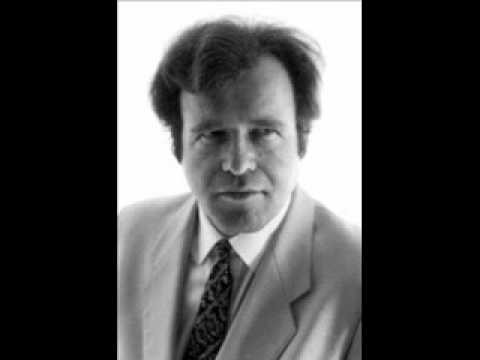

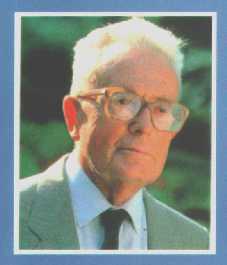

Le 9 octobre 2010, il y a deux ans, disparaissait Maurice Allais à l’âge respectable de 99 ans, qui avait tout annoncé…

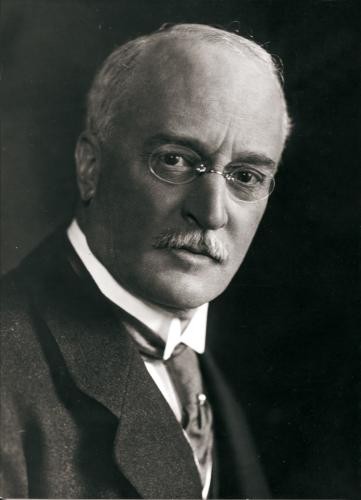

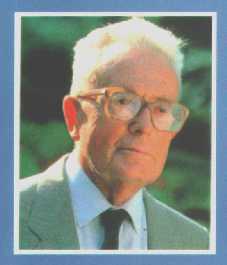

C’était le seul prix Nobel d’économie français. Né le 31 mai 1911, il part aux États-Unis dès sa sortie (major X31) de Polytechnique en 1933 pour étudier in situ la Grande Dépression qui a suivi la Crise de 1929. Ironie de l’histoire, il a ainsi pu réaliser une sorte de “jonction” entre les deux Crises majeures du siècle. Son analyse, percutante et dérangeante, n’a malheureusement pas été entendue faute de relais.

C’était le seul prix Nobel d’économie français. Né le 31 mai 1911, il part aux États-Unis dès sa sortie (major X31) de Polytechnique en 1933 pour étudier in situ la Grande Dépression qui a suivi la Crise de 1929. Ironie de l’histoire, il a ainsi pu réaliser une sorte de “jonction” entre les deux Crises majeures du siècle. Son analyse, percutante et dérangeante, n’a malheureusement pas été entendue faute de relais.

Fervent libéral, économiquement comme politiquement, il s’est férocement élevé contre le néo-conservatisme des années 1980, arguant que le libéralisme ne se confondait pas avec une sortie de “toujours mois d’État, toujours plus d’inégalités” – qui est même finalement la définition de l’anarchisme. On se souviendra de sa dénonciation du “libre-échangiste mondialiste, idéologie aussi funeste qu’erronée” et de la “chienlit mondialiste laissez-fairiste”. Il aimait à se définir comme un “libéral socialiste” – définition que j’aime beaucoup à titre personnel.

Il a passé les dernières années de sa vie à promouvoir une autre Europe, bien loin de ce qu’il appelait “l’organisation de Bruxelles”, estimant que la construction européenne avait pervertie avec l’entrée de la Grande-Bretagne puis avec l’élargissement à l’Europe de l’Est.

RIP

Lettre aux français : “Contre les tabous indiscutés”

Le 5 décembre 2009, le journal Marianne a publié le testament politique de Maurice Allais, qu’il a souhaité rédiger sous forme d’une Lettre aux Français.

Je vous conseille de le lire, il est assez court et clair. Je le complète par divers autres textes surtout pour les personnes intéressées – même si cela alourdit le billet.

Le point de vue que j’exprime est celui d’un théoricien à la fois libéral et socialiste. Les deux notions sont indissociables dans mon esprit, car leur opposition m’apparaît fausse, artificielle. L’idéal socialiste consiste à s’intéresser à l’équité de la redistribution des richesses, tandis que les libéraux véritables se préoccupent de l’efficacité de la production de cette même richesse. Ils constituent à mes yeux deux aspects complémentaires d’une même doctrine. Et c’est précisément à ce titre de libéral que je m’autorise à critiquer les positions répétées des grandes instances internationales en faveur d’un libre-échangisme appliqué aveuglément.

Le fondement de la crise : l’organisation du commerce mondial

La récente réunion du G20 a de nouveau proclamé sa dénonciation du « protectionnisme » , dénonciation absurde à chaque fois qu’elle se voit exprimée sans nuance, comme cela vient d’être le cas. Nous sommes confrontés à ce que j’ai par le passé nommé « des tabous indiscutés dont les effets pervers se sont multipliés et renforcés au cours des années » (1). Car tout libéraliser, on vient de le vérifier, amène les pires désordres. Inversement, parmi les multiples vérités qui ne sont pas abordées se trouve le fondement réel de l’actuelle crise : l’organisation du commerce mondial, qu’il faut réformer profondément, et prioritairement à l’autre grande réforme également indispensable que sera celle du système bancaire.

Les grands dirigeants de la planète montrent une nouvelle fois leur ignorance de l’économie qui les conduit à confondre deux sortes de protectionnismes : il en existe certains de néfastes, tandis que d’autres sont entièrement justifiés. Dans la première catégorie se trouve le protectionnisme entre pays à salaires comparables, qui n’est pas souhaitable en général. Par contre, le protectionnisme entre pays de niveaux de vie très différents est non seulement justifié, mais absolument nécessaire. C’est en particulier le cas à propos de la Chine, avec laquelle il est fou d’avoir supprimé les protections douanières aux frontières. Mais c’est aussi vrai avec des pays plus proches, y compris au sein même de l’Europe. Il suffit au lecteur de s’interroger sur la manière éventuelle de lutter contre des coûts de fabrication cinq ou dix fois moindres – si ce n’est des écarts plus importants encore – pour constater que la concurrence n’est pas viable dans la grande majorité des cas. Particulièrement face à des concurrents indiens ou surtout chinois qui, outre leur très faible prix de main-d’œuvre, sont extrêmement compétents et entreprenants.

Il faut délocaliser Pascal Lamy !

Mon analyse étant que le chômage actuel est dû à cette libéralisation totale du commerce, la voie prise par le G20 m’apparaît par conséquent nuisible. Elle va se révéler un facteur d’aggravation de la situation sociale. À ce titre, elle constitue une sottise majeure, à partir d’un contresens incroyable. Tout comme le fait d’attribuer la crise de 1929 à des causes protectionnistes constitue un contresens historique. Sa véritable origine se trouvait déjà dans le développement inconsidéré du crédit durant les années qui l’ont précédée. Au contraire, les mesures protectionnistes qui ont été prises, mais après l’arrivée de la crise, ont certainement pu contribuer à mieux la contrôler. Comme je l’ai précédemment indiqué, nous faisons face à une ignorance criminelle. Que le directeur général de l’Organisation mondiale du commerce, Pascal Lamy, ait déclaré : « Aujourd’hui, les leaders du G20 ont clairement indiqué ce qu’ils attendent du cycle de Doha : une conclusion en 2010 » et qu’il ait demandé une accélération de ce processus de libéralisation m’apparaît une méprise monumentale, je la qualifierais même de monstrueuse. Les échanges, contrairement à ce que pense Pascal Lamy, ne doivent pas être considérés comme un objectif en soi, ils ne sont qu’un moyen. Cet homme, qui était en poste à Bruxelles auparavant, commissaire européen au Commerce, ne comprend rien, rien, hélas ! Face à de tels entêtements suicidaires, ma proposition est la suivante : il faut de toute urgence délocaliser Pascal Lamy, un des facteurs majeurs de chômage !

Plus concrètement, les règles à dégager sont d’une simplicité folle : du chômage résulte des délocalisations, elles-mêmes dues aux trop grandes différences de salaires… À partir de ce constat, ce qu’il faut entreprendre en devient tellement évident ! Il est indispensable de rétablir une légitime protection. Depuis plus de dix ans, j’ai proposé de recréer des ensembles régionaux plus homogènes, unissant plusieurs pays lorsque ceux-ci présentent de mêmes conditions de revenus, et de mêmes conditions sociales. Chacune de ces « organisations régionales » serait autorisée à se protéger de manière raisonnable contre les écarts de coûts de production assurant des avantages indus a certains pays concurrents, tout en maintenant simultanément en interne, au sein de sa zone, les conditions d’une saine et réelle concurrence entre ses membres associés.

Un protectionnisme raisonné et raisonnable

Ma position et le système que je préconise ne constitueraient pas une atteinte aux pays en développement. Actuellement, les grandes entreprises les utilisent pour leurs bas coûts, mais elles partiraient si les salaires y augmentaient trop. Ces pays ont intérêt à adopter mon principe et à s’unir à leurs voisins dotés de niveaux de vie semblables, pour développer à leur tour ensemble un marché interne suffisamment vaste pour soutenir leur production, mais suffisamment équilibré aussi pour que la concurrence interne ne repose pas uniquement sur le maintien de salaires bas. Cela pourrait concerner par exemple plusieurs pays de l’est de l’Union européenne, qui ont été intégrés sans réflexion ni délais préalables suffisants, mais aussi ceux d’Afrique ou d’Amérique latine.

L’absence d’une telle protection apportera la destruction de toute l’activité de chaque pays ayant des revenus plus élevés, c’est-à-dire de toutes les industries de l’Europe de l’Ouest et celles des pays développés. Car il est évident qu’avec le point de vue doctrinaire du G20, toute l’industrie française finira par partir à l’extérieur. Il m’apparaît scandaleux que des entreprises ferment des sites rentables en France ou licencient, tandis qu’elles en ouvrent dans les zones à moindres coûts, comme cela a été le cas dans le secteur des pneumatiques pour automobiles, avec les annonces faites depuis le printemps par Continental et par Michelin. Si aucune limite n’est posée, ce qui va arriver peut d’ores et déjà être annoncé aux Français : une augmentation de la destruction d’emplois, une croissance dramatique du chômage non seulement dans l’industrie, mais tout autant dans l’agriculture et les services.

De ce point de vue, il est vrai que je ne fais pas partie des économistes qui emploient le mot « bulle ». Qu’il y ait des mouvements qui se généralisent, j’en suis d’accord, mais ce terme de « bulle » me semble inapproprié pour décrire le chômage qui résulte des délocalisations. En effet, sa progression revêt un caractère permanent et régulier, depuis maintenant plus de trente ans. L’essentiel du chômage que nous subissons —tout au moins du chômage tel qu’il s’est présenté jusqu’en 2008 — résulte précisément de cette libération inconsidérée du commerce à l’échelle mondiale sans se préoccuper des niveaux de vie. Ce qui se produit est donc autre chose qu’une bulle, mais un phénomène de fond, tout comme l’est la libéralisation des échanges, et la position de Pascal Lamy constitue bien une position sur le fond.

Crise et mondialisation sont liées

Les grands dirigeants mondiaux préfèrent, quant à eux, tout ramener à la monnaie, or elle ne représente qu’une partie des causes du problème. Crise et mondialisation : les deux sont liées. Régler seulement le problème monétaire ne suffirait pas, ne réglerait pas le point essentiel qu’est la libéralisation nocive des échanges internationaux, Le gouvernement attribue les conséquences sociales des délocalisations à des causes monétaires, c’est une erreur folle.

Pour ma part, j’ai combattu les délocalisations dans mes dernières publications (2). On connaît donc un peu mon message. Alors que les fondateurs du marché commun européen à six avaient prévu des délais de plusieurs années avant de libéraliser les échanges avec les nouveaux membres accueillis en 1986, nous avons ensuite, ouvert l’Europe sans aucune précaution et sans laisser de protection extérieure face à la concurrence de pays dotés de coûts salariaux si faibles que s’en défendre devenait illusoire. Certains de nos dirigeants, après cela, viennent s’étonner des conséquences !

Si le lecteur voulait bien reprendre mes analyses du chômage, telles que je les ai publiées dans les deux dernières décennies, il constaterait que les événements que nous vivons y ont été non seulement annoncés mais décrits en détail. Pourtant, ils n’ont bénéficié que d’un écho de plus en plus limité dans la grande presse. Ce silence conduit à s’interroger.

Un prix Nobel… téléspectateur

Les commentateurs économiques que je vois s’exprimer régulièrement à la télévision pour analyser les causes de l’actuelle crise sont fréquemment les mêmes qui y venaient auparavant pour analyser la bonne conjoncture avec une parfaite sérénité. Ils n’avaient pas annoncé l’arrivée de la crise, et ils ne proposent pour la plupart d’entre eux rien de sérieux pour en sortir. Mais on les invite encore. Pour ma part, je n’étais pas convié sur les plateaux de télévision quand j’annonçais, et j’écrivais, il y a plus de dix ans, qu’une crise majeure accompagnée d’un chômage incontrôlé allait bientôt se produire, je fais partie de ceux qui n’ont pas été admis à expliquer aux Français ce que sont les origines réelles de la crise alors qu’ils ont été dépossédés de tout pouvoir réel sur leur propre monnaie, au profit des banquiers. Par le passé, j’ai fait transmettre à certaines émissions économiques auxquelles j’assistais en téléspectateur le message que j’étais disposé à venir parler de ce que sont progressivement devenues les banques actuelles, le rôle véritablement dangereux des traders, et pourquoi certaines vérités ne sont pas dites à leur sujet. Aucune réponse, même négative, n’est venue d’aucune chaîne de télévision et ce durant des années.

Cette attitude répétée soulève un problème concernant les grands médias en France : certains experts y sont autorisés et d’autres, interdits. Bien que je sois un expert internationalement reconnu sur les crises économiques, notamment celles de 1929 ou de 1987, ma situation présente peut donc se résumer de la manière suivante : je suis un téléspectateur. Un prix Nobel… téléspectateur, Je me retrouve face à ce qu’affirment les spécialistes régulièrement invités, quant à eux, sur les plateaux de télévision, tels que certains universitaires ou des analystes financiers qui garantissent bien comprendre ce qui se passe et savoir ce qu’il faut faire. Alors qu’en réalité ils ne comprennent rien. Leur situation rejoint celle que j’avais constatée lorsque je m’étais rendu en 1933 aux États-Unis, avec l’objectif d’étudier la crise qui y sévissait, son chômage et ses sans-abri : il y régnait une incompréhension intellectuelle totale. Aujourd’hui également, ces experts se trompent dans leurs explications. Certains se trompent doublement en ignorant leur ignorance, mais d’autres, qui la connaissent et pourtant la dissimulent, trompent ainsi les Français.

Cette ignorance et surtout la volonté de la cacher grâce à certains médias dénotent un pourrissement du débat et de l’intelligence, par le fait d’intérêts particuliers souvent liés à l’argent. Des intérêts qui souhaitent que l’ordre économique actuel, qui fonctionne à leur avantage, perdure tel qu’il est. Parmi eux se trouvent en particulier les multinationales qui sont les principales bénéficiaires, avec les milieux boursiers et bancaires, d’un mécanisme économique qui les enrichit, tandis qu’il appauvrit la majorité de la population française mais aussi mondiale.

Question clé : quelle est la liberté véritable des grands médias ? Je parle de leur liberté par rapport au monde de la finance tout autant qu’aux sphères de la politique.

Deuxième question : qui détient de la sorte le pouvoir de décider qu’un expert est ou non autorisé à exprimer un libre commentaire dans la presse ?

Dernière question : pourquoi les causes de la crise telles qu’elles sont présentées aux Français par ces personnalités invitées sont-elles souvent le signe d’une profonde incompréhension de la réalité économique ? S’agit-il seulement de leur part d’ignorance ? C’est possible pour un certain nombre d’entre eux, mais pas pour tous. Ceux qui détiennent ce pouvoir de décision nous laissent le choix entre écouter des ignorants ou des trompeurs.

Maurice Allais.

_________________

(1) L’Europe en crise. Que faire ?, éditions Clément Juglar. Paris, 2005.

(2) Notamment La crise mondiale aujourd’hui, éditions Clément Juglar, 1999, et la Mondialisation, la destruction des emplois et de la croissance : l’évidence empirique, éditions Clément Juglar, 1999.

NB : vous pouvez télécharger cet article ici.

Présentation par Marianne

Le Prix Nobel iconoclaste et bâillonné

La « Lettre aux Français » que le seul et unique prix Nobel d’économie français a rédigée pour Marianne aura-t-elle plus d’écho que ses précédentes interventions ? Il annonce que le chômage va continuer à croître en Europe, aux États-Unis et dans le monde développé. Il dénonce la myopie de la plupart des responsables économiques et politiques sur la crise financière et bancaire qui n’est, selon lui, que le symptôme spectaculaire d’une crise économique plus profonde : la déréglementation de la concurrence sur le marché mondial de la main-d’œuvre. Depuis deux décennies, cet économiste libéral n’a cessé d’alerter les décideurs, et la grande crise, il l’avait clairement annoncée il y a plus de dix ans.

Éternel casse-pieds

Mais qui connaît Maurice Allais, à part ceux qui ont tout fait pour le faire taire ? On savait que la pensée unique n’avait jamais été aussi hégémonique qu’en économie, la gauche elle-même ayant fini par céder à la vulgate néolibérale. On savait le sort qu’elle réserve à ceux qui ne pensent pas en troupeau. Mais, avec le cas Allais, on mesure la capacité d’étouffement d’une élite habitée par cette idéologie, au point d’ostraciser un prix Nobel devenu maudit parce qu’il a toujours été plus soucieux des faits que des cases où il faut savoir se blottir.

« La réalité que l’on peut constater a toujours primé pour moi. Mon existence a été dominée par le désir de comprendre ce qui se passe, en économie comme en physique ». Car Maurice Allais est un physicien venu à l’économie à la vue des effets inouïs de la crise de 1929. Dès sa sortie de Polytechnique, en 1933, il part aux États-Unis. « C’était la misère sociale, mais aussi intellectuelle : personne ne comprenait ce qui était arrivé. » Misère à laquelle est sensible le jeune Allais, qui avait réussi à en sortir grâce à une institutrice qui le poussa aux études : fils d’une vendeuse veuve de guerre, il a, toute sa jeunesse, installé chaque soir un lit pliant pour dormir dans un couloir. Ce voyage américain le décide à se consacrer à l’économie, sans jamais abandonner une carrière parallèle de physicien reconnu pour ses travaux sur la gravitation. Il devient le chef de file de la recherche française en économétrie, spécialiste de l’analyse des marchés, de la dynamique monétaire et du risque financier. Il rédige, pendant la guerre, une théorie de l’économie pure qu’il ne publiera que quarante ans plus lard et qui lui vaudra le prix Nobel d’économie en 1988. Mais les journalistes japonais sont plus nombreux que leurs homologues français à la remise du prix : il est déjà considéré comme un vieux libéral ringardisé par la mode néolibérale.

Car, s’il croit à l’efficacité du marché, c’est à condition de le « corriger par une redistribution sociale des revenus illégitimes ». Il a refusé de faire partie du club des libéraux fondé par Friedrich von Hayek et Milton Friedman : ils accordaient, selon lui, trop d’importance au droit de propriété… « Toute ma vie d’économiste, j’ai vérifié la justesse de Lacordaire : entre le fort et le faible, c’est la liberté qui opprime et la règle qui libère”, précise Maurice Allais, dont Raymond Aron avait bien résumé la position : « Convaincre des socialistes que le vrai libéral ne désire pas moins qu’eux la justice sociale, et des libéraux que l’efficacité de l’économie de marché ne suffit plus à garantir une répartition acceptable des revenus. » Il ne convaincra ni les uns ni les autres, se disant « libéral et socialiste ».

Éternel casse-pieds inclassable. Il aura démontré la faillite économique soviétique en décryptant le trucage de ses statistiques. Favorable à l’indépendance de l’Algérie, il se mobilise en faveur des harkis au point de risquer l’internement administratif. Privé de la chaire d’économie de Polytechnique car trop dirigiste, « je n’ai jamais été invité à l’ENA, j’ai affronté des haines incroyables ! » Après son Nobel, il continue en dénonçant « la chienlit laisser-fairiste » du néolibéralisme triomphant. Seul moyen d’expression : ses chroniques touffues publiées dans le Figaro, où le protège Alain Peyrefitte. À la mort de ce dernier, en 1999, il est congédié comme un malpropre.

Il vient de publier une tribune alarmiste dénonçant une finance de « casino» : « L’économie mondiale tout entière repose aujourd’hui sur de gigantesques pyramides de dettes, prenant appui les unes sur les autres dans un équilibre fragile, jamais dans le passé une pareille accumulation de promesses de payer ne s’était constatée. Jamais, sans doute, il est devenu plus difficile d’y faire face, jamais, sans doute, une telle instabilité potentielle n’était apparue avec une telle menace d’un effondrement général. » Propos développés l’année suivante dans un petit ouvrage très lisible* qui annonce l’effondrement financier dix ans à l’avance. Ses recommandations en faveur d’un protectionnisme européen, reprises par Chevènement et Le Pen, lui valurent d’être assimilé au diable par les gazettes bien-pensantes. En 2005, lors de la campagne sur le référendum européen, le prix Nobel veut publier une tribune expliquant comment Bruxelles, reniant le marché commun en abandonnant la préférence communautaire, a brisé sa croissance économique et détruit ses emplois, livrant l’Europe au dépeçage industriel : elle est refusée partout, seule l’Humanité accepte de la publier…

Aujourd’hui, à 98 ans, le vieux savant pensait que sa clairvoyance serait au moins reconnue. Non, silence total, à la notable exception du bel hommage que lui a rendu Pierre-Antoine Delhommais dans le Monde. Les autres continuent de tourner en rond, enfermés dans leur « cercle de la raison » •

Éric Conan

* La Crise mondiale aujourd’hui, éditions Clément Juglar, 1999.

Source : Marianne, n°659, décembre 2009.

Extraits choisis

J’ai repris certains de ces extraits dans mon livre STOP ! Tirons les leçons de la Crise.

« Depuis deux décennies une nouvelle doctrine s’est peu à peu imposée, la doctrine du libre-échange mondialiste impliquant la disparition de tout obstacle aux libres mouvements des marchandises, des services et des capitaux. Suivant cette doctrine, la disparition de tous les obstacles à ces mouvements serait une condition à la fois nécessaire et suffisante d’une allocation optimale des ressources à l’échelle mondiale. Tous les pays et, dans chaque pays, tous les groupes sociaux verraient leur situation améliorée. Le marché, et le marché seul, était considéré comme pouvant conduire à un équilibre stable, d’autant plus efficace qu’il pouvait fonctionner à l’échelle mondiale. En toutes circonstances, il convenait de se soumettre à sa discipline. […]

Les partisans de cette doctrine, de ce nouvel intégrisme, étaient devenus aussi dogmatiques que les partisans du communisme avant son effondrement définitif avec la chute du Mur de Berlin en 1989. […]

Suivant une opinion actuellement dominante, le chômage, dans les économies occidentales, résulterait essentiellement de salaires réels trop élevés et de leur insuffisante flexibilité, du progrès technologique accéléré qui se constate dans les secteurs de l’information et des transports, et d’une politique monétaire jugée indûment restrictive.

En fait, ces affirmations n’ont cessé d’être infirmées aussi bien par l’analyse économique que par les données de l’observation. La réalité, c’est que la mondialisation est la cause majeure du chômage massif et des inégalités qui ne cessent de se développer dans la plupart des pays. Jamais, des erreurs théoriques n’auront eu autant de conséquences aussi perverses. […]

La récente réunion du G20 a de nouveau proclamé sa dénonciation du « protectionnisme », dénonciation absurde à chaque fois qu’elle se voit exprimée sans nuance, comme cela vient d’être le cas. Nous sommes confrontés à ce que j’ai par le passé nommé « des tabous indiscutés dont les effets pervers se sont multipliés et renforcés au cours des années ». Car tout libéraliser, on vient de le vérifier, amène les pires désordres.

Les grands dirigeants de la planète montrent une nouvelle fois leur ignorancede l’économie qui les conduit à confondre deux sortes de protectionnismes : il en existe certains de néfastes, tandis que d’autres sont entièrement justifiés. Dans la première catégorie se trouve le protectionnisme entre pays à salaires comparables, qui n’est pas souhaitable en général. Par contre, le protectionnisme entre pays de niveaux de vie très différents est non seulement justifié, mais absolument nécessaire. C’est en particulier le cas à propos de la Chine, avec laquelle il est fou d’avoir supprimé les protections douanières aux frontières. Mais c’est aussi vrai avec des pays plus proches, y compris au sein même de l’Europe. Il suffit au lecteur de s’interroger sur la manière éventuelle de lutter contre des coûts de fabrication cinq ou dix fois moindres – si ce n’est des écarts plus importants encore – pour constater que la concurrence n’est pas viable dans la grande majorité des cas.

Toute cette analyse montre que la libéralisation totale des mouvements de biens, de services et de capitaux à l’échelle mondiale, objectif affirmé de l’Organisation Mondiale du Commerce (OMC) à la suite du GATT, doit être considérée à la fois comme irréalisable, comme nuisible, et comme non souhaitable. […]

Plus concrètement, les règles à dégager sont d’une simplicité folle : du chômage résulte des délocalisations, elles-mêmes dues aux trop grandes différences de salaires… À partir de ce constat, ce qu’il faut entreprendre en devient tellement évident ! Il est indispensable de rétablir une légitime protection. […]

En fait, on ne saurait trop le répéter, la libéralisation totale des échanges et des mouvements de capitaux n’est possible et n’est souhaitable que dans le cadre d’ensembles régionaux, groupant des pays économiquement et politiquement associés, de développement économique et social comparable, tout en assurant un marché suffisamment large pour que la concurrence puisse s’y développer de façon efficace et bénéfique. […]

Chaque organisation régionale doit pouvoir mettre en place dans un cadre institutionnel, politique et éthique approprié une protection raisonnable vis-à-vis de l’extérieur. Cette protection doit avoir un double objectif :

- éviter les distorsions indues de concurrence et les effets pervers des perturbations extérieures;

- rendre impossibles des spécialisations indésirables et inutilement génératrices de déséquilibres et de chômage, tout à fait contraires à la réalisation d’une situation d’efficacité maximale à l’échelle mondiale, associée à une répartition internationale des revenus communément acceptable dans un cadre libéral et humaniste.

Dès que l’on transgresse ces principes, une mondialisation forcenée et anarchique devient un fléau destructeur, partout où elle se propage. […]

L’absence d’une telle protection apportera la destruction de toute l’activité de chaque pays ayant des revenus plus élevés, c’est-à-dire de toutes les industries de l’Europe de l’Ouest et celles des pays développés. Car il est évident qu’avec le point de vue doctrinaire du G20, toute l’industrie française finira par partir à l’extérieur. Il m’apparaît scandaleux que des entreprises ferment des sites rentables en France ou licencient, tandis qu’elles en ouvrent dans les zones à moindres coûts […]. Si aucune limite n’est posée, ce qui va arriver peut d’ores et déjà être annoncé aux Français : une augmentation de la destruction d’emplois, une croissance dramatique du chômage non seulement dans l’industrie, mais tout autant dans l’agriculture et les services. »

« En réalité, ceux qui, à Bruxelles et ailleurs, au nom des prétendues nécessités d’un prétendu progrès, au nom d’un libéralisme mal compris, et au nom de l’Europe, veulent ouvrir l’Union Européenne à tous les vents d’une économie mondialiste dépourvue de tout cadre institutionnel réellement approprié et dominée par la loi de la jungle, et la laisser désarmée sans aucune protection raisonnable ; ceux qui, par là même, sont d’ores et déjà personnellement et directement responsables d’innombrables misères et de la perte de leur emploi par des millions de chômeurs, ne sont en réalité que les défenseurs d’une idéologie abusivement simplificatrice et destructrice, les hérauts d’une gigantesque mystification. […]

Au nom d’un pseudo-libéralisme, et par la multiplication des déréglementations, s’est installée peu à peu une espèce de chienlit mondialiste laissez-fairiste. Mais c’est là oublier que l’économie de marché n’est qu’un instrument et qu’elle ne saurait être dissociée de son contexte institutionnel et politique et éthique. Il ne saurait être d’économie de marché efficace si elle ne prend pas place dans un cadre institutionnel et politique approprié, et une société libérale n’est pas et ne saurait être une société anarchique.

Cette domination se traduit par un incessant matraquage de l’opinion par certains médias financés par de puissants lobbies plus ou moins occultes. Il est pratiquement interdit de mettre en question la mondialisation des échanges comme cause du chômage.

Personne ne veut, ou ne peut, reconnaître cette évidence : si toutes les politiques mises en œuvre depuis trente ans ont échoué, c’est que l’on a constamment refusé de s’attaquer à la racine du mal, la libéralisation mondiale excessive des échanges. Les causes de nos difficultés sont très nombreuses et très complexes, mais une d’elles domine toutes les autres : la suppression progressive de la Préférence Communautaire à partir de 1974 par “l’Organisation de Bruxelles” à la suite de l’entrée de la Grande Bretagne dans l’Union Européenne en 1973.

La mondialisation de l’économie est certainement très profitable pour quelques groupes de privilégiés. Mais les intérêts de ces groupes ne sauraient s’identifier avec ceux de l’humanité tout entière. Une mondialisation précipitée et anarchique ne peut qu’engendrer partout instabilité, chômage, injustices, désordres, et misères de toutes sortes, et elle ne peut que se révéler finalement désavantageuse pour tous les peuples.»

« En réalité, l’économie mondialiste qu’on nous présente comme une panacée ne connaît qu’un seul critère, “l’argent”. Elle n’a qu’un seul culte, “l’argent”. Dépourvue de toute considération éthique, elle ne peut que se détruire elle-même.

Partout se manifeste une régression des valeurs morales, dont une expérience séculaire a montré l’inestimable et l’irremplaçable valeur. Le travail, le courage, l’honnêteté ne sont plus honorés. La réussite économique, fondée trop souvent sur des revenus indus, ne tend que trop à devenir le seul critère de la considération publique.

En engendrant des inégalités croissantes et la suprématie partout du culte de l’argent avec toutes ses implications, le développement d’une politique de libéralisation mondialiste anarchique a puissamment contribué à accélérer la désagrégation morale des sociétés occidentales. »

[Maurice Allais, extraits rédigés entre 1990 et 2009]

« Cette doctrine [la « chienlit mondialiste laissez-fairiste »] a été littéralement imposée aux gouvernements américains successifs, puis au monde entier, par les multinationales américaines, et à leur suite par les multinationales dans toutes les parties du monde, qui en fait détiennent partout en raison de leur considérable pouvoir financier et par personnes interposées la plus grande partie du pouvoir politique. La mondialisation, on ne saurait trop le souligner, ne profite qu’aux multinationales. Elles en tirent d’énormes profits.

« Cette doctrine [la « chienlit mondialiste laissez-fairiste »] a été littéralement imposée aux gouvernements américains successifs, puis au monde entier, par les multinationales américaines, et à leur suite par les multinationales dans toutes les parties du monde, qui en fait détiennent partout en raison de leur considérable pouvoir financier et par personnes interposées la plus grande partie du pouvoir politique. La mondialisation, on ne saurait trop le souligner, ne profite qu’aux multinationales. Elles en tirent d’énormes profits.

Cette évolution s’est accompagnée d’une multiplication de sociétés multinationales ayant chacune des centaines de filiales, échappant à tout contrôle, et elle ne dégénère que trop souvent dans le développement d’un capitalisme sauvage et malsain. […]

Cette ignorance [des ressorts véritables de la crise actuelle par les « experts » officiels] et surtout la volonté de la cacher grâce à certains médias dénotent un pourrissement du débat et de l’intelligence, par le fait d’intérêts particuliers souvent liés à l’argent. Des intérêts qui souhaitent que l’ordre économique actuel, qui fonctionne à leur avantage, perdure tel qu’il est. Parmi eux se trouvent en particulier les multinationales qui sont les principales bénéficiaires, avec les milieux boursiers et bancaires, d’un mécanisme économique qui les enrichit, tandis qu’il appauvrit la majorité de la population française mais aussi mondiale. » [Maurice Allais, 1998 et 2009]

L’analyse de Maurice Allais sur la création monétaire

« En fait, sans la création de monnaie et de pouvoir d’achat ex nihilo que permet le système du crédit, jamais les hausses extraordinaires des cours de bourse que l’on constate avant les grandes crises ne seraient possibles, car à toute dépense consacrée à l’achat d’actions, par exemple, correspondrait quelque part une diminution d’un montant équivalent de certaines dépenses, et tout aussitôt se développeraient des mécanismes régulateurs tendant à enrayer toute spéculation injustifiée.

Qu’il s’agisse de la spéculation sur les monnaies ou de la spéculation sur les actions, ou de la spéculation sur les produits dérivés, le monde est devenu un vaste casino où les tables de jeu sont réparties sur toutes les longitudes et toutes les latitudes. Le jeu et les enchères, auxquelles participent des millions de joueurs, ne s’arrêtent jamais. Aux cotations américaines se succèdent les cotations à Tokyo et à Hongkong, puis à Londres, Francfort et Paris.

Partout, la spéculation est favorisée par le crédit puisqu’on peut acheter sans payer et vendre sans détenir. On constate le plus souvent une dissociation entre les données de l’économie réelle et les cours nominaux déterminés par la spéculation.

Sur toutes les places, cette spéculation, frénétique et fébrile, est permise, alimentée et amplifiée par le crédit. Jamais dans le passé elle n’avait atteint une telle ampleur.

L’économie mondiale tout entière repose aujourd’hui sur de gigantesques pyramides de dettes, prenant appui les unes sur les autres dans un équilibre fragile. Jamais dans le passé une pareille accumulation de promesses de payer ne s’était constatée. Jamais sans doute il n’est devenu plus difficile d’y faire face. Jamais sans doute une telle instabilité potentielle n’était apparue avec une telle menace d’un effondrement général.

Toutes les difficultés rencontrées résultent de la méconnaissance d’un fait fondamental, c’est qu’aucun système décentralisé d’économie de marchés ne peut fonctionner correctement si la création incontrôlée ex-nihilo de nouveaux moyens de paiement permet d’échapper, au moins pour un temps, aux ajustements nécessaires. [...]

Au centre de toutes les difficultés rencontrées, on trouve toujours, sous une forme ou une autre, le rôle néfaste joué par le système actuel du crédit et la spéculation massive qu’il permet. Tant qu’on ne réformera pas fondamentalement le cadre institutionnel dans lequel il joue, on rencontrera toujours, avec des modalités différentes suivant les circonstances, les mêmes difficultés majeures. Toutes les grandes crises du XIXe et du XXe siècle ont résulté du développement excessif des promesses de payer et de leur monétisation.

Particulièrement significative est l’absence totale de toute remise en cause du fondement même du système de crédit tel qu’il fonctionne actuellement, savoir la création de monnaie ex-nihilo par le système bancaire et la pratique généralisée de financements longs avec des fonds empruntés à court terme.

En fait, sans aucune exagération, le mécanisme actuel de la création de monnaie par le crédit est certainement le “cancer” qui ronge irrémédiablement les économies de marchés de propriété privée. [...]

Que les bourses soient devenues de véritables casinos, où se jouent de gigantesques parties de poker, ne présenterait guère d’importance après tout, les uns gagnant ce que les autres perdent, si les fluctuations générales des cours n’engendraient pas, par leurs implications, de profondes vagues d’optimisme ou de pessimisme qui influent considérablement sur l’économie réelle. [...] Le système actuel est fondamentalement anti-économique et défavorable à un fonctionnement correct des économies. Il ne peut être avantageux que pour de très petites minorités. »

[Maurice Allais, La Crise mondiale d’aujourd’hui. Pour de profondes réformes des institutions financières et monétaires, 1998]

« Ce qui, pour l’essentiel, explique le développement de l’ère de prospérité générale, aux États-Unis et dans le monde, dans les années qui ont précédé le krach de 1929, c’est l’ignorance, une ignorance profonde de toutes les crises du XIXème siècle et de leur signification réelle. En fait, toutes les grandes crises des XIXème et XXème siècles ont résulté du développement excessif des promesses de payer et de leur monétisation. Partout et à toute époque, les mêmes causes génèrent les mêmes effets et ce qui doit arriver arrive. » [Maurice Allais]

« Ce livre est dédié aux innombrables victimes dans le monde entier de l’idéologie libre-échangiste mondialiste, idéologie aussi funeste qu’erronée, et à tous ceux que n’aveugle pas quelque passion partisane. » [Maurice Allais, prix Nobel d’économie en 1988, préface de La mondialisation : La destruction des emplois et de la croissance, l'évidence empirique, 1999]

Le libéralisme contre le laissez-fairisme

« Les premiers libéraux ont commis une erreur fondamentale en soutenant que le régime de laisser-faire constituait un état économique optimum. » [Maurice Allais, Traité d’économie pure, 1943]

« Le libéralisme ne saurait se réduire au laissez-faire économique ; c’est avant tout une doctrine politique, et le libéralisme économique n’est qu’un moyen permettant à cette politique de s’appliquer efficacement dans le domaine économique. Originellement, d’ailleurs, il n’y avait aucune contradiction entre les aspirations du socialisme et celles du libéralisme.

La confusion actuelle du libéralisme et du laissez-fairisme constitue un des plus grands dangers de notre temps. Une société libérale et humaniste ne saurait s’identifier à une société laxiste, laissez-fairiste, pervertie, manipulée, ou aveugle.

La confusion du socialisme et du collectivisme est tout aussi funeste.

En réalité, l’économie mondialiste qu’on nous présente comme une panacée ne connait qu’un critère, “l’argent”. Elle n’a qu’un seul culte, “l’argent”. Dépourvue de toute considération éthique, elle ne peut que se détruire elle-même.

Les perversions du socialisme ont entrainé l’effondrement des sociétés de l’Est. Mais les perversions laissez-fairistes d’un prétendu libéralisme mènent à l’effondrement des sociétés occidentales. » [Maurice Allais, Nouveaux combats pour l’Europe, 2002]

« Une proposition enseignée et admise sans discussion dans toutes les universités américaines et à leur suite dans toutes les universités du monde entier : “Le fonctionnement libre et spontané du marché conduit à une allocation optimale des ressources”.

C’est là le fondement de toute la doctrine libre-échangiste dont l’application aveugle et sans réserve à l’échelle mondiale n’a fait qu’engendrer partout désordres et misères de toutes sortes.

Or, cette proposition, admise sans discussion, est totalement erronée, et elle-ne fait que traduire une totale ignorance de la théorie économique chez tous ceux qui l’ont enseignée en la présentant comme une acquisition fondamentale et définitivement établie de la science économique.

Cette proposition repose essentiellement sur la confusion de deux concepts différents : le concept d’efficacité maximale de l’économie et le concept d’une répartition optimale des revenus.

En fait, il n’y a pas une situation d’efficacité maximale, mais une infinité de telles situations. La théorie économique permet de définir sans ambiguïté les conditions d’une efficacité maximale, c’est-à-dire d’une situation sur la frontière entre les situations possibles et les situations impossibles. Par contre et par elle-même, elle ne permet en aucune façon de définir parmi toutes les situations d’efficacité maximale celle qui doit être considérée comme préférable. Ce choix ne peut être effectué qu’en fonction de considérations éthiques et politiques relatives à la répartition des revenus et à l’organisation de la société.

De plus, il n’est même pas démontré qu’à partir d’une situation initiale donnée le fonctionnement libre des marchés puisse mener le monde à une situation d’efficacité maximale.

Jamais des erreurs théoriques n’auront eu autant de conséquences aussi perverses. » [Maurice Allais, Discours à l’UNESCO du 10 avril 1999]

La théorie contre les faits

« C’est toujours le phénomène concret qui décide si une théorie doit être acceptée ou repoussée. Il n’y a pas, et il ne peut y avoir d’autre critère de la vérité d’une théorie que son accord plus ou moins parfait avec les phénomènes observés. Trop d’experts n’ont que trop tendance à ne pas tenir compte des faits qui viennent contredire leurs convictions.

À chaque époque, les conceptions minoritaires n’ont cessées d’être combattues et rejetées par la puissance tyrannique des “vérités établies”. De tout temps, un fanatisme dogmatique et intolérant n’a cessé de s’opposer aux progrès de la science et à la révision des postulats correspondant aux théories admises et qui venaient les invalider. […] En fait, le consentement universel, et a fortiori celui de la majorité, ne peuvent jamais être considérés comme des critères de la vérité. En dernière analyse, la condition essentielle du progrès, c’est une soumission entière aux enseignements de l’expérience, seule source réelle de notre connaissance. […]

Tôt ou tard, les faits finissent par l’emporter sur les théories qui les nient. La science est en perpétuel devenir. Elle finit toujours par balayer les “vérités établies”.

Depuis les années 1970, un credo s’est peu à peu imposé : la mondialisation est inévitable et souhaitable ; elle seule peut nous apporter la prospérité et l’emploi.

Bien que très largement majoritaire, cette doctrine n’a cependant cessé d’être contredite par le développement d’un chômage persistant qu’aucune politique n’a pu réduire, faute d’un diagnostic correct.

N’en doutons pas, comme toutes les théories fausses du passé, cette doctrine finira par être balayée par les faits, car les faits sont têtus. » [Maurice Allais, Nouveaux combats pour l’Europe, 2002]

« Si utiles et si compétents que puissent être les experts, si élaborés que puissent être leurs modèles, tous ceux qui les consultent doivent rester extrêmement prudents. Tout organisme qui emploie une équipe pour l’établissement de modèles prévisionnels ou décisionnels serait sans doute avisé d’en employer une autre pour en faire la critique, et naturellement de recruter cette équipe parmi ceux qui ne partagent pas tout-à-fait les convictions de la première. » [Maurice Allais, Conférence du 23/10/1967, « L’Économique en tant que Science »]

« Si les taux de change ne correspondent pas à l’équilibre des balances commerciales, le libre-échange ne peut être que nuisible et fondamentalement désavantageux pour tous les pays participants. » [Maurice Allais, Combats pour l'Europe, 1994]

Une application erronée d’une théorie correcte : la théorie des coûts comparés.

« La justification de la politique de libre-échange mondialisé de l’OMC se fonde dans ses principes sur la théorie des coûts comparés présentée par Ricardo en 1817. [NDR : elle explique que, dans un contexte de libre-échange, chaque pays, s’il se spécialise dans la production pour laquelle il dispose de la productivité la plus forte ou la moins faible, comparativement à ses partenaires, accroîtra sa richesse nationale. Ricardo donne l’exemple de l’avantage comparatif du vin pour le Portugal, et des draps pour l’Angleterre]

Mais ce modèle repose sur une hypothèse essentielle, à savoir que la structure des coûts comparatifs reste invariable au cours du temps. En fait, il n’en est ainsi que dans le cas des ressources naturelles. [...] Par contre, dans le domaine industriel, aucun avantage comparatif ne saurait être considéré comme permanent. Chaque pays aspire légitimement à rendre ses industries plus efficaces, et il est souhaitable qu’il puisse y réussir. Il résulte de là que la diminution ou la disparition de certaines activités dans un pays développé en raison des avantages comparatifs d’aujourd’hui pourront se révéler demain fondamentalement désavantageuses dès lors que ces avantages comparatifs disparaitront et qu’il faudra rétablir ces activités. Tel est le cas, par exemple aujourd’hui en France de la sidérurgie, du textile, de la construction navale. [...]

Même lorsqu’il existe des avantages comparatifs de caractère permanent, il peut être tout à fait contre-indiqué de laisser s’établir les spécialisations qui seraient entrainées par une politique généralisée de libre-échange. Ainsi dans le cas de l’agriculture, le libre-échange n’aurait d’autre effet que de faire disparaitre presque totalement l’agriculture de l’Union européenne [ce qui serait] de nature à compromettre son indépendance en matière alimentaire. [...]

Bien plus encore, la théorie simpliste et naïve du commerce international sur laquelle s’appuient les grands gourous du libre-échange mondialiste néglige complètement les coûts externes et les coûts de transition, et elle ne tient aucun compte des coûts psychologiques, très supérieurs aux coûts monétaires, subis par tous ceux que la libéralisation des échanges condamne au chômage et à la détresse. [Maurice Allais, prix Nobel d’économie en 1988, préface de La mondialisation : La destruction des emplois et de la croissance, l'évidence empirique, 1999]

« La concurrence est naturellement malfaisante. Elle devient bienfaisante lorsqu’elle s’exerce dans le cadre juridique qui la plie aux exigences de l’optimum du rendement social. » [Maurice Allais, 1943]

« Je suis convaincu qu’aucune société ne peut longtemps survivre si trop d’injustices sont tolérées. » [Maurice Allais, La lutte contre les inégalités, le projet d’un impôt sur les grosses fortunes et la réforme de la fiscalité, 1979]

« Notre société parait évoluer lentement, mais sûrement, vers une organisation de plus en plus rigide, vers certaines formes de corporatisme, comme celles qui les ont enserrées dans leurs carcans pendant tant de siècles, et que Turgot dénonçait à la veille de la Révolution française. Elle parait se diriger presque inéluctablement vers des systèmes antidémocratiques, tout simplement parce que l’incompréhension de la nature véritable d’un ordre libéral et l’ignorance rendent son fonctionnement impossible, parce que la démocratie, telle qu’elle parait entendue aujourd’hui, mène au désordre, et que des millions d’hommes, pénétrés d’idéologies irréalisables, ne pourront survivre que dans le cadre de régimes centralisés et autoritaires.

Nous visons des temps à de nombreux points semblables à ceux qui ont précédé ou accompagné la décadence de l’empire romain. […] Aujourd’hui comme alors, des féodalités ploutocratiques, politicocratiques et technocratiques s’emparent de l’État. […] Aujourd’hui comme alors, nous assistons indifférents et sans la comprendre, à une transformation profonde de la société qui, si elle se poursuit, entrainera inévitablement la fin de notre civilisation.

Le pessimisme que peut suggérer cette analyse ne conduit pas nécessairement à l’inaction : l’avenir dépend encore, pour une large part, de ce que nous ferons. Mais ceux qui sont réellement attachés à une société libre seront-ils assez lucides, seront-ils capables d’apercevoir les sources réelles de nos maux et les moyens d’y remédier, consentiront-ils à l’effort nécessaire, d’une ampleur tout à fait exceptionnelle, qui pourrait, peut-être, sauvegarder les conditions d’une société libre ?

Le passé ne nous offre que trop d’exemples de sociétés qui se sont effondrées pour n’avoir su ni concevoir, ni réaliser les conditions de leur survie. » [Maurice Allais, conclusion de L’impôt sur le capital et la réforme monétaire, 1977]

Sa dernière interview

Extraits de la dernière interview de Maurice Allais, réalisée l’été 2010 par Lise Bourdeau-Lepage et Leïla Kebir pour Géographie, économie, société, 2010/2

L’origine de mon engagement est sans conteste la crise de 1929. [...] Étant sorti major de ma promotion, j’ai pu faire en sorte qu’une bourse d’étude universitaire soit attribuée à plusieurs élèves pour que nous effectuions un voyage d’étude sur place, à l’été 1933. Le spectacle sur place était saisissant. On ne pourrait se l’imaginer aujourd’hui. La misère et la mendicité était présentes partout dans les rues, dans des proportions incroyables. Mais ce qui fut le plus étonnant était l’espèce de stupeur qui avait gagné les esprits, une sorte d’incompréhension face aux évènements qui touchait non seulement l’homme de la rue mais aussi les universitaires, car notre programme de voyage comprenait des rencontres dans de grandes universités : tous nos interlocuteurs semblaient incapables de formuler une réponse. Ma vocation est venue de ce besoin d’apporter une explication, pour éviter à l’avenir la répétition de tels évènements. [...] Pour moi, ce qui compte avant tout dans l’économie et la société, c’est l’homme. [...]

Beaucoup de gens se sont mépris sur mon compte. Je me revendique d’inspiration à la fois libérale et sociale. Mais de nombreux observateurs ne voient qu’un seul de ces aspects, selon ce qu’ils ont envie de regarder. Par ailleurs, j’ai constamment cherché à lutter contre les idéologies dominantes, et mes combats ont évolué en fonction de l’évolution parallèle de ces dogmes successifs. Ceci explique en grande partie les incompréhensions car on n’observe alors que des bribes incomplètes. [...]

{Question : Vous soutenez par exemple, à propos de l’impôt, qu’il faudrait ne pas imposer le revenu du travail mais par contre taxer complètement l’héritage. Pouvez-vous expliquer cette position qui peut paraître très iconoclaste pour bon nombre d’économistes ?}

J’ai qualifié l’impôt sur le revenu de système anti-économique et anti-social, car il est assis sur le travail physique ou intellectuel, sur l’effort, sur le courage. Il est l’expression d’une forme d’iniquité. Baser la fiscalité sur les activités créatrices de richesse est un non sens, tandis que ce que j’ai nommé les revenus « non gagnés » sont pour leur part trop protégés : à savoir par exemple l’appropriation privée des rentes foncières, lorsque la valeur ou le revenu des terrains augmente sans que cette hausse ne résulte d’un quelconque mérite de son propriétaire, mais de décisions de la collectivité ou d’un accroissement de la population. [...]

Je crains que l’économie et la société aient eu durant ces dernières décennies une tendance régulière à oublier le rôle central de la morale, qui est une forme de philosophie de la vie en collectivité. [...]

J’ai depuis toujours, et surtout depuis plus de vingt ans, suggéré des modifications en profondeur des systèmes financiers et bancaires, ainsi que des règles du commerce international. Il faut réformer les banques, réformer le crédit, réformer le mode de création de la monnaie, réformer la bourse et son fonctionnement aberrant, réformer l’OMC et le FMI, car tout se tient. Leur organisation actuelle est directement à l’origine non

seulement de la crise, mais des précédentes, et des suivantes si l’ont n’agit pas. Mes propositions existent et il aurait suffi de s’y référer. Mais ce qui manque est la volonté. Les gouvernements n’écoutent que les conseillers qui sont trop proches des milieux financiers ou économiques en place. On ne cherche pas à s’adresser à des experts plus indépendants. [...]

Les mathématiques ont pris au fil du temps une place excessive, particulièrement dans leurs applications financières. Il ne faut pas imaginer que ceci a toujours existé. [...] Mais par la suite, des économistes ont détourné ces apports, qui sont devenus des instruments pour imposer une analyse, mais sans chercher à la confronter à la réalité. De même, l’utilisation de certains modèles a causé des torts importants à Wall Street. Je rappelle d’ailleurs avoir de longue date demandé une révision de ces comportements, et par exemple l’interdiction des programmes informatiques automatiques qui sont utilisés par les financiers pour spéculer en Bourse.

Liens

Un lien vers des extraits de sa vision sur “la mondialisation, le chômage et les impératifs de l’humanisme”

Vous trouverez ici une synthèse de son excellent livre de 1998 La crise mondiale d’aujourd’hui, que je vous recommande particulièrement, pour comprendre la crise actuelle (épuisé, donc à voir d’occasion).

Vous trouverez ici une synthèse de son livre L’Europe en crise

Ici une interview dans La Jaune et la Rouge

Ici un lien vers son article de 2005 : Les effets destructeurs de la Mondialisation

Épilogue

Je signale enfin que la fille de Maurice Allais travaille actuellement (avec difficultés) à la création d’une fondation afin de perpétuer le savoir du grand Maurice Allais. Elle se bat aussi pour préserver sa très riche bibliothèque de plus de 12 000 livres…

Plus d’informations sur sa page Wikipedia et sur l’Association AIRAMA qui lui est consacrée.

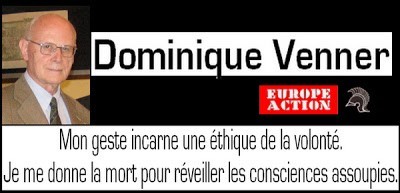

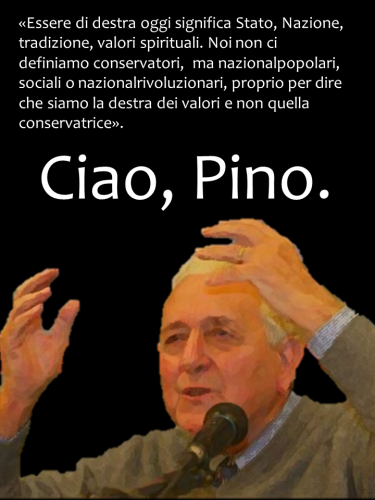

Then again, suicide is almost always a dramatic gesture, thick with a certain pungent and romantic resonance. (Think of Romeo and Juliet, who killed themselves for one another’s sake, and for the glories of eternal love.) Contrary to the tiresome bromides of certain scoldy after-school-special-esque moralists, suicide is most emphatically not a “cowardly” act. Venner’s fiercely uncompromising, literally mind-blowing self-directed strike was bold indeed; it serves as a fittingly emphatic exclamation mark at the end of a fiercely uncompromising life. Normally, self-extinguishment cannot help but translate as an expression of desperate despair, although in certain, culturally-circumscribed cases, it can carry a defiant, “death before dishonor” type of message. Venner, like Yukio Mishima before him, seems to have opted to end his life as a kind of protest against prevailing social trends. Like the famously iconic image of the self-immolating Buddhist monk in Vietnam, he chose to make his death a high profile event, the better to register his posthumous displeasure with the Zeitgeist.

Then again, suicide is almost always a dramatic gesture, thick with a certain pungent and romantic resonance. (Think of Romeo and Juliet, who killed themselves for one another’s sake, and for the glories of eternal love.) Contrary to the tiresome bromides of certain scoldy after-school-special-esque moralists, suicide is most emphatically not a “cowardly” act. Venner’s fiercely uncompromising, literally mind-blowing self-directed strike was bold indeed; it serves as a fittingly emphatic exclamation mark at the end of a fiercely uncompromising life. Normally, self-extinguishment cannot help but translate as an expression of desperate despair, although in certain, culturally-circumscribed cases, it can carry a defiant, “death before dishonor” type of message. Venner, like Yukio Mishima before him, seems to have opted to end his life as a kind of protest against prevailing social trends. Like the famously iconic image of the self-immolating Buddhist monk in Vietnam, he chose to make his death a high profile event, the better to register his posthumous displeasure with the Zeitgeist.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

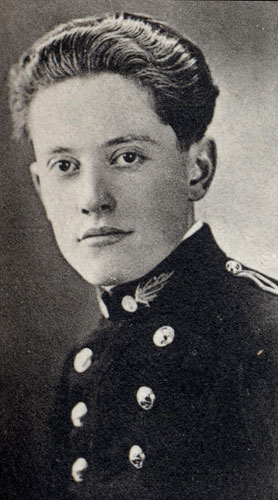

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Saenz de Heredia Marques de Estella or José Antonio (as he is more commonly called) was born on April 24, 1903 in Madrid to grow up in a healthy aristocratic family environment as the eldest son of General Miguel Primo de Rivera, who was the Leader of Spain from 1923 to 1930. His family was socially prominent in Andalusia, having intermarried with large landholders and merchants around Jerez de la Frontera. From his father José Antonio inherited the title marqués de Estella.

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Saenz de Heredia Marques de Estella or José Antonio (as he is more commonly called) was born on April 24, 1903 in Madrid to grow up in a healthy aristocratic family environment as the eldest son of General Miguel Primo de Rivera, who was the Leader of Spain from 1923 to 1930. His family was socially prominent in Andalusia, having intermarried with large landholders and merchants around Jerez de la Frontera. From his father José Antonio inherited the title marqués de Estella. Es war ein ruhiger Abend auf See. Rudolf Diesel hatte im Speisesaal des luxuriösen Passagierdampfers “Dresden” mit einem bekannten Industriellen zu Abend gegessen. Der große, stattliche Mann mit Brille und Schnauzer war auf dem Weg nach London, wo er ein Motorenwerk einweihen sollte. In bester Laune hatte der 55-Jährige vom Deck aus noch die sternklare Nacht vom 29. auf den 30. September 1913 bewundert. Dann machte sich Rudolf Diesel, der Erfinder des Dieselmotors, auf den Weg in seine Kabine. Dies war der Augenblick, in dem er das letzte Mal gesehen wurde.

Es war ein ruhiger Abend auf See. Rudolf Diesel hatte im Speisesaal des luxuriösen Passagierdampfers “Dresden” mit einem bekannten Industriellen zu Abend gegessen. Der große, stattliche Mann mit Brille und Schnauzer war auf dem Weg nach London, wo er ein Motorenwerk einweihen sollte. In bester Laune hatte der 55-Jährige vom Deck aus noch die sternklare Nacht vom 29. auf den 30. September 1913 bewundert. Dann machte sich Rudolf Diesel, der Erfinder des Dieselmotors, auf den Weg in seine Kabine. Dies war der Augenblick, in dem er das letzte Mal gesehen wurde.

C’était le seul prix Nobel d’économie français. Né le 31 mai 1911, il part aux États-Unis dès sa sortie (major X31) de Polytechnique en 1933 pour étudier in situ la Grande Dépression qui a suivi la Crise de 1929. Ironie de l’histoire, il a ainsi pu réaliser une sorte de “jonction” entre les deux Crises majeures du siècle. Son analyse, percutante et dérangeante, n’a malheureusement pas été entendue faute de relais.

C’était le seul prix Nobel d’économie français. Né le 31 mai 1911, il part aux États-Unis dès sa sortie (major X31) de Polytechnique en 1933 pour étudier in situ la Grande Dépression qui a suivi la Crise de 1929. Ironie de l’histoire, il a ainsi pu réaliser une sorte de “jonction” entre les deux Crises majeures du siècle. Son analyse, percutante et dérangeante, n’a malheureusement pas été entendue faute de relais.

« Cette doctrine [la « chienlit mondialiste laissez-fairiste »] a été littéralement imposée aux gouvernements américains successifs, puis au monde entier, par les multinationales américaines, et à leur suite par les multinationales dans toutes les parties du monde, qui en fait détiennent partout en raison de leur considérable pouvoir financier et par personnes interposées la plus grande partie du pouvoir politique. La mondialisation, on ne saurait trop le souligner,

« Cette doctrine [la « chienlit mondialiste laissez-fairiste »] a été littéralement imposée aux gouvernements américains successifs, puis au monde entier, par les multinationales américaines, et à leur suite par les multinationales dans toutes les parties du monde, qui en fait détiennent partout en raison de leur considérable pouvoir financier et par personnes interposées la plus grande partie du pouvoir politique. La mondialisation, on ne saurait trop le souligner,

Über die

Über die  Jenseits dieser privaten Partydauerstimmung, in der man die eigene Vita der Amüsementsteigerung widmet, weiß der Deutsche von heute aber sehr genau, wo und auf welche Schlüsselworte hin er auf Moll umzuschalten hat: beim Befassen mit dem Düsterdeutschland der Jahre vor Neunzehnhundert-Sie-wissen-schon. Gerät man auf diesem kontaminierten Gelände auch nur unter Verdacht, die geschichtspolitischen Dogmen nicht hinreichend verinnerlicht zu haben oder offenbart man gar Ermüdungserscheinungen bei dem Distanzierungsvolkssport Nummer eins, dem Einprügeln auf die herrlich toten »Nazis«, darf man sich nicht wundern, wenn man eines schönen Tages als »Rechtsextremist« o.ä. aufwacht. Diesem Umstand ist es zu verdanken, daß sich zwischenzeitlich die meisten NS-Forschungsfelder in politisch-psychologische »No-go-areas« verwandelt haben, in denen nicht Erkenntnisdrang, sondern penetranter Dogmatismus den (Buß-)Gang der Dinge bestimmt.

Jenseits dieser privaten Partydauerstimmung, in der man die eigene Vita der Amüsementsteigerung widmet, weiß der Deutsche von heute aber sehr genau, wo und auf welche Schlüsselworte hin er auf Moll umzuschalten hat: beim Befassen mit dem Düsterdeutschland der Jahre vor Neunzehnhundert-Sie-wissen-schon. Gerät man auf diesem kontaminierten Gelände auch nur unter Verdacht, die geschichtspolitischen Dogmen nicht hinreichend verinnerlicht zu haben oder offenbart man gar Ermüdungserscheinungen bei dem Distanzierungsvolkssport Nummer eins, dem Einprügeln auf die herrlich toten »Nazis«, darf man sich nicht wundern, wenn man eines schönen Tages als »Rechtsextremist« o.ä. aufwacht. Diesem Umstand ist es zu verdanken, daß sich zwischenzeitlich die meisten NS-Forschungsfelder in politisch-psychologische »No-go-areas« verwandelt haben, in denen nicht Erkenntnisdrang, sondern penetranter Dogmatismus den (Buß-)Gang der Dinge bestimmt. Wer als junger Deutscher zu einem solch aberwitzigen »mourir pour Auschwitz« nicht bereit ist, wird gnadenlos mit der »Hitler-Scheiße« (Martin Walser) zugedeckt und läuft Gefahr, als »Heide der Gedenkreligion des Holokaust« (Peter Furth) über Nacht seine sozialen Beziehungen zu verlieren. Denn wer ein Tabu übertreten hat, wissen wir seit Freud, wird selbst tabu. Die dazu erforderliche braune Lava wurde und wird von den Niemöllers, Eschenburgs, Wehlers, Benz’, Knopps e tutti quanti seit Jahrzehnten am Blubbern gehalten. Ein Solitär wie Nolte, der – ganz ohne den Mundgeruch der Bewältigungstechnokraten – die historischen Abläufe 1917ff. nüchtern und mit luziden Zwischentönen analysiert, könnte bei diesem Simplifizierungsgeschäft nur stören.

Wer als junger Deutscher zu einem solch aberwitzigen »mourir pour Auschwitz« nicht bereit ist, wird gnadenlos mit der »Hitler-Scheiße« (Martin Walser) zugedeckt und läuft Gefahr, als »Heide der Gedenkreligion des Holokaust« (Peter Furth) über Nacht seine sozialen Beziehungen zu verlieren. Denn wer ein Tabu übertreten hat, wissen wir seit Freud, wird selbst tabu. Die dazu erforderliche braune Lava wurde und wird von den Niemöllers, Eschenburgs, Wehlers, Benz’, Knopps e tutti quanti seit Jahrzehnten am Blubbern gehalten. Ein Solitär wie Nolte, der – ganz ohne den Mundgeruch der Bewältigungstechnokraten – die historischen Abläufe 1917ff. nüchtern und mit luziden Zwischentönen analysiert, könnte bei diesem Simplifizierungsgeschäft nur stören.