WALLASCH: Die Identitären auf dem Brandenburger Tor – was lesen Sie, wie bewerten Sie für sich Aktion und Reaktion, die etwa der Regierende Bürgermeister als “widerlich” bezeichnete?

KUBITSCHEK: Die Aktion der Identitären Bewegung am Brandenburger Tor folgt einer Raum- und Wortergreifungsstrategie innerhalb der Medienmechanismen unserer Zeit. Wer keine Macht hat, seine Botschaft auf allen Kanälen in die öffentliche Wahrnehmung zu drücken, muß anders vorgehen, jäh, spektakulär, überrumpelnd. Man macht etwas, worüber berichtet werden muß! Die Öffentlichkeitswirksamkeit der Aktion läßt sich vom Markenwert her kaum beziffern. Stellen Sie sich den finanziellen Aufwand an Printanzeigen, Audio- oder Videowerbung vor, der nötig wäre, um auch nur annähernd denselben Effekt zu erzielen. Das Bild mit dem Breitbanner über dem Brandenburger Tor wird darüber hinaus Kultstatus unter jungen Aktivisten erlangen. Die Aktion war außerdem friedlich, mutig, argumentierte unkompliziert und grundvernünftig, was will man als Teil eines Widerstandsmilieus mehr, das dem Motto folgt: »Störe die kleine Ordnung, um die große Ordnung zu bewahren.« Oder mit Jürgen Habermas ausgedrückt: Der zivile Ungehorsam “schließt die vorsätzliche Verletzung einzelner Rechtsnormen ein, ohne den Gehorsam gegenüber der Rechtsordnung im Ganzen zu affizieren.« Ich würde sagen: Selbst widerstandsphilosophisch ist die Identitäre Bewegung auf der sicheren Seite …

WALLASCH: Warum eigentlich nicht gleich Bonhoeffer? Als die Aktion am Brandenburger Tor gelaufen war, haben Ihre Kameraden Identitären ein Video ins Netz gestellt, in allerklarster Leni Riefenstahl Ästhetik, es wurde ja auch von der FAZ negativ erwähnt. War das nicht der deutsche Gruß zum Schluss? Und so etwas wollen Sie sich nun ungefragt von Habermas absegnen lassen? Der nämlich unterscheidet moralische Richtigkeit von theoretischer Wahrheit. Und ein Wahrheitsanspruch besteht niemals unabhängig von der Behauptung, in der er formuliert wird.

KUBITSCHEK: Das Filmchen ist zwei Jahre alt, wurde damals bereits als mißverständlich und falsch verworfen, und jetzt hat es irgendeiner wieder hochgeladen, um ein paar Klicks auf youtube zu ernten. Häutungen, nicht der Rede wert. Und nein: Habermas ist genau der richtige. Denn was moralisch ist, liegt zum Glück nicht in seinem Benehmen, sondern kann ihm aus der Hand genommen werden. Ich vermute in aller Doppeldeutigkeit: Wir sind dran.

WALLASCH: Ist es eher ein Altersproblem, dass Götz Kubitschek heute kein plaktiver Kopf der Identitären ist? Denn im Hintergrund sind Sie ja durchaus einer der Strippenzieher, oder wie es Martin Sellner, der führende Kopf der Identitären im deutschsprachigen Raum ausdrückt: „Schnellroda ist für uns so etwas wie ein geistiges Zentrum.“ Sie selber sprechen in dem Zusammenhang von einer „Vernetzungsstruktur“. Steckt Götz Kubitschek am Ende noch viel intensiver hinter dem deutsch-österreichischem Label der Identitären? Gibt es darüber hinaus finanzielle Vernetzungen?

KUBITSCHEK: Wäre ich zwanzig, fänden Sie mich auf dem Brandenburger Tor! So aber ist es meine Aufgabe, für die Aktivisten ein finanzielles, juristisches, publizistisches und emotionales Auffangnetz knüpfen zu helfen. Außerdem gehöre ich zu denen, die vor Jahren erste Gehversuche in Richtung eines politischen Aktivismus unternahmen: Das war 2008 im Rahmen der sogenannten konservativ-subversiven aktion, und in meinem Bändchen »Provokation« formulierte ich auch die Theorie dazu. Ich habe diesen Text in meine vor einigen Wochen erschienene Aufsatzsammlung »Die Spurbreite des schmalen Grats« erneut aufgenommen, , er gehört zu den wirkmächtigen meiner Arbeiten. Unsere Aktionen und mein Text hat viele inspiriert, die heute – weit professioneller und spektakulärer – diesen Weg ausbauen.

WALLASCH: Sie sagen, Ihre Projekte seien eine Anlaufstelle, für junge Menschen, die „ungebildet verbildet“ wären, „was die politisch-historischen Tatsachen betrifft.“ Welche Verbildungen konnten denn nun speziell die Identitären in Schnellroda lassen und welche deutsch-universelle Wahrheit haben Sie den Kameraden aus Österreich mit in den politischen Kampf gegeben?

KUBITSCHEK: Die jungen Leute hören bei uns auf akademischem Niveau Vorträge quer durchs Gemüsebeet, aber aus konservativer Perspektive. In den vergangenen Monaten kam nun ein bißchen Charakterbildung dazu. Lehre 1: Faßt Mut: Der Kaiser ist nackt; Lehre 2: Die Wirklichkeit ist mit uns; Lehre 3: Hör auf, Dich für Selbstverständliches zu rechtfertigen; Lehre 4: Studieren kann man später noch; Lehre 5: Dieses Land, seine Geschichte, sein Charakter, sein Volk, seine Reife und seine Aufgabe sind so schön und tragisch und wichtig, daß wir nichts davon den Verächtern und Gesellschaftsklempnern überlassen dürfen. (Daß ich dabei die Österreicher einfach eingemeinde, sehen Sie mir bitte nach).

WALLASCH: Wer sind diese Gesellschaftsklempner und Verächter genau und wo sind die, wenn in ihren oder den Träumen Ihrer Anhänger das gelbe Lamda über dem Reichstags weht?

KUBITSCHEK: Sie haben Bilder im Kopf! Wollen Sie als PR-Berater ins Team wechseln? Im Ernst: Mir reichts, wenn ein Heiko Maas, ein Sigmar Gabriel, eine Anneta Kahane undsoweiter keine Rolle mehr spielen, sondern mal ein paar Leute die Leitlinien der Politik bestimmen können, die nicht gegen, sondern für Deutschland sind.

WALLASCH: Sie sind der Medienstar der Rechten bis hin zur FAZ; der linke Vorzeige-Soziologe Armin Nassehi biedert sich mit einem Briefwechsel an, und trotzdem schreiben Sie, sie hätten von den Vertretern der Leitmedien Fairness unterstellt und seien enttäuscht worden. Trifft das auch auf den warmen Artikel von Frau Lühmann in der WeLT zu? Wieviel Bewunderung haben Sie erwartet, als sie den TAZ-Redakteur einließen oder Joachim Bessing, der sie auf einem Youtube-Kanal so verissen hat?

KUBITSCHEK: Frau Lühmann ist in ihrer auf einen beinahe naiven Ton getrimmten Neugier eine Ausnahme, Sie kennen den Text, die Autorin suchte ja gar keine inhaltliche Auseinandersetzung, sondern beschrieb eine Oberfläche, beschrieb, was Sie nach schlimmen Artikeln über uns erwartet hatte, was sie dann tatsächlich vorfand und wie sie ins Grübeln kam, als sie feststellen mußte: Kositza und Kubitschek sind ja ganz anders.

Andreas Speit von der taz stand einfach vor der Tür. Er stand einfach herum, ohne Anmeldung, einfach so, erschrak ein wenig, als ich ihn nach seinen Namen fragte, und bat dann um einen Kaffee. Den bekam er, aber er konnte ja nicht bloß trinken, er mußte reden und Fragen stellen, und mit jeder Minute, die er länger in unserer Küche saß, kam mir die Situation absurder vor: Ich stellte mir vor, meine Frau wäre um die Wohnung von Juliane Nagel oder Katharina König geschlichen und hätte um eine Tasse Kaffee gebeten. Oder ich bei einer dieser antifa-Granaten, die ihre Conewitzer Hundertschaften führen wie Oberfeldwebel ihren Einsatzzug. Jedenfalls platzte mir nach der zehnten banalen Frage von Speit der Kragen, und ich bat ihn, rasch auszutrinken und sich wieder auf die Socken zu machen.

Und Bessing: Der mail-Wechsel vor und unmittelbar nach seinem Besuch war herzlich, er war eitel und fragte selbst nach, ob wir unseren Gesprächsband »tristesse droite« nach seinem »Tristesse Royal« benannt hätten, trank sehr viel, war lustig und ab einem bestimmten Pegel ein bißchen darauf fixiert, uns Rechten mangelnde Wärme und Liebe im Umgang miteinander als unser Grundproblem vorzuhalten. Ich muß sagen: Ich war schon ziemlich schockiert über seine – »Nachbereitung«. Er wollte nämlich ganz anders schreiben, für die NZZ, und zwar inhaltlich. Naja, ich hab das komplette Gespräch auf Tonband, und sollte er nochmals Blödsinn behaupten, stell ich’s ins Netz, ja, vielleicht mache ich das sogar auf jeden Fall.

Sie sehen: Wir sind ein bißchen die Minenhunde, probieren dies und das aus, aber das berührt nicht den Kern unserer Arbeit. und weil wir jetzt doch recht viel ausprobiert haben und das, was wir im Umgang mit den »großen« Medien erlebten, mit den Untersuchungen und dem Vokabular des Medienwissenschaftlers Uwe Krügers ganz gut beschreiben können, müssen nicht noch weitere Experimente sein. Jetzt gehts wieder weg von der Oberfläche, wieder mehr in die »Sicherheit des Schweigens”, mein Briefwechsel mit Marc Jongen von der AfD ist wohl ein erster Beleg dafür, anderes bleibt einfach unbeantwortet oder wird abgelehnt.

WALLASCH: Halten wir also fest, dass es Ihnen trotz Ihrer für die Medien so attraktiven inneren und äußeren Klause um die Bekanntmachung bestimmter Positionen, Ihrer Weltanschauung geht, die wir im Folgenden ja noch betrachten können. Zunächst einmal soll aber auch hier die Oberfläche berührt werden: Vieles an Ihnen und Ihrem Tun erinnert mich an diese „alte Rechte“ der Vorwenderepublik. Falsch beobachtet/interpretiert?

KUBITSCHEK: Ja, das ist natürlich falsch. Mich interessiert das Eindimensionale nicht, und Kommunen, Sinnsuche-Projekten, Reichsbürgern oder anderen, engen Gesinnungsgemeinschaften haftet dieses Eindimensionale fast immer an, verbunden mit einer Hoffnung: Es gäbe die EINE Tür (Friedensvertrag, Heidentum, GmbH-BRD, Holocaust, u.a.), die wir zu öffnen hätten, um in eine bisher verwehrte Freiheit zu gelangen. Aber diese Tür gibt es nicht, und es gibt auch nicht die EINE Prägung (Rasse, Klasse, Raum, Zeit), die uns zu dem macht, was wir sind. Meine Referenzgrößen sind Botho Strauß, Ernst Jünger, Peter Sloterdijk, Arnold Gehlen, Konrad Lorenz, Carl Schmitt, Bernard Willms, Martin Heidegger, Ernst Nolte, Armin Mohler, und dann sehr viele Romanautoren und Dichter, unter den derzeit produktiven u.a. Mosebach, Ransmayr, Jirgl, Klein, Kracht, aus dem Ausland Vosganian, Boyle und natürlich Raspail. Und: Meine Frau und ich stehen nicht gegen »das System«, sondern schauen zusammen mit tausenden Lesern kopfschüttelnd zu, wie dieser Staat seine Verfaßtheit gefährdet, nebenbei die Saftpresse aufstellt und aus uns Fleißigen noch das letzte Tröpfchen preßt, um seine Experimente am Laufen zu halten. Das ist doch etwas ganz anderes als die Errichtung einer halbreligiösen Gesinnungsgemeinschaft, die nach dem Tod ihres Stifters einen Freundeskreis zur Pflege seines Vermächtnisses ins Leben ruft. Ich vergleiche uns mit Theorieverlagen wie Matthes&Seitz, mit Richtungsprojekten wie eigentümlich frei oder auch mit dem »erweiterten Verlegertum« eines Siegfried März – unabhängig, verlegerisch risikofreudig, null abgesichert.

WALLASCH: Sie wollen also viele Türen gleichzeitig oder hintereinander öffnen, um zu einer Ihnen bisher verwehrten Freiheit zu gelangen. Jetzt sage Sie mir doch mal konkret, welche Freiheit Ihnen da fehlt und welchen Vorteil ich davon hätte. Was verändert sich für mich? Und wollen Sie nun Politik mitgestalten oder immer nur der Mann hinter solchen Figuren wie Björn Höcke sein, der Einflüsterer, der Stichwortgeber, der, dessen Botschaften dann entweder schon maximal verzerrt erscheinen oder aus dem Munde von Höcke diese Verzerrung erst erfahren? Warum halten Sie nicht Maß und bleiben beim Machbaren? Ziehen Sie von mir aus nach Bayern, empfehlen Sie sich solchen Politikern wie Horst Seehofer einer ist. Sagen Sie doch bitte mal ganz konkret, wo Ihre Reise hingehen soll, so, als müssten Sie wirklich politische Wegmarken setzen. Da wird Ihnen doch ein Strauß, ein Jünger oder Nolte nicht dabei helfen können. AfD, die Identitären, eigentümlich frei, das sind doch alles völkische Tummelplätze, näher an Rudolf Heß als an sagen wir mal Katrin Göring-Eckardt. Ihnen geht es doch in Wahrheit darum, das politische System selbst aus der Bundesrepublik hinauszufegen. Also sagen Sie es doch so: wenn schon Hasardeur, dann bitte richtig. Was soll dieses intellektuelle Rumgeeire? Das ist doch eine Fluchtburg. Der Rückzug über der Schreibmaschine – auf welches Gesellschaft verändernde Jahrhundertwerk dürfen wir da warten? Und wie lange noch?

KUBITSCHEK: Gegenfragen, wichtig für den weiteren Verlauf unseres Dialogs, denn Sie können nicht einfach irgendetwas behaupten. – 1. Sind Sie tatsächlich der Meinung, ich wolle das politische System der BRD aus derselben fegen? Wenn ja, an welchem meiner Texte oder meiner Reden machen Sie das fest? – 2. Zeigen Sie mir desgleichen, wo ich ein Hasardeur wäre. – 3. Wo ist bei mir das Maßlose? Wiederum bitte: Stellen, Quellen, Sätze.

WALLASCH: Ja, das könnten wir so machen. Ich investigiere auf Sezession, in Reden bei Pegida, aus Sekundärquellen, aus Interviews. Aber nehmen wir es doch der Einfachheithalber mal so: ich spiegel hier den Eindruck, den Sie bei mir hinterlassen haben. Und Sie nutzen die Chance und klären mich auf: Welche Freiheit meinen Sie? Welchen Vorteil hat diese Freiheit für mich? Wie stehen Sie zum politischen System/Parteiensystem der Bundesrepublik? Was ist mit Seehofer? Wie schaffen Sie das, immer so zielgenau diesen reaktionären völkischen Sound zu erzeugen, wenn Sie – das immerhin ein geschickter Schachzug – den französischen Premier Valls zitieren mit ihrem “Wir werden handeln”. Weiter geht es bei Valls ja so, geäußert allerdings unter dem unmittelbaren Eindruck der Attentate in FR: „Ja, wir sind im Krieg. Und weil wir im Krieg sind, werden wir außergewöhnliche Maßnahmen ergreifen. Wir werden handeln, wir werden diesen Feind angreifen, um ihn zu zerstören, in Frankreich und in Europa, um die Personen, die diese Anschläge begangen haben, zu ergreifen. Aber auch, wie Sie wissen, in Syrien und im Irak und wir werden diese Attacke ebenbürtig beantworten.” Herrje, dann bringen Sie es doch auch so zu Ende.

Warum verstecken Sie sich hinter Strauß und Jünger oder Nolte? Welche realpolitischen Ambitionen haben Sie in Zukunft? Und wo? Warum distanzieren Sie sich nicht von Björn Höcke? Oder anders, was macht dieser Björn Höcke überhaupt richtig? Sie sprechen von der “Aushärtung einer Betondecke” in unserem Land, vom “Gerinnen der Zeit”, von Kehrtwende”, einem “ehernen Gang jeder deutschen Debatte ” und “Richtungswechsel”- Mensch, wie viel Deutsch-Pathos braucht es eigentlich noch und welche innere Armee soll damit reaktiviert werden? Überall um sie herum nur “Gesellschaftsklempner und Meinungsmacher” – eine Ihnen feindlich gesinnte Welt, die Sie in die Düsternis Schnellrodas getrieben hat. Sie ergreifen Partei sogar noch für die Indentitären, Sie trauern dieser identitären Chimäre nach, die schon so ungeschickt ihre Symbolik platziert – dieses gelbe Lamda, nein, kein Hakenkreuz, aber auch irgend so ein Gekreuze noch dazu im Kreisrund – das so viel mehr raunt, als das es eigentlich schon erklärt. Und warum identitär, wo es doch viel einfacher wäre gleich völkisch zu sagen? Also Herr Kubitschek, wie viele Handschuhe soll ich Ihnen noch hinwerfen, nur damit Sie mich immer nur weiter auffordern nachzulegen. Sie sind dran.

KUBITSCHEK: Sie sind nun dort angekommen, wo ich Sie hinstreben sah – Sie äußern sich angegriffen, undifferenziert, benutzen Versatzstücke, wollen »der Einfachheit halber« auf Belege für Ihre Vorhaltungen verzichten und lieber bloß Ihren Eindruck spiegeln. Das ist aber, mit Verlaub, Ihres Intellekts nicht würdig, denn es ist nichts weiter als die Unfähigkeit, die emotionale Hürde zu übersteigen, die Sie von mir/uns trennt. Ihre Emotionalität verhindert, daß Sie die Auffächerung auf der konservativen/ rechten Seite wahrnehmen. Ich geh das der Reihe nach durch:

+ Ich mache das, was ich tue, nicht für Sie – und in gewissem Sinne noch nicht einmal für mich. Sie und ich – wir sind begabt und vor allem frei genug, stets einen Weg für uns und unsere Familien zu finden und zu gehen, der im hohen Maße selbstbestimmt ist. Aber sehr, sehr viele, sehr fleißige und gute Leute können nicht einfach gehen, wenn sie dort, wo sie sind, zu Fremden im eigenen Land werden oder wenn die Schule mit ihren Kindern Experimente macht, gegen die sie sich nicht wehren können (Frühsexualisierung, Geschichtsklitterung, politische Instrumentalisierung). Meine Überzeugung lautet, daß man mit der sehr breiten klein- und bildungsbürgerlichen Mittelschicht sehr, sehr behutsam und sorgsam umgehen muß, denn es ist nicht schwer, die Eselsgeduld dieser Leute auf ganz dreckige Weise auszunutzen, sie permanent gesellschaftlich zu überfordern – und dann über sie zu schimpfen und zu lachen, wenn sie nicht mehr mitmachen wollen (siehe die frühe Pegida, siehe das AfD-Wählerpotential).

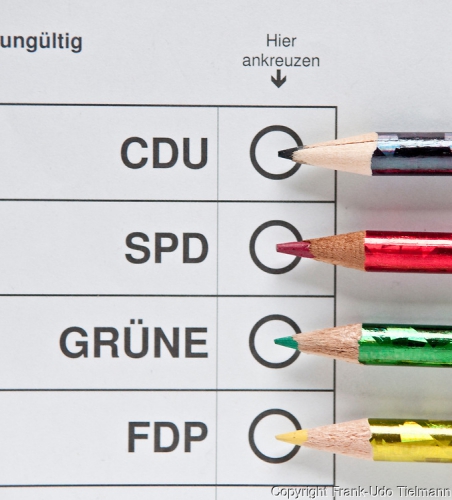

+ Zu unserem Parteiensystem: Lesen Sie das Böckenförde-Diktum. In meinen Worten: Alle Liberalität ruht auf den Schultern wohlerzogener, verantwortungsbewußter, mit sich selbst strenger Bürger, nicht auf denen von Schweinchen Schlau. Die nicht-zynische, nicht bloß schlaue Dienstbereitschaft für diesen Staat zu erhalten und zu fördern – das ist einer meiner Antriebe. Lesen Sie meinen Aufsatz »Der Wahlpreuße« (abgedruckt in meinem neuen Buch: »Die Spurbreite des schmalen Grats«) – mehr habe ich dazu nicht zu sagen. Daß unser guter Staat einen Beutewert hat und daß die Parteien Beute machen, das halte ich für mehr als leicht nachweisbar, und natürlich: nicht nur die Parteien. Meine Forderung übrigens: kein Beamter (Staatsdiener mit Neutralitätspflicht) dürfte, hätte ich etwas zu sagen, einer Partei angehören. Entweder man dient dem Staat oder einer Partei. Beides zugleich geht nicht. Und außerdem: Es gibt ungefähr anderthalb Millionen Beamte zuviel.

+ Zu Seehofer habe ich keine Meinung außer der, daß es sich bei ihm um eine besonders bayrische Wetterfahne handelt.

+ Zum reaktionären, völkischen Sound will ich bitte wirklich ein paar Belegstellen lesen, wo klinge ich denn so? Bloß weil ich meine, daß es die Deutschen und die Nicht-Deutschen gibt? Daß nicht jeder, der hierherkommt, gleich ein Deutscher ist? Daß es eine deutsche Geschichte gibt, eine spezifisch deutsche Art und Weise, die Dinge anzupacken? Daß wir Deutschen ein auf manchen Feldern sehr begabtes, auf anderen unbegabtes Volk sind? Kommen Sie mir jetzt nicht mit den idiotischen Gegenbeispielen, ich meine nie einen festgezurrten, klaren Volkscharakter, sondern wahrnehmbare Tendenzen, die sich niederschlagen in Gesetzen, Strukturen, Verhaltensmustern usf, ausfransend an den Rändern usf., aber dennoch beschreibbar.

+ Und Valls: Ich kenne sein Zitat noch nicht einmal, halten Sie mich für so unoriginell? Mein Handeln wird entlang folgender Maxime laufen, die wiederum nur eine Variante des Böckenförde-Satzes ist: Man muß manchmal die Ruhe stören, um die Ordnung zu bewahren.

+ Ich verstecke mich nicht hinter Strauß, Nolte usf., sondern nehme sie ernst.

+ Realpolitisches habe ich nicht zu formulieren, ich bin kein Politiker. Wäre ich einer, würde ich vielleicht folgendes verfolgen: Sofortiger Aufbau einer Grenzsicherung, die diesen Namen verdient; Weg mit der Übermacht der alteingesessenen Parteien, frischer Wind in die Parlamente, in die Presselandschaft, und: als neue Partei Bewegungspartei bleiben, solange es irgend geht; Weg mit den Gesellschaftsexperimenten, die stets von Leuten in Gang gesetzt werden, die – nach dem Scheitern – einen Plan B für sich persönlich aus der Tasche ziehen; dann die Entscheidung: entweder Einwanderungsgesellschaft oder Sozialstaat – beides zusammen geht nicht, da reicht ein Blick auf Kanada, die USA oder Australien. Mein Votum: ozialstaat; dann: Entschleunigung aller Prozesse, keinesfalls eine weitere Verdinglichung des Menschen; Schutz unseres alternden Volkes vor jedweder Überforderung – aber gut, das alles ist wohl wenig Realpolitik, womit wir wieder am Anfang wären: Ich lese Sloterdijk, nicht Seehofer …

+ Höcke: Wieso sollte ich mich von ihm distanzieren? Weil Sie das für notwendig halten? Erstens macht das seine mächtige Parteifreundin dauernd, zweitens kenne ich ihn viel, viel besser als Sie, drittens ist diesem Mann nicht ein Gran von dem vorzuwerfen, was einem Fischer, Kretschmar oder Tritin vorzuwerfen wäre, also wirklich: kein Gran.

+ Ich sah als Student, Soldat, sehe als Vater, Verleger und mündiger Bürger in der Tat sehr viele Ich-Typen, die entlang einer vom Normalbürger absurd weit entfernten Ideologie an der Gesellschaft herumklempnern (auf meine Kosten, mit meinem Steuergeld) oder als öffentlich-rechtlich finanzierte Meinungsmacher so dermaßen krass gegen eine Partei oder einzelne Leute schießen, daß ich das schon für mehr als bedenklich halte. In solchen Milieus wollte ich nie arbeiten. Schnellroda? Ein tolles Dorf, hell, trocken, fruchtbarer Boden, Ruhe. Keine Düsternis, nur etwas dunklere Räume als das, was Sie aus dem IKEA-Katalog kennen.

+ Die Identitären: Das sind Leute, die noch an etwas leiden können, denen noch etwas weh tut, die genau wissen, daß man nicht alles managen kann und daß diejenigen, die das behaupten, fast ausschließlich dort wohnen, wo man nur mit sehr viel Geld wohnen kann.

+ Noch einmal völkisch? Was soll das sein, bezogen auf mich, was meinen Sie damit? Das will ich wissen, bevor ich den Kopf schüttle.

Kurzum: Ich meine, daß ich mich nicht rechtfertigen muß, denn ich wollte dieses Land nie auf den Kopf stellen. Aber der kalte Staatsstreich von oben ist nunmal eine Realität, die auch auf rolandtichy.de schon recht oft mit deutlichen Worten konstatiert wurde, und die Frage lautet: Läßt man sich das gefallen? Ich meine das ganz prinzipiell: Läßt man es sich gefallen, daß die Regierung einfach so handelt, einfach geltende Gesetze brachial bricht, ignoriert, außer Kraft setzt, und den Souverän (das Volk) damit in zwei-, dreifacher Hinsicht überfährt? Ich meine: nein.

Abschluß: Ihr vereinfachendes »Spiegeln« eines Eindrucks reicht nicht hin. Ich hätte wirklich gern Textstellen, Redepassagen, Äußerungen, an denen Sie Ihren Eindruck festzumachen wüßten. So ein bißchen über Gefühle reden: Das reicht angesichts des Veröffentlichungsort unseres kurzen Dialogs nicht aus.

WALLASCH: Wo sehen Sie “krasse Anwürfe?” Aber was anderes: Sie erinnern mich hier an diese dogmatischen Hardcore-Linken der 1970er. Da waren viele hochintelligent: Aber auch die, wie Sie es nennen “klein- und bildungsbürgerlichen Mittelschicht”, die wie Sie glauben ausgestattet sind nur mit einer “Eselsgeduld”, die auf so “ganz dreckige Weise ausgenutzt und permanent gesellschaftlich” überfordert wurden, diese also Dummies wussten instinktiv, dass die Forderungen dieser linksradikalen Anführer nur Ergebnis eines intellektuellen Supergaus waren – ein ideologisch-evolutionärer Überschlag von Schlauheit zum Dada. Da machten diese “Leute”, denen ich im Übrigen wesentlich mehr zutraue als Sie, einfach dicht. Nennen Sie es Schwarmsicherheit, instinktsicheren Selbstschutz, was auch immer. Der Selbst-Automatismus, der sie übrigens auch gegenüber Merkels “Wir schaffen das” dicht machen lässt. Das rückt mich nun nicht näher zu Ihnen, aber das rückt einen Götz Kubitschek dann näher zusammen mit Merkel, als ihm lieb sein kann.

Oder nein, Sie erinnern mich dann auch wieder an diese bundesrepublikanische Rechte der 1970er und 80er Jahre, die sich damals noch so verschämt in schmuddeligen Heidehöfen traf. Damals, als Karlheinz Weißmann noch im Krebsgang wirkte. Als man Alain de Benoist noch mit glutroten Wangen unterm Tisch las, Julius Evola und diese vielen Widerkehrer und düsteren Geister die das alles unterfütterten, was bei ihnen nun so expressiv erscheint. Viele damals verfingen in der eigenen Ideologie. Ausgestattet mit Publikationen in Kleinstauflage, wie Blaupausen ihres inflationären Denkkonstrukts, bestückt mit Versatzstücken – na klar: – von “Ernst Jünger, Arnold Gehlen, Konrad Lorenz, Carl Schmitt, Martin Heidegger, Ernst Nolte, Armin Mohler”. Sie haben da womöglich ein schwerwiegendes – ein zu schweres! – Erbe angenommen.

Und Sie wollen es ja immer noch: “ein anderes Deutschland”. Sie erklären, Ihnen ginge es darum, “neue Begriffe” und “Deutungen” zu platzieren, heimlich zu tun, bei zu tun, drein zu geben. Aber was ist daran neu, – selber Text – von einem “Gespür für den Ton von morgen” zu sprechen? Dieser Deutschland-erwache-Sound ist sogar der Fingerprint all dieser radikalen Rechten – und in ganz anderem Gewande sogar der linken Bewegungen.

Sie wollen ein “Gegenmilleu” aufbauen? Insistieren, organisieren, Bestehendes destabilisieren? Das alles ist alles andere als neu, nicht der revolutionäre Gestus, nicht dieser Exzellenz-Gedanke des – ach je: – Revolutionärs. Es ist der Mief von Gestern. Und Sie schreiben, das “Kippen bedeutet: etwas ahnen, etwas wittern, zu den ersten gehören wollen, die Schnauze voll haben.” Ich sage Ihnen: Bei Ihnen habe viele mehr als nur eine Ahnung, mehr als nur eine schlimme Vorahnung. Jeder einzelne Ihrer Texte, einen habe ich Ihnen gerade hingeworfen, verstärkt diese Ahnung hin zu einer Gewissheit. Und dann schlussfolgern Sie in Ihrem aktuellsten Text auf Sezessionen ganz richtig: “…daß kein Formungsversuch unsererseits den ehernen Gang jeder deutschen Debatte auch nur um eine einzige Aushärtungsstufe vermindert hat.” Sie ahnen also bereits selbst, dass sie sich hoffnungslos verritten haben, als sie den Weißmann-Krebsgang der 1980er auf dem viel zu breiten Rücken der Zuwanderungskrise nun in einen Schweinsgalopp verwandeln wollten.

KUBITSCHEK: Ich ahne, daß Sie ein bißchen herumpoltern müssen, und wenn das Ihre Art ist, einen unbequemen Eindruck zu spiegeln – bitte. Nur möchte ich nicht mit den Hardcore-Linken der 70er-Jahre verglichen werden, denn ich will weder die Gesellschaft neu erfinden, noch juble ich irgendeinem Che oder einem Ho Tschi Min oder einem Mao zu. Ich will auch nicht die Klein- und Mittelbürger dadurch aus ihrer Unterdrückung befreien, daß ich sie von allem emanzipiere, was ihnen lieb und teuer ist und normal vorkommt. Ich halte diese Schichten vielmehr für die respektablen Leistungsträger dieses Landes, und ich will ihnen Mut machen, für ihr weiterhin gutes Leben zu kämpfen, wenn ihnen mittels gesellschaftlicher Experimenteure zugesetzt wird.

Zum Rest: Ihr Problem, nicht meines. Ein anderes Deutschland, ja, klar, und man muß dabei gar nicht an schlimme Dinge denken, sondern vieles im Geiste einfach einmal entlang des gesunden Menschenverstands neu organisieren. Das Gegenmilieu gibt’s übrigens längst, Sie schreiben selbst dafür. Die Zeiten sind eben nicht mehr verschwiemelt oder biedermeierlich oder lahmarschig. Wir befinden uns – wenn Sie sich eine Sanduhr vorstellen – im Trichter auf dem Weg durch die schmale Schleuse. Jetzt wird alles durcheinandergewirbelt, irgendwann wird’s wieder ruhiger. Jetzt ist der Schweinsgalopp dran, Merkel hat zuerst dazu angesetzt, davon galoppiert sie, hinterher! Wir wollen doch wissen, wer Recht behält, oder?

Sloterdijk verbindt dit hiaat ook concrete historische gebeurtenissen vast. Zo heeft in de Franse Revolutie, met haar voorlopige hoogtepunt in de executie van koning Lodewijk XVI op 21 januari 1793, de breuk met alles wat geweest is zijn definitieve manifestatie gevonden.

Sloterdijk verbindt dit hiaat ook concrete historische gebeurtenissen vast. Zo heeft in de Franse Revolutie, met haar voorlopige hoogtepunt in de executie van koning Lodewijk XVI op 21 januari 1793, de breuk met alles wat geweest is zijn definitieve manifestatie gevonden.

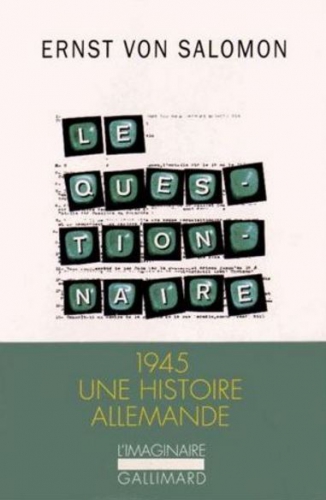

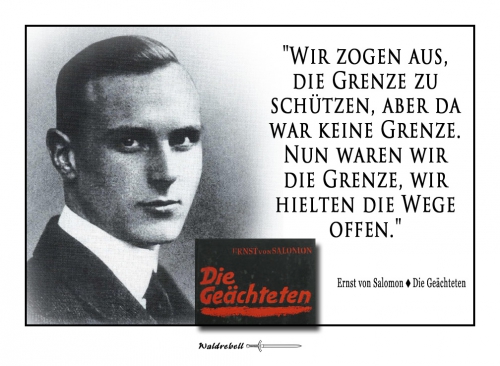

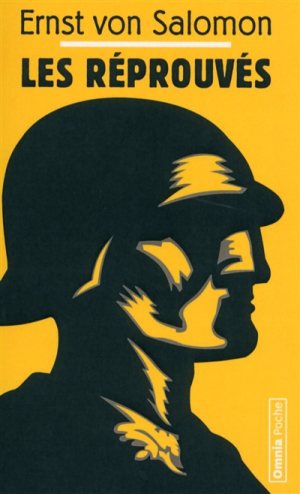

L’architecture générale du livre s’appuie sur les quelques 130 questions auxquelles les Américains demandèrent aux Allemands de répondre en 1945 afin d’organiser la dénazification du pays, mais en les détournant souvent et prenant à de nombreuses reprises le contre-pied des attentes des vainqueurs. A bien des égards, le livre est ainsi non seulement à contre-courant de la doxa habituelle, mais camoufle également bien des aspects d’une réalité que l’Allemagne de la fin des années 1940 refusait de reconnaître : « Ma conscience devenue très sensible me fait craindre de participer à un acte capable, dans ces circonstances incontrôlables, de nuire sur l’ordre de puissances étrangères à un pays et à un peuple dont je suis irrévocablement ». Certaines questions font l’objet de longs développements, mais presque systématiquement un humour grinçant y est présent, comme lorsqu’il s’agit simplement d’indiquer son lieu de naissance : « Je découvre avec étonnement que, grâce à mon lieu de naissance (Kiel), je peux me considérer comme un homme nordique, et l’idée qu’en comparaison avec ma situation les New-Yorkais doivent passer pour des Méridionaux pleins de tempérament m’amuse beaucoup ». Et à la même question, à propos des manifestations des SA dans la ville avant la prise du pouvoir par les nazis : « Certes, la couleur de leurs uniformes était affreuse, mais on ne regarde pas l’habit d’un homme, on regarde son coeur. On ne savait pas au juste ce que ces gens-là voulaient. Du moins semblaient-ils le vouloir avec fermeté … Ils avaient de l’élan, on était bien obligé de le reconnaître, et ils étaient merveilleusement organisés. Voilà ce qu’il nous fallait : élan et organisation ». Au fil des pages, il revient à plusieurs reprises sur son attachement à la Prusse traditionnelle, retrace l’histoire de sa famille, développe ses relations compliquées avec les religions et les Eglises, évoque des liens avec de nombreuses personnes juives (dont sa femme), donne de longues précisions sur ses motivations à l’époque de l’assassinat de Rathenau, sur son procès ultérieur et sur son séjour en prison. Suivant le fil des questions posées, il détaille son éducation, son cursus scolaire, son engagement dans les mouvements subversifs « secrets », retrace ses activités professionnelles successives avec un détachement qui parfois peu surprendre mais correspond à l’humour un peu grinçant qui irrigue le texte, comme lorsqu’il parle de son éditeur et ami Rowohlt. Il revient bien sûr longuement sur les corps francs entre 1919 et 1923, sur l’impossibilité à laquelle il se heurte au début de la Seconde guerre mondiale pour faire accepter son engagement volontaire, tout en racontant qu’il avait obtenu en 1919 la plus haute de ses neuf décorations en ayant rapporté à son commandant… « un pot de crème fraîche. Il avait tellement envie de manger un poulet à la crème ! ». Toujours ce côté décalé, ce deuxième degré que les Américains n’ont probablement pas compris. La première rencontre avec Hitler, le putsch de 1923, la place des élites bavaroises et leurs rapports avec l’armée de von Seeckt, la propagande électorale à la fin des années 1920, et après l’arrivée au pouvoir du NSDAP les actions (et les doutes) des associations d’anciens combattants et de la SA, sont autant de thèmes abordés au fil des pages, toujours en se présentant et en montrant la situation de l’époque avec détachement, presque éloignement, tout en étant semble-t-il hostile sur le fond et désabusé dans la forme. Les propos qu’il tient au sujet de la nuit des longs couteaux sont parfois étonnants, mais finalement « dans ces circonstances, chaque acte est un crime, la seule chose qui nous reste est l’inaction. C’est en tout cas la seule attitude décente ». Ce n’est finalement qu’en 1944 qu’il lui est demandé de prêter serment au Führer dans le cadre de la montée en puissance du Volkssturm, mais « l’homme qui me demandait le serment exigeait de moi que je défende la patrie. Mais je savais que ce même homme jugeait le peuple allemand indigne de survivre à sa défaite ». Conclusion : défendre la patrie « ne pouvait signifier autre chose que de la préserver de la destruction ». Toujours les paradoxes. Dans la dernière partie, le comportement des Américains vainqueurs est souvent présenté de manière négative, évoque les difficultés quotidiennes dans son petit village de haute Bavière : une façon de presque renvoyer dos-à-dos imbécilité nazie et bêtise alliée… et donc de s’exonérer soi-même.

L’architecture générale du livre s’appuie sur les quelques 130 questions auxquelles les Américains demandèrent aux Allemands de répondre en 1945 afin d’organiser la dénazification du pays, mais en les détournant souvent et prenant à de nombreuses reprises le contre-pied des attentes des vainqueurs. A bien des égards, le livre est ainsi non seulement à contre-courant de la doxa habituelle, mais camoufle également bien des aspects d’une réalité que l’Allemagne de la fin des années 1940 refusait de reconnaître : « Ma conscience devenue très sensible me fait craindre de participer à un acte capable, dans ces circonstances incontrôlables, de nuire sur l’ordre de puissances étrangères à un pays et à un peuple dont je suis irrévocablement ». Certaines questions font l’objet de longs développements, mais presque systématiquement un humour grinçant y est présent, comme lorsqu’il s’agit simplement d’indiquer son lieu de naissance : « Je découvre avec étonnement que, grâce à mon lieu de naissance (Kiel), je peux me considérer comme un homme nordique, et l’idée qu’en comparaison avec ma situation les New-Yorkais doivent passer pour des Méridionaux pleins de tempérament m’amuse beaucoup ». Et à la même question, à propos des manifestations des SA dans la ville avant la prise du pouvoir par les nazis : « Certes, la couleur de leurs uniformes était affreuse, mais on ne regarde pas l’habit d’un homme, on regarde son coeur. On ne savait pas au juste ce que ces gens-là voulaient. Du moins semblaient-ils le vouloir avec fermeté … Ils avaient de l’élan, on était bien obligé de le reconnaître, et ils étaient merveilleusement organisés. Voilà ce qu’il nous fallait : élan et organisation ». Au fil des pages, il revient à plusieurs reprises sur son attachement à la Prusse traditionnelle, retrace l’histoire de sa famille, développe ses relations compliquées avec les religions et les Eglises, évoque des liens avec de nombreuses personnes juives (dont sa femme), donne de longues précisions sur ses motivations à l’époque de l’assassinat de Rathenau, sur son procès ultérieur et sur son séjour en prison. Suivant le fil des questions posées, il détaille son éducation, son cursus scolaire, son engagement dans les mouvements subversifs « secrets », retrace ses activités professionnelles successives avec un détachement qui parfois peu surprendre mais correspond à l’humour un peu grinçant qui irrigue le texte, comme lorsqu’il parle de son éditeur et ami Rowohlt. Il revient bien sûr longuement sur les corps francs entre 1919 et 1923, sur l’impossibilité à laquelle il se heurte au début de la Seconde guerre mondiale pour faire accepter son engagement volontaire, tout en racontant qu’il avait obtenu en 1919 la plus haute de ses neuf décorations en ayant rapporté à son commandant… « un pot de crème fraîche. Il avait tellement envie de manger un poulet à la crème ! ». Toujours ce côté décalé, ce deuxième degré que les Américains n’ont probablement pas compris. La première rencontre avec Hitler, le putsch de 1923, la place des élites bavaroises et leurs rapports avec l’armée de von Seeckt, la propagande électorale à la fin des années 1920, et après l’arrivée au pouvoir du NSDAP les actions (et les doutes) des associations d’anciens combattants et de la SA, sont autant de thèmes abordés au fil des pages, toujours en se présentant et en montrant la situation de l’époque avec détachement, presque éloignement, tout en étant semble-t-il hostile sur le fond et désabusé dans la forme. Les propos qu’il tient au sujet de la nuit des longs couteaux sont parfois étonnants, mais finalement « dans ces circonstances, chaque acte est un crime, la seule chose qui nous reste est l’inaction. C’est en tout cas la seule attitude décente ». Ce n’est finalement qu’en 1944 qu’il lui est demandé de prêter serment au Führer dans le cadre de la montée en puissance du Volkssturm, mais « l’homme qui me demandait le serment exigeait de moi que je défende la patrie. Mais je savais que ce même homme jugeait le peuple allemand indigne de survivre à sa défaite ». Conclusion : défendre la patrie « ne pouvait signifier autre chose que de la préserver de la destruction ». Toujours les paradoxes. Dans la dernière partie, le comportement des Américains vainqueurs est souvent présenté de manière négative, évoque les difficultés quotidiennes dans son petit village de haute Bavière : une façon de presque renvoyer dos-à-dos imbécilité nazie et bêtise alliée… et donc de s’exonérer soi-même.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Sinngemäße Aussagen von Zeitgenossen, die aus anderen Parteien nach langer Mitgliedschaft, nach kleinen, mittleren und großen Parteikarrieren ausgetreten sind, gibt es ohne Zahl. Sie sagen im Kern alle: Meine frühere Partei ist

Sinngemäße Aussagen von Zeitgenossen, die aus anderen Parteien nach langer Mitgliedschaft, nach kleinen, mittleren und großen Parteikarrieren ausgetreten sind, gibt es ohne Zahl. Sie sagen im Kern alle: Meine frühere Partei ist  Verwaltungen und Bürokratien allgemein, staatlich wie privat, stellten Studien schon vor...

Verwaltungen und Bürokratien allgemein, staatlich wie privat, stellten Studien schon vor...

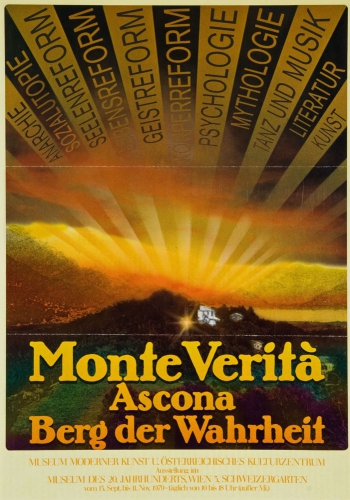

Le choc de la Grande Guerre devait anéantir ses tentatives alternatives, mais d’autres devaient naitre sur les ruines de notre continent. L’expérience révolutionnaire et poétique de Fiume en 1917 sera une autre forme de cette recherche d’une communauté idéale. Mais cela est déjà une autre histoire.

Le choc de la Grande Guerre devait anéantir ses tentatives alternatives, mais d’autres devaient naitre sur les ruines de notre continent. L’expérience révolutionnaire et poétique de Fiume en 1917 sera une autre forme de cette recherche d’une communauté idéale. Mais cela est déjà une autre histoire.

Bad as things are in the US, they are not much better in Europe. The foolish flight of racist Britain from the European Union has deflated its outrageously inflated pound sterling and spread panic among fat cat bankers and property developers. The last rags of Britain’s imperial pretensions have been ripped away.

Bad as things are in the US, they are not much better in Europe. The foolish flight of racist Britain from the European Union has deflated its outrageously inflated pound sterling and spread panic among fat cat bankers and property developers. The last rags of Britain’s imperial pretensions have been ripped away.

Les Réprouvés s’ouvre sur une citation de Franz Schauweker : « Dans la vie, le sang et la connaissance doivent coïncider. Alors surgit l’esprit. » Là est toute la leçon de l’œuvre, qui oppose connaissance et expérience et finit par découvrir que ces deux opposés s’attirent inévitablement. Une question se pose alors : faut-il laisser ces deux attractions s’annuler, se percuter, se détruire et avec elles celui qui les éprouve ; ou bien faut-il résoudre la tension dans la création et la réflexion.

Les Réprouvés s’ouvre sur une citation de Franz Schauweker : « Dans la vie, le sang et la connaissance doivent coïncider. Alors surgit l’esprit. » Là est toute la leçon de l’œuvre, qui oppose connaissance et expérience et finit par découvrir que ces deux opposés s’attirent inévitablement. Une question se pose alors : faut-il laisser ces deux attractions s’annuler, se percuter, se détruire et avec elles celui qui les éprouve ; ou bien faut-il résoudre la tension dans la création et la réflexion.

LINKE / KAMPF GEGEN RECHTS / ANTIFASCHISMUS / RECHTE

LINKE / KAMPF GEGEN RECHTS / ANTIFASCHISMUS / RECHTE

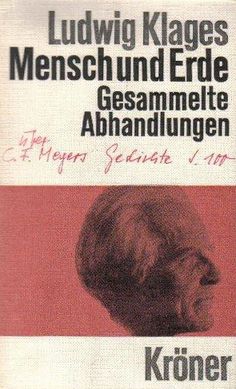

Klages does not think highly of most psychology. It is based on misunderstandings, it has limited possibilities to describe personalities, and it is not a science of the soul. This means that modern psychology and older wisdom about the soul are strangers to each other. Klages does connect to such wisdom. Among other things, he is interested in the psychological insights of folk-language. People are “seeing red”, they get “high” or “carried away”, and become “blue”. Klages is interesting to read when he studies this area.

Klages does not think highly of most psychology. It is based on misunderstandings, it has limited possibilities to describe personalities, and it is not a science of the soul. This means that modern psychology and older wisdom about the soul are strangers to each other. Klages does connect to such wisdom. Among other things, he is interested in the psychological insights of folk-language. People are “seeing red”, they get “high” or “carried away”, and become “blue”. Klages is interesting to read when he studies this area.

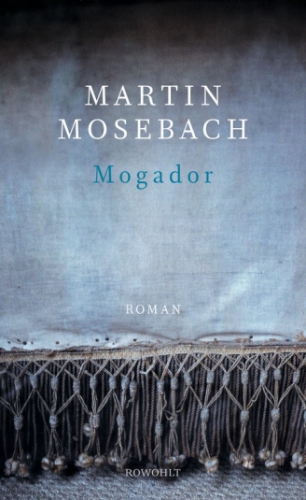

Bücher über die Finanzkrise hat es viele gegeben. Keines warnt so eindringlich vor der Flüchtigkeit des Hier und Jetzt wie Martin Mosebachs „Mogador“. Eine Rezension.

Bücher über die Finanzkrise hat es viele gegeben. Keines warnt so eindringlich vor der Flüchtigkeit des Hier und Jetzt wie Martin Mosebachs „Mogador“. Eine Rezension.

L’empereur Frédéric II est, comme le rappelle à plusieurs reprises l’auteur, l’un des derniers, dans la lignée de Charlemagne, à tenter une restauration (Restitutio) de l’Empire romain. Héritier au deuxième de degré de Frédéric Ier Barberousse, empereur germanique, il est surtout un enfant quand son père Henri VI meurt. En ces premières années du XIIIe siècle, il est donc un enfant placé sous la tutelle de sa mère Constance, qui occupe la régence du royaume de Sicile (incluant alors tout le Sud de l’Italie en plus de la grande île), mais aussi sous celle du pape. Ce dernier souhaite maintenir une suzeraineté sur le royaume de Sicile. En effet, Frédéric est par ses héritages roi de Sicile mais aussi prétendant à la dignité impériale : il peut de jure encercler les villes d’Italie du Nord (logiquement comprise dans un royaume de Pavie devenu fictif depuis le XIIe siècle) et la papauté (appuyant son indépendance sur le fameux faux intitulé « Donation de Constantin »). Voilà donc dès son enfance les forces profondes qui vont s’opposer à son autorité : les bourgeoisies urbaines en plein essor (que ce soit dans les royaumes et fiefs constitutifs de l’Empire, en Germanie notamment, ou en Italie), les grands princes d’Empire (qui ne veulent pas se laisser dicter une centralisation, voire même une hérédité à la dignité impériale) et surtout Rome.

L’empereur Frédéric II est, comme le rappelle à plusieurs reprises l’auteur, l’un des derniers, dans la lignée de Charlemagne, à tenter une restauration (Restitutio) de l’Empire romain. Héritier au deuxième de degré de Frédéric Ier Barberousse, empereur germanique, il est surtout un enfant quand son père Henri VI meurt. En ces premières années du XIIIe siècle, il est donc un enfant placé sous la tutelle de sa mère Constance, qui occupe la régence du royaume de Sicile (incluant alors tout le Sud de l’Italie en plus de la grande île), mais aussi sous celle du pape. Ce dernier souhaite maintenir une suzeraineté sur le royaume de Sicile. En effet, Frédéric est par ses héritages roi de Sicile mais aussi prétendant à la dignité impériale : il peut de jure encercler les villes d’Italie du Nord (logiquement comprise dans un royaume de Pavie devenu fictif depuis le XIIe siècle) et la papauté (appuyant son indépendance sur le fameux faux intitulé « Donation de Constantin »). Voilà donc dès son enfance les forces profondes qui vont s’opposer à son autorité : les bourgeoisies urbaines en plein essor (que ce soit dans les royaumes et fiefs constitutifs de l’Empire, en Germanie notamment, ou en Italie), les grands princes d’Empire (qui ne veulent pas se laisser dicter une centralisation, voire même une hérédité à la dignité impériale) et surtout Rome.

Paradoxalement, enfin, la biographie de ce personnage plus que controversé du Moyen Age est assez détachée des polémiques qui ont ponctué les publications de Sylvain Gouguenheim. En effet l’universitaire avait suscité des clivages particulièrement violents à l’occasion de son Aristote au mont Saint-Michel il y a quelques années. Sur les rapports de Frédéric II au monde arabe, l’auteur semble avancer à pas de loup. Il faut dire qu’il avait fait débat comme l’objet de son livre… Frédéric fut en effet voué aux gémonies par ses contemporains pour avoir obtenu par la négociation et non par le combat la souveraineté sur quelques parcelles des Etats latins perdus quelques années auparavant. Il a en effet obtenu par le traité de Jaffa quelques places, mais rien de bien viable pour maintenir durablement la présence croisée au Levant. Effectivement, les Etats latins ne durèrent pas. Sur les rapports savants, intellectuels qui étaient au cœur de ses précédentes réflexions sur la Renaissance des idées en Occident, l’auteur conclue en s’appuyant sur la faiblesse des sources sur le fait qu’il a pu y avoir influence, mais que celle-ci est difficilement quantifiable. On se reportera au récent ouvrage qui pourra renseigner précisément sur quelques aspects de la Sicile comme plaque tournante des échanges culturels entre Nord et Sud de la Méditerranée (Héritages arabo-islamiques dans l’Europe méditerranéenne), l’auteur se concentrant uniquement sur la ville de Lucera, cas inédit d’une population musulmane concentrée en une ville pouvant demeurer musulmane au cœur même de l’Italie chrétienne.

Paradoxalement, enfin, la biographie de ce personnage plus que controversé du Moyen Age est assez détachée des polémiques qui ont ponctué les publications de Sylvain Gouguenheim. En effet l’universitaire avait suscité des clivages particulièrement violents à l’occasion de son Aristote au mont Saint-Michel il y a quelques années. Sur les rapports de Frédéric II au monde arabe, l’auteur semble avancer à pas de loup. Il faut dire qu’il avait fait débat comme l’objet de son livre… Frédéric fut en effet voué aux gémonies par ses contemporains pour avoir obtenu par la négociation et non par le combat la souveraineté sur quelques parcelles des Etats latins perdus quelques années auparavant. Il a en effet obtenu par le traité de Jaffa quelques places, mais rien de bien viable pour maintenir durablement la présence croisée au Levant. Effectivement, les Etats latins ne durèrent pas. Sur les rapports savants, intellectuels qui étaient au cœur de ses précédentes réflexions sur la Renaissance des idées en Occident, l’auteur conclue en s’appuyant sur la faiblesse des sources sur le fait qu’il a pu y avoir influence, mais que celle-ci est difficilement quantifiable. On se reportera au récent ouvrage qui pourra renseigner précisément sur quelques aspects de la Sicile comme plaque tournante des échanges culturels entre Nord et Sud de la Méditerranée (Héritages arabo-islamiques dans l’Europe méditerranéenne), l’auteur se concentrant uniquement sur la ville de Lucera, cas inédit d’une population musulmane concentrée en une ville pouvant demeurer musulmane au cœur même de l’Italie chrétienne.

Volgens Wimmer is het CDU onder Merkel veranderd in een partij die feitelijk door de agenda van één persoon, de bondskanselier, wordt bepaald, iemand die zich overduidelijk niets aantrekt van de mening van en stemming onder het volk. Merkel oefent inmiddels totale controle over de partij uit, niet alleen in Berlijn, maar in alle onderafdelingen in Duitsland. Bij het geringste openlijke verzet tegen haar zorgt ze ervoor dat deze personen via de achterdeur worden geloosd.

Volgens Wimmer is het CDU onder Merkel veranderd in een partij die feitelijk door de agenda van één persoon, de bondskanselier, wordt bepaald, iemand die zich overduidelijk niets aantrekt van de mening van en stemming onder het volk. Merkel oefent inmiddels totale controle over de partij uit, niet alleen in Berlijn, maar in alle onderafdelingen in Duitsland. Bij het geringste openlijke verzet tegen haar zorgt ze ervoor dat deze personen via de achterdeur worden geloosd.

Qu'est-ce que l'autre tiers-mondisme ? Un tiers-mondisme différent de celui que l'on connaît, c'est à dire « classique, progressiste, qu'il soit chrétien, humanitaire et pacifiste, communiste orthodoxe, trotskiste ou encore d'ultragauche » ? Effectivement. L'autre tiers-mondisme est l'expression par laquelle Philippe Baillet désigne tous ceux que l'on pourrait considérer comme tenants d'un « tiers-mondisme de droite » ou plutôt d'extrême-droite (même quand ceux-ci viennent ou sont d'extrême-gauche, à l'image d'un Soral).

Qu'est-ce que l'autre tiers-mondisme ? Un tiers-mondisme différent de celui que l'on connaît, c'est à dire « classique, progressiste, qu'il soit chrétien, humanitaire et pacifiste, communiste orthodoxe, trotskiste ou encore d'ultragauche » ? Effectivement. L'autre tiers-mondisme est l'expression par laquelle Philippe Baillet désigne tous ceux que l'on pourrait considérer comme tenants d'un « tiers-mondisme de droite » ou plutôt d'extrême-droite (même quand ceux-ci viennent ou sont d'extrême-gauche, à l'image d'un Soral). Rosenberg, quant à lui, « pressent(ait) qu'un jour le flot montant des peuples de couleur pourrait trouver une direction nette et une forme d'unité grâce à l'islam ». La citation suivant, relevée une fois encore par l'auteur, provient du Mythe du Xxe siècle:

Rosenberg, quant à lui, « pressent(ait) qu'un jour le flot montant des peuples de couleur pourrait trouver une direction nette et une forme d'unité grâce à l'islam ». La citation suivant, relevée une fois encore par l'auteur, provient du Mythe du Xxe siècle: Ces dernières années, bien des positions islamophiles liées à tort ou à raison à la droite radicale sont devenues monnaie courante dans ce que Philippe Baillet appelle le « philo-islamisme radical ». Celui-ci est généralement lié à un « sous-marxisme rustique typiquement tiers-mondiste » ou est « emprunt de complotisme à la faveur du développement exponentiel de la « foire aux Illuminés » ». Bien différent du « fascisme comme phénomène européen », ses traits principaux sont : une indifférence plus ou moins marquée envers la « défense de la race blanche », une « véritable passion antijuive » et anti-américaine, une grande hostilité à la finance et au capitalisme, une sympathie pour toutes les causes « anti-impérialistes » et pour l'islam comme religion ou civilisation (l'Islam dans ce cas). Que nous partagions certaines idées de ce courant ne nous en rend pas forcément proche, et je rejoins en cela l'auteur. Celui-ci souligne la diversion effectuée par cette sensibilité chez un grand nombre de personnes qui oublient par ce biais «la priorité absolue» en ce « moment capital de l'histoire de la civilisation européenne »: la perpétuation des peuples européens (de leur partie saine tout du moins). De Roger Garaudy, « illuminé christo-islamo-marxiste » à Carlos et son internationalisme en passant par le chantre de la réconciliation Alain Soral qui « s'inscrit parfaitement (…) dans la vieille tradition des chefaillons et Führer d'opérette chers à la droite radicale française », nombre de figures chères à la frange la plus islamophile de nos mouvances sont ici égratignées par Baillet qui n'a pas son pareil pour souligner leurs contradictions (quand Soral se prétend "national-socialiste français" par exemple)... ou rappeler à notre bon souvenir certaines énormités ou actes pas reluisants. Il souligne ainsi les tentatives d' « islamisation » de la « mouvance nationale » en prenant le cas d'une association telle que celle des « Fils de France » qui se veut un « rassemblement de musulmans français patriotes » et qui a reçu, entre autre, le soutien d'Alain de Benoist. Le philo-islamisme de ce dernier se manifeste depuis bien longtemps. Baillet rapporte d'ailleurs plusieurs citations de celui qu'il qualifie de « toutologue » à ce sujet! Plus ou moins récentes, elles permettent de mieux comprendre le personnage (voir plus haut)... Autant dire qu'on ne peut qu'aller dans le sens de Baillet lorsqu'il argue de l'étendue et de la diversité du « parti islamophile » en France. « Ce n'est pas du tout rassurant », en effet ! Le « parti islamophile » est bien enraciné et doit être combattu « sans faiblesse » partout où il se trouve. Un peu d'espoir cependant :

Ces dernières années, bien des positions islamophiles liées à tort ou à raison à la droite radicale sont devenues monnaie courante dans ce que Philippe Baillet appelle le « philo-islamisme radical ». Celui-ci est généralement lié à un « sous-marxisme rustique typiquement tiers-mondiste » ou est « emprunt de complotisme à la faveur du développement exponentiel de la « foire aux Illuminés » ». Bien différent du « fascisme comme phénomène européen », ses traits principaux sont : une indifférence plus ou moins marquée envers la « défense de la race blanche », une « véritable passion antijuive » et anti-américaine, une grande hostilité à la finance et au capitalisme, une sympathie pour toutes les causes « anti-impérialistes » et pour l'islam comme religion ou civilisation (l'Islam dans ce cas). Que nous partagions certaines idées de ce courant ne nous en rend pas forcément proche, et je rejoins en cela l'auteur. Celui-ci souligne la diversion effectuée par cette sensibilité chez un grand nombre de personnes qui oublient par ce biais «la priorité absolue» en ce « moment capital de l'histoire de la civilisation européenne »: la perpétuation des peuples européens (de leur partie saine tout du moins). De Roger Garaudy, « illuminé christo-islamo-marxiste » à Carlos et son internationalisme en passant par le chantre de la réconciliation Alain Soral qui « s'inscrit parfaitement (…) dans la vieille tradition des chefaillons et Führer d'opérette chers à la droite radicale française », nombre de figures chères à la frange la plus islamophile de nos mouvances sont ici égratignées par Baillet qui n'a pas son pareil pour souligner leurs contradictions (quand Soral se prétend "national-socialiste français" par exemple)... ou rappeler à notre bon souvenir certaines énormités ou actes pas reluisants. Il souligne ainsi les tentatives d' « islamisation » de la « mouvance nationale » en prenant le cas d'une association telle que celle des « Fils de France » qui se veut un « rassemblement de musulmans français patriotes » et qui a reçu, entre autre, le soutien d'Alain de Benoist. Le philo-islamisme de ce dernier se manifeste depuis bien longtemps. Baillet rapporte d'ailleurs plusieurs citations de celui qu'il qualifie de « toutologue » à ce sujet! Plus ou moins récentes, elles permettent de mieux comprendre le personnage (voir plus haut)... Autant dire qu'on ne peut qu'aller dans le sens de Baillet lorsqu'il argue de l'étendue et de la diversité du « parti islamophile » en France. « Ce n'est pas du tout rassurant », en effet ! Le « parti islamophile » est bien enraciné et doit être combattu « sans faiblesse » partout où il se trouve. Un peu d'espoir cependant :