Against Transcendence: Where Progressive Education Goes Wrong

Thomas F. Bertonneau

Ex: http://peopleofshambhala.com

Modern education, taking it as an exemplary modern institution, fails, as we have seen, because it rudely repudiates the past and arrogantly proposes only to think forwards without first mastering the prerequisite skill of thinking, and therefore also of understanding, backwards. The essential fact about thinking backwards is that, before the subject begins his movement towards mastery, he must acquire the requisite tools for doing so on faith; in other words, education being a movement from ignorance to knowledge, it can never justify itself in advance, but requires of the learner the equivalent of discipleship or wagering. The learner must accept any number of premises and procedural formulas without understanding them, but on the understanding that those who have gone down the path before him have found them necessary and useful.

My present thesis is related to my previous thesis, which was that “when higher education – or any phase of education – repudiates faith it repudiates its own character as education, the structure of education being identical with the structure of faith.” I wish now to argue, while continuing the critique of the modern mentality carried out under that earlier thesis, that the structure of reality is the same as the structure of revelation, and when institutions repudiate revelation they repudiate their own raison-d’être, which is to constitute a meaningful human response to reality.

Because modernity rejects faith, it also rejects revelation. It assigns revelation to the genre of religion, against which, to protect itself from what it regards as a bane, deadly to its reason and secularity, it raises a vehemently guarded cordon sanitaire. An anecdote will suggest the degree of this vehemence and the glee with which it expresses itself. The philosophy faculty of the college that employs me annually hosts an endowed lecture the purpose of which is to bring to campus someone currently feted by the philosophical community for his or her outstanding, or at any rate notable, work. Some few years ago the invitation went to Dr. Eugenie Scott, director of the National Center for Science Education, whose mission entails standing vigilance over any attempt by “Creationists” and “Intelligent Design” advocates, those nemeses of Enlightenment, to infiltrate education. That particular year, the orator was celebrating the NCSE’s then-recent legal victory (Kitzmiller v. Dover, 2005) against the “Creationist” and “Intelligent Design” menace in Pennsylvania.

In an auditorium before the entire Philosophy faculty, representatives of numerous other faculties, and no small number of enthusiastic undergraduates, the much-anticipated speaker repeatedly earned herself rounds of robust applause for rehearsing in detail two specifics of the legal outcome that the NCSE’s lawsuit had forced. First, she and the NCSE had gotten a judge (yes, a judge) to decide what science is (applause); second, in consequence of this decision, a library came under compulsion to remove a particular book from the shelves (applause). The complementary Power-Point presentation to the talk incorporated a graphic component that began as a plain map of the United States across which in sequence little fires began to appear – the Beltane orgies of “Creationism” and “Intelligent Design.” This digital gimmick also earned an energetic outburst of hand-clapping.

The rule of irony never to explain itself will perhaps not suffer unduly by a temporary suspension, just for one paragraph. The occasion in honor of the intellectual crusader, sponsored by a faculty of professional rationalists, resembled nothing so much as Revivalist anti-liquor meeting or a Blue-Stocking rally to keep that wicked pool hall out of town. One half-expected a hysterical penitent to emerge from the audience, throw himself at the good doctor’s feet, and confess out loud that he had once fleetingly felt up the heresy – whereupon might he please receive absolution from “Sister Science” for his sin? That the audience could not see itself in such a light suggests that its constituent members had descended from intellectual commitment to a set of propositions, whose persuasiveness they would still be willing to debate, to emotive espousal of a Manichaean dispensation that consists only of true-believers in the righteous cause and the great unwashed. And yet insofar as those who applaud the authorization of judges to decide the scientific validity of claims are, indeed, modern liberals – that is to say, people who participate eagerly in the “deconstruction” of inherited, as they see it, falsehood – then they, themselves, are “Creationists.”

No one, after all, can deconstruct what has not previously been constructed. Modern liberals are also conformists, unable to resist peer pressure. On the occasion of the homiletic against “Creationism,” only two people in the auditorium withheld their approbation.

True, the reality in respect of which modern liberals are “Creationists” is the cultural, not the cosmological, reality; but it is precisely the cultural reality that most urgently concerns human beings – who over the millennia of their ongoing survival-experiment have created the webs of meaning that, if they never abrogated the cosmological reality, nevertheless stood in considerable tension with it, acknowledging that reality while enabling their creators to overcome the base elements of their animal nature through experience of the tension. Modern liberals thus concede that culture is a transfiguring artifact. They insist at the same time that nature is uncreated or that it is self-creating, but peculiarly they remain extremely reluctant to admit that the uncreated or self-creating nature is non-deconstructable. They treat nature as though it was the same as culture although of course their theory of culture (“constructivism”) remains defective because it has no anchor in the concept of a self-stabilizing reality. Modern liberals wish not to acknowledge that the nature, to which culture adapts itself, always by degrees of comparable failure or success, is fixed such that its structure precludes abrogation. If modern liberals acknowledged that fact, which would entail acknowledging that there is a non-abrogatable, human nature, then their argument that culture is generically so plastic that people may construct it or deconstruct it as they please would become dubious, even untenable.

The uncreated or self-creating, but nevertheless fixed nature, one aspect of which modern liberals celebrate and another aspect of which they elide, has a peculiar relation to the human intelligence that attempts to understand and respond to it. Either actively or passively that reality makes a demand. It reveals itself, as it is and what it is, whether or not the apprehending subject-consciousness approves of its quiddity or not; and concerning the subject-consciousness’s approval, in fact, that same external and objective “is-ness” remains cold and oblivious, declaring itself without apology. Like the river in the Jerome Kern song, it just keeps rollin’ along. The uncreated or self-creating, but nevertheless fixed nature is thus functionally the equivalent of absolute nonnegotiable revelation, as invoked by religion. That, incidentally, is how philosophy has seen it – from the Pre-Socratics to the Platonists, and, once again, from the Neo-Platonists and their Christian successors, right up to the incipiently Post-Christian Transcendentalists. I return to my thesis: That the structure of reality is the same as the structure of revelation, and when institutions repudiate revelation they repudiate their own raison-d’être, which is to constitute a meaningful human response to reality.

The philosopher of politics and history Eric Voegelin (1901 – 1985) argued his impressive original of my own entirely dependent thesis in his massive study of Order and History (begun in 1956, carried forward in five volumes through to the 1980s). In Volume I of the series, Israel and Revelation, Voegelin began famously by observing the paradox that “the order of history emerges from the history of order”: That is, humanity comes to terms with the world, including itself, forwards, by what Voegelin calls the “symbolization of truth”; but only backwards, historically, will a later society be able to sort out and re-codify the cumulus of symbolizations “adequately,” thereby arriving at an “intelligible structure.” Voegelin argues, however, that the beginning of the process, where symbolization remains “compact,” and the later discernment of the “intelligible structure,” have the same revelatory, and in context the same entirely valid, character. Hesiod’s cosmo-theology in his Theogony would thus be as valid an attempt to come into “attunement” with reality as Heraclitus’ Logos of three hundred years later. That the Logos-philosophy is also an advance over the Theogony, a movement from compactness to articulation, never undoes Hesiod’s achievement

The philosopher of politics and history Eric Voegelin (1901 – 1985) argued his impressive original of my own entirely dependent thesis in his massive study of Order and History (begun in 1956, carried forward in five volumes through to the 1980s). In Volume I of the series, Israel and Revelation, Voegelin began famously by observing the paradox that “the order of history emerges from the history of order”: That is, humanity comes to terms with the world, including itself, forwards, by what Voegelin calls the “symbolization of truth”; but only backwards, historically, will a later society be able to sort out and re-codify the cumulus of symbolizations “adequately,” thereby arriving at an “intelligible structure.” Voegelin argues, however, that the beginning of the process, where symbolization remains “compact,” and the later discernment of the “intelligible structure,” have the same revelatory, and in context the same entirely valid, character. Hesiod’s cosmo-theology in his Theogony would thus be as valid an attempt to come into “attunement” with reality as Heraclitus’ Logos of three hundred years later. That the Logos-philosophy is also an advance over the Theogony, a movement from compactness to articulation, never undoes Hesiod’s achievement

Voegelin sees the human situation as “paradoxical.” The reality that becomes a phenomenon, literally a shining-forth, for consciousness is, on the one hand, “a datum of experience insofar as it is known to man by virtue of his participation in the mystery of its being”; but it is also “not a datum of experience insofar as it is not given in the manner of an object of the external world but is knowable only from the perspective of participation in it.”

It belongs to Voegelin’s theory that societies form themselves according to a powerful founding vision, each of which constitutes a “leap in being” for consciousness, as it develops along the axis of history. It so happens that the earliest self-articulating and self-reporting societies, the ones that began to put themselves in evidence at the cusp of the Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages, drew their institutional structure from the powerful impression made by the heavens on human observation. These are the “cosmological societies,” based on what Voegelin calls “the cosmological myth,” familiar from the examples of Mesopotamia and Egypt but found also in the Far East and in Meso-America. Voegelin remarks importantly that “the cosmological myth arises in a… number of civilizations without apparent mutual influences.” Wherever the myth appears and forms the basis of the subsequent society, the experience that gives rise to it is the same, and this generic homogeneity suggests that the experience is objective, not an arbitrary fantasy of some gullible subject.

In Israel and Revelation Voegelin writes, “The cosmological myth… is [a] symbolic form created by societies when they rise above the level of tribal organization.” But what specifically is the “cosmological myth”? It is the discovery and the subsequent symbolization of order in the celestial realm, taken as the unavoidable model for a reorganization of life in the human realm. “When man creates the cosmion [the little cosmos] of political order, he analogically repeats the divine creation of the cosmos.” More than that, however, as Voegelin explains, “the analogical repetition is not an act of futile imitation.” Rather, the repetition is creative and arises from the intuition of “participating in the creation of order.” The repetition is furthermore conditioned by humanity’s “existential limitations.” Implicit in the emergence of the cosmological societies is the discovery of a human nature which must find “attunement” with cosmic nature. “Attunement” is necessary because the cosmic reality that reveals itself to emerging consciousness is an inalterable quiddity that makes a demand. Human nature is also an inalterable quiddity that makes a demand.

According to Voegelin, symbolization even in its early stages is aware of itself, as symbolization. The symbol-makers consciously attempt to know the directly unknowable by way of analogy; they thus concede that something exists beyond the horizon of empirical knowledge that indubitably is while at the same time remaining a mystery, which men at best can only adumbrate, and yet to which they must maintain orientation. As Voegelin puts it in his analysis of Mesopotamian myth, “Cosmological symbolization is neither a theory nor an allegory”; but rather “it is the… expression of the participation, experienced as real, of the order of society in the divine being that also orders the cosmos.” Voegelin remarks that differences in symbolization never bothered the Mesopotamians of the contending city-kingdoms, who were capable of seeing that the other city’s gods were functionally and therefore essentially the same as their own; in the hydraulic empires there existed a noteworthy understanding of symbolic equivalency. The image of extravagant spoils would have been thoroughly familiar to the Erechites, but the notion of a religious war would have struck them as nonsense.

When in The World of the Polis (1957) Voegelin turns his attention from the Near East, Egypt, and Israel to Hellenic civilization, he discovers a unique “leap in being” beyond the symbolism of cosmological compactness, but he cautions that the Greek insight into the structure of reality must not be characterized as abolishing the older insight. The “leap in being” is not “progress,” understood in the modern, parochial sense; rather it absorbs the previous insight, without which it could not have sprung into existence. Voegelin writes, “The philosopher must beware of the fallacy of transforming the consciousness of an unfolding mystery into the gnosis of progress in time” although that is typically what modern thinkers do when they invoke the “ultimacy” of their doctrines, “for such absolutism… involve[s] us in the Gnostic fallacy of declaring the end of history.” Try to imagine any modern discourse without its Greek vocabulary. It is impossible. Modern people, despite their rejection of transcendence, still live in the reality opened up by the Ionian “leap in being,” but they are less and less able to penetrate that reality.

At the dawn of the Hellenic consciousness, which is also the dawn of Western consciousness, Voegelin places “the prophetic singers who experienced man in his immediacy under the gods; who articulated the gulf between the misery of the mortal condition and the glory of memorable deeds, between human blindness and divine wisdom, and who created the paradigms of noble action as guides for men who desired to live by memory.” Hesiod never arrived at his idea of order by induction, nor did he deduce it syllogistically; he experienced it in the spontaneously self-organizing vision on Helicon that he reports in rich detail in the Invocatio of the Theogony. That experience enabled Hesiod to find the previously concealed order in the chaotic mass of inherited lore about the world and the gods, to be the organizing voice of which the Muses had nominated him.

The later philosophical development of the Homeric-Hesiodic theo-anthropology, whose earliest manifestation comes with Parmenides and Heraclitus, also originates in intuitions of order that deserve the epithet of prophetic. Concerning Heraclitus, Voegelin insists on the “deliberateness and radicalism” of his inquiry. Heraclitus discovered nothing less than a new dimension of human nature, the daimon or soul, the faculty wherewith the subject kens the sophon or wisdom in reality and comes into transcendent communion with the Logos. The Logos meanwhile is the principle that establishes the Order of Being; and which, one of the surviving fragments says, both does and does not wish to be called by the name of Zeus. According to Voegelin, while Heraclitus carried on the speculation of the Milesian physicists, and while his book must have included a cosmology, the Heraclitean Being should not be confused with the cosmos, which functions as its signifier in the constitution of the great sign. The Heraclitean Being is a level of order transcending the cosmos of mere things.

In Voegelin’s view, Heraclitus’ subordination of cosmology to ontology adds up to a towering achievement. Heraclitus, writes Voegelin, “speaks of the Logos, meaning his discourse; but this Logos is at the same time a sense or meaning, existing from eternity, whether proclaimed by the… literary Logos or not.” Unless cosmology were animated by the reservoir of meaning that the soul senses as lying beyond the congeries of mere things, its inquiry would be a futile activity; cosmology would be an endeavor of description without orientation or purpose. In Heraclitus’ vision, Voegelin continues, “the cosmos… is nature in the Milesian sense and, at the same time, it is the manifestation of the invisible, universal divinity; it is a universe given to the senses and, at the same time, the ‘sign’ of the invisible God.” Two thousand years later, Johannes Kepler sustained the same conviction, as his Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596) attests. To restate the first part of my thesis: The structure of reality is the same as the structure of revelation

These surveillances permit a re-visitation of the event that I discussed at the beginning of the present essay, the public lecture, sponsored by a university Philosophy faculty, during which the lecturer garnered plaudits for insisting that the cosmos is non-intentional and that those who would impute intentionality to it are destroyers of science whom the law should suppress. What a descent from Herr Kepler! What a descent from Heraclitus! But we must check ourselves. The guardians of scientific orthodoxy including the vigilant all-sniffing lady-proboscis, not to mention the Philosophy faculty of a state university and many faculty-members from other departments, are all more intelligent, perceptive, and educated than the gnomic Ephesian or his star-gazing spiritual descendant of the Reformation. They are critical thinkers. The present, being the culmination of progress, obviously possesses of a type of knowledge unavailable to the benighted ages, whose mentality at whatever degree of articulation modernity has obviated. Modernity disdains to call this superlative knowledge, held in absolute certainty, truth, because it rejects the concept of truth, but it nevertheless believes what it believes with adamant conviction.

The knowledge which scientistic Puritanism so aggressively publishes, and which the Philosophy faculty so vigorously applauds, is a peculiar but typically modern species of knowledge. It is less a positive assertion of anything than it is a denial or, better yet, a denunciation of a longstanding prior assertion, and as such its character is largely if not entirely negative. Such knowledge is not sufficient by itself, offering its theses for impartial examination, but rather it requires a public performance to validate it. It must sweep up the crowd into a mood of unanimity. Such a performance, its rationalistic appurtenances notwithstanding, is essentially a cultic ritual: The spokeswoman’s presentation corresponded to an archaic exorcism, whose action banishes the smut of profanation from the boundaries of the community. And what specific bane fell under banishment? “Creationism,” according to the organization’s website, “refers to the religious belief in a supernatural deity or force that intervenes, or has intervened, directly in the physical world.” In sum, matter, in its uncreated purity, must never be contaminated by spirit. But why should an inversion of the classic Gnosticism, which remains Gnostic for all that it is an inversion, be a requirement?

The knowledge which scientistic Puritanism so aggressively publishes, and which the Philosophy faculty so vigorously applauds, is a peculiar but typically modern species of knowledge. It is less a positive assertion of anything than it is a denial or, better yet, a denunciation of a longstanding prior assertion, and as such its character is largely if not entirely negative. Such knowledge is not sufficient by itself, offering its theses for impartial examination, but rather it requires a public performance to validate it. It must sweep up the crowd into a mood of unanimity. Such a performance, its rationalistic appurtenances notwithstanding, is essentially a cultic ritual: The spokeswoman’s presentation corresponded to an archaic exorcism, whose action banishes the smut of profanation from the boundaries of the community. And what specific bane fell under banishment? “Creationism,” according to the organization’s website, “refers to the religious belief in a supernatural deity or force that intervenes, or has intervened, directly in the physical world.” In sum, matter, in its uncreated purity, must never be contaminated by spirit. But why should an inversion of the classic Gnosticism, which remains Gnostic for all that it is an inversion, be a requirement?

If the universe had an author, if it were created rather than uncreated, its structure would be authoritative; its order would be that of an intentional and immutable creation whereupon all modern utopian schemes that depend on the premise that nature may be deconstructed and reconstructed however one likes would appear in the fullness of their common petulant impossibility. The scientistic assault on Transcendence resembles what Voegelin, in The Ecumenic Age (1965), identifies as the Gnostic rebellion against reality. Because a certain type of mentality responds to any limitation, including the natural limitations, with irrational resentment, the entirety of nature can become an object of rage and vituperation. The quintessentially modern campaign of de-symbolization is tantamount to the new creation of an illusory but comforting “second reality” in which the limitations inherent in the Order-of-Being disappear and men begin, as they believe, to correct the intolerable structure of reality. I end by reiterating and slightly modifying the second part of my thesis: When institutions repudiate revelation, which is the same as the Order of Being, they repudiate their own raison-d’être, which is to constitute a meaningful human response to reality.

Thomas F. Bertonneau earned a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of Califonia at Los Angeles in 1990. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at SUNY Oswego since 2001. He is the author of three books and numerous articles on literature, art, music, religion, anthropology, film, and politics. He is a frequent contributor to Anthropoetics, the ISI quarterlies, and others.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Ces considérations sont prégnantes dans les mouvements de droite, aussi bien classiques que populistes, même si ces derniers les assument beaucoup plus aisément, notamment en Grande-Bretagne avec UKIP, en Belgique avec le Parti Populaire, ou en Suède avec les Démocrates Suédois. Le fait de rompre un tel tabou et de rouvrir le débat sur la coexistence des civilisations facilite leur classement à l’extrême-droite. Pourtant, les problématiques issues de la coexistence ne sont pas liées aux pays de l’Europe blanche et chrétienne. Une enquête réalisée par Ipsos en 2011 révèle que ce phénomène touche aussi aux autres continents, il s’agit d’un phénomène inhérent à l’être humain, il est donc universel.

Ces considérations sont prégnantes dans les mouvements de droite, aussi bien classiques que populistes, même si ces derniers les assument beaucoup plus aisément, notamment en Grande-Bretagne avec UKIP, en Belgique avec le Parti Populaire, ou en Suède avec les Démocrates Suédois. Le fait de rompre un tel tabou et de rouvrir le débat sur la coexistence des civilisations facilite leur classement à l’extrême-droite. Pourtant, les problématiques issues de la coexistence ne sont pas liées aux pays de l’Europe blanche et chrétienne. Une enquête réalisée par Ipsos en 2011 révèle que ce phénomène touche aussi aux autres continents, il s’agit d’un phénomène inhérent à l’être humain, il est donc universel.

Le nom de Philippe Baillet ne vous est peut-être pas inconnu : il est le traducteur français de Julius Evola mais également l’auteur de nombre d’articles et de quatre autres livres. Le parti de la vie se compose justement de huit de ses études, certaines déjà publiées, d’autres considérablement enrichies par rapport à leur première version. Deux d’entre elles (sur Yukio Mishima et Giorgio Locchi dont un texte inédit en français se trouve d’ailleurs en annexe) sont inédites.

Le nom de Philippe Baillet ne vous est peut-être pas inconnu : il est le traducteur français de Julius Evola mais également l’auteur de nombre d’articles et de quatre autres livres. Le parti de la vie se compose justement de huit de ses études, certaines déjà publiées, d’autres considérablement enrichies par rapport à leur première version. Deux d’entre elles (sur Yukio Mishima et Giorgio Locchi dont un texte inédit en français se trouve d’ailleurs en annexe) sont inédites.

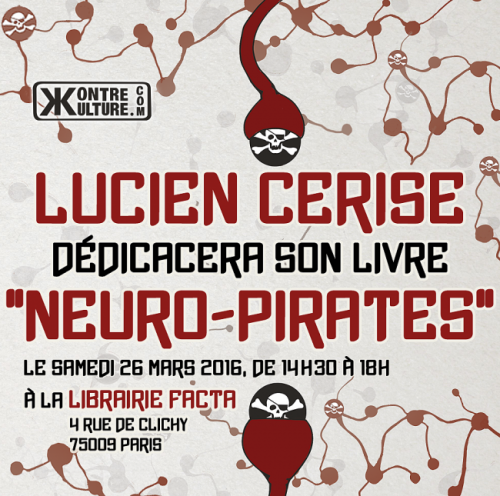

Dans les années 60, Mc Luhan écrivait : « Les guerres chaudes du passé se faisaient au moyen d’armes qui abattaient l’ennemi homme par homme. Même les guerres idéologiques consistaient au XVIII° et XIX° siècle à convaincre les individus un par un d’adopter un nouveau point de vue. La persuasion électrique par la photographie, le cinéma et la télévision consiste, au contraire, à plonger des populations tout entières dans une nouvelle imagerie. »

Dans les années 60, Mc Luhan écrivait : « Les guerres chaudes du passé se faisaient au moyen d’armes qui abattaient l’ennemi homme par homme. Même les guerres idéologiques consistaient au XVIII° et XIX° siècle à convaincre les individus un par un d’adopter un nouveau point de vue. La persuasion électrique par la photographie, le cinéma et la télévision consiste, au contraire, à plonger des populations tout entières dans une nouvelle imagerie. »

Exit donc Clinton. Resteront en lice Donald Trump et Bernie Sanders, chacun d'eux pouvant susciter des dizaines de millions de votes favorables. Sanders fera probablement une remontée remarquable au sein du parti démocrate, mais il sera probablement et pour cette raison en butte à l'hostilité de ce qui en Amérique rejette l'idée même de ce que l'on appelle en Europe la social- démocratie, à plus forte raison si elle est orientée à gauche. Sanders aura contre lui tout l'appareil politique des conservateurs et néo-conservateurs, des maîtres de Wall Street et sans doute d'une partie des militaires. L'establishment démocrate préféra perdre les élections que se rallier à lui.

Exit donc Clinton. Resteront en lice Donald Trump et Bernie Sanders, chacun d'eux pouvant susciter des dizaines de millions de votes favorables. Sanders fera probablement une remontée remarquable au sein du parti démocrate, mais il sera probablement et pour cette raison en butte à l'hostilité de ce qui en Amérique rejette l'idée même de ce que l'on appelle en Europe la social- démocratie, à plus forte raison si elle est orientée à gauche. Sanders aura contre lui tout l'appareil politique des conservateurs et néo-conservateurs, des maîtres de Wall Street et sans doute d'une partie des militaires. L'establishment démocrate préféra perdre les élections que se rallier à lui.

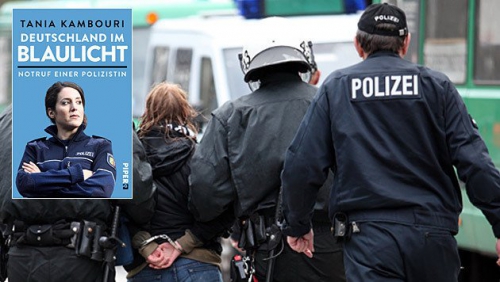

La lettre de lecteur de Tania Kambouri fut très bien accueillie par ses collègues, ce qui l’incita à décrire ses expériences professionnelles dans un livre intitulé «Deutschland im Blaulicht – Notruf einer Polizistin» [L’Allemagne et les gyrophares – Appel d’urgence d’une policière]. Prenant des situations quotidiennes vécues dans son travail de policière sur le terrain, par exemple les parcages non autorisés, des disputes, des prises aux mains ou des contrôles d’identités, cette femme de 33 ans constate que les règles fondamentales d’un ordre libéral et démocratique sont de moins en moins respectées et cela particulièrement par des groupes de migrants. Ces gens ne reconnaissent pas la police comme représentante de la force publique mais y voient leurs ennemis. De ce fait, les policiers sont de plus en plus empêchés d’accomplir leurs missions et doivent craindre d’être victimes de violences. Il n’est plus question d’imposer le droit. Du coup, on observe des espaces de non-droit dans lesquels ce ne sont plus les lois qui régissent, mais la loi du plus fort.

La lettre de lecteur de Tania Kambouri fut très bien accueillie par ses collègues, ce qui l’incita à décrire ses expériences professionnelles dans un livre intitulé «Deutschland im Blaulicht – Notruf einer Polizistin» [L’Allemagne et les gyrophares – Appel d’urgence d’une policière]. Prenant des situations quotidiennes vécues dans son travail de policière sur le terrain, par exemple les parcages non autorisés, des disputes, des prises aux mains ou des contrôles d’identités, cette femme de 33 ans constate que les règles fondamentales d’un ordre libéral et démocratique sont de moins en moins respectées et cela particulièrement par des groupes de migrants. Ces gens ne reconnaissent pas la police comme représentante de la force publique mais y voient leurs ennemis. De ce fait, les policiers sont de plus en plus empêchés d’accomplir leurs missions et doivent craindre d’être victimes de violences. Il n’est plus question d’imposer le droit. Du coup, on observe des espaces de non-droit dans lesquels ce ne sont plus les lois qui régissent, mais la loi du plus fort.

Le voyageur en classe affaires dispose d'une échappatoire : il peut se réfugier dans les salons privés qui lui sont réservés. « On y propose de jouir du silence comme d'un produit de luxe. Dans le salon "affaires" de Charles-de-Gaulle, pas de télévision, pas de publicité sur les murs, alors que dans le reste de l'aéroport règne la cacophonie habituelle. Il m'est venu cette terrifiante image d'un monde divisé en deux : d'un côté, ceux qui ont droit au silence et à la concentration, qui créent et bénéficient de la reconnaissance de leurs métiers ; de l'autre, ceux qui sont condamnés au bruit et subissent, sans en avoir conscience, les créations publicitaires inventées par ceux-là mêmes qui ont bénéficié du silence... On a beaucoup parlé du déclin de la classe moyenne au cours des dernières décennies ; la concentration croissante de la richesse aux mains d'une élite toujours plus exclusive a sans doute quelque chose à voir avec notre tolérance à l'égard de l'exploitation de plus en plus agressive de nos ressources attentionnelles collectives. »

Le voyageur en classe affaires dispose d'une échappatoire : il peut se réfugier dans les salons privés qui lui sont réservés. « On y propose de jouir du silence comme d'un produit de luxe. Dans le salon "affaires" de Charles-de-Gaulle, pas de télévision, pas de publicité sur les murs, alors que dans le reste de l'aéroport règne la cacophonie habituelle. Il m'est venu cette terrifiante image d'un monde divisé en deux : d'un côté, ceux qui ont droit au silence et à la concentration, qui créent et bénéficient de la reconnaissance de leurs métiers ; de l'autre, ceux qui sont condamnés au bruit et subissent, sans en avoir conscience, les créations publicitaires inventées par ceux-là mêmes qui ont bénéficié du silence... On a beaucoup parlé du déclin de la classe moyenne au cours des dernières décennies ; la concentration croissante de la richesse aux mains d'une élite toujours plus exclusive a sans doute quelque chose à voir avec notre tolérance à l'égard de l'exploitation de plus en plus agressive de nos ressources attentionnelles collectives. »

C'était, concède tout de même le philosophe dans sa relecture (radicale, elle aussi) des Lumières, une étape nécessaire, pour se libérer des entraves imposées par des autorités qui, comme disait Kant, maintenaient l'être humain dans un état de « minorité ». Mais les temps ont changé. « La cause actuelle de notre malaise, ce sont les illusions engendrées par un projet d'émancipation qui a fini par dégénérer, celui des Lumières précisément. » Obsédés par cet idéal d'autonomie que nous avons mis au coeur de nos vies, politiques, économiques, technologiques, nous sommes allés trop loin. Nous voilà enchaînés à notre volonté d'émancipation.

C'était, concède tout de même le philosophe dans sa relecture (radicale, elle aussi) des Lumières, une étape nécessaire, pour se libérer des entraves imposées par des autorités qui, comme disait Kant, maintenaient l'être humain dans un état de « minorité ». Mais les temps ont changé. « La cause actuelle de notre malaise, ce sont les illusions engendrées par un projet d'émancipation qui a fini par dégénérer, celui des Lumières précisément. » Obsédés par cet idéal d'autonomie que nous avons mis au coeur de nos vies, politiques, économiques, technologiques, nous sommes allés trop loin. Nous voilà enchaînés à notre volonté d'émancipation.

Ce dernier semble avoir mal assimilé l’opposition « Europe vs Occident » de la Nouvelle Droite française dont il tenta d’être le représentant en Russie, l’amenant à adopter des positions très ambigües concernant l’islam. On a souvent prêté à Douguine une influence déterminante sur Vladimir Poutine mais ce dernier n’a joué des thèmes eurasistes que pour provoquer une Europe dont il a espéré le soutien pendant longtemps et dont il désespère de la voir se soumettre sans pudeur aux USA en adoptant par ailleurs une politique migratoire et morale absolument suicidaire. Douguine également a apporté un soutien sans mesure aux sécessionnistes du Donbass, ce qui est aussi erroné selon moi que d’apporter un soutien aux supplétifs nationalistes ukrainiens de Soros, car tout ce qui divise l’Europe, et donc l’Ukraine, sert les intérêts géo-stratégiques américains.

Ce dernier semble avoir mal assimilé l’opposition « Europe vs Occident » de la Nouvelle Droite française dont il tenta d’être le représentant en Russie, l’amenant à adopter des positions très ambigües concernant l’islam. On a souvent prêté à Douguine une influence déterminante sur Vladimir Poutine mais ce dernier n’a joué des thèmes eurasistes que pour provoquer une Europe dont il a espéré le soutien pendant longtemps et dont il désespère de la voir se soumettre sans pudeur aux USA en adoptant par ailleurs une politique migratoire et morale absolument suicidaire. Douguine également a apporté un soutien sans mesure aux sécessionnistes du Donbass, ce qui est aussi erroné selon moi que d’apporter un soutien aux supplétifs nationalistes ukrainiens de Soros, car tout ce qui divise l’Europe, et donc l’Ukraine, sert les intérêts géo-stratégiques américains.

Il y a par conséquent une béance profonde fondamentale entre un soi-disant décroissant et le père de la décroissance en France. Serge Latouche prévient que « le “ bougisme ”, la manie de se déplacer toujours plus loin, toujours plus vite, toujours plus souvent (et pour toujours moins cher), ce besoin largement artificiel créé par la vie “ surmoderne ”, exacerbé par les médias, sollicité par les agences de voyages, les voyagistes et les tour-opérateurs, doit être revu à la baisse (6) ».

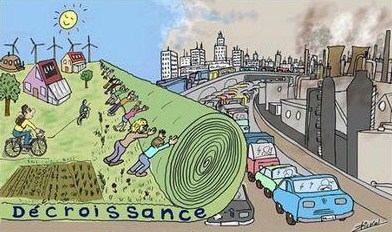

Il y a par conséquent une béance profonde fondamentale entre un soi-disant décroissant et le père de la décroissance en France. Serge Latouche prévient que « le “ bougisme ”, la manie de se déplacer toujours plus loin, toujours plus vite, toujours plus souvent (et pour toujours moins cher), ce besoin largement artificiel créé par la vie “ surmoderne ”, exacerbé par les médias, sollicité par les agences de voyages, les voyagistes et les tour-opérateurs, doit être revu à la baisse (6) ». Il manque encore à la décroissance tout une dimension politique et stratégique. De nombreux décroissants raisonnent toujours à l’échelle de leur potager dans le « village global » interconnecté alors que la raréfaction croissante des ressources inciterait à envisager au contraire une société fermée, qu’elle soit nationale ou bien continentale dans le cadre de l’« Europe cuirassée » chère à Maurice Bardèche. En effet, « c’est […] bien une société de rupture qu’il faut ambitionner, annonce l’anarcho-royaliste français Rodolphe Crevelle, quitte à mépriser tous les clivages politiques antérieurs, quitte à paraître donquichottesque ou ridicule, ou rêveur, ou utopique… (13) ». Nourris par les traductions anglaises des écrits de l’écologiste radical finlandais Pentti Linkola dans lesquels se conjuguent écologie, décroissance et puissance militaire, Rodolphe Crevelle et son équipe du Lys Noir soutiennent une vision singulière de l’« écolo-décroissance ». « La préservation de l’Homme ancien “ dans un seul pays d’abord ”, ouvre la perspective d’un isolat forteresse assiégé parce que celui-ci constituera le mauvais exemple, le mouton noir du monde, un démenti à la “ fête ” globale planétaire (14). » Certes, « il faut […] convenir que l’autarcie est une question d’échelle. Elle est particulièrement difficile à instaurer dans un petit pays sans diversité économique, elle est plus facile à supporter dans une grande économie diversifiée. Et on peut même affirmer que l’autarcie à l’échelle d’un continent riche peut compter aujourd’hui sur quelques défenseurs (15) ». Ils estiment non sans raison que « la France possède tous les moyens technologiques et humains de l’autarcie. Elle est même pratiquement un des seuls pays au monde à pouvoir organiser volontairement son propre embargo ! (16) ». « L’écologie extrême […] est notre dernière chance de discipline collective et d’argumentation des interdits, insiste Rodolphe Crevelle (17) ».

Il manque encore à la décroissance tout une dimension politique et stratégique. De nombreux décroissants raisonnent toujours à l’échelle de leur potager dans le « village global » interconnecté alors que la raréfaction croissante des ressources inciterait à envisager au contraire une société fermée, qu’elle soit nationale ou bien continentale dans le cadre de l’« Europe cuirassée » chère à Maurice Bardèche. En effet, « c’est […] bien une société de rupture qu’il faut ambitionner, annonce l’anarcho-royaliste français Rodolphe Crevelle, quitte à mépriser tous les clivages politiques antérieurs, quitte à paraître donquichottesque ou ridicule, ou rêveur, ou utopique… (13) ». Nourris par les traductions anglaises des écrits de l’écologiste radical finlandais Pentti Linkola dans lesquels se conjuguent écologie, décroissance et puissance militaire, Rodolphe Crevelle et son équipe du Lys Noir soutiennent une vision singulière de l’« écolo-décroissance ». « La préservation de l’Homme ancien “ dans un seul pays d’abord ”, ouvre la perspective d’un isolat forteresse assiégé parce que celui-ci constituera le mauvais exemple, le mouton noir du monde, un démenti à la “ fête ” globale planétaire (14). » Certes, « il faut […] convenir que l’autarcie est une question d’échelle. Elle est particulièrement difficile à instaurer dans un petit pays sans diversité économique, elle est plus facile à supporter dans une grande économie diversifiée. Et on peut même affirmer que l’autarcie à l’échelle d’un continent riche peut compter aujourd’hui sur quelques défenseurs (15) ». Ils estiment non sans raison que « la France possède tous les moyens technologiques et humains de l’autarcie. Elle est même pratiquement un des seuls pays au monde à pouvoir organiser volontairement son propre embargo ! (16) ». « L’écologie extrême […] est notre dernière chance de discipline collective et d’argumentation des interdits, insiste Rodolphe Crevelle (17) ». Avec des frontières réhabilitées, sans la moindre porosité et grâce à des gardiens vigilants, dénués de remords, la société fermée décroissante adopterait vite la notion de puissance afin de tenir à distance un voisinage plus qu’avide de s’emparer de ses terres et de ses biens. Elle pratiquerait une nécessaire auto-suffisance tant alimentaire qu’énergétique. Mais cette voie vers l’autarcie salutaire risque de ne pas aboutir si la population n’entreprend pas d’elle-même une révolution culturelle et un renversement complet des consciences. « Outre l’autarcie économique européenne, il faudrait mieux encore parler d’autarcie technique, d’auto-isolement sanitaire; d’un refus de courir plus loin et plus vite vers le précipice, vers le monde de “ science-fiction contemporaine ” qui s’est installé sur toute la planète dans la plus parfaite soumission des gauchistes et des conservateurs (18). » L’auto-subsistance vivrière deviendra un atout considérable en périodes de troubles politiques et socio-économiques. « Tant que la perspective d’un soulèvement populaire signifiera pénurie certaine de soins, de nourriture ou d’énergie, il n’y aura pas de mouvement de masse décidé, prévient le Comité invisible. En d’autres termes : il nous faut reprendre un travail méticuleux d’enquête. Il nous faut aller à la rencontre, dans tous les secteurs, sur tous les territoires où nous habitons, de ceux qui disposent des savoirs techniques stratégiques (19). »

Avec des frontières réhabilitées, sans la moindre porosité et grâce à des gardiens vigilants, dénués de remords, la société fermée décroissante adopterait vite la notion de puissance afin de tenir à distance un voisinage plus qu’avide de s’emparer de ses terres et de ses biens. Elle pratiquerait une nécessaire auto-suffisance tant alimentaire qu’énergétique. Mais cette voie vers l’autarcie salutaire risque de ne pas aboutir si la population n’entreprend pas d’elle-même une révolution culturelle et un renversement complet des consciences. « Outre l’autarcie économique européenne, il faudrait mieux encore parler d’autarcie technique, d’auto-isolement sanitaire; d’un refus de courir plus loin et plus vite vers le précipice, vers le monde de “ science-fiction contemporaine ” qui s’est installé sur toute la planète dans la plus parfaite soumission des gauchistes et des conservateurs (18). » L’auto-subsistance vivrière deviendra un atout considérable en périodes de troubles politiques et socio-économiques. « Tant que la perspective d’un soulèvement populaire signifiera pénurie certaine de soins, de nourriture ou d’énergie, il n’y aura pas de mouvement de masse décidé, prévient le Comité invisible. En d’autres termes : il nous faut reprendre un travail méticuleux d’enquête. Il nous faut aller à la rencontre, dans tous les secteurs, sur tous les territoires où nous habitons, de ceux qui disposent des savoirs techniques stratégiques (19). » Pour une question d’efficacité, une économie élaborée sur des mesures décroissantes ne peut être que d’échelle nationale ou continentale en étroit lien organique avec les niveaux (bio)régional et local. Il ne faut pas omettre que « le local n’est pas un microcosme fermé, mais un nœud dans un réseau de relations transversales vertueuses et solidaires, en vue d’expérimenter des pratiques de renforcement démocratique (dont les budgets participatifs) qui permettent de résister à la domination libérale (25) ». On réactualise une pratique politique traditionnelle : « L’autorité en haut, les libertés en bas ». Faut-il pour autant valoriser le local ? Non, répond le Comité invisible pour qui le local « est une contraction du global (26) ». Pourquoi cette surprenante défiance ? Par crainte de l’enracinement barrésien ? Par indécrottable altermondialisme ? « Il y a tout à perdre à revendiquer le local contre le global, soutient l’auteur (collectif ?) d’À nos amis. Le local n’est pas la rassurante alternative à la globalisation, mais son produit universel : avant que le monde ne soit globalisé, le lieu où j’habite était seulement mon territoire familier, je ne le connaissais pas comme “ local ”, le local n’est que l’envers du global, son résidu, sa sécrétion, et non ce qui peut le faire éclater (27). »

Pour une question d’efficacité, une économie élaborée sur des mesures décroissantes ne peut être que d’échelle nationale ou continentale en étroit lien organique avec les niveaux (bio)régional et local. Il ne faut pas omettre que « le local n’est pas un microcosme fermé, mais un nœud dans un réseau de relations transversales vertueuses et solidaires, en vue d’expérimenter des pratiques de renforcement démocratique (dont les budgets participatifs) qui permettent de résister à la domination libérale (25) ». On réactualise une pratique politique traditionnelle : « L’autorité en haut, les libertés en bas ». Faut-il pour autant valoriser le local ? Non, répond le Comité invisible pour qui le local « est une contraction du global (26) ». Pourquoi cette surprenante défiance ? Par crainte de l’enracinement barrésien ? Par indécrottable altermondialisme ? « Il y a tout à perdre à revendiquer le local contre le global, soutient l’auteur (collectif ?) d’À nos amis. Le local n’est pas la rassurante alternative à la globalisation, mais son produit universel : avant que le monde ne soit globalisé, le lieu où j’habite était seulement mon territoire familier, je ne le connaissais pas comme “ local ”, le local n’est que l’envers du global, son résidu, sa sécrétion, et non ce qui peut le faire éclater (27). »

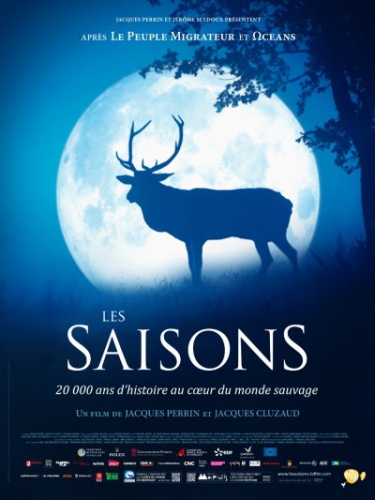

Procédant par touches impressionnistes, par une beauté visuelle, tout autant que sonore, « Les Saisons » se place dans le sillage de l'émerveillement permanent, de l'apologie de la beauté de notre nature. Grâce à une véritable prouesse technique, nous approchons au plus près des habitants de nos forêts, les voyant naître, grandir, mourir... A tel point que nous nous identifions aux cerfs, loups, lynx, ours, renards, sangliers et autres multiples espèces d'oiseaux qui constituent la diversité de notre faune, autant d'animaux qui font le bonheur des lecteurs de « La Salamandre » et de « La Hulotte ». Sans parler de la beauté des éléments (pluie, neige, vent, orage, aurore, crépuscule, nuit, pleine lune, etc.). Le film réussit également à nous montrer l'apparition des hommes au cœur de cette nature par petites touches comme si nous n'étions pas l'élément central de cette nature, mais l'un des hôtes.

Procédant par touches impressionnistes, par une beauté visuelle, tout autant que sonore, « Les Saisons » se place dans le sillage de l'émerveillement permanent, de l'apologie de la beauté de notre nature. Grâce à une véritable prouesse technique, nous approchons au plus près des habitants de nos forêts, les voyant naître, grandir, mourir... A tel point que nous nous identifions aux cerfs, loups, lynx, ours, renards, sangliers et autres multiples espèces d'oiseaux qui constituent la diversité de notre faune, autant d'animaux qui font le bonheur des lecteurs de « La Salamandre » et de « La Hulotte ». Sans parler de la beauté des éléments (pluie, neige, vent, orage, aurore, crépuscule, nuit, pleine lune, etc.). Le film réussit également à nous montrer l'apparition des hommes au cœur de cette nature par petites touches comme si nous n'étions pas l'élément central de cette nature, mais l'un des hôtes.

L’une de mes dernières rencontres avec lui a été au restaurant Les Ronchons, agréable lieu de rencontre de la « génération Occident ». Je ne me doutais pas qu’il nous quitterait quelques mois plus tard, en avril 2012.

L’une de mes dernières rencontres avec lui a été au restaurant Les Ronchons, agréable lieu de rencontre de la « génération Occident ». Je ne me doutais pas qu’il nous quitterait quelques mois plus tard, en avril 2012.

The philosopher of politics and history

The philosopher of politics and history  The knowledge which scientistic Puritanism so aggressively publishes, and which the Philosophy faculty so vigorously applauds, is a peculiar but typically modern species of knowledge. It is less a positive assertion of anything than it is a denial or, better yet, a denunciation of a longstanding prior assertion, and as such its character is largely if not entirely negative. Such knowledge is not sufficient by itself, offering its theses for impartial examination, but rather it requires a public performance to validate it. It must sweep up the crowd into a mood of unanimity. Such a performance, its rationalistic appurtenances notwithstanding, is essentially a cultic ritual: The spokeswoman’s presentation corresponded to an archaic exorcism, whose action banishes the smut of profanation from the boundaries of the community. And what specific bane fell under banishment? “Creationism,” according to the organization’s website, “refers to the religious belief in a supernatural deity or force that intervenes, or has intervened, directly in the physical world.” In sum, matter, in its uncreated purity, must never be contaminated by spirit. But why should an inversion of the classic Gnosticism, which remains Gnostic for all that it is an inversion, be a requirement?

The knowledge which scientistic Puritanism so aggressively publishes, and which the Philosophy faculty so vigorously applauds, is a peculiar but typically modern species of knowledge. It is less a positive assertion of anything than it is a denial or, better yet, a denunciation of a longstanding prior assertion, and as such its character is largely if not entirely negative. Such knowledge is not sufficient by itself, offering its theses for impartial examination, but rather it requires a public performance to validate it. It must sweep up the crowd into a mood of unanimity. Such a performance, its rationalistic appurtenances notwithstanding, is essentially a cultic ritual: The spokeswoman’s presentation corresponded to an archaic exorcism, whose action banishes the smut of profanation from the boundaries of the community. And what specific bane fell under banishment? “Creationism,” according to the organization’s website, “refers to the religious belief in a supernatural deity or force that intervenes, or has intervened, directly in the physical world.” In sum, matter, in its uncreated purity, must never be contaminated by spirit. But why should an inversion of the classic Gnosticism, which remains Gnostic for all that it is an inversion, be a requirement?