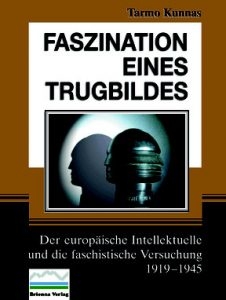

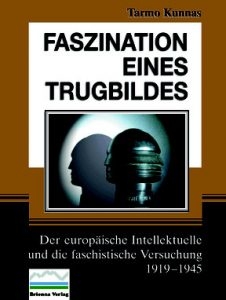

Tarmo Kunnas

Faszination eines Trugbildes: Die europäische Intelligenz und die faschistischeVersuchung 1919-1945

Brienna Verlag, 2017

Faszination eines Trugbildes (The Fascination of an Illusion) by Tarmo Kunnas is an unusual book in several respects. It sets out to examine what in the subtitle to the book is described as “the European intellectual and the fascist temptation, 1919-1945.” “Here,” Kunnas explains, “the tragedy of fascism is seen through the opera glasses of the person it has captivated, and my book for its part is intended to complete a picture of the fascist movements.” (p. 9) In his Foreword, Kunnas tells us that his book deals with the relationship of more than seventy European intellectuals from fifteen nations who were “tempted” by fascism.

Faszination eines Trugbildes (The Fascination of an Illusion) by Tarmo Kunnas is an unusual book in several respects. It sets out to examine what in the subtitle to the book is described as “the European intellectual and the fascist temptation, 1919-1945.” “Here,” Kunnas explains, “the tragedy of fascism is seen through the opera glasses of the person it has captivated, and my book for its part is intended to complete a picture of the fascist movements.” (p. 9) In his Foreword, Kunnas tells us that his book deals with the relationship of more than seventy European intellectuals from fifteen nations who were “tempted” by fascism.

The writer is Finnish, and this lengthy work of over seven hundred pages was first published in Finnish as Fasismin Lumous (The Enchantment of Fascism) in 2013, translated into German, and published by Brienna Verlag, a small, Right-wing German language publishing house, in 2017. Two works on Friedrich Nietzsche by Kunnas have previously been published by the same imprint. Indeed, Kunnas has had several of his works published in French and German, and yet there has been nothing to date in English. Is the potential interest in the subject reckoned to be so low among the potentially much larger Anglophone readership?

The translation under review was subsidized by a body called the Finnish Literature Exchange, a non-profit organization which helps Finnish writers by bearing some of the costs of translating, printing, and publishing their works in other languages. It is interesting that this book has so far found no English-language publishing house willing to take on the commercial risk of issuing such a wide-ranging study of fascist thinkers.

Kunnas does not take the reader through the customary knee-jerk procedure almost mandatory when writing about fascist writers and intellectuals, which is to say that he refrains from intimating that the writers studied here are not intellectuals or thinkers in the true sense of the word by using the supercilious quotation marks around those terms that are dear to the professional mainstream critic, indicating that the said critic is impervious to the blandishments of the fascist beast. This book is mercifully free of this and other anti-fascist “health warnings.”

The German title of Kunnas’ book raises a question. The word Trugbild has a mainly negative connotation in German. A more obvious translation, assuming the online dictionary translations of lumous are correct and correspond to the Latin root, might be “illusion,” or Täuschung in German; lumous can apparently also mean something like “chimera,” “illusionary dream,” or “delusion”; likewise “charm,” “spell,” or “dream.” There is a considerable difference between the fascination of a charm and the fascination of an illusion. This is not quibbling, for while Kunnas is well-focussed when he examines and quotes the political statements of the many writers he considers here, he is (deliberately?) ambiguous when it comes to his own approbation or otherwise of “fascist temptation.” Calling this work Trugbild tilts it in the direction of a negative interpretation.

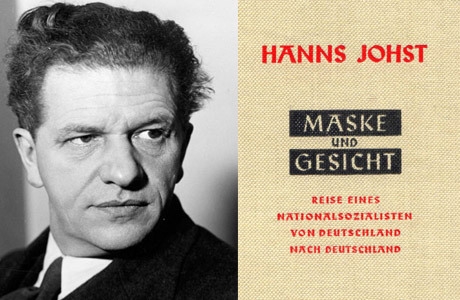

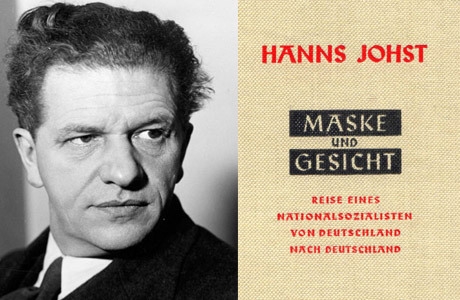

In this book, Kunnas seeks to provide a wide-ranging overview of the writings of creative writers and philosophers in the inter-war years who felt attracted in at least some respects to fascism. They include Gottfried Benn, Robert Brasillach, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Hanns Johst, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, Alphonse de Chateaubriant, Emil Cioran, Wyndham Lewis, Filippo Marinetti, Örnulf Tigerstedt, Knut Hamsun, Martin Heidegger, and many more. There are, perhaps inevitably, omissions likely to surprise: D. H. Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, and Evelyn Waugh receive hardly a mention. While Scandinavian countries are well-covered, as is to be expected, with the exception of Romania, Central European writers hardly feature at all. This is probably owing to Kunnas’ personal familiarity with Scandinavian writers and his ignorance of Central European languages, but it creates doubt as to whether this work constitutes a balanced assessment. Did Hungary and Bulgaria have no intellectuals of note to merit inclusion?

In his Foreword, Kunnas says his objective is to examine “why fascism in the inter-war years held such attraction for the European intelligentsia and on the people of the time.” In fact, this study does not look at the attraction fascism held for people in general; it focuses exclusively on writers. The organization of the book is unusual. Instead of covering his ground with chapters devoted to specific writers or nations, Kunnas works through chapters which revolve around given themes, and then scrutinizes in each an array of writers in relation to its theme. Here are the titles of a few of the many chapters: “Exactness is not Truth,” “Mistrust of the Good in People,” “Social Darwinism,” “Puritanism,” “The Weakness of Parliamentarianism,” and “Against Faith in Progress.” For each of these, Kunnas provides the reader with an abundance of examples of how, within the perspective of the given theme, many intellectuals inclined towards fascism and a fascist solution, or towards an interpretation of the theme. This unusual approach has the advantage that it shifts focus from a biographical account to a philosophical and theoretical one so that the reader is compelled to think about the matter at hand firstly, and about the writers and thinkers drawn to it secondly; that is to say, he looks at the subject in respect of the theme itself and how fascist thinkers and fascist thought approached and evaluated each given theme. This is an original alternative to the standard presentation in critical assessments of the relation of writers to certain themes, as in potted biographies and the organization of such books into the intellectual, political, and literary career of one writer per chapter.

In his Foreword, Kunnas says his objective is to examine “why fascism in the inter-war years held such attraction for the European intelligentsia and on the people of the time.” In fact, this study does not look at the attraction fascism held for people in general; it focuses exclusively on writers. The organization of the book is unusual. Instead of covering his ground with chapters devoted to specific writers or nations, Kunnas works through chapters which revolve around given themes, and then scrutinizes in each an array of writers in relation to its theme. Here are the titles of a few of the many chapters: “Exactness is not Truth,” “Mistrust of the Good in People,” “Social Darwinism,” “Puritanism,” “The Weakness of Parliamentarianism,” and “Against Faith in Progress.” For each of these, Kunnas provides the reader with an abundance of examples of how, within the perspective of the given theme, many intellectuals inclined towards fascism and a fascist solution, or towards an interpretation of the theme. This unusual approach has the advantage that it shifts focus from a biographical account to a philosophical and theoretical one so that the reader is compelled to think about the matter at hand firstly, and about the writers and thinkers drawn to it secondly; that is to say, he looks at the subject in respect of the theme itself and how fascist thinkers and fascist thought approached and evaluated each given theme. This is an original alternative to the standard presentation in critical assessments of the relation of writers to certain themes, as in potted biographies and the organization of such books into the intellectual, political, and literary career of one writer per chapter.

However, there is a significant downside to this approach. Because the writer is necessarily drawing attention to individuals by pointing to their writing, and the books abound with quotations from primary texts, in each chapter Kunnas is compelled to switch abruptly from one writer to the next in the context of the theme. Thus, the reader has the experience of being constantly “jolted” from one writer to the next, thrown from the quotations of one writer into quotations from the next. Kunnas is like a conjurer, pulling one writer out of his hat after the other, not giving the reader time to consider one writer’s relation to a theme before the next writer is presented for consideration. The book more closely resembles a collection of examples and quotations than a balanced thesis or study. This reviewer felt mentally seasick after being constantly driven from one writer to the next. Here is a brief example of Kunnas’ style:

Jünger’s thought was free from the race-mysticism of the National Socialists, and even as a nationalist, he was open to outside influences. In this respect, he was closer to young Italian Fascists than to his National Socialist compatriots. It is a historical paradox that those very young Italians had lifted their battle cry against Jünger’s fatherland. There was no question of inter-fascist solidarity then.

Hans Grimm displayed social Darwinism in his essays and in his novel Volk ohne Raum. Any nation has a right which it can seize by force. Strong nations respect one another, but weak peoples earn no respect. (p. 266)

The last remark in this example is provided with a reference to Hans Grimm’s work. This brings me to another unusual feature of this book, one in which I see no advantage. Instead of reference numbers taking the reader to the name of the work and page number cited as is customary, the reader is taken to a name and date – in this case not Grimm, but someone called Gümbel, and from there to another number, which is the page number from which the quotation is taken in Gümbel’s work, listed under another index of writers. Finally, the patient reader will discover that the quotation is from page 115 of a work by Annette Gümbel that was published in Darmstadt in 2003 by the Hesse Historical Commission. Every reference in the book involves a “redirection” of this kind from page reference to source.

Faszination eines Trugbildes lies uneasily between an academic study and a handbook, but fails to convince as either. There are too many references and abrupt changes of theme and writer for this long essay to remain cogent, yet there is too much lengthy philosophical discourse for it to serve as a handy, practical reference work. It is nevertheless a mine of new information about different writers, especially Scandinavian writers who suffer from that obscurity which is liable to be the fate of those whose mother tongue is not known by many people. Not only does Kunnas write at length on Knut Hamsun, but also on much less-known writers from the North such as Sven Hedin, Loavi Paavolainen, Örnulf Tigerstedt, and Maila Talvio. The philosophical discourses in this book, as for example on Martin Heidegger, are intelligent and informative and largely free of retrospective value judgements.

Nevertheless, the book fails to clearly define who qualifies for inclusion in the work and who does not. It seems that any reasonably well-known European author or philosopher whose most famous writing (practitioners of other arts, such as architecture or music, are not covered) appeared between 1918 and 1945, and who was in at least one respect sympathetic to either Italian Fascism or German National Socialism, qualifies. This ambitious study thus centers on the relationship between fascism, philosophy, and literature, and the attraction the fascist movements held for intellectuals, in the inter-war years. Its assessment of literature falls short, however, when compared to its assessment of political theory. Kunnas seems much more comfortable in the role of political commentator than literary critic. While he ably describes the manner in which particularly irrational or anti-rational thought easily morphs into fascism (and there are times when Leftists would approve of his analysis), he is not very convincing in showing the extent to which this is reflected in literature.

Kunnas collects information like a magpie, and he offers a vast collection of quotations which he liberally scatters throughout the book. But while his assertions concerning views expressed didactically by writers in his study are supported by quotations from original texts, Kunnas much more rarely quotes from poetry or fictional works. He quotes at length from political statements by such writers as Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Luigi Pirandello, and Henry de Montherlant, but hardly ventures into the world of their plays, poems, or novels. But isn’t it their creative work and not their political theses for which these writers are justly revered and remembered? Most of the writers studied here were firstly creative writers, although from reading this book one might be forgiven for supposing that they were mainly political theorists who used creative writing only as a welcome vehicle for their political ideas.

The novelists and poets covered by Kunnas overlap with many writers who are frequently mentioned – typically with brief approval – in the publications of the European New Right. The European New Right is more inclined to praise writers for their political engagement than for their merits as writers. Indeed, their publications tend to highlight creative writers who happen to be broadly in the same political orbit without feeling it incumbent upon them to argue for their literary merits. But why should a Right-winger presume that D. H. Lawrence, for instance, is a “better” or less “decadent” writer than E. M. Forster only because Lawrence’s ideas are more in accord with his own? This is merely the usual Leftist bias in reverse. It is no different from the obtuseness of the novelist Patrick O’Brian, who once told this reviewer that he did not consider Drieu La Rochelle a serious writer because he had been a fascist, and that “nobody with anti-humanist views is capable of writing a good novel.” This attitude prevails in schools and university literature courses. Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus are standard syllabus fare for French literature courses; Robert Brasillach and Drieu La Rochelle are not. Thus, the objective assessment of literary merit is sacrificed on the altar of political bias.

Anyone looking in Faszination eines Trugbildes for praise or even a defense of the writers studied in it, either as exponents of a specific political point of view or as highly talented creative writers, will be disappointed. What Kunnas does is to go primarily to neglected writers and examine the specifically “fascist” aspects of their writing while ignoring the rest – not with a view toward condemning or praising them, but to examine the correspondence between their own beliefs and the tenets of fascism. It can even be argued that by doing so, Kunnas is providing supportive evidence to those who wish to keep the likes of Brasillach and Drieu La Rochelle off the academic syllabi. Some of the quotations provided make the intellectuals cited sound very extravagant. Their words have not been taken out of context in an obvious sense, but the quotations mainly come from writings penned with a sense of urgency spurred by the approaching war, in which intellectuals felt compelled to take sides. But most of the writers presented are remembered primarily for their literary achievements, not for their political statements of faith. If Kunnas wrote a comparable study of intellectuals and the “Communist temptation,” would he comment at length on J. B. Priestley’s statements in praise of Stalin while ignoring Time and the Conways? Would he raise his critical eyebrows at George Bernard Shaw’s suggestion that certain criminals be put to sleep in their beds at a time of the state’s choosing, in a study in which he hardly mentioned St. Joan or Pygmalion?

Here is Kunnas writing on Pirandello in a chapter revealingly entitled “Mistrust of the Good in People”:

The image of man which the Nobel Prizewinner Luigi Pirandello presents in his novels and plays is frequently described with negative attributes. His figures are recognized as impressionistic, tragic, even nihilistic, and he has been alleged to despise humanity. The protagonists in Pirandello’s novels and plays are often close to grotesque . . . (p. 179)

Here, in contrast to all references to what artists and intellectuals wrote in the form of opinion or broadsheet, no quotation is offered, either from Pirandello’s own works or from those critics who Kunnas claims regarded the characters in Pirandello’s drama as “close to grotesque.”

What is common in the “fascist temptation” which links the many European intellectuals and writers studied in this book? In a chapter entitled “Compensating for the Versailles Treaty of Disgrace,” Kunnas refers (pp. 73-74) to Armin Mohler’s well-known Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland, which Mohler himself described as a “handbook of German conservatism between 1918 and 1933,” a work which may have given Kunnas the idea for writing Faszination eines Trugbildes. Mohler identified five groups or tendencies in German conservatism, which embraced lovers of nature and futurists, Christians and pagans, staunch conservatives and “National Bolsheviks” in their entirety. Mohler identified characteristics common to what were in many respects contradictory and rival currents: a positive notion of homeland, a dismissal (or at the very least distrust) of parliamentarianism, and a rejection of the rule of lucre; and he might have added what I would take to be a key element for any writer remotely sympathetic to fascism: a denunciation of decadence. These (including a sense that society is in decline or has become decadent) are the points of departure in Kunnas’ work, and to these may be added many subjects treated chapter by chapter, among which the tendencies which Kunnas views as being the most important for disposing an intellectual toward fascism are puritanism, aesthetics, and a willingness to sacrifice oneself for a higher end beyond oneself.

Kunnas is good at highlighting contradictions and paradoxes which abound in fascist theory. How does an avowed Roman Catholic like Giovanni Papini, for example, reconcile his religious faith with the evident amoralism and ruthlessness of the militaristic foreign policy enacted by the Fascist government which he so ardently supported? By way of answer, according to Kunnas (p. 358), Papini’s early work Il tragico quotidiano (The Daily Tragic) accepts the notion that evil is a necessary part of God’s creation, and that without sin, there could be no poets, artists, or philosophers; indeed, no leaders of a people and no heroes. Vice may be the necessary condition of virtue, and evil may need to exist in order for good to do so likewise. Kunnas does not go far down the thorny and well-trodden theological path of speculation which he opens here. However, he is well aware of this and other conundra and contradictions within fascist thought, including in the writings of those intellectuals who were attracted by fascism, especially the notion that the warring poles of good and evil, war and peace, and pain and pleasure constitute the very fabric of life.

Kunnas is good at highlighting contradictions and paradoxes which abound in fascist theory. How does an avowed Roman Catholic like Giovanni Papini, for example, reconcile his religious faith with the evident amoralism and ruthlessness of the militaristic foreign policy enacted by the Fascist government which he so ardently supported? By way of answer, according to Kunnas (p. 358), Papini’s early work Il tragico quotidiano (The Daily Tragic) accepts the notion that evil is a necessary part of God’s creation, and that without sin, there could be no poets, artists, or philosophers; indeed, no leaders of a people and no heroes. Vice may be the necessary condition of virtue, and evil may need to exist in order for good to do so likewise. Kunnas does not go far down the thorny and well-trodden theological path of speculation which he opens here. However, he is well aware of this and other conundra and contradictions within fascist thought, including in the writings of those intellectuals who were attracted by fascism, especially the notion that the warring poles of good and evil, war and peace, and pain and pleasure constitute the very fabric of life.

Kunnas quotes many passages from these writers in which they proclaim their distrust or even outright rejection of rationalism. The lodestar here is Nietzsche, whose rejection of God and declaration of an ethic “beyond good and evil” provides the fertile ground out of which various projections of anti-rational faith have sprung. Another glaring contradiction here is between the anti-rationalist justification of emotions such as patriotism and the positivism which is at the heart of the case for racial differences, which humanist thought all over the world dismisses out of the deeply irrational rejection of the possibility that races are fundamentally different.

On the whole, however, Kunnas does not spend much time or effort on differences within fascist thought, and this is a major weakness of his study. He hardly examines at all the gulf which separates those who believe in God from those who seek a return to the pagan gods, as well as those who believe in no gods at all but who hold that life is absurd, or else that force is proof of worthiness. All these aspects are examined in this work, but they are not positioned against one another. Kunnas does not seem interested in doing more than noting the wide-ranging views on such subjects among those he studies. For example, there is no discussion or contrasting of intellectuals who were drawn to fascism for conservative or Christian rationales such as Alphonse de Chateaubriant, who welcomed Fascism as the means to restore the old order, and those like Marinetti, who were sympathetic to Fascism for the exact opposite reason: Fascism as the means to destroy the old order. In scarcely one of the scores of examples and citations Kunnas provides would I take specific issue with what is stated, but I do wonder if Kunnas can see the ideological wood for all the thematic trees he painstakingly examines.

Faszination eines Trugbildes abounds with observations which are undoubtedly true about the writers examined, and which are often supported by excerpts from their works. At the same, there are many observations and remarks which at the very least need to be properly explained and not, as they are often here, thrown in as one more accumulative fact. In writing about Céline, for instance, Kunnas makes the entirely valid point that there is a contrast between the amorality, fanatical callousness of Céline’s support for the National Socialist attacks on Poland and the Soviet Union and the human empathy which is evident throughout his novels. Kunnas leans in favor of the more diabolical Céline, however, by concentrating on his polemical writing and hardly quoting from his literary work at all. Apparently not seeing anything further to discuss here, Kunnas moves on to make a more general statement about Drieu La Rochelle, and then moves on again to make a general comment on Nietzsche. Here is the passage (another example of the kind of abrupt style of writing characteristic of this work):

Sporadically, another Céline appears to the hard and amoral one, a Céline mellow and humane, even when he conceals this behind caricature, exaggeration, and mask. Drieu did not have any such compensatory personality, but he did have aristocratic magnanimity and pride, which can also be found in another form in Henry de Montherlant.

By the time of Nietzsche at the latest, humanitarian rhetoric in the European literary tradition had been put in a bad light. Alongside the inflated moralizing, we see an aesthetic of hardness, one which virtually all of fascism’s fellow travellers drew upon. (p. 370)

This study casts its net too wide. It seeks to be a reference work, a collection of essays on fascist writers providing a broad outline of the relation of fascism to certain strands of artistic and intellectual thought. It partially succeeds in all these aims, but wholly succeeds in none of them.

Exhaustively, and at least for this reviewer exhaustingly, Kunnas examines writer after writer in order to throw up evidence of key elements of fascism, including among other things a notion that life is perpetual struggle, leading to a willingness to accept the inevitability of war, an identification of liberalism with decadence, a rejection of materialism accompanied by some kind of religious notion of a “higher sense” to life, a welcoming of austerity in life, a love of discipline and what might be crudely summarized as the belief that there if there is “no pain” there is “no gain,” a rejection of the belief that all men are equal, and a deep distrust or rejection of democracy. What does Kunnas himself think of all this? While there seems to be some lingering sympathy with Fascism in him, there seems to be little or none for National Socialism. Writing about the German playwright Hanns Johst, Kunnas has this to say:

Here, Johst’s rejection of liberalism and intellectualism is evident. Johst was fired with the belief that he stood in the middle of a permanent social Darwinian struggle . . . Johst’s attitude had taken him into the dead-end of National Socialism. (p. 324)

In a later comment on Johst, Kunnas notes that he:

. . . seems to have all too readily believed in the existence of various self-sufficient races, even when he described these in terms of cultural, and not biological, entities. (p. 461)

This implicitly critical assessment of Johst’s position on race (a position which can hardly be characterized as exclusively National Socialist) strongly suggest that Kunnas himself does not believe in the existence of biologically distinct human races. Who can say? Since his work is conceived as an objective academic examination of a trend, Kunnas is able to evade the responsibility of taking a position on the subject himself. But at least we can be grateful that this work is no hatchet job. Any writer undertaking this task who works for a living in the halls of academia, or who enjoys power and prestige in the West, would have been obliged to issue intermittent anathema throughout the book upon these naïve victims of the fascist Comus in order to ensure readers and publishers that he was not for a moment seduced by the subjects of his study. Had Faszination eines Trugbildes been published by a mainstream or academic publisher, it would have required drastic “revising” in order to slant the entire work to read as a cautionary exercise. Fortunately, it is free of sermonizing.

By noting many contradictions and differences among his writers, Kunnas implicitly accepts that the term “fascist” defies adequate definition. Although most fascist thinkers share most points of view on a given array of topics, no fascists share the same point of view on any one topic. Most fascists accept the necessity of struggle, and by extension, that war is an inherent facet of life, and on this basis they will accuse pacifists of “naïvety,” but even here there is not unanimity: Henry Williamson was undoubtedly a pacifist, as Sir Oswald Mosley professed to be on the basis of his experiences in the trenches; and Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night famously ridicules war.

There is a paradox, if not hypocrisy, here: While fascist writers criticize war when carried out by democracies or in the name of democracy, most of them praise what they see as the sacrifice and creative nobility of war. Dulce et decorum est pro patriae mori? Wilfried Owen did not think so, and Ezra Pound echoed anti-war sentiments in his own poetry, although Pound, unlike Owen, had never risked his life in combat.

Kunnas is painstaking in pointing out the differences and quoting from numerous primary sources to make his points. He is able to uncover many other contradictions, as for example between Ezra Pound’s contempt for utilitarianism and hyper-efficiency in contrast to the economic rationality of National Socialist Germany, for which Pound never expressed, so far as I know, great enthusiasm. However, two writers who might be – and, indeed, frequently have been – brought into association with “fascist tendencies,” or who were, to use Kunnas’ words, “tempted by fascism,” namely Ludwig Klages and D. H. Lawrence, were both anti-militarist. Nevertheless, they receive hardly a mention in this book. They are only drawn indirectly into this study to be briefly mentioned in an account by Kunnas of the Jewish and Marxist writer Ernst Bloch’s assessment of C. G. Jung. The comment is used more to underline a recurring stress which Kunnas puts on the fact that fascist views lean strongly towards a negative rejection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century optimism regarding progress than to offer any insight into the thought-processes of either Klages or Lawrence themselves:

The aborigine’s primitive subconscious, as understood by Jung, Klages, and D. H. Lawrence, had apparently unsettled Bloch’s optimistic faith in the development and future of humanity. (p. 187)

There is also a cryptic remark regarding the modern reader, with a peculiar reference to his “ideological determinism,” which presumably means, “Don’t think that just because someone loves their country, they are fascist”:

It may be hard for the modern reader, subjected to ideological determinism, to grasp that it was possible to stress a sense of kinship with homeland, family, and tribe, without being a National Socialist. (p. 464)

This comment provides a clue as to the writer’s own views, which seem to be that many of the sentiments felt by the many writers examined are praiseworthy, but when taken too far, or if caricatured and divested of moderating elements, might tempt the person having such sentiments into fascism or, even worse, the “dead-end” of National Socialism:

. . . National Socialism was a fraudulent, unscientific, overweening doctrine of race, not to be compared with the mystical yearning which, for example, could be felt in the art, poetry, and music which emerged at the end of the nineteenth century. (p. 187)

All the failings of this book notwithstanding, it would be ungracious not to acknowledge the huge amount of work which Kunnas has put into this sweeping account of the views of scores of writers. I know of no other single work which comes near to capturing and quoting so many fascist or fascist-inclined writers. However, I was nevertheless dissatisfied. I found myself all the time wanting to return to primary sources as opposed to being presented with “bleeding chunks” of essays, novels, and poems. Besides, I find the creative writing of a Drieu La Rochelle or Henry de Montherlant more interesting than their political essays, and as I have mentioned, this book is weighted heavily in favor of theoretical over fictional writing, particularly so far as quotations are concerned. Of course, it is considerably easier to measure theoretical or even philosophical writings against fascist preoccupations than it is to measure creative works against them. In the case of fiction or poetry, it is easy to overlook that what may have been fascist preoccupations were common themes and preoccupations of the time as a whole. For example, the ideal of Blut und Boden (blood and soil), which is so strongly associated with National Socialism, was in fact coined in Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West as an ideological rallying cry in opposition to Blut und Eisen (blood and iron). It was a strong theme in much European fiction, and not necessarily of writers “tempted by fascism” at all.

There is also the case of the French novelists Jean Giono and Henri Bosco, who were very much alike, both having Italian roots, and the setting of their novels in both cases having been Provence (many people willingly confess to confusing these Rosencrantz and Guildensterns of French literature!). Their novels are characteristic expressions of the virtues of, if not blood, very definitely soil. Neither writer could be described as “fascist.” Henri Bosco is not mentioned once by Kunnas (either because he never expressed a political opinion in writing which could be construed as sympathetic to fascism, or presumably because Kunnas detects no tendencies worthy of note in Bosco’s novels), and Giono only briefly, being given a “get out of jail” ticket with these words:

The National Socialist Blut und Boden idea had never been absorbed by Giono in a racialist form, as little as Heidegger on the other side of the frontier had done. Giono displayed a loyalty to the province [Treue gegenüber der Provinz], which had nothing to do with racism. (p. 91)

This attempt to exonerate Giono recalls the efforts made by most commentators and critics to exculpate writers who they acknowledge to be good writers, but who they know were for a time implicitly sympathetic to fascism (as, for example, D. H. Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, and Henry de Montherlant). Where such sympathies are explicit and cannot be ignored, as in the case of Ezra Pound, Knut Hamsun, Martin Heidegger, or Gottfried Benn, then effort is made to stress words such as “temptation,” “error,” “poor judgement,” and “naïvety” to exculpate the writer in question from the most serious charge of having been earnestly committed to an ideology which is now condemned without appeal by all “civilized opinion” as “the face of barbarism.”

Although scrupulously fair in allowing the subjects of his study to have their say (one reason that this book is so long is that Kunnas quotes his writers frequently and at length), Kunnas is so focussed on the individual assertions and pieces of writing which confirm the pattern which unfolds that he ignores the wider contexts of a writer’s total opus, as well as the movements of the time. Neither E. M. Forster nor Alain Fournier receive a mention here, but Howard’s End is arguably a plea for the essential values of Blut und Boden, while Alphonse de Chateaubriant’s La Réponse du Seigneur (The Lord’s Answer) -“tout est rêve dans la jeunesse, sauf la faim” (“all of youth is a dream save hunger”) calls to my mind, at least, Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes (The Lost Domain). Yeats’ “Second Coming” (p. 218) is quoted, but not his “Prayer for My Daughter,” which has lines warning against the preachers of hatred:

If there’s no hatred in a mind

Assault and battery of the wind

Can never tear the linnet from the leaf.

An intellectual hatred is the worst,

So let her think opinions are accursed.

Kunnas’ book is certainly not an “anti-fascist” work, but it shares with resolute “anti-fascist” writing the determination to highlight all aspects of each writer’s work which can be put in a fascist light and ignores all those elements, such as Romanticism and existentialism, which cannot. For example, Kunnas writes at great length on Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, the French novelist and German collaborator who committed suicide in 1945. He quotes from the end of Drieu’s novel, Gilles. The final scene of this novel is set during a battle in the Spanish Civil War, where the neutral but nationalist sympathizer Gilles is in the company of a Spanish nationalist garrison when it falls under attack from the Republicans. These are the final lines of the novel, quoted in full by Kunnas:

He turned on the stairwell. A wounded man on the steps moaned, “Santa Maria.”

Yes, the Mother of God, the Mother of God who made Man. God who created, who suffered in his creation, who dies and is reborn. I shall always be heretical. The gods who die and are reborn: Dionysus, Christ. Nothing is created but through blood. There must be ceaseless dying for ceaseless rebirth. The Christ of the cathedrals, the great god white and virile. A king son of a king.

He found a rifle, went to the loophole, and began to shoot, with application.

In this closing scene of the novel, according to Kunnas, “Drieu’s anti-Christian and Nietzschean religiousness becomes apparent” (p. 326). What is equally apparent to me is that Drieu is writing not only in full acceptance of the notion of sacrifice, and the sacrifice in this case may indeed be seen as willingly and consciously pro-nationalist, religiously mystical, and fascist, but he is also writing – and this Kunnas ignores – in the existentialist tradition. Gilles, it should be noted, was published in 1939, before For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) and Sartre’s Chemins de la Liberté (The Roads to Freedom, 1945), and all three novels have strikingly similar endings. They end with the hero or anti-hero finding fulfilment, even the meaning of life, in action – action which will in each case almost certainly end in death. Gilles is an existentialist novel as much as it is a fascist one, a novel in which the central figure makes sense of his life through action, the action which is a commitment to life and at the same time to death, because life and death depend on one another for meaning. To accept the necessity of death is to embrace the meaning of life. While Kunnas is not wrong in his many, albeit sometimes dogmatic, judgements (the call to Santa Maria from a dying man in the quoted passage “goes unanswered,” Kunnas assures his readers), here as elsewhere he omits all those aspects of these writers – all their activities and style – which mitigate against his thesis of their “temptation by an illusion.”

Kunnas’ work will hopefully serve as an inspiration to his readers to find or return to the primary sources and read them, or reread them, better equipped with the knowledge of the extent of the writer’s dallying or commitment to those movements whose shattering defeat in 1945 continues to cast a shadow over the politics of the entire world.

Guide to Kulchur is unique in both its structure and style. Written in Pound’s folksy demotic English that at times seems more akin to Mark Twain or Joel Chandler Harris, the book is arranged in a series of very short chapters that seem to unfold in a haphazard fashion. The book’s form only becomes manifest the longer one reads, and by the end of the book one is amazed at how Pound has managed to weave seamlessly the many strands of Western and ancient Chinese thought.

Guide to Kulchur is unique in both its structure and style. Written in Pound’s folksy demotic English that at times seems more akin to Mark Twain or Joel Chandler Harris, the book is arranged in a series of very short chapters that seem to unfold in a haphazard fashion. The book’s form only becomes manifest the longer one reads, and by the end of the book one is amazed at how Pound has managed to weave seamlessly the many strands of Western and ancient Chinese thought.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Sommaire :

Sommaire :

Dans vos deux premiers romans, Le Songe d’Empédocle et Maugis (L’Age d’Homme), vos personnages sont en quête de sacré, à rebours d’une époque anémique. Dans Le Prince d’Aquitaine, le procédé semble différent, même si le lecteur n’en sort pas indemne. Qu’en est-il ?

Dans vos deux premiers romans, Le Songe d’Empédocle et Maugis (L’Age d’Homme), vos personnages sont en quête de sacré, à rebours d’une époque anémique. Dans Le Prince d’Aquitaine, le procédé semble différent, même si le lecteur n’en sort pas indemne. Qu’en est-il ?

Faszination eines Trugbildes (The Fascination of an Illusion) by Tarmo Kunnas is an unusual book in several respects. It sets out to examine what in the subtitle to the book is described as “the European intellectual and the fascist temptation, 1919-1945.” “Here,” Kunnas explains, “the tragedy of fascism is seen through the opera glasses of the person it has captivated, and my book for its part is intended to complete a picture of the fascist movements.” (p. 9) In his Foreword, Kunnas tells us that his book deals with the relationship of more than seventy European intellectuals from fifteen nations who were “tempted” by fascism.

Faszination eines Trugbildes (The Fascination of an Illusion) by Tarmo Kunnas is an unusual book in several respects. It sets out to examine what in the subtitle to the book is described as “the European intellectual and the fascist temptation, 1919-1945.” “Here,” Kunnas explains, “the tragedy of fascism is seen through the opera glasses of the person it has captivated, and my book for its part is intended to complete a picture of the fascist movements.” (p. 9) In his Foreword, Kunnas tells us that his book deals with the relationship of more than seventy European intellectuals from fifteen nations who were “tempted” by fascism. In his Foreword, Kunnas says his objective is to examine “why fascism in the inter-war years held such attraction for the European intelligentsia and on the people of the time.” In fact, this study does not look at the attraction fascism held for people in general; it focuses exclusively on writers. The organization of the book is unusual. Instead of covering his ground with chapters devoted to specific writers or nations, Kunnas works through chapters which revolve around given themes, and then scrutinizes in each an array of writers in relation to its theme. Here are the titles of a few of the many chapters: “Exactness is not Truth,” “Mistrust of the Good in People,” “Social Darwinism,” “Puritanism,” “The Weakness of Parliamentarianism,” and “Against Faith in Progress.” For each of these, Kunnas provides the reader with an abundance of examples of how, within the perspective of the given theme, many intellectuals inclined towards fascism and a fascist solution, or towards an interpretation of the theme. This unusual approach has the advantage that it shifts focus from a biographical account to a philosophical and theoretical one so that the reader is compelled to think about the matter at hand firstly, and about the writers and thinkers drawn to it secondly; that is to say, he looks at the subject in respect of the theme itself and how fascist thinkers and fascist thought approached and evaluated each given theme. This is an original alternative to the standard presentation in critical assessments of the relation of writers to certain themes, as in potted biographies and the organization of such books into the intellectual, political, and literary career of one writer per chapter.

In his Foreword, Kunnas says his objective is to examine “why fascism in the inter-war years held such attraction for the European intelligentsia and on the people of the time.” In fact, this study does not look at the attraction fascism held for people in general; it focuses exclusively on writers. The organization of the book is unusual. Instead of covering his ground with chapters devoted to specific writers or nations, Kunnas works through chapters which revolve around given themes, and then scrutinizes in each an array of writers in relation to its theme. Here are the titles of a few of the many chapters: “Exactness is not Truth,” “Mistrust of the Good in People,” “Social Darwinism,” “Puritanism,” “The Weakness of Parliamentarianism,” and “Against Faith in Progress.” For each of these, Kunnas provides the reader with an abundance of examples of how, within the perspective of the given theme, many intellectuals inclined towards fascism and a fascist solution, or towards an interpretation of the theme. This unusual approach has the advantage that it shifts focus from a biographical account to a philosophical and theoretical one so that the reader is compelled to think about the matter at hand firstly, and about the writers and thinkers drawn to it secondly; that is to say, he looks at the subject in respect of the theme itself and how fascist thinkers and fascist thought approached and evaluated each given theme. This is an original alternative to the standard presentation in critical assessments of the relation of writers to certain themes, as in potted biographies and the organization of such books into the intellectual, political, and literary career of one writer per chapter.

Kunnas is good at highlighting contradictions and paradoxes which abound in fascist theory. How does an avowed Roman Catholic like Giovanni Papini, for example, reconcile his religious faith with the evident amoralism and ruthlessness of the militaristic foreign policy enacted by the Fascist government which he so ardently supported? By way of answer, according to Kunnas (p. 358), Papini’s early work Il tragico quotidiano (The Daily Tragic) accepts the notion that evil is a necessary part of God’s creation, and that without sin, there could be no poets, artists, or philosophers; indeed, no leaders of a people and no heroes. Vice may be the necessary condition of virtue, and evil may need to exist in order for good to do so likewise. Kunnas does not go far down the thorny and well-trodden theological path of speculation which he opens here. However, he is well aware of this and other conundra and contradictions within fascist thought, including in the writings of those intellectuals who were attracted by fascism, especially the notion that the warring poles of good and evil, war and peace, and pain and pleasure constitute the very fabric of life.

Kunnas is good at highlighting contradictions and paradoxes which abound in fascist theory. How does an avowed Roman Catholic like Giovanni Papini, for example, reconcile his religious faith with the evident amoralism and ruthlessness of the militaristic foreign policy enacted by the Fascist government which he so ardently supported? By way of answer, according to Kunnas (p. 358), Papini’s early work Il tragico quotidiano (The Daily Tragic) accepts the notion that evil is a necessary part of God’s creation, and that without sin, there could be no poets, artists, or philosophers; indeed, no leaders of a people and no heroes. Vice may be the necessary condition of virtue, and evil may need to exist in order for good to do so likewise. Kunnas does not go far down the thorny and well-trodden theological path of speculation which he opens here. However, he is well aware of this and other conundra and contradictions within fascist thought, including in the writings of those intellectuals who were attracted by fascism, especially the notion that the warring poles of good and evil, war and peace, and pain and pleasure constitute the very fabric of life.

Certains de ses romans sont passés à la postérité. Une chanson de Serge Gainsbourg mentionne L’amour monstre. Louis Pauwels doit aussi sa renommée à deux essais coécrits avec Jacques Bergier, Le matin des magiciens (1960), et sa suite moins connue, L’homme éternel (1970). Le succès du Matin des magiciens lui permit de lancer, dès 1961, la revue Planète versée dans le réalisme fantastique (l’Atlantide, les extra-terrestres dans l’histoire, le Tibet mystérieux, les expériences parapsychologiques, etc.).

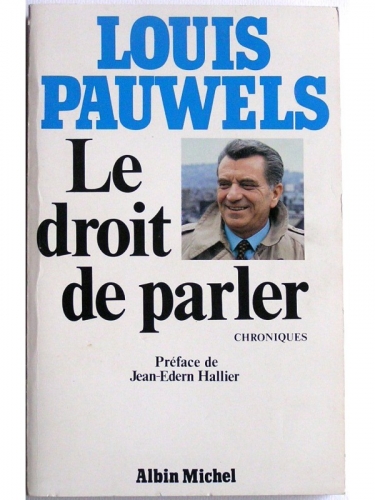

Certains de ses romans sont passés à la postérité. Une chanson de Serge Gainsbourg mentionne L’amour monstre. Louis Pauwels doit aussi sa renommée à deux essais coécrits avec Jacques Bergier, Le matin des magiciens (1960), et sa suite moins connue, L’homme éternel (1970). Le succès du Matin des magiciens lui permit de lancer, dès 1961, la revue Planète versée dans le réalisme fantastique (l’Atlantide, les extra-terrestres dans l’histoire, le Tibet mystérieux, les expériences parapsychologiques, etc.). Ce zélateur anti-écologiste du progrès technicien s’intéressait à l’Europe. Dans son maître-livre, Le droit de parler (Albin Michel, 1981), le recueil de ses premières chroniques « révolutionnaires – conservatrices » du Figaro Magazine préfacé par Jean-Édern Hallier, il revient régulièrement sur l’avenir de notre continent. « Pour que l’Europe trouve son indépendance et assure sa sécurité, elle n’a pas d’autre voie que la volonté de puissance. Nous devons avoir le dessein de devenir l’une des grandes puissances mondiales, y compris dans le domaine militaire. Nous en avons les moyens. Nous avons le nombre. […] Nous avons à nous affirmer et à nous manifester comme union des nations du vieux monde central, communauté vivante de peuples historiques concrets, forgeant concrètement leur sécurité, conscients de leur originalité, soucieux de leur rayonnement (p. 219). »

Ce zélateur anti-écologiste du progrès technicien s’intéressait à l’Europe. Dans son maître-livre, Le droit de parler (Albin Michel, 1981), le recueil de ses premières chroniques « révolutionnaires – conservatrices » du Figaro Magazine préfacé par Jean-Édern Hallier, il revient régulièrement sur l’avenir de notre continent. « Pour que l’Europe trouve son indépendance et assure sa sécurité, elle n’a pas d’autre voie que la volonté de puissance. Nous devons avoir le dessein de devenir l’une des grandes puissances mondiales, y compris dans le domaine militaire. Nous en avons les moyens. Nous avons le nombre. […] Nous avons à nous affirmer et à nous manifester comme union des nations du vieux monde central, communauté vivante de peuples historiques concrets, forgeant concrètement leur sécurité, conscients de leur originalité, soucieux de leur rayonnement (p. 219). »

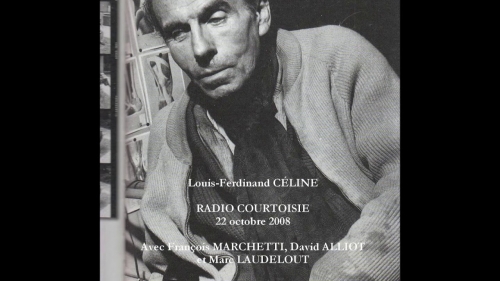

Jusqu’à ce jour, tout le monde (Céline lui-même, ses biographes, le monde judiciaire) considérait qu’en 1950 la justice française avait été bonne fille avec l’auteur des Beaux draps. Anne Simonin, directrice de recherche au CNRS, estime, elle, que le jugement fut d’une « sévérité extrême » ¹. Mais il y a mieux : on sait que l’année précédente, en novembre 1949, le commissaire du gouvernement Jean Seltensperger fut dessaisi du dossier, sa hiérarchie estimant son réquisitoire magnanime. Il se concluait, en effet, par le renvoi de Céline devant une Chambre civique (au lieu de la Cour de justice), ce qui eût entraîné une peine sensiblement moins lourde. L’historienne considère qu’il s’agit en réalité d’une « apparente complaisance », le magistrat ayant, au contraire, fait preuve d’une rare duplicité : « Imaginer renvoyer Céline en chambre civique était une façon habile de l’inciter à rentrer en France et à se produire en justice. Une fois Céline devant une chambre civique et condamné à la dégradation nationale, rien n’interdisait au commissaire du gouvernement de considérer que Céline avait aussi commis des actes de nature à nuire à la défense nationale (art. 83-4 du Code pénal). Le mandat d’arrêt, ordonné en 1945, autoriserait alors à renvoyer Céline en prison avant de le déférer en Cour de justice. Et le tour serait joué. » C’est perdre de vue que, dans son réquisitoire, Seltensperger avait requis la mainlevée du mandat d’arrêt. Et c’est surtout ne pas connaître les arcanes de cette histoire judiciaire. Coïncidence : il se trouve que le père (magistrat, lui aussi) d’un de nos célinistes les plus pointus, Éric Mazet, fut le meilleur ami de Jean Seltensperger. Au mitan des années soixante, les confidences que celui-ci fit au jeune Mazet attestent qu’il n’a jamais voulu piéger Céline, bien au contraire. Le réquisitoire modéré qu’il prononça en atteste et ce n’est pas pour rien que le dossier fut confié à un autre magistrat.

Jusqu’à ce jour, tout le monde (Céline lui-même, ses biographes, le monde judiciaire) considérait qu’en 1950 la justice française avait été bonne fille avec l’auteur des Beaux draps. Anne Simonin, directrice de recherche au CNRS, estime, elle, que le jugement fut d’une « sévérité extrême » ¹. Mais il y a mieux : on sait que l’année précédente, en novembre 1949, le commissaire du gouvernement Jean Seltensperger fut dessaisi du dossier, sa hiérarchie estimant son réquisitoire magnanime. Il se concluait, en effet, par le renvoi de Céline devant une Chambre civique (au lieu de la Cour de justice), ce qui eût entraîné une peine sensiblement moins lourde. L’historienne considère qu’il s’agit en réalité d’une « apparente complaisance », le magistrat ayant, au contraire, fait preuve d’une rare duplicité : « Imaginer renvoyer Céline en chambre civique était une façon habile de l’inciter à rentrer en France et à se produire en justice. Une fois Céline devant une chambre civique et condamné à la dégradation nationale, rien n’interdisait au commissaire du gouvernement de considérer que Céline avait aussi commis des actes de nature à nuire à la défense nationale (art. 83-4 du Code pénal). Le mandat d’arrêt, ordonné en 1945, autoriserait alors à renvoyer Céline en prison avant de le déférer en Cour de justice. Et le tour serait joué. » C’est perdre de vue que, dans son réquisitoire, Seltensperger avait requis la mainlevée du mandat d’arrêt. Et c’est surtout ne pas connaître les arcanes de cette histoire judiciaire. Coïncidence : il se trouve que le père (magistrat, lui aussi) d’un de nos célinistes les plus pointus, Éric Mazet, fut le meilleur ami de Jean Seltensperger. Au mitan des années soixante, les confidences que celui-ci fit au jeune Mazet attestent qu’il n’a jamais voulu piéger Céline, bien au contraire. Le réquisitoire modéré qu’il prononça en atteste et ce n’est pas pour rien que le dossier fut confié à un autre magistrat.

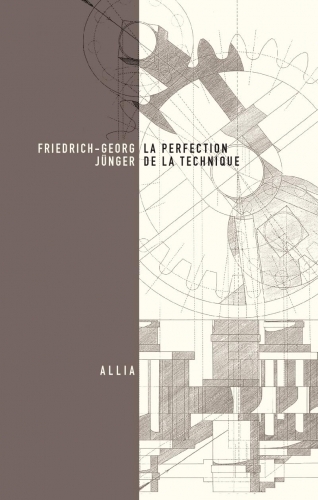

Les éditions Allia publient cette semaine un essai de Friedrich-Georg Jünger intitulé La perfection de la technique. Frère d'Ernst Jünger. Auteur de très nombreux ouvrages, Friedrich-Georg Jünger a suivi une trajectoire politique et intellectuelle parallèle à celle de son frère Ernst et a tout au long de sa vie noué un dialogue fécond avec ce dernier. Parmi ses oeuvres ont été traduits en France un texte écrit avec son frère, datant de sa période conservatrice révolutionnaire,

Les éditions Allia publient cette semaine un essai de Friedrich-Georg Jünger intitulé La perfection de la technique. Frère d'Ernst Jünger. Auteur de très nombreux ouvrages, Friedrich-Georg Jünger a suivi une trajectoire politique et intellectuelle parallèle à celle de son frère Ernst et a tout au long de sa vie noué un dialogue fécond avec ce dernier. Parmi ses oeuvres ont été traduits en France un texte écrit avec son frère, datant de sa période conservatrice révolutionnaire,

Mr. Wilson begins his “inquiry into the nature of the sickness of mankind in the twentieth century” at the effective point of the writers who have most influence in the present intellectual world. They are mostly good writers; they are not among the writers catering for those intellectuals who have every qualification except an intellect. They are good, some are very good: but at the end of it all what emerges? One of the best of these writers predicted that at the end of it all comes “the Russian man” described by Mr. Wilson as “a creature of nightmare who is no longer the homo sapiens, but an existentialist monster who rejects all thought”, As Hesse, the prophet of this coming, put it: “he is primeval matter, monstrous soul stuff. He cannot live in this form; he can only pass on”. The words “he can only pass on” seem the essence of the matter; this thinking is a chaos between two orders. At some point, if we are ever to regain sanity, we must regard again the first order before we can hope to win the second. It was a long way from Hellas to “the Russian man”; it may not be so far from the turmoil of these birth pangs to fresh creation. It is indeed well worth taking a look at the intellectual situation; where Europeans were, and where we are.

Mr. Wilson begins his “inquiry into the nature of the sickness of mankind in the twentieth century” at the effective point of the writers who have most influence in the present intellectual world. They are mostly good writers; they are not among the writers catering for those intellectuals who have every qualification except an intellect. They are good, some are very good: but at the end of it all what emerges? One of the best of these writers predicted that at the end of it all comes “the Russian man” described by Mr. Wilson as “a creature of nightmare who is no longer the homo sapiens, but an existentialist monster who rejects all thought”, As Hesse, the prophet of this coming, put it: “he is primeval matter, monstrous soul stuff. He cannot live in this form; he can only pass on”. The words “he can only pass on” seem the essence of the matter; this thinking is a chaos between two orders. At some point, if we are ever to regain sanity, we must regard again the first order before we can hope to win the second. It was a long way from Hellas to “the Russian man”; it may not be so far from the turmoil of these birth pangs to fresh creation. It is indeed well worth taking a look at the intellectual situation; where Europeans were, and where we are. This union of mind and will, of intellect and emotion in the classic Greek, this essential harmony of man and nature, this at-oneness of the human with the eternal spirit evoke the contrast of the living and the dying when set against the prevailing tendencies of modern literature. For, as Mr. Wilson puts it very acutely: when “misery will never end” is combined with “nothing is worth doing”, “the result is a kind of spiritual syphillis that can hardly stop short of death or insanity”. Yet such writers are not all “pre-occupied with sex, crime and disease”, treating of heroes who live in one room because, apparently, they dare not enter the world outside, and derive their little satisfaction of the universe from looking through a hole in the wall at a woman undressing in the next room. They are not all concerned like Dostoievsky’s “beetle man” with life “under the floor boards” (a study which should put none of us off reading him as far as the philosophy of the Grand Inquisitor and a certain very interesting conversation with the devil in the Brothers Karamazof, which Mr. Wilson rightly places very high in the world’s literature). Many of these writers of pessimism, of destruction and death have a considerable sense of beauty. Hesse’s remarkable Steppenwolf found his “life had become weariness” and he “wandered in a maze of unhappiness that led to the renunciation of nothingness”; but then “for months together my heart stood still between delight and stark sorrow to find how rich was the gallery of my life, and how thronged was the soul of wretched Steppenwolf with high eternal stars and constellations . . . this life of mine was noble. It came of high descent, and turned, not on trifles, but on the stars.” Mr. Wilson well comments that “stripped of its overblown language,” “this experience can be called the ultimately valid core of romanticism — a type of religious affirmation”. And in such writing we can still see a reflection of the romantic movement of the northern gothic world which Goethe strove to unite with the sunlit classic movement in the great synthesis of his Helena. But it ends generally in this literature with a retreat from life, a monastic detachment or suicide rather than advance into such a wider life fulfilment. The essence is that these people feel themselves inadequate to life; they feel even that to live at all is instantly to destroy whatever flickering light of beauty they hold within them. For instance De Lisle Adam’s hero Axel had a lady friend who shot at him “with two pistols at a distance of five yards, but missed him both times.” Yet even after this dramatic and perfect illustration of the modern sex relationship, they could not face life : “we have destroyed in our strange hearts the love of life . . . to live would only be a sacrilege against ourselves . . .” “They drink the goblet of poison together and die in ecstasy.” All of which is a pity for promising people, but, in any case, is preferable to the “beetle man”, “under the floor boards”, wall-peepers, et hoc genus omne, of burrowing fugitives; “Samson you cannot be too quick”, is a natural first reaction to them. Yet Mr. Wilson teaches us well not to laugh too easily, or too lightly to dismiss them; it is a serious matter. This is serious if it is the death of a civilisation; it is still more serious if it is not death but the pangs of a new birth. And, in any case, even the worst of them possess in some way the essential sensitivity which the philistine lacks. So we will not laugh at even the extremes of this system, or rather way of thinking; something may come out of it all, because at least they feel. But Mr. Wilson in turn should not smile too easily at the last “period of intense and healthy optimism that did not mind hard work and pedestrian logic.” He seems to regard the nineteenth century as a “childish world” which presaged “endless changes in human life” so that “man would go forward indefinitely on ‘stepping stones of his dead self’ to higher things.” He thinks that before we “condemn it for short-sightedness”, ” we survivors of two world wars and the atomic bomb” (at this point surely he outdoes the Victorians in easy optimism, for it is far from over yet) “would do well to remember that we are in the position of adults condemning children”. Why? — is optimism necessarily childish and pessimism necessarily adult? Sometimes this paralysed pessimism seems more like the condition of a shell-shocked child. Health can be the state of an adult and disease the condition of a child. Of course, if serious Victorians really believed in “the establishment of Utopia before the end of the century”, they were childish; reformist thinking of that degree is always childish in comparison with organic thinking. But there are explanations of the difference between the nineteenth and the twentieth century attitude, other than this distinction between childhood and manhood. Spengler said somewhere that the nineteenth century stood in relation to the twentieth century as the Athens of Pericles stood in relation to the Rome of Caesar. In his thesis this is not a distinction between youth and age — a young society does not reach senescence in so short a period — but the difference between an epoch which is dedicated to thought and an epoch which has temporarily discarded thought in favour of action, in the almost rhythmic alternation between the two states which his method of history observes. It may be that in this most decisive of all great periods of action the intellectual is really not thinking at all; he is just despairing. When he wakes up from his bad dream he may find a world created by action in which he can live, and can even think. Mr. Wilson will not quarrel with the able summary of his researches printed on the cover of his book : “it is the will that matters.” And he would therefore scarcely dispute the view just expressed; perhaps the paradox of Mr. Wilson in this period is that he is thinking. That thought might lead him through and far beyond the healthy “cowboy rodeo” of the Victorian philosophers in their sweating sunshine, on (not back) to the glittering light and shade of the Hellenic world — das Land der Griechen mit der Seele suchen — and even beyond it to the radiance of the zweite Hellas. Mr. Wilson does not seem yet to be fully seized of Hellenism, and seems still less aware of the more conscious way of European thinking that passes beyond Hellas to a clearer account of world purpose. He has evidently read a good deal of Goethe with whom such modern thinking effectively begins, and he is the first of the new generation to feel that admiration for Shaw which was bound to develop when thought returned. But he does not seem to be aware of any slowly emerging system of European thinking which has journeyed from Heraclitus to Goethe and on to Shaw, Ibsen and other modems, until with the aid of modern science and the new interpretation of history it begins to attain consciousness.

This union of mind and will, of intellect and emotion in the classic Greek, this essential harmony of man and nature, this at-oneness of the human with the eternal spirit evoke the contrast of the living and the dying when set against the prevailing tendencies of modern literature. For, as Mr. Wilson puts it very acutely: when “misery will never end” is combined with “nothing is worth doing”, “the result is a kind of spiritual syphillis that can hardly stop short of death or insanity”. Yet such writers are not all “pre-occupied with sex, crime and disease”, treating of heroes who live in one room because, apparently, they dare not enter the world outside, and derive their little satisfaction of the universe from looking through a hole in the wall at a woman undressing in the next room. They are not all concerned like Dostoievsky’s “beetle man” with life “under the floor boards” (a study which should put none of us off reading him as far as the philosophy of the Grand Inquisitor and a certain very interesting conversation with the devil in the Brothers Karamazof, which Mr. Wilson rightly places very high in the world’s literature). Many of these writers of pessimism, of destruction and death have a considerable sense of beauty. Hesse’s remarkable Steppenwolf found his “life had become weariness” and he “wandered in a maze of unhappiness that led to the renunciation of nothingness”; but then “for months together my heart stood still between delight and stark sorrow to find how rich was the gallery of my life, and how thronged was the soul of wretched Steppenwolf with high eternal stars and constellations . . . this life of mine was noble. It came of high descent, and turned, not on trifles, but on the stars.” Mr. Wilson well comments that “stripped of its overblown language,” “this experience can be called the ultimately valid core of romanticism — a type of religious affirmation”. And in such writing we can still see a reflection of the romantic movement of the northern gothic world which Goethe strove to unite with the sunlit classic movement in the great synthesis of his Helena. But it ends generally in this literature with a retreat from life, a monastic detachment or suicide rather than advance into such a wider life fulfilment. The essence is that these people feel themselves inadequate to life; they feel even that to live at all is instantly to destroy whatever flickering light of beauty they hold within them. For instance De Lisle Adam’s hero Axel had a lady friend who shot at him “with two pistols at a distance of five yards, but missed him both times.” Yet even after this dramatic and perfect illustration of the modern sex relationship, they could not face life : “we have destroyed in our strange hearts the love of life . . . to live would only be a sacrilege against ourselves . . .” “They drink the goblet of poison together and die in ecstasy.” All of which is a pity for promising people, but, in any case, is preferable to the “beetle man”, “under the floor boards”, wall-peepers, et hoc genus omne, of burrowing fugitives; “Samson you cannot be too quick”, is a natural first reaction to them. Yet Mr. Wilson teaches us well not to laugh too easily, or too lightly to dismiss them; it is a serious matter. This is serious if it is the death of a civilisation; it is still more serious if it is not death but the pangs of a new birth. And, in any case, even the worst of them possess in some way the essential sensitivity which the philistine lacks. So we will not laugh at even the extremes of this system, or rather way of thinking; something may come out of it all, because at least they feel. But Mr. Wilson in turn should not smile too easily at the last “period of intense and healthy optimism that did not mind hard work and pedestrian logic.” He seems to regard the nineteenth century as a “childish world” which presaged “endless changes in human life” so that “man would go forward indefinitely on ‘stepping stones of his dead self’ to higher things.” He thinks that before we “condemn it for short-sightedness”, ” we survivors of two world wars and the atomic bomb” (at this point surely he outdoes the Victorians in easy optimism, for it is far from over yet) “would do well to remember that we are in the position of adults condemning children”. Why? — is optimism necessarily childish and pessimism necessarily adult? Sometimes this paralysed pessimism seems more like the condition of a shell-shocked child. Health can be the state of an adult and disease the condition of a child. Of course, if serious Victorians really believed in “the establishment of Utopia before the end of the century”, they were childish; reformist thinking of that degree is always childish in comparison with organic thinking. But there are explanations of the difference between the nineteenth and the twentieth century attitude, other than this distinction between childhood and manhood. Spengler said somewhere that the nineteenth century stood in relation to the twentieth century as the Athens of Pericles stood in relation to the Rome of Caesar. In his thesis this is not a distinction between youth and age — a young society does not reach senescence in so short a period — but the difference between an epoch which is dedicated to thought and an epoch which has temporarily discarded thought in favour of action, in the almost rhythmic alternation between the two states which his method of history observes. It may be that in this most decisive of all great periods of action the intellectual is really not thinking at all; he is just despairing. When he wakes up from his bad dream he may find a world created by action in which he can live, and can even think. Mr. Wilson will not quarrel with the able summary of his researches printed on the cover of his book : “it is the will that matters.” And he would therefore scarcely dispute the view just expressed; perhaps the paradox of Mr. Wilson in this period is that he is thinking. That thought might lead him through and far beyond the healthy “cowboy rodeo” of the Victorian philosophers in their sweating sunshine, on (not back) to the glittering light and shade of the Hellenic world — das Land der Griechen mit der Seele suchen — and even beyond it to the radiance of the zweite Hellas. Mr. Wilson does not seem yet to be fully seized of Hellenism, and seems still less aware of the more conscious way of European thinking that passes beyond Hellas to a clearer account of world purpose. He has evidently read a good deal of Goethe with whom such modern thinking effectively begins, and he is the first of the new generation to feel that admiration for Shaw which was bound to develop when thought returned. But he does not seem to be aware of any slowly emerging system of European thinking which has journeyed from Heraclitus to Goethe and on to Shaw, Ibsen and other modems, until with the aid of modern science and the new interpretation of history it begins to attain consciousness. He is acute at one point in observing the contrasts between the life joy of the Greeks and the moments when their art is “full of the consciousness of death and its inevitability”. But he still apparently regards them as “healthy, once born, optimists,” not far removed from the modern bourgeois who also realises that life is precarious. He apparently thinks they did not share with the Outsider the knowledge that an “exceptional sense of life’s precariousness” can be “a hopeful means to increase his toughness”. The Greeks, of course, had not the advantage of reading Mr. Toynbee’s Study of History, which does not appear on a reasonably careful reading to be mentioned in Mr. Wilson’s book.

He is acute at one point in observing the contrasts between the life joy of the Greeks and the moments when their art is “full of the consciousness of death and its inevitability”. But he still apparently regards them as “healthy, once born, optimists,” not far removed from the modern bourgeois who also realises that life is precarious. He apparently thinks they did not share with the Outsider the knowledge that an “exceptional sense of life’s precariousness” can be “a hopeful means to increase his toughness”. The Greeks, of course, had not the advantage of reading Mr. Toynbee’s Study of History, which does not appear on a reasonably careful reading to be mentioned in Mr. Wilson’s book. But Mr. Wilson moves far beyond Sartre in regarding the thinkers of an earlier period; notably Blake. At this point he recovers direction. The reader will find pages 225 to 250 among the most important of this book, but he must read the whole work for himself; this review is a commentary and an addendum, not a précis for the idle, nor a primer for those who find anything serious too difficult. The author advances a long way when he considers Blake’s “skeleton key” to a solution for those who “mistake their own stagnation for the world’s”. Here we reach realisation that the “crises of’living demand the active co-operation of intellect, emotions, body on equal terms”; contact is made here with Goethe’s Ganzheit, although it is not mentioned. “Energy is eternal delight” takes us a long way clear o the damp caverns of neo-existentialism and

But Mr. Wilson moves far beyond Sartre in regarding the thinkers of an earlier period; notably Blake. At this point he recovers direction. The reader will find pages 225 to 250 among the most important of this book, but he must read the whole work for himself; this review is a commentary and an addendum, not a précis for the idle, nor a primer for those who find anything serious too difficult. The author advances a long way when he considers Blake’s “skeleton key” to a solution for those who “mistake their own stagnation for the world’s”. Here we reach realisation that the “crises of’living demand the active co-operation of intellect, emotions, body on equal terms”; contact is made here with Goethe’s Ganzheit, although it is not mentioned. “Energy is eternal delight” takes us a long way clear o the damp caverns of neo-existentialism and No men ever had a deeper sense of the human tragedy than the Greeks; none ever faced it with such brilliant bravery or understood so well not only the art of grasping the fleeting, ecstatic moment, but of turning even despair to the enhancement of beauty. Living was yet great; they understood dennoch preisen; they did not “leave living to their servants”. Mr. Wilson in quoting Aristotle in the same sense as the above lines of Sophocles — “not to be born is the best thing, and death is better than life” — holds that “this view” lies at one extreme of religion, and that “the other extreme is vitalism”. He does not seem at this point fully to understand that the extremes in the Hellenic nature can be not contradictory but complementary, or interacting. The polarity of Greek thought was closely observed and finely interpreted by Nietzsche in diverse ways. But it was left to Goethe to express the more conscious thought beyond polarity in his Faust: the Prologue in Heaven:

No men ever had a deeper sense of the human tragedy than the Greeks; none ever faced it with such brilliant bravery or understood so well not only the art of grasping the fleeting, ecstatic moment, but of turning even despair to the enhancement of beauty. Living was yet great; they understood dennoch preisen; they did not “leave living to their servants”. Mr. Wilson in quoting Aristotle in the same sense as the above lines of Sophocles — “not to be born is the best thing, and death is better than life” — holds that “this view” lies at one extreme of religion, and that “the other extreme is vitalism”. He does not seem at this point fully to understand that the extremes in the Hellenic nature can be not contradictory but complementary, or interacting. The polarity of Greek thought was closely observed and finely interpreted by Nietzsche in diverse ways. But it was left to Goethe to express the more conscious thought beyond polarity in his Faust: the Prologue in Heaven: May we end with a few questions based on that doctrine of higher forms which has found some expression in this Journal and in previous writings? Is it not now possible to observe with reason and as something approaching a clearly defined whole, what has hitherto only been revealed in fitful glimpses to the visionary? What are the means of observation available to those who are not blessed with the revelation of vision? Are they not the thoughts of great minds which have observed the working of the divine in nature and the researches of modern science which appear largely to confirm them?