Les trois derniers numéros du Bulletin célinien

Numéro 422:

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

In memoriam Frédéric Monnier

Mort à crédit traduit en vietnamien

Céline, romancier de l’oubli

L’interview de Céline dans Europe-Amérique.

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

Les trois derniers numéros du Bulletin célinien

Numéro 422:

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

In memoriam Frédéric Monnier

Mort à crédit traduit en vietnamien

Céline, romancier de l’oubli

L’interview de Céline dans Europe-Amérique.

Il se savait condamné depuis plusieurs années et faisait face à la maladie avec un courage magnifique. J’ai fait sa connaissance il y a quarante ans lorsque Pierre publia son Ferdinand furieux avec 300 lettres inédites de Céline. Frédéric, lui aussi fervent admirateur de l’écrivain, suivit la trace de son père en se faisant l’éditeur de Céline dans les années 80. Il commença modestement en publiant, sous la forme de plaquettes, Chansons, puis un scénario de ballet, Arletty jeune fille dauphinoise, avant de s’attaquer à la correspondance de Céline, éditant celle-ci de manière rigoureuse et soignée. C’est ainsi que, grâce à lui, nous disposons de la correspondance à ses avocats (Naud et Tixier-Vignancour), à Joseph Garcin et enfin au traducteur hollandais de Céline, J. A. Sandfort. Faut-il préciser que ces éditions sont aujourd’hui très recherchées par la nouvelle génération de céliniens ? Les premiers livres qu’il a édités le furent sous l’égide de La Flûte de Pan, librairie musicale, sise rue de Rome à Paris, dont il fut le fondateur et qui s’avéra une belle réussite professionnelle. Ses dernières années furent consacrées à une enquête minutieuse sur son arrière grand-oncle, Marius Mariaud, figure méconnue du cinéma muet. Le livre, édité l’année passée par l’Association Française de Recherche sur l’Histoire du Cinéma, est un modèle de recherche historiographique. Durant quatre ans Frédéric y apporta tout le soin et la persévérance dont il était capable. Cet ouvrage, qui fera date, constitue une manière de testament. « Il s’agissait moins ici de réhabiliter un auteur que de montrer ce qu’a été le parcours d’un homme qui a participé à la grande aventure créatrice de son temps et qui a fini sa vie dans le dénuement et l’oubli », écrit-il en conclusion. Sans lui, seuls quelques cinéphiles pointus connaîtraient l’œuvre de ce pionnier ¹.

Lorsqu’on évoque sa mémoire, il importe de relever cet humour pince-sans-rire apprécié par ses amis. Et qui est apparu très tôt si l’on en juge par les souvenirs de son père : « Frédéric a huit ans et demi. Il est impassible, il écoute et sourit à peine… En classe, il est très sage, il travaille peu, parle peu, sauf pour dire par moment et sans broncher, une énormité. On l’appelle Buster Keaton. Ce soir, visite de notre ami Frédéric Pons, prof à Louis Le Grand. Homme de haute taille avec un fort accent biterrois et un crâne chauve et pointu. Il prend Frédéric dans ses bras… “Et toi, petit Frrrdérrric, tu ne me dis rien ?…” …Frédéric pose sa main sur le crâne chauve et dit : “Oh !… la belle petite poire à lavement…” ». Et l’auteur d’ajouter : « Les parents disparaissent lâchement dans la cuisine… ». Sur la même page, Pierre Monnier conte d’autres anecdotes révélatrices de l’esprit déjà facétieux du fiston ².

Frédéric n’était pas un admirateur frileux de Céline. À un ami qui désapprouvait l’attitude de l’exilé rendant son éditeur responsable de la réédition des pamphlets pendant la guerre, il répondait : « Je pense au contraire que, pour se défendre dans un procès politique, ces coups-là sont permis. D’autant plus que Denoël était mort. » Bien entendu, il était à nos côtés au cimetière de Meudon lorsqu’en 2011, François Gibault, entouré de quelques autres admirateurs de l’écrivain, prononça une allocution à l’occasion du cinquantenaire de sa mort. Grand moment d’émotion… Avec Frédéric Monnier, nous perdons un ami fidèle ainsi qu’un homme de talent.

Numéro 421:

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

Quand Céline se faisait siffler à Médan

La polémique de l’été 1957 dans l’hebdomadaire Dimanche-Matin

Quatre lettres de Paul Chambrillon à Albert Paraz

Résurrection d’Eugène Dabit

• « Louis-Ferdinand Céline, au fond de la nuit » (série “Grande traversée”). Production : Christine Lecerf. Réalisation : France Culture, 15-19 juillet 2019. À écouter sur www.lepetitcelinien.com.

Numéro 420

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

Céline et le Prix Goncourt

Robert Denoël défend Céline

Simlâ Ongan, traductrice de Mort à crédit

Vichy face aux Beaux draps

L’Odyssée de Ferdine

Envions ceux qui ne connaissent pas encore L’Année Céline. Que de découvertes passionnantes en perspective ! ¹ Nulle forfanterie de l’éditeur lorsqu’il présente sa revue comme « le premier outil de référence pour les amateurs et les chercheurs ». C’est indubitablement le cas. À propos de la dernière livraison, Éric Mazet écrit : « S’il n’y avait qu’une seule Année Céline à posséder, ce serait celle-ci. Mais j’ai la collection complète et je la garde précieusement ² ». Il n’est pas le seul. Peut-on d’ailleurs se dire célinien si l’on ne détient pas la trentaine de volumes édités chaque année depuis 1990 ? Comme à chaque fois, on peut y lire un ensemble de lettres de l’écrivain dont la plupart inédites. L’une date de la jeunesse du cuirassier Destouches, l’autre du début de carrière du médecin de dispensaire. On peut surtout y découvrir une quarantaine de lettres écrites en exil à son beau-père, Jules Almansor. Et quatre lettres au québécois Victor Barbeau, né la même année que Céline et décédé centenaire. Pièce maîtresse de ce volume : le Rapport de la police danoise après l’arrestation de Céline à Copenhague, traduit et présenté par François Marchetti, le meilleur connaisseur de cette période de la vie de l’écrivain. Également au sommaire : un relevé des articles citant Céline dans la revue L’Homme libre, deux textes de l’écrivain hollandais Cola Debrot, un dossier sur la réception critique de Mea culpa, et une analyse fouillée des sources inconnues de L’École des cadavres. Laquelle montre qu’une réflexion sérieuse sur les pamphlets ne peut faire l’économie de la littérature, ces écrits ne se limitant pas au combat idéologique. Une lecture purement historienne de ce corpus ne peut dès lors aboutir qu’à une impasse : « Cette lecture doit impérativement et nécessairement tenir compte de l’écriture, sans quoi elle rate son objet. »

Un mot sur la qualité formelle de cette série imprimée sur papier de qualité et brochée au fil. Le fait que l’éditeur en soit aussi l’imprimeur n’y est pas étranger. D’un bout à l’autre de la chaîne (composition, mise en page, impression et brochage), la totalité du travail est assurée par Jean-Paul Louis, artisan patenté. Pour le reste, on ne se lasse pas de dire notre dette envers lui. Je songe en premier lieu à la correspondance célinienne (Paraz, Canavaggia, Monnier, Hindus, anthologie de la Pléiade) dont il s’est fait l’éditeur scientifique ³. Dans l’appareil critique, il s’attache – et c’est rafraîchissant dans le cas de Céline – à ne pas porter de jugement moral, politique ou idéologique : « L’éditeur de correspondance n’est ni pour ni contre, il est avec (…) Proximité et distanciation ne sont pas contradictoires, mais complémentaires : se mettre à bonne distance pour ajuster sa vision, acquérir la plus grande netteté possible et transmettre le résultat de ses observations 4. »

• L’Année Céline 2018, Éditions du Lérot, 384 p., ill. (Diffusé par le BC, 45 € franco).

11:23 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, louis-ferdinand céline, revue, littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

09:52 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : antoine de saint-exupéry, nicolas bonnal, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature, littérature française, aviation |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

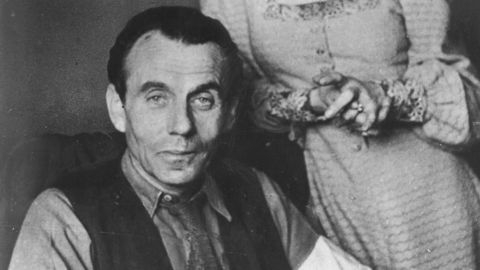

par Maurice Pergnier

Ex: https://www.bvoltaire.fr

L’œuvre de Peter Handke n’a pas besoin de polémiques médiatiques pour s’imposer. Elle était devenue mondialement la mascotte de toute une génération. C’est cependant la polémique qui « fait le buzz » autour de l’attribution du prix Nobel, ce 9 octobre, à cet écrivain à la fois atypique et profondément ancré dans les interrogations existentielles de l’humanité de son temps. Aux yeux du politiquement correct – appellation moderne du panurgisme –, la décision de l’Académie suédoise est une provocation, voire un blasphème.

Quoi ? Consacrer l’œuvre d’un auteur qui, dans les années 90, avait osé ne pas joindre sa voix à celle de la meute unanime qui hurlait sur tous les tons que les Serbes étaient les nouveaux nazis et Milošević le nouvel Hitler ! Justifiait-il bruyamment les crimes abominables qui leur étaient attribués ? Nullement. C’était pire : il déclarait calmement qu’il voulait se faire une idée par lui-même. Là était l’inexpiable blasphème : c’était refuser de prendre pour argent comptant la version des événements diffusée quotidiennement par les médias et les imprécateurs. C’était un crime de lèse-OTAN, de lèse-médias, de lèse-droits de l’homme, mais aussi, et surtout, de lèse-BHL, de lèse-Glucksmann… et autres. Impardonnable !

Et comment se faire une idée par soi-même ? En toutes choses, Handke n’a qu’une seule méthode : y aller voir, seul, sans accompagnement de caméras et micros et, si possible, à pied. S’immerger dans un réel perçu avec les sens, et témoigner, en payant de sa personne, du seul fait de sa présence. Contrairement aux penseurs en jets et hélicoptères, Peter Handke reste un marcheur invétéré. Il marche comme il pense, il pense comme il marche. Le scandale commença avec la publication, en 1996, en allemand, de Un voyage hivernal vers le Danube, la Save, la Morava et la Drina, sous-titré (Ô, horreur !) Justice pour la Serbie. Cet ouvrage fut abusivement qualifié de pamphlet alors que – comme le titre l’indique –, il s’agit d’un récit que l’auteur fait, par le menu, de sa découverte d’un pays diabolisé par le reste du monde, émaillé d’interrogations (sur un mode qui est tout sauf pamphlétaire !) sur la relation entre réel et information.

Et comment se faire une idée par soi-même ? En toutes choses, Handke n’a qu’une seule méthode : y aller voir, seul, sans accompagnement de caméras et micros et, si possible, à pied. S’immerger dans un réel perçu avec les sens, et témoigner, en payant de sa personne, du seul fait de sa présence. Contrairement aux penseurs en jets et hélicoptères, Peter Handke reste un marcheur invétéré. Il marche comme il pense, il pense comme il marche. Le scandale commença avec la publication, en 1996, en allemand, de Un voyage hivernal vers le Danube, la Save, la Morava et la Drina, sous-titré (Ô, horreur !) Justice pour la Serbie. Cet ouvrage fut abusivement qualifié de pamphlet alors que – comme le titre l’indique –, il s’agit d’un récit que l’auteur fait, par le menu, de sa découverte d’un pays diabolisé par le reste du monde, émaillé d’interrogations (sur un mode qui est tout sauf pamphlétaire !) sur la relation entre réel et information.

Ce fut le début de la curée. Chez nous – il est important de le rappeler –, l’hallali fut sonné, dans Libération, avant même la parution de la traduction française, ce qui fait qu’aucun chroniqueur se joignant à la charge n’avait pu vérifier les accusations de « négationnisme » (et autres aménités du même genre) lancées comme des missiles de croisière.

On connaît la suite : Handke a continué de marcher à son pas, et non à celui des tambours, allant jusqu’à assister à l’enterrement de Milošević et à y déclarer : « Le monde, le soi-disant monde sait tout sur la Yougoslavie, la Serbie […] Moi, je ne connais pas la vérité. Mais je regarde. J’écoute. Je ressens. Je me souviens. Je questionne. » Propos inqualifiables dans la bouche d’un écrivain !

Lisez l'ouvrage de Maurice Pergnier:

La désinformation par les mots : Les mots de la guerre, la guerre des mots, Ed. du Rocher, 2004, 18,20 euro.

La désinformation par les mots : Les mots de la guerre, la guerre des mots, Ed. du Rocher, 2004, 18,20 euro.La Désinformation par les mots est un réquisitoire aussi cruel que pertinent sur l'usage admis de certains vocables, une fois ces derniers passés à la moulinette du politiquement correct. Aussi Maurice Pergnier s'en prend-il particulièrement à tous les thèmes qui " font problème ", et sur lesquels une position même légèrement dissidente effarouche les tenants de la " pensée unique " : les jeunes, les banlieues, la démocratie, l'islamisme, l'Europe, ou encore le multiethnisme. Présenté sous la forme d'un dictionnaire alphabétique, La Désinformation par les mots bénéficie en outre d'une entrée en matière qui est un véritable morceau d'anthologie. Livre drôle, percutant et qui s'éloigne résolument des sentiers battus, l'ouvrage est vivement recommandé à tous ceux qui ont su conserver une authentique liberté d'esprit.

11:54 Publié dans Actualité, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : prix nobel, peter handke, littérature, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature allemande, autriche |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

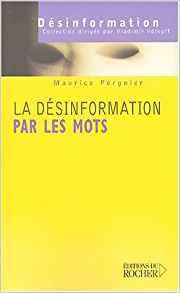

H. P. Lovecraft’s novella At the Mountains of Madness, serialized in Astounding in 1936, is one of his greatest works. The tale recounts an expedition to Antarctica in 1930 in which scholars from Miskatonic University stumble upon the ruins of a lost city. Their examination of the site paints a vivid picture of this once-great civilization, whose history reflects Lovecraft’s own political and social views.

Lovecraft had a lifelong fascination with the Antarctic and was an avid reader of Antarctic fiction. Among the books that influenced him were W. Frank Russell’s The Frozen Pirate, James De Mille’s A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, and Edgar Allen Poe’s novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (the conclusion takes place in the Antarctic), from which he borrowed the cry of “Tekeli-li!”

The story is narrated by William Dyer, a geology professor at Miskatonic University and the leader of the expedition. The purpose of the expedition is to collect fossils with the aid of a high-tech drill invented by an engineering professor at the university. Along with more typical findings, they detect a triangular marking imprinted upon fragments of rock. Dyer claims that this is merely evidence of striations, but a certain Professor Lake unearths more prints and wishes to follow their lead.

A group led by Lake sets off to investigate the source of the prints and discovers the remains of fourteen mysterious amphibious specimens with star-shaped heads, wings, and triangular feet. They are highly evolved creatures, with five-lobed brains, yet the stratum in which they were found indicates that they are about forty million years old. Shortly thereafter, Lake and his team (with the exception of one man) are slaughtered. When Dyer and the others arrive at the scene, they find six of the specimens buried in large “snow graves” and learn that the remaining specimens have vanished, along with several other items. Additionally, the planes and mechanical devices at the camp were tampered with. Dyer concludes that the missing man simply went mad, wreaked havoc upon the camp, and then ran away.

A group led by Lake sets off to investigate the source of the prints and discovers the remains of fourteen mysterious amphibious specimens with star-shaped heads, wings, and triangular feet. They are highly evolved creatures, with five-lobed brains, yet the stratum in which they were found indicates that they are about forty million years old. Shortly thereafter, Lake and his team (with the exception of one man) are slaughtered. When Dyer and the others arrive at the scene, they find six of the specimens buried in large “snow graves” and learn that the remaining specimens have vanished, along with several other items. Additionally, the planes and mechanical devices at the camp were tampered with. Dyer concludes that the missing man simply went mad, wreaked havoc upon the camp, and then ran away.

The following day, Dyer and a graduate student named Danforth embark on a flight across the mountains. The two discover a labyrinthine ancient megalopolis consisting of gargantuan fortifications and dark, titanic stone structures of various shapes (cones, pyramids, cubes, cylinders). Upon entering “that cavernous, aeon-dead honeycomb of primal masonry” through a gap left by a fallen bridge, they find that the interiors are adorned with intricate carvings chronicling the history of the city. They realize that the city’s inhabitants must have been the “Old Ones” (more precisely, the Elder Things) extraterrestrial beings described in the Necronomicon.

The Old Ones were highly intelligent creatures who possessed advanced technology and had a sophisticated understanding of science. They came to the Antarctic Ocean from outer space soon after the moon was formed. They were responsible for the creation of shoggoths, “shapeless entities composed of a viscous jelly which looked like an agglutination of bubbles.” The shoggoths were unintelligent, slavish creatures designed to serve the Old Ones, who controlled them through hypnosis.

The Old Ones warred with Cthulhu spawn until Cthulhu cities (including R’lyeh) sank into the Pacific Ocean. The invasion of a species called the Mi-go during the Jurassic period prompted another war in which the Old Ones were driven out of northern lands back into their original Antarctic habitat.

Over time, the civilization of the Old Ones began to enter a dark age. The shoggoths mutated, broke their masters’ control over them, and rebelled. The carvings also allude to an even greater evil hailing from lofty mountains where no one ever dared to venture. The advent of an ice age that drove the Old Ones to abandon the city and settle underwater cemented their slow demise. For the construction of their new settlement, the Old Ones simply transplanted portions of their land city to the ocean floor, symbolizing their artistic decline and lack of ingenuity.

The carvings of the Old Ones became coarse and ugly, a parody of what they once had been. Dyer and Danforth attribute their aesthetic decline to the intrusion of something foreign and alien:

We could not get it out of our minds that some subtly but profoundly alien element had been added to the aesthetic feeling behind the technique—an alien element, Danforth guessed, that was responsible for the laborious substitution. It was like, yet disturbingly unlike, what we had come to recognize as the Old Ones’ art; and I was persistently reminded of such hybrid things as the ungainly Palmyrene sculptures fashioned in the Roman manner.

The squawking of a penguin beckons Dyer and Danforth to a dark tunnel, where they find the mutilated bodies of Old Ones who were brutally murdered and decapitated by shoggoths. They are covered in thick, black slime, the sight of which imparts Dyer with cosmic terror. He and Danforth flee the site and climb aboard the plane. Danforth glances backward and comes face-to-face with something so horrifying that he has a nervous breakdown and becomes insane.

The dichotomy between the Old Ones and the shoggoths reflects Lovecraft’s racial views. Lovecraft’s universe is a hierarchical one. The Old Ones are noble, highly evolved creatures who excel in art and technology. The shoggoths, meanwhile, are horrifyingly ugly and possess limited cognitive capabilities. Indeed, Lovecraft’s description of the shoggoths is nearly indistinguishable from this colorful description of inhabitants of the Lower East Side from one of his letters:

. . . monstrous and nebulous adumbrations of the pithecanthropoid and amoebal; vaguely moulded from some stinking viscous slime of earth’s corruption, and slithering and oozing in and on the filthy streets or in and out of windows and doorways in a fashion suggestive of nothing but infesting worms or deep-sea unnamabilities.[1]

The Old Ones, despite being extraterrestrial beings, do not represent alien horrors. By the end of the book, Dyer exclaims, in awe of their civilization: “Radiates, vegetables, monstrosities, star-spawn—whatever they had been, they were men!” The great evil glimpsed by Danforth is the same evil feared by the Old Ones, and it is that which is embodied by the shoggoths.

Even the realization that the Old Ones slaughtered Lake and the others does not change this perception. When Dyer finds the corpse of the missing explorer (and his dog), he takes note of the care with which the Old Ones dissected and preserved the corpse. He admires their scientific approach and compares them to the scholars they killed.

The fact that the Old Ones’ demise was caused, in part, by their failure to subjugate the shoggoths could be a commentary on the horrors let loose by the emancipation of black slaves in America, or perhaps on Bolshevik revolts. The idea of a golem revolt also has a modern-day parallel in the possibility of malign artificial intelligence (see the paperclip problem).

That said, Lovecraft is not particularly concerned with how the Old Ones’ decline might have been averted. He shares Spengler’s view that civilizations are comparable to organisms and pass through an inevitable cycle of youth, manhood, and old age.

Spengler’s theories about history had a strong influence on Lovecraft. He read the first volume of Decline of the West in February 1927. In 1928, he remarked:

Spengler is right, I feel sure, in classifying the present phase of Western civilisation as a decadent one; for racial-cultural stamina shines more brightly in art, war, and prideful magnificence than in the arid intellectualism, engulfing commercialism, and pointless material luxury of an age of standardization and mechanical invention like the one now well on its course.[2]

In another letter, he writes: “It is my belief—and was so long before Spengler put his seal of scholarly approval on it—that our mechanical and industrial age is one of frank decadence; so far removed from normal life and ancestral conditions as to make impossible its expression in artistic media.”[3]

The word “decadent” appears many times in At the Mountains of Madness. While the oldest structure they encounter exhibits an artistry “surpassing anything else,” the later art “would be called decadent by comparison.”

Lovecraft’s description of the Old Ones’ government as “probably socialistic” reflects his growing disillusionment with laissez-faire capitalism. He may have been influenced by Spengler in this regard as well. He uses the term “fascistic socialism” in A Shadow Out of Time.

Another influence on At the Mountains of Madness was the Russian painter, archaeologist, and mystic Nicholas Roerich. Roerich is mentioned numerous times throughout the book, and Lovecraft’s prose is evocative of his haunting landscapes. One passage in particular brought to mind Roerich’s Path to Shambhala: “Distant mountains floated in the sky as enchanted cities, and often the whole white world would dissolve into a gold, silver, and scarlet land of Dunsanian dreams and adventurous expectancy under the magic of the low midnight sun.”

The ending of the book contains a harrowing portrait of one of Lovecraft’s most terrifying creations. The eldritch horror of the shoggoth represents, in distilled form, modernity and its pathologies. “Its first results we behold today,” he wrote in 1928, “though the depths of its cultural darkness are reserved for the torture of later generations.”[4]

Notes

1. H. P. Lovecraft, Selected Letters I.333-34.

2. II.228.

3. II.103-104.

4. II.305.

00:26 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lettres, lettres américaines, littérature, littérature américaine, lovecraft, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Yukio Mishima

Life for Sale

Translated by Stephen Dodd

London: Penguin Books, 2019

This past year has seen three new English translations of novels by Yukio Mishima: The Frolic of the Beasts, Star, and now Life for Sale, a pulpy, stylish novel that offers an incisive satire of post-war Japanese society.

Mishima’s extensive output includes both high-brow literary and dramatic works (jun bungaku, or “pure literature”) and racy potboilers (taishu bungaku, or “popular literature”). Life for Sale belongs to the latter category and will introduce English readers to this lesser-known side of Mishima. Despite being a popular novel, though, it broaches serious themes that can also be found in Mishima’s more sophisticated works.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

When his suicide attempt fails, Hanio comes up with another idea. He places the following advertisement in the newspaper: “Life for Sale. Use me as you wish. I am a twenty-seven-year-old male. Discretion guaranteed. Will cause no bother at all” (p. 7). The advertisement sets in motion an exhilarating series of events involving adultery, murder, toxic beetles, a female “vampire,” a wasted heiress, poisonous carrots, espionage, and mobsters.

In one episode, Hanio is asked to provide services for a single mother who has already gone through a dozen boyfriends. It turns out that the woman has a taste for blood. Every night, she cuts Hanio with a knife and sucks on the wound. She occasionally takes Hanio on walks, keeping him bound to her with a golden chain. Hanio lives with the woman for a while, and her son remarks, rather poignantly, that the three of them could be a family. The scene calls to mind the modern Japanese practice of “renting” companions and family members.

By the end of the vampire gig, Hanio is severely ill and on the verge of death. Yet he is entirely indifferent to this fact: “The thought that his own life was about to cease cleansed his heart, the way peppermint cleanses the mouth” (p. 83). His existence is bland and meaningless, devoid of both “sadness and joy.”

When Hanio returns to his apartment to pick up his mail, he finds a letter from a former classmate admonishing him for the advertisement:

What on earth do you hope to attain by holding your life so cheaply? For an all too brief time before the war, we considered our lives worthy of sacrifice to the nation as honourable Japanese subjects. They called us common people “the nation’s treasure.” I take it you are in the business of converting your life into filthy lucre only because, in the world we inhabit, money reigns supreme. (p. 79)

With the little strength he has remaining, Hanio tears the letter into pieces.

Hanio survives the vampire episode by the skin of his teeth and wakes up in a hospital bed. He has scarcely recovered when two men burst into his room asking him to partake in a secret operation. After the ambassador of a certain “Country B” steals an emerald necklace containing a cipher key from the wife of the ambassador of “Country A” (strongly implied to be England), the latter ambassador has the idea of stealing the cipher key in the possession of the former. The ambassador of Country B is very fond of carrots, and it is suspected that his stash of carrots is of relevance. Three spies from Country A each steal a carrot, only to drop dead. All but a few of the ambassador’s carrots were laced with potassium cyanide, and only he knew which ones were not. It takes Hanio to state the obvious: any generic carrot would have done the trick, meaning that the spies’ deaths were in vain.

Like Hanio’s other adventures, it is the sort of hare-brained caper one would expect to find in manga. Perhaps Mishima is poking fun at the ineptitude of Western democracies, or Britain in particular. (I am reminded of how Himmler allegedly remarked after the Gestapo tricked MI6 into maintaining radio contact that “after a while it becomes boring to converse with such arrogant and foolish people.”)

After the carrot incident, Hanio decides to move and blurts out the first destination that comes to mind. He ends up moving in with a respectable older couple and their errant youngest child, Reiko. Reiko’s parents are traditionalists who treat him with “an almost inconceivable degree of old-fashioned courtesy” (p. 122). The father reads classical Chinese poetry and collects old artifacts, among them a scroll depicting the legend of the Peach Blossom Spring. Reiko, meanwhile, spends her days doing drugs and hanging out with hippies in Tokyo. She is in her thirties, but she acts like a young girl. Although her parents are traditionally-minded, they bend to her every whim and do not discipline her.

It is explained that Reiko’s would-be husband turned her down out of a mistaken belief that her father had syphilis. Bizarrely, Reiko has convinced herself that she inherited the disease and that she will die a slow and painful death. Her death wish (combined with her parents’ negligence) appears to be the cause of her self-destructive behavior. She dreams of losing her virginity to a young man who would be willing to risk death by sleeping with her. Yet her fantasies turn out to be rather domestic. She play-acts a scene in which she tells an imaginary son that his father will be coming home at 6:15, as he does everyday.

This reminds Hanio of his former life as a copywriter and suddenly causes him to realize that the scourge of the city is palpable even in the cloistered confines of the tea house in which he is staying: “Out there, restless nocturnal life continued to pulse. . . . Such was the hell that bared its fangs and whirled around Hanio and Reiko’s comfortable little tomb” (pp. 147-48).

Hanio makes his escape one night when Reiko takes him to the disco. At the end of the novel, he visits a police station and asks for protection from some mobsters who want him dead (long story). The police dismiss him as delusional and cast him out. He is left alone, gazing at the night sky.

Underneath the campy pulp-fiction tropes, Life for Sale is a sincere meditation on the meaningless and absurdity of modern urban life. Surrendering one’s life is the most convenient escape from such an existence. The only alternative is to identify a higher purpose and pursue it relentlessly—after the manner of Mishima himself.

00:18 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, livres, lettres japonaises, littérature japonaise, japon, mishima, yukio mishima |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

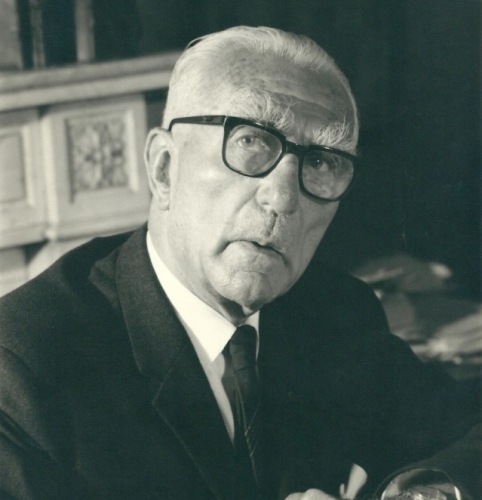

Une biographie de l'écrivain nationaliste belge Pierre Nothomb par Lionel Baland

L'historien liégeois Lionel Baland, spécialiste des mouvements nationaux et identitaires en Europe cliquez ici, vient de publier aux Editions Pardès une biographie de son compatriote belge au parcours atypique Pierre Nothomb.

Pierre Nothomb naît en Belgique en 1887. Il y étudie le droit et devient avocat. Démocrate-chrétien avant la Première Guerre mondiale, il combat au début du conflit dans la garde civique. Actif à partir de 1915 au sein des cercles gouvernementaux belges en exil en France, il est un des propagandistes du nationalisme belge et milite pour la réalisation, à l’issue de la guerre, d’une Grande Belgique résultant de l’annexion du Luxembourg, d’une partie des Pays-Bas et d’une partie de l’Allemagne.

Au cours des années 1920, ami et adepte de Benito Mussolini – ses adversaires le surnomment Mussolinitje (« petit Mussolini ») –, Pierre Nothomb dirige les Jeunesses nationales, qui affrontent physiquement socialistes, communistes et nationalistes flamands. Après avoir pris part aux débuts du rexisme aux côtés de Léon Degrelle, il rejoint le Parti catholique et, en 1936, devient sénateur.

Auteur de nombreux ouvrages, il est, jusque l’année précédant son décès survenu en 1966, sénateur du Parti Social-Chrétien. Son fils, Charles-Ferdinand, devient vice-Premier ministre, président de la Chambre des députés et président du Parti Social-Chrétien. Son arrière-petite-fille est la romancière Amélie Nothomb.

Ce « Qui suis-je ? » Pierre Nothomb présente l’écrivain et l’homme politique nationaliste et catholique dont la vie est liée de manière intime à celle de son pays, la Belgique, et à la terre de ses ancêtres.

Citation : « Une nation tranquille, endormie dans la paix et n’ayant d’autre orgueil, semblait-il, que sa richesse, sentit tout à coup peser sur elle la plus formidable menace. Cette guerre, qui devait l’épargner […], elle allait en être la première victime. L’odieux ultimatum allemand lui demanda l’Honneur ou la Vie. Elle répondit : la Vie. » (Les Barbares en Belgique.)

L’auteur : Lionel Baland est un écrivain belge francophone, quadrilingue, spécialiste des partis patriotiques en Europe et du nationalisme en Belgique.

Pierre Nothomb, Lionel Baland, Pardès, collection "Qui suis-je ?", 2019, 12 euros

10:33 Publié dans Belgicana, Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : pierre nothomb, lionel baland, belgiue, belgicana, histoire, littérature, littérature belge, lettres, lettres belges, nationalisme, nationalisme belge |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

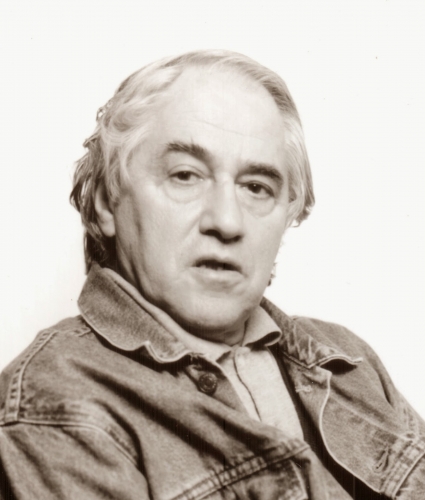

Les célèbres flics, Starsky et Hutch, sont en deuil. Le parolier du générique français de leur série télévisée de la fin des années 1970 les a quittés le 7 avril dernier. Né le 31 mai 1933, Jean-Claude Albert-Weil a longtemps travaillé pour les chaînes de télévision française. Il produisit aussi sur ces chaînes des émissions de jazz.

Si cette chronique l’évoque, c’est en tant qu’auteur de L’Altermonde, une formidable trilogie romanesque, hybridation littéraire inouïe de Sade, de Céline, de Swift et de Rabelais. En 1996 paraît aux Éditions du Rocher Sont les Oiseaux… (réintitulé Europa), qui obtiendra dès l’année suivante le Prix du Roman de la Société des Gens de Lettres. La dite-société le regrettera quelques années plus tard avec la parution du deuxième volume, Franchoupia (L’Âge d’Homme, 2000), puis, en 2004, de Siberia aux éditions Panfoulia fondées par Jean-Claude Albert-Weil lui-même afin de contourner le blocus éditorial imposé à son œuvre.

L’Altermonde est une fresque uchronique magistrale. Cédant aux pressions allemandes, Franco permet à la Wehrmacht de traverser l’Espagne et de s’emparer de Gibraltar. L’Allemagne gagne ensuite la Seconde Guerre mondiale et parvient à unifier tout le continent européen. Deux dénazifications après, l’Empire européen est une puissance géopolitique. Il suit les règles de l’existentialisme heideggérien, autorise une très large permissivité sexuelle, applique un malthusianisme implacable et pratique une écologie radicale qu’approuverait tout décroissant sincère.

Des trois volumes de L’Altermonde, le deuxième, Franchoupia, est le moins abouti. Il traite d’une France libre réduite à la Guyane. Il s’agit d’une satire virulente de l’Hexagone sous les présidences de François Mitterrand et de Jacques Chirac. Il faut cependant reconnaître que deux décennies plus tard, l’immonde société franchoupienne s’épanouit sous les différents quinquennats de Sarközy, de Hollande et de Macron !

Des trois volumes de L’Altermonde, le deuxième, Franchoupia, est le moins abouti. Il traite d’une France libre réduite à la Guyane. Il s’agit d’une satire virulente de l’Hexagone sous les présidences de François Mitterrand et de Jacques Chirac. Il faut cependant reconnaître que deux décennies plus tard, l’immonde société franchoupienne s’épanouit sous les différents quinquennats de Sarközy, de Hollande et de Macron !

Cette trilogie uchronique tire son originalité du vocabulaire qui s’ouvre largement aux nombreux néologismes ainsi qu’à sa structure narrative toute droite sortie d’un orchestre de jazz dirigé par Céline ! Cependant, Jean-Claude Albert-Weil avouait dans Réflexions d’un inhumaniste (ses entretiens avec François Bousquet parus en 2007 chez Xenia) qu’il était « aventuré de me réduire à Céline. Ma littérature est constructive, optimiste, avec certaines naïvetés, puisqu’elle croit à la science (p. 32) ». En introduction à ces entretiens, le futur rédacteur en chef du magazine des idées Éléments lui décernait « le Prix Nobel du samizdat (p. 7) » et affirmait que « le créateur du langagevo (langage évolué) bouscule trop joyeusement les stéréotypes et les clichés, et notamment littéraires, pour que la société de spectacle le lui pardonne (p. 10) ».

Jean-Claude Albert-Weil aimait se moquer du politiquement correct. « Je ne suis pas un écrivain reconnu, je ne suis pas un auteur conventionnel, je suis libre de faire ce que je veux. […] Des années durant, j’ai écrit sans publier. […] Est-ce qu’on écrit ce qu’on veut ou est-ce qu’on fait carrière ? J’ai choisi la destinée métaphysique, autant jouer un jeu risqué et autant le jouer avec farouchitude (pp. 34 – 35). » Pour preuve, dans son Altermonde euro-sibérien, le transhumanisme et l’eugénisme assurent aux dirigeants paneuropéens une conception « sur-occidentale » et « archéofuturiste (p. 10) ». « Euro-Sibérie », « archéofuturisme », les thèmes chers à Guillaume Faye sont donc bien présents dans l’œuvre albert-weilienne, ce qui n’est pas anodin. Au début des années 2000, Guillaume Faye et Jean-Claude Albert-Weil s’étaient plusieurs fois rencontrés. Décédés à quelques semaines d’intervalle, les deux hommes partageaient une vision du monde assez semblable.

Esprit libre et réfractaire à tout conformisme ambiant, Jean-Claude Albert-Weil méritait bien de figurer dans le panthéon dionysiaque des grandes figures européennes.

Georges Feltin-Tracol

• Chronique n° 26, « Les grandes figures identitaires européennes », lue le 18 juin 2019 à Radio-Courtoisie au « Libre-Journal des Européens » de Thomas Ferrier.

00:30 Publié dans Hommages, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : jean-claude albert-weil, hommage, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Quand Chateaubriand décrit notre Fin des Temps

par Nicolas Bonnal

Un des plus grands et importants textes du monde, le premier peut-être qui nous annonce comment tout va être dévoré : civilisation occidentale et autres, peuples, sexes, cultures, religions aussi. C’est la conclusion des Mémoires d’outre-tombe. On commence avec l’unification technique du monde :

« Quand la vapeur sera perfectionnée, quand, unie au télégraphe et aux chemins de fer, elle aura fait disparaître les distances, ce ne seront plus seulement les marchandises qui voyageront, mais encore les idées rendues à l'usage de leurs ailes. Quand les barrières fiscales et commerciales auront été abolies entre les divers Etats, comme elles le sont déjà entre les provinces d'un même Etat ; quand les différents pays en relations journalières tendront à l'unité des peuples, comment ressusciterez−vous l'ancien mode de séparation ? »

On ne réagira pas. Chateaubriand voit l’excès d’intelligence venir :

On ne réagira pas. Chateaubriand voit l’excès d’intelligence venir :

« La société, d'un autre côté, n'est pas moins menacée par l'expansion de l'intelligence qu'elle ne l'est par le développement de la nature brute. Supposez les bras condamnés au repos en raison de la multiplicité et de la variété des machines, admettez qu'un mercenaire unique et général, la matière, remplace les mercenaires de la glèbe et de la domesticité : que ferez−vous du genre humain désoccupé ? Que ferez−vous des passions oisives en même temps que l'intelligence ? La vigueur du corps s'entretient par l'occupation physique ; le labeur cessant, la force disparaît ; nous deviendrions semblables à ces nations de l'Asie, proie du premier envahisseur, et qui ne se peuvent défendre contre une main qui porte le fer. Ainsi la liberté ne se conserve que par le travail, parce que le travail produit la force : retirez la malédiction prononcée contre les fils d'Adam, et ils périront dans la servitude : In sudore vultus tui, vesceris pane. »

Le gain technique va se payer formidablement. Vient une formule superbe (l’homme moins esclave de ses sueurs que de ses pensées) :

« La malédiction divine entre donc dans le mystère de notre sort ; l'homme est moins l'esclave de ses sueurs que de ses pensées : voilà comme, après avoir fait le tour de la société, après avoir passé par les diverses civilisations, après avoir supposé des perfectionnements inconnus on se retrouve au point de départ en présence des vérités de l'Ecriture. »

Puis Chateaubriand constate la fin de la monarchie :

« La société entière moderne, depuis que la barrière des rois français n'existe plus, quitte la monarchie. Dieu, pour hâter la dégradation du pouvoir royal, a livré les sceptres en divers pays à des rois invalides, à des petites filles au maillot ou dans les aubes de leurs noces : ce sont de pareils lions sans mâchoires, de pareilles lionnes sans ongles, de pareilles enfantelettes tétant ou fiançant, que doivent suivre des hommes faits, dans cette ère d'incrédulité. »

Il voit le basculement immoral de l’homme moderne, grosse bête anesthésiée, ou aux indignations sélectives, qui aime tout justifier et expliquer :

« Au milieu de cela, remarquez une contradiction phénoménale : l'état matériel s'améliore, le progrès intellectuel s'accroît, et les nations au lieu de profiter s'amoindrissent : d'où vient cette contradiction ?

C'est que nous avons perdu dans l'ordre moral. En tout temps il y a eu des crimes ; mais ils n'étaient point commis de sang−froid, comme ils le sont de nos jours, en raison de la perte du sentiment religieux. A cette heure ils ne révoltent plus, ils paraissent une conséquence de la marche du temps ; si on les jugeait autrefois d'une manière différente, c'est qu'on n'était pas encore, ainsi qu'on l'ose affirmer, assez avancé dans la connaissance de l'homme ; on les analyse actuellement ; on les éprouve au creuset, afin de voir ce qu'on peut en tirer d'utile, comme la chimie trouve des ingrédients dans les voiries. »

C'est que nous avons perdu dans l'ordre moral. En tout temps il y a eu des crimes ; mais ils n'étaient point commis de sang−froid, comme ils le sont de nos jours, en raison de la perte du sentiment religieux. A cette heure ils ne révoltent plus, ils paraissent une conséquence de la marche du temps ; si on les jugeait autrefois d'une manière différente, c'est qu'on n'était pas encore, ainsi qu'on l'ose affirmer, assez avancé dans la connaissance de l'homme ; on les analyse actuellement ; on les éprouve au creuset, afin de voir ce qu'on peut en tirer d'utile, comme la chimie trouve des ingrédients dans les voiries. »

La corruption va devenir institutionnalisée :

« Les corruptions de l'esprit, bien autrement destructives que celles des sens, sont acceptées comme des résultats nécessaires ; elles n'appartiennent plus à quelques individus pervers, elles sont tombées dans le domaine public. »

On refuse une âme, on adore le néant et l’hébétement (Baudrillard use du même mot) :

« Tels hommes seraient humiliés qu'on leur prouvât qu'ils ont une âme, qu'au-delà de cette vie ils trouveront une autre vie ; ils croiraient manquer de fermeté et de force et de génie, s'ils ne s'élevaient au-dessus de la pusillanimité de nos pères ; ils adoptent le néant ou, si vous le voulez, le doute, comme un fait désagréable peut−être, mais comme une vérité qu'on ne saurait nier. Admirez l'hébétement de notre orgueil ! »

L’individu triomphera et la société périra :

« Voilà comment s'expliquent le dépérissement de la société et l'accroissement de l'individu. Si le sens moral se développait en raison du développement de l'intelligence, il y aurait contrepoids et l'humanité grandirait sans danger, mais il arrive tout le contraire : la perception du bien et du mal s'obscurcit à mesure que l'intelligence s'éclaire ; la conscience se rétrécit à mesure que les idées s'élargissent. Oui, la société périra : la liberté, qui pouvait sauver le monde, ne marchera pas, faute de s'appuyer à la religion ; l'ordre, qui pouvait maintenir la régularité, ne s'établira pas solidement, parce que l'anarchie des idées le combat… »

Une belle intuition est celle-ci, qui concerne…la mondialisation, qui se fera au prix entre autres de la famille :

« La folie du moment est d'arriver à l'unité des peuples et de ne faire qu'un seul homme de l'espèce entière, soit ; mais en acquérant des facultés générales, toute une série de sentiments privés ne périra−t−elle pas ? Adieu les douceurs du foyer ; adieu les charmes de la famille ; parmi tous ces êtres blancs, jaunes, noirs, réputés vos compatriotes, vous ne pourriez vous jeter au cou d'un frère. »

Puis Chateaubriand décrit notre société nulle, flat (Thomas Friedman), plate et creuse et surtout ubiquitaire :

« Quelle serait une société universelle qui n'aurait point de pays particulier, qui ne serait ni française, ni anglaise, ni allemande, ni espagnole, ni portugaise, ni italienne ? ni russe, ni tartare, ni turque, ni persane, ni indienne, ni chinoise, ni américaine, ou plutôt qui serait à la fois toutes ces sociétés ? Qu'en résulterait−il pour ses mœurs, ses sciences, ses arts, sa poésie ? Comment s'exprimeraient des passions ressenties à la fois à la manière des différents peuples dans les différents climats ? Comment entrerait dans le langage cette confusion de besoins et d'images produits des divers soleils qui auraient éclairé une jeunesse, une virilité et une vieillesse communes ? Et quel serait ce langage ? De la fusion des sociétés résultera−t−il un idiome universel, ou bien y aura−t−il un dialecte de transaction servant à l'usage journalier, tandis que chaque nation parlerait sa propre langue, ou bien les langues diverses seraient−elles entendues de tous ? Sous quelle règle semblable, sous quelle loi unique existerait cette société ? »

Et de conclure sur cette prison planétaire :

« Comment trouver place sur une terre agrandie par la puissance d'ubiquité, et rétrécie par les petites proportions d'un globe fouillé partout ? Il ne resterait qu'à demander à la science le moyen de changer de planète. »

Elle n’en est même pas capable…

Source:

Chateaubriand, Mémoires, conclusion

13:54 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : françois-rené de chateaubriand, nicolas bonnal, littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Bulletin Célinien n°419

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

Sur un colloque oublié

Céline et Maurice Nadeau (suite)

Baryton et Parapine

Malraux (Alain) salue « le médecin des pauvres »

Un éditeur sous l’Occupation

Quand Dubuffet voulait aider Céline

Le doyen des célinistes se souvient.

Un abonné m’écrit : « J’avais déjà lu et apprécié les cahiers de prison dans L’Année Céline, puis dans l’édition de Henri Godard avec fac-similés. J’ai pourtant l’impression d’en découvrir de nouvelles richesses dans les Cahiers Céline. Est-ce le format, la continuité du texte, la qualité des annotations de Jean-Paul Louis ? Toujours est-il que c’est à cette édition que je retournerai le plus volontiers, et je la recommande à tous les céliniens. » L’intérêt de cette édition se trouve ainsi parfaitement résumé. Si ce corpus était déjà connu des céliniens, le fait que toutes les parties en soient réunies en un seul volume constitue une heureuse initiative.Rappel des faits : c’est le 17 décembre 1945 que Céline est arrêté, les autorités françaises ayant demandé son extradition après avoir appris sa présence à Copenhague. Incarcéré à la prison de l’Ouest (essentiellement cellule 609, section K), Céline demande de quoi écrire. L’administration pénitentiaire lui fournit dix cahiers d’écolier de 32 pages avec comme consigne impérative de ne pas écrire sur l’affaire dont il est justiciable. Il n’en tiendra évidemment pas compte et, de février à octobre 1946, rédigera un ensemble de notes sur sa défense et ses accusateurs mais aussi sur d’autres sujets : épisodes de sa vie, conditions de réclusion, synopsis et esquisse pour des romans à venir, citations extraites de ses nombreuses lectures d’emprisonné qui lui permettent de tenir. Dans une préface éclairante Jean-Paul Louis relève que ces cahiers illustrent la transition célinienne vers ce qu’il nomme la « seconde révolution narrative et stylistique ». Laquelle s’engage par ce chef-d’œuvre, piètrement accueilli à son retour en France et encore méconnu aujourd’hui : Féerie pour une autre fois. Il faut saluer le soin avec lequel le texte a été établi et la qualité des annotations dont les connaisseurs avaient déjà en partie connaissance par trois livraisons de L’Année Céline, parues de 2007 à 2009. Comme on s’y attend, les formules incisives surgissent sous la plume du prisonnier. Florilège : « À Sigmaringen les réfugiés bouffent de la chimère » – « Moi aussi la Sirène d’Andersen m’a fait venir à Copenhague et puis elle m’a assassiné. » – « Je me sens tout à fait absous pour mes errements passés, mes cavaleries polémiques lorsque je vois avec quelle furie, quelle lâcheté, quelles effronteries, mes adversaires m’accablent à présent que je suis vaincu. » – « Je suis peut-être un des rares êtres au monde qui devraient être libres, presque tous les autres ont mérité la prison par leur servilité prétentieuse, leur bestialité ignoble, leur jactance maudite. » – « Pendant 4 ans il a fallu louvoyer au bord de la collaboration sans jamais tomber dedans. » – « Il n’y a pas d’affaire Céline mais il y a certainement un cas Charbonnières, furieux petit diplomate halluciné de haine. » – « Les discours m’assomment, les danseuses m’ensorcellent. »

Un abonné m’écrit : « J’avais déjà lu et apprécié les cahiers de prison dans L’Année Céline, puis dans l’édition de Henri Godard avec fac-similés. J’ai pourtant l’impression d’en découvrir de nouvelles richesses dans les Cahiers Céline. Est-ce le format, la continuité du texte, la qualité des annotations de Jean-Paul Louis ? Toujours est-il que c’est à cette édition que je retournerai le plus volontiers, et je la recommande à tous les céliniens. » L’intérêt de cette édition se trouve ainsi parfaitement résumé. Si ce corpus était déjà connu des céliniens, le fait que toutes les parties en soient réunies en un seul volume constitue une heureuse initiative.Rappel des faits : c’est le 17 décembre 1945 que Céline est arrêté, les autorités françaises ayant demandé son extradition après avoir appris sa présence à Copenhague. Incarcéré à la prison de l’Ouest (essentiellement cellule 609, section K), Céline demande de quoi écrire. L’administration pénitentiaire lui fournit dix cahiers d’écolier de 32 pages avec comme consigne impérative de ne pas écrire sur l’affaire dont il est justiciable. Il n’en tiendra évidemment pas compte et, de février à octobre 1946, rédigera un ensemble de notes sur sa défense et ses accusateurs mais aussi sur d’autres sujets : épisodes de sa vie, conditions de réclusion, synopsis et esquisse pour des romans à venir, citations extraites de ses nombreuses lectures d’emprisonné qui lui permettent de tenir. Dans une préface éclairante Jean-Paul Louis relève que ces cahiers illustrent la transition célinienne vers ce qu’il nomme la « seconde révolution narrative et stylistique ». Laquelle s’engage par ce chef-d’œuvre, piètrement accueilli à son retour en France et encore méconnu aujourd’hui : Féerie pour une autre fois. Il faut saluer le soin avec lequel le texte a été établi et la qualité des annotations dont les connaisseurs avaient déjà en partie connaissance par trois livraisons de L’Année Céline, parues de 2007 à 2009. Comme on s’y attend, les formules incisives surgissent sous la plume du prisonnier. Florilège : « À Sigmaringen les réfugiés bouffent de la chimère » – « Moi aussi la Sirène d’Andersen m’a fait venir à Copenhague et puis elle m’a assassiné. » – « Je me sens tout à fait absous pour mes errements passés, mes cavaleries polémiques lorsque je vois avec quelle furie, quelle lâcheté, quelles effronteries, mes adversaires m’accablent à présent que je suis vaincu. » – « Je suis peut-être un des rares êtres au monde qui devraient être libres, presque tous les autres ont mérité la prison par leur servilité prétentieuse, leur bestialité ignoble, leur jactance maudite. » – « Pendant 4 ans il a fallu louvoyer au bord de la collaboration sans jamais tomber dedans. » – « Il n’y a pas d’affaire Céline mais il y a certainement un cas Charbonnières, furieux petit diplomate halluciné de haine. » – « Les discours m’assomment, les danseuses m’ensorcellent. »Marc Laudelout.

De ces cahiers de prison se dégagent beaucoup d’émotion et de rage mêlées. On imagine ce que cette incarcération a représenté pour Céline qui, de bonne foi, se considérait injustement traité. Ils constituent à la fois un document littéraire de premier ordre et une part intimiste de l’œuvre aussi poignante que révélatrice d’un être victime de son tempérament d’écrivain de combat.

• Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Cahiers de prison (février-octobre 1946), Gallimard, coll. « Les Cahiers de la NRF » [Cahiers Céline n° 13], 2019, 240 p. (Diffusé par le BC, 25 € frais de port inclus).

11:06 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, marc laudelout, revue, littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

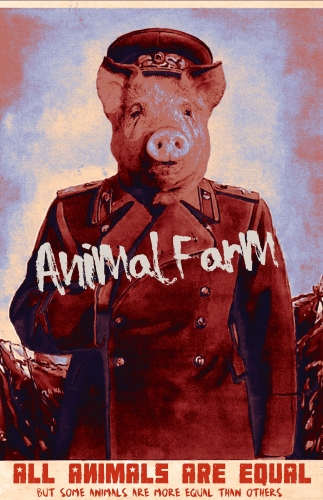

Connolly, Burnham, Orwell, & “Corner Table”

“In the torture scenes, he is merely melodramatic: he introduces those rather grotesque machines which used to appear in terror stories for boys.”

—V. S. Pritchett, The New Statesman [2], June 18, 1949

The torture section in Nineteen Eighty-Four[1] [3] was planned from the beginning, and intended to be the story’s core and culmination. The key influence here was James Burnham’s The Struggle for the World (discussed below), which George Orwell reviewed in March 1947, shortly before starting the first full longhand draft of the new novel. In Struggle, Burnham emphasized the likelihood of another World War within another few years, and probably even a war using the “atomic bomb.”

This found its way into Nineteen Eighty-Four, as did Burnham’s analysis of Communism (though Orwell didn’t call it that). Terror, torture, disinformation, humiliation: these are not unfortunate byproducts of Communist revolution, said Burnham, they are the system itself.

The original model for Nineteen Eighty-Four wasn’t as grim as that. It was frivolous, really, and written years and years before the Cold War was dreamt of. It was a little black comedy that used torture strictly for laughs. Titled “Year Nine,” Cyril Connolly dashed it off at the end of 1937.[2] [4] It appeared in The New Statesman in January 1938.

It’s a brief farce, less than two thousand words, yet in there are prefigured Big Brother, the Thought Police, Newspeak, and the Ministry of Love. To tell a brief story briefly: After happening upon a basement art exhibit, the narrator – an assembly-line envelope-flap-licker – is accused of thoughtcrime (approximately). He is arrested, severely tortured, and sentenced to excruciating execution.

Orwell was much impressed with it, and so were John Betjeman and others.[3] [5] Up to this point, Connolly was known mainly as an idler and failed novelist. Very soon, though, he published a memoir, Enemies of Promise, founded Horizon (“A Review of Literature & Art”), became editor of The Observer‘s book section (where he farmed out reviews to Orwell and Evelyn Waugh and Arthur Koestler), and was generally London’s number-one all-’round critic and litterateur.

From “Year Nine”:

As the hot breath of the tongs approached, many of us confessed involuntarily to grave peccadilloes. A man on my left screamed that he had stayed too long in the lavatory.

* * *

Our justice is swift: our trials are fair: hardly was the preliminary bone-breaking over than my case came up. I was tried by the secret censor’s tribunal in a pitchdark circular room. My silly old legs were no use to me now and I was allowed the privilege of wheeling myself in on a kind of invalid’s chair. In the darkness I could just see the aperture high up in the wall from whence I should be cross-examined . . .

Our narrator (not a Winston Smith type, more of a garrulous Connolly/O’Brien) is sentenced to be “cut open by a qualified surgeon in the presence of the State Augur.”

“You will be able to observe the operation, and if the Augur decides the entrails are favourable they will be put back. If not, not . . . For on this augury an important decision on foreign policy will be taken. Annexation or Annihilation? . . .

Yes, I have been treated with great kindness.[4] [6]

There is a cultural time-stamp on “Year Nine,” clearly visible. The Moscow Purge Trials were underway and widely known about, but Connolly pins the Stalinist outrages in his tale – torture, forced confessions, anonymous denunciations – upon a cartoonish pseudo-Nazi regime, complete with Stroop Traumas, Youngleaderboys, and a population in thrall to Our Leader. (Connolly hadn’t a political bone in his body, but he posed as a Fellow Traveler, that being comme il faut.)

Conversely, when Nineteen Eighty-Four came out in 1949, it too drew on the Moscow Trials, and no one questioned (least of all Pravda) that Orwell was depicting a Soviet-style police-state. This happened even though Orwell slyly denied that it was about Communism. You can see this in the novel’s own disclaimers, and in external press releases that author and publisher sent out.

A curious legacy of “Year Nine” is that its Punch-and-Judy brilliance shines through the surface narrative of Nineteen Eighty-Four, giving the torture scenes a lurid “vaudeville” feel. Orwell probably didn’t intend the scenes in the Ministry of Love (Miniluv) to be black comedy, but that’s what he got, from O’Brien’s jabberwocky speeches, all the way to the rats in the cage-mask. (“‘It was a common punishment in Imperial China,” said O’Brien as didactically as ever.’”)

Lord of Chaos

Connolly/O’Brien is your emcee and Lord of Chaos in the Miniluv torture clinic. This is far from the standar d crib-note interpretation of O’Brien (“zealous Party leader . . . brutally ugly”), but pray consider: a) Connolly was Orwell’s only acquaintance of note who came close to the novel’s description of O’Brien, physically and socially; b) if you bother to read O’Brien’s monologues in the torture clinic, you see he’s doing a kind of Doc Rockwell routine: lots of fast-talking nonsense about power and punishment, signifying nothing.

d crib-note interpretation of O’Brien (“zealous Party leader . . . brutally ugly”), but pray consider: a) Connolly was Orwell’s only acquaintance of note who came close to the novel’s description of O’Brien, physically and socially; b) if you bother to read O’Brien’s monologues in the torture clinic, you see he’s doing a kind of Doc Rockwell routine: lots of fast-talking nonsense about power and punishment, signifying nothing.

This is one reason why O’Brien fails as a villain. Villains must be monolithic. Here we have an Inner Party exemplar-cum-old Etonian who still boasts of his “antinomian tendencies” – a humorist and parodist, author of The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism as well as “Where Engels Fears to Tread”;[5] [8] in short, a louche Fellow-Traveler-of-convenience, renowned for self-indulgence and amorality. And thus he fits right in with what O’Brien tells us about the Inner Party ethos (do read the monologues): someone who’s amoral, capricious, and power-hungry (and a potential sociopath, if O’Brien’s description of the Party’s lust for power is anything to go by).

* * *

If Orwell wanted to put Connolly out of his mind while working on Nineteen Eighty-Four, he couldn’t, because he was forever revising an essay-memoir about the school they went to together between 8 and 14. It was the most miserable time of life for young Eric Blair (for such he was). He had probably started this memoir in the early 1940s, and still had the unpublished typescript with him in London when he was playing with notes and abortive chapters for his projected novel in 1945 and 1946. And then he brought it with him to the Isle of Jura, Inner Hebrides, in the spring of 1947, where he finally began to handwrite the first draft of The Last Man in Europe (as he was then calling the Winston Smith novel). He also revised the memoir, sending a carbon to his publisher in late May. Then, in 1948, when he was laid up with TB in a hospital near Glasgow and struggling to rewrite the novel with his writing arm in a cast, he revised the memoir yet again. It wouldn’t be published in Great Britain until 1967.

The memoir was Cyril Connolly’s idea. Connolly had put his fond-but-unnerving school memories into Enemies of Promise (which made him famous), and suggested his old schoolmate Blair might do the same: a companion piece or “pendant” to Connolly’s sardonic memoir. So Blair/Orwell decided to do a Dickens about his time as an upper-middle-class poor boy at St. Cyprian’s, enduring six years of oppression, humiliation, and petty tortures. He attended the school on reduced fees (as the Headmaster’s wife reminded him loudly and often) because he was expected to win a scholarship to Eton, and so bring glory and honor to St. Cyprian’s. From age 11 onward, Young Blair was “crammed with learning as cynically as a goose is crammed for Christmas” (as he wrote), mainly Latin and Greek.

This is the nearest thing to an autobiography we ever got out of Orwell, and the disgusted, sulky, sharp-eyed loner we see in his essays and Winston Smith is thoroughly recognizable as the boy at St. Cyprian’s. To make himself seem even lonelier and more miserable – or perhaps for some other motive – he cut Cyril Connolly entirely out of story.

At one point in the memoir, Orwell pulls back and says he doesn’t mean to suggest his school was a kind of Dotheboys Hall. Then he marches off again and tells us about the filthy lavatories and disgusting food, and how he once saw a human turd floating on the surface of the local baths in Eastbourne. On finally leaving St. Cyprian’s – off to Eton, but first a term at Wellington – he looked to the future with despair. “[T]he future was dark. Failure, failure, failure – failure behind me, failure ahead of me . . .”

Orwell’s publisher and friends thought the memoir was just too embarrassing and self-pitying to publish. It would be bad for Orwell’s reputation, they said, and probably libelous. So the perennial work-in-progress didn’t see the light of day until Orwell was safely dead and Partisan Review in New York ran a slightly altered version in their September-October 1952 issue. It ran for 41 pages, called St. Cyprian’s “Crossgates,” and used Orwell’s title: “Such, Such Were the Joys.”[6] [9]

* * *

You sometimes hear that Orwell plagiarized from another dystopian story, usually one set many centuries in the future, with little or no resemblance to Orwell’s. In 2009, on Nineteen Eighty-Four‘s sixtieth anniversary of publication, Paul Owen in The Guardian tried to make the case that Orwell “pinched the plot” from Yevgeny (or Eugene) Zamyatin’s early-1920s novel, We.[7] [10] As evidence, Owen says that Orwell read Zamyatin’s book three years before Nineteen Eighty-Four was published (1949). This is a lie by misdirection. Orwell had been making notes and outlines since at least 1944, and finished his first draft in 1947. He first heard of Zamyatin’s book in 1943, failed to find a copy of the 1920s English translation published in New York,[8] [11] and finally settled for a French one, his review appearing in early 1946.[9] [12] Owen’s biggest claim is completely wrong: “that Orwell lifted that powerful ending – Winston’s complete, willing capitulation to the forces and ideals of the state – from Zamyatin.” The ending of Nineteen Eighty-Four is in fact a retread of a novel ending that Orwell wrote in 1935.

A good deal of Nineteen Eighty-Four, in fact, is a twisted retelling of Keep the Aspidistra Flying.[10] [13] Orwell wrote Aspidistra in 1935 during his Hampstead bookshop-assistant days, and was ever after ashamed of it. Never mind, it’s a beautiful piece of pathetic self-mockery, giving us a 1930s-model Winston Smith. Instead of surrendering to Big Brother at the end, the Winston-figure, Gordon, finally sells out to the “Money God” – and goes back to his job as an advertising copywriter. A happy ending, strangely enough.

A good deal of Nineteen Eighty-Four, in fact, is a twisted retelling of Keep the Aspidistra Flying.[10] [13] Orwell wrote Aspidistra in 1935 during his Hampstead bookshop-assistant days, and was ever after ashamed of it. Never mind, it’s a beautiful piece of pathetic self-mockery, giving us a 1930s-model Winston Smith. Instead of surrendering to Big Brother at the end, the Winston-figure, Gordon, finally sells out to the “Money God” – and goes back to his job as an advertising copywriter. A happy ending, strangely enough.

In place of glowering Big Brother posters, Gordon is surrounded by vast images of “Corner Table,” a “spectacled rat-faced clerk with patent-leather hair,” grinning over a mug of Bovex. (Presumably Bovril + Oxo.) “Corner Table enjoys his meal with Bovex,” shouts the poster all over town. Everywhere Gordon is stared down by the Money God, in the guise of advertisements on all the hoardings. “Silkyseam – the smooth gliding bathroom tissue.” “Kiddies clamour for their Breakfast Crisps.”

Like Winston, Gordon is under constant surveillance at home (from his landlady) and takes his girlfriend out to the countryside, where they have sex on the wet ground. When he gets in trouble with the law, he wakes up in a jail with walls of “white porcelain bricks,” like the lockup at Miniluv. His O’Brien-analogue, an upper-class literary friend and little-magazine publisher named Ravelston, shows up and rescues him from the clink. Instead of taking him to a torture chamber, he puts Gordon up in his flat and gently badgers him to straighten out his life, which Gordon does eventually, but not just yet. Torture was different in the Thirties.

* * *

Connolly’s “Year Nine” provided an amusing, pocket-sized framework for building a terror-regime satire, while Keep the Aspidistra Flying gave the naturalistic “human” elements to be restyled for Nineteen Eighty-Four. The new novel also needed serious geopolitical underpinnings, and here Orwell leaned heavily on James Burnham. It’s long been known that Orwell took the “three super-states” idea from Burnham’s The Managerial Revolution (1941).[11] [14] Orwell and his publisher cited Burnham and that book when they wrote a press release in June 1949, explaining what Nineteen Eighty-Four was “about.” (Press interest was intense, and the hat-tip to Burnham looks suspiciously like a red herring.)

Burnham’s “three super-states” schema was the inspiration not only for Oceania-Eurasia-Eastasia, but most probably the entire novel; it was like a piece of grit in the oyster, waiting for the pearl to form around it. It became Orwell’s pet geopolitical concept, and from 1944 onward we find him continually dropping mentions of “three super-states” in his reviews, articles, and columns.

[15]Nevertheless, it was a later book by Burnham, The Struggle for the World (1947)[12] [16] that really gave Nineteen Eighty-Four its horror and worldview. Here, Burnham argued that another World War was likely soon (say, 1950), and something nuclear would probably be in play. This provided the backstory to Oceania’s murky history of war and revolution, along with some early memories for Winston Smith. An “atomic bomb” – as we called them then – was dropped near London in Colchester. Burnham argued that a preventive war might well be necessary before the Soviets get the A-bomb. The rush of events soon outran that warning, needless to say.

But the really vital input from Struggle came from Burnham’s analysis of Communism. International Communism really, truly, does seek mastery of the globe, he maintained. He had made the argument a couple of years earlier, when he was with the OSS, but in 1947 it became the freshest insight in US foreign policy. Furthermore, he focused on a matter that most pundits feared to address, lest they look like unhinged extremists: the integrality of terror to the Communist apparatus. This was obvious to many people in those post-war years, but it was Burnham who took the logical leap and articulated the idea in a book: If your main activity is terror, then terror is your business.

To repeat the obvious, Burnham was describing Communism, not some theoretical “totalitarianism,” as in some press blurbs for Nineteen Eighty-Four. As noted, Orwell explicitly disavowed any connection between his fictional “Party” and the Communist one. Nevertheless, the political program that O’Brien boasts about to Winston Smith is the Communist program à la James Burnham. It’s exaggerated and comically histrionic, but strikes the proper febrile tone.

To repeat the obvious, Burnham was describing Communism, not some theoretical “totalitarianism,” as in some press blurbs for Nineteen Eighty-Four. As noted, Orwell explicitly disavowed any connection between his fictional “Party” and the Communist one. Nevertheless, the political program that O’Brien boasts about to Winston Smith is the Communist program à la James Burnham. It’s exaggerated and comically histrionic, but strikes the proper febrile tone.

First, some O’Brien:

Power is in inflicting pain and humiliation. Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing. Do you begin to see, then, what kind of world we are creating? It is the exact opposite of the stupid hedonistic Utopias that the old reformers imagined. A world of fear and treachery is torment, a world of trampling and being trampled upon, a world which will grow not less but more merciless as it refines itself. Progress in our world will be progress towards more pain. . . .

The espionage, the betrayals, the arrests, the tortures, the executions, the disappearances will never cease. It will be a world of terror as much as a world of triumph. The more the Party is powerful, the less it will be tolerant: the weaker the opposition, the tighter the despotism.[13] [17]

Now bits of Burnham:

The terror is everywhere, never ceasing, the all-encompassing atmosphere of communism. Every act of life, and of the lives of parents, relatives and friends, from the trivial incidents of childhood to major political decisions, finds its way into the secret and complete files. . . . The forms of the terror cover the full range: from the slightest psychological temptings, to economic pressure . . . to the most extreme physical torture . . .

* * *

It should not be supposed that the terror . . . is a transient phenomenon . . . Terror has always been an essential part of communism, from the pre-revolutionary days . . . into every stage of the development of the communist regime in power. Terror is proved by historical experience to be integral to communism, to be, in fact, the main instrument by which its power is increased and sustained.[14] [18]

Burnham and Orwell were of very different mentalities, the first always gushing theories with the fecundity of a copywriter dashing off taglines; while the second was constitutionally averse to abstractions and hypotheticals, much preferring near-at-hand things, such as the common toad. It’s striking that Orwell could not only find something useful and intriguing in Burnham, he honored him with a few of the most insightful and appreciative critiques.

In March 1947, while getting ready to go to Jura and ride the Winston Smith book to the finish even if it killed him (which it did), Orwell wrote his long, penetrating review of The Struggle for the World. He paid some compliments, but also noted some subtle flaws in Burnham’s reasoning. Here he’s talking about Burnham’s willingness to contemplate a preventive war against the USSR:

In March 1947, while getting ready to go to Jura and ride the Winston Smith book to the finish even if it killed him (which it did), Orwell wrote his long, penetrating review of The Struggle for the World. He paid some compliments, but also noted some subtle flaws in Burnham’s reasoning. Here he’s talking about Burnham’s willingness to contemplate a preventive war against the USSR:

[Burnham sees that] appeasement is an unreal policy . . . It is not fashionable to say such things nowadays, and Burnham deserves credit for saying them.

But suppose he is wrong. Suppose the ship is not sinking, only leaking. Suppose that Communism is not yet strong enough to swallow the world and that the danger of war can be staved off for twenty years or more: then we don’t have to accept Burnham’s remedy – or, at least, we don’t have to accept it immediately and without question.[15] [19]

Orwell was just using moderation and common sense here, but what he’s suggesting is what in fact began to happen that year (1947). Instead of the predicted war of destruction; policies of “containment,” “rollback,” “interventions”; defense treaties (NATO); and targeted economic aid (Marshall Plan) might work at least as effectively against the Soviets, as well as being far pleasanter and more manageable.

Ironically, Orwell did not pay much attention to what was going on in the outside world that year or next; he had bigger things to worry about. But as the world moved on, it diverged more and more from the fundamental premises of Nineteen Eighty-Four. There wouldn’t be an “atomic war” in 1950 (war, yes; not atomic) and Soviet-style terror regimes weren’t going to swallow all of Europe, however likely that looked in the spring of 1947.

Notes

[1] [20] The actual title of the book on publication date was Nineteen Eighty-Four in London (Secker & Warburg) on June 8, 1949; and 1984 on June 13, 1949 in New York (Harcourt Brace). Orwell and his publisher slightly preferred the numerals, but chose to go with the words for the London edition. Orwell used both styles interchangeably – obviously one is more convenient to type. (George Orwell: A Life in Letters, Ed. Peter Davison [London: W.W. Norton], 2010.)

[2] [21] Cyril Connolly, “Year Nine,” collected in The Condemned Playground (London: Routledge, 1945), originally published in The New Statesman, January 1938. Connolly was inspired by a visit to the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich, where he got the uneasy sense he was expected to leer with a disapproving expression.

[3] [22] Clive Fisher, Cyril Connolly (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995).

[4] [23] Connolly, The Condemned Playground.

[5] [24] Connolly, The Condemned Playground.

[6] [25] George Orwell, “Such, Such Were the Joys,” Partisan Review, Vol. 19, No. 5 (New York), Sept.-Oct. 1952.

[7] [26] Paul Owen, “1984 thoughtcrime? Does it matter that George Orwell pinched the plot? [27]”, The Guardian, 8 June 2009.

[8] [28] E. (or Y.) Zamyatin, We, tr. Gregory Zilboorg (New York: E. P. Dutton), 1924. This English-language edition was actually the first publication of We.

[9] [29] George Orwell, review of We, Tribune (London), January 4, 1946.

[10] [30] George Orwell, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, many editions. Originally: London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1936.

[11] [31] James Burnham, The Managerial Revolution (New York: John Day, 1941).

[12] [32] James Burnham, The Struggle for the World (New York: John Day, 1947).

[13] [33] Nineteen Eighty-Four, Part III, iii.

[14] [34] James Burnham, The Struggle for the World (New York: John Day, 1947).

[15] [35] George Orwell, “James Burnham’s view of the contemporary world struggle,” New Leader (New York), March 29, 1947.

00:10 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : george orwell, dystopie, littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise, histoire, james burnham |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: https://www.anthonyburgess.org

Anthony Burgess came of age as modernism was at its peak, and the movement influenced much of his writing. As a reaction against the realism of the late nineteenth century, modernist works of literature aimed to disrupt many of the established tenets of novel-writing and poetry. In novels, the omniscient narrators, the linear structures and the focus on external description of environments and characters were replaced with subjectivity, fractured plotlines and a focus on the internal thoughts of characters (the latter inspired by the rise in psychoanalysis of the early twentieth century). Modernist poets rejected the devices of the Romantic period, preferring to experiment with form, allusion and the patchwork technique of using many fragmented languages and registers. The whole modernist project could be summed up with Ezra Pound’s phrase ‘make it new’.