"Polemos", par Enrico Garff

Conversation avec Julien Freund

par Pierre Bérard

Ex: http://asymetria-anticariat.blogspot.com

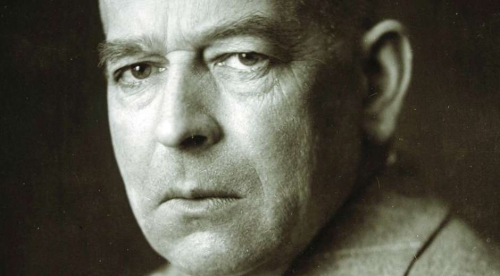

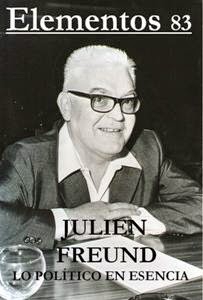

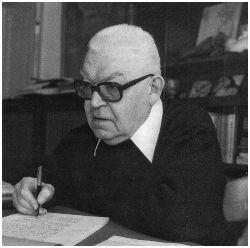

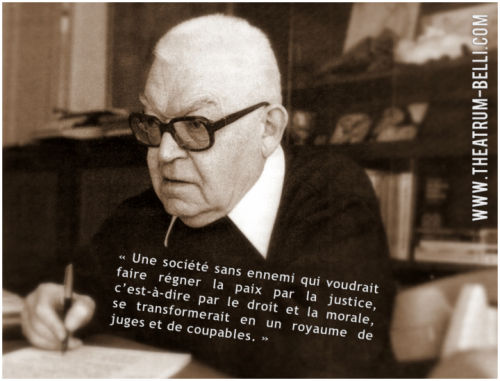

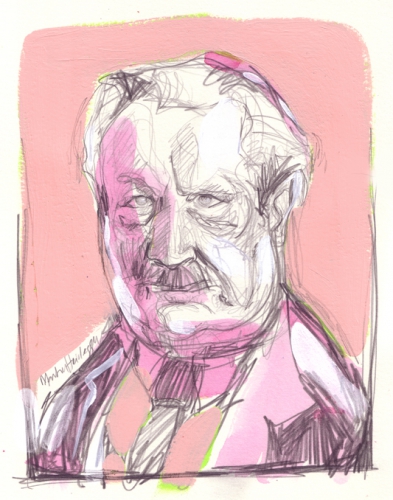

Julien Freund est mort en septembre 1993. De la fin des années 70 jusqu'à son décès, je l'ai rencontré à maintes reprises tant à Strasbourg que chez lui à Villé et dans ces villes d'Europe où nous réunissaient colloques et conférences. Des heures durant j'ai frotté à sa patience et à sa perspicacité les grands thèmes de la Nouvelle Droite. Il les accueillait souvent avec une complicité rieuse, parfois avec scepticisme, toujours avec la franche indépendance d'esprit qui a marqué toute son existence. Les lignes qui suivent mettent en scène des conversations tenues à la fin des années quatre-vingt. Des notes prises alors sur le vif et des souvenirs demeurés fort intenses m'ont permis de reconstituer par bribe certains de ces moments. Bien entendu, il ne s'agit pas d'utiliser ici le biais de la fiction posthume pour prêter à Julien Freund des propos que les calomniateurs dont on connaît l'acharnement pourraient instrumenter contre la mémoire d'un grand maître. C'est pourquoi j'entends assumer l'entière responsabilité de ce dialogue. Lors de ces entrevues, on le devine, l'ami absent mais souvent évoqué était Alain de Benoist. Ce texte lui est dédié.

Julien Freund est mort en septembre 1993. De la fin des années 70 jusqu'à son décès, je l'ai rencontré à maintes reprises tant à Strasbourg que chez lui à Villé et dans ces villes d'Europe où nous réunissaient colloques et conférences. Des heures durant j'ai frotté à sa patience et à sa perspicacité les grands thèmes de la Nouvelle Droite. Il les accueillait souvent avec une complicité rieuse, parfois avec scepticisme, toujours avec la franche indépendance d'esprit qui a marqué toute son existence. Les lignes qui suivent mettent en scène des conversations tenues à la fin des années quatre-vingt. Des notes prises alors sur le vif et des souvenirs demeurés fort intenses m'ont permis de reconstituer par bribe certains de ces moments. Bien entendu, il ne s'agit pas d'utiliser ici le biais de la fiction posthume pour prêter à Julien Freund des propos que les calomniateurs dont on connaît l'acharnement pourraient instrumenter contre la mémoire d'un grand maître. C'est pourquoi j'entends assumer l'entière responsabilité de ce dialogue. Lors de ces entrevues, on le devine, l'ami absent mais souvent évoqué était Alain de Benoist. Ce texte lui est dédié.

J.F. - Vous êtes à l'heure, c'est bien !

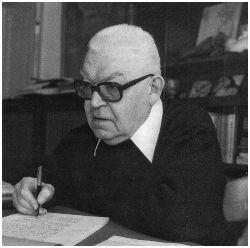

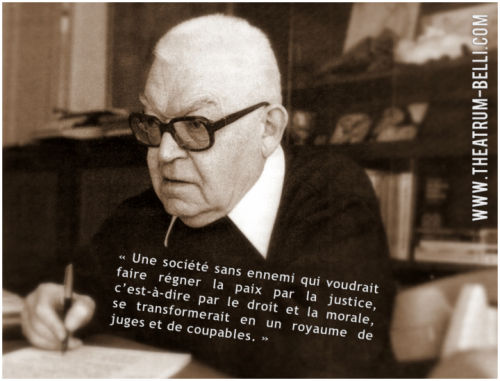

Visage plein, barré d'un large sourire, Julien Freund se tient sur le pas de sa porte.

- J'ai réservé à l'endroit habituel, poursuit-il.

Il enfile un anorak, ajuste un béret sur une brosse impeccable et se saisit de sa canne. Regard amusé sur la gîte inquiétante de la voiture que je viens de garer cahin caha sur l'accotement boueux qui jouxte le chemin de terre. Nous descendons en direction du bourg de Villé.

J.F. - Comment va votre ami Alain de Benoist ?

Puis, tout de go, sans même attendre la réponse :

- Comme vous, je suis frappé par l'aboulie de l'Europe. Regardez, les élèves alsaciens choisissent de moins en moins l'allemand à l'école ! Plus l'Europe se construit par une sorte d'engrenage et moins les Européens s'intéressent les uns aux autres. Dans tous les pays de la Communauté, l'enseignement des autres langues européennes régresse au bénéfice de l'anglais. Par dévolution, elle hérite des patries sans réussir à se doter de leurs qualités. Elle fonctionne comme une procédure de dépolitisation. Elle ne veut pas s'assigner de limites géographiques. Elle ne veut pas être un territoire. Un territoire, voyez-vous, ce n'est pas un espace neutre, susceptible d'une dilatation à l'infini. Le territoire est à l'opposé de l'espace abstrait, c'est un site conditionné, habité par une culture. La nouvelle frontière utopique de l'Europe, c'est l'impolitique des droits de l'homme. C'est une notion hyperbolique mais vague... on ne meurt pas pour une notion aussi floue. Cet espace là n'a pas de qualité, pas d'épaisseur, pas de densité. Il ne peut pas susciter l'adhésion. Seul le territoire peut nourrir des liens d'affection, d'attachement. Du fait du particularisme qui lui est inhérent, l'identité collective exige des frontières. Elle entre en crise quand toute démarcation s'efface. Etre Européen, c'est être dépositaire d'un patrimoine spécifique et s'en reconnaître comptable.

Je croyais ardemment à la construction européenne, mais je suis devenu sceptique dans la mesure où cette Europe là risque bien de n'être qu'un vecteur de la dénationalisation générale, la simple conjugaison de nos impuissances. L'Europe semble vouloir expier son ancienne volonté de puissance. Nous sommes au balcon de l'histoire, et nous faisons étalage de nos bons sentiments.

Il suffit de considérer la complaisance avec laquelle nous nous laissons culpabiliser. Comment s'appelle ce monsieur qui a sorti un livre là-dessus ?

P.B. - Pascal Bruckner... " Le sanglot de l'homme blanc "

J.F. - L'avez-vous lu ?

P.B. - Bien sûr... mais si il fustige en effet la mauvaise conscience européenne, c'est au nom des valeurs universelles de l'Occident dont se réclament aussi les Père-Fouettards qui charcutent notre passé afin de le maudire. Les uns et les autres raisonnent à partir des mêmes présupposés. Bruckner est le héraut d'un universalisme fier et conquérant qui, dans le sillage du néo-libéralisme entend imposer le magistère moral de l'Occident à l'ensemble de l'oekoumène. Ce qu'il reproche aux larmoyants, c'est de n'instrumenter les mêmes valeurs que pour nous diminuer. Ce que disent en revanche les détracteurs de l'Europe, c'est que jamais nous ne fûmes dignes de notre mission civilisatrice. A ce gémissement, Bruckner rétorque qu'il nous faut être forts dans le seul but de sermonner le monde et de lui apprendre les bonnes manières...

J.F. - C'est aux antipodes de ce qu'écrit Alain de Benoist dans son livre sur le tiers monde.

P.B. - En effet ; lui a d'autres paradigmes. Il se tient plutôt dans le camp de l'anthropologie culturelle. Du côté du relativisme.

J.F. - Il n'a pas tort d'un point de vue ontologique, car il faut se débarrasser des excès de l'ethnocentrisme, surtout quand il entretient l'exorbitante prétention de se prétendre universel. Mais politiquement il fait fausse route.

P.B. - Et pourquoi ça ?

J.F. - Relisez mon Essence du politique. Si le tiers monde nous désigne comme ennemi ; par exemple en tant qu'ancienne puissance coloniale responsable de tous ses échecs ; alors nous ne pouvons pas nous dérober sous peine de capitulation. L'affrontement politique n'est pas suspendu aux choix des valeurs, mon cher ami...

Julien Freund fait mine de se renfrogner, puis il éclate de rire...Il fouille le menu avec gourmandise.

J.F. - Qu'est-ce que nous avions pris la dernière fois ?

P.B. - Un baeckeofe.

J.F. - je propose donc un jambonneau et comme il n'y a pas de rouge d'Ottrott, nous allons nous rabattre sur un pinot noir...Sur cet universalisme fallacieux qui règne depuis la dernière guerre mondiale, Schmitt s'est exprimé dans les années vingt. Il écrit dans sa Notion de Politique que " le concept d'humanité est un instrument idéologique particulièrement utile aux expansions impérialistes " et que " sous sa forme éthique et humanitaire, il est un véhicule spécifique de l'impérialisme économique ". Bien évidemment les Américains traduisent leurs intérêts nationaux en langage internationaliste, exactement comme le font les Soviétiques. Mais vous le savez bien, si j'accepte de comparer ces deux puissances, ce n'est pas pour les confondre. Cependant, si le despotisme communiste venait à disparaître comme pourraient le laisser prévoir tous ces craquements à l'Est, l'Amérique pourrait être tentée par une hégémonie sans retenue.

En réponse à ces immenses défis, je suis frappé par le caractère routinier du débat européen. L'Europe se construit d'une manière fonctionnaliste, par une suite d'enchaînements automatiques. Son fétichisme institutionnel permet de dissimuler notre maladie qui est l'absence d'objectifs affichés. Nous sommes par exemple impuissants à nous situer par rapport au monde. Etrange narcissisme ; on se congratule d'exister, mais on ne sait ni se définir, ni se circonscrire. L'Europe est-elle reliée à un héritage spécifique ou bien se conçoit-elle comme une pure idéalité universelle, un marchepied vers l'Etat mondial ? L'énigme demeure avec un penchant de plus en plus affirmé pour la seconde solution qui équivaudrait à une dissolution. Ce processus se nourrit par ailleurs, c'est transparent chez les Allemands, d'une propension à fuir le passé national et se racheter dans un sujet politique plus digne d'estime, une politie immaculée, sans contact avec les souillures de l'histoire. Cette quête de l'innocence, cet idéalisme pénitentiel qui caractérisent notre époque se renforcent au rythme que lui imposent les progrès de cette mémoire négative toute chargée des fautes du passé national. On veut lustrer une Europe nouvelle par les vertus de l'amnésie. Par le baptême du droit on veut faire un nouveau sujet. Mais ce sujet off-shore n'est ni historique, ni politique. Autant dire qu'il n'est rien d'autre qu'une dangereuse illusion. En soldant son passé, l'Europe s'adosse bien davantage à des négations qu'à des fondations. Conçue sur cette base, l'Europe ne peut avoir ni objectif, ni ambition et surtout elle ne peut plus rallier que des consentements velléitaires. Le nouvel Européen qu'on nous fabrique est une baudruche aux semelles de vent. Les identités fluides, éphémères qu'analyse Michel Maffesoli ne peuvent en aucun cas tenir le rôle des identités héritées. Elles n'agrègent que de manière ponctuelle et transitoire, en fonction de modes passagères. Oui, ce ne sont que des agrégats instables stimulés par le discours publicitaire. L'orgiasme n'est pas une réponse au retrait du politique, car il exclut la présence de l'ennemi. Quand il se manifeste, l'ennemi, lui, ne s'adonne pas au ludisme dionysiaque. Si le politique baisse la garde, il y aura toujours un ennemi pour troubler notre sommeil et déranger nos rêves. Il n'y a qu'un pas de la fête à la défaite. Ces tribus là ne sont pas un défi à l'individualisme, elles en sont l'accomplissement chamarré...

En réponse à ces immenses défis, je suis frappé par le caractère routinier du débat européen. L'Europe se construit d'une manière fonctionnaliste, par une suite d'enchaînements automatiques. Son fétichisme institutionnel permet de dissimuler notre maladie qui est l'absence d'objectifs affichés. Nous sommes par exemple impuissants à nous situer par rapport au monde. Etrange narcissisme ; on se congratule d'exister, mais on ne sait ni se définir, ni se circonscrire. L'Europe est-elle reliée à un héritage spécifique ou bien se conçoit-elle comme une pure idéalité universelle, un marchepied vers l'Etat mondial ? L'énigme demeure avec un penchant de plus en plus affirmé pour la seconde solution qui équivaudrait à une dissolution. Ce processus se nourrit par ailleurs, c'est transparent chez les Allemands, d'une propension à fuir le passé national et se racheter dans un sujet politique plus digne d'estime, une politie immaculée, sans contact avec les souillures de l'histoire. Cette quête de l'innocence, cet idéalisme pénitentiel qui caractérisent notre époque se renforcent au rythme que lui imposent les progrès de cette mémoire négative toute chargée des fautes du passé national. On veut lustrer une Europe nouvelle par les vertus de l'amnésie. Par le baptême du droit on veut faire un nouveau sujet. Mais ce sujet off-shore n'est ni historique, ni politique. Autant dire qu'il n'est rien d'autre qu'une dangereuse illusion. En soldant son passé, l'Europe s'adosse bien davantage à des négations qu'à des fondations. Conçue sur cette base, l'Europe ne peut avoir ni objectif, ni ambition et surtout elle ne peut plus rallier que des consentements velléitaires. Le nouvel Européen qu'on nous fabrique est une baudruche aux semelles de vent. Les identités fluides, éphémères qu'analyse Michel Maffesoli ne peuvent en aucun cas tenir le rôle des identités héritées. Elles n'agrègent que de manière ponctuelle et transitoire, en fonction de modes passagères. Oui, ce ne sont que des agrégats instables stimulés par le discours publicitaire. L'orgiasme n'est pas une réponse au retrait du politique, car il exclut la présence de l'ennemi. Quand il se manifeste, l'ennemi, lui, ne s'adonne pas au ludisme dionysiaque. Si le politique baisse la garde, il y aura toujours un ennemi pour troubler notre sommeil et déranger nos rêves. Il n'y a qu'un pas de la fête à la défaite. Ces tribus là ne sont pas un défi à l'individualisme, elles en sont l'accomplissement chamarré...

Et puis, c'est une Europe de la sempiternelle discussion ... et toujours sur des bases économiques et juridiques, comme si l'économie et le droit pouvaient être fondateurs. Vous savez l'importance que j'accorde à la décision, or l'Europe est dirigée par une classe discutante qui sacrifie le destin à la procédure dans un interminable bavardage qui ne parvient guère à surmonter de légitimes différents. Ce refus de la décision est lié au mal qui frappe nos élites ; elles ne croient plus à la grandeur de notre continent ; elles sont gâtées jusqu'à la moelle par la culpabilité dont elles transmettent l'agent létal à l'ensemble des Européens. D'où cette dérive moralisatrice qui transforme l'Europe en tribunal, mais en tribunal impuissant.

P.B. - Il n'est pas toujours impuissant à l'égard des autochtones...

J.F. - Ca, c'est une autre affaire... Impuissant, car nous prétendons régir la marche du monde vers l'équité, mais nous refusons d'armer le bras de cette prétendue justice. La culpabilité névrotique inhibe l'action.Le problème, c'est que l'Europe est construite par des libéraux et par des socio-démocrates, c'est à dire par des gens qui croient dans l'économie comme instance déterminante. C'est pourquoi la neutralisation du politique est pour ainsi dire inscrite dans son code génétique.

P.B. - L'Europe n'est qu'un tigre de papier.

J.F. - Elle ne fait même pas semblant d'être un tigre ! Depuis plus de quarante ans, elle s'en remet aux Américains pour ce qui est de sa protection. Elle a pris le pli de la vassalité, l'habitude d'une servitude confortable. C'est ce que dévoilent d'ailleurs les choix budgétaires de tous ses gouvernements quelle qu'en soit la couleur : la portion congrue pour la défense, une part grandissante pour les dépenses sociales. En réalité, L'Europe ne peut se construire que sur un enjeu ultime... la question de la vie et de la mort. Seul le militaire est fédérateur, car dans l'extrême danger il est la seule réponse possible. Or ce danger viendra, car l'Europe vieillissante riche et apathique ne manquera pas d'attiser des convoitises. Alors viendra le moment de la décision, celui de la reconnaissance de l'ennemi... Ce sera le sursaut ou la mort. Voilà ce que je pense. M'exprimer de cette manière ne me vaut pas que des amis...

P.B. - Maints ennemis, beaucoup d'honneur...

Julien Freund n'est pas en odeur de sainteté. Des clercs de seconde zone ourdissent à son encontre une campagne de sous-entendus. Ces calomnies reviennent souvent, dans nos ultimes conversations. Pourquoi un tel acharnement ?

J.F. - J'ai cultivé l'indépendance d'esprit, ce qui fait de moi un suspect dans un milieu universitaire de plus en plus contaminé par le conformisme moralisant. Et puis, avec le soutien de Raymond Aron, j'ai introduit en France l'oeuvre de Carl Schmitt.

P.B. - Est-ce que cela suffit à vous frapper d'un anathème sournois ?

J.F. - Et comment ! Schmitt, c'est le démenti des niaiseries contemporaines en matière de philosophie politique. J'ai intronisé le loup ; c'est la panique dans la bergerie de Panurge. La gauche morale est anémique. Elle est déstabilisée par un tel monument. Vous comprenez... C'est une pensée très construite et qui rassemble les plus grandes oeuvres du canon occidental. Ils ne peuvent pas s'en débarrasser d'une pichenette...

P.B. - Alors comme souvent, quand l'omerta n'est plus tenable, ils déblatèrent.

P.B. - Alors comme souvent, quand l'omerta n'est plus tenable, ils déblatèrent.

J.F. - En France, oui, c'est l'invective. Pas en Italie, pas en Espagne. En France, on refuse d'être déniaisé ; on préfère la calomnie venimeuse et les coups de clairon antifascistes. " Schmitt - nazi " ! C'est toujours la même rengaine. Auparavant, les intellectuels libéraux discutaient avec Schmitt. Aron bien sûr, mais regardez Léo Strauss aux Etats-Unis ou Jacob Taubes. Même Walter Benjamin a reconnu sa dette. Ceux d'aujourd'hui subissent l'ascendant de leurs adversaires de gauche et tentent par tous les moyens de s'innocenter. Ils sont les victimes consentantes de la stratégie du soupçon... par lâcheté. Quant à la gauche... depuis que Mitterrand a renoncé à la rupture avec le capitalisme, elle s'est réfugié dans la politique morale ; elle ne pense plus qu'en terme d'antifascisme. La lutte des " places " a remplacé la lutte des classes. " Schmitt-nazi " ; alors on susurre que Freund, c'est du pareil au même.

P.B. - D'autant que vous avez aggravé votre cas...

J.F. - Oui, en vous fréquentant ! J'ai dit publiquement l'intérêt que je portais au travail d'Alain de Benoist. C'est le coup de grâce. Après ça, il n'y a plus de rémission. Je mérite la proscription...

Julien Freund déchaîne un rire espiègle et commande une nouvelle bouteille de pinot noir.

... Ici, certains n'ont pas digéré le débat que j'arbitrais et qui vous avait opposé à eux, Faye et vous, au palais universitaire. Ce fut leur déconfiture... Une Berezina dont ils me tiennent toujours rigueur. Vous comprenez leur exaspération. Ils sont habitués à ressasser leurs mantras sans qu'aucun adversaire à la hauteur ne vienne déranger la litanie et puis là, face au diable, ce qui ne devrait jamais arriver... ce face à face c'est l'interdit majeur. Là donc ils s'effondrent. Et leurs propres étudiants vous applaudissent réduisant leur claque au silence. C'est que... ils se sont enlisés dans la paresse argumentative ; ils ronronnent sans que le moindre désaveu un peu farouche leur soit opposé. Quant aux grands professeurs qui pourraient les contrer, ils existent toujours, mais ils sont tétanisés. La plupart se sont réfugiés dans la pure érudition et songent d'abord à ménager leur carrière... Ils ont déserté l'espace public.Tenez, savez-vous qu'il est question de traduire en espagnol l'ouvrage collectif que j'avais dirigé avec André Béjin sur le racisme ?

P.B. - Le racisme et l'antiracisme... Il y a quelques années le racisme seul suscitait interrogation et condamnation. L'antiracisme allait de soi ; c'était la réponse légitime à la vilenie.

J.F. - Oui, il devient urgent non seulement d'interroger l'antiracisme, mais de le faire parler. La révérence pieuse qui entoure ce prêchi-prêcha est devenue insupportable !

P.B. - Il y a une hésitation de la doxa antiraciste. L'Autre doit-il être envisagé comme le semblable ou comme le différent ?

J.F. - Mais, Bérard, ce n'est pas une hésitation, mais une confusion ! La vulgate antiraciste, c'est un alliage d'insuffisance théorique et d'arrogance rhétorique. Et en prime, l'alibi d'une morale incontestable.

P.B. - Soit. La substance de l'antiracisme est mouvante parce qu'elle est surdéterminée par des manigances tactiques, tantôt assimilationniste sur le mode républicain, tantôt différentialiste dans une perspective qu'on pourrait dire... américaine...

J.F. - Ce sont ces errements qui le rendent difficile à saisir. Je ne suis pas persuadé qu'ils soient seulement tactiques. D'ailleurs les deux discours fonctionnent côte à côte dans un agrégat extravagant de paralogismes. Mais de leur point de vue ça n'a pas d'importance. Ce qui compte, c'est la posture morale. La pureté des intentions est censée cautionner l'échafaudage intellectuel, comme dans le pacifisme. Vous connaissez mes travaux là-dessus.

P.B. - La confusion est renforcée par la polysémie du vocabulaire.

J.F. - Bien sûr. Qu'est-ce qu'une race ? Est-ce une notion scientifique ? Est-ce un pur flatus vocis forgé par l'idéologie ? L'aspect plurivoque de toutes ces choses qu'on ne veut surtout pas définir de façon rigoureuse donne licence aux discours des charlatans. Il y a un dévergondage propre au dégoisement antiraciste. Il manie des idées confuses pour mieux pêcher en eau trouble et intoxiquer les esprits. D'autant que ce galimatias est secondé par la presse qui maintient une pression constante sur l'opinion en interprétant à sa manière le moindre fait divers. Gare aux incartades... Je ne parviens plus à lire Le Monde...

P.B. - J'en reviens quand même à ce que je disais. Il y a donc l'obligation morale d'aimer l'Autre et de l'admettre dans la communauté politique comme un semblable. Par ailleurs, enfin adoubé comme alter ego, il conviendra sans doute de le pourvoir de privilèges compensatoires justifiés par les souffrances que la xénophobie et le racisme lui feraient endurer. C'est la querelle de la discrimination positive qui commence à poindre en plein pathos républicain...

J.F. - L'américanisation comme dit Alain de Benoist.

P.B. - Et, en même temps qu'il se voit invité à entrer dans la maison commune...

J.F. - C'est un spectre, un épouvantail que la gauche agite pour renforcer le vote protestataire.

P.B. - ...Sa promotion de commensal particulièrement choyé à la table citoyenne s'accompagne de la fabrication d'un Autre absolu qu'il est recommandé d'exclure, voire de haïr. Cet Autre brutalement retranché du genre humain, c'est, bien entendu le raciste, le xénophobe... ou, du moins, celui auquel il est avantageux de coller cette étiquette. Ainsi se vérifie cette constante sociologique qui exige que le Nous se construise sur l'exclusion d'un Autre. Et, le paradoxe, c'est que ceux qui font profession de pourfendre l'exclusion sont les premiers à illustrer la permanence de ce principe !

J.F. - Ah... Ce n'est pas un paradoxe, mais comme vous le dites, une vérification, une vérification ironique...

Julien Freund s'esclaffe, longuement, puis se racle la gorge avant de poursuivre.

- ...Ceux qui sont visés, ce sont évidemment les gens d'extrême droite dans la mesure où ils entendent s'affirmer comme des compétiteurs dans le jeu démocratique... mais il se pourrait qu'à l'avenir des strates entières du petit peuple autochtone soient pour ainsi dire la proie de cette exclusion rageuse. En attribuant le racisme aux seuls Européens, l'antiracisme donne de plus en plus l'impression de protéger unilatéralement une partie de la population contre l'autre. Or, en abdiquant le révolutionnarisme lyrique au profit du capitalisme libéral, Mitterrand sacrifie cette clientèle de petites gens bercée jusqu'ici par le discours égalitariste. Vous comprenez, ils ont été habitués à une vision irénique de l'avenir. Et justement, ce sont eux les plus concernés dans leur vie quotidienne, les plus exposés à la présence étrangère. On sait, depuis Aristote, que l'étranger a toujours été un élément conflictuel dans toutes les sociétés. L'harmonie dans une société... disons " multiraciale " est, plus que dans toute autre, une vue de l'esprit. Or, ces gens dont nous parlons, ceux du bistrot, ici, ceux que je rencontre tous les jours à Villé, ils ne participent pas de la civilité bourgeoise. Ils ne subliment pas leurs affects. Leurs réactions sont plus spontanées, leur jactance moins étudiée. Affranchis des règles de la bienséance hypocrite, ils seront les premières victimes des censeurs de cet antiracisme frelaté qui rêve de placer la société sous surveillance. Traquenards, chausse-trapes, procédés de basse police, délations... ce sont ces malheureux qui seront bientôt les victimes de ce climat d'intolérance. L'empire du Bien est un empire policier ou l'on traque le faux-pas, le lapsus, le non-dit et même l'humour...

P.B. - Ils apprendront à se taire, à dissimuler...

J.F. - Ah, mon cher, je suis fils d'ouvrier et je vis dans un village... Ils ne se tairont pas. Il se peut qu'à force on fasse de ces braves gens des bêtes fauves... C'est ma crainte, je l'avoue... D'autant que les soi-disantes autorités morales cherchent à expier notre passé colonial en accoutrant l'immigré africain de probité candide et de lin blanc...

P.B. - C'est la version post-moderne du bon sauvage... que la méchanceté de notre passé doterait d'une créance inépuisable.

J.F. - Ah oui, cette histoire de la dette... c'est un thème sartrien. Mais c'est d'abord une victime qui doit pouvoir bénéficier de certaines immunités. En effet. De pareils privilèges, même symboliques - mais dans une société matérialiste les privilèges ne se contentent pas de demeurer symboliques - ne peuvent que renforcer les antagonismes et puis, surtout, comprenez bien ça, cela heurte l'évangile égalitaire dont les Français ont la tête farcie. En jouant simultanément l'antiracisme et Le Pen contre la droite, Mitterrand va provoquer la sécession de la plèbe. Cela paraît habile... Mitterrand le Florentin et que sais-je encore... mais c'est impolitique. Car, le politique doit toujours envisager le pire pour tenter de le prévenir. J'insiste : si l'étranger est reconnu comme un élément de désorganisation du consensus, il éveille un sentiment d'hostilité et de rejet. Un brassage de population qui juxtapose des origines aussi hétérogènes ne peut que susciter des turbulences qu'il sera difficile de maîtriser.

P.B. - Les rédempteurs de l'humanité sont indécrottables ?

J.F. - Les sentinelles de l'antifascisme sont la maladie de l'Europe décadente. Ils me font penser à cette phrase de Rousseau persiflant les cosmopolites, ces amoureux du genre humain qui ignorent ou détestent leurs voisins de palier. La passion trépidante de l'humanité et le mépris des gens sont le terreau des persécutions à venir. Votre ami Alain de Benoist a commencé d'écrire de bonnes choses là-dessus. Dites-le-lui, il faut aller dans ce sens : la contrition pathologique de nos élites brouille ce qui fut la clé du génie européen ; cette capacité à se mettre toujours en question, à décentrer le jugement. Ceux qui nous fabriquent une mémoire d'oppresseurs sont en fait des narcissiques. Ils n'ont qu'un souci : fortifier leur image de pénitents sublimes et de justiciers infaillibles en badigeonnant l'histoire de l'Europe aux couleurs de l'abjection. Regardez ce qu'écrit Bernard-Henri Lévy sur Emmanuel Mounier... C'est un analphabète malfaisant. En 1942, j'étais avec Mounier à Lyon... en prison ! En épousant l'universel, ils s'exhaussent du lot commun ; ils se constituent en aristocratie du Bien... L'universel devient la nouvelle légitimité de l'oligarchie !

P.B. - C'est Nietzsche qui écrit dans La volonté de puissance que l'Europe malade trouve un soulagement dans la calomnie. Mais il se pourrait bien que le masochisme européen ne soit qu'une ruse de l'orgueil occidental. Blâmer sa propre histoire, fustiger son identité, c'est encore affirmer sa supériorité dans le Bien. Jadis l'occidental assurait sa superbe au nom de son dieu ou au nom du progrès. Aujourd'hui il veut faire honte aux autres de leur fermeture, de leur intégrisme, de leur enracinement coupable et il exhibe sa contrition insolente comme preuve de sa bonne foi. Ce ne serait pas seulement la fatigue d'être soi que trahirait ce nihilisme contempteur mais plus certainement la volonté de demeurer le précepteur de l'humanité en payant d'abord de sa personne. Demeurer toujours exemplaire, s'affirmer comme l'unique producteur des normes, tel est son atavisme. Cette mélodie du métissage qu'il entonne incessamment, ce ne serait pas tant une complainte exténuée qu'un péan héroïque. La preuve ultime de sa supériorité quand, en effet, partout ailleurs, les autres érigent des barrières et renforcent les clôtures. L'occidental, lui, s'ouvre, se mélange, s'hybride dans l'euphorie et en tire l'argument de son règne sur ceux qui restent rivés à l'idolâtrie des origines. Ce ne serait ni par abnégation, ni même par résignation qu'il précipiterait sa propre déchéance mais pour se confondre enfin intégralement avec ce concept d'humanité qui a toujours été le motif privilégié de sa domination... Il y a beaucoup de cabotinage dans cet altruisme dévergondé et dominateur et c'est pourquoi le monde du spectacle y tient le premier rôle...

P.B. - C'est Nietzsche qui écrit dans La volonté de puissance que l'Europe malade trouve un soulagement dans la calomnie. Mais il se pourrait bien que le masochisme européen ne soit qu'une ruse de l'orgueil occidental. Blâmer sa propre histoire, fustiger son identité, c'est encore affirmer sa supériorité dans le Bien. Jadis l'occidental assurait sa superbe au nom de son dieu ou au nom du progrès. Aujourd'hui il veut faire honte aux autres de leur fermeture, de leur intégrisme, de leur enracinement coupable et il exhibe sa contrition insolente comme preuve de sa bonne foi. Ce ne serait pas seulement la fatigue d'être soi que trahirait ce nihilisme contempteur mais plus certainement la volonté de demeurer le précepteur de l'humanité en payant d'abord de sa personne. Demeurer toujours exemplaire, s'affirmer comme l'unique producteur des normes, tel est son atavisme. Cette mélodie du métissage qu'il entonne incessamment, ce ne serait pas tant une complainte exténuée qu'un péan héroïque. La preuve ultime de sa supériorité quand, en effet, partout ailleurs, les autres érigent des barrières et renforcent les clôtures. L'occidental, lui, s'ouvre, se mélange, s'hybride dans l'euphorie et en tire l'argument de son règne sur ceux qui restent rivés à l'idolâtrie des origines. Ce ne serait ni par abnégation, ni même par résignation qu'il précipiterait sa propre déchéance mais pour se confondre enfin intégralement avec ce concept d'humanité qui a toujours été le motif privilégié de sa domination... Il y a beaucoup de cabotinage dans cet altruisme dévergondé et dominateur et c'est pourquoi le monde du spectacle y tient le premier rôle...

J.F. - Je ne crois pas aux facultés démonstratives de la preuve par la mort, quant aux baladins de l'humanitarisme, ces artistes dont vous parlez, mués en prédicateurs citoyens, ils me rappellent un autre aphorisme de Nietzsche qui écrivait dans Le Crépuscule des idoles que si l'on pense que la culture a une utilité, on confondra rapidement ce qui est utile avec la culture. Nous y sommes. Les histrions sont devenus les hussards noirs des temps de détresse...

P.B. - Il y a un autre paradoxe. Au-delà de leurs périphrases lénifiantes pour nier ou euphémiser les ruptures qui travaillent le corps social, les ligues de vertu semblent hypnotisées par l'ethnique et le racial, même si c'est pour le conjurer ; et ils le déversent à grands tombereaux sur une France plutôt placide qui se voit pour ainsi dire sommée de penser les rapports humains dans les catégories que l'antiracisme se donne officiellement pour mission d'abolir...

J.F. - Des écervelés... des têtes de linotte...

P.B. - Diriez-vous aussi qu'ils sont les fourriers d'une racisation démesurée des rapports sociaux ?

J.F. - Moi, je suis du côté de Barrès. Je ne suis pas l'enfant du " pluriculturel " dont on nous abreuve. Je suis né dans une tradition, sur un territoire, dans un groupe déterminé. C'est par ces liens traditionnels que j'accède à la condition humaine. Décrire cela comme une prison, c'est assigner des milliards d'humains à la condition de bagnards. Ceci étant dit... C'est comme ça que cela se passe aux Etats-Unis, non ? Là-bas il y a une congruence du social et du racial, une substantialisation des catégories sociales qui tend à enfermer certains groupes dans un déterminisme sans espoir.

P.B. - Bizarrement, cette thématique trahit chez les antiracistes de profession une sorte de refoulé...

J.F. - Bérard, ne faites pas de psychanalyse à deux sous... Mais c'est vrai qu'ils abusent d'un langage saturé de référents raciaux. Faire l'apologie du métissage, c'est comme honorer la race pure. C'est ramener l'axiologie à la pâte biologique avec, dans les deux cas, le même fantasme prométhéen, celui des ingénieurs du vivant, des biotechniciens.

P.B. - Cela me fait penser aux manuels de confession de la contre-réforme catholique. Ils sont gorgés de descriptions pornographiques. Bien sûr, là aussi c'était pour le bon motif. Mais certains travaux récents montrent que c'est par le biais du confessionnal que les pratiques anticonceptionnelles se seraient répandues dans les campagnes... l'onanisme comme effet pervers de l'interrogatoire ecclésiastique. Le sexe et la race, deux figures de l'obscénité ; tout le monde y pense, personne n'en parle...

J.F. - Ah ça, c'est du Maffesoli !

Julien Freund s'enferme dans une méditation silencieuse qu'il brise après quelques instants d'une phrase dont il hache chaque syllabe avec une componction moqueuse.

J.F. - Je - vais - prendre - un - munster !

P.B. - Je m'exprime plus clairement. Si il y a retour du refoulé, y compris sur le mode d'une dénégation rageuse, cela ne va-t-il pas lever des inhibitions chez ces gens dont vous parliez tout à l'heure ? Et si c'est le cas, installer du même coup nos censeurs dans un rôle rentable de procureurs débordés. L'hétérotélie selon Monnerot...

J.F. - Disons plutôt le paradoxe des conséquences selon Max Weber. Vous savez, mon cher Bérard, ce sont des interdits, plus que des inhibitions. Certes la modernité tardive que j'appelle décadence se veut formellement libertaire. Elle entend bannir tabous et inhibitions au profit d'une spontanéité qui rejette les conventions... La civilité, la politesse, la galanterie... Toutes ces procédures qui cantonnent l'instinct agressif pour lisser l'interface ; en un mot l'élégance sociétale, c'est-à-dire le souci de l'autre. Il y a un risque d'anomie que les thuriféraires de soixante-huit ont largement contribué à magnifier en laissant croire que tous ces codes relevaient d'une aliénation d'essence autoritaire et bourgeoise... Les bourgeois sont d'ailleurs les premiers à s'en émanciper, et avec quel entrain... Ils sont l'avant-garde de l'anomie à venir, des enragés de la décivilisation.

P.B. - Après deux siècles de mimétisme, c'est l'ultime vengeance des bourgeois contre l'aristocratie déchue ?

J.F. - C'est un phénomène plus vaste, sans doute lié à l'individualisme. Ce n'est pas le sujet pensant des adeptes du progrès qui s'émancipe, mais l'ego de coeur et de tripes qui bouscule dans l'ivresse toutes les entraves à l'expression de son authenticité. Le jeunisme, c'est cela ; le " cool ", le sympa, le décontracté, la sacralisation d'une société adolescente libérée des contraintes de la forme. Or la vitalité brute, instinctive, sauvage, célébrée par ce culte de la sincérité et de la transparence, c'est la dénégation de la vie collective et de ces protocoles compliqués qu'on appelle tout simplement la culture. La culture, Bérard, c'est-à-dire depuis Cicéron, ce qui cultive en l'homme social la retenue, la discrétion, la distinction. Le dernier homme ne veut plus être apprivoisé par les usages, et c'est vrai que délesté des impératifs de la règle, il est ainsi persuadé d'avoir inventé le bonheur. La courtoisie, la bienséance, la civilité. Tout cela nous suggère-t-on, ce sont des salamalec, des trucs de vieux, des préjugés d'un autre âge et pire encore des mensonges ; et c'est contre la duplicité que dissimuleraient les rigueurs du savoir-vivre que l'on veut procéder au sacre des penchants.

P.B. - Je pense à Norbert Elias... Des siècles de patient dressage bousillés en une génération ?

J.F. - Oui... Et ce sont les élites, les gardiens traditionnels de la civilité qui donnent quitus à la brutalité de masse... C'est pathétique. Ce qui s'exprime aussi dans cette tendance à ramener tous les différends sur le terrain psychologique, c'est le refus de penser politiquement le monde.

P.B. - On ne pense plus en terme de tragédie, mais de mélodrame... C'est le couronnement du bourgeois.

J.F. - La bourgeoisie conquérante était une rude école disciplinaire, voyez encore Max Weber ... Ce type social est mort avec la précellence du désir.

P.B. - Un désir qui est aussi à la base du système marchand. " Prenez vos désirs pour des réalités ", c'est un parfait slogan de supermarché ou d'organisme de crédit ...

J.F. - J'avais de l'estime pour les situationnistes de Strasbourg, des étudiants brillants, un Tunisien surtout...

P.B. - Pas un beur...

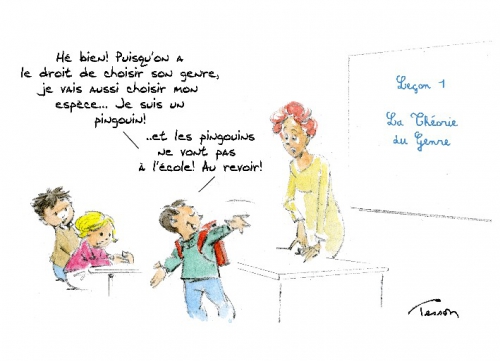

J.F - Ah non, il n'avait pas de petite main sur le coeur. Bien sûr le citoyen de la démocratie post-moderne est un consommateur, mais à l'horizon du désir sans borne c'est aussi un être trivial, un rustaud... un goujat et, surtout, surtout, j'y insiste, un être dont la violence instinctive n'est plus médiatisée par rien. Regardez ce qui se passe dans l'école de la République. Elle est " ouverte sur la vie " ; c'est la nouvelle mode, oh combien significative. Cela veut dire quoi ? Qu'elle a renoncé à être le sanctuaire où, à l'écart du monde justement, on entreprend le difficile polissage de l'enfant pour le rendre apte à l'urbanité, à l'entre soi de la cité.

P.B. - C'est la démocratie des enfants gâtés.

J.F. - Ah oui, dans les deux sens du mot ... Mais je reviens à notre propos de tout à l'heure. On a donc d'une part la juxtaposition potentiellement conflictuelle de groupes hétérogènes et d'autre part cette dramatique évolution des sociétés européennes qui débrident leurs anciennes disciplines et font crédit à la spontanéité du désir. Cette conjonction est explosive...Une société forte peut intégrer, mais la nôtre a renoncé à l'autorité....

Julien Freund s'est interrompu. Il considère son assiette avec une moue circonspecte et y promène du bout de son couteau un rogaton de munster.

- Ce fromage n'a pas la texture des munsters d'alpage ; je le trouve assez décevant.

P.B. -En été, quand les vaches sont à l'estive sur les chaumes, j'achète mon munster dans les ferme-auberges. C'est vrai, ce n'est pas le même fromage ; certains tirent même sur le reblochon. Vous le mangez sans cumin ?

J.F. - Là-dessus, je n'ai pas de religion établie. Est-ce que vous connaissez ce plat où mijotent pommes de terre, oignons et munster ? Ca se déguste avec du lard finement tranché et c'est parfait avec un riesling un peu minéral.

P.B. - C'est un plat de la région de Gérardmer, inconnu sur le versant alsacien des Vosges.

J.F. - Vous avez raison, les crêtes constituent aussi une frontière culinaire...Je voudrais préciser mon point de vue sur ce que je viens d'avancer, peut-être un peu trop hardiment. Comme je l'ai souligné dans ma Sociologie du conflit, il y a deux conditions pour qu'une crise dégénère en conflit. D'abord que s'affirme une bipolarisation radicale ; enfin, que le tiers s'efface. Tant que le tiers subsiste et parvient à affirmer son autorité, il n'y a guère de risque que la crise ne débouche sur un affrontement. Dans la société, la crise est une occurrence banale tant qu'il y a inclusion du tiers ; le conflit n'intervient qu'avec son exclusion. C'est cette exclusion qui est polémogène. Dans la situation présente du pays, le tiers est constitué par l'Etat et les différentes institutions qu'il patronne, comme l'école par exemple dont nous avons parlé, or non seulement l'Etat est frappé par la déshérence du politique, ce qui signifie qu'il se déleste de sa fonction cardinale qui est de pourvoir à la sûreté de chacun, mais les institutions subissent une sorte de pourrissement qui les rend de plus en plus inaptes à manifester leur vocation spécifique... Une distance culturelle qu'on ne parvient pas à combler entre l'immigration musulmane et le milieu d'accueil avec un danger de surchauffe violente, et un tiers en voie de dissolution ; cela, voyez-vous, me fait craindre le pire pour les années à venir.

P.B. - Les libéraux pensent que c'est le marché qui est intégrateur.

J.F. - Le goulag en moins, ce qui n'est pas mince, c'est une utopie aussi dangereuse que celle des Léninistes.

P.B. - L'ignominie du communisme, c'est qu'il a fini par rendre le libéralisme désirable !

J.F. - Vous avez le goût des paradoxes affûtés. Vous êtes sensible, je le sais, au phrasé de Baudrillard.

P.B. - Sa Société de consommation est un grand livre, non ?

J.F. -Peut-être, mais je trouve qu'en forçant le trait, il devient abscons. J'étais dernièrement à un colloque avec lui, à Gènes. Je n'ai pas compris où il voulait en venir, mais les Italiens étaient très sensibles à sa musique... Vous avez tendance à beaucoup le citer. Moi, je préfère la manière plus sobre de votre ami de Benoist ; c'est peut-être moins scintillant mais parfait dans l'argumentation, même si je n'adhère pas à certains de ses axiomes. Il a l'étoffe d'un véritable théoricien, et c'est un habile stratège dans le combat intellectuel ... C'est pourquoi je doute que vos adversaires, qui sont souvent les miens, vous le savez bien, commettent à nouveau l'erreur de 1979 et se risquent à vous donner la parole. La nouvelle droite a trop bien mûri ; cela vous condamne, au moins pour un temps, à la solitude... En tous cas, pour répliquer à cette farce du marché comme agent prétendu de l'intégration, il suffit de relire Durkheim. Il n'a pas vieilli sur ce point. Et que dit-il ? Que la prépondérance croissante de l'activité économique est une des raisons de l'anomie, donc, de la détresse de l'identité collective et de la désintégration sociale.

P.B. - Monsieur le professeur...

Julien Freund s'amuse de cette interpellation surannée. Jamais, cependant, malgré des années de complicité, je ne me suis départi à son égard de ces antiques politesses.

Julien Freund s'amuse de cette interpellation surannée. Jamais, cependant, malgré des années de complicité, je ne me suis départi à son égard de ces antiques politesses.

- Monsieur le professeur... Vous n'avez pas réagi à l'hypothèse que je formulai tout à l'heure concernant cette propension du discours antiraciste à favoriser malgré lui l'actualisation dans le quotidien de toute cette latence raciale, ethnique, tribale... Je voulais dire qu'en interpolant dans ses homélies... dans ses admonestations, de constantes références à ces classifications, il sollicitait pour ainsi dire ses destinataires à interpréter les problèmes de cohabitation qu'ils expérimentent dans ces termes-là. En bref, je suis tenté de penser qu'il contribue à " raciser " les tensions. D'autant que ce discours est performatif. Il vient quasiment du ciel...

J.F. - Ce n'est pas le ciel lumineux des idées selon Platon !

P.B. - ... C'est le pouvoir céleste du devoir-être. Sans compter que les curés y mettent aussi du leur.

J.F. - Pensez-vous sincèrement que les gens aient besoin d'être stimulés par ces élucubrations, même de façon oblique, pour ressentir les choses comme ils les ressentent ? Si l'on tient à établir un lien entre l'univers des discours et la manière dont les gens interprètent leur expérience, il y a selon moi quelque chose de plus frappant qui mériterait d'être creusé ; c'est cette occupation obsessionnelle de nos media par la seconde guerre mondiale ; plus exactement par le nazisme. Vous ne pouvez pas vous en souvenir, mais dans les années cinquante, soixante, Hitler était pratiquement oublié. Nous vivions dans l'euphorie de la reconstruction et, notre actualité politique, c'était quoi ? La guerre froide et les conflits coloniaux, c'est-à-dire des évènements concomitants. Les communistes célébraient pieusement le mensonge de leurs 75 000 fusillés et les anciens de la Résistance se retrouvaient rituellement devant les monuments aux morts. C'était tout. Ce passé, pourtant proche, était en cours de banalisation. Rien d'ailleurs que de très ordinaire dans cette lente érosion ; c'est un critère de vitalité. Aujourd'hui, en revanche, ce passé fait l'objet de constants rappels incantatoires. Hitler est partout, accommodé à toutes les sauces. C'est le nouveau croquemitaine d'une société qui retombe en enfance et se récite des contes effrayants avec spectres, fantômes et golem...

P.B. - Vous ne croyez pas aux revenants ?

J.F. - J'incline à penser que ces revenants sont utiles à certains. Hitler est devenu un argument polémique, et pas seulement en politique. A défaut de vouloir faire l'histoire contemporaine, nous fabriquons du déjà-vu, du simulacre, du pastiche. L'Hitlérisation du présent est un symptôme.

P.B. - La paramnésie ou impression de déjà-vu ; c'est un trouble hallucinatoire ; un signe de grande fatigue dit-on. Mais tous ces regards braqués sur le rétroviseur, cela veut dire aussi que l'avenir a perdu de son prestige. Il ne cristallise plus d'attente messianique. Le progressisme prend soudainement un coup de vieux.

J.F. - Sciences et techniques conservent leur ascendant, mais peut-être, effectivement, ne se prêtent-elles plus aux même amplifications eschatologiques qu'autrefois. L'écologisme grandissant est révélateur d'un désaveu. En tout cas ce Hitler qui nous hante, ce n'est pas celui dont nous célébrions la défaite en 1945, ce führer militariste, pangermaniste et impérialiste, ennemi de la France et de la Russie. Non ; celui qu'on commémore à tout instant pour en exorciser les crimes, c'est l'ethnocrate raciste, antisémite et genocidaire.

P.B. - On ne peut pas lui reprocher d'être anti-arabe ; c'est dommage.

J.F. - Anti-arabe, sûrement pas... le grand mufti de Jérusalem et même Nasser...

P.B. - Et Bourguiba parlant à Radio-Bari dans l'Italie de Mussolini.

J.F. - Le fascisme c'est tout autre chose ! Je vous donnerai une communication que j'ai faite à Rome sur ce sujet il y a quelques années.

P.B. - La mémoire imparfaite des nouveaux clercs confond allégrement les deux. C'est d'ailleurs l'épithète stalinienne de " fasciste " qui s'est finalement imposée...

J.F. - Mais vous n'êtes pas de leurs épigones... Bérard... Ce Hitler qui monte sans cesse à l'assaut du présent pour lui donner du sens, ce n'est pas un objet historique. Qu'est-ce qu'un objet historique ? C'est d'abord une matière suffisamment refroidie, tenue à distance des passions, autant que faire se peut. C'est ensuite une matière à travailler selon les règles éprouvées de la scientificité. Il a fallu plus de deux siècles pour les élaborer... et nous en sommes là ! Comme le diable des prêcheurs médiévaux, Hitler est devenu la caution négative d'une mémoire invasive et impérieuse. Il est interdit de se dérober à son appel sous peine de se voir soupçonné d'incivisme, voire d'obscure complicité avec...

P.B. - ... Avec la " bête immonde "...

J.F. - Pauvre Brecht ! Pour lui le ventre fécond, c'était celui de la social-démocratie. Et tous ces ignares qui le citent de travers !

P.B. - L'antifascisme commémoratif avance au même rythme que l'analphabétisme... Nous frisons l'excès de vitesse.

J.F. - Moi, je ne marche pas dans ces combines.

P.B. - La surexposition du nazisme est l'aliment principal de cette mémoire dont vous parliez. Ce qui me frappe, dans une époque qui se flatte d'obéir aux principes de la rationalité, c'est cette abdication de l'histoire face aux injonctions de la mémoire. Comme discipline en effet, l'histoire doit pouvoir rendre compte de ses matériaux et de ses méthodes, qu'il est toujours loisible de contester. La mémoire, elle, est infalsifiable. Elle s'impose comme un bloc de sensibilité. Elle n'a pas de méthodologie explicite. Ses critères sont flous, mais elle ne s'en impose pas moins comme une vérité inéluctable. Comme vous le suggériez à l'instant, il ne nous est pas permis d'en contester l'évidence sous peine d'anathème. Elle ne fait pas le partage entre le vrai et le faux, mais entre les bons et les méchants ; et c'est vrai que dans cette mesure, son triomphe engloutit tout un pan de l'esprit occidental. Cette volonté patiente de savoir, de débusquer le réel accessible, hors de tout préjugé fidéiste, de tout carcan dogmatique. La mémoire parle dans un idiome qui n'est pas universalisable, et, d'ailleurs, personne ne s'offusque de voir se répandre dans le langage courant des syntagmes comme " mémoire ouvrière ", " mémoire de l'immigration ", " mémoire juive ". Autant d'usages qui enregistrent et proclament la fragmentation particulariste dont il est derechef interdit de tirer des conclusions. Toujours, la mémoire s'authentifie comme un idiotisme et l'étrange, dans ces conditions, c'est qu'elle soit devenue l'argument fatal de ceux qui se réclament de l'universalisme...

J.F. - Ah, mon cher Bérard... Je préfère vous comprendre à demi-mot. Mais ce qui me frappe dans cette mémoire dont nous parlons, c'est son arrogance normative et cette morgue explicative, cette infatuation qui l'habilite à conclure en tous domaines.

P.B. - C'est l'ouvre-boîte universel... Comme ce célèbre couteau suisse à manche rouge, propre à tous les usages.

J.F. - Oui, mais en pratique, c'est le fameux couteau de Lichtenberg : il n'a pas de manche et il est dépourvu de lame. La suréminence de cette mémoire prend d'autant plus de relief qu'elle sévit dans une époque de rejet des filiations... d'amnésie massive. Et puis, c'est extraordinaire, son monolithisme sentimental. Un agrégat d'émotions n'est pas susceptible de la moindre tentative d'invalidation. Face à ça, nous demeurons médusés. Le mot qui convient le mieux pour décrire ce climat est celui d'hyperesthésie. Nous sommes à l'opposé de l'ascèse qui préside toujours à l'établissement d'un discours rigoureux. C'est encore Nietzsche qui dans La Volonté de puissance parle de cette irritabilité extrême des décadents... Oui, l'hyperesthésie fait cortège aux liturgies de la mémoire.

P.B. - C'est pourquoi sa carrière ne rencontre pas d'obstacle. Chacun se découvre quand passe la procession du Saint Sacrement. Personne ne veut finir comme le chevalier de la Barre.

J.F. - Voltaire nous manque, ou plus exactement cet esprit d'affranchissement qu'il a su incarner d'une manière si française...

P.B. - L'esprit de résistance ?

J.F. - La Résistance... Vous savez comme je l'ai faite dès janvier 1941. Pourtant, on fait circuler des rumeurs à mon propos... Je pense que cette mémoire manipulée participe de l'entreprise de culpabilisation des Européens.

P.B. - Ce passé ne vous protège pas contre l'infamie ?

Julien Freund laisse échapper un soupir de lassitude. Il regimbe à l'idée d'évoquer la forfaiture de ceux qui l'accablent en catimini.

J.F. - Vous savez, poursuit-il... le Résistant qui fut l'emblème héroïque des années d'après-guerre quitte aujourd'hui la scène au profit d'autres acteurs. Je ne m'en afflige nullement puisque j'ai toujours refusé les honneurs. Le Résistant, c'est un combattant, il fait en situation d'exception la discrimination entre l'ami et l'ennemi et il assume tous les risques. Son image ne cadre pas avec l'amollissement que l'on veut cultiver. C'est peut-être pourquoi on lui préfère aujourd'hui les victimes. Mais assurément, leur exemplarité n'est pas du même ordre. Ce que je voulais vous suggérer, j'y reviens, c'est la simultanéité de ces deux phénomènes ; le ressassement du génocide hitlérien et l'obsession antiraciste. Ils se renvoient sans cesse la balle dans un délire d'analogie. C'est extravagant. La mémoire produit un effet de sidération qui confisque l'immigration et nous interdit d'en parler autrement que dans le langage de son intrigue.

P.B. - La grammaire triomphante du génocide inaugure le règne de l'anachronisme et les nouveaux antiracistes bondissent d'émotion à l'idée d'entrer en résistance contre une armée de spectres.

J.F. - Oui... Ils sont à la fois la résistance et ses prestiges, et l'armée d'occupation avec ses avantages. C'est burlesque.

P.B. - Une mémoire incontinente...

J.F. - Qui épargne les crimes soviétiques, amnistiés avant d'avoir été jugés !

P.B. - Oui, mais leur finalité était grandiose ... la réconciliation définitive du genre humain, comme pour les antiracistes...

J.F. - Le seul communiste que j'ai connu dans la Résistance ; ce fut après mon évasion de la forteresse de Sisteron. Il dirigeait un maquis F.T.P. de la Drome. C'était un alcoolique doublé d'un assassin. A Nyons, il a flanché dans les combats contre les S.S. et je me suis retrouvé seul au feu avec quelques Italiens. Il fut néanmoins décoré d'abondance, et c'est pourquoi j'ai refusé toutes les médailles... à l'exception d'une médaille allemande !

P.B. - Ce qui mobilise la mémoire unique, ce n'est pas tant la liquidation du passé que sa persécution réitérée. Non seulement la mémoire met l'histoire en tutelle mais elle s'érige en tribunal suprême. Sous son regard myope, le passé n'est qu'une conspiration maléfique. On arraisonne les morts pour les accabler de procès posthumes et dénoncer leurs forfaits. Il n'y a jamais de circonstances atténuantes.

J.F. - C'est la rééducation du passé par les procureurs de l'absolu. Cette génération hurlante n'a connu que la paix ; ce sont des nantis de l'abondance qui tranchent sans rien savoir des demi-teintes de l'existence concrète dans les temps tragiques. L'ambivalence et les dilemmes sont le lot de ce genre d'époque. Nos pères ne furent pas des couards.

P.B. - La vertu n'a que faire de la vérité et vous voici, vous, Julien Freund, agoni comme ci-devant Résistant...

J.F. - " Ci-devant Résistant " ! Celle-là, on ne me l'avait jamais faite...

Le rire massif de Freund écrase la salle de sa gaieté. Le restaurant est vide depuis un bon moment déjà, mais le patron, derrière son comptoir, ne moufte pas. A Villé, on ne dérange pas le professeur, ce monsieur tellement affable et qui a écrit tant de gros livres.Penché sur la table dont il a écarté assiettes et couverts, il reprend le fil de ses pensées en martelant les mots.

J.F. - Le Bien ne fait pas de concession. Les croisés du Bien ne connaissent pas le doute. Les fins sublimes qu'ils s'assignent balayent tous les scrupules.

P.B. - La réconciliation définitive après la lutte finale contre la xénophobie...

J.F. - La xénophobie, c'est aussi vieux que le monde ; une défiance de groupe, d'ordre comportementale, vis à vis de l'étranger. L'expression d'un ethnocentrisme universel comme l'a rappelé Lévi-Strauss. On veut aujourd'hui la confondre avec le racisme qui est un phénomène moderne ; la confondre pour lui appliquer à elle aussi le sceau de la réprobation. Certes, il y a aussi des expressions chauvines de l'ethnocentrisme qu'il convient de combattre, mais prétendre le réduire absolument, c'est parier sur un avenir où l'idée de société différenciée avec ses particularismes aurait complètement sombré. Il n'y a d'ethnocentrisme et de xénophobie que dans la mesure où il y a pluralité des mondes. On peut imaginer - pur exercice d'utopie - que l'effacement des communautés et des identités collectives aboutirait à l'extinction de la xénophobie ; mais en fait à quoi ressemblerait cet Eden ? Selon la fiction de Hobbes, ce serait le retour à la lutte de tous contre tous... une lutte implacable et continuelle, dont seule nous protège la constitution de l'humanité en sociétés organisées et rivales.

P.B. - La xénophobie, c'est donc le prix à payer pour prévenir la barbarie.

J.F. - Si vous dites ça comme ça, vous serez vous-même traité de barbare !

Julien Freund rit longuement, ressert une rasade de pinot noir et s'offre un excursus pointu sur l'origine des différents cépages alsaciens. Et, comme toujours lorsque la conversation prend ce tour grave qui sied au plaisir du boire et du manger, il surligne d'un index didactique ses propos les plus définitifs. Nous buvons...

Julien Freund rit longuement, ressert une rasade de pinot noir et s'offre un excursus pointu sur l'origine des différents cépages alsaciens. Et, comme toujours lorsque la conversation prend ce tour grave qui sied au plaisir du boire et du manger, il surligne d'un index didactique ses propos les plus définitifs. Nous buvons...

- Moi aussi, reprend-il après ces longues minutes, je dois être un barbare... La presse italienne, savez-vous, m'accuse avec Alain de Benoist et quelques autres d'être l'inspirateur des récents attentats dans la péninsule... Que répondre à de telles affabulations ? Notre ami répond-il à ces balivernes ?

P.B. - C'est probable, mais les droits de réponse sont souvent caviardés et la procédure judiciaire est coûteuse. Face à nos détracteurs le combat est inégal.

J.F. - Il n'est pas honorable, ni même utile, de se faire passer pour des martyrs ; l'iniquité étant la règle du jeu, il faut, non pas s'en accommoder, mais déplacer le champ polémologique et viser, non pas les ramasse-crottes du journalisme mais ceux qui les inspirent. C'est à l'amont de l'écriture quotidienne du journal que se situent les véritables enjeux... Le reste, comme disait de Gaulle, c'est l'intendance...

Cette question de la Résistance me turlupine, vous savez, et vous me poussez à mieux définir ma pensée. Jonglant avec ce que j'ai appelé ailleurs " fascisme spécifique " et " fascisme générique ", l'agit-prop communiste a fabriqué une conception à la fois fausse et infiniment extensive du fascisme allégrement confondu avec le nazisme... Soit. Le communisme pourrait disparaître mais l'antifascisme parodique survivra à son géniteur, car il arrange trop de monde. Ce fricot, il est toujours sur le feu. Les dispositifs médiatiques de manipulation de l'imaginaire l'ont installé dans l'opinion comme un mode d'interprétation idéaltypique de l'histoire contemporaine. Il faut donc s'attendre à des rechutes à n'en plus finir d'autant que l'analphabétisme historique s'étend au rythme même de l'emprise journalistique sur la culture ambiante. Et ces récidives antifascistes sont d'autant plus inévitables que le fascisme a été érigé en clé de voûte maléfique de tout un appareil de brouillage idéologique et de coercition morale. D'ailleurs le refus de prescrire les crimes qui lui sont liés, et seulement ceux-là, en dit très long sur ce statut d'exception, car c'est toute la tradition européenne du droit qui est ici mise en cause... Une telle adultération de notre humanisme juridique ouvre la voie à des procédures à répétition avec mise en spectacle idoine... Bref, je disais tout à l'heure que le souvenir de la Résistance combattante devait s'effacer parce que son image renvoie d'une manière trop explicite au patriotisme. Il y a donc bien une contradiction entre le recyclage continue d'un fascisme mythique et malfaisant et l'occultation progressive de ceux qui ont combattu le fascisme réel, les armes à la main. Cette bizarrerie tend à montrer que le même mot renvoie bien à des réalités différentes... La Résistance est partie prenante de l'ancien monde, celui des réflexes vitaux qui se mettent en branle lorsque le territoire est envahi par l'ennemi. Les nouvelles de Maupassant montrent très bien cela dans un contexte où le nazisme n'avait pas cours. Or, c'est ce lien quasiment paysan à la terre que l'on prétend aujourd'hui abolir parce que les élites, elles, se sont affranchies de ces attaches... Elles deviennent transnationales et discréditent des liens qui sont pour elles autant d'entraves. Dans ce contexte, le maquisard devient un personnage encombrant... Trop rivé à son sol, à ses forêts, à sa montagne...

P.B. - Un franchouillard à béret basque, un chouan...

J.F. - Sans aller jusque là, il n'est plus le prototype de l'avant-garde historique.

P.B. - Sauf s'il est Arménien, républicain espagnol ou déserteur de la Wehrmacht.

J.F. - Oui, l'Affiche Rouge, qui renvoie à la dimension internationaliste... Le fait que des intellectuels à prétention cosmopolite se mettent à critiquer les programmes de certains mouvements comme celui d'Henri Frenay en leur imputant des arrière-pensées pétainistes est révélateur de ce nouveau climat. Au nom de la démystification, il s'agit de priver la Résistance de son prestige. Non seulement la plupart des Français auraient été attentistes ou collaborationnistes, mais même la petite frange des résistants de la première heure devrait être soupçonnée des pires ambiguïtés.

P.B. - Jusqu'en 1942 au moins, beaucoup de résistants ne se définissent pas comme opposants à Pétain et il y a parmi eux de nombreux officiers et même des camelots du roi.

J.F. - Bien sûr, les frontières demeurent floues et c'est justement ça que l'antifascisme rétrospectif ne peut pas comprendre, car il ne fonctionne que dans le cadre d'un manichéisme reconstruit à partir du légendaire communiste. En dépouillant la Résistance de son aura, on dépossède les Français d'un passé glorieux pour les assigner à leur essence perfide. Ils sont déshérités et reconduits à la guerre civile latente et permanente... et par ceux-là même dont la fonction est de fabriquer du consensus.

P.B. - Même au prix du mensonge ? Car enfin, les résistants, comme les collaborateurs, ne furent qu'une minorité.

J.F. - Mais oui, mon cher Bérard, au prix du mensonge !

Dépourvu d'afféterie, Julien Freund s'amuse à jouer avec ces blasphèmes innocents. Son visage alors se craquelle de mille rides et se pétrifie dans un rictus silencieux. Il fixe longuement l'interlocuteur puis cède d'un seul coup à la plus franche hilarité.

- Le mensonge, tonne-t-il à nouveau tandis que le masque se fait plus sévère... C'est Machiavel qu'il faut suivre. Certes, il n'y a pas de politique morale, mais il y a une morale de la politique qui implique parfois le mensonge quand celui-ci est utile à la concorde intérieure... Une fois désenchantée, la Résistance ne peut plus être un gisement de mémoire et l'opprobre inocule désormais toute notre histoire... Vous comprenez, la sphère du politique n'est pas celle de l'histoire. L'histoire obéit à des méthodes critiques qui aboutissent nécessairement au désenchantement ; son rôle est démystificateur. Sous son emprise le passé devient trivial. Mais là, c'est autre chose... C'est autre chose pourquoi ? Mais parce que le changement de perspective auquel nous assistons n'est pas le produit de la réflexion historique. Ceux qui le conduisent sont indifférents aux archives ; ce ne sont pas des chercheurs, mais des idéologues. D'ailleurs, aucun chercheur ne pourrait disposer de l'écho médiatique dont ils jouissent. Cet écho démesuré montre que leur discours entre en résonance avec les intérêts du pouvoir, pour des raisons que j'ignore...De même que le résistancialisme des années cinquante permettait de blanchir le passé, et d'amnistier les collaborateurs, la profanation du mythe résistant, d'une France toute entière insurgée contre l'occupant permet de le noircir. De la magie blanche à la magie noire, il y a comme une transfusion de signification, mais on demeure dans la magie ; pas dans l'histoire. Car, si le sens du récit bascule, on ne le doit pas à des découvertes inattendues, à des connaissances nouvelles. Seule change l'interprétation. Hier, elle servait à bonifier. Aujourd'hui, elle s'acharne à péjorer. C'est toujours de la prestidigitation !

Julien Freund soupire, mais son regard pétillant de malice dément l'impression d'accablement qu'un observateur distrait pourrait tirer d'une pareille attitude. Sa respiration exhale un bruit de forge. Il s'éclaircit la voix, finit son verre et poursuit.

- Le mensonge de l'immédiat après-guerre colportait la fable d'une France occupée rassemblée derrière de Gaulle. Le mythe était soldé par la condamnation hâtive d'une poignée de traîtres choisis parmi les figures les plus visibles de la littérature et de la politique. Cette imposture avait une finalité politique honorable ; c'était une thérapie collective pour conjurer la discorde et abolir le risque d'une guerre civile sans cesse perpétuée... Le tournant s'est opérée dans les années soixante-dix, à la fin justement des Trente glorieuses. Ce qui n'était jusque là qu'une poignée de brebis galeuses est devenue l'expression la plus éloquente d'un peuple de délateurs et de renégats. C'est alors qu'on a commencé de parler d'une épuration bâclée et trop rapidement conclue. Epilogue fatal : puisque le crime était collectif, c'est bien la nation dans son essence qui était viciée. Il lui fallait donc expier massivement. C'est aussi à cette époque que de l'Inquisition aux Croisades et aux génocides coloniaux l'ensemble de notre histoire s'est trouvée indexée à la collaboration et à ses turpitudes... Maintenant elle envoûte de sa malédiction l'ensemble du passé... Peut-être est-ce lié au progressisme qui situe le meilleur dans l'avenir et doit en toute logique déprécier le passé pour le ravaler à l'obscurantisme et à la sauvagerie ? Mais les Trente glorieuses pourtant ont été furieusement prométhéennes sans que n'y sévisse ce masochisme extravagant. Il s'agit donc bien d'un phénomène plus profond qu'il faut rapporter à cette morbidité européenne dont nous parlions tout à l'heure.Ce que je constate, voyez-vous, c'est que durant trente ans, les élites, usant d'un pieux mensonge... oui, un bobard... ont célébré un peuple exemplaire en le dotant d'un passé glorieux. Et, simultanément, ces élites se montraient capables d'entraîner le pays dans une oeuvre imposante de reconstruction, jetant les bases d'une véritable puissance industrielle, promouvant la force de frappe nucléaire, s'engageant dans la réconciliation avec l'Allemagne et l'édification d'un grand espace européen tout en soutenant plusieurs conflits outre-mer. Nonobstant certaines erreurs, ce fut un formidable effort de mobilisation stimulé par une allégresse collective comme la France n'en avait pas connue depuis longtemps...

P.B. - Tout cela malgré les faiblesses dont on stigmatise la quatrième république.

J.F. - Je connais ces critiques puisque, comme vous le savez bien, je suis gaulliste comme je suis aussi européen et régionaliste... mais la nature des institutions n'a ici qu'une faible pertinence. C'est la pâte humaine qui est décisive et les grands courants d'idée et d'humeur qui traversent la population. La rhétorique n'est pas sans conséquence ; il y a des récits toniques et d'autres qui, en revanche, nourrissent la neurasthénie. Dans l'ordre du discours, nous sommes passés de l'éloge à la disgrâce, de la gratification à l'affliction. Pareto associait déjà la décadence et le mépris de soi. C'est dans Les systèmes socialistes qu'il écrivait : " On éprouve une âpre volupté à s'avilir soi-même, à se dégrader, à bafouer la classe à laquelle on appartient, à tourner en dérision tout ce qui, jusqu'alors, avait été cru respectable. Les Romains de la décadence se ravalaient au niveau des histrions. "

La mémoire livresque de Julien Freund est surprenante. Il détient dans ses réserves des milliers d'extraits, parfois très longs. Il en émaille sa conversation savante avec le souci constant de rembourser sa dette vis à vis de grands textes. L'art de la citation est toujours chez lui un exercice d'humilité, une manière de reconnaître que beaucoup d'autres ont inscrit leur empreinte dans sa propre pensée. C'est dire tout ce qui le distingue de l'enflure pédante de ces clercs qui abritent leur arrogance derrière le rempart des signatures prestigieuses. Julien Freund, lui, ne cède pas au goût du décor ; il fait vibrer la pensée des Anciens et, c'est toujours amarré à ces références patiemment ruminées qu'il affronte les problématiques du présent. Car, en effet, il rumine, triture et mâchonne comme le conseillait Nietzsche. Lenteur délibérée de la méditation ; tempo ralenti d'une pensée qui se construit par sédimentation et élagage ; discipline de la prudence, exercice du doute probatoire... Tout un univers qui fait contraste avec l'impulsion qui étend partout son empire au nom d'une authenticité factice et d'urgences fantasmatiques.

La mémoire livresque de Julien Freund est surprenante. Il détient dans ses réserves des milliers d'extraits, parfois très longs. Il en émaille sa conversation savante avec le souci constant de rembourser sa dette vis à vis de grands textes. L'art de la citation est toujours chez lui un exercice d'humilité, une manière de reconnaître que beaucoup d'autres ont inscrit leur empreinte dans sa propre pensée. C'est dire tout ce qui le distingue de l'enflure pédante de ces clercs qui abritent leur arrogance derrière le rempart des signatures prestigieuses. Julien Freund, lui, ne cède pas au goût du décor ; il fait vibrer la pensée des Anciens et, c'est toujours amarré à ces références patiemment ruminées qu'il affronte les problématiques du présent. Car, en effet, il rumine, triture et mâchonne comme le conseillait Nietzsche. Lenteur délibérée de la méditation ; tempo ralenti d'une pensée qui se construit par sédimentation et élagage ; discipline de la prudence, exercice du doute probatoire... Tout un univers qui fait contraste avec l'impulsion qui étend partout son empire au nom d'une authenticité factice et d'urgences fantasmatiques.

Machiavel, raconte Julien Freund, fut proscrit plusieurs années dans une bourgade, à bonne distance de Florence. Dans une lettre datée de son exil, il confie comment après avoir vaqué durant la journée aux affaires quotidiennes, il regagne le soir sa maison, revêt ses habits princiers et pontificaux pour se retrouver en compagnie des grands auteurs du monde antique. " Je les interroge et ils me répondent ", écrit-il superbement... Si donc, la citation chez Julien Freund n'est jamais pontifiante, elle veut en revanche signifier que dans la guerre des idées, il n'est pas un voyageur sans bagage. Les auteurs qui lui répondent en attestent. Entre eux et lui se nouent des amitiés posthumes où l'on voit s'esquisser le motif de la tradition. La tradition ; non pour s'embourber dans une répétition stérile - référence n'est pas révérence - mais pour suggérer ces permanences essentielles auxquelles nous avons donné le nom de civilisation. Acquiescer à l'héritage et l'enrichir à des sources nouvelles. Julien Freund est aussi un passeur. Il contribue à la réception française de Max Weber, de Vilfredo Pareto et surtout de Carl Schmitt ; et dans ce dernier cas, il n'hésite pas à franchir l'Achéron à ses risques et périls. La citation n'est pas toujours une occupation de tout repos.

- Nous sommes entrés dans un nouveau cycle, poursuit Julien Freund. Aux laudes de l'après-guerre les élites ont substitué une autre musique en vouant nos prédécesseurs aux gémonies. En bref, elles vitupèrent et sermonnent, embarquant le pays dans une véritable industrie du dénigrement. Et, qu'est-ce qui accompagne cette remontrance continuelle, qu'est-ce qui fait cortège à cette mémoire mortifiante ? Depuis les années soixante-dix, c'est une dénatalité préoccupante, un délitement alarmant du lien social, une extension de l'anomie et de la violence sauvage, une croissance structurelle du chômage installant des millions de nos concitoyens dans l'assistance et l'irresponsabilité, alourdissant le poids de l'Etat-providence, et pour clore la litanie des décombres, une démobilisation civique effrayante... Et je n'évoque que pour mémoire la détresse du politique, si révélatrice de l'aboulie de la volonté.

Oui, je maintiens qu'en politique il faut savoir mentir à bon escient ; non pour dissimuler la corruption du pouvoir comme on le voit faire si souvent aujourd'hui, mais pour doter les vivants d'un passé supportable, rasséréner l'identité collective, renforcer l'estime de soi. Des élites qui accablent les morts pour fustiger leur peuple ne sont pas dignes de le gouverner. " Salus populi suprema lex esto ", mon cher ; cet adage, Pareto le rappelle après Hobbes, c'est le but de la politique. La protection de la collectivité par la ruse comme par la force. La ruse du discours afin de servir un roman national suffisamment vraisemblable pour ne pas laisser le champ libre au persiflage et suffisamment gratifiant pour agréger les énergies. La force étant ici celle, pondérée, de l'institution, distincte de la violence caractéristique, elle, du chaos qui s'avance.Je note, par ailleurs, qu'après ce qu'on a appelé leur " miracle ", l'Italie comme l'Allemagne connaissent aujourd'hui une évolution comparable à la nôtre. En Allemagne notamment, la diffamation du passé a pris une dimension délirante qui n'épargne même pas la Prusse du despotisme éclairé, un Etat qui fit l'admiration de tous nos philosophes de Voltaire à Renan... Toute réminiscence y renvoie à la faute et au procès au point que les jeunes générations se trouvent condamnés au plus extrême dénuement historique... Des orphelins privés d'héritage et soumis au joug d'un éternel présent !

Rappelez-vous ce que dit le dernier homme de Zarathoustra. Il dit " Jadis tout le monde était fou ". Et il ajoute en clignant de l'oeil : " Qu'est-ce qu'aimer ? Qu'est-ce que créer ? Qu'est-ce que désirer ?" Il exprime en même temps le sentiment de supériorité de l'homme moderne et son incapacité à donner sens aux verbes aimer, créer, désirer ; les actions élémentaires de l'existence. L'homme moderne en rupture d'antécédant est condamné à l'indigence et à la stérilité ; il n'est plus créateur... Vantardise et impuissance voilà son apanage ! En l'occurrence, pour ce qui concerne l'Allemagne, l'hyper morale y secrète une fausse conscience qui confine à une dénationalisation brutale et dangereuse... Oui, la pénitence est devenue tout à la fois l'outil imparable et le solennel alibi d'un vandalisme inédit.

P.B. - C'est la furia teutonica enrôlée cette fois contre ses propres assises. Il ne s'agit pas tant de révoquer l'histoire que de la rendre présente, sans cesse, comme un remord incurable. Jusque dans la tombe l'oeil réprobateur pétrifie le Caïn germanique pour lui inspirer une honte éternelle... Il lui est interdit de boire les eaux du Léthé...

J.F. - Les Anciens connaissaient les vertus pacifiantes de l'oubli ; mais les nouveaux prédicateurs veulent-ils la paix ?

J.F. - Les Anciens connaissaient les vertus pacifiantes de l'oubli ; mais les nouveaux prédicateurs veulent-ils la paix ?

P.B. - Harcelés par des antécédents criminels mais pressés de se faire admettre dans l'humanité post-totalitaire, les Allemands se sont faits récemment les oblats opiniâtres d'une nouvelle coquecigrue ; le patriotisme constitutionnel à la Habermas...

J.F. - Du point de vue sociologique, c'est une absurdité, car il n'y a pas de société qui pourrait être une création ex-nihilo. Il n'y a pas d'être-ensemble sans ancrage identitaire. Les groupes humains ne peuvent pas vivre en apesanteur. La théorie d'Habermas, c'est une nouvelle version du syndrome utopique qui travaille les idéologues depuis le XVIème siècle, mais elle est révélatrice d'une aporie. Elle prétend en effet fonder son patriotisme sur l'abjuration des pères. Il s'agit donc de tout autre chose que de patriotisme...

P.B. - Illustration de la pseudomorphose selon Spengler. Le mot demeure incrusté dans la langue, mais il a changé de signifié.

J.F. - Il ne désigne plus que des nuées... Déguisé en Ayatollah de la vertu, Habermas profère des fatwas. Il se félicite de la débâcle des méchants qui depuis toujours auraient précipité l'Allemagne dans un bellicisme sanglant...

P.B. - Depuis que les Chérusques firent un mauvais sort aux légionnaires romains de Varus ?

J.F. - Pourquoi pas, pendant qu'on y est ! Après avoir déblatéré sans répit, quand tout a été déblayé, épuré, à quel fondement accrocher l'être collectif allemand ? Les fondements nous précèdent nécessairement. Mais quand tout ce qui nous précède est condamné à la débandade, sur quoi fonder la légitimité ? Sans doute sur un futur immaculé puisque imaginé selon les seuls mécanismes de la raison désincarnée... C'est l'essence même de l'utopie progressiste.

P.B. - Si nous résumons nos propos, nous pouvons dire que recru de brimades, le passé est aujourd'hui en déroute. Ajoutons qu'on en exhume les fonds de tiroirs que dans le seul but de nous jeter à la face les preuves de notre constante cruauté. Mais il y a autre chose. A propos des Allemands vous venez de parler de génération orpheline. La scélératesse des pères empêche en effet qu'on s'en réclame ingénument. Les mères en revanche paraissent mieux s'en tirer. Le discours contemporain, encore une fois depuis les années soixante-dix, tient de toute évidence à les disculper. Et pour ce faire, il les enrôle sous la bannière du féminisme, dans ces catégories souffrantes que les " mâles, blancs, morts ", comme on dit sur les campus américains, auraient depuis toujours tenues sous leur férule.

J.F. - Ma réflexion ne m'a jamais conduit vers ces questions, mais vos remarques sur le féminisme me ramènent à Auguste Comte, un penseur que j'ai beaucoup pratiqué. Comte, vous le savez, est l'inventeur du concept de sociologie. Comme les contre-révolutionnaires de son temps, il est conscient de la béance ouverte par la Révolution de 1789 ; c'est ainsi qu'il parle de l'immense gratitude des positivistes vis à vis de Joseph de Maistre et qu'il révoque les faux dogmes de l'individualisme et de l'égalitarisme. Il se veut tout autant l'héritier que le liquidateur de la Révolution. Comment surmonter l'individualisme dissolvant des modernes ? C'est à cette question qu'il tente de répondre et il le fait de manière mixte. En effet, à la différence des contre-révolutionnaires qui proposent une solution rétrograde assise sur la restauration du trône et de l'autel, Comte partage la certitude des Lumières selon laquelle l'humanité tend irrésistiblement vers l'unité cosmopolite. Cette convergence planétaire qu'il voit s'accomplir, comme les libéraux, par le truchement de l'économie, il entend la parachever et la corriger au moyen d'une nouvelle religion. Pour lui, il ne fait pas de doute qu'une communauté humaine ne peut assurer la fonction intégratrice nécessaire à la durée que par le lien religieux. Cette nouvelle religion fait la part belle aux savants, aux prolétaires et surtout aux femmes qu'il dépeint comme les préceptrices idéales de l'altruisme. Le féminisme de Comte reflète la prépondérance qu'il attribuait au sentiment. Une telle assimilation lui vaudrait sans aucun doute les sarcasmes, voire l'ire des féministes d'aujourd'hui.

Julien Freund débride un de ces rires énormes dont il n'est pas avare. L'effet désopilant du topique comtien sur les pétroleuses contemporaines excite sa gaieté. Puis, comme de coutume, il brise net l'hilarité et poursuit son exposé...

Bref, c'est la puissance affective impartie au coeur féminin qui permet de recoudre les lambeaux d'une société mise à mal par le bouleversement de 1789. Comme l'a montré Robert Nisbet, c'est toute la problématique de la sociologie naissante. Qu'est-ce qui peut relier les hommes quand ils ne sont plus confinés dans les ordres traditionnels et leurs réseaux d'obligations réciproques, quand l'obéissance ne va plus de soi ? Ce n'est pas tant la réponse constructiviste, en fait une religion d'intellectuel, qui fait l'originalité de Comte que le rôle souverain qu'il confère aux femmes, prophétesses d'une humanité régénérée. Cimentée par la religion de l'humanité, sa société positive met un terme aux errements de l'histoire humaine et ce dénouement... c'est ça qui est important, correspond avec la consécration du genre féminin.

P.B. - Culmination sociale de la femme et fin de l'histoire composent donc un système cohérent ?