Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1999

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1999

"Antaios", fer de lance de la reconquête païenne

Anne MUNSBACH

«... les légions de nos vieilles légendes accourues à l'appel de leur dernier empereur païen».

Jean Raspail, Septentrion.

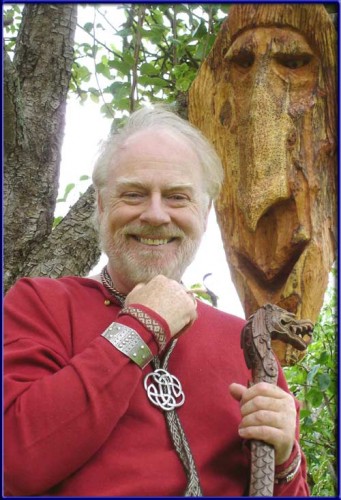

Infortunés Dieux! Les dévots de la Bonne Parole leur jettent l'anathème, les prophètes leur lancent blâmes et malédictions, les Grands Prêtres de l'Exégèse manifestent intransigeance et haine, des rires moqueurs fusent. Il y a donc fort à faire pour soulever la chape de clichés qui recouvre depuis des lustres les lumières du Paganisme. Pourtant, il existe une revue du nom d'Antaios qui résiste avec autant de superbe que d'ironie. Elle s'entend à éclairer la véritable signification du Paganisme, à le dépouiller de son aura de scandale et à ainsi le réhabiliter. Sous le regard lucide de son directeur, l'helléniste Christopher Gérard, se révèlent alors les prophètes pour ce qu'ils sont: des cabotins, renvoyés à la niche dans un grand éclat de rire, écho souverain du fameux rire des Dieux chanté par Homère.

Antaios, Revue d'Etudes Polythéistes

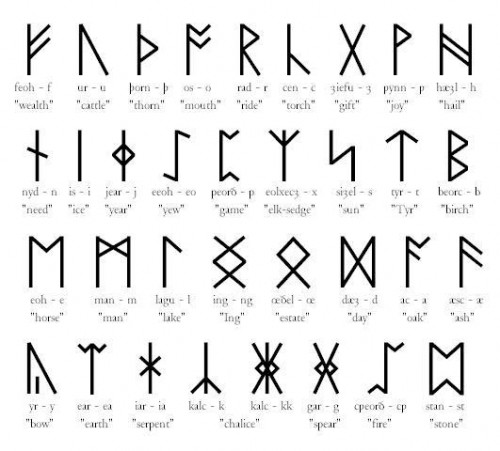

C'est à l'occasion du 1600ème anniversaire de l'interdiction par l'Empereur Théodose de tous les cultes païens (8 novembre 392) qu'a été fondée Antaios, Revue d'Etudes Polythéistes. Pourquoi ce nom? Antaios est un géant de la mythologie grecque. Fils de Gaïa (la Terre) et de Poseidon (l'Océan), il vivait dans le désert de Libye et terrassait tout voyageur traversant son territoire. Seul Héraclès en vint à bout. Il avait en effet découvert le secret de la vigueur miraculeuse du géant: tant qu'il touchait la Terre, l'élément primordial dont il était issu, il était invulnérable. Pour l'anéantir, il suffisait donc de l'en séparer. «La symbolique de ce mythe est claire: c'est en gardant le contact avec notre sol que nous resterons nous-mêmes, capables de relever tous les défis, d'affronter toutes les tempêtes. En revanche, si nous nous coupons de nos origines, si nous oublions nos traditions, tôt ou tard nous serons balayés, tels des fétus de paille, privés de force et de volonté... Ce sol protecteur, ce sol vivifiant, c'est le Paganisme immémorial, c'est l'antique fidélité à nos Dieux. Non point des Dieux personnels et miséricordieux, jaloux et intolérants, image ô combien dégradée et infantilisante du Sacré mais des principes intemporels, des modèles éternels qui doivent nous permettent de nous projeter dans un avenir grandiose, digne de nos aieux». Voilà présenté avec une concision lumineuse le manifeste d'Antaios.

La reconnaissance du patriarche de Wilflingen

Antaios est aussi le nom de la revue fondée en 1959 par Ernst Jünger et Mircea Eliade. Les deux hommes s'y sont interrogés sur la nature du Sacré et ont montré que, par la connaissance des mythes, il était possible «de rééquilibrer la conscience humaine, de créer un nouvel humanisme, une anthropologie où microcosme et macrocosme correspondraient à nouveau. Ils témoignaient ainsi de cette certitude qu'un redressement spirituel était encore envisageable dans les années soixante, et qu'il pouvait mettre fin à la décadence ou aux affres d'un temps d'interrègne» (1). Dans le dernier volume de ses mémoires, Ernst Jünger saluait l'heureuse initiative de Christopher Gérard de perpétuer Antaios et l'encourageait vivement à poursuivre (2). Il soulignait, dans plusieurs lettres adressées à la revue, qu'il en appréciait l'esprit. Précieuse reconnaissance d'un écrivain qui, par-delà la mêlée, a toujours su rester fidèle à lui-même! Fort de cette filiation, son directeur a rapidement imprimé sa marque à Antaios. Cette publication, dont la réflexion rigoureuse se nourrit des disciplines les plus pointues, est en effet plus qu'une simple revue érudite. Elle a su sortir du cercle des livres et des discussions désincarnées pour se forger une méthode personnelle à mille lieues de tout académisme. Cette méthode est tout à la fois savoir “tactile” capable d'écouter la pierre et d'extraire la légende du marbre, érudition sauvage glanant ses repères hors des boulevards des idées convenues, regard sensible à la poésie du monde, surtout connaissance vivante née de l'expérience “sui generis”. Cela a déjà valu aux lecteurs d'Antaios cinq années de lectures souvent intenses, en tout cas jamais insignifiantes.

Le Paganisme, religion cosmique

Lorsqu'au IVe siècle le Christianisme accéda au statut de religion reconnue et protégée par l'Etat romain, l'évangélisation ne se développa réellement que dans les centres urbains. Les campagnes quant à elles restèrent imperméables à l'influence chrétienne. Antaios revendique hautement le titre de “païen” que les Chrétiens donnèrent alors, par dérision, à leurs adversaires. Ce furent en effet les gens de la campagne, les pagani (les ruraux), qui les derniers restèrent fidèles aux enseignements du Polythéisme: eux seuls saisissaient encore le sens de l'univers. Vivant en symbiose avec la nature, les sociétés rurales avaient en effet une perception aiguë des cycles cosmiques et des éléments naturels qui imposent leur empreinte à la terre. Cette perception de ce qu'elles nommaient le Divin éclatait sans cesse à leurs yeux. Rien ne leur était dès lors plus étranger que l'idée d'un Dieu lointain, et plus encore d'un Dieu caché. Pour établir comme interlocuteurs et alliés ces forces naturelles, les sociétés rurales apprirent à les apprivoiser et à les respecter. C'est pourquoi fut mise en œuvre toute une structure du Sacré. La personnification des forces naturelles sous forme d'entités divines était un élément essentiel de cette structure. Les rites, qu'ils fussent de reconnaissance, de protection, de coercition ou encore de conciliation, permettaient quant à eux d'établir tout un réseau de relations avec le roc, la foudre, l'arbre ou la rivière. De nos jours, il n'est plus question «de croire dans les esprits ou les différentes entités de la nature. En revanche, le sens du fonctionnement normal du cycle naturel, cosmique, est essentiel pour replacer l'homme dans l'univers» (3). Or, les forêts sont saccagées, et Gaïa se transforme en désert. La déperdition du tellurique au profit de l'auto-extension sans frein du technologique explique l'impuissance accrue de l'homme à faire surgir des significations d'une nature intemporelle L'homme ne parvient donc plus à percevoir le lien l'unissant au Cosmos, il s'est coupé de ses Dieux. Il se met alors à confectionner des abstractions ou à imaginer des Dieux hors du monde.

Le Sacré

«Les seules expériences du Sacré seraient stériles si l'homme ne possédait des structures intellectuelles et imaginaires pour les recueillir. Celles-ci lui permettent, en premier lieu, la perception, la préhension de la manifestation du Sacré. En deuxième lieu, sa com-préhension par le fait même de donner un sens à ses expériences et, en troisième lieu, sa transmission, sa communication par les structures de la tradition, par le rite et le mythe» (4). Structurer le Sacré passe donc par sa mise en forme au travers de symboles, de mythes et de rites, notions qu'Antaios décrypte à diverses reprises (5) et qu'il est essentiel d'évoquer ici avant de poursuivre plus loin. «L'expérience du Sacré étant, par essence, indicible et non rationnelle, elle ne saurait faire l'objet d'aucune description concrète et nécessite dès lors le recours à la symbolique» (6), sous forme d'images —ce sont les symboles—, et sous forme de récits —ce sont les mythes. D'où notre besoin d'artistes et de poètes, dont Antaios offre un récital éblouissant (7): ils se font porte-parole des Dieux en les rendant sensibles. Loin d'être des distractions stériles pour intellectuels blasés, symboles et mythes suggèrent le Sacré par effet rétroactif: ils sont donc sources inépuisables de connaissances et de recherches de significations. Une troisième mise en forme du Sacré est le rite. Le rite, constitué de gestes ou d'actes ordinaires sublimés et codifiés, «a pour fonction essentielle d'amener les hommes et les Dieux à communier, à fonder l'Ordre du monde dans une présence commune, génératrice de l'ordre social» (8). Structurer le Sacré permet ainsi de penser et d'ordonner l'univers et, au-delà, de vivre en harmonie avec lui, de s'y fondre.

Un lieu, un peuple, des Dieux

Face à la pluralité de paysages, de climats et de végétations qui existent de par le monde, on comprend aisément qu'en fonction de chaque lieu s'instaurent des modalités de vie différentes et donc, pour chaque peuple et, a fortiori, pour chaque culture, des manières différentes d'appréhender le Divin, de structurer le Sacré et ainsi, de penser et d'ordonner l'univers. Sont dès lors générés des Dieux, symboles de l'histoire conjointe d'un lieu et d'un groupe humain qu'il soit famille, genos, phratrie, dème ou cité. Ces Dieux, ces genii loci intensifient le sentiment de communion sociale et par là-même s'enracinent dans une culture. Voilà qui explique l'attachement irréductible du Païen à sa terre et son amour pour une communauté historique. Le Paganisme est donc une religion de lieu et de corps, inscrite dans la mémoire collective. Antaios souligne d'ailleurs qu'il n'y a pas qu'un Paganisme, mais des Paganismes: chacun correspondant à une société donnée —ou à une personne donnée— et à un moment précis, répondant à des interrogations sans cesse mobiles et à des conditions de vie toujours changeantes. Et Christopher Gérard d'expliquer que la vision qu'il expose n'est qu' «une approche du Paganisme, en l'occurrence celle qui est la mienne, hic et nunc. Je n'entends donc nullement me poser en représentant de la totalité du courant néo-paien contemporain. Je suis d'ailleurs convaincu qu'il existe autant d'approches paiennes que de Paiens. Et n'est-ce pas dans la nature des choses, puisque le propre des divers Paganismes, anciens ou nouveaux, est précisément cette exaltation de l'infinie pluralité de l'être» (9).

Terre d'Europe

La vision officielle de l'Europe —cette fameuse U.E.— est erronée et fatale car elle axe toute sa démarche sur la puissance économique, oubliant volontairement ses valeurs ancestrales. Cette vision ne peut dès lors qu'aboutir à la création d'une superstructure sans racines populaires, un monstre froid condamné à disparaître. Elle nie en effet l'essence de l'Europe: cet équilibre entre des peuples et des cultures qui, comme les cités de l'antique Grèce, communient dans une sphère culturelle commune sans cependant désirer, ni être capables de se fondre dans le même moule. Dans ce cadre qui ne reconnaît plus d'autre fin que le profit, d'étranges cultes et de terribles perversions apparaissent. C'est le temps des faux Dieux: «de nouvelles Divinités féroces et implacables ont surgi sous les traits du machinisme envahissant, de l'efficacité et de la rentabilité, des contrats sociaux, de l'esprit des lois, du culte de l'Etat-Providence, du décalogue des Droits de l'homme, des slogans du marketing électoral. L'homme, écrasé, domestiqué, asservi comme jamais il ne l'a été, n'a plus aucun accès au Sacré pour consoler son coeur et éclairer son esprit, il a seulement le culte du vulgaire matérialisme où tout se juge à l'aune du profit et d'un bien-être illusoire, sans aucune spiritualité» (10). Face à ce crépuscule matérialiste, les Dieux peuvent nous aider. Non qu'ils nous offrent une panacée, un nectar qui soigne tous nos maux, mais ils représentent notre héritage le plus ancien et le plus riche. Ils sont le substrat sur lequel peuvent croître les solutions qui conviennent aux défis actuels et futurs. Il faut donc retrouver ces Dieux, ceux de la forêt celtique comme les porteurs de lumière méditerranéens. Il faut retrouver nos mythes, ces récits fondateurs du mental européen: c'est dans leur esprit que se trouve le souffle de notre avenir. Pour défendre ces héritages les plus lointains, Christopher Gérard et son équipe travaillent sans relâche. C'est leur façon de demeurer fidèles à nos Dieux et de témoigner de leur présence. C'est leur façon de nous rappeler que toute Renaissance est un appel à la plus ancienne mémoire, qui est païenne: l'histoire de la civilisation européenne le montre. Pour nous tenir en éveil, Antaios est d'ailleurs composée “à la dure”, avec des phrases concises, sculptées d'images flamboyantes. Pas d'hésitations, ni de langueurs. Pas de mauvaises graisses, mais des protéines pures. Et un français de qualité!

Une vision impériale pour l'Europe de demain

La vision européenne d'Antaios table sur une société “polythée” qui, en ce sens, est «celle qui permet l'existence de communautés indépendantes, autonomes, voire rivales, mais dont les rapports sont strictement codifiés afin d'éviter que les inévitables conflits dégénèrent en guerre. Pour citer le cas yougoslave, pareille tragédie pourrait être évitée au sein d'une structure de type “polythée”, voire impériale, à savoir un ensemble hétérogène de peuples relativement homogènes, où les droits des minorités seraient garantis. Sur le plan politique, le Polythéisme prend en compte, avec beaucoup de réalisme, ce désir inné d'autarcie et de complétude» (11). La meilleure forme politique pour notre continent serait donc celle d'un bloc aux dimensions impériales, bâti sur des structures fédérales, où identités et spécificités, véritables ciments cohésifs des sociétés, seraient préservées. Se constituerait ainsi une pluralité de patries charnelles sous l'égide d'une instance impériale dont les rôles seraient ceux d'arbitre souverain et de protecteur, fonctions profondément ancrées dans la conception européenne du Politique. Seule cette structure peut être garante de l'indépendance et de la puissance de l'Europe, structure «dont on retrouve les prémices chez l'Empereur Julien (331-363), dans sa théorie des Dieux ethnarques (nationaux), où il fonde un type de cosmopolitisme impérial» (12): l'organisation politico-religieuse de la société s'y fait le reflet de l'organisation du monde divin. Beau témoignage d'une société fondée en harmonie avec le Cosmos!

L'axe eurasiatique

Dans chacun de ses numéros, Antaios propose des dossiers thématiques solidement charpentés. Ont ainsi été présentés aux lecteurs deux dossiers sur l'“Hindutva” (13). «Ce terme sanskrit désigne l'Hindouité, c'est-à-dire l'identité de l'Inde essentielle —l'Inde védique— qui a survécu, tout en évoluant, à plus de quatre millénaires de turbulences: invasions musulmanes, colonisation anglaise —comme l'Irlande—, agissements de diverses missions chrétiennes et enfin assauts d'une modernité particulièrement destructrice... Récemment, le concept d'“Hindutva”, qui ne se réduit pas au seul Hindouisme, a été utilisé par V. D. Savarkar, l'une des grandes figures du mouvement national indien, pour inciter les Hindous à recourir à leur héritage védique, celui de l'Inde antérieure, la plus grande Inde» (14). Il s'agit d'une tradition proche de la nôtre car issue du même tronc indo-européen, tout en en étant séparée par l'influence de la culture autochtone dravidienne et des millénaires d'histoire. Il n'empêche que l'Hindouisme a su conserver l'antique sagesse de nos ancêtres indo-européens, de mieux en mieux connus aujourd'hui «malgré le discrédit causé par des distorsions opérées au XIXème siècle pour justifier l'expansionnisme pangermanique, malgré aussi de maladroites tentatives de nier l'antique patrimoine ancestral qui est le nôtre, ou encore de le vider de son sens au nom d'une idéologie spirituellement correcte (15)... Les Védas, autant qu'Homère ou les Eddas, constituent nos textes sacrés car ils renvoient tous à une religiosité primordiale, la religion cosmique de la tribu indo-européenne encore indivise, notre tradition hyperboréenne. En Inde, cet héritage n'a pas été saccagé, falsifié et nié comme en Europe ou, en tout cas, la résistance a été plus vive. L'acculturation causée par la christianisation toute superficielle de notre continent, datant surtout de la Contre-Réforme (et de l'avènement de l'Etat moderne) n'a pas eu lieu aux Indes. La tradition paienne y est ininterrompue et le lien toujours possible avec les Brahmanes, les frères de nos Druides. Zeus et Indra, Shiva et Dionysos peuvent, et doivent, se retrouver pour assurer à l'Europe le dépassement du nihilisme qui la ronge. Le recours à cette source pure n'est en rien l'imitation imbécile d'une civilisation à bien des égards fort lointaine. Nous n'avons pas à nous convertir servilement, comme tant d'Occidentaux déboussolés, à un Hindouisme de pacotille; nous n'avons pas à nous réfugier dans les bras de gourous, par un phénomène de régression infantile ou de néo-primitivisme» (16), piège qu'avait brillamment évité Alain Daniélou dont l'étude de l'œuvre constitue la ligne directrice des dossiers “Hindutva”. Indianiste, sanskritiste, musicologue, Alain Daniélou «reste l'un des rares Européens à avoir été accueilli non pas dans un ashram, mais dans la société traditionnelle de l'Inde, et ce, pendant plus de quinze ans... Son œuvre et sa vie constituent un pont sans doute unique entre deux civilisations ou plutôt deux conceptions de la place et du rôle des sociétés humaines sur la planète: l'une, régissant la dernière civilisation traditionnelle vivante, a cherché à établir un équilibre non seulement entre les groupes humains, mais entre ceux-ci et le monde naturel, considéré comme la patrie des Dieux. C'est la civilisation polythéiste, celle du temps cyclique et des mythologies. L'autre conception, infiniment plus récente, est celle du temps linéaire, du Monothéisme. Elle prône l'instabilité économique, politique et sociale, l'anéantissement des différences et le rejet des traditions, dans un but de domination de la nature et de Progrès» (17). Face à cette morne réalité, «l'Inde nous appelle à retrouver le regard de l'homme archaïque pour mieux affronter les défis du prochain millénaire, qui sera à la fois postchrétien et postrationaliste. Tout le monde connaît, sans l'avoir vraiment lue, la phrase souvent tronquée de Malraux: “La tâche du prochain siècle, en face de la plus terrible menace qu'ait connue l'humanité, va être d'y réintégrer les Dieux”. Or l'Inde n'a jamais rompu le contrat avec ses Dieux, cette “Pax Deorum”, qui est le fondement de toute société traditionnelle. L'“Hindutva” possède aussi une vocation universelle, et non pas universaliste car il ne s'agit pas de réductionnisme mais bien de la persistance du vieux singularisme paien: l'acceptation des différences et des saines alternances, fondatrices d'une civilisation qui honore et respecte le divers autrefois chanté par Segalen» (18). Dans ce domaine, le témoignage d'Alain Daniélou est décisif. Ce qu'il nous apprend des fondements philosophiques, historiques et sociaux du système des castes est remarquable d'intelligence et de pondération: «le système des castes, dans l'Inde, a été créé dans le but de permettre à des races, des civilisations, des entités culturelles ou religieuses très diverses de coexister. Il fonctionne depuis près de 4000 ans avec des résultats remarquables. Quels que soient les défauts qu'il présente, ce but essentiel ne doit pas être oublié. Le principe fondamental de l'institution des castes est la reconnaissance du droit de tout groupe à la survie, au maintien de ses institutions, de ses croyances, de sa religion, de sa langue, de sa culture, et le droit pour chaque race de perpétuer, c'est-à-dire le droit de l'enfant de continuer une lignée, de bénéficier de l'héritage génétique affiné par une longue série d'ancêtres. Ceci implique l'interdiction des mélanges, de la procréation entre races et entités culturelles diverses. “Le principe de toute vie, de tout progrès, de toute énergie, réside dans les différences, les contrastes”, enseigne la cosmologie hindoue. “Le nivellement est la mort”, qu'il s'agisse de la matière, de la vie, de la société, de toutes les formes d'énergie. Tout l'équilibre du monde est basé sur la coexistence et l'interdépendance des espèces et de leurs variétés. Encore de nos jours, une des caractéristiques du monde indien est la variété des types humains, leur beauté, leur fierté, leur style, leur ‘race’, et ceci à tous les niveaux de la société. Tout groupe humain, laissé à lui-même, s'organise selon ses goûts, ses aptitudes, ses besoins. Ceux-ci étant différents, l'essentiel de la liberté, de l'égalité, consiste à respecter ces différences. Une justice sociale digne de ce nom ne peut que respecter le droit de chaque individu, mais aussi de chaque groupe humain, de vivre selon sa nature, innée ou acquise, dans le cadre de son héritage linguistique, culturel, moral, religieux qui forme la gangue protectrice permettant le développement harmonieux de sa personnalité. Toute tentative de nivellement se fait sur base d'un groupe dominant et aboutit inévitablement à la destruction des valeurs propres des autres groupes, à l'asservissement, à l'écrasement physique, spirituel ou mental des plus faibles. Ceux-ci, par contre, s'ils sont assimilés en assez grand nombre, prennent leur revanche en sabotant graduellement les vertus et les institutions de ceux qui les ont accueillis ou asservis. C'est ainsi que finissent les Empires» (19).

Face à cette déliquescence se bâtiront de nouveaux Empires, dans le respect de l'autonomie, de la personnalité et des croyances des différentes ethnies qu'ils chapeauteront. Dans ce contexte, l'Inde est appelée à jouer un rôle actif aux côtés d'une Europe assumant son antique vocation impériale et grande-continentale, elle «constitue l'une des clefs de voûte d'un édifice appelé à braver les siècles: le grand espace eurasiatique qui reposera, pour nos régions, sur un pôle carolingien (franco-allemand) enfin réactivé» (20). Seul ce bloc impérial peut faire front aux visées expansionnistes des Etats-Unis et, par-delà, au projet d'homogénéisation planétaire.

Une éthique au service de l'Imperium

La puissance d'une nation repose sur la force de ses citoyens. En ce sens, les Dieux, en tant que personnifications des forces naturelles et par-delà, symboles de la plénitude des valeurs, sont des modèles à suivre pour tout citoyen, lequel choisit une ou plusieurs Divinités tutélaires, incarnations de ses exigences morales et spirituelles. Les Dieux sont donc d'authentiques archétypes qui nous renvoient à notre singularité, à notre aspiration au dépassement. Le Polythéisme permet «aux hommes, tous uniques, d'adorer le Dieu correspondant à leur nature profonde (Sol et Luna par exemple), à leur héritage (un Bantou ou un Lapon n'adoreront pas les mêmes divinités qu'un Mexicain), à l'étape de leur quête spirituelle (sans pour autant forcer quiconque à en mener une, comme dans certain Catholicisme hypocrite), à l'âge de la vie... A chacun selon ses possibilités et ses désirs» (21).

Qui parle de modèles, doit parler de mise en critique, seule capable de faire avancer la pensée: se dessine alors la réflexion philosophique, avec sa volonté de chercher et de choisir en toute liberté d'esprit. Instigateur d'une démarche et d'un engagement, le Polythéisme est donc la religion par excellence de l'homme responsable qui, par son action, contribue à l'équilibre de la société et au-delà à celui du Cosmos. A chacun dès lors de jouer pleinement le rôle que lui a assigné le Destin dans l'Ordre sociocosmique. En ce sens, le respect des contrats et des engagements, la fidélité à la parole donnée sont essentiels, comme le sont le maintien des diversités, la reconnaissance de tous les dons et talents. La multiplicité des rôles est en effet le gage du plein épanouissement de toute société: «tous les hommes sont égaux en droit (au singulier). Cela ne signifie pas qu'ils aient les mêmes droits. Etant extraordinairement différents, et chacun n'ayant droit qu'à ce dont il est capable (sans léser autrui), les hommes ont des droits différents. Une société fondée sur l'égalité des chances aboutirait ainsi à l'émergence d'une aristocratie naturelle» (22). Cette vision doit pousser chacun de nous à devenir celui qu'il est destiné à devenir, à conquérir le Royaume invisible qu'il porte en lui. Le fameux adage “Connais-toi toi-même et tu connaîtras l'univers et les Dieux” (le Gnôthi seauton hellénique) prend alors tout son sens. Cette éthique souveraine s'oppose à la présomption des religions de la Révélation où, pour être admis à participer au Divin, l'homme doit recevoir la grâce d'un Dieu personnel. Le Polythéisme est donc porteur d'une plénitude de sens dont les religions schématiques ont écrasé la richesse. La caractéristique principale des Monothéismes est en effet «la réduction: le Monothéisme coupe, tranche, réduit les éléments de la vie pour n'en garder que ce qu'il considère comme essentiel. Voilà l'essence du Monothéisme: aux capacités multiples de la Déité, il n'en retient que telle ou telle. La différence avec le Polythéisme grec est nette: le Monothéisme judéo-chrétien fonctionne sur la réduction. Et la modernité n'est que la forme laïcisé de cette réduction monothéiste judéo-chrétienne, avec la Parousie, les conceptions sotériologiques,... qui trouvent leur aboutissement, et peut-être leur achèvement, dans la forme profane qu'est le rationalisme moderne» (23). Apparaissent les vérités uniques, leurs ukases et ostracismes, comme les idées collectives, catéchismes niais à l'usage des masses. Le Polythéiste quant à lui reconnaît la richesse et la pluralité du monde. Il sait que “sa” religion n'est qu'une approche et ne refuse pas de prendre en compte celle des autres, d'où son absence de prosélytisme: «l'essence même du Polythéisme est la tolérance, l'essence du Monothéisme est l'intolérance et le fanatisme qui l'accompagne. Il suffit de se pencher sur l'histoire des religions pour s'en convaincre. Jamais on ne pourra me citer une religion polythéiste qui ait fait de l'intolérance son principe fondamental. Et qu'on ne vienne pas nous parler des persécutions, car, outre le fait que nombre d'entre elles sont de pures inventions des auteurs des Actes des Martyrs, elles n'avaient pas un caractère religieux, mais politique... Alors que tous les génocides de l'histoire, même s'ils n'ont que rarement pu aller jusqu'à une solution finale, aussi bien que les ethnocides, se sont perpétrés au nom d'une idéologie monolâtrique. Sans compter le fait que tout Monothéisme est destructeur de toute tradition ancestrale. Ainsi en a-t-il été dès que les Chrétiens ont triomphé. Dois-je citer la destruction des civilisations de l'Amérique latine, et surtout le plus grand génocide de l'histoire, celui des Indiens de l'Amérique du Nord par les trop fameuses tuniques bleues, et le plus petit, mais le plus complet, celui des Tasmaniens par le colonisateur anglais? De l'idéologie monothéiste sont nées les idéologies réductionnistes politiques, tout aussi destructrices, j'entends le national-socialisme et le communisme, si proches dans leurs principes et leur finalité, que je m'étonne qu'on puisse encore se dire communiste après les crimes dont cette idéologie s'est souillée» (24). Face aux folies et à l'“hybris”, les Dieux nous ont toujours montré la juste voie. Avec eux, les totalitarismes, héritiers d'une conception aliénante de la relation homme-nature, esprit-corps, raison-sentiments, n'auraient pu prendre racines: la sagesse du “juste milieu” (le remarquable mèden agan delphique: rien de trop) les aurait immédiatement refoulés!

Amor Fati

Pour les Païens, il n'existe pas de transcendance absolue, de Toute Puissance, tel Big Brother, distribuant châtiments et saluts, béquilles d'une humanité incapable de faire face à ses responsabilités. Les Dieux sont nés du chaos initial : ils sont des émanations du monde où ils se manifestent. La perspective d'un au-delà, au sens chrétien, est donc totalement absurde pour un Païen, nous rappelle Christopher Gérard dans le premier Cahier d'Etudes Polythéistes (25). Le Païen conçoit plutôt l'ici-bas comme lieu d'enchantements multiples: il suffit d'ouvrir les yeux pour en être convaincu. D'où l'importance —maintes fois soulignée dans Antaios— du regard, de ce que les Grecs, nos maîtres, appelaient théôria, l'observation des manifestations du Divin: la splendeur d'un orage, l'éclat du soleil, la clarté de la lune dans une clairière enneigée, les flammes rousses d'un grand feu dans la nuit, une vague déferlante, le rire d'un enfant, la beauté d'une femme,... Non, le monde n'est pas désenchanté! C'est le regard de la plupart des hommes d'aujourd'hui qui est dévitalisé. Les manifestations du Divin éclatent partout: à nous de les honorer par nos actes et nos œuvres, nous rendons ainsi grâce aux Dieux. L'esprit souffle en tous lieux: à nous de découvrir nos “lieux de mémoire”, lieux d'attaches et de souvenirs. «Pour ma part, je ne peux passer par Rome sans aller saluer le Panthéon, qui me paraît représenter, je ne sais pourquoi, l'esprit du Paganisme. Dans la Ville, je rends toujours une visite émue au Mithraeum souterrain de san Clemente et, flânant sur le Forum, je pense aux cendres d'Henry de Montherlant, fidèle de Sol Invictus. Je rends aussi visite à la Curie: je n'ai pas oublié que c'est là que Symmaque et toute l'aristocratie paienne siégèrent et, lors de l'Affaire de l'Autel de la Victoire, défendirent la liberté de conscience contre les diktats de l'Eglise. A Mistra, j'ai arpenté les rues de la ville fantôme en invoquant les mânes de Georges Gémisthe Pléthon, le philosophe néo-paien. Brocéliande, les Iles d'Aran, Athènes (l'Hephaisteon), et tout récemment Bénarès, la Ville Sainte, m'ont transporté d'enthousiasme et permis de percevoir les manifestations du divin. Expérience que l'on peut aussi vivre dans d'humbles sanctuaires celtes ou gallo-romains, et même dans de petites églises de campagne» (26), Christopher Gérard s'en fait le témoin: l'enchantement réside en nous-mêmes et dans le clair regard sur ce monde auquel nous sommes inextricablement liés.

L'homme libre tâche donc de se réaliser hic et nunc: «la valeur a à être donnée à la vie. La vie n'a pas de valeur par elle-même mais par ce que l'on en fait. On refuse de se laisser porter par la vie. La vie doit être vécue en volonté, sur le fond d'une décision résolue de création. Car la manière de donner de la valeur à la vie ne peut être la répétition du même, la répétition du morne, mais la création. Si je ne fais que me répéter, qu'importe l'interruption de la mort? Mais si je crée, de telle sorte que, par la mort, ce qui pouvait être cesse définitivement de pouvoir être, en ce cas, il y a bien une perte absolue... Certes! Mais il s'agit, précisément, de donner la plus haute valeur à ce qui doit périr» (27). Tel est le sens du Tragique, élément fondamental de la conception païenne du monde, claire conscience du Destin qui tranche implacablement la vie porteuse de fruits. Cet inexorabile Fatum cher à Virgile se manifeste aussi à tout homme qui voit ses choix et ses actes, pris dans l'engrenage de l'Ordre inviolable du monde, tout à la fois le dépasser et avoir des répercussions qu'il ne peut contrôler. Malgré la conscience aiguë de ces limites, nul pathos, nul fatalisme n'accablent le Païen. Sans cesse il surmonte l'adversité, il maintient le cap, garde l'allure, ne comptant que sur lui (bel exemple du fameux meghin nordique: la foi en ses propres capacités). Tel est son honneur.

On comprend donc qu'Antaios soit lue par les cherchants, les esprits libres, que la revue fasse place large à des écrivains non-conformistes et francs-tireurs (28). Face aux personnes dociles, adaptées aux dogmes cauteleux du politiquement correct, face aux baudruches qui voudraient nous dicter nos modes d'agir et de réfléchir, Antaios éclate d'un rire incoercible qui n'a rien à voir avec la dérision confortable et en fin de compte résignée qui envahit ce monde vétuste. Frondeur, le rire d'Antaios conserve toute sa force dévastatrice: à chaque page, on bute sur une observation qui oblige à revoir positions faciles et plates certitudes. Par ces temps de pensée unique, il importe bien de marteler impitoyablement conformismes et dogmes...

Repenser la tradition païenne

La spiritualité païenne n'est en rien «la nostalgie de l'Age d'Or, du paradis avec son désir puéril de retour vers un état préscientifique, trop proche du mythe chrétien du péché originel. Elle n'est pas non plus une fuite hors du monde, qui serait la négation de notre esprit héroico-tragique: le Paien est de ce monde. Nulle macération, nul masochisme dans son impérial détachement. Le Paganisme n'est pas non plus un retour à des superstitions révolues, une sorte d'irrationalisme archéologique: nul refus de la science, de la technique, bien au contraire. Nul rejet de la raison, qu'il nous faut utiliser et intégrer comme outil dans notre Quête. Etre Paien au XXe siècle ne consiste pas à se livrer à des pratiques bizarres de “magie” ni à des cérémonies où l'exhibitionnisme le dispute au grotesque. En ce sens, le Paganisme ne s'identifie nullement à sa forme dégénérée, la sorcellerie, comme le prétendent divers mouvements américains» (29).

Antaios est tout sauf une revue prospérant dans la rengaine nostalgique: ni repli dans une tour d'ivoire, ni regret frileux du passé, ni sentiment d'impuissance face à la modernité. Au contraire, elle fait le lien entre notre héritage ancestral et les exigences les plus novatrices du XXIème siècle. Car être Païen ne signifie pas tant renier le monde moderne que rechercher en lui la profondeur de ses racines, véritables garantes contre le triomphe de la superficialité, la durée éphémère des modes, le diktat de l'immédiateté, tous privilégiés, au nom du sacro-saint Progrès, par notre société. C'est par la mémoire que l'homme échappe à cette tyrannie de l'instant pour vivre dans l'éternité. La mémoire est chère au savant, à l'artiste et au lettré qui se remémorent pour mieux inventer et créer, elle l'est au citoyen qui se souvient des expériences passées pour mieux agir et décider. Par contre, le projet révolutionnaire de faire du passé table rase, comme le chantent les attardés de l'Internationale et les apôtres de l'amnésie consumériste, est un projet nihiliste et destructeur de l'homme dans ses racines. Comme si en coupant les anciennes racines de l'arbre, celui-ci pouvait prospérer sur ses plus récentes radicelles, jouets d'une saison, sans doute inaptes à soutenir la succession des orages et les pluies de l'adversité! Antaios se fait le chantre de la mémoire. Son directeur explique qu'il se considère comme une sorte d'“archéologue de la mémoire” (30). Au travers d'Antaios, il recherche en effet le noyau intérieur de notre culture et opère recours à sa spécificité et à ses Dieux, toujours vivants: «nous autres Paiens concevons le temps comme cyclique, à l'image des cycles cosmiques (solaire par exemple, avec les équinoxes et les solstices)... Le temps des Paiens est celui de l'Eternel Retour, pareil à la grande Roue qui tourne et tourne sans répit... Pour nous, il n'y a pas d'apocalypse, mais bien d'innombrables fins de cycles, éternellement recommencés. Une succession sans début ni fin de naissances, de croissances et de déclins, de crépuscules suivis de rénovations, de cataclysmes suivis de renaissances, au sein d'un Ordre (en grec: ‘Kosmos’) intemporel, où hommes et Dieux, mortels et Immortels, ont leur place et leur fonction. Le mythe du Progrès n'est pas le nôtre. Nous ne croyons pas au sens de l'histoire (concept à mes yeux totalitaire), à la ‘fin’ du Paganisme, à la ‘mort’ des Dieux... Si le temps est linéaire, comme le prétendent les théologies judéo-chrétienne et rationaliste, le Paganisme est impensable puisque ‘mort’, et scandaleux puisqu'allant à l'encontre du sacrosaint sens de l'histoire. Mais si comme nous le pressentons, le temps est cyclique, la perspective change du tout au tout... Si ses formes anciennes (liturgies, temples,...) ont cédé la place à d'autres qui s'en sont souvent largement inspiré, les archétypes, qui sont eux éternels, demeurent» (31).

Recourir aux Dieux ne signifie donc ni les embaumer, ni inventer des cultes incertains, mais s'alimenter à leur flamme et les repenser à la lueur de nos propres idéaux, attitudes qui nous préservent d'une hypertrophie de la mémoire et de créations pastiches, sans souffle, comme le sont le New Age et son cosmopolitisme niveleur, le rosicrucisme avec ses "initiations" payantes, la Wicca avec sa complaisance pour le "luciférisme" et autres miasmes putrides (32),... Les Dieux ne doivent pas devenir un refuge contre le monde contemporain, mais s'affirmer comme le creuset du Volksgeist de notre époque, ce qu'Antaios a compris: «le Paganisme a changé depuis les origines et il continuera à changer: les Paiens du IIIème millénaire seront à la fois proches et différents de leurs ancêtres celtes, grecs ou slaves. Car, au contraire des vieilles religions monothéistes figées dans les écritures de moins en moins lues et des dogmes risibles, le Paganisme est éternellement jeune puisqu'il évolue avec les peuples» (33).

Face au monde d'aujourd'hui, Antaios rappelle encore que la recherche du sens de l'univers est aussi liée à la science. Non pas une science mue, tel un pantin, par un déterminisme draconien, mais une science qui apprend l'humilité face à la nature. Un monde scientifique qui, lorsqu'il se tourne vers l'infiniment grand et l'infiniment petit, constate que l'horizon, loin de se rétrécir, s'élargit dans une perspective immense. Un monde scientifique qui se tient sur un seuil et se sent alors pris de vertige, je dirais: émerveillé. Comment pourrait-il en être autrement? Si, au-delà de démonstrations toujours incertaines et fragmentaires, la science ne peut indiquer à l'homme de certitudes, elle peut cependant l'aider à se déployer et, en tout cas, lui permettre de “sentir” l'Infini. La science (logos) se rapproche alors du mythe (muthos) comme mode de connaissances, producteur de sens (34)...

Fides Aeterna: «c'est ce qui me frappe chez mes amis Hindous: cette fidélité à leur héritage plurimillénaire, ce refus de la rupture que constituerait la conversion, ce reniement. Je pense à ceux qui refusèrent de céder: les Saxons de Verden, les ‘pagani’ de nos campagnes, ces philosophes d'Athènes chassés de l'Université d'Athènes en 529 et un temps réfugiés en Perse... Je pense à cette chaîne, interrompue certes, de Paiens, fidèles aux Dieux, parfois clandestins, toujours résistants, qui rythment l'histoire de notre continent. En maintenant Antaios, je leur rends l'hommage qui leur est dû» (35). Fides Aeterna, telle est la belle devise d'Antaios qui, dans un monde voué aux ruptures, renoue les liens essentiels et offre à ses lecteurs un fil d'Ariane dans la confusion de notre temps. Saluons Antaios, comme l'ont saluée, l'été dernier, les Brahmanes de Bénarès qui, à l'instar d'Ernst Jünger, encouragèrent Christopher Gérard à persévérer dans une œuvre appelée à triompher du temps...

Anne MUNSBACH.

Pour tout renseignement: Antaios, 168/2 rue Washington, B-1050 Bruxelles. Email: antaios-bru@hotmail.com

Notes:

(1) Isabelle ROZET, Le Mythe comme enjeu: la revue Antaios de Jünger et Eliade in Antaios 2, équinoxe d'automne 1993, p.17.

(2) Ernst JUNGER, Siebzig verweht V, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p.191. Dans chaque numéro d'Antaios, Christopher Gérard salue Ernst Jünger à travers la chronique «Jüngeriana» qui fait le point sur tout —ou presque tout— ce qui se dit et s'écrit sur ce guerrier de l'esprit.

(3) Relire Grimm. Entretien avec Jérémie Benoit in Antaios 12, solstice d'hiver 1997, p.22.

(4)-(6)-(8) Patrick TROUSSON, Le Sacré et le mythe in Antaios 6/7, solstice d'été 1995, p.30-31.

(5) Sur ce sujet, on lira, entre autres, l'entretien que le philosophe Lambros Couloubaritsis a accordé à Antaios 6/7.

(7) Ainsi, une passionnante étude sur Marc. Eemans, peintre et poète surréaliste thiois, éditeur de la revue méta ou para-surréaliste Hermès (1933-1939), les textes à la langue singulière et onirique du très nietzschéen Marc Klugkist, la fascinante figure des frères Grimm, l'anarque Guy Féquant, l'étrange François Augiéras, Henri Michaux, et tant d'autres...

(9) Christopher GERARD, Trouver un ciel au niveau du sol. Par-delà dualisme et nihilisme: une approche paienne, Cahiers d'Etudes Polythéistes 1, Ides de mai 1997, p.111. Qu'ils soient islandais, grec, letton, lithuanien, autrichien, Antaios fait place, au fil de ses numéros, aux différents courants d'une renaissance païenne. On se reportera aussi à l'entretien que Jean-François Mayer a accordé à Antaios: Penser la théopolitique. Entretien avec Jean-François Mayer in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, pp.36-48, il y parle, entre autres, du renouveau païen dans diverses régions du monde.

(10) Jean VERTEMONT, Méditations sur la religion in Antaios 6/7, solstice d'été 1995,p.58.

(11)-(12) Christopher GERARD, Penser le Polythéisme in Antaios 6/7, solstice d'été 1995, p.47. Pour davantage de précisions, on lira L'Empereur Julien, Contre les Galiléens. Une imprécation contre le Christianisme, Ousia, Bruxelles 1995, dont Christopher Gérard nous propose une traduction dépoussiérée, accompagnée de commentaires pertinents ainsi que d'une introduction campant un contexte historique complexe. Dans la postface de l'ouvrage, Lambros Couloubaritsis analyse avec beaucoup d'acuité le sens philosophique et politique de ce traité antichrétien.

(13) Antaios 10, solstice d'été 96 et Antaios 11, solstice d'hiver 1996. A travers une série d'entretiens avec des penseurs de la mouvance hindouiste, ces numéros présentent, entre autres, les thèses du nationalisme hindou.

(14)-(16)-(18) Christopher GERARD, “Hindutva” in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, pp.3-5.

(15) Dans chaque numéro d'Antaios, la chronique “Etudes indo-européennes” passe au crible d'une critique avertie les ouvrages récents consacrés à la “res indo-europeana”.

(17) Jean-Louis GABIN, La Civilisation des différences in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, p.87.

(19) Alain DANIELOU, Castes, égalitarisme et génocides culturels in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, p.102. Les textes d'Alain Daniélou publiés dans Antaios le sont avec l'aimable autorisation de son héritier Jacques Cloarec. Ce dernier a créé un site Internet multilingue dédié à l'œuvre d'Alain Daniélou: http://www.imaginet.fr/-jcloarec/danielou. Une traduction italienne des textes sur le système des castes a été publiée par les éditions Barbarossa: Alain DANIELOU, Caste, egualitarismo e genocidi culturali, Società Editrice Barbarossa, Milano 1997.

(20) Christopher GERARD, “Hindutva” in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, p.5. Pour davantage de précisions sur cette vision impériale, on se reportera aux théories géopolitiques de Karl Haushofer. On lira aussi à ce sujet, Jean PARVULESCO, L'Inde et le mystère de la Lumière du Nord in Antaios 8/9, solstice d'hiver 1995, pp.103-115, qui évoque le rôle réservé à l'Inde dans cet Empire à construire.

(21 ) Christopher GERARD, Penser le Polythéisme in Antaios 6/7, solstice d'été 1995, p.46.

(22) Entretien avec le philosophe Marcel Conche in Antaios 8/9 solstice d'hiver, 1995, p.34.

(23) Eloge du savoir dionysien. Entretien avec Michel Maffesoli in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, p.27.

(24) Le Pèlerinage de Grèce. Entretien avec Guy Rachet in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, pp.16-17. Sur le sujet des totalitarismes, on lira aussi l'entretien que l'ethnologue Robert Jaulin, résistant acharné à toute forme d'ethnocide, avait accordé à Antaios lors de la sortie de son dernier livre L'Univers des totalitarismes (Editions Loris Talmart 1996): L'Univers des totalitarismes. Entretien avec Robert Jaulin in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, pp.33-35.

(25) Christopher GERARD, Trouver un ciel au niveau du sol. Par-delà dualisme et nihilisme: une approche paienne, Cahiers d'Etudes Polythéistes 1, Ides de mai 1997. Ce premier Cahier a été publié à la suite d'une conférence prononcée dans les Ardennes lors d'un colloque “oecuménique” sur le thème de l'au-delà.

(26) Paganisme. Entretien avec Christopher Gérard, directeur d'Antaios in Solaria 10, hiver 1997-98, pp.15-16. Pour obtenir ce numéro, contacter le “Cercle Européen de Recherches sur les Cultes Solaires”, 63 rue Principale, F-67260 Diedendorf.

(27) Entretien avec le philosophe Marcel Conche in Antaios 8/9, solstice d'hiver 1995, p.35.

(28) Au fil des numéros d'Antaios, on suit ainsi la trace de l'insolent Michel Mourlet ou encore de l'inclassable Gabriel Matzneff. On lira notamment l'entretien que chacun des deux écrivains a accordé à Antaios: Entretien avec un Paien d'aujourd'hui: Michel Mourlet in Antaios 1, solstice d'été 1993, pp.11-14 et Portrait d'un anarque. Entretien avec Gabriel Matzneff in Antaios 12, solstice d'hiver 1997, pp.6-12.

(29) Christopher GERARD, Paganus in Antaios 3, équinoxe de printemps 1994, p.21 .

(30) Paganisme. Entretien avec Christopher Gérard, éditeur d'Antaios in Solaria 10, hiver 1997-98, p.13.

(31 ) Christopher GERARD, Trouver un ciel au niveau du sol. Par-delà dualisme et nihilisme: une approche paienne, Cahiers d'Etudes Polythéistes 1, Ides de mai 1997, pp.V-VI.

(32) Antaios a publié une excellente mise au point de son directeur sur la question des rapports entre Paganisme et Satanisme: Christopher GERARD, Wicca et Satanisme: des chemins qui ne mènent nulle part in Antaios 11, solstice d'hiver 1996, pp.37-44.

(33) Christopher GERARD, Paganus in Antaios 3, équinoxe de printemps 1994, p.22.

(34) Antaios n'hésite pas à plonger au cœur des thèmes de prédilection des sciences physiques comme l'espace-temps, la logique, la cosmologie,... pour aboutir au constat qu'il existe des concordances entre science et mythe: ils forment les deux faces d'une même pièce qui serait le réel. Qu'on ne s'y méprenne pas: concordance ne signifie pas identité. Ce qui apparaît, c'est que ces deux approches différentes arrivent à exprimer des points de vue similaires, ou tout au moins complémentaires. Nous recommandons la lecture de l'étude du “conseiller scientifique” d'Antaios , le Docteur ès Sciences Physiques Patrick TROUSSON, Le Sacré et le mythe in Antaios 6/7, solstice d'été 1995, pp. 24-40, un chapitre y est consacré aux rapports entre mythe et science. On lira aussi l'entretien que Jean-François Gautier a accordé à Antaios au sujet de son essai L'Univers existe-t-il? (Actes Sud 1994), où il aborde la question des limites de la science: Entretien avec Jean-François Gautier. L'Univers existe-t-il? in Antaios 10, solstice d'été 1996, pp.54-63.

(35) Paganisme. Entretien avec Christopher Gérard, éditeur d'Antaios in Solaria 10, hiver 1997-98, p.14.

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1999

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1999

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les signes symboliques des monuments funéraires du Schleswig et de la Flandre

Les signes symboliques des monuments funéraires du Schleswig et de la Flandre

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1997

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1997 Manfred MÜLLER:

Manfred MÜLLER: