The Enigma of American Fascism in the 1930s

by Michael Kleen

Ex: http://www.alternativeright.com/

In the third decade of the Twentieth Century, as the Great Depression dragged on and the unemployment rate climbed above 20 percent, the United States faced a social and political crisis. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was swept to power in the election of 1932, forcing a political realignment that would put the Democratic Party in the majority for decades. In 1933, President Roosevelt proposed a “New Deal” that he claimed would cure the nation of its economic woes. His plan had many detractors, however, and at the fringes of mainstream politics, disaffected Americans increasingly looked elsewhere for inspiration.

Catholic priest and radio-personality Charles Coughlin’s Christian Front, the German American Bund, the Black Legion, and a variety of nationalist, anti-Semitic, and/or isolationist groups opposed to President Roosevelt, “Moneyed Interests,” and Marxism attracted over a million members and supporters during that decade. Collectively, these groups have long been considered to be a particularly American expression of the same type of fascism that swept Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. The application of the term “fascism” to such a wide variety of individuals and organizations has proved troublesome, however, and the historiography on the subject is conflicted. Did European-style fascism appeal to Americans? Could an “American fascism” have kept the United States out of World War 2?

In order to answer those questions, we must first determine what American fascism was and was not, and then we have to understand why these groups and individuals failed to form any kind of broad coalition against Roosevelt, the New Deal, or liberal democracy itself.

Depending on the historian, American fascism began either as a far-ranging, populist-inspired movement and later degenerated into a number of fringe groups and fanatics, or it began as an isolated phenomenon that lost credibility during the Second World War and simply disappeared. Its adherents either consisted of a wide spectrum of Americans, or of a few thousand recently naturalized immigrants and two or three intellectuals.

“In the United States there were all kinds of fascist or parafascist organizations,” Walter Laqueur asserted in Fascism: Past, Present, Future (1996), “but they never achieved a political breakthrough.”[i] A decade earlier, historian Peter H. Amann took an opposite track. “It seems clear that there were far fewer authentically fascist movements in Depression America than was thought at the time,” he argued.[ii] Conversely, Victor C. Ferkiss, writing in the 1950s, contended that American fascism “was a basically indigenous growth,” and that a broad fascist movement “arose logically from the Populist creed.”[iii]

According to Ferkiss, American fascism was defined as a movement that appealed to farmers and small merchants who felt “crushed between big business . . . and an industrial working class,” espoused nationalism in the form of isolationism, believed that authority came from popular will and not from “liberal democratic institutions” that had been corrupted by moneyed interests, and possessed “an interpretation of history in which the causal factor is the machinations of international financiers.”[iv] According to Peter Amann, all fascism (even the American type) was characterized by an opposition to Marxism and representative government, advocacy of a “revolutionary, authoritarian, nationalist state,” the presence of a charismatic leader and a militarized mass movement, and commonly (although not universally) racist and anti-Semitic views.[v]

These two divergent portrayals, one inclusive and one exclusive, mark the ends of the spectrum in regards to defining fascism in the United States during the 1930s. The former portrays fascism as a legitimate threat to the status quo, and the latter nearly calls its existence into question because so few groups actually fit this model.

American fascism’s cultural roots raise questions as well. Where did the members of these organizations come from? Did American culture encourage or condemn their growth? The data shows a complex picture. American fascism may have been encouraged by some aspects of American culture, but was vigorously condemned by others. The diversity of American interests made a unified fascism that posed a genuine threat to the social order nearly impossible. For instance, while the main constituency of Father Charles Coughlin’s movement was Irish Catholic,[vi] and the members of the German-American Bund mostly recent immigrants,[vii] the Black Legion of the Midwest was fiercely nativist and only accepted Protestants into its ranks.[viii]

What was it about American history and culture doomed openly fascist or fascoid movements? All historians, in their answers, point to our differing conceptions of individual liberty, suspicion of authority, and the commitment to republican government. “No country with a deeply rooted liberal or democratic tradition went fascist,” Peter Amann argued.[ix] For American intellectuals, Victor Ferkiss wrote, “fascism was by definition un-American.”[x] Even the openly racialist and white supremacist South overwhelmingly rejected any comparison to Nazi Germany, and denied it’s Ku Klux Klan had anything to do with fascism.[xi] It seemed that even while incorporating fascist elements, very few Americans openly advocated fascism according to the European model.

Victor C. Ferkiss was far more liberal in his assessment of American fascism than later historians. In his essays “Ezra Pound and American Fascism” (1955) and “Populist Influences on American Fascism” (1957), he attempted to link American fascist groups of the 1930s to the Populist movement of the 1890s, and he broadened the definition of fascism to include prominent aspects of Populism in the United States.

Ezra Pound, American expatriate, poet, and supporter of Benito Mussolini, was the lynchpin of Ferkiss’ argument for an inclusive definition of American fascism. Pound’s ideas, in the widest sense, mirrored those of others in the United States who were known as fascists by their detractors. Ferkiss justified his application of the term by arguing that those individuals and groups “espouse sets of beliefs which have more in common with one another and with European fascism than they do with any other broad area of political thought.”[xii] He listed Huey Long, Gerald L. K. Smith, Father Charles E. Coughlin, and Lawrence Dennis as among those individuals, regardless of how few commonalities their ideas they may have actually shared with European fascist thought.

With this list in hand, Ferkiss held Populism directly responsible for these individual’s fascist tendencies. “American fascism had its roots in American populism,” he declared. “These populist beliefs and attitudes form the core of Pound’s philosophy, just as they provide the basis of American fascism generally.”[xiii] His definition of American fascism followed from that broad interpretation of the commonalities of American fascist thought, even though he acknowledged some fundamental differences. Ezra Pound’s “main divergence from [Lawrence] Dennis is the emphasis which, along with Father Coughlin and Huey Long, he places on the role of finance capitalism as a direct cause of war,” he explained. “For Pound, democracy is a sham.”[xiv]

Ferkiss argued that American fascists viewed the American Revolution as a revolt against the international banking system of England, and that “Mussolini’s objectives are those of Thomas Jefferson,” in his effort to free his country from the power of banks and usury.[xv] That focus on the fascist powers of Europe as defenders of money reform lent to their American supporter’s isolationism, but Ferkiss failed to take into account that approval or agreement does not directly translate into political imitation.

As for the constituency of American fascism, Ferkis argued that “the America First Committee provided the culture in which the seeds of American fascism were to grow.” The AFC was predominantly made up of Midwesterners and a few prominent businessmen, but also had chapters in large Eastern and Western cities. While the AFC was not overtly fascist, “a considerable portion of its chapters were dominated by fascists or their friends,” Ferkiss explained.[xvi] Ezra Pound was also a Midwesterner, having been born in Idaho. He later took a teaching job in Indiana, but he was let go for being “too European” and “unconventional.”[xvii] He emigrated to Europe shortly thereafter.

Written at the same time as Victor Ferkiss’ essays, Joachim Remak’s article “'Friends of the New Germany': The Bund and German-American Relations” (1957) chronicled the nearly universal American reaction against one of the few American fascist groups to consciously model itself after and receive direct inspiration from a European fascist regime: the German-American Bund. Even though the German government forbid its citizens from becoming members of the Bund, and requested that the Bund cease using National Socialist emblems in 1938, most Americans still believed the organization was a foreign entity. “The Americans on its rolls were all of them recent immigrants” from Nazi Germany, Remak explained. “German-Americans had no use for the Bund… the president of the highly conservative Steuben Society called on the [German] embassy to say that his group felt compelled to issue a public repudiation of the Bund.”[xviii]

Remak argued that the German-American Bund, rather than appealing to some broad pro-fascist sympathy in the United States, only harmed relations with National Socialist Germany by demonstrating to Americans the nature of European fascism. “Naziism, with its brutality and its suppression of basic liberties and decencies, could hold no greater appeal for the German-Americans than for the rest of the nation,” he argued.[xix] The rejection of an explicitly fascist organization by those Americans who Victor Ferkiss believed made up the core of ‘American fascism’ is instructive.

Along the same lines, Leland V. Bell, in his book, In Hitler's Shadow: the Anatomy of American Nazism (1973), argued that the real supporters of fascism in the United States were few and far between. In the 1930s, the Nazi party’s pleas for money from American contributors like Henry Ford and the Ku Klux Klan fell on deaf ears. Teutonia, one of the first pro-Nazi groups in the United States, numbered less than one hundred members in 1932, and the typical members of those groups were “young, rootless German immigrants,” and “arrogant, resolute, fanatics.”[xx] When Heinz Spanknoebel formed the Friends of the New Germany in July 1933, “a storm of public protest” greeted them. Four months later, Spanknoebel, like Ezra Pound had earlier, fled the United States.[xxi] The Friends of the New Germany failed to attract significant support from German Americans, who by that time “were accepted, respected citizens and easily assimilated into American life,” Bell explained.[xxii]

In 1936, Fritz Kuhn, a naturalized American citizen who had served in the German army during the First World War, became head of the organization. He renamed it the German-American Bund to attract more American nationals. Most of the constituency of the Bund was made up of recent German immigrants, however, despite Adolf Hitler having banned German citizens from becoming members of the organization. In contrast to Victor Ferkiss’ claim that supporters of American fascism were predominantly rural, the Bund was an urban lower-middle-class movement.[xxiii]

It is clear from Joachim Remak and Leland Bell’s analysis of the German-American Bund that Americans were generally suspicious of overtly fascist groups along the European model. Even the ethnic Germans who had established themselves in the Midwest as farmers and craftsmen, who generally supported isolationism before both World Wars, were not sympathetic to the anti-Democratic, outspokenly pro-Hitler Bundists.

One of the intellectual proponents of American fascism mentioned by Victor Ferkiss was Seward Collins, editor and publisher of the journal American Review. In his article “Seward Collins and the American Review: Experiment in Pro-Fascism, 1933-37” (1960), historian Albert E. Stone argued that Collins’ attempts to “define fascism and apply it to American life” not only produced nothing but controversy, but also undermined his project by alienating his supporters.

Seward Collins’ definition of fascism was unique compared to those covered thus far. According to Stone, Collins amalgamated four schools of thought—two English and two American—which he trumpeted in the American Review: Distributism, Neo-Scholasticism, Humanism, and Southern Agrarianism. Stone explained, “Where these four bodies of thought converged, Collins believed, could be found a definition of fascism which should be offered to thoughtful Americans.”[xxiv] For Seward Collins, fascism meant an end to parliamentary government, but not necessarily an end to democracy. Instead of a president, the head of state would be a monarch― “A strong man at the head of government,”[xxv] which would be coupled by nationalism undivided by rival oppositions.

Collins asserted that the essence of fascism was “the revival of monarchy, property, the guilds, the security of the family and the peasantry, and the ancient ways of European life.”[xxvi] However, that conception of fascism seemed to be a Collins’ own invention and was certainly far afield from the views of Ezra Pound or the German-American Bund. Also, Collins’ espoused anti-Semitism “bore virtually no trace of racial superiority.” He wished to exclude Jews from his fascist state only because they represented social and political rivals, as well as potential dissenters. There was no place in his mind for ideas of Nordic racial superiority, which he called “nonsense.”[xxvii] That would also distinguish him from organizations like the Black Legion and the German-American Bund.

According to Albert Stone, Collins’ views on monarchy and nationalism ultimately alienated one of his important constituencies in the United States, Southern Agrarians. “Southern Agrarians opposed in theory a strong central government,” Stone explained. They were also suspicious of nationalism, deeply isolationist, and “welcomed regional, social and racial differences as healthy manifestations of time, place and tradition.”[xxviii] During a January 1936 interview with the pro-communist magazine FIGHT, Seward Collins colorfully explicated his desire for a monarchy and a return to a medieval society, disparaged liberal education, and voiced admiration for Hitler and Mussolini.

Almost immediately after the interview was published, the American Review’s Southern Agrarian writers left in protest. The Distributists also distanced themselves. Herbert Agar, a prominent member of that bloc, stated, “I would die in order to diminish the chances of fascism in America.”[xxix] The American Review ceased publication in 1937. In the end, it seemed that the majority of Seward Collins’ contributors wanted nothing to do with his views.

In “Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid” (1983) and “A 'Dog in the Nighttime' Problem: American Fascism in the 1930s” (1986), Peter H. Amann argued for a narrow definition of fascism that held closely to the European model and therefore excluded most American groups. Instead, he employed the terms “protofascist” or “fascoid” to describe American organizations that embraced certain aspects or appearances of fascism, but failed to develop into mature fascist political movements.

One such group was the Black Legion, a secret offshoot of the Midwestern Ku Klux Klan. An Ohioan named Dr. William Jacob Shepard formed the Legion during the late 1920s, but never intended the group to take on a life of its own. He was a Northerner who idolized the old South, and he “spouted, and apparently believed, the most rotund platitudes about southern chivalry.”[xxx] He was also a baptized Catholic who hated Catholics, and a doctor who did not shy away from violence.

His Black Legion donned black robes instead of white and held secret initiation rituals. “They were asked to endorse the standard nativist anti-immigrant, anti-Negro, and anti-Catholic positions,” Amann explained, and “pledge support to lynch law.”[xxxi] Initiates were often coaxed or deceived into coming to meetings, and then threatened with death if they did not join.[xxxii] The membership of the Legion was spread across Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and parts of Illinois, and the majority of members were urban and working class.[xxxiii]

The Black Legion became more violent and more revolutionary as time went on, bringing them closer to the European fascist model. Bert Effinger, their defacto leader during the 1930s, even planned “to kill one million Jews by planting in every American synagogue during Yon Kippur time-clock devices that would simultaneously release mustard gas.”[xxxiv]

Amann argued that the secretive nature of the group prevented them from becoming an effective organization. They were powerful in some ways, but their secrecy made it impossible for them to appeal to a mass audience. No one outside of their organization knew they existed—not even their enemies—so fear and intimidation became a useless tactic. They attempted to create front organizations to infiltrate established political parties but, ultimately, “by pretending to be mere Republicans, Legionnaires ended up acting as mere Republicans.”[xxxv]

Despite their failure, the Black Legion did share many characteristics with European fascist groups. According to Amann, they shared many of the same hatreds, revolutionary goals, and dictatorial tendencies. However, their initiation ceremonies, because of their ultra secrecy, never held the same weight as the mass rallies and rituals of European fascists. Also, the Legion’s nativism was patriotic in a crucial way: the American system may have been corrupt, but there was no alternative to the Constitution or the Republic. Their goal was only to purify the current system, not overthrow it. The history of the Black Legion ultimately shows, Amann argued, that “vigilante nativism and revolutionary-fascism were fundamentally incompatible.”[xxxvi] Additionally, he concluded, “by no stretch of anyone’s imagination can the Black Legion under Dr. Shepard be described as fascist. His Night Riders were to fascism what the Shriners are to Islam.”[xxxvii]

Similarly, the ultra-patriotic societies of the 1930s that evolved into the America First Committee, which Victor Ferkiss believed provided the cultural basis for American fascism, lacked the same crucial ingredients as their alleged European counterparts. “Whatever emphasis prevailed,” Amann explained, “there was never any thought of attacking the American constitutional system, the incumbent politicians, or the two major parties. Nor was there any attempt at mass mobilization.” The Ku Klux Klan, for example, never formed a political party or sought to change the political or economic system of the United States. Therefore, Amann concluded, “the overlap between American nativism and the European type of fascism is… more apparent than real.”[xxxviii]

The nature of these diverse groups also prevented them from working together to present a united front. “The nativist inheritance included… a divisive traditional anti-Catholicism that led the Black Legion to plant explosives in Father Charles Coughlin’s shrine rather than to seek him out as a potential ally,” Peter Amann pointed out.[xxxix] Additionally, genuinely fascist groups like the German-American Bund, with their “aping” of European fascist models, had their patriotic credentials routinely called into question. “It became obvious that in the United States such a nationalism could not be imported from abroad without looking both foolish and unpatriotic,” Amann argued.[xl] A genuine American fascism appealed to very few Americans in the 1930s, and every protofascist organization fell apart the more violent and overtly fascist in appearance and action it became.

In his book Hoods and Shirts: the Extreme Right in Pennsylvania (1997), Philip Jenkins tackled the problem of American fascism from a different angle. He argued that fascism was “polychromatic rather than monotone,” and embraced a spectrum of beliefs across Europe that was also reflected in the United States.[xli] If historians were not hesitant to label such diverse groups as Na Léinte Gorma in Ireland and the Croatian Ustashi (who were lead by church figures and clergymen) as fascist, he reasoned, then they should not be hesitant to label an organization like Father Coughlin’s Christian Front in the same manner.

However, the issue is complicated by the fact that fascist groups in the United States hesitated to call themselves as such. “The organizations most enthusiastic about European Nazism or fascism rarely included these provocative terms in their titles,” he explained. Most often, “Christian” and “Nationalist” were substituted instead because their appeal to American patriotism precluded foreign ideologies. In his own words, “a denial of fascism was phrased as part of a general rejection of any foreign theories.”[xlii]

Father Coughlin’s Christian Front was one of the primary organizations profiled in Hoods and Shirts. According to Jenkins, the Christian Front was founded on “traditions of Irish nationalism” and “anti-British feeling.”[xliii] Although Coughlin himself broadcast his radio messages from Michigan, the Front’s membership was heavily Irish and centered in large cities such as New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Cleveland, Boston and Philadelphia. Jenkins described Father Coughlin as akin to Spanish Nationalist leader Francisco Franco, to whom Coughlin had given moral support during the Spanish Civil War.

Coughlin’s movement linked Jews with communism and saw the Spanish Civil War as a war between good and evil. “Sympathy for Jews was indistinguishable from providing aid and comfort for Communist subversion,” Jenkins explained. The Christian Front allied itself with an assortment of groups, including the German-American Bund, in support of attacks on Jewish synagogues and businesses.[xliv] These activities, along with some outspoken statements in favor of Adolf Hitler, led to the arrest of dozens of movement members. Not all Irish Catholics supported those activities. After one particularly violent incident, an Irish Catholic magistrate “accused the Coughlinites of attempting to spread ‘European’ conditions in Philadelphia.”[xlv] Other Catholics regularly denounced Coughlin in newspapers and journals.[xlvi]

The Christian Front did welcome members from other backgrounds, as evidenced by its willingness to work together with Bund members as well as Italian-Americans. “In New York City over half of all Catholic clergy serving predominantly Italian parishes demonstrated sympathy for the Fascist cause and thus cooperated with the emerging Front,” Jenkins explained.[xlvii] African-American anti-Semites, especially those involved with Black Muslim sects, also attended gatherings and supported Front anti-Jewish activities. Some African Americans in large cities saw Jews as “exploitative landlords and grasping merchants,”[xlviii] which echoed the crusade against “moneyed interests” that was so central to Victor Ferkiss’ definition of American fascism.

As the Second World War broke out in Europe, the Christian Front faced increasing public opposition, as well as persecution by the FBI. Jenkins concluded that both its supporters and its enemies exaggerated the impact of the movement, but it represented one of the only fascoid groups in the United States during the 1930s to have been genuinely domestic in origin. “Of all the activist groups,” he argued, “this had perhaps the greatest potential to become a genuine mass movement around which others could coalesce.”[xlix] Even still, like every other American group on the far right, the political movement it sought to inspire fizzled out when the United States entered the war.

The historical record is very clear. The range of individuals and organizations surveyed by Victor Ferkiss, Peter Amann, and Philip Jenkins all show a similar arch: a steady rise in popularity followed by radicalization, which then ran up against resistance when the group’s activities were exposed. The end result was the rapid dissolution of the organization or the exile of the individual. By 1941, no one who openly came out as being supportive of fascism survived very long in the public eye.

Although a certain cultural undercurrent was needed in order to support the existence of these groups, that cultural undercurrent was undermined by the American democratic tradition they sought to oppose. It seems that, at least in the atmosphere of 1930s America, one could not be both a fascist in any meaningful sense of the word and also be supported by the majority of Americans who saw fascism as a threat to their liberal democratic institutions. The experiences of groups such as the German-American Bund, the Black Legion, Father Coughlin’s Christian Front, and individuals like Seward Collins and Ezra Pound seem to confirm that fascism was by definition a fundamentally “European” phenomenon.

[i] Walter Laqueur, Fascism: Past, Present, Future (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 17.

[ii] Peter H. Amann, “A 'Dog in the Nighttime' Problem: American Fascism in the 1930s,” The History Teacher 19 (August 1986): 574.

[iii] Victor C. Ferkiss, “Populist Influences on American Fascism,” The Western Political Quarterly 10 (June 1957): 350, 352.

[iv] Ibid., 350-351.

[v] Amann, 560.

[vi] Ibid., 574.

[vii] Leland V. Bell, In Hitler's Shadow: the Anatomy of American Nazism (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1973), 21.

[viii] Peter H. Amann, “Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 25 (July 1983): 496.

[ix] Amann, “A ‘Dog in the Nighttime Problem”: 559.

[x] Ferkiss, “Populist Influences on American Fascism”: 350.

[xi] Johnpeter Horst Grill and Robert L. Jenkins, “The Nazis and the American South in the 1930s: A Mirror Image?,” The Journal of Southern History 58 (November 1992): 688.

[xii] Ferkiss, “Ezra Pound and American Fascism”: 173-4.

[xiii] Ibid., 174.

[xiv] Ibid., 186.

[xv] Ibid., 190.

[xvi] Ferkiss, “Populist Influences on American Fascism”: 367-8.

[xvii] Ferkiss, “Ezra Pound and American Fascism”: 175.

[xviii] Joachim Remak, “'Friends of the New Germany': The Bund and German-American Relations,” The Journal of Modern History 29 (March 1957): 40.

[xix] Ibid., 41.

[xx] Leland V. Bell, In Hitler's Shadow: the Anatomy of American Nazism (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1973), 7.

[xxi] Ibid., 13.

[xxii] Ibid., 15-16.

[xxiii] Ibid., 21.

[xxiv] Albert E. Stone, Jr., “Seward Collins and the American Review: Experiment in Pro-Fascism, 1933-37,” American Quarterly 12 (Spring 1960): 6.

[xxv] Ibid., 7.

[xxvi] Ibid., 9.

[xxvii] Ibid., 12.

[xxviii] Ibid., 13.

[xxix] Ibid., 17.

[xxx] Peter H. Amann, “Vigilante Fascism”: 494.

[xxxi] Ibid., 496.

[xxxii] Ibid., 498.

[xxxiii] Ibid., 509.

[xxxiv] Ibid., 512.

[xxxv] Ibid., 515.

[xxxvi] Ibid., 524.

[xxxvii] Ibid., 501.

[xxxviii] Peter H. Amann, “A 'Dog in the Nighttime' Problem”: 562.

[xxxix] Ibid., 567.

[xl] Ibid., 569.

[xli] Philip Jenkins, Hoods and Shirts: the Extreme Right in Pennsylvania, 1925-1950 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 27.

[xlii] Ibid., 25-26.

[xliii] Ibid., 166.

[xliv] Ibid., 173.

[xlv] Ibid., 174.

[xlvi] Ibid., 187-8.

[xlvii] Ibid., 183.

[xlviii] Ibid., 185.

[xlix] Ibid., 191.

Michael Kleen

Michael Kleen is the Editor-in-Chief of Untimely Meditations, publisher of Black Oak Presents, and proprietor of Black Oak Media. He holds a master’s degree in American history and is the author of The Britney Spears Culture, a collection of columns regarding issues in contemporary American politics and culture. His columns have appeared in various publications and websites, including the Rock River Times, Daily Eastern News, World Net Daily, and Strike-the-Root.

“Conservatisme is een ‘elitaire’, men kan ook zeggen ‘esoterische’ aangelegenheid (…). Het misverstand als zou de conservatief een theorielozen, een onfilosofische, ja, zelfs antifilosofische pragmaticus zijn, lijkt onuitroeibaar. Ik heb nochtans met veel kracht en overtuiging aangetoond dat het een misverstand is, toen ik het over die domeinen had, die man als ‘conservatieve mystiek’ zou kunnen omschrijven (…). Een zekere zin voor de onoplosbare complexiteit van de werkelijkheid, de erkenning van het feit dat men over het leven slechts brokstukgewijs rationeel kunnen spreken, de aandacht voor de tegenstelling, voor het tragische en voor het gedeeltelijk demonische dat door de geschiedenis waart, een constitutionele scepsis tegenover de ‘grote oplossingen’”. Woorden van Gerd Klaus Kaltenbrunner, een grote Oostenrijkse mijnheer, die bij menig jonge Europeaan de grondvesten van een degelijke conservatieve ideeënwereld heeft gelegd.

“Conservatisme is een ‘elitaire’, men kan ook zeggen ‘esoterische’ aangelegenheid (…). Het misverstand als zou de conservatief een theorielozen, een onfilosofische, ja, zelfs antifilosofische pragmaticus zijn, lijkt onuitroeibaar. Ik heb nochtans met veel kracht en overtuiging aangetoond dat het een misverstand is, toen ik het over die domeinen had, die man als ‘conservatieve mystiek’ zou kunnen omschrijven (…). Een zekere zin voor de onoplosbare complexiteit van de werkelijkheid, de erkenning van het feit dat men over het leven slechts brokstukgewijs rationeel kunnen spreken, de aandacht voor de tegenstelling, voor het tragische en voor het gedeeltelijk demonische dat door de geschiedenis waart, een constitutionele scepsis tegenover de ‘grote oplossingen’”. Woorden van Gerd Klaus Kaltenbrunner, een grote Oostenrijkse mijnheer, die bij menig jonge Europeaan de grondvesten van een degelijke conservatieve ideeënwereld heeft gelegd.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

BREIZATAO – CORSICA (19/02/2011) L’IFOP a publié en 2008 une étude très intéressante sur les glissements politiques en cours en Corse au sein de la mouvance nationaliste. Constat le plus frappant: la nouvelle génération se tourne résolument vers un nationalisme de droite affirmée.

BREIZATAO – CORSICA (19/02/2011) L’IFOP a publié en 2008 une étude très intéressante sur les glissements politiques en cours en Corse au sein de la mouvance nationaliste. Constat le plus frappant: la nouvelle génération se tourne résolument vers un nationalisme de droite affirmée.

Chiunque abbia a cuore il superamento del presente sistema liberaldemocratico, imperniato sul tradimento dei popoli a vantaggio del potere finanziario mondiale, e chiunque voglia agire nel nome di valori di socialità condivisa, di solidarismo anti-utilitario e di eredità bio-storica, non può seriamente prendere in considerazione l’opzione costituita dalle varie Destre oggi all’opera. Esse sono, senza eccezioni, colonne portanti del liberismo e dello sgretolamento identitario.

Chiunque abbia a cuore il superamento del presente sistema liberaldemocratico, imperniato sul tradimento dei popoli a vantaggio del potere finanziario mondiale, e chiunque voglia agire nel nome di valori di socialità condivisa, di solidarismo anti-utilitario e di eredità bio-storica, non può seriamente prendere in considerazione l’opzione costituita dalle varie Destre oggi all’opera. Esse sono, senza eccezioni, colonne portanti del liberismo e dello sgretolamento identitario.

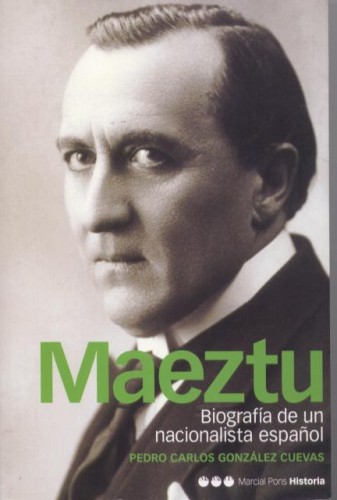

En 1912, Maeztu había empezado a interesarse por las ideas sindicalistas y corporativistas que comenzaban a dominar en algunos círculos intelectuales europeos. No encontró, desde luego, el sindicalismo revolucionario de raíz soreliana un simpatizante en Maeztu, quien rechazó de plano sus actitudes violentas y, sobre todo, un irracionalismo tomado de Bergson; era «antiintelectual y antiinteligente», heredero de la «sofistería moderna»1. Se equivocaban, además, Sorel y sus acólitos en la percepción de la realidad social, al sostener, como el marxismo, la visión dicotómica de las clases sociales; lo que suponía, tanto a nivel teórico como práctico, una enorme simplificación, que prescindía de sectores tan decisivos como el campesinado y toda la clase media -comerciantes, industriales, pequeños rentistas, intelectuales, etc.-. El fundamento real del sindicalismo, por el contrario, era la pluralidad de las clases sociales, que, a través de sus organizaciones sindicales, se disponían a defender sus intereses. «Se funda en que las clases sociales son muchas. Y en esta multiplicidad de intereses de clase es necesario precisar y concretar los de la clase obrera, si ha de evitarse que los trabajadores tomen por propios los intereses de otras clases sociales2.

En 1912, Maeztu había empezado a interesarse por las ideas sindicalistas y corporativistas que comenzaban a dominar en algunos círculos intelectuales europeos. No encontró, desde luego, el sindicalismo revolucionario de raíz soreliana un simpatizante en Maeztu, quien rechazó de plano sus actitudes violentas y, sobre todo, un irracionalismo tomado de Bergson; era «antiintelectual y antiinteligente», heredero de la «sofistería moderna»1. Se equivocaban, además, Sorel y sus acólitos en la percepción de la realidad social, al sostener, como el marxismo, la visión dicotómica de las clases sociales; lo que suponía, tanto a nivel teórico como práctico, una enorme simplificación, que prescindía de sectores tan decisivos como el campesinado y toda la clase media -comerciantes, industriales, pequeños rentistas, intelectuales, etc.-. El fundamento real del sindicalismo, por el contrario, era la pluralidad de las clases sociales, que, a través de sus organizaciones sindicales, se disponían a defender sus intereses. «Se funda en que las clases sociales son muchas. Y en esta multiplicidad de intereses de clase es necesario precisar y concretar los de la clase obrera, si ha de evitarse que los trabajadores tomen por propios los intereses de otras clases sociales2.

Come sappiamo, dalla dissoluzione dell’ordinamento medioevale sorse lo Stato territoriale accentrato e delimitato. In questa nuova concezione della territorialità – caratterizzata dal principio di sovranità – l’idea di Stato superò sia il carattere non esclusivo dell’ordinamento spaziale medioevale, sia la parcellizzazione del principio di autorità (1).

Come sappiamo, dalla dissoluzione dell’ordinamento medioevale sorse lo Stato territoriale accentrato e delimitato. In questa nuova concezione della territorialità – caratterizzata dal principio di sovranità – l’idea di Stato superò sia il carattere non esclusivo dell’ordinamento spaziale medioevale, sia la parcellizzazione del principio di autorità (1).

Bajo la fórmula “Revolución Conservadora” acuñada por Armin Mohler (Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschlan 1918-1932) se engloban una serie de corrientes de pensamiento contemporáneas del nacionalsocialismo, independientes del mismo, pero con evidentes conexiones filosóficas e ideológicas, cuyas figuras más destacadas son Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt y Moeller van den Bruck, entre otros. La “Nueva Derecha” europea ha invertido intelectualmente gran parte de sus esfuerzos en la recuperación del pensamiento de estos autores, junto a otros como Martin Heidegger, Arnold Gehlen y Konrad Lorenz (por citar algunos de ellos), a través de una curiosa fórmula retrospectiva: se vuelve a los orígenes teóricos, dando un salto en el tiempo para evitar el “interregno fascista”, y se comienza de nuevo intentando reconstruir los fundamentos ideológicos del conservadurismo revolucionario sin caer en la “tentación totalitaria” y eludiendo cualquier “desviacionismo nacionalsocialista”.

Bajo la fórmula “Revolución Conservadora” acuñada por Armin Mohler (Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschlan 1918-1932) se engloban una serie de corrientes de pensamiento contemporáneas del nacionalsocialismo, independientes del mismo, pero con evidentes conexiones filosóficas e ideológicas, cuyas figuras más destacadas son Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt y Moeller van den Bruck, entre otros. La “Nueva Derecha” europea ha invertido intelectualmente gran parte de sus esfuerzos en la recuperación del pensamiento de estos autores, junto a otros como Martin Heidegger, Arnold Gehlen y Konrad Lorenz (por citar algunos de ellos), a través de una curiosa fórmula retrospectiva: se vuelve a los orígenes teóricos, dando un salto en el tiempo para evitar el “interregno fascista”, y se comienza de nuevo intentando reconstruir los fundamentos ideológicos del conservadurismo revolucionario sin caer en la “tentación totalitaria” y eludiendo cualquier “desviacionismo nacionalsocialista”.

Sweden’s ruling centre-right coalition won the most votes but fell short of a majority in the general election as the far right entered parliament for the first time.

Sweden’s ruling centre-right coalition won the most votes but fell short of a majority in the general election as the far right entered parliament for the first time.  The concept of right-wing anarchism seems paradoxical, indeed oxymoronic, starting from the assumption that all “right-wing” political viewpoints include a particularly high evaluation of the principle of order. . . . In fact right-wing anarchism occurs only in exceptional circumstances, when the hitherto veiled affinity between anarchism and conservatism may become apparent.

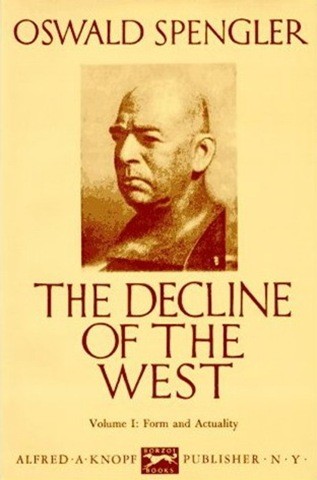

The concept of right-wing anarchism seems paradoxical, indeed oxymoronic, starting from the assumption that all “right-wing” political viewpoints include a particularly high evaluation of the principle of order. . . . In fact right-wing anarchism occurs only in exceptional circumstances, when the hitherto veiled affinity between anarchism and conservatism may become apparent. Conceived before the First World War is Oswald Spengler’s magisterial work, Der Untergang des Abendlandes (Munich, 1918). Read in this country chiefly in the brilliantly faithful translation by Charles Francis Atkinson, The Decline of the West (New York, two volumes, 1926-28), Spengler’s morphology of history was the great intellectual achievement of our century. Whatever our opinion of his methods or conclusions, we cannot deny that he was the Copernicus of historionomy. All subsequent writings on the philosophy of history may fairly be described as criticism of the Decline of the West.

Conceived before the First World War is Oswald Spengler’s magisterial work, Der Untergang des Abendlandes (Munich, 1918). Read in this country chiefly in the brilliantly faithful translation by Charles Francis Atkinson, The Decline of the West (New York, two volumes, 1926-28), Spengler’s morphology of history was the great intellectual achievement of our century. Whatever our opinion of his methods or conclusions, we cannot deny that he was the Copernicus of historionomy. All subsequent writings on the philosophy of history may fairly be described as criticism of the Decline of the West. The exception becomes even more remarkable if we, unlike Spengler, regard as fundamentally important the concept of self-government, which may have been present even in Mycenaean times (see L. R. Palmer, Mycenaeans and Minoans, cited above, p. 97). Democracies and constitutional republics are found only in the Graeco-Roman world and our own; such institutions seem to have been incomprehensible to other cultures.

The exception becomes even more remarkable if we, unlike Spengler, regard as fundamentally important the concept of self-government, which may have been present even in Mycenaean times (see L. R. Palmer, Mycenaeans and Minoans, cited above, p. 97). Democracies and constitutional republics are found only in the Graeco-Roman world and our own; such institutions seem to have been incomprehensible to other cultures.

Dans le monde clos des intellectuels catholiques, Thomas Molnar reste un penseur à part. Philosophe, universitaire, écrivain et journaliste, l’ancien exilé hongrois réfugié aux États-Unis est rentré dans sa patrie dès la chute du communisme. Depuis il enseigne la philosophie religieuse à l’Université de Budapest. Mieux, avec la victoire des jeunes-démocrates de Viktor Orban, le professeur Molnar fut le conseiller culturel du jeune Premier ministre magyar avant de retourner dans l’opposition.

Dans le monde clos des intellectuels catholiques, Thomas Molnar reste un penseur à part. Philosophe, universitaire, écrivain et journaliste, l’ancien exilé hongrois réfugié aux États-Unis est rentré dans sa patrie dès la chute du communisme. Depuis il enseigne la philosophie religieuse à l’Université de Budapest. Mieux, avec la victoire des jeunes-démocrates de Viktor Orban, le professeur Molnar fut le conseiller culturel du jeune Premier ministre magyar avant de retourner dans l’opposition. Thomas Molnar, the esteemed political philosopher and historian, passed away on July 20 at the age of eighty-nine. Dr. Molnar was a friend of ISI from its earliest days. He lectured frequently for the Institute and contributed many articles to the Intercollegiate Review and Modern Age. In 2003 ISI awarded him its Will Herberg Award for Outstanding Faculty Service.

Thomas Molnar, the esteemed political philosopher and historian, passed away on July 20 at the age of eighty-nine. Dr. Molnar was a friend of ISI from its earliest days. He lectured frequently for the Institute and contributed many articles to the Intercollegiate Review and Modern Age. In 2003 ISI awarded him its Will Herberg Award for Outstanding Faculty Service.