europeos sigue una lógica Popper-sorosiana de disolución de los pueblos, sociedades y Estados en mayor medida que la lógica sesentayochista derivada de la Escuela de Frankfurt, instrumento que ahora consideran inadecuado porque podría tener los efectos contrarios a los esperados.

Les auteurs ne cachent pas, du reste, les réserves que peuvent leur inspirer ce plan de travail, qui est celui de l’éducation nationale, mais ils ont choisi d’en montrer les éventuelles limites de l’intérieur. Le déploiement de ce modèle classique d’exposition de la philosophie a le mérite de susciter des échos chez tous les lecteurs, avancés ou moins avancés, de thèmes philosophiques. Il montre aussi qu’il est possible d’entrer dans la philosophie par différentes portes. C’est pourquoi Alain Renaut précise à juste titre qu’il n’est aucunement indispensable de lire ce livre dans l’ordre des parties et des chapitres. Nous ne sommes donc ni face à un manuel scolaire/universitaire à proprement parler, ni face à un anti-manuel, ce qui serait bien prétentieux, et une vaine coquetterie.

Les auteurs ne cachent pas, du reste, les réserves que peuvent leur inspirer ce plan de travail, qui est celui de l’éducation nationale, mais ils ont choisi d’en montrer les éventuelles limites de l’intérieur. Le déploiement de ce modèle classique d’exposition de la philosophie a le mérite de susciter des échos chez tous les lecteurs, avancés ou moins avancés, de thèmes philosophiques. Il montre aussi qu’il est possible d’entrer dans la philosophie par différentes portes. C’est pourquoi Alain Renaut précise à juste titre qu’il n’est aucunement indispensable de lire ce livre dans l’ordre des parties et des chapitres. Nous ne sommes donc ni face à un manuel scolaire/universitaire à proprement parler, ni face à un anti-manuel, ce qui serait bien prétentieux, et une vaine coquetterie.

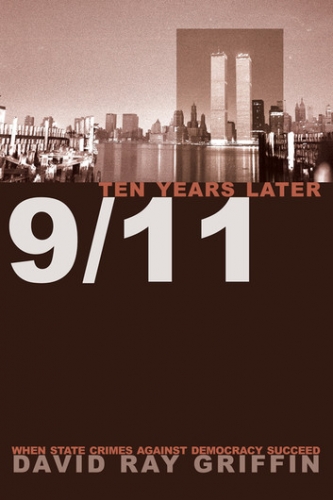

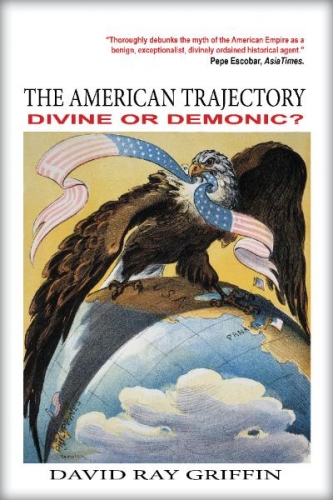

En tant que théologien et philosophe, il est bien conscient de l’importance de la nécessité pour la société de légitimer religieusement son autorité séculière, d’offrir à son peuple un bouclier contre la terreur et les craintes multiples de la vie par un mythe protecteur qui a été utilisé avec succès par les États-Unis pour terroriser les autres, de montrer comment les termes selon lesquels les États-Unis sont légitimés comme « nation choisie » par Dieu et les Américains comme « peuple élu » par Dieu ont évolué au fil du temps, à la lumière de l’avancée des processus de sécularisation et de pluralisme qui se sont développés. Les noms ont changé, mais la signification est la même. Dieu est de notre côté, et quand c’est ainsi, l’autre côté est maudit et peut être tué par le peuple de Dieu, qui se bat toujours contre le Diable.

En tant que théologien et philosophe, il est bien conscient de l’importance de la nécessité pour la société de légitimer religieusement son autorité séculière, d’offrir à son peuple un bouclier contre la terreur et les craintes multiples de la vie par un mythe protecteur qui a été utilisé avec succès par les États-Unis pour terroriser les autres, de montrer comment les termes selon lesquels les États-Unis sont légitimés comme « nation choisie » par Dieu et les Américains comme « peuple élu » par Dieu ont évolué au fil du temps, à la lumière de l’avancée des processus de sécularisation et de pluralisme qui se sont développés. Les noms ont changé, mais la signification est la même. Dieu est de notre côté, et quand c’est ainsi, l’autre côté est maudit et peut être tué par le peuple de Dieu, qui se bat toujours contre le Diable.

Doug Casey:

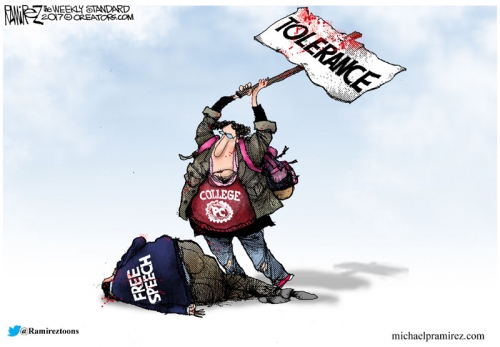

Doug Casey: The fact that the average American still puts up with this kind of nonsense and treats it with respect is a bad sign. PC values are continually inculcated into kids that go off to college—which, incidentally, is another idiotic mistake that most people make for both economic and philosophical reasons. It’s a real cause for pessimism.

The fact that the average American still puts up with this kind of nonsense and treats it with respect is a bad sign. PC values are continually inculcated into kids that go off to college—which, incidentally, is another idiotic mistake that most people make for both economic and philosophical reasons. It’s a real cause for pessimism.