Louvain, 17 novembre 2018

Discours tenu lors du IIème Colloque du « Geopolitiek Instituut Vlaanderen-Nederland »

Introduction succincte à la géopolitique et à l’historiographie géopolitique des Bas-Pays

Mesdames, Mesdemoiselles, Messieurs,

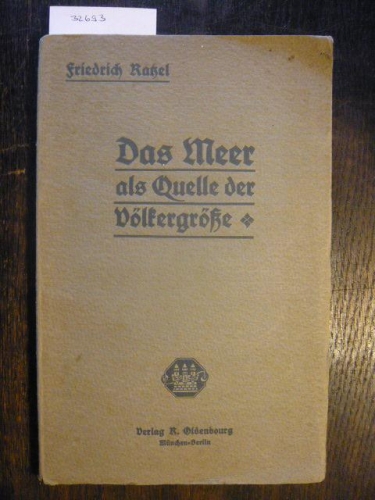

Les principaux manuels de géopolitiques, notamment celui que le Professeur David Criekemans a rédigé selon les critères de la plus haute scientificité dans le cadre de l’Université de Louvain, commencent presque toujours par une histoire de cette discipline depuis les premières tentatives de saisir conceptuellement les faits géographiques, non pas tant dans une perspective purement empirique mais surtout dans une perspective stratégique, notamment à l’aide de la cartographie établie par Carl Ritter, de l’anthropo-géographie de Ratzel ou des définitions données par le Suédois Rudolf Kjellén. C’est, personne ne le niera, un travail des plus utiles, ce qui était aussi mon intention lorsque feu le Professeur Jean-François Mattéi m’avait invité à présenter les penseurs de la géopolitique dans sa remarquable Encyclopédie des Œuvres philosophiques entre 1990 et 1992, encyclopédie qui fut ultérieurement publiée aux Presses Universitaires de France. L’intention du Prof. Mattéi correspondait à celle qu’avait déjà formulée le géopolitologue Yves Lacoste, à savoir élargir le cadre de la discipline, philosophique pour le premier, géographique/géopolitique pour le second. Mattéi voulait donc élargir le champ de la philosophie, tout simplement parce que plus aucune philosophie sérieuse ne peut encore être pensée sans tenir compte du temps et de l’espace, de l’émergence de tous les phénomènes, faits, modes de pensée et aspirations religieuses ou éthiques qui, tous, nécessairement, se déploient en des lieux et des périodes précises qu’ils influencent ensuite en profondeur, les inscrivant dans la durée et leur assurant une résilience difficilement éradicable.

Les principaux manuels de géopolitiques, notamment celui que le Professeur David Criekemans a rédigé selon les critères de la plus haute scientificité dans le cadre de l’Université de Louvain, commencent presque toujours par une histoire de cette discipline depuis les premières tentatives de saisir conceptuellement les faits géographiques, non pas tant dans une perspective purement empirique mais surtout dans une perspective stratégique, notamment à l’aide de la cartographie établie par Carl Ritter, de l’anthropo-géographie de Ratzel ou des définitions données par le Suédois Rudolf Kjellén. C’est, personne ne le niera, un travail des plus utiles, ce qui était aussi mon intention lorsque feu le Professeur Jean-François Mattéi m’avait invité à présenter les penseurs de la géopolitique dans sa remarquable Encyclopédie des Œuvres philosophiques entre 1990 et 1992, encyclopédie qui fut ultérieurement publiée aux Presses Universitaires de France. L’intention du Prof. Mattéi correspondait à celle qu’avait déjà formulée le géopolitologue Yves Lacoste, à savoir élargir le cadre de la discipline, philosophique pour le premier, géographique/géopolitique pour le second. Mattéi voulait donc élargir le champ de la philosophie, tout simplement parce que plus aucune philosophie sérieuse ne peut encore être pensée sans tenir compte du temps et de l’espace, de l’émergence de tous les phénomènes, faits, modes de pensée et aspirations religieuses ou éthiques qui, tous, nécessairement, se déploient en des lieux et des périodes précises qu’ils influencent ensuite en profondeur, les inscrivant dans la durée et leur assurant une résilience difficilement éradicable.

Yves Lacoste, fondateur et ancien éditeur de la célèbre revue Hérodote, voulait, lui aussi, élargir le champ scientifique de sa propre discipline, la géographie, dans le sens où même la description la plus purement factuelle d’un espace géographique ou d’une zone maritime sert le chef de guerre, si bien que, de ce fait, elle cesse d’être une science véritablement exacte : la géographie sert donc à faire la guerre, dit Lacoste, et toute guerre est menée au départ d’une perspective politique, historique ou religieuse, où des valeurs organiques, par définition non rationnelles, jouent un rôle toujours décisif, état de choses qui fait que tout géopolitologue doit prendre en considération ces valeurs, notamment à cause des dynamiques qu’elles suscitent, de l’impact qu’elles ont ensuite sur l’organisation d’un pays, de son agriculture et de ses armées, même si cet impact n’est pas exclusivement de nature géographique.

Lacoste a prouvé que la géographie sert les chefs de guerre en démontrant que les premières tentatives de dessiner des cartes dans la Chine de l’antiquité servaient à indiquer les voies à suivre aux chefs de guerre, de manière à ce qu’ils puissent mouvoir leurs armées de manière optimale dans les paysages et terrains divers de leur propre pays ou dans le pays de l’ennemi. Ensuite, dans un livre succinct, mais rédigé de manière magistrale, il nous a montré que le Prince Henri du Portugal, Anglais par sa mère, a fondé et soutenu son « école de la mer » afin de trouver de nouvelles voies maritimes extra-méditerranéennes pour que l’écoumène chrétien/européen de son époque puisse trouver le chemin vers les épices indiennes et vers le mystérieux « Cathay » en échappant aux blocus terrestres et maritimes que lui imposait le contrôle turc/ottoman des accès aux routes continentales vers l’Asie et des voies maritimes en Méditerranée. Quelques décennies plus tard, les Portugais livreront bataille dans la Corne de l’Afrique et des navires lusitaniens surgiront face aux côtes du Gujarat en Inde pour vaincre glorieusement une flotte musulmane. Tant les seigneurs de la guerre que les empereurs chinois du monde antique et que le Prince Henri du Portugal ont donc fait dessiner des cartes pour que des militaires ou des marins avisés puissent mener la guerre ou des expéditions exploratrices de manière optimale. Le raisonnement de Lacoste est parfaitement exact, et fut posé en dépit de son engagement idéologique dans les rangs de la gauche pacifiste.

Lacoste a prouvé que la géographie sert les chefs de guerre en démontrant que les premières tentatives de dessiner des cartes dans la Chine de l’antiquité servaient à indiquer les voies à suivre aux chefs de guerre, de manière à ce qu’ils puissent mouvoir leurs armées de manière optimale dans les paysages et terrains divers de leur propre pays ou dans le pays de l’ennemi. Ensuite, dans un livre succinct, mais rédigé de manière magistrale, il nous a montré que le Prince Henri du Portugal, Anglais par sa mère, a fondé et soutenu son « école de la mer » afin de trouver de nouvelles voies maritimes extra-méditerranéennes pour que l’écoumène chrétien/européen de son époque puisse trouver le chemin vers les épices indiennes et vers le mystérieux « Cathay » en échappant aux blocus terrestres et maritimes que lui imposait le contrôle turc/ottoman des accès aux routes continentales vers l’Asie et des voies maritimes en Méditerranée. Quelques décennies plus tard, les Portugais livreront bataille dans la Corne de l’Afrique et des navires lusitaniens surgiront face aux côtes du Gujarat en Inde pour vaincre glorieusement une flotte musulmane. Tant les seigneurs de la guerre que les empereurs chinois du monde antique et que le Prince Henri du Portugal ont donc fait dessiner des cartes pour que des militaires ou des marins avisés puissent mener la guerre ou des expéditions exploratrices de manière optimale. Le raisonnement de Lacoste est parfaitement exact, et fut posé en dépit de son engagement idéologique dans les rangs de la gauche pacifiste.

Halford John Mackinder prononce un célèbre discours en 1904 en Ecosse où il évoque le Heartland, la « Terre du Milieu » ou le « Cœur du Monde », capable de se soustraire à tous les efforts que la puissance navale britannique pourrait déployer pour y détruire la puissance continentale, russe, allemande ou chinoise, qui en serait devenue la maîtresse parce que le feu terrifiant des dreadnoughts de la flotte anglaise ne pourrait frapper ses points névralgiques. La puissance navale britannique se voyait dès lors contrainte de neutraliser et d’occuper, dans la mesure du possible, les rimlands, les bandes littorales plus ou moins profondes, du grand continent eurasiatique et de les « protéger » contre toute tentative du Heartland de les conquérir. On a appelé cette stratégie la stratégie de l’endiguement (containment), y compris après 1945, après que l’alliance entre les puissances anglo-saxonnes et l’Union Soviétique se soit dissoute et que les anciens partenaires soient devenus ennemis dans le cadre de la guerre froide. Les Etats-Unis vont alors organiser militairement les rimlands, en créant trois organisations défensives : l’OTAN, le CENTO (ou « Pacte de Bagdad », dissout partiellement en 1958 après le retrait de l’Irak baathiste) et l’OTASE pour l’Asie du Sud-Est. Après Mackinder, qui meurt en 1947, cette nouvelle stratégie de la guerre froide est théorisée par Nicholas Spykman, un stratégiste et géopolitologue américain d’origine néerlandaise, dont l’itinéraire et les idées ont été récemment étudiées par le Prof. Olivier Zajec, par ailleurs auteur d’une Introduction à l’analyse géopolitique (Ed. du Rocher, sept. 2018). On peut donc parler d’une lutte quasi permanente entre puissances continentales et puissances maritimes, permanence immuable sur l’échiquier global que ne cesse d’explorer et d’expliciter le discours géopolitique.

Mais s’il existe des permanences immuables en géopolitique, comment devons-nous repérer celles qui se manifestent dans le cadre géographique de nos bas pays ? La méthode, que je souhaite utiliser ici, et que j’ai toujours utilisée notamment dans l’écriture de ma trilogie, qui porte pour titre Europa, est celle d’un géopolitologue non politisé du temps de la République de Weimar. Son nom était Richard Henning (1874-1951), auteur d’un ouvrage très copieux, Geopolitik – Die Lehre vom Staat als Lebewesen, qui a connu cinq éditions successives. Henning avait une écriture très claire, limpide, n’utilisait jamais un jargon compliqué et illustrait chacun de ses arguments par des cartes précises. Au départ, sa discipline était la géographie des communications et des transports, renforcée par une géographie historique, où il mettait toujours l’accent sur le rôle des états, des hommes d’état et des surdoués politiques dans l’organisation et la transformation des espaces. Sa thèse centrale était de dire, à son époque, que les données spatiales d’un peuple devaient être davantage valorisées conceptuellement plutôt que les facteurs raciaux, ce qui le fit entrer en conflit avec les thèses officielles du pouvoir sous le Troisième Reich, même si, Prussien natif de Berlin, il défendait le principe clausewitzien d’une nécessaire militarisation défensive de tout état, en tenant compte, bien sûr, du vieil adage romain, Si vis pacem, para bellum. Dans les années 50 et 60 du 20ème siècle, son œuvre exerça une influence importante en Argentine sous le régime du Général Juan Peron et, plus tard, s’est retrouvée en filigrane dans les cours des écoles militaires du pays.

Mais s’il existe des permanences immuables en géopolitique, comment devons-nous repérer celles qui se manifestent dans le cadre géographique de nos bas pays ? La méthode, que je souhaite utiliser ici, et que j’ai toujours utilisée notamment dans l’écriture de ma trilogie, qui porte pour titre Europa, est celle d’un géopolitologue non politisé du temps de la République de Weimar. Son nom était Richard Henning (1874-1951), auteur d’un ouvrage très copieux, Geopolitik – Die Lehre vom Staat als Lebewesen, qui a connu cinq éditions successives. Henning avait une écriture très claire, limpide, n’utilisait jamais un jargon compliqué et illustrait chacun de ses arguments par des cartes précises. Au départ, sa discipline était la géographie des communications et des transports, renforcée par une géographie historique, où il mettait toujours l’accent sur le rôle des états, des hommes d’état et des surdoués politiques dans l’organisation et la transformation des espaces. Sa thèse centrale était de dire, à son époque, que les données spatiales d’un peuple devaient être davantage valorisées conceptuellement plutôt que les facteurs raciaux, ce qui le fit entrer en conflit avec les thèses officielles du pouvoir sous le Troisième Reich, même si, Prussien natif de Berlin, il défendait le principe clausewitzien d’une nécessaire militarisation défensive de tout état, en tenant compte, bien sûr, du vieil adage romain, Si vis pacem, para bellum. Dans les années 50 et 60 du 20ème siècle, son œuvre exerça une influence importante en Argentine sous le régime du Général Juan Peron et, plus tard, s’est retrouvée en filigrane dans les cours des écoles militaires du pays.

Par suite, si je privilégie l’exemple d’un historien-géographe comme Henning dans ma façon de raisonner en termes géopolitiques, je dois me limiter aux bas pays dans un exposé aussi bref que celui que je vais tenir aujourd’hui à Louvain, car il m’est impossible de parler de tous les pays qu’Henning a étudiés. Le temps qui m’est accordé est de fait limité et mon exposé se bornera à suggérer un certain nombre de pistes que nous devrons, ultérieurement, approfondir tous ensemble. Dans un ouvrage relativement récent de l’historien britannique Michael Pye, The Edge of the World – How the North Sea Made Us Who We Are (Viking/Penguin, London, 2014), nous trouvons, très largement esquissé, un cadre historique précis dans lequel Pye suggère l’émergence d’une histoire culturelle particulière qui se déploie, du moins au tout début de notre histoire, entre l’Islande et Calais et entre le Skagerrak danois/norvégien et les eaux de la Mer Baltique. Pour Pye, c’est en cette région que nait un monde à part, qui entretient certes des contacts, d’abord ténus, avec l’espace méditerranéen tout en restant plutôt autonome dans ses limites intérieures et où Bruges en constitue la plaque tournante méridionale à proximité du Pas-de-Calais. La Flandre médiévale abrite de ce fait le port principal de cette région de la Mer du Nord et de la Baltique qui doit nécessairement entretenir des contacts avec la Normandie, la Bretagne et surtout les côtes atlantiques du nord de l’Espagne, principalement le Pays Basque puis le Portugal, libéré par des croisés venus justement de toutes les régions du pourtours de la Mer du Nord, opération réussie dès le 12ème siècle qui démontre qu’il y avait une visée géopolitique implicite cherchant à étendre l’écoumène nordique à toutes les côtes de l’Atlantique européen. Cette Flandre prospère, pointe avancée vers le sud de cet espace nordique défini par Pye, cherche aussi à ouvrir une voie terrestre entre le Pays Basque et la Catalogne, sur le cours de l’Ebre, voie la plus courte vers les produits de la Méditerranée à une époque où la péninsule ibérique est encore sous contrôle musulman et ne peut être contournée sans danger.

Par suite, si je privilégie l’exemple d’un historien-géographe comme Henning dans ma façon de raisonner en termes géopolitiques, je dois me limiter aux bas pays dans un exposé aussi bref que celui que je vais tenir aujourd’hui à Louvain, car il m’est impossible de parler de tous les pays qu’Henning a étudiés. Le temps qui m’est accordé est de fait limité et mon exposé se bornera à suggérer un certain nombre de pistes que nous devrons, ultérieurement, approfondir tous ensemble. Dans un ouvrage relativement récent de l’historien britannique Michael Pye, The Edge of the World – How the North Sea Made Us Who We Are (Viking/Penguin, London, 2014), nous trouvons, très largement esquissé, un cadre historique précis dans lequel Pye suggère l’émergence d’une histoire culturelle particulière qui se déploie, du moins au tout début de notre histoire, entre l’Islande et Calais et entre le Skagerrak danois/norvégien et les eaux de la Mer Baltique. Pour Pye, c’est en cette région que nait un monde à part, qui entretient certes des contacts, d’abord ténus, avec l’espace méditerranéen tout en restant plutôt autonome dans ses limites intérieures et où Bruges en constitue la plaque tournante méridionale à proximité du Pas-de-Calais. La Flandre médiévale abrite de ce fait le port principal de cette région de la Mer du Nord et de la Baltique qui doit nécessairement entretenir des contacts avec la Normandie, la Bretagne et surtout les côtes atlantiques du nord de l’Espagne, principalement le Pays Basque puis le Portugal, libéré par des croisés venus justement de toutes les régions du pourtours de la Mer du Nord, opération réussie dès le 12ème siècle qui démontre qu’il y avait une visée géopolitique implicite cherchant à étendre l’écoumène nordique à toutes les côtes de l’Atlantique européen. Cette Flandre prospère, pointe avancée vers le sud de cet espace nordique défini par Pye, cherche aussi à ouvrir une voie terrestre entre le Pays Basque et la Catalogne, sur le cours de l’Ebre, voie la plus courte vers les produits de la Méditerranée à une époque où la péninsule ibérique est encore sous contrôle musulman et ne peut être contournée sans danger.

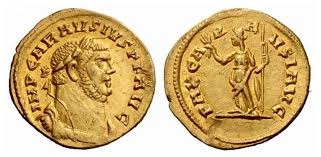

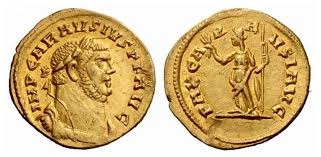

Le site particulier de la Mer du Nord détenait pourtant sa spécificité bien avant le dynamisme marchand et hanséatique de la Flandre médiévale : bien peu d’entre nos contemporains se souviennent encore d’une figure de l’époque romaine dans nos régions. Il s’agit d’un militaire romain du nom de Carausius. Il vécut au 3ème siècle, était ethniquement parlant un Ménapien, originaire de la Gallia Belgica. Après plusieurs décennies de turbulences dans les Gaules romaines, il est nommé par ses troupes « Imperator Britanniarum » ou « Empereur du Nord ». Il a régné à ce titre sur les provinces romaines de Britannia, de Gallia Belgica Prima et Secunda pendant treize ans. Commandant de la « Classis Britannica », c’est-à-dire de la flotte de la Manche, il avait reçu pour tâche de détruire la piraterie franque et saxonne qui en écumait les eaux, troublant le commerce de l’étain en provenance des Cornouailles. Les Romains l’ont accusé de coopérer avec ces pirates pour acquérir personnellement du butin. En réaction contre ces accusations, il se crée un propre empire dans la Manche et la Mer du Nord (Mare Germanicum) avec l’appui de quatre légions, de troupes auxiliaires indigènes, de sa propre flotte et de celle des pirates qu’il avait dû préalablement combattre, avant de s’en faire des alliés. Il est assassiné en 293. Carausius, toutefois, est le premier chef de guerre, sur terre et sur mer, qui a considéré l’ensemble de nos régions comme une unité géostratégique, non plus seulement autour des trois grands fleuves, le Rhin, la Meuse et l’Escaut mais autour des espaces maritimes de la Manche et de la Mer du Nord.

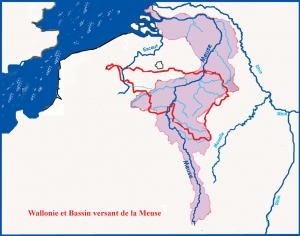

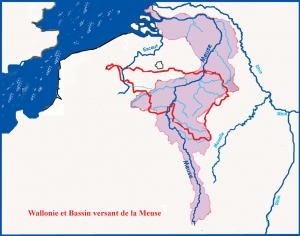

L’approche romaine du territoire était plutôt axée sur les rivières : en effet, César a d’abord dû contrôler le bassin du Rhône pour le protéger contre les Helvètes celtiques ou contre les Germains d’Arioviste qui, au départ de la Forêt Noire, traversaient le Rhin à hauteur de Bâle, remontaient le Doubs, soit le principal affluent de la Saône qui, elle, était le principal affluent du Rhône. Or si l’on veut contrôler le cours tout entier de la Saône, on doit tenir aussi le Plateau de Langres, principal château d’eau des Gaules, où la Seine et la Marne, et aussi la Meuse, prennent leur source. Toute puissance qui entend utiliser l’atout hydropolitique du Plateau de Langres doit également avoir pour but le contrôle des bassins de la Seine, de la Meuse et de la Moselle et toute puissance qui veut empêcher que le Doubs devienne la première porte d’entrée des Germains en marche vers Provence, contrôlée par Rome, doit nécessairement contrôler le Rhin jusqu’à son embouchure dans la Mer du Nord.

Le destin géopolitique des bas pays dépend donc des rivières et fleuves, surtout de la Meuse et de l’Escaut et aussi, en ce qui concerne le Luxembourg, de la Moselle. Mais ils dépendent aussi de l’écoumène qui a surgi, au cours de l’histoire, autour de la Mer du Nord depuis l’époque de ce fameux Carausius, dont l’un des héritiers sera le Danois Knut ou Canute au début du 11ème siècle, qui règnera sur l’Angleterre, la Norvège et le Danemark.

L’écoumène de la Mer du Nord a été lié, pendant toute l’époque médiévale, à la Mer Baltique, avec le Danemark comme plaque tournante, un Danemark qui exigeait parfois d’énormes droits de passage pour les navires flamands ou anglais qui entendaient se rendre dans les eaux de la Baltique. La Hanse, bien qu’elle constitue un idéal pour ceux qui rêvent d’un monde nordique autonome, à l’abri des turbulences de la Méditerranée, n’a pourtant pas été une structure idéale à cause des concurrences diverses qui surgissaient entre les villes qui la composaient et à cause d’alliances parfois problématiques entre certaines villes et certains pirates contre d’autres villes et d’autres pirates. Plus tard, la Prusse, puissance montante dans l’hinterland des deux mers, aura pour objectif géopolitique d’en contrôler les côtes et d’en éliminer toutes les formes de concurrence stérile, en s’opposant parfois à la Suède.

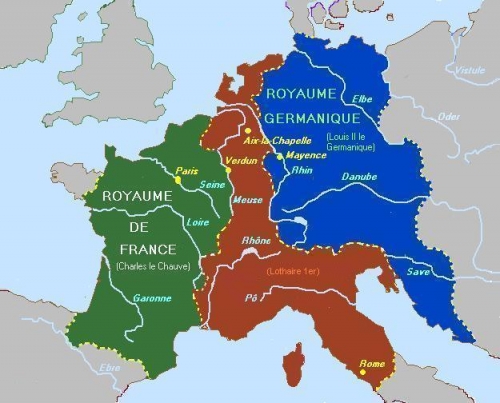

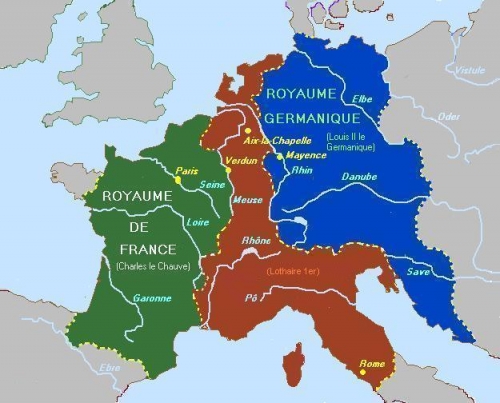

Revenons au continent. Lorsque les petits-fils de Charlemagne se partagent l’Empire de leur aïeul lors du Traité de Verdun en 843, cette division de l’héritage est souvent apparue comme absurde. Or elle était rationnelle dans la mesure où les trois héritiers se partageaient des bassins fluviaux. Leur géopolitique implicite était de fait une hydropolitique. A Verdun en 843 s’amorce une dynamique qui conduira aux trois guerres franco-allemandes depuis 1870. Le plus jeune des petits-fils, Louis, dit Louis le Germanique, s’empare in fine de la partie centrale qui avait été dévolue à feu son frère aîné, Lothaire, ce qui heurte les intérêts de Charles, devenu roi de la Francie occidentale, la future France, qui fera tout pour reprendre les deux parties de la grande « Lotharingie » de Lothaire, en vain dans la première phase de cette lutte pluriséculaire. L’héritage de ce Lothaire, mort prématurément, consistait en une Basse Lotharingie et une Haute Lotharingie, une Burgondie ou un Arélat, ce qui correspond à nos Pays-Bas pour la Basse Lotharingie et à la Lorraine, l’Alsace, la Franche-Comté et la Suisse romande pour la Haute Lotharingie ; quant à la Burgondie ou Arélat, elle est formée par le bassin du Rhône jusqu’à la Méditerranée provençale (comprenant la Bresse, la Savoie, le Dauphiné et la Provence). Lothaire possédait aussi l’Italie du Nord, plus exactement le bassin du Pô. De Philippe le Bel à Napoléon III, qui annexera la Savoie, Paris s’emparera systématiquement de territoires qui firent partie de l’héritage de Lothaire, si bien que nous pouvons aujourd’hui décrire la Belgique, les Pays-Bas et le Luxembourg comme de minuscules résidus d’un empire potentiellement puissant qui n’a jamais pu se développer sauf pendant le règne bref de l’Empereur germanique Konrad II, au 11ème siècle.

Les ducs de Bourgogne essaieront, par une politique habile, de ressusciter l’Empire de Lothaire mais sans succès. Pour comprendre la dynamique de l’histoire européenne dans nos régions, nous devons donc, aujourd’hui, étudier la géopolitique implicite de ces ducs qui entendaient consolider une alliance avec l’Angleterre et englober la Lorraine et l’Alsace dans leur orbite politique afin de joindre leurs possessions de l’ancienne Basse Lotharingie (« Pays de Par-Deça ») avec celles de l’ancienne Haute Lotharingie et de la Bourgogne (fief français inclus dans la Francie occidentale de Charles le Chauve). Cependant, dans cette étude, nous ne devons surtout pas oublier que la tête pensante de cette géopolitique bourguignonne a été Isabelle de Portugal (ou Isabelle de Bourgogne), épouse de Philippe le Bon et mère de Charles le Hardi (dit le « Téméraire » en France). Isabelle de Portugal était la sœur du Prince Henri, dit « Henri le Navigateur », fils du roi du Portugal et de Philippine de Lancaster, princesse anglaise. Le Prince Henri (1394-1460) a fondé son école maritime, école géopolitique avant la lettre, à Sagres au Portugal, dans le but de créer les conditions requises pour le développement de flottes de haute mer et de mobiliser tous les savoirs pratiques disponibles pour pouvoir, à terme, contourner les empires musulmans et trouver de nouvelles voies vers l’Inde et la Chine. Yves Lacoste, fondateur de la revue Hérodote et pionnier de la redécouverte des théories géopolitiques en France à partir des années 1970, a consacré une bonne part de son livre sur l’histoire de la cartographie à la figure d’Henri le Navigateur et a ainsi démontré que ce prince fut l’impulseur premier de la conquête européenne du monde.

Les ducs de Bourgogne essaieront, par une politique habile, de ressusciter l’Empire de Lothaire mais sans succès. Pour comprendre la dynamique de l’histoire européenne dans nos régions, nous devons donc, aujourd’hui, étudier la géopolitique implicite de ces ducs qui entendaient consolider une alliance avec l’Angleterre et englober la Lorraine et l’Alsace dans leur orbite politique afin de joindre leurs possessions de l’ancienne Basse Lotharingie (« Pays de Par-Deça ») avec celles de l’ancienne Haute Lotharingie et de la Bourgogne (fief français inclus dans la Francie occidentale de Charles le Chauve). Cependant, dans cette étude, nous ne devons surtout pas oublier que la tête pensante de cette géopolitique bourguignonne a été Isabelle de Portugal (ou Isabelle de Bourgogne), épouse de Philippe le Bon et mère de Charles le Hardi (dit le « Téméraire » en France). Isabelle de Portugal était la sœur du Prince Henri, dit « Henri le Navigateur », fils du roi du Portugal et de Philippine de Lancaster, princesse anglaise. Le Prince Henri (1394-1460) a fondé son école maritime, école géopolitique avant la lettre, à Sagres au Portugal, dans le but de créer les conditions requises pour le développement de flottes de haute mer et de mobiliser tous les savoirs pratiques disponibles pour pouvoir, à terme, contourner les empires musulmans et trouver de nouvelles voies vers l’Inde et la Chine. Yves Lacoste, fondateur de la revue Hérodote et pionnier de la redécouverte des théories géopolitiques en France à partir des années 1970, a consacré une bonne part de son livre sur l’histoire de la cartographie à la figure d’Henri le Navigateur et a ainsi démontré que ce prince fut l’impulseur premier de la conquête européenne du monde.

Isabelle de Portugal voulait poursuivre sa politique maritime et continentale à une époque où la France était sortie victorieuse de la guerre de cent ans et où l’Angleterre avait sombré dans une guerre civile entre les Maisons de York et de Lancastre. Philippe le Bon voulait, lui, retourner à une politique française parce que l’Angleterre semblait hors-jeu tandis que son épouse et son fils voulaient maintenir une ligne pro-anglaise contre Charles VII de France et son fils, le futur Louis XI. Finalement, la géopolitique bourguignonne débouchera sur une double alliance continentale, avec l’entrée en scène des Habsbourgs pour sauver les Pays-Bas de l’invasion française, ensuite avec la Castille et l’Aragon pour créer un bastion anti-français dans le sud de l’Europe, créant ainsi dans le delta des fleuves et dans la péninsule ibérique la fusion géostratégique rêvée par les marchands hanséatiques flamands du 12ème siècle. L’Empereur Charles-Quint règnera sur l’ensemble de ces terres rassemblées par son aïeul Charles, son bisaïeul Philippe et son arrière-grand-mère Isabelle et nous savons tous, Flamands comme Néerlandais, quel sort tragique les bas pays et l’Allemagne ont connu dans cette orbe impériale qui, hélas, ne fut jamais harmonisée.

Sous Philippe III d’Espagne, fils de Philippe II que nous n’aimions guère, se déchaîne une véritable guerre mondiale entre les puissances réformées et les puissances catholiques, qui n’eut pas que l’Europe comme théâtre d’opération mais où les affrontements eurent également lieu en Afrique, en Amérique et, ce que l’on oublie généralement, dans les eaux de l’Océan Pacifique, considéré à l’époque comme un « océan espagnol ». Sous le règne de Philippe III, tous les conflits d’ordre géopolitique, tous les conflits nés de la volonté des uns et des autres de maîtriser des sites stratégiques indispensables le long des voies maritimes ont émergé et sont parfois encore virulents aujourd’hui: plusieurs puissances non européennes de nos jours les activent encore régulièrement, notamment dans la Mer de Chine du Sud et entre les Philippines et les côtes de la Chine continentale. Une étude de cette période, dont nous ne nous souvenons plus sauf peut-être l’épisode du siège d’Ostende, s’avère nécessaire pour comprendre la situation géopolitique des bas pays car leurs provinces méridionales faisaient partie, volens nolens, de cet empire espagnol et devinrent, au cours des innombrables affrontements durant le règne de Philippe III et de ses successeurs, ce que les historiens anglais nomment aujourd’hui la fatal avenue, le « corridor fatal », où passaient et s’affrontaient les armées.

Sous Philippe III d’Espagne, fils de Philippe II que nous n’aimions guère, se déchaîne une véritable guerre mondiale entre les puissances réformées et les puissances catholiques, qui n’eut pas que l’Europe comme théâtre d’opération mais où les affrontements eurent également lieu en Afrique, en Amérique et, ce que l’on oublie généralement, dans les eaux de l’Océan Pacifique, considéré à l’époque comme un « océan espagnol ». Sous le règne de Philippe III, tous les conflits d’ordre géopolitique, tous les conflits nés de la volonté des uns et des autres de maîtriser des sites stratégiques indispensables le long des voies maritimes ont émergé et sont parfois encore virulents aujourd’hui: plusieurs puissances non européennes de nos jours les activent encore régulièrement, notamment dans la Mer de Chine du Sud et entre les Philippines et les côtes de la Chine continentale. Une étude de cette période, dont nous ne nous souvenons plus sauf peut-être l’épisode du siège d’Ostende, s’avère nécessaire pour comprendre la situation géopolitique des bas pays car leurs provinces méridionales faisaient partie, volens nolens, de cet empire espagnol et devinrent, au cours des innombrables affrontements durant le règne de Philippe III et de ses successeurs, ce que les historiens anglais nomment aujourd’hui la fatal avenue, le « corridor fatal », où passaient et s’affrontaient les armées.

La bataille de Rocroi (1643) fut la dernière bataille des fameux tercios espagnols, où ils ont appliqué leurs techniques de combat, auparavant imparables. Ils furent battus mais leur sacrifice ne fut pas inutile. Ils y ont rudement éprouvé l’ennemi, si bien qu’il a été impossible aux Français de marcher sur Bruxelles après le choc. Il n’existe qu’une seule brochure sur la « géopolitique du Nord-Ouest » (de l’Europe), qui expliquent les motivations géographiques des belligérants sur ce territoire, notamment au temps de cette bataille de Rocroi. Elle a été écrite par un homme qui est demeuré totalement inconnu, un certain J. Mercier, qui l’a rédigée pendant la seconde guerre mondiale sans s’orienter sur une politique pro-belge ou pro-allemande. Pour lui, les Pays-Bas du Sud sont composés de trois parties du point de vue géopolitique : la Flandre occidentale, à l’ouest de l’Escaut et de la Lys ; le centre qu’il appelle « l’espace scaldien » parce qu’il se situe entre le cours de l’Escaut et celui de la Meuse ; et, enfin, le glacis ardennais à l’est de la Meuse. La dynamique qui articulait ce triple ensemble était la suivante :

- La Flandre occidentale était une région qui servait aux Français à encercler, le cas échéant, le centre (« l’espace scaldien ») ; c’est la raison pour laquelle la France de Louis XIV a, un moment, annexé Furnes, Ypres et Ostende ;

- Le centre était considéré, normalement, comme l’objectif le plus important de toute conquête éventuelle de l’ensemble des Pays-Bas Royaux ou espagnols, parce que Bruxelles et Anvers s’y trouvaient ;

- Le glacis ardennais était un espace de réserve qui, après Rocroi, a accueilli les troupes vaincues du Colonel Fontaine (« de la Fuente » dans certaines sources espagnoles) pour les joindre à celles d’un autre colonel espagnol, von Beck, commandant des tercios allemands et luxembourgeois, prêt à lancer une nouvelle offensive contre les vainqueurs.

La Meuse est un axe de pénétration géostratégique dans la direction d’Aix-la-Chapelle, capitale symbolique du Saint-Empire : ce qui explique les tentatives répétées de Richelieu pour acheter la neutralité de la Principauté épiscopale de Liège et l’entêtement des Néerlandais du Nord, et plus tard des Prussiens, de conserver la place forte de Maastricht, de la soustraire aux Français ou à une Belgique qui serait inféodée à la France. La brochure de J. Mercier est un survol assez bref de la situation géopolitique des Pays-Bas et, plus particulièrement, de la fatal avenue, que leur portion méridionale allait devenir au cours de l’histoire. Le contenu de cette brochure mériterait d’être étoffé de bon nombre de faits historiques sur la période bourguignonne, sur le régime espagnol du Duc d’Albe à 1713, sur la période autrichienne au 18ème siècle et sur les stratégies défensives au temps des conquêtes de la France révolutionnaire, jusqu’à l’ultime bataille de Waterloo en juin 1815.

La Meuse est un axe de pénétration géostratégique dans la direction d’Aix-la-Chapelle, capitale symbolique du Saint-Empire : ce qui explique les tentatives répétées de Richelieu pour acheter la neutralité de la Principauté épiscopale de Liège et l’entêtement des Néerlandais du Nord, et plus tard des Prussiens, de conserver la place forte de Maastricht, de la soustraire aux Français ou à une Belgique qui serait inféodée à la France. La brochure de J. Mercier est un survol assez bref de la situation géopolitique des Pays-Bas et, plus particulièrement, de la fatal avenue, que leur portion méridionale allait devenir au cours de l’histoire. Le contenu de cette brochure mériterait d’être étoffé de bon nombre de faits historiques sur la période bourguignonne, sur le régime espagnol du Duc d’Albe à 1713, sur la période autrichienne au 18ème siècle et sur les stratégies défensives au temps des conquêtes de la France révolutionnaire, jusqu’à l’ultime bataille de Waterloo en juin 1815.

Dans la production littéraire et historiographique du mouvement flamand existe un gros volume, aujourd’hui oublié, dû à la plume de Maurits Josson et datant de 1913 ; cet ouvrage copieux et dense récapitule toutes les batailles qui ont été livrées pour contenir, avec des fortunes diverses, les invasions venues du Sud. Le livre a été publié juste avant la mort de Josson et le déclenchement de la première guerre mondiale. Josson était une figure intéressante de son époque, de la Belgique d’avant 1914 : il devint célèbre comme reporter pendant la guerre des Boers en Afrique du Sud, devenant dans la foulée un critique virulent de l’impérialisme britannique dans le cône austral du continent noir. Son étude en trois volumes de la révolte belge de septembre 1830 (« de Belgische Omwenteling ») et de ses prolégomènes mérite toute notre attention si nous voulons approfondir la géopolitique des Pays-Bas du Sud. Son livre sur « la France comme ennemis pluriséculaire de la Belgique » a été écrit, notamment, quand sévissaient de houleux débats dans le parlement belge sur la question des chemins de fer entre Bruxelles et Liège et entre Liège et l’Allemagne. Les Français avaient exercé une pression économique et menacé la Belgique de guerre si les chemins de fer et l’industrie belge de l’acier étaient reliés aux lignes ferroviaires allemandes, donc à la région de la Ruhr, et si la ligne Cologne-Liège était prolongée jusqu’à Bruxelles et Anvers. Nous retombons ici dans une problématique toute actuelle : la construction de chemins de fer et l’établissement de communications terrestres, ajoutant de la qualité à un espace, quel qu’il soit, suscitent encore et toujours la méfiance, notamment, aujourd’hui, à Washington parce que les politiques de développement en ces domaines viennent désormais de Chine. Ici, une fois de plus, Richard Henning, a raison dans sa méthode : l’organisation de toutes formes de réseaux de communication détermine la géopolitique d’un pays et aussi les réactions de ses ennemis, même s’ils appartiennent à la même « race ».

Immédiatement avant la première guerre mondiale, en 1912, meurt une autre figure importante de la pensée géopolitique concernant nos régions : Homer Lea, auteur de The Day of the Saxon. Lea avait été un élève handicapé de West Point qui avait su maîtriser avec brio toutes les disciplines théoriques de sa célèbre école militaire mais ne pouvait évidemment pas servir sur le terrain, au sein d’un régiment, vu son pied bot. Il fut actif en Chine pour soutenir le mouvement modernisateur de Sun Ya Tsen dans l’espoir de faire éclore une alliance durable entre l’Empire du Milieu, devenu république moderne, et les Etats-Unis. Son livre me parait, à moi comme au stratégiste suisse Jean-Jacques Langendorf, aussi important que le texte de Mackinder où le géographe écossais esquisse la dualité terre/mer et jette les fondements de la géostratégie globale des puissances anglo-saxonnes. Dans The Day of the Saxon, Lea explique comment la Grande-Bretagne et les Etats-Unis doivent, en toutes circonstances, empêcher la Russie de dépasser la ligne Téhéran/Kaboul. L’état actuel de conflictualité diffuse entre la telluricité russe et le thalassocratisme anglo-saxon depuis 1979, qui a commencé dès l’intervention soviétique en Afghanistan, est donc une application du précepte préconisé par Lea dans son livre, puisque l’Armée rouge de Brejnev avait franchi cette ligne fatidique. Pour ce qui concerne les Pays-Bas, les Low Countries, Lea a esquissé, bien avant les coups de feu de Sarajevo, les raisons d’une future guerre anglo-allemande, que Londres, à ses yeux, devait impérativement mener : les côtes de la Hollande, de la Belgique et du Danemark ne peuvent en aucun cas tomber entre les mains des Allemands et les « Saxons » doivent s’apprêter à défendre la France contre l’Allemagne pour que les ports de Dunkerque et de Calais ne soient pas occupés par la Kriegsmarine et pour que les armées du Kaiser ne prennent pas pied en Normandie sur les côtes de la Manche. Il était évident, dès lors, que l’Angleterre allait combattre l’Allemagne si celle-ci violait la neutralité belge ou néerlandaise. Pour la Belgique, une telle violation, en fait, n’avait guère d’importance puisque, de facto, elle faisait partie de la Zollunion allemande, de même que les Pays-Bas. A la limite, elle pouvait récupérer les départements du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais, perdus depuis le 17ème siècle. En revanche, pour le Congo, c’était une autre histoire : le Roi Albert I ne pouvait accepter le transit des troupes allemandes vers la France car, dans ce cas, les Anglais auraient immédiatement occupé le Congo et plus particulièrement le Katanga, tout simplement parce que cette province, riche en mines de cuivre, formait surtout un obstacle territorial au grand projet de Cecil Rhodes, celui de relier le Cap au Caire par une même ligne de communications terrestres. Il y avait aussi un précédent que méditaient les chancelleries : les colonies hollandaises du Cap, de l’Ile Maurice et de Ceylan avaient été envahies et annexées au moment où Napoléon Bonaparte avait transformé les Pays-Bas du Nord en une série de départements français, prétextant que le territoire de la Hollande était français puisqu’il provenait d’alluvions de fleuves français.

Immédiatement avant la première guerre mondiale, en 1912, meurt une autre figure importante de la pensée géopolitique concernant nos régions : Homer Lea, auteur de The Day of the Saxon. Lea avait été un élève handicapé de West Point qui avait su maîtriser avec brio toutes les disciplines théoriques de sa célèbre école militaire mais ne pouvait évidemment pas servir sur le terrain, au sein d’un régiment, vu son pied bot. Il fut actif en Chine pour soutenir le mouvement modernisateur de Sun Ya Tsen dans l’espoir de faire éclore une alliance durable entre l’Empire du Milieu, devenu république moderne, et les Etats-Unis. Son livre me parait, à moi comme au stratégiste suisse Jean-Jacques Langendorf, aussi important que le texte de Mackinder où le géographe écossais esquisse la dualité terre/mer et jette les fondements de la géostratégie globale des puissances anglo-saxonnes. Dans The Day of the Saxon, Lea explique comment la Grande-Bretagne et les Etats-Unis doivent, en toutes circonstances, empêcher la Russie de dépasser la ligne Téhéran/Kaboul. L’état actuel de conflictualité diffuse entre la telluricité russe et le thalassocratisme anglo-saxon depuis 1979, qui a commencé dès l’intervention soviétique en Afghanistan, est donc une application du précepte préconisé par Lea dans son livre, puisque l’Armée rouge de Brejnev avait franchi cette ligne fatidique. Pour ce qui concerne les Pays-Bas, les Low Countries, Lea a esquissé, bien avant les coups de feu de Sarajevo, les raisons d’une future guerre anglo-allemande, que Londres, à ses yeux, devait impérativement mener : les côtes de la Hollande, de la Belgique et du Danemark ne peuvent en aucun cas tomber entre les mains des Allemands et les « Saxons » doivent s’apprêter à défendre la France contre l’Allemagne pour que les ports de Dunkerque et de Calais ne soient pas occupés par la Kriegsmarine et pour que les armées du Kaiser ne prennent pas pied en Normandie sur les côtes de la Manche. Il était évident, dès lors, que l’Angleterre allait combattre l’Allemagne si celle-ci violait la neutralité belge ou néerlandaise. Pour la Belgique, une telle violation, en fait, n’avait guère d’importance puisque, de facto, elle faisait partie de la Zollunion allemande, de même que les Pays-Bas. A la limite, elle pouvait récupérer les départements du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais, perdus depuis le 17ème siècle. En revanche, pour le Congo, c’était une autre histoire : le Roi Albert I ne pouvait accepter le transit des troupes allemandes vers la France car, dans ce cas, les Anglais auraient immédiatement occupé le Congo et plus particulièrement le Katanga, tout simplement parce que cette province, riche en mines de cuivre, formait surtout un obstacle territorial au grand projet de Cecil Rhodes, celui de relier le Cap au Caire par une même ligne de communications terrestres. Il y avait aussi un précédent que méditaient les chancelleries : les colonies hollandaises du Cap, de l’Ile Maurice et de Ceylan avaient été envahies et annexées au moment où Napoléon Bonaparte avait transformé les Pays-Bas du Nord en une série de départements français, prétextant que le territoire de la Hollande était français puisqu’il provenait d’alluvions de fleuves français.

Pour résumer la problématique :

Les Français veulent contrôler le Rhin et utiliser le cours de la Meuse pour réaliser un des objectifs éternels de leur politique : être présents en Mer du Nord, au nord du Pas-de-Calais, ce qu’ils n’ont jamais réussi à faire, puisque le Comté de Flandre, initialement fief français qui leur donnait accès à cette mer tant convoitée, s’est toujours montré rebelle et rétif.

Les Allemands veulent contrôler les côtes de la Mer du Nord et, éventuellement, celles de la Manche ; pendant la première guerre mondiale, ils développent considérablement les infrastructures des ports flamands d’Ostende et de Zeebrugge ; leur objectif est donc de déboucher également dans la Manche pour avoir meilleur accès à l’Amérique. C’était déjà le but de Maximilien de Habsbourg, époux de Marie de Bourgogne, fille de Charles le Hardi dit le Téméraire, à la fin du 15ème siècle, avant même la découverte du Nouveau Monde par Colomb ; Maximilien avait voulu contrôler la Bretagne, excellent tremplin vers l’Amérique, en en épousant la duchesse et en liant cette péninsule armoricaine aux Pays-Bas.

Les Allemands veulent contrôler les côtes de la Mer du Nord et, éventuellement, celles de la Manche ; pendant la première guerre mondiale, ils développent considérablement les infrastructures des ports flamands d’Ostende et de Zeebrugge ; leur objectif est donc de déboucher également dans la Manche pour avoir meilleur accès à l’Amérique. C’était déjà le but de Maximilien de Habsbourg, époux de Marie de Bourgogne, fille de Charles le Hardi dit le Téméraire, à la fin du 15ème siècle, avant même la découverte du Nouveau Monde par Colomb ; Maximilien avait voulu contrôler la Bretagne, excellent tremplin vers l’Amérique, en en épousant la duchesse et en liant cette péninsule armoricaine aux Pays-Bas.

Les Anglais ne voulaient à aucun prix qu’Anvers, Flessingue et le « Hoek van Holland » ne tombent aux mains des Français ou des Allemands car la possession de ces ports par une puissance dotée d’un vaste hinterland continental est, pour eux, un cauchemar, celui de voir, comme au 17ème siècle, un nouvel amiral de Ruyter partir d’un port néerlandais pour atteindre Londres en une seule nuit (au temps de la marine à voiles). Les Pays-Bas, du Nord comme du Sud, doivent donc demeurer divisés et « neutralisés », c’est-à-dire ne rejoindre aucune alliance trop étroite avec la France ou avec l’Allemagne, selon l’adage latin Divide ut impera, que l’Angleterre conquérante n’a jamais cessé de vouloir concrétiser, partout sur le globe.

J’ai esquissé, trop brièvement, j’en ai bien conscience, le cadre initial, au départ duquel nous devons articuler nos réflexions d’ordre géopolitique, en récapitulant les voies globales qui furent jadis ouvertes à partir de notre espace, défini par Pye : vers l’Atlantique Nord en suivant les bancs de morues, vers l’Arctique à partir de la découverte, par les Scandinaves, des Iles Svalbard, porte d’entrée de l’Arctique, vers tous les comptoirs de la Hanse et, par la Manche, vers les ports de la partie septentrionale de la péninsule ibérique et du Portugal et, de là, à partir de la découverte de l’Amérique par Colomb, vers l’Amérique du Sud et l’Antarctique, sans oublier le désir des Croisés, des Ducs de Bourgogne et des Rois d’Espagne de rouvrir les routes de la soie, maritimes et terrestres vers la Chine, en ancrant une présence hispano-habsbourgeoise dans le Pacifique, ce que n’ont jamais omis non plus les futurs Etats contemporains de nos Pays-Bas divisés, en Insulinde par le biais de la colonisation nord-néerlandaise, en Chine et au Japon par la voie d’une diplomatie belge, du moins quand elle n’était pas encore totalement inféodée à l’atlantisme, incluse dans le « Spaakistan » comme le rappelle le Prof. Rik Coolsaet de l’Université de Gand.

Donc les questions qui se posent à nous aujourd’hui sont les suivantes :

- Devons-nous participer ou non à une nouvelle dynamique qui se dessine en Europe centrale et en Europe orientale et cela, sans aucune limite ?

- Devons-nous participer à l’élaboration de nouvelles voies de communication, selon le projet chinois de la « Route de la Soie », tout en tenant compte du fait bien évident que les ports de Rotterdam et d’Anvers sont les ports les plus importants qui réceptionnent de nos jours les marchandises importées de Chine et, simultanément, les ports les plus importants d’où partent les marchandises européennes exportées vers la Chine, situation qui se confirmera, a fortiori quand la route arctique sera bientôt ouverte ?

- Devons-nous encore et toujours dépendre mentalement de l’idéologie occidentale, qui nous empêche, de commercer normalement avec la Russie, qui fut, pour la Belgique, le principal partenaire commercial avant 1914, qui a fait de la Belgique un pays très riche avant le cataclysme de la première guerre mondiale ?

- Devons-nous opter avec l’Amérique, une Amérique avec ou sans Trump, pour l’isolement atlantique au détriment de toute coopération eurasiatique ?

- Devons-nous développer une géopolitique originale, pour le bénéfice de nos bas pays, où l’historien et le géopolitologue doivent coopérer pour additionner tous les faits qui, au fil des siècles, se sont avérés positifs pour nos régions et pour vulgariser ces perspectives innovantes de façon à ce qu’elles se diffusent dans la population et chez les décideurs ?

- Devons-nous nous souvenir ou devons-nous oublier que nous fîmes partie de l’Empire de Charles-Quint et, du moins pour les Pays-Bas du Sud, de l’empire espagnol en Amérique et dans le Pacifique, sous les règnes de Philippe III, Philippe IV et Charles II, et que nous fûmes actifs sur toutes ces parties du globe, en n’oubliant pas non plus que le Père Ferdinand Verbist fut le principal ministre de la Chine du 17ème siècle ?

- Devons-nous oublier et abandonner ce tropisme chinois qui fut toujours, tacitement, un désir fécond de la politique et de la diplomatie belges ?

- Devons-nous aussi oublier que nous avons tous vécu de formidables aventures en Indonésie, dans le Pacifique et dans les Amériques, que ce soit sous la bannière catholique ou réformée et que nous avons été des acteurs féconds dans tous les coins du monde (cf. : « Vlaanderen zendt zijn zonen uit ») ?

Voilà donc les questions que nous devons nous poser, auxquelles nous devons répondre, positivement et activement, tant que nous sommes en vie, tant que nous sommes actifs pour le bien-être de nos peuples.

Je vous remercie pour votre attention.

Robert Steuckers,

17 novembre 2018.

Sur le même sujet, à lire: http://robertsteuckers.blogspot.com/2018/06/geopolitique-de-la-belgique.html

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

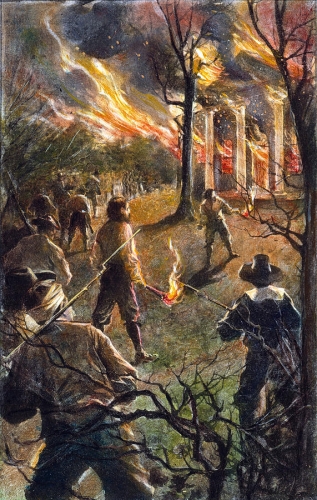

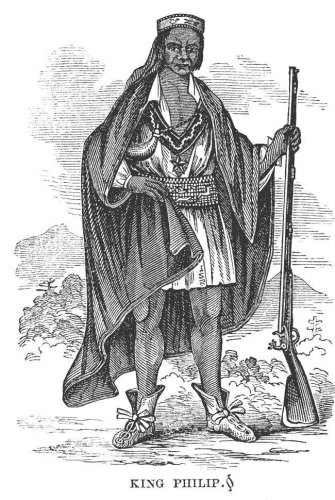

Edmund Morgan’s American Freedom, American Slavery and Jill Lepore’s The Name of War unintentionally provide identitarian accounts of their subjects. Both books won prestigious awards, and liberals continue tout them as classics. Morgan’s book examines the settling of Virginia and how the presence of non-whites influenced republicanism and American identity. Lepore’s book is a cultural and social history of King Philip’s War. Both works are written from a liberal perspective and mainly view whites as bad and non-whites as good. (Lepore’s book less so than Morgan’s.) Each book reveals that racial conflict shaped America.

Edmund Morgan’s American Freedom, American Slavery and Jill Lepore’s The Name of War unintentionally provide identitarian accounts of their subjects. Both books won prestigious awards, and liberals continue tout them as classics. Morgan’s book examines the settling of Virginia and how the presence of non-whites influenced republicanism and American identity. Lepore’s book is a cultural and social history of King Philip’s War. Both works are written from a liberal perspective and mainly view whites as bad and non-whites as good. (Lepore’s book less so than Morgan’s.) Each book reveals that racial conflict shaped America.

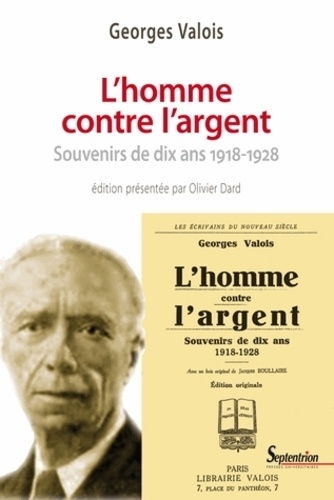

Il intègre sous ce terme l’ensemble des mouvements politiques européennes entre 1918 et 1945, y compris le national-socialisme allemand. Il complète son (assez) courte étude par trois annexes sur les relations entre le paganisme et le national-socialisme, les symboles fascistes et le mésusage par l’hitlérisme du mot « Aryen ». Ainsi Thomas Ferrier observe-t-il que le fascisme « idéal » se manifeste en une profusion de fascismes historiques, car « ce qui modifie le fascisme idéal en un fascisme historique, c’est le contexte politique et le contexte national (p. 91) ».

Il intègre sous ce terme l’ensemble des mouvements politiques européennes entre 1918 et 1945, y compris le national-socialisme allemand. Il complète son (assez) courte étude par trois annexes sur les relations entre le paganisme et le national-socialisme, les symboles fascistes et le mésusage par l’hitlérisme du mot « Aryen ». Ainsi Thomas Ferrier observe-t-il que le fascisme « idéal » se manifeste en une profusion de fascismes historiques, car « ce qui modifie le fascisme idéal en un fascisme historique, c’est le contexte politique et le contexte national (p. 91) ».

Ancien rédacteur à la Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire et auteur d’ouvrages sur les hérésies, Pierre de Meuse s’attaque à un continent historiographique, politique et culturel immense : la Contre-Révolution. Dans Idées et doctrines de la Contre-révolution (préface de Philippe Conrad, Éditions DMM, 2019, 410 p., 23,50 €), l’ancien militant passé par l’Action Française examine à partir de nombreuses sources l’histoire et la postérité de cet univers intellectuel.

Ancien rédacteur à la Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire et auteur d’ouvrages sur les hérésies, Pierre de Meuse s’attaque à un continent historiographique, politique et culturel immense : la Contre-Révolution. Dans Idées et doctrines de la Contre-révolution (préface de Philippe Conrad, Éditions DMM, 2019, 410 p., 23,50 €), l’ancien militant passé par l’Action Française examine à partir de nombreuses sources l’histoire et la postérité de cet univers intellectuel.

Sur le Kurfürstendamm, des étudiants iraniens manifestaient contre le Shah. Dans une librairie, je m’étais procuré un exemplaire du fameux livre d’Otto-Ernst Schüddekopf sur le national-bolchevisme de l’époque de la République de Weimar, un témoignage incontournable ; un quart d’heure plus tard, je m’attable à une terrasse pour compulser mes nouveaux bouquins. Je suis assis à une table collective et une dame âgée, souriante, arrive et me dit avec toute la gouaille berlinoise : « Bonjour jeune homme, accepteriez-vous qu’une vieille tarte (« eine alte Klatschtante ») comme moi s’assoie en face de vous ? ». Elle était d’une sombre élégance, coiffée d’un chapeau à la tyrolienne orné d’une superbe plume noire. Nous entamons une conversation et je vois qu’un sourire approbateur se dessine sur son visage jovial quand elle voit le type de littérature historique que je m’étais choisi. Elle a voulu me payer les bouquins. Et elle insistait. Confus, je décline son offre. Elle se lève me salue et laisse 30 marks sur la table. Je veux les lui rendre, elle s’éclipse en me lançant un « Ach, Quatsch ! » chaleureux… A Berlin-Est, je vois circuler de belles automobiles tchèques, à l’esthétique vintage, des Tatra. Sur la Place de la Gendarmerie, en ruine, des arbres avaient poussé sur les marches des deux églises, l’allemande et la huguenote.

Sur le Kurfürstendamm, des étudiants iraniens manifestaient contre le Shah. Dans une librairie, je m’étais procuré un exemplaire du fameux livre d’Otto-Ernst Schüddekopf sur le national-bolchevisme de l’époque de la République de Weimar, un témoignage incontournable ; un quart d’heure plus tard, je m’attable à une terrasse pour compulser mes nouveaux bouquins. Je suis assis à une table collective et une dame âgée, souriante, arrive et me dit avec toute la gouaille berlinoise : « Bonjour jeune homme, accepteriez-vous qu’une vieille tarte (« eine alte Klatschtante ») comme moi s’assoie en face de vous ? ». Elle était d’une sombre élégance, coiffée d’un chapeau à la tyrolienne orné d’une superbe plume noire. Nous entamons une conversation et je vois qu’un sourire approbateur se dessine sur son visage jovial quand elle voit le type de littérature historique que je m’étais choisi. Elle a voulu me payer les bouquins. Et elle insistait. Confus, je décline son offre. Elle se lève me salue et laisse 30 marks sur la table. Je veux les lui rendre, elle s’éclipse en me lançant un « Ach, Quatsch ! » chaleureux… A Berlin-Est, je vois circuler de belles automobiles tchèques, à l’esthétique vintage, des Tatra. Sur la Place de la Gendarmerie, en ruine, des arbres avaient poussé sur les marches des deux églises, l’allemande et la huguenote.

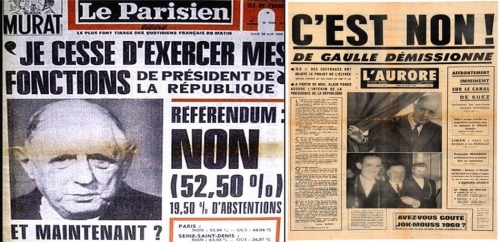

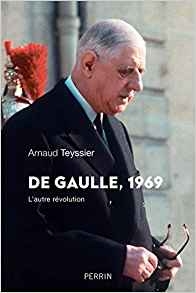

Déjà biographe de Louis-Philippe d’Orléans et de Philippe Séguin, véritable faux héros porté au pinacle par d’indécrottables droitards qui fit perdre en 1992 le non à Maastricht parce qu’il ne voulait pas heurté un François Mitterrand au sommet de sa ruse florentine, Arnaud Teyssier ne partage pas l’analyse convenue de la lassitude politique. Il insiste au contraire sur les dernières années d’un second mandat marqué par des coups d’éclat retentissants (retrait de l’OTAN en 1966, discours d’autodétermination à Phnom Penh en 1967, condamnation la même année de l’État d’Israël après la guerre-éclair des Six Jours, reconnaissance du combat canadien-français à Montréal). De Gaulle prend « la défense des identités nationales et des cultures face au grand nivellement qui s’annonce (p. 66) ». Son interprétation rejoint celle d’Anne et de Pierre Rouannet qui dans Les trois derniers chagrins du Général de Gaulle (Grasset, 1980) et dans L’inquiétude outre-mort du Général de Gaulle (Grasset, 1985) traitaient déjà de ces thèmes d’un point de vue original et pertinent.

Déjà biographe de Louis-Philippe d’Orléans et de Philippe Séguin, véritable faux héros porté au pinacle par d’indécrottables droitards qui fit perdre en 1992 le non à Maastricht parce qu’il ne voulait pas heurté un François Mitterrand au sommet de sa ruse florentine, Arnaud Teyssier ne partage pas l’analyse convenue de la lassitude politique. Il insiste au contraire sur les dernières années d’un second mandat marqué par des coups d’éclat retentissants (retrait de l’OTAN en 1966, discours d’autodétermination à Phnom Penh en 1967, condamnation la même année de l’État d’Israël après la guerre-éclair des Six Jours, reconnaissance du combat canadien-français à Montréal). De Gaulle prend « la défense des identités nationales et des cultures face au grand nivellement qui s’annonce (p. 66) ». Son interprétation rejoint celle d’Anne et de Pierre Rouannet qui dans Les trois derniers chagrins du Général de Gaulle (Grasset, 1980) et dans L’inquiétude outre-mort du Général de Gaulle (Grasset, 1985) traitaient déjà de ces thèmes d’un point de vue original et pertinent. Charles De Gaulle considère la participation comme l’élément décisif pour lier durablement le travail et le capital, association déjà revendiquée à l’époque « populiste » du RPF (Rassemblement du peuple français). Par participation, il entend « une forme de révolution dans l’exercice des décisions au sein des universités, au sein de l’entreprise, dans les régions. Il reconnaît implicitement que les mécanismes traditionnels de la démocratie représentative ne sont plus suffisants pour faire face au monde nouveau qui se profile (p. 85) ». En effet, « au-delà de son caractère singulier et déroutant, [Charles De Gaulle] représente à la perfection le modèle de l’homme d’État français qui dépasse, sans l’abolir, l’opposition traditionnelle entre droite et gauche et met au rebut le faux débat de la pensée contemporaine qui s’est développé en France autour du “ libéralisme ” et de l’« élitisme », ou du jacobinisme et de l’esprit girondin. Sa conception sacerdotale du gouvernement et de la chose publique défie toute idée préconçue (p. 20) ». Les années 1960 marquent l’apothéose du « libéralisme gaullien ». « Il s’agit d’un libéralisme “ national ”, ou d’un libéralisme d’État, car il s’inscrit dans une gestion de l’économie très largement dirigée, où la planification est l’élément stratégique pour les politiques industrielles (p. 81). » On est donc très loin de la participation imaginée comme une manière biaisée d’implanter des soviets dans toute la société.

Charles De Gaulle considère la participation comme l’élément décisif pour lier durablement le travail et le capital, association déjà revendiquée à l’époque « populiste » du RPF (Rassemblement du peuple français). Par participation, il entend « une forme de révolution dans l’exercice des décisions au sein des universités, au sein de l’entreprise, dans les régions. Il reconnaît implicitement que les mécanismes traditionnels de la démocratie représentative ne sont plus suffisants pour faire face au monde nouveau qui se profile (p. 85) ». En effet, « au-delà de son caractère singulier et déroutant, [Charles De Gaulle] représente à la perfection le modèle de l’homme d’État français qui dépasse, sans l’abolir, l’opposition traditionnelle entre droite et gauche et met au rebut le faux débat de la pensée contemporaine qui s’est développé en France autour du “ libéralisme ” et de l’« élitisme », ou du jacobinisme et de l’esprit girondin. Sa conception sacerdotale du gouvernement et de la chose publique défie toute idée préconçue (p. 20) ». Les années 1960 marquent l’apothéose du « libéralisme gaullien ». « Il s’agit d’un libéralisme “ national ”, ou d’un libéralisme d’État, car il s’inscrit dans une gestion de l’économie très largement dirigée, où la planification est l’élément stratégique pour les politiques industrielles (p. 81). » On est donc très loin de la participation imaginée comme une manière biaisée d’implanter des soviets dans toute la société. Dans cette perspective de téléologie politique, l’auteur met fort intelligemment en relation l’action de Charles De Gaulle et l’œuvre, en particulier théâtrale, de Henry de Montherlant. Il aurait pu aussi citer une anecdote donnée par Philippe de Saint-Robert. En attendant un essai nucléaire au large de Mururoa vers 1967 – 1968, le Général lisait dans sa cabine Le Chaos et la Nuit ! Cependant, personnalité « montherlaine », « peut-on dire que de Gaulle était une figure “ schmittienne ” ? (p. 271) » Arnaud Teyssier s’avance ici un peu trop vite quand il souligne que le gaulliste de gauche et professeur de droit constitutionnel, un temps enseignant à l’Université de Strasbourg, « René Capitant, qui fut l’une des personnalités les plus proches de De Gaulle, était un admirateur et un ami de Carl Schmitt (p. 272) ».

Dans cette perspective de téléologie politique, l’auteur met fort intelligemment en relation l’action de Charles De Gaulle et l’œuvre, en particulier théâtrale, de Henry de Montherlant. Il aurait pu aussi citer une anecdote donnée par Philippe de Saint-Robert. En attendant un essai nucléaire au large de Mururoa vers 1967 – 1968, le Général lisait dans sa cabine Le Chaos et la Nuit ! Cependant, personnalité « montherlaine », « peut-on dire que de Gaulle était une figure “ schmittienne ” ? (p. 271) » Arnaud Teyssier s’avance ici un peu trop vite quand il souligne que le gaulliste de gauche et professeur de droit constitutionnel, un temps enseignant à l’Université de Strasbourg, « René Capitant, qui fut l’une des personnalités les plus proches de De Gaulle, était un admirateur et un ami de Carl Schmitt (p. 272) ».

Jared Diamond is phoning it in. The legendary author of Guns, Germs, and Steel—the epic 1997 account of how Earth’s geography helped to determine the fates of the peoples who inhabit it—has produced a genuine mess of a book.

Jared Diamond is phoning it in. The legendary author of Guns, Germs, and Steel—the epic 1997 account of how Earth’s geography helped to determine the fates of the peoples who inhabit it—has produced a genuine mess of a book.

Les principaux manuels de géopolitiques, notamment celui que le Professeur David Criekemans a rédigé selon les critères de la plus haute scientificité dans le cadre de l’Université de Louvain, commencent presque toujours par une histoire de cette discipline depuis les premières tentatives de saisir conceptuellement les faits géographiques, non pas tant dans une perspective purement empirique mais surtout dans une perspective stratégique, notamment à l’aide de la cartographie établie par Carl Ritter, de l’anthropo-géographie de Ratzel ou des définitions données par le Suédois Rudolf Kjellén. C’est, personne ne le niera, un travail des plus utiles, ce qui était aussi mon intention lorsque feu le Professeur Jean-François Mattéi m’avait invité à présenter les penseurs de la géopolitique dans sa remarquable Encyclopédie des Œuvres philosophiques entre 1990 et 1992, encyclopédie qui fut ultérieurement publiée aux Presses Universitaires de France. L’intention du Prof. Mattéi correspondait à celle qu’avait déjà formulée le géopolitologue Yves Lacoste, à savoir élargir le cadre de la discipline, philosophique pour le premier, géographique/géopolitique pour le second. Mattéi voulait donc élargir le champ de la philosophie, tout simplement parce que plus aucune philosophie sérieuse ne peut encore être pensée sans tenir compte du temps et de l’espace, de l’émergence de tous les phénomènes, faits, modes de pensée et aspirations religieuses ou éthiques qui, tous, nécessairement, se déploient en des lieux et des périodes précises qu’ils influencent ensuite en profondeur, les inscrivant dans la durée et leur assurant une résilience difficilement éradicable.

Les principaux manuels de géopolitiques, notamment celui que le Professeur David Criekemans a rédigé selon les critères de la plus haute scientificité dans le cadre de l’Université de Louvain, commencent presque toujours par une histoire de cette discipline depuis les premières tentatives de saisir conceptuellement les faits géographiques, non pas tant dans une perspective purement empirique mais surtout dans une perspective stratégique, notamment à l’aide de la cartographie établie par Carl Ritter, de l’anthropo-géographie de Ratzel ou des définitions données par le Suédois Rudolf Kjellén. C’est, personne ne le niera, un travail des plus utiles, ce qui était aussi mon intention lorsque feu le Professeur Jean-François Mattéi m’avait invité à présenter les penseurs de la géopolitique dans sa remarquable Encyclopédie des Œuvres philosophiques entre 1990 et 1992, encyclopédie qui fut ultérieurement publiée aux Presses Universitaires de France. L’intention du Prof. Mattéi correspondait à celle qu’avait déjà formulée le géopolitologue Yves Lacoste, à savoir élargir le cadre de la discipline, philosophique pour le premier, géographique/géopolitique pour le second. Mattéi voulait donc élargir le champ de la philosophie, tout simplement parce que plus aucune philosophie sérieuse ne peut encore être pensée sans tenir compte du temps et de l’espace, de l’émergence de tous les phénomènes, faits, modes de pensée et aspirations religieuses ou éthiques qui, tous, nécessairement, se déploient en des lieux et des périodes précises qu’ils influencent ensuite en profondeur, les inscrivant dans la durée et leur assurant une résilience difficilement éradicable. Lacoste a prouvé que la géographie sert les chefs de guerre en démontrant que les premières tentatives de dessiner des cartes dans la Chine de l’antiquité servaient à indiquer les voies à suivre aux chefs de guerre, de manière à ce qu’ils puissent mouvoir leurs armées de manière optimale dans les paysages et terrains divers de leur propre pays ou dans le pays de l’ennemi. Ensuite, dans un livre succinct, mais rédigé de manière magistrale, il nous a montré que le Prince Henri du Portugal, Anglais par sa mère, a fondé et soutenu son « école de la mer » afin de trouver de nouvelles voies maritimes extra-méditerranéennes pour que l’écoumène chrétien/européen de son époque puisse trouver le chemin vers les épices indiennes et vers le mystérieux « Cathay » en échappant aux blocus terrestres et maritimes que lui imposait le contrôle turc/ottoman des accès aux routes continentales vers l’Asie et des voies maritimes en Méditerranée. Quelques décennies plus tard, les Portugais livreront bataille dans la Corne de l’Afrique et des navires lusitaniens surgiront face aux côtes du Gujarat en Inde pour vaincre glorieusement une flotte musulmane. Tant les seigneurs de la guerre que les empereurs chinois du monde antique et que le Prince Henri du Portugal ont donc fait dessiner des cartes pour que des militaires ou des marins avisés puissent mener la guerre ou des expéditions exploratrices de manière optimale. Le raisonnement de Lacoste est parfaitement exact, et fut posé en dépit de son engagement idéologique dans les rangs de la gauche pacifiste.

Lacoste a prouvé que la géographie sert les chefs de guerre en démontrant que les premières tentatives de dessiner des cartes dans la Chine de l’antiquité servaient à indiquer les voies à suivre aux chefs de guerre, de manière à ce qu’ils puissent mouvoir leurs armées de manière optimale dans les paysages et terrains divers de leur propre pays ou dans le pays de l’ennemi. Ensuite, dans un livre succinct, mais rédigé de manière magistrale, il nous a montré que le Prince Henri du Portugal, Anglais par sa mère, a fondé et soutenu son « école de la mer » afin de trouver de nouvelles voies maritimes extra-méditerranéennes pour que l’écoumène chrétien/européen de son époque puisse trouver le chemin vers les épices indiennes et vers le mystérieux « Cathay » en échappant aux blocus terrestres et maritimes que lui imposait le contrôle turc/ottoman des accès aux routes continentales vers l’Asie et des voies maritimes en Méditerranée. Quelques décennies plus tard, les Portugais livreront bataille dans la Corne de l’Afrique et des navires lusitaniens surgiront face aux côtes du Gujarat en Inde pour vaincre glorieusement une flotte musulmane. Tant les seigneurs de la guerre que les empereurs chinois du monde antique et que le Prince Henri du Portugal ont donc fait dessiner des cartes pour que des militaires ou des marins avisés puissent mener la guerre ou des expéditions exploratrices de manière optimale. Le raisonnement de Lacoste est parfaitement exact, et fut posé en dépit de son engagement idéologique dans les rangs de la gauche pacifiste. Mais s’il existe des permanences immuables en géopolitique, comment devons-nous repérer celles qui se manifestent dans le cadre géographique de nos bas pays ? La méthode, que je souhaite utiliser ici, et que j’ai toujours utilisée notamment dans l’écriture de ma trilogie, qui porte pour titre Europa, est celle d’un géopolitologue non politisé du temps de la République de Weimar. Son nom était Richard Henning (1874-1951), auteur d’un ouvrage très copieux, Geopolitik – Die Lehre vom Staat als Lebewesen, qui a connu cinq éditions successives. Henning avait une écriture très claire, limpide, n’utilisait jamais un jargon compliqué et illustrait chacun de ses arguments par des cartes précises. Au départ, sa discipline était la géographie des communications et des transports, renforcée par une géographie historique, où il mettait toujours l’accent sur le rôle des états, des hommes d’état et des surdoués politiques dans l’organisation et la transformation des espaces. Sa thèse centrale était de dire, à son époque, que les données spatiales d’un peuple devaient être davantage valorisées conceptuellement plutôt que les facteurs raciaux, ce qui le fit entrer en conflit avec les thèses officielles du pouvoir sous le Troisième Reich, même si, Prussien natif de Berlin, il défendait le principe clausewitzien d’une nécessaire militarisation défensive de tout état, en tenant compte, bien sûr, du vieil adage romain, Si vis pacem, para bellum. Dans les années 50 et 60 du 20ème siècle, son œuvre exerça une influence importante en Argentine sous le régime du Général Juan Peron et, plus tard, s’est retrouvée en filigrane dans les cours des écoles militaires du pays.

Mais s’il existe des permanences immuables en géopolitique, comment devons-nous repérer celles qui se manifestent dans le cadre géographique de nos bas pays ? La méthode, que je souhaite utiliser ici, et que j’ai toujours utilisée notamment dans l’écriture de ma trilogie, qui porte pour titre Europa, est celle d’un géopolitologue non politisé du temps de la République de Weimar. Son nom était Richard Henning (1874-1951), auteur d’un ouvrage très copieux, Geopolitik – Die Lehre vom Staat als Lebewesen, qui a connu cinq éditions successives. Henning avait une écriture très claire, limpide, n’utilisait jamais un jargon compliqué et illustrait chacun de ses arguments par des cartes précises. Au départ, sa discipline était la géographie des communications et des transports, renforcée par une géographie historique, où il mettait toujours l’accent sur le rôle des états, des hommes d’état et des surdoués politiques dans l’organisation et la transformation des espaces. Sa thèse centrale était de dire, à son époque, que les données spatiales d’un peuple devaient être davantage valorisées conceptuellement plutôt que les facteurs raciaux, ce qui le fit entrer en conflit avec les thèses officielles du pouvoir sous le Troisième Reich, même si, Prussien natif de Berlin, il défendait le principe clausewitzien d’une nécessaire militarisation défensive de tout état, en tenant compte, bien sûr, du vieil adage romain, Si vis pacem, para bellum. Dans les années 50 et 60 du 20ème siècle, son œuvre exerça une influence importante en Argentine sous le régime du Général Juan Peron et, plus tard, s’est retrouvée en filigrane dans les cours des écoles militaires du pays. Par suite, si je privilégie l’exemple d’un historien-géographe comme Henning dans ma façon de raisonner en termes géopolitiques, je dois me limiter aux bas pays dans un exposé aussi bref que celui que je vais tenir aujourd’hui à Louvain, car il m’est impossible de parler de tous les pays qu’Henning a étudiés. Le temps qui m’est accordé est de fait limité et mon exposé se bornera à suggérer un certain nombre de pistes que nous devrons, ultérieurement, approfondir tous ensemble. Dans un ouvrage relativement récent de l’historien britannique Michael Pye, The Edge of the World – How the North Sea Made Us Who We Are (Viking/Penguin, London, 2014), nous trouvons, très largement esquissé, un cadre historique précis dans lequel Pye suggère l’émergence d’une histoire culturelle particulière qui se déploie, du moins au tout début de notre histoire, entre l’Islande et Calais et entre le Skagerrak danois/norvégien et les eaux de la Mer Baltique. Pour Pye, c’est en cette région que nait un monde à part, qui entretient certes des contacts, d’abord ténus, avec l’espace méditerranéen tout en restant plutôt autonome dans ses limites intérieures et où Bruges en constitue la plaque tournante méridionale à proximité du Pas-de-Calais. La Flandre médiévale abrite de ce fait le port principal de cette région de la Mer du Nord et de la Baltique qui doit nécessairement entretenir des contacts avec la Normandie, la Bretagne et surtout les côtes atlantiques du nord de l’Espagne, principalement le Pays Basque puis le Portugal, libéré par des croisés venus justement de toutes les régions du pourtours de la Mer du Nord, opération réussie dès le 12ème siècle qui démontre qu’il y avait une visée géopolitique implicite cherchant à étendre l’écoumène nordique à toutes les côtes de l’Atlantique européen. Cette Flandre prospère, pointe avancée vers le sud de cet espace nordique défini par Pye, cherche aussi à ouvrir une voie terrestre entre le Pays Basque et la Catalogne, sur le cours de l’Ebre, voie la plus courte vers les produits de la Méditerranée à une époque où la péninsule ibérique est encore sous contrôle musulman et ne peut être contournée sans danger.

Par suite, si je privilégie l’exemple d’un historien-géographe comme Henning dans ma façon de raisonner en termes géopolitiques, je dois me limiter aux bas pays dans un exposé aussi bref que celui que je vais tenir aujourd’hui à Louvain, car il m’est impossible de parler de tous les pays qu’Henning a étudiés. Le temps qui m’est accordé est de fait limité et mon exposé se bornera à suggérer un certain nombre de pistes que nous devrons, ultérieurement, approfondir tous ensemble. Dans un ouvrage relativement récent de l’historien britannique Michael Pye, The Edge of the World – How the North Sea Made Us Who We Are (Viking/Penguin, London, 2014), nous trouvons, très largement esquissé, un cadre historique précis dans lequel Pye suggère l’émergence d’une histoire culturelle particulière qui se déploie, du moins au tout début de notre histoire, entre l’Islande et Calais et entre le Skagerrak danois/norvégien et les eaux de la Mer Baltique. Pour Pye, c’est en cette région que nait un monde à part, qui entretient certes des contacts, d’abord ténus, avec l’espace méditerranéen tout en restant plutôt autonome dans ses limites intérieures et où Bruges en constitue la plaque tournante méridionale à proximité du Pas-de-Calais. La Flandre médiévale abrite de ce fait le port principal de cette région de la Mer du Nord et de la Baltique qui doit nécessairement entretenir des contacts avec la Normandie, la Bretagne et surtout les côtes atlantiques du nord de l’Espagne, principalement le Pays Basque puis le Portugal, libéré par des croisés venus justement de toutes les régions du pourtours de la Mer du Nord, opération réussie dès le 12ème siècle qui démontre qu’il y avait une visée géopolitique implicite cherchant à étendre l’écoumène nordique à toutes les côtes de l’Atlantique européen. Cette Flandre prospère, pointe avancée vers le sud de cet espace nordique défini par Pye, cherche aussi à ouvrir une voie terrestre entre le Pays Basque et la Catalogne, sur le cours de l’Ebre, voie la plus courte vers les produits de la Méditerranée à une époque où la péninsule ibérique est encore sous contrôle musulman et ne peut être contournée sans danger.

Les ducs de Bourgogne essaieront, par une politique habile, de ressusciter l’Empire de Lothaire mais sans succès. Pour comprendre la dynamique de l’histoire européenne dans nos régions, nous devons donc, aujourd’hui, étudier la géopolitique implicite de ces ducs qui entendaient consolider une alliance avec l’Angleterre et englober la Lorraine et l’Alsace dans leur orbite politique afin de joindre leurs possessions de l’ancienne Basse Lotharingie (« Pays de Par-Deça ») avec celles de l’ancienne Haute Lotharingie et de la Bourgogne (fief français inclus dans la Francie occidentale de Charles le Chauve). Cependant, dans cette étude, nous ne devons surtout pas oublier que la tête pensante de cette géopolitique bourguignonne a été Isabelle de Portugal (ou Isabelle de Bourgogne), épouse de Philippe le Bon et mère de Charles le Hardi (dit le « Téméraire » en France). Isabelle de Portugal était la sœur du Prince Henri, dit « Henri le Navigateur », fils du roi du Portugal et de Philippine de Lancaster, princesse anglaise. Le Prince Henri (1394-1460) a fondé son école maritime, école géopolitique avant la lettre, à Sagres au Portugal, dans le but de créer les conditions requises pour le développement de flottes de haute mer et de mobiliser tous les savoirs pratiques disponibles pour pouvoir, à terme, contourner les empires musulmans et trouver de nouvelles voies vers l’Inde et la Chine. Yves Lacoste, fondateur de la revue Hérodote et pionnier de la redécouverte des théories géopolitiques en France à partir des années 1970, a consacré une bonne part de son livre sur l’histoire de la cartographie à la figure d’Henri le Navigateur et a ainsi démontré que ce prince fut l’impulseur premier de la conquête européenne du monde.