Review of Austrian Economics, Volume 8, No. 2 (Summer 1995).

The Alleged Self-Evidence of Equality

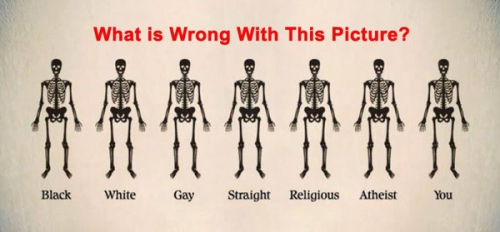

One of the great glories of mankind is that, in contrast to other species, each individual is unique, and hence irreplaceable; whatever the similarities and common attributes among men, it is their differences that lead us to honor, or celebrate, or deplore the qualities or actions of any particular person. It is the diversity, the heterogeneity, of human beings that is one of the most striking attributes of mankind.

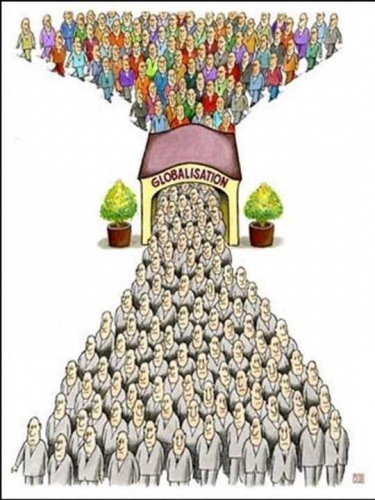

This fundamental heterogeneity makes all the more curious the pervasive modern ideal of “equality.” For “equality” means “sameness” — two entities are “equal” if and only if they are the same thing. X = y only if they are either identical, or they are two entities that are the same in some attribute. If x, y, and z are “equal in length,” it means that each one of them is identical in length, say 3 feet. People, then, can only be “equal” to the extent that they are identical in some attribute: thus, if Smith, Jones and Robinson are each 5 feet, 11 inches in height, then they are “equal” in height. But except for these special cases, people are heterogeneous, and diverse, that is, they are “unequal.” Diversity, and hence “inequality,” is therefore a fundamental fact of the human race. So how do we account for the almost universal contemporary worship at the shrine of “equality,” so much so that it has virtually blotted out other goals or principles of ethics? And taking the lead in this worship have been philosophers, academics, and other leaders and members of the intellectual elites, followed by the entire troop of opinion-molders in modern society, including pundits, journalists, ministers, public school teachers, counselors, human relations consultants and “therapists.” And yet, it should be almost evidently clear that a drive to pursue “equality” starkly violates the essential nature of mankind, and therefore can only be pursued, let alone attempt to succeed, by the use of extreme coercion.

The current veneration of equality is, indeed, a very recent notion in the history of human thought. Among philosophers or prominent thinkers the idea scarcely existed before the mid-eighteenth century; if mentioned, it was only as the object of horror or ridicule. The profoundly anti-human and violently coercive nature of egalitarianism was made clear in the influential classical myth of Procrustes, who “forced passing travelers to lie down on a bed, and if they were too long for the bed he lopped off those parts of their bodies which protruded, while racking out the legs of the ones who were too short. This was why he was given the name of Procrustes [The Racker].”

One of the rare modern philosophers critical of equality made the point that “we can ask whether one man is as tall as another, or we may, like Procrustes, seek to establish equality among all men in this respect.” But our fundamental answer to the question whether equality exists in the real world must be clearly that it does not, and any quest “to establish equality” can only result in the grotesque consequences of any Procrustean effort. How, then, can we not regard Procrustes’s egalitarian “ideal” as anything but monstrous and unnatural? The next logical question is why Procrustes chooses to pursue such a clearly anti-human goal, and one that can only lead to catastrophic results?

In the context of the Greek myth, Procrustes is simply pursuing a lunatic “aesthetic” goal, presumably following his personal star of every person being precisely equal in height to the length of his bed. And yet, this sort of non-argument, this bland assumption that the ideal of equality needs no justification, is endemic among egalitarians. Thus, the argument of the distinguished Chicago economist Henry C. Simons for a progressive income tax was that he found inequality of income “distinctly evil or unlovely.” Presumably, Procrustes might have used the same sort of “argument” in behalf of the “unlovely” nature of inequality of height had he bothered to write an essay advocating his particular egalitarian program. Indeed, most writers simply assume that equality is and must be the overriding goal of society, and that it scarcely needs any supporting argument at all, even a flimsy argument from personal esthetics. Robert Nisbet was and is still correct when he wrote, two decades ago, that

It is evident that … the idea of equality will be sovereign for the rest of this century in just about all circles concerned with the philosophical bases of public policy. … In the past, unifying ideas tended to be religious in substance. There are certainly signs that equality is taking on a sacred aspect among many minds today, that it is rapidly acquiring dogmatic status, at least among a great many philosophers and social scientists.

The Oxford sociologist A. H. Halsey, indeed, was “unable to divine any reason other than ‘malevolence’ why anyone should want to stand” in the way of his egalitarian program. Presumably that “malevolence” could only be diabolic.

“Equality” in What?

Let us now examine the egalitarian program more carefully: what, exactly, is supposed to be rendered equal? The older, or “classic,” answer was monetary incomes. Money incomes were supposed to be made equal.

On the surface, this seemed clear-cut, but grave difficulties arose quickly. Thus, should the equal income be per person, or per household? If wives don’t work, should the family income rise proportionately? Should children be forced to work in order to come under the “equal” rubric, and if so at what age? Furthermore, is not wealthas important as annual income? If A and B each earn $50,000 a year, but A possesses accumulated wealth of $1,000,000 and B owns virtually nothing, their equal incomes scarcely reflect an equality of financial position. But if A is taxed more heavily due to his accumulation, isn’t this an extra penalty on thrift and savings? And how are these problems to be resolved?

But even setting aside the problem of wealth, and focussing on income, can incomes ever really be equalized? Surely, the item to be equalized cannot be simply monetary income. Money is, after all, only a paper ticket, a unit of account, so that the element to be equalized cannot be a mere abstract number but must be the goods and services that can be purchased with that money. The world-egalitarian (and surely the truly committed egalitarian can hardly stop at a national boundary) is concerned to equalize not currency totals but actual purchasing-power. Thus, if A receives an income of 10,000 drachmas a year and B earns 50,000 forints, the equalizer will have to figure out how many forints are actually equivalent to one drachma in purchasing power, before he can wield his equalizing axe correctly. In short, what the economist refers to as “real” and not mere monetary incomes must be equalized for all.

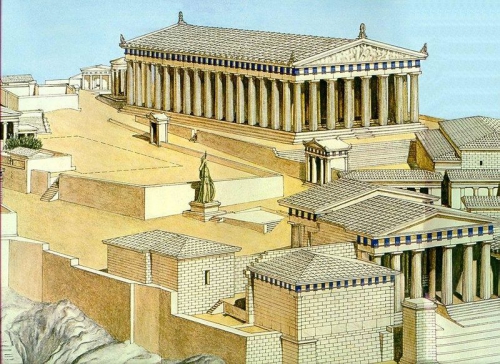

But once the egalitarian agrees to focus on real incomes, he is caught in a thicket of inescapable and insoluble problems. For a large number of goods and services are not homogeneous, and cannot be replicated for all. One of the goods that a Greek may consume with his drachmas is living in, or spending a great deal of time in, the Greek islands. This service (of continuously enjoying the Greek islands) is barred ineluctably to the Hungarian, to the American and to everyone else in the world. In the same way, dining regularly at an outdoor cafe on the Danube is an estimable service denied all the rest of us who do not live in Hungary.

How, then, is real income to be equalized throughout the world? How can the enjoyment of the Greek islands or dining on the Danube be measured, much less gauged by the egalitarian against other services of location? If I am a Nebraskan, and exchange rate manipulations have allegedly equated my income with a Hungarian, how is living in Nebraska to be compared with living in Hungary? The bog gets worse on contemplation. If the egalitarian considers that Danube-enjoyment is somehow superior to enjoying the sights and scenes of Omaha, or a Nebraska farm, on exactly what basis is the egalitarian going to tax the Hungarian and subsidize everyone else? How is he to measure, in monetary terms, the “value of dining on the Danube?” Obviously, the stern rigors of natural law prevent him, much as he would clearly like to do so, from taking the Danube physically and parceling it out equally to every inhabitant throughout the world. And what of people whoprefer the views of and life in a Nebraska farm community to the sins of Budapest? Who, then, is to be taxed and who subsidized and by how much?

Perhaps in desperation, the egalitarian might fall back on the view that everyone’s location reflects his preferences, and that we can therefore simply assume that locations can be neglected in the great egalitarian re-ordering. But while it is true that virtually every spot on the globe is beloved by someone, it is also true that, by and large, some locations are greatly preferred to others. And the location problem occurs within as well as between countries. It is generally acknowledged, both by its residents and by envious outsiders, that the Bay Area of San Francisco is, by climate and topography, far closer to an earthly Paradise than, say West Virginia or Hoboken, New Jersey. Why then don’t these benighted outlanders move to the Bay Area? In the first place, many of them have, but others are barred by the fact of its relatively small size, which (among other, man-made restrictions, such as zoning laws), severely limits migration opportunities. So, in the name of egalitarianism, should we levy a special tax on Bay Area residents and on other designated garden spots, to reduce their psychic income of enjoyment, and then subsidize the rest of us? And how about pouring subsidies into specially designated Dismal Areas, again in the pursuit of equal real incomes? And how is the equalizing government supposed to find out how much people in general, and a fortiori each individual resident, love the Bay Area and how much negative income they suffer from living in, say, West Virginia or Hoboken? Obviously, we can’t ask the various residents how much they love or hate their residential areas, for the residents of every location from San Francisco to Hoboken, would have every incentive to lie — to rush to proclaim to the authorities how much they revile the place where they live.

And location is only one of the most obvious examples of non-homogeneous goods and services which cannot be possibly equalized across the nation or the world.

Moreover, even if wealth and real incomes are both equalized, how are people, their abilities, cultures, and traits, to be equalized? Even if the monetary position of each family is the same, will not children be born into families with very different natures, abilities, and qualities? Isn’t that, to use a notorious egalitarian term, “unfair”? How then can families be made equal, that is, uniform? Doesn’t a child in a cultured and intelligent and wise family enjoy an “unfair” advantage over a child in a broken, moronic, and “dysfunctional” home? The egalitarian must therefore press forward and advocate, as have many communist theorists, the nationalization of all kids from birth, and their rearing in legal and identical state nurseries. But even here the goal of equality and uniformity cannot be achieved. The pesky problem of location will remain, and a state nursery in the Bay Area, even if otherwise identical in every way with one in the wilds of central Pennsylvania, will still enjoy inestimable advantages — or, at the very least, ineradicable differences from the other nurseries. But apart from location, the people — the administrators, nurses, teachers, inside and outside of the various encampments — will all be different, thus giving each child an inescapably different experience, and wrecking the quest for equality for all.

Of course, suitable brainwashing, bureaucratization, and the general robotization and deadening of spirit in the state encampments may help reduce all the teachers and nurses, as well as the children, to a lower and more common denominator, but ineradicable differences and advantages will still remain.

And even if, for the sake of argument, we can assume general equality of income and wealth, other inequalities will not only remain, but, in a world of equal incomes, they will become still more glaring and more important in weighing people. Differences of position, differences of occupation, and inequalities in the job hierarchy and therefore in status and prestige will become even more important, since income and wealth will no longer be a gauge for judging or rating people. Differences in prestige between physicians and carpenters, or between top executives and laborers, will become still more accentuated. Of course, job prestige can be equalized by eliminating hierarchy altogether, abolishing all organizations, corporations, volunteer groups, etc. Everyone will then be equal in rank and decisionmaking power. Differences in prestige could only be eliminated by entering the Marxian heaven and abolishing all specialization and division of labor among occupations, so that everyone would do everything. But in that sort of economy, the human race would die out with remarkable speed.

The New Coercive Elite

When we confront the egalitarian movement, we begin to find the first practical, if not logical, contradiction within the program itself: that its outstanding advocates are not in any sense in the ranks of the poor and oppressed, but are Harvard, Yale, and Oxford professors, as well as other leaders of the privileged social and power elite. What kind of “egalitarianism” is this? If this phenomenon is supposed to embody a massive assumption of liberal guilt, then it is curious that we see very few of this breast-beating elite actually divesting themselves of their worldly goods, prestige, and status, and go live humbly and anonymously among the poor and destitute. Quite the contrary, they seem not to stumble a step on their climb to wealth, fame, and power. Instead, they invariably bask in the congratulations of themselves and their like-minded colleagues of the high-minded morality in which they have all cloaked themselves.

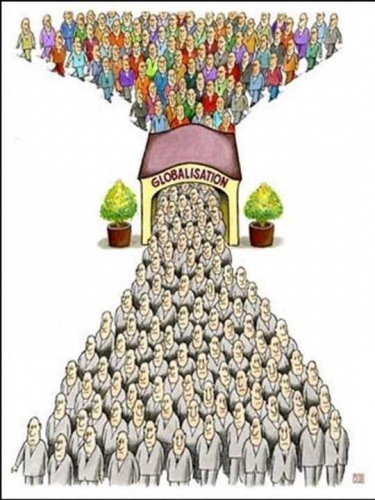

Perhaps the answer to this puzzle lies in our old friend Procrustes. Since no two people are uniform or “equal” in any sense in nature, or in the outcomes of a voluntary society, to bring about and maintain such equality necessarily requires the permanent imposition of a power elite armed with devastating coercive power. For an egalitarian program clearly requires a powerful ruling elite to wield the formidable weapons of coercion and even terror required to operate the Procrustean rack: to try to force everyone into an egalitarian mold. Hence, at least for the ruling elite, there is no “equality” here — only vast inequalities of power, decisionmaking, and undoubtedly, income and wealth as well.

Thus, the English philosopher Antony Flew points out that “the Procrustean ideal has, as it is bound to have, the most powerful attraction for those already playing or hoping in the future to play prominent or rewarding parts in the machinery of enforcement.” Flew notes that this Procrustean ideal is “the uniting and justifying ideology of a rising class of policy advisors and public welfare professionals,” adding significantly that “these are all people both professionally involved in, and owing to their past and future advancement to, the business of enforcing it.”

That the necessary consequence of an egalitarian program is the decidedly inegalitarian creation of a ruthless power elite was recognized and embraced by the English Marxist-Lenist sociologist Frank Parkin. Parkin concluded that “Egalitarianism seems to require a political system in which the state is able to hold in check those social and occupational groups which, by virtue of their skills or education or personal attributes, might otherwise attempt to stake claims to a disproportionate share of society’s rewards. The most effective way of holding such groups in check is by denying the right to organize politically, or, in other ways, to undermine social equality. This presumably is the reasoning underlying the Marxist-Leninist case for a political order based upon the dictatorship of the proletariat.”

But how is it that Parkin and his egalitarian ilk never seem to realize that this explicit assault on “social equality” leads to tremendous inequalities of power, decisionmaking authority, and, inevitably, income and wealth? Indeed, why is this seemingly obvious question never so much as raised among them? Could there be hypocrisy or even deceit at work?

The Iron Law of Oligarchy

One reason that an egalitarian political program must lead to the installation of a new coercive political elite is that hierarchies and inequalities of decisionmaking are inevitable in any human organization that achieves any degree of success in attaining its goals.

Robert Michels first observed this Iron Law of Oligarchy, in seeing the Social Democratic parties of Europe in the late nineteenth century, officially committed to equality and abolition of the division of labor, in practice being run by a small ruling elite. And there is nothing, outside of egalitarian fantasies, wrong with this universal human fact, or law of nature. In any group or organization, there will arise a core leadership of those most able, energetic, and committed to the organization, I know, for example, of a small but increasingly successful volunteer, musical society in New York. Although there is a governing board elected annually by its members, the group has for years been governed by the benevolent but absolute autocratic rule of its president, a lady who is highly intelligent, innovative, and, though employed full-time elsewhere, able and willing to devote an incredible amount of time and energy to this organization. Several years ago some malcontent challenged this rule, but the challenge was easily beaten back, since every rational member knew full well that she was absolutely vital to the success of the organization.

Not only is there nothing wrong with this situation, but blessed be the group where such a person exists and can come to the fore! There is, in fact, everything right about a rise to power, in voluntary or market organizations, of the most able and efficient, of a “natural aristocracy,” in Jeffersonian terms. Democratic voting, at its best when shareholders of a corporation vote the aliquot share of their ownership of a company’s assets, is only secondarily useful as a method of displacing natural aristocrats or “monarchs” gone sour, or, in Aristotelian terms, who have deteriorated from “monarch” to “tyrants.” Democratic voting, therefore, is even at its best scarcely even a primary good, let alone a good-in-itself to be glorified or even deified.

During a period in the mid-1960s, the New Left, before it hived off into Stalinism and bizarre violence, was trying to put into effect a new political theory: participatory democracy. Participatory democracy soundedlibertarian, since the idea was that majority rule, even in a private and voluntary organization, is “coercive,” and therefore that all decisions of that organization must be stripped of oligarchic rule. Every member would then participate equally, and furthermore, every member would have to give his or her consent to any decision. In a sense, this Unanimity Rule foreshadowed and paralleled the Unanimity Rule of James Buchanan and of Paretian “welfare economics.”

A friend of mine was teaching about the history of Vietnam at the New Leftist Free University of New York, originally a scholarly organization founded by a young sociologist couple. The Free University set out to govern itself on participatory democratic principles. The governing body, the board of the Free University, therefore consisted of the “staff” — the sociologist couple — plus any students (who paid a modest tuition) or teachers (unpaid) who cared to attend the board’s meetings. All were equal, the founding staff was no more powerful than any teacher or wandering student. All decisions of the school, from courses taught, room assignments, and on down to whether or not the school needed a paint job and what color the paint should be, were decided by the board, never by voting but always by unanimous consent.

Here was a fascinating sociological experiment. Not only, as one might expect, were very few decisions of any sort reached, but the “board meeting” stretched on endlessly, so that the board meeting expanded to becomelife itself — a kind of Sartrian No Exit situation. When my friend left the perpetual meeting each day at 5:00 pm to go home, he was accused of abandoning the meeting and thereby “betraying the collective” and the school by attempting to live some sort of private life outside the meeting. Perhaps this is what the current leftist political theorists who exalt the “public life” and “civic virtue” have in mind: private lives being forsaken on behalf of the permanent floating “civically virtuous” collective meeting of “the community!”

It should not come as any surprise to reveal that the Free University of New York did not last very long. In point of fact, it quickly deteriorated from a scholarly outfit to the “teaching” of New Left astrology, tarot cards, channeling, eurythmics, and whatnot as the scholars all fled before the mass man, or as a sociological Gresham’s Law came into action. (As for the founding couple, the female wound up in jail for unsuccessfully trying to blow up a bank, while the male, getting increasingly glassy-eyed, in a feat of sociological legerdemain, talked himself into the notion that the only moral occupation for a revolutionary sociologist was that of radio repairman.)

New Left educational theory, during that period, also permeated more orthodox colleges throughout the country. In those days, the doctrine was not so much that teaching had to be “politically correct,” but that the normal teacher-student relation was evil because inherently unequal and hierarchical. Since the teacher is assumed to know more than the student, therefore, the truly egalitarian and “democratic” form of education, the way to put teacher and student on an equal footing, is to scrap course content altogether and to sit around discussing the student’s “feelings.” Not only are all feelings in some sense equal, at least in the sense that one person’s feelings cannot be considered “superior” to others, but those feelings are supposedly the only subjects “relevant” to students. One problem that this doctrine raised, of course, is why the students, or more correctly their long-suffering parents, should pay faculty who are qualified in knowledge of economics, sociology, or whatever but not in psychotherapy, to sit around gabbing about the students’ feelings?

Institutionalizing Envy

As I have elaborated elsewhere, the egalitarian impulse, once granted legitimacy, cannot be appeased. If monetary or real incomes become equalized, or even if decisionmaking power should be equalized, otherdifferences among persons become magnified and irritating to the egalitarian: inequalities in looks, intelligence, and so on. One intriguing point however: there are some inequalities that never seem to outrage egalitarians, namely income inequalities among those who directly supply consumer services — notably athletes, movie and TV entertainers, artists, novelists, playwrights, and rock musicians. Perhaps this is the reason for the persuasive power of Robert Nozick’s famous “Wilt Chamberlain” example in defense of market-determined incomes. There are two possible explanations: (1) that these consumer values are held by the egalitarians themselves and are therefore considered legitimate, or (2) that, with the exception of athletics, these are fields implicitly recognized as dominated nowadays by forms of entertainment and art that require no real talent. Differences in income, therefore, are equivalent to winning at a lottery, and lottery or sweepstake winners are universally lauded as purely “lucky,” with no envy of superior attributes to be attached to them.

The German sociologist Helmut Schoeck has pointed out that modern egalitarianism is essentially an institutionalization of envy. In contrast to successful or functional societies, where envy is always considered a shameful emotion, egalitarianism sets up a pervasive attitude that the exciting of envy by manifesting some form of superiority is considered the greatest evil. Or, as Schoeck put it, “the highest value is envy-avoidance.” Indeed, communist anarchists explicitly aim to stamp out private property because they believe that property gives rise to inequality, and therefore to feelings of envy, and hence “causes” crimes of violence against those with more property. But as Schoeck points out, economic egalitarianism would then not be sufficient: and compulsory uniformity of looks, intelligence, etc. would have to follow.

But even if all possible inequalities and difference among individuals could somehow be eradicated, Helmut Schoeck adds, there still would remain an irreducible element: the mere existence of individual privacy. As Schoeck puts it, “if a man really makes use of his right to be alone, the annoyance, envy, and mistrust of his fellow citizens will be aroused. … Anyone who cuts himself off, who draws his curtains and spends any length of time outside the range of observation, is always seen as a potential heretic, a snob, a conspirator.” After some amusing comments about suspicion of the “sin of privacy” in American culture, particularly in the widespread open-door policy among academics, Schoeck turns to the Israeli kibbutz and to its widely and overly revered philosopher, Martin Buber. Buber maintained that to constitute a “real community,” the absolutely equal members of the kibbutz must “have mutual access to one another and [be] ready for one another.” As Schoeck interprets Buber: “a community of equals, where no one ought to envy anyone else, is not guaranteed by absence of possessions alone, but requires mutual possession, in purely human terms. … Everyone must always have time for everybody else, and anyone who hoards his time, his leisure hours, and his privacy excludes himself.”

The New Group Egalitarianism

So far we have been describing what may be called “classical,” or the Old, egalitarianism, aimed to make all individuals in some sense equal, generally in income and wealth. But in recent years, we have all been subjected to a burgeoning and accelerating New Egalitarianism, which stresses not that every individual must be made equal, but that the income, prestige, and status of a seemingly endless proliferation of “groups” must be made equal to each other.

At first blush, it might seem that the new group egalitarianism is less extreme or unrealistic than the old individual creed. For if every individual is really totally equal to every other in income, wealth, or status, then it will follow logically that any subset of groups of such individuals will be equal as well. Shifting emphasis from individual to group egalitarianism must therefore imply settling for a less severe degree of equality. But this conclusion misconceives the whole point of egalitarianism, old or new. No egalitarian actually expects ever to be in a state of absolute equality, still less does he begin his analysis with that starting point.

Perhaps we can illuminate the true nature of the egalitarian drive, and the relationship between the Old and the New movements, by focusing not, as is usually done, on their patently absurd and self-contradictory ostensible goals of equality, but on the required means to attain such goals: namely the coming to power of the Procrustean State apparatus, the new coercive elite. Who are the Procrustean elite? That is, which groups are needed to constitute such an elite? By an odd coincidence, the makeup of such groups seems to correspond, almost one-to-one, to those people who have been most enthusiastic about egalitarianism over the years: intellectuals, academics, opinion-molders, journalists, writers, media elites, social workers, bureaucrats, counselors, psychologists, personnel consultants, and especially for the ever-accelerating new group egalitarianism, a veritable army of “therapists” and sensitivity trainers. Plus, of course, ideologues and researchers to dream up and discover new groups that need egalitarianizing.

If these groups of what might very loosely be called the “intelligentsia” are the driving force of the Old and the New embodiments of egalitarianism, how does this minority hope to convince a majority of the public to turn over an apparatus of despotic power into its hands? In the first place, the intellectuals start with a huge advantage far beyond their relative smallness of number: they are dominant within the “opinion-molding class” that attempts to shape public opinion, and often succeeds in that task. As is always the case, the State rulers need the support of an opinion-molding class to engineer the consent of the public. In the Old Egalitarianism, the would-be rulers sought to bring into their camp, in the first place, the seeming economic beneficiaries of the egalitarian program — the lower-income groups who would be recipients of much of the transfer, or soaking of the wealthy (part of the transfer from the rich, of course, would go into the coffers of the Procrustean elites themselves, the brokers of the egalitarian wealth-transfer). As for the plundered wealthy,they would be induced to support the system by being persuaded that they must expiate their “guilt” at being wealthier than their impoverished fellow-citizens. Infusion of guilt is a classic path of persuading the wealthy victim to surrender his wealth without a struggle.

Any success in the Old Egalitarian program led, of course, to expansion of the number, the wealth, and the power of the new Procrustean elite, resulting in an ever lower income definition of “the wealthy” to be plundered, and an ever higher definition of “the poor” to be subsidized. This process has been all too clearly at work in the United States and in the western world in the twentieth century. From being confined to the highest income brackets, for example, the payers of income tax have descended into the ranks of the far more numerous middle class. At the same time, the “poverty level” to be subsidized and cosseted has marched steadily upward, as the “poverty line” is continually revised upward, and the subsidized escalate from the very poor to the unemployed to the more affluent “working poor.”

From the point of view of the egalitarians, however, the weakness of the Old Egalitarianism is that it has only one category of beneficiary — “the poor,” however defined, and one category of the plundered, “the rich.” (That they themselves are notable beneficiaries is always discreetly left hidden behind the veil of altruism and alleged expertise. For anyone else to bring up to the point would be considered ungentlemanly, or, even worse, to be engaging in the much-derided “conspiracy theory of history.”)

In the light of this analysis, then, let us examine the New Group Egalitarianism. As we all know, the new egalitarians search for “oppressed” groups who are lower in income, status, or prestigious jobs than others, who become the designated “oppressors.” In classic leftism or Marxism, there was only one alleged “oppressed group,” the proletariat. Then the floodgates were opened, and the ranks of the designated oppressed, or “accredited victims,” have proliferated seemingly without end. It began with the oppressed blacks, and then in rapid succession, there were woman, Hispanics, American Indians, immigrants, “the disabled,” the young, the old, the short, the very tall, the fat, the deaf, and so on ad infinitum. The point is that the proliferation is, in fact, endless. Every individual “belongs” to an almost infinite variety of groups or classes. Take, for example, a Mr. John Smith. He may belong to an enormous number of classes: e.g., people named “Smith,” people named “John,” people of height 5 feet 10 inches, people of height under 6 feet, people who live in Battle Creek, Michigan, people who live north of the Mason-Dixon line, people with an income of … etc. And among all these classes, there are an almost infinite number of permutations. It has gotten to the point where the only “theory” of “oppression” needed is if any such group has a lower income or wealth or status than other groups. The below-average group, whatever it is, is then by definition, “discriminated against” and therefore is designated as oppressed. Whereas any group above the average is, by definition, doing the discriminating, and hence a designated oppressor.

Every new discovery of an oppressed group can bring the egalitarian more supporters in his drive to power, and also creates more “oppressors” to be made to feel guilty. All that is needed to find ever-new sources of oppressors and oppressed is data and computers, and, of course, researchers into the phenomena — the researchers themselves constituting happy members of the Procrustean elite class.

The charm of group egalitarianism for the intellectual-technocratic-therapeutic-bureaucratic class, then, is that it provides a nearly endless and accelerating supply of oppressed groups to coalesce around the egalitarians’ political efforts. There are, then, far more potential supporters to rally around the cause than could be found if only “the poor” were being exhorted to seek and promote their “rights.” And as the cause expands, of course, there is a multiplication of jobs and an acceleration of taxpayer funding flowing into the coffers of the Procrustean ruling elite, a not-accidental feature of the egalitarian drive. Joseph Sobran recently wrote that, in the current lexicon, “need” is the desire of people to loot the wealth of others; “greed” is the desire of those others to keep the money they have earned; and “compassion” is the function of those who negotiate the transfer. The ruling elite may be considered the “professional compassionate” class. It is easy, of course, to be conspicuously “compassionate” if others are being forced to pay the cost.

This acceleration of New Egalitarianism leads, relatively quickly, to inherent problems. First, there is what Mises called “the exhaustion of the reserve fund,” that is, the resources available to be plundered and to pay for all this. As a corollary, along with this exhaustion may come the “backlash,” when the genuinely oppressed — the looted, those whom William Graham Sumner once called the Forgotten Man — may get fed up, rise up and throw off the shackles which have bound this Gulliver and induced him to shoulder the expanding parasitic burdens.

The New Egalitarian Elite

We conclude with one of the great paradoxes of our time: that the powerful and generally unchallenged cry for “equality” is driven by the decidedly inegalitarian aim of climbing on its back to increasingly absolute political power, a triumph which will of course make the egalitarians themselves a ruling elite in income and wealth as well as power. Behind the honeyed but patently absurd pleas for equality is a ruthless drive for placing themselves at the top of a new hierarchy of power. The new intellectual and therapeutic elite impose their rule in the name of “equality.” As Antony Flew tellingly puts it: equality “serves as the unifying and justifying ideology of certain social groups … the Procrustean ideal has, as it is bound to have, the most powerful attraction for those already playing or hoping in the future to play prominent or rewarding parts for the machinery of its enforcement.”

In a brilliant and mordant critique of the current ascendancy of left-liberal intellectuals, the great economist and sociologist Joseph Schumpeter, writing as early as World War II, pointed out that nineteenth-century free-market “bourgeois” capitalism, in sweeping away aristocratic and feudal political structures, and challenging the “irrational” role of religion and the heroic virtues in behalf of the utilitarianism of the counting-house, foolishly managed to destroy the necessary protections for their own free-market order. As Schumpeter vividly puts it: “The stock exchange is a poor substitute for the Holy Grail.” Schumpeter continues:

Capitalist rationality does not do away with sub- or super-rational impulses. It merely makes them get out of hand by removing the restraint of sacred or semi-sacred tradition. In a civilization that lacks the means and even the will to guide them, they will revolt. … Just as the call for utilitarian credentials has never been addressed to kings, lords, and popes in a judicial frame of mind that would accept the possibility of a satisfactory answer, so capitalism stands its trial before judges who have the sentence of death in their pockets. They are going to pass it, whatever the defense they may hear; the only success victorious defense can possibly produce is a change in the indictment.

The capitalist process, Schumpeter adds, “tends to wear away protective strata, to break down its own defenses, to disperse the garrisons of its entrenchments.” Moreover,

capitalism creates a critical frame of mind which, after having destroyed the moral authority of so many other institutions, in the end turns against its own; the bourgeois finds to his amazement that the rationalist attitude does not stop at the credentials of kings and popes but goes on to attack private property and the whole scheme of bourgeois values.

As a result, Schumpeter points out, “the bourgeois fortress becomes politically defenseless.” But,

defenseless fortresses invite aggression especially if there is rich booty in them. … No doubt it is possible, for a time, to buy them off. But this resource fails as soon as they discover that they can have all.

Schumpeter notes that his explanation for rising hostility to free market capitalism at a time when it had brought to the world unprecedented freedom and prosperity, is confirmed by the striking fact that,

there was very little hostility [to free-market capitalism] on principle as long as the bourgeois position was safe, although there was then much more reason for it; it [the hostility] spread pari passu with the crumbling of the protective walls.

At the head and the nerve center of the driving force to take advantage of this bourgeois weakness have been the left-liberal intellectuals, a class multiplied vastly in number by the prosperity of capitalism and particularly by continuing and vast government subsidies to public schools, to formal literacy, and to modern communications. These subsidies not only helped create a huge class of intellectuals, but also have provided them — as well as the state apparatus — for the first time in history with the tools necessary to indoctrinate the mass of the public at large. Moreover, since the bourgeois free-market order is deeply committed to the rights of private property, and hence to freedom of speech and the press, by the very principles at the heart of their system, they find it impossible to “discipline” the intellectuals, in Schumpeter’s phrase “to bring the intellectuals to heel.” Thus, the intellectuals, nurtured in the bosom of free-market capitalist society, take the earliest opportunity to turn savagely on their benefactors, “to nibble at the foundations of capitalist society,” and finally to organize a drive for power using their virtual monopoly of the opinion-molding process by perverting the original meaning of such words as “freedom,” “rights,” and “equality.” Perhaps the most hopeful aspect of this process is that, as the late sociologist Christopher Lasch points out in his new work, the values, attitudes, principles and programs of the increasingly arrogant liberal intellectual elite is so out of sync, so much in conflict, with those of the mass of the American public, that a powerful counter-revolutionary backlash is apt to occur, and indeed at this very moment seems in the process of spreading rapidly throughout the country.

In his sparkling essay, “Equality as a Political Weapon,” Samuel Francis gently chides conservative opponents of egalitarianism for expending a large amount of energy in philosophical, historical, and anthropological critiques of the concept and the doctrine of equality. This entire “formal critique,” however rewarding and illuminating, declares Francis, is really wide of the mark:

In a sense, I believe that it has been beating a dead horse — or more strictly, a dead unicorn, a beast that exists only in legend. The flaw, I believe, is that the formal doctrine of equality is itself nonexistent or at least unimportant.

How so? The doctrine of equality is “unimportant,” Francis explains, “because no one, save perhaps Pol Pot or Ben Wattenberg, really believes in it, and no one, least of all those who profess it most loudly, is seriously motivated by it.” Here Francis quotes the great Pareto:

a sentiment of equality … is related to the direct interests of individuals who are bent in escaping certain inequalities not in their favor, and setting up new inequalities that will be in their favor, the latter being their chief concern.

Francis then points out that “the real meaning” of the “doctrine of equality,” as well as its “real power as a social and ideological force,” cannot be countered by merely formal critiques. For:

the real meaning of the doctrine of equality is that it serves as a political weapon, to be unsheathed whenever it is useful for cutting down barriers, human or institutional, to the power of those groups that wear it on their belts.

To mount an effective response to the reigning egalitarianism of our age, therefore, it is necessary but scarcely sufficient to demonstrate the absurdity, the anti-scientific nature, the self-contradictory nature, of the egalitarian doctrine, as well as the disastrous consequences of the egalitarian program. All this is well and good. But it misses the essential nature of, as well as the most effective rebuttal to, the egalitarian program: to expose it as a mask for the drive to power of the now ruling left-liberal intellectual and media elites. Since these elites are also the hitherto unchallenged opinion-molding class in society, their rule cannot be dislodged until the oppressed public, instinctively but inchoately opposed to these elites, are shown the true nature of the increasingly hated forces who are ruling over them. To use the phrases of the New Left of the late 1960s, the ruling elite must be “demystified,” “delegitimated,” and “desanctified.” Nothing can advance their desanctification more than the public realization of the true nature of their egalitarian slogans.

The Best of Murray N. Rothbard

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

On le pressent, une fois ce diagnostic établi, la solution proposée par Lasch n’a rien de bien « transgressif », en apparence du moins. Lasch propose simplement de retrouver le sens des limites. Sur ce point, il convient cependant de ne pas se méprendre. Que l’individu doive retrouver le sens des limites n’a jamais signifié pour Lasch l’impératif de rétablir par la force l’autorité qui châtie et punit aveuglément. C’est ici que des « conservateurs droitiers » tels qu’Alain Finkielkraut ou Pascal Bruckner cessent de de pouvoir se référer sans mauvaise foi à Lasch. La permissivité et la peur du conflit d’une part, l’autorité qui ne sait qu’interdire d’autre part, forment pour Lasch deux faces d’une même médaille. A moins que les normes éthiques, suggère-t-il dans Le Moi assiégé, ne s’enracinent dans une identification émotionnelle avec les autorités qui les font respecter, elles n’inspireront rien de plus qu’une obéissance servile.

On le pressent, une fois ce diagnostic établi, la solution proposée par Lasch n’a rien de bien « transgressif », en apparence du moins. Lasch propose simplement de retrouver le sens des limites. Sur ce point, il convient cependant de ne pas se méprendre. Que l’individu doive retrouver le sens des limites n’a jamais signifié pour Lasch l’impératif de rétablir par la force l’autorité qui châtie et punit aveuglément. C’est ici que des « conservateurs droitiers » tels qu’Alain Finkielkraut ou Pascal Bruckner cessent de de pouvoir se référer sans mauvaise foi à Lasch. La permissivité et la peur du conflit d’une part, l’autorité qui ne sait qu’interdire d’autre part, forment pour Lasch deux faces d’une même médaille. A moins que les normes éthiques, suggère-t-il dans Le Moi assiégé, ne s’enracinent dans une identification émotionnelle avec les autorités qui les font respecter, elles n’inspireront rien de plus qu’une obéissance servile.  Dans une enquête de grande ampleur, qui évoque notamment le radicalisme chrétien d’Orestes Brownson (1803-1876), le transcendantalisme de Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), le mouvement de résistance non violente de Martin Luther King (1929-1968), en passant par le socialisme de guilde de George Douglas Howard Cole (1889-1959), Lasch met en évidence tout un gisement de valeurs relatives à l’humanisme civique, dont les Etats-Unis et plus largement le monde anglo-saxon ont été porteurs en résistance à l’idéologie libérale du progrès. Il retrouve, par-delà les divergences entre ces œuvres, certains constances : l’habitude de la responsabilité associée à la possession de la propriété ; l’oubli volontaire de soi dans un travail astreignant ; l’idéal de la vie bonne, enracinée dans une communauté d’appartenance, face à la promesse de l’abondance matérielle ; l’idée que le bonheur réside avant tout dans la reconnaissance que les hommes ne sont pas faits pour le bonheur. Le regard historique de Lasch, en revenant vers cette tradition, n’incite pas à la nostalgie passéiste pour un temps révolu. A la nostalgie, Lasch va ainsi opposer la mémoire. La nostalgie n’est que l’autre face de l’idéologie progressiste, vers laquelle on se tourne lorsque cette dernière n’assure plus ses promesses. La mémoire quant à elle vivifie le lien entre le passé et le présent en préparant à faire face avec courage à ce qui arrive. Au terme du parcours qu’il raconte dans Le Seul et Vrai Paradis, le lecteur garde donc en mémoire le fait historique suivant : il a existé un courant radical très fortement opposé à l’aliénation capitaliste, au délabrement des conditions de travail, ainsi qu’à l’idée selon laquelle la productivité doit augmenter à la mesure des désirs potentiellement illimités de la nature humaine, mais pourtant tout aussi méfiant à l’égard de la conception marxiste du progrès historique. Volontiers raillée par la doxa marxiste pour sa défense « petite bourgeoise » de la petite propriété, tenue pour un bastion de l’indépendance et du contrôle sur le travail et les conditions de vie, la pensée populiste visait surtout l’idole commune des libéraux et des marxistes, révélant par là même l’obsolescence du clivage droite/gauche : le progrès technique et économique, ainsi que l’optimisme historique qu’il recommande. Selon Lasch qui, dans le débat entre Marx et Proudhon, opte pour les analyses du second, l’éthique populiste des petits producteurs était « anticapitaliste, mais ni socialiste, ni social-démocrate, à la fois radicale, révolutionnaire même, et profondément conservatrice ».

Dans une enquête de grande ampleur, qui évoque notamment le radicalisme chrétien d’Orestes Brownson (1803-1876), le transcendantalisme de Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), le mouvement de résistance non violente de Martin Luther King (1929-1968), en passant par le socialisme de guilde de George Douglas Howard Cole (1889-1959), Lasch met en évidence tout un gisement de valeurs relatives à l’humanisme civique, dont les Etats-Unis et plus largement le monde anglo-saxon ont été porteurs en résistance à l’idéologie libérale du progrès. Il retrouve, par-delà les divergences entre ces œuvres, certains constances : l’habitude de la responsabilité associée à la possession de la propriété ; l’oubli volontaire de soi dans un travail astreignant ; l’idéal de la vie bonne, enracinée dans une communauté d’appartenance, face à la promesse de l’abondance matérielle ; l’idée que le bonheur réside avant tout dans la reconnaissance que les hommes ne sont pas faits pour le bonheur. Le regard historique de Lasch, en revenant vers cette tradition, n’incite pas à la nostalgie passéiste pour un temps révolu. A la nostalgie, Lasch va ainsi opposer la mémoire. La nostalgie n’est que l’autre face de l’idéologie progressiste, vers laquelle on se tourne lorsque cette dernière n’assure plus ses promesses. La mémoire quant à elle vivifie le lien entre le passé et le présent en préparant à faire face avec courage à ce qui arrive. Au terme du parcours qu’il raconte dans Le Seul et Vrai Paradis, le lecteur garde donc en mémoire le fait historique suivant : il a existé un courant radical très fortement opposé à l’aliénation capitaliste, au délabrement des conditions de travail, ainsi qu’à l’idée selon laquelle la productivité doit augmenter à la mesure des désirs potentiellement illimités de la nature humaine, mais pourtant tout aussi méfiant à l’égard de la conception marxiste du progrès historique. Volontiers raillée par la doxa marxiste pour sa défense « petite bourgeoise » de la petite propriété, tenue pour un bastion de l’indépendance et du contrôle sur le travail et les conditions de vie, la pensée populiste visait surtout l’idole commune des libéraux et des marxistes, révélant par là même l’obsolescence du clivage droite/gauche : le progrès technique et économique, ainsi que l’optimisme historique qu’il recommande. Selon Lasch qui, dans le débat entre Marx et Proudhon, opte pour les analyses du second, l’éthique populiste des petits producteurs était « anticapitaliste, mais ni socialiste, ni social-démocrate, à la fois radicale, révolutionnaire même, et profondément conservatrice ».

Les valeurs : un argument terroriste

Les valeurs : un argument terroriste Les valeurs contre la vertu

Les valeurs contre la vertu L’œuvre de Thomas Molnar, quand elle est traduite en français, ce qui n'est même pas le cas de l'ouvrage qu'il a consacré à Georges Bernanos, reste encore fort peu connue. Il faut s'en étonner et s'en affliger, car la lecture de l'ouvrage qu'il a consacré à la contre-révolution, en ces temps d'inflation des gloses universitaires, est un réel plaisir : tout est fluide, la moindre phrase n'est pas immédiatement flanquée d'une note s'étendant sur plusieurs pages et dévorant la substance même de l'ouvrage pour se perdre dans le pullulement fantomatique des langages seconds, et des langages au cube des langages seconds.

L’œuvre de Thomas Molnar, quand elle est traduite en français, ce qui n'est même pas le cas de l'ouvrage qu'il a consacré à Georges Bernanos, reste encore fort peu connue. Il faut s'en étonner et s'en affliger, car la lecture de l'ouvrage qu'il a consacré à la contre-révolution, en ces temps d'inflation des gloses universitaires, est un réel plaisir : tout est fluide, la moindre phrase n'est pas immédiatement flanquée d'une note s'étendant sur plusieurs pages et dévorant la substance même de l'ouvrage pour se perdre dans le pullulement fantomatique des langages seconds, et des langages au cube des langages seconds. Il serait pour le moins difficile de dénier à Thomas Molnar la justesse de tels propos, y compris si nous devions tracer quelque parallèle avec notre propre époque, où triomphent ces «intellectuels des classes moyennes» (p. 108) qui à force de cocktails et de mauvais livres cherchent à s'émanciper de leur caste, pour fréquenter les grands, ou ceux qu'ils considèrent comme des grands, tout en n'affectant qu'un souci fallacieux de ce qu'ils méprisent au fond par-dessus tout et qu'ils sont généralement vite prêts à qualifier du terme méprisant (dans leur bouche) de peuple. Ce peuple est instrumentalisé, et ce n'est que par tactique que les intellectuels révolutionnaires peuvent donner l'impression de le flatter, voire de le respecter : «Ce qui est essentiel, les révolutionnaires ont rapidement compris que bien que 1789 ait ouvert la porte du pouvoir aux masses, celles-ci ne l'utiliseront jamais pour elles-mêmes, mais permettront seulement qu'il passe entre les mains de ces nouveaux privilégiés que sont les entraîneurs de foules, les faiseurs d'opinion et les idéologues» (p. 119). Finalement, la révolution n'est pas grand-chose, si nous nous avisions de la séparer de ses béquilles, que Thomas Molnar appelle «sa méthode de propagation dans tous les coins de la société» (p. 110) et, surtout, l'élevage quasiment industriel de ces intellectuels si remarquablement définis par

Il serait pour le moins difficile de dénier à Thomas Molnar la justesse de tels propos, y compris si nous devions tracer quelque parallèle avec notre propre époque, où triomphent ces «intellectuels des classes moyennes» (p. 108) qui à force de cocktails et de mauvais livres cherchent à s'émanciper de leur caste, pour fréquenter les grands, ou ceux qu'ils considèrent comme des grands, tout en n'affectant qu'un souci fallacieux de ce qu'ils méprisent au fond par-dessus tout et qu'ils sont généralement vite prêts à qualifier du terme méprisant (dans leur bouche) de peuple. Ce peuple est instrumentalisé, et ce n'est que par tactique que les intellectuels révolutionnaires peuvent donner l'impression de le flatter, voire de le respecter : «Ce qui est essentiel, les révolutionnaires ont rapidement compris que bien que 1789 ait ouvert la porte du pouvoir aux masses, celles-ci ne l'utiliseront jamais pour elles-mêmes, mais permettront seulement qu'il passe entre les mains de ces nouveaux privilégiés que sont les entraîneurs de foules, les faiseurs d'opinion et les idéologues» (p. 119). Finalement, la révolution n'est pas grand-chose, si nous nous avisions de la séparer de ses béquilles, que Thomas Molnar appelle «sa méthode de propagation dans tous les coins de la société» (p. 110) et, surtout, l'élevage quasiment industriel de ces intellectuels si remarquablement définis par

Ma questa analogia non è la sola che possa essere citata. Lo stesso Corbin ne sottintende un’altra dello stesso genere allorché, avvalendosi di una terminologia heideggeriana, ci ricorda che “il passaggio dall’essere (esse) all’ente (ens), i teosofi islamici lo concepiscono come il porre l’essere all’imperativo (KN, Esto). È in forza dell’imperativo Esto che l’ente è investito dell’atto di essere“7.

Ma questa analogia non è la sola che possa essere citata. Lo stesso Corbin ne sottintende un’altra dello stesso genere allorché, avvalendosi di una terminologia heideggeriana, ci ricorda che “il passaggio dall’essere (esse) all’ente (ens), i teosofi islamici lo concepiscono come il porre l’essere all’imperativo (KN, Esto). È in forza dell’imperativo Esto che l’ente è investito dell’atto di essere“7. Nel 1964 avvenne l’incontro di Heidegger col monaco buddhista Bikkhu Maha Mani, docente di filosofia all’Università di Bangkok, che era venuto in Europa per conto della Radio tailandese. “Convinto sostenitore di un uso misurato della tecnologia e dei mass media come strumenti educativi, in Germania aveva voluto incontrare Heidegger proprio per confrontarsi sul problema della tecnica”22. Nel colloquio privato che ebbe luogo fra i due il giorno prima che venisse registrato un loro dialogo sul ruolo della religione, destinato ad essere trasmesso da un’emittente televisiva di Baden-Baden, Heidegger parlò di “abbandono” e di “apertura al mistero” e domandò al suo ospite che significato avesse, per l’Orientale, la meditazione. “Il monaco risponde del tutto semplicemente: ‘Raccogliersi’. E spiega: quanto più l’uomo, senza sforzo di volontà, si raccoglie, tanto più dis-fa [ent-werde] se stesso. L”io’ si estingue. Alla fine, vi è solo il niente. Il niente, tuttavia, non è ‘nulla’, ma proprio tutt’altro: la pienezza [die Fülle]. Nessuno può nominarlo. Ma è, niente e tutto, la piena realizzazione [Erfüllung]. Heidegger ha compreso e dice: ‘Questo è ciò che io, per tutta la mia vita, ho sempre detto’. Ancora una volta il monaco ripete: ‘Venga nella nostra terra. Noi La comprendiamo’”23.

Nel 1964 avvenne l’incontro di Heidegger col monaco buddhista Bikkhu Maha Mani, docente di filosofia all’Università di Bangkok, che era venuto in Europa per conto della Radio tailandese. “Convinto sostenitore di un uso misurato della tecnologia e dei mass media come strumenti educativi, in Germania aveva voluto incontrare Heidegger proprio per confrontarsi sul problema della tecnica”22. Nel colloquio privato che ebbe luogo fra i due il giorno prima che venisse registrato un loro dialogo sul ruolo della religione, destinato ad essere trasmesso da un’emittente televisiva di Baden-Baden, Heidegger parlò di “abbandono” e di “apertura al mistero” e domandò al suo ospite che significato avesse, per l’Orientale, la meditazione. “Il monaco risponde del tutto semplicemente: ‘Raccogliersi’. E spiega: quanto più l’uomo, senza sforzo di volontà, si raccoglie, tanto più dis-fa [ent-werde] se stesso. L”io’ si estingue. Alla fine, vi è solo il niente. Il niente, tuttavia, non è ‘nulla’, ma proprio tutt’altro: la pienezza [die Fülle]. Nessuno può nominarlo. Ma è, niente e tutto, la piena realizzazione [Erfüllung]. Heidegger ha compreso e dice: ‘Questo è ciò che io, per tutta la mia vita, ho sempre detto’. Ancora una volta il monaco ripete: ‘Venga nella nostra terra. Noi La comprendiamo’”23.

Prenons un exemple allemand dans les années vingt et trente. Il y avait un programme du NSDAP. Il y avait une utopie nationale-socialiste, admirablement étudiée par Frédéric Rouvillois (5). Idem pour le marxisme léniniste. Il y avait le programme de Lénine et l’utopie d’une société où chacun s’épanouirait totalement et librement. Robert Redeker rappelle à ce sujet le lien entre marxisme et millénarisme, relevé avant lui par Ernst Bloch. Avec l’utopie c’en est fini de l’histoire et de l’avenir. L’utopie en termine avec l’avenir. Elle ex-termine l’avenir, dit, dans une formule très heureuse, Robert Redeker. Elle fait sortir l’avenir du jeu. Que voulait l’utopie nationale-socialiste ? En finir avec toute faillibilité de l’homme allemand. L’utopie, note encore Redeker, est une anti-chronie. Elle suppose l’arrêt du temps. Elle n’est, au contraire, pas sans lieu. Elle suppose au contraire un lieu définitivement limité. Elle suppose un lieu sans temps. Un pays sans histoire. Kant juge nécessaire l’idée d’une société idéale tout comme Rousseau juge nécessaire l’hypothèse de l’état originel de nature. L’utopie est moins un progressisme qu’un millénarisme qui met fin à tous les progressismes.

Prenons un exemple allemand dans les années vingt et trente. Il y avait un programme du NSDAP. Il y avait une utopie nationale-socialiste, admirablement étudiée par Frédéric Rouvillois (5). Idem pour le marxisme léniniste. Il y avait le programme de Lénine et l’utopie d’une société où chacun s’épanouirait totalement et librement. Robert Redeker rappelle à ce sujet le lien entre marxisme et millénarisme, relevé avant lui par Ernst Bloch. Avec l’utopie c’en est fini de l’histoire et de l’avenir. L’utopie en termine avec l’avenir. Elle ex-termine l’avenir, dit, dans une formule très heureuse, Robert Redeker. Elle fait sortir l’avenir du jeu. Que voulait l’utopie nationale-socialiste ? En finir avec toute faillibilité de l’homme allemand. L’utopie, note encore Redeker, est une anti-chronie. Elle suppose l’arrêt du temps. Elle n’est, au contraire, pas sans lieu. Elle suppose au contraire un lieu définitivement limité. Elle suppose un lieu sans temps. Un pays sans histoire. Kant juge nécessaire l’idée d’une société idéale tout comme Rousseau juge nécessaire l’hypothèse de l’état originel de nature. L’utopie est moins un progressisme qu’un millénarisme qui met fin à tous les progressismes.

Fourth, there is a common dislike of war and, more especially, of war-society, the kind of society this country knew in 1917 and 1918 under Woodrow Wilson and again under FDR in World War II. Libertarians may protest this, and with some ground. For, the complete libertarian is certainly more likely to resist in overt fashion than is the conservative–for whom respect for nation and for patriotism is likely to be decisive even when it is a war he opposes. Even so, I think there is enough common ground, at least with respect to principle, to put conservatives and libertarians together. And let us remember that beginning with the Spanish-American War, which the conservative McKinley opposed strongly, and coming down through each of the wars this century in which the United States became involved, the principal opposition to American entry came from those elements of the economy and social order which were generally identifiable as conservative-whether “middle western isolationist,” traditional Republican, central European ethnic, small business, or however we wish to designate such opposition. I am certainly not unmindful of the libertarian opposition to war that could come from a Max Eastman and a Eugene Debs and from generally libertarian conscientious objectors in considerable number in both world wars, but the solid and really formidable opposition against American entry came from those closely linked to business, church, local community, family, and traditional morality. (Tocqueville correctly identified this class in America as reluctant to engage in any foreign war because of its predictable impact upon business and commerce chiefly, but other, social and moral activities as well.) This was the element in American life, not the miniscule libertarian element, that both Woodrow Wilson and FDR had to woo, persuade, propagandize, convert and, in some instances, virtually terrorize, in order to pave the way for eventual entry by U.S. military forces in Europe and Asia.

Fourth, there is a common dislike of war and, more especially, of war-society, the kind of society this country knew in 1917 and 1918 under Woodrow Wilson and again under FDR in World War II. Libertarians may protest this, and with some ground. For, the complete libertarian is certainly more likely to resist in overt fashion than is the conservative–for whom respect for nation and for patriotism is likely to be decisive even when it is a war he opposes. Even so, I think there is enough common ground, at least with respect to principle, to put conservatives and libertarians together. And let us remember that beginning with the Spanish-American War, which the conservative McKinley opposed strongly, and coming down through each of the wars this century in which the United States became involved, the principal opposition to American entry came from those elements of the economy and social order which were generally identifiable as conservative-whether “middle western isolationist,” traditional Republican, central European ethnic, small business, or however we wish to designate such opposition. I am certainly not unmindful of the libertarian opposition to war that could come from a Max Eastman and a Eugene Debs and from generally libertarian conscientious objectors in considerable number in both world wars, but the solid and really formidable opposition against American entry came from those closely linked to business, church, local community, family, and traditional morality. (Tocqueville correctly identified this class in America as reluctant to engage in any foreign war because of its predictable impact upon business and commerce chiefly, but other, social and moral activities as well.) This was the element in American life, not the miniscule libertarian element, that both Woodrow Wilson and FDR had to woo, persuade, propagandize, convert and, in some instances, virtually terrorize, in order to pave the way for eventual entry by U.S. military forces in Europe and Asia. To argue, as some libertarians have, that a solid, strong body of authority in society is incompatible with individual creativity is to ignore or misread cultural history. Think of the great cultural efflorescences of the 5th century B.C. in Athens, of 1st century, Augustan Rome, of the 13th century in Europe, of the Age of Louis XIV, and Elizabethan England. One and all these were ages of social and moral order, powerfully supported by moral codes and political statutes. But the Aeschyluses, Senecas, Roger Bacons, Molieres, and Shakespeares flourished nonetheless. Far from feeling oppressed by the hierarchical authority all around him, Shakespeare–about whose copious individuality there surely cannot be the slightest question–is the author of the memorable passage that begins with “Take but degree away, untune that string, and hark! what discord follows; each thing meets in mere oppugnancy.” As A. L. Rowse has emphasized and documented in detail, the social structure of Shakespeare’s England was not only solid, its authority ever evident, but nothing threw such fear into the people as the thought that authority–especially that designed to repulse foreign enemies and to ferret out traitors–might be made too loose and tenuous. Of course such authority could become too insistent at times, and ingenious ways were found by the dramatists and essayists to outwit the government and its censors. After all, it was strong social and moral authority the creative minds were living under–not the oppressive, political-bureaucratic, limitless invasive, totalitarian governments of the twentieth century.

To argue, as some libertarians have, that a solid, strong body of authority in society is incompatible with individual creativity is to ignore or misread cultural history. Think of the great cultural efflorescences of the 5th century B.C. in Athens, of 1st century, Augustan Rome, of the 13th century in Europe, of the Age of Louis XIV, and Elizabethan England. One and all these were ages of social and moral order, powerfully supported by moral codes and political statutes. But the Aeschyluses, Senecas, Roger Bacons, Molieres, and Shakespeares flourished nonetheless. Far from feeling oppressed by the hierarchical authority all around him, Shakespeare–about whose copious individuality there surely cannot be the slightest question–is the author of the memorable passage that begins with “Take but degree away, untune that string, and hark! what discord follows; each thing meets in mere oppugnancy.” As A. L. Rowse has emphasized and documented in detail, the social structure of Shakespeare’s England was not only solid, its authority ever evident, but nothing threw such fear into the people as the thought that authority–especially that designed to repulse foreign enemies and to ferret out traitors–might be made too loose and tenuous. Of course such authority could become too insistent at times, and ingenious ways were found by the dramatists and essayists to outwit the government and its censors. After all, it was strong social and moral authority the creative minds were living under–not the oppressive, political-bureaucratic, limitless invasive, totalitarian governments of the twentieth century. Libertarians, whom I herewith stipulate to be as patriotic and loyal American as any conservatives, do not, in my judgment, see the national and world picture as I have just drawn in. For them the essential picture is not that of a weakened, softened, and endangered nation in a world of Soviet Unions and Chinas and their satellites, but, rather, an American nation swollen from the juices of nationalism, interventionism and militarism that really has little to fear from abroad. Conservatives remain by and large devoted to the smaller patriotisms of family, church, locality, job and voluntary association, but they tend to see these as perishable, as destined to destruction, unless the nation in which they exist can recover a degree of eminence and international authority it has not had since the 1950’s. To libertarians on the other hand, judging from many of their writings and speeches, it is as though the steps necessary to recovery of this eminence and international authority are more dangerous to Americans and their liberties than any aggressive, imperialist totalitarianisms in the world.

Libertarians, whom I herewith stipulate to be as patriotic and loyal American as any conservatives, do not, in my judgment, see the national and world picture as I have just drawn in. For them the essential picture is not that of a weakened, softened, and endangered nation in a world of Soviet Unions and Chinas and their satellites, but, rather, an American nation swollen from the juices of nationalism, interventionism and militarism that really has little to fear from abroad. Conservatives remain by and large devoted to the smaller patriotisms of family, church, locality, job and voluntary association, but they tend to see these as perishable, as destined to destruction, unless the nation in which they exist can recover a degree of eminence and international authority it has not had since the 1950’s. To libertarians on the other hand, judging from many of their writings and speeches, it is as though the steps necessary to recovery of this eminence and international authority are more dangerous to Americans and their liberties than any aggressive, imperialist totalitarianisms in the world.

Non. En tout cas, ce n’est pas ma guerre. Si je devais mener une guerre, ce ne serait pas celle-là. Tout ce qui se passe en ce moment relève d’une guerre économique dont on ne parle pas — même si elle fait énormément de dégâts et détruit des villes entières, des sociétés entières. Ce qui se passe en Syrie et ses conséquences en France en sont le résultat.

Non. En tout cas, ce n’est pas ma guerre. Si je devais mener une guerre, ce ne serait pas celle-là. Tout ce qui se passe en ce moment relève d’une guerre économique dont on ne parle pas — même si elle fait énormément de dégâts et détruit des villes entières, des sociétés entières. Ce qui se passe en Syrie et ses conséquences en France en sont le résultat.

Arnold Toynbee, cet historien des civilisations, d'origine anglo-saxonne, publie en 1949-51 (versions anglaise et française) un ouvrage (La civilisation à l'épreuve) rassemblant conférences et essais, tout cela écrit ou récrit avec l'actualisation qui convient à l'époque de l'immédiat après-guerre (période 1945-47). L'intérêt de l'ouvrage est de cerner l'appréciation contemporaine de Toynbee de la position et du développement de la civilisation occidentale. A partir de là, nous élargirons notre appréciation et en viendrons à notre hypothèse.

Arnold Toynbee, cet historien des civilisations, d'origine anglo-saxonne, publie en 1949-51 (versions anglaise et française) un ouvrage (La civilisation à l'épreuve) rassemblant conférences et essais, tout cela écrit ou récrit avec l'actualisation qui convient à l'époque de l'immédiat après-guerre (période 1945-47). L'intérêt de l'ouvrage est de cerner l'appréciation contemporaine de Toynbee de la position et du développement de la civilisation occidentale. A partir de là, nous élargirons notre appréciation et en viendrons à notre hypothèse.