Article paru dans Alkemie Revue semestrielle de littérature et philosophie, numéro 9 / Juin 2012 (thème: L’être)

Abstract: This article suggests approaching the problem of the birth in Cioran. By interpreting the fall from Heaven as the exile, Cioran aims at subtracting the narrative of the Genesis from the moral dialectic innocence/fault towards God, to conjugate it with the profound intuitions on the consciousness of the Zen Buddhism.

L’esprit humain n’est pas la pensée, mais le vide et la paix

qui forment le fond et la source de la pensée.

Houeï-nêng

Être homme signifie précisément être conscient. Être détaché de soi-même, en fuite perpétuelle de ce qu’on est, pour saisir ce qu’on n’est pas.

Bien avant d’être le sujet d’un livre ou d’un article, la naissance a été pour Cioran surtout une obsession, dont il ne s’est jamais libéré. S’acharner contre sa propre venue au monde… Comment une telle folie serait-elle concevable ? Pourquoi donc se vouer à une cause déjà perdue d’avance ? À quoi bon se tourmenter avec l’Insoluble ? En effet, au moment même où nous discutons de la naissance, il est déjà trop tard : « Ne pas naître est sans contredit la meilleure formule qui soit. Elle n’est malheureusement à la portée de personne »[1]. Le forfait, à vrai dire, est désormais accompli, cependant s’arrêter sur cet événement capital n’est pas une occupation oisive, au contraire, car elle pourrait bien se révéler une expérience libératrice.

En glissant sur le problème de la naissance, le Christianisme perdit ab initio l’essentiel de la Genèse transmis par la tradition. Le Bouddhisme, au contraire, en fit l’un des points fondamentaux de sa doctrine. Quant à Cioran, son interprétation magistrale du récit de la Genèse, vise à le soustraire à la dialectique morale innocence/culpabilité envers Dieu, pour le conjuguer avec les profondes intuitions du bouddhisme Zen.[2]

- L’exil de la conscience

Au-delà du langage mythique, la chute originaire du Paradis raconte le drame de la conscience, la tentation du savoir qui se révèlera être fatale à l’homme. Effectivement, botaniste exécrable, l’homme opta pour le faux arbre: il préféra l’arbre de la Connaissance à celui de la Vie. On lit alors dans la Bible : « ses yeux se sont ouverts ». Royaume de l’évidence inarticulée, « le Paradis était l’endroit où l’on savait tout mais où l’on n’expliquait rien. L’univers d’avant le péché, d’avant le commentaire… »[3], glose Cioran. L’avènement de la conscience établit donc une fracture, une discontinuité dans l’économie de l’être. L’individu naît donc comme une entité séparée psychiquement de son milieu. Cioran rappelle distinctement l’épisode de son enfance qui marqua en lui le réveil de la conscience, par laquelle il entendit, pour la première fois, le poids d’être au monde.

Tout à coup, je me trouvai seul devant… Je sentis, en cet après-midi de mon enfance, qu’un événement très grave venait de se produire. Ce fut mon premier éveil, le premier indice, le signe avant-coureur de la conscience. Jusqu’alors je n’avais été qu’un être. À partir de ce moment, j’étais plus et moins que cela. Chaque moi commence par une fêlure et une révélation.[4]

En nommant les êtres vivants et les choses, l’homme crée une opposition entre soi et le monde. En vertu d’un savoir purement abstrait et par la médiation logique de l’idée, il s’imagine pouvoir reconstituer l’unité originaire du réel, en gouvernant ainsi le devenir. En vain. Car il ne fera qu’agrandir de plus en plus le gouffre qui le sépare du sein de la Nature. « Au plus intime de lui-même, l’homme aspire à rejoindre la condition qu’il avait avant la conscience. L’histoire n’est que le détour qu’il emprunte pour y parvenir. »[5]

Naturellement intentionnelle, la conscience est toujours conscience-de-quelque-chose. En établissant la distinction originaire entre soi-même et l’autre, la conscience structure l’expérience en un sens dualiste (sujet vs objet), conformément à la logique discursive de l’intellect. De cette façon l’ontologie de la substantia, qui classifie les organismes en vertu de leur différence essentielle, se superpose à l’interdépendance primordiale (relatio) de tous les phénomènes, où ceux-ci sont le produit momentané d’un réseau de conditionnements réciproques entre éléments dépourvus de nature propre. Ce faisant l’homme, ce « transfuge de l’être »[6], accomplit un saut en dehors du flux vital où il était immédiatement plongé, hors de l’inconscience d’un éternel présent qui le tenait à l’abri, sinon de la mort – l’arbre de la Vie lui était quand même interdit – au moins de la mortalité.

Auparavant il mourait sans doute, mais la mort, accomplissement dans l’indistinction primitive, n’avait pas pour lui le sens qu’elle a acquis depuis, ni n’était chargée des attributs de l’irréparable. Dès que, séparé du Créateur et du crée, il devint individu, c’est-à-dire fracture et fissure de l’être, et que, assumant son nom jusqu’à la provocation, il sut qu’il était mortel, son orgueil s’en agrandit, non moins que son désarroi.[7]

Il en découle une fuite en avant désespérée, à corps perdu, vers l’extérieur, vers l’histoire, pour exorciser cette peur de mourir qui fait corps avec son premier instant. La conscience d’être hic et nunc et la conscience de sa propre mortalité se soutiennent réciproquement, ce sont le recto et le verso de de la même médaille. Le cercle vicieux dans lequel l’homme est tombé depuis Adam, est déterminé par la prétention de se sauver consciemment de la catastrophe de la conscience, en se sauvant à la manière de Munchausen, qui tire sur ses propres cheveux. Une telle ambition équivaut à « refaire l’Éden avec les moyens de la chute »[8]. Si « naître c’est s’attacher »[9], intentionnellement ou non, à notre moi et aux choses du monde, pour en sortir il faut parcourir à reculons le chemin, « faire éclater les catégories où l’esprit est confiné »[10], rétablir la condition originaire antérieure à la dichotomie sujet-objet. Autrement dit, il faut renaître sous l’arbre de la Vie.

L’inconscience est le secret, le « principe de vie » de la vie. Elle est l’unique recours contre le moi, contre le mal d’être individualisé, contre l’effet débilitant de l’état de conscience, état si redoutable, si dur à affronter, qu’il devrait être réservé aux athlètes seulement.[11]

- Le visage originaire avant la naissance

L’état d’inconscience évoqué par Cioran n’a rien à voir avec l’inconscient de la psychanalyse. Pour Cioran il s’agit donc de révéler les convergences surprenantes de cette inconscience avec ce que le bouddhisme Zen, dans ses différents courants, définit parfois comme : Nature-Bouddha, non-esprit (Wu-hsin), non-pensée (Wu-nien), « visage originaire avant la naissance » (pien-lai mien-mu), non-né (fusho).[12] Cioran même décrit la délivrance comme « état de non-pensée »[13] et il envisage d’écrire un essai à propos de cette condition.[14]

Cette concordance n’est pas le fruit du hasard. À partir des années 1960 – comme en témoignent les Cahiers – Cioran montre un intérêt croissant pour l’interprétation pragmatique du bouddhisme élaborée par le Zen. La virulence anti-métaphysique, typique de la tradition chinoise et japonaise, se marie à merveille avec son anti-intellectualisme viscéral.

Conversant avec un chinois de Hong-Kong, Cioran partage avec lui la méfiance vers la philosophie occidentale « qu’il trouve verbeuse, superficielle, extérieure, car dépourvue de réalité, de pratique ».[15] À un moment donné Cioran arrivera à définir Mozart et le Japon comme « les résultats les plus exquis de la Création ».[16] Charmé par la délicatesse nippone, il recopiera une page entière du livre de Gusty Herrigel sur l’Ikebana, ou « l’art d’arranger les fleurs ».[17] Pendant l’hiver 1967, Cioran ressentira une pitié authentique pour les fleurs de son balcon, exposées au froid intense, au point de les emmener avec soin dans sa mansarde pour les protéger.[18]

Chez Cioran, le refus de la conscience n’est rien d’autre que « la nostalgie de ce temps d’avant le temps »[19] où le bonheur consistait dans un « regard sans réflexion ».[20] Parce qu’elle perturbe la spontanéité du geste, l’activité consciente fausse la vie. Préfigurant un but à atteindre, l’esprit se scinde en spectateur et en acteur, et se place à la fois dans et hors de l’action. Le geste s’accomplit donc dans un état de tension, d’effort conscient, car l’esprit est troublé par les conséquences possibles de son action à venir.

Toute activité consciente gêne la vie. Spontanéité et lucidité sont incompatibles.

Tout acte essentiellement vital, dès que l’attention s’y applique, s’accomplit avec peine et laisse après soi une sensation d’insatisfaction.

L’esprit joue par rapport aux phénomènes de la vie le rôle d’un trouble-fête.

L’état d’inconscience est l’état naturel de la vie, c’est en lui qu’elle est chez elle, qu’elle prospère et qu’elle connaît le sommeil bienfaisant de la croissance. Dès qu’elle se réveille, dès qu’elle veille surtout, elle devient haletante et oppressée, et commence à s’étioler.[21]

Le Zen, dont l’esprit imprègne tous les arts japonais, reconduit l’homme à la réalité du hic et nunc, à l’« ainsité » (tathata)[22]. Afin de se syntoniser sur la longueur d’onde de la vie, il faut que le geste de l’artiste, comme du samouraï d’ailleurs, soit spontané, sans hésitations ; il faut que le geste surgisse du vide de la pensée, en oubliant aussi la technique apprise. Autrement dit, il faut que l’art soit à tel point intériorisée jusqu’à devenir connaissance du corps, en sorte que celui-ci puisse réagir à la situation de manière autonome et instantanée, en éludant la direction de la conscience. Seulement si la technique (waza), l’énergie vitale (Ki) et l’esprit (shin), sont fusionnés harmonieusement, sans que l’une prévale sur les autres, l’action résulte efficace et opportune. Comme une balle flottant dans une rivière, portée par le courant, l’esprit doit couler sans s’arrêter sur rien[23]. À ce propos D.T. Suzuki soutient que

La vie se dessine de soi sur la toile nommé le temps – et le temps ne se répète jamais, une fois passé il ne revient plus. Il en est de même pour l’acte : une fois accompli, il ne peut plus être défait. La vie est comme la peinture nommée sumi-e, qui est peinte d’un seul jet, sans hésitations, sans intervention de l’intellect, sans corrections. La vie n’est pas comme une peinture à l’huile qu’on peut effacer et retoucher jusqu’à ce que l’artiste en soit satisfait. Dans la peinture sumi-e chaque coup de pinceau qu’on passe une deuxième fois devient une tache, il n’a plus rien de vivant […] Et il en est de même pour la vie. Ce qu’elle est devenue par notre action nous ne pouvons plus le reprendre, ou mieux nous ne pouvons même plus effacer pas ce qui est passé à travers notre conscience simplement. Ainsi le Zen doit être cueilli pendant que la chose arrive, ni avant ni après : dans l’instant.[24]

Avec perspicacité, Cioran établit une corrélation directe entre l’immédiat et le réel, d’un côté, et la souffrance et la conscience de l’autre. Takuan Sōhō lui fait écho, lorsqu’il affirme que « Dans le bouddhisme nous détestons cet arrêt, cet hésitation de l’esprit sur l’une ou l’autre chose, que nous définissons comme étant la souffrance » [25]. L’excès d’auto-conscience fait de l’homme un système hautement instable, sensible aux moindres sollicitations du milieu, aussi bien extérieur qu’intérieur. Cela crée un état d’anxiété, d’oscillation entre contraires, qui retarde l’agir ou le rend gêné et inefficace. L’obsession du contrôle, le besoin spasmodique de sûreté et de certitudes préventives, sont autant de témoignages montrant que l’homme est sorti de la spontanéité de la vie, et qu’il vit dans un état d’agitation fiévreuse, incapable de concilier la réalité du vécu avec l’idée qu’il a élaboré a priori. Entre les espèces vivantes, l’homme est le plus souffrant, car il est parvenu au plus haut degré de conscience de soi.

Il vaut mieux être animal qu’homme, insecte qu’animal, plante qu’insecte, et ainsi de suite. Le salut ? Tout ce qui amoindrit le règne de la conscience et en compromet la suprématie.[26]

Alors, comme peut-on retrouver en soi-même cette « virginité ‘‘métaphysique’’ »[27], qui permet de percevoir les éléments comme si on les voyait pour la première fois, « au lendemain de la Création »[28] et « avant la Connaissance »[29] ? Il faut avant tout discerner la vacuité intrinsèque des choses, des mots qui les désignent et, finalement, de la conscience du moi empirique. Autrement dit, il faut démolir complètement la conception ordinaire de la réalité, en même temps que l’armature logique qui la soutient.

Les maîtres Zen étaient harcelés par leurs élèves, à propos de questions sur l’essence dernière du bouddhisme. Pour arrêter chez les novices le flux de la pensée discursive, les maîtres Zen adoptèrent une série de stratégies, soit verbales soit physiques, telles que : le kōan, le paradoxe, la contradiction, le cri, le coup de bâton, le gifle, l’indication directe… Cette pars destruens du Zen vise à provoquer un choc psychologique, un court-circuit intellectuel, jusqu’à ce que « le langage soit réduit au silence et la pensée n’ait aucune voie à suivre » .[30] Il faut tuer dans l’œuf chaque tentative de fuite de la réalité vers le symbolique. Interroger le maître, c’est encore croire à la connaissance objective, doctrinale, séparée de l’ignorance ; c’est détourner l’attention de soi-même, c’est sacrifier sur l’autel d’un absolu métaphysique l’instant éternel qu’on vit. De ce point de vue, le kōan peut être considéré comme un paradigme de la vie elle-même, dont la complexité ne demande pas une compréhension simplement intellectuelle, mais toujours existentielle, vécue complètement dans l’instant.

Pour éviter tout cela, le Zen invite à expérimenter le Néant, c’est-à-dire le stade où on arrive à reconnaître que « les montagnes ne sont plus des montagnes »[31] (A n’est pas A), où les choses, en perdant leur essence et leurs déterminations, glissent vers le vide. Suzuki à ce propos soutient que « le Zen est une philosophie de négations absolues qui sont en même temps affirmation absolues » .[32] Cioran aussi répondit dans ces termes à une question sur son côté nihiliste

Je suis sûrement un négateur, mais ma négation n’est pas une négation abstraite, donc un exercice ; c’est une négation qui est viscérale, donc affirmation malgré tout, c’est une explosion ; est-ce qu’une gifle est une négation ? Donner une gifle n’est-ce pas… c’est une affirmation, mais ce que je fais ce sont des négations qui sont des gifles, donc ce sont des affirmations.[33]

Ce que les critiques occidentaux interprètent de manière expéditive, chez Cioran, comme étant du nihilisme, du pessimisme, est en réalité une tentative extrême pour emmener le lecteur – et peut-être lui-même – en face de son propre néant, afin que l’esprit, vidé de tout contenu, puisse retourner à la surface des choses, en se réveillant à la perception pure de toute réflexion. « Le véritable bonheur, c’est l’état de conscience sans référence à rien, sans objet, où la conscience jouit de l’immense absence qui la remplit. »[34).

- La châtaigne et le satori

Que Cioran le sache ou non, quand il soutient que « connaître véritablement, c’est connaître l’essentiel, s’y engager, y pénétrer par le regard et non par l’analyse ni par la parole », il nous fournit une définition du satori, ou connaissance intuitive, non duale, transcendante, qui recueille instantanément la nature de la réalité. Sur ce point, D. T. Suzuki précise :

Le satori peut être défini comme une pénétration intuitive de la nature des choses, par opposition à leur compréhension analytique ou logique. Pratiquement, il comporte le déploiement devant nous d’un nouveau monde, jamais perçu auparavant à cause de la confusion de notre esprit orienté de façon dualiste. On peut dire de plus que, par le satori, tout ce qui nous entoure nous apparaît selon une perspective insoupçonnée.[35]

Regarder sa nature originaire n’est jamais le résultat d’une pratique méditative, et encore moins le contenu d’une connaissance transmissible. Une fois que notre esprit est engorgé de notions conceptuelles, il se trouve bloqué par le Grand Doute ; dès lors, un événement quelconque, même le plus insignifiant, est à même d’éveiller la conscience.

C’est d’ailleurs ce que connut Hsiang-yen (? -898), élève de Kuei-shan. Le maître lui demanda quel était son visage originaire d’avant la naissance, mais Hsiang-yen ne répondit pas. Dans l’espoir de trouver la réponse à son kōan, il compulsa en vain tous ses livres. Alors, dans un accès de colère, il brûla tous les textes, bien qu’il continuât à se tourmenter au sujet de ce problème insoluble. Un jour, pendant qu’il arrachait les mauvaises herbes du terrain, il heurta une pierre laquelle, par ricochet, frappa à son tour une canne de bambou : c’est ainsi que Hsiang-yen obtint son satori.[36] Même Cioran expérimente un état d’âme identique, lorsqu’il écrit :

Comme je me promenais à une heure tardive dans cette allée bordée d’arbres, une châtaigne tomba à mes pieds. Le bruit qu’elle fit en éclatant, l’écho qu’il suscita en moi, et un saisissement hors de proportion avec cet incident infime, me plongèrent dans le miracle, dans l’ébriété du définitif, comme s’il n’y avait plus de questions, rien que des réponses. J’étais ivre de mille évidences inattendues, dont je ne savais que faire…

C’est ainsi que je faillis avoir mon satori. Mais je crus préférable de continuer ma promenade[37].

Au-delà du mot adopté et de l’ironie finale, il n’y a pas de doute que l’expérience rappelle une expression clé de l’esthétique japonaise, ce mono no aware qui désigne un certain « pathos (aware) des choses (mono) », c’est-à-dire le sentiment ressenti par l’observateur face à la beauté éphémère des phénomènes, lorsque il est pénétré par la brève durée d’une telle splendeur, destinée à s’évanouir de même que celui qui la contemple est voué à disparaître.[38] Ce n’est pas par hasard que, entre les sens du mot aware, on peut trouver celui de compassion, dans le sens étymologique de cum-patire, de souffrir ensemble, qui rapproche l’homme du reste de la nature, liés par un même destin fugace. En reprenant dans les Cahiers l’épisode de la châtaigne, Cioran souligne justement cette vérité métaphorique

Tout à l’heure, en faisant ma promenade nocturne, avenue de l’Observatoire, une châtaigne tombe à mes pieds. « Elle a fait son temps, elle a parcouru sa carrière », me suis-je dit. Et c’est vrai : c’est de la même façon qu’un être achève sa destinée. On mûrit, et puis on se détache de l’« arbre » [39]

Il est symptomatique qu’ailleurs, pour désigner ce clair obscur de l’âme, Cioran utilise une expression typique de l’esthétique japonaise, employée lorsqu’on perçoit « le ah ! des choses »[40]. Ce soupir évocateur, en saisissant la nature impermanente de la vie, indique un sentiment inexplicable de plaisir subtil, imprégné d’amertume, devant chaque merveille qu’on sait périssable. Si d’un côté telle disposition dévoile le côté mélancolique de l’existence, d’un autre côté, il en émane un certain charme du monde qui, en dernière analyse, ne mène pas à la résignation, mais confère un sursaut de vitalité à l’âme de l’observateur.[41]

Le spectacle de ces feuilles si empressées à tomber, j’ai beau l’observer depuis tant d’automnes, je n’en éprouve pas moins chaque fois une surprise où «le froid dans le dos » l’emporterait de loin sans l’irruption, au dernier moment, d’une allégresse dont je n’ai pas encore démêlé l’origine.[42]

Ce sentiment, par les traits morbides de la Vergänglichkeit, ou de la caducité universelle, revient dans toute une série d’impressions notées dans les Cahiers. En maintes occasions Cioran montre qu’il a éprouvé l’expérience du vide mental, de dépouillement intérieur, qui aboutit à une perception absolue de la réalité. De même que le peintre zen se fait creux pour accueillir l’événement qu’il va représenter, pour devenir lui même la chose contemplée, de même, Cioran propose de se rendre totalement passif comme un « objet qui regarde »[43] : « l’idée, chère à la peinture chinoise, de peindre une forêt ‘‘telle que la verraient les arbres’’… ».[44] Du reste, c’est seulement ainsi qu’il est possible de « remonter avant le concept, [d’]écrire à même les sens ».[45] Autrement dit, il faut « Écarter la pensée, se borner à la perception. Redécouvrir le regard et les objets, d’avant la Connaissance ».[46] Le 25 décembre 1965, il note :

Le bonheur tel que je l’entends : marcher à la campagne et regarder sans plus, m’épuiser dans la pure perception.[47]

La contemplation permet de retrouver la dimension éternelle du présent, non contaminée par les fantômes du passé et par les anxiétés de l’avenir. Être entièrement dans un fragment de temps, totalement absorbé par le « hic et nunc » que nous sommes en train de vivre, car, en dehors de l’instant opportun, tout est illusion.

Autrefois un moine demanda à Chao-chou (778-897), un des plus grands maîtres Zen : « Dis-moi, quel est le sens de la venue du Premier Patriarche de l’Ouest ? »[48] Chao-chou répondit : « Le cyprès dans la cour ! » [49] Or, si pour le sens commun la réponse semble totalement insensée, en revanche, dans l’optique Zen, elle ne l’est pas. Chao-chou soustrait le moine à la métaphysique aride de la pensée discursive, pour le reconduire à la poésie vivante de la réalité. À ce moment-là le cyprès recèle en lui-même le monde entier, bien plus que la réponse doctrinale attendue par le moine. Chao-chou et le moine, dans leur perception immédiate, sont le cyprès. L’être, dans sa nature indifférenciée, se révèle comme VOIR le cyprès. Cioran n’est pas loin de la spiritualité Zen lorsqu’il affirme :

Marcher dans une forêt entre deux haies de fougères transfigurées par l’automne, c’est cela un triomphe. Que sont à côtés suffrages et ovations ? [50]

Ailleurs Cioran parle du vent en tant qu’ « agent métaphysique »[51], révélateur donc de réalités inattendues : écouter le vent « dispense de la poésie, est poésie ».[52] L’insomnie et les réveils brusques au cœur de la nuit, le comblèrent souvent de visions ineffables, d’une béatitude paradisiaque.

Insomnie à la campagne. Une fois, vers 5 heures du matin, je me suis levé pour contempler le jardin. Vision d’Éden, lumière surnaturelle. Au loin, quatre peupliers s’étiraient vers Dieu.[53]

Durant l’été 1966, à Ibiza, après une énième veillée nocturne, c’est encore la beauté déchirante du paysage qui déjoue les sombres résolutions suicidaires.

Ibiza, 31 juillet 1966. Cette nuit, réveillé tout à fait vers 3 heures. Impossible de rester davantage au lit. Je suis allé me promener au bord de la mer, sous l’impulsion de pensées on ne peut plus sombres. Si j’allais me jeter du haut de la falaise ? […] Pendant que je faisais toute sorte de réflexions amères, je regardai ces pins, ces rochers, ces vagues « visités » par la lune, et sentis soudain à quel point j’étais rivé à ce bel univers maudit.[54]

Un autre aspect qui rapproche Cioran du Zen, réside dans une prise de conscience : la vie authentique est propre au cioban, au rustique qui vit au contact de la nature et qui gagne sa vie par le travail manuel[55]. Les années d’enfance, passées en tant qu’« enfant de la nature »[56], « Maître de la création »[57] dans la campagne transylvanienne, ont certainement été comme un imprinting pour Cioran, cependant même le Cioran adulte expérimente en maintes occasions ce qu’il appelle « le salut par les bras ».[58] Il va jusqu’à sanctifier la fatigue physique, car, en abolissant la conscience, elle empêche l’inertie mentale qui aboutit au cafard.[59] Finalement, il caresse un rêve :

avoir une «propriété », à une centaine de kilomètres de Paris, où je pourrais travailler de mes mains pendant deux ou trois heures tous les jours. Bêcher, réparer, démolir, construire, n’importe quoi, pourvu que je sois absorbé par un objet quelconque – un objet que je manie. Depuis des années déjà, je mets ce genre d’activité au-dessus de toutes les autres ; c’est elle seule qui me comble, qui ne me laisse pas insatisfait et amer, alors que le travail intellectuel, pour lequel je n’ai plus de goût (bien que je lise toujours beaucoup, mais sans grand profit), me déçoit parce qu’il réveille en moi tout ce que je voudrais oublier, et qu’il se réduit désormais à une rencontre stérile avec des problèmes que j’ai abordés indéfiniment sans les résoudre.[60]

D’après le Zen, l’esprit quotidien est la Voie (chinois : Tao, japonais : Do). Donc, soutient Lin-tsi, il n’y a rien de spécial à faire (wu-shih) : « allez à la selle, pissez, habillez-vous, mangez, et allongez-vous lorsque vous êtes fatigués. Les fous peuvent rire de moi, mais les sages savent ce que je veux dire ». [61] Les maîtres Zen, sans différences de rang, s’occupaient des champs, du ménage, préparaient les repas, de telle sorte qu’aucun travail manuel n’était pour eux humiliant. Pendant ces activités, ils donnaient leçons pratiques aux disciples ou bien ils répondaient à leurs interlocuteurs de manière tranchante…

Chao-chou était occupé à nettoyer lorsque survint le ministre d’État Liu, qui, en le voyant si occupé, lui demanda : « Comment se fait-il qu’un grand sage, comme vous, balaye la poussière ? » « La poussière vient d’ailleurs », répondit promptement Chao-chou. Une fois reconquise l’esprit originaire, alors chaque chose, même la plus prosaïque, s’illumine d’immensité : « Faculté miraculeuse et merveilleuse activité ! / Je tire l’eau du puits et fends le bois ! ».[62]

- Tuer le Bouddha

Afin de voir le visage originaire qui précède la naissance, il nous faut encore surmonter un dernier obstacle, peut-être le plus ardu, puisqu’il s’agit de la sainte figure de l’Éveillé, le Bouddha même. S’il est vrai que, comme l’écrit le dernier Cioran, « Tant qu’il y aura encore un seul un dieu debout, la tâche de l’homme ne sera pas finie »[63], alors le Zen a accompli sa mission depuis longtemps. Il y a mille deux cents ans, Lin-tsi exhorta ses disciples à ne rien chercher en dehors de soi-même, ni le Dharma, ni le Bouddha, ni aucune pratique ou illumination. Il ne faut seulement avoir une infinie confiance dans ce qu’on vit à chaque instant, le reste est une fuite illusoire de l’esprit qu’il faut éviter à tout prix. C’est comme si nous avions une autre tête au-dessus de celle-là que nous portons déjà.

Disciples de la Voie, si vous voulez percevoir le Dharma en sa réalité, simplement ne vous faites pas tromper par les opinions illusoires des autres. Peu importe ce que vous rencontriez, soit au-dedans soit au dehors, tuez-le immédiatement : en rencontrant un bouddha tuez le bouddha, en rencontrant un patriarche tuez le patriarche, en rencontrant un saint tuez le saint, en rencontrant vos parents tuez vos parents, en rencontrant un proche tuez votre proche, et vous atteindrez l’émancipation. En ne vous attachant pas aux choses, vous les traversez librement.[64]

Cioran talonne Lin-tsi sur cette voie, lorsqu’ il affirme qu’ « être rivé à quelqu’un, fût-ce par admiration, équivaut à une mort spirituelle. Pour se sauver, il faut le tuer, comme il est dit qu’il faut tuer le Bouddha. Être iconoclaste est la seule manière de se rendre digne d’un dieu ».[65] Moines qui crachent sur l’image du Bouddha[66] ou qui en brûlent la statue de bois pour se réchauffer, l’utilisation des écritures sacrées comme papier hygiénique, etc. : là où les autres confessions ne voient que sacrilèges, le zen voit des actes vénérables. Une telle fureur iconoclaste se révèle plus nécessaire que jamais, puisque implique une pratique de la vacuité universelle. L’invitation de Lin-tsi à nous allonger, sans attachement, sur la réalité des phénomènes, détruit à la racine n’importe quelle séparation entre sacré et profane, entre nirvāna et samsāra, entre illumination et ignorance. Cioran l’a bien compris, lorsqu’il nous exhorte à « Aller plus loin encore que le Bouddha, s’élever au-dessus du nirvâna, apprendre à s’en passer…, n’être plus arrêté par rien, même par l’idée de délivrance, la tenir pour une simple halte, une gêne, une éclipse… ».[67]

L’élégance suprême et paradoxale du Zen, ce qui le rend supérieur à n’importe quelle autre expérience spirituelle, c’est sa capacité, après avoir tout démoli, à se démolir lui-même, tranquillement. Une fois « plongé » dans la littérature Zen, et après en avoir assimilé la leçon, Cioran flaire le danger et comprend que le moment est venu de s’en détacher. L’expérience de la vacuité doit provenir de soi-même, de ses sensations : « Sur le satori, on ne lit pas ; on l’attend, on l’espère ».[68]

« Les montagnes sont de nouveau des montagnes, les eaux de nouveau des eaux »… à quoi bon s’efforcer d’obtenir quelque chose ?

Le spectacle de la mer est plus enrichissant que l’enseignement du Bouddha.[69]

NOTES:

[1] Cioran, De l’inconvénient d’être né, in Œuvres, Paris, Gallimard, coll. « Quarto », 1995, p. 1400. Toutes les références aux œuvres de Cioran sont extraites de cette édition, alors que les œuvres d’autres auteurs sont tirées d’éditions italiennes, sauf exception notifiée le cas échéant. Les traductions sont de l’Auteur (T.d.A.).

[2] D.T. Suzuki avait déjà tenté un premier parallèle entre la Genèse et le bouddhisme : « L’idée judéo-chrétienne de l’Innocence est l’interprétation morale de la doctrine bouddhiste de la Vacuité, qui est métaphysique ; alors que l’idée judéo-chrétienne de la Connaissance correspond, du point de vue épistémologique, à la notion bouddhique de l’Ignorance, encore que l’Ignorance soit superficiellement le contraire de la Connaissance », in D.T. Suzuki, « Sagesse et vacuité », Hermès, n° 2 « Le vide. Expérience spirituelle en Occident et en Orient », Paris, 1981, p. 172.

[3] De l’inconvénient d’être né, p. 1372.

[4] Ibid., p. 1399.

[5] Ibid, p. 1346.

[6] La Chute dans le temps, p. 1076.

[7] Ibid, p. 1073.

[8] Histoire et utopie, p. 128.

[9] De l’inconvénient d’être né, p. 1283.

[10] Cahiers. 1957-1972, Paris, Gallimard, coll. « Blanche », 1997, p. 139.

[11] Ibid., p. 156.

[12] Houeï-nêng (638-713), le sixième patriarche fondateur de l’école Ch’an du sud, se demande : « Qu’est-ce qu’est le wu-nien, l’absence de pensée ? Voir toutes les choses, pourtant maintenir notre esprit pur de chaque tache et de chaque attachement – celle-ci est l’absence de pensée » cit. in D.T. Suzuki, La dottrina Zen del vuoto mentale, Astrolabio-Ubaldini, Roma, p. 105. (T.d.A.). Takuan Sōhō (1573-1645), maître japonais de l’école Rinzai-shu, écrit : « En réalité, le vrai Soi est le soi qui existait avant la division entre ciel et terre, et avant encore la naissance du père et de la mère. Ce soi est mon soi intérieur, les oiseaux et les animaux, les plantes et les arbres et tous les phénomènes. C’est exactement ce que nous appelons la nature du Bouddha », cit. in Takuan Sōhō, La mente senza catene, Rome, Edizioni Mediterranee, 2010, p. 109 (T.d.A.). Le non-né ou non-produit est un terme forgé par le maître japonais Bankei (1622-1693) pour indiquer l’esprit bouddhique, antérieur à la scission opérée par la conscience.

[13] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 728.

[14] « J’ai l’intention d’écrire un essai sur cet état que j’aime entre tous, et qui est celui de savoir qu’on ne pense pas. La pure contemplation du vide. » Ibid., p. 300.

[15]Ibid., p. 298. À cette occasion, Cioran décrit ainsi son interlocuteur : « Extrêmement intelligent et insaisissable. Son mépris total pour les Occidentaux. J’ai eu nettement l’impression qu’il m’était supérieur, sentiment que je n’ai pas souvent avec les gens d’ici. »

[16] Ibid., p. 364.

[17] Ibid., p. 366.

[18] Ibid., p. 457.

[19] De l’inconvénient d’être né, p. 1281.

[20] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 94.

[21] Ibid., p. 119.

[22] Littéralement « ce qui est ainsi », ou bien, voir les choses telles qu’elles sont. Dans l’interview avec Christian Bussy, réalisée à Paris le 19 février 1973 pour la télévision belge, Cioran argumente : « Je crois effectivement que voir les choses telles qu’elles sont rend la vie presque intolérable. En ce sens que j’ai remarqué que tous les gens qui agissent ne peuvent agir que parce qu’ils ne voient pas les choses telles qu’elles sont. Et moi, parce que je crois avoir vu, disons, en partie les choses comme elles sont, je n’ai pas pu agir. Je suis toujours resté en marge des actes. Alors, est-ce qu’il souhaitable pour les hommes de voir les choses telles qu’elles sont, je ne sais pas. Je crois que les gens en sont généralement incapables. Alors, il est vrai que seul un monstre peut voir les choses telles qu’elles sont. Puisque le monstre, il est sorti de l’humanité ». Le texte nous a été fourni par Christian Bussy, que nous remercions.

[23] Cf. Takuan Sōhō, Op. cit., p. 31.

[24] D.T. Suzuki, Saggi sul buddismo Zen, Rome, Edizioni Mediterranee, 1992, vol. I, p. 282. La peinture à l’encre noire (sumi-e) se produit sur du papier de riz, rêche, mince et assez absorbant, cela ne permet pas d’avoir des mouvements de pinceau hésitants, car il en résulterait des taches: il faut que le peintre agisse soudainement et avec netteté, sans revirements, comme s’il maniait une épée.

[25] Takuan Sōhō, Op. cit., p. 31.

[26] De l’inconvénient d’être né, p. 1289.

[27] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 437.

[28] Ibid., p. 295.

[29] Ibid., pp. 437 et 674.

[30] Izutsu, La filosofia del buddismo zen, Rome, Astrolabio-Ubaldini, 1984, p. 40 (T.d.A.). Le kōan, (en chinois : kung-an), est un terme Zen qui désigne une sorte de problème ou casse-tête, intentionnellement illogique, donné par le maître comme sujet de méditation pour l’élève. Celui-ci, en se tourmentant à cause de cette énigme insoluble, se trouvera bientôt face à une barrière insurmontable, sans issue, jusqu’ il se mette à désespérer de chaque solution logique et discursive possible. Devant l’évidence du vide, la conscience abdique, et se met au niveau de compréhension qu’implique tout être concret, en tant que corps et en tant qu’esprit. Il en résulte la production de la seule réponse possible, qui coïncide avec le retour à la réalité, au flux inconscient de la vie qui depuis toujours nous soutient.

[31] Suivant un célèbre kōan : « Avant qu’une personne n’étudie le Zen, les montagnes sont les montagnes, les eaux sont les eaux. Après un premier aperçu de la vérité du Zen, les montagnes ne sont plus les montagnes, les eaux ne sont plus les eaux. Après l’éveil, les montagnes sont de nouveau des montagnes, les eaux de nouveau des eaux »

[32] Suzuki, La dottrina zen del vuoto mentale, op. cit., p. 91. « La phrase la plus célèbre de Tu-shan était ‘‘Trente coups quand tu peux dire un mot, trente coups quand tu ne peux pas dire un mot !’’ ‘‘Dire un mot’’ c’est une expression presque technique du Zen et signifie n’importe quelle chose démontrée soit par les mots, soit par les gestes, au sujet du fait central du Zen. Dans ce cas ‘‘donner un coup’’ signifie que toutes ces démonstrations ne sont d’aucune utilité. » Ibid.

[33] Interview de Christian Bussy à Cioran, réalisée à Paris le 19 février 1973.

[34] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 642.

[35] D. T. Suzuki, Saggi sul buddismo Zen, Rome, Edizioni Mediterranee, 1992, vol. I, p. 216.

[36] Cf. Leonardo Vittorio Arena, Storia del buddismo Ch’an, Milan, Mondatori, 1998, pp. 190-191.

[37] E.M. Cioran, « Hantise de la naissance », La Nouvelle Revue Française, n° 217, Paris, janvier 1971, p. 15. Il est caractéristique que dans la première version de cet aphorisme, Cioran utilise justement le mot Zen satori, tandis que dans la version suivante publiée dans De l’inconvénient d’être né, il la remplace par le terme de dérivation mystique « suprême ».

[38] L’amour traditionnel pour les fleurs de cerisier est un exemple typique de mono no aware dans le Japon contemporain. Esthétiquement, ces fleurs ne sont pas plus belles que celles du poirier ou du pommier, cependant ils sont les plus appréciés par les japonais pour leur caractère transitoire. En effet, ces fleurs commencent à tomber habituellement une semaine après leur épanouissement. Les fleurs de cerisier font objet d’un véritable culte au Japon, rituellement, toutes les années une foule énorme envahit les champs pour en admirer la floraison.

[39] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 748.

[40] Cioran, Écartèlement, p. 103 : « On ne peut être content de soi que lorsqu’on se rappelle ces instants où, selon un mot japonais, on a perçu le ah ! des choses. » Cette exclamation reprend l’Entretien avec Léo Gillet : « Ça, on peut le sentir, mais on ne peut pas l’exprimer en paroles, sauf dire : ‘‘Ah ! indéfiniment […] on ne peut pas formuler abstraitement une chose qui doit être vraiment sentie’’ », in Cioran, Entretiens, Paris, Gallimard coll. « Arcades », 1995, p. 94.

[41] Cf. Leonardo Vittorio Arena, Lo spirito del Giappone, Milan, BUR, 2008, pp. 376-377.

[42] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 996.

[43] Ibid., p. 170.

[44] Ibid., p. 568.

[45] De l’inconvénient d’être né, p. 1288.

[46] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 674.

[47] Ibid., p. 323. À ce propos, selon Izutsu : « Le Zen demande vigoureusement que même une telle quantité de conscience du moi soit effacée de l’esprit, de même que finalement tout soit réduit au seul acte de VOIR pur et simple. Le mot ‘‘non-esprit’’, déjà mentionné, se réfère précisément à l’acte pur du VOIR, dans l’état d’une réalisation immédiate et directe », La filosofia del buddismo zen, p. 30.

[48] C’est-à-dire : « quelle est la vérité fondamentale du Zen ? ».

[49] Cfr. Izutsu, La filosofia del buddismo zen, op. cit., p. 160.

[50] De l’inconvénient d’être né, p. 1383.

[51] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 298.

[52] Cioran, Cahier de Talamanca – Ibiza (31 juillet-25 août 1966), Paris, Mercure de France, 2000, p. 30.

[53] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 298.

[54] Cahier de Talamanca, op. cit., p. 13.

[55] Cioban : berger en roumain. Dans la lettre à Arşavir Acterian du 11 juillet 1972, il avoue : « … je serais plus dans le vrai aujourd’hui si j’avais fait une carrière de cioban dans mon village natal plutôt que de me trémousser dans cette métropole de saltimbanques », in Emil Cioran, Scrisori cãtre cei de-acasă, Bucarest, Humanitas, 1995, p. 215 (T.d.A.).

[56] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 101.

[57] Ibid., p. 137.

[58] Ibid., p. 298.

[59] Ibid., p. 101.

[60] Ibid., p. 851.

[61] La Raccolta di Lin-chi (Rinzai Roku), trad. par Ruth Fuller Sasaki, Rome, Astrolabio-Ubaldini, 1985, p. 30.

[62] Verset du poète zen P’ang-yun, cité in Alan W. Watts, The Way of Zen, trad. it, La via dello Zen, Feltrinelli, Milano, 2000, p. 145 (T.d.A.).

[63] Cioran, Aveux et anathèmes, p. 1724.

[64] La Raccolta di Lin-chi, op. cit., p. 46.

[65] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 994.

[66] Cioran cite l’anecdote dans ses Cahiers, op. cit., p. 869.

[67] De l’inconvénient d’être né, p. 1396.

[68] Cahiers, op. cit., p. 306.

[69].Lettre à Arşavir Acterian du 13 juillet 1986, Cioran, Scrisori cãtre cei de-acasă, op. cit., p. 241(T.d.A.).

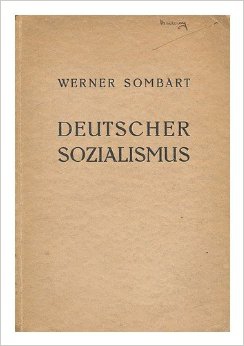

Wiewohl Sombart überhaupt den Einfluss eines säkularisierten Judentums für das Aufkommen von Kapitalismus und Sozialismus hoch anschlägt, so führt er doch nie beide kausal, d.h. schlechthin auf das Judentum zurück. Nur sei das spezifische Gepräge des modernen Kapitalismus wie des modernen Sozialismus „den Juden“ bzw. dem „jüdischen Geist“ zu verdanken, wobei Sombart übrigens letzteren – wie überhaupt alle „Volksgeister“ – von seiner leibseelischen Grundlage für ablösbar und sogar für übertragbar hält.

Wiewohl Sombart überhaupt den Einfluss eines säkularisierten Judentums für das Aufkommen von Kapitalismus und Sozialismus hoch anschlägt, so führt er doch nie beide kausal, d.h. schlechthin auf das Judentum zurück. Nur sei das spezifische Gepräge des modernen Kapitalismus wie des modernen Sozialismus „den Juden“ bzw. dem „jüdischen Geist“ zu verdanken, wobei Sombart übrigens letzteren – wie überhaupt alle „Volksgeister“ – von seiner leibseelischen Grundlage für ablösbar und sogar für übertragbar hält.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Le témoin oculaire d’une époque de transition

Le témoin oculaire d’une époque de transition Un humaniste dégouté par la violence ordinaire

Un humaniste dégouté par la violence ordinaire

On pourrait, facilement, opposer l’idéal de la cité (le rayonnement des familles patriciennes) à celui de l’imperium (le nivellement des citoyens afin qu’ils deviennent des sujets consentants). Que s’est-il passé, en Occident, pour que l’idéal de la cité finisse par imploser sous la pression d’un imperium protéiforme et « multicartes »?

On pourrait, facilement, opposer l’idéal de la cité (le rayonnement des familles patriciennes) à celui de l’imperium (le nivellement des citoyens afin qu’ils deviennent des sujets consentants). Que s’est-il passé, en Occident, pour que l’idéal de la cité finisse par imploser sous la pression d’un imperium protéiforme et « multicartes »?

È in Agostino e nei suoi dialoghi interiori con il suo Dio che nasce l’Io moderno come soggetto-singolo; Agostino dice per la prima volta: “Ego”, anticipando Cartesio e tutto il soggettivismo moderno. Pertanto effettuale all’assenza di qualsiasi personalismo o soggettivismo, in quanto non vi è, nel mondo indoeuropeo, alcuna presenza dell’Io, come si è accennato sopra, è l’inesistenza culturale della tematica “teismo-ateismo” che è processo dialettico paralizzante interno alla cultura astratta del monoteismo creazionistico e potenzialmente ateo, in quanto concepisce Dio come persona (personalizzazione del Divino) dotata di volontà e “progetto” creativo, d’ “amore” e di “compassione”, il tutto in una “umanizzazione” del Divino a cui, giustamente, W.F.Otto contrapponeva la elevazione greca ed indoeuropea dell’uomo verso il Divino e cioè la “divinizzazione” dell’umano (omòiosis theò). Nel mondo spirituale indoeuropeo in tanto non vi è dualismo religioso, in tanto il Divino è nel Mondo, in quanto esso (il Divino) non è nulla di personale, di “umano”, e quindi di “staccato” dal mondo; esso è, invece, il Principio del Mondo, il suo Arché ed è presente “in esso” impersonalmente poiché Potenza Divina nel Mondo medesimo; essendo (il Divino) il Mondo stesso però nella sua essenza: come Idea dell’Unità; in caso contrario non avrebbe avuto senso la sapienza ellenica che insegna (da Talete a Proclo…) che il mondo è ricolmo di Dei! L’assenza del concetto teistico di persona fa cadere nel nulla dell’inesistenza l’altro polo ad esso connesso: l’ateismo, il quale sorge inesorabilmente quando quella “persona” viene meno perché scompare la fede (secolarizzazione… modernità).

È in Agostino e nei suoi dialoghi interiori con il suo Dio che nasce l’Io moderno come soggetto-singolo; Agostino dice per la prima volta: “Ego”, anticipando Cartesio e tutto il soggettivismo moderno. Pertanto effettuale all’assenza di qualsiasi personalismo o soggettivismo, in quanto non vi è, nel mondo indoeuropeo, alcuna presenza dell’Io, come si è accennato sopra, è l’inesistenza culturale della tematica “teismo-ateismo” che è processo dialettico paralizzante interno alla cultura astratta del monoteismo creazionistico e potenzialmente ateo, in quanto concepisce Dio come persona (personalizzazione del Divino) dotata di volontà e “progetto” creativo, d’ “amore” e di “compassione”, il tutto in una “umanizzazione” del Divino a cui, giustamente, W.F.Otto contrapponeva la elevazione greca ed indoeuropea dell’uomo verso il Divino e cioè la “divinizzazione” dell’umano (omòiosis theò). Nel mondo spirituale indoeuropeo in tanto non vi è dualismo religioso, in tanto il Divino è nel Mondo, in quanto esso (il Divino) non è nulla di personale, di “umano”, e quindi di “staccato” dal mondo; esso è, invece, il Principio del Mondo, il suo Arché ed è presente “in esso” impersonalmente poiché Potenza Divina nel Mondo medesimo; essendo (il Divino) il Mondo stesso però nella sua essenza: come Idea dell’Unità; in caso contrario non avrebbe avuto senso la sapienza ellenica che insegna (da Talete a Proclo…) che il mondo è ricolmo di Dei! L’assenza del concetto teistico di persona fa cadere nel nulla dell’inesistenza l’altro polo ad esso connesso: l’ateismo, il quale sorge inesorabilmente quando quella “persona” viene meno perché scompare la fede (secolarizzazione… modernità).

Alors Eric Werner (re)découvre, exhume cette oeuvre mythique. Et il faut reconnaître que sa (re)découverte, son exhumation, la fait apparaître sous un jour on ne peut plus moderne. Quoi de neuf? Sophocle, vingt-cinq siècles plus tard...

Alors Eric Werner (re)découvre, exhume cette oeuvre mythique. Et il faut reconnaître que sa (re)découverte, son exhumation, la fait apparaître sous un jour on ne peut plus moderne. Quoi de neuf? Sophocle, vingt-cinq siècles plus tard...

Keyserling was very pessimistic about America’s influence abroad. He believed President Wilson’s Fourteen Points “have really wrecked Europe and imperilled the position of the whole white race. They are the spiritual parents of Bolshevism because, but for the idea of the self-determination of nations and Wilson’s utter disregard of historical connexions, the Bolsheviks would never have succeeded in revolutionizing the whole East and never even dreamt of attempting the same in Europe” (p. 84).

Keyserling was very pessimistic about America’s influence abroad. He believed President Wilson’s Fourteen Points “have really wrecked Europe and imperilled the position of the whole white race. They are the spiritual parents of Bolshevism because, but for the idea of the self-determination of nations and Wilson’s utter disregard of historical connexions, the Bolsheviks would never have succeeded in revolutionizing the whole East and never even dreamt of attempting the same in Europe” (p. 84).

Orwell opened a door for all to see a “nightmarish future” in which everyday life becomes harsh, an object of state surveillance, and control—a society in which the slogan “ignorance becomes strength” morphs into a guiding principle of mainstream media, education, and the culture of politics. Huxley shared Orwell’s concern about ignorance as a political tool of the elite, enforced through surveillance and the banning of books, dissent, and critical thought itself. But Huxley, believed that social control and the propagation of ignorance would be introduced by those in power through the political tools of pleasure and distraction. Huxley thought this might take place through drugs and genetic engineering, but the real drugs and social planning of late modernity lies in the presence of an entertainment and public pedagogy industry that trades in pleasure and idiocy, most evident in the merging of neoliberalism, celebrity culture, and the control of commanding cultural apparatuses extending from Hollywood movies and video games to mainstream television, news, and the social media.

Orwell opened a door for all to see a “nightmarish future” in which everyday life becomes harsh, an object of state surveillance, and control—a society in which the slogan “ignorance becomes strength” morphs into a guiding principle of mainstream media, education, and the culture of politics. Huxley shared Orwell’s concern about ignorance as a political tool of the elite, enforced through surveillance and the banning of books, dissent, and critical thought itself. But Huxley, believed that social control and the propagation of ignorance would be introduced by those in power through the political tools of pleasure and distraction. Huxley thought this might take place through drugs and genetic engineering, but the real drugs and social planning of late modernity lies in the presence of an entertainment and public pedagogy industry that trades in pleasure and idiocy, most evident in the merging of neoliberalism, celebrity culture, and the control of commanding cultural apparatuses extending from Hollywood movies and video games to mainstream television, news, and the social media. At the same time, Orwell’s warning about “Big Brother” applies not simply to an authoritarian-surveillance state but also to commanding financial institutions and corporations who have made diverse modes of surveillance a ubiquitous feature of daily life. Corporations use the new technologies to track spending habits and collect data points from social media so as to provide us with consumer goods that match our desires, employ face recognition technologies to alert store salesperson to our credit ratings, and so it goes. Heidi Boghosian points out that if omniscient state control in Orwell’s 1984 is embodied by the two-way television sets present in each home, then in “our own modern adaptation, it is symbolized by the location-tracking cell phones we willingly carry in our pockets and the microchip-embedded clothes we wear on our bodies.”

At the same time, Orwell’s warning about “Big Brother” applies not simply to an authoritarian-surveillance state but also to commanding financial institutions and corporations who have made diverse modes of surveillance a ubiquitous feature of daily life. Corporations use the new technologies to track spending habits and collect data points from social media so as to provide us with consumer goods that match our desires, employ face recognition technologies to alert store salesperson to our credit ratings, and so it goes. Heidi Boghosian points out that if omniscient state control in Orwell’s 1984 is embodied by the two-way television sets present in each home, then in “our own modern adaptation, it is symbolized by the location-tracking cell phones we willingly carry in our pockets and the microchip-embedded clothes we wear on our bodies.” Relentlessly entertained by spectacles, people become not only numb to violence and cruelty but begin to identify with an authoritarian worldview. As David Graeber suggests, the police “become the almost obsessive objects of imaginative identification in popular culture… watching movies, or viewing TV shows that invite them to look at the world from a police point of view.”

Relentlessly entertained by spectacles, people become not only numb to violence and cruelty but begin to identify with an authoritarian worldview. As David Graeber suggests, the police “become the almost obsessive objects of imaginative identification in popular culture… watching movies, or viewing TV shows that invite them to look at the world from a police point of view.” Another egregious example of neoliberalism’s Orwellian assault on higher education can be found in the policies promoted by the Republican Party members who control the North Carolina Board of Governors. Just recently it has decimated higher education in that state by voting to cut 46 degree programs. One member defended such cuts with the comment: “We’re capitalists, and we have to look at what the demand is, and we have to respond to the demand.”

Another egregious example of neoliberalism’s Orwellian assault on higher education can be found in the policies promoted by the Republican Party members who control the North Carolina Board of Governors. Just recently it has decimated higher education in that state by voting to cut 46 degree programs. One member defended such cuts with the comment: “We’re capitalists, and we have to look at what the demand is, and we have to respond to the demand.” Hay un reclamo persistente en Drieu: “Voces falsarias y hueras me han acusado de que mi posición surge de un adaptarme a las formas políticas que se proyectan como victoriosas, en este momento de la guerra y que serían las dominantes en el futuro, todo ello es falso”

Hay un reclamo persistente en Drieu: “Voces falsarias y hueras me han acusado de que mi posición surge de un adaptarme a las formas políticas que se proyectan como victoriosas, en este momento de la guerra y que serían las dominantes en el futuro, todo ello es falso” Sobre el particular apunta Drieu: “Me he convencido de que Guénon anuncia, con el lenguaje cifrado propio de la Tradición sagrada de los pueblos, que se aproxima un cambio drástico en la valoración de los hombres y en el sentido de la vida; en ello he visto a las nuevas fuerzas que se alzan contra los dogmas, al parecer inamovibles, de una civilización basada en el dinero, el materialismo y en formas políticas caducas”.

Sobre el particular apunta Drieu: “Me he convencido de que Guénon anuncia, con el lenguaje cifrado propio de la Tradición sagrada de los pueblos, que se aproxima un cambio drástico en la valoración de los hombres y en el sentido de la vida; en ello he visto a las nuevas fuerzas que se alzan contra los dogmas, al parecer inamovibles, de una civilización basada en el dinero, el materialismo y en formas políticas caducas”.

Ortega clearly appreciates the value of modern technology and admires the skills of those who develop and apply it. But he does not think that technocrats constitute a true elite. In fact, he tends to regard them merely as mass men with high IQs—clever barbarians, indispensable barbarians, but barbarians nonetheless. Ortega also thought that the progress of industrialism and technology would bring about the worst form of mass society: a global and homogeneous mass society.

Ortega clearly appreciates the value of modern technology and admires the skills of those who develop and apply it. But he does not think that technocrats constitute a true elite. In fact, he tends to regard them merely as mass men with high IQs—clever barbarians, indispensable barbarians, but barbarians nonetheless. Ortega also thought that the progress of industrialism and technology would bring about the worst form of mass society: a global and homogeneous mass society. Ayn Rand’s philosophical journal for May 16, 1934, begins with a passage by the American journalist Alexander Wolcott contrasting the cultural atmosphere of the Soviet Union with the West. It closes with a passage copied out from the last chapter of The Revolt of the Masses. Between them, Rand wrote two remarkable paragraphs:

Ayn Rand’s philosophical journal for May 16, 1934, begins with a passage by the American journalist Alexander Wolcott contrasting the cultural atmosphere of the Soviet Union with the West. It closes with a passage copied out from the last chapter of The Revolt of the Masses. Between them, Rand wrote two remarkable paragraphs:

Thomas Edward Lawrence était farouchement hostile à la parution de son vivant des mémoires et comptes-rendus de ses aventures et opérations militaires conduites en Arabie entre 1916 et 1918. Il fit imprimer, en 1922, une édition privée qui circula dans un cercle très restreint. Lawrence estimait que certains passages des Sept Piliers étaient trop personnels, voire compromettants. Il ne souhaitait pas non plus embarrasser ses supérieurs hiérarchiques de la Royal Air Force : l’ancien colonel, héros de guerre de notoriété internationale, était alors devenu à sa demande un simple subalterne engagé sous un pseudonyme.

Thomas Edward Lawrence était farouchement hostile à la parution de son vivant des mémoires et comptes-rendus de ses aventures et opérations militaires conduites en Arabie entre 1916 et 1918. Il fit imprimer, en 1922, une édition privée qui circula dans un cercle très restreint. Lawrence estimait que certains passages des Sept Piliers étaient trop personnels, voire compromettants. Il ne souhaitait pas non plus embarrasser ses supérieurs hiérarchiques de la Royal Air Force : l’ancien colonel, héros de guerre de notoriété internationale, était alors devenu à sa demande un simple subalterne engagé sous un pseudonyme.

R.R.: Cioran’s first book to be published in Italy was Squartamento (Drawn and quartered) launched by Adelphi in 1981, even though some other titles had already been published in the previous decade by right-wing publishing houses, even if they had not had much repercussion. It was precisely thanks to Adelphi, and to Ceronetti’s wonderful introduction, that the name of Cioran became well-known to the Italian readers. Roberto Calasso is a great cultural player, but he is a rather arrogant person and, I must say, ungallant as well. My encounters with Cioran and Severino, two giants of thought, allowed me to understand how the true greatness is always accompanied by genuine humbleness a gentleness. Virtues which Calasso, in my opinion, lacks – and I say so based on the personal experience I have had with him in more than one occasion. Unfortunately, Volpi left us too early due to a banal accident while riding his bicycle on the Venetian hills (northeast of Italy), not far away from where I live. His intelligence illuminated us for a long a time. In 2002, he wrote a piece on Friedgard Thoma‘s book, Per nulla al mondo, releasing himself once and for all from the choir of censors, who had soon made their apparition. I enjoy recalling this marvellous passage: “Under the influence of passion, Cioran reveals himself. He jeopardizes everything in order to win the game, reveals innermost dimensions of his psyche, surprising features of his character… Attracted by the challenge of the eternal feminine, he allows secret depths of his thought to come to surface: a denuded thought before the feminine look which penetrates him…”

R.R.: Cioran’s first book to be published in Italy was Squartamento (Drawn and quartered) launched by Adelphi in 1981, even though some other titles had already been published in the previous decade by right-wing publishing houses, even if they had not had much repercussion. It was precisely thanks to Adelphi, and to Ceronetti’s wonderful introduction, that the name of Cioran became well-known to the Italian readers. Roberto Calasso is a great cultural player, but he is a rather arrogant person and, I must say, ungallant as well. My encounters with Cioran and Severino, two giants of thought, allowed me to understand how the true greatness is always accompanied by genuine humbleness a gentleness. Virtues which Calasso, in my opinion, lacks – and I say so based on the personal experience I have had with him in more than one occasion. Unfortunately, Volpi left us too early due to a banal accident while riding his bicycle on the Venetian hills (northeast of Italy), not far away from where I live. His intelligence illuminated us for a long a time. In 2002, he wrote a piece on Friedgard Thoma‘s book, Per nulla al mondo, releasing himself once and for all from the choir of censors, who had soon made their apparition. I enjoy recalling this marvellous passage: “Under the influence of passion, Cioran reveals himself. He jeopardizes everything in order to win the game, reveals innermost dimensions of his psyche, surprising features of his character… Attracted by the challenge of the eternal feminine, he allows secret depths of his thought to come to surface: a denuded thought before the feminine look which penetrates him…” R.R.: My book undertakes a theoretical exegesis of Cioran’s thought so as to evince how the problem of Time is the basis for all his meditation. The connective “and” of the title becomes the supporting verb for the thesis I intend to sustain: Time is Destiny. The curse of existence is that of being “incarcerated” in the linearity of time, which stems from a paradisiacal, pre-temporal past, toward a destiny of death and decay. It is, to sum up, a tragic worldview of Greek origin embedded in a Judeo-Christian conception, though deprived of all éscathon. But can we be sure that Cioran dismisses each and every form of salvation? There are two polarities which communicate in my book: Severino’s absolute eternity and Cioran’s explicit nihilism. From Severino’s point of view, one might as well define Cioran’s thought as the becoming aware of nihilism inherent to the Western conception of Time. And in Cioran’s mystical temptation, on the other hand, one may find a sentimental perception of Being which seems to point to the need, the urge, the hope, so to speak, for an overcoming of Western hermeneutics of Becoming and for an ulterior word that is not Negation. The book starts with an account of my three encounters with Aurel, Cioran’s brother, in the years of 1987, 1991 and 1995, and of my two encounters with Emil, in 1988 and 1989. The book also includes all the letters which Cioran wrote to me, plus countless photographs. After the first part, there comes a bio-bibliographical inquiry on his Romanian years, a pioneer work of exhumation at a time when there were no reliable sources on the matter.

R.R.: My book undertakes a theoretical exegesis of Cioran’s thought so as to evince how the problem of Time is the basis for all his meditation. The connective “and” of the title becomes the supporting verb for the thesis I intend to sustain: Time is Destiny. The curse of existence is that of being “incarcerated” in the linearity of time, which stems from a paradisiacal, pre-temporal past, toward a destiny of death and decay. It is, to sum up, a tragic worldview of Greek origin embedded in a Judeo-Christian conception, though deprived of all éscathon. But can we be sure that Cioran dismisses each and every form of salvation? There are two polarities which communicate in my book: Severino’s absolute eternity and Cioran’s explicit nihilism. From Severino’s point of view, one might as well define Cioran’s thought as the becoming aware of nihilism inherent to the Western conception of Time. And in Cioran’s mystical temptation, on the other hand, one may find a sentimental perception of Being which seems to point to the need, the urge, the hope, so to speak, for an overcoming of Western hermeneutics of Becoming and for an ulterior word that is not Negation. The book starts with an account of my three encounters with Aurel, Cioran’s brother, in the years of 1987, 1991 and 1995, and of my two encounters with Emil, in 1988 and 1989. The book also includes all the letters which Cioran wrote to me, plus countless photographs. After the first part, there comes a bio-bibliographical inquiry on his Romanian years, a pioneer work of exhumation at a time when there were no reliable sources on the matter.

À partir du vers du poète grec Cavafy « En attendant les barbares », Jure Vujic file l’image d’une attente rendue vaine par la présence des barbares à l’intérieur même de l’espace européen, les élites s’étant depuis bien longtemps barbarisées. C’est à un véritable examen de conscience que nous appelle Vujic en nous proposant de traquer en nous cette part de barbarie, cet assentiment coupable, qui s’est imposé et s’étend. L’origine de l’apathie des peuples européens est bien là. La colonisation du « mental, de l’imaginaire individuel et collectif européen ». Les peuples de la Vieille Europe sont devenus incapables de réagir à la gravité du réel car leur esprit demeure anesthésié par plusieurs décennies de propagande. Désarmés spirituellement et philosophiquement, privés de leurs ressorts intérieurs, les Européens n’ont plus les ressources nécessaires pour s’opposer aux nombreux assauts venus de l’extérieur.

À partir du vers du poète grec Cavafy « En attendant les barbares », Jure Vujic file l’image d’une attente rendue vaine par la présence des barbares à l’intérieur même de l’espace européen, les élites s’étant depuis bien longtemps barbarisées. C’est à un véritable examen de conscience que nous appelle Vujic en nous proposant de traquer en nous cette part de barbarie, cet assentiment coupable, qui s’est imposé et s’étend. L’origine de l’apathie des peuples européens est bien là. La colonisation du « mental, de l’imaginaire individuel et collectif européen ». Les peuples de la Vieille Europe sont devenus incapables de réagir à la gravité du réel car leur esprit demeure anesthésié par plusieurs décennies de propagande. Désarmés spirituellement et philosophiquement, privés de leurs ressorts intérieurs, les Européens n’ont plus les ressources nécessaires pour s’opposer aux nombreux assauts venus de l’extérieur.