Kerry Bolton

Ex: http://www.wermodandwermod.com/

Abstract

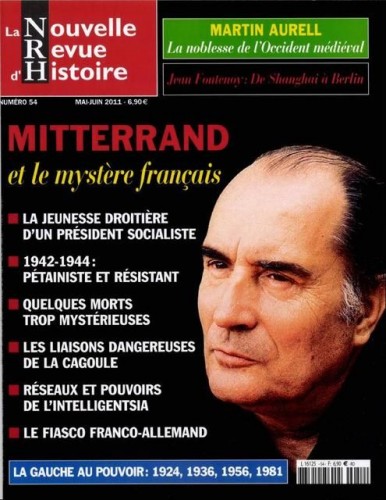

There is a subject that generally seems to be “no go” among academe: a critical attitude towards Trotsky and a less than slanderous attitude towards his nemesis, Stalin. Submission of papers on the subject is more likely to elicit responses of the type one would expect from outraged Trotskyite diehards than those of a scholarly critique. However, the battle between Trotsky and Stalin is not just one of theoretical interest, as it laid the foundations for outlooks on Russia and strategies in regard to the Cold War. The legacy continues to shape the present era, even after the implosion of the USSR. The following paper is intended to consider the Stalinist allegations against Trotsky et al in the context of history, and how that history continues to unfold.

Introduction

Trotsky had received comparatively good press in the West, especially since World War II, when the wartime alliance with Stalin turned sour. Trotsky has been published by major corporations,[1] and is generally considered the grandfatherly figure of Bolshevism.[2] “Uncle Joe,” on the other hand, was quickly demonized as a tyrant, and the “gallant Soviet Army” that stopped the Germans at Stalingrad was turned into a threat to world freedom, when in the aftermath of World War II the USSR did not prove compliant in regard to US plans for a post-war world order.[3] However, even before the rift, basically from the beginning of the Moscow Trials, Western academics such as Professor John Dewey condemned the proceedings as a brutal travesty. The Moscow Trials are here reconsidered within the context of the historical circumstances and of the judicial system that Trotsky and other defendants had themselves played prominent roles in establishing.

A reconsideration of the Moscow Trials of the defendants Trotsky et al is important for more reasons than the purely academic. Since the scuttling of the USSR and of the Warsaw Pact by a combination of internal betrayal and of subversion undertaken by a myriad of US-based “civil societies” and NGOs backed by the likes of the George Soros network, Freedom House, National Endowment for Democracy, and dozens of other such entities,[4] Russia – after the Yeltsin interregnum of subservience to globalisation –has sought to recreate herself as a power that offers a multipolar rather than a unipolar world. A reborn Russia and the reshaping of a new geopolitical bloc which responds to Russian leadership, is therefore of importance to all those throughout the world who are cynical about the prospect of a “new world order” dominated by “American ideals.” US foreign policy analysts, “statesmen” (sic), opinion moulders, and lobbyists still have nightmares about Stalin and the possibility of a Stalin-type figure arising who will re-establish Russia’s position in the world. For example, Putin, a “strongman” type in Western-liberal eyes at least, has been ambivalent about the role of Stalin in history, such ambivalence, rather than unequivocal rejection, being sufficient to make oligarchs in the USA and Russia herself, nervous. Hence, The Sunday Times, commenting on the Putin phenomena being dangerously reminiscent of Stalinism, stated recently:

Joseph Stalin sent millions to their deaths during his reign of terror, and his name was taboo for decades, but the dictator is a step closer to rehabilitation after Vladimir Putin openly praised his achievements.

The Prime Minister and former KGB agent used an appearance on national television to give credit to Stalin for making the Soviet Union an industrial superpower, and for defeating Hitler in the Second World War.

In a verdict that will be obediently absorbed by a state bureaucracy long used to taking its cue from above, Mr Putin declared that it was “impossible to make a judgment in general” about the man who presided over the Gulag slave camps. His view contrasted sharply with that of President Medvedev, Russia’s nominal leader, who has said that there is no excuse for the terror unleashed by Stalin.

Mr Putin said that he had deliberately included the issue of Stalin’s legacy in a marathon annual question-and-answer programme on live television, because it was being “actively discussed” by Russians.[5]

While The Times’ Halpin commented that Putin nonetheless gave the obligatory comments about the brutality of Stalin’s regime, following a forceful condemnation of Stalin by Medvedev on October 9, 2009, it is worrying nonetheless that Putin could state that positive aspects “undoubtedly existed.” Such comments are the same as if a leading German political figure had stated that some positive aspects of Hitler “undoubtedly existed.” The guilt complex of Stalinist tyranny, having its origins in Trotskyite Stalinophobia, which has been carried over into the present “Cold War II” era of a bastardous mixture of “neo-cons” (i.e., post-Trotskyites) and Soros type globalists, often working in tandem despite their supposed differences,[6] is supposed to keep Russian down in perpetuity. Should Russia rise again, however, the spectre of Stalin is there to frighten the world into adherence to US policy in the same way that the “war on terrorism” is designed to dragoon the world behind the USA. Just as importantly, The Times article commented on Putin’s opposition to the Russian oligarchy, which has been presented by the Western news media as a “human rights issue”:

During the television programme, Mr Putin demonstrated his populist instincts by lashing out at Russia’s billionaire class for their vulgar displays of wealth. His comments came after a scandal in Geneva, when an elderly man was critically injured in an accident after an alleged road race involving the children of wealthy Russians in a Lamborghini and three other sports cars. “The nouveaux riches all of a sudden got rich very quickly, but they cannot manage their wealth without showing it off all the time. Yes, this is our problem,” Mr Putin said.[7]

This all seems lamentably (for the plutocrats) like a replay of what happened after the Bolshevik Revolution when Stalin kicked out Trotsky et al. Under Trotsky, the Bolshevik regime would have eagerly sought foreign capital.[8] It is after all why plutocrats would have had such an interest in ensuring Trotsky’s safe passage back to Russia in time for the Bolshevik coup, after having had a pleasant stay with his family in the USA as a guest of Julius Hammer, and having been comfortably ensconced in an upmarket flat, with a chauffeur at the family’s disposal.[9] In 1923 the omnipresent globalist think tank the Council on Foreign Relations, was warning investors to hurry up and get into Soviet Russia before something went wrong,[10] which it did a few years later. Under Stalin, even Western technicians were not trusted.[11]

Of particular note, however, is that well-placed Russian politicians and academics are still very aware of the globalist apparatus that is working for what is frequently identified in Russia as a “new world order,” and the responsibility Russia has in reasserting herself to lead in reshaping a “multipolar” world contra American hegemony. This influences Russia’s foreign policy, perhaps the most significant manifestation being the BRIC alliance,[12] despite what this writer regards as the very dangerous liaison with China.[13]

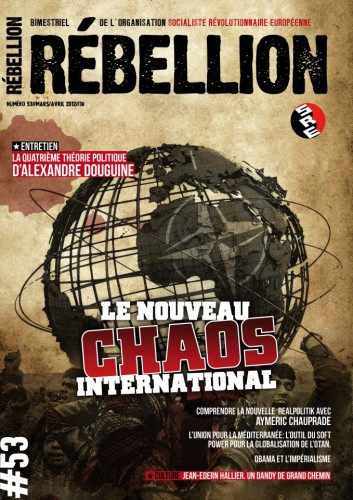

What is dismissed as “fringe conspiracy theory” by the superficial and generally “kept” Western news media and academia, is reported and discussed, among the highest echelons of Russian media, politics, military, and intelligentsia, with an analytical methodology that is all but gone from Western journalism and research. For example the Russian geopolitical theorist Alexander Dugin is a well-respected academic who lectures at Moscow State University under the auspices of the Center for Conservative Studies, which is part of the Department of Sociology (International Relations)[14] The subjects discussed by Professor Dugin and his colleagues and students feature the menace of world government and the challenges of globalism to Russian statehood. The movement he inspired, Eurasianism, has many prominent people in Russia and elsewhere.[15]

Perhaps the best indication of Russia’s persistence in remaining resistant to globalist and hegemonic schemes for world re-organization is the information that is published by the Ministry of International Affairs. Despite the disclaimer, the articles and analyses are a far cry from the shallowness of the mainstream news media of the Western world. Articles posted by the Ministry as this paper is written include a cynical consideration of the North African revolutions and the role of “social media;”[16] and an article pointing to the immense socio-economic benefits wrought by the Qaddafi regime, which is now being targeted by revolts “backed by Western intelligence services.”[17] Political analyst Sergei Shashkov theorizes that:

Recent events perfectly fit into the US-invented concept of “manageable chaos” (also known as “controlled instability” theory). Among its authors are: Zbigniew Brzezinski, a Polish American political scientist, Gene Sharp, who wrote From Dictatorship to Democracy, and Steven Mann, whose Chaos Theory and Strategic Thought was published in Washington in 1992, and who was involved in plotting “color revolutions” in some former Soviet republics.[18]

The only place one is going to get that type of analyses in the West is in alternative media sources such as The Foreign Policy Journal or Global Research. What Western government Ministry would have the independence of mind to circulate analyses of this type? Russians have the opportunity to be the most well-informed people in the world in matters that are of real importance. Westerners, on the other hand, do have that essential freedom – to watch US sitcoms and keep abreast of the tittle-tattle of movie stars and pop singers. Clearly, Russia is not readily succumbing to the type of post-Cold War world as envisaged by plutocrats and US hegemonists, expressed by George H W Bush in his hopes for a “new world order” after the demise of the Soviet bloc.[19] Beginning with Putin, Russia has refused to co-operate in the establishment of the “new world order” just as Stalin did not go along with similar schemes intended for the post-World War II era.

The purging of the USSR of Trotskyites and others by Stalin constituted the first significant move against plutocratic aspirations for Russia. The subsequent Russophobia that continues among American foreign policy and other influential circles has an ideological and historical framework arising to a significant extent therefore. The Moscow Trials, and the reaction symbolized by the Dewey Commission, gave primary impetus to a movement that was to metamorphose from Trotskyism to post-Trotskyism and ultimately to the oddly named “neo- conservatism,” and to leading NGOs such as the National Endowment for Democracy. The foundation for the present historical phenomena in regard to Russia was being embryonically shaped even within the Dewey Commission, certain of whose members ended up becoming Cold Warriors.

In the spirit of this legacy, the oligarchs, who were to be unleashed on Russia after the destruction of the USSR, are being upheld by their champions in the West as victims of neo-Stalinism, and their trials are being compared to those of Stalin’s “Moscow Show Trials.” Hence, American Professor Paul Gregory, a Fellow of the Hoover Institution, co-editor of the “Yale-Hoover Series on Stalin, Stalinism, and Cold War,” etc., writes of the trial of oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky:

When the history of Russian justice is written fifty years from now, two landmark court cases will stand out: The death sentence of Nikolai Bukharin in his Moscow show trial of March 1938 and the second prison sentence of Mikhail Khodorkovsky expected December 27, 2010. Both processes teach the same object lesson: anyone who crosses the Kremlin will be punished without mercy. There will be no protection in the courts for the innocent, and the guilty verdict and sentence will be already predetermined behind the Kremlin walls. It also does not matter how preposterous or ludicrous the charges. Vladimir Putin was born in 1952, only one year before Stalin’s death. But Stalin’s system of justice was institutionalized and survived Stalin and the collapse of the Soviet Union, for use by apt pupils such as Putin . . . [20]

If Russia continues to take a “wrong turn” (sic) as it is termed by the US foreign policy Establishment,[21] then we can expect the regime to be increasingly demonized by being compared to that of Stalin, just as other regimes ripe for “change,” (such as Milosovic’s Serbia, Saddam’s Iraq and Qaddafi’s Libya) according to the agenda of the globalists, are demonized. John McCain, stated on the Floor of the Senate, speaking of the “New START Treaty” with Russia, that the Khodorkovsky trial indicated that flawed nature of Russia, although McCain admitted that he was “under no illusions” that some of the gains of the oligarch might have been “ill-gotten.”[22] However, to those who do not like the prospect of a renewal of Russia influence, Khodorkovsky is a symbol of the type of Russia they hoped would emerge after the demise of the USSR, and the oligarchs are portrayed as victims of Stalin-like injustice. Old Trot Carl Gershman, the founding president of the Congressionally-funded National Endowment for Democracy, used the Khodorkovsky sentencing as the primary point of condemnation of Russia in his summing up of the world situation frordemocracy in 2010, when stating that:

As 2010 drew to a close, the backsliding accelerated with a flurry of new setbacks—notably the rigged re-sentencing of dissident entrepreneur Mikhail Khodorkovsky in Russia, the brutal repression of the political opposition in Belarus following the December 19 presidential election, and the passage of a spate of repressive new laws in Venezuela, where President Hugo Chavez assumed decree powers.[23]

One can expect “velvet revolutions” to break out in Belarus and Venezuela at any time now, although Russia will obviously take longer to deal with. Hence the vitriol will take on increasingly Cold War proportions, with the accusation of a Stalinist revival being used as prime propaganda material. It is against this background that the legacy of Stalin, including the Moscow Trials for which he is particularly condemned, should be examined.

Background of the Trials

The Moscow Trials comprised three events: The first trial, held in August 1936, involved 16 members of the “Trotskyite-Kamenevite-Zinovievite-Leftist-Counter-Revolutionary Bloc.” The two main defendants were Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. The primary accusations against the defendants were that they had, in alliance with Trotsky, been involved in the assassination of Sergey Kirov in 1934, and of plotting to kill Stalin.[24] After confessing to the charges, all were sentenced to death and executed.

The second trial in January 1937 of the “anti-Soviet Trotskyite-Centre” comprised 17 defendants, including Karl Radek, Yuri Piatakov and Grigory Sokolnikov, who were accused of plotting with Trotsky, who was said to be in league with Nazi Germany. Thirteen of the defendants were executed, and the remainder died in labor camps.

The third trial was held in 1938 against the “Bloc of Rights and Trotskyists,” with Bukharin as the chief defendant. They were accused of having planned to assassinate Lenin and Stalin in 1918, and of having plotted to dismember the USSR for the benefit of foreign powers.

These trials have been condemned as “show trials” yet the very openness to foreign journalists and diplomats, as distinct from secret tribunals, is surely an approach that is to be commended rather than condemned. It also indicates the confidence the Soviet authorities had in their charges against the accused, allowing the processes to be subjected to foreign scrutiny and comment.

The world generally has come to know the Moscow Trials as a collective travesty based on torture, threats to families and forced confessions, with the defendants in confused states, declaring their confessions of guilt by rote, as if hypnotised. The trials are considered in every sense modern-day “witch trials.” For example, Prof. Sidney Hook, co-founder of the “Dewey Commission,” cogently expressed the widely held view of the trials many years later that, “The confessions, exacted by threats and torture, physical and psychological, whose precise nature has never been disclosed, consisted largely of alleged ‘conversations about conversations.’”[25] However the opinions of first-hand observers are not unanimous in condemning the methodology of the trials. The US Ambassador to the USSR, himself a lawyer, Joseph E Davies, was to write of the trials in his memoirs published in 1945 (that is, about seven years after the Dewey Commission had supposedly proven the trials to have been a travesty):

At 12 o’clock noon accompanied by Counselor Henderson I went to this trial. Special arrangements were made for tickets for the Diplomatic Corps to have seats. . . . [26] . . . On both sides of the central aisle were rows of seats occupied entirely by different groups of “workers” at each session, with the exception of a few rows in the centre of the hall reserved for correspondents, local and foreign, and for the Diplomatic Corps. The different groups of “workers,” I am advised, were charged with the duty of taking back reports of the trials to their various organizations.[27]

Davies stated that among the foreign press corps were the following representatives: Walter Duranty and Harold Denny from The New York Times, Joe Barnew and Joe Phillips from The New York Herald Tribune, Charlie Nutter or Nick Massock from Associated Press, Norman Deuel and Henry Schapiro from United Press, Jim Brown from International News, and Spencer Williams from The Manchester Guardian. The London Observer, hardly pro-Soviet, opined that: “It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The Government’s case against the defendants is genuine.”[28] Duranty from The New York Times stated of the 1936 trial of Kamenev, Zinoviev, et al that:

. . . The writer knows beyond doubt that the assassin [of Kirov] was used as an instrument for the needs of political terrorism… No one acquainted with present European politics can fail to realize that, whereas the Soviet government is doing it utmost to maintain peace, there are certain so-called Trotskyist organizations that are trying to cause trouble…[29]

Of Soviet prosecutor Andrei Vyshinsky, Davies opined that: “the prosecutor … conducted the case calmly and generally with admirable moderation.” Especially notable, given the subsequent claims that were made about the allegedly confused, brainwashed appearance and tone of the defendants, Davies observed: “There was nothing unusual in the appearance of the accused. They all appeared well nourished and normal physically.”[30] A delegation of the International Association of Lawyers stated:

We consider the claim that the proceedings were summary and unlawful to be totally unfounded. The accused were given the opportunity of taking counsels.... We hereby categorically declare that the accused were sentenced quite lawfully.[31]

In 1936 the British Labour Member of Parliament, D N Pritt KC, wrote extensively of his observations on the first Moscow Trial. In the lengthy article published in Russia Today, Pritt, after alluding to the apparently good condition of the defendants who, in accord with the observations of Davies, did not appear to have suffered under Soviet detention, wrote:

The first thing that struck me, as an English lawyer, was the almost free-and-easy demeanour of the prisoners. They all looked well; they all got up and spoke, even at length, whenever they wanted to do so (for the matter of that, they strolled out, with a guard, when they wanted to).

The one or two witnesses who were called by the prosecution were cross-examined by the prisoners who were affected by their evidence, with the same freedom as would have been the case in England.

The prisoners voluntarily renounced counsel; they could have had counsel without fee had they wished, but they preferred to dispense with them. And having regard to their pleas of guilty and to their own ability to speak, amounting in most cases to real eloquence, they probably did not suffer by their decision, able as some of my Moscow colleagues are.[32]

Pritt was struck by the informality of the proceedings, and commented on how the defendants could interrupt at will, in what seems to have been a freewheeling debate:

The most striking novelty, perhaps, to an English lawyer, was the easy way in which first one and then another prisoner would intervene in the course of the examination of one of their co-defendants, without any objection from the Court or from the prosecutor, so that one got the impression of a quick and vivid debate between four people, the prosecutor and three prisoners, all talking together, if not actually at the same moment—a method which, whilst impossible with a jury, is certainly conducive to clearing up disputes of fact with some rapidity. [33]

Pritt’s view of Vyshinsky is in accord with that of Davies, stating of the prosecutor: “He spoke with vigour and clarity. He seldom raised his voice. He never ranted, or shouted, or thumped the table. He rarely looked at the public or played for effect.”[34] Pritt stated that the fifteen defendants[35] “spoke without any embarrassment or hindrance.” Such was Pritt’s view of the proceedings that his concluding remark states: “But it is equally clear that the judicature and the prosecuting attorney of USSR have taken at least as great a step towards establishing their reputation among the legal systems of the modern world.”[36]

Although Pritt was a Labour Member of Parliament, and was not a communist party member, he was pro-Soviet. Was he, then, capable of forming an objective, professional opinion? Anecdotal evidence suggests he was. Jeremy Murray-Brown, biographer of the Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta, writing to the editor of Commentary in connection with the Moscow Trials, relates that he had had discussions with Pritt in 1970, in the course of which he asked Pritt about the trials:

His reply astonished me. “I thought they were all guilty,” he said, referring to Bukharin and his co-defendants. It was as simple as that; Pritt made no attempt at political justification, but reaffirmed what was for him a matter of clear professional judgment. …In terms of the Soviet Union’s own judicial system, Pritt said, he firmly believed the defendants in the Moscow trials were guilty as charged. It was an argument which came oddly from the man who defended Kenyatta.[37]

Kenyatta, whom Pritt went to Kenya to defend before a British colonial court, had been “evasive” under cross-examination, Pritt stated.[38] Pritt, despite his support for Kenyatta was able to judge the veracity of proceedings regardless of political bias, and had maintained his view of the Moscow trials even in 1970, when it would have been opportune, even among Soviet sympathizers, to conform to the accepted view, including the declarations of Khrushchev. Indeed, Sidney Hook, long since having become a Cold Warrior in the service of the USA, retorted:

In reply to Jeremy Murray-Brown: the significance of D N Pritt’s infamous defense of the infamous Moscow frame-up trials must be appraised in the light of Khrushchev’s revelations of Stalin’s crimes available to the public (outside the Soviet Union) long before Pritt’s avowals to Mr Murray-Brown. Pritt cannot have been unaware of them.[39]

Of course Pritt was not unaware of Khrushchev’s so-called “revelations.” Unlike many former admirers of Stalin, he was simply not impressed by their veracity, and it must be assumed that his scepticism was based on both his eminent judicial experience and his first-hand observations. Certainly, Sidney Hook’s leading role in the formation of the “Dewey Commission” for the exoneration of Trotsky on the pretext of “impartial” hearings, was itself a cynical travesty, as will be considered in this paper.

If there was a general consensus that the proceedings were legitimate, and a quite sceptical attitude towards the findings of the Dewey Commission, despite the eminence of its front man, Prof. John Dewey, what changed to result in such a dramatic and almost universal reversal of opinion? It was a change of perception in regard to Stalin in the aftermath of World War II, and not due to any sudden revelations about the Moscow Trials or about Stalin’s tyranny. The wartime alliance, which, it was assumed, would endure during the post-war era, instead gave way to the Cold War.[40] Such was the hatred of the Trotskyites for the USSR that they were willing to enlist in the ranks of the anti-Soviet crusade even to the extent of working for the CIA[41], and supporting the US in Korea and Vietnam to counter Soviet influence.[42] Their services, as experienced anti-Soviet propagandists, were eagerly sought. Hence the findings of the Dewey Commission, largely ignored in their own time, are now heralded as definitive. The nature of this “Dewey Commission” will now be considered.

“Preliminary Commission of Inquiry into the Charges Made Against Leon Trotsky in the Moscow Trials”

The so-called Dewey Commission, the full title of which was the “Preliminary Commission of Inquiry into the Charges Made Against Leon Trotsky in the Moscow Trials,” having a legalistic and even official sound to it, was convened in March 1937 on the initiative of the American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky as a supposedly “impartial body.”[43] The purpose was said to be, “to ascertain all the available facts about the Moscow Trial proceedings in which Trotsky and his son, Leon Sedov, were the principal accused and to render a judgment based upon those facts.”[44] However, the composition of the Commission indicates that it was set up as a counter-show trial with the preconceived intention of exonerating Trotsky, and was created at the instigation of Trotsky himself.

The stage was set with the founding of the American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky by Prof. Sidney Hook, who persuaded his mentor, Prof. John Dewey, to front for it. Just how “impartial” the Dewey Commission was might be deduced not only from its having been initiated by those sympathetic towards Trotsky, but also by a comment in a Time report at the occasion of Trotsky’s deportation from Norway en route to Mexico: “The American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky spat accusations at the Norwegian Government last week for its ‘indecent and filthy’ behavior in placing the Great Exile & Mme Trotsky on the Norwegian tanker Ruth…”[45]

The mock “trial” organised by the Dewey Commission was prompted by a “demand” from Trotsky from his new abode in Mexico, who “publicly demanded the formation of an international commission of inquiry, since he had been deprived of any opportunity to reply to the accusations before a legally constituted court.”[46] A sub-commission was formed to travel to Mexico and to allow Trotsky to give testimony in his defense under what was supposed to include “cross-examination.” The sub-commission comprised:

- John Dewey as chairman, described by Novack as America’s foremost liberal and philosopher;

- Otto Ruehle, a German Marxist and former Reichstag Deputy;

- Alfred Rosmer, former member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (1920-21);

- Wendelin Thomas, leader of the sailor’s revolt in Germany in 1918 and a former Communist Deputy in the Reichstag; and

- Carlo Tresca, Italian-American anarchist.[47]

Other members, whose political orientations are not mentioned by Novack, were:

- · Benjamin Stolberg, American journalist;

- · Suzanne La Follette, American journalist;

- · Carleton Beals, authority on Latin-American affairs;

- · Edward A Ross, Professor of Sociology at the University of Wisconsin;

- · John Chamberlain, former literary critic of the New York Times; and

- · Francisco Zamora, Mexican journalist.

Of these, Stolberg was a supporter of the Socialist Party, described by fellow commissioner Carleton Beals as being, along with other commissioners, thoroughly under Trotsky’s spell.[48] Suzanne La Follette was described by Beals as having a “worshipful” attitude towards Trotsky.[49] Edward A Ross, who had gone to Soviet Russia in 1917 had come back with a pro-Bolshevik sentiment, writing The Russian Bolshevik Revolution (1921) and The Russian Soviet Republic (1923). John Chamberlain, a Left-leaning liberal by his own description[50], was among those who became so obsessively anti-Soviet that they ended up as avid Cold Warriors in the US camp.[51] In 1946 Chamberlain and Suzanne La Follette, along with free market guru Henry Hazlitt, founded the libertarian journal The Freeman.[52] Both can therefore be regarded as among the many Trotsky-sympathizers who became apologists for American foreign policy,[53] and laid the foundation for the so-called “neo-conservative” movement. Chamberlain and La Follette continued to pursue a vigorous anti-Soviet line at the earliest stages of the Cold War.[54]

Trotsky’s lawyer for the Mexico hearings was Albert Goldman, who had joined the Communist Party of America on its founding in 1920. He was expelled from the party in 1933 for Trotskyism. Goldman was another Trotskyite who became a pro-US Cold Warrior.[55] The Dewey Commission’s “court reporter” (sic) was Albert M Glotzer, who had been expelled from the Communist Party USA in 1928 and with prominent American Trotskyite Max Shachtman, had founded the Communist League and subsequent factions, including the Social Democrats USA,[56] whose executive Secretary had been Carl Gershman, founding president of the National Endowment for Democracy. Glotzer had also served as Trotsky’s secretary in Turkey in 1931, and had met him on other occasions.[57] The Social Democrats USA provided particular support for the Cold War hawk, Sen. Henry Jackson, and has produced other foreign policy hawks such as Elliott Abrams.

Under the façade of an “impartial enquiry” and with a convoluted title that suggests a bona fide judicial basis, the Dewey Commission proceeded to Mexico to “interrogate” (sic) Trotsky on the pretence of objectivity;[58] an image that was to be quickly exposed by the resignation of one of the Commissioners, Carleton Beals.

"Trotsky's Pink Tea Party": The Beals Resignation

Although one would hardly suspect it now, at the time the Dewey Commission was perceived by many as lacking credibility. Time reported that when Dewey returned from Mexico the “kindly, grizzled professor” told a crowd of 3,500 in Manhattan that the preliminary results of the sub-commission justified the continuation of the Commission’s enquiries in the USA and elsewhere. Time offered the view that, “by last week the committee had proved nothing at all,” despite Dewey’s positive spin.[59] Time in referring to the resignation of Carleton Beals cited him as stating that the hearings had been “unduly influenced in Trotsky’s favor,” Beals having “resigned in disgust.”[60] The Dewey report appended a statement attempting to deal with Beals.[61] In a reply to Dewey, Beals wrote in The Saturday Evening Post that despite the publicly stated intention of the enquiry to determine the innocence or guilt of Trotsky the attitudes of the sub-commission members towards Trotsky were those of reverence:

“I want to weep,” remarks one commissioner as we pass out into the frowzy street, “to think of him being here.” All, including Doctor Dewey, chairman of the investigatory commission, join in the chorus of sorrow over Trotsky’s fallen star - except one commissioner, who sees the pathos of human change in less personal terms.[62]

Beals observing Trotsky in action considered that,

above all, his mental faculties are blurred by a consuming lust of hate for Stalin, a furious uncontrollable venom which has its counterpart in something bordering on a persecution complex - all who disagree with him are bunched in the simple formula of GPU agents, people “corrupted by the gold of Stalin.”[63]

It is evident from Beals’ comments - and Beals had no particular axe to grind - that the persona of Trotsky was far from the rational demeanour of a wronged victim. From Beals’ comments Trotsky seems to have presented himself in a manner that is suggestive of the descriptions often levelled against the Stalinist judiciary, making wild accusations about the supposed Stalinist affiliations of any detractors. Beals questioned Trotsky concerning his archives, since Trotsky was making numerous references to them to prove his innocence, but Trotsky “hems and haws.” While Trotsky denied that his archives had been purged of anything incriminating, important documents had been taken out. A primary insistence of Trotsky’s defense was his denial of having any communication with the accused after 1929. However Dr J Arch Getty comments:

Yet it is now clear that in 1932 he sent secret personal letters to former leading oppositionists Karl Radek, G. Sokol’nikov, E. Preobrazhensky, and others. While the contents of these letters are unknown, it seems reasonable to believe that they involved an attempt to persuade the addressees to return to opposition.[64]

Unlike virtually all Trotsky’s other letters (including even the most sensitive) no copies of these remain in the Trotsky Papers. It seems likely that they have been removed from the Papers at some time. Only the certified mail receipts remain. At his 1937 trial, Karl Radek testified that he had received a letter from Trotsky containing “terrorist instructions,” but we do not know whether this was the letter in question.[65]

It can be noted here that, as will be related below, Russian scholar Prof. Rogovin, in seeking to show that the Opposition bloc maintained an effective resistance to Stalin, also stated that a “united anti-Stalin bloc” did form in 1932, despite Trotsky’s claim at the Dewey hearings that there had been no significant contact with any of the Moscow defendants since 1929. Beals found it difficult to believe Trotsky’s insistence that his contacts inside the USSR had since 1930 consisted of no more than a half dozen letters to individuals. If it was the case that Trotsky no longer had a network within the USSR then he and the Fourth International, and Trotskyism generally, must have been nothing other than bluster.[66]

Beals’ less than deferential line of questioning created antagonism with the rest of the Commission. They began to change the rules of questioning without consulting him. Beals concluded by stating that either Finerty, whom he regarded as acting like Trotsky’s lawyer instead of that of the commission’s counsel, resign, or he would. Suzanne LaFollette “burst into tears” and implored Beals to apologise to Finerty, otherwise the “great historical occasion” would be “marred.” Beals left the room of the Mexican villa with the Commissioners chasing after him. Dewey was left to try and rationalize the situation with the press, while Beals countered that “the commission’s investigations were a fraud.”[67] In the concluding remarks of his article, with the subheading “The Trial that Proved Nothing,” Beals stated that:

- There had been no adequate cross-examination.

- The Trotsky archives had not been examined.

- The cross-examination was a “scant day and a half,” mostly taken up with questions about the Russian Revolution, relations with Lenin, and questions about dialectical theory.

- Most of the evidence submitted was in the form of Trotsky’s articles and books, which could have been consulted at a library.

The commission then resumed in New York, about which Beals predicted, “no amount of fumbling over documents in New York can correct the omissions and errors of its Mexican expedition,” adding:

From the press I learned that seven other commissions were at work in Europe, and that these would send representatives to form part of the larger commission. I was unable to find out how these European commissions had been created, who were members of them. I suspected them of being small cliques of Trotsky’s own followers. I was unable to put my seal of approval on the work of our commission in Mexico. I did not wish my name used merely as a sounding board for the doctrines of Trotsky and his followers. Nor did I care to participate in the work of the larger organization, whose methods were not revealed to me, the personnel of which was still a mystery to me.

Doubtless, considerable information will be scraped together. But if the commission in Mexico is an example, the selection of the facts will be biased, and their interpretation will mean nothing if trusted to a purely pro-Trotsky clique. As for me, a sadder and wiser man, I say, a plague on both their houses.[68]

As can be seen from the last sentence of the above, Beals was not aligned to either Trotsky or Stalin. He had accepted a position with the Dewey Commission in the belief that it sought to get to the matter of the accusations against the Moscow defendants, and specifically Trotsky, in a professional manner. What Beals found was a set-up that was predetermined to exonerate Trotsky and give the “Old Man” a podium upon which to vent his spleen against his nemesis, Stalin. It is also apparent that Trotsky attempted to detract accusations by alleging that anyone who doubted his word was in the pay of Stalin. Yet today the consensus among scholars is that Stalin contrived false allegations about Trotsky et al, and any suggestion to the contrary is met with vehemence rather than with scholarly rebuttal.[69]

The third session of the Mexico hearings largely proceeded on the question of the relations between Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev, and the formation of the Stalin-Kamenev-Zinoviev troika that ran the Soviet state when Lenin became incapacitated. The primary point was that Kamenev and Zinoviev were historically rivals of Trotsky and allies of Stalin in the jockeying for leadership. However, the Moscow testimony also deals with the split of the troika, when alliances changed and Zinoviev and Kamenev became allied with Trotsky. Trotsky in reply to a question from Goldman as to the time of the split, replied: “It was during the preparation, the secret preparation of the split. It was in the second half of 1925. It appeared openly at the Fourteenth Congress of the Party. That was the beginning of 1926.”

Trotsky was asked to explain the origins of the Zinoviev split with Stalin and the duration of the alliance with Trotsky. This, it should be noted, was at the time of an all-out offensive against Stalin, during which, Trotsky explains in his memoirs, “In the Autumn the Opposition even made an open sortie at the meeting of Party locals.”[70] At the time the “New Opposition” group led by Zinoviev and Kamenev aligned with Trotsky to form the “United Opposition.” Trotsky also stated in his memoirs that Zinoviev and Kamenev, despite being ideologically at odds with Stalin, tried to retain their influence within the party, Trotsky having been outvoted by the Bolshevik Party membership which had in a general referendum voted 740,000 to 4,000 to repudiate him:

Zinoviev and Kamenev soon found themselves in hostile opposition to Stalin; when they tried to transfer the dispute from the trio to the Central Committee, they discovered that Stalin had a solid majority there. They accepted the basic principles of our platform. In such circumstances, it was impossible not to form a bloc with them, especially since thousands of revolutionary Leningrad workers were behind them.[71]

It seems disingenuous that Trotsky could subsequently claim that there could not have been a further alliance with Zinoviev and Kamenev, given that alliances were constantly changing, and that these old Bolshevik idealists seem to have been thoroughgoing careerists and opportunists willing to embrace any alliance that would further their positions. Trotsky cited the report of the party Central Committee of the July 1926 meeting at which Zinoviev confessed his “two most important mistakes;” that of having opposed the October 1917 Revolution, and that of aligning with Stalin in forming the “bureaucratic-apparatus of oppression.” Zinoviev added that Trotsky had “warned with justice of the dangers of the deviation from the proletarian line and of the menacing growth of the apparatus regime. Yes, in the question of the bureaucratic-apparatus oppression, Trotsky was right against us.”[72]

During 1927 the alliance between Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev had fallen apart as Zinoviev and Kamenev again sought to flow with the tide. The break with Trotsky came just a few weeks before Trotsky’s expulsion from the Party, as the “Zinoviev group” wanted to avoid expulsion. However all the oppositionists were expelled from the party at the next Congress. Six months after their expulsion and exile to Siberia, Kamenev and Zinoviev reversed their position again, and they were readmitted to the party.

During 1927 Trotsky states that many young revolutionaries came to him eager to oppose Stalin for his having betrayed the Chinese Communists by insisting they subordinate themselves to Chiang Kai-shek. Trotsky claimed: “Hundreds and thousands of revolutionaries of the new generation were grouped about us… at present there are thousands of such young revolutionaries who are augmenting their political experience by studying theory in the prisons and the exile of the Stalin regime.”[73] With this backing the opposition launched its offensive against the Party:

The leading group of the opposition faced this finale with its eyes wide open. We realized only too clearly that we could make our ideas the common property of the new generation not by diplomacy and evasions but only by an open struggle which shirked none of the practical consequences. We went to meet the inevitable debacle, confident, however, that we were paving the way for the triumph of our ideas in a more distant future.[74]

Trotsky then referred to “illegal means” as the only method by which to force the opposition onto the Party at the Fifteenth Congress at the end of 1927. From Trotsky’s description of the tumultuous events during 1927 it seems clear that this was a revolutionary situation that the opposition was trying to create that would overthrow the regime just as the October 1917 coup had overthrown Kerensky:

Secret meetings were held in various parts of Moscow and Leningrad, attended by workers and students of both sexes…. In all, about 20,000 people attended such meetings in Moscow and Leningrad. The number was growing. The opposition cleverly prepared a huge meeting in the hall of the High Technical School, which had been occupied from within. The hall was crammed with two thousand people, while a huge crowd remained outside in the street. The attempts of the administration to stop the meeting proved ineffectual. Kamenev and I spoke for about two hours. Finally the Central Committee issued an appeal to the workers to break up the meetings of the opposition by force. This appeal was merely a screen for carefully prepared attacks on the opposition by military units under the guidance of the GPU. Stalin wanted a bloody settlement of the conflict. We gave the signal for a temporary discontinuance of the large meetings. But this was not until after the demonstration of November 7.[75]

In October 1927, the Central Executive Committee held its session in Leningrad, and a mass official demonstration was staged in honour of the event. Trotsky recorded that the demonstration was taken over by Zinoviev and himself and their followers by the thousands, with support from sections of the military and police. This was shortly followed by a similar event in Moscow commemorating the October 1917 Revolution, during which the opposition infiltrated the parades. A similar attempt at a parade in Leningrad resulted in the detention of Zinoviev and Radek, but Zinoviev wrote optimistically to Trotsky that this would play into their hands. However, at the last moment, the Zinoviev group backed down in order to try and avoid expulsion from the party at the Fifteenth Congress.[76] However Trotsky admitted to having conversations with Zinoviev and Kamenev at a joint meeting at the end of 1927. Trotsky then stated that he had a final communication from Zinoviev on November 7 1927 in which Zinoviev closes: “I admit entirely that Stalin will tomorrow circulate the most venomous “versions.” We are taking steps to inform the public. Do the same. Warm greetings, Yours, G. ZINOVIEV.”[77]

As stated by Goldman, Trotsky’s counsel at Mexico, the letter was addressed to Kamenev, Trotsky, and Y P Smilga. Trotsky explained that, “Smilga is an old member of the Party, a member of the Central Committee of the Party and a member of the Opposition, of the center of the Opposition at that time.” The following questioning then took place:

Stolberg: What do you mean by the center of the Opposition? The executive committee?

Trotsky: It was an executive committee, yes, the same as a central committee.

Goldman: Of the leading comrades of the Left Opposition?

Trotsky: Yes.’[78]

Trotsky stated that thereafter he had “absolute hostility and total contempt” for those who “capitulated,” and that he wrote many articles denouncing Zinoviev and Kamenev. Goldman read from a statement by prosecutor Vyshinsky at the January 28 session of the 1937 Moscow trial:

The Trotskyites went underground, they donned the mask of repentance and pretended that they had disarmed. Obeying the instruction of Trotsky. Pyatakov and the other leaders of this gang of criminals, pursuing a policy of duplicity, camouflaging themselves, they again penetrated into the Party, again penetrated into Soviet offices, here and there they even managed to creep into responsible positions of the state, concealing for a time, as has now been established beyond a shadow of doubt, their old Trotskyite, anti-Soviet wares in their secret apartments, together with arms, codes, passwords, connections and cadres.[79]

Trotsky in reply to a question from Goldman denied any further connection with Kamenev, Zinoviev or any of the other defendants at Moscow. However, as will be considered below, Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev had formed an “anti-Stalinist bloc in June 1932,”[80] a matter only discovered after the investigations in 1935 and 1936 into the Kirov murder.

One of the features of both the first Moscow Trial of 1936 and the Dewey Commission was the allegation that defendant Holtzman, when an official for the Soviet Commissariat for Foreign Trade, had met Trotsky and his son Leon Sedov, at the Hotel Britsol in Copenhagen in 1932. It is a matter that remains the focus of critique and ridicule of the Moscow Trials. For example one Trotskyite article triumphantly declares: “Unbeknown to the prosecutors, the Hotel Bristol had been demolished in 1917! The Stalinist investigators had not done their homework.”[81] Prominent historians continue to cite the supposed non-existence of the Hotel Bristol when Trotsky and his son were supposed to be conspiring with Holtzman, as a primary example of the crass nature of the Stalinist allegations. While Trotsky confirmed that he was in Copenhagen at the time of the alleged meeting, the Dewey Commission accepted statements that the Hotel Bristol had burned down in 1917 and had never reopened. The claim had first been made by the Danish newspaper Social-Demokraten shortly after the death sentences of the 1936 trial had been carried out.[82] In response Arbejderbladet, the organ of the Danish Communist Party, pointed out that in 1932 the Grand Hotel was connected by an interior doorway to the café Konditori Bristol. Moreover both the hotel and the café were owned by a husband and wife team. Arbejderbladet editor Martin Nielsen contended that a foreigner not familiar with the area would assume that he was at the Hotel Bristol.

However these factors were ignored by the Dewey Commission, and still are ingored. Instead the Commission accepted a falsely sworn affidavit by Esther and B J Field, Trotskyites, who claimed that the Bistol café was two doors away from the Grand Hotel and that there was a clear distinction between the two enterprises. Goldman, Trotsky’s lawyer, had stated at the fifth session of the hearings in Mexico that despite the statements that Holtzman was forced to make at the 1936 Moscow trial that he had met Trotsky at the Hotel Bristol, and was “put up” there, “…immediately after the trial and during the trial, when the statement, which the Commissioners can check up on, was made by him, a report came from the Social-Democratic press in Denmark that there was no such hotel as the Hotel Bristol in Copenhagen; that there was at one time a hotel by the name of Hotel Bristol, but that was burned down in 1917…”

Goldman sought to repudiate a claim by the publication Soviet Russia Today that stated that the Bristol café is not next to the Grand Hotel, and used the Field affidavit for the purpose, and that there was no entrance connecting the two, the Fields stating,

As a matter of fact, we bought some candy once at the Konditori Bristol, and we can state definitely that it had no vestibule, lobby, or lounge in common with the Grand Hotel or any hotel, and it could not have been mistaken for a hotel in any way, and entrance to the hotel could not be obtained through it.[83]

The question of the Bristol Hotel was again raised the following day, at the 6th session of the Dewey hearings. Such was – and is – the importance attached to this in repudiating the Stalinist allegations as clumsy. In 2008 Sven-Eric Holström undertook some rudimentary enquiries into the matter. Consulting the 1933 street and telephone directories for Copenhagen he found that – the Field’s affidavit notwithstanding - the Grand Hotel and the Bristol café were located at the same address.[84] Furthermore, photographs of the period show that the street entrance to the hotel and the café were the same and the only signage from the outside states “Bristol.”[85] Again, contrary to the Field affidavit, diagrams of the building show that there was a lobby and internal entrance connecting the hotel and the café. Anyone walking off the street into the hotel would assume, on the basis of the signage and the common entrance that he had walked into a hotel called “Hotel Bristol.” Getty states that Trotsky’s papers archived at Harvard show that Holtzman, a “former” Trotskyite, had met Sedov in Berlin in 1932 “and gave him a proposal from veteran Trotskyist Ivan Smirnov and other left oppositionists in the USSR for the formation of a united opposition bloc,”[86] although Trotsky stated at the Dewey hearings on questioning by Goldman that he had never had any “direct or indirect communication” with Holtzman.

If the statements of Trotsky at to the Dewey Commission and his statements in My Life are considered in the context of the allegations presented by Vyshinsky at Moscow, a number of conclusions might be suggested:

- From 1925 there was a Trotsky-Zinoviev-Kamenev bloc, or an “Opposition center,” which Trotsky states had an “executive committee; which functioned as an alternative party ‘central committee.’”

- Although Zinoviev and Kamenev were aligned for a time with Stalin in a troika, they repudiated this in favour of a counter-revolutionary alliance with Trotsky, and spoke at mass demonstrations, along with others such as Radek.

- Trotsky subsequently condemned Kamenev, Zinoviev et al as “contemptible” for “capitulating,” but Zinoviev, on Trotsky’s own account, was writing to him in November 1928 and warning of what he expected to be Stalin’s attacks.

- Was the vehemence with which Trotsky attacked Kamenev, Zinoviev and other Moscow defendants a mere ruse to throw off suspicion in regard to a united Opposition bloc, which, according to Rogovin,[87] had been formalized as an “anti-Stalinist bloc” in 1932?

- On Trotsky’s own account he and Zinoviev, Kamenev, Radek, et al had been at the forefront of a vast counter-revolutionary organization that was of sufficient strength to organize mass disruptions of official events in Moscow and Leningrad, which also had support among military and police personnel.

From his exile in Siberia in 1928, Trotsky on his own account, despite the ever-watchful eye of the GPU, made his home the center of opposition activities.[88] Trotsky had been treated leniently in Siberian exile, and was asked to refrain from opposition activities, but responded with a defiant letter to the All-Union Communist Party and to the Executive Committee of the Communist International, in which he referred to Stalin’s “narrow faction.” He refused to renounce what he called, “the struggle for the interests of the international proletariat...” In the letter to the Politburo dated 15 March 1933, Trotsky warned in grandiose manner:

I consider it my duty to make one more attempt to appeal to the sense of responsibility of those who presently lead the Soviet state. You know conditions better than I. If the internal development proceeds further on its present course, catastrophe is inevitable.[89]

As a means of saving the Soviet Union from self-destruction Trotsky advocated that the Left Opposition be accepted back into the Bolshevik party as an independent political tendency that would co-exist with all other factions, while not repudiating its own programme:[90]

Only from open and honest cooperation between the historically produced fractions, fully transforming them into tendencies in the party and eventually dissolving into it, can concrete conditions restore confidence in the leadership and resurrect the party.[91]

With the failure of the Politburo to reply to Trotsky’s ultimatum, he published both the letter and a statement entitled “An Explanation.”[92] Trotsky then cited his “declaration” in reply to the “ultimatum” he had received to forego oppositionist activities, to the Sixth Party Congress from his remote exile in Alma Ata. In this “declaration” he stated what could also be interpreted as revolutionary opposition to the regime, insofar as he considered that the USSR under Stalin had become a bureaucratic state composed of a “depraved officialdom” that was working for “class interests hostile to the proletariat”:

To demand from a revolutionary such a renunciation (of political activity, i.e., in the service of the party and the international revolution) would be possible only for a completely depraved officialdom. Only contemptible renegades would be capable of giving such a promise. I cannot alter anything in these words ... To everyone, his due. You wish to continue carrying out policies inspired by class forces hostile to the proletariat. We know our duty and we will do it to the end.[93]

The lack of reply from the Politburo in regard to Trotsky’s ultimatum to accept him back into the Government resulted in Trotsky’s final break with the Third International and the creation of the Fourth International in rivalry with the Stalinist parties throughout the world. Trotsky declared that the Bolshevik party and those parties following the Stalinist line, as well as the Comintern now only served an “uncontrolled bureaucracy.”[94] That his aims were something other than mass education and the acceptance of a “tendency” within the Bolshevik party became clearer in 1933 when he wrote that, “No normal ‘constitutional’ ways remain to remove the ruling clique. The bureaucracy can be compelled to yield power into the hands of the proletariat only by force.”[95] What he was advocating was a palace coup that would remove Stalin with minimal disruption. This meant not “an armed insurrection against the dictatorship of the proletariat but the removal of a malignant growth upon it…” These would not be “measures of a civil war but rather the measures of a police character.”[96] The intent was unequivocal, and it appears disingenuous for Trotsky and his apologists to the present day to insist that nothing was meant other than for Trotskyism to be accepted as a “tendency” within the Bolshevik party that could debate the issues in parliamentary fashion.

If Trotsky was less than honest with the fawning Dewey Commission, the farcical “cross examination” by the Commission’s counsel was not going to expose it. Heaven forbid that Trotsky could lie to serve his own cause, and that he could be anything but a saintly figure. Certainly a less than deferential attitude toward Trotsky by Beals was sufficient to set the one objective commissioner at loggerhead with the others. Of the lie as a political weapon, Trotsky was explicit. Trotsky had written in 1938, the very year of the third Moscow Trial, an article chastising a grouplet of German Marxists for adhering to “bourgeoisie” notions of morality such as truthfulness. He stated, “that morality is a product of social development; that there is nothing invariable about it; that it serves social interests; that these interests are contradictory; that morality more than any other form of ideology has a class character.”[97]

Norms “obligatory upon all” become the less forceful the sharper the character assumed by the class struggle. The highest pitch of the class struggle is civil war which explodes into mid-air all moral ties between the hostile classes. … This vacuity in the norms obligatory upon all arises from the fact that in all decisive questions people feel their class membership considerably more profoundly and more directly than their membership in “society”. The norms of “obligatory” morality are in reality charged with class, that is, antagonistic content. … Nevertheless, lying and violence “in themselves” warrant condemnation? Of course, even as does the class society which generates them. A society without social contradictions will naturally be a society without lies and violence. However there is no way of building a bridge to that society save by revolutionary, that is, violent means. The revolution itself is a product of class society and of necessity bears its traits. From the point of view of “eternal truths’ revolution is of course “anti-moral.” … It remains to be added that the very conception of truth and lie was born of social contradictions.[98]

Given the lengthy ideological discourse on the value of the lie and the relativity of morality, it is absurd to rely on any statement Trotsky and his followers make about anything. He lied and obfuscated to the Dewey Commission in the knowledge that he was among friends.

Kirov's Murder

The year after Trotsky’s ultimatum to the Politburo (1934) the popular functionary Kirov was murdered. Trotsky’s view of Kirov was not sympathetic, calling him a “rude satrap [whose killing] does not call forth any sympathy.”[99] The consensus now seems to be that Stalin arranged for the murder of Kirov to blame the opposition as justification for launching a murderous purge against his rivals. For example Robert Conquest states that Kirov was a moderate and a popular rival to Stalin, whose murder was both a means of eliminating a rival and of launching a purge.[100] Not only Trotskyites and eminent historians such as Conquest share this view, but also it was implied by Khrushchev during his 1956 “secret address” to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party.[101] After Stalin’s death several Soviet administrations undertook investigations to try and uncover definitive evidence against him.

The original source for the accusations against Stalin regarding Kirov seems to have been an anonymous “Letter of an Old Bolshevik” published in 1937.[102] It transpired that the “Old Bolshevik” was a Menshevik, Boris Nicolaevsky, who claimed that his information came from Bukharin when the latter was in Paris in 1936. In 1988 Bukharin’s widow published a book on her late husband in which she denied that any such discussions had taken place between Bukharin and Nicolaevsky, and considered the “Letter” to be a “spurious document.”[103]

In 1955 the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party commissioned P N Pospelov, the Secretary of the Central Committee, to investigate Stalinist repression. It had been the opinion of the party by this time that Stalin had been behind the murder of Kirov. Another commission of enquiry was undertaken in 1956. Neither found evidence that Stalin had a hand in the Kirov killing but the findings were not released by Khrushchev, former foreign minister Molotov remarking of the 1956 enquiry: “The commission concluded that Stalin was not implicated in Kirov’s assassination. Khrushchev refused to have the findings published since they didn’t serve his purpose.”[104] As recently as 1989 the USSR was still making efforts to implicate Stalin, and a Politburo Commission headed by A Yakovlev was set up. The two year enquiry concluded that: “In this affair no materials objectively support Stalin’s participation or NKVD participation in the organisation and carrying out of Kirov’s murder.”[105] The findings of this enquiry were not released either.

J Arch Getty writes of the circumstances of the Kirov murder that the OGPU and the NKVD had infiltrated opposition groups and there had been sufficient evidence obtained to consider that the so-called Zinovievites were engaged in dangerous underground activity. Stalin consequently regarded this group as being behind the assassin, Nikolayev. Although their former followers were being rounded up, Pravda announced on December 23, 1934 that there was “insufficient evidence to try Zinoviev and Kamenev for the crime.”[106] When the trial against this bloc did occur two years later it was after many interrogations, and was therefore no hasty process. From the interrogations relative to the Kirov assassination Stalin found out about the continued existence of the Opposition bloc that focused partly around Zinoviev. Vadim Rogovin, a Professor at the Russian Academy of Sciences, wrote that Kamenev and Zinoviev had rejoined Trotsky and formed “the anti-Stalinist bloc in June 1932,” although Trotsky had maintained to the Dewey Commission and subsequently, that no such alliance existed and that he had nothing but contempt for Zinoviev and Kamenev. Rogovin, a Trotskyite academic having researched the Russian archives, stated:

Only after a new wave of arrests following Kirov’s assassination, after interrogations and reinterrogations of dozens of Oppositionists, did Stalin receive information about the 1932 bloc, which served as one of the main reasons for organizing the Great Purge.[107]

In 1934 Yakov Agranov, temporary head of the NKVD in Leningrad, had found connections between the assassin Nikolayev and leaders of the Leningrad Komsomol at the time of Zinoviev’s authority over the city. The most prominent was I I Kotolynov, whom Robert Conquest states “had, in fact, been a real oppositionist.”[108] Kotolynov, a “Zinovievite,” was among those of the so-called “Leningrad terrorist center” found guilty in 1934 of the death of Kirov. The investigation had been of long duration and the influence of Zinoviev’s followers had been established. However, there was considered to be insufficient evidence to charge Zinoviev and Kamenev.[109]

In 1935 other evidence came to light showing that Zinoviev and Kamenev were aware of the “terrorist sentiments” in Leningrad, which they had “inflamed.”[110] While several trials associated with the Kirov killing took place in 1935, in 1936 sufficient evidence had accrued to begin the first of the so-called “Moscow Trials,” of the “Trotsky -Zinoviev Terrorist Center,” including Trotsky and his son Sedov, who were tried in absentia. The defendant Sergei Mrachovsky testified that at the end of 1932 that a terrorist bloc was formed between the Trotskyites and the Zinovievites, stating:

That in the second half of 1932 the question was raised of the necessity of uniting the Trotskyite terrorist group with the Zinovievites. The question of this unification was raised by I N Smirnov… In the autumn of 1932 a letter was received from Trotsky in which he approved the decision to unite with the Zinovievites… Union must take place on the basis of terrorism, and Trotsky once again emphasised the necessity of killing Stalin, Voroshiloy and Kirov... The terrorist bloc of the Trotskyites and the Zinovievites was formed at the end of 1932.[111]

Despite the condemnation that such testimony has received from academia and media, this at least precisely accords with the relatively recent findings of the Trotskyite academic Prof. Rogovin, and the letter from Trotsky sent to Radek et al, in 1932, referred to by J Arch Getty. The Kirov investigations, which were a prelude to the Moscow Trials, were carefully undertaken. When there was still insufficient evidence against Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev et al, this was conceded by the party press. When testimony was obtained implicating the leaders of an opposition bloc, this testimony has transpired to have conformed to what has come to light quite recently in both the Kremlin archives and the Trotsky papers at Harvard.

Rogovin’s Findings

The reality of the Opposition bloc in relation to the Moscow Trials was the theme of a lecture by Prof. Rogovin at Melbourne University in 1996. The motive of Rogovin was to present Trotskyism as having been an effective opposition within Stalinist Russia, and therefore he departs from the usual Trotskyite attitude of denial, stating:

. . . This myth says that virtually the entire population of the Soviet Union was reduced to a stunned silence by the terror, and either said nothing about the repression, or blindly believed in and supported the terror. This myth also claims that the victims of the repression were completely innocent of any crimes, including opposition to Stalin. They were, instead, victims of Stalin’s excessive paranoia. Since there was no serious opposition to the regime of Stalin, according to this myth, the victims were not guilty of such opposition.[112]

Rogovin alludes to anti-Stalinist leaflets that were being widely distributed in the USSR as late as 1938, calling for a “struggle against Stalin and his clique.” Rogovin also however states that there was much more to the opposition than isolated incidents of leaflet distribution:

Of course these are isolated incidents, but prior to the unleashing of the Great Terror there was a much more widespread, more serious, and well-organised opposition to Stalinism as a regime which had veered ever more widely away from the ideals of socialism.

This battle against Stalin began back in 1923 with the formation of the Left Opposition. The inner party struggle unfolded in ever sharper form throughout the 20s.

Thousands and thousands of communists took part in this opposition, openly in the early days and then, after opposition groups were banned, in illegal underground forms against the abolition of party democracy by the Stalinist party clique.

In 1932 the Opposition coalesced, “the old opposition groups” became more active, and “were joined by layers of newly-formed opposition groups.” Many representatives of the opposition groups that year began to discuss ways of uniting into an “anti-Stalinist bloc.” Rogovin states that the year previously Ivan Smirnov, one of the former leaders of the Left Opposition who had capitulated then returned to the opposition, went on an official trip to Berlin where he established contact with Trotsky’s son, Leon Sedov and discussed the need to “coordinate efforts between Trotsky and his son . . . .” What Rogovin states is in agreement with the supposedly forced confessions of the defendants at the Moscow Trials. J Arch Getty had also found similar material in the Trotsky Papers at Harvard, as previously referred to.

Rogovin states that it was only in 1935 and 1936, having assessed the information garnered from the Kirov investigation in 1934, that the secret police were able to find conclusive evidence on the existence of an anti-Stalinist bloc since 1932. “This was one of the main factors which drove Stalin to unleash the Great Terror,” states Rogovin, who also affirms the basis of the Stalinist accusations that “they did try to establish contact among themselves and fight for the overthrow of Stalin’s clique.”

Rogovin’s statements cannot be lightly dismissed. He was speaking as a sympathiser of Trotskyism, who had access to the Soviet archives in the writing of a six volume series on the political conflicts within the Communist Party SU and the Communist International between 1922 and 1940, of which Stalin’s Great Terror is volume four. On his sixtieth birthday in 1997, Rogovin received tribute from Trotskyite luminaries from Germany, Britain and the USA.[113]

Moscow Trials and the Comintern Pact

These events occurred at a time when the USSR was being encircled by hostile powers. War seemed inevitable, and the opposition bloc was of a type that any state in times of conflict could not afford to tolerate. The Anti-Comintern Pact was signed in 1936 between imperial Japan and Nazi Germany, forming an alliance of aggressive intent specifically aimed at the Soviet Union. While German expansion was ideologically based on annexing Russian territories,[114] the Moscow Trials and accusations against the Opposition bloc of complicity with foreign powers were taking place at a time when there was a likelihood of Japan also directing her expansion towards the USSR. The Japanese attacked the USSR in July 1938 and were halted at the Battle of Lake Khasan,[115] and although defeated, then moved in May 1939 into Mongolia up to the Khalkin Gol River.[116] The decisive victory of Russia here was enough to persuade the Japanese only then to re-direct their expansion into China and the Pacific.

From 1936, with the possibility of a two front war from expansionist powers which had joined in an overtly aggressive alliance, a more tolerant attitude by the Soviet regime against those who were advocating defeatism and discord, albeit couched in dialectical semantics about “defence of the degenerated workers’ state,” seems unrealistic, and was not even expected from the Western democracies in wartime, which went as far as classifying segments of their own populations as “enemy aliens” and interning them.[117]

Trotsky hoped that war would undermine the Stalinist regime and lead to a coup, just as World War I had produced a revolutionary situation. It is therefore disingenuous for Trotsky to insist that he was leading a “loyal opposition” that would defend a “degenerated workers’ state.” Trotsky had adopted a similar position in regard to World War I, contrary to the line insisted upon by Lenin,[118] in stating that he would support Russia’s continuation of the war against Germany, which made him the focus of British efforts via R H Bruce Lockhart, special agent to the British War Cabinet, to secure his support.[119] As Trotsky’s duplicity during World War I, and his close association with British Intelligence via R H Bruce Lockhart shows, Stalinist accusations of Trotskyite association with “foreign powers” was at least based on hard experience. Trotsky had shown himself willing to work with British intelligence during World War I in order to secure his own position to the point of defying Lenin.

Another important Moscow defendant, Karl Radek, had previously been an avid promoter of dialogue with the German extreme Right. Given that he was the living stereotype of an anti-Semitic caricature of what a “Jewish Bolshevik” was portrayed as being, there is nothing outlandish about the Stalinist allegation of oppositionists seeking alliances with Japan and Germany. Trotsky had been openly stating that a fascist war against the USSR would provide the revolutionary situation that would enable a coup against the Stalinist regime. Radek had eulogised before the Executive Committee of the Comintern in 1923, the “German Fascist” Schlageter, who had been executed by the French because of his resistance to the Ruhr occupation. Radek’s Bolshevik pitch was for an alliance with German “Fascism”: “We shall do all in our power to make men like Schlageter, who are prepared to go to their deaths for a common cause, not wanderers into the void, but wanderers into a better future for the whole of mankind…”[120] Given the situation confronting the Soviet Russia, form Japan and Germany, Stalin could not be complacent given the past actions of Radek, Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, and the intrigues of Smirnov and Holtzman et al.

While Trotsky claimed that in the event of war he was advocating the “defence of the degenerated workers’ state” on account of its nationalized economy, from the viewpoint of the Soviet regime, the Soviet Union could ill afford dissent and anti-state propaganda in the midst of war. Trotsky, despite his outrage at the allegation that he could play any part in assisting fascist or capitalist powers to invade the Soviet Union, nonetheless advocated a strategy that was to take advantage of the war to propagandise and subvert the Soviet Union to foment a revolutionary situation even among the armed forces, as the Bolsheviks had done during World War I:

We do not change our orientation. But suppose that Hitler turns his weapons to the East and invades the territories occupied by the Red Army ...? The Bolshevik-Leninists will combat Hitler, weapons in hand, but at the same time they will undertake a revolutionary propaganda against Stalin in order to prepare his overthrow at the next stage...[121]

With an attitude of the character openly stated by Trotsky, how tolerant was Stalin expected to be, in the face of extreme provocation at the time of immense internal and external problems? As will be shown below, when Trotsky was in authority, he did not possess any degree of toleration towards rivals and threats, both real and imagined, and did not flinch from having someone killed if it served his own agenda. Trotsky continued to call for a “revolutionary uprising” that implies something more than ‘educating the masses,” using class struggle phraseology to identify Stalin’s bureaucracy as a “class enemy”:

The Fourth International long ago recognized the necessity of overthrowing the bureaucracy by means of a revolutionary uprising of the toilers. Nothing else is proposed or can be proposed by those who proclaim the bureaucracy to be an exploiting “class.” The goal to be attained by the overthrow of the bureaucracy is the reestablishment of the rule of the Soviets, expelling from them the present bureaucracy . . . [122]

This was the nature of Trotsky’s continual call for the overthrow of the Soviet state as it was then constituted. Trotsky explained his position unequivocally in stating what he meant by ‘defending the Soviet state”:

This kind of “defense of the USSR” will naturally differ, as heaven does from earth, from the official defense which is now being conducted under the slogan: “For the Fatherland! For Stalin!” Our defense of the USSR is carried on under the slogan: “For Socialism! For the world revolution! Against Stalin!”[123]

How far could it be expected that Stalin should tolerate subversion and calls for the overthrow of his regime in the event of war with Japan and/or Germany? It is not a matter that was extended even to pacifists by the Western democracies during World War II, even in countries such as New Zealand who were relatively far form the war theatres. Additionally, the Western democracies did not even grant those confined for their pacifism the benefit of any legal proceedings; in contrast to the Moscow defendants, who were given full and public legal procedures according to the system of justice they had helped to create.

Moscow Trials in Accord with Soviet System

If the Trotskyites and their liberal and social democratic allies, as well as historians generally, regard the Moscow Trials as a modern-day “witch hunt,” it was one that proceeded in accordance with the system that Trotsky and the other defendants had fought to implement. The real source of the outrage comes from Stalin having outmanoeuvred his rivals, many such as Zinoviev and Kamenev having been opportunists who became the victims of their own system. Trotsky when in authority was as vehement about the need to eliminate saboteurs, plotters and conspirators as Stalin. Trotsky had stated in 1918: “By suppressing the Constituent Assembly the Soviets first and foremost broke politically the backbone of the intelligentsia’s sabotage. . . .We have broken the old sabotage and cleared out most of the old officials . . . .[124]

At this early period of the Bolshevik regime Trotsky was already alluding to “counter-revolutionary” plots within his own Red Army, yet when the same situation was suggested twenty years later in regard to Trotsky et al at the Moscow Trials, Trotsky fumed that any such suggestion was a lie. When Trotsky had the power he spoke and acted in ways that he and others – including mainstream historians – would describe as “Stalinism.” Trotsky wrote of these “plots”:

Running on ahead somewhat, I must mention that certain of our own Party comrades are afraid that the Army may become an instrument or a focus for counter-revolutionary plots. This danger, in so far as there is some justification for it, must compel us as a whole to direct our attention to the lower levels, to the rank-and-file soldiers of the Red Army. Here we can and must create a foundation such that any attempt to transform the Red Army into an instrument of counter-revolution will prove fruitless . . . . [125]

Yet it was precisely a strategy of Trotsky to try and form cadres within the Red Army, in particular during the course of war with Germany, which would enable him to reassume authority through a “police action” or coup that would replace the Stalinist apparatus.