Malgré l’envahissement des sociétés modernes et, en conséquence, de l’existence quotidienne par les sciences et les techniques, le chevalier demeure un personnage exemplaire car nimbé d’un prestige qui joint les contingences de l’humain aux orbes de la métaphysique. Prestige qui, dans toute l’Europe et bien au-delà, devait survivre à la disparition de l’ancien régime royal et féodal ou, selon les nations, à sa transformation en monarchie constitutionnelle. C’est pourquoi, par exemple, la République française a le pouvoir de conférer, entre autres, le titre de « chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur ». De plus, à travers notre « vieux continent », comme disent les natifs d’outre Atlantique (qui, eux aussi, associent médailles et chevalerie), des ordres célèbres issus du Moyen Âge – de la Toison d’Or à la Jarretière en passant par Calatrava – existent toujours. Tout cela semble dire que l’image du chevalier manifeste quelque chose de fondamental et, de la sorte, d’indissociable de l’identité européenne.

Dans l’imagination populaire, où se télescopent reliquats de l’Histoire, séquences de cinéma, séries télé et album de B.D. (pardon, de « romans graphiques », selon la dénomination désormais académique), le chevalier est un personnage possédant un ensemble de qualités qui font de lui un être hors du commun, différencié du troupeau de l’humanité ordinaire. À l’exemple de Bayard, « sans peur et sans reproches », on l’imagine prêt à défendre « la veuve et l’orphelin » ; il est le « chic type » qui, semblablement à Martin de Tours, saint patron de notre nation, se montre immédiatement secourable au malheureux quémandant secours. Jadis, il y a trente ans, tout personnage sympathique et courageux qui, de façon fictionnelle ou tangible captivait le public, participait un peu – sinon beaucoup – de la figure du chevalier. Ainsi, sur le petit écran, Tanguy et Laverdure étaient-ils Les Chevaliers du ciel, tandis que le refrain du générique de Starsky et Hutch qualifiait ces policiers de « chevaliers qui n’ont jamais peur de rien ! ». Certes, la comparaison est outrée mais néanmoins fort significative. De façon émouvante, Georges Rémi, alias Hergé, en rédigeant une lettre à son fils Tintin, écrit que la carrière qui attendait ce dernier devait être journalistique mais qu’en réalité elle fut au service de la chevalerie (1). Et même dans l’univers futur que déploie la plus célèbre saga du Septième Art – Star Wars, rassemblant des fans par millions sur toute la planète – l’harmonie et la pax profunda galactique dépendent de l’ordre de chevalerie Jédi.

« CHEVALIER » RIME AVEC « JUSTICIER »

Nous avons brièvement fait allusion aux qualités du chevalier. Trois d’entre elles émergent et caractérisent le comportement existentiel de ce personnage. En premier le courage, ce « cœur » immortalisant le Rodrigue de Pierre Corneille et qui, dans l’esprit des anciens, impliquait aussi la générosité. Le courage se raréfiant, il ne reste du « cœur » que sa synonymie de générosité ; ce qu’illustre « les restos du cœur » à l’initiative de Coluche. Selon le monde médiéval, celui qui n’est pas avare de son sang est obligatoirement généreux. En second intervient la droiture, qualité exigeant que l’on ne transige pas et que symbolise l’épée du chevalier. Puis s’impose l’humilité, car le chevalier véritable s’interdit tout sentiment d’orgueil, toute hubris aurait dit les Grecs par la voix d’Hésiode. Courage, droiture et humilité, ouvrent une brèche dans la densité de ce que d’aucuns, usant d’un néologisme, nommeront l’ « égoïté », le haïssable « moi-je ». Par ces trois notions, le chevalier prend ses distances d’avec « l’humain trop humain », insatiable accumulateur de médiocrité, dénoncé par Fréderic Nietzsche, le « philosophe au marteau ».

Refuser l’hubris et même la combattre farouchement, tant en soi-même qu’à l’extérieur, dans la société, implique de vivre guidé par la diké, c’est-à-dire la justice, affirme encore Hésiode (2). De fait, le chevalier est, par excellence, l’individu qui s’efforce d’avoir en toute circonstance une attitude juste. Gouvernant spirituellement la chevalerie, saint Michel archange tient, comme Thémis, la balance et l’épée. Parce qu’il préside à la psychostasie du Jugement Dernier, la seule référence à sa personne nécessite de se comporter avec équité. Le chevalier est obligatoirement un justicier.

Nous venons de citer Hésiode à propos de ces antinomiques polarités que constituent l’hubris et la dyké. Il nous faut revenir sur ce que cet auteur en dit afin de découvrir l’un des soubassements possibles de la chevalerie. Hésiode considère en effet que l’hubris est symptomatique d’une humanité éloignée de l’Âge d’Or. Toutes les conséquences négatives de cette démesure de l’« égoïté » allaient se précipiter durant le dernier Âge voué au métal du dieu de la guerre, Arès. C’est la raison pour laquelle Zeus, dont Thémis fut une épouse, donna naissance aux héros « ceux-là mêmes qu’on nomme demi-dieux » (3). Les armes à la main, ils œuvrent pour la dyké, même si certains d’entre eux sombrent parfois dans l’hubris (4). Ancêtre d’Héraclès, le modèle même du héros pourrait se nommer Persée. Il annonce les chevaliers de légende en ce que, vainqueur de deux monstres, on le voit brandir l’épée et monter Pégase, le plus mythique de tous les chevaux (5) puisque les ailes dont il est pourvu font que son galop devient un envol. Blasonnant de la tête de Méduse (6), le bouclier offert par Athéna, Persée se révèle un justicier dès lors qu’il renverse la tyrannie que Polydectès exerçait sur l’île de Sériphos et qu’il chassera Acrisios de la cité d’Argos. Le mythe de Persée est apparu d’une telle importance aux yeux des Grecs que pas moins de cinq constellations, sur les quinze principales constituant l’hémisphère boréal, au-dessus du zodiaque, lui sont consacrées (7). C’est également porté par Pégase que Bellérophon affrontera une horreur — et erreur — génétique, la chimère.

LE CHEVAL ET L’ÉPÉE

L’équipement du chevalier pourrait se ramener à sa monture et à l’épée (8). Dans l’ancien monde, tout objet, parallèlement à sa destination utilitaire, pouvait revêtir une signification symbolique. Cette omniprésence du symbole contribuait à une mise en mémoire de ce qui s’imposait comme essentiel, fondamental même, pour les individus et la société qu’ils composaient. Un cheval ou une épée relèvent de l’utilitaire : avec un coursier, on augmente les possibilités de couvrir de longues distances et, par une arme, on peut sauvegarder son intégrité corporelle. Mais l’animal et l’objet se chargent également de significations symboliques explicitant ce que Mircea Eliade nommerait un « changement radical de statut ontologique » (9).

Le cheval, « la plus belle conquête de l’homme » selon un dicton bien connu, permet donc d’aller plus vite et plus loin. Ce qui sous-entend que le dressage de l’équidé confère une capacité à outrepasser le conditionnement temporel et spatial. La monture représente le corps d’un individu – sa composante animale (10) – et l’équitation est métaphorique d’une totale maîtrise des instincts inhérents au corps. La maîtrise, voilà le mot clef. Le chevalier idéal se distingue du commun des mortels ou même d’un simple cavalier par la faculté de se dominer, de posséder le commandement absolu sur son corps et sur le psychisme que conditionne la densité physiologique (11). Ajoutons que le déplacement du cheval s’opère selon un triple mode : le pas, le trot et le galop. Le pas s’accorde au rythme de l’homme et, par conséquent, au monde des corps physiques, au domaine matériel qui nous entoure. Le trot représenterait le monde subtil, celui de l’âme ou, si l’on préfère et pour se rapprocher de l’interprétation des anciens, du « Double », le corps de nature subtile, la « physiologie mystique » (12) dirait encore Eliade. Enfin, le galop qui, métaphoriquement, à l’image de Pégase, faisant que le coursier s’envole, correspond à l’illimité des corps glorieux, là où règne la pure lumière divine (13). Ces trois états résument la constitution de l’être et de ce qui, au-delà du perceptible, appartient à l’éternité.

Celui qui possède la maîtrise qu’illustre l’équitation a le droit de porter une arme, en l’occurrence l’épée. Par la brillance de sa lame, l’épée apparaît métaphorique d’un éclairement car l’acier bien fourbi reflète la lumière et se confond avec. Comme le note Gilbert Durand, cette arme — surtout brandie par un chevalier — se mue en un « symbole de rectitude morale » (14). Dans Le Conte du Graal de Chrétien de Troyes, le maître d’armes de Perceval, lors de l’adoubement chevaleresque de son élève, lui dit qu’avec l’épée « il lui confère l’ordre le plus élevé que Dieu ait établi et créé, l’ordre de chevalerie qui n’admet aucune bassesse » (15). Gilbert Durand ajouterait que « La transcendance est toujours armée » (16). D’autant plus que dans le symbolisme chrétien, saint Paul nous le rappelle (17), l’épée c’est le Verbe ; ce que confirme saint Jean l’Évangéliste lors de sa vision d’un être au corps glorieux dont le visage ressemblait « au soleil lorsqu’il luit dans sa force » tandis que « de sa bouche sortait un glaive aigu à double tranchant » (18). Le Verbe, autrement dit la parole, ce qui implique l’écriture et les mots qui naissent des lettres, se change en épée ; comme pour dire que, selon l’ancien monde, le langage à la source d’une civilisation est indissociable de la lumineuse rectitude joignant, par l’ethos qu’elle nécessite, l’humain au divin.

Prenant en quelque sorte le relais des helléniques pourfendeurs de monstres, le Christianisme suscite, sous l’autorité de l’Archange de justice, toute une phalange de saints combattants : Georges, Théodore, Victor, si bien nommé, ou encore Véran. À côté de ces bienheureux en armes, le chevalier idéal, tel que le Moyen Âge l’a imaginé et que le monde moderne en rêve encore, s’oriente spirituellement vers une source de clarté divine. D’autant plus qu’à la même époque, passage du XIIè au XIIIè siècle, surgissent les cathédrales gothiques – vouée à la lumière de par la prépondérance des vitraux — et toute une littérature chevaleresque consacrée à un objet illuminant comme l’astre diurne et synonyme de suprême connaissance : le Graal.

Pour les auteurs de ces récits en vers ou en prose, il ne fait aucun doute que le but et l’idéal de toute chevalerie consiste à rejoindre un calice miraculeux. Mais qu’est-ce que le Graal ? Le symbole d’une transformation radicale de l’être, sa rencontre avec le principe divin qu’il porte en lui. Mon regretté maître en Sorbonne, Jean Marx, disait que la signification du Graal était exposée sur une pièce archéologique d’une extrême importance découverte au Danemark et datée du premier siècle avant notre ère. Il s’agit du célèbre chaudron celtique de Gundestrup (19) dont la signification rituelle ne fait aucun doute puisque huit divinités, occupant sa surface extérieure, le situe symboliquement in medio mundi dès lors qu’elles semblent regarder vers les directions cardinales et intermédiaires de l’espace.

Une scène décorant l’intérieur révèle ce que sous-entend la chevalerie. Même si l’image qui va retenir notre attention est très antérieure à l’institution chevaleresque, elle traduit très précisément la symbolique du Graal (20). Cette scène est séparée en deux registres par un motif végétal disposé à l’horizontale. Le registre inférieur montre une file de guerriers s’avançant, sous la conduite d’un officier ou, peut-être, d’un officiant, vers un personnage d’une taille formidable qui les empoignent l’un après l’autre pour les tremper, tête la première, dans un récipient disposé devant lui. Pareil personnage n’est autre que le Dagda (littéralement, « dieu bon »), maître de l’éternité, du savoir total et des guerriers (21). Ce récipient, l’un des attributs du dieu, est le chaudron d’abondance (22), de résurrection et d’immortalité. De cette « trempe », les guerriers ressortent, sur le registre supérieur, d’une part, changés en cavaliers et, d’autre part, casqués : ce ne sont plus de simples fantassins, les pieds en contact avec la terre, mais des êtres que la maîtrise d’une monture emporte en sens inverse que leurs compagnons du registre inférieur. Quant au casque les coiffant, sa signification pourrait être la suivante : de par le fait que la tête de chacun de ces guerriers a été plongée dans le chaudron, ils ressortent le mental désormais protégé, armé, « blindé » pourrait-on dire et, de la sorte, définitivement à l’abri de toute faiblesse (23). Ajoutons que les différents motifs ornant les casques (un oiseau, un sanglier, des cornes de cerf et un cimier en crin de cheval) personnalisent chacun des cavaliers, comme le ferait un blason (24). Cette cavalerie issue d’une seconde naissance – spirituelle – annonce la chevalerie du Graal.

On pourrait dire que, par l’ascèse chevaleresque, se produit intérieurement une distanciation d’avec cette « égoïté » déjà mentionnée. Distanciation faisant éclore des états de conscience que l’ancien monde assimilait à un autre corps, de nature non plus physique, bien entendu, mais subtile. Selon les peuples, on l’a nommé eidolon (dans la Grèce antique), delba (chez les Celtes d’Irlande), hamr ou, sous son aspect supérieur, fylgja (chez les Vikings) et Régis Boyer, approfondissant l’étude de ces deux derniers termes, intitule précisément son ouvrage Le Monde du Double (25). La tradition chrétienne ne fera pas exception puisque l’âme sera perçue comme la duplication immatérielle du corps physique ainsi que, par exemple, le montre un chapiteau de la basilique romane de Vézelay représentant la mort d’un avare. Un petit personnage à l’image du mourant sort de sa bouche, illustrant ainsi la formule « rendre l’âme ».

Ce thème du Double est explicite dans la mythologie grecque avec les Dioscures. Castor, le mortel, accède à l’immortalité par son frère Pollux qui, lui, est immortel. Précision importante, ils patronnent les cavaliers et, au ciel étoilé, constituent le signe astrologique des Gémeaux. Le symbolisme qu’exprime cette figure céleste sera repris par le Moyen Âge puisque Castor et Pollux sont sculptés au portail occidental de la cathédrale de Chartres sous l’aspect de deux jeunes gens qui, par un geste rituel (26), sont positionnés de telle façon que chacun apparaît comme le reflet de l’autre dans un miroir. Ils tiennent devant eux un écu. Un unique écu alors qu’ils sont deux ? Ce qui signifie bien qu’il n’y a en réalité qu’un seul personnage. Plus tardif (XIIIè siècle) que cette sculpture mais s’en inspirant peut-être, l’un des sceaux de l’Ordre du Temple montre deux chevaliers tout équipés montés sur un même cheval (27). Remplaçant l’unique écu, la monture laisse supposer qu’il n’y a en réalité qu’un cavalier mais figuré avec son Double – rendu visible – comme à Chartres. Ainsi que le fit remarquer Gilbert Durand après publication de l’un de mes ouvrages (28), cette image de deux combattants sur la même monture rappelle fortement ce que l’on voit sur deux pièces archéologiques datant de la période des invasions germaniques et découvertes en des lieux éloignés l’un de l’autre (29). Elles montrent exactement la même figuration d’un cavalier renversant son adversaire tandis que, derrière lui sur le cheval, un personnage de taille réduite l’aide à tenir fermement sa lance dans le combat. Ce personnage n’est autre que sa fylgja (littéralement, « accompagnatrice »), terme évoqué plus haut et désignant le Double ou corps subtil d’un être (30).

Durant l’expédition des Argonautes, les têtes de Castor et Pollux furent illuminées par le phénomène appelé « feu de Saint Elme ». Ce qui fait immédiatement songer à la descente du feu du Saint Esprit sur tête des Apôtres lors de la Pentecôte, fête célébrée au début ou, approximativement, au milieu de la période astrologique des Gémeaux. Or, c’est précisément ce moment de l’année que choisit l’enchanteur Merlin pour créer la fameuse Table Ronde destinée à rassembler les meilleurs d’entre les chevaliers. Ainsi que nous l’avons dit dans d’autres études, Merlin pourrait être considéré comme bien autre chose qu’un sage doté d’un prodigieux savoir. On l’a considéré comme l’héritier et le continuateur du druidisme. Disons que, comme son nom latinisé (chez Geoffroy de Monmouth) l’indique, il serait le détenteur de ce que l’on nomme, depuis René Guénon, la Tradition primordiale (31) synonyme d’Âge originel ou, pour se référer une fois encore à Hésiode, d’Âge d’Or.

Ce n’est pas non plus par hasard si Chrétien de Troyes, dans le récit qui inaugure le cycle du Graal, fait arriver son héros, Perceval, dans un énigmatique château — véritable temple de la connaissance suprême — un soir de Pentecôte (32). Là, il assistera au cortège du Graal. Dans diverses études, il nous a été donné de montrer toute l’importance de ce singulier procession où sont portés cinq objets éminemment symboliques. Il ne fait guère de doute que l’auteur de ce récit compose une scène d’une importance extrême permettant d’entrevoir à quelle signification d’ordre initiatique se réfère ce modèle idéal de chevalerie qu’illumine le Graal. Nous en sommes arrivés à la conclusion suivante : par la disposition des cinq personnages qui le constituent, ce cortège stylise la silhouette de quelqu’un se tenant debout et levant ses bras en V, de façon à former un caractère runique, le quinzième de l’écriture germanique de la période des invasions. On pourrait s’étonner du rapprochement que nous établissons entre cette lettre d’un alphabet païen qui avait disparu depuis six siècles au moins et ce conte médiéval tout empreint de religiosité christique. Mais ce serait oublier ce qui a été dit un peu plus haut concernant l’image du combattant chevauchant avec sa fylgja et que l’on retrouve sur le sceau templier. D’autant plus que le caractère runique tracé par le cortège du Graal renvoie à la symbolique des Dioscures version germanique (33), comme le font remarquer d’éminents runologues parmi lesquels Lucien Musset (34) et Wolfgang Krause (35). De plus, Chrétien de Troyes introduit dans ce cortège une composante directement allusive aux Gémeaux. En effet, après le porteur de la lance qui saigne surnaturellement (36), « parurent deux autres jeunes gens tenant des chandeliers d’or pur (…) Ces jeunes gens, qui tenaient les chandeliers, étaient d’une grande beauté » (37). Nous sommes tentés de dire que cette beauté fait songer à Castor et Pollux puisqu’on les représente, nous dit P. Commelin, « sous la figure de robustes adolescents d’une irréprochable beauté » (38).

Si l’on admet que le cortège du Graal stylise à l’extrême la silhouette d’un personnage aux bras levés, le précieux calice occupe la place du cœur. Le Graal étant d’or fin (39), on pourrait dire qu’il évoque l’Âge que blasonne ce même métal. D’une part, le cortège trace la silhouette du Double et, d’autre part, le Graal, en constituant le cœur de cette autre corporéité, annonce la transformation du Double en corps glorieux et, de la sorte, la réintégration de l’Âge d’Or (40).

À travers les images chargées de symboles des récits arthuriens, le but initiatique de la chevalerie consistait à proposer une vision héroïque de l’existence tournée vers l’idée d’une possible restauration des temps primordiaux. Restauration qu’énoncent le Grec Hésiode ou le Romain Virgile (41) et qui, dans l’Apocalypse de Jean, se traduit par l’apparition de la Jérusalem céleste dont le matériaux singulier — cet « or pur, pareil à du pur cristal » (42) – est évocateur de l’Âge originel. Chrétien de Troyes fait allusion au fait que l’Âge comparé au métal solaire reviendra et, ainsi, ensevelira celui voué au Fer ; et ce par l’armure du chevalier destiné à restaurer le royaume du Graal. En effet, Perceval porte un haubert dont les mailles de fer sont recouvertes d’or (43).

L’image du chevalier idéal se présente donc comme indissociables d’un supposé Âge d’Or. Dans l’imaginaire médiéval, ce thème d’un commencement merveilleux fit se confondre le Jardin d’Éden et des données issues du paganisme telles que l’apollinienne Hyperborée ou les îles du Nord du monde du légendaire irlandais (44). C’est probablement la raison pour laquelle la légende envoie saint Brandan découvrir le Paradis terrestre dans une région septentrionale sinon polaire (45). L’éthique chevaleresque pourrait alors être définie comme la tentative de parvenir à cette rupture de niveau ontologique qu’énonce Éliade et qui, tout en suscitant la mémoire des origines, ferait en sorte de préparer à un retour du fondement originel de toute civilisation. Issu de l’Antiquité et repris par le Moyen Âge cette conception de l’existence et de l’Histoire replace l’identité européenne dans un contexte non point évolutionniste mais conforme à ce que l’on pu nommer, avec René Guénon, la Tradition.

Paul-Georges SANSONETTI

- Diplômé de l’Ecole du Louvre,

- Diplômé de l’Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes,

- Doctorat de Lettres de 3eme Cycle

————————————

NOTES :

(1) Lettre reproduite dans l’ouvrage de Numa Sadoul intitulé Tintin et moi, entretiens avec Hergé, Editions Casterman (2000), p. 254.

(2) Cf. Jean-Pierre Vernant, Mythe et pensée chez les Grecs, Editions Maspéro (Paris, 1965), p. 18.

(3) Dans Les Travaux et les Jours, Editions Librairie Générale Française (Paris, 1999), p. 102, vers 157-160.

(4) Ainsi, sous les murs de Troie, pour certains d’entre eux.

(5) Avec Sleipnir (littéralement, « Glissant »), le cheval à huit jambes du dieu scandinave Odinn. Or, Odinn est le maître de la noblesse, classe sociale destinée à incarner la fonction guerrière et, selon les circonstances, à assumer l’autorité spirituelle que confèrent des étapes initiatiques.

(6) On sait que le regard de Méduse, la Gorgone, changeait en pierre les infortunés qui la rencontraient. Persée en la décapitant grâce aux armes divines (le bouclier miroir donné par Athéna et le glaive par Hermès) montre qu’il est capable de neutraliser la pétrification qu’opère cette créature monstrueuse dont, se confondant avec sa chevelure, les nœuds de vipères traduisent un mental horriblement venimeux. Cette neutralisation de ce que l’on nommerait un pouvoir incapacitant donne naissance à Pégase, autrement dit à la jonction entre terre et ciel ou, si l’on préfère, entre les humains (mortels) et les Olympiens (immortels). La sienne (tenant la tête de Méduse), Pégase, Danaé et ses parents, Céphée et Cassiopée.

(8) La lance accompagne souvent l’épée mais sa signification est la même. Dans les deux cas, il s’agit d’une arme droite symbolisant la rectitude.

(9) Dans Le sacré et le Profane, Edition Gallimard (Paris, 1969), p. 156.

(10) Telle est probablement la signification du centaure, créature tantôt négative, l’être prisonnier de ses pulsions animales (on songe à ces centaures ivres qui s’emparent des femmes Lapithes ou encore à Nessus enlevant Déjanire), tantôt exemplaire si les instincts sont totalement maîtrisés (ainsi pour Chiron, initiateur d’Héraclès et d’Achille, devenu le signe astrologique du Sagittaire).

(11) On aura compris que l’équitation est métaphorique du yoga. De plus, la représentation de la Tempérance montre que cette figure féminine tient un mors comme attribut emblématique. Sur ce thème, cf P-G. Sansonetti, Chevalerie du Graal et Lumière de Gloire, Editions Exèdre (Menton, 2004), p. 240 et suivantes.

(12) Dans Le Yoga, immortalité et liberté, Editions Payot (Paris, 1968), p. 239.

(13) Sur un plan iconographique médiéval, ce monde radieux car divin est traduit par l’auréole dorée des saints personnages et par le ciel d’or entourant les figures de la Trinité ou les entités angéliques. Ce même procédé intervient dans les mosaïques byzantines et dans l’art orthodoxes ainsi que dans certaines miniatures persanes ; cf Henri Corbin, Terre céleste et Corps de résurrection, Editions Buchet-Chastel (Paris, 1961), p. 44.

(14) Dans Les Structures Anthropologiques de l’Imaginaire, Editions Bordas (Paris, 1973), p. 189.

(15) Transcription en prose moderne par Jacques Ribard, Editions Honoré Champion (Paris-Genève, 1997), p. 44.

(16) Les Structures Anthropologiques de l’Imaginaire, op. cit., p. 179.

(17) Epître aux Théssaloniciens, 4, 8.

(18) Apocalypse, 1, 16.

(19) Du nom de la localité où il fut mis à jour. Cet objet est conservé au Nationalmuseet de Copenhague mais une réplique existe au Musée des Antiquités Nationales de Saint-Germain-en-Laye (dans la grande salle d’archéologie comparée).

(20) Pour une étude plus détaillée de cette scène, nous ne pouvons que renvoyer à notre ouvrage, déjà mentionné, Chevalerie du Graal et Lumière de Gloire, p. 91 et suivantes.

(21) Cf. Françoise Le Roux et Christian-J. Guyonvarc’h, Les Druides, Editions Ouest France (Rennes, 1986), p. 379.

(22) Equivalent celtique de l’inépuisable corne d’abondance dans la tradition grecque. On notera que le chaudron de Gundestrup contient l’image d’un autre chaudron, divin celui-là.

(23) Ce qui n’est pas sans évoquer l’image de Pallas Athéna, toujours casquée car déesse de l’intelligence armée.

(24) A propos de l’oiseau blasonnant le premier cavalier, on a retrouvé dans un site celtique de Roumanie (à Ciumesti) un casque d’apparat surmonté d’un oiseau métallique aux ailes articulées. Peut-être s’agit-il de la représentation d’un corbeau, animal dédié au dieu Lug. Porté par le second cavalier, le sanglier, très fréquent dans l’art celte, relève d’un symbolisme polaire car associé à la notion de terre originelle et de lumière (l’accentuation des soies dorsale évoque une radiance de la colonne vertébrale) ; sur le sanglier, cf. René Guénon, le chapitre XXIV des Symboles fondamentaux de la Science sacrée, Edition Gallimard (Paris, 1965). Le casque du troisième porte des cornes de cerf, emblème du dieu forestier Cernunnos précisément représenté dans la décoration intérieure (et sans doute aussi extérieure) du chaudron. Enfin, le quatrième cavalier arbore un cimier assez semblable à ceux ombrageant les casques grecs ou italiques. Comme il ne peut s’agir que de crin de cheval, le symbolisme renvoie à ce dernier animal consacré à la déesse cavalière Epona. Il n’est sans doute pas inutile de signaler que le motif végétal isolant l’un de l’autre les deux registres possède trois racines qui jouxtent le chaudron ; on nous précise ainsi que pareille figuration s’identifie avec ce que contient et représente le récipient : la « force vitale » (source d’abondance et de résurrection) souvent figurée par l’Arbre Axe du monde qui, marquant l’invariable milieu de toute chose, joint la terre au ciel. Sans doute s’agit-il d’un tel Arbre qui, ici, est stylisé en une simple ligne végétale ramifiée. Si cet Arbre fait corps avec le chaudron, cela signifie que ceux dont la tête est plongée dedans en ressortiront définitivement porteurs de ce que l’Arbre symbolise. La notion de jonction entre l’humain et le divin est donc indissociable de cette « proto-chevalerie » conçue par la tradition celtique. Dans le récit intitulé La Queste del Saint Graal, il est question de passer de la chevalerie terrestre à la chevalerie « célestielle ».

(25) Editions Berg International (Paris, 1986). Cette silhouette aux bras en V est celle du crucifié. Toutefois, l’iconographie chrétienne présente parfois Jésus non point sur la croix mais sur un une sorte d’Y (comme le montre la mitre de Saint Charles Borromeo, dans le trésor de la cathédrale de Milan) ou carrément sur ce qui ressemble fort à la rune quinzième (ainsi, dans l’église San Andrea à Pistoie, sur la chaire en marbre par Jean de Pise, réalisée en 1301 ; ou encore, dans la cathédrale de Cologne, le Christ dit « de la peste » datant aussi du XIVème siècle). On pourrait également citer, du XIIème siècle et légèrement antérieur à l’œuvre de Chrétien de Troyes, sur le tympan du monastère de Ganagobie, la singularité de l’auréole du Christ : au lieu de comporter une croix, cette auréole est marquée par un tracé évocateur de la rune quinze.

(26) Tous deux portent une main à leur épaule : la senestre à l’épaule droite pour le premier et la dextre à l’épaule gauche pour le second. Ils indiquent ainsi la clavicule — du latin clavicula, « petite clef » – comme pour avertir celui qui les contemple que cette sculpture nécessite des clefs de lecture. Le « meuble » héraldique déployé sur leur écu résume tout un processus alchimique reflétant la transmutation de l’homme mortel en un être immortel. En effet, ce meuble est intitulé « rais d’escarboucle » et, en alchimie, l’escarboucle est synonyme de pierre philosophale, le Grand Œuvre sensé conférer l’immortalité.

(27) 0n a interprété le fait que deux Templiers enfourchent un même cheval comme un symbole de pauvreté de l’Ordre. Cette assertion tient d’autant moins qu’à l’époque où ce sceau était en usage le Temple possédait une fortune considérable.

(28) Graal et Alchimie, Editions Berg International (Paris, 1992).

(29) Il s’agit d’abord d’une bractéate en or trouvée à Pliezhausen, dans le Wurtemberg (Allemagne). Le motif qu’elle porte est reproduit de façon répétitive sur le casque découvert à Sutton Hoo, Suffolk (Angletrre), dans la tombe d’un prince anglo-saxon enterré probablement en 625. Le fait que nous soyons en présence de deux représentations exactement semblables montre toute l’importance de ce motif et tendrait à prouver que les artistes (ou artisans) reproduisaient scrupuleusement certains modèles d’inspiration initiatique.

(30) Le mot fylgja est norrois mais il correspond au gothique fulgja et, dans la terminologie concernant ce qu’il conviendrait de nommer, avec Mircea Eliade, la « physiologie subtile » (Le Yoga, op.cit., p. 81), correspond à l’aspect supérieur du Double. On peut voir au Musée de Berlin une tête d’argile très schématiquement façonnée sur laquelle sont répartis cinq caractères runiques formant approximativement le mot fulgja. Comme on peut le lire sous la reproduction photographique de cet objet dans la Mythologie Générale, Editions Larousse (Paris, 1936), p. 247, « cette statuette représenterait sous un aspect concret, la partie immatérielle d’un être vivant ».

(31) Cf diverses études dans lesquelles nous avons montré que ce nom latinisé, Merlinus, occultait la notion de Tradition primordiale ou, ce qui revient au même, de Pôle ; cf., par exemple, notre article consacré au film de Peter Jackson, Le Seigneur des Anneaux dans le n° 22 de la revue Liber Mirabilis (saison 2001-2002), p. 34.

(32) Entre autres à l’occasion d’un article intitulé Les symboles dans le cortège du Graal, pour la revue Histoire et images médiévales (Février-Mars 2006), p. 39.

(33) Rappelons que Tacite établit un parallèle entre les Dioscures et les Alci que « l’on vénère comme deux frères, comme deux jeunes hommes » ; chapitre XLIII de De Germania, Editions Les Belles Lettres (Paris, 1967), p. 97.

(34) Dans Introduction à la Runologie, Editions Aubier Montaigne (Paris, 1976), p. 137.

(35) Cf son ouvrage Les Runes, Editions du Porte-Glaive (Paris, 1995), p.36.

(36) Il s’agit de la lance du centurion Longin qui perça le flanc du Christ lors de la crucifixion.

(37) Le Conte du Graal, traduit en français moderne par Jacques Ribard, Editions Honoré Champion (Paris, 1997), p. 70.

(38) Mythologie grecque et romaine, Edition Pocket (Paris, 1994), p. 354.

(39) Vers n° 3233 de l’Edition William Roach

(40) N’oublions pas que le symbolisme chrétien avait incorporé la doctrine des quatre Âges symbolisés par des métaux, à la fois par la connaissance du texte d’Hésiode et par le passage du livre de Daniel où, dans le songe de Nabuchodonosor, il est question de la statue dont la tête est d’or, la poitrine d’argent, le ventre et les cuisses d’airain et les mollets de fer.

(41) Dans ses Bucoliques, quatrième églogue, le poète annonce la naissance de l’enfant qui va « bannir le siècle de fer et ramener l’Âge d’Or (…) Cet enfant vivra de la vie des dieux » ; traduction de M. Charpentier de Saint Prest, Editions Garnier frères (Paris). On sait que Chrétien de Troyes avait lu Virgile, comme le montre le vers 9059 où il cite les noms de Lavinie et d’Énée, personnages de l’Énéide.

(42) 21 – 18, Bible du chanoine Crampon.

(43) « Une(s) armes totes dorees. » dit le texte original ? Vers 40

(44) Il est question, dans le Lebor Gabala, de quatre îles au Nord du monde où se trouvait le chaudron de résurrection et siège de l’enseignement druidique ; cf. Françoise Le Roux et Christian-J. Guyonvarc’h, Les Druides, op. cit., p. 305. Cette thématique d’un lieu mystérieux situé « quelque part » dans l’extrême Nord et qui, singulièrement verdoyant (le nom même de Groenland a suscité des interrogations), serait le siège d’une connaissance supra-humaine rejoint l’ultima Thulé des auteurs grecs et latins, de Pythéas et Sénèque à Virgile qui, dans ses Georgiques (1, 30), situe cette contrée « aux extrémités du monde ».

(45) Le Voyage de Saint Brandan par Benedeit, Edition 10/18, bibliothèque médiévale (Paris, 1984).

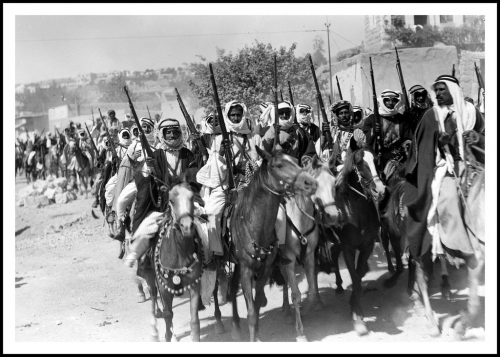

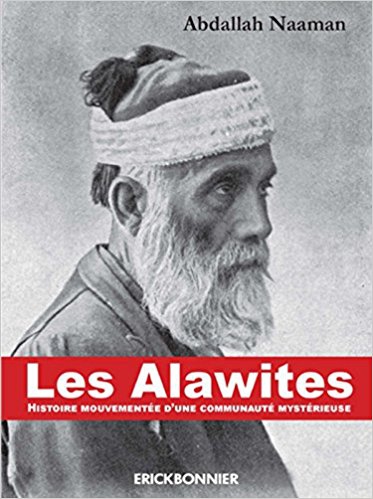

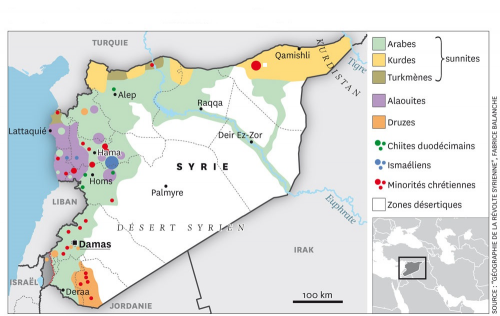

Le mot mentionne ensuite une communauté ethno-religieuse surtout présente en Syrie et au Liban. Abdallah Naaman étudie ce groupe peu connu pour lequel il remplace les lettres o et u par un w : Les Alawites. Histoire mouvementée d’une communauté mystérieuse (Éditions Érick Bonnier, coll. « Encre d’Orient », 359 p., 20 €). L’ouvrage se compose de deux parties inégales. L’une revient longuement sur le déclenchement de la guerre civile syrienne. Démocrate et laïque, l’auteur récuse les supposés rebelles et vrais terroristes islamistes sans pour autant soutenir le gouvernement légitime du président Bachar al-Assad. Très critique envers Israël et l’Arabie Saoudite, il n’hésite pas à qualifier Nicolas Sarkozy de « burlesque », Laurent Fabius de « mouche du coche (p. 200) » et à dénoncer le philosophe botulien Bernard-Henri Lévy qu’il considère comme un « affabulateur (p. 201) » et un « malhonnête homme à la chemise blanche immaculée que d’aucuns traitent d’imposteur intellectuel de la nouvelle philosophie (p. 201) ». Cependant, hors de ces quelques vérités très incorrectes, l’autre partie s’attache à découvrir un peuple mystérieux.

Le mot mentionne ensuite une communauté ethno-religieuse surtout présente en Syrie et au Liban. Abdallah Naaman étudie ce groupe peu connu pour lequel il remplace les lettres o et u par un w : Les Alawites. Histoire mouvementée d’une communauté mystérieuse (Éditions Érick Bonnier, coll. « Encre d’Orient », 359 p., 20 €). L’ouvrage se compose de deux parties inégales. L’une revient longuement sur le déclenchement de la guerre civile syrienne. Démocrate et laïque, l’auteur récuse les supposés rebelles et vrais terroristes islamistes sans pour autant soutenir le gouvernement légitime du président Bachar al-Assad. Très critique envers Israël et l’Arabie Saoudite, il n’hésite pas à qualifier Nicolas Sarkozy de « burlesque », Laurent Fabius de « mouche du coche (p. 200) » et à dénoncer le philosophe botulien Bernard-Henri Lévy qu’il considère comme un « affabulateur (p. 201) » et un « malhonnête homme à la chemise blanche immaculée que d’aucuns traitent d’imposteur intellectuel de la nouvelle philosophie (p. 201) ». Cependant, hors de ces quelques vérités très incorrectes, l’autre partie s’attache à découvrir un peuple mystérieux.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

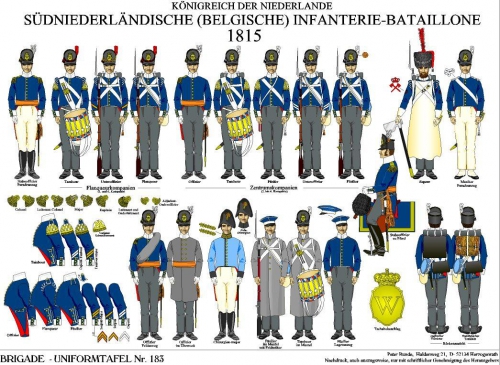

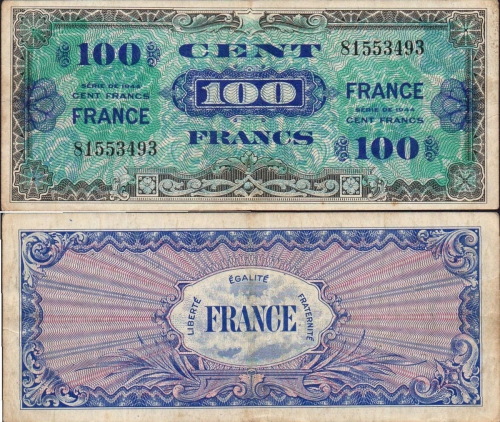

This tension between the two Bonaparte brothers was exacerbated by the effort of the Emperor Napoleon to defeat Britain by means of economic strangulation. He instituted the Continental System which forbid France and all countries controlled by or allied with France from trading with the British which, as it turned out, proved more ruinous for the continent than it did for Britain and particularly for The Netherlands which had a heavily trade-based economy. Needless to say, smuggling soon reached epidemic proportions because of this and Napoleon was so desperate to stamp it out that in 1810 he simply annexed the Kingdom of Holland and it was absorbed into the French Empire. The former King Ludwig I, by then none too popular with his brother, fled into exile in the Austrian Empire and remained there for the rest of his life. So it was that, until 1813, the Dutch, willingly or not, mostly fought alongside the French under Napoleon. For some, this did not seem all that unnatural given the long history of Anglo-Dutch rivalry and warfare.

This tension between the two Bonaparte brothers was exacerbated by the effort of the Emperor Napoleon to defeat Britain by means of economic strangulation. He instituted the Continental System which forbid France and all countries controlled by or allied with France from trading with the British which, as it turned out, proved more ruinous for the continent than it did for Britain and particularly for The Netherlands which had a heavily trade-based economy. Needless to say, smuggling soon reached epidemic proportions because of this and Napoleon was so desperate to stamp it out that in 1810 he simply annexed the Kingdom of Holland and it was absorbed into the French Empire. The former King Ludwig I, by then none too popular with his brother, fled into exile in the Austrian Empire and remained there for the rest of his life. So it was that, until 1813, the Dutch, willingly or not, mostly fought alongside the French under Napoleon. For some, this did not seem all that unnatural given the long history of Anglo-Dutch rivalry and warfare.