Populism seeks to rescue popular government from corrupt elites. Naturally, the elites strike back. The most common accusation from elite commentators is that populism is “anti-democratic.” As Yascha Mounk frames it, populism is “the people vs. democracy.” I argue that populism is not anti-democratic, but it is anti-liberal. (See Donald Thoresen’s review of Mounk’s The People vs. Democracy here [2].)

Many critics of populism accuse it of being a form of white identity politics, and many critics of white identity politics accuse it of being populist. Populism and white identity politics are distinct but sometimes overlapping phenomena. I will argue, however, that populism and white identity politics complement one another, so that the strongest form of white identity politics is populist, and the strongest form of populism is identitarian. But first, we need to clarify what populism really is.

Political Ideology or Political Style?

One of the more superficial claims about populism is that it is not a political ideology but simply a “political style.” An ideology is a set of principles. A political style is a way of embodying and communicating political principles. The idea that populism is merely a political style is based on the observation that there are populisms of the Left and the Right, so how could it be a unified ideology? Of course, there are also liberalisms of the Left and Right, but this does not imply that liberalism is merely a style of politics rather than a political ideology.

Principles of Populism

Just as Right and Left liberalism appeal to common political principles, Right and Left populists also have the same basic political ideas:

- All populists appeal to the principle of popular sovereignty. Sovereignty means that a people is independent of other peoples. A sovereign nation is master of its own internal affairs. It can pursue its own ends, as opposed to being subordinated to the ends of others, such as a foreign people or a monarch. The sovereignty of the people is the idea that legitimate government is “of the people, by the people, for the people,” meaning that (1) the people must somehow participate in government, i.e., that they govern themselves, and (2) the state acts in the interest of the people as a whole, i.e., for the common good.

- All populists politically mobilize on the premise that popular government has been betrayed by a tiny minority of political insiders, who have arrogated the people’s right to self-government and who govern for their own factional interests, or foreign interests, but not in the interest of the people as a whole. Populists thus declare that the political system is in crisis.

- All populists hold that the sovereignty of the people must be restored (1) by ensuring greater popular participation in politics and (2) by replacing traitorous elites with loyal servants of the people. Populists thus frame themselves as redeeming popular sovereignty from a crisis.

Two Senses of “the People”

When populists say the people are sovereign, they mean the people as a whole. When populists oppose “the people” to “the elites,” they are contrasting the vast majority, who are political outsiders, to the elites, who are political insiders. The goal of populism, however, is to restore the unity of the sovereign people by eliminating the conflict of interests between the elites and the people.

Ethnic and Civic Peoplehood

There are two basic ways of defining a people: ethnic and civic. An ethnic group is unified by blood, culture, and history. An ethnic group is an extended family with a common language and history. Ethnic groups always emerge in a particular place but do not necessarily remain there. A civic conception of peoplehood is a construct that seeks to impose unity on a society composed of different ethnic groups, lacking a common descent, culture, and history. For instance, civic nationalists claim that a person can become British, American, or Swedish simply by government fiat, i.e., by giving them legal citizenship.

Ethnic nationalism draws strength from unity and homogeneity. Ethnically defined groups grow primarily through reproduction, although they have always recognized that some foreigners can be “naturalized”—i.e., “assimilated” into the body politic—although rarely and with much effort. Civic nationalism lacks the strength of unity but aims to mitigate that fact with civic ideology and to offset it with strength in numbers, since in principle the whole world can have identity papers issued by a central state.

A civic people is a pure social construct imposed on a set of particular human beings that need not have anything more in common than walking on two legs and having citizenship papers. Civic conceptions of peoplehood thus go hand in hand with the radical nominalist position that only individuals, not collectives, exist in the real world.

An ethnic people is much more than a social construct. First of all, kinship groups are real biological collectives. Beyond that, although ethnic groups are distinguished from other biologically similar groups by differences of language, culture, and history, there is a distinction between evolved social practices like language and culture and mere legislative fiats and other social constructs.

Ethnic peoples exist even without their own states. There are many stateless peoples in the world. But civic peoples do not exist without a state. Civic polities are constructs of the elites that control states.

Populism and Elitism

Populism is contrasted with elitism. But populists are not against elites as such. Populists oppose elites for two main reasons: when they are not part of the people and when they exploit the people. Populists approve of elites that are organically part of the people and function as servants of the people as a whole.

Populists recognize that people differ in terms of intelligence, virtue, and skills. Populists want to have the best-qualified people in important offices. But they want to ensure that elites work for the common good of the polity, not for their own factional interests (or foreign interests). To ensure this, populists wish to empower the people to check the power of elites, as well as to create new elites that are organically connected to the people and who put the common good above their private interests. (For more on this, see my “Notes on Populism, Elitism, and Democracy [9].”)

Populism and Classical Republicanism

When political scientists and commentators discuss the history of populism, most begin with nineteenth-century agrarian movements like the Narodniki in Russia and the People’s Party in the United States. But nineteenth-century populism looked backward to the republics of the ancient world, specifically the “mixed regime” of Rome.

Aristotle’s Politics is the most influential theory of the mixed regime. (See my “Introduction to Aristotle’s Politics” here [10].) Aristotle observed that a society can be ruled by one man, a few men, or many men. But a society can never be ruled by all men, since every society inevitably includes people who are incapable of participating in government due to lack of ability, for instance the very young, the crazy, and the senile.

Aristotle also observed that the one, few, or many could govern for their factional interests or for the common good. When one man governs for the common good, we have monarchy. When he governs for his private interests, we have tyranny. When few govern for the common good, we have aristocracy. When the few govern for their private interests, we have oligarchy. When the many govern for the common good, we have polity. When they govern for their factional interests, we have democracy.

It is interesting that for Aristotle, democracy is bad by definition, and that he had to invent a new word, “polity,” for the good kind of popular rule that was, presumably, so rare that nobody had yet coined a term for it.

Aristotle recognized that government by one man or few men is always government by the rich, regardless of whether wealth is used to purchase political power or whether political power is used to secure wealth. Thus popular government always empowers those who lack wealth. The extremely poor, however, tend to be alienated, servile, and greedy. The self-employed middle classes, however, have a stake in the future, long-time horizons, and sufficient leisure to participate in politics. Thus popular government tends to be stable when it empowers the middle classes and chaotic when it empowers the poorest elements.

Finally, Aristotle recognized that a regime that mixes together rule by the one, the few, and the many, is more likely to achieve the common good, not simply because each group is public spirited, but also because they are all jealous to protect their private interests from being despoiled by the rest. Aristotle was thus the first theorist of the “mixed regime.” But he was simply observing the functioning of actually existing mixed regimes like Sparta.

One can generate modern populism quite easily from Aristotle’s premises. Aristotle’s idea of the common good is the basis of the idea of popular sovereignty, which means, first and foremost, that legitimate government must look out for the common good of the people.

Beyond that, Aristotle argued that the best way to ensure legitimate government is to empower the many—specifically the middle class—to participate in government. The default position of every society is to be governed by the one or the few. When the elites govern selfishly and oppress the people, the people naturally wish to rectify this by demanding participation in government. They can, of course, use their power simply to satisfy their factional interests, which is why democracy has always been feared. But if popular rule is unjust, it is also unstable. Thus to be stable and salutary, popular rule must aim at the common good of society.

The great theorist of popular sovereignty is Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In his On the Social Contract, Rousseau claims that the General Will is the fount of sovereignty and legitimacy. What is the General Will? The General Will wills the common good. The common good is not a convention or construct of the General Will but rather an objective fact that must be discovered and then realized through political action.

Rousseau distinguishes the General Will from the Will of All. The General Will is what we ought to will. The Will of All is what we happen to will. The Will of All can be wrong, however. Thus we cannot determine the General Will simply by polling the people.

Rousseau even holds out the possibility that an elite, or a dictator, can know the General Will better than the populace at large. But no matter how the General Will is determined—and no matter who controls the levers of power—political legitimacy arises from the common good of the people.

Populism and Representation

Populism is often associated with “direct” as opposed to “representative” democracy. Populists tend to favor referendums and plebiscites, in which the electorate as a whole decides on important issues, as opposed to allowing them to be decided by representatives in parliament. In truth, though, there is no such thing as direct democracy in which the whole of the people acts. Even in plebiscites, some people always represent the interests of others. Thus democracy always requires some degree of representation.

One can only vote in the present. But a people is not just its present members. It also consists of its past members and its future members. Our ancestors matter to us. They created a society and passed it on to us. They established standards by which we measure ourselves. And just as our ancestors lived not just for themselves, but for their posterity, people today make decisions that affect future generations. Thus in every democratic decision, the living must represent the interests of the dead and the not yet born.

Moreover, within the present generation, some are too young to participate in politics. Others are unable due to disability. The basic principle for excluding living people from the electorate is that they would lower the quality of political decision-making. However, they are still part of the people, and they have genuine interests. Thus the electorate must represent their interests as well.

Beyond that, there are distinctions among competent adults that may lead to further constriction of the electorate, again to raise the quality of political decision-making. For instance, people have argued that the franchise should be restricted to men (because they are the natural guardians of society or because they are more rational than women), or to people with property (because they have more to lose), or to people with children (because they have a greater stake in the future), or to military veterans (because they have proven themselves willing to die, if necessary, for the common good). But again, all of those who are excluded from the franchise are still part of the people, with interests that must be respected. So they must be represented by the electorate.

Thus even in a plebiscite, the people as a whole is represented by only a part, the electorate. Beyond that, unless voting is mandatory, not every member of the electorate will choose to vote. So those who do not vote are represented by those who do.

Thus far, this thought experiment has not even gotten to the question of representative democracy, which takes the process one step further. An elected representative may stand for hundreds of thousands or millions of voters. And those voters in turn stand for eligible non-voters, as well as those who are not eligible to vote, and beyond that, those who are not present to vote because they are dead or not yet born. The not-yet-born is an indefinite number that we hope is infinite, meaning that our people never dies. It seems miraculous that such a multitude could ever be represented by a relative handful of representatives (in the US, 535 Representatives and Senators for more than 300 million living people and untold billions of the dead and yet-to-be-born). Bear in mind, also, that practically every modern politician will eagerly claim to be really thinking about the good of the entire human race.

But we have not yet scaled the highest peak, for people quite spontaneously think of the president, prime minister, or monarch—a single individual—as representing the interests of the entire body politic. Even if that is not their constitutional role, there are circumstances—such as emergencies—in which such leaders are expected to intuit the common good and act accordingly.

Thus it is not surprising that cynics wish to claim that the very ideas of a sovereign people, a common good, and the ability to represent them in politics are simply myths and mumbo-jumbo. Wouldn’t it be better to replace such myths with concrete realities, like selfish individuals and value-neutral institutions that let them peacefully pursue their own private goods?

But the sovereign individual and the “invisible hand” are actually more problematic than the sovereign people and its avatars. From direct democracy in small towns to the popular uprisings that brought down communism, we have actual examples of sovereign peoples manifesting themselves and exercising power. We have actual examples of leaders representing a sovereign people, divining the common good, and acting to secure it.

There is no question that sovereign peoples actually exercise power for their common goods. But how it happens seems like magic. This explains why popular sovereignty is always breaking down. Which in turn explains why populist movements keep arising to return power to the people.

Populism and Democracy

The claim that populism is anti-democratic is false. Populism simply is another word for democracy, understood as popular sovereignty plus political empowerment of the many. Current elites claim that populism threatens “democracy” because they are advocates of specifically liberal democracy. (See my review of Jan-Werner Mueller’s What Is Populism? here [15] and William Galston’s Anti-Pluralism here [16].)

Liberal democrats claim to protect the rights of the individual and of minorities from unrestrained majoritarianism. Liberal democrats also defend “pluralism.” Finally, liberal democrats insist that the majority is simply not competent to participate directly in government, thus they must be content to elect representatives from an established political class and political parties. These representatives, moreover, give great latitude to unelected technocrats in the permanent bureaucracy.

Liberal democracy is, in short, anti-majoritarian and elitist. Populists recognize that such regimes can work for the public good, as long as the ruling elites are part of the people and see themselves as its servants. But without the oversight and empowerment of the people, there is nothing to prevent liberal democracy from mutating into the rule of corrupt elites for their private interests and for foreign interests. This is why populism is on the rise: to root out corruption and restore popular sovereignty and the common good.

Populists need not reject liberal protections for individuals and minorities, ethnic or political. They need not reject “pluralism” when it is understood as freedom of opinion and multiparty democracy. Populists don’t even reject elites, political representation, and technocratic competence. Populists can value all of these things. But they value the common good of the people even more, and they recognize that liberal values don’t necessarily serve the common good. When they don’t, they need to be brought into line. Liberals, however, tend to put their ideology above the common good, leading to the corruption of popular government. Ideological liberalism is a disease of democracy. Populism is the cure.

Populism and White Identity Politics

What is the connection between populism and white identity politics? I am both a populist and an advocate of white identity politics. But there are advocates of white identity politics who are anti-populist (for instance, those who are influenced by Traditionalism and monarchism), and there are non-white populists around the world (for instance, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand).

However, even if there is no necessary connection between populism and white identity politics, I wish to argue that the two movements should work together in every white country. White identitarians will be strengthened by populism, and populism will be strengthened by appeals to white identity.

Why should white identitarians align ourselves with populism? Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin argue in National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy that the rise of national populism is motivated by what they call “the Four Ds.” The first is Distrust, namely the breakdown of public trust in government. The second is Destruction, specifically the destruction of identity, the destruction of the ethnic composition of their homelands due to immigration and multiculturalism. The third trend is Deprivation, referring to the collapse of First-World living standards, especially middle-class and working-class living standards, due to globalization. The final trend is Dealignment, meaning the abandonment of the center-Left, center-Right duopolies common in post-Second World War democracies. (For more on Eatwell and Goodwin, see my “National Populism Is Here to Stay [18].”)

The Destruction of identity due to immigration and multiculturalism is a central issue for white identitarians. The Deprivation caused by globalization is also one of our central issues. The only way to fix these problems is to adopt white identitarian policies, namely to put the interests and identity of indigenous whites first. Once that principle is enshrined, everything we want follows as a matter of course. It is just a matter of time and will.

As for Distrust and Dealignment, these can go for or against us, but we can certainly relate to them, and we can contribute to and shape them as well.

Eatwell and Goodwin argue that the “Four Ds” are longstanding and deep-seated trends. They will be affecting politics for decades to come. National populism is the wave of the future, and we should ride it to political power.

Why do populists need to appeal to white identity? It all comes down to what counts as the people. Is the people at its core an ethnic group, or is it defined in purely civic terms? Populists of the Right appeal explicitly or implicitly to identitarian issues. Populists of the Left prefer to define the people in civic or class terms and focus on economic issues. Since, as Eatwell and Goodwin argue, both identitarian and economic issues are driving the rise of populism, populists of the Right will have a broader appeal because they appeal to both identity and economic issues.

The great task of white identitarians today is to destroy the legitimacy of civic nationalism and push the populism of the Right toward explicit white identitarianism.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [19] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [20] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Car peut-il y avoir violence dans la maîtrise de soi – alors non écrasée par l’audace – et justifiée par le courage de l’homme moral et révolté ?

Car peut-il y avoir violence dans la maîtrise de soi – alors non écrasée par l’audace – et justifiée par le courage de l’homme moral et révolté ? Opposé à elle, le socialisme doit donc constituer une éthique avant tout, c’est-à-dire – dans les mots de Freund – « une con-duite de la vie, une manière de retrouver le sens de l'honneur, de la noblesse d'âme, de l’héroïsme et du sublime ». L’opposition totale au capitalisme ne se fait pas simplement économiquement ou socialement mais aussi moralement et spirituellement. Nous pouvons, par conséquent, qualifier le socialisme de Sorel d’idé-aliste. Dans Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale en 1899, ce sociologue nous dit : « Le but final n'existe que pour notre vie in-térieure [...] il n'est pas en dehors de nous ; il est dans notre propre cœur. »

Opposé à elle, le socialisme doit donc constituer une éthique avant tout, c’est-à-dire – dans les mots de Freund – « une con-duite de la vie, une manière de retrouver le sens de l'honneur, de la noblesse d'âme, de l’héroïsme et du sublime ». L’opposition totale au capitalisme ne se fait pas simplement économiquement ou socialement mais aussi moralement et spirituellement. Nous pouvons, par conséquent, qualifier le socialisme de Sorel d’idé-aliste. Dans Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale en 1899, ce sociologue nous dit : « Le but final n'existe que pour notre vie in-térieure [...] il n'est pas en dehors de nous ; il est dans notre propre cœur. » Précisons que, dans le même ouvrage, Sorel défend le concept de mythe en tant que tel car les mythes, telles des allégories entretenant l’union et la mobilisation d’un groupe humain, sont des « moyens d’agir sur le présent ». Ensuite, « toute discussion sur la manière de les appliquer matériellement sur le cours de l'histoire est dépourvue de sens. C'est l'ensemble du mythe qui importe seul ».

Précisons que, dans le même ouvrage, Sorel défend le concept de mythe en tant que tel car les mythes, telles des allégories entretenant l’union et la mobilisation d’un groupe humain, sont des « moyens d’agir sur le présent ». Ensuite, « toute discussion sur la manière de les appliquer matériellement sur le cours de l'histoire est dépourvue de sens. C'est l'ensemble du mythe qui importe seul ».

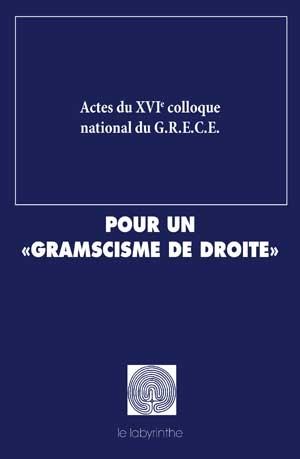

Lo principal que los franceses sacaron del gramscismo fue el rechazo del orden burgués tanto en su infraestructura como en su superestructura. De Benoist y sus colegas enfatizaron que la hegemonía debe entenderse y, lo que es más importante, rechazarse antes de que se logre por completo.

Lo principal que los franceses sacaron del gramscismo fue el rechazo del orden burgués tanto en su infraestructura como en su superestructura. De Benoist y sus colegas enfatizaron que la hegemonía debe entenderse y, lo que es más importante, rechazarse antes de que se logre por completo. Una de las primeras lecturas fundamentales de Gramsci, siguiendo el desarrollo de su influencia, se considera que es la obra del profesor emérito de la Universidad de York Robert Cox (3). Entre los principales artículos científicos de principios de los años ochenta se pueden destacar "Fuerzas sociales, Estados y órdenes mundiales: más allá de la teoría de las relaciones internacionales" [1], "Gramsci, hegemonía y relaciones internacionales: un esbozo de la metodología" [2].

Una de las primeras lecturas fundamentales de Gramsci, siguiendo el desarrollo de su influencia, se considera que es la obra del profesor emérito de la Universidad de York Robert Cox (3). Entre los principales artículos científicos de principios de los años ochenta se pueden destacar "Fuerzas sociales, Estados y órdenes mundiales: más allá de la teoría de las relaciones internacionales" [1], "Gramsci, hegemonía y relaciones internacionales: un esbozo de la metodología" [2].

Otro investigador importante del neogramscismo es Stephen Gil, profesor de ciencias políticas en la Universidad de York. En su libro Poder y resistencia en el Nuevo Orden Mundial, [4] Gil mostró cómo la Comisión Trilateral de la élite actuó como un "intelectual orgánico" como lo sugiere Gramsci, forjando la ideología (ahora hegemónica) del neoliberalismo y el llamado Consenso de Washington, y más tarde con sus vínculos con la globalización del poder y la resistencia.

Otro investigador importante del neogramscismo es Stephen Gil, profesor de ciencias políticas en la Universidad de York. En su libro Poder y resistencia en el Nuevo Orden Mundial, [4] Gil mostró cómo la Comisión Trilateral de la élite actuó como un "intelectual orgánico" como lo sugiere Gramsci, forjando la ideología (ahora hegemónica) del neoliberalismo y el llamado Consenso de Washington, y más tarde con sus vínculos con la globalización del poder y la resistencia. En su trabajo conjunto "In America's Quest for Supremacy and the Third World" (1988), los autores señalan que después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, las clases dominantes en los Estados Unidos pudieron formar un "bloque histórico" internacional coherente: el "mundo libre". En su núcleo, se encuentra una alianza hegemónica con los países de la Organización de Cooperación Económica (1948), las clases dominantes y la población del Tercer Mundo, las clases dominantes de Europa Occidental y Japón. Todos ellos estuvieron bajo la presión de Estados Unidos en la década de 1980, especialmente a nivel económico. Luego hubo una reconstrucción de la supremacía del mundo estadounidense, que fue "principalmente el resultado del uso efectivo del poder económico".

En su trabajo conjunto "In America's Quest for Supremacy and the Third World" (1988), los autores señalan que después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, las clases dominantes en los Estados Unidos pudieron formar un "bloque histórico" internacional coherente: el "mundo libre". En su núcleo, se encuentra una alianza hegemónica con los países de la Organización de Cooperación Económica (1948), las clases dominantes y la población del Tercer Mundo, las clases dominantes de Europa Occidental y Japón. Todos ellos estuvieron bajo la presión de Estados Unidos en la década de 1980, especialmente a nivel económico. Luego hubo una reconstrucción de la supremacía del mundo estadounidense, que fue "principalmente el resultado del uso efectivo del poder económico".

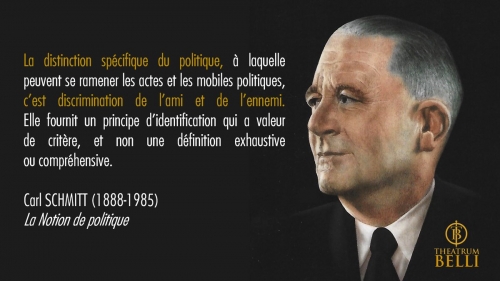

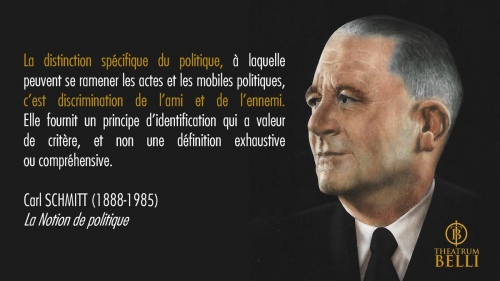

Like many of his books, Carl Schmitt’s The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923) is a slender volume packed with explosive ideas.

Like many of his books, Carl Schmitt’s The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923) is a slender volume packed with explosive ideas. The rationale for making decisions in parliament, as opposed to reposing them in the hands of a single man, is that even the wisest man may benefit from hearing other points of view. We are more likely to arrive at the best possible decision if a number of people bring different perspectives and bodies of knowledge to the table. But the process only works if all parties are open to being persuaded by one another, i.e., they are willing to change their minds if they hear a better argument. This is what argument in “good faith” means, as opposed to merely shilling for a fixed idea.

The rationale for making decisions in parliament, as opposed to reposing them in the hands of a single man, is that even the wisest man may benefit from hearing other points of view. We are more likely to arrive at the best possible decision if a number of people bring different perspectives and bodies of knowledge to the table. But the process only works if all parties are open to being persuaded by one another, i.e., they are willing to change their minds if they hear a better argument. This is what argument in “good faith” means, as opposed to merely shilling for a fixed idea. Liberalism’s abstract egalitarian zeal has never resulted in a global liberal democracy or the enfranchisement of every infant or imbecile (p. 16). Indeed, such goals are impossible. But it has undermined the conditions that make good-faith parliamentary discussions possible.

Liberalism’s abstract egalitarian zeal has never resulted in a global liberal democracy or the enfranchisement of every infant or imbecile (p. 16). Indeed, such goals are impossible. But it has undermined the conditions that make good-faith parliamentary discussions possible. Schmitt isn’t always forthcoming about his own political preferences, but sometimes his rhetoric tips his hand. The first three chapters of Crisis are quite dry, and Schmitt’s arguments only really come into focus in the 1926 Preface to the Second Edition. But chapter 4 crackles with enthusiasm as Schmitt discusses Sorel’s Reflections on Violence, as well as Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and Spanish Catholic reactionary Juan Donoso Cortés. Then Schmitt ends by arguing that nationalism and fascism are more consistent with Sorel’s ultimate premises than are Communism, socialism, or anarcho-syndicalism.

Schmitt isn’t always forthcoming about his own political preferences, but sometimes his rhetoric tips his hand. The first three chapters of Crisis are quite dry, and Schmitt’s arguments only really come into focus in the 1926 Preface to the Second Edition. But chapter 4 crackles with enthusiasm as Schmitt discusses Sorel’s Reflections on Violence, as well as Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and Spanish Catholic reactionary Juan Donoso Cortés. Then Schmitt ends by arguing that nationalism and fascism are more consistent with Sorel’s ultimate premises than are Communism, socialism, or anarcho-syndicalism. Schmitt then hastens to add that a similar vision of a bloody final reckoning was found on the Right: “In 1848 this image rose up on both sides in opposition to parliamentary constitutionalism: from the side of tradition in a conservative sense, represented by a Catholic Spaniard, Donoso Cortés, and in radical anarcho-syndicalism in Proudhon. Both demanded a decision. . . . Instead of relative oppositions accessible to parliamentary means, absolute antitheses now appear” (p. 69). But the tireless talk of bourgeois parliamentarians is all about evading the necessity of decision in the face of hard either/ors, about evading the existence of real enmity. “In the eyes of Donoso Cortés, this socialist anarchist [Proudhon] was an evil demon, a devil, and for Proudhon the Catholic was a fanatical Grand Inquisitor, whom he attempted to laugh off. Today it is easy to see that both were their own real opponent and that everything else was only a provisional half-measure” (p. 70). Schmitt clearly hungers for a similar clarity in Weimar and saw the rise of Fascism in Italy as the present-day nemesis of the Left.

Schmitt then hastens to add that a similar vision of a bloody final reckoning was found on the Right: “In 1848 this image rose up on both sides in opposition to parliamentary constitutionalism: from the side of tradition in a conservative sense, represented by a Catholic Spaniard, Donoso Cortés, and in radical anarcho-syndicalism in Proudhon. Both demanded a decision. . . . Instead of relative oppositions accessible to parliamentary means, absolute antitheses now appear” (p. 69). But the tireless talk of bourgeois parliamentarians is all about evading the necessity of decision in the face of hard either/ors, about evading the existence of real enmity. “In the eyes of Donoso Cortés, this socialist anarchist [Proudhon] was an evil demon, a devil, and for Proudhon the Catholic was a fanatical Grand Inquisitor, whom he attempted to laugh off. Today it is easy to see that both were their own real opponent and that everything else was only a provisional half-measure” (p. 70). Schmitt clearly hungers for a similar clarity in Weimar and saw the rise of Fascism in Italy as the present-day nemesis of the Left. Schmitt closes with an immanent critique of Sorel. First, Schmitt argues that Sorel himself ultimately subordinates proletarian myth and violence to rationalism, because the goal of the revolution is to take control of the means of production. But the modern economic system is of a piece with bourgeois democracy, thus “If one followed the bourgeois into economic terrain, then one must also follow him into democracy and parliamentarism” (p. 73). This does not strike me as particularly persuasive. When Schmitt was writing, the example of Imperial Japan showed that one can have a modern industrial economy without liberal democracy.

Schmitt closes with an immanent critique of Sorel. First, Schmitt argues that Sorel himself ultimately subordinates proletarian myth and violence to rationalism, because the goal of the revolution is to take control of the means of production. But the modern economic system is of a piece with bourgeois democracy, thus “If one followed the bourgeois into economic terrain, then one must also follow him into democracy and parliamentarism” (p. 73). This does not strike me as particularly persuasive. When Schmitt was writing, the example of Imperial Japan showed that one can have a modern industrial economy without liberal democracy. The nineteenth century was the age of parliamentary liberal democracy. The twentieth century is the age of political myths. The rise of political myth is itself “the most powerful symptom of the decline of the relative rationalism of parliamentary thought” (p. 76). The Left may be the gravedigger of liberal democracy, but it offers no real alternative, simply modern materialism and rationalism stripped of the liberal charms of freedom and private life.

The nineteenth century was the age of parliamentary liberal democracy. The twentieth century is the age of political myths. The rise of political myth is itself “the most powerful symptom of the decline of the relative rationalism of parliamentary thought” (p. 76). The Left may be the gravedigger of liberal democracy, but it offers no real alternative, simply modern materialism and rationalism stripped of the liberal charms of freedom and private life.

Il y a longtemps qu’Augustin Cochin avait exposé sa théorie de la confiscation des pouvoirs dans nos modernes démocraties, républiques ou autres nations unies. Cochin expliquait pourquoi ce sont toujours « eux » qui décident et pas « nous » ; on est en 1793, quand les sociétés de pensée ont décidé de refaire l’Homme, la Femme, la France, l’Humanité, le reste. Le triste programme de tabula rasa et de refonte est toujours le même depuis cette époque, dirigé par une élite implacable, conspiratrice et motivée :

Il y a longtemps qu’Augustin Cochin avait exposé sa théorie de la confiscation des pouvoirs dans nos modernes démocraties, républiques ou autres nations unies. Cochin expliquait pourquoi ce sont toujours « eux » qui décident et pas « nous » ; on est en 1793, quand les sociétés de pensée ont décidé de refaire l’Homme, la Femme, la France, l’Humanité, le reste. Le triste programme de tabula rasa et de refonte est toujours le même depuis cette époque, dirigé par une élite implacable, conspiratrice et motivée : Mais Cochin distingue la méthode. Tout est dans la méthode. Et à propos de la Révolution :

Mais Cochin distingue la méthode. Tout est dans la méthode. Et à propos de la Révolution : Cochin précise ensuite que nos utopistes, que nos idéalistes sont dangereux parce qu’ils ne sont pas utopistes précisément. Et il se réclame bien sûr des Grecs (Cité/Polis/Politique), d’Aristophane, de sa satire des mœurs démocratiques athéniennes :

Cochin précise ensuite que nos utopistes, que nos idéalistes sont dangereux parce qu’ils ne sont pas utopistes précisément. Et il se réclame bien sûr des Grecs (Cité/Polis/Politique), d’Aristophane, de sa satire des mœurs démocratiques athéniennes : Puis Cochin s’inspire d’Ostrogorski pour écrire les lignes suivantes :

Puis Cochin s’inspire d’Ostrogorski pour écrire les lignes suivantes : Et voilà pourquoi la machine préfère à toutes les autres les activités malsaines, fiévreuses et stériles, impropres, par nature et par elles-mêmes, à la vie normale. Celles-là seulement ne peuvent être qu’impersonnelles. Un viveur qui dissipe ce qu’il vole : voilà ce qui convient en fait de concussion. »

Et voilà pourquoi la machine préfère à toutes les autres les activités malsaines, fiévreuses et stériles, impropres, par nature et par elles-mêmes, à la vie normale. Celles-là seulement ne peuvent être qu’impersonnelles. Un viveur qui dissipe ce qu’il vole : voilà ce qui convient en fait de concussion. »

La menace à l'ordre social a été perçue autrefois, comme une des réponses à la "Révolte des masses"(Ortega y Gasset - 1930). Cette menace, venant de la social- démocratie, du marxisme théorique et de la révolution russe, fut à la racine d'une réflexion, sur la théorie des élites, représentée, autour des années 1920, par Pareto, Mosca et Michels, en réponse au dysfonctionnement du régime libéral et de son système parlementaire.

La menace à l'ordre social a été perçue autrefois, comme une des réponses à la "Révolte des masses"(Ortega y Gasset - 1930). Cette menace, venant de la social- démocratie, du marxisme théorique et de la révolution russe, fut à la racine d'une réflexion, sur la théorie des élites, représentée, autour des années 1920, par Pareto, Mosca et Michels, en réponse au dysfonctionnement du régime libéral et de son système parlementaire. En effet une époque s'achève, celle du rationalisme moderne, matérialiste, technocratique et instrumental, qui avait perdu sa relation au "sens" de la vie et au tragique, la mort, conduisant à la finitude de l'aventure humaine, imbue du destin et des valeurs ancestrales.

En effet une époque s'achève, celle du rationalisme moderne, matérialiste, technocratique et instrumental, qui avait perdu sa relation au "sens" de la vie et au tragique, la mort, conduisant à la finitude de l'aventure humaine, imbue du destin et des valeurs ancestrales.

Professor Johnson’s academic work is dedicated to the delegitimization of the global capitalist system and the demystification of the ideology that justifies it. This is a demonic, serpentine Leviathan spreading the postmodern acid of American-sponsored mass-zombification to the world.

Professor Johnson’s academic work is dedicated to the delegitimization of the global capitalist system and the demystification of the ideology that justifies it. This is a demonic, serpentine Leviathan spreading the postmodern acid of American-sponsored mass-zombification to the world.

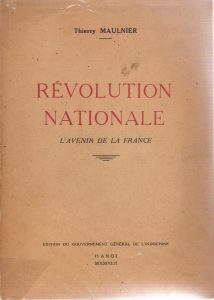

Thierry Maulnier, nom de plume de Jacques Louis André Talagrand (1909 – 1988), a rédigé de nombreux essais, écrit plusieurs pièces de théâtre et donné bien des préfaces. Sa bibliographie comporte cependant une omission de taille : l’absence de Révolution Nationale. L’avenir de la France. Cet ouvrage s’apparente à une sorte de fantôme dont diverses personnes ont nié son existence réelle.

Thierry Maulnier, nom de plume de Jacques Louis André Talagrand (1909 – 1988), a rédigé de nombreux essais, écrit plusieurs pièces de théâtre et donné bien des préfaces. Sa bibliographie comporte cependant une omission de taille : l’absence de Révolution Nationale. L’avenir de la France. Cet ouvrage s’apparente à une sorte de fantôme dont diverses personnes ont nié son existence réelle. Cette hypothèse expliquerait la non reconnaissance de cette édition par Thierry Maulnier d’autant que la même année sort chez Lardanchet La France la guerre et la paix. Dans cet autre recueil, voulu celui-ci par Maulnier, se trouvent trois textes présents dans Révolution Nationale : « Guerre mondiale et Révolution nationale » à l’identique dans les deux ouvrages tandis que les premiers paragraphes de « Rester la France » et « La médiation française » ont été réécrits pour cette parution. Dès la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Thierry Maulnier publie chez Gallimard Violence et Conscience qui « a été écrit en 1942 et 1943 (p. 1) » et qui contient une version modifiée et enrichie à partir du deuxième paragraphe de « Révolution prolétarienne et réaction patriarcale ». En 1946, chez un jeune éditeur moins consensuel, La Table Ronde, paraît Arrière-pensées qui réunit des chroniques « écrites et publiées entre le printemps de 1941 et le printemps de 1944 (p. 5) ». Par rapport à Révolution Nationale, on relit souvent dans une version modifiée, voire changée, « Les poseurs de rails », « Avant l’assaut », « Erreurs de jeunesse », « L’assaut des médiocres », « Les “ intellectuels ” sont-ils responsables du désastre ? », « Un jugement sur Racine », « L’art et l’éducation », « Polémique d’ancien régime » et « L’esprit français est-il coupable ? » qui s’intitule dans Révolution Nationale « Controverses sur l’esprit français » (1). On suppose que les textes qui forment Révolution Nationale proviennent directement des périodiques. Dans le cas des recueils autorisés, Thierry Maulnier a retravaillé certains passages afin de les lier aux autres textes et d’en donner une cohérence interne évidente.

Cette hypothèse expliquerait la non reconnaissance de cette édition par Thierry Maulnier d’autant que la même année sort chez Lardanchet La France la guerre et la paix. Dans cet autre recueil, voulu celui-ci par Maulnier, se trouvent trois textes présents dans Révolution Nationale : « Guerre mondiale et Révolution nationale » à l’identique dans les deux ouvrages tandis que les premiers paragraphes de « Rester la France » et « La médiation française » ont été réécrits pour cette parution. Dès la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Thierry Maulnier publie chez Gallimard Violence et Conscience qui « a été écrit en 1942 et 1943 (p. 1) » et qui contient une version modifiée et enrichie à partir du deuxième paragraphe de « Révolution prolétarienne et réaction patriarcale ». En 1946, chez un jeune éditeur moins consensuel, La Table Ronde, paraît Arrière-pensées qui réunit des chroniques « écrites et publiées entre le printemps de 1941 et le printemps de 1944 (p. 5) ». Par rapport à Révolution Nationale, on relit souvent dans une version modifiée, voire changée, « Les poseurs de rails », « Avant l’assaut », « Erreurs de jeunesse », « L’assaut des médiocres », « Les “ intellectuels ” sont-ils responsables du désastre ? », « Un jugement sur Racine », « L’art et l’éducation », « Polémique d’ancien régime » et « L’esprit français est-il coupable ? » qui s’intitule dans Révolution Nationale « Controverses sur l’esprit français » (1). On suppose que les textes qui forment Révolution Nationale proviennent directement des périodiques. Dans le cas des recueils autorisés, Thierry Maulnier a retravaillé certains passages afin de les lier aux autres textes et d’en donner une cohérence interne évidente. En outre, « le destin de la Révolution nationale, poursuit-il, est précisément de ne se laisser attirer ni par l’ancienne gauche, ni par l’ancienne droite : d’attirer au contraire en elle l’ancienne gauche et l’ancienne droite pour abolir en elles leurs stériles contradictions et pour les anéantir (p. 82) ». Voilà pourquoi « c’est dans la révolution nationale et dans la révolution nationale seule que la France peut aujourd’hui trouver les moyens de guérir ou plutôt de renaître, faire éclater la vigueur d’un génie qui survit intact à ses blessures, affirmer son droit à la vie (pp. 76 – 77) ». Il devient évident que « c’est sur nous et nous seuls que nous devons compter pour créer une civilisation où il nous soit possible de vivre (p. 55) ».

En outre, « le destin de la Révolution nationale, poursuit-il, est précisément de ne se laisser attirer ni par l’ancienne gauche, ni par l’ancienne droite : d’attirer au contraire en elle l’ancienne gauche et l’ancienne droite pour abolir en elles leurs stériles contradictions et pour les anéantir (p. 82) ». Voilà pourquoi « c’est dans la révolution nationale et dans la révolution nationale seule que la France peut aujourd’hui trouver les moyens de guérir ou plutôt de renaître, faire éclater la vigueur d’un génie qui survit intact à ses blessures, affirmer son droit à la vie (pp. 76 – 77) ». Il devient évident que « c’est sur nous et nous seuls que nous devons compter pour créer une civilisation où il nous soit possible de vivre (p. 55) ». Thierry Maulnier conçoit la Révolution Nationale, on l’a vu, comme la matrice d’un nouvel ordre français. « Il faut créer de nouvelles mœurs, de nouvelles valeurs et de nouveaux modes de pensée (p. 71). » Comment ? Ce qu’il propose convient au fonctionnaire de la propagande à Hanoï qui a classé les textes à sa disposition. « refaire une nation, c’est d’abord se donner les moyens de la refaire. C’est d’abord occuper et réorganiser l’État (p. 22). » l’auteur s’intéresse aux interactions psychiques, sociales et politiques entre le « Chef », l’élite et le peuple. « La nature de l’autorité n’est pas seulement d’accroître la force ou pour mieux dire l’efficacité de ceux qui lui obéissent; elle est de métamorphoser cette force en une force de qualité supérieure (p. 204). » Cependant, « l’autorité elle-même, pour atteindre à toute sa vertu, a besoin à son tour de la collaboration de ceux sur qui elle s’exerce. Elle perd beaucoup de son efficacité, s’il ne lui est donné qu’une obéissance passive et comme inerte (p. 205) ». Cela signifie restaurer ce qui est à l’origine de la nation française : l’État. « C’est le pouvoir qui devait donc être rétabli ou refait avant toute chose : c’est l’ensemble des moyens d’exécution; c’est l’État. C’est par l’État que la reconstruction française à commencer (p. 23). »

Thierry Maulnier conçoit la Révolution Nationale, on l’a vu, comme la matrice d’un nouvel ordre français. « Il faut créer de nouvelles mœurs, de nouvelles valeurs et de nouveaux modes de pensée (p. 71). » Comment ? Ce qu’il propose convient au fonctionnaire de la propagande à Hanoï qui a classé les textes à sa disposition. « refaire une nation, c’est d’abord se donner les moyens de la refaire. C’est d’abord occuper et réorganiser l’État (p. 22). » l’auteur s’intéresse aux interactions psychiques, sociales et politiques entre le « Chef », l’élite et le peuple. « La nature de l’autorité n’est pas seulement d’accroître la force ou pour mieux dire l’efficacité de ceux qui lui obéissent; elle est de métamorphoser cette force en une force de qualité supérieure (p. 204). » Cependant, « l’autorité elle-même, pour atteindre à toute sa vertu, a besoin à son tour de la collaboration de ceux sur qui elle s’exerce. Elle perd beaucoup de son efficacité, s’il ne lui est donné qu’une obéissance passive et comme inerte (p. 205) ». Cela signifie restaurer ce qui est à l’origine de la nation française : l’État. « C’est le pouvoir qui devait donc être rétabli ou refait avant toute chose : c’est l’ensemble des moyens d’exécution; c’est l’État. C’est par l’État que la reconstruction française à commencer (p. 23). »

![La_face_de_Méduse_du_[...]Maulnier_Thierry_bpt6k3355720d.JPEG](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/01/00/1643598651.JPEG) La Révolution Nationale doit de facto « dès maintenant nous préparer à une paix qui pourrait être pour nous, sin nous n’y prenons garde, plus redoutable que la guerre elle-même (p. 44) ». Il lui assigne donc une tâche ardue : fondre toutes les contradictions nationales dans un seul môle. En effet, « le drame du monde moderne vient de ce que les valeurs dont la composition merveilleuse et l’équilibre sans cesse en mouvement font une société harmonieuse ont commencé de se séparer les unes des autres, de s’exclure les unes les autres avec une fanatique intolérance, de s’amplifier jusqu’au mythe et d’exercer leur ravage anarchique en visant d’une vie monstrueusement indépendante (pp. 52 – 53) ». D’où cette mentalité française qui s’installe facilement dans la routine. « Si les Français se sont montrés inférieurs à d’autres peuples, au cours des cinquante dernières années, ce n’est pas dans la vitalité, ce n’est pas dans le jaillissement des sources créatrices, c’est dans l’organisation, l’utilisation, l’exploitation de leurs ressources. Ils n’ont pas été dépassés dans l’ordre de l’invention scientifique, mais dans celui des applications industrielles (p. 11) ». Il ne pointe pourtant pas la cause pratique de ces échecs répétés : une administration de plus en plus bureaucratique qui freine ou noie toute initiative originale afin de rester dans un moule normatif confortable. Il n’entend pas que la Révolution Nationale s’affadisse ou s’embourbe dans le marais des ministères incapables de se faire obéir de ses fonctionnaires.

La Révolution Nationale doit de facto « dès maintenant nous préparer à une paix qui pourrait être pour nous, sin nous n’y prenons garde, plus redoutable que la guerre elle-même (p. 44) ». Il lui assigne donc une tâche ardue : fondre toutes les contradictions nationales dans un seul môle. En effet, « le drame du monde moderne vient de ce que les valeurs dont la composition merveilleuse et l’équilibre sans cesse en mouvement font une société harmonieuse ont commencé de se séparer les unes des autres, de s’exclure les unes les autres avec une fanatique intolérance, de s’amplifier jusqu’au mythe et d’exercer leur ravage anarchique en visant d’une vie monstrueusement indépendante (pp. 52 – 53) ». D’où cette mentalité française qui s’installe facilement dans la routine. « Si les Français se sont montrés inférieurs à d’autres peuples, au cours des cinquante dernières années, ce n’est pas dans la vitalité, ce n’est pas dans le jaillissement des sources créatrices, c’est dans l’organisation, l’utilisation, l’exploitation de leurs ressources. Ils n’ont pas été dépassés dans l’ordre de l’invention scientifique, mais dans celui des applications industrielles (p. 11) ». Il ne pointe pourtant pas la cause pratique de ces échecs répétés : une administration de plus en plus bureaucratique qui freine ou noie toute initiative originale afin de rester dans un moule normatif confortable. Il n’entend pas que la Révolution Nationale s’affadisse ou s’embourbe dans le marais des ministères incapables de se faire obéir de ses fonctionnaires. Thierry Maulnier pense par conséquent que « la France n’est pas le pays de la mesure : mais elle est, géographiquement, historiquement, socialement, moralement, intellectuellement, le pays de la conciliation des contraires (p. 59) ». Malgré la Débâcle de 1940, le pays vaincu conserve des atouts. Ceux-ci reposent sur sa géographie. L’auteur se lance dans une succincte et pertinente analyse géopolitique qui bouscule la fameuse et sempiternelle dualité Terre – Mer. La « complexité de notre civilisation nous est imposée par notre sol lui-même. Solidement établie au cœur de l’Europe, la France regarde en même temps vers toutes mers, et la géographie l’attache en même temps aux peuples continentaux et aux peuples maritimes qui se disputent en ce moment la prééminence. L’Allemagne n’est qu’européenne (6), l’Angleterre n’est qu’impériale (7) : la France est européenne et impériale en même temps. On en a vu les conséquences dans l’histoire militaire : celle de l’Allemagne n’est guère que terrestre, celle de l’Angleterre n’est guère que marine. Tout au long de son histoire, la France a dû se battre sur terre et sur mer en même temps (pp. 60 – 61) ». Encore de nos jours, l’Hexagone républicain se voit tiraillé entre un projet pseudo-européen germanocentré sous la houlette étatsunienne, une francophonie « grand remplaciste » métisseuse mondialisée et un monde atlantique anglo-saxon auquel il se rattache indirectement par la Normandie et la rémanence territoriale de la Grande Louisiane et de la Nouvelle-France des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles… Terre de contrastes majeurs parce que « continentale et maritime, agricole et urbaine, européenne et impériale, nationaliste et humaniste, unitaire et régionaliste, religieux et rationaliste (8), particulariste et cosmopolite, pacifique et guerrière, la France concentre en elle toutes les contradictions de l’univers et a fait sa civilisation et sa vie, passablement heureuse et glorieuse au cours des siècles, de ces mêmes contradictions (p. 65) ».

Thierry Maulnier pense par conséquent que « la France n’est pas le pays de la mesure : mais elle est, géographiquement, historiquement, socialement, moralement, intellectuellement, le pays de la conciliation des contraires (p. 59) ». Malgré la Débâcle de 1940, le pays vaincu conserve des atouts. Ceux-ci reposent sur sa géographie. L’auteur se lance dans une succincte et pertinente analyse géopolitique qui bouscule la fameuse et sempiternelle dualité Terre – Mer. La « complexité de notre civilisation nous est imposée par notre sol lui-même. Solidement établie au cœur de l’Europe, la France regarde en même temps vers toutes mers, et la géographie l’attache en même temps aux peuples continentaux et aux peuples maritimes qui se disputent en ce moment la prééminence. L’Allemagne n’est qu’européenne (6), l’Angleterre n’est qu’impériale (7) : la France est européenne et impériale en même temps. On en a vu les conséquences dans l’histoire militaire : celle de l’Allemagne n’est guère que terrestre, celle de l’Angleterre n’est guère que marine. Tout au long de son histoire, la France a dû se battre sur terre et sur mer en même temps (pp. 60 – 61) ». Encore de nos jours, l’Hexagone républicain se voit tiraillé entre un projet pseudo-européen germanocentré sous la houlette étatsunienne, une francophonie « grand remplaciste » métisseuse mondialisée et un monde atlantique anglo-saxon auquel il se rattache indirectement par la Normandie et la rémanence territoriale de la Grande Louisiane et de la Nouvelle-France des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles… Terre de contrastes majeurs parce que « continentale et maritime, agricole et urbaine, européenne et impériale, nationaliste et humaniste, unitaire et régionaliste, religieux et rationaliste (8), particulariste et cosmopolite, pacifique et guerrière, la France concentre en elle toutes les contradictions de l’univers et a fait sa civilisation et sa vie, passablement heureuse et glorieuse au cours des siècles, de ces mêmes contradictions (p. 65) ». Espérant que « la structure économique de la France de demain sera corporative (p. 119) », Thierry Maulnier se plaît à souligner au nom d’une future et éventuelle convergence des révolutionnaires nationaux de « droite » et des révolutionnaires sociaux de « gauche » que « l’opposition légitimiste approuva les révoltes ouvrières contre la monarchie bourgeoise et libérale de Louis-Philippe (p. 121) ». Parce que « la Révolution Nationale n’est pas le régime de la facilité : elle demande et doit demander à chacun la patience dans l’effort et le sacrifice (p. 139) », son rôle « est précisément d’arracher le travail à cette dégradation qu’il subit dans l’exploitation capitaliste et dans les réactions qu’elle provoque (p. 137) » en s’appuyant sur un corporatisme renaissant à expérimenter. Il est clair qu’« anticapitaliste, [la Révolution Nationale] ne se confond ni avec la réaction patriarcale ni avec la révolution prolétarienne. […] Elle est la révolution d’une société qui ne se renie pas pas, mais obéit à sa loi interne d’un présent qui ne transforme le passé que pour l’accomplir (pp. 124 – 125) ». N’est-ce pas la définition exacte d’une révolution conservatrice ?

Espérant que « la structure économique de la France de demain sera corporative (p. 119) », Thierry Maulnier se plaît à souligner au nom d’une future et éventuelle convergence des révolutionnaires nationaux de « droite » et des révolutionnaires sociaux de « gauche » que « l’opposition légitimiste approuva les révoltes ouvrières contre la monarchie bourgeoise et libérale de Louis-Philippe (p. 121) ». Parce que « la Révolution Nationale n’est pas le régime de la facilité : elle demande et doit demander à chacun la patience dans l’effort et le sacrifice (p. 139) », son rôle « est précisément d’arracher le travail à cette dégradation qu’il subit dans l’exploitation capitaliste et dans les réactions qu’elle provoque (p. 137) » en s’appuyant sur un corporatisme renaissant à expérimenter. Il est clair qu’« anticapitaliste, [la Révolution Nationale] ne se confond ni avec la réaction patriarcale ni avec la révolution prolétarienne. […] Elle est la révolution d’une société qui ne se renie pas pas, mais obéit à sa loi interne d’un présent qui ne transforme le passé que pour l’accomplir (pp. 124 – 125) ». N’est-ce pas la définition exacte d’une révolution conservatrice ?

L’année 1968 sera marquée par un enchaînement de révoltes partout sur le globe : dans le camp occidental, des États-Unis au Japon, en passant par la France ou l’Italie mais aussi dans certains pays du pacte de Varsovie, comme en Pologne ou en Tchécoslovaquie. L’ensemble de l’ordre du monde bipolaire capital-communiste issu de Yalta et du tribunal de Nuremberg allait être ainsi traversé dans un même élan par une série de révoltes marquées par le choc des générations. Pourtant, l’irruption soudaine de cette contestation étudiante internationale n’était pas le fruit du hasard mais bien celui d’un long travail d’incubation intellectuel et politique commencé il y a plusieurs décennies et qui connaîtrait son paroxysme dans les années d’après-guerre. Comme si des forces trop longtemps contenues et désormais sans frein se frayaient maintenant un chemin vers la surface et chercher à tout emporter avec l’éclatante et audacieuse énergie de la jeunesse. Les forces de l’ « Eros » déchaînées, chères aux théoriciens du freudo-marxisme.

L’année 1968 sera marquée par un enchaînement de révoltes partout sur le globe : dans le camp occidental, des États-Unis au Japon, en passant par la France ou l’Italie mais aussi dans certains pays du pacte de Varsovie, comme en Pologne ou en Tchécoslovaquie. L’ensemble de l’ordre du monde bipolaire capital-communiste issu de Yalta et du tribunal de Nuremberg allait être ainsi traversé dans un même élan par une série de révoltes marquées par le choc des générations. Pourtant, l’irruption soudaine de cette contestation étudiante internationale n’était pas le fruit du hasard mais bien celui d’un long travail d’incubation intellectuel et politique commencé il y a plusieurs décennies et qui connaîtrait son paroxysme dans les années d’après-guerre. Comme si des forces trop longtemps contenues et désormais sans frein se frayaient maintenant un chemin vers la surface et chercher à tout emporter avec l’éclatante et audacieuse énergie de la jeunesse. Les forces de l’ « Eros » déchaînées, chères aux théoriciens du freudo-marxisme.

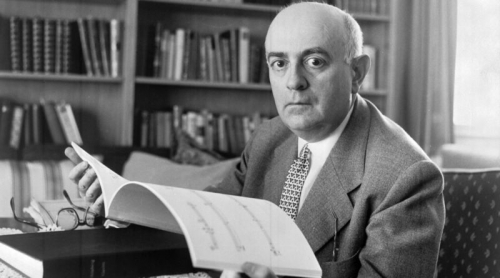

Relire aujourd’hui les Études sur la personnalité autoritaire de Theodor W. Adorno et de l’Institut de Recherche Social se révèle très instructif pour comprendre d’où provient une grande partie du mal-être et de la mauvaise conscience qui mine l’Occident contemporain. On y découvre l’application méthodique et clinique de penseurs politiques engagés qui se sont arrogés le droit de déterminer ce qui est moral ou non, non seulement dans l’Histoire et la culture de l’Occident mais jusque dans l’inconscient supposé des populations occidentales afin de l’en extirper comme par un acte psycho-chirurgical.

Relire aujourd’hui les Études sur la personnalité autoritaire de Theodor W. Adorno et de l’Institut de Recherche Social se révèle très instructif pour comprendre d’où provient une grande partie du mal-être et de la mauvaise conscience qui mine l’Occident contemporain. On y découvre l’application méthodique et clinique de penseurs politiques engagés qui se sont arrogés le droit de déterminer ce qui est moral ou non, non seulement dans l’Histoire et la culture de l’Occident mais jusque dans l’inconscient supposé des populations occidentales afin de l’en extirper comme par un acte psycho-chirurgical.

On sait que ces « valeurs », que l’on dit découler de la nature humaine, en fait, plus certainement, des délires philosophistes du XVIIIe siècle, sont celles qui charpentent le « pacte républicain », contrat social de la République dite « française ». Grâce au contrat social, ou pacte républicain, une société peut s’organiser et fonctionner avec des hommes venus du monde entier puisque les valeurs et principes qui président à cette organisation et à ce fonctionnement découlent de l’universelle nature humaine, et non de telle ou telle culture particulière. Ainsi une société fondée sur les droits naturels de l’Homme (le droit à la liberté, à l’égalité, à la propriété) serait acceptable par tous puisque ne contredisant les aspirations essentielles d’aucun. Les joueurs de pipo avaient simplement oublié de définir ce qu’on entendait par « liberté », « égalité » ou « propriété »…

On sait que ces « valeurs », que l’on dit découler de la nature humaine, en fait, plus certainement, des délires philosophistes du XVIIIe siècle, sont celles qui charpentent le « pacte républicain », contrat social de la République dite « française ». Grâce au contrat social, ou pacte républicain, une société peut s’organiser et fonctionner avec des hommes venus du monde entier puisque les valeurs et principes qui président à cette organisation et à ce fonctionnement découlent de l’universelle nature humaine, et non de telle ou telle culture particulière. Ainsi une société fondée sur les droits naturels de l’Homme (le droit à la liberté, à l’égalité, à la propriété) serait acceptable par tous puisque ne contredisant les aspirations essentielles d’aucun. Les joueurs de pipo avaient simplement oublié de définir ce qu’on entendait par « liberté », « égalité » ou « propriété »…