Guerre froide « 2.0 » : le coronavirus n’est qu’un prétexte

Éditorial d'Éric Denécé (revue de presse : Centre Français de Recherche sur le Renseignement – mai 2020)*

Ex: https://cf2r.org

Un nouvel ordre mondial, organisé autour d’une nouvelle rivalité stratégique Etats-Unis/Chine structurant les relations internationales, pourrait bien enfin s’esquisser, trente ans après la chute de l’URSS et la fin de la Guerre froide.

L’épidémie du coronavirus a déclenché une crise sanitaire et une crise économique. Elle va également marquer une rupture géopolitique dont les premiers signes sont déjà visibles. Cette rupture se fonde sur deux éléments : l’un faux, l’autre vrai.

Mensonges et provocations américains

La fausse raison de cette évolution internationale majeure est la soi-disant responsabilité chinoise dans la diffusion de la pandémie.

Depuis plusieurs semaines, le Président américain a, à plusieurs reprises, accusé la Chine d’être responsable de la propagation du coronavirus dans le monde. Donald Trump a déclaré, le 30 avril, que le virus proviendrait d’un laboratoire de Wuhan[1]. Les failles de sécurité du laboratoire P4 sont l’occasion au passage, d’égratigner la France. Il a également menacé Pékin de représailles. Le 6 mai 2020, il a déclaré que l’épidémie actuelle, partie de Chine, est la « pire attaque de l’histoire contre les États-Unis, encore pire que Pearl Harbor ou les attentats du 11 septembre 2001 ». Trump a de nouveau critiqué Pékin pour avoir laissé le virus quitter le pays et considère que la Chine constitue « la menace géopolitique la plus importante pour les Etats-Unis pour le siècle à venir ».

Le chef de la diplomatie américaine, Mike Pompeo, n’a pas pris de gants non plus pour faire monter d’un cran supplémentaire l’escalade verbale à l’encontre de Pékin[2]. « Il existe des preuves immenses que c’est de là que c’est parti », a déclaré le secrétaire d’Etat sur la chaîne ABC, à propos de l’Institut de virologie de Wuhan. « Ce n’est pas la première fois que la Chine met ainsi le monde en danger à cause de laboratoires ne respectant pas les normes », a-t-il ajouté. Il a également dénoncé le manque de coopération des responsables chinois afin de faire la lumière sur l’origine exacte de la pandémie : « Ils continuent d’empêcher l’accès aux Occidentaux, aux meilleurs médecins », a-t-il dit sur ABC. « Il faut que nous puissions aller là-bas. Nous n’avons toujours pas les échantillons du virus dont nous avons besoin ».

Le secrétaire d’État a déclaré que le gouvernement Chinois avait fait tout ce qu’il pouvait « pour s’assurer que le monde ne soit pas informé en temps opportun » sur le virus. Il a déclaré à ABC que le Parti communiste chinois s’était engagé dans un « effort classique de désinformation communiste » en faisant taire les professionnels de la santé et en muselant les journalistes pour limiter la diffusion d’informations sur le virus.

Ces attaques ont été appuyées par diverses productions gouvernementales falsifiant également la réalité dans le même sens, afin de donner corps à la réalité que la Maison-Blanche souhaite diffuser et imposer.

Selon l’Associated Press, un rapport de quatre pages du Département de la sécurité intérieure (DHS) accuse le Chine de n’avoir pas divulgué des informations sur le virus afin de mieux préparer sa réponse à la pandémie. Ce document indique que Pékin a diminué ses exportations et accru ses importations de fournitures médicales en janvier, ce qui incite le DHS à conclure « avec une certitude de 95% » que ces changements dans les importations de produits médicaux ne sont pas normaux.

De même, un rapport affirmant être une production des Five Eyes[3] – ce qui a été démenti -, publié par le Daily Star[4] britannique, avance que la Chine a sciemment détruit des preuves sur l’origine du coronavirus. Selon le journal, le document de quinze pages indique que le gouvernement chinois a fait taire ou « disparaître » les médecins s’étant exprimé sur le sujet, et a refusé de partager des échantillons avec la communauté scientifique internationale. Le dossier également affirme que le virus a été divulgué à l’Institut de virologie de Wuhan fin 2019.

L’analyse des services de renseignement

Les déclarations du président et de son secrétaire d’Etat sont contredites par l’analyse des services de renseignement américains. Ces derniers ont annoncé être parvenus à la conclusion que le Covid-19 n’avait pas été créé ou modifié génétiquement par l’homme. Toutefois, ils ne disposent pas d’informations suffisantes « pour déterminer si l’épidémie a commencé par un contact avec des animaux infectés ou si elle a été le résultat d’un accident de laboratoire à Wuhan ».

Les informations partagées entre les services de renseignement des Five Eyes les conduisent à conclure qu’il est “hautement improbable” que l’épidémie de coronavirus se soit propagée à la suite d’un accident dans un laboratoire, mais plutôt sur un marché chinois. « Il est très probable qu’elle se soit produite naturellement et que l’infection humaine soit due à une interaction naturelle entre l’homme et l’animal » [5].

En France, l’hebdomadaire Valeurs actuelles rapporte que de nombreuses sources qu’il a interrogées fin avril dans les services de renseignement français (spécialistes du contre-espionnage ou des armes chimiques et bactériologiques) sur l’origine du coronavirus, ont l’absolue certitude que ce n’est pas une fuite du laboratoire P4. « Toutes les souches analysées montrent qu’elles n’ont pas été modifiées humainement. La souche est bien animale, elle a été transmise à l’homme sans qu’on sache encore exactement pourquoi. Elle ne vient pas d’une fausse manipulation ou d’une fuite ».

Le rédacteur en chef de la revue médicale The Lancet est également intervenu pour réfuter les allégations fallacieuses des autorités américaines. L’attribution à une origine humaine du virus est écartée par tous les virologues sérieux. Il a insisté sur l’intérêt des publications chinoises en la matière, riches en données.

Toutefois, les attaques mensongères de l’administration américaine n’exonèrent pas les autorités chinoises d’un certain nombre d’erreurs et de dissimulations.

Erreurs et responsabilités de la Chine

Indéniablement, les autorités chinoises – dans un premier temps à Wuhan et dans un second temps à Pékin – ont tardé à réagir et à communiquer, voire ont eu tendance à minimiser l’épidémie. Pour cette raison, Pekin fait l’objet de nombreuses critiques internationales. Mais concédons-là qu’il est facile de juger après coup. Cette épidémie est nouvelle et sa rapidité de diffusion semblait difficile à anticiper.

Toutefois, après avoir initialement dissimulé la gravité de l’épidémie, face aux soupçons, au lieu de jouer la carte de la transparence, le gouvernement chinois a déchaîné sa propagande contre ceux qui osaient critiquer sa version officielle et n’a pas hésité à faire la leçon à aux pays occidentaux sur leur propre gestion de l’épidémie. Cette attitude a braqué contre la Chine la majorité des Etats occidentaux et des voix se sont élevées pour réclamer une enquête de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé sur l’origine du virus, ce qu’a refusé Pékin, de même qu’il a refusé de participer aux financements lors des réunions de donateurs pour lutter mondialement contre l’épidémie.

Toutefois, après avoir initialement dissimulé la gravité de l’épidémie, face aux soupçons, au lieu de jouer la carte de la transparence, le gouvernement chinois a déchaîné sa propagande contre ceux qui osaient critiquer sa version officielle et n’a pas hésité à faire la leçon à aux pays occidentaux sur leur propre gestion de l’épidémie. Cette attitude a braqué contre la Chine la majorité des Etats occidentaux et des voix se sont élevées pour réclamer une enquête de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé sur l’origine du virus, ce qu’a refusé Pékin, de même qu’il a refusé de participer aux financements lors des réunions de donateurs pour lutter mondialement contre l’épidémie.

En revanche, la Chine s’est attachée à fournir une aide à de nombreux pays dans un cadre systématiquement bilatéral, cherchant par ce biais à donner une image de puissance « aidante », mais sans parvenir à tromper personne sur le jeu d’influence se cachant derrière cette manœuvre. En agissant ainsi, la Chine s’est attirée des critiques redoublées.

Ainsi, l’hostilité au régime chinois a atteint un niveau sans précédent depuis la répression sanglante du mouvement étudiant de Tiananmen en 1989 et pourrait avoir de lourdes conséquences diplomatiques. Les pressions dont la Chine fait l’objet n’émanent pas uniquement des Etats-Unis. Elles sont exercées aussi par l’Australie, le Japon, les pays d’Asie et l’Union européenne. Tous demandent des comptes tant les éléments s’accumulent prouvant que le régime chinois a dissimulé, au départ, l’étendue de l’épidémie.

Réalité de la menace chinoise

Toutefois, la véritable raison de la virulence de la réaction américaine contre la Chine est ailleurs. Et elle est double. D’une part, Washington ne cesse de s’inquiéter depuis plusieurs années de la montée en puissance de ce nouvel adversaire stratégique en passe de remettre en cause son leadership ; d’autre part, afin de relancer leur économie, de relocaliser une part de leur production industrielle et de consolider autour d‘eux le camp occidental, les Etats-Unis ont besoin d’une nouvelle Guerre froide.

Si une partie des arguments employés par Washington contre Pékin sont fallacieux, force est de constater qu’il y a de très nombreuses raisons de s’inquiéter sérieusement du développement continu de la puissance chinoise depuis la fin de la Guerre froide.

– La Chine est devenue l’usine du monde en matière d’informatique, d’électronique, de médicaments, de textile, etc. Si tout le monde en avait conscience, la crise récente via les pratiques de confinement et l’interruption des transports internationaux a permis au monde occidental de mesurer à quel point il était dépendant de Pékin. Les délocalisations à outrance vers la Chine et les pays à faible coût de main d’œuvre ont profondément affaibli la résilience de nos économies et de nos systèmes de santé, ce qui n’est pas acceptable et doit être corrigé. La crise a également permis de mesurer la flexibilité, l’efficacité et la réactivité industrielle de la Chine, ce dont l’Occident n’est plus capable.

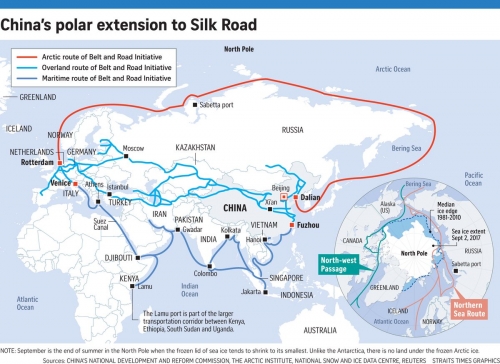

– Depuis de nombreuses années, la Chine, dans la cadre de son projet des Nouvelles routes de la soie, s’implante dans le monde entier, par des investissements massifs dans les infrastructures – ne reculant jamais devant la corruption des autorités locales – et via le rachat de très nombreuses entreprises, y compris au sein de l’Union européenne. Ces nombreuses acquisitions d’entreprises occidentales laissent entrevoir une stratégie insidieuse de prise de contrôle de nos actifs économiques, donc d’une nouvelle dépendance.

– Les progrès réalisés – voire l’avance prise – en matière technologique par les Chinois – résultat de leur volonté, de leurs capacités financières, humaines et technologiques – notamment en matière militaire (5G, missiles hypersoniques, porte-avions, satellites, lanceurs, etc.) ne cesse d’impressionner et engendre une vraie préoccupation en matière de sécurité.

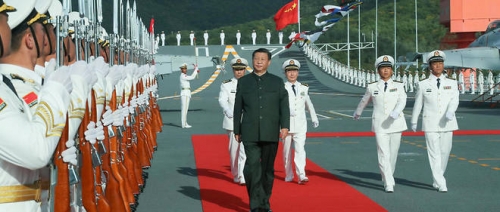

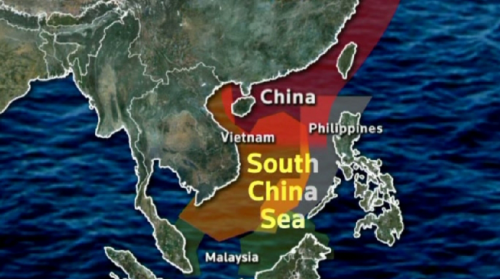

– La puissance militaire chinoise ne cesse en effet de se développer[6] et l’épidémie de Covid-19 n’a pas ralenti le rythme d’équipement des forces armées en nouveaux matériels offensifs : courant avril, un navire d’assaut amphibie (type 075) est entré en service et deux nouveaux sous-marins nucléaires lanceurs d’engins (SNLE) (type 094) ont été mis à l’eau, donnant à la marine chinoise une véritable capacité de dissuasion océanique, ce qui n’était pas le cas avec les submersibles précédents (type 092). Par ailleurs, une autre classe de SNLE (type 096), encore plus moderne, capable d’embarquer un nouveau missile balistique de 10 000 km de portée, est en cours de développement. A noter également que les manoeuvres autour de Taïwan se sont poursuivies, de même que celles en mer de Chine méridionale.

– Les services de renseignement chinois se montrent particulièrement agressifs partout dans le monde occidental, tant par leurs actions de cyberespionnage que par le développement de leurs infrastructures clandestines et leurs tentatives de recrutement d’agents.

– Pékin continue à étouffer la vie démocratique sur son territoire et a profité de la crise pour remettre Hong-Kong au pas. La Chine ne supporte plus l’exception hongkongaise, tant sur le plan politique qu’économique. En effet, l’ex-colonie britannique joue un rôle essentiel comme porte d’entrée et de sortie pour les capitaux chinois. La bourse de Hong-Kong accueille les plus grandes entreprises chinoises, et nombre des familles les plus riches y ont une partie de leur fortune. Pékin a procédé à un coup de force discret, passant outre son engagement de non-ingérence dans les affaires intérieures de Hong-Kong[7] et a arrêté une quinzaine de leaders pro-démocratie.

– N’oublions pas, par ailleurs, que la Chine occupe toujours, en contravention avec le droit international de la mer, des îlots de mer de Chine méridionale – dont certains conquis par la force sur ses voisins – sur lesquels elle a construit d’importantes installations militaires[8].

– Surtout, rappelons que la République populaire de Chine n’est pas une démocratie et que son peuple n’y exprime jamais son point de vue librement à travers des élections, qu’il ne bénéficie pas d’un état de droit ou d’une presse libre. Le pays reste sous le contrôle étroit du Parti communiste, lui-même aux mains d’un véritable autocrate et de sa clique d’affidés. Si les Etats-Unis doivent être critiqués depuis trois décennies pour leur politique étrangère unilatérale aux effets parfois dévastateurs (Irak, « révolutions » arabes, etc.), il serait encore plus inquiétant pour la paix et la sécurité mondiales que la puissance dominante soit un Etat totalitaire ne pouvant être remis en cause par des élections, une opposition interne ou un mouvement citoyen.

La stratégie américaine : relancer une guerre froide

La crise engendrée par l’épidémie de Covid-19 est donc le prétexte qu’ont choisi les Américains pour attaquer Pékin et contrecarrer ou ralentir le développement de sa puissance économique et militaire.

Depuis fin avril, outre-Atlantique, articles de presse, témoignages de spécialistes et déclarations d’autorités se multiplient, avançant que Pékin est responsable et qu’il doit payer. Le ton ne cesse de se durcir et les menaces de prendre forme.

Ce thème va à n’en pas douter occuper dans les mois qui viennent une part croissante de l’actualité internationale, car les élections américaines approchent et que ce thème est une aubaine pour Donald Trump, comme pour l’Intelligence Community ; les deux pourraient bien ainsi se réconcilier sur le dos de Pékin.

Les sanctions contre la Chine

Depuis le début de la pandémie, Donald Trump s’en est pris à la Chine, l’accusant d’avoir considérablement affaibli l’économie américaine. C’est donc en ce domaine qu’il a décidé en premier lieu de réagir. Le président américain a déclaré que de nouveaux tarifs sur les importations chinoises seraient la “punition ultime” pour les déclarations erronées de Pékin sur l’épidémie de coronavirus.

Trump a qualifié les tarifs de “meilleur outil de négociation” et a insisté sur le fait que les droits que son administration avait imposés jusqu’à présent, ont obligé la Chine à conclure un accord commercial avec Washington. Il a également menacé de résilier cet accord si la Chine n’achetait pas de marchandises aux États-Unis comme cela avait prévu, voire de procéder à l’annulation des avoirs chinois investis dans la dette américaine. Donald Trump a également récemment évoqué la possibilité de demander à Pékin de payer des milliards de dollars de réparations pour les dommages causés par l’épidémie.

Pression sur les Alliés

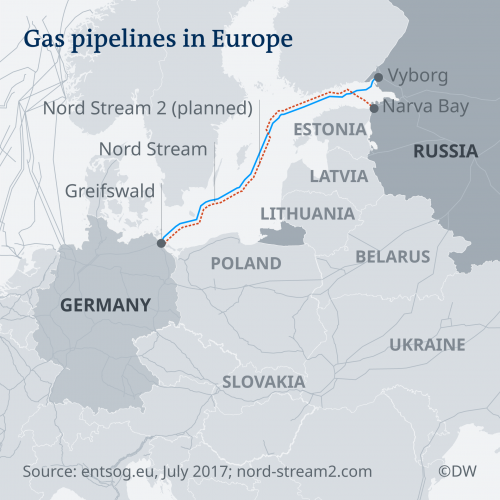

Parallèlement, les Américains accroissent la pression sur leurs alliés européens, tentés par l’adoption de la 5G chinoise où déjà engagés dans son déploiement.

A l’occasion du sommet de l’OTAN, à Londres, en décembre 2019, les Européens, ont assuré Washington de leur engagement à « garantir la sécurité de leurs communications, y compris la 5G, conscients de la nécessité de recourir à des systèmes sécurisés et résilients. » Or, en dépit des recommandations de l’OTAN et des pressions américaines, le gouvernement britannique a autorisé, en janvier, l’opérateur chinois Huawei à mettre en place des réseaux de télécommunication 5G au Royaume-Uni.

Pour Washington, « Huawei comme les autres entreprises technologiques chinoises soutenues par l’État, sont des chevaux de Troie pour l’espionnage chinois », a déclaré Mike Pompeo, lors de la Conférence de Munich sur la sécurité, en février 2020.

En conséquence, Washington a laissé entendre, début mai, que ses moyens de collecte de renseignements électroniques actuellement basés au Royaume-Uni, pourraient être redéployés dans un autre pays européen ayant choisi de ne pas adopter la 5G chinoise. De plus, les Américains laissent planer une menace concernant l’avenir de la base de Menwith Hill, pièce maitresse du réseau Echelon, où ils disposent d’une station terrestre de communication par satellite et d’installations d’interception exploitées en coopération avec les Britanniques. The Telegraph prête même à la Maison-Blanche l’idée de retirer jusqu’à 10 000 militaires américains du Royaume-Uni[9].

Le nouveau concept stratégique de l’OTAN

Le ciblage de la Chine permet par ailleurs à Washington de préparer les états-majors et les opinions publiques occidentales à la réactualisation du concept stratégique de l’OTAN, en cours de préparation. Le fait de désigner Pekin comme l’adversaire potentiel principal devrait être accepté par les Etats membres sous l’effet du choc de la pandémie et de ses conséquences. En revanche, le fait d’inscrire également la Russie comme autre menace majeure contre l’Alliance atlantique serait une double erreur. D’une part, car Moscou n’est en rien une menace, contre l’Europe. Il est important de ne pas se laisser influencer par l’obsession antirusse des élites américaines. Rappelons à ce titre les propos pertinents du document du Cercle de réflexion interarmées (CRI) à l’approche des prochains exercices militaires aux frontières de la Russie : « organiser des manœuvres de l’OTAN, au XXIe siècle, sous le nez de Moscou, plus de 30 ans après la chute de l’URSS, comme si le Pacte de Varsovie existait encore, est une erreur politique, confinant à la provocation irresponsable ». Pour la France, « y participer révèle un suivisme aveugle, signifiant une préoccupante perte de notre indépendance stratégique »[10].

D’autre part, une telle décision aurait pour effet de jeter Moscou dans les bras de la Chine, ce qui aurait des conséquences désastreuses. Malheureusement, de nombreux éléments laissent craindre le pire, les Américains – si personne ne leur tient tête sur ce point – en sont tout à fait capables, confirmant leur penchant à jouer les apprentis-sorciers… dont les créations se retournent généralement contre eux.

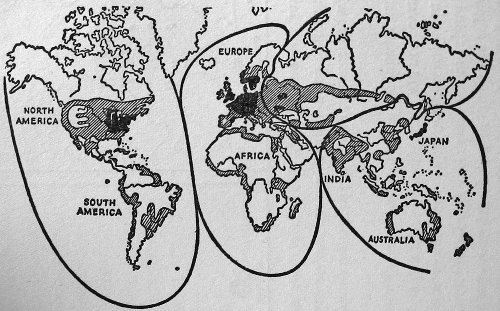

Cibler la Chine peut avoir un intérêt stratégique pour revitaliser l’Alliance occidentale et il est très probable que tous ses membres y adhèrent, car cela a du sens sur les plans stratégique et économique. Un « élargissement » de l’OTAN à certains ex-pays de l’OTASE[11] partageant cette analyse de la menace, ainsi qu’au Japon et à la Corée du Sud, pourrait même être envisageable. En revanche, cibler la Russie serait contre-productif et ferait du continent européen un nouveau théâtre de Guerre froide, sans raison valable. Il est essentiel que nous ne nous trompions pas d’adversaire et que les Européens infléchissent le concept stratégique de l’OTAN.

La crise du coronavirus est une aubaine stratégique pour les États-Unis. Elle leur offre l’opportunité de se recréer un adversaire stratégique à la hauteur de leurs besoins. Une adversité majeure est pour eux indispensable afin de conserver leur leadership, relancer leur économie et consolider autour d’eux le camp occidental.

Observer les Américains falsifier une nouvelle fois la réalité pour réaffirmer leur leadership n’est guère rassurant mais pas surprenant. Les voir relancer une stratégie de tension, voire une nouvelle guerre froide, non plus. Cependant, en l’occurrence, leur décision est loin d’être infondée.

Jusqu’à la récente crise sanitaire, l’idée que le monde pourrait entrer dans une nouvelle ère d’affrontement semblait saugrenue ; les avoirs financiers des Etats-Unis et de la Chine semblaient si étroitement liés et leurs économies interdépendantes que l’hypothèse d’un conflit apparaissait peu probable[12].

Désormais, tous les signes annonciateurs d’une nouvelle ère géopolitique et d’une nouvelle guerre froide – dont les modalités seront en partie différentes de la précédente – sont là. La rivalité stratégique sino-américaine devrait désormais régir les relations internationales des prochaines décennies sur les plans militaire, économique, financier, technologique et idéologique. Il convient de s’y préparer.

Notes :

[1] https://www.teletrader.com/trump-saw-evidence-virus-origi...

[2] https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/public-global-healt...

[3] Alliance des agences de renseignement des Etats-Unis, du Royaume-Uni, du Canada, d’Australie et de Nouvelle-Zélande.

[4] https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/world-news/top-secret-mi...

[5] https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/04/politics/coronavirus-intel...

[6] Cependant le différentiel des budgets reste énorme : 649 milliards de dollars et 3,2% du PIB pour les Etats-Unis ; 250 milliards de dollars et 1,9% du PIB pour la Chine (SIPRI, 2018).

[7] Principe inscrit dans l’article 22 de la Basic Law reconnue par la Chine.

[8] Cf. Eric Denécé, Géostratégie de la mer de Chine méridionale, L’Harmattan, Paris 1999.

[9] http://www.opex360.com/2020/05/07/les-etats-unis-pourraie...

[10] https://www.capital.fr/economie-politique/il-faut-se-libe...

[11] Organisation du traité de l’Asie du Sud-Est. Alliance militaire anticommuniste, pendant de l’OTAN pour la zone Asie/Pacifique, ayant regroupé de 1954 à 1977, les Etats-Unis, le Royaume-Uni, la France, l’Australie, la Nouvelle-Zélande, le Pakistan, les Philippines et la Thaïlande.

[12] La décision Washington de mettre fin aux investissements des fonds de pension américains en Chine, de limiter les détentions chinoises d’obligations du Trésor et de déclencher une nouvelle guerre des monnaies va rapidement mettre un terme aux liens financiers qui unissaient les deux économies.

*Source : Cf2R

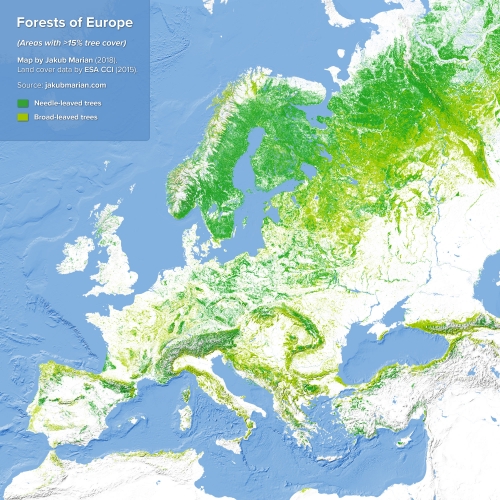

Ever since I was a small child, roughly from age three or four, I remember staring transfixed at any map I could get my hands on. Atlases, globes, wall charts, everything to satisfy my voracious appetite for map-reading. It’s important to not confuse the map for the territory, but a map is a story of the territory, for those who know how to read it. I would scan maps for hours on end, learning to the best of my ability the various geographical features, the names of countries, cities, and capitals. Much of it I still remember even at my embarrassingly advanced age. So, it should come as no surprise to anyone that I was positively giddy when I heard that a book about maps that explain the world exists. And indeed, Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About The World [1] claims that such maps exist.

Ever since I was a small child, roughly from age three or four, I remember staring transfixed at any map I could get my hands on. Atlases, globes, wall charts, everything to satisfy my voracious appetite for map-reading. It’s important to not confuse the map for the territory, but a map is a story of the territory, for those who know how to read it. I would scan maps for hours on end, learning to the best of my ability the various geographical features, the names of countries, cities, and capitals. Much of it I still remember even at my embarrassingly advanced age. So, it should come as no surprise to anyone that I was positively giddy when I heard that a book about maps that explain the world exists. And indeed, Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About The World [1] claims that such maps exist.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

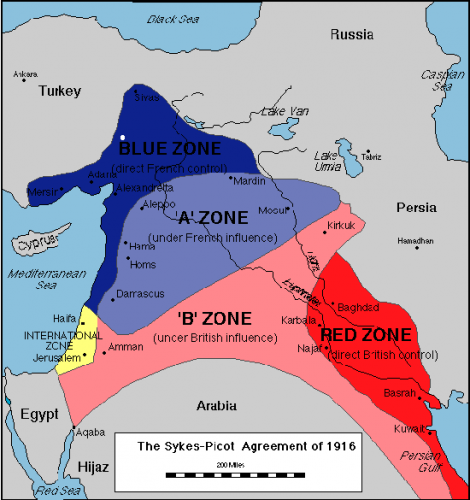

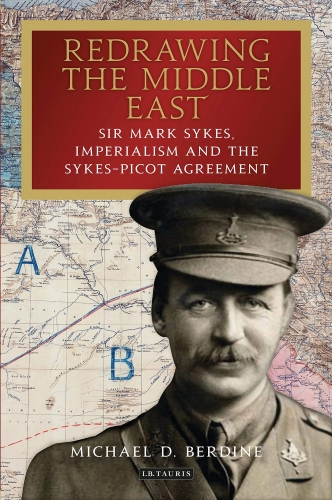

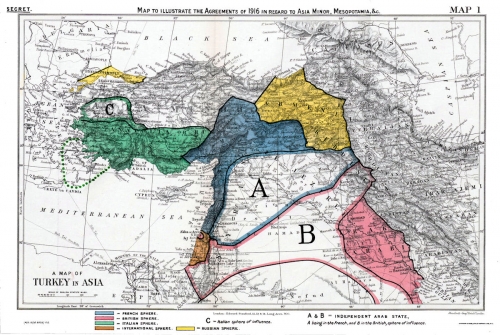

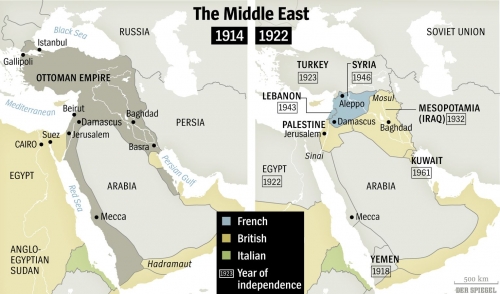

En 1905, Mark Sykes, alors jeune diplomate britannique à Constantinopleiii, a rédigé et transmis un rapport sur les sources affleurantes de pétrole entre Bitlis, Mossoul et Baghdad (Report on the Petroliferous Districts of Mesopotamia), à partir du travail d’un ingénieur allemand engagé par la Liste Civile du Sultan. L’attaché militaire anglais, lui, avait déjà été l’auteur d’un article publié en mai 1897 avec une carte des zones pétrolières en Mésopotamie, et en 1904 il avait pu récupérer une copie de la carte des zones pétrolières récemment dressée par un allemand employé du Syndicat ferroviaire anatolien. Cette prospection allemande était menée dans le cadre légal de la concession de la voie ferrée Konya Bagdad et au-delà vers Bassora, signée en 1902 entre une filiale ferroviaire de la Deutsche Bank et l’Empire Ottoman. Car cette concession allemande lui avait accordé un droit complet de prospection, exploitation et vente de produits miniers, pétrole inclus, sur une bande de 20 km de chaque côté du tracé prévu. L’ambassadeur britannique O’Connor transmit à Londres en soulignant « that many of the springs can be profitably worked before the completion of the Baghdad Railway by mean of pipelines to the sea». Dès 1905 plusieurs visées concurrentes se font jour, envers les ressources pétrolières de Mésopotamie et les voies de transfert.

En 1905, Mark Sykes, alors jeune diplomate britannique à Constantinopleiii, a rédigé et transmis un rapport sur les sources affleurantes de pétrole entre Bitlis, Mossoul et Baghdad (Report on the Petroliferous Districts of Mesopotamia), à partir du travail d’un ingénieur allemand engagé par la Liste Civile du Sultan. L’attaché militaire anglais, lui, avait déjà été l’auteur d’un article publié en mai 1897 avec une carte des zones pétrolières en Mésopotamie, et en 1904 il avait pu récupérer une copie de la carte des zones pétrolières récemment dressée par un allemand employé du Syndicat ferroviaire anatolien. Cette prospection allemande était menée dans le cadre légal de la concession de la voie ferrée Konya Bagdad et au-delà vers Bassora, signée en 1902 entre une filiale ferroviaire de la Deutsche Bank et l’Empire Ottoman. Car cette concession allemande lui avait accordé un droit complet de prospection, exploitation et vente de produits miniers, pétrole inclus, sur une bande de 20 km de chaque côté du tracé prévu. L’ambassadeur britannique O’Connor transmit à Londres en soulignant « that many of the springs can be profitably worked before the completion of the Baghdad Railway by mean of pipelines to the sea». Dès 1905 plusieurs visées concurrentes se font jour, envers les ressources pétrolières de Mésopotamie et les voies de transfert.

En 1901 Théodore Herzl s’était vu refuser par le Sultan la concession coloniale juive en Palestine qu’il réclamait en proposant le rachat de l’écrasante dette ottomane et un crédit de 81 ans. Après avoir obtenu au printemps 1902 d’énormes crédits de 3 grandes banques européennes, Crédit Lyonnais, Dresdner Bank, Lloyds, Herzl retourna à Constantinople et là écrivit en français le 25 juillet 1902 une longue lettre au Sultanxvi, incluant : « Par contre le gouvernement Impérial accorderait une charte ou concession de colonisation juive en Mésopotamie – comme Votre Majesté Impériale avait daigné m’offrir en février dernier- en ajoutant le territoire de Haïfa et ses environs en Palestine... »

En 1901 Théodore Herzl s’était vu refuser par le Sultan la concession coloniale juive en Palestine qu’il réclamait en proposant le rachat de l’écrasante dette ottomane et un crédit de 81 ans. Après avoir obtenu au printemps 1902 d’énormes crédits de 3 grandes banques européennes, Crédit Lyonnais, Dresdner Bank, Lloyds, Herzl retourna à Constantinople et là écrivit en français le 25 juillet 1902 une longue lettre au Sultanxvi, incluant : « Par contre le gouvernement Impérial accorderait une charte ou concession de colonisation juive en Mésopotamie – comme Votre Majesté Impériale avait daigné m’offrir en février dernier- en ajoutant le territoire de Haïfa et ses environs en Palestine... »

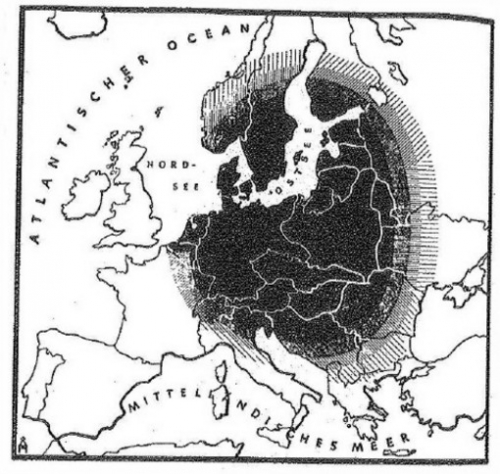

Sterker nog: er is eigenlijk véél meer overeenstemming in de geopolitieke wereld dan er in de economische wereld is. Zonder dat die overeenstemming met de macht van de straat afgedwongen wordt (cfr. de zogenaamde consensus in de wetenschappelijke wereld over klimaatopwarming, afgedwongen door activistische politieke instellingen en dito van mediatieke roeptoeters voorziene burgers). Er zijn een aantal verschillende verklaringsmodellen, geen daarvan is volledig, en er is sprake van voortschrijdend inzicht, maar de voorlopige conclusies gaan geen radicaal verschillende richtingen uit. Én het is ook gewoon een razend interessant kennisdomein, zeker in tijden waarin grotendeels gedaan wordt alsof grenzen voor eeuwig vastliggen, handels- en andere oorlogen zich bedienen van flauwe excuses, en gedateerde internationale instellingen hun leven proberen te rekken.

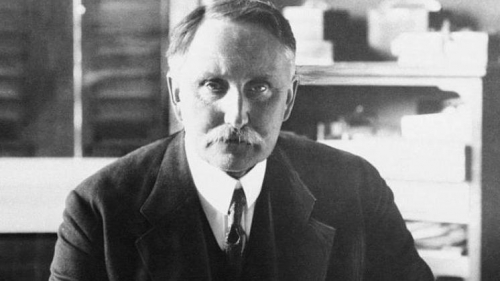

Sterker nog: er is eigenlijk véél meer overeenstemming in de geopolitieke wereld dan er in de economische wereld is. Zonder dat die overeenstemming met de macht van de straat afgedwongen wordt (cfr. de zogenaamde consensus in de wetenschappelijke wereld over klimaatopwarming, afgedwongen door activistische politieke instellingen en dito van mediatieke roeptoeters voorziene burgers). Er zijn een aantal verschillende verklaringsmodellen, geen daarvan is volledig, en er is sprake van voortschrijdend inzicht, maar de voorlopige conclusies gaan geen radicaal verschillende richtingen uit. Én het is ook gewoon een razend interessant kennisdomein, zeker in tijden waarin grotendeels gedaan wordt alsof grenzen voor eeuwig vastliggen, handels- en andere oorlogen zich bedienen van flauwe excuses, en gedateerde internationale instellingen hun leven proberen te rekken. En dan is er natuurlijk ook nog Karl als vader van Albrecht. De twee kwamen na de “vlucht” van Hess in een neerwaartse spiraal terecht (het nationaal-socialistische regime was zich wél bewust van het feit dat er een samenhang was tussen Hess en de Haushofers die véél verder ging dan het promoten van geopolitieke ideeën), maar zelfs binnen die spiraal bleven ze een merkwaardig evenwicht bewaren. Een evenwicht tussen afkeuring en goedkeuring van de Führer, tussen conservatisme en nationaal-socialisme, tussen oost en west, tussen esoterisme en wetenschap. Een evenwicht dat kennelijk heel moeilijk te begrijpen is in hysterische tijden als de onze en dat daarom steeds weer afgedaan wordt als onzin. Een evenwicht dat Karl Haushofer niet kon redden van een gevangenschap in Dachau en Albrecht Haushofer van executie in de nasleep van het conservatieve von Stauffenberg-complot. Een evenwicht dat Karl Haushofer en zijn echtgenote Martha definitief verloren toen ze zich op 10 maart 1946 achtereenvolgens vergiftigden en ophingen (al lijkt me dat, in combinatie met het lot van Hess, sowieso ook weer een eigenaardigheid).

En dan is er natuurlijk ook nog Karl als vader van Albrecht. De twee kwamen na de “vlucht” van Hess in een neerwaartse spiraal terecht (het nationaal-socialistische regime was zich wél bewust van het feit dat er een samenhang was tussen Hess en de Haushofers die véél verder ging dan het promoten van geopolitieke ideeën), maar zelfs binnen die spiraal bleven ze een merkwaardig evenwicht bewaren. Een evenwicht tussen afkeuring en goedkeuring van de Führer, tussen conservatisme en nationaal-socialisme, tussen oost en west, tussen esoterisme en wetenschap. Een evenwicht dat kennelijk heel moeilijk te begrijpen is in hysterische tijden als de onze en dat daarom steeds weer afgedaan wordt als onzin. Een evenwicht dat Karl Haushofer niet kon redden van een gevangenschap in Dachau en Albrecht Haushofer van executie in de nasleep van het conservatieve von Stauffenberg-complot. Een evenwicht dat Karl Haushofer en zijn echtgenote Martha definitief verloren toen ze zich op 10 maart 1946 achtereenvolgens vergiftigden en ophingen (al lijkt me dat, in combinatie met het lot van Hess, sowieso ook weer een eigenaardigheid). Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme: tijd, werk en invloed

Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme: tijd, werk en invloed

Sollte der Iran eine weitere Tanker-Flottille auf die Reise nach Südamerika schicken, könnten die Vereinigten Staaten ihre bisherige Zurückhaltung aufgeben und die Schiffe mit militärischer Gewalt an der Weiterfahrt hindern.

Sollte der Iran eine weitere Tanker-Flottille auf die Reise nach Südamerika schicken, könnten die Vereinigten Staaten ihre bisherige Zurückhaltung aufgeben und die Schiffe mit militärischer Gewalt an der Weiterfahrt hindern.

Pepe Escobar esquisse les grandes lignes des deux premières sessions du 13ème Congrès national du peuple, dont la troisième session devait se tenir le 5 mars 2020 mais a été postposée à cause de la crise du coronavirus. On peut d’ores et déjà imaginer que la Chine acceptera la légère récession dont elle sera la victime et fera connaître les mesures d’austérité qu’elle sera appelée à prendre. Pour Escobar, les conclusions de ce 13ème Congrès apporteront une réponse aux plans concoctés par les Etats-Unis et couchés sur le papier par le Lieutenant-Général H. R. McMaster (photo). Ce militaire du Pentagone décrit une Chine constituant trois menaces pour le « monde libre » avec : 1) Le programme « Made in China 2025 » visant le développement des nouvelles technologies, notamment autour de la firme Huawei et du développement de la 5G, indispensable pour créer les « smart cities » de l’avenir et où la Chine, en toute apparence, s’est dotée d’une bonne longueur d’avance ; 2) avec le programme des « routes de la soie », par lequel les Chinois se créent une clientèle d’Etats, dont le Pakistan, et réorganisent la masse continentale eurasienne ; 3) avec la fusion « militaire/civile », coagulation des idées de Clausewitz et de List, où, via la téléphonie mobile, la Chine s’avèrera capable de développer de larges réseaux d’espionnage et des capacités de cyber-attaques. Début mai 2020, Washington refuse de livrer des composantes à Huawei ; la Chine rétorque en plaçant Apple, Qualcomm et Cisco sur une « liste d’entreprises non fiables » et menace de ne plus acheter d’avions civils de fabrication américaine. Le tout, et Escobar n’en parle pas dans son article récent, dans un contexte où la Chine dispose de 95% des réserves de terres rares. Ces réserves lui ont permis, jusqu’ici, de marquer des points dans le développement des nouvelles technologies, dont la 5G et la téléphonie mobile, objets du principal ressentiment américain à l’égard de Pékin. Pour affronter l’avance chinoise en ce domaine, l’hegemon doit trouver d’autres sources d’approvisionnement en terres rares : d’où la proposition indirecte de Trump d’acheter le Groenland au royaume de Danemark, formulée l’automne dernier et reformulée en pleine crise du coronavirus. La Chine est présente dans l’Arctique, sous le couvert d’une série de sociétés d’exploitation minière dans une zone hautement stratégique : le passage dit « GIUK » (Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom) a été d’une extrême importance pendant la seconde guerre mondiale et pendant la guerre froide. L’ensemble de l’espace arctique le redevient, et de manière accrue, vu les ressources qu’il recèle, dont les terres rares que cherchent à s’approprier les Etats-Unis, et vu le passage arctique, libéré des glaces par les brise-glaces russes à propulsion nucléaire, qui deviendra une route plus courte et plus sécurisée entre l’Europe et l’Extrême-Orient, entre le complexe portuaire Anvers/Amsterdam/Hambourg et les ports chinois, japonais et coréens. L’hegemon a donc un double intérêt dans ses projets groenlandais qu’il est en train d’articuler : s’installer et profiter des atouts géologiques du Groenland, saboter l’exploitation de la route arctique. La crise du coronavirus cache cette problématique géopolitique et géoéconomique qui concerne l’Europe au tout premier plan !

Pepe Escobar esquisse les grandes lignes des deux premières sessions du 13ème Congrès national du peuple, dont la troisième session devait se tenir le 5 mars 2020 mais a été postposée à cause de la crise du coronavirus. On peut d’ores et déjà imaginer que la Chine acceptera la légère récession dont elle sera la victime et fera connaître les mesures d’austérité qu’elle sera appelée à prendre. Pour Escobar, les conclusions de ce 13ème Congrès apporteront une réponse aux plans concoctés par les Etats-Unis et couchés sur le papier par le Lieutenant-Général H. R. McMaster (photo). Ce militaire du Pentagone décrit une Chine constituant trois menaces pour le « monde libre » avec : 1) Le programme « Made in China 2025 » visant le développement des nouvelles technologies, notamment autour de la firme Huawei et du développement de la 5G, indispensable pour créer les « smart cities » de l’avenir et où la Chine, en toute apparence, s’est dotée d’une bonne longueur d’avance ; 2) avec le programme des « routes de la soie », par lequel les Chinois se créent une clientèle d’Etats, dont le Pakistan, et réorganisent la masse continentale eurasienne ; 3) avec la fusion « militaire/civile », coagulation des idées de Clausewitz et de List, où, via la téléphonie mobile, la Chine s’avèrera capable de développer de larges réseaux d’espionnage et des capacités de cyber-attaques. Début mai 2020, Washington refuse de livrer des composantes à Huawei ; la Chine rétorque en plaçant Apple, Qualcomm et Cisco sur une « liste d’entreprises non fiables » et menace de ne plus acheter d’avions civils de fabrication américaine. Le tout, et Escobar n’en parle pas dans son article récent, dans un contexte où la Chine dispose de 95% des réserves de terres rares. Ces réserves lui ont permis, jusqu’ici, de marquer des points dans le développement des nouvelles technologies, dont la 5G et la téléphonie mobile, objets du principal ressentiment américain à l’égard de Pékin. Pour affronter l’avance chinoise en ce domaine, l’hegemon doit trouver d’autres sources d’approvisionnement en terres rares : d’où la proposition indirecte de Trump d’acheter le Groenland au royaume de Danemark, formulée l’automne dernier et reformulée en pleine crise du coronavirus. La Chine est présente dans l’Arctique, sous le couvert d’une série de sociétés d’exploitation minière dans une zone hautement stratégique : le passage dit « GIUK » (Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom) a été d’une extrême importance pendant la seconde guerre mondiale et pendant la guerre froide. L’ensemble de l’espace arctique le redevient, et de manière accrue, vu les ressources qu’il recèle, dont les terres rares que cherchent à s’approprier les Etats-Unis, et vu le passage arctique, libéré des glaces par les brise-glaces russes à propulsion nucléaire, qui deviendra une route plus courte et plus sécurisée entre l’Europe et l’Extrême-Orient, entre le complexe portuaire Anvers/Amsterdam/Hambourg et les ports chinois, japonais et coréens. L’hegemon a donc un double intérêt dans ses projets groenlandais qu’il est en train d’articuler : s’installer et profiter des atouts géologiques du Groenland, saboter l’exploitation de la route arctique. La crise du coronavirus cache cette problématique géopolitique et géoéconomique qui concerne l’Europe au tout premier plan !

Toutefois, après avoir initialement dissimulé la gravité de l’épidémie, face aux soupçons, au lieu de jouer la carte de la transparence, le gouvernement chinois a déchaîné sa propagande contre ceux qui osaient critiquer sa version officielle et n’a pas hésité à faire la leçon à aux pays occidentaux sur leur propre gestion de l’épidémie. Cette attitude a braqué contre la Chine la majorité des Etats occidentaux et des voix se sont élevées pour réclamer une enquête de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé sur l’origine du virus, ce qu’a refusé Pékin, de même qu’il a refusé de participer aux financements lors des réunions de donateurs pour lutter mondialement contre l’épidémie.

Toutefois, après avoir initialement dissimulé la gravité de l’épidémie, face aux soupçons, au lieu de jouer la carte de la transparence, le gouvernement chinois a déchaîné sa propagande contre ceux qui osaient critiquer sa version officielle et n’a pas hésité à faire la leçon à aux pays occidentaux sur leur propre gestion de l’épidémie. Cette attitude a braqué contre la Chine la majorité des Etats occidentaux et des voix se sont élevées pour réclamer une enquête de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé sur l’origine du virus, ce qu’a refusé Pékin, de même qu’il a refusé de participer aux financements lors des réunions de donateurs pour lutter mondialement contre l’épidémie.