AUßENPOLITISCHES

Teilnehmerliste Bilderbergertreffen 2016 in Dresden

Großzügige Spenden, dubiose Firmen

Wie die "Panama Papers" Clinton schaden

Die "Panama Papiere" bringen Hillary Clinton in Bedrängnis: Wieso sind dort so viele Unternehmer zu finden, die dem Polit-Paar Clinton nahe stehen oder standen? Einmal mehr muss die Präsidentschaftsbewerberin ihr Verhältnis zum großen Geld erklären.

(Drohung eines Großinvestors)

George Soros sagt Russlands Rückkehr als Supermacht voraus

Kühne Prognose von Starinvestor George Soros: Er sieht Russland auf dem besten Weg zurück zur Supermacht. Der Grund für dieses Comeback liege im bevorstehenden Kollaps der Europäischen Union.

Brexit

Farage: Die EU versagt, die EU stirbt

Der Hegemon zeigt sich beleidigt.

Brexit: Die Zeit der Sonnenkönige ist vorbei

Manipulationsverdacht gegen Anti-Brexit-Petition

Wegen Brexit

Tschechien fordert Rücktritt von Jean-Claude Juncker

Brexit

Frankreichs Präsident Hollande will die Briten bluten lassen

(Brexit wird zum Rassismusproblem hochgeschrieben)

Polen in Großbritannien

Frust, Unsicherheit und Angst: Nach dem Brexit-Votum blicken hunderttausende polnische Migranten in Großbritannien in eine ungewisse Zukunft. Die ersten Folgen des Referendums spüren die Polen schon jetzt.

(gleicher Tenor)

Nach dem BrexitRassismus-Welle überspült Großbritannien

Brexit: Christoph Waltz attackiert Briten und Cameron

Die große Macht der „kleinen Leute“

Der Brexit steht beispielhaft für den Aufstand von Abgehängten, die sich mit ihren Ängsten und Vorstellungen im öffentlichen Leben nicht mehr wieder zu finden glauben. Die Jungen zeigen sich schockiert, nachdem sie die Alten über ihre eigene Zukunft entscheiden ließen. Und der politische Betrieb rollt weiter in den vertrauten Ritualen.

Wir nehmen Merkel beim Wort!

Vor dem Hintergrund des Brexit ist es Zeit, Kanzlerin Merkel mal beim Wort zu nehmen und all ihre Aussagen zu Europa zu entlarven. Das Ergebnis ist erstaunlich!

Kommentar zu Jean-Claude Juncker

Der Kapitän auf dem Narrenschiff

von Michael Paulwitz

Noch ein BREXIT – Labour löst sich auf

Jeremy Corbyn schlägt zurück

EU in Krise

Gauck warnt vor nationalistischen Bewegungen in Europa

(Und weiter wird nach Gutsherrenart regiert…)

Freihandelsabkommen: EU will Ceta ohne nationale Parlamente ratifizieren

Die EU-Kommission will das Freihandelsabkommen mit Kanada schnell und an den Parlamenten vorbei beschließen. Sie fürchtet nationale Blockaden.

Philosoph Michel Onfray zu RT: „Frankreich ist in einer Patt-Situation und kurz vor dem Bürgerkrieg“

Österreich

Ergebnis der Präsidentenwahl zunehmend unsicher

Schweizer lehnen bedingungsloses Grundeinkommen ab

Rot-grüne Regierung: Schweden verschärft Asylrecht

US-General traut Nato Baltikum-Verteidigung nicht zu

Schwache Schutzmacht: Der Befehlshaber der US-Landstreitkräfte in Europa, Ben Hodges, übt scharfe Kritik an der Nato. Sollte Russland das Baltikum angreifen, sei die Nato zu langsam zur Verteidigung.

Zeitung: Deutschland für Istanbul-Anschlag verantwortlich

Verbotene Homosexuellen-Kundgebung

Volker Beck in Istanbul abgeführt - Deutsche festgenommen

Katar

Niederländerin nach Vergewaltigungs-Anzeige zu Haftstrafe verurteilt

Aus für Ü-Ei und Happy Meal: Chile verbietet Beigabe von Spielzeug zu Speisen

INNENPOLITISCHES / GESELLSCHAFT / VERGANGENHEITSPOLITIK

Parlamentarismus

Landvögte halten die Lage ruhig

von Paul Rosen

Gauck-Nachfolge

Fast 70 Prozent für Direktwahl des Bundespräsidenten

Beschimpfungen und Buh-Rufe gegen Joachim Gauck in Sebnitz

Empfang vom Stasi-Gauk-ler in Sebnitz.

Bundespräsident Gauck in Sebnitz beschimpft

(Mehr staatliche Hilfe für "Flüchtlinge"…)

NRW plant 700 Millionen Euro mehr für Flüchtlinge

(…aber keine staatliche Hilfe für Einheimische)

Unwetterschäden

Keine Unterstützung vom Land NRW für Hochwasser-Geschädigte

"Diskriminierungsfreie Eidesformel"

NRW-Kabinett schwört künftig nicht mehr auf das deutsche Volk

Eidesforme

NRW-Minister schwören nicht mehr auf das „deutsche Volk“

Bundeswehr bildete Islamisten an der Waffe aus

Erst die Waffenausbildung, dann zum IS: Der Wehrbeauftragte sieht Islamismus bei der Armee als "reale Gefahr". 29 Ex-Soldaten sind nach Syrien ausgereist. Auffällig sind vor allem zwei Dienstgrade.

Umweltschutz-Streit: Koalition will Fracking-Gesetz am Freitag durchdrücken

Bundestag macht Weg frei für Fracking

Über ein Jahr lang stritten Union und SPD über ein Gesetz zum Fracking. Nun hat sich überraschend ein Kompromiss gefunden – der allerdings den Bundesländern den Schwarzen Peter zuschiebt.

Rekord bei der Kirchensteuer

Obwohl es immer weniger Kirchenmitglieder gibt, ist die Summe der Kirchensteuer gestiegen - auf fast 11,5 Milliarden Euro. Die Kirchen profitieren von der guten Konjunktur.

(Etablierte Parteien diskutieren gemeinsam Strategien gegen AfD)

Richtiger Umgang mit der AfD in der Stadtverordnetenversammlung

Reagieren statt ignorieren

„Konservativer Aufbruch“

CSU-Spitze untersagt Auftritt bei AfD: Bendels verläßt Partei

Jörg Meuthen [AfD], Rede im Landtag von Baden-Württemberg am 08.06.2016

Baden-Württemberg

Antisemitismus-Vorwürfe belasten AfD

(Direkte Quelle)

Dr. Wolfgang Gedeon

Fall Gedeon

Nun sag, AfD, wie hast du’s mit dem Judentum?

von Marc Jongen

Der Fall Wolfgang Gedeon – ein Austausch zwischen Marc Jongen und Götz Kubitschek

Interview mit Bayerns AfD-Chef Bystron

„Eigentlich müßte die Regierung vom Verfassungsschutz beobachtet werden“

Kommentar zu Ursula von der Leyen

Feigheit vor dem Feind

von Felix Krautkrämer

Überraschender Wachwechsel in Dülmen

Nach dem Abzug der Briten aus dem Material-Depot "Tower Barracks" in Dülmen soll das Gelände weiter militärisch genutzt werden. US-Streitkräfte werden die Kaserne übernehmen. Das hat der Bund der Stadt Dülmen mitgeteilt und sie damit ziemlich überrascht.

(Das konnte natürlich nicht fehlen…)

Armenier-Genozid: Die deutsche Verantwortung am Völkermord

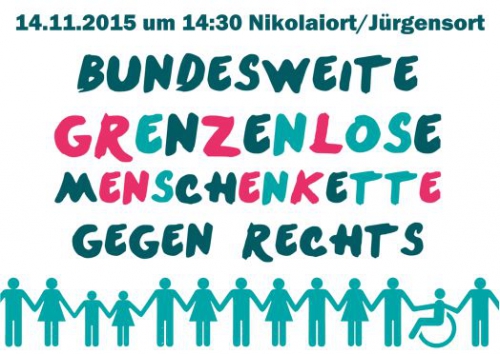

LINKE / KAMPF GEGEN RECHTS / ANTIFASCHISMUS / RECHTE

Die Erde ist eine Scheibe, wenn Nazis sagen, dass sie rund ist

Von Oliver Zimski

Der obsessive „Kampf gegen rechts“ führt zu Selbstverdummung und Politikunfähigkeit

EU-Parlamentspräsident

Schulz fordert neuen Aufstand der Anständigen

Lobbyismus

Wohlfahrtsverband wegen Linksparteinähe in der Kritik

(Gutes Lehrstück in Medienmanipulation)

Europas rechte Hetzer - Rechtsextremisten auf dem Vormarsch

(Zur Rolle des Verfassungsschutzes)

Immer und immer wieder: Divide et impera!

MLPD

Kassel-Rothenditmold

CDU-Politiker wählt Marxisten zum Ortsvorsteher

Rostocker Schüler laden NPD-Politiker zu Geschichtsprojekt ein

Für ein Geschichtsprojekt zum Thema Rechtsextremismus haben Rostocker Schüler einen NPD- und einen AfD-Politiker eingeladen. Die Linkspartei findet das verantwortungslos - der Schulleiter versteht die Kritik nur zum Teil.

(Zur Erinnerung: Broder vs. Butterwegge)

Zweierlei Gewalt - Billigung einer Straftat

(Rüttgers und Leggewie)

Wahrnehmung der Partei

„Halbfaschisten“: Politologe geht auf AfD los

Kardinal Woelki: Christen sollten nicht AfD wählen

„Rassist_Innen im Viertel“

Linksextreme rufen zu Attacken auf AfD-Frau auf

Linksextreme bedrohen Duisburger AfD-Mitglieder

„No AfD“: Gaststätte in Greifswald angegriffen

(Das nächste mal können sie ja mal die Torten den Sozis in ihre Gesichter werfen, damit die etwas mehr Sensibilität lernen ;-))

AfD witterte Torten-Attacke

Landtag streitet über Kuchen

Bei einer AfD-Veranstaltung bringen Demonstranten zwei Schwarzwälder-Kirschtorten mit. Da sie als "Wurfinstrument" missbraucht werden könnten, werden sie kurzerhand von der Polizei beschlagnahmt. Die SPD will das nicht akzeptieren.

(Mal wieder…)

Linksextremismus

Anti-Deutsche rufen zu Flaggen-Klau während der EM auf

"Abscheulich" - Grüne Jugend verurteilt Fahnenschwenken

Patriotismus nein danke! Erklärung der GRÜNEN JUGEND Berlin zum Start der Herrenfußball-Europameisterschaft.

Grüne Jugend: Schwarz-Rot-Gold steht für rechte Demos

Petition

Ja zur Extremismusklausel - Keine Steuergelder für Verfassungsfeinde und Schlägertrupps

Berlin plant Soko gegen Linksextremisten

Polizistenbeleidigung "All Cops Are Bastards" "ACAB" fällt unter Meinungsfreiheit

(Mal wieder ohne politische Konsequenzen)

Gewaltserie

Linksextreme verprügeln Verbindungsstudenten und Begleiterin

(und wieder die Kriminellenhochburg Göttingen)

Gewaltserie

Vermummte attackieren erneut Verbindungsstudenten

Wien

Identitärer Demonstrant liegt nach linken Gewaltexzessen im Koma

Identitärer Aktivist nach Operation aufgewacht - Medien verharmlosen Antifa-Gewalt

(Die Polizei ermittelt wegen Mordversuchs)

Wien – Rudolfsheim Fünfhaus: Mordversuch bei Versammlung

Strassenschlacht in Wien - Analyse zur Demo 2016

EINWANDERUNG / MULTIKULTURELLE GESELLSCHAFT

Von der menschlichen Wärme des Willkommenskultes

Wolfgang Schäuble und die Biopolitik der Auflösung

Kommentar zur katholischen Kirche

Sakrale Flüchtlingsromantik

Videoantwort an Kardinal Woelki · Beatrix von Storch EfD Brüssel AfD

Bundesregierung wünscht Muslimen gesegneten Ramadan

Während der Zuspruch der Rechtspopulisten steigt, wünscht die Bundesregierung "allen muslimischen Mitbürgern einen gesegneten und friedvollen Ramadan". Der islamische Fastenmonat beginnt heute.

Nach Besuch von Asylunterkunft

Grünen-Politiker Palmer: „fordernd, fast schon aggressiv“

Schultheatertage in Frankfurt

Schüler wagen sich an Klassiker

Lehrer stehen mittlerweile am Rande der Verzweiflung

Die Grundschule soll Flüchtlinge integrieren, Zugewanderte fördern und Behinderte inkludieren. Zwischen diesen Aufgaben werden Lehrer zerrieben. Manche Schule weiß sich auf ganz eigene Art zu helfen.

Meine Erfahrungen mit Flüchtlingen in Deutschland 2015 - 2016 Asylbewerbern und Migranten

(ab Minute 8 wird es interessant)

Flüchtlinge erwarten Sportwagen, Häuser und willige deutsche Frauen

Offene Grenzen oder Wohlfahrtsstaat?

Freital: Flüchtlinge müssen Hotel verlassen ein Tag später stehen diese wieder vor dem Hotel

Refugees Welcome – aber nicht bei uns: Linksradikale weigern sich Asylbewerber auzufnehmen

Berlin

„Refugees welcome?“

Polizei schützt Bauarbeiter vor Linken

Video: Grüne sucht Freiwillige, die Asylbewerbern das Essen in den 5. Stock tragen

Helfer frustriert

Asylsuchende nutzen Gratis-W-Lan für Erotik-Videos

Wer heißt die Flüchtlinge willkommen?

Streit um sichere Herkunftsstaaten Hasselfeldt warnt Grüne vor Blockade bei Maghreb-Votum

CSU-Landesgruppenchefin Gerda Hasselfeldt warnt die Grünen davor, die Abstimmung über eine Einstufung von Tunesien, Marokko und Algerien zu blockieren - ein solcher Schritt wäre "unverantwortlich".

Aktuelle “Flüchtlings”-Zahlen: Masseninvasion geht weiter – Medien schweigen

Zahl der Einreisen verdreifacht

Tschetschenen bereiten Behörden Sorgen

Die Schließung der Balkanroute hat nicht dazu geführt, dass die deutsche Ostgrenze unter Druck gerät. Dort lässt sich jedoch ein anderes Phänomen beobachten: Es kommen mehr Tschetschenen an. Für die Behörden aus zwei Gründen besorgniserregend.

Flüchtlingskrise: Italien erwartet „Exodus biblischen Ausmaßes“ aus Afrika

Heiko Maas (SPD) will weitere 6 Mio. Zuwanderer

(Zum Familiennachzug)

Anabel Schunke kündigt

Ich muss gar nix

Wenn der Staat den Gesellschaftsvertrag aufkündigt, indem er seinen Verpflichtungen mir gegenüber nicht mehr nachkommt, mich nicht einmal mehr zu schützen vermag, dann kann ich ihm meine Gefolgschaft entziehen. Und das tue ich hiermit.

Muslime in der Bundeswehr: Drei Kameraden erzählen, was sie bewegt

Dass Yasin Chowdury ein schwarz-rot-goldenes Abzeichen trägt, passt vielen nicht. Der junge Mann dient in der Bundeswehr und ist Muslim – so wie 24 Prozent der Soldaten im Landeskommando.

Hunderttausende Ermittlungsverfahren für den Papierkorb

Die Flüchtlingskrise belastet Deutschlands Staatsanwälte mit einem Aktenberg Hunderttausender ergebnisloser Ermittlungsverfahren.

Bund stellt 93 Milliarden Euro für Flüchtlinge bereit

Höhe der Kosten noch nicht beziffert

Verträge für Flüchtlingsunterkünfte laufen weiter

(Thema mangelnde Abschiebungen)

Asylkrise

Sisyphos-Arbeit

von Dieter Amann

Für die Freiheit, gegen den Austausch: Klaus & Sarrazin in Berlin

Selbstbestimmung

Ausländerstopp: Empörung über Kleingartenverein (in Wittenberg)

Studie

Die Islamfeindlichkeit in Deutschland wächst

Gegen Muslime und andere Minderheiten: Eine neue Studie zeigt rechtsextreme und autoritäre Einstellungen in Deutschland. Besonders verbreitet sind sie unter AfD-Wählern.

Moscheebau

Stadt schenkt Grundstück an Islamverbände

Monheim

Moscheebau

Wachsende Kritik an Grundstücksschenkung an Islamverbände

Türkische Gemeinde

Streit um Aleviten-Denkmal in Berlin

Peinliche Hochwasser-Inszenierung mit Flüchtlingen in der Weststadt

Helle Empörung hat bei vielen Bürgern und Hochwasserhelfern in der immer noch von der Flut gezeichneten Weststadt eine von der Stadtverwaltung auf Bitten eines ausländischen Kamerateams inszenierte „ Hilfsaktion“ von Flüchtlingen ausgelöst. Die Aktion wurde zu einer Satire, wie mehrere Augenzeugen unabhängig voneinander der Rems-Zeitung hilfesuchend — auch im Sinne der offensichtlich „missbrauchten Asylbwerber“ — schilderten.

Verwirrung um syrische Unfallhelfer und verletzten NPD-Funktionär

("Für Flüchtlinge")

111 Stunden Fußball - Weltrekord in Hamburg

Peter Fox

Sänger lebt mit Flüchtlingsfamilie zusammen

Flüchtlingsheim neben Nacktbade-Strand geplant: Geplante Eskalation?

Zahlen für Deutschland

48.000 Frauen wurden 2015 Opfer von Genitalverstümmelung

Was passiert wirklich in den Moscheen?

Dänen geschockt durch Doku-Serie über Imame

Orlando: Angreifer feuert in Schwulenclub - 50 Menschen sterben

Orlando und die Medien: Die steile Karriere einer dummen Frage

Seit gestern höre ich immer wieder die Frage: War Omar Mateen, der Massenmörder von Orlando, islamistisch oder homophob? Oder womöglich sogar beides? Das geht dem religionspolitischen Sprecher der Grünen Volker Beck genauso. Er sagte heute: «Es verwundert etwas, wenn in der Berichterstattung der homophobe Hintergrund der Tat als Alternative zum islamistischen oder terroristischen Hintergrund der Tat diskutiert wird. Die Homophobie ist integraler Bestandteil des Islamismus.»

Ahmad Mansour über Islam und Terror

Der Islam muss sich reformieren

Nach dem Massenmord von Orlando hieß es: Das hat nichts mit dem Islam zu tun. Aber solche Rede geht an der Realität vorbei. Religion kann für Kritik nicht tabu sein. Ahmad Mansour

Facebook sperrt Schwulenportal nach Islamkritik

Ramadan Seligenstadt: „Lasst uns die ungläubigen Christen abschlachten“

Tunesier nach Angriff auf Kellnerin in Nizza während des Ramadan verurteilt

Vorbestrafter Terrorist tötet Polizist und seine Frau nahe Paris

Brand in Düsseldorfer Flüchtlingsheim

Kein Schoko-Pudding! Da fackelte er die Halle ab

Brandstiftung in Flüchtlingsunterkunft

Verdächtiger beging schon 35 Straftaten

Brandanschlag in Vorra

Polizei sieht kein rechtsextremistisches Motiv

Vorra

Hakenkreuze sollten vom wahren Motiv ablenken

Großrazzia Polizei erklärt Teile der Euskirchener City zu „gefährlichen Orten“

(Schon wieder Bad Godesberg)

Bad Godesberg wird zum Problemviertel

Jugendliche entführen und erpressen 12-Jährigen

(na sowas…)

Übergriffe von Köln

Silvester-Täter kamen mit Flüchtlingswelle ins Land

Integrationsprobleme

Einwandererkinder drangsalieren Mitschüler

Ignorantes Geschwätz statt Frauenschutz

Reaktionen von Politikerinnen auf die Darmstädter Übergriffe

(Randalierender Asylbewerber in Sachsen)

„Wir haben Zivilcourage gezeigt“

von Felix Krautkrämer, Henning Hoffgaard

Fall Arnsdorf

CDU-Politiker: Handeln ist besser als wegsehen

von Felix Krautkrämer

(dazu als Nachtrag)

Ermittlungen gegen Görlitzer Polizeipräsidenten eingeleitet

Verdacht auf Volksverhetzung: Berliner Ladenbesitzerin erteilt Roma Hausverbot

Die Besitzerin eines Esoterikladens in Berlin will keine Roma mehr dulden - und hängt ein Verbotsschild an die Tür. Jetzt ermittelt der Staatsschutz.

African refugees attacking Native French

Remscheid

Polizei nimmt Sex-Täter fest

Fahndung in Düsseldorf Wer hat den Grapscher vom Japantag gesehen?

„Antänzer“ in Kassel

Sex-Täter umringen und begrapschen Studentin

Ahrensburg

Erneut sexuelle Gruppenübergriffe auf Stadtfest

Frankfurt

Auch ein Mieterzoff eskaliert

Straßenkampf auf der Zeil mit Machete und Holzstange

Görlitz

Junge Araber und Polen gehen aufeinander los

Wegen häufiger Randale in der Innenstadt bildet die Polizei jetzt eine Ermittlungsgruppe.

(Gebürtiger Tunesier)

Mord wegen Sex-Video: Mann zu 20 Jahren verurteilt

Ein Vater im Zorn: „Dieser Mann hat unser Kind missbraucht – und läuft frei herum“

KULTUR / UMWELT / ZEITGEIST / SONSTIGES

Berichte zum Ponte City Tower in Südafrika, dem einst gefährlichsten Hochhaus der Welt

Harte Zeiten für Anhänger moderner Architektur

Von Berlin bis Duisburg: In Deutschland wird rekonstruiert wie seit der Nachkriegszeit nicht mehr. Überall kehren historische Bauwerke ins Stadtbild zurück. Harte Zeiten für die Moderne.

Stuttgarts Umgang mit Bauwerken

Abriss-Furor und kein Ende in Sicht

Geheime Orte in Berlin

Der Schatz im Kreuzberg

Über dem Viktoriapark thront das Nationaldenkmal Karl Friedrich Schinkels mit Blick über ganz Berlin. Darunter verborgen ist ein Gewölbe, das einer Kathedrale gleicht. Ein Spaziergang durch diese Unterwelt und zu weiteren Spuren alter Zeiten.

Zwei Jahre Haft auf Bewährung für Graffiti-Sprayerei in US-Nationalparks

Paragraphen gegen Windenergie

Bayern stoppt Windkraft-Monster

Windkraft

Verfassungsgericht bestätigt 10H

Rückenwind für Staatsregierung

Der Bayerische Verfassungsgerichtshof hat die Klagen gegen das bayerische Windkraftabstandsgesetz abgewiesen. Damit gilt die umstrittene 10H-Regel als verfassungsgemäß.

Windräder, 200 Meter hoch, am "Märchenschloss"?

Schloss Lichtenstein auf der Schwäbischen Alb ist ein Wahrzeichen Baden-Württembergs. Doch das Idyll ist bedroht: Windkraftanlagen könnten die Sicht zerstören – Bürger und Denkmalschutz protestieren.

(Immerhin haben sie Visionen)

„Klimaschutzplan 2050“

SPD will Klima durch Fleischverzicht retten

Steffen Königer zum Genderwahnsinn. AFD im Landtag

Wege und Sackgassen für Männer: Hannah Lühmann über die eierlose Linke

"Dourower Kearn" singen auf Platt

14 Kinder bereiten sich in der Mundart-Arbeitsgemeinschaft auf den großen Auftritt in Tracht vor

Wetzlar-Dutenhofen

14 Dutenhofener Kinder sind nicht nur sprachlich auf die Suche nach Spuren ihrer Vorfahren gegangen. Die Dritt- und Viertklässler sind Teilnehmer der Mundart-Arbeitsgemeinschaft, die in ihrer Schule angeboten wird.

Streit um Dopingvorwürfe

WDR-Reporter streitet sich mit russischen Journalisten

Nachklapp zu Boateng und Gauland

Eine belanglose Äußerung zum Fußballer-Rührstück aufgebauscht

Streit um Rassismus-Vorwurf

AfD-Vize Gauland: „Das ist eine Meinungsdiktatur“

Boateng-Zitat

Die verlorene Ehre der „FAZ“

von Thorsten Hinz

(Auf diese Idee ist Boateng sicher nicht selbst gekommen…)

Jerome Boateng

DFB-Star fordert, deutschen Wortschatz auf Rassismus zu prüfen

(Die nächste Runde…)

AfD-Chefin Frauke Petry holt gegen Mesut Özil aus

Petry spekuliert über politische Absicht von Özil

Die AfD-Chefin wirft die Frage auf, ob der Nationalspieler mit seinem Facebook-Foto als Mekka-Pilger eine politische Aussage treffen wolle. Die "Grundgesetzwidrigkeit des Islam" ist für sie Tatsache.

(Zu Fußball und AfD)

Die angeblich schönste Nebensache der Welt

Warum sie unsere Hymne nicht singen

Einige Vermutungen zum Auftakt der Fußball-Europameisterschaft

Aus den Feuilletons

"Zur Hölle mit der Hymne!"

Bannerparole statt Flaggenklau

Fußball wird zunehmend ein Feld für politische Instrumentalisierungen

Petition

Französische Intellektuelle sagen radikalem Islam den Kampf an

EKD distanziert sich von Luthers Islam-Kritik

Ramadan

Bundeselternrat rät zu Gebetsräumen und längeren Unterrichtspausen

Warum Schule nicht funktioniert - es ist ein Irrsinn - Das Universelle Verblödungssystem

China : Die härteste Uni-Prüfung der Welt

Millionen Schüler in China machen jedes Jahr den Uni-Test. Der Druck ist extrem, manche greifen zu High-Tech-Schummelhilfen. Prüfer kontrollieren mit Metalldetektoren.

Der Geschichtsvergessenheit entgegen wirken

Eine Empfehlung für das Buch "Deutsche Geschichte für junge Leser"

Das verlorene Vertrauen in die Institutionen

Wachstumskritik (IX): Unsichtbarkeitsspirale

(Der Manipulation Tür und Tor geöffnet…)

Künstliche Intelligenz

Roboter vermehren das Geld

Schon bald könnten Maschinen die besseren Anleger sein. Die ersten Vermögensverwalter experimentieren mit Künstlicher Intelligenz – ist das die Zauberformel für die Geldanlage im 21. Jahrhundert?

Der Trend zum Teilen und Tauschen - 'Sharing' greift um sich

Vom schleichenden Ende der Arbeitsstelle wie wir sie kennen.

Präventivkrieg 1941 – »Deutschland im Visier Stalins«

Münster anno 1534, ein Modell?

Muhammad Ali: Rassist vs. Gutmensch über Multikulti

Andreas Rebers - Die Grünen long version

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Se ci fermiamo un attimo a riflettere su quale sia il gesto che, durante una nostra comune giornata, ripetiamo il maggior numero di volte, riconosceremo presto che si tratta del gesto di guardare l’orologio. Un gesto così scontato, ormai istintivo, che quasi come una funzione fisiologica accompagna la nostra esistenza, che ci appare impossibile immaginare una vita senza orologio. Il tempo, pensiamo giustamente, è il giudice supremo ed impietoso della nostra vita: come potremmo vivere senza misurarlo, senza tenerlo costantemente sotto controllo? E quale strumento migliore che i nostri orologi sempre più precisi e sofisticati?

Se ci fermiamo un attimo a riflettere su quale sia il gesto che, durante una nostra comune giornata, ripetiamo il maggior numero di volte, riconosceremo presto che si tratta del gesto di guardare l’orologio. Un gesto così scontato, ormai istintivo, che quasi come una funzione fisiologica accompagna la nostra esistenza, che ci appare impossibile immaginare una vita senza orologio. Il tempo, pensiamo giustamente, è il giudice supremo ed impietoso della nostra vita: come potremmo vivere senza misurarlo, senza tenerlo costantemente sotto controllo? E quale strumento migliore che i nostri orologi sempre più precisi e sofisticati?

Oberlerchers philosophischer Totalitätsanspruch sollte indessen erst in den folgenden Dekaden ganz hervortreten: Das 1986 vollendete enzyklopädische System der Sozialwissenschaften wurde 1994 in eine sozialphilosophische Lehre vom Gemeinwesen überführt und 2014 von einem holistischen

Oberlerchers philosophischer Totalitätsanspruch sollte indessen erst in den folgenden Dekaden ganz hervortreten: Das 1986 vollendete enzyklopädische System der Sozialwissenschaften wurde 1994 in eine sozialphilosophische Lehre vom Gemeinwesen überführt und 2014 von einem holistischen  In Opposition zu einer gesetzes- und vertragsförmig normierten Weltgesellschaft aus entwurzelten Individuen fordert Oberlercher folgerichtig die rechts- und ordnungsgemäße Wiedereinwurzelung von souveränen Volksgemeinschaften, wie sie nur eine »völkische Weltrevolution« durchsetzen könnte.

In Opposition zu einer gesetzes- und vertragsförmig normierten Weltgesellschaft aus entwurzelten Individuen fordert Oberlercher folgerichtig die rechts- und ordnungsgemäße Wiedereinwurzelung von souveränen Volksgemeinschaften, wie sie nur eine »völkische Weltrevolution« durchsetzen könnte. Mit sicherem Gespür für den würdigen Feind attackierte er den »kafkaesken Professor« Theodor W. Adorno, der in seinen philosophischen Fragmenten einen Angriff auf das deutsche Systemdenken geführt und das »Ganze« zum »Unwahren« erklärt hatte.

Mit sicherem Gespür für den würdigen Feind attackierte er den »kafkaesken Professor« Theodor W. Adorno, der in seinen philosophischen Fragmenten einen Angriff auf das deutsche Systemdenken geführt und das »Ganze« zum »Unwahren« erklärt hatte.

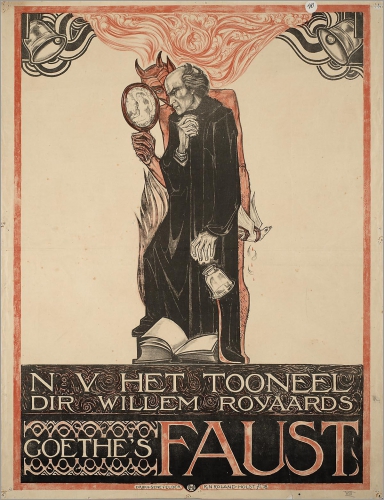

Onze cultuur, de cultuur van het Avondland, ziet Spengler als 'Faustisch', naar het toneelstuk 'Faust' van Goethe. Het idee is dat de mens van onze cultuur streeft naar onbeperkte kennis, zelfs als hij daarvoor – net als Faust – een pact met de duivel moet sluiten. Als poëtisch beeld voor deze cultuur geeft Spengler “de oneindige ruimte”. Het ruimtevaartprogramma zou hij als een typerende cultuuruiting van het Avondland zien.

Onze cultuur, de cultuur van het Avondland, ziet Spengler als 'Faustisch', naar het toneelstuk 'Faust' van Goethe. Het idee is dat de mens van onze cultuur streeft naar onbeperkte kennis, zelfs als hij daarvoor – net als Faust – een pact met de duivel moet sluiten. Als poëtisch beeld voor deze cultuur geeft Spengler “de oneindige ruimte”. Het ruimtevaartprogramma zou hij als een typerende cultuuruiting van het Avondland zien.

Er studierte nach dem Krieg an der Lomonossow-Universität. In 1973 promovierte er als Historiker. Sein beruflicher Weg führte ihn in die russische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Er war zur Zeit der Perestroika Professor der Diplomatischen Akademie des sowjetischen Außenministeriums und Berater von Michael Gorbatschow. Sein großes politisches Ziel war die Entspannung des Ost-West-Problems. Er befürwortete ganz intensiv das Zustandekommen der Wiedervereinigung Deutschlands. Er kämpfte für die Einhaltung der Menschenrechte, befürwortete die Grundsätze einer Demokratie und der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft.

Er studierte nach dem Krieg an der Lomonossow-Universität. In 1973 promovierte er als Historiker. Sein beruflicher Weg führte ihn in die russische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Er war zur Zeit der Perestroika Professor der Diplomatischen Akademie des sowjetischen Außenministeriums und Berater von Michael Gorbatschow. Sein großes politisches Ziel war die Entspannung des Ost-West-Problems. Er befürwortete ganz intensiv das Zustandekommen der Wiedervereinigung Deutschlands. Er kämpfte für die Einhaltung der Menschenrechte, befürwortete die Grundsätze einer Demokratie und der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft.

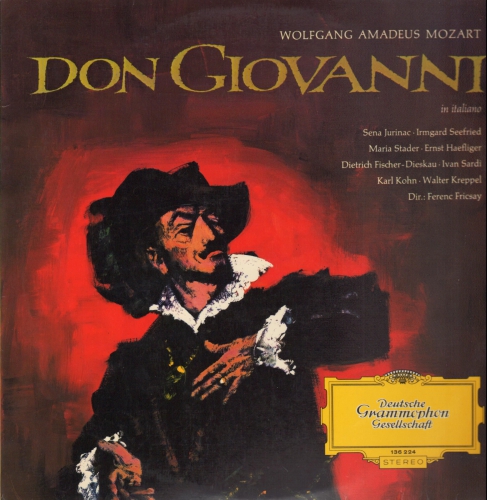

Or, la dernière partie de la phrase vient d’être censurée à Berlin, au Komische Oper qui programme actuellement Don Giovanni. La « Turquie » a été remplacée par la « Perse ». Cette initiative de la direction a été prise pour ne pas offenser la sensibilité des millions de citoyens turcs vivant en Allemagne, mais surtout pour ne pas créer de malentendus diplomatiques avec Erdogan, qui ces derniers mois a exercé de fortes pressions auprès des autorités allemandes et des médias en ce qui concerne l’image de la Turquie dont il convient de ne pas se moquer publiquement.

Or, la dernière partie de la phrase vient d’être censurée à Berlin, au Komische Oper qui programme actuellement Don Giovanni. La « Turquie » a été remplacée par la « Perse ». Cette initiative de la direction a été prise pour ne pas offenser la sensibilité des millions de citoyens turcs vivant en Allemagne, mais surtout pour ne pas créer de malentendus diplomatiques avec Erdogan, qui ces derniers mois a exercé de fortes pressions auprès des autorités allemandes et des médias en ce qui concerne l’image de la Turquie dont il convient de ne pas se moquer publiquement.

According to this matrix, our Caesarism period of 2000-2200 corresponds to 100 BC – 100 AD in Classical civilization. The post-2200 era corresponds to the Roman Empire from Trajan onwards. Here civilization has attained its peak, while cultural forms are completed, calcified, past evolution. This, you might say, is the true End of History—for our Western, Faustian civilization at least. But we have a way to go.

According to this matrix, our Caesarism period of 2000-2200 corresponds to 100 BC – 100 AD in Classical civilization. The post-2200 era corresponds to the Roman Empire from Trajan onwards. Here civilization has attained its peak, while cultural forms are completed, calcified, past evolution. This, you might say, is the true End of History—for our Western, Faustian civilization at least. But we have a way to go. Anyway, when Time reviewed Man and Technics a few years later, the bloom was off the rose. In an about-face from 1926, Time now declared Spengler a pessimist, one who thinks Civilization is done for. This time around, the reviewer dismissed his work with lip-smacking sarcasm:

Anyway, when Time reviewed Man and Technics a few years later, the bloom was off the rose. In an about-face from 1926, Time now declared Spengler a pessimist, one who thinks Civilization is done for. This time around, the reviewer dismissed his work with lip-smacking sarcasm:

Here is where German intellectuals come into the story. Journalists and academics have had a hard time understanding why the Pegida movement emerged when it did and why it has attracted so many people in Germany; there are branches of the Pegida movement in other parts of Europe, but they have gathered only marginal support thus far. Those who suggest it is driven by “anger” and “resentment” are being descriptive at best. What is remarkable, though, is that “rage” as a political stance has received the philosophical blessing of the leading AfD intellectual, Marc Jongen, who is a former assistant of the well-known philosopher Peter Sloterdijk. Jongen has not only warned about the danger of Germany’s “cultural self-annihilation”; he has also argued that, because of the cold war and the security umbrella provided by the US, Germans have been forgetful about the importance of the military, the police, warrior virtues—and, more generally, what the ancient Greeks called thymos (variously translated as spiritedness, pride, righteous indignation, a sense of what is one’s own, or rage), in contrast to eros and logos, love and reason. Germany, Jongen says, is currently “undersupplied” with thymos. Only the Japanese have even less of it—presumably because they also lived through postwar pacifism. According to Jongen, Japan can afford such a shortage, because its inhabitants are not confronted with the “strong natures” of immigrants. It follows that the angry demonstrators are doing a damn good thing by helping to fire up thymos in German society.

Here is where German intellectuals come into the story. Journalists and academics have had a hard time understanding why the Pegida movement emerged when it did and why it has attracted so many people in Germany; there are branches of the Pegida movement in other parts of Europe, but they have gathered only marginal support thus far. Those who suggest it is driven by “anger” and “resentment” are being descriptive at best. What is remarkable, though, is that “rage” as a political stance has received the philosophical blessing of the leading AfD intellectual, Marc Jongen, who is a former assistant of the well-known philosopher Peter Sloterdijk. Jongen has not only warned about the danger of Germany’s “cultural self-annihilation”; he has also argued that, because of the cold war and the security umbrella provided by the US, Germans have been forgetful about the importance of the military, the police, warrior virtues—and, more generally, what the ancient Greeks called thymos (variously translated as spiritedness, pride, righteous indignation, a sense of what is one’s own, or rage), in contrast to eros and logos, love and reason. Germany, Jongen says, is currently “undersupplied” with thymos. Only the Japanese have even less of it—presumably because they also lived through postwar pacifism. According to Jongen, Japan can afford such a shortage, because its inhabitants are not confronted with the “strong natures” of immigrants. It follows that the angry demonstrators are doing a damn good thing by helping to fire up thymos in German society. Like in Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality—a continuous inspiration for Sloterdijk—these re-descriptions are supposed to jolt readers out of conventional understandings of the present. However, not much of his work lives up to Nietzsche’s image of the philosopher as a “doctor of culture” who might end up giving the patient an unpleasant or outright shocking diagnosis: Sloterdijk often simply reads back to the German mainstream what it is already thinking, just sounding much deeper because of the ingenuous metaphors and analogies, cute anachronisms, and cascading neologisms that are typical of his highly mannered style.

Like in Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality—a continuous inspiration for Sloterdijk—these re-descriptions are supposed to jolt readers out of conventional understandings of the present. However, not much of his work lives up to Nietzsche’s image of the philosopher as a “doctor of culture” who might end up giving the patient an unpleasant or outright shocking diagnosis: Sloterdijk often simply reads back to the German mainstream what it is already thinking, just sounding much deeper because of the ingenuous metaphors and analogies, cute anachronisms, and cascading neologisms that are typical of his highly mannered style.  Sloterdijk is not the only prominent cultural figure who willfully reinforces a sense of Germans as helpless victims who are being “overrun” and who might eventually face “extinction.” The writer Botho Strauβ recently published an essay titled “The Last German,” in which he declared that he would rather be part of a dying people than one that for “predominantly economic-demographic reasons is mixed with alien peoples, and thereby rejuvenated.” He feels that the national heritage “from Herder to Musil” has already been lost, and yet hopes that Muslims might teach Germans a lesson about what it means to follow a tradition—because Muslims know how to submit properly to their heritage. In fact, Strauβ, who cultivates the image of a recluse in rural East Germany, goes so far as to speculate that only if the German Volk become a minority in their own country will they be able to rediscover and assert their identity.

Sloterdijk is not the only prominent cultural figure who willfully reinforces a sense of Germans as helpless victims who are being “overrun” and who might eventually face “extinction.” The writer Botho Strauβ recently published an essay titled “The Last German,” in which he declared that he would rather be part of a dying people than one that for “predominantly economic-demographic reasons is mixed with alien peoples, and thereby rejuvenated.” He feels that the national heritage “from Herder to Musil” has already been lost, and yet hopes that Muslims might teach Germans a lesson about what it means to follow a tradition—because Muslims know how to submit properly to their heritage. In fact, Strauβ, who cultivates the image of a recluse in rural East Germany, goes so far as to speculate that only if the German Volk become a minority in their own country will they be able to rediscover and assert their identity.  Like at least some radicals in the late Sixties, the new right-wing “avant-garde” finds the present moment not just one of apocalyptic danger, but also of exhilaration. There is for instance Götz Kubitschek, a publisher specializing in conservative nationalist or even outright reactionary authors, such as Jean Raspail and Renaud Camus, who keep warning of an “invasion” or a “great population replacement” in Europe. Kubitschek tells Pegida demonstrators that it is a pleasure (lust) to be angry. He is also known for organizing conferences at his manor in Saxony-Anhalt, including for the “Patriotic Platform.” His application to join the AfD was rejected during the party’s earlier, more moderate phase, but he has hosted the chairman of the AfD, Björn Höcke, in Thuringia. Höcke, a secondary school teacher by training, offered a lecture last fall about the differences in “reproduction strategies” of “the life-affirming, expansionary African type” and the place-holding European type. Invoking half-understood bits and pieces from the ecological theories of E. O. Wilson, Höcke used such seemingly scientific evidence to chastise Germans for their “decadence.”

Like at least some radicals in the late Sixties, the new right-wing “avant-garde” finds the present moment not just one of apocalyptic danger, but also of exhilaration. There is for instance Götz Kubitschek, a publisher specializing in conservative nationalist or even outright reactionary authors, such as Jean Raspail and Renaud Camus, who keep warning of an “invasion” or a “great population replacement” in Europe. Kubitschek tells Pegida demonstrators that it is a pleasure (lust) to be angry. He is also known for organizing conferences at his manor in Saxony-Anhalt, including for the “Patriotic Platform.” His application to join the AfD was rejected during the party’s earlier, more moderate phase, but he has hosted the chairman of the AfD, Björn Höcke, in Thuringia. Höcke, a secondary school teacher by training, offered a lecture last fall about the differences in “reproduction strategies” of “the life-affirming, expansionary African type” and the place-holding European type. Invoking half-understood bits and pieces from the ecological theories of E. O. Wilson, Höcke used such seemingly scientific evidence to chastise Germans for their “decadence.”

Gewalt, Wut und Zorn sind ohnehin Schlüsselbegriffe in der Welt des Marc Jongen. «Wir pflegen kaum noch die thymotischen Tugenden, die einst als die männlichen bezeichnet wurden», doziert der Philosoph, weil «unsere konsumistische Gesellschaft erotozentrisch ausgerichtet» sei. Für die in klassischer griechischer Philosophie weniger bewanderten Leserinnen und Leser: Platon unterscheidet zwischen den drei «Seelenfakultäten» Eros (Begehren), Logos (Verstand) und Thymos (Lebenskraft, Mut, mit den Affekten Wut und Zorn). Jongen spricht gelegentlich auch von einer «thymotischen Unterversorgung» in Deutschland. Es fehle dem Land an Zorn und Wut, und deshalb mangle es unserer Kultur auch an Wehrhaftigkeit gegenüber anderen Kulturen und Ideologien.

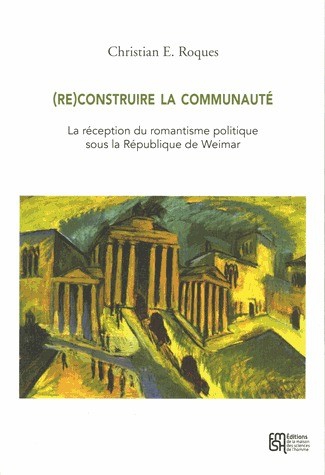

Gewalt, Wut und Zorn sind ohnehin Schlüsselbegriffe in der Welt des Marc Jongen. «Wir pflegen kaum noch die thymotischen Tugenden, die einst als die männlichen bezeichnet wurden», doziert der Philosoph, weil «unsere konsumistische Gesellschaft erotozentrisch ausgerichtet» sei. Für die in klassischer griechischer Philosophie weniger bewanderten Leserinnen und Leser: Platon unterscheidet zwischen den drei «Seelenfakultäten» Eros (Begehren), Logos (Verstand) und Thymos (Lebenskraft, Mut, mit den Affekten Wut und Zorn). Jongen spricht gelegentlich auch von einer «thymotischen Unterversorgung» in Deutschland. Es fehle dem Land an Zorn und Wut, und deshalb mangle es unserer Kultur auch an Wehrhaftigkeit gegenüber anderen Kulturen und Ideologien. Le livre récent de Christian E. Roques

Le livre récent de Christian E. Roques