The Empire Splits the Orthodox World – Possible Consequences

Ex: http://www.unz.com

In previous articles about this topic I have tried to set the context and explain why most Orthodox Churches are still used as pawns in purely political machinations and how the most commentators who discuss these issues today are using words and concepts in a totally twisted, secular and non-Christian way (which is about as absurd as discussing medicine while using a vague, misunderstood and generally non-medical terminology). I have also written articles trying to explain how the concept of “Church” is completely misunderstood nowadays and how many Orthodox Churches today have lost their original patristic mindset. Finally, I have tried to show the ancient spiritual roots of modern russophobia and how the AngloZionist Empire might try to save the Ukronazi regime in Kiev by triggering a religious crisis in the Ukraine. It is my hope that these articles will provide a useful context to evaluate and discuss the current crisis between the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Moscow Patriarchate.

My intention today is to look at the unfolding crisis from a more “modern” point of view and try to evaluate only what the political and social consequences of the latest developments might be in the short and mid term. I will begin by a short summary.

The current context: a summary

The Patriarchate of Constantinople has taken the official decision to:

- Declare that the Patriarch of Constantinople has the right to unilaterally grant autocephaly (full independence) to any other Church with no consultations with any the other Orthodox Churches.

- Cancel the decision by the Patriarch of Constantinople Dionysios IV in 1686 transferring the Kiev Metropolia (religious jurisdiction overseen by a Metropolite) to the Moscow Patriarchate (a decision which no Patriarch of Constantinople contested for three centuries!)

- Lift the anathema pronounced against the “Patriarch” Filaret Denisenko by the Moscow Patriarchate (in spite of the fact that the only authority which can lift an anathema is the one which pronounced it in the first place)

- Recognize as legitimate the so-called “Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kiev Patriarchate” which it previously had declared as illegitimate and schismatic.

- Grant actual grand full autocephaly to a future (and yet to be defined) “united Ukrainian Orthodox Church”

Most people naturally focus on this last element, but this might be a mistake, because while illegally granting autocephaly to a mix of nationalist pseudo-Churches is most definitely a bad decision, to act like some kind of “Orthodox Pope” and claim rights which only belong to the entire Church is truly a historical mistake. Not only that, but this mistake now forces every Orthodox Christian to either accept this as a fait accompli and submit to the megalomania of the wannabe Ortho-Pope of the Phanar, or to reject such unilateral and totally illegal action or to enter into open opposition. And this is not the first time such a situation has happened in the history of the Church. I will use an historical parallel to make this point.

The historical context:

The Church of Rome and the rest of the Christian world were already on a collision course for several centuries before the famous date of 1054 when Rome broke away from the Christian world. Whereas for centuries Rome had been the most steadfast bastion of resistance against innovations and heresies, the influence of the Franks in the Church of Rome eventually resulted (after numerous zig-zags on this topic) in a truly disastrous decision to add a single world (filioque - “and the son” in Latin) to the Symbol of Faith (the Credo in Latin). What made that decision even worse was the fact that the Pope of Rome also declared that he had the right to impose that addition upon all the other Christian Churches, with no conciliar discussion or approval. It is often said that the issue of the filioque is “obscure” and largely irrelevant, but that is just a reflection of the theological illiteracy of those making such statements as, in reality, the addition of the filioque completely overthrows the most crucial and important Trinitarian and Christological dogmas of Christianity. But what *is* true is that the attempt to unilaterally impose this heresy on the rest of the Christian world was at least as offensive and, really, as sacrilegious as the filioque itself because it undermined the very nature of the Church. Indeed, the Symbol of Faith defines the Church as “catholic” (Εἰς μίαν, Ἁγίαν, Καθολικὴν καὶ Ἀποστολικὴν Ἐκκλησίαν”) meaning not only “universal” but also “whole” or “all-inclusive”. In ecclesiological terms this “universality” is manifested in two crucial ways:

First, all Churches are equal, there is no Pope, no “historical see” granting any primacy just as all the Apostles of Christ and all Orthodox bishops are also equals; the Head of the Church is Christ Himself, and the Church is His Theadric Body filled with the Holy Spirit. Oh I know, to say that the Holy Spirit fills the Church is considered absolutely ridiculous in our 21st century post-Christian world, but check out these words from the Book of Acts: “For it seemed good to the Holy Ghost, and to us” (Acts 15:28) which clearly show that the members of the Apostolic Council in Jerusalem clearly believed and proclaimed that their decisions were guided by the Holy Spirit. Anyone still believing that will immediately see why the Church needs no “vicar of Christ” or any “earthly representative” to act in Christ’s name during His absence. In fact, Christ Himself clearly told us “lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world. Amen” (Matt 28:20). If a Church needs a “vicar” – then Christ and the Holy Spirit are clearly not present in that Church. QED.

Second, crucial decisions, decisions which affect the entire Church, are only taken by a Council of the entire Church, not unilaterally by any one man or any one Church. These are really the basics of what could be called “traditional Christian ecclesiology 101” and the blatant violation of this key ecclesiological dogma by the Papacy in 1054 was as much a cause for the historical schism between East and West (really, between Rome and the rest of Christian world) as was the innovation of the filioque itself.

I hasten to add that while the Popes were the first ones to claim for themselves an authority only given to the full Church, they were not the only ones (by the way, this is a very good working definition of the term “Papacy”: the attribution to one man of all the characteristics belonging solely to the entire Church). In the early 20th century the Orthodox Churches of Constantinople, Albania, Alexandria, Antioch, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Poland, and Romania got together and, under the direct influence of powerful Masonic lodges, decided to adopt the Gregorian Papal Calendar (named after the 16th century Pope Gregory XIII). The year was 1923, when the entire Russian Orthodox Church was being literally crucified on the modern Golgotha of the Bolshevik regime, but that did not prevent these Churches from calling their meeting “pan Orthodox”. Neither did the fact that the Russian, Serbian, Georgian, Jerusalem Church and the Holy Mountain (aka “Mount Athos”) rejected this innovation stop them. As for the Papal Calendar itself, the innovators “piously” re-branded it as “improved Julian” and other such euphemism to conceal the real intention behind this.

Finally, even the fact that this decision also triggered a wave of divisions inside their own Churches was not cause for them to reconsider or, even less so, to repent. Professor C. Troitsky was absolutely correct when he wrote that “there is no doubt that future historians of the Orthodox Church will be forced to admit that the Congress of 1923 was the saddest event of Church life in the 20th century” (for more on this tragedy see here, here and here). Here again, one man, Ecumenical Patriarch Meletius IV (Metaxakis) tried to “play Pope” and his actions resulted in a massive upheaval which ripped through the entire Orthodox world.

More recently, the Patriarch of Constantinople tried, once again, to convene what he would want to be an Orthodox “Ecumenical Council” under his personal authority when in 2016 (yet another) “pan Orthodox” council was convened on the island of Crete which was attended by the Churches of Alexandria , Jerusalem , Serbia , Romania , Cyprus , Greece, Poland , Albania and of the Czech Lands and Slovakia. The Churches of Russia, Bulgaria, Georgia and the USA (OCA) refused to attend. Most observers agreed that the Moscow Patriarchate played a key role in undermining what was clearly to be a “robber” council which would have introduced major (and fully non-Orthodox) innovations. The Patriarch of Constantinople never forgave the Russians for torpedoing his planned “ecumenical” council.

Some might have noticed that a majority of local Churches did attend both the 1923 and the 2016 wannabe “pan Orthodox” councils. Such an observation might be very important in a Latin or Protestant context, but in the Orthodox context is is absolutely meaningless for the following reasons:

The theological context:

In the history of the Church there have been many “robber” councils (meaning illegitimate, false, councils) which were attended by a majority of bishops of the time, and even a majority of the Churches; in this article I mentioned the life of Saint Maximos the Confessor (which you can read in full here) as a perfect example of how one single person (not even a priest!) can defend true Christianity against what could appear at the time as the overwhelming number of bishops representing the entire Church. But, as always, these false bishops were eventually denounced and the Truth of Orthodoxy prevailed.

Likewise, at the False Union of Florence, when all the Greek delegates signed the union with the Latin heretics, and only one bishop refused to to do (Saint Mark of Ephesus), the Latin Pope declared in despair “and so we have accomplished nothing!”. He was absolutely correct – that union was rejected by the “Body” of the Church and the names of those apostates who signed it will remain in infamy forever. I could multiply the examples, but what is crucial here is to understand that majorities, large numbers or, even more so, the support of secular authorities are absolutely meaningless in Christian theology and in the history of the Church and that, with time, all the lapsed bishops who attended robber councils are always eventually denounced and the Orthodox truth always proclaimed once again. It is especially important to keep this in mind during times of persecution or of brutal interference by secular authorities because even when they *appear* to have won, their victory is always short-lived.

I would add that the Russian Orthodox Church is not just “one of the many” local Orthodox Churches. Not only is the Russian Orthodox Church by far the biggest Orthodox Church out there, but Moscow used to be the so-called “Third Rome”, something which gives the Moscow Patriarchate a lot of prestige and, therefore, influence. In secular terms of prestige and “street cred” the fact that the Russians did not participate in the 1923 and 2016 congresses is much bigger a blow to its organizers than if, say, the Romanians had boycotted it. This might not be important to God or for truly pious Christians, but I assure you that this is absolutely crucial for the wannabe “Eastern Pope” of the Phanar…

Who is really behind this latest attack on the Church?

So let’s begin by stating the obvious: for all his lofty titles (“His Most Divine All-Holiness the Archbishop of Constantinople, New Rome, and Ecumenical Patriarch“ no less!), the Patriarch of Constantinople (well, of the Phanar, really), is nothing but a puppet in the hands of the AngloZionist Empire. An ambitious and vain puppet for sure, but a puppet nonetheless. To imagine that the Uber-loser Poroshenko would convince him to pick a major fight with the Moscow Patriarchate is absolutely laughable and totally ridiculous. Some point out that the Patriarch of Constantinople is a Turkish civil servant. While technically true, this does not suggest that Erdogan is behind this move either: right now Erdogan badly needs Russia on so many levels that he gains nothing and risks losing a lot by alienating Moscow. No, the real initiator of this entire operation is the AngloZionist Empire and, of course, the Papacy (which has always tried to create an “Orthodoxerein Ukraine” from the “The Eastern Crusade” and “Northern Crusades” of Popes Innocent III and Gregory IX to the Nazi Ukraine of Bandera – see here for details).

Why would the Empire push for such a move? Here we can find a mix of petty and larger geostrategic reasons. First, the petty ones: they range from the usual impotent knee-jerk reflex to do something, anything, to hurt Russia to pleasing of the Ukronazi emigrés in the USA and Canada. The geostrategic ones range from trying to save the highly unpopular Ukronazi regime in Kiev to breaking up the Orthodox world thereby weakening Russian soft-power and influence. This type of “logic” shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the Orthodox world today. Here is why:

The typical level of religious education of Orthodox Christians is probably well represented by the famous Bell Curve: some are truly completely ignorant, most know a little, and a few know a lot. As long as things were reasonably peaceful, all these Orthodox Christians could go about their daily lives and not worry too much about the big picture. This is also true of many Orthodox Churches and bishops. Most folks like beautiful rites (singing, golden cupolas, beautiful architecture and historical places) mixed in with a little good old superstition (place a candle before a business meeting or playing the lottery) – such is human nature and, alas, most Orthodox Christians are no different, even if their calling is to be “not of this world”. But now this apparently peaceful picture has been severely disrupted by the actions of the Patriarch of Constantinople whose actions are in such blatant and severe violation of all the basic canons and traditions of the Church that they literally force each Orthodox Christian, especially bishops, to break their silence and take a position: am I with Moscow or with Constantinople?

Oh sure, initially many (most?) Orthodox Christians, including many bishops, will either try to look away or limit themselves to vapid expressions of “regret” mixed in with calls for “unity”. A good example of that kind of wishy washy lukewarm language can already be found here. But this kind of Pilate-like washing of hands (“ain’t my business” in modern parlance) is unsustainable, and here is why: in Orthodox ecclesiology you cannot build “broken Eucharistic triangles”. If A is not in communion with B, then C cannot be in communion with A and B at the same time. It’s really an “either or” binary choice. At least in theory (in reality, such “broken triangles” have existed, most recently between the former ROCA/ROCOR, the Serbian Church and the Moscow Patriarchate, but they are unsustainable, as events of the 2000-2007 years confirmed for the ROCA/ROCOR). Still, no doubt that some (many?) will try to remain in communion with both the Moscow Patriarchate and the Constantinople Patriarchate, but this will become harder and harder with every passing month. In some specific cases, such a decision will be truly dramatic, I think of the monasteries on the Holy Mountain in particular.

On a more cynical level, I would note that the Patriarch of Constantinople has now opened a real Pandora’s box which now every separatist movement in an Orthodox country will be able to use to demand its own “autocephaly” which will threaten the unity of most Orthodox Churches out there. If all it takes to become “autocephalous” is to trigger some kind of nationalist uprising, then just imagine how many “Churches” will demand the same autocephaly as the Ukronazis are today! The fact that ethno-phyetism is a condemned heresy will clearly stop none of them. After all, if it is good enough for the “Ecumenical” Patriarch, it sure is good enough for any and all pseudo-Orthodox nationalists!

What the AngloZionist Empire has done is to force each Orthodox Christian and each Orthodox Church to chose between siding with Moscow or Constantinople. This choice will have obvious spiritual consequences, which the Empire couldn’t give a damn about, but it will also profound political and social consequences which, I believe, the Empire entirely missed.

The Moscow Patriarchate vs the Patriarchate of Constantinople – a sociological and political analysis

Let me be clear here that I am not going to compare and contrast the Moscow Patriarchate (MP) and the Patriarchate of Constantinople (PC) from a spiritual, theological or even ecclesiological point of view here. Instead, I will compare and contrast them from a purely sociological and political point of view. The differences here are truly profound.

| |

Moscow Patriarchate |

Patriarchate of Constantinople |

| Actual size |

Very big |

Small |

| Financial means |

Very big |

Small |

| Dependence on the support of the Empire and its various entities |

Limited |

Total |

| Relations with the Vatican |

Limited, mostly due to very strongly anti-Papist sentiments in the people |

Mutual support and de-facto alliance |

| Majority member’s outlook |

Conservative |

Modernist |

| Majority member’s level of support |

Strong |

Lukewarm |

| Majority member’s concern with Church rules/cannons/traditions |

Medium and selective |

Low |

| Internal dissent |

Practically eliminated (ROCA) |

Strong (Holy Mountain, Old Calendarists) |

From the above table you can immediately see that the sole comparative ‘advantage’ of the PC is that is has the full support of the AngloZionist Empire and the Vatican. On all the other measures of power, the MP vastly “out-guns” the PC.

Now, inside the Ukronazi occupied Ukraine, that support of the Empire and the Vatican (via their Uniats) does indeed give a huge advantage to the PC and its Ukronazi pseudo-Orthodox “Churches”. And while Poroshenko has promised that no violence will be used against the MP parishes in the Ukraine, we all remember that he was the one who promised to stop the war against the Donbass, so why even pay attention to what he has to say.

US diplomats and analysts might be ignorant enough to believe Poroshenko’s promises, but if that is the case then they are failing to realize that Poroshensko has very little control over the hardcore Nazi mobs like the one we saw last Sunday in Kiev. The reality is very different: Poroshenko’s relationship to the hardcore Nazis in the Ukraine is roughly similar to the one the House of Saud has with the various al-Qaeda affiliates in Saudi Arabia: they try to both appease and control them, but they end up failing every time. The political agenda in the Ukraine is set by bona fide Nazis, just as it is set in the KSA by the various al-Qaeda types. Poroshenko and MBS are just impotent dwarfs trying to ride on the shoulders of much more powerful devils.

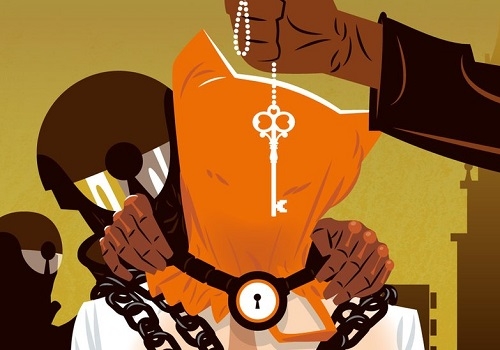

Sadly, and as always, the ones most at risk right now are the simple faithful who will resist any attempts by the Ukronazi death-squads to seize their churches and expel their priests. I don’t expect a civil war to ensue, not in the usual sense of the world, but I do expect a lot of atrocities similar to what took place during the 2014 Odessa massacre when the Ukronazis burned people alive (and shot those trying to escape). Once these massacres begin, it will be very, very hard for the Empire to whitewash them or blame it all on “Russian interference”. But most crucially, as the (admittedly controversial) Christian writer Tertullian noticed as far back as the 2nd century “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church”. You can be sure that the massacre of innocent Christians in the Ukraine will result in a strengthening of the Orthodox awareness, not only inside the Ukraine, but also in the rest of the world, especially among those who are currently “on the fence” so to speak, between the kind of conservative Orthodoxy proclaimed by the MP and the kind of lukewarm wishy washy “decaf” pseudo-Orthodoxy embodied by the Patriarchate of Constantinople. After all, it is one thing to change the Church Calendar or give hugs and kisses to Popes and quite another to bless Nazi death-squads to persecute Orthodox Christians.

To summarize I would say that by his actions, the Patriarch of Constantinople is now forcing the entire Orthodox world to make a choice between two very different kind of “Orthodoxies”. As for the Empire, it is committing a major mistake by creating a situation which will further polarize strongly, an already volatile political situation in the Ukraine.

There is, at least potentially, one more possible consequence from these developments which is almost never discussed: its impact inside the Moscow Patriarchate.

Possible impact of these developments inside the Moscow Patriarchate

Without going into details, I will just say that the Moscow Patriarchate is a very diverse entity in which rather different “currents” coexist. In Russian politics I often speak of Atlantic Integrationists and Eurasian Sovereignists. There is something vaguely similar inside the MP, but I would use different terms. One camp is what I would call the “pro-Western Ecumenists” and the other camp the “anti-Western Conservatives”. Ever since Putin came to power the pro-Western Ecumenists have been losing their influence, mostly due to the fact that the majority of the regular rank and file members of the MP are firmly behind the anti-Western Conservative movement (bishops, priests, theologians). The rabid hatred and fear of everything Russian by the West combined with the total support for anything anti-Russian (including Takfiris and Nazis) has had it’s impact here too, and very few people in Russia want the civilizational model of Conchita Wurst, John McCain or Pope Francis to influence the future of Russia. The word “ecumenism” has, like the word “democracy”, become a four letter word in Russia with a meaning roughly similar to “sellout” or “prostitution”. What is interesting is that many bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate who, in the past, were torn between the conservative pressure from their own flock and their own “ecumenical” and “democratic” inclinations (best embodied by the Patriarch of Constantinople) have now made a choice for the conservative model (beginning by Patriarch Kirill himself who, in the past, used to be quite favorable to the so-called “ecumenical dialog of love” with the Latins).

Now that the MP and the PC have broken the ties which previously united them, they are both free to pursue their natural inclinations, so to speak. The PC can become some kind of “Eastern Rite Papacy” and bask in an unhindered love fest with the Empire and the Vatican while the MP will now have almost no incentive whatsoever to pay attention to future offers of rapprochement by the Empire or the Vatican (these two always work hand in hand). For Russia, this is a very good development.

Make no mistake, what the Empire did in the Ukraine constitutes yet another profoundly evil and tragic blow against the long-suffering people of the Ukraine. In its ugliness and tragic consequences, it is quite comparable to the occupation of these lands by the Papacy via its Polish and Lithuanian agents. But God has the ability to turn even the worst horror into something which, in the end, will strengthen His Church.

Russia in general, and the Moscow Patriarchate specifically, are very much in a transition phase on many levels and we cannot overestimate the impact which the West’s hostility on all fronts, including spiritual ones, will have on the future consciousness of the Russian and Orthodox people. The 1990s were years of total confusion and ignorance, not only for Russia by the way, but the first decade of the new millennium has turned out to be a most painful, but also most needed, eye-opener for those who had naively trusted the notion that the West’s enemy was only Communism, not Russia as a civilizational model.

In their infinite ignorance and stupidity, the leaders of the Empire have always acted only in the immediate short term and they never bothered to think about the mid to long term effects of their actions. This is as true for Russia as it is for Iraq or the Balkans. When things eventually, and inevitably, go very wrong, they will be sincerely baffled and wonder how and why it all went wrong. In the end, as always, they will blame the “other guy”.

There is no doubt in my mind that the latest maneuver of the AngloZionist Empire in the Ukraine will yield some kind of feel-good and short term “victory” (“peremoga” in Ukrainian) which will be followed by a humiliating defeat (“zrada” in Ukrainian) which will have profound consequences for many decades to come and which will deeply reshape the current Orthodox world. In theory, these kinds of operations are supposed to implement the ancient principle of “divide and rule”, but in the modern world what they really do is to further unite the Russian people against the Empire and, God willing, will unite the Orthodox people against pseudo-Orthodox bishops.

Conclusion:

In this analysis I have had to describe a lot of, shall we say, “less than inspiring” realities about the Orthodox Church and I don’t want to give the impression that the Church of Christ is as clueless and impotent as all those denominations, which, over the centuries have fallen away from the Church. Yes, our times are difficult and tragic, but the Church has not lost her “salt”. So what I want to do in lieu of a personal conclusion is to quote one of the most enlightened and distinguished theologians of our time, Metropolitan Hierotheos of Nafpaktos, who in his book “The Mind of the Orthodox Church” (which I consider one of the best books available in English about the Orthodox Church and a “must read” for anybody interested in Orthodox ecclesiology) wrote the following words:

Saint Maximos the Confessor says that, while Christians are divided into categories according to age and race, nationalities, languages, places and ways of life, studies and characteristics, and are “distinct from one another and vastly different, all being born into the Church and reborn and recreated through it in the Spirit” nevertheless “it bestows equally on all the gift of one divine form and designation, to be Christ’s and to bear His Name. And Saint Basil the Great, referring to the unity of the Church says characteristically: “The Church of Christ is one, even tough He is called upon from different places”. These passages, and especially the life of the Church, do away with every nationalistic tendency. It is not, of course, nations and homelands that are abolished, but nationalism, which is a heresy and a great danger to the Church of Christ.

Metropolitan Hierotheos is absolutely correct. Nationalism, which itself is a pure product of West European secularism, is one of the most dangerous threats facing the Church today. During the 20th century it has already cost the lives of millions of pious and faithful Christians (having said that, this in no way implies that the kind of suicidal multiculturalism advocated by the degenerate leaders of the AngloZionist Empire today is any better!). And this is hardly a “Ukrainian” problem (the Moscow Patriarchate is also deeply infected by the deadly virus of nationalism). Nationalism and ethno-phyletism are hardly worse than such heresies as Iconoclasm or Monophysitism/Monothelitism were in the past and those were eventually defeated. Like all heresies, nationalism will never prevail against the “Church of the living God” which is the “the pillar and ground of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15) and while many may lapse, others never will.

In the meantime, the next couple of months will be absolutely crucial. Right now it appears to me that the majority of the Orthodox Churches will first try to remain neutral but will have to eventually side with the Moscow Patriarchate and against the actions of Patriarch Bartholomew. Ironically, the situation inside the USA will most likely be particularly chaotic as the various Orthodox jurisdictions in the USA have divided loyalties and are often split along conservative vs modernizing lines. The other place to keep a close eye on will be the monasteries on the Holy Mountain were I expect a major crisis and confrontation to erupt.

With the crisis in the Ukraine the heresy of nationalism has reached a new level of infamy and there will most certainly be a very strong reaction to it. The Empire clearly has no idea what kind of dynamic it has now set in motion.

Voici les propos qu’on lui prête :

Voici les propos qu’on lui prête : Selon ce grandiose Calgacus, on est là aussi pour être rincés par les impôts qui n’ont jamais été aussi élevés (France, Allemagne, USA) pour les couches faibles et moyennes dans ce monde pourtant si libéral :

Selon ce grandiose Calgacus, on est là aussi pour être rincés par les impôts qui n’ont jamais été aussi élevés (France, Allemagne, USA) pour les couches faibles et moyennes dans ce monde pourtant si libéral :

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L'Eurasisme comme phare idéologique malgré les frasques de Douguine ; nous nous devons de le justifier, parce que nous pensons et persistons à penser malgré les mauvais temps ukrainiens et le brouillard néo-souverainiste que l'orientation eurasiste est l'expression idéologique la plus immédiate vers la « révolution conservatrice ».

L'Eurasisme comme phare idéologique malgré les frasques de Douguine ; nous nous devons de le justifier, parce que nous pensons et persistons à penser malgré les mauvais temps ukrainiens et le brouillard néo-souverainiste que l'orientation eurasiste est l'expression idéologique la plus immédiate vers la « révolution conservatrice ».

Pour l’ethnologue Jean Servier, auteur de L’Homme et l’Invisible (Imago, 1980), « La science occidentale défend l’hominisation du singe, peut‐être parce qu’il est plus facile d’être un singe « parvenu » qu’un ange déchu […]. Selon toutes les traditions, l’homme a été d’abord esprit, participant de toute la sérénité du Monde Invisible. Un désir l’a poussé à rompre l’harmonie cosmique : il lui a fallu, en expiation, descendre dans la matière, dans l’univers des formes, dans l’animalité : revêtir des vêtements de peaux. »

Pour l’ethnologue Jean Servier, auteur de L’Homme et l’Invisible (Imago, 1980), « La science occidentale défend l’hominisation du singe, peut‐être parce qu’il est plus facile d’être un singe « parvenu » qu’un ange déchu […]. Selon toutes les traditions, l’homme a été d’abord esprit, participant de toute la sérénité du Monde Invisible. Un désir l’a poussé à rompre l’harmonie cosmique : il lui a fallu, en expiation, descendre dans la matière, dans l’univers des formes, dans l’animalité : revêtir des vêtements de peaux. »

L’identité entre modernisation et occidentalisation du Japon est un des lieux communs les plus véhiculés. Les écrivains, les cinéastes, mais également, ce qui est plus grave, les historiens décrivent souvent un archipel féodal qui aurait embrassé la modernité occidentale en découvrant la puissance nouvelle des empires européens en pleine expansion au milieu du XIXe siècle. Les canonnières britanniques auraient suscité chez ce peuple de tradition isolationniste un sentiment d’urgence et de faiblesse, l’obligeant à rattraper son retard technique, économique et politique. Cette approche considère donc que la modernité japonaise est le produit de l’Occident, que les causes profondes de la transformation de la société japonaise sont exogènes et que ce changement radical peut se comprendre sur le mode de la pure et simple imitation, notamment à travers des tendances nouvelles comme le nationalisme, l’impérialisme ou encore le capitalisme à la japonaise.

L’identité entre modernisation et occidentalisation du Japon est un des lieux communs les plus véhiculés. Les écrivains, les cinéastes, mais également, ce qui est plus grave, les historiens décrivent souvent un archipel féodal qui aurait embrassé la modernité occidentale en découvrant la puissance nouvelle des empires européens en pleine expansion au milieu du XIXe siècle. Les canonnières britanniques auraient suscité chez ce peuple de tradition isolationniste un sentiment d’urgence et de faiblesse, l’obligeant à rattraper son retard technique, économique et politique. Cette approche considère donc que la modernité japonaise est le produit de l’Occident, que les causes profondes de la transformation de la société japonaise sont exogènes et que ce changement radical peut se comprendre sur le mode de la pure et simple imitation, notamment à travers des tendances nouvelles comme le nationalisme, l’impérialisme ou encore le capitalisme à la japonaise.

La modernité japonaise se caractérise également par l’émergence de nationalismes de nature différente. Si les premiers intellectuels de la période Meiji s’interrogèrent sur la possibilité d’un changement de régime pour permettre aux Japonais de disposer de plus de droits individuels (liberté de réunion, d’association, d’expression…) et de véritables libertés politiques, le débat s’est ensuite orienté sur la question de la définition de cette nouvelle identité japonaise. « À partir des années 1887-1888 […], les termes du débat évoluèrent et se cristallisèrent désormais sur la question des identités à l’intérieur de la nation, avec un balancement entre trois éléments, l’Occident et son influence toujours fascinante et menaçante, l’Orient (mais il s’agit surtout de la Chine) qui devint une sorte de terre d’utopie ou d’expansion, et le Japon enfin, dont il fallait sans cesse redéfinir l’essence entre les deux pôles précédents. » Ce qui est particulièrement intéressant dans le cas japonais, c’est que le nationalisme, qui est par excellence une doctrine politique moderne, ne s’est pas seulement constitué à partir du modèle occidental.

La modernité japonaise se caractérise également par l’émergence de nationalismes de nature différente. Si les premiers intellectuels de la période Meiji s’interrogèrent sur la possibilité d’un changement de régime pour permettre aux Japonais de disposer de plus de droits individuels (liberté de réunion, d’association, d’expression…) et de véritables libertés politiques, le débat s’est ensuite orienté sur la question de la définition de cette nouvelle identité japonaise. « À partir des années 1887-1888 […], les termes du débat évoluèrent et se cristallisèrent désormais sur la question des identités à l’intérieur de la nation, avec un balancement entre trois éléments, l’Occident et son influence toujours fascinante et menaçante, l’Orient (mais il s’agit surtout de la Chine) qui devint une sorte de terre d’utopie ou d’expansion, et le Japon enfin, dont il fallait sans cesse redéfinir l’essence entre les deux pôles précédents. » Ce qui est particulièrement intéressant dans le cas japonais, c’est que le nationalisme, qui est par excellence une doctrine politique moderne, ne s’est pas seulement constitué à partir du modèle occidental.

Péladan was the head of the Ordre Kabbalistique Rose-Croix (Kabbalistic Order of the Rosicrucian), succeeding his brother Adrien. While the original Rosicrucians, who had appeared mysteriously in Europe during the early seventeenth century and issued anonymous manifestos, seem to have been among the precursors of the Masonry and Illuminism that fermented the French Revolution against the Church and the Monarch, Péladan, on the contrary, was a Catholic traditionalist who repudiated the ideals of the French Revolution and the “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” of the Grand Orient of Masonry, stating in 1883, “I believe in the Ideal, Tradition and Hierarchy.”

Péladan was the head of the Ordre Kabbalistique Rose-Croix (Kabbalistic Order of the Rosicrucian), succeeding his brother Adrien. While the original Rosicrucians, who had appeared mysteriously in Europe during the early seventeenth century and issued anonymous manifestos, seem to have been among the precursors of the Masonry and Illuminism that fermented the French Revolution against the Church and the Monarch, Péladan, on the contrary, was a Catholic traditionalist who repudiated the ideals of the French Revolution and the “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” of the Grand Orient of Masonry, stating in 1883, “I believe in the Ideal, Tradition and Hierarchy.” The Salon de la Rose et Croix was established in 1892 to exhibit Symbolist art to the public. Art was magic, not rituals and incantations. It was intended as the harbinger of a spiritual revolution that would overthrow the materialistic and the decadent, and as the antithesis to the art of the other salons. The first exhibition drew fifty thousand visitors. Clearly, the French yearned for something transcending the crassness of Grand Orient liberalism and secularism, which had rotted France for a century; the “disenchantment of the world,” as he called it. Richard Wagner’s music had a special place, Péladan regarding Wagner as “a therapeutic detoxifier of France’s materialism.” Erik Satie was the Order’s official composer, and Debussy was a close colleague. Péladan defined what was required in his appeal for exhibitors: “The order favors the Catholic Ideal and mysticism. After that, Legends, Myths, Allegory, Dreams, the paraphrasing of great poets, and finally, all lyricism.”

The Salon de la Rose et Croix was established in 1892 to exhibit Symbolist art to the public. Art was magic, not rituals and incantations. It was intended as the harbinger of a spiritual revolution that would overthrow the materialistic and the decadent, and as the antithesis to the art of the other salons. The first exhibition drew fifty thousand visitors. Clearly, the French yearned for something transcending the crassness of Grand Orient liberalism and secularism, which had rotted France for a century; the “disenchantment of the world,” as he called it. Richard Wagner’s music had a special place, Péladan regarding Wagner as “a therapeutic detoxifier of France’s materialism.” Erik Satie was the Order’s official composer, and Debussy was a close colleague. Péladan defined what was required in his appeal for exhibitors: “The order favors the Catholic Ideal and mysticism. After that, Legends, Myths, Allegory, Dreams, the paraphrasing of great poets, and finally, all lyricism.”

L’ouvrage est essentiel car depuis le délire a débordé des campus et gagné la société occidentale toute entière. En même temps qu’elle déboulonne les statues, remet en cause le sexe de Dieu et diabolise notre héritage littéraire et culturel, cette société intégriste-sociétale donc menace le monde libre russe, chinois ou musulman (je ne pense pas à Riyad…) qui contrevient à son alacrité intellectuelle. Produit d’un nihilisme néo-nietzschéen, de l’égalitarisme démocratique et aussi de l’ennui des routines intellos (Bloom explique qu’on voulait « débloquer des préjugés, « trouver du nouveau »), la pensée politiquement correcte va tout dévaster comme un feu de forêt de Stockholm à Barcelone et de Londres à Berlin. On va dissoudre les nations et la famille (ou ce qu’il en reste), réduire le monde en cendres au nom du politiquement correct avant d’accueillir dans les larmes un bon milliard de réfugiés. Bloom pointe notre lâcheté dans tout ce processus, celle des responsables et l’indifférence de la masse comme toujours.

L’ouvrage est essentiel car depuis le délire a débordé des campus et gagné la société occidentale toute entière. En même temps qu’elle déboulonne les statues, remet en cause le sexe de Dieu et diabolise notre héritage littéraire et culturel, cette société intégriste-sociétale donc menace le monde libre russe, chinois ou musulman (je ne pense pas à Riyad…) qui contrevient à son alacrité intellectuelle. Produit d’un nihilisme néo-nietzschéen, de l’égalitarisme démocratique et aussi de l’ennui des routines intellos (Bloom explique qu’on voulait « débloquer des préjugés, « trouver du nouveau »), la pensée politiquement correcte va tout dévaster comme un feu de forêt de Stockholm à Barcelone et de Londres à Berlin. On va dissoudre les nations et la famille (ou ce qu’il en reste), réduire le monde en cendres au nom du politiquement correct avant d’accueillir dans les larmes un bon milliard de réfugiés. Bloom pointe notre lâcheté dans tout ce processus, celle des responsables et l’indifférence de la masse comme toujours. « Les aventuriers sexuels comme Margaret Mead et d'autres qui ont trouvé l'Amérique trop étroite nous ont dit que non seulement nous devons connaître d'autres cultures et apprendre à les respecter, mais nous pourrions aussi en tirer profit. Nous pourrions suivre leur exemple et nous détendre, nous libérer de l'idée que nos tabous ne sont rien d'autre que des contraintes sociales. »

« Les aventuriers sexuels comme Margaret Mead et d'autres qui ont trouvé l'Amérique trop étroite nous ont dit que non seulement nous devons connaître d'autres cultures et apprendre à les respecter, mais nous pourrions aussi en tirer profit. Nous pourrions suivre leur exemple et nous détendre, nous libérer de l'idée que nos tabous ne sont rien d'autre que des contraintes sociales. » Bloom enfin a compris l’usage ad nauseam qu’on fera de la référence hitlérienne : tout est décrété raciste, fasciste, nazi, sexiste dans les campus US dès 1960, secrétaires du rectorat y compris ! Mais lui reprenant Marx ajoute que ce qui passe en 1960 n’est ni plus ni moins une répétition comique du modèle tragique de 1933. Les juristes nazis comme Carl Schmitt décrétaient juive la science qui ne leur convenait pas comme aujourd’hui on la décrète blanche ou sexiste.

Bloom enfin a compris l’usage ad nauseam qu’on fera de la référence hitlérienne : tout est décrété raciste, fasciste, nazi, sexiste dans les campus US dès 1960, secrétaires du rectorat y compris ! Mais lui reprenant Marx ajoute que ce qui passe en 1960 n’est ni plus ni moins une répétition comique du modèle tragique de 1933. Les juristes nazis comme Carl Schmitt décrétaient juive la science qui ne leur convenait pas comme aujourd’hui on la décrète blanche ou sexiste.