|

Othmar Spann: Vom klerikalfaschistischen Ständestaat und seinen Kontinuitäten

von Heide Hammer

Ex: http://www.contextxxi.at/

Einer wollte den Führer führen. Nein: Einige wollten den Führer führen und wirkten so im Zeichen des Führers. Ob Heidegger, Rosenberg oder Spann, die Qualität ihrer Beiträge bleibt in diesem Kontext sekundär, wenn auch im Sinne der üblichen Vorwegnahme bei Spann die Betonung auf der philosophischen Stupidität liegen kann. Ihm gelang jedoch die Formierung eines Kreises, der mehr als sechzig Jahre nach seiner eigenen Entfernung von der Universität, der heutigen WU-Wien, das Gewäsch von Ganzheit wiederholt und daneben peinlich bemüht wirkt, keinen runden Geburtstag des Meisters oder seines ersten Schülers, manchmal auch des zweiten oder folgender, zu vergessen und zumeist mit einem Presseartikel, besser mit einem Jubiläumsband zu bedenken. Einer wollte den Führer führen. Nein: Einige wollten den Führer führen und wirkten so im Zeichen des Führers. Ob Heidegger, Rosenberg oder Spann, die Qualität ihrer Beiträge bleibt in diesem Kontext sekundär, wenn auch im Sinne der üblichen Vorwegnahme bei Spann die Betonung auf der philosophischen Stupidität liegen kann. Ihm gelang jedoch die Formierung eines Kreises, der mehr als sechzig Jahre nach seiner eigenen Entfernung von der Universität, der heutigen WU-Wien, das Gewäsch von Ganzheit wiederholt und daneben peinlich bemüht wirkt, keinen runden Geburtstag des Meisters oder seines ersten Schülers, manchmal auch des zweiten oder folgender, zu vergessen und zumeist mit einem Presseartikel, besser mit einem Jubiläumsband zu bedenken.

Othmar Spann inthronisierte sich in einem hierarchischen Ständemodell - an der Spitze - und war als Lehrer geistiges Zentrum der von ihm Erwählten. In seinem 1921 erstmals veröffentlichten Werk Der wahre Staat. Vorlesungen über Abbruch und Neubau der Gesellschaft ordnet er "Stände nach ihren geistigen Grundlagen"1 und ficht gegen Demokratie, Liberalismus und vor allem marxistischen Sozialismus. Ordnendes Prinzip sei: "daß jeder niedere Stand geistig vom jeweils höheren geführt wird (im Original gesperrt), nach dem geistigen Lebensgesetz aller Gemeinschaft und Gemeinschaftsverbindung 'Unterordnung des Niedern unter das Höhere'" (Der wahre Staat, S.176).

Seine zusammenfassende "Übersicht der Stände nach ihren geistigen Grundlagen": "1. die Handarbeiter (verankert im sinnlich-vitalen Leben); 2. die höheren Arbeiter, zerfallend in Kunstwerker und darstellende Geistesarbeiter (verankert nicht mehr allein in dem sinnlich-vitalen, sondern auch in einem höheren geistigen Leben, in diesem aber nur, im wesentlichen, teilnehmend); 3. die Wirtschaftsführer, die in wirtschaftlich-organisatorischer Hinsicht selbständig, schöpferisch wirken, im übrigen aber mehr im Sinnlich-Vitalen oder höchstens noch teilnehmend im Geistesleben verankert sind; 4. die Staatsführer, schöpferisch in sittlich-organisatorischer Hinsicht, im wesentlichen nur teilnehmend im höheren Geistesleben; eine Sondergruppe der Staatsführer bilden die höheren selbständig wirkenden Krieger und Priester; 5. endlich die Weisen oder der schöpferisch höhere Lehrstand (im Original gesperrt), der nur uneigentlich ein Stand ist und dessen Schöpfungen zuerst ein vermittelnder geistiger Stand (5 a) weitergibt." (Ebd., S. 175)

Die Figur des Kreises

Auch er hatte zumindest einen Koch dabei - um "Vollstand" also "handelnd" (Ebd., S. 176) zu werden - diese sind durchaus zahlreich, er führt seine Schüler in Privatseminaren (Sonntag Vormittag bei sich zuhause) in die Grundlagen seiner Gesellschaftslehre ein.2 Primus wird - mit überaus langem Atem in seinem Wirken - Walter Heinrich. Er promoviert 1925 bei Spann, wird 1927 sein Assistent, habilitiert sich 1928 und erhält 1933 an der Wiener Hochschule für Welthandel einen Lehrstuhl für Nationalökonomie. Viele Jahre später zeichnet er in der Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung ein Bild wunderbarer Harmonie dieser Lehrer-Schüler-Beziehung, ein Arbeitszusammenhang, der sehr auf politischen Einfluss zielte, hingegen in der Erinnerung jeweils von der konkreten historischen Situation abstrahiert und metaphysische Distanz beansprucht. Der Meister einer elitären Verbindung provoziert den Terminus "Genie", Kritik wird folglich zu einer inadäquaten Form der Auseinandersetzung, lediglich Analogien zu genialen Personen auf anderen Gebieten (Mozart) erleichtern die Übersetzung jener "Größe", die nunmehr in der Erzählung wirkt:3 "Eine ... tiefer schürfende Erklärung für seine [Spanns] Wirksamkeit liegt sicherlich in der geschlossenen Einheit von Leben und Lehre, von Persönlichkeit und geistigem Werk. Hier war das Eroshafte und das Logoshafte, freundschaftliche Nähe und Geisteskraft in seltener Einheit zusammengewachsen und haben vermöge dieser schöpferischen Verbindung einen Gründungsakt eingeleitet, der weiterwirkt. Vom ersten Geistesblitz der Gründung bis zur Entfaltung des Werkes ... der Wurzelgrund der Lehre wurde niemals verlassen. Dieser Wurzelgrund ... ist der Befund, daß Geist nur am anderen Geist werden kann, also gliedhaft; und die Erkenntnis: wo Glied, da Ganzheit. Damit ist eine neue Eroslehre begründet, eine neue Gemeinschaftslehre, eine neue Gesellschaftslehre."

J. Hanns Pichler, ein später Apologet und heute Vorstand des Instituts für Volkswirtschaftstheorie und -politik an der WU-Wien, übernimmt u.a. die Aufgabe, in gegebenen Abständen auch an den Schüler zu erinnern, an Geburtstagen, später posthum4 oder die Erinnerung an Spann und Heinrich zu verbinden3. Daneben oder danach protegiert Spann Jakob Baxa, der Rechtswissenschaften studiert hatte; von Spann zum Dank für seine intensive und wertvolle Auseinandersetzung mit der Romantik im Fach Gesellschaftslehre habilitiert (Siegfried, S. 72). Wilhelm Andrae wechselt ebenso unter dem Einfluss Spanns von der klassischen Philologie, mit der er an der Berliner Universität nicht reüssieren konnte, zur Nationalökonomie; er erhält 1927 in Graz einen Lehrstuhl für Politische Ökonomie (Ebd.). Seine Übersetzung von Platons Staat, woran Spann gerne seine Überlegungen knüpft, wird hier als Habilitationsschrift anerkannt. Hans Riehl promoviert 1923 bei Spann, die Habilitation 1928 kann bereits bei seinem Freund Wilhelm Andrae in Graz erfolgen (Ebd., S. 73).

Ernst von Salomon5, selbst in jenem Kräftefeld aktiv, das in der Weimarer Republik von Konservativen Revolutionären gebildet wird (u.a. an der Ermordung von Außenminister Walter Rathenau am 24. Juni 1922 beteiligt und verurteilt), hielt sich auf Einladung Spanns in Wien auf und beschreibt in seinem Bestseller, Der Fragebogen6 das alltägliche politische Verhalten der Spann-Schüler (Zit. nach Siegfried, S. 71): "Die 'Spannianer' bildeten auf der Universität eine besondere Gruppe, die größte Gruppe von allen, und, wie ich wohl behaupten darf, auch die geistig lebendigste. In jeder Verschwörerenklave auf den Gängen, in den Hallen und vor den Toren waren Spannianer, mit dem Ziel einer kleinen Extraverschwörung, wie ich vermute, - die beiden Spannsöhne vermochten schon gar nicht anders durch die Universität zu schlendern, wo sie gar nichts zu suchen hatten, ohne ununterbrochen nach allen Seiten vertrauensvoll zu blinzeln. Jeder einzelne von den Spannschülern mußte das Bewußtsein haben, an etwas selber mitzuarbeiten, was mit seiner Wahrheit mächtig genug war, die Welt zu erfüllen, jedes Vakuum auszugleichen, an einem System, so rund, so glatt, so kristallinisch in seinem inneren Aufbau, daß jedermann hoffen durfte, in gar nicht allzulanger Zeit den fertigen Stein der Weisen in der Hand zu haben."7

Weiter oben im Text zeigt von Salomon Interesse an der Tätigkeit Adalbert und Rafael Spanns und legt ihnen die Worte in den Mund: "Schau, das verstehst du net - wir packeln halt" (Zit. nach Siegfried, S. 238). Der Autor versucht in der nachgeordneten Darstellung die ideologischen Wendungen der Akteure zu analysieren, schwankt dabei von Gefasel über "jahrhundertelang[en] ... Verkehr mit fremden Völkerschaften und widerstrebenden Mächten" - die k. u. k. Monarchie wiedermal - und methodischen Aspekten des Verfahrens männerbündischer Dominanz: "Nichts schien so bedeutend, nichts aber auch so unbedeutend, daß es außer acht gelassen werden könnte." (Ebd.)

Die Protagonisten dieser Art Universalismus richten ihre Aktivitäten nach verschiedenen Polen, um in der zeitweiligen Konkurrenz von Nationalsozialismus, Faschismus und Ständestaat ebenso ein Netz zu bilden, wie in den Kontinuitäten der 2. Republik. Ein Blick auf die umfangreiche Publikationsliste J. Hanns Pichlers, des nunmehrigen Vorstands der Gesellschaft für Ganzheitsforschung, dokumentiert eine der Traditionslinien. Sein Bemühen gilt den Klein- und Mittelbetrieben, dem Kleinbürgertum, eine mögliche ideologische Parallele zu Othmar Spann, und - entsprechend seiner Funktion - den Anwendungsgebieten des ganzheitlichen Denkens.8 Dass er im gegebenen politischen Kräftefeld die Publikationsmöglichkeit im Organ der Freiheitlichen Akademie, Freiheit und Verantwortung wahrnimmt, verwundert kaum.9 Gerne bespricht er in der von ihm herausgegebenen Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung Übersetzungen oder Neuauflagen der Schriften Julius Evolas10, jenes faschistischen Philosophen und Mystikers, der Mussolini von seiner Philosophie überzeugen wollte, die SS liebte und heute Inspiration vieler rechter AktivistInnen ist. Evolas 'Cavalcare la tigre' (Den Tiger reiten) sieht Pichler "ungemein aufrüttelnd und zeitgemäß zugleich", der beliebte Plot 'Untergang des Abendlandes' wird diesmal durch die "Auflösung im Bereich des Gemeinschaftslebens" gegeben und Pichler konkretisiert, "von Staat und Parteien, einer weithin endemisch gewordenen Krise des Patriotismus, von Ehe und Familie bis hin zu den Beziehungen der Geschlechter untereinander" (Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung 4 (1999), S. 209). Denn, so die Diagnose Pichlers in einer Rezension des von Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing herausgegebenen Lexikon des Konservativismus (Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung 2 (1998), S. 93), "in einer pluralistisch zerrissenen und 'unkonservativen' Zeit" dürfen dahingehend mutige Leistungen (das vorliegende Lexikon) nicht geschmälert werden - obgleich er die "notorische und offenbar nicht auszumerzende[!] Fehlinterpretation" der inneren Ordnung der Werke Spanns bedauert -, den Wirren der Zeit werden der ganzheitlichen "Geistestradition verpflichtete Autoren" vor- und gegenübergestellt, allen voran immer wieder Spann.

Fragen der politischen Funktion, der Adressaten und Verbündeten der universalistischen Staatslehre werden insoweit unterschiedlich beantwortet, als AutorInnen wie Meyer11, Schneller12 oder Resele13 einen Zusammenhang des ideologischen KSpanns und der sozialen Interessen der kleinbürgerlichen Mittelschicht betonen, während Siegfried darauf beharrt, dass sich dahingehend keine eindeutige Beziehung feststellen ließe, die konkreten Bündnispartner (Heimwehr, Stahlhelm) vielmehr Oberklassen repräsentierten (Vgl. Siegfried, S. 14). Spann wirkt im Zeichen eines "dritten Weges", ein Motiv, das im Kontext der Konservativen Revolution14 an unterschiedlichen Positionen deutlich wird und später gerne von VertreterInnen einer vermeintlich "Neuen Rechten" (Nouvelle Droite)15 affirmiert wird. Das Ständestaatskonzept bietet in seinem Kampf gegen den Historischen Materialismus und die politische Organisation der ArbeiterInnenbewegung eine vorgeblich konsensuale Alternative, die als Wirtschaftsordnung "... jeden, Arbeiter wie Unternehmer, aus seiner Vereinzelung herausreißt und ihm jene Eingliederung in eine Ganzheit gewährt, welche Aufgehobenheit und Beruhigung bedeutet statt vernichtenden Wettbewerb, statt der hastigen Unruhe und Erregung der kapitalistischen Wirtschaftsordnung" (Der wahre Staat, S. 234). In Anlehnung an die Gesellschafts- und Staatslehre der politischen Romantik (Adam Müller) war Spann bemüht, soziale Antagonismen, Phänomene des Klassenkampfes in einem geistigen Gesamtzusammenhang aufzulösen (Vgl. Siegfried, S. 32-34) und das Glück der Unterordnung, der freudigen Hingabe an die subalterne Funktion im hierarchischen Gefüge in unglaublichen Variationen und Auflagen zu verbreiten.

In den Anfängen seiner akademischen Karriere, Spann habilitiert sich 1907 an der Deutschen Technischen Hochschule in Brünn, positioniert er sich in den nationalistischen Auseinandersetzungen der Germanisierungspolitik in der österreichischen Monarchie (Zit. nach Siegfried, S. 43):

"Der Begriff des passiven Mitgliedes ist theoretisch wichtig zur Beurteilung der Bedeutung der Rasse und praktisch für die Frage der Eindeutschung der slawischen Massen. Nehmen wir an, eine bestimmte nationale Gemeinschaft unterwerfe sich eine fremdrassige, minderbefähigte Nachbarnation, entnationalisiere sie und füge sie damit in ihre eigene Gemeinschaft ein. Wie wirkt dies auf den Körper der Nation? Wenn die neuen Mitglieder rassemäßig zur aktiven Teilnahme an der nationalen Kultur wenig befähigt sind, so können sie als passive Mitglieder doch sehr wertvoll werden." (Othmar Spann: Kurzgefaßtes System der Gesellschaftslehre, S. 203)

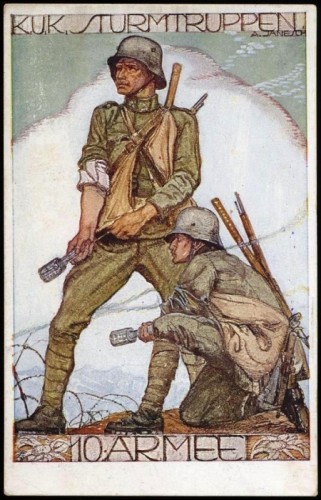

Derartige Tiraden bedingen nach dem Zusammenbruch der Monarchie die Notwendigkeit seiner Rückkehr nach Wien, wo er von 1919-1938 als Ordinarius für Gesellschafts- und Nationalökonomie an der rechts- und staatswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Wien wirkt. Die kaum dreiwöchige Felderfahrung Spanns im 1. Weltkrieg, er wurde am 21. August 1914 in der Schlacht bei Kraspe verwundet, verhindert vorläufig die wichtige Dekoration durch eine militärische Auszeichnung (Siegfried, S. 48). Er beantragt daher selbst die Verleihung eines militärischen Ordens, u.a. da seine Vorgesetzten "teils verwundet, teils verschollen" waren und so sein "Verhalten vor dem Feinde durch die Ungunst der Verhältnisse nicht anerkannt wurde" (Zit. nach Siegfried, S. 232, Fußnote 154). Sein Ansehen als Hochschullehrer und engagierter Nationalist sollte dadurch nicht geschmälert werden.

Heimwehrkontakte

Als nach dem Eingreifen der Polizei 86 Tote die Empörung der ArbeiterInnen - kumuliert im Brand des Justizpalastes - kennzeichnen, erzwingt die Heimwehr den Abbruch der sozialdemokratischen Kampfmaßnahmen und erfreut sich daraufhin der Zuwendung heterogener reaktionärer Kräfte, die Heimwehr wird (besonders bäuerliche) Massenbewegung (Siegfried, S. 81). In dieser zweiten Legislaturperiode der Regierung Seipel dominiert Spanns universalistische Lehre die Wiener Universität, sein Kreis hatte sich kontinuierlich vergrößert, nun kommt es zu intensiven Kontakten zwischen dem Führer der Christlichsozialen Partei, der Heimwehr-Führung und Mitgliedern des Spann-Kreises. Im Sommer 1929 wird Walter Heinrich Generalsekretär der Bundesführung des österreichischen Heimatschutzes, im Oktober übernimmt Hans Riehl die Leitung der Propagandaabteilung der Selbstschutzverbände (Siegfried, S. 84). Die Spannungen innerhalb der Heimwehren, unterschiedlicher Flügel, wie sie z.T. für die ÖVP charakteristisch sind, sollten durch ein Gelöbnis (Korneuburger Eid, 18. Mai 1930) beseitigt werden, dessen Text wesentlich von Walter Heinrich formuliert wurde. Der Versuch der Beschwörung der Einheit misslingt, Aristokraten siegen über kleinbürgerliche Repräsentanten der Heimwehren und beenden die Tätigkeit des Spann-Kreises in der Organisation (Siegfried, S. 100).

Versuche in Italien

Seit 1929 wenden sich Vertreter der universalistischen Lehre dem Faschismus zu, die italienische Regierung bedachte im übrigen die Heimwehren mit bedeutenden Geld- und Waffenlieferungen, den Mangel eines konkreten politischen Programms will Spann kompensieren (Zit. nach Siegfried, S. 102):

"... Das Fehlen des Gedankens vor der Tat ist ein Widerspruch... Zwischen der Szylla und Charybdis des Kommunismus und des Kapitalismus durch die kühne Tat eines einzigen Steuermannes hindurchzuschiffen, das konnte eben noch gelingen. Aber danach kann der Faschismus entweder auf das offene Meer der Abenteuer hinausfahren, wie Odysseus, oder er muß sich über Weg und Ziel aufs klarste bewußt werden, er muß eine theoretische Grundlage (im Original gesperrt) erlangen ... Der politischen Tat, so dünkt uns, muß nunmehr die geistige Arbeit folgen. War das vergangene Dezennium der Gründung und dem ersten politischen Aufbau gewidmet, so muß das kommende Dezennium der Herausarbeitung der geistigen Grundlagen und der theoretischen Vertiefung gehören. Nicht hoch genug kann u. E. diese Aufgabe angeschlagen werden. Denn die jahrhundertelange Arbeit der individualistischen und sozialistischen Theoretiker läßt sich nicht durch die politische Tat allein überwinden, es muß ihr ein tiefdurchdachtes und wohlausgebildetes Gedankengebäude auf allen Gebieten des Lebens, insbesondere des Staates, des Rechtes, der Wirtschaft, der ganzen Gesellschaft entgegengestellt werden." (Othmar Spann: Instinkt und Bewußtsein, S. 11)

Bedeutende Differenzen, besonders in Fragen des organisatorischen Aufbaus der Interessenvertretungen, trennen Spanns Konzeption von der faschistischen Syndikatsordnung, in der sich Unternehmer und Arbeiter getrennt gegenüberstehen. Das Ständemodell betont die Vorzüge gemeinsamer Zwangsverbände und die Vermittlerfunktion einer staatlichen Instanz, die selbst in der korporativen Phase des Faschismus durch die beherrschende Funktion mächtiger Monopolgruppen der italienischen Wirtschaft im Staat konträr beschrieben werden kann [Siegfried, S. 177ff). Zwar gibt es persönliche Kontakte zu führenden Funktionären des faschistischen Systems, doch die Wirkung der universalistischen Lehre bleibt gering.

Austrofaschismus

In Österreich war die Transformation der parlamentarischen Demokratie zu einem klerikalfaschistischen Ständestaat durch die Ausschaltung von Parlament und Verfassungsgerichtshof gelungen. Spann verweist auf seine "organisch universalistische Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftslehre" und betont deren Unvereinbarkeit mit demokratischen Formen der Repräsentation (Zit. nach Siegfried, S. 139):

"Die Forderung einer ständischen Ordnung hat nur Sinn, wenn ein grundsätzlicher Bruch mit allem Individualismus, Liberalismus, Kapitalismus erfolgt und auch in der praktischen Politik der Bruch mit Demokratie und Parteienstaat eingeleitet wird. Denn im organisch-ständischen Gedanken liegt, daß alle großen Lebenskreise der Gesellschaft zu arteigenen Gebilden mit arteigener (im Original gesperrt) Herrschergewalt ('Souveränität') werden. Nicht nur die Wirtschaft würde zu einem Gesamtstande, welcher in einem organisch aufgebauten System von Berufsständen (im Original gesperrt) sich selbst verwaltet und diese Selbstverwaltungsangelegenheiten dem heutigen zentralistischen Parlamente und dem heutigen, omnipotenten Staat entzieht. Auch der Staat (beziehungsweise seine politische Führung), dessen Stärke eine Lebensfrage ist, wird dadurch ein Stand." (Othmar Spann: Die politisch-wirtschaftliche Schicksalsstunde der deutschen Katholiken. In: Schönere Zukunft 7 (1931/32), S. 567)

Spanns Ausführungen gelten der Ablehnung liberaldemokratischer Verfassungen, seine Argumentation richtet sich gegen das zentrale Element der Forderung nach Gleichheit. Diese sei "die Herrschaft der Mittleren, Schlechteren, der den Schwächsten zu sich herauf, den Stärkeren herabzieht. Sofern dabei durchgängig die große Menge die Höheren herabzieht und beherrscht, in der großen Menge jedoch abermals der Abschaum zur Herrschaft drängt, drängt Gleichheit zuletzt gar auf Herrschaft des Lumpenproletariats hin" (Der wahre Staat, S. 44). In der weiteren Illustration der Modi des allgemeinen Wahlrechts muss das "politisch gänzlich unbelehrte ländliche Dienstmädchen" die männliche Qualität der "politisch wenigstens teilweise unterrichteten Staatsbürger", Handwerker oder "gehobene Arbeiter" zwangsläufig mindern, "die Stimme des akademisch Gebildeten, des politischen Führers,..." wird entwertet (ebd.).

Nationalsozialismus

1929 beginnt Spann Kontakte zu nationalsozialistischen Organisationen zu pflegen, er unterstützt die von Alfred Rosenberg 1927 gegründete Nationalsozialistische Gesellschaft für deutsche Kultur, deren Aufgabe die Begeisterung akademisch Gebildeter für die Bewegung sein soll (Siegfried, S. 153). Spann gilt in der Analyse der Arbeiterzeitung bereits 1925 als der intellektuelle Führer des Hakenkreuzlertums an der Wiener Universität, er tritt der NSDAP bei und erhält eine geheime, nicht nummerierte Mitgliedskarte (ebd.). Die Schulungsabende des Nationalsozialistischen Deutschen Studentenbundes finden in den Räumen seines Seminars statt, der Unterricht wird vom Spann-Schüler Franz Seuchter gestaltet (Siegfried, S. 153f.). In einem 1933 veröffentlichten Aufsatz bietet Spann nun dem Nationalsozialismus seine universalistische Gesellschaftslehre als ideologische Grundlage des notwendigen ständischen Aufbaus dar (Zit. nach Siegfried, S. 156f.):

"Soll die politische Wendung, die sich im Reiche vollzog, eine grundsätzliche und nicht zum Zwischenspiel, ja zum grausen Wegbereiter des Bolschewismus werden, dann muß sie sich ihrer geistigen Grundlage deutlich bewußt sein. Sie heißt: Idealismus und Universalismus. Unter dem Drucke geschichtlicher Notwendigkeit kann der erste Ansturm, die erste Tat rein instinktiv erfolgen. Je mehr es zu bestimmten Aufgaben kommt, um so mehr muß der klare Gedanke die Tat bestimmen. Was nun folgen muß, ist eine Umbildung des Staates und der Wirtschaft, eine Umbildung, wie sie der idealistische und universalistische Gedanke verlangt - im ständischen Sinn. (Othmar Spann: Die politische Wendung ist da - was nun? In: Ständisches Leben 3 (1933), S. 67)

Sein Bemühen wird von Repräsentanten der Schwerindustrie, besonders Thyssen, honoriert, der die Idee die Vertretungen der ArbeiterInnen in die Industrieverbände einzugliedern reizvoll findet und für die dahingehende Überzeugungsarbeit die Gründung eines Instituts für Ständewesen (in Düsseldorf) unterstützt. Die wissenschaftliche Leitung des am 23. Juni 1933 feierlich eröffneten Instituts übernimmt Walter Heinrich, weitere Vertreter des Spann-Kreises (Andrae, Riehl, Paul Karrenbrock) werden aktiv (Siegfried, S. 175f). Der wiederholte Ruf nach "ständischer Selbstverwaltung" läuft den Interessen und Machtpositionen der Stahlindustriellen zuwider, Unterstützungen für die Zeitschrift Ständisches Leben werden 1935 eingestellt, eine Kontroverse mit der Führung der Deutschen Arbeitsfront (DAF) führt 1936 zum Ende der Propagandatätigkeit des Spann-Kreises am Institut für Ständewesen (Siegfried, S. 186f. und 195). Spanns Ablehnung der NS-Rassentheorie trug neben seinen politischen Fehleinschätzungen zu den Disharmonien bei. Der Begriff der Nation wird in der universalistischen Gesellschaftslehre kulturell definiert, eine "geistige Gemeinschaft", die antisemitische Diskriminierung ermöglicht, nicht erfordert (Siegfried, S. 201f). Ab 1935 werden die Antagonismen der beiden faschistischen Konzeptionen in zahlreichen Zeitungsbeiträgen offensiv ausgetragen, nach der Annexion Österreichs werden Othmar Spann, Rafael Spann und Walter Heinrich verhaftet. Das daraus gebildete Konstrukt einer vorzeitigen Abkehr konservativer Kräfte vom Nationalsozialismus ohne jegliche Reflexion ihrer Funktion in der Phase der Konstituierung eröffnet rechten Parteien und Einzelpersonen die Verherrlichung bewunderter und geliebter Meister und in diesem Sinne die Relativierung des Nazisystems. Die Lehre von der Ganzheit diente der Zerschlagung demokratisch verfasster Gesellschaften, dass sie zum Dienst und nicht zur Herrschaft gelangte, liegt an den realen Kräfteverhältnissen und auch am dürftigen Angebot, das Zufriedenheit in Unterdrückungsverhältnissen fordert im Tausch gegen "Beruhigung". Die perpetuierte Distribution des Modells liegt gleichsam am Puls der Zeit, ebenso wie ein Dollfußportrait im Parlamentsbüro Khols, Wirtschafts- und Arbeitsminister Bartenstein, die ÖVP Frauenpolitik und Schwester Herbert.

1 Spann, Othmar [1931]: Der wahre Staat. Vorlesungen über Abbruch und Neubau der Gesellschaft. Jena: Fischer, S. 175. → zurück

2 Vgl., Siegfried, Klaus-Jörg [1974]: Universalismus und Faschismus. Das Gesellschaftsbild Othmar Spanns. Wien: Europa Verlag, S. 72. → zurück

3 Zit. nach Pichler, J. H. (Hrsg.)[1988]: Othmar Spann oder die Welt als Ganzes. Wien/Köln/Graz: Böhlau, S. 26ff. Dieses Werk ist Walter Heinrich posthum zugeeignet. → zurück

4 Vgl., Pichler, J. H. [1992]: Betrachtungen zum Vaterunser. Im Gedenken des 90. Geburtstages von Walter Heinrich. Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung, 36. Jg., IV/1992. → zurück

5 http://motlc.wiesenthal.com/text/x29/xm2933.html → zurück

6 Roman in autobiographischer Form, in welchem er die 131 Fragen der Entnazifizierungsbehörden dokumentieren und ad absurdum führen möchte. 1951 publiziert wurde das 800 Seiten Werk zum ersten Bestseller der BRD. → zurück

7 von Salomon, Ernst [1969]: Der Fragebogen. Reinbek bei Hamburg, S. 172. → zurück

8 Vgl. Pichler, J. Hanns [1990]: Woran könnte der Osten sich halten? Ganzheitliche Staatsidee und Wirtschaftsordnung als ein Programm der Mitte. Wiss. Arbeitskreis, Institut für Gewerbeforschung, Wien (Vortrag). ders., [1993]: Ganzheitliches Verfahren in seinem universalistisch überhöhenden Anspruch. In: Klein, H. D./Reikersdorfer, J. (Hrsg.): Philosophia perennis. Erich Heintel zum 80. Geburtstag, Teil 1, Frankfurt/Main, Berlin, Bern, New-York, Wien. → zurück

9 ders., [1999]: Europa und das Europäische. Auf der Suchen nach seiner 'Begrifflichkeit' von der Antike bis zur Neuzeit. In: Berchthold, J./Simhandl, F. (Hrsg.) [1999]: Freiheit und Verantwortung. Europa an der Jahrtausendwende. Jahrbuch für politische Erneuerung. Wien: Freiheitliche Akademie. → zurück

10 Vgl. http://www.trend.partisan.net/trd1298/t351298.html → zurück

11 Vgl. Meyer, Thomas [1997]: Stand und Klasse. Kontinuitätsgeschichte korporativer Staatskonzeptionen im deutschen Konservativismus. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag. → zurück

12 Vgl. Schneller, Martin [1970]: Zwischen Romantik und Faschismus. Der Beitrag Othmar Spanns zum Konservativismus in der Weimarer Republik. Stuttgart: Klett. → zurück

13 Resele, Gertraud [2001]: Othmar Spanns Ständestaatskonzeption und politisches Wirken. Wien (Diplomarbeit). → zurück

14 Vgl. Fischer, Kurt R./Wimmer, Franz M. (Hrsg.) [1993]: Der geistige Anschluß. Philosophie und Politik an der Universität Wien 1930-1950. Wien: WUV. Heiß, Gernot/Mattl, Siegfried/Meissl, Sebastian/Sauer, Edith, Stuhlpfarrer, Karl (Hrsg.Innen) [1989]: Willfährige Wissenschaft. Die Universität Wien 1938-1945. Wien: Verlag für Gesellschaftskritik. → zurück

15 Einer der deutschsprachigen Epigonen ist der eifrige Rezensent der Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner, der ebenso im rechtsextremen Criticon (hrsg. von Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing), Sieg oder Aula, Publikation der "Arbeitsgemeinschaft Freiheitlicher Akademikerverbände Österreichs" publiziert. Ein weiterer regelmäßiger Autor der Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung ist der katholische Antisemit Friedrich Romig, früher Europa-Beauftragter Kurt Krenns (Vgl. www.doew.at Neues von ganz rechts - April 2000), der seine antidemokratische Überzeugung gerne hinter ökologischen Bedenken verbirgt (Vgl. Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung 2 (1997), S. 71-86). → zurück |

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

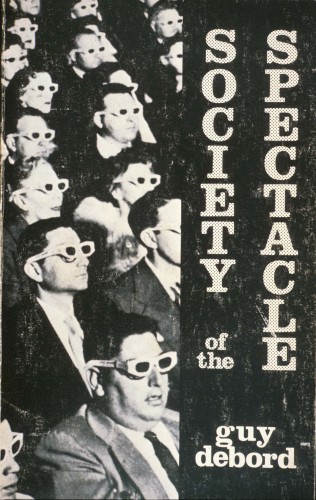

Debords Beschreibung der Totalität des Fetischismus und der Ware beginnt in unmittelbarer Anlehnung an das Marxsche "Kapital", dessen ersten Satz er paraphrasiert: "Das ganze Leben der Gesellschaften, in welchen die modernen Produktionsbedingungen herrschen, erscheint als eine ungeheure Sammlung von Spektakeln." (13) Eine explizit feststehende Definition des Begriffs Spektakel gibt Debord in seiner Schrift von 1967 nicht. Er umkreist ihn vielmehr und beschreibt ihn in seinen realen Erscheinungen und ex negativo. Im Begriff des Spektakels ist bei Debord der Begriff des Kapitals, wenn auch gegenüber der Marxschen Herleitung in vereinfachter Form, und der des Fetischismus aufgehoben: "Das Spektakel ist das Kapital in einem solchen Grad der Akkumulation, daß es zum Bild wird." (27) Er begreift das Spektakel als gesteigerte Form des Fetischismus: "Das Prinzip des Warenfetischismus ist es, (...), das sich absolut im Spektakel vollendet, wo die sinnliche Welt durch eine über ihr schwebende Auswahl von Bildern ersetzt wird, welche sich zugleich als das Sinnliche schlechthin hat anerkennen lassen." (31f.) Marx hat die Verwandlung menschlicher Beziehungen in die Beziehungen von Dingen beschrieben. Debord greift dies auf und beschreibt die Verwandlung der menschlichen Beziehungen in die Beziehung zwischen Bildern,10 die den Menschen noch äußerlicher erscheinen als die Dinge. Anders als in einigen postmodernen Diskursen hingegen, die dazu tendieren, alles in Bilder aufgelöst zu sehen, und die daher keine Realität mehr kennen, die in ihrer Gesamtheit kritisiert werden könnte, bleibt das Bild bei Debord auf die gesellschaftliche fetischistische Totalität, auf die materielle Realität rückbezogen.

Debords Beschreibung der Totalität des Fetischismus und der Ware beginnt in unmittelbarer Anlehnung an das Marxsche "Kapital", dessen ersten Satz er paraphrasiert: "Das ganze Leben der Gesellschaften, in welchen die modernen Produktionsbedingungen herrschen, erscheint als eine ungeheure Sammlung von Spektakeln." (13) Eine explizit feststehende Definition des Begriffs Spektakel gibt Debord in seiner Schrift von 1967 nicht. Er umkreist ihn vielmehr und beschreibt ihn in seinen realen Erscheinungen und ex negativo. Im Begriff des Spektakels ist bei Debord der Begriff des Kapitals, wenn auch gegenüber der Marxschen Herleitung in vereinfachter Form, und der des Fetischismus aufgehoben: "Das Spektakel ist das Kapital in einem solchen Grad der Akkumulation, daß es zum Bild wird." (27) Er begreift das Spektakel als gesteigerte Form des Fetischismus: "Das Prinzip des Warenfetischismus ist es, (...), das sich absolut im Spektakel vollendet, wo die sinnliche Welt durch eine über ihr schwebende Auswahl von Bildern ersetzt wird, welche sich zugleich als das Sinnliche schlechthin hat anerkennen lassen." (31f.) Marx hat die Verwandlung menschlicher Beziehungen in die Beziehungen von Dingen beschrieben. Debord greift dies auf und beschreibt die Verwandlung der menschlichen Beziehungen in die Beziehung zwischen Bildern,10 die den Menschen noch äußerlicher erscheinen als die Dinge. Anders als in einigen postmodernen Diskursen hingegen, die dazu tendieren, alles in Bilder aufgelöst zu sehen, und die daher keine Realität mehr kennen, die in ihrer Gesamtheit kritisiert werden könnte, bleibt das Bild bei Debord auf die gesellschaftliche fetischistische Totalität, auf die materielle Realität rückbezogen.  Die Praxis des Proletariats als revolutionäre Klasse kann für Debord "nicht weniger sein als das geschichtliche Bewußtsein, das auf die Totalität seiner Welt wirkt." (64) Damit ist aber noch nichts darüber gesagt, ob das Proletariat als real existierende und zunächst nicht besonders revolutionäre Klasse dieses geschichtliche Bewußtsein auch hat. Dennoch bleibt für Debord — zumindest noch in "Die Gesellschaft des Spektakels" — das Proletariat jene Menschengruppe, die als Klasse die Emanzipation zu verwirklichen, den Fetischismus zu durchbrechen und aufzuheben hat. Subjektiv sei das Proletariat "noch von seinem praktischen Klassenbewußtsein entfernt (...)." (102) Wenn aber das Proletariat entdeckt, "daß seine geäußerte eigene Kraft zur fortwährenden Verstärkung der kapitalistischen Gesellschaft beiträgt, (...) entdeckt es auch durch die konkrete geschichtliche Erfahrung, daß es die Klasse ist, die jeder erstarrten Äußerung und jeder Spezialisierung der Macht total feind ist." (102f.) Debord ist Ende der 60er Jahre kritisch gegenüber dem gegenwärtigen Proletariat, aber durchaus zuversichtlich für die Zukunft. Die Emanzipation wird bei ihm noch mit dem Selbstbewußtsein des Proletariats zusammengedacht. Das Proletariat erschien Debord kurz vor den Ereignissen des Pariser Mai von 1968 als "einzige(r) Bewerber um das geschichtliche Leben". (72) Erst später, in den 90er Jahren, erkannte er, auch wenn er sich von der Vorstellung vom Proletariat als Vollender der Emanzipation nicht gänzlich verabschiedete, daß die Klassenherrschaft, wie er in der Vorrede zur dritten französischen Ausgabe von "Die Gesellschaft des Spektakels" formuliert, "mit einer Versöhnung geendet hat" (8), daß also das Proletariat, statt die Feindschaft zu Staat und Kapital zu entwickeln, auf die volle Integration in das fetischistische Warenspektakel gesetzt hat und die falsche Totalität der Gesellschaft nunmehr ohne Negation, ohne Einspruch existiert. In den "Kommentaren" ist jener kritische Pessimismus, der auch die Texte anderer Gesellschaftskritiker seit dem Nationalsozialismus prägte, in potenzierter Form und mit den in solchen Zusammenhängen offensichtlich obligatorischen Übertreibungen anwesend: "Zum ersten Mal im modernen Europa versucht keine Partei oder Splittergruppe auch bloß vorzugeben, sie wolle es wagen, etwas von Belang zu ändern. (...) Es ist ein für alle Mal geschehen um jene beunruhigende Konzeption, die mehr als zweihundert Jahre vorgeherrscht hat und derzufolge man eine Gesellschaft kritisieren oder ändern, sie reformieren oder revolutionieren kann." (213)

Die Praxis des Proletariats als revolutionäre Klasse kann für Debord "nicht weniger sein als das geschichtliche Bewußtsein, das auf die Totalität seiner Welt wirkt." (64) Damit ist aber noch nichts darüber gesagt, ob das Proletariat als real existierende und zunächst nicht besonders revolutionäre Klasse dieses geschichtliche Bewußtsein auch hat. Dennoch bleibt für Debord — zumindest noch in "Die Gesellschaft des Spektakels" — das Proletariat jene Menschengruppe, die als Klasse die Emanzipation zu verwirklichen, den Fetischismus zu durchbrechen und aufzuheben hat. Subjektiv sei das Proletariat "noch von seinem praktischen Klassenbewußtsein entfernt (...)." (102) Wenn aber das Proletariat entdeckt, "daß seine geäußerte eigene Kraft zur fortwährenden Verstärkung der kapitalistischen Gesellschaft beiträgt, (...) entdeckt es auch durch die konkrete geschichtliche Erfahrung, daß es die Klasse ist, die jeder erstarrten Äußerung und jeder Spezialisierung der Macht total feind ist." (102f.) Debord ist Ende der 60er Jahre kritisch gegenüber dem gegenwärtigen Proletariat, aber durchaus zuversichtlich für die Zukunft. Die Emanzipation wird bei ihm noch mit dem Selbstbewußtsein des Proletariats zusammengedacht. Das Proletariat erschien Debord kurz vor den Ereignissen des Pariser Mai von 1968 als "einzige(r) Bewerber um das geschichtliche Leben". (72) Erst später, in den 90er Jahren, erkannte er, auch wenn er sich von der Vorstellung vom Proletariat als Vollender der Emanzipation nicht gänzlich verabschiedete, daß die Klassenherrschaft, wie er in der Vorrede zur dritten französischen Ausgabe von "Die Gesellschaft des Spektakels" formuliert, "mit einer Versöhnung geendet hat" (8), daß also das Proletariat, statt die Feindschaft zu Staat und Kapital zu entwickeln, auf die volle Integration in das fetischistische Warenspektakel gesetzt hat und die falsche Totalität der Gesellschaft nunmehr ohne Negation, ohne Einspruch existiert. In den "Kommentaren" ist jener kritische Pessimismus, der auch die Texte anderer Gesellschaftskritiker seit dem Nationalsozialismus prägte, in potenzierter Form und mit den in solchen Zusammenhängen offensichtlich obligatorischen Übertreibungen anwesend: "Zum ersten Mal im modernen Europa versucht keine Partei oder Splittergruppe auch bloß vorzugeben, sie wolle es wagen, etwas von Belang zu ändern. (...) Es ist ein für alle Mal geschehen um jene beunruhigende Konzeption, die mehr als zweihundert Jahre vorgeherrscht hat und derzufolge man eine Gesellschaft kritisieren oder ändern, sie reformieren oder revolutionieren kann." (213)

Einer wollte den Führer führen. Nein: Einige wollten den Führer führen und wirkten so im Zeichen des Führers. Ob Heidegger, Rosenberg oder Spann, die Qualität ihrer Beiträge bleibt in diesem Kontext sekundär, wenn auch im Sinne der üblichen Vorwegnahme bei Spann die Betonung auf der philosophischen Stupidität liegen kann. Ihm gelang jedoch die Formierung eines Kreises, der mehr als sechzig Jahre nach seiner eigenen Entfernung von der Universität, der heutigen WU-Wien, das Gewäsch von Ganzheit wiederholt und daneben peinlich bemüht wirkt, keinen runden Geburtstag des Meisters oder seines ersten Schülers, manchmal auch des zweiten oder folgender, zu vergessen und zumeist mit einem Presseartikel, besser mit einem Jubiläumsband zu bedenken.

Einer wollte den Führer führen. Nein: Einige wollten den Führer führen und wirkten so im Zeichen des Führers. Ob Heidegger, Rosenberg oder Spann, die Qualität ihrer Beiträge bleibt in diesem Kontext sekundär, wenn auch im Sinne der üblichen Vorwegnahme bei Spann die Betonung auf der philosophischen Stupidität liegen kann. Ihm gelang jedoch die Formierung eines Kreises, der mehr als sechzig Jahre nach seiner eigenen Entfernung von der Universität, der heutigen WU-Wien, das Gewäsch von Ganzheit wiederholt und daneben peinlich bemüht wirkt, keinen runden Geburtstag des Meisters oder seines ersten Schülers, manchmal auch des zweiten oder folgender, zu vergessen und zumeist mit einem Presseartikel, besser mit einem Jubiläumsband zu bedenken.

Por ello, si su texto La Guerra, nuestra madre escrito en 1934 ha recorrido una suerte semejante a Bagatelas para una masacre de Louis Ferdinand Céline, en el sentido de que ambos son unánimemente ”condenados” y prácticamente inencontrables a excepción de fragmentos; el joven escritor alemán, que afirmaba que: ” la voluptuosidad de la sangre flota por encima de la guerra como una vela roja sobre una galera sombría” (3), es el mismo que canta el poder de la sangre, treinta y un años después de cieno, fuego y derrota: ”los gigantescos cristales tienen forma de lanzas y cuchillos, como espadas de colores grises y violetas, cuyos filos se han templado en el ardiente soplo de fuego de fraguas cósmicas” (4).

Por ello, si su texto La Guerra, nuestra madre escrito en 1934 ha recorrido una suerte semejante a Bagatelas para una masacre de Louis Ferdinand Céline, en el sentido de que ambos son unánimemente ”condenados” y prácticamente inencontrables a excepción de fragmentos; el joven escritor alemán, que afirmaba que: ” la voluptuosidad de la sangre flota por encima de la guerra como una vela roja sobre una galera sombría” (3), es el mismo que canta el poder de la sangre, treinta y un años después de cieno, fuego y derrota: ”los gigantescos cristales tienen forma de lanzas y cuchillos, como espadas de colores grises y violetas, cuyos filos se han templado en el ardiente soplo de fuego de fraguas cósmicas” (4).