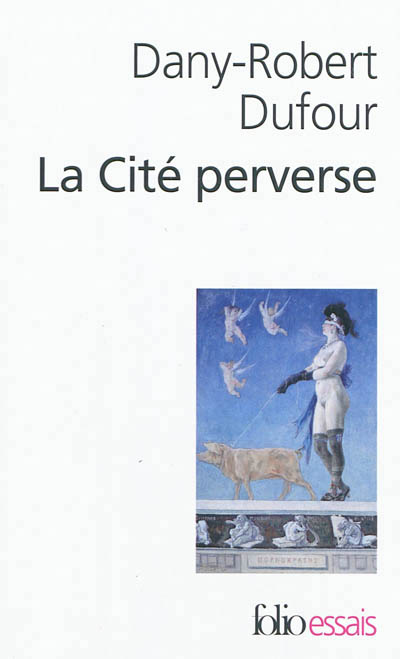

La cité perverse : libéralisme et pornographie

Entretien avec Dany-Robert Dufour : Autour de la Cité perverse

Ex: http://fortune.fdesouche.com

A : Généalogie d’un libéralisme « ultra »Actu-Philosophia :

Tout d’abord, je vous remercie de me recevoir, pour cet entretien autour de votre ouvrage La Cité Perverse. Libéralisme et pornographie [1], ce qui nous donnera l’occasion d’aborder le reste de votre œuvre, qui se compose à ce jour de plus d’une dizaine d’ouvrages, de très nombreuses collaborations à des revues et journaux (Le Débat, Le Monde Diplomatique, Le Monde, l’Humanité, etc.), et de vos enseignements en tant que professeur en philosophie de l’éducation à l’université Paris-VIII, ainsi qu’au sein d’universités sud-américaines (Colombie, Mexique, Brésil).

Dans La Cité Perverse, livre publié aux éditions Gallimard en 2011, vous expliquez que, sans vouloir faire œuvre de moraliste, vous souhaitez mesurer les effets de la perversion, de l’obscénité que nos sociétés postmodernes poussent à leur paroxysme.

Dès le prologue, vous expliquez vouloir créer une science, la « pornologie générale », consacrée « à l’étude des phénomènes obscènes, extrêmes, outrepassant les limites, portés à l’hybris […], survenant dans tous les domaines relatifs au sexuel, à la domination ou à la possession et au savoir, qui caractérisent le monde post-pornographique dans lequel nous vivons désormais. »

La crise financière qui a touché le monde en 2008 semble avoir été révélatrice d’une crise bien plus profonde et bien plus large que celle de l’économie financière, et de ce qu’il n’y a, d’ailleurs, pas qu’une seule crise, mais plusieurs, de la même manière qu’il existe un grand nombre d’économies humaines. Quelles sont, selon vous, les causes de que vous décrivez comme un véritable changement de paradigme civilisationnel ?

Dany-Robert Dufour : Quand j’ai commencé à travailler sur cette question, je me suis interrogé sur le tournant qui a été pris il y a maintenant une trentaine d’années, qui est le tournant dit « ultra-libéral » ou « néo-libéral », pour m’interroger sur sa nature. Souvent, on analyse l’ultra-libéralisme ou le néo-libéralisme (ce qui n’est pas tout à fait la même chose), dans le seul champ de l’économie marchande. Or, essayant de faire une généalogie du libéralisme, j’ai trouvé que dès le début celui-ci était une pensée totale. Et cela m’a fait remonter bien avant 1980 et la prise du pouvoir par Reagan aux Etats-Unis et Thatcher en Angleterre, à ce moment de naissance de la pensée libérale comme pensée complète, pas seulement économique.

Ce fut tout l’enjeu de mon travail dans La Cité Perverse : montrer comment notre métaphysique occidentale subissait une espèce de renversement majeur, puisque l’on passait globalement, entre 1650 et la fin du XVIIIe siècle, du principe qui avait toujours été avancé depuis l’augustinisme, l’amour de l’autre, à l’amour de soi. Il y avait véritablement là, dans la métaphysique occidentale un tournant, qui est bien illustré par Bernard de Mandeville, cet auteur que j’ai contribué, avec d’autres, à sortir de l’oubli et qui a écrit La Fable des Abeilles (1705). Ce texte a récemment reparu en deux volumes puisque outre la fable, on y trouve tous les commentaires de celle-ci faits par Bernard de Mandeville.

La fable avance une maxime nouvelle, au double sens de raison pratique et de morale d’une fable. Il est significatif que Mandeville donne en guise de nouvelle morale que l’ensemble des vices privés peut se transformer en vertus publiques. C’est cette équation – puisque c’est véritablement une équation – qui m’a donné beaucoup à penser, puisque cela revient sur ce que les Grecs nommaient l’epithumia (l’âme d’en bas), les « esprits animaux » chez Mandeville, qui devaient être, non plus réprimés, mais libérés.

Bernard de Mandeville analysait en quelque sorte l’histoire humaine comme une longue erreur, celle de la répression des vices privés. Il disait qu’en libérant les vices privés, l’on résoudrait tous les problèmes en devenant riches. Car la richesse permet le développement des arts, des sciences, de toute une série d’artifices que nous n’avions pas avant. Et c’est donc ce qui m’a intéressé : ce moment où la métaphysique occidentale est passée d’un principe à un autre.

Dans les vices privés, il y a le goût de l’avidité (greed en anglais) ; le fait d’avoir toujours plus (ce que les Grecs appelaient la pléonexie). Bernard de Mandeville dit que c’est une bonne chose, puisqu’en voulant toujours plus, on produit toujours plus de richesses, et cela est bon pour tout le monde. Ce qui s’entend parfaitement dans le second sous-titre de la fable : “Soyez aussi avide, égoïste, dépensier pour votre propre plaisir que vous pourrez l’être, car ainsi vous ferez le mieux que vous puissiez faire pour la prospérité de votre nation et le bonheur de vos concitoyens“. Ce qui peut se condenser en “il faut laisser faire les égoïsmes”.

En outre, il ne faut pas oublier que Bernard de Mandeville a aussi écrit un petit livre amusant qui s’appelle Vénus la Populaire, qui est rien de moins qu’une défense et illustration des maisons de joie, des maisons publiques. Tout cela en étant calviniste ! Pourquoi souhaitait-t-il les défendre ? Parce que c’est une promesse de richesse, car, si la prostitution est peut-être une faute morale pour ceux qui s’y adonnent, c’est aussi une richesse potentielle, car la prostituée, pour plaire à ses clients, va solliciter le couturier, qui devra lui faire de beaux atours, et ce couturier de pauvre qu’il était pourra devenir riche et grâce à cela pourra envoyer ses enfants à l’école. Grâce à qui ? A la prostituée. Et, en faisant le raisonnement de proche en proche, le couturier lui-même va devoir demander de beaux draps au drapier, qui lui aussi pourra devenir riche et envoyer ses enfants à l’école et ainsi faire progresser le niveau de culture et d’éducation du peuple. Donc, tous les vices sont utiles, même le vol. Le voleur est celui grâce auquel l’on pourra développer le droit –ce qui implique de construire des universités, de former des professeurs, des juristes, etc. Tout cela grâce au voleur, sans lequel il n’y aurait nul besoin d’avocats, de professeurs de droit, de prisons et d’architectes pour les construire. C’est donc grâce au vice privé qu’une société s’enrichit et fabrique, sans qu’elle le veuille absolument, la vertu publique.

J’ai considéré que, dans cette proposition absolument fondamentale bien que paradoxale, résidait le cœur de la pensée libérale. Elle est résumable ainsi : le vice privé fait la vertu publique, et ce dans tous les domaines. Le premier sous-titre de la fable, qui vaut comme morale de la fable, dit d’ailleurs : « Les vices privés font le bien public, contenant plusieurs discours qui montrent que les défauts des hommes, dans l’humanité dépravée, peuvent être utilisés à l’avantage de la société civile, et qu’on peut leur faire tenir la place des vertus morales. »

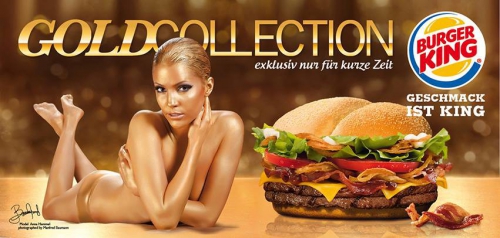

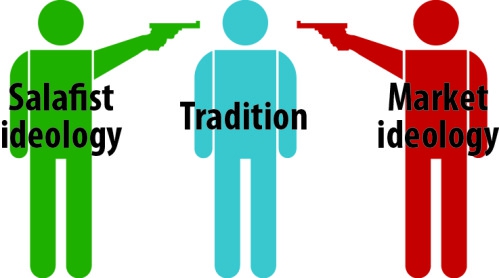

On peut lire dans ces propositions, le fondement anthropologique du libéralisme qui fut un des deux courants essentiels des Lumières. Car, contre le libéralisme anglais, s’est développé l’autre courant, le transcendantalisme allemand, notamment avec Kant, qui apporte l’idée de loi morale, selon laquelle je ne peux pas faire n’importe quoi pour mon propre plaisir ou mon propre intérêt, puisque je dois m’interroger sur la possibilité d’ériger mes actions en loi générale. J’ai analysé la modernité comme l’opposition des deux Lumières, anglaises et allemandes, opposition qui fut très féconde et que je considère comme les deux « chiens de faïence » posés sur la cheminée de la modernité, l’un tirant dans le sens de la loi morale, l’autre dans celui de la libéralisation des vices privés. Cette modernité a duré jusque vers les années 1980, à partir desquelles nous avons vu l’apparition de l’ultra-libéralisme, qui s’est libéré de sa contrepartie allemande, et qui a donc entraîné cette promotion de l’avidité, de l’ « avoir-toujours-plus » qui s’est manifesté dans tous les domaines : la finance certes, mais aussi l’obscénité, avec, par exemple, aujourd’hui, l’emprise sans cesse plus grand de la pornographie.

Nous sommes alors entrés dans une autre culture, post-moderne, celle du capitalisme tardif. Et c’est ce moment que j’ai essayé d’analyser, comme temps d’une société qui consent, alors qu’elle ne l’avait jamais fait, ni dans les sociétés traditionnelles ni dans les sociétés occidentales, à la promotion du vice privé.

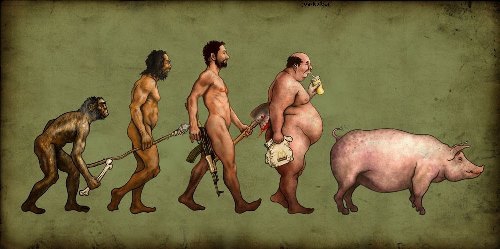

Pour bien comprendre ce tournant, il faut remonter à la crise de 1929. Avant 1929, le capitalisme était essentiellement un capitalisme de production. Or 1929 a été une crise de sur-production où plus rien ne se vendait, de sorte que tout s’est effondré, le système bancaire, le système économique – ce qui a entrainé des faillites et des problèmes sociaux en série, comme le chômage de masse. Mais, au lieu de mourir de sa belle mort, comme Marx l’avait prophétisé, le capitalisme a su profiter de cette crise majeure pour de se reconfigurer, en mobilisant les quelques réserves d’achat subsistantes, et devenir peu à peu un capitalisme de consommation, dirigé vers la satisfaction des appétences pulsionnelles du plus grand nombre avec la fourniture d’objets manufacturés, de services marchands, de fantasmes sur mesure proposés par les industries culturelles qui naissent à ce moment-là, offerts au plus grand nombre.

Cette société de consommation s’est véritablement mise en place aux États-Unis à partir de 1945 et est progressivement devenue un modèle pour le monde entier. Il se caractérise de flatter toutes les formes d’appétences relevant de ce que l’on appelait autrefois la concupiscence. Le puritanisme a alors été progressivement marginalisé comme quelque chose de rétro, de vieux, de ringard, au profit de cette révolution dans les mœurs, qui correspond au passage d’un capitalisme patriarcal, puritain, à un capitalisme libidinal, libéré, qui propose la plus grande gamme d’objets de satisfaction des appétences.

B : Port-Royal, la concupiscence et la fin des « grands récits »

AP : Vous donnez un rôle important à Pascal dans le tournant qui voit, au XVIIe siècle, la naissance de la pensée libérale. C’est selon vous chez lui que ce grand renversement s’opère, et vous rappelez en cela la distinction qu’il effectue au Fragment 458 des Pensées entre les trois concupiscences : la libido sentiendi, qui découle de la passion des sens et de la chair ; la libido dominandi, qui est la passion de posséder toujours plus et de dominer ; et la libido sciendi, qui concerne la passion du savoir. Cette distinction célèbre est une reprise du livre X des Confessions de Saint Augustin, s’étant lui-même inspiré de l’Épître de Jean. Or, vous montrez, par l’intermédiaire d’éléments biographiques, que Pascal a lui-même cédé à la libido dominandi. A partir de 1648, il fait des affaires avec le Duc de Roannez…

DRD : Oui, et c’est presque à son corps défendant, puisque le malheureux Pascal était très rigoriste. Mais c’était un immense penseur et il se reprochait – après tout ce qu’il a inventé dans le domaine du calcul, de la géométrie, de l’arithmétique, de la physique – d’être sujet à la libido sciendi. Il se punissait donc par toute une série de maladies, en tant que possédé par cette libido sciendi qui avait déjà été repérée dans l’Evangile de Jean, mise en exergue par Saint Augustin et qu’il a ensuite reprise dans le fragment que vous évoquez. Il se reprochait une tendance à la facilité libidinale qui méritaient des punitions corporelles. Pascal est presque un cas clinique : plus il pense, plus il va loin dans le domaine du renouvellement de la science – à l’époque encore prise dans la scolastique du Moyen Age -, plus il invente (calcul sur les coniques, la pression, le vide, sans oublier l’invention de la « pascaline », considérée aujourd’hui comme l’ancêtre de l’ordinateur…, le bilan scientifique est immense !), plus il devient moderne, et plus il se reproche de céder à la libido sciendi. J’ai repéré aussi un épisode, celui dits des « carrosses à cinq sols » où il cède à la libido dominandi. Pascal est quasiment mourant et, étrangement, il se lance dans une affaire extrêmement intéressante avec le soutien du Duc de Roannez, puisqu’il réussit à installer un système de transport en commun dans Paris en anticipant les points nécessaires de jonction et de changements. Il fabrique donc une sorte de métro de surface, avec toute l’intelligence nécessaire à sa conception. Il réussit fort bien dans cette entreprise, et plus il réussit, plus il va se le reprocher en accueillant des gens qu’on dirait aujourd’hui « marginaux », éventuellement porteurs de maladies contagieuses au point qu’il va se retrouver finalement contaminé, et finir par mourir alors qu’il n’a pas atteint sa quarantième année. Ce fut donc pour moi un cas clinique et philosophique très important, puisqu’il a ouvert quelque chose de neuf tout en pensant qu’il transgressait.

C’est probablement ce qui lui a fait dire (dans le fragment 106) que “La grandeur de l’homme, [c’est] d’avoir tiré de la concupiscence un si bel ordre”. Il aura là ouvert une voie ensuite reprise par Pierre Nicole, un des Messieurs de Port-Royal, qui, entre autres grandes questions philosophiques, s’est interrogé d’une façon complètement nouvelle sur l’idée de vertu. Qu’est-ce qui fait tenir un grand peuple dans la vertu ? Nicole s’aperçoit, à l’époque des grandes découvertes où d’autres formes civilisationnelles apparaissent, que la vertu des chrétiens n’est pas nécessairement indispensable au fonctionnement vertueux d’une Cité. Il reprend là une idée en vogue à l’époque et avance que ce qui pourrait remplacer cette vertu est un « amour-propre éclairé ».

Revient donc une nouvelle fois cette idée d’amour-propre, qui avait été complètement interdite depuis Augustin et les augustiniens. Il était pour eux la source de tous les maux. Et l’on aboutit chez Nicole, fils spirituel de Pascal, à la remise à l’honneur de cet amour de soi. Pascal aura donc, à son corps défendant, ouvert la voie pour que cette notion d’amour propre passe, de proche en proche, des jansénistes aux calvinistes, via Nicole, De Boisguilbert, puis Pierre Bayle.

Bayle, converti et reconverti plusieurs fois, va être un lecteur infatigable (en témoigne son fameux grand dictionnaire), notamment de Pierre Nicole qu’il qualifie de « plus grande plume d’Europe ». Et c’est là, arrivée chez les calvinistes, que cette notion d’amour de soi, avec les formes qu’elle pendra chez Mandeville, permettra de lancer, non seulement un laboratoire philosophique, mais aussi et surtout un laboratoire économique et social. C’est en effet cette autorisation donnée à l’amour de soi qui va mener à la première révolution industrielle en Angleterre et va, finalement, transformer le monde.

AP : Vous montrez que Pascal n’est pas sorti de cette douleur, de ce tiraillement, comme si la foi le quittait, comme s’il n’était pas capable de se « reprendre », en quelque sorte. Il demeure néanmoins toujours une place pour que le cœur de l’homme change, pour autant qu’il puisse se montrer capable de surmonter la délectation de la concupiscence par la charité. Mais plus généralement ce qui est intéressant dans votre livre, c’est que si vous constatez la fin des grands récits, en reprenant le terme de Jean-François Lyotard, vous ne les rejetez pas pour autant.

DRD : Absolument. Cela a été la suite de mon travail.

AP : Vous pensez même qu’il existe à notre époque ce que vous appelez une « inversion de la dette », qui touche l’éducation, le rapport à autrui, le rapport au sexe. Pouvez-vous préciser cette idée, cette constatation, qui semble transcender jusqu’aux clivages politiques, puisque tout se passe comme si aujourd’hui s’était substituée au clivage classique gauche-droite une opposition plus large entre libéraux et anti-libéraux, postmodernes et anti-modernes ?

DRD : Après la Cité Perverse, j’ai été amené à réfléchir sur cette sortie progressive des grands récits, même s’ils restent en quelque sorte en toile de fond, ainsi que sur ce libéralisme culturel tel qu’il a aussi été mis en place par la gauche, au sens d’une possibilité apparue à certains de se libérer de tout, de toute limite. Cela correspondait pour moi à une possibilité de revisiter les philosophies postmodernes promettant une libération totale, et qui, pour moi, sont apparues, trente ans après avoir été exprimées notamment par Deleuze, Foucault et quelques autres, comme une impasse peu viable car nous entraînant dans l’excès, la démesure, le dépassement permanent, la transgression permanente.

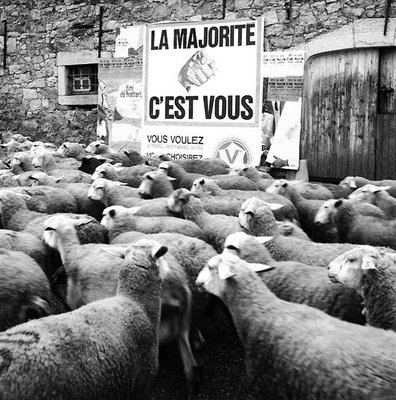

Cela m’a amené à m’interroger sur les philosophies postmodernes. J’ai traduit cela dans mon travail comme suit : les grands récits sont en passe d’être bousculés par la prolifération des petits récits de satisfaction pulsionnelle – car le capitalisme libidinal c’est cela, des petits récits de satisfaction, le modèle étant le récit publicitaire – et, paradoxalement, les philosophies postmodernes de gauche ont beaucoup contribué à la mise en place de cet ultra-libéralisme transgressif, selon lequel on peut se libérer de tout.

Or, étant freudien, je me souviens du Malaise dans la civilisation, selon lequel la civilisation n’est possible qu’à la condition de certaines répressions pulsionnelles. Si l’on permet tout, on va vers le délitement civilisationnel. Donc, certaines répressions sont nécessaires. Par exemple, dans le freudisme, c’est la limite qui est posée à la pulsion, notamment à la pulsion incestueuse de l’enfant, qui, finalement, permet l’accès au désir. En d’autres termes, il faut sortir du rapport fusionnel avec la mère, pour que l’accès à d’autres soit possible. Cela procède d’une répression pulsionnelle.

Et il y a bien d’autres répressions pulsionnelles : devoir en passer par le discours, le langage, ne pas prendre directement les objets dans les endroits où l’on se trouve, entretenir des formes civilisées passant par le discours pour demander si l’on peut faire ceci ou cela. Même dans les démarches amoureuses, on fait des manœuvres d’approche, on parle. Dans les communautés humaines, nous sommes tenus à une certaine dignité par l’habit, on ne montre pas son fonctionnement pulsionnel de manière évidente. Nous sommes donc retenus pulsionnellement. Et tout cela fait partie de la civilisation. Nous mangeons avec des fourchettes, nous ne saisissons pas les aliments avec les mains. Il y a donc toute une série de règles civilisationnelles qui imposent une répression pulsionnelle.

Cela m’a amené à m’interroger sur les commandements contenus dans les grands récits : « Tu ne dois pas » faire ceci ou cela. Il y a même un Décalogue qui dit clairement ce que l’on ne doit pas faire. Cela m’a donc amené à m’interroger sur ce dont on pouvait se débarrasser, comme répressions supplémentaires, additionnelles, impropres en quelque sorte, imposant une répression surnuméraire, et sur ce qu’il fallait conserver comme étant nécessaire au fonctionnement civilisationnel. J’ai donc écrit ce livre, L’Individu qui vient… après le libéralisme dans lequel j’examine ce dont il faut se débarrasser et ce qu’il faut conserver dans les deux grands récits fondateurs de l’Occident. Le premier étant celui du Logos des Grecs, le second étant celui du monothéisme venu de Jérusalem et refondé à Rome. J’ai donc été amené à examiner de façon précise ce que ces grands récits posaient comme répressions nécessaires au fonctionnement du lien social, et ce dans quoi ils allaient trop loin, en instituant des répressions additionnelles, ce que Marcuse appelait des sur-répressions. Je pense, par exemple, que dans le récit monothéiste, nous pouvons nous débarrasser du patriarcat. On peut et même on doit se débarrasser de l’oppression qu’il contient à l’encontre des femmes, sans remettre en question la primauté du rapport à l’autre sur le rapport à soi.

Dany Robert Dufour invité de l’émission “Question de sens” sur France Culture

C : Adam Smith et Sade : puritanisme et perversion

A.P : Pour en revenir à Adam Smith le puritain, vous écrivez que s’il fait reposer en une instance extérieure à la conscience (le fameux « spectateur impartial ») la loi fondamentale de l’économie, c’est pour permettre au capitaliste de se soumettre à cette voix et accroître sa libido dominandi. D’où la fascination de générations entières de penseurs libéraux pour la main invisible. Or, vous expliquez que la voix du spectateur impartial s’adresse en réalité… aux pauvres ! Et vous citez un passage peu commenté de la Théorie des Sentiments Moraux où il écrit : « Le pauvre ne doit jamais ni voler, ni tromper le riche […] La conscience du pauvre lui rappelle dans cette circonstance qu’il ne vaut pas mieux qu’un autre et que, par l’injuste préférence qu’il donne, il se rend l’objet du mépris et du ressentiment de ses semblables comme aussi des châtiments qui le suivent puisqu’il a violé ces lois sacrées d’où dépendent la tranquillité et la paix en société. » Le pauvre porte ainsi sur ses frêles épaules une énorme responsabilité : celle de devoir modérer ses appétits, pour le bien de tous. N’est-on pas, de nos jours, parvenus à un paroxysme de cette idée, lorsque le « pauvre » est affublé de tous les maux, comme celui de creuser les dettes par ses dépenses inconsidérées en matière de santé publique, de trop réclamer d’aides sociales au moment où près de dix millions de personnes, rien qu’en France, vivent en-dessous du seuil de pauvreté, et qu’apparaissent des travailleurs pauvres ? L’association bien connue ATQ-Quart Monde a publié en 2013 un petit opuscule intitulé En finir avec les idées fausses sur les pauvres et la pauvreté, lequel dresse une large liste des idées reçues sur la pauvreté, avec force chiffres issus de sources officielles. Le résultat est simple : on se demande ce que l’on cherche à cacher, ce que l’on parvient à cacher derrière ces accusations. Selon vous, une prise de conscience collective est-elle possible ou sommes-nous condamnés à demeurer dans une société qui véhicule ce type de préjugés ?

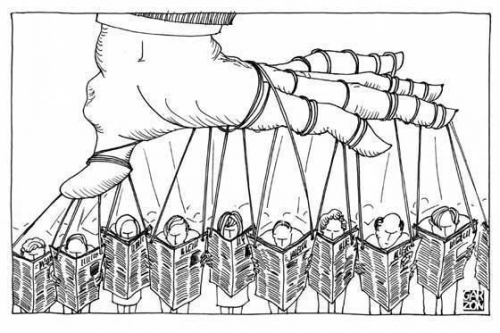

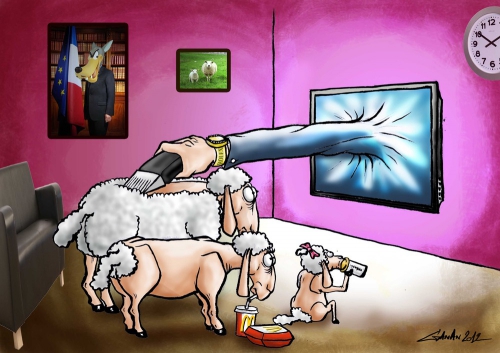

DRD : J’espère que l’on pourra s’en libérer. Mais pour ce faire, il faut qu’il existe des instances de délibération, de discussion, or, est-ce que nos sociétés fonctionnent avec ces instances ? ce n’est pas sûr. Même si l’information est large, elle relaie souvent des idées toutes faites. Le problème est celui du discours démocratique, qui me semble menacé par la puissance des industries culturelles, médiatiques, qui modèlent l’opinion publique dans le sens de la production de ses idées fausses, qui font toujours recette. Ce qui peut avoir des conséquences dramatiques, avec l’apparition d’un certain nombre de phénomènes politiques dangereux. Je ne sais pas ce que l’avenir politique nous réserve, nous avons vécu des heures sombres, personne ne peut dire qu’il est impossible de les revivre.

AP : Vous accordez, dans votre réflexion, une place très importante à Sade. Ses écrits ont pour vous une portée hautement philosophique, vous écrivez même que Si Marx avait lu Sade, « Nous n’aurions pas eu cette division hautement dommageable entre Marx d’un côté pour l’économie des biens et Freud de l’autre pour l’économie libidinale […] nous aurions pu disposer d’une économie générale des passions […] Nous aurions évité la captation et le fourvoiement des esprits rétifs à la théodicée smithienne dans ces fausses alternatives au capitalisme que furent les économies socialistes, qui ne pouvaient conduire qu’au plus lamentable des fiascos. » D’abord, vous ne ménagez personne, et ensuite, peut-on dire que l’on trouve exprimée là le cœur même de votre pensée politique, qui se situerait à la confluence d’un marxisme et d’un freudisme attentifs aux conséquences d’un monde pulsionnel profondément désymbolisé, dont Sade aurait en quelque sorte eu la prescience ?

DRD : Oui, Sade est véritablement l’ange noir du libéralisme. C’est celui qui dit en quelque sorte : « Vous voulez mettre au premier plan l’amour de soi ? Vous voulez mettre au premier plan l’égoïsme ? Et bien allons-y. » Et il construit donc toute une série d’utopies, ou plutôt de dys-topies, dans lesquelles il montre un monde qui serait entièrement régi par l’égoïsme, c’est-à-dire par un fonctionnement purement pulsionnel. Et dans cette mesure, oui, je fais grand cas de Sade. Ce n’est pas que j’aime lire Sade, car – tous les grands lecteurs de Sade, de Bataille à Annie Lebrun, l’ont signalé – sa lecture rend malade, mais il a mis le doigt sur quelque chose d’important : si vous mettez l’égoïsme au premier plan, voilà ce que cela donne. Et c’est insupportable – relisez pour vous en convaincre Les Cent Vingt Journées de Sodome ou revoyez le film qu’en a tiré Pasolini. On ne peut donc pas fonctionner que sur le plan pulsionnel.

C’est pour cela que je trouve important de voir le capitalisme comme quelque chose qui, à partir d’un certain moment, en 1929 – ce que j’appelle le « retour de Sade » – s’est de plus en plus mis à fonctionner sur un plan purement pulsionnel. C’est ainsi qu’il faut faire une analyse de la manière dont les pulsions fonctionnent, car elles reconfigurent le monde lorsqu’on les laisse aller à leurs fins : la mise au premier plan de l’avidité, notamment dans le monde de la finance, ou de l’obscénité dans la culture post-moderne, etc. Il faut, je crois, s’interroger sur le devenir de notre monde s’il devient entièrement pulsionnel. En ce sens, je prends Sade comme celui qui permet de construire une mise en garde, plutôt que comme quelqu’un qui exalte ce fonctionnement pulsionnel.

D : Les manifestations modernes de la servitude volontaire dans la Cité perverse

AP. : Vous rappeliez tout à l’heure l’importance du « moment » Reagan-Thatcher dans les années 80. Dans le deuxième chapitre de votre Cité Perverse, vous écrivez : « La révolution passive du capitalisme accoucha [...] de ces jeunes ambitieux cyniques, obsédés par l’argent et la réussite. Soit ceux-là mêmes qui ont pris, à partir des années 1980, la direction du monde. » Vous décrivez là les jeunes générations qui usèrent comme d’un leitmotiv du « greed is good » de la longue tirade prononcée par Gordon Gecko alias Michael Douglas, dans le film « Wall Street » d’Oliver Stone sorti en 1987 qui devint, à son corps défendant, un film culte pour toute cette génération avide d’argent facilement et rapidement gagné. Vous dites par ailleurs qu’aux Etats-Unis, quelqu’un a joué un rôle très important : Edward Bernays, le neveu de Freud…

DRD : Bernays est un personnage très important, il a été reconnu par le magazine Times comme une des cent personnalités les plus importantes du XXème siècle, et il a contribué à créer ce que l’on appelle aux Etats-Unis les public relations. Cela a à voir avec le marketing : il ne faut pas oublier que son premier livre s’appelle Propagande, au sens littéral du terme, soit comment manipuler l’opinion des gens. Il a eu pour lecteur et admirateur Joseph Goebbels…

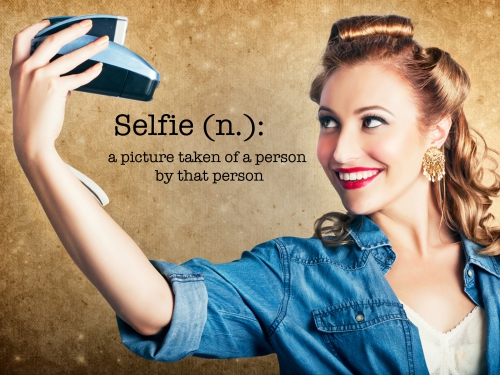

Il a expliqué comment manipuler les désirs des individus, afin de leur donner, par le marché, un certain nombre de satisfactions en rapport à des désirs cachés. Il a permis de mettre en adéquation les désirs supposés des individus et des produits correspondants.

Je raconte, par exemple, l’épisode qui me semble inaugural et qui se passe en 1929 : la façon dont les femmes ont cru, à la suite de certaines mises en scène de Bernays, pouvoir se libérer… en fumant. Comment ? Tout simplement en prenant le petit objet phallique qui était à disposition des hommes seulement – les femmes qui fumaient étant alors considérées comme dévergondées-, elles ont été amenées à penser se libérer de l’oppression masculine en se mettant à fumer à leur tour. C’est ainsi qu’une opinion peut être manipulée, pour mettre en face d’un supposé désir, l’objet manufacturé, qui peut prétendument le satisfaire. Nous avons affaire aujourd’hui à un marketing généralisé, qui utilise la psychologie profonde, la psychanalyse comme le neveu de Freud savait le faire, mais qui utilise aussi la philosophie.

Par exemple, la philosophie deleuzienne a été exploitée d’une façon incroyable avec la reprise par la publicité de l’idée de nomadisme. Soyez nomades, ne dépendez plus de personne, déplacez-vous quand vous le voulez, ayez votre téléphone et vos produits nomades et vous serez complètement libres. Achetez les produits nomades pour ne plus dépendre de personne. Moyennant quoi les gens sont aujourd’hui accrochés à leur portable, doivent travailler en dehors de leurs heures de travail, car ils sont continuellement branchés. C’est aussi une des formes de la manipulation, où, en face d’un supposé désir de nomadisme, c’est-à-dire de sortie des groupes, des clans, de la famille, des communautés, l’on m’offre à acheter des produits qui permettent de faire de moi un vrai nomade, c’est-à-dire quelqu’un qui est continuellement branché. Drôle de nomade, en fait.

On met aussi aujourd’hui à profit la neuro-économie, dans la prise de décision d’achat, avec dans l’entourage de tout ce que l’on veut vendre, toute une série de sons, de couleurs, de musiques, supposés euphorisants, suggérant le bonheur, la liberté, et qui ainsi associés au produit, ont pour effet de précipiter la décision d’achat. Ainsi pour être libres, on s’aliène avec le produit. Tous ces mécanismes mettent en lumière un psycho-pouvoir. Nous pensons être libres mais c’est uniquement à la condition de s’aliéner immédiatement à la cigarette, aux produits qui nous poursuivent jour et nuit, comme le portable qui permet aux autres de suivre nos mouvements, nous déranger pendant les heures de repos.

AP : Ce qui est très étonnant c’est que, tout à coup, l’homme consent à son propre esclavage…

DRD : Exactement, c’est une nouvelle forme de servitude volontaire. C’était le sous-titre d’un de mes livres : la servitude volontaire à l’époque du capitalisme total [2].

AP : D’où vient cette fragilité de l’homme ? Est-ce que cela vient de ce que vous appelez dans un autre ouvrage sa néoténie ?

DRD : Oui je pense qu’il faut évoquer ici la néoténie qui permet de comprendre que nous ne sommes pas finalisés pour occuper une place définie dans la hiérarchie des espèces, puisque nous naissons inachevés à la naissance. À la différence des animaux, nous n’avons pas d’instinct nous amenant à occuper une place particulière ; nous avons des pulsions, qui veulent tout et n’importe quoi. Cela crée une très grande débilité, au sens fort du terme, celui de faiblesse, de fragilité. Nous ne sommes pas fixés dans un monde qui est naturel, nous participons à un autre monde qui est celui du langage, de la culture, dans lequel les significations sont extrêmement mouvantes, sujettes à fluctuations et manipulations. C’est notre fragilité fondamentale. Mais cette fragilité est aussi la beauté de l’homme, cela le sort du règne animal, et lui permet de chercher sa voie, sa route.

C’est au fond par là qu’a commencé la Renaissance, avec le fameux « discours de la dignité humaine » de Pic de la Mirandole : vous n’êtes pas finalisés pour être ici plutôt qu’ailleurs, c’est donc que vous devez vous achever vous-mêmes. C’est une très belle mission, car c’est la part de liberté que Dieu, s’il existe, nous laisse. Pour une part, vous êtes formatés, mais pour une autre, c’est à vous de vous créer, pour le meilleur et pour le pire.

AP : La tentation de la sortie de la réflexion personnelle et du silence n’a jamais été aussi forte qu’aujourd’hui. L’homme est fondamentalement fragile mais il l’est rendu encore plus par une société pulsionnelle tentatrice…

DRD : Oui, elle pourvoit à tout, à toute pulsion, à toute passion. Ce que vous voulez, on vous le donne. Il n’y a plus de place pour ce que l’on appelait auparavant le retrait, toutes les expériences philosophiques de réforme de l’entendement par le retrait, se retirer du monde, penser par soi-même, etc. Nous sommes aujourd’hui constamment sollicités. Je milite beaucoup pour la reconstitution de cette capacité de retrait par rapport au monde : avoir un temps de pensée personnelle. Je rejoins, par exemple, des auteurs comme Pascal Quignard qui lui aussi recommande certaines formes de retrait. Ne pas être le battant performant que l’on exige que je sois. Ce temps hors monde me semble un temps important pour l’édification de soi.

AP : Il est donc pour vous encore temps de faire primer le fonctionnement symbolique sur le fonctionnement pulsionnel ?

DRD : Je l’espère bien ! Même si cela devient difficile. Nous sommes tout le temps immédiatement embarqués dans un fonctionnement pulsionnel marchand. Le retrait pour un fonctionnement symbolique n’est donc pas gagné d’avance.

E : Le programme du Conseil National de la Résistance

AP : En 1943, la philosophe Simone Weil a rejoint la France Libre, sur recommandation de son ami Maurice Schumann, où elle est devenue rédactrice. Elle y rédigea un rapport plus tard publié par Albert Camus chez Gallimard qui s’appelle L’Enracinement. Ses propositions ont été, pour certaines, reprises dans le programme du Conseil National de la résistance (CNR), et vous en parlez dans votre dernier ouvrage, L’individu qui vient. Pouvez-vous nous parler de ces propositions et recommandations et nous dire pourquoi elles retiennent tant votre attention. N’est-ce pas dommage qu’elles n’aient jamais été suivies ?

DRD : De celles qui ont été mises en place hier, on essaie de sortir à toute force aujourd’hui. La décision de la publication de ce programme, Les Jours Heureux, se prend dans la clandestinité, en 1944. La question qui se pose est : comment refonder un monde sur le principe de dignité ? C’est un programme qui fut fondé non sur l’égoïsme de l’ultra-libéralisme des années vingt aux Etats-Unis qui à mené à la crise de 1929, laquelle a entrainé l’émergence du nazisme en Allemagne, où les foules se sont mises en recherche de l’homme providentiel désignant des boucs émissaires. La question qui se pose à ceux qui sont engagés dans la Résistance est donc celle de la reconstruction d’un monde sur le principe de dignité, et ils vont prendre toute une série de mesures politiques, par exemple le droit de vote accordé aux femmes. Il a fallu attendre 1945 en France pour s’aviser que les femmes étaient aussi capables de pouvoir penser par elles-mêmes et donc bénéficier du droit de vote. Ce sont aussi des principes économiques, l’intérêt collectif primant sur les intérêts individuels dans la grande industrie, dans la banque, la finance. C’est la liberté de conscience, la liberté de presse, le droit à l’éducation, la santé, au travail, à une protection sociale. Or, ces grandes mesures sont, depuis quelques années, remises en question, accusées d’empêcher la compétitivité de la France. Il faudrait détruire tout cela pour en revenir à un ultra-libéralisme équivalent à celui des années vingt, qui fait la toile de fond du grand roman de Francis Scott Fitzgerald, Gatsby le Magnifique, lequel a récemment fait l’objet d’une belle adaptation cinématographique par Baz Luhrmann. Ce n’est un hasard si l’histoire est racontée par un employé de Wall Street, qui constate la folie, la démesure propres à l’ultra-libéralisme, qui renvoient au film dont vous parliez, Wall Street d’Oliver Stone.

L’ultra-libéralisme qui triomphe à partir de 1980 reprend en quelque sorte les idées des années vingt et ne peut que s’en prendre à ce qui a été mis en place après 1945. Désormais, le programme du CNR est désigné comme étant ce dont il faut se débarrasser, dans le but de détruire tout ce qui a été édifié à cette époque-là par cette alliance entre les résistants de tous bords que le gaullisme a su fédérer.

AP : Et celle alliance se fait, par nécessité, au-delà des antagonismes idéologiques, en dehors des partis. Et Simone Weil a écrit un petit opuscule, à ce sujet, intitulé Sur l’interdiction des partis politiques. N’est-on pas aujourd’hui confrontés, plus qu’à la crise d’une idéologie, à une crise de la démocratie elle-même ?

DRD : Une crise politique, bien sûr. L’opposition gauche-droite ne signifie plus grand-chose. Nous avons besoin d’autres expressions politiques.

AP : On constate d’ailleurs l’apparition d’une gauche que ses contempteurs nomment « réactionnaire », repérable dans les travaux, notamment, de Jean-Claude Michéa.

DRD : Je connais Jean-Claude Michéa et je crois pouvoir dire que nous nous apprécions mutuellement, et je suis considéré comme lui comme un néo-réactionnaire. J’analyse le capitalisme ultra-libéral dans son fonctionnement actuel et on me dit néo-réactionnaire, ce qui est tout de même un comble.

F : Sur la négation de la « sexuation » : un effet de la pensée permissive

AP : Pour ne rien arranger, vous abordez notamment la question de la négation de la sexuation dans nos sociétés postmodernes, qui vous amène à faire une critique de fond du transsexualisme. On vous reproche en conséquence d’être contre les transsexuels, ce qui est évidemment pas le cas, mais vous expliquez que c’est un exemple – et vous faites grand cas des exemples, des faits, puisque vous distinguez entre le fait divers et le fait de structure – ce qui rend votre lecture intéressante, vivifiante et passionnante, car le lecteur voyage dans la philosophie ainsi que, au travers des faits de structure, dans le monde tel qu’il se présente à nous.

DRD : Les concepts philosophiques sont pour moi des moyens d’appréhender des éléments et évènements du monde dans lequel nous vivons. Je ne me situe pas dans le monde pur des idées, les concepts sont pour moi des moyens de comprendre et d’entrer dans le monde. Le transsexualisme est à ce titre un symptôme de notre monde. Il doit être analysé avec des concepts philosophiques et psychanalytiques mettant en jeu de grandes questions telles que la constitution et la survie de notre espèce en tant que sexuée. Cette différence sexuelle partie du réel avec lequel nous devons nous accommoder. Nous sommes vivants et donc homme ou femme. Mais nous sommes aussi parlants et il se peut que quelque chose en nous objecte à ce que nous soyons tombés de tel ou tel côté de la sexuation. Je veux dire qu’une femme peut se sentir plus homme que femme ou l’inverse, et je n’ai rien à redire à cela. Rien n’interdit de fantasmer, de se fantasmer autre que ce que nous sommes. Mais à partir du moment où l’on veut devenir vraiment une femme alors que l’on est un homme, ou l’inverse, je pense qu’il y a là une limite à signifier au fantasme. En effet, ce n’est pas parce que je me pense femme si je suis homme, ou l’inverse, que je peux vraiment le devenir. Je peux me travestir et cela fait partie des droits de l’homme. Ainsi porter des vêtements de femme si je suis un homme est une chose, mais passer d’un corps d’homme à un corps de femme en est une autre, car c’est de toute façon impossible. Je pourrais bien faire couper ou ajouter ce que je veux, j’aurai toujours en moi le gêne SRY de la détermination sexuelle qui me désignera à jamais comme mâle ou femelle.

Or, il y a aujourd’hui toute une industrie médicale et chirurgicale qui promet le changement de sexe, ce qui est un mensonge. On peut changer d’apparence, de look, mais pas de sexe.

Du coup, cela m’oblige à prendre position dans le débat sur la PMA et la GPA. Je ne suis pas opposé à ce que des homosexuels adoptent des enfants, car de nombreux enfants ont été recueillis et élevés par des voisins, des oncles ou (sans mauvais jeu de mots) des tantes, et rien ne permet de penser que les homosexuels seraient de plus mauvais parents que bon nombre d’hétérosexuels. Mais on doit veiller à ce que l’enfant ne puisse pas se penser comme fils ou fille de parents adoptifs homosexuels. Ce serait, à ce moment-là, introduire en lui l’idée qu’il aurait échappé à la division sexuelle. C’est pour cela que dans un article du Monde j’ai milité pour qu’on distingue, dans l’identité, deux niveaux juridiques : celui de la procréation (qui sont les parents réels, les géniteurs), et celui de la filiation (qui sont les parents subrogés, ceux qui éduquent l’enfant).

Un enfant doit en effet toujours savoir qu’il est né d’un homme et d’une femme, même s’il est élevé par des homosexuels. Sans cette obligation, il ne peut y avoir que des catastrophes provoquées par un déni de réel, comme penser qu’on est l’enfant de deux hommes ou de deux femmes.

AP : Il y a un certain nombre de dérives, notamment aux Etats-Unis, où l’on féconde in vitro des enfants pour des couples, et où des sociétés proposent presque de choisir son enfant, comme on choisit une voiture, sur catalogue. Le processus de procréation est ainsi nié, et l’enfant n’est que le fruit d’une manipulation biologique.

DRD : La technique doit être ici interrogée. Certaines techniques permettent aujourd’hui la réalisation, le passage au réel du fantasme. Elles mettent en question le réel sur lequel nous sommes anthropologiquement fondés.

G : Le dépassement de la structure binaire du structuralisme (de Lévi-Strauss à Blanchot)

AP : J’aimerais revenir sur l’importance que vous donnez à la littérature, et notamment à Blanchot, que vous appelez comme « Le grand lecteur du XXème siècle », et ce dès Faux pas et La Part du Feu. Il a inspiré des philosophes-écrivains comme Barthes, Derrida, Foucault, qui font se rencontrer littérature et philosophie. Il fut l’inventeur de « formes rhétoriques saisissantes », écrivez-vous, résultat du maniement très adroit de la figure unaire, « qui permet l’échange de tout en rien, de rien en tout, de l’absence en présence… ». Blanchot demeure selon vous une figure tutélaire invisible. Cette forme unaire fait l’objet de votre premier ouvrage Le Bégaiement des maîtres : Lacan, Émile Benveniste, Lévi-Strauss [3] publié en 1988, dans lequel vous reveniez sur l’enseignement des maîtres du structuralisme. Pouvez-vous préciser ce que vous entendiez par la « structure unaire » de l’énonciation et à quoi celle-ci s’oppose ?

DRD : J’ai commencé mon travail de philosophe en essayant de sortir de la logique binaire du structuralisme, qui était contemporain, par Lévi-Strauss par exemple, de la naissance de la cybernétique. Ce n’est pas un hasard s’il a écrit Le cru et le cuit qui est devenu le premier tome des Mythologiques : ce titre évoque une opposition binaire. Et, de fait, Lévi-Strauss analyse les structures de parenté ou le fonctionnement du mythe à l’aide de ces structures binaires. Cela m’est apparu et m’apparaît toujours comme extrêmement important, mais très réducteur, car c’est oublier qu’il y a d’autres types de structures, comme la structure trinitaire (c’est pour cela que mon deuxième livre s’appelait Les Mystères de la Trinité, dans lequel j’ai travaillé sur les formes trinitaires dans l’inconscient, le récit et l’énonciation), et la forme unaire. Un exemple fameux de forme unaire est la parole biblique : « je suis celui qui suis ». Ehièh Ascher Ehièh. Ce qui permet l’auto-fondation de Dieu. A partir d’un moment, cela n’a plus été réservé à Dieu, si je puis dire. Ce n’est pas un hasard si, à partir de 1946, après guerre donc, Benveniste et Jakobson ont affecté cette formule désignant le Grand Sujet aux petits sujets. Comme si Dieu, du fait des exactions des hommes, était mort et que les petits sujets ne pouvaient plus désormais compter que sur eux-mêmes pour se fonder. Cela a donc mis à l’ordre du jour une autre structure, qui est la structure unaire, le « Je qui dis Je » dans laquelle le prédicat et le sujet sont le même. C’est ma lecture de Blanchot qui m’a guidé sur ces structures unaires, il m’a fait sortir de l’emprise binaire totale qu’avait à un moment donné le structuralisme. Même si je ne récuse pas l’idée qu’il existe des structures binaires, je persiste à croire qu’il existe aussi des structures trinitaires et unaires qui sont particulièrement en jeu dans les domaines révélés par les écrits bibliques, la grande littérature. On doit pouvoir les remettre à l’ordre du jour pour penser des phénomènes importants dans le champ de la subjectivation et dans le champ du rapport à l’autre, c’est-à-dire dans les domaines de l’être-soi et de l’être-ensemble. Par exemple : nous ne sommes jamais deux lorsque nous parlons, mais toujours trois. Car quand je parle, « je » parle à un « tu » à propos de « il », lequel renvoie à ce dont nous parlons. Dès que nous ouvrons la bouche pour dire « je », nous sommes donc spontanément trois. Dans le dialogue, nous sommes trois. Mes travaux s’initient à partir de cette sortie du structuralisme pur et dur, qui m’avait beaucoup influencé quand j’étais jeune, et cela m’a contraint à aller rechercher ces autres structures ailleurs : dans le récit biblique et dans la grande littérature, notamment celle de Blanchot ou de Beckett.

H : Le libéralisme anti-utilitariste (Constant, Tocqueville) et le kantisme

AP. : On aura compris que vous critiquez le libéralisme (en réalité plutôt l’ultra-libéralisme) et en particulier la pensée d’Adam Smith et l’influence très forte qu’il a eu sur l’émergence d’une société fondamentalement perverse. Mais il existe un libéralisme français et anti-utilitariste chez Benjamin Constant et Alexis de Tocqueville. Pourquoi ne pas en parler, puisqu’il permettrait peut-être de montrer que plus qu’une crise du libéralisme, il s’agit d’une déviance d’un certain libéralisme, au sein de ce qui serait en réalité une crise de la démocratie ?

DRD : Je ne critique pas le libéralisme politique qui est selon moi une nécessité et une évidence, ce qui m’inquiète c’est le libéralisme économique, ultra, qui étouffe même le libéralisme politique. Il est vrai que je parle peu du libéralisme de Constant et Tocqueville, cela reste quelque part dans ma tête, car je me sens en accord avec ce libéralisme politique, et je le sens même menacé par le libéralisme économique qui prévaut à l’heure actuelle. J’espère avoir le temps d’en repasser par ces auteurs.

AP. : Vous opposez Sade à Kant, pour des raisons qui sembleront évidentes. Vous écrivez même dans le deuxième chapitre de la Cité Perverse que La Religion dans les limites de la simple raison a paru la même année que La philosophie dans le boudoir, en 1795. Nous notez que dans son livre Kant semble parler du cas Sade, lorsqu’il évoque « celui qui a choisi l’égoïsme, l’amour inconditionnel de soi », rappelant ainsi la figure du « scélérat » chez Sade. Or il apparaît toujours compliqué de savoir ce que Kant entend par « raison pratique ». Constant fait apparaître, dans la querelle qui les oppose à propos du mensonge, quelque chose d’assez effrayant chez Kant, et qui est en quelque sorte l’anti-humanisme de sa morale. On se souvient de la phrase de la Doctrine du Droit : « La politique doit plier le genou devant la morale. » Cela mènera plus tard, peut-être, à une raison fondamentalement technocratique que l’on retrouve chez Habermas dans sa théorie de l’agir communicationnel. Habermas grand défenseur de l’Europe, elle-même monstre technocratique par excellence…

DRD : J’ai été amené à travailler sur la querelle entre Benjamin Constant et Kant par Jean-Claude Michéa qui me faisait la même objection : en suivant sa loi morale, Kant aurait pu dénoncer des résistants à la police vichyste. En fait, je pense que c’est plus compliqué que cela. Vous savez que Kant a écrit un essai sur le mal absolu, et je crois qu’il n’a pas eu le temps d’en écrire un autre sur le mal relatif. C’est donc à nous de l’écrire. S’il l’avait écrit, il aurait résolu autrement sa querelle avec Constant (d’ailleurs au moment de celle-ci, il ne se souvenait plus très bien de quoi Constant parlait). Il aurait convenu qu’il faut parfois mentir pour sauvegarder une forme de loi puisque celle-ci n’est pas nécessairement incarnée dans un pouvoir politique. Il faut ici, je crois, distinguer entre pouvoir et autorité. Celui qui a le pouvoir ne dispose pas nécessairement de l’autorité qui, seule, est conférée par la loi. Or, la loi renvoie à ce qui est supérieur à toute forme de représentation par des individus qui occupent des fonctions de pouvoir. Kant aurait donc pu écrire un essai sur le mal relatif, dans lequel il aurait fini par dire qu’il ne faut absolument pas dénoncer ses voisins à un pouvoir venant frapper à la porte, parce que ceux qui s’en réclament ont peut-être, plus que d’autres, désobéi, pour conquérir le pouvoir, à cette loi supérieure. On ne peut donc pas régler le sort de Kant en affirmant qu’il fait allégeance au pouvoir, sauf à aller dans le sens d’un formalisme comme celui d’Habermas, ou pire, dans le sens de ceux qui disent que Kant a anticipé le nazisme, ce qui est un contresens philosophique total, malheureusement commis par quelques philosophes, comme Onfray.

I : Philippe Muray. L’Europe

AP : Une dernière question. Que représente pour vous la transformation de la contestation du monde marchand ? N’a-t-elle pas fini par devenir acceptation, pire, participation à celui-ci, qui semblait pourtant être une des raisons de la colère de la jeunesse bourgeoise de mai 68 ? Le cas Cohn-Bendit semble à cet égard tout à fait significatif : membre du Parlement européen pendant plus de vingt ans, partisan d’une Europe fédérale, donc destructrice des Etats-Nations pourtant fondements de la citoyenneté européenne, il a toujours soutenu une organisation politique dont la structure est fondamentalement technocratique. Au fond, tout se passe comme si les libertaires de Mai 68 s’étaient formidablement retrouvés dans le libéralisme libertaire permissif, qui semble vouloir en finir avec l’homme, passer à une civilisation post-humaine dans une Europe branchée, férue d’art contemporain insignifiant ou de fêtes incessantes, que fustigeait un écrivain que vous citez beaucoup et dont vous saluez le talent : Philippe Muray. « L’Occident s’achève en bermuda », écrivait-il. Pour lui, la postmodernité montre une réelle « régression anthropologique », du point de vue de l’art, de l’éducation, des loisirs, du rapport à l’histoire, aux différentes pratiques humaines…

DRD : Tout d’abord, un mot sur Philippe Muray. Il est évident que c’est une délectation de le lire, tant c’est un homme libre, qui n’appartient pas au carcan de la gauche hédoniste transgressive dont nous parlions, et qui analyse tous les effets réactionnaires de la transgression, justement. Il pense le monde vers lequel cela peut nous amener. On l’a classé à droite, mais il peut à mon avis aussi bien être classé à gauche, voire à l’extrême-gauche. D’ailleurs il vient de ce monde, il a été soixante-huitard sans le renier. C’est un analyste merveilleux, un homme qui n’est pas embarrassé par toutes les formes prégnantes du libéralisme de gauche, de son politiquement correct, il y va donc de bon cœur, et le lire est tout à fait revigorant.

Ensuite, sur la forme que pourrait avoir une Europe. Il est évident le capitalisme marchand et financier ne peut pas souffrir la conservation des Etats, puisqu’ils sont ce qui ne peut que freiner la circulation toujours élargie de la marchandise, en imposant des règlements sanitaires, le droit du travail, ou des formes de régulations économiques et financières.

Donc, la visée de ce capitalisme marchand et financier est clairement la destruction des Etats. Maintenant, faut-il se diriger vers des formes de souverainisme à l’ancienne ? Je ne crois pas. Car les États n’ont plus la force de s’opposer aux flux marchands, et peuvent être contournés très facilement. La solution serait peut-être de mettre en sourdine leurs différences, qui ont amené à tant de guerres en Europe, et de mettre ensemble ce que les Etats-Nations européens ont en commun, sous la forme, par exemple, d’une fédération qui pourrait alors avoir la force suffisante pour réguler les flux marchands et financiers.

__________________________________________________

Notes :

[1] Dany-Robert Dufour, La Cité perverse. Libéralisme et pornographie, Gallimard, coll. Folio, 2012

[2] cf. Dany-Robert Dufour, L’art de réduire les têtes. Sur la nouvelle servitude de l’homme libéré à l’ère du capitalisme total, Denoël, 2003

[3] Dany-Robert Dufour : Le bégaiement des maîtres : Lacan, Emile Benvéniste, Lévi-Strauss, 1988, Bourin, 1994

C’est en quelque sorte, la fabrication des Marines américains transposée à la société civile. Pour fabriquer un Marine, il faut briser l’homme, l’être humain qui est en lui: qu’il ne soit plus que « Yes Sir ». Il faut « mater » ce qui résiste, ce résidu de liberté. Ou sans être trop grandiloquent, ce résidu de libre choix. Nous ne sommes même plus dans des techniques, des conditionnements, nous sommes dans l’intrusion, la prise de possession de l’individu. Car ce qui nous constitue essentiellement, c'est ce qui nous échappe, nous tyrannise, c'est notre inconscient.

C’est en quelque sorte, la fabrication des Marines américains transposée à la société civile. Pour fabriquer un Marine, il faut briser l’homme, l’être humain qui est en lui: qu’il ne soit plus que « Yes Sir ». Il faut « mater » ce qui résiste, ce résidu de liberté. Ou sans être trop grandiloquent, ce résidu de libre choix. Nous ne sommes même plus dans des techniques, des conditionnements, nous sommes dans l’intrusion, la prise de possession de l’individu. Car ce qui nous constitue essentiellement, c'est ce qui nous échappe, nous tyrannise, c'est notre inconscient.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

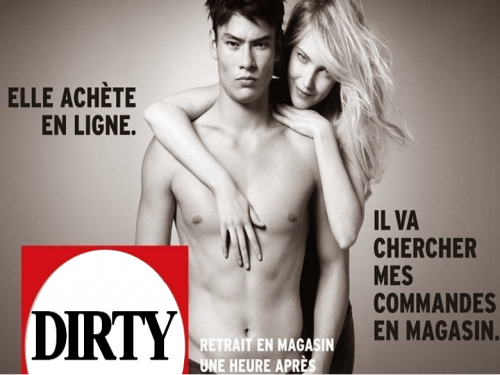

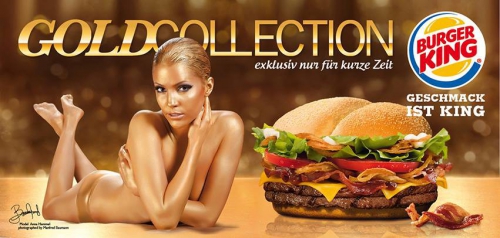

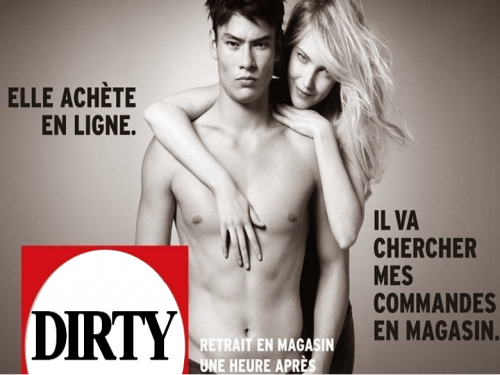

A partir de l’affiche Panzani, à travers sa simplicité, Roland Barthes découvrait la richesse d’une sémiologie. Que déchiffrerait-il dans la « communication » publicitaire tellement plus envahissante et prétentieuse d’aujourd’hui ?

A partir de l’affiche Panzani, à travers sa simplicité, Roland Barthes découvrait la richesse d’une sémiologie. Que déchiffrerait-il dans la « communication » publicitaire tellement plus envahissante et prétentieuse d’aujourd’hui ?

Un simple coup d'œil sur les forces en présence sur la plage de Marathon donne les Perses très largement gagnants. Comme on sait, ce fut le contraire. Mais un siècle plus tard, la Grèce, puissante et relativement démocratique sur de nombreux points, s'effondre presque dans les guerres civiles du Péloponnèse, avant d'être soumise par un petit royaume grec du Nord qui, avec Alexandre le grand à sa tête, conquerra l'immense territoire s'étendant de l'Europe à l'Inde. Personne n'aurait pu prédire que ce petit royaume deviendrait maître de la terre au point que les Juifs, des irréductibles s'il en est, traduisirent leurs textes sacrés en grec, la Septante. On mesure encore aujourd'hui toute l'ampleur de cette conquête en Égypte entre autres, où une ville s'appelle Alexandrie. Même chose en Afghanistan où la nouvelle de Rudyard Kipling, L'homme qui voulait être roi et le beau film qu'on en a tiré, évoquent Iskander, c'est-à-dire Alexandre le grand.

Un simple coup d'œil sur les forces en présence sur la plage de Marathon donne les Perses très largement gagnants. Comme on sait, ce fut le contraire. Mais un siècle plus tard, la Grèce, puissante et relativement démocratique sur de nombreux points, s'effondre presque dans les guerres civiles du Péloponnèse, avant d'être soumise par un petit royaume grec du Nord qui, avec Alexandre le grand à sa tête, conquerra l'immense territoire s'étendant de l'Europe à l'Inde. Personne n'aurait pu prédire que ce petit royaume deviendrait maître de la terre au point que les Juifs, des irréductibles s'il en est, traduisirent leurs textes sacrés en grec, la Septante. On mesure encore aujourd'hui toute l'ampleur de cette conquête en Égypte entre autres, où une ville s'appelle Alexandrie. Même chose en Afghanistan où la nouvelle de Rudyard Kipling, L'homme qui voulait être roi et le beau film qu'on en a tiré, évoquent Iskander, c'est-à-dire Alexandre le grand. La politique avant tout, disait Maurras. Parlons plutôt, comme Baudelaire, d’antipolitisme. On sait que le poète, porté, en 1848, par un enthousiasme juvénile, avait participé physiquement aux événements révolutionnaires, appelant même, sans doute pour des raisons peu nobles, à fusiller son beau-père, le général Aupick. Cependant, face à la niaiserie des humanitaristes socialistes, à la suite de la sanglante répression, en juin, de l’insurrection ouvrière (il gardera toujours une tendresse de catholique pour le Pauvre, le Travailleur, et il fut un admirateur du poète et chansonnier populiste Pierre Dupont), et devant le cynisme bourgeois (Cavaignac, le bourreau des insurgés, fut toujours un républicain de gauche), il éprouva et manifesta un violent dégoût pour le monde politique, sa réalité, sa logique, ses mascarades, sa bêtise, qu’il identifiait, comme son contemporain Gustave Flaubert, au monde de la démocratie, du progrès, de la modernité. Ce dégoût est exprimé rudement dans ses brouillons très expressifs, aussi déroutants et puissants que les Pensées de Pascal, Mon cœur mis à nu, et les Fusées, qui appartiennent à ce genre d’écrits littéraires qui rendent presque sûrement intelligent, pour peu qu’on échappe à l’indignation bien pensante.

La politique avant tout, disait Maurras. Parlons plutôt, comme Baudelaire, d’antipolitisme. On sait que le poète, porté, en 1848, par un enthousiasme juvénile, avait participé physiquement aux événements révolutionnaires, appelant même, sans doute pour des raisons peu nobles, à fusiller son beau-père, le général Aupick. Cependant, face à la niaiserie des humanitaristes socialistes, à la suite de la sanglante répression, en juin, de l’insurrection ouvrière (il gardera toujours une tendresse de catholique pour le Pauvre, le Travailleur, et il fut un admirateur du poète et chansonnier populiste Pierre Dupont), et devant le cynisme bourgeois (Cavaignac, le bourreau des insurgés, fut toujours un républicain de gauche), il éprouva et manifesta un violent dégoût pour le monde politique, sa réalité, sa logique, ses mascarades, sa bêtise, qu’il identifiait, comme son contemporain Gustave Flaubert, au monde de la démocratie, du progrès, de la modernité. Ce dégoût est exprimé rudement dans ses brouillons très expressifs, aussi déroutants et puissants que les Pensées de Pascal, Mon cœur mis à nu, et les Fusées, qui appartiennent à ce genre d’écrits littéraires qui rendent presque sûrement intelligent, pour peu qu’on échappe à l’indignation bien pensante. Dopo la chiamata alle armi contro lo Stato islamico e la conseguente definizione di «guerriero crociato» riferita al nostro ministro degli Affari Esteri (e della cooperazione), e conseguentemente di nazione nemica riferita all’Italia, gli analisti nazionali portavoce degli interessi superiori dell’economia si sono scatenati in una ridda di articoli che tendono a riconfigurare le priorità della politica estera europea, e nazionale, nei termini di una rinnovata «guerra globale contro il terrorismo».

Dopo la chiamata alle armi contro lo Stato islamico e la conseguente definizione di «guerriero crociato» riferita al nostro ministro degli Affari Esteri (e della cooperazione), e conseguentemente di nazione nemica riferita all’Italia, gli analisti nazionali portavoce degli interessi superiori dell’economia si sono scatenati in una ridda di articoli che tendono a riconfigurare le priorità della politica estera europea, e nazionale, nei termini di una rinnovata «guerra globale contro il terrorismo».

Les élites progressistes ont déclaré la guerre au peuple. En dépit de son ton mesuré et de ses idées modérées, Chantal Delsol a bien compris l’ampleur de la lutte : « Éduque-les, si tu peux », disait Marc-Aurèle. Toutes les démocraties savent bien, depuis les Grecs, qu’il faut éduquer le peuple, et cela reste vrai. Mais chaque époque a ses exigences. « Aujourd’hui, s’il faut toujours éduquer les milieux populaires à l’ouverture, il faudrait surtout éduquer les élites à l’exigence de la limite, et au sens de la réalité. » Mine de rien, avec ses airs discrets de contrebandière, elle a fourni des armes à ceux qui, sous la mitraille de mépris, s’efforcent de résister à la folie contemporaine de la démesure et de l’hubris [la démesure en grec].

Les élites progressistes ont déclaré la guerre au peuple. En dépit de son ton mesuré et de ses idées modérées, Chantal Delsol a bien compris l’ampleur de la lutte : « Éduque-les, si tu peux », disait Marc-Aurèle. Toutes les démocraties savent bien, depuis les Grecs, qu’il faut éduquer le peuple, et cela reste vrai. Mais chaque époque a ses exigences. « Aujourd’hui, s’il faut toujours éduquer les milieux populaires à l’ouverture, il faudrait surtout éduquer les élites à l’exigence de la limite, et au sens de la réalité. » Mine de rien, avec ses airs discrets de contrebandière, elle a fourni des armes à ceux qui, sous la mitraille de mépris, s’efforcent de résister à la folie contemporaine de la démesure et de l’hubris [la démesure en grec]. Chez les Grecs, comme plus tard chez les chrétiens, l’universel (par exemple celui qui fait le citoyen) est une promesse, non pas un programme écrit, c’est un horizon vers lequel on tend sans cesse. Or il s’est produit une rupture historique au moment des Lumières, quand l’universalisme s’est figé en idéologie avec la théorie émancipatrice : dès lors, toute conception ou attitude n’allant pas dans le sens du progrès sera aussitôt considérée non pas comme une opinion, normale en démocratie, mais comme un crime à bannir. Quiconque défendra un enracinement familial, patriotique ou religieux sera accusé de « repli identitaire », expression désormais consacrée. C’est la fameuse « France moisie ». Les champs lexicaux sont toujours éclairants...

Chez les Grecs, comme plus tard chez les chrétiens, l’universel (par exemple celui qui fait le citoyen) est une promesse, non pas un programme écrit, c’est un horizon vers lequel on tend sans cesse. Or il s’est produit une rupture historique au moment des Lumières, quand l’universalisme s’est figé en idéologie avec la théorie émancipatrice : dès lors, toute conception ou attitude n’allant pas dans le sens du progrès sera aussitôt considérée non pas comme une opinion, normale en démocratie, mais comme un crime à bannir. Quiconque défendra un enracinement familial, patriotique ou religieux sera accusé de « repli identitaire », expression désormais consacrée. C’est la fameuse « France moisie ». Les champs lexicaux sont toujours éclairants...

G. W. F. Hegel and his able interpreter Alexandre Kojève claim that the essence of consciousness is “negativity,” that man lives “outside himself,” that man “negates” or “nihilates” nature, that man is a “nothingness” or a “hole in being,” that man is “time that negates space.” What does this mean?

G. W. F. Hegel and his able interpreter Alexandre Kojève claim that the essence of consciousness is “negativity,” that man lives “outside himself,” that man “negates” or “nihilates” nature, that man is a “nothingness” or a “hole in being,” that man is “time that negates space.” What does this mean? Next, let’s consider the ideas of “negating” and “nihilating” nature. When a plant or an animal finds something from the external world that fulfills its needs, it must remove that thing from the outside world and transform and incorporate it into itself. Hegel and Kojève refer to this activity as “negating,” i.e., saying “no.”

Next, let’s consider the ideas of “negating” and “nihilating” nature. When a plant or an animal finds something from the external world that fulfills its needs, it must remove that thing from the outside world and transform and incorporate it into itself. Hegel and Kojève refer to this activity as “negating,” i.e., saying “no.” When discussing the myths of ancient Greece one must first define their meaning and locate their historical settings. The word “myth” has a specific meaning when one reads the ancient Greek tragedies or when one studies the theogony or cosmogony of the early Greeks. By contrast, the fashionable expression today such as “political mythology” is often laden with value judgments and derisory interpretations. Thus, a verbal construct such as “the myth of modernity” may be interpreted as an insult by proponents of modern liberalism. To a modern, self-proclaimed supporter of liberal democracy, enamored with his own system-supporting myths of permanent economic progress and the like, phrases, such as “the myth of economic progress” or “the myth of democracy,” may appear as egregious political insults.

When discussing the myths of ancient Greece one must first define their meaning and locate their historical settings. The word “myth” has a specific meaning when one reads the ancient Greek tragedies or when one studies the theogony or cosmogony of the early Greeks. By contrast, the fashionable expression today such as “political mythology” is often laden with value judgments and derisory interpretations. Thus, a verbal construct such as “the myth of modernity” may be interpreted as an insult by proponents of modern liberalism. To a modern, self-proclaimed supporter of liberal democracy, enamored with his own system-supporting myths of permanent economic progress and the like, phrases, such as “the myth of economic progress” or “the myth of democracy,” may appear as egregious political insults. The prose of Homer or Hesiod is not just a part of the European cultural heritage, but could be interpreted also as a mirror of the pre-Christian European subconscious. In fact, one could describe ancient European myths as primal allegories where every stone, every creature, every god or demigod, let alone each monster, acts as a role model representing a symbol of good or evil. (4) Whether Hercules historically existed or not is beside the point. He still lives in our memory. When we were young and when we were reading Homer, who among us did not dream about making love to the goddess Aphrodite? Or at least make some furtive passes at Daphne? Apollo, a god with a sense of moderation and beauty was our hero, as was the pesky Titan Prometheus, al-ways trying to surpass himself with his boundless intellectual curiosity. Prometheus unbound is the prime symbol of White man’s irresistible drive toward the unknown and toward the truth irrespective of the name he carries in ancient sagas, modern novels, or political treatises. The English and the German poets of the early nineteenth century, the so -called Romanticists, frequently invoked the Greek gods and especially the Titan Prometheus. The expression “Romanticism” is probably not adequate for that literary time period in Europe because there was nothing romantic about that epoch or for that matter about the prose of authors such as Coleridge, Byron, or Schiller, who often referred to the ancient Greek deities:

The prose of Homer or Hesiod is not just a part of the European cultural heritage, but could be interpreted also as a mirror of the pre-Christian European subconscious. In fact, one could describe ancient European myths as primal allegories where every stone, every creature, every god or demigod, let alone each monster, acts as a role model representing a symbol of good or evil. (4) Whether Hercules historically existed or not is beside the point. He still lives in our memory. When we were young and when we were reading Homer, who among us did not dream about making love to the goddess Aphrodite? Or at least make some furtive passes at Daphne? Apollo, a god with a sense of moderation and beauty was our hero, as was the pesky Titan Prometheus, al-ways trying to surpass himself with his boundless intellectual curiosity. Prometheus unbound is the prime symbol of White man’s irresistible drive toward the unknown and toward the truth irrespective of the name he carries in ancient sagas, modern novels, or political treatises. The English and the German poets of the early nineteenth century, the so -called Romanticists, frequently invoked the Greek gods and especially the Titan Prometheus. The expression “Romanticism” is probably not adequate for that literary time period in Europe because there was nothing romantic about that epoch or for that matter about the prose of authors such as Coleridge, Byron, or Schiller, who often referred to the ancient Greek deities: Did Socrates or Plato or Aristotle believe in the existence of harpies, Cyclops, Giants, or Titans? Did they believe in their gods or were their gods only the personified projects of their rituals? Very likely they did believe in their gods, but not in the way we think they did. Some modern scholars of the ancient Greek mythology support this thesis: “The dominant modern view is the exact opposite. For modern ritualists and indeed for most students of Greek religion in the late nineteenth and throughout the twentieth century, rituals are social agendas that are in conception and origin prior to the gods, who are regarded as mere human constructs that have no reality outside the religious belief system that created them.” (11).

Did Socrates or Plato or Aristotle believe in the existence of harpies, Cyclops, Giants, or Titans? Did they believe in their gods or were their gods only the personified projects of their rituals? Very likely they did believe in their gods, but not in the way we think they did. Some modern scholars of the ancient Greek mythology support this thesis: “The dominant modern view is the exact opposite. For modern ritualists and indeed for most students of Greek religion in the late nineteenth and throughout the twentieth century, rituals are social agendas that are in conception and origin prior to the gods, who are regarded as mere human constructs that have no reality outside the religious belief system that created them.” (11).

Resultado de semejante ausencia de luz en la vida contemporánea es, pues, su desequilibrio y su falta de armonía, de templanza. La desmesura lo inunda todo, reiteró Weil: el pensamiento, la acción, la actividad pública y la vida privada. Un desorden, efectivamente, que genera la pérdida de vitalidad y de autonomía en las comunidades y en las personas; que penetra y degrada todas las relaciones y las actividades humanas, a tal punto que los móviles de la conducta individual -restringidos y rebajados al miedo y al dinero-, la opresión del trabajo asalariado y la educación convierten a la gente en seres deshumanizados, infrahumanos. Asimismo, la comunidad –uno de cuyos fines primordiales es mantener la conexión entre el pasado y el futuro- ha sido destruida en todas partes, suplantada por el Estado-nación: en sus palabras, esa “niñera mediocre a la que hay que obedecer”.

Resultado de semejante ausencia de luz en la vida contemporánea es, pues, su desequilibrio y su falta de armonía, de templanza. La desmesura lo inunda todo, reiteró Weil: el pensamiento, la acción, la actividad pública y la vida privada. Un desorden, efectivamente, que genera la pérdida de vitalidad y de autonomía en las comunidades y en las personas; que penetra y degrada todas las relaciones y las actividades humanas, a tal punto que los móviles de la conducta individual -restringidos y rebajados al miedo y al dinero-, la opresión del trabajo asalariado y la educación convierten a la gente en seres deshumanizados, infrahumanos. Asimismo, la comunidad –uno de cuyos fines primordiales es mantener la conexión entre el pasado y el futuro- ha sido destruida en todas partes, suplantada por el Estado-nación: en sus palabras, esa “niñera mediocre a la que hay que obedecer”. Un “mundo bien hecho”, al contrario, sería una “metáfora real” del orden universal; solo la gracia –la luz sobrenatural, aseguró Weil- puede propiciar el fracaso de la fuerza, de la gravedad: convertir la Creación en objeto de perfecta atención y de amor mediante el trabajo, la ciencia, el arte, la técnica y la educación, considerados auténticos medios para sustituir la ficción del dominio ilimitado sobre la naturaleza por la obligación de obedecerla.

Un “mundo bien hecho”, al contrario, sería una “metáfora real” del orden universal; solo la gracia –la luz sobrenatural, aseguró Weil- puede propiciar el fracaso de la fuerza, de la gravedad: convertir la Creación en objeto de perfecta atención y de amor mediante el trabajo, la ciencia, el arte, la técnica y la educación, considerados auténticos medios para sustituir la ficción del dominio ilimitado sobre la naturaleza por la obligación de obedecerla. La noción de descreación testifica, de esta forma, el sorprendente y prodigioso encuentro del pensamiento weileano con antiguas cosmovisiones, cuyo origen se remonta a cinco mil años, aproximadamente, por ejemplo entre los pueblos que habitaron las regiones de América Central o el Altiplano andino y el territorio del Tahuantinsuyo que comprendía gran parte de América del Sur. Un conocimiento, en efecto, que refleja la iluminación sobrenatural en el mundo, traducido a símbolos milenarios como la chakana de los quechuas y aymaras en los Andes -una escalera de cuatro lados que representa los puentes, la unión entre el mundo de los humanos y lo que está arriba, cuya antigüedad se calcula en cuatro mil años-, o el kultrún mapuche –un tambor ancestral utilizado en rituales sagrados de medicina o fertilidad; constituye una representación del universo, los puntos cardinales, las estaciones y en el centro la Tierra-.

La noción de descreación testifica, de esta forma, el sorprendente y prodigioso encuentro del pensamiento weileano con antiguas cosmovisiones, cuyo origen se remonta a cinco mil años, aproximadamente, por ejemplo entre los pueblos que habitaron las regiones de América Central o el Altiplano andino y el territorio del Tahuantinsuyo que comprendía gran parte de América del Sur. Un conocimiento, en efecto, que refleja la iluminación sobrenatural en el mundo, traducido a símbolos milenarios como la chakana de los quechuas y aymaras en los Andes -una escalera de cuatro lados que representa los puentes, la unión entre el mundo de los humanos y lo que está arriba, cuya antigüedad se calcula en cuatro mil años-, o el kultrún mapuche –un tambor ancestral utilizado en rituales sagrados de medicina o fertilidad; constituye una representación del universo, los puntos cardinales, las estaciones y en el centro la Tierra-.

Given its formidable difficulties, why would anyone trouble read a book like Phenomenology of Spirit? Because, if Hegel is right, then world history comes to an end with the writing of his book. Specifically, Hegel held that the battle of Jena brought world history to an end in the concrete realm because it was the turning point in the battle between the principles of the French revolution—liberty, equality, fraternity, secularism, and progress—and the principles of traditional absolutism, the so-called throne-altar alliance.

Given its formidable difficulties, why would anyone trouble read a book like Phenomenology of Spirit? Because, if Hegel is right, then world history comes to an end with the writing of his book. Specifically, Hegel held that the battle of Jena brought world history to an end in the concrete realm because it was the turning point in the battle between the principles of the French revolution—liberty, equality, fraternity, secularism, and progress—and the principles of traditional absolutism, the so-called throne-altar alliance.

Kojève taught this seminar from 1933 to 1939. Although the seminar was very small, it had a tremendous influence on French intellectual life, for its students included such eminent philosophers and scholars as Jacques Lacan, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georges Bataille, Raymond Queneau, Raymond Aron, Gaston Fessard, and Henri Corbin. Through his students, Kojève influenced Sartre, as well as subsequent generation of leading French thinkers, who are known as “postmodernists,” including Foucault, Deleuze, Lyotard, and Derrida—all of whom felt it necessary to define their positions in accordance with or in opposition to Hegel as portrayed by Kojève.

Kojève taught this seminar from 1933 to 1939. Although the seminar was very small, it had a tremendous influence on French intellectual life, for its students included such eminent philosophers and scholars as Jacques Lacan, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georges Bataille, Raymond Queneau, Raymond Aron, Gaston Fessard, and Henri Corbin. Through his students, Kojève influenced Sartre, as well as subsequent generation of leading French thinkers, who are known as “postmodernists,” including Foucault, Deleuze, Lyotard, and Derrida—all of whom felt it necessary to define their positions in accordance with or in opposition to Hegel as portrayed by Kojève. Kojève held that most human beings at the end of history would be reduced to beasts. But some would become gods. How? By becoming wise. At the end of history, the correct and final interpretation of human existence, the Absolute Truth, has been articulated as a system of science by Hegel himself. This system is the wisdom that philosophy has pursued for more than 2,000 years.

Kojève held that most human beings at the end of history would be reduced to beasts. But some would become gods. How? By becoming wise. At the end of history, the correct and final interpretation of human existence, the Absolute Truth, has been articulated as a system of science by Hegel himself. This system is the wisdom that philosophy has pursued for more than 2,000 years.

Le « populisme » évoque un courant d'opinion fondé sur l'enracinement (la patrie, la famille) et jugeant que l'émancipation (mondialisation, ouverture) est allée trop loin. Si le « populisme » est d'abord une injure, c'est que ce courant d'opinion est aujourd'hui frappé d'ostracisme. Cet ouvrage a pour but de montrer sur quoi repose cet ostracisme, ses fondements et ses arguments. Et les liens entre le peuple et l'enracinement, entre les élites et l'émancipation. Extrait de "Populisme - les demeurés de l'Histoire", de Chantal Delsol,édité aux éditions du Rocher (1/2).

Le « populisme » évoque un courant d'opinion fondé sur l'enracinement (la patrie, la famille) et jugeant que l'émancipation (mondialisation, ouverture) est allée trop loin. Si le « populisme » est d'abord une injure, c'est que ce courant d'opinion est aujourd'hui frappé d'ostracisme. Cet ouvrage a pour but de montrer sur quoi repose cet ostracisme, ses fondements et ses arguments. Et les liens entre le peuple et l'enracinement, entre les élites et l'émancipation. Extrait de "Populisme - les demeurés de l'Histoire", de Chantal Delsol,édité aux éditions du Rocher (1/2).

Les conflits virulents qui ont troublé la vie politique ces deux dernières années ont semblé ranimer la vieille dichotomie entre « gauche » et « droite ». Ne s’agirait-il pas d’une illusion engendrée par la persistance, dans le champ de l’imaginaire idéologique, de réflexes désuets?

Les conflits virulents qui ont troublé la vie politique ces deux dernières années ont semblé ranimer la vieille dichotomie entre « gauche » et « droite ». Ne s’agirait-il pas d’une illusion engendrée par la persistance, dans le champ de l’imaginaire idéologique, de réflexes désuets?

C’est évidemment la persistance historique de cette sensibilité morale et philosophique (l’idée, en somme, que toute acceptation de la servitude est forcément déshonorante pour un être humain digne de ce nom) qui explique le développement, au sein du mouvement socialiste originel – et notamment parmi ces artisans et ces ouvriers de métier que leur savoir-faire protégeait encore d’une dépendance totale envers la logique du salariat – d’un puissant courant libertaire, allergique, par nature, à tout « socialisme d’État », à tout « gouvernement des savants » (