vendredi, 26 février 2010

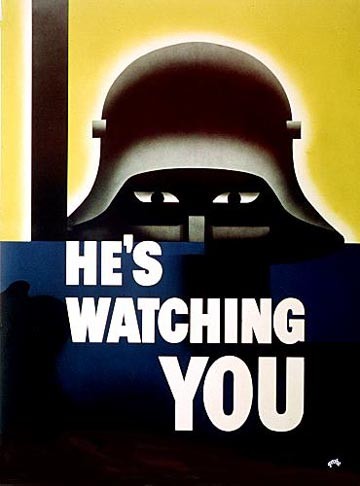

Stillgestanden, Pappkameraden: Europäische Armeen verkommen zu militärischen Pleitegeiern

Stillgestanden, Pappkameraden: Europäische Armeen verkommen zu militärischen Pleitegeiern

Europäische Armeen waren einmal wehrhaft. Sie wurden aufgestellt, um jederzeit Land und Bürger zu verteidigen. Doch verweichlichte Politiker haben aus europäischen Demokratien Bananenrepubliken gemacht. Und aus den europäischen Armeen arme Pappkameraden. Für Verteidigung ist kein Geld mehr da. Denn Feinde sind aus der Sicht unserer Politiker ja inzwischen zu angeblichen »Kulturbereicherern« mutiert. Jeder Böswillige wird als »kulturelle Bereicherung« hofiert. Und so wächst das innere Aggressionspotenzial in den europäischen Bananenrepubliken unaufhaltsam. Die Folge des Geldmangels der Armeen: Die Schweizer haben inzwischen nur noch Medikamenten-Attrappen in den Sanitätszelten. Und die Bundeswehr hat für das ganze Jahr 2010 keinen Schuss Munition mehr für das Standardgewehr G36. Ein Bundeswehreinsatz im Innern wäre 2010 deshalb wohl eher eine satirische Lachnummer.

Am 26. Januar wurde auf dem Schweizer Infanterie-Gebirgsschiessplatz Rothenthurm-Altmatt ein Soldat durch eine explodierende Handgranate schwer verletzt. Doch statt – wie geschehen – die Sanitätskompanie-7 zu Hilfe zu rufen, hätte man besser sofort das nächste Krankenhaus und einen Notarzt informiert. Wegen der Finanznot der Armee verfügen Schweizer Sanitäter nur noch über Medikamenten-Attrappen. Dem vor Schmerzen stöhnenden Opfer, das in Beinen, Brust und Bauch Granatsplitter hatte, konnten die Armee-Sanitäter nur eine einfache Infusion mit einer Salzlösung anbieten. Inzwischen gehören nicht einmal mehr Schmerzmittel bei Wehrübungen zur Grundausstattung Schweizer Sanitäter. Das Opfer wurde in einer Notoperation in einer privaten Klinik gerettet.

Am 26. Januar wurde auf dem Schweizer Infanterie-Gebirgsschiessplatz Rothenthurm-Altmatt ein Soldat durch eine explodierende Handgranate schwer verletzt. Doch statt – wie geschehen – die Sanitätskompanie-7 zu Hilfe zu rufen, hätte man besser sofort das nächste Krankenhaus und einen Notarzt informiert. Wegen der Finanznot der Armee verfügen Schweizer Sanitäter nur noch über Medikamenten-Attrappen. Dem vor Schmerzen stöhnenden Opfer, das in Beinen, Brust und Bauch Granatsplitter hatte, konnten die Armee-Sanitäter nur eine einfache Infusion mit einer Salzlösung anbieten. Inzwischen gehören nicht einmal mehr Schmerzmittel bei Wehrübungen zur Grundausstattung Schweizer Sanitäter. Das Opfer wurde in einer Notoperation in einer privaten Klinik gerettet.

Bei der deutschen Bundeswehr sieht es nicht besser aus: Sie gibt zwar Milliarden für neue Rüstungsgroßprojekte aus, kann aber den Soldaten nicht einmal mehr die einfachsten Patronen aushändigen. Der Etat für Handfeuerwaffen der Bundeswehr ist schon jetzt für das komplette Jahr 2010 aufgebraucht. Es wurden bislang 30 Millionen Patronen des Typ 5,65 Millimeter Doppelkern (für das G36) verschossen. Das Verteidigungsministerium sucht nun einen Sponsor, der deutschen Soldaten 31,2 Millionen Euro für den Munitionsbedarf bis Ende 2010 zur Verfügung stellt. Auch wenn sich morgen ein Geldgeber finden würde, hilft das nicht sofort weiter: Die Lieferzeit für die Munition beträgt derzeit mehr als ein halbes Jahr. Wenn deutsche Politiker also über einen Bundeswehreinsatz im Innern fabulieren, dann ist das vor diesem Hintergrund eine Satire erster Klasse.

Mittwoch, 17.02.2010

© Das Copyright dieser Seite liegt, wenn nicht anders vermerkt, beim Kopp Verlag, Rottenburg

Dieser Beitrag stellt ausschließlich die Meinung des Verfassers dar. Er muß nicht zwangsläufig die Meinung des Verlags oder die Meinung anderer Autoren dieser Seiten wiedergeben.

00:15 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, armées, europe, affaires européennes, défense, politique, politique internationale, déclin, décadence, suisse, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 25 février 2010

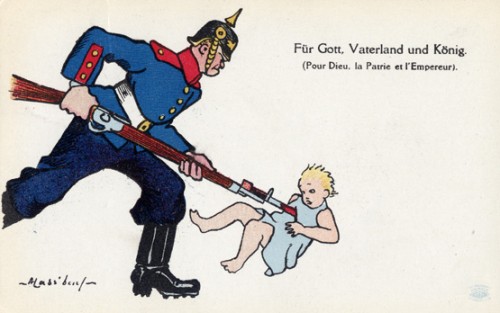

Réflexions sur le voyage de Guillaume II en Palestine

Alois PRESSLER :

Réflexions sur le voyage de Guillaume II en Palestine

Lorsque l’on prononce les mots « Palestine » et « Proche Orient », on songe immédiatement à l’Intifada, à une guerre perpétuelle, surtout pour l’enjeu pétrolier. Le pétrole, en effet, fut l’un des motifs principaux du voyage en Palestine de l’Empereur d’Allemagne Guillaume II du 11 octobre au 26 novembre 1898.

Inauguration de la Basilique Saint Sauveur

Au cours de ce voyage, l’Empereur visita également Constantinople, Haïfa, Jérusalem, Jaffa et Beyrouth. La visite visait plusieurs objectifs : elle entendait consolider la position du Sultan turc Abdoul Hamid II et renforcer le poids de l’église protestante, évangélique et luthérienne au Proche Orient (car, à cette époque, quasi la moitié des chrétiens vivant en Palestine venaient d’Allemagne). Enfin, l’Empereur voulait inaugurer la Basilique Saint Sauveur à Jérusalem.

Scepticisme des Français

Dans l’opinion publique française, ce fut un tollé : on s’est très vite imaginé que Guillaume II voulait, par son voyage, miner la protection traditionnelle qu’offrait la France aux catholiques de Palestine. Ce reproche était dénué de tout fondement, de même que l’allusion à une éventuelle volonté allemande de s’approprier la Palestine.

Un sermon plein de reproches aux églises…

Le 25 octobre 1898, Guillaume II arrive en Palestine, premier Empereur du Reich allemand à y remettre les pieds depuis 670 ans (quand Frédéric II avait débarqué à Saint Jean d’Acre). Après avoir reproché amèrement aux représentants du clergé dans un sermon plein de reproche à Bethléem, où l’Empereur morigénait la désunion entre chrétiens (à maintes reprises, des soldats turcs avaient dû intervenir pour apaiser les querelles entre les diverses confessions chrétiennes).

Le rejet de l’idée d’un Etat juif

Le 31 octobre, enfin, eut lieu l’événement majeur du voyage de Guillaume II : l’inauguration de la Basilique Saint Sauveur à Jérusalem. Le 2 novembre, une délégation sioniste rend visite à l’Empereur dans le camp militaire, composés de tentes, qu’il occupe : elle est présidée par Theodor Herzl. L’Empereur spécifie clairement à la délégation qu’il est prêt à soutenir toute initiative visant à augmenter le niveau de vie en Palestine et à y consolider les infrastructures mais que la souveraineté du Sultan dans la région est à ses yeux intangible. L’Empereur, en toute clarté, n’a donc pas soutenu le rêve de Theodor Herzl, de créer un Etat juif en Palestine, rêve qui ne deviendra réalité qu’en 1948.

En grande pompe…

Le 4 novembre, Guillaume II embarque à Jaffa pour revenir finalement le 26 novembre à Berlin et s’y faire fêter triomphalement, ce qui ne se fit pas sans certaines contestations (sa propre sœur n’approuva pas l’ampleur des festivités).

Sur le plan politique, cette visite ne fut pas un succès

Le voyage de Guillaume II en Palestine ne fut pas un grand succès politique. Certes, les rapports avec le Sultan furent améliorés, condition essentielle pour la réalisation du chemin de fer vers Bagdad et pour la future alliance avec l’Empire ottoman lors de la première guerre mondiale. Cependant, l’Empereur n’a pas pu assurer à l’Allemagne l’octroi de bases ou de zones d’influence. De même, les Allemands et les Juifs allemands installés en Palestine ont certes reçu un appui indirect par la construction de routes et de ponts, de façon à avantager les initiatives des sociétés touristiques mais tout cela ne constituait pas un appui politique direct, que l’Empereur n’accorda pas. En Europe, ce voyagea se heurta à bon nombre de contestations. En Allemagne même, ce voyage, sans résultats à la clef, n’a pas bénéficié de soutiens inconditionnels.

Sur le voyage : rapports positifs

L’Empereur d’Allemagne a toutefois réussi à présenter son voyage de manière attrayante et populaire, en diffusant au sein de la population des rapports positifs et flatteurs sur son voyage au Proche Orient. Il y a 120 ans, toute politique proche orientale faisait déjà l’objet d’un travail médiatique et n’était pas assurée de succès durables.

Alois PRESSLER.

(article paru dans « Der Eckhart », Vienne, octobre 2007 ; trad.. franc. : Robert Steuckers, février 2010).

00:10 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, palestine, proche-orient, méditerranée, allemagne, turquie, empire ottoman, jérusalem |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 23 février 2010

Presseschau 03/Februar 2010

Presseschau

03 / Februar 2010

Einige Links. Bei Interesse anklicken...

###

Atomstreit

Irans Außenminister Mottaki brüskiert die Welt

Keine Zusagen, nur heiße Luft: Wenn das ein Versöhnungsversuch war, ist er gescheitert. Irans Außenminister Mottaki hat bei seinem Auftritt auf der Münchner Sicherheitskonferenz die Mächtigen der Welt enttäuscht. Nun stehen Sanktionsdrohungen im Raum.

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/0,1518,676364,00.html

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/0,1518,676412,00.html

Atomstreit

US-Senator Lieberman droht Iran mit Krieg

Den Auftritt von Irans Außenminister Mottaki bei der Münchner Sicherheitskonferenz nennt er „lachhaft“ und „unredlich“: Jetzt hat US-Senator Joseph Lieberman mit einem Militärschlag gedroht, wenn Wirtschaftssanktionen nicht wirken sollten.

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/0,1518,676380,00.html

Jerusalem

Berlusconi wirbt für Aufnahme Israels in die EU

http://www.focus.de/politik/ausland/jerusalem-berlusconi-wirbt-fuer-aufnahme-israels-in-die-eu_aid_476208.html

Türkische Schulen

„Wir erklären sogar den Dreisatz mit Atatürk“

Aus Istanbul berichten Markus Flohr und Maximilian Popp

In der Schule lernen Kinder lesen, rechnen, schreiben. In der Türkei lernen sie außerdem: Staatsgründer Atatürk bedingungslos zu lieben. Sie können seinen Lebenslauf auswendig und singen seine Kampflieder – als Schutz gegen den Islamismus, sagen Befürworter. Die Kritiker leiden unter der Indoktrination.

http://www.spiegel.de/schulspiegel/ausland/0,1518,675820,00.html

Visumpolitik

Türkei ärgert EU mit Grenzöffnung nach Nahost

Von Boris Kalnoky

Ankara hebt die Visumpflicht für mehrere Länder des Nahen Ostens auf, darunter Syrien und Libyen. Für die Harmonisierung mit der EU ist das ein Rückschlag. Denn über die Türkei reisen schon jetzt zahlreiche illegale Migranten in EU-Länder ein. Die Entscheidung ist nur ein Beispiel für einen neuen Konfrontationskurs.

http://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article6353908/Tuerkei-aergert-EU-mit-Grenzoeffnung-nach-Nahost.html

Türkei „unschätzbar kostbar“ für Deutschland

Der deutsche Botschafter in der Türkei Dr. Eckart Cuntz (Foto) meint, sein Land sei dazu verpflichtet, dafür zu sorgen, daß die Beitrittsverhandlungen der Türkei in die EU fortgeführt würden. Eine privilegierte Parnerschaft als Alternativlösung komme nicht in Frage. Cuntz stützt sich mit dieser Ansicht explizit auf Außenminister Westerwelle, der bei seinem Besuch in der Türkei am 6. Februar versprochen hatte, Deutschland werde seine besondere Verantwortung in diesem Prozeß wahrnehmen.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/tuerkei-unschaetzbar-kostbar-fuer-deutschland/#more-117967

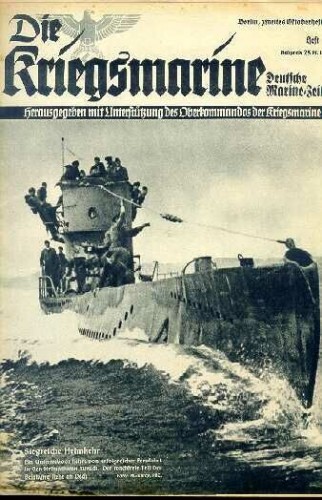

Militärtechnologie

Chinas Massenarmee wandelt sich zur Hightech-Truppe

Von Markus Becker

Tarnkappenflugzeuge, U-Boote, Anti-Satelliten-Waffen und sogar ein eigener Flugzeugträger: China modernisiert seine Streitkräfte in enormer Geschwindigkeit. Schon bald könnte die militärtechnologische Überlegenheit der USA wanken.

http://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/mensch/0,1518,676549,00.html

Jemen: Tummelplatz für „al Qaida“ oder geopolitischer Engpaß für Eurasien

F. William Engdahl

Am 25. Dezember 2009 wurde in den USA der Nigerianer Abdulmutallab verhaftet, weil er versucht hatte, ein Flugzeug der „Northwest Airlines“ auf dem Flug von Amsterdam nach Detroit mit eingeschmuggeltem Sprengstoff in die Luft zu sprengen. Seitdem überschlagen sich die Medien, von CNN bis zur „New York Times“, mit Meldungen, es bestehe der „Verdacht“, daß er im Jemen für seine Mission ausgebildet worden sei. Die Weltöffentlichkeit wird auf ein neues Ziel für den „Krieg gegen den Terror“ der USA vorbereitet: Jemen, ein trostloser Staat auf der arabischen Halbinsel. Sieht man sich jedoch den Hintergrund etwas genauer an, dann scheint es, als verfolgten das Pentagon und der US-Geheimdienst im Jemen ganz andere Pläne.

http://info.kopp-verlag.de/news/jemen-tummelplatz-fuer-al-qaida-oder-geopolitischer-engpass-fuer-eurasien.html

Regierung: „Bewaffneter Konflikt“ in Afghanistan

Westerwelle wirbt im Bundestag für neues Mandat – Oberst Klein vor Kundus-Ausschuß

Die Bundesregierung stuft die Situation in Afghanistan jetzt offiziell als „bewaffneten Konflikt im Sinne des Völkerrechts“ ein. Die Lage klar zu benennen, habe rechtliche Folgen für die deutschen Soldaten, sagte Außenminister Westerwelle im Bundestag.

http://www.heute.de/ZDFheute/inhalt/31/0,3672,8031487,00.html

Klein: Angriff war legal und gerechtfertigt

Oberst vor Untersuchungsausschuß

Legal und gerechtfertigt: Oberst Klein steht zu seinem Befehl vom September, der den Luftschlag auf die beiden Tanklaster in Afghanistan ausgelöst hat. Das teilte sein Anwalt mit. Klein steht heute vor dem Untersuchungsausschuß des Bundestages.

http://www.heute.de/ZDFheute/inhalt/5/0,3672,8031557,00.html

Klingt nach guter Arbeit des KSK (was hat dieser „Spiegel“-Schreiberling überhaupt für ein Problem?) ...

Kunduz-Untersuchungsausschuß

Die dunklen Geheimnisse der KSK-Krieger

Von Matthias Gebauer

Mit dem Auftritt von Oberst Klein startet der Kunduz-Ausschuß – doch gleich danach werden sich die Parlamentarier mit dem Kommando Spezialkräfte beschäftigen müssen. Geheime Nato-Unterlagen belegen: In der Bombennacht spielten KSK-Elitekämpfer eine entscheidende Rolle.

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/0,1518,676923,00.html

Abstellen!

Demütigung bei der Bundeswehr

Soldaten mußten rohe Schweineleber essen

Der Bundeswehr droht ein neuer Mißbrauchsskandal: Ein ehemaliger Wehrpflichtiger hat sich einem Zeitungsbericht zufolge beim Wehrbeauftragten über entwürdigende Mutproben und Aufnahmerituale beschwert – demnach mußten Soldaten rohe Schweineleber essen und bis zum Erbrechen Alkohol trinken. http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/0,1518,676897,00.html

Das Stigma besiegen!

Von Carlo Clemens

Wenn ich Interviews mit vermeintlich „konservativen“ Hoffnungsträgern der Union lese, bleibt bei mir immer die Frage: Geht es diesen Leuten eigentlich um Deutschlands Zukunft, oder um die Zukunft ihrer Partei? Um Prozente und Posten oder um Inhalte und Überzeugungen?

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5d8d4b42199.0.html

Koalition plant „Löschgesetz“

Schwarz-Gelb rückt von Internetsperren ab

Von Stefan Berg und Marcel Rosenbach

Kurswechsel nach monatelangem Hickhack: In einem Brief an Bundespräsident Köhler geht die Regierung nach Informationen des SPIEGEL auf Distanz zum umstrittenen Internet-Sperrgesetz. Schwarz-Gelb kündigt nun eine neue Initiative für ein „Löschgesetz“ an.

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/0,1518,676669,00.html

Kommentar zu Hartz IV

Der Staat muß die Spendierhosen ablegen

Von Dorothea Siems

Die Hartz-IV-Regelsätze müssen neu berechnet werden. Das heißt nicht unbedingt, daß die Transferempfänger künftig mehr Geld in der Tasche haben. Schon heute leben sie manchmal besser als andere Arbeitnehmer. Der Staat sollte unbedingt dafür sorgen, daß nicht der Steuerzahler der Dumme ist.

http://www.welt.de/debatte/article6315717/Der-Staat-muss-die-Spendierhosen-ablegen.html

Wie man mit viel Geld Armut vermehrt

Von Gunnar Heinsohn

Höhere Sozialleistungen steigern die Geburtenrate von arbeitslosen Frauen. Bill Clinton kürzte in Amerika die Bezüge – mit Erfolg.

[Heinsohn hat vieles begriffen – vom „youth bulge“ bis eben zur Sozialstaatsproblematik. Seine Weisheit hat jedoch enge Grenzen, wie seine grandiosen Vorschläge zur massenhaften Aufnahme von Chinesen aus rein wirtschaftlichen Erwägungen offenbaren. Darauf, daß das Hauptaugenmerk auf die demographische Stabilisierung des deutschen Volkes und die Verhinderung der Abwanderung bzw. die Rückgewinnung qualifizierter Deutscher gelegt werden müßte, ergänzt um ethnisch-kulturell kompatible europäische bzw. europäischstämmige Zuwanderung, kommt er nicht. Er bleibt halt doch der alte 68er, der er immer war: jemand, dem die Zukunft seines Volkes letztlich vollkommen gleichgültig ist.]

http://www.welt.de/die-welt/debatte/article6311869/Wie-man-mit-viel-Geld-Armut-vermehrt.html

Debatte um Hartz-IV-Urteil

Westerwelles Worte schlagen Wellen

In Deutschland herrscht „geistiger Sozialismus“ – das findet zumindest FDP-Chef Guido Westerwelle, wenn es um die Hartz-IV-Regelsätze geht. Ein einmaliger verbaler Ausrutscher des Vizekanzlers? Keineswegs, denn nun legte er noch einmal nach: „Die Diskussion über das Hartz-IV-Urteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts hat sozialistische Züge. Von meiner Kommentierung dieser Debatte habe ich keine Silbe zurückzunehmen“, sagte Westerwelle der „Passauer Neuen Presse“. Und schob als Erklärung hinterher: „Wenn man in Deutschland schon dafür angegriffen wird, daß derjenige, der arbeitet, mehr haben muß als derjenige, der nicht arbeitet, dann ist das geistiger Sozialismus.“

http://www.tagesschau.de/inland/westerwellehartziv100.html

Krisenprophet Max Otte

„Die Welt steht kurz vor dem Crash“

Schon 2006 warnte Max Otte vor der Krise – kaum einer hörte zu. Jetzt meldet sich der Ökonom erneut zu Wort: warum das Schlimmste noch kommt.

http://www.focus.de/finanzen/boerse/finanzkrise/tid-16399/krisenprophet-max-otte-die-welt-steht-kurz-vor-dem-crash_aid_458118.html

„PIGS“

Von Michael Paulwitz

Sage noch einer, Banker hätten keinen Humor. Für die inflationsgeneigten Hochrisikostaaten der Eurozone, die mit ihren Schuldenbergen immer munter an der Klippe zum Staatsbankrott entlangschrammen, für Portugal, Italien, Griechenland und Spanien also, hat die Finanzwelt seit kurzem ein prägnantes Sammelkürzel: PIGS.

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display.154+M5636df48d98.0.html

Schuldenkrise

Europa fürchtet die verflixten Fünf

Von Stefan Schultz

Erst Griechenland, dann Portugal und Spanien – schließlich Italien und Irland? Die Krise hat die Schulden von fünf EU-Problemstaaten so hochgetrieben, daß es Ökonomen vor einem Euro-Crash graut. SPIEGEL ONLINE tastet die Risikozonen des Kontinents ab: Wieviel Grund zur Panik gibt es wirklich?

http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/0,1518,676966,00.html

Politisches Gangsterstück

Von Thorsten Hinz

Und es kommt, wie’s kommen mußte. Europa (also vor allem Deutschland) wird für den Schlendrian in Griechenland (und danach in Portugal, Spanien, Italien, Irland) einstehen. Darüber läßt sich nicht mehr nur in politischen Kategorien reden.

Wir befinden uns mitten in einem Gangsterstück. Nichts gegen supranationale Strukturen in Europa, allein schon aus der Erwägung heraus, daß die europäischen Nationalstaaten im globalen Konkurrenzkampf sich nur gemeinsam behaupten können. Vielleicht war und ist auch die Idee des Euro im Prinzip richtig, aber daß man keine Rennpferde mit einer mediterranen Schindmähre wie Griechenland in dasselbe Gespann zwingen kann, hätte klar sein müssen.

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M54303cf8937.0.html

Brüsseler Roulette

Vor knapp zwölf Jahren, im Sommer 1998, wohnte ich zum ersten und bisher letzten Mal einer Partei-Wahlveranstaltung bei. Die Partei wurde damals als eine vielversprechende nationalliberale Neugründung und aufstrebende Alternative für von der verkrusteten CDU/FDP-Koalition enttäuschte Wähler gehandelt. Ihr Name tut nichts zur Sache, denn sie verschwand – wie auch bis heute auf dieser Seite der politischen Arithmetik üblich – wieder in der Versenkung.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/bruesseler-roulette/#more-118046

Extremismus

BKA beklagt zunehmende Gewalt gegen Polizisten

http://www.focus.de/politik/deutschland/extremismus-bka-beklagt-zunehmende-gewalt-gegen-polizisten_aid_475545.html

Umstrittene Studie zu Gewalt gegen Polizisten startet

http://www.welt.de/die-welt/politik/article6275916/Umstrittene-Studie-zu-Gewalt-gegen-Polizisten-startet.html

Die deutsche Sprache vor Gericht

Von Thomas Paulwitz

Der Vorstoß, Englisch zur Gerichtssprache in Deutschland zu machen, trifft nun endlich auf entscheidenden Widerstand. Kein Geringerer als der Präsident des Bundesgerichtshofs (BGH) äußerte nun Bedenken. Das kommt genau zur rechten Zeit, denn in knapp einer Woche soll angeblich der Gesetzesentwurf Hamburgs und Nordrhein-Westfalens im Bundesrat beraten werden.

Der BGH wäre von einer Änderung des Gerichtsverfassungsgesetzes (GVG) unmittelbar betroffen. So soll Paragraph 184 GVG unter anderem mit dem Satz ergänzt werden: „Vor dem Bundesgerichtshof kann in internationalen Handelssachen das Verfahren in englischer Sprache geführt werden.“

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/index.php?id=154&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=85959&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=468&cHash=4fbf0e01c1&MP=154-576

Angeblich Schlamperei vor Einsturz von Kölner Stadtarchiv

Bei den Ermittlungen zum Einsturz des Kölner Stadtarchivs liegt der Staatsanwaltschaft einem Zeitungsbericht zufolge ein erstes Geständnis vor: Wie der „Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger“ berichtet, räumte ein Bauarbeiter der U-Bahnlinie unter der Kölner Südstadt ein, daß an der Unglücksstelle bewußt nachlässig gearbeitet worden sei.

http://portal.gmx.net/de/themen/nachrichten/panorama/9836648-Schlamperei-bei-Koelner-U-Bahnbau.html#.00000002?CUSTOMERNO=39290822&t=de1201636392.1265920406.4704aac2

Platzeck nennt Stasi-Kritiker „Revolutionswächter“

POTSDAM. Brandenburgs Ministerpräsident Matthias Platzeck (SPD) hat die Kritiker der Stasi-Vergangenheit von Abgeordneten der Linkspartei scharf zurechtgewiesen. „Wir haben eine Schar von Revolutionswächtern, die gehen mir auf den Keks“, zitieren ihn die „Potsdamer Neuesten Nachrichten“.

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/index.php?id=154&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=85957&cHash=6accd4a8e0

Stasi-Fälle

Kritik an Lötzsch wegen IM-Fürsprache

http://www.focus.de/politik/deutschland/stasi-faelle-kritik-an-loetzsch-wegen-im-fuersprache_aid_478013.html

Gründung vor 60 Jahren

Die tödlichen Methoden der DDR-Staatssicherheit

Von Sven Felix Kellerhoff

Lauschen, spähen, schnüffeln: Vor 60 Jahren wurde die DDR-Staatssicherheit gegründet. Mehr als 91.000 hauptamtliche und doppelt so viele inoffizielle Mitarbeiter garantierten der SED die Macht. Ein Geheimdienst im klassischen Sinn war der Apparat nie, eher schon eine kriminelle Vereinigung mit tödlichen Methoden.

http://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article6299413/Die-toedlichen-Methoden-der-DDR-Staatssicherheit.html

Konstanz

Rechter Professor sorgt für Wirbel

An der Universität Konstanz erwächst Widerstand gegen den rechtskonservativen Professor Jost Bauch. Die Studenten beschlossen per Vollversammlung eine Ablehnung seiner Lehre. Der Universitätsleitung sind zwar juristisch die Hände gebunden, sie weist jedoch darauf hin, daß jeder entscheiden könne, ob er die Veranstaltung besuchen wolle.

http://www.suedkurier.de/region/kreis-konstanz/konstanz/Rechter-Professor-sorgt-fuer-Wirbel;art372448,4158892

Österreichischer Südtirol-Aktivist in Integrationsrat gewählt

MEERBUSCH. Der österreichische Arzt Erhard Hartung ist am vergangenen Sonntag in den Integrationsrat der nordrhein-westfälischen Stadt Meerbusch gewählt worden. Wegen seiner Beteiligung am Freiheitskampf in Südtirol in den sechziger Jahren hatte ihn die Unabhängige Wählergemeinschaft (UWG) im Rat der Stadt vor der Wahl zum Verzicht auf die Kandidatur aufgefordert.

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display.154+M5588583cc6b.0.html

Video: Dumm, dümmer, Antifa

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOFfVD248gI

Produzieren Nazis Bioessen?

Wer Bio-Produkte kauft, kann sich nicht sicher sein, wen seine Einkäufe da unterstützen: Es gibt tatsächlich völkisch-nationalistische Biobauern, die mit nett-nachbarschaftlichem Auftreten auf NPD-Stimmenfang gehen. Proteste führten bisher bei den Bioprodukte-Vertrieben nicht wirklich zu Reaktionen. Betrachtungen aus Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

http://www.netz-gegen-nazis.de/artikel/produzieren-neonazis-bioessen-3412

Brandanschlag

Feuer in Berliner Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

http://www.focus.de/panorama/vermischtes/brandanschlag-feuer-in-berliner-stiftung-wissenschaft-und-politik_aid_476306.html

Brände

Brandanschlag auf Haus der Wirtschaft in Berlin

http://www.zeit.de/newsticker/2010/2/4/iptc-bdt-20100204-60-23763212xml

Republik und Terror

Ein eiserner Windhauch

Von Jan Puhl

Die Erfinder der Guillotine waren beseelt vom Geist der Aufklärung.

http://www.spiegel.de/spiegelgeschichte/0,1518,674286,00.html

Vertriebenenstiftung

Regierungsfraktionen beenden Streit mit Steinbach

Der monatelange Konflikt über die Besetzung des Stiftungsrats der Vertriebenengedenkstätte ist beigelegt. Künftig wird der Bundestag die Mitglieder des Rats benennen, der Bund der Vertriebenen soll sechs statt wie geplant drei Sitze in dem Gremium bekommen. Steinbach sprach von einer „guten Lösung“.

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/0,1518,677268,00.html

http://nachrichten.rp-online.de/article/politik/Einigung-im-Fall-Steinbach/67619

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/0,1518,677350,00.html

http://www.tagesschau.de/multimedia/video/video653194.html

http://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article6358384/Opposition-Steinbach-Einigung-ist-beschaemend.html

http://www.rp-online.de/politik/deutschland/Steinbach-Kompromiss-Beschaemend-und-enttaeuschend_aid_819140.html

Kommentar

Sieg und Niederlage für Erika Steinbach

Von Marcus Schmidt

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display-mit-Komm.154+M5b9c8efd5d0.0.html

Verräter

Von Stefan Scheil

Das Münchner Institut für Zeitgeschichte gibt in der neuesten Ausgabe seiner Vierteljahrshefte sechzehn Seiten frei, auf denen Kurt Neuhiebel eine Attacke auf Manfred Kittels angebliche „Entkoppelung von Krieg und Vertreibung“ ausbreiten darf. In Neuhiebels Argumentationsgang treten dabei die altbekannten Kausalitäten auf.

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/index.php?id=154&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=85951&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=154&cHash=06dc287194&MP=154-594

Stefan Scheil im Gespräch: „Der Bombenkrieg war für die Westalliierten ein geeignetes Mittel zur Kriegsführung und Tötung“

Der Historiker Stefan Scheil forscht zu den Ursachen des Zweiten Weltkriegs. Er ist langjähriger Autor der „Jungen Freiheit“ und der „Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung“. 2005 erhielt er den „Gerhard-Löwenthal-Preis für Journalismus“. BlaueNarzisse.de sprach mit ihm im Vorfeld des 65. Jahrestags der Bombardierung Dresdens über die Ergebnisse der Dresdner Historikerkommission, Flüchtlinge in Dresden und die politischen Schatten der Bombardierung.

http://www.blauenarzisse.de/v3/index.php/aktuelles/1331-stefan-scheil-im-gespraech-der-bombenkrieg-war-fuer-die-westalliierten-ein-geeignetes-mittel-zur-kriegsfuehrung-und-toetung

Kontrovers diskutiert ...

Deutschland, halt’s Maul

Von Martin Lichtmesz

Wenn man noch irgendeinen Beweis dafür braucht, daß die Deutschen des beginnenden 21. Jahrhunderts das degenerierteste Volk auf diesem ganzen Erdball sind, dann sollte man sich den alljährlichen Hickhack um die Gedenkfeiern von Dresden zu Gemüte führen. Was hier geschieht, ist international beispiellos, und daß der Grad der Verkommenheit kaum mehr jemandem auffällt, ist Teil der Krankheit.

http://www.sezession.de/11660/deutschland-halts-maul.html

Unbedingt auch noch lesen ...

Sodom und Gomorrah (nochmals Dresden)

Von Martin Lichtmesz

Die Genesis, das 1. Buch Mose des Alten Testaments, berichtet, wie Gott in Begleitung zweier Engel bei Abraham einkehrte, dessen Neffe Lot mit seiner Familie in der vom Glauben abgefallenen Stadt Sodom lebte. Gott war gekommen, um Abraham trotz des fortgeschrittenen Alters seines Weibes Sara die Geburt eines Sohnes anzukündigen. Als er sich anschickte weiterzuziehen, zögerte Gott:„Wie kann ich Abraham verbergen, was ich tue, sintemal er ein großes und mächtiges Volk soll werden, und alle Völker auf Erden in ihm gesegnet werden sollen?“

http://www.sezession.de/11993/sodom-und-gomorrah-nochmals-dresden.html

„Perlensamt“ von Barbara Bongartz

Von Götz Kubitschek

Möchte man ein Jude sein, heutzutage, ein Broder etwa, der ausstoßen darf, was er will, weil er weiß, daß ihm niemand kann? Vielleicht, manchmal. Aber es gibt auch einen anderen Weg: Man könnte der Erbe einer Nazigröße sein und sehr öffentlich zeigen, daß man alles wiedergutmachen will. Darum gehts in Perlensamt, und es gibt – nach einigem Nachdenken und wiederholter Lektüre dieses Buches – keinen Zweifel:

Perlensamt ist ein Schlüsselroman des deutschen Schuldstolzes um die Jahrtausendwende, und zwar ein sehr gelungener.

http://www.sezession.de/11787/perlensamt-von-barbara-bongartz.html#more-11787

Judenvergleich

Jesuiten distanzieren sich

http://www.tagesspiegel.de/weltspiegel/art1117,3023254

http://newsticker.welt.de/?module=dpa&id=23781084

http://www.wienerzeitung.at/DesktopDefault.aspx?TabID=3941&Alias=wzo&cob=470392

„Max Manus“ in den Kinos

Historien-Drama

http://www.filmstarts.de/kritiken/104143-Max-Manus.html

Einbeinige, rollstuhlfahrende, blinde Puppen oder siamesische Zwillinge aus Plastik sind auch noch viel zu wenig in Spielwarenläden verbreitet ...

Hanau

Ausstellung im Puppenmuseum hinterfragt Rollenklischees in Kinderzimmern

Mama kocht, Papa schaut fern

http://www.op-online.de/nachrichten/hanau/mama-kocht-papa-schaut-fern-620970.html

Diskriminierte Puppen

Von Ellen Kositza

Ans Puppenmuseum der Brüder-Grimm-Stadt Hanau hab ich noch folgende Erinnerung: Als uns in der sechsten Klasse mitgeteilt wurde, daß der nächste „Wandertag“ eine Fahrt in ebendieses Puppenmsueum bedeuten würde, ertönte Jubel, 25 Armpaare erhoben sich in frenetischer Begeisterung, zwei blieben unten – jene Mädchen haßten Puppen.

http://www.sezession.de/11939/diskriminierte-puppen.html

Verfassungspatriotismus funktioniert nicht ...

Regierungsbilanz

Frankreichs Nationaldebatte stigmatisiert Ausländer

Von Gesche Wüpper

Die von Staatspräsident Nicolas Sarkozy angestoßene Debatte über die nationale Identität ist gescheitert. Statt zu einer besseren Integration führte sie zu einer weiteren Stigmatisierung von Ausländern und vor allem der etwa fünf bis sechs Millionen in Frankreich lebenden Muslime. Profitiert haben die Rechtsextremen.

http://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article6306935/Frankreichs-Nationaldebatte-stigmatisiert-Auslaender.html

Furchtbare Juristen ...

Abgeschobener Asylbewerber darf nach Deutschland zurückkehren

FRANKFURT/ODER. Ein nach Griechenland abgeschobener Iraker muß nach Deutschland zurückgeholt werden. Das entschied das Verwaltungsgericht Frankfurt/Oder. Das Gericht begründete nach einem Bericht der „Berliner Zeitung“ seine Entscheidung damit, daß die in Griechenland für Asylbewerber herrschenden Verhältnisse dem Iraker nicht zuzumuten seien. Zur Zeit müsse dieser als Obdachloser in einem Park leben.

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display.154+M595ecc094db.0.html

Kolat: Migranten wollen Nestwärme fühlen

Kenan Kolat, Chef der Türkischen Gemeinde in Deutschland, findet, daß die Migranten so viel zur Integration geleistet hätten, daß jetzt mal die Deutschen dran sind. Die Kanzlerin solle sich gefälligst persönlich einbringen und ein Willkommensfest für Zuwanderer organisieren.

Angesichts zunehmender Fälle von Migrantengewalt auf unseren Straßen, tun wir nichts lieber, als die moslemischen Zuwanderer und ihre Kinder bei uns herzlich willkommen zu heißen. Herr Kauder hatte dies ja bereits auch von uns gefordert.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/kolat-migranten-wollen-nestwaerme-fuehlen/#more-117159

Berliner Polizisten müssen immer öfter flüchten

Die Islamisierung Berlins schreitet zügig voran. In den „Tagesthemen“ vom 2. Februar lieferte die ARD einen tiefen Einblick in die dramatische Situation der Berliner Polizei. Die Sendung ist zwar schon über eine Woche alt, aber ihr Inhalt ist hochbrisant und brandaktuell.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/berliner-polizisten-muessen-immer-oefter-fluechten/#more-118021

Gewalt gegen Polizisten

Bespuckt, beschimpft, bedroht

Von Jörg Diehl

Freund und Helfer war gestern – heute treffen Polizisten immer öfter auf Verachtung, Ablehnung, Aggression. In einer großen Studie soll der beunruhigende Trend jetzt untersucht werden: „Bullen aufzumischen“ sei längst zum Hobby gewalttätiger Jugendgangs geworden, klagen Beamte.

http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/justiz/0,1518,677320,00.html

Kölner Polizei sucht sonnengebräunten Südländer

Die Kölner Polizei sucht nach einem brutalen Überfall am Donnerstag auf eine 26jährige Frau nach einem „südländisch wirkenden, schlanken Mann zwischen 30 und 40 Jahren, der stark sonnengebräunt ist“. Der Täter soll der Frau mit der Faust ins Gesicht geschlagen und sie am Boden liegend getreten haben.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/koelner-polizei-sucht-sonnengebraeunten-suedlaender/#more-117098

München: Zivilcourage mit Messerstich bezahlt

Wenn demnächst kaum mehr einer Zivilcourage zeigen will, dann liegt es an Fällen wie diesem, die in letzter Zeit immer häufiger passieren: In München – in der Stadt also, wo vor einigen Monaten Dominik Brunner zu Tode getreten wurde – mußte in der Nacht zu Samstag auch ein 18jähriger fast mit seinem Leben bezahlen, weil er einem Bekannten helfen wollte. Einer der Angreifer, laut Münchner tz türkischstämmig, stach ihn mit dem Messer nieder.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/muenchen-zivilcourage-mit-messerstich-bezahlt/

Dieser Fall ist schon etwas älter ...

Brutale Attacke vor der Disco

Mehrjährige Haftstrafen für gefährliche Schlägerei

Darmstadt (ddp). Das Darmstädter Landgericht hat drei brutale Schläger im Alter zwischen 19 und 42 Jahren zu mehrjährigen Haftstrafen verurteilt. Das Gericht sah es als erwiesen an, daß die Angeklagten den 29 Jahre alten Fabian S. aus dem südhessischen Bensheim im September 2008 bewußtlos geschlagen und ihn hilflos auf der Straße zurückgelassen hatten.

Das Opfer wurde von einem Taxi überrollt und starb vier Wochen später. Der 29jährige war zuvor in einer Bensheimer Diskothek einem jungen Mann zu Hilfe geeilt, der von den Schlägern verprügelt wurde.

Ein vierter Tatbeteiligter hatte sich vor Prozeßeröffnung in die Türkei abgesetzt. Vor Gericht verantworten mußten sich der 42jährige Erdogan M. aus Bensheim, sein 19jähriger Sohn Haydar M. und dessen gleichaltriger Halbbruder Volkan T. Auch weil er als Vater besondere Verantwortung trug, verurteilte das Gericht Erdogan M. zu sechs Jahren Gefängnis. Sein Sohn muß drei Jahre und sechs Monate in Haft, Volkan T. für drei Jahre und drei Monate. Alle drei Angeklagten wurden wegen gemeinschaftlich begangener gefährlicher Körperverletzung sowie anschließender Aussetzung mit Todesfolge schuldig gesprochen.

http://www3.e110.de/index.cfm?event=page.detail&cid=2&fkcid=1&id=46571

Dietzenbach/Offenbach

Polizei läßt Bande auffliegen

http://www.fr-online.de/frankfurt_und_hessen/nachrichten/kreis_offenbach/2271619_Dietzenbach-Offenbach-Polizei-laesst-Bande-auffliegen.html

Multikulturelle Bereicherung zum Après-Ski

Die multikulturelle Bereicherung hat inzwischen auch einen der letzten Horte der Freiheit erreicht, die Skigebiete. Im österreichischen Mayerhofen gingen beim Après-Ski zwölf Türken u.a. mit Schlagringen, Messern und einer zerbrochenen Flasche auf sieben Niederländer los.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/multikulturelle-bereicherung-zum-apres-ski/#more-117806

Türke

Mordversuch

„Ich hab halt einfach zugestochen“

http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/justiz/0,1518,676782,00.html

Da können sie sich wohl vor allem bei ihren Landsleuten bedanken ...

Bewerber-Diskriminierung

Tobias wirft Serkan aus dem Rennen

Von Christoph Titz

Und ist der Lebenslauf noch so toll – klingt ein Name türkisch, haben Jobbewerber schlechtere Chancen. Forscher haben Namenslotto mit fiktiven Studenten gespielt. Sie bestätigen, was immer vermutet wurde: Tobias und Dennis bekommen meist das Praktikum, Serkan und Fatih gehen oft leer aus.

http://www.spiegel.de/unispiegel/jobundberuf/0,1518,676649,00.html

Vorurteil? Vorurteil!

Von Karlheinz Weißmann

„Und ist der Lebenslauf noch so toll – klingt ein Name türkisch, haben Jobbewerber schlechtere Chancen.“ Wir glauben es der jüngsten „Spiegel“-Ausgabe, – unbesehen. Ein aufwendiges „Namenslotto“ mit fiktiven Bewerbungsunterlagen, fiktiven Zeugnissen von fiktiven Studenten, die sich um ein Praktikum in einem realen Unternehmen bemühen und trotz gleichartiger Leistungen verschieden behandelt wurden.

http://www.sezession.de/11849/vorurteil-vorurteil.html#more-11849

Bewährung für Straftat in der Bewährung

Eigentlich können sie machen, was sie wollen, so lange ein Migrations- und kein rechtsradikaler Hintergrund vorliegt. Wegen mehrfacher Körperverletzung in der Bewährungszeit wurde jetzt ein türkischer Hatz IV-Empfänger vom Amtsgericht Dortmund (Foto) erneut zu einer Bewährungsstrafe verurteilt. Der Richter hob aber drohend den Zeigefinger.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/bewaehrung-fuer-straftat-in-der-bewaehrung/

NRW: Schöffe bestätigt Migrantenbonus

PI hat unzählige Male über den Mythos des Migrantenbonus berichtet. Von den Gutmenschen stets vehement bestritten, wird nun das Offensichtliche sehr rasant immer offensichtlicher. Ein Schöffe aus Nordrhein-Westfalen hat sich in einer mehr als eindrucksvollen E-Mail an den Bestsellerautor Udo Ulfkotte gewandt. Lesen Sie auch bei PI, was Udo Ulfkotte diesbezüglich geschildert wurde.

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/nrw-schoeffe-bestaetigt-migrantenbonus/

Migrationsbericht

Statistik – Mehr Abwanderung als Zuzug

(Böhmer sieht Zuwanderung als wirtschaftlichen „Gewinn“)

http://www.focus.de/politik/weitere-meldungen/migrationsbericht-statistik-mehr-abwanderung-als-zuzug_aid_476800.html

Wulff will neuerdings wohl Armin Laschet Konkurrenz machen ...

Migranten

Wulff fordert mehr Zuwanderer in deutschen Firmen

Niedersachsens Ministerpräsident Christian Wulff hat sich dafür ausgesprochen, daß deutsche Firmen mehr Zuwanderer einstellen sollen. „Es muß uns gelingen, auch ohne Quote den Anteil von Migranten zu erhöhen“, sagte der CDU-Politiker. Die Türkische Gemeinde in Deutschland sieht dies anders.

http://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article5972271/Wulff-fordert-mehr-Zuwanderer-in-deutschen-Firmen.html

Ismail Tipi wird erster türkischstämmiger CDU-Landtagsabgeordneter Hessens

„Kenne Wünsche der Migranten“

http://www.op-online.de/nachrichten/heusenstamm/kenne-wuensche-migranten-613285.html

Nach Text zu Minarettverbot

Linke: CDU-Abgeordneter Irmer ein „Haßprediger“

http://www.faz.net/s/Rub5785324EF29440359B02AF69CB1BB8CC/Doc~E526283E3CBBB4841966F4D8F5812DA8F~ATpl~Ecommon~Scontent.html?rss_googlenews

Angst vor Rockerkrieg

Die Polizei rechnet mit Racheakten nach Wechsel von Bandidos zu Hells Angels

Der Wechsel des Bandido-Unterstützer-Clubs „El Centro“ zu den verfeindeten Hells Angels hat in der Szene für Verwirrung gesorgt und am Sonnabend die Polizei auf den Plan gerufen. Ein Großaufgebot von Beamten kontrollierte ab 18 Uhr mehr als 280 „Höllen-Engel“ in Alt-Hohenschönhausen. Unter ihnen befanden sich auch der bisherige Anführer von „El Centro“ und ein Begleiter. Diese beiden hatten wie berichtet mit knapp 80 Angehörigen ihrer Bruderschaft in der vergangenen Woche die Seiten gewechselt. Anführer der Hells Angels hatten am Sonnabend zu einer Sitzung am Vereinshaus ihres Unterstützer-Clubs „Brigade 81“ an der Gärtnerstraße geladen. Dabei sollte es um die neue Situation und um Risikoabwägungen gehen.

Denn nicht alle Hells Angels sind nach Aussagen eines Ermittlers glücklich über die neue Entwicklung. In Polizeikreisen heißt es: „Diese Rocker haben ihre Aufnahmekriterien stets restriktiv durchgesetzt, Ausländer wurden nicht aufgenommen. Mit dem Übertritt der ehemaligen Bandidos-Unterstützer haben sie gleich eine Vielzahl von Türken in den eigenen Reihen.“ Zudem müsse jetzt jederzeit mit Racheakten der alteingesessenen Bandidos gerechnet werden. Darauf bereiten sich offenbar auch die Hells Angels vor – bei dem Einsatz in Alt-Hohenschönhausen wurden Brechstangen, Teleskopschlagstöcke, Äxte und Axtstiele, Quarzhandschuhe und Pfefferspray sichergestellt.

http://www.welt.de/die-welt/regionales/article6297568/Angst-vor-Rockerkrieg.html

http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/justiz/0,1518,675823,00.html

Paris

Posträuber kamen im Ganzkörperschleier

http://derstandard.at/1263706915410/Postraeuber-kamen-im-Ganzkoerperschleier

Alltagswahnsinn, britisch

Von Michael Paulwitz

Wer bei der Lektüre heimischer Gazetten glaubt, der alltägliche politisch korrekte und Multikulti-Irrsinn wäre nicht mehr zu toppen, der werfe gelegentlich mal einen Blick in die englische Boulevardpresse. In „Daily Mail“ zum Beispiel war gestern die groteske Geschichte des griechisch-zypriotischen Grundschullehrers Nicholas Kafouris zu lesen.

http://www.sezession.de/11881/alltagswahnsinn-britisch.html#more-11881

How Labour threw open doors to mass migration in secret plot to make a multicultural UK

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1249797/Labour-threw-open-doors-mass-migration-secret-plot-make-multicultural-UK.html

http://www.pi-news.net/2010/02/blairs-multikulti-politik-war-kampf-gegen-rechts/

Ärtzin entschuldigt sich nach Wirbel um „Cihad“

http://www.focus.de/panorama/welt/gesellschaft-aertzin-entschuldigt-sich-nach-wirbel-um-und132cihadund147_aid_477303.html

Bundesweite Razzia

Ermittler durchsuchen Wohnungen von Islamisten

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/0,1518,675741,00.html

Kontakte zu Sauerland-Gruppe?

Gericht bestätigt Ausweisung von Haßprediger Sadat

http://www.faz.net/s/Rub8D05117E1AC946F5BB438374CCC294CC/Doc~EA8FC9730674E496792483A31C86A8472~ATpl~Ecommon~Scontent.html?rss_googlenews

http://www.op-online.de/nachrichten/offenbach/offenbach-darf-imam-ausweisen-618714.html

Verhandlungen abgebrochen

Einigung über Hamburger Schulreform geplatzt

Von Jochen Leffers

Abbruch in der sechsten Runde: Die Verhandlungen über die Schulreform in Hamburg sind gescheitert, der schwarz-grüne Senat und Reformgegner fanden keinen Kompromiß. Damit dürfte es im Sommer zum Volksentscheid kommen – in einem bundesweit bisher beispiellosen Schulkampf.

http://www.spiegel.de/schulspiegel/wissen/0,1518,676103,00.html

Neukuhren soll Moskau entlasten

In Pionerskij, dem ehemaligen Neukuhren, wird eine Residenz der russischen Zentralregierung gebaut. Als deren Fundment dienen die Reste eines so genannten Bismarckhauses.

http://www.koenigsberger-express.com/main/show_artikel.php?id=2050&kat=6&PHPSESSID=452f50112656d243970ed1ce7372d440

Welch Wunder: Die Russen sind Europäer. Vom Gegenteil waren wohl nur Napoleon und Hitler überzeugt ...

Wie viele europäische Gene stecken im Russen?

Von Manfred Quiring

Im Moskauer Kurtschatow-Institut hat man sein Erbgut entschlüsselt – Tataren-Erbe geringer als erwartet

http://www.welt.de/die-welt/wissen/article6328010/Wie-viele-europaeische-Gene-stecken-im-Russen.html

Die Sentinelesen – das isolierteste Volk der Welt

„Man kann nicht so tun, als gäbe es sie nicht“

Mit dem Tod der letzten Angehörigen ist nun der Stamm der Bo auf der indischen Inselkette Andamanen ausgestorben. Die Bo waren ein Unterstamm des Großen-Andamanesen-Stamms, der einmal aus zehn Untergliederungen bestand und zu dem auch die Sentinelesen gehören.

http://www.faz.net/s/RubCD175863466D41BB9A6A93D460B81174/Doc~EACBD0D488D1F4E5AACE4FA58DC1F8AE6~ATpl~Ecommon~Scontent.html

Zetazeroalfa – Nella mischia

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bXGlEz1T8f4&feature=related

Casapound Italia

http://www.casapounditalia.org/

JF-Interview mit der Musikerin Dee Ex ...

„Ich habe die Freiheit gewählt“

Von Moritz Schwarz

http://www.jungefreiheit.de/Single-News-Display.154+M5cf2873145a.0.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BsN72OyUwxk&feature=PlayList&p=834B04231ED4A176&index=0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fF7IWB1u2k

Skurriles aus dem Orient ...

Vereinigte Arabische Emirate

Diplomat annulliert Ehe mit verschleierter Braut

Ein arabischer Botschafter hat unmittelbar nach seiner Hochzeit die Scheidung eingereicht, weil er sich durch den Gesichtsschleier seiner Braut getäuscht sah. Beim ersten Kuß habe er festgestellt, daß sie im Gesicht stark behaart sei und schiele, berichtete die emiratische Zeitung „Gulf News“. Vor einem Scharia-Gericht in Dubai machte der Diplomat geltend, die Familie der Braut habe seiner Mutter bei der Eheanbahnung Fotos der Schwester gezeigt.

http://www.welt.de/die-welt/vermischtes/article6343752/Diplomat-annulliert-Ehe-mit-verschleierter-Braut.html

Da es halbwegs glimpflich ausging, darf man auch hier lachen ...

Unfall in Istanbul: Kipplaster rammt Fußgängerbrücke

http://www.spiegel.de/video/video-1043411.html

00:15 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : médias, presse, allemagne, actualité, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 21 février 2010

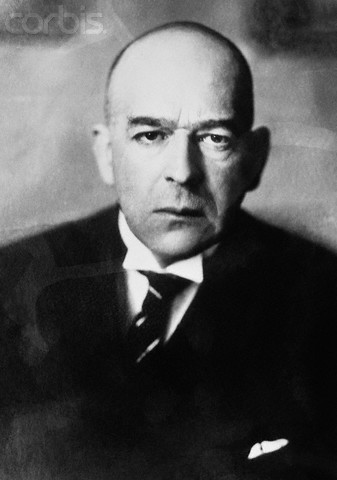

La leçon du philosophe et sociologue Hans Freyer

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1987

La leçon du sociologue et philosophe Hans Freyer

Ex: http://vouloir.hautetfort.com/

Pour Hans Freyer (1887-1969), sociologue allemand néo-conservateur (« jeune-conservateur », jungkonservativ) qui sort du purgatoire où l'on avait fourré tous ceux qui ne singeaient pas les manies de l'École de Francfort ou ne paraphrasaient pas Saint Habermas, la virtù de Machiavel n'est pas une "vertu" ou une qualité statique mais une force qui n'attend qu'une chose : se déployer dans l'aire concrète de la Cité, dans l'épaisseur de l'histoire et du politique. Fondateur de l’École de Leipzig, d’où seront issus les meilleurs cadres de la sociologie historique de Weimar (il est parmi les fondateurs, avec Werner Conze, de la nouvelle histoire sociale allemande), puis de la sociologie nazie et une grande partie des sociologues conservateurs allemands d’après-Guerre (not. Helmuth Schelsky), ce sociologue a une solide formation de philosophe, dont l’ouvrage fondateur, Theorie des objektiven Geistes (1928) qui poursuit les pensées de Hegel et de Wilhelm Dilthey, va préparer le projet sociologique, not. dans son ouvrage Soziologie als Wirklichkeitswissenschaft (1930), d’une « révolution de droite » qui prendrait acte de l’anomie de la société industrielle et de l’échec de la lutte des classes, en lui opposant un État autoritaire. Ayant pris ses distances avec le nazisme – il sera professeur à Budapest entre 1941 et 1945 – il est l’exemple même du penseur conservateur, du théoricien de cette Révolution conservatrice qui aura grand mal à se justifier au moment de la dénazification. Il n’en est pas moins l’un des premiers sociologues professionnels qui, après la mort de Max Weber et de Georg Simmel, dont il ne cesse de se nourrir de manière critique, va lancer des projets innovateurs en sociologie industrielle, des organisations et de l’administration publique.

Pour Hans Freyer (1887-1969), sociologue allemand néo-conservateur (« jeune-conservateur », jungkonservativ) qui sort du purgatoire où l'on avait fourré tous ceux qui ne singeaient pas les manies de l'École de Francfort ou ne paraphrasaient pas Saint Habermas, la virtù de Machiavel n'est pas une "vertu" ou une qualité statique mais une force qui n'attend qu'une chose : se déployer dans l'aire concrète de la Cité, dans l'épaisseur de l'histoire et du politique. Fondateur de l’École de Leipzig, d’où seront issus les meilleurs cadres de la sociologie historique de Weimar (il est parmi les fondateurs, avec Werner Conze, de la nouvelle histoire sociale allemande), puis de la sociologie nazie et une grande partie des sociologues conservateurs allemands d’après-Guerre (not. Helmuth Schelsky), ce sociologue a une solide formation de philosophe, dont l’ouvrage fondateur, Theorie des objektiven Geistes (1928) qui poursuit les pensées de Hegel et de Wilhelm Dilthey, va préparer le projet sociologique, not. dans son ouvrage Soziologie als Wirklichkeitswissenschaft (1930), d’une « révolution de droite » qui prendrait acte de l’anomie de la société industrielle et de l’échec de la lutte des classes, en lui opposant un État autoritaire. Ayant pris ses distances avec le nazisme – il sera professeur à Budapest entre 1941 et 1945 – il est l’exemple même du penseur conservateur, du théoricien de cette Révolution conservatrice qui aura grand mal à se justifier au moment de la dénazification. Il n’en est pas moins l’un des premiers sociologues professionnels qui, après la mort de Max Weber et de Georg Simmel, dont il ne cesse de se nourrir de manière critique, va lancer des projets innovateurs en sociologie industrielle, des organisations et de l’administration publique.

Victor Leemans, qui avant-guerre avec Raymond Aron introduisit en Belgique et en France les grands noms de la sociologie allemande, écrivait, à propos de Hans Freyer, dans son Inleiding tot de sociologie (Introduction à la sociologie, 1938) :

« Pour Freyer, toute sociologie est nécessairement "sociologie politique". Ses concepts sont toujours compénétrés d'un contenu historique et désignent des structures particulières de la réalité. Dans la mesure où la sociologie se limite à définir les principaux concepts structurels de la vie sociale, elle doit ipso facto s'obliger à prendre le pouls du temps. Elle doit d'autant plus clairement nous révéler les successions séquentielles irréversibles où se situent ces concepts et y inclure les éléments de changement, Les catégories sont dès lors telles : communauté, ville, état (Stand), État (Staat), etc., tous maillons dans une chaîne processuelle concrète et réelle. Ces concepts ne sont pas des idéaltypes abstraits mais des réalités liées au temps. (...)

Selon Freyer, aucune sociologie n'est donc pensable qui ne débouche pas dans la connaissance de la réalité contemporaine. À ce concept de réalité ne s'attache pas seulement la connaissance des structures immédiatement perceptibles mais aussi et surtout la connaissance des volontés de maintien ou de transformation qui se manifestent en leur sein. La connaissance sociologique opte nécessairement pour une direction déterminée découlant d'une connaissance de la Realdialektik (dialectique réalitaire [ou dialectique réelle, c'est-à-dire non simplement discursive])... ».

Une sociologie de l'homme total

Malgré cette définition courte de l'œuvre de Freyer, définition qui veut souligner le recours au concret postulé par le sociologue allemand, nous avons l'impression de nous trouver face à un édifice conceptuel horriblement abstrait, détaché de toute concrétude historique. Ce malaise, qui nous saisit lorsque nous sommes mis en présence de l'appareil conceptuel forgé par Freyer, doit pourtant disparaître si l'on fait l'effort de situer ce sociologue dans l'histoire des idées politiques. Avec les romantiques, les jeunes hégéliens (Junghegelianer), Feuerbach et Karl Marx, le XIXe siècle montre qu'il souhaite abandonner définitivement l'homme des humanistes, cet homme perçu comme figure universelle, comme espèce générale dépouillée de sa dimension historico-concrète. Désormais, sous l'influence et les coups de boutoir de ces philosophies concrètes, l'épaisseur historique sera rendue à l'homme : on le percevra comme seigneur féodal, comme serf, bourgeois ou prolétaire.

Une « objectivité » qui doit mobiliser l'homme d'action

Mais ces hégéliens et marxistes, qui dépassent résolument l'idéalisme fixiste de l'humanisme antérieur au XlXe, demeurent mécaniquement enfermés dans la vision de l'homo œconomicus et n'explorent que chichement les autres domaines où l'homme s'exprime. À cette négligence des matérialistes marxistes répond l'hyper-mépris des économismes d'un Wagner ou d'un Schopenhauer, d'un Nietzsche ou d'un Jakob Burckhardt. L'homme total n'est appréhendé ni chez les uns ni chez les autres. Pour Freyer, les essayistes et polémistes anglais Carlyle et John Ruskin nous ont davantage indiqué une issue pour échapper à ce rabougrissement de l'homme. Leurs préoccupations ne les entraînaient pas vers des empyrées légendaires, néo-idéalistes ou spiritualistes mais les amenaient à réfléchir sur les moyens de dépasser l'homme capitaliste, de restituer une harmonie entre le travail et la Vie, entre le travail et la création intellectuelle ou artistique.

Dans deux postfaces aux travaux de Freyer sur Machiavel (ou sur l'Anti-Machiavel de Frédéric Il de Prusse), Elfriede Üner nous explique comment fonctionne concrètement la sociologie de Freyer, qui cherche, au-delà de l'abstractionnisme matérialiste marxiste et de l'abstractionnisme humaniste pré-marxiste, à restaurer l'homme total. Pour parvenir à cette tâche, la sociologie et le sociologue ne peuvent se contenter de décrire des faits sociaux passés ou présents, mais doivent forger des images mobilisatrices tirées du passé et adaptées au présent, images qui correspondent à une volition déterminée, à une volition cherchant à construire un avenir solide pour la Cité.

La méthode de Freyer repose au départ, écrit Elfriede Üner, sur la théorie de "l'esprit objectif" (Theorie des objektiven Geistes). Cette théorie recense les faits mais, simultanément, les coagule en un programme revendicateur et prophétique, indiquant au peuple politique la voie pour sortir de sa misère actuelle. Le sociologue ne saurait donc être, à une époque où le peuple cherche de nouvelles formes politiques, un savant qui fuit la réalité concrète pour se réfugier dans le passé : « Qu'il se fasse alors historien ou qu'il se retire sur une île déserte ! », ironisera Freyer. Cette parole d'ironie et d'amertume est réellement un camouflet à la démarche "muséifiante" que bon nombre de sociologues "en chambre" ne cessent de poser.

Les écrits de sociologie politique doivent donc receler une dimension expressionniste, englobant des appels enflammés à l'action. Ces appels aident à forger le futur, comme les appels de Machiavel et de Fichte ont contribué à l'inauguration d'époques historiques nouvelles. Fichte parlait d'un « devoir d'action » (Pflicht zur Tat). Freyer ajoutera l'idée d'un « droit d'action » (Recht zur Tat). « Devoir d'action » et « droit d'action » forment l'épine dorsale d'une doctrine d'éthique politique (Sittenlehre). L'activiste, dans cette optique, doit vouloir construire le futur de sa Cité. Anticipation constructive et audace activiste immergent le sociologue et l'acteur politique dans le flot du devenir historique. L'activiste, dans ce bain de faits bruts, doit savoir utiliser à 100 % les potentialités qui s'offrent à lui. Cette audacieuse mobilisation totale d'énergie, dans les dangers et les opportunités du devenir, face aux aléas, constitue un "acte éthique".

Une immersion complète dans le flot de l'histoire

L'éthique politique ne découle pas de normes morales abstraites mais d'un agir fécond dans la mouvance du réel, d'une immersion complète dans le flot de l'histoire. L'éthique freyerienne est donc "réalitaire et acceptante". Agir et décider (entscheiden) dans le sens de cette éthique réalitaire, c'est rendre concrètes des potentialités inscrites dans le flot de l'histoire. Freyer inaugure ici un "déterminisme intelligible". Il abandonne le concept de "personnalité esthétisante", individualité constituant un petit monde fermé sur lui-même, pour lancer l'idée d'une personnalité dotée d'un devoir précis, celui de fonctionner le plus efficacement possible dans un ensemble plus grandiose : la Cité. L'éthique doit incarner dans des images matérielles concrètes, générant des actes et des prestations individuels concrets, pour qu'advienne et se déploie l'histoire.

Selon cette vision freyerienne de l'éthique politique, que doit nécessairement faire sienne le sociologue, un ordre politique n'est jamais statique. Le caractère processuel du politique dérive de l'émergence et de l'assomption continuelles de potentialités historiques. Le développement, le changement, sont les fruits d'un déplacement perpétuel d'accent au sein d'un ordre politique donné, c'est-à-dire d'une politisation subite ou progressive de tel ou tel domaine dans une communauté politique. Le développement et le changement ne sont donc pas les résultats d'un "progrès" mais d'une diversification par fulgurations successives [fractales], jaillissant toutes d'une matrice politico-historique initiale. La logique du sociologue et du politologue doit donc viser à saisir la dynamique des fulgurances successives qui remettent en question la statique éphémère et nécessairement provisoire de tout ordre politique.

Une sociologie qui tient compte des antagonismes

Cette spéculation sur les fulgurances à venir, sur le visage éventuel que prendra le futur, contient un risque majeur : celui de voir la sociologie dégénérer en prophétisme à bon marché. Le sociologue, qui devient ainsi "artiste qui cisèle le futur", poursuit, dans le cadre de l'État, l'œuvre de création que l'on avait tantôt attribué à Dieu tantôt à l'Esprit. L'homme, sous l'aspect du sociologue, devient créateur de son destin. Au Dieu des humanistes chrétiens, s'est substitué une figure moins absolue : l'homo politicus... Cette vision ne risque-t-elle pas de donner naissance aux pires des simplismes ?

Elfriede Üner répond à cette objection : la reine Rechtslehre (théorie pure du droit) du libéral Hans Kelsen, idole des juristes contemporains et ancien adversaire de Carl Schmitt, constitue, elle aussi, une "simplification" quelque peu outrancière. Elle n'est finalement que repli sur un formalisme juridique qui détache complètement le système logique, constitué par les normes du droit, des réalités sociales, des institutions objectives et des legs de l'histoire. Rudolf Smend, lui, parlera de la "domination" (Herrschaft) comme de la forme la plus générale d'intégration fonctionnelle et évoquera la participation démocratique des dominés comme une intégration continue des individus dans la forme globale que représente l'État.

Cette idée d'intégration continue, que caressent bon nombre de sociaux-démocrates, évacue tensions et antagonismes, ce que refuse Freyer. Si, pour Smend, la dialectique de l'esprit et de l'État s'opère en circuit fermé, Freyer estime qu'il faut dépasser cette situation par trop idéale et concevoir et forger un modèle de système plus dynamique, capable de saisir les fluctuations tragiques d'une ère faite de révolutions. L'idéal d'une intégration totale s'effectuant progressivement ne permet pas de projeter dans la praxis politique des "futurs imaginés" qui soient réalistes : un tel idéal s'abrite frileusement derrière la muraille protectrice d'un absolu théorique.

À droite : utopies passéistes, à gauche : utopies progressistes

La dialectique de l'esprit et du politique (de l'État), c'est-à-dire de l'imagination constructive et des impératifs de la Cité, de l'imagination qui répond aux défis de tous ordres et des forces incontournables du politique, n'a reçu, en ce siècle de turbulences incessantes, que des interprétations insatisfaisantes. Freyer estime que la sociologie organique d'Othmar Spann (1878-1950) constitue une impasse, dans le sens où elle opère un retour nostalgique vers la structuration de la société en états (Stände) avec hiérarchisation pyramidale de l'autorité. Cette autorité abolirait les antagonismes et évacuerait les conflits : ce qui indique son caractère finalement utopique. À "gauche", Franz Oppenheimer élabore une sociologie "progressiste" qui évoque une succession de modèles sociaux aboutissent à une société sans classes et sans plus aucun antagonisme : cet espoir banal des gauches s'avère évidemment utopique, comme l'ont indiqué quantité de critiques et de polémistes étrangers à ce messianisme. Freyer renvoie donc dos à dos les utopistes passéistes de droite et les utopistes progressistes de gauche.

Ces systèmes utopiques sont "fermés", signale Freyer longtemps avant Popper, et trahissent ipso facto leur insuffisance fondamentale. Les concepts scientifiques doivent demeurer "ouverts" car l'acteur politique injecte en eux, par son action concrète et par son expérience existentielle, la quintessence innovante de son époque. Freyer privilégie ici l'homo politicus agissant, le sujet de l'histoire. Les acteurs politiques, dans l'optique de Freyer, façonnent le temps.

L'idée essentielle de Freyer en matière de sociologie, c'est celle d'une construction pratique ininterrompue de la réalité [les époques sont en relation les unes aves avec les autres dans la dynamique de la continuité historique]. Aux époques politiquement instables, les normes scientifiques (surtout en sciences humaines) sont décrétées obsolètes ou doivent impérativement subir un aggiornamento, une re-formulation. L'histoire est, par suite, un chantier où œuvrent des acteurs-artistes qui, à la façon des expressionnistes, recréent des mondes à partir du chaos, de ruines. Freyer, écrit Elfriede Üner, glorifie, un peu mythiquement, l'homme d'action.

Le peuple (Volk) est le dépositaire de la virtù

Le personnage de Machiavel, analysé méthodiquement par Freyer, a projeté dans l'histoire des idées cette notion expressionniste/ créatrice de l'action politico-historique. Le concept machiavelien de virtù, estime Freyer, ne désigne nullement une "vertu morale statique" mais représente la force, la puissance de créer un ordre politique et le maintenir. Virtù recèle dès lors une qualité "processuelle", écrit Elfriede Üner. Par le biais de Machiavel, Freyer introduit, dans la science sociologique jusqu'alors "objective" et statique à la Comte, un ferment de nietzschéisme, dans le sens où Nietzsche voyait l'existence humaine comme un imperfectum qui ne pouvait jamais être "parfait" mais qu'il fallait sans cesse façonner et travailler.

Le "peuple", dans la vision freyerienne du social et du politique, est, grâce à sa mémoire historique, le dépositaire de la virtù, c'est-à-dire de la "force créatrice d'histoire". Le peuple suscite des antagonismes quand les normes juridiques et/ou institutionnelles ne correspondent plus aux défis du temps, aux impératifs de l'heure ou au ni veau atteint par la technologie. Un système "ouvert" implique de laisser au peuple historique toute latitude pour modifier ses institutions.

Le système freyerien est, en dernière instance, plus démocratique que le démocratisme normatif qui, à notre époque, prétend, sur l'ensemble de la planète, être la seule forme de démocratie possible. Quand Freyer parle de « droit à l'action » (cf. supra), corollaire d'un « devoir éthique d'action », il réserve au peuple un droit d'intervention sur la trame du devenir, un droit à façonner son destin. En ce sens, il précise la vision machiavelienne du peuple dépositaire de la virtù, oblitérée, en cas de tyrannie, par l'arbitraire du tyran individuel ou oligarchique.

Relire Freyer

Relire Freyer, contemporain de Schmitt, nous permet de déployer une critique du normativisme juridique, au nom de l'imbrication des peuples dans l'histoire et du décisionnisme. L'État de droit, c'est finalement un État qui se laisse réguler par la virtù enfouie dans l'âme collective du peuple et non un État qui voue un culte figé à quelques normes abstraites qui finissent toujours par s'avérer désuètes.

Et cette volonté freyerienne de s'imbriquer totalement dans le réel pour échapper aux mondes stérilisés des réductionnismes matérialistes, économistes et caricaturalement normatifs que nous lèguent les marxismes et libéralismes vulgaires, ne pourrait-on pas la lire parallèlement à Péguy ou aux génies de l'école espagnole : Unamuno avec sa dialectique du cœur, Eugenio d'Ors, Ortega y Gasset ?

► Robert STEUCKERS, Vouloir n°37/39, 1987.

1) Hans FREYER, Machiavelli (mit einem Nachwort von Elfriede Üner), Acta Humaniora, Weinheim, IX/133 p.

2) Hans FREYER, Preussentum und Aufklärung und andere Studien zu Ethik und Politik (herausgegeben und kommentiert von Elfriede Üner), Acta Humaniora, Welnheim, 222 p.

¤ Compléments bibliographiques :

- Les Fondements du monde moderne - Théorie du temps présent, H. Freyer, Payot, coll. Bibliothèque scientifique, 1965.

- « Romantisme et conservatisme. Revendication et rejet d'une tradition dans la pensée politique de Thomas Mann et Hans Freyer », C. Roques, in : Les romantismes politiques en Europe, dir. G. Raulet, MSH, avril 2009.

- « Die umstrittene Romantik. Carl Schmitt, Karl Mannheim, Hans Freyer und die "politische Romantik" », C. Roques, in : M. Gangl/ G. Raulet (dir.), Intellektuellendiskurse in der Weimarer Republik. Zur politischen Kultur einer Gemengelage, 2. neubearbeitete und erweiterte Auflage, Frankfurt/M., Peter Lang Verlag 2007 [= Schriftenreihe zur Politischen Kultur der Weimarer Republik, Bd. 10]. [cf. sur ce thème : Les formes du romantisme politique]

- Nationalité et Modernité, D. Jacques, Boréal, Montréal, 1998, 270 p.

- The Other God that Failed : Hans Freyer and the Deradicalization of German Conservatism, J. Z. Muller, Princeton Univ. Press, 1987. Cf. [pt] Reinterpretar Hans Freyer.

- « The Sociological Theories of Hans Freyer : Sociology as a Nationalistic Program of Social Action », Ernest Manheim in : An Introduction to the History of Sociology, H. E. Barnes (éd.), Chicago Univ. Press, 1948.

¤ Citation :

- « Il faut une volonté politique pour avoir une perception sociologique ».

¤ Liens :

- « La sociologie historique en Allemagne et aux États-Unis : un transfert manqué », G. Steinmetz [ref.]

- « De Tönnies à Weber : sur l'existence d'un "courant allemand" en sociologie », S. Breuer

- Die Bewertung der Wirtschaft im philosophischen Denken des 19. Jahrhunderts, H. Freyer (1921)

¤ Évocations diverses :

1) LE CARACTÈRE INHUMAIN DU CAPITALISME : Mais comment se présente plus précisément le capitalisme moderne comme système d’action? Un grand sociologue humaniste du XXe siècle, Hans Freyer, peut nous aider à répondre. Dans son livre Theorie des gegenwärtigen Zeitalters (Théorie de l’époque actuelle, 1956), il parle des "systèmes secondaires" comme de produits spécifiques du monde industrialisé moderne et en analyse la structure avec précision. Les systèmes secondaires sont caractérisés par le fait qu’ils développent des processus d’action qui ne se rattachent pas à des organisations préexistantes, mais se basent sur quelques principes fonctionnels, par lesquels ils sont construits et dont ils tirent leur rationalité. Ces processus d’action intègrent l’homme non comme personne dans son intégralité, mais seulement avec les forces motrices et les fonctions requises par les principes et par leur mise en œuvre. Ce que les personnes sont ou doivent être reste en dehors. Les processus d’action de ce genre se développent et se consolident en un système répandu, caractérisé par sa rationalité fonctionnelle spécifique, qui se superpose à la réalité sociale existante en l’influençant, la changeant et la modelant. Voilà la clé qui permet d’analyser le capitalisme comme système d’action. (S. Magister)

2) En ce qui concerne la tradition sociologique allemande, qui est marquée par l'influence de nombreuses conceptions philosophiques (notamment celles du système de Hegel), elle subit en particulier l'influence néfaste de la distinction opérée par Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911) entre les systèmes de culture (art, science, religion, morale, droit, économie) et les formes «externes» d'organisation de la culture (communauté, pouvoir, État, Église). Cette dichotomie fut encore aggravée par Hans Freyer (1887-1969) qui distinguait les « contenus objectifs » ou « signification devenue forme », qui sont les « formes objectivisées de l'esprit » dont l'étude relève des « sciences du logos », de leurs « être et devenir réels » qui sont l'objet des « sciences de la réalité ». Le caractère insupportablement artificiel de cette opposition ne saurait être mieux démontré qu'en rappelant que dans cette conception, le langage lui-même est défini comme un « assemblage de mots et de significations, de formes mélodiques et de formations syntaxiques », comme si on pouvait appréhender le langage indépendamment de l'organisation sociale des hommes qui l'emploient. Bien entendu, les langues (Langage) présentent aussi des structures intellectuelles qu'on ne peut expliquer par la sociologie sans tomber dans l'erreur du sociologisme; mais ces structures ne constituent que la moitié du problème. En outre, les entités intellectuelles objectives ne peuvent jamais être opposées au devenir social, mais seulement former avec lui une corrélation fonctionnelle dans des complexes d'action culturelle (A. Silbermann). Dilthey lui-même adoptait à cet égard une position radicalement plus ouverte, aussi bien dans ses explications réelles, opposées à son projet, que dans beaucoup d'autres occasions, comme le prouvent ses tentatives pour établir les fondements psychologiques des sciences humaines et ses tentatives périodiques pour mettre sur pied une éthologie empirique (que l'on pourrait également définir comme une science empirique de la culture). Le danger que recèle cette distinction consiste avant tout dans ce qu'elle ouvre la voie à une sorte de distinction hiérarchique à une culture « supérieure », en quelque sorte proche de l'« esprit », et une culture « inférieure » ; celle-ci se confond facilement avec le concept de « civilisation » (matérielle), ce qui introduit dans toute cette approche du problème une évaluation patente. Il semble préférable de passer de ces conceptions fortement teintées de philosophie à une approche plus réaliste. Après la destruction totale de l'ancienne théorie des aires culturelles par l'ethnologie moderne, la dernière possibilité apparente de séparer certains contenus culturels de leurs rapports fonctionnels avec la société a définitivement disparu. (R. König)

3) La conférence « Normes éthiques et politiques » que Freyer a tenue en mai 1929 devant la Kant-Gesellschaft, souligne encore la primauté de l'État [comme fondement de la vie politique] sur le peuple. « L'État est celui qui rassemble et éveille les forces du peuple au service d'un projet culturel caractéristique ; sa politique est le fer de lance dans lequel le peuple devient historique ». Deux ans plus tard [en pleine crise de la République de Weimar], Freyer voit la signification véritable de la « révolution de droite » dans la résolution avec laquelle elle mobilise le peuple contre l'État. Et trois ans plus tard, il est avéré, pour Freyer, « qu'il existe aussi un véritable esprit du peuple en dehors des frontières politiques de l'État-Nation ». L'esprit du peuple, lit-on alors dans un sens tout à fait national-populiste, « doit être autre chose qu'un contexte fondé sur la politique. Le peuple doit être autre chose qu'un rassemblement d'hommes au sein d'un système étatique » (1934). Les singulières variations qui caractérisent la définition par Freyer du rapport de l'État et du peuple sont bien mises en valeur chez Üner (Soziologie als „geistige Bewegung“. Hans Freyers System der Soziologie und die „Leipziger Schule“, 1992). (S. Breuer)

00:05 Publié dans Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : révolution conservatrice, allemagne, années 30, années 40, années 50, philosophie, sociologie, histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 16 février 2010

Nouvelles études sur la guerre des partisans en Biélorussie (1941-1944)

Dag KRIENEN :

Nouvelles études sur la guerre des partisans en Biélorussie (1941-1944)

Deux historiens, Bogdan Musial et Alexander Brakel ont analysé la guerre des partisans contre l’occupation allemande en Biélorussie entre 1941 et 1944

Parmi les mythes appelés à consolider l’Etat soviétique et la notion de « grande guerre patriotique de 1941-45 », il y a celui de la résistance opiniâtre du peuple tout entier contre l’ « agresseur fasciste ». Cette résistance se serait donc manifestée dans les régions occupées avec le puissant soutien de toute la population, organisée dans un mouvement de partisans patriotiques, qui n’aurait cessé de porter de rudes coups à l’adversaire et aurait ainsi contribué dans une large mesure à la défaite allemande.

Après l’effondrement de l’Union Soviétique et avec l’accès libre aux archives depuis les années 90 du 20ème siècle, ce mythe a été solidement égratigné. Pourtant, en Russie et surtout en Biélorussie, la guerre des partisans de 1941-45 est à nouveau glorifiée. Ce retour du mythe partisan a incité l’historien polonais Bogdan Musial à le démonter entièrement. Après avoir publié en 2004 un volume de documents intitulé « Partisans soviétiques en Biélorussie – Vues intérieures de la région de Baranovici 1941-1944 », il a sorti récemment une étude volumineuse sur l’histoire du mouvement partisan sur l’ensemble du territoire biélorusse. Au même moment et dans la même maison d’édition paraissait la thèse de doctorat d’Alexander Brakel, défendue en 2006 et publiée cette fois dans une version légèrement remaniée sur « la Biélorussie occidentale sous les occupations soviétiques et allemandes », ouvrage dans lequel l’histoire du mouvement local des partisans soviétiques est abordé en long et en large.

Ce qui est remarquable, c’est que nos deux auteurs ont travaillé indépendamment l’un de l’autre, sans se connaître, en utilisant des sources russes et biélorusses récemment mises à la disposition des chercheurs ; bien qu’ils aient tous deux des intérêts différents et utilisent des méthodes différentes, ils concordent sur l’essentiel et posent des jugements analogues sur le mouvement des partisans. Tant Musial que Brakel soulignent que le mouvement des partisans biélorusses, bien que ses effectifs aient sans cesse crû jusqu’en 1944, jusqu’à atteindre des dimensions considérables (140.000 partisans au début du mois de juin 1944), n’a jamais été un mouvement populaire au sens propre du terme, bénéficiant du soutien volontaire d’une large majorité de la population dans les régions occupées par les Allemands. Au contraire, la population de ces régions de la Biélorussie occidentale, qui avaient été polonaises jusqu’en septembre 1939, était plutôt bien disposée à l’égard des Allemands qui pénétraient dans le pays, du moins au début.

Jusqu’à la fin de l’année 1941, on ne pouvait pas vraiment parler d’une guerre des partisans en Biélorussie. Certes, les fonctionnaires soviétiques et les agents du NKVD, demeurés sur place, ont été incités depuis Moscou à commencer cette guerre. Mais comme en 1937 le pouvoir soviétique a décidé de changer de doctrine militaire et d’opter pour une doctrine purement offensive, tous les préparatifs pour une éventuelle guerre des partisans avaient été abandonnés : inciter les représentants du pouvoir soviétique demeurés sur place à la faire malgré tout constituait un effort somme toute assez vain. Le même raisonnement vaut pour les activités des petits groupes d’agents infiltrés en vue de perpétrer des sabotages ou de glaner des renseignements d’ordre militaire. Pour créer et consolider le mouvement des partisans en Biélorussie à partir de 1942, il a fallu faire appel à une toute autre catégorie de combattants : ceux que l’on appelait les « encerclés », soit les unités disloquées à la suite des grandes batailles d’encerclement de 1941 (les « Kesselschlachten »), et aussi les combattants de l’Armée Rouge qui s’étaient échappés de captivité ou même avaient été démobilisés ; vu le destin misérable qui attendaient les prisonniers de guerre soviétiques, ces hommes cherchaient à tout prix à échapper aux Allemands. De très nombreux soldats de ces catégories ont commencé à monter dès l’automne 1941 des « groupes de survie » dans les vastes zones de forêts et de marécages ou bien ont trouvé refuge chez les paysans, où ils se faisaient passer comme ouvriers agricoles. Peu de ces groupes ont mené une véritable guerre de partisans, seuls ceux qui étaient commandés par des officiers compétents, issus des unités encerclées et disloquées par l’avance allemande, l’ont fait. La plupart de ces groupes de survie n’avaient pas l’intention de s’attaquer à l’occupant ou de lui résister activement.

Sous la pression de la crise de l’hiver 1941/42 sur le front, les autorités d’occupation allemandes ont pris des mesures au printemps 42 qui se sont révélées totalement contre-productives. Avec des forces militaires complètement insuffisantes, les Allemands ont voulu obstinément « pacifier » les régions de l’arrière et favoriser leur exploitation économique maximale : pour y parvenir, ils ont opté pour une intimidation de la population. Ils ne se sont pas seulement tournés contre les partisans mais contre tous ceux qu’ils soupçonnaient d’aider les « bandes ». Pour Musial, ce fut surtout une exigence allemande, énoncée en avril 1942, qui donna l’impulsion initiale au mouvement des partisans ; cette exigence voulait que tous les soldats dispersés sur le territoire après les défaites soviétiques et tous les anciens prisonniers de guerre se présentent pour le service du travail, à défaut de quoi ils encourraient la peine de mort. C’est cette menace, suivie d’efforts allemands ultérieurs pour recruter par la contrainte des civils pour le service du travail, qui a poussé de plus en plus de Biélorusses dans les rangs des partisans.