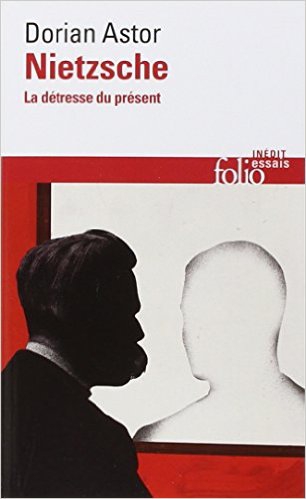

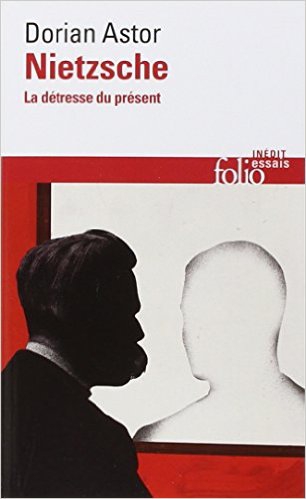

Dorian Astor est philosophe, ancien élève de l’École normale supérieure et agrégé d’allemand, il a publié chez Gallimard une biographie sur Nietzsche (2011). Dans Nietzsche, la détresse du présent (2014), il interroge le rapport qu’entretient l’auteur de Par-delà bien et mal avec la modernité politique et philosophique.

PHILITT : Vous considérez que la philosophie naît en temps de détresse. Quelle est cette détresse qui a fait naître la philosophie (si l’on date son apparition au Ve av. J.-C. avec Socrate) ?

Dorian Astor : Je ne dis pas exactement que la philosophie naît en temps de détresse, dans le sens où une époque historique particulièrement dramatique expliquerait son apparition. Je dis qu’il y a toujours, à l’origine d’une philosophie ou d’un problème philosophique, un motif qui peut être reconnu comme un motif de détresse. Deleuze disait qu’un concept est de l’ordre du cri, qu’il y a toujours un cri fondamental au fond d’un concept (Aristote : « Il faut bien s’arrêter ! » ; Leibniz : « Il faut bien que tout ait une raison ! », etc.). Dans le cas de Socrate, on sent bien que son motif de détresse, c’est une sorte de propension de ses concitoyens à dire tout et son contraire et à vouloir toujours avoir raison. Son cri serait quelque chose comme : « On ne peut pas dire n’importe quoi ! » C’est alors le règne des sophistes, mais aussi du caractère procédurier des Athéniens. C’est ce qui explique que Platon articule si fondamentalement la justice à la vérité. Or l’absence de justice et la toute-puissance de la seule persuasion ou de la simple image dans l’établissement de la vérité, voilà un vrai motif de détresse, que l’on retrouvera par exemple dans le jugement sévère que porte Platon sur la démocratie.

Je crois que chaque philosophe est mû par une détresse propre, qu’il s’agit de déceler pour comprendre le problème qu’il pose. Il est vrai que dans de nombreux cas, en effet, la détresse d’un philosophe rejoint celle d’une époque, c’est souvent une détresse de nature politique : Leibniz, par exemple, est obsédé par l’ordre : les luttes confessionnelles et le manque d’unité politique le rendent fou, c’est pourquoi il passe son temps à chercher des solutions à tout ce désordre, à réintroduire de l’harmonie. Pour Sartre, ce sera la question, à cause de la guerre et de la collaboration, de l’engagement et de la trahison. Il y aurait mille autres exemples.

Dans mon livre sur Nietzsche, j’essaie de montrer que l’un de ses motifs fondamentaux de détresse est le présent (un autre motif serait le non-sens de la souffrance, cri par excellence, mais c’est une autre affaire). Le présent, non seulement au sens de l’époque qui lui est contemporaine, mais en un sens absolu : le pur présent, coincé entre le poids du passé et l’incertitude de l’avenir, jusqu’à l’asphyxie. Des notions comme celles d’ « inactualité », de « philosophie de l’avenir » ou même d’« éternel retour » et de « grande politique », etc., sont autant de tentatives pour répondre à et de cette détresse du présent. L’un des grands cris de Nietzsche sera héraclitéen : « Il n’y a que du devenir ! » Heidegger a parfaitement senti cette dimension du cri dans la philosophie de Nietzsche. Or, c’est un cri parce que cette « vérité » est mortelle, on peut périr de cette « vérité ». Nietzsche s’efforce d’inventer des conditions nouvelles de pensée qui permettraient au contraire de vivre de cette « vérité » : ce sont les figures de l’« esprit libre », du « philosophe-médecin » et même du « surhumain ». Tous ces guillemets appartiennent de plein droit aux concepts de Nietzsche : c’est le moyen le plus simple qu’il ait trouvé pour continuer à écrire alors qu’il se méfiait radicalement du langage, de son irréductible tendance à l’hypostase, c’est-à-dire de son incapacité à saisir le devenir.

Selon vous, Nietzsche a quelque chose à nous dire aujourd’hui. Est-ce parce que nous traversons une crise généralisée ou bien parce que nous sommes les lecteurs de l’an 2000 qu’il espérait tant ?

Il y a eu un léger malentendu sur la démarche que j’adopte dans mon livre — et que l’on retrouve jusque sur sa quatrième de couverture, dans une petite phrase que je n’ai pu faire supprimer : « ses vrais lecteurs, c’est nous désormais ». Non, nous ne sommes pas aujourd’hui les lecteurs privilégiés de Nietzsche. Si c’était le cas, il n’y aurait d’ailleurs pas besoin de continuer à publier des livres sur lui pour essayer d’« encaisser » ce qu’il nous lance à la face. Lorsqu’on voit le portrait que dresse Nietzsche de son lecteur parfait, par exemple dans Ecce Homo[1], on se dit qu’on est vraiment loin du compte… Je fais simplement l’hypothèse que, sous certaines conditions, le diagnostic qu’établit Nietzsche à propos de la modernité, de l’homme moderne et des « idées modernes », comme il dit, nous concerne encore directement : je crois, pour paraphraser Habermas dans un autre contexte, que la modernité est un projet inachevé[2]. Nous sommes très loin d’en avoir fini avec les sollicitations de Nietzsche à exercer une critique profonde de nos manières de vivre et de penser. En ce sens, nous sommes toujours des « modernes » et la notion fourre-tout de « postmodernité » ne règle pas le problème. Sans doute est-on d’ailleurs autorisé à formuler cette hypothèse par la temporalité propre à la critique généalogique nietzschéenne, qui est celle du temps long. « Que sont donc quelques milliers d’années[3] ! » s’exclamait-il. Que sont 150 ans, après tout ? Bien évidemment, il ne s’agit pas de dire que rien n’a changé depuis l’époque de Nietzsche, ou même que rien ne change jamais, ce qui serait parfaitement ridicule ; mais de sentir que, du point de vue de Nietzsche, nous n’en avons pas fini d’être modernes : dans notre rapport à la science, à la morale, à la politique, etc. De toute façon, Nietzsche a un usage très extensif de la notion de moderne : on le voit, dans sa critique, remonter l’air de rien de siècles en siècles jusqu’à Socrate, voire jusqu’à l’apparition du langage ! — comme si le problème était en fait l’« homme » en tant que tel, ce qu’il répète d’ailleurs souvent.

Mais revenons à cette notion de « crise généralisée » de l’époque actuelle. Que la situation ne soit pas bonne, c’est évident. Mais je crois avec Nietzsche que nous n’avons pas non plus le privilège de la détresse. Permettez-moi de citer un peu longuement un fragment de 1880 : « Une époque de transition c’est ainsi que tout le monde appelle notre époque, et tout le monde a raison. Mais non dans le sens où ce terme conviendrait mieux à notre époque qu’à n’importe quelle autre. Où que nous prenions pied dans l’histoire, partout nous rencontrons la fermentation, les concepts anciens en lutte avec les nouveaux, et des hommes doués d’une intuition subtile que l’on appelait autrefois prophètes mais qui se contentaient de ressentir et de voir ce qui se passait en eux, le savaient et s’en effrayaient d’ordinaire beaucoup. Si cela continue ainsi, tout va tomber en morceaux, et le monde devra périr. Mais il n’a pas péri, dans la forêt les vieux fûts se sont brisés mais une nouvelle forêt a toujours repoussé : à chaque époque il y eut un monde en décomposition et un monde en devenir.[4] »

Ce seul texte, parmi beaucoup d’autres, permet d’affirmer que Nietzsche n’est pas un décadentiste, alors même qu’à partir de 1883, il fait un usage abondant du terme de « décadence » (en français, de surcroît). Par le simple fait que sa pensée est étrangère à toute téléologie historique, il ne peut souscrire au décadentisme ou à ce qu’on appelle plus volontiers aujourd’hui le « déclinisme ». C’est qu’en réalité, on voit ressurgir de manière récurrente les mêmes dangers à diverses époques : la « décadence » est avant tout, pour Nietzsche, un phénomène d’affaiblissement psychophysiologique, dont la détresse est l’un des signes ou symptômes. Or cela peut arriver n’importe quand et arrive à toutes les époques. Les variations de puissance, les alternances de santé et de morbidité, suivent des cycles, ou plus précisément des « mouvements inverses simultanés », plutôt qu’un vecteur unidirectionnel.

Alors on peut critiquer ou rejeter chez Nietzsche les couples de notions tels que santé et maladie, force et faiblesse, vie ascendante et vie déclinante ; mais si l’on décide par méthode de les appliquer à la situation actuelle, nous risquons d’en arriver à un diagnostic aussi édifiant qu’effrayant… En tout cas, il est fort probable que nous soyons en pleine détresse ou, pour le dire en termes nietzschéens, victimes de chaos pulsionnels que nous sommes incapables de hiérarchiser — autre définition de la « maladie ».

Pour Antoine Compagnon, les antimodernes sont les plus modernes des modernes. Nietzsche est-il, en ce sens, un antimoderne ?

Nietzsche écrit souvent « Nous autres, modernes », il sait parfaitement qu’il est un moderne, fût-ce sous la forme de l’antimodernisme, qui, en effet, comme dit Compagnon, a quelque chose de plus-que-moderne ; on pourrait jouer à dire « moderne, trop moderne », sur le modèle d’Humain, trop humain. Nietzsche est moderne en ce sens qu’il a le sentiment d’arriver à un moment décisif où il faudra préparer un autre avenir que celui auquel semblent nous condamner le poids du passé et la détresse du présent. Comme je le soulignais à l’instant, le présent est pour Nietzsche un problème très inquiétant, et chaque fois que cette inquiétude s’exprime, c’est une inquiétude de moderne. Je pense à la définition minimale que Martuccelli donne de la modernité : « L’interrogation sur le temps actuel et la société contemporaine est le plus petit dénominateur commun de la modernité. Elle est toujours un mode de relation, empli d’inquiétude, face à l’actualité ; c’est dire à quel point elle est indissociable d’un questionnement de nature historique[5] ». Ce qui est antimoderne, dans l’inquiétude moderne de Nietzsche, c’est sa lutte acharnée contre l’optimisme, le progressisme, l’eudémonisme, la Révolution, la démocratie, etc. Mais attention : sa position « anti-Lumières » – pour reprendre le titre de l’ouvrage de Sternhell[6], à mon sens plus important que celui de Compagnon – est très ambiguë. On ne comprend pas, par exemple, sa haine de Rousseau si on ne l’articule pas à sa critique impitoyable du romantisme, qui fut précisément un vaste mouvement anti-Lumières. Sa proximité avec les Lumières, certes très conflictuelle, quasiment sous la forme d’un double bind, ne se limite pas, comme on le répète souvent, à la période dite intermédiaire, celle d’Humain, trop humain. L’anti-romantisme de Nietzsche est un élément essentiel si l’on veut discuter équitablement de la dimension « réactionnaire » de son œuvre.

Vous consacrez de nombreuses pages au rapport que les antimodernes entretiennent avec la modernité. Cependant, vous ne faites pas la distinction entre antimoderne et inactuel. Doit-on faire la différence ?

Si je ne la fais pas dans mon livre, alors c’est qu’elle y manque ! Parce que ce n’est effectivement pas la même chose. En réalité, je crois avoir essayé de faire cette distinction, sans doute pas assez explicitement. Mais je ne peux y avoir échappé pour la simple raison que Nietzsche est tiraillé entre ces deux positions, c’est ce que j’appelle la « bâtardise de l’inactuel ». D’un côté, la lutte (anti)moderne contre le temps présent : « agir contre le temps, donc sur le temps, et, espérons-le, au bénéfice d’un temps à venir[7] », écrit Nietzsche ; de l’autre une lutte contre le temps au sens absolu, c’est-à-dire au bénéfice d’une certaine forme d’éternité. Bien avant l’hypothèse de l’Éternel Retour, Nietzsche cherche à inscrire ou réinscrire de l’éternité dans le temps qui passe. En d’autres termes : s’arracher à l’Histoire pour s’élever au Devenir, ou y plonger. Parce que c’est le Devenir qui est éternel. L’Histoire ressortit au régime de la production et du développement, le Devenir à celui de la création et du hasard. C’est sans doute la part deleuzienne de ma lecture de Nietzsche : la distinction profonde entre l’Histoire et le Devenir, entre le fait et l’événement, entre le progrès et le nouveau… Je crois que c’est l’antimodernité qui le fait polémiquer avec son époque, mais que c’est son inactualité qui l’élève à une intuition de l’éternité. Toutefois, ces deux démarches sont coextensives, c’est pourquoi il n’emploie qu’un seul terme : « unzeitgemäss » signifiant « qui n’est pas conforme à l’époque », mais aussi, en quelque sorte, « qui est incommensurable avec le temps ».

Peut-on dire, à l’inverse de l’impératif rimbaldien qui invite à être « résolument moderne », que la pensée de Nietzsche coïncide plutôt avec la phrase de Roland Barthes : « Tout d’un coup, il m’est devenu indifférent de ne pas être moderne » ?

L’alternative que vous formulez est une autre manière d’exprimer la différence entre l’antimodernité et l’inactualité dont nous venons de parler, et donc d’exprimer la tension prodigieuse, chez Nietzsche, entre la « résolution » et l’« indifférence ». On pourrait la formuler encore autrement : c’est la tension qu’il y a entre la vita activa et la vita contemplativa, entre la préparation de l’avenir et le désir d’éternité. Puisqu’on parlait d’inactualité, il faut dire que, si Nietzsche a beaucoup changé entre les Considérations inactuelles (1873-1876) et la partie de Crépuscule des idoles intitulée « Incursions d’un inactuel » (1888), la tension demeure toutefois entre la descente du lutteur dans l’arène de l’époque et le retrait du contemplatif dans la montagne. Zarathoustra lui aussi monte et descend plusieurs fois. Il y a un fragment posthume fascinant de l’époque du Gai Savoir où Nietzsche se propose de pratiquer, à titre expérimental, une « philosophie de l’indifférence[8] » (qui d’ailleurs doit préparer psychologiquement à la contemplation de l’Éternel Retour). Cette indifférence du sage, c’est ce qu’il admire chez les stoïciens et les épicuriens ; et lorsqu’il les accable au contraire, c’est en vertu de la nécessité de l’action et de la responsabilité du philosophe de l’avenir. Alors oui, il y a quelque chose de rimbaldien chez Nietzsche, surtout dans sa volonté de « se rendre voyant », d’« arriver à l’inconnu par le dérèglement de tous les sens » : c’est au fond un peu ce que prescrit le § 48 du Gai Savoir qui a inspiré le titre de mon ouvrage : le remède contre la détresse, c’est la détresse. Et sans doute y a-t-il aussi chez lui quelque chose de… barthésien : une aversion pour ce qui vous récupère et vous englue, pour le définitif et l’excès de sérieux ; un plaisir du provisoire, de l’aléatoire, de la nuance. En ce sens, Nietzsche comme Barthes sont baudelairiens — et modernes : ils ont bel et bien l’intuition qu’il y a de l’éternel dans l’éphémère.

Enfin, qu’est-ce qui différencie un « nietzschéen de gauche » et un « nietzschéen de droite » dans leur vision du monde moderne ?

Enfin, qu’est-ce qui différencie un « nietzschéen de gauche » et un « nietzschéen de droite » dans leur vision du monde moderne ?

Ah ! La question est un piège, et ce pour plusieurs raisons. D’abord, permettez-moi de m’arrêter un instant sur le terme de « nietzschéen », qui est en lui-même problématique. Si l’on veut seulement dire : spécialiste de Nietzsche, ça a le mérite du raccourci, mais ça ne va pas très loin, et on sent bien que l’adjectif est toujours surdéterminé. Être adepte, disciple, héritier de Nietzsche ? Vivre selon une éthique nietzschéenne ? Bien malin qui peut y prétendre – mais ceux qui font les malins ne manquent pas… Ce qui peut être nietzschéen, c’est, dans nos meilleurs moments, une certaine manière de poser certaines questions, une certaine affinité avec certains types de problèmes ; c’est emprunter une voie sur laquelle on pourra peut-être dire beaucoup de choses nouvelles, mais une voie qui reste ouverte par Nietzsche. C’est évidemment la même chose pour les platoniciens, les spinozistes, les hégéliens, etc. Je crois par ailleurs que le plus intéressant, c’est de savoir avec quelle famille de philosophes on a senti une parenté ou conclu des alliances. Mais ce sont certains aspects, certains réflexes ou instincts qui peuvent être nietzschéens en nous, non pas l’individu tout entier — et heureusement ! Pour mon propre compte, j’ai été assez clair sur ce que j’entends par mon affinité nietzschéenne : c’est simplement le fait que, malgré tout ce qui reste difficile, opaque, voire inaudible ou inacceptable à la lecture de Nietzsche, je continue inlassablement à le lire et à travailler patiemment, parce que j’en ai besoin — en deux sens : je m’en sers et j’aurais du mal à vivre sans. Ce besoin, qui est au fond une affaire strictement personnelle ou, disons, idiosyncrasique, n’est pas une conclusion de mon travail, c’est une prémisse que vient confirmer ou relancer chaque acquis de ce travail. Mais le but de mon travail en revanche, c’est de franchir (et de faire franchir) des seuils ; d’essayer de montrer qu’en un certain point de blocage ou d’intolérabilité, on peut trouver dans l’œuvre même de Nietzsche de quoi débloquer le passage et augmenter le seuil de tolérance ; expliquer et comprendre, pour le dire vite.

Une fois dit ce que j’entends par nietzschéen, il faudrait définir ce qu’on entend en général par la gauche ou la droite, dont les définitions elles-mêmes sont « en crise » aujourd’hui : vous imaginez bien que je ne me lancerai pas dans cet exercice redoutable ! Mais là encore, je ne crois pas qu’un individu tout entier soit de gauche ou de droite, mais que certains aspects, certains réflexes ou instincts peuvent l’être, et qu’ils s’expriment alternativement ou simultanément. Ce serait trop simple ! En tout cas, je crois que, plus on travaille sur Nietzsche, moins les expressions « nietzschéen de droite » et « nietzschéen de gauche » ont de sens. Toutefois, il y a une histoire de la réception de Nietzsche où elles deviennent historiquement pertinentes, bien qu’ambiguës. Je ne peux pas développer ici cette vaste question, qui obligerait à balayer trop grossièrement un siècle et demi de réception. Je n’indiquerai brièvement que deux pôles extrêmes : d’un côté la récupération bien connue et très rapide de Nietzsche par l’extrême-droite puis le fascisme ; de l’autre, l’émergence d’un Nietzsche « post-structuraliste », dans les années soixante-dix, marqué par ce qu’on appelle aujourd’hui, souvent avec un mépris odieux, la « pensée 68 ». Ce nietzschéisme « de gauche » est lui-même ambigu, lorsqu’on voit les critiques adressées à de prodigieux penseurs profondément influencés par Nietzsche, comme Deleuze et Foucault dont certains se demandent s’ils n’ont pas finalement ouvert la voie à un relativisme néo-conservateur – c’est par exemple la position d’Habermas –, à un ultralibéralisme débridé ou tout simplement à une dangereuse dépolitisation de la philosophie — et si vous me demandiez à présent de parler d’Onfray, je ne vous répondrais pas, cela me fatigue d’avance.

Mais revenons à mon idée que droite et gauche ne permettent pas d’aborder Nietzsche avec pertinence. Avant toute chose, il faut être honnête : il y a évidemment un noyau dur qui interdira toujours de rallier Nietzsche à une pensée de gauche — c’est son inégalitarisme profond et son concept fondamental de « hiérarchie ». Le problème n’en demeure pas moins que, si l’on décide de rallier Nietzsche à la droite ou à la gauche, on trouvera toujours de quoi prélever dans ses textes ce dont on a besoin, mais on sera tout aussi sûrement confronté à des éléments absolument inconciliables avec nos convictions ou inappropriables par elles. Ou, à un plus haut niveau d’exigence, on trouvera chez Nietzsche des éléments fondamentaux propres à critiquer très sérieusement certains présupposés idéologiques de la droite comme de la gauche.

Pourquoi nous heurtons-nous toujours à l’impossibilité de fixer Nietzsche d’un côté ou de l’autre ? Ce constat dépasse largement le seul domaine des idéologies politiques. J’essaie de montrer dans mon livre la manière dont Nietzsche ne cesse de renvoyer dos-à-dos, ou de faire jouer l’un contre l’autre, les pôles de systèmes binaires ou les termes de relations biunivoques — pratique très consciente et très maîtrisée que l’on appelle communément les « contradictions » de Nietzsche, et que je nommerais plutôt l’usage du paradoxe, en référence à la définition qu’en donne Deleuze[9]: un ébranlement multidirectionnel initié par un élément rebelle dans un ensemble pré-stabilisé d’identifications univoques — en d’autres termes, des attaques de l’intérieur contre l’alliance du bon sens et du sens commun. Ce caractère multidirectionnel signifie notamment la mobilité des points de vue, leur multiplication autour du phénomène considéré, la nécessité de saisir la multiplicité de ses faces et volte-face pour déjouer le « bon sens » à sens unique du jugement commun (doxa) et l’hypostasie congénitale du langage — C’est ce qu’on entend généralement par le perspectivisme de Nietzsche.

Prenons l’exemple de son rapport très complexe au libéralisme, en son sens classique, qui fait l’objet d’une assez longue analyse dans mon livre. Nietzsche écrit, que « les institutions libérales cessent d’être libérales dès qu’elles sont acquises […] Ces mêmes institutions produisent de tout autres effets aussi longtemps que l’on se bat pour les imposer; alors, elles font puissamment progresser la liberté[10]. » Vous avez là une proposition qui, à la limite, pourrait inspirer aussi bien la gauche révolutionnaire que la droite ultralibérale ! C’est que tout se joue dans la reconfiguration profonde des concepts de puissance et de liberté, de leur exercice et de leur articulation alors même qu’ils sont des processus en devenir et jamais une quantité stable ou une qualité inconditionnée. Alors, pour répondre à votre question : peut-être un « nietzschéen de gauche » insistera-t-il sur les puissances d’émancipation, c’est-à-dire sur la résistance ; et un « nietzschéen de droite », sur l’émancipation des puissances, c’est-à-dire sur l’affirmation. Cela sous-entendrait que l’affect fondamental de la gauche soit un refus des situations intolérables, et l’affect fondamental de la droite, un acquiescement aux choses comme elles vont. Je n’en sais rien, ce que je dis est peut-être idiot. De toute façon, cela ne nous mène pas très loin, car résistance et affirmation sont chez Nietzsche des processus indissociables, comme le sont la destruction des idoles et l’amor fati, ou même le surhumain comme idéal d’affranchissement et l’éternel retour comme loi d’airain. Voilà des injonctions paradoxales ! Mais les meilleurs lecteurs ne séparent jamais les deux, et travaillent au cœur du paradoxe. On parle beaucoup du grand acquiescement nietzschéen à l’existence, et avec raison. Mais il ne faut jamais oublier que le oui n’a aucun sens sans le non, toute une économie des oui et des non, des tenir-à-distance et des laisser-venir-à-soi, comme dit Nietzsche. Toute une micropolitique qui déjoue nos grandes convictions et oblige à des pratiques expérimentales de l’existence, y compris politiques. C’est que Nietzsche, comme tout grand philosophe, se méfie des opinions, et encore davantage des convictions, dans lesquelles il reconnaît toujours un fond de fanatisme. Lui-même rappelle quelque part qu’il n’est pas assez borné pour un système — pas même pour le sien.

[1] « Pourquoi j’écris de si bons livres », § 3

[2] Cf. Jürgen Habermas, « La Modernité : un projet inachevé », in Critique, 1981, t. XXXVII, n° 413, p. 958

[3] Deuxième Considération inactuelle, § 8

[4] FP 4 [212], été 1880

[5] Sociologies de la modernité, Gallimard, 1999, p.9-10

[6] Zeev Sternhell, Les Anti-Lumières : Une tradition du XVIIIe siècle à la Guerre froide, Fayard, 2006 ; Gallimard (édition revue et augmentée), 2010.

[7] Deuxième Considération inactuelle, Préface

[8] FP 11 [141], printemps-automne 1881

[9] Différence et répétition, PUF, 1968, p.289 sq., et Logique du sens, Éditions de Minuit, 1969, p.92 sq.

[10] Crépuscule des idoles, « Incursions d’un inactuel », § 38

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

PHILITT :

PHILITT :

PHILITT :

PHILITT :

Misschien zijn 'tricheurs' als de Franse komiek Dieudonné wel een sterker wapen tegen IS, dan alle Westerse bommenwerpers samen

Misschien zijn 'tricheurs' als de Franse komiek Dieudonné wel een sterker wapen tegen IS, dan alle Westerse bommenwerpers samen

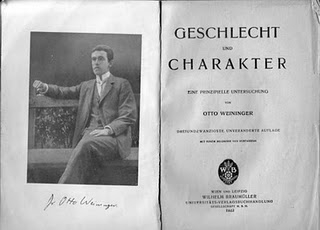

La pensée de Weininger apparaît moins « problématique » si on ne l’appréhende pas comme une description tronquée ou déformée de la réalité, perçue à travers des préjugés « sexistes », mais comme constitutive de modèles ou de types « platoniciens » que cette réalité n’incarne que partiellement. Et c’est d’ailleurs ce qu’il déclare formellement : « La seule voie qui conduise à pouvoir étudier, dans sa réalité, toute opposition de sexe est la reconnaissance du fait que l’homme et la femme ne sont concevables que comme types, et que les hommes et les femmes réels, considérés dans tout ce que leur réalité a de déroutant et qui ne cessera de réalimenter toujours les mêmes controverses, ne sont qu’une composition de ces deux types. » Et pour ce qui est des Juifs, il écrivait : « Lorsque je parle du Juif, je ne veux pas parler d’un type d’homme particulier, mais de l’homme en général en tant qu’il participe de l’idée platonicienne de la judéité. » Ayons donc garde de voir dans la définition des principes masculin et du féminin une annonce de la « théorie du genre » visant à effacer leurs frontières… Loin d’être pour Weininger des créations de la seule culture, la « masculin » et le « féminin », même s’ils ne sont pas exclusifs dans un individu, se donnent bien pour des facteurs agissants et non dérivés ou illusoires. Et, sous ce premier rapport, la théorie weiningerienne se donnerait plutôt comme une antidote à ladite théorie… Il reste que la femme « empirique » étant toujours pour l’homme une tentation, sa rédemption – ou « émancipation » véritable – consisterait pour elle à renoncer à séduire… Et il y a là, sous ce second rapport, un vrai problème d’éducation, affirme Weininger : « Il faut enlever à la femme l’éducation de la femme et ENLEVER À LA MÈRE L’ÉDUCATION DE L’HUMANITÉ. Ce serait la première chose à faire pour mettre la femme au service de l’idée d’humanité, qu’elle a jusqu’ici plus que personne empêchée de se réaliser. » En effet, « le dernier moyen de toute pédagogie maternelle est de menacer la fille rebelle de ne pas trouver de mari. » Un programme dont Weininger note cependant qu’il n’a à peu près aucune chance de se réaliser, ce dont tout mâle non kantien aura tout lieu de se féliciter…

La pensée de Weininger apparaît moins « problématique » si on ne l’appréhende pas comme une description tronquée ou déformée de la réalité, perçue à travers des préjugés « sexistes », mais comme constitutive de modèles ou de types « platoniciens » que cette réalité n’incarne que partiellement. Et c’est d’ailleurs ce qu’il déclare formellement : « La seule voie qui conduise à pouvoir étudier, dans sa réalité, toute opposition de sexe est la reconnaissance du fait que l’homme et la femme ne sont concevables que comme types, et que les hommes et les femmes réels, considérés dans tout ce que leur réalité a de déroutant et qui ne cessera de réalimenter toujours les mêmes controverses, ne sont qu’une composition de ces deux types. » Et pour ce qui est des Juifs, il écrivait : « Lorsque je parle du Juif, je ne veux pas parler d’un type d’homme particulier, mais de l’homme en général en tant qu’il participe de l’idée platonicienne de la judéité. » Ayons donc garde de voir dans la définition des principes masculin et du féminin une annonce de la « théorie du genre » visant à effacer leurs frontières… Loin d’être pour Weininger des créations de la seule culture, la « masculin » et le « féminin », même s’ils ne sont pas exclusifs dans un individu, se donnent bien pour des facteurs agissants et non dérivés ou illusoires. Et, sous ce premier rapport, la théorie weiningerienne se donnerait plutôt comme une antidote à ladite théorie… Il reste que la femme « empirique » étant toujours pour l’homme une tentation, sa rédemption – ou « émancipation » véritable – consisterait pour elle à renoncer à séduire… Et il y a là, sous ce second rapport, un vrai problème d’éducation, affirme Weininger : « Il faut enlever à la femme l’éducation de la femme et ENLEVER À LA MÈRE L’ÉDUCATION DE L’HUMANITÉ. Ce serait la première chose à faire pour mettre la femme au service de l’idée d’humanité, qu’elle a jusqu’ici plus que personne empêchée de se réaliser. » En effet, « le dernier moyen de toute pédagogie maternelle est de menacer la fille rebelle de ne pas trouver de mari. » Un programme dont Weininger note cependant qu’il n’a à peu près aucune chance de se réaliser, ce dont tout mâle non kantien aura tout lieu de se féliciter…

De islam is daar een extreme exponent van, zie Boko Haram, maar ook het ‘blanke’, Europese vooruitgangsdenken van de pionier-ontdekkingsreiziger is mannelijk-imperialistisch. Neen, we huwen geen kindbruidjes (meer) uit, maar de onderliggende macho-cultuur is ook de onze. Poetin, Assad, maar ook Juncker of Verhofstadt of Michel, kampioenen van de democratie, zijn in hetzelfde bedje ziek: voluntaristische ego’s die’ willen ‘scoren’ en van erectie tot erectie evolueren. Altijd is er een doel, een schietschijf, een trofee.

De islam is daar een extreme exponent van, zie Boko Haram, maar ook het ‘blanke’, Europese vooruitgangsdenken van de pionier-ontdekkingsreiziger is mannelijk-imperialistisch. Neen, we huwen geen kindbruidjes (meer) uit, maar de onderliggende macho-cultuur is ook de onze. Poetin, Assad, maar ook Juncker of Verhofstadt of Michel, kampioenen van de democratie, zijn in hetzelfde bedje ziek: voluntaristische ego’s die’ willen ‘scoren’ en van erectie tot erectie evolueren. Altijd is er een doel, een schietschijf, een trofee.

Glucksman a été l’assistant de Raymond Aron et après est devenu maoïste. Pour moi qui ai été élève d’Aron, il y a là quelque chose d’incompréhensible, parce que j’appelle Aron aujourd’hui, avec tendresse et admiration, mon caisson de décontamination. Il m’a permis de sortir des délires révolutionnaires ou messianiques dans lesquels je m’étais égaré. Eh bien, il semble que sur Glucksman, Aron a eu l’effet inverse puisque c’est après avoir été son assistant qu’il est entré dans le plus fanatique des mouvements du vingtième siècle, le maoïsme. Il n’est pas possible qu’Aron, modèle de douceur et d’intelligence critique, ait fait de lui le « disciple » d’un monstre comme Mao devant qui Gengis Khan et Attila sont des enfants de cœur. Comment Glucksman (si sensible à la misère humaine après sa période maoïste) a-t-il pu s’associer à un mouvement qui glorifiait l’un des plus grands tueurs de l’histoire ? Il ne s’agit pas de l’accabler mais de s’interroger sur cette métamorphose. Ce qui me frappe est que ni lui, ni ses amis, dont plusieurs ont été impliqués dans le maoïsme, ne s’interrogent là-dessus. Ils se contentent de dire que Soljenitsyne leur a ouvert les yeux sur le totalitarisme. Tant mieux, mais c’est court.

Glucksman a été l’assistant de Raymond Aron et après est devenu maoïste. Pour moi qui ai été élève d’Aron, il y a là quelque chose d’incompréhensible, parce que j’appelle Aron aujourd’hui, avec tendresse et admiration, mon caisson de décontamination. Il m’a permis de sortir des délires révolutionnaires ou messianiques dans lesquels je m’étais égaré. Eh bien, il semble que sur Glucksman, Aron a eu l’effet inverse puisque c’est après avoir été son assistant qu’il est entré dans le plus fanatique des mouvements du vingtième siècle, le maoïsme. Il n’est pas possible qu’Aron, modèle de douceur et d’intelligence critique, ait fait de lui le « disciple » d’un monstre comme Mao devant qui Gengis Khan et Attila sont des enfants de cœur. Comment Glucksman (si sensible à la misère humaine après sa période maoïste) a-t-il pu s’associer à un mouvement qui glorifiait l’un des plus grands tueurs de l’histoire ? Il ne s’agit pas de l’accabler mais de s’interroger sur cette métamorphose. Ce qui me frappe est que ni lui, ni ses amis, dont plusieurs ont été impliqués dans le maoïsme, ne s’interrogent là-dessus. Ils se contentent de dire que Soljenitsyne leur a ouvert les yeux sur le totalitarisme. Tant mieux, mais c’est court.

Le renoncement, on le comprend vite, concerne en fait un ensemble de paradigmes, dont l’auteur constate que, dans nos sociétés, ils ne sont plus opérants (constate, et non souhaite) et ont fait place à d’autres. A l’âge de la foi succéderait ainsi celui de la sagesse, mais il s’agit en fait d’un retour à ce qui a précédé l’ère judéo chrétienne.

Le renoncement, on le comprend vite, concerne en fait un ensemble de paradigmes, dont l’auteur constate que, dans nos sociétés, ils ne sont plus opérants (constate, et non souhaite) et ont fait place à d’autres. A l’âge de la foi succéderait ainsi celui de la sagesse, mais il s’agit en fait d’un retour à ce qui a précédé l’ère judéo chrétienne. Chantal Delsol ne cherche pas à nous indiquer quel est son positionnement sur l’échelle qui va du pessimisme à l’optimisme ; son propos est de décrire et constater, et non de se réjouir ou de déplorer. Et l’on sait combien cette lucidité est importante pour ne pas s’indigner stérilement, ni se lancer dans des combats désordonnés.

Chantal Delsol ne cherche pas à nous indiquer quel est son positionnement sur l’échelle qui va du pessimisme à l’optimisme ; son propos est de décrire et constater, et non de se réjouir ou de déplorer. Et l’on sait combien cette lucidité est importante pour ne pas s’indigner stérilement, ni se lancer dans des combats désordonnés.

Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over.

Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over.

The hatred of the ‘West’ and of ‘Europe’ is the hatred for a Civilisation that had already reached an advanced state of decay into materialism and sought to impose its primacy by cultural subversion rather than by combat, with its City-based and money-based outlook, ‘poisoning the unborn culture in the womb of the land’. (Spengler, 1971, II, 194). Russia was still a land where there were no bourgeoisie and no true class system but only lord and peasant, a view confirmed by Berdyaev, writing:

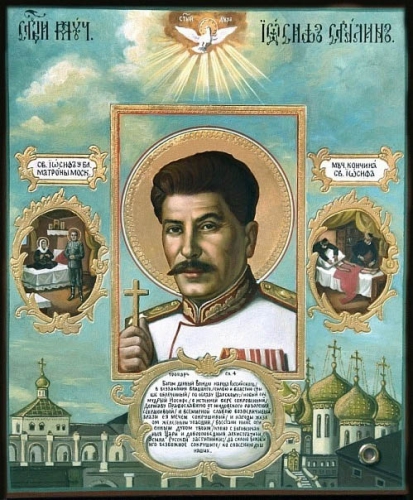

The hatred of the ‘West’ and of ‘Europe’ is the hatred for a Civilisation that had already reached an advanced state of decay into materialism and sought to impose its primacy by cultural subversion rather than by combat, with its City-based and money-based outlook, ‘poisoning the unborn culture in the womb of the land’. (Spengler, 1971, II, 194). Russia was still a land where there were no bourgeoisie and no true class system but only lord and peasant, a view confirmed by Berdyaev, writing:  Spengler states above that the Russians do not ‘fight’ capital. (Ibid., 495). Yet their young soul brings them into conflict with money, as both oligarchy from inside and plutocracy from outside contend with the Russian soul for supremacy. It was something observed by both Gogol and Dostoyevski. The anti-capitalism and ‘world revolution’ of Stalinism took on features that were drawn more from Russian messianism than from Marxism, reflected in the struggle between Trotsky and Stalin. The revival of the Czarist and Orthodox icons, martyrs and heroes and of Russian folk-culture in conjunction with a campaign against ‘ rootless cosmopolitanism’, reflected the emergence of primal Russian soul amidst Petrine Marxism. (Brandenberger, 2002). Today the conflict between two world-views can be seen in the conflicts between Putin and certain ‘oligarchs’ and the uneasiness Putin causes among the West.

Spengler states above that the Russians do not ‘fight’ capital. (Ibid., 495). Yet their young soul brings them into conflict with money, as both oligarchy from inside and plutocracy from outside contend with the Russian soul for supremacy. It was something observed by both Gogol and Dostoyevski. The anti-capitalism and ‘world revolution’ of Stalinism took on features that were drawn more from Russian messianism than from Marxism, reflected in the struggle between Trotsky and Stalin. The revival of the Czarist and Orthodox icons, martyrs and heroes and of Russian folk-culture in conjunction with a campaign against ‘ rootless cosmopolitanism’, reflected the emergence of primal Russian soul amidst Petrine Marxism. (Brandenberger, 2002). Today the conflict between two world-views can be seen in the conflicts between Putin and certain ‘oligarchs’ and the uneasiness Putin causes among the West.

This is pretty good, as denunciations of Stoicism go, seductive in its articulateness and energy, and therefore effective, however uninformed.

This is pretty good, as denunciations of Stoicism go, seductive in its articulateness and energy, and therefore effective, however uninformed.

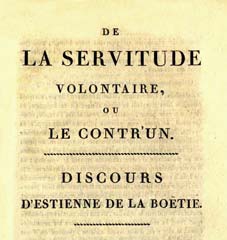

Comment cette tyrannie diffuse opère-t-elle, et nous coupe de toute possibilité d’exercer une quelconque liberté ? Etienne de la Boétie, dans De la servitude volontaire, montre que la liberté est très simple à obtenir : le tyran et ses amis ne pèsent rien face au peuple tout entier. Seulement, pour désirer quelque chose, il faut l’avoir connu. C’est pourquoi le tyran et ses amis tentent par-dessus tout de supprimer la mémoire de la liberté pour asseoir sa tyrannie. Pour cela, pas besoin de prendre la peine de supprimer la mémoire de la masse : l’abrutir suffit largement. Du pain et des jeux, disaient déjà les romains : nous avons les séries télévisuelles de masse, qui servent à saturer l’intelligence avec le non sens et l’affect primaire. Ce qui permet, par exemple, de faire passer tranquillement l'acceptation d'une arithmétique électorale étrange, comme

Comment cette tyrannie diffuse opère-t-elle, et nous coupe de toute possibilité d’exercer une quelconque liberté ? Etienne de la Boétie, dans De la servitude volontaire, montre que la liberté est très simple à obtenir : le tyran et ses amis ne pèsent rien face au peuple tout entier. Seulement, pour désirer quelque chose, il faut l’avoir connu. C’est pourquoi le tyran et ses amis tentent par-dessus tout de supprimer la mémoire de la liberté pour asseoir sa tyrannie. Pour cela, pas besoin de prendre la peine de supprimer la mémoire de la masse : l’abrutir suffit largement. Du pain et des jeux, disaient déjà les romains : nous avons les séries télévisuelles de masse, qui servent à saturer l’intelligence avec le non sens et l’affect primaire. Ce qui permet, par exemple, de faire passer tranquillement l'acceptation d'une arithmétique électorale étrange, comme