Swami Vivekananda e il suo tempo, tra modernità e tradizione

Elena BORGHI

Ex: http://www.eurasia-rivista.org/

Il quadro storico

Il periodo storico in cui visse ed operò Swami Vivekananda, la seconda metà dell’Ottocento, fu per l’India un momento particolarmente intenso.

Sul piano politico, caratterizzò questi anni il passaggio del governo dell’India dalla Compagnia delle Indie Orientali alla Corona inglese, che assunse il controllo diretto del Paese nel 1858, a seguito del Mutiny. Considerato da alcuni il primo scoppio del fervore nazionalista ed indipendentista, questo evento ebbe come principali conseguenze un’ondata terribile di violenze e la deriva ancor più autoritaria del governo inglese in India. Certamente, la rivolta fu indicativa del carattere predatorio della Compagnia e del livello di esasperazione da essa indotto nella popolazione, che cominciava a mal sopportare il peso del dominio inglese. Se, infatti, il regime coloniale trasformava gradualmente l’India in una nazione moderna – introducendo infrastrutture, reti di comunicazione, organizzazione della burocrazia e della società civile – d’altro canto il Paese pagava un prezzo altissimo in termini economici, sociali e politici.

Sul piano economico, l’India subì in questo periodo la devastazione causata dai legami sproporzionati tra centro e periferia dell’impero, che distrussero la preesistente economia, anche se, per quanto sfrenato, lo sfruttamento economico dell’India garantiva alla Gran Bretagna guadagni complessivamente piuttosto limitati. L’apporto fondamentale della colonia, infatti, rimase sempre la sua funzione di bacino potenzialmente inesauribile di reclutamento di uomini per l’esercito inglese in India, per l’apparato burocratico coloniale e per l’indentured labour, il sistema di “lavoro a contratto” che sostituì gli schiavi africani con migliaia di contadini e braccianti indiani, trasferiti nelle piantagioni e nelle miniere dei luoghi più disparati, legati a contratti che mascheravano uno stato di effettiva schiavitù.

Questi erano tra gli aspetti che, naturalmente, contribuivano a disintegrare il tessuto sociale indiano; vi si aggiungeva il portato del bagaglio ideologico introdotto dal regime coloniale, che cooperò enormemente alla cristallizzazione delle differenze castali e religiose e, dunque, alla frammentazione della società indiana in una miriade di blocchi contrapposti ed ostili, chiusi a livello endogamico, regolati da criteri gerarchici e definiti su basi di purezza razziale e rituale.

I movimenti di riforma

Di pari passo con il potere coloniale, cresceva lo scontento ed il senso di inadeguatezza di alcune categorie, perlopiù intellettuali di classe media ed estrazione urbana, figli di un’educazione di stampo occidentale, dalla cui iniziativa scaturì quel processo di rinnovamento sociale e culturale – nonché di ridefinizione identitaria, presa di coscienza nazionale e critica del regime coloniale – che investì l’India nel periodo in esame.

Si trattò di un periodo di fermento culturale e di tentativi di riforma sociale e religiosa, volti a ripensare le pratiche considerate più aberranti della tradizione hindu (come la sati, l’immolazione delle vedove sulla pira del marito, o il matrimonio infantile), a diffondere un’istruzione di tipo moderno, a ridiscutere la condizione femminile. Motore e scopo ultimo di questi movimenti era l’acquisizione di strumenti atti ad affrontare «l’esibita superiorità dell’Occidente cristiano nei confronti della cultura e delle religioni indiane»1, come dimostrarono, in particolare, le misure a favore dell’istruzione femminile. Auspicate dai riformatori per motivi che poco avevano a che fare con il reale desiderio di apportare miglioramenti alla generale condizione delle donne, queste misure si rivelarono, in realtà, necessarie ad altri scopi: confutare le teorie europee – secondo le quali la discriminazione cui erano sottoposte le donne in India e la loro condizione erano immagine dell’arretratezza del Paese in generale –, dando prova dell’adeguatezza dell’India all’autogoverno; creare “nuove donne indiane” capaci di essere mogli e madri più adatte alle necessità (pratiche, ma anche identitarie e d’immagine) della classe emergente, e di socializzarne i valori e le aspirazioni, pur entro i confini della tradizione patriarcale, che restava per i riformatori un punto fermo e indiscutibile.2

In ambito religioso, la riforma si concretizzò nelle figure di alcuni pensatori e nella fondazione di istituzioni, volte a rivedere le più grandi tradizioni indiane – hindu e musulmana – alla luce di uno spirito più moderno e razionale.

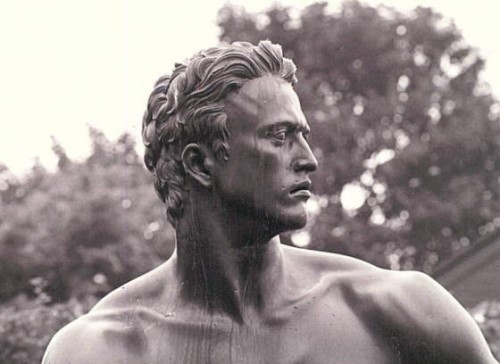

È tra questi riformatori che si colloca Vivekananda, al secolo Narendranath Datta, nato in quella Calcutta all’epoca centro della vita politica e culturale del Paese, e in una famiglia di scienziati e pensatori illustri.

Fin da bambino profondamente interessato ai temi dell’Hinduismo e della meditazione e dotato di un carisma e di una passione per la ricerca della verità inusuali per la sua età, Narendranath ricevette un’istruzione di stampo occidentale, appassionandosi in particolare alla filosofia, e coltivando allo stesso tempo lo studio della poesia sanscrita, dei testi sacri e degli scritti del riformatore suo contemporaneo Rammohan Ray.

Razionale, dedito al ragionamento logico e sprezzante dei dogmi religiosi tradizionali, Narendranath si avvicinò al Brahma Samaj, l’istituzione fondata a Calcutta nel 1828 da Rammohan Ray al fine di operare una trasformazione dello Hinduismo in senso moderno, depurando la religione dalle pratiche più barbare ed introducendo nello studio della stessa il principio di ragione. Narendranath, affascinato dalle arringhe dei riformatori che facevano parte del movimento, sembrava destinato ad una carriera del tutto simile, borghese e socialmente impegnata, fino a quando un incontro introdusse nel suo percorso un cambiamento di rotta.

Da Narendranath a Vivekananda

Era il 1880, quando Narendranath incontrò per la prima volta Ramakrishna, il sacerdote officiante di un tempio situato a Dakshineshwar, un sobborgo di Calcutta, e dedicato ad una forma del dio Shiva, che veniva lì adorato insieme alla dea Kali. Brahmano di estrazione contadina, con un’istruzione limitata cui sopperivano buon senso, mitezza e profonda devozione, costui era un rinunciante di eccezionale spessore, un rappresentante della corrente mistica della bhakti, la “devozione”, e un punto di riferimento per gli intellettuali bengalesi, affascinati dalla schiettezza dei suoi insegnamenti.

Quell’incontro provocò un imponente cambiamento nella vita del giovane Narendranath, che in pochi anni, durante i quali proseguì nel tentativo di conciliare il materialismo delle scienze occidentali e lo spiritualismo in cui lo precipitavano i momenti a Dakshineshwar, divenne il discepolo prediletto di Ramakrishna. Come il suo Maestro, divenne un Advaitavedantin, un sostenitore dell’indirizzo dottrinale del non-dualismo, che predicava l’unità tra Sé individuale e Assoluto. Da questi insegnamenti Narendranath avrebbe in seguito derivato la convinzione della divinità degli esseri umani, dunque la considerazione di tutte le forme dell’esistenza quali manifestazioni dello spirito divino.

Nel 1886 Ramakrishna, dopo aver iniziato i discepoli alla loro nuova condizione di sanyasin3, indicò Narendranath come loro guida. Fu così che egli divenne Vivekananda, “colui che ha la beatitudine della discriminazione spirituale”. Due anni più tardi Vivekananda cominciò la sua vita di parivrajaka, “monaco errante”, partendo per un pellegrinaggio che durò anni, un viaggio solitario compiuto a piedi sulle strade polverose dell’India, dallo Himalaya fino a Kanyakumari. Questa esperienza fornì a Vivekananda una conoscenza profonda del Paese, quale non aveva mai posseduto. Alla fine del viaggio, quando finalmente raggiunse Kanyakumari, Vivekananda rifletté su tutto quello che aveva visto: «Un Paese dove milioni di persone vivono dei fiori della pianta mohua, e un milione o due di sadhu e circa cento milioni di brahmani succhiano il sangue di queste persone, senza fare il minimo sforzo per migliorare la loro condizione, è un Paese o l’inferno? È quella una religione, o la danza del diavolo?»4

Partito con l’obiettivo di portare unità tra le varie sette e confessioni indiane, radunandole sotto l’ombrello del messaggio vedantico, Vivekananda comprese che al suo Paese servivano istruzione e cibo, più che insegnamenti religiosi. Ripensò a quel che aveva sentito dire alcuni mesi prima, circa l’organizzazione a Chicago del World’s Parliament of Religions, un congresso che avrebbe ospitato rappresentanti di ogni religione del mondo; Vivekananda decise che si sarebbe recato negli Stati Uniti, per predicare il messaggio vedantico e chiedere in cambio il sostegno economico necessario a fondare in India istituzioni educative e caritative per le classi più svantaggiate.

Pochi mesi più tardi ebbe inizio la sua missione in Occidente, che lo vide tenere innumerevoli conferenze e radunare intorno a sé molti sostenitori.

Un pensiero moderno e rivoluzionario

Attualizzando gli aspetti religioso-filosofici della dottrina vedantica, all’interno di un pensiero in cui la speculazione teorica e dogmatica veniva costantemente riportata alle necessità pratiche del suo tempo e del suo luogo – percepite come urgenti ed imprescindibili –, Vivekananda divenne l’esempio di una nuova tipologia di riformatore, capace di coniugare gli insegnamenti ancestrali del pensiero vedantico con l’attualità dell’India più comune. Questa narrazione, dunque – a differenza di quelle costruite da altri riformatori, che auspicavano un ripensamento, quando non un distacco, della “tradizione” sociale e religiosa, sentita come ostacolo al “progresso” –, non presupponeva una revisione in chiave filo-occidentale del bagaglio culturale e religioso indiano, bensì glorificava quel passato, proponendolo come la chiave che avrebbe aperto all’India le porte della giustizia sociale, dell’istruzione, dello sviluppo materiale e spirituale.

«La società più grande è quella in cui le verità più alte diventano concrete»5, sosteneva Vivekananda, facendo riferimento alla necessità di costruire una società strutturata in modo da permettere la realizzazione della divinità umana. Da questa convinzione di base, derivata dalla filosofia vedantica, egli ricavò il suo progetto di società utopica, che si sarebbe retta sul pilastro dell’uguaglianza tra gli uomini. Il fatto che egli ritenesse necessarie all’avverarsi di questa idea da un lato la diffusione dell’istruzione – che doveva diventare di massa, affinché gli strati più svantaggiati acquisissero forza e coscienza del proprio valore – e, dall’altro, la soppressione di ogni privilegio – politico, economico o religioso che fosse – dimostra il carattere rivoluzionario del pensiero di Vivekananda. Diversamente da molti suoi contemporanei, egli non era disposto a prevedere risultati parziali; eppure, l’imponenza di questo progetto e il suo carattere utopico non compromettevano in alcun modo la fede di Vivekananda nella sua realizzabilità.

«Pane! Pane! Non credo in un Dio che non riesce a darmi il pane in questo mondo, mentre mi promette la beatitudine eterna nei cieli! Bah! L’India deve essere affrancata, i poveri devono essere nutriti, l’istruzione deve essere diffusa, e la piaga del potere sacerdotale deve essere eliminata».6

Anche nel suo rapporto ideale con l’Occidente Vivekananda differiva dal resto dei riformatori: non prevedendo né una forma di riverente assimilazione ai suoi valori, né il rifiuto astioso di essi, egli auspicava una sorta di collaborazione e di mutuo scambio di eccellenze: «Direi che la combinazione della mente greca, rappresentata dall’energia dell’Europa, e della spiritualità hindu darebbe origine a una società ideale in India. […] L’India deve imparare dall’Europa la conquista del mondo esteriore, e l’Europa deve imparare dall’India la conquista del mondo interiore. Allora non ci saranno hindu ed europei: ci sarà un’umanità ideale, che ha conquistato entrambi i mondi, quello esterno e quello interno. Noi abbiamo sviluppato una parte dell’umanità, e loro un’altra. È l’unione delle due ciò cui dobbiamo aspirare».7

Ancora, la modernità del pensiero di Vivekananda si espresse nella sua considerazione del gesto filantropico che, come in ambito cristiano, fino a quel momento era stato reputato dal sistema hindu tradizionale una questione privata tra donatore e beneficiario. Egli fu il primo a proporre un’etica del seva (il “servizio”) istituzionalizzata – così come è divenuta la filantropia, un po’ ovunque nel mondo, in tempi recenti –, con lo scopo di garantire una ripartizione equa e il più possibile estesa di azioni di solidarietà nei confronti di persone bisognose: “Fare del bene agli altri è l’unica grande religione universale”8, sosteneva Vivekananda, accordando alla pratica del seva un significato che andava ben oltre la semplice azione filantropica. Teorizzò, inoltre, che la figura sociale più autorevole in India – e dunque più adatta a diffondere un pensiero in certo modo rivoluzionario – era quella del sanyasin. Mentre i suoi contemporanei proponevano modelli borghesi, di uomini d’alta casta colti e mondani, o figure eroiche della tradizione storica e religiosa indiana, Vivekananda individuava nel monaco, nell’asceta e nel rinunciante la sede della saggezza e della credibilità presso il popolo; era a queste figure, estranee ai meccanismi del potere, all’avidità e al perseguimento dell’interesse personale, che Vivekananda avrebbe affidato il compito di diffondere il messaggio, dimostrando ancora una volta l’intransigenza che guidava il suo pensiero.

Su questi pilastri poggiava la Ramakrishna Mission, istituita da Vivekananda a fine secolo quale organizzazione impegnata in ambito sociale e strettamente connessa alla vita del monastero dell’Ordine di Ramakrishna, i cui monaci fondevano nella propria esperienza quotidiana lavoro sociale e pratica spirituale – due aspetti che, completandosi a vicenda, fungevano l’uno da motore dell’altro. Intervenendo inizialmente soprattutto in ambito educativo e nella lotta alla povertà, la Ramakrishna Mission cominciò così in quegli anni il suo servizio all’India, che Vivekananda descriveva in termini angosciati:

Su questi pilastri poggiava la Ramakrishna Mission, istituita da Vivekananda a fine secolo quale organizzazione impegnata in ambito sociale e strettamente connessa alla vita del monastero dell’Ordine di Ramakrishna, i cui monaci fondevano nella propria esperienza quotidiana lavoro sociale e pratica spirituale – due aspetti che, completandosi a vicenda, fungevano l’uno da motore dell’altro. Intervenendo inizialmente soprattutto in ambito educativo e nella lotta alla povertà, la Ramakrishna Mission cominciò così in quegli anni il suo servizio all’India, che Vivekananda descriveva in termini angosciati:

«Fiumi ampi e profondi, gonfi e impetuosi, affascinanti giardini sulle rive del fiume, da fare invidia al celestiale Nandana-Kanana; tra questi meravigliosi giardini si ergono, svettanti verso il cielo, superbi palazzi di marmo, decorati da preziose finiture; ai lati, davanti e dietro, agglomerati di baracche, con muri di fango sgretolati e tetti sconnessi […]; figure emaciate si aggirano qua e là coperte di stracci, con i volti segnati dai solchi profondi di una disperazione e di una povertà vecchie di secoli […]; questa è l’India dei nostri giorni!

[…] Devastazione causata da peste e colera; malaria che consuma le forze del Paese; morte per fame come condizione naturale; carestie mortali che spesso danzano il loro macabro ballo; un kurukshetra di malattie e miseria, un enorme campo per le cremazioni disseminato dalle ossa della speranza perduta.

[…] Un agglomerato di trecento milioni di anime, solo apparentemente umane, gettate fuori dalla vita dall’oppressione della loro stessa gente e delle nazioni straniere, dall’oppressione di coloro che professano la loro stessa religione e di coloro che predicano altre fedi; pazienti nella fatica e nella sofferenza e privati di ogni iniziativa, come schiavi, senza alcuna speranza, senza passato, senza futuro, desiderosi solo di mantenersi in vita in qualche modo, per quanto precario; di natura malinconica, come si confà agli schiavi, per i quali la prosperità dei loro simili è insopportabile. […] Trecento milioni di anime come queste brulicano sul corpo dell’India come altrettanti vermi su una carcassa marcia e puzzolente. Questo è il quadro che si presenta agli occhi dei funzionari inglesi».9

Costituito inizialmente da appena una dozzina di monaci, nei cento e più anni che ci separano dalla sua fondazione l’Ordine di Ramakrishna è oggi un movimento transnazionale di proporzioni enormi, simbolo di pace ed ecumenismo, fondato sulla pratica del servizio disinteressato come metodo per la realizzazione del divino e caratterizzato da un approccio razionale alla religione – considerata non un apparato ritualistico ma una scienza dell’essere e del divenire –, da una tradizione colta e dall’efficacia dei suoi interventi in campo sociale.

Definiscono Ramakrishna Mission e Ramakrishna Math (rispettivamente la componente pratica del movimento e l’organizzazione monastica) le tre caratteristiche che sono state segni distintivi di Vivekananda e del suo operato e che, risultando a tutt’oggi innovative, dimostrano la statura di un riformatore illuminato, rivoluzionario per il tempo e il luogo in cui visse: la modernità – che si esprime nell’attualizzazione dei principi vedantici, e nel collocare nel presente il pensiero guida dell’operato di queste istituzioni; l’universalità – data dal rivolgersi non ad un unico Paese o ad uno specifico gruppo di persone, ma all’umanità intera; e la concretezza – che risiede nel porre i principi teorici e spirituali a servizio del miglioramento delle quotidiane condizioni di vita delle persone.

* Elena Borghi, dottoressa in Studi linguistici e antropologici sull’Eurasia e il Mediterraneo (Università “Ca’ Foscari” di Venezia), è autrice di Sai Baba di Shirdi. Il santo dei mille miracoli (Red, Milano 2010) e Vivekananda. La verità è il mio unico dio (Red, Milano 2009)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Nevertheless, there are many parallel points between the two texts dealing with the liberating identifications. Just as in the Tibetan ritual the destruction of the appearance of distinct entities, which all things perceived in the experiences of the other world may acquire, is indicated as a means of liberation, so in the Egyptian text formulae are repeated by means of which the soul of the dead affirms and realizes its identity with the divine figures.

Nevertheless, there are many parallel points between the two texts dealing with the liberating identifications. Just as in the Tibetan ritual the destruction of the appearance of distinct entities, which all things perceived in the experiences of the other world may acquire, is indicated as a means of liberation, so in the Egyptian text formulae are repeated by means of which the soul of the dead affirms and realizes its identity with the divine figures.

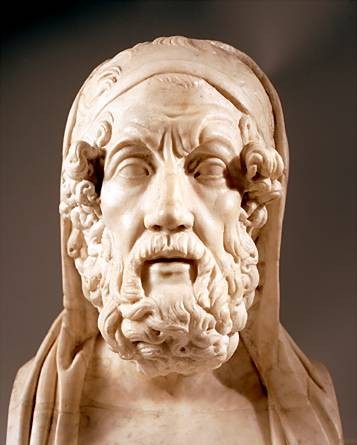

Pour les Anciens, Homère était « le commencement, le milieu et la fin ». Une vision du monde et même une philosophie se déduisent implicitement de ses poèmes. Héraclite en a résumé le socle cosmique par une formulation bien à lui : « L’univers, le même pour tous les êtres, n’a été créé par aucun dieu ni par aucun homme ; mais il a toujours été, est et sera feu éternellement vivant… »

Pour les Anciens, Homère était « le commencement, le milieu et la fin ». Une vision du monde et même une philosophie se déduisent implicitement de ses poèmes. Héraclite en a résumé le socle cosmique par une formulation bien à lui : « L’univers, le même pour tous les êtres, n’a été créé par aucun dieu ni par aucun homme ; mais il a toujours été, est et sera feu éternellement vivant… »

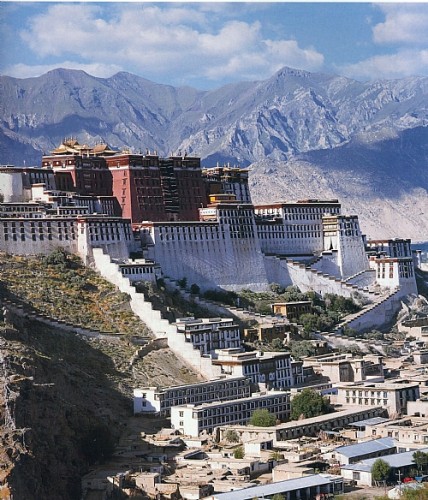

In questi ultimi decenni vari personaggi hanno visto il Tibet come uno degli ultimi territori del Pianeta dove si siano conservate le antiche tradizioni dei cosiddetti “indoeuropei”.

In questi ultimi decenni vari personaggi hanno visto il Tibet come uno degli ultimi territori del Pianeta dove si siano conservate le antiche tradizioni dei cosiddetti “indoeuropei”.

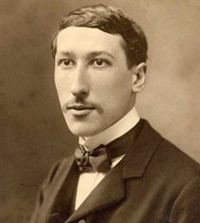

On January 7th, 1951, the Frenchman René Guénon, one of the principal representatives of Traditional thought in the 20th century, died in Cairo.

On January 7th, 1951, the Frenchman René Guénon, one of the principal representatives of Traditional thought in the 20th century, died in Cairo. Ananda

Ananda

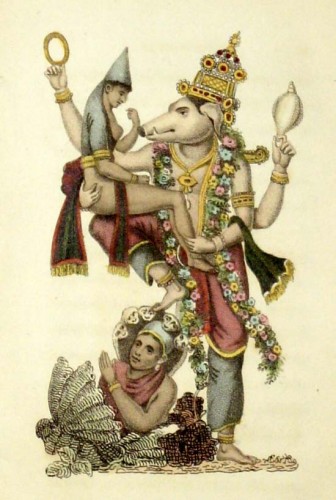

Vishnou le Sanglier

Vishnou le Sanglier

Su questi pilastri poggiava la Ramakrishna Mission, istituita da Vivekananda a fine secolo quale organizzazione impegnata in ambito sociale e strettamente connessa alla vita del monastero dell’Ordine di Ramakrishna, i cui monaci fondevano nella propria esperienza quotidiana lavoro sociale e pratica spirituale – due aspetti che, completandosi a vicenda, fungevano l’uno da motore dell’altro. Intervenendo inizialmente soprattutto in ambito educativo e nella lotta alla povertà, la Ramakrishna Mission cominciò così in quegli anni il suo servizio all’India, che Vivekananda descriveva in termini angosciati:

Su questi pilastri poggiava la Ramakrishna Mission, istituita da Vivekananda a fine secolo quale organizzazione impegnata in ambito sociale e strettamente connessa alla vita del monastero dell’Ordine di Ramakrishna, i cui monaci fondevano nella propria esperienza quotidiana lavoro sociale e pratica spirituale – due aspetti che, completandosi a vicenda, fungevano l’uno da motore dell’altro. Intervenendo inizialmente soprattutto in ambito educativo e nella lotta alla povertà, la Ramakrishna Mission cominciò così in quegli anni il suo servizio all’India, che Vivekananda descriveva in termini angosciati: Yezidism is a fascinating part of the rich cultural mosaic of the Middle East. Yezidis emerged for the first time in the 12th century in the Kurdish mountains of northern Iraq. Their religion, which has become notorious for its associations with 'devil worship', is in fact an intricate syncretic system of belief, incorporating elements from proto-Indo-European religions, early Persian faiths like Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, Sufism and regional paganism like Mithraism. Birgul Acikyildiz offers a comprehensive appraisal of Yezidi religion, society and culture. Written without presupposing any prior knowledge about Yezidism, and in an accessible and readable style, her book examines Yezidis not only from a religious point of view but as a historical and social phenomenon. She throws light on the origins of Yezidism, and charts its historical development - from its beginnings to the present - as part of the general history of the Kurds.

Yezidism is a fascinating part of the rich cultural mosaic of the Middle East. Yezidis emerged for the first time in the 12th century in the Kurdish mountains of northern Iraq. Their religion, which has become notorious for its associations with 'devil worship', is in fact an intricate syncretic system of belief, incorporating elements from proto-Indo-European religions, early Persian faiths like Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, Sufism and regional paganism like Mithraism. Birgul Acikyildiz offers a comprehensive appraisal of Yezidi religion, society and culture. Written without presupposing any prior knowledge about Yezidism, and in an accessible and readable style, her book examines Yezidis not only from a religious point of view but as a historical and social phenomenon. She throws light on the origins of Yezidism, and charts its historical development - from its beginnings to the present - as part of the general history of the Kurds. Muchos habrán oído hablar del famoso

Muchos habrán oído hablar del famoso