Edelweiss

The Archaeo-Futurist European Imperial Idea in Robert Steuckers’ Europa I. Valeurs et racines profonds de l’Europe

(Madrid: BIOS, 2017)

by Alexander Wolfheze

Prologue: Wormtongue in Zürich

For the Brussels regime of globalist eurocrats the upcoming European elections obviously represent an opportunity to fit itself with a new set of ‘democratic clothes’, but it also offers the patriotic-identitarian resistance an opportunity to revisit its critique of the ‘EU project’. At this point, the camouflage cover of EU emperorship has become so threadbare that even its heir-apparent Mark Rutte openly wonders if the time has not come to switch from outdated democratic outfits to updated totalitarian styles. In this regard, the title of his Zürich ‘Churchill Lecture’ of 13 February 2019 - interpreted as yet another ‘job application’ by many political analysts - leaves little room for doubt: ‘The EU: from the power of principles towards principles and power’. Despite the grammatical ambiguity, the ‘semantic switch’ is clear for all to see: the ‘power principle’ is now foremost in the minds of the eurocratic elite. For the EU needs a reality check; power is not a dirty word read: ‘the EU should use its instruments of power’. For the importance of being less naïve and more realistic read: ‘it is time to end the idealistic charade’. For The requirement of unanimity reflects the fact that foreign policy is part of the core of national sovereignty... But when it comes to sanctions, I do think that we must give serious thought to enabling qualified majority voting for specific, defined cases read: ‘the remaining state sovereignty of the member states should be diminished even further’. In fact, the transformation of the EU into a ‘super state’ is already a palpable reality: the steady accumulation of censorship in the (social) media and digital sphere, through ‘hate speech codes’,[1] ‘fake news taskforces’[2] and ‘copyright directives’,[3] is approaching the level of Orwellian perfection. As the totalitarian finish line of the EU project is coming into view, it is important to re-view its historical genesis and ideological baseline.

For the Brussels regime of globalist eurocrats the upcoming European elections obviously represent an opportunity to fit itself with a new set of ‘democratic clothes’, but it also offers the patriotic-identitarian resistance an opportunity to revisit its critique of the ‘EU project’. At this point, the camouflage cover of EU emperorship has become so threadbare that even its heir-apparent Mark Rutte openly wonders if the time has not come to switch from outdated democratic outfits to updated totalitarian styles. In this regard, the title of his Zürich ‘Churchill Lecture’ of 13 February 2019 - interpreted as yet another ‘job application’ by many political analysts - leaves little room for doubt: ‘The EU: from the power of principles towards principles and power’. Despite the grammatical ambiguity, the ‘semantic switch’ is clear for all to see: the ‘power principle’ is now foremost in the minds of the eurocratic elite. For the EU needs a reality check; power is not a dirty word read: ‘the EU should use its instruments of power’. For the importance of being less naïve and more realistic read: ‘it is time to end the idealistic charade’. For The requirement of unanimity reflects the fact that foreign policy is part of the core of national sovereignty... But when it comes to sanctions, I do think that we must give serious thought to enabling qualified majority voting for specific, defined cases read: ‘the remaining state sovereignty of the member states should be diminished even further’. In fact, the transformation of the EU into a ‘super state’ is already a palpable reality: the steady accumulation of censorship in the (social) media and digital sphere, through ‘hate speech codes’,[1] ‘fake news taskforces’[2] and ‘copyright directives’,[3] is approaching the level of Orwellian perfection. As the totalitarian finish line of the EU project is coming into view, it is important to re-view its historical genesis and ideological baseline.

The Maastricht Treaty that laid the formal groundwork for the present-day European Union was signed on 7 February 1992, only six weeks after the formal dissolution of the Soviet Union. Thus, the construction of the new cultural-marxist Western Bloc commenced almost immediately after the demolition of the old real-socialist Eastern Bloc. Since then, the EU was not only enlarged externally (most substantially through the hasty absorption of the Central European nation-states that had just freed themselves from Eastern Bloc rule) - it was also transformed internally, rapidly developing into a proto-totalitarian ‘super state’ project and a worthy successor to the Soviet Union. In a number of ways, the similarities are increasingly startling. The same social ‘deconstruction’ - Eastern Bloc: hyper-proletarian collectivism / Western Bloc: neo-matriarchal levelling. The same economic ‘deconstruction’ - Eastern Bloc: ‘forced collectivization’ / Western Bloc: ‘disaster capitalism’. The same ethnic ‘deconstruction’ - Eastern Bloc: ‘group deportation’ / Western Bloc: Umvolkung. In the contemporary West, the discrepancy between the theoretical discourse of the rulers and the practical lived reality of the people is approaching the same grotesque ‘doublethink’ level as it reached in the Eastern Bloc. The ideological doctrine of Western liberal-normativism theoretically upholds ‘freedom’, ‘equality’, ‘democracy’, ‘justice’ and ‘human rights’, but its real-time practice of nihilist deconstruction provides only social-darwinist economic jungle law, perverse social implosion, pervasive institutional corruption, failing law enforcement and wholesale ethnic replacement. In a certain sense, the Western Bloc has already surpassed Eastern Bloc totalitarianism: in all EU member states the EU flag is everywhere displayed right next to the national flag - a direct insult to national dignity that even the formally independent Soviet satellite states were spared.

Given this escalating discrepancy between theory and practice, the ruling class of the Western Bloc - a globalistically-eurocratically operating coalition between neo-liberal high finance and cultural-marxist intelligentsia - has been transformed into a hostile elite in the true sense of the word. Its EU project has been shown for what it truly constitutes: a globalist anti-Europe project. If European civilization, and the indigenous peoples of Europe that are the bearers of this civilization are to survive, the removal of the hostile elite must have absolute priority. In working towards this end, a fundamental (cultural-historical, political-philosophical) critique of its ideology is of crucial importance for the patriotic-identitarian resistance. An important contribution to this critique has recently been made by Belgian Traditionalist publicist Robert Steuckers: a better ‘guide’ to the issues at stake in the upcoming ‘European elections’ of May 2019 than his great trilogy Europa is hardly imaginable. This present essay aims at making Steuckers’ analysis of Europe’s authentic core values and identitarian roots, found in Part I of Europa but written in French and not yet translated, available to a wider English-speaking audience. Part I of Europa offers more than a thorough counter-analysis of the postmodern ‘deconstruction’ of Europe’s authentic values and identities: it offers a clear formulation of a viable alternative: an Archaeo-Futuristically inspired ‘Europe of the Peoples’, based on the complementary principles of autonomous ethnic communities, consistently-applied political subsidiarity and pragmatic confederative structures. It ought to be said once more: the Western patriotic-identitarian movement owes Robert Steuckers a great debt of gratitude for his tireless educational work. Above and beyond this, the patriotic-identitarian movement of the Low Countries congratulates him on rising above the usual intellectual mediocrity of our ‘lowlands’ - and reminding Europe of the fact that even in our backwaters thought is being given to the possible shape of a new Europe of the Peoples.

(*) As in the case of the preceding ‘Steuckers reviews’,[4] this essay is not only meant as a review: it also serves as a meta-political analysis in its own right - a contribution to the patriotic-identitarian counter-deconstruction of the postmodern deconstruction discourse of the Western hostile elite. The core of this essay provides a summary of Steuckers’ Traditionalist exploration of European identity. This exploration puts a full stop behind the postmodern deconstruction of that identity and provides a cultural-historical tabula rasa that allows the patriotic-identitarian movement to give an entirely new and revolutionary meaning to the idea that is ‘Europe’. In an intellectual sense, an Archaeo-Futurist Europe is now effectively within reach.

(**) This essay treats the ‘European case’ in three steps: the first paragraph triad offers base-line ‘diagnostics’, the second paragraph triad offers ‘therapeutic’ reference points and the seventh paragraph suggests avenues for a concrete ‘treatment’. In the first and last paragraphs, the reviewer gives an outline of the larger Archaeo-Futurist context within which Steuckers’ exploration of European identity becomes relevant for the patriotic-identitarian movement - the actual ‘review’ of Steuckers’ Europa I is found in paragraphs 2 through 6.

(***) For an explanation of the chosen linguistic form and note format the reader is referred to the prologues of the preceding ‘Steuckers reviews’.

1.

The Red Weed

(psycho-historical diagnosis)

‘Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow’[5]

Till today, H.G. Wells’ masterpiece The War of the Worlds not only remains one of the greatest works of the entire literary science fiction genre: till today, this evergreen also retains a direct - albeit mostly unconsciously and instinctively recognized - relevance to the existential condition of Western civilization.[6] Wells’ masterful impressionist rendering of ‘Earth under the Martians’ sketches a world where mankind has lost its bearings - where all recognition and reference points have been wiped away. As human civilization is destroyed by superior alien technology, alien occupation reduces mankind itself to cattle for the slaughter - even earthly nature itself is displaced by alien vegetation. Thus a (literally) creepy ‘red weed’ - a reference to the red colour of ‘war planet’ Mars - grows over the ruins of human civilization, suffocating the remnants of earthly vegetation.[7] Literary analyses of The War of the Worlds recognize that Wells’ masterpiece can be plausibly interpreted as a series of retrospective and contextual psycho-historical ‘mirror images’. Thus, Wells projects the imperialistically rationalized and social-darwinistically justified genocide of ‘primitive peoples’ (such as the indigenous people of Tasmania)[8] by the ‘white master race’ throughout the modern era on the hypothetical extermination of humanity by a superior alien race. He also projects the dehumanizing horror of the rising ‘bio-industry’ of his time on humanity’s hypothetical ‘cattle status’ under alien dominion. Most literary analyses, however, stop of short of pointing to the predictive value of Wells’ work - a value that derives from its forward projection of multiple and simultaneous occurring technological and sociological developmental trajectories. Earlier times would undoubtedly have been recognized Wells’ genius literary packaging of these projections as straightforward ‘prophecy’ – our own time must make do with ‘scientific fiction’.

Till today, H.G. Wells’ masterpiece The War of the Worlds not only remains one of the greatest works of the entire literary science fiction genre: till today, this evergreen also retains a direct - albeit mostly unconsciously and instinctively recognized - relevance to the existential condition of Western civilization.[6] Wells’ masterful impressionist rendering of ‘Earth under the Martians’ sketches a world where mankind has lost its bearings - where all recognition and reference points have been wiped away. As human civilization is destroyed by superior alien technology, alien occupation reduces mankind itself to cattle for the slaughter - even earthly nature itself is displaced by alien vegetation. Thus a (literally) creepy ‘red weed’ - a reference to the red colour of ‘war planet’ Mars - grows over the ruins of human civilization, suffocating the remnants of earthly vegetation.[7] Literary analyses of The War of the Worlds recognize that Wells’ masterpiece can be plausibly interpreted as a series of retrospective and contextual psycho-historical ‘mirror images’. Thus, Wells projects the imperialistically rationalized and social-darwinistically justified genocide of ‘primitive peoples’ (such as the indigenous people of Tasmania)[8] by the ‘white master race’ throughout the modern era on the hypothetical extermination of humanity by a superior alien race. He also projects the dehumanizing horror of the rising ‘bio-industry’ of his time on humanity’s hypothetical ‘cattle status’ under alien dominion. Most literary analyses, however, stop of short of pointing to the predictive value of Wells’ work - a value that derives from its forward projection of multiple and simultaneous occurring technological and sociological developmental trajectories. Earlier times would undoubtedly have been recognized Wells’ genius literary packaging of these projections as straightforward ‘prophecy’ – our own time must make do with ‘scientific fiction’.

The existential stress fractures that Modernity has caused in Western civilization can be analyzed - and partially projected forward - by means of modern scientific models: economically as Entfremdung (Karl Marx), sociologically as anomie (Emile Durkheim), psychologically as cognitive dissonance (Leon Festinger) and philosophically as Seinsvergessenheit (Martin Heidegger). For the Western patriotic-identitarian movement the meta-political relevance of these analyses does not primarily reside in their - sometimes ideologically biased - ‘deconstructive’ capacity, but rather in their simple diagnostic value. In this respect, there exists an important similarity between such modern scientific models and modern artistic ‘models’ such as Wells’ The War of the Worlds: by interpreting societal develops as ‘omens’ they can provide societal ‘traffic signs’ - and existential ‘warning signs’. By now, the accumulative impact of Modernity on Western societies is so great that the existential condition of the Western peoples can no longer be described in terms of authentic civilizational continuities or historical ‘standard settings’. When deviation, aberration and derailment determine an entire existential condition, then historically recognizable ‘standards’ are obsolete. When scientifically formulated ‘traffic signs’ are ignored for long enough, then artistically ‘predicted’ dystopian abysses must be faced. It is not by chance that the current phase op (ex-)Western cultural history is described by the term ‘post-modern’: the (ex-)Western societies of today have largely left behind authentic civilizational continuity and they are now moving with increasing speed in the direction of existential conditions that bare an uncanny resemblance to those that prevailed in Wells’ vision of Earth under the Martians.

The new ‘globalist’ ruling class of the West has effectively separated itself from the Western peoples - and positioned itself above it. Now, its only ‘connection’ to these peoples is found in the impact of its power. The hostile elite now considers itself superior to the ‘masses’ that it has ‘outgrown’ in a sense that is not merely ethical and aesthetical: it considers itself evolutionarily superior - it has become alienated in the most literal sense of the word.[9] The consistently negative effects of the hostile elite’s exercise of power - felt most particularly in neo-liberal exploitation, industrial ecocide, bio-industrial animal cruelty, cultural-marxist deconstruction, social implosion, ethnic replacement - define its role as a literally hostile elite. It does not know empathy and sympathy in any way, shape or form: not for its Western enemies, not for its Third World servants and not for its home planet - it is now literally alien to the Earth itself. The globalists are at war with humanity as a whole. They seek to eliminate or enslave at will. They care about themselves and themselves alone. They are committed to concentrating all wealth in their hideous hands. In their evil eyes, our only purpose is to serve them and enrich them. Hence, there is no room for racism, prejudice, and discrimination in this struggle. It is not a race war but a war for the human race, all included, a socio-political and economic war of planetary proportions (Jean-François Paradis).[10]

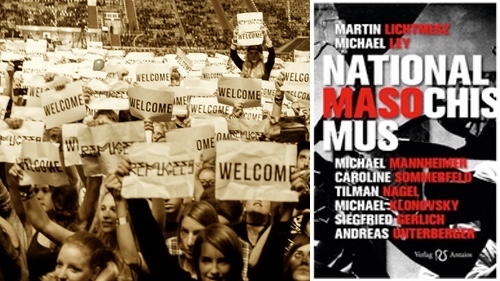

The globalist - and therefore anti-European - geopolitical strategy of the hostile elite (which aims at industrial delocalization, social atomization and cultural deracination, cf. Steuckers 223ff.) may be recognized as social-economic and psycho-social warfare by a handful of patriotic-identitarian thinkers, but the Western masses only recognize its effects: economic marginalization (labour market manipulation, artificial unemployment, interethnic wealth redistribution), social malaise (matriarchal anti-law, family structure disruption, digital pornification) and cultural decadence (educational ‘idiocracy’, academic ‘valorization’, media ‘political-correctness’). Through a carefully calibrated - but now critically dosed - process of mass immigration, the hostile elite is constantly reinforcing these economic, social and cultural ‘deconstruction’ programs, to the point of irreversibility. The Umvolkung process aims at eradicating the Western peoples as ethnically, historically and culturally distinct entities by ‘dissolving’ them in an atomized mass of atomized déracinés - by stamping them down into la boue,[11] the ‘mud’ of identity-less, character-less and will-less ‘mass man’. This process of ethno-cultural, social-economic and psycho-social total levelling, for now directed primarily at Europe, aims at the ultimate Endlösung of the core problem of the New World Order, which is the continued existence of authentic - and therefore automatically anti-globalist - identities at the collective level. Most concretely, this Endlösung is realized through the totalitarian implementation of ethnocidal ‘multiculturality’ and anti-identitarian ‘mobocracy’.

The motivations and aims of the hostile elite effectively ‘surpass’ the imagination of the Western masses - in certain respects, they even ‘surpass’ the common categories of human thought. In fact, their ‘un-earthly’ and ‘diabolical’ quality is starting to become increasingly evident in its concrete effects.[12] Elsewhere, the ideology of the hostile elite was defined as ‘Culture Nihilism’, i.e. as an improvised amalgam of ideas characterized by militant secularism, social-darwinist hyper-individualism, collectively internalized narcissism and doctrinal culture-relativism aimed at the destruction of all authentic forms of Western civilization.[13] The fact that the Western masses are not able to grasp Cultural Nihilism as an ideology and a program is largely due to its deliberate ‘vagueness’: the explicit motivations and aims of the hostile elite are intentionally il-logical and anti-rational. The only thing that is important for the hostile elite is power: its so-called ‘ideas’ are mere stratagems to gain, retain and expand power: they should be understood as ‘frames’ that serve specific purposes in cognitive warfare.

A good example of this cognitive warfare can be found in the currently fashionable ‘climate debate’: the ‘party (cartel) line’ that has been laid out by the hostile elite makes an appeal to Gutmensch eco-consciousness, but the punitive tribute that is imposed on the masses by means of new ‘climate taxes’ is exclusively used for ‘investment’ in commercial ‘climate business’ - and to subsidize politically-correct ‘climate clubs’. The inevitable popular backlash is then cognitively ‘transposed’ into a sub-rational ‘climate denial’ discourse that is projected on - even pragmatically claimed by - the ‘populist’ opposition, either in activism (the French ‘yellow vests’) or in parliament (the ‘0,00007 degrees centigrade’ slogan of the Dutch Forum for Democracy party). In this case, the cognitive dissonance that has been successfully created by the hostile elite runs so deep that the ‘common man in the street’ is actually denying the reality of vanishing winter ice and absurd February springs seasons to himself. The balancing act of the hostile elite is entirely effective: the ‘populist opposition’ is happy to abandon the moral high ground for the sake of a few extra parliamentary seats, the masses are happy because they can continue their ‘dance on the volcano’ with some extra years of holiday flights and automobile kilometres and the hostile elite is happy to continue in its ‘economic growth’ model - and with the extra ‘climate taxes’ that can be fed into ‘commercial investments’ and, of course, ‘climate refugees’. In the meantime, ‘business as usual’, or actually more than usual, means that the ecocidal clock of anthropogenic global warming and meteorological catastrophes is left to run its course - to the ‘final countdown’.

A good example of this cognitive warfare can be found in the currently fashionable ‘climate debate’: the ‘party (cartel) line’ that has been laid out by the hostile elite makes an appeal to Gutmensch eco-consciousness, but the punitive tribute that is imposed on the masses by means of new ‘climate taxes’ is exclusively used for ‘investment’ in commercial ‘climate business’ - and to subsidize politically-correct ‘climate clubs’. The inevitable popular backlash is then cognitively ‘transposed’ into a sub-rational ‘climate denial’ discourse that is projected on - even pragmatically claimed by - the ‘populist’ opposition, either in activism (the French ‘yellow vests’) or in parliament (the ‘0,00007 degrees centigrade’ slogan of the Dutch Forum for Democracy party). In this case, the cognitive dissonance that has been successfully created by the hostile elite runs so deep that the ‘common man in the street’ is actually denying the reality of vanishing winter ice and absurd February springs seasons to himself. The balancing act of the hostile elite is entirely effective: the ‘populist opposition’ is happy to abandon the moral high ground for the sake of a few extra parliamentary seats, the masses are happy because they can continue their ‘dance on the volcano’ with some extra years of holiday flights and automobile kilometres and the hostile elite is happy to continue in its ‘economic growth’ model - and with the extra ‘climate taxes’ that can be fed into ‘commercial investments’ and, of course, ‘climate refugees’. In the meantime, ‘business as usual’, or actually more than usual, means that the ecocidal clock of anthropogenic global warming and meteorological catastrophes is left to run its course - to the ‘final countdown’.

On balance, however, the Western masses do instinctively recognize the globalist megalomania of the hostile elite - the elite intelligentsia dismisses this instinctive recognition as ‘belly feel’ and it disqualifies its political expression as ‘populism’. This extreme demophobic arrogance may long retain its effectiveness, but in the longest run, it will come at a heavy price: even now, the Western peoples are beginning to experience the globalist regime of the hostile elite as an ‘alien occupation’. The masses are slowly by slowly starting to see the all-suffocating power of the hostile elite for what it is: an alien ‘red weed’ that is literally smothering Western civilization and the Western homeland.

I had not realised what had been happening to the world, had not anticipated this startling vision of unfamiliar things. I had expected to see... ruins - I found about me the landscape, weird and lurid, of another planet. For that moment I touched an emotion beyond the common range of men, yet one that the poor brutes we dominate know only too well. I felt as a rabbit might feel returning to his burrow and suddenly confronted by the work of a dozen busy navvies digging the foundations of a house. I felt the first inkling of a thing that presently grew quite clear in my mind, that oppressed me for many days, a sense of dethronement, a persuasion that I was no longer a master, but an animal among the animals, under [alien rule]. With us it would be as with them, to lurk and watch, to run and hide; the fear and empire of man had passed away. - Herbert George Wells, The War of the Worlds

2.

The European Kata-morphosis

(political-philosophical diagnosis)

Impia tortorum long[o]s hic turba furores sanguinis innocui, non satiata, aluit.

Sospite nunc patria, fracto nunc funeris antro, mors ubi dira fuit,

vita salusque patent.

[Here an impious mob of torturers, insatiable,

fed their long-lasting frenzies for innocent blood.

Now that the fatherland is safe, now that the cave of murder has been destroyed,

in the place where foul death once was,

life and health are open to all.][14]

After half a century of systematic demolition work on state structures and ethnic identities, Europe’s political, economic, social and cultural landscape has changed beyond recognition. The decades’ long outgrowths of parasitical neo-liberalism and prolific cultural-marxism have covered Europe as a ‘red weed’, creating previously unimaginable societal deformations. Hyper-mobile ‘flash capital’ is causing short-lived economic bubbles that give rise to architectural, artistic and fashion monstrosities, spreading outwards from ‘central business districts’, ‘leisure time resorts’ and ‘academic campus environments’. Ethnic ‘diversity’ is resulting in social-economic networks that are smothering the Western public sphere as so many ‘invasive species’: diaspora economies, drug mafias and polycriminal subcultures. These networks are supplemented by un-Western ‘spirit-based’ institutions: the awqāf[15] sponsored by Middle Eastern oil capital, the ‘asylum industry’ funded by public taxes and the ‘system media’ managed by globalist capital. What effectively links all these networks and institutions, systematically tolerated and facilitated by the hostile elite, is their common functionality, viz. their role as replacement mechanisms that are laying the groundwork for the New World Order. In this regard, a crucial role is reserved for the schwebende Intelligenz, viz. cultural-marxist intelligentsia that constitutes the globalist avant-garde. This intelligentsia is tasked with the supra-spatial and im-material deconstruction that precedes the spatial and material deconstruction of Western civilization. These ‘spiritual’ and ‘intellectual’ representatives of the globalist occupation regime ...se nichent dans [l]es trois milieux-clefs - média, économie, enseignement - et participent à la élimination graduelle mais certaines des assises idéologiques, des fondements spirituels et éthiques de notre civilisation. Les uns oblitèrent les résidus désormais épars de ces fondements en diffusant une culture de variétés sans profondeur aucune, les autres en décentrant l’économie et en l’éclatant littéralement par les pratiques de la spéculation et de la délocalisation, les troisièmes, en refusant l’idéal pédagogique de la transmission, laquelle est désormais interprétée comme une pratique anachronique et autoritaire, ce qu’elle n’est certainement pas au sens péjoratif que ces termes ont acquis dans le sillage de Mai 68. [...have settled in [the] three key positions [of globalist power] - media, economy [and] education - and there they work towards the slow but sure elimination of the ideological, spiritual and ethical foundations of our civilization. Some of them are engaged in the erasure of the already crumbling foundational remnants by disseminating superficial ‘cultural diversity’. Others [are engaged in] the ‘decentralization’ of the economy by literally blowing it up through speculation and delocalization. Yet others [are engaged in] the sabotage of the pedagogical ideal of [cultural] transmission by representing [that ideal] as an ‘outdated’ and ‘authoritarian’ practice on the basis of the negative connotation that these terms were charged with in the aftermath of May ’68.] (p. 262-3)

The globalist intelligentsia is using refined ‘alien audience’ propaganda strategies and coordinates the cognitive warfare that the hostile elite is waging against the Western peoples: it is creating a liberal-normative habitus of exclusively ‘economic thought’ that justifies the physical deconstruction of Western civilization. ...[U]ne économie ne peut pas, sans danger, refuser par principe de tenir compte des autres domaines de l’activité humaine. L’héritage culturel, l’organisation de la médecine et de l’enseignement doivent toujours recevoir une priorité par rapport aux facteurs purement économiques, parce qu’ils procurent ordre et stabilité au sein d’une société donnée ou d’une aire civilisationnelle, garantissant du même coup l’avenir des peuples qui vivent dans cet espace de civilisation. Sans une telle stabilité, les peuples périssent littéralement d’un excès de libéralisme, ou d’économicisme ou de ‘commercialité’... [An econom[ic model] cannot refuse to take account of other spheres of human activity with impunity. The cultural sphere, the healthcare sphere and the educational sphere must always be prioritized above merely economic factors because they provide order and stability to a given community or civilization. They are the guarantors of the future of the peoples living within that civilization. Without such stability, the[se] peoples will literally die of an overdose of ‘liberalism’, ‘economism’ and ‘commercialism’...] (p. 216-7)

In the European context, the doubly neo-liberal and cultural-marxist deconstruction of Western civilization and peoples is implemented through the Brussels-based ‘EU project’. This project is characterized by a radical departure from all traditional notions of pan-European cooperation: in a meta-historical sense, the postmodern ‘EU project’ represents a structural inversion of the classical concept of the European empire. L’Europe actuelle, qui a pris la forme de l’eurocratie bruxelloise, n’est évidemment pas un empire, mais, au contraire, un super-état en devenir. La notion d’‘état’ n’a rien à voir avec la notion d’‘empire’, car un ‘état’ est ‘statique’ et ne se meut pas, tandis que, par définition, un empire englobe en son sein toutes les formes organiques de l’aire civilisationnelle qu’il organise, les transforme et les adapte sur les plans spirituel et politique, ce qui implique qu’il est en permanence en effervescence et en mouvement. L’eurocratie bruxelloise conduira, si elle persiste dans ses errements, à une rigidification totale. L’actuelle eurocratie bruxelloise n’a pas de mémoire, refuse d’en avoir une, a perdu toute assise historique, se pose comme sans racines. L’idéologie de cette construction de type ‘machine’ relève du pur bricolage idéologique, d’un bricolage qui refuse de tirer des leçons des expériences du passé. Cela implique une négation de la dimension historique des systèmes économiques réellement existants, qui ont effectivement émergé et se sont développés sur le sol européen. [Contemporary ‘Europe’, as given shape by the Brussels ‘eurocrats’, is clearly not an empire - it represents its opposite: a superstate-in-the-making. The notion of the ‘state’ is essentially different from the notion of the ‘empire’: the ‘state’ is [literally] ‘static’ and [essentially] immovable, whereas the ‘empire’ is [always in a state of flux as it is] engaged in the [constant] absorption of the organic forms that come within its reach, re-shaping and re-adapting them in accordance with its spiritual and political precepts. [T]hus, [the empire] is a constant state of fermentation and movement. If the Brussels eurocracy continues on its current path, which is leading [in the opposite direction and] towards a dead end, then it will end up in a state of total ‘fossilization’. In its current form, the Brussels eurocracy lacks - and refuses - [any kind of historical] memory and it resists [any kind of historical] rootedness. [Its radically] constructivist and mechanical self-image is based on an ideological improvisation that refuses to learn from the lessons and experiences of [European] history. This involves a denial of the historical dimension of the [specific national] real-life economic systems that have [organically] sprung up from the soil of Europe.] (p. 215-6)

From a political-philosophical perspective, the deeply anti-European ‘EU project’ represents no less than a globalist Machtergreifung. Neo-Jacobin radicals have taken over the reins of power and the historical precedents for Jacobin power experiments[16] - as in French and Russian revolutionary terror - should set off alarm bells all over Europe. But knowledge of the European historical context of the ‘EU project’, by itself, is insufficient for a thorough understanding of its ostensibly contradictory - because self-destructive - anti-European aims. Such an understanding requires insight into the larger aims of globalism - in his Europa trilogy, Steuckers now provides that insight in a lucid and concise manner.

3.

Globalist Anti-Europe Project

(geo-political diagnosis)

Sometimes the crime that one is about to commit is so terrible

that to commit it on behalf nation is not enough

- one needs to commit it on behalf of humanity.

- Nicolás Gómez Dávila

Steuckers’ panoramic overview of the contemporary global geopolitical landscape proceeds from the notion that the anti-European ‘EU project’ can only be properly understood as the result of the Second World War. That conflict ended the great power status and imperial hegemony of the European nation-states: the military defeat of France (1940), Italy (1943) and Germany (1945) was followed by the liquidation of European colonial empires (British India in 1947, the Dutch East Indies in 1949, Belgian Congo in 1960, French Algeria in 1962 and Portuguese Africa in 1975). In a few short years, world rule shifted to two superpowers that were guided by universalist ideologies and globalist geopolitics: the United States as the champion of Liberalism and the Soviet Union as the champion of Socialism. The physical (geographic, demographic, industrial) assets of defeated Europe was divided between the victors through military treaties (NATO, Warsaw Pact) and economic structures (EEC, Comecon). It is important to remember these brutal realities of military defeat, colonial liquidation and political tutelage. La Seconde Guerre mondiale avait pour objectif principal, selon Roosevelt et Churchill, d’empêcher l’unification européenne sous la férule des puissances d’Axe, afin d’éviter l’émergence d’une économie ‘impénétrée’ et ‘impénétrable’, capable de s’affirmer sur la scène mondiale. La Second Guerre mondiale n’avait donc pas pour but de ‘libérer’ l’Europe mais de précipiter définitivement l’économie de notre continent dans un état de dépendance et de l’y maintenir. Je n’énonce donc pas un jugement ‘moral’ sur les responsabilités de la guerre, mais je juge son déclenchement au départ de critères matériels et économiques objectifs. Nos médias omettent de citer encore quelques buts de guerre, pourtant clairement affirmés à l’époque, ce qui ne doit surtout pas nous induire à penser qu’ils étaient insignifiants. [For Roosevelt and Churchill the main aim of the Second World War was to prevent of the unification of Europe under the Axis powers, which would have given rise to a [European] economy that would have been ‘impenetrable’ and ‘invincible’ as an independent force on the world stage. Thus, [their true] aim in fighting the Second World War was not the ‘liberation’ of Europe, but [merely] the reduction of [Europe’s] continental economy to a state of permanent dependence. This statement does not reflect any pronouncement on the ‘moral’ responsibility for that war - it merely reflects the objective material and economic goals [that shaped it]. The fact that [the system] media are [carefully] avoiding any mention of [those] other goals, [goals] that were clearly pronounced at the time, does not mean that they were unimportant.] (p.220)

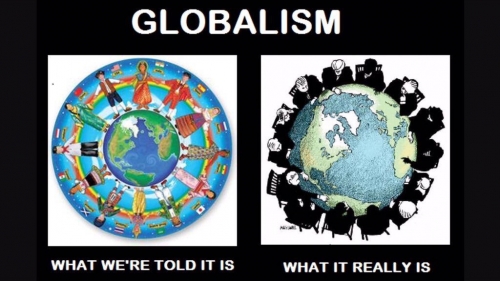

In the mid-‘80s, after four decades of Cold War, the first stress fractures started to appear the globally operating power structures of the two superpowers. The Challenger and Chernobyl disasters (respectively, 28 January and 26 April 1986) clearly illustrated the fact that the symptoms of ‘imperial overstretch’ could no longer be hidden from public view. Escalating economic chaos and increasing loss of political credibility forced both superpowers into radical domestic reforms: Reaganomics and Perestroika represent the superpowers’ geopolitical high water mark. After the implosion of the Soviet Union, the United States formally comes out ‘on top’, but the Pyrrhic quality of America’s Cold War ‘victory’ soon becomes undeniable: it immediately ‘rolls over’ when China transforms itself into an economic superpower and it soon retreats from the Third World, which had been the prime battlefield of the Cold War just a few years before. After the American defeat in Somalia (Black Hawk Down, 1993), Africa is allowed to collapse into ‘failed states’ and neo-tribal chaos. After the American retreat from Panama (Canal Zone Handover, 1999), Latin America is left to Bolivarianismo and the Marea Rosa.[17] The imperialist ‘rat race’ between sovereign nation-states that started with the ‘World War Zero’ Seven Years War (1756-63) may have ended with America as ‘last man standing’, but the enforcement of an authentically imperial Pax America is far beyond the scope of America’s geopolitical intent, ambition and capacity. Thus, despite the overt Wilsonian rhetoric that surrounded America’s interventions in Iraq (Bush Senior in 1991 and Bush Junior in 2003), these do not represent exercises in principled ‘global governance’ - rather, they simply represent attempts at pragmatic resource control. After the self-abolition of the Soviet Union as a superpower contender and after the official announcement of a ‘New World Order’ (Bush Senior, 1991), the American ruling class decided that the ‘End of History’ (Francis Fukuyama, 1992) had come: it decided to switch from Americanism to globalism. Thus, it deliberately transformed itself into a ‘world elite’, now accessible to anybody with very much money and very little morality. This new world elite considers itself entirely exempt from the old rules and laws of geopolitics: from its perspective, national sovereignty, cultural uniqueness and ethnic identity are hopelessly outdated phenomena that merely stand in the way of its ‘Brave New World’. As a group, this new ‘globalist’ elite has cut itself off from all ethnic, religious and cultural roots: on the basis of this self-willed rootlessness it turns against the rest of mankind, to the extent that the rest still possesses roots: against states that still possess sovereign rights, against cultures that still possess authentic essences and against peoples that still possess substantial identities. The globalist hostile elite is born.

Under the double banners of neo-liberalism and cultural-marxism, the hostile elite regards the ‘backward’ residue of humanity as little more than a mass of infinitely malleable ‘human material’ that it can use to fill its bank accounts, to serve its sexual perversities and to compensate for its existential crises. [La superclasse... domine à l’ère idéologique du néoliberalisme. Il n’est pas aisé de la définir : elle comporte évidemment les managers des grandes entreprises mondiales, les directeurs des grandes banques, de cheiks du pétrole ou des décideurs politiques voire quelques vedettes du cinéma ou de la littérature ou encore, en coulisses, des leaders religieux et des narcotrafiquants, qui alimentent le secteur bancaire en argent sale. Cette superclasse n’est pas stable : on y appartient pendant quelques années ou pendant une ou deux décennies puis on en sort, avec, un bon ‘parachute doré’. ...[N]umériquement insignifiante mais bien plus puissante que les anciennes aristocraties ou partitocraties, elle est totalement coupée des masses, dont elle détermine le destin. En dépit de tous les discours démocratiques, qui annoncent à cor et à cri l’avènement d’une liberté et d’une équité inégalées, le poids politique/économique des masses, ou des peuples, n’a jamais été aussi réduit. Son projet ‘globalitaire’ ne peut donc pas recevoir le label de ‘démocratique’. [The ‘superclass’... dominates the era of neo-liberal ideology. It is not easy to define it: it is most clearly composed of the managers of the great multinationals, the directors of the great banks, the oil sheikhs [and some prominent] political leaders, but [it also includes] some movie stars, intellectuals and ‘spiritual gurus’. Aside from these, [it also includes] a much more opaque number of [mafia bosses and] drug barons who feed its banking branch with ‘black money’. The ‘superclass’ is far from stable: it is possible to belong to it for some years or decades, and then to drop out of it again - mostly with a ‘golden parachute’. ...[N]umerically, it is small, but it is more powerful than any of the aristocracies and partitocracies that preceded throughout all of [recorded] human history. Despite a [public] discourse that continually speaks about a glorious dawn of unprecedented freedom and equality, the [real] political [and] economic weight of the masses has never been so small before. Thus, the globalist project [that is now pursued by the ‘superclass’] cannot be qualified as ‘democratic’ in any meaningful way.] (p. 291)

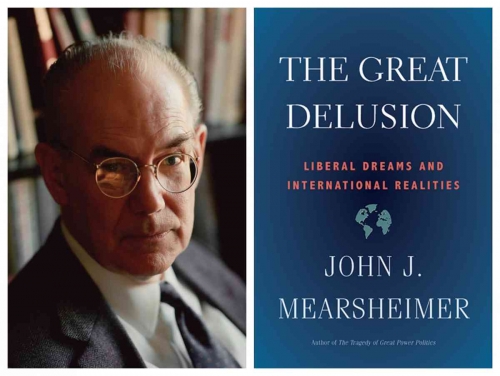

The globalist hostile elite instrumentalizes American military power and political influence: it uses American power and influence to further its own globalist agenda. It abuses American prestige, American wealth and American lives - this is the deepest reason for the anti-globalist and nationalist ‘populist’ backlash that brought Donald Trump into the White House. But the hostile elite operates above and behind formal institutions such as the presidency: in America, real power is largely exempt from institutional control and democratic correction. Real power resides in the ‘Washington swamp’, the ‘lying press’ and the ‘deep state’ - they determine policy; it is to fight these monsters that the American people chose Donald Trump to be its president. The monstrous power of the hostile elite, however, is so great that the public sphere is still dominated by Trump’s enemies, even two years after his election victory. The terrible anger and open sabotage with which the hostile elite responds to Trump is understandable: in the final analysis, the fate of the globalist hostile elite depends on its control over American military and political assets. The hostile elite needs to maintain its control over America’s monetary supply, America’ armed forces and America’s diplomatic network if it wants to maintain the international geopolitical chaos on which its financial interests and ideological chimaeras thrive.

The most pressing geopolitical concern of the hostile elite and the reason it needs absolute control over America is the permanent subjugation of its potentially most dangerous enemy: Europe. The deadly danger to nihilist and rootless globalism posed by Europe resides in its combination of technological-industrial/social-economic capacity with authentic cultural-historical rootedness/ethnicity-based identity. After the collapse of the Soviet Union the task of keeping Europe in subjugation to globalism, previously shared between the two superpowers, devolved on the United States alone. The globalist strategy to achieve this task started out twofold: the globalist hostile elite enforced a permanent weakening of newly re-united Germany (through formal sovereignty limits and ‘monetary union’ tribute payments to France) and it expanded American military presence eastward (through NATO enlargement). This double strategy, however proved problematic as a long-term solution to the ‘European Question’: given America’s many global commitments, its military presence throughout all of Europe constitutes a considerable liability that forces it into grotesque deficit spending and risqué diplomatic brinkmanship. Its centrepiece, the ‘containment’ of Germany, is also proving to be more problematic than previously thought: even the burdens of German unification (from 1990) and European single-currency liability (from 1999) have not been able to slow down the German social-economic motor. Quite the opposite has happened: EU expansion into the former Eastern Bloc (from 2004) is raising the old spectre of a German-led semi-autarkic geopolitical bloc. The prevention of such a Mitteleuropa project was the main aim of the Balkan ‘thwarting’ policy of the Entente powers in the early 20th Century: in the summer of 1914 it finally provoked the Central powers into starting the First World War. This geopolitical ‘larger picture’ provides an entirely different perspective on phenomena such as the ‘Financial Crisis’ of 2008, which started in America but led Europe into the crippling ‘European Debt Crisis’ of 2009, and the ‘Arab Spring’ of 2011, which led to the ‘European Migration Crisis’ of 2015.

This perspective is best formulated by Steuckers himself: La globalisation, c’est... le maintien de l’Europe, et de l’Europe seule, en état de faiblesse structurelle permanente. Et cette faiblesse structurelle est due, à la base, à un déficit éthique entretenu, à un déficit politique et culturel. Il n’y a pas d’éthique collective, de politique viable ou de culture féconde sans que Machiavel et les anciens Romains, auxquels le Florentin se référait, appelaient des ‘vertus politiques’, le terme ‘vertu’ n’ayant pas le sens stupidement moraliste qu’il a acquis, mais celui, latin, de ‘force agissante’, de ‘force intérieure agissante’... [Globalization means this: ...the maintenance of Europe - and only Europe - in a permanent state of structural weakness. In the final analysis, this weakness is due to a permanent ‘ethical deficit’ [that translates into] a political and cultural deficit. Collective ethics, viable politics [and] fruitful cultures are impossible without what Machiavelli, and the ancient Romans on whom the Florentine based hi[s thought], termed the ‘political virtues’ - a phrase in which the meaning of the word ‘virtue’ does not have the short-sighted moralistic charge that it has attracted recently, but rather the [original] Latin [meaning] of ‘acting force’ [and] ‘inner guiding force’.] (p. 279-80) Steuckers correctly points to the ‘ethical deficit’ of Europe as being imposed by globalist cognitive warfare, resulting in Europe’s debilitating lack of purpose and willpower. This deficit prevents psycho-historical catharsis, geopolitical assertiveness and decisionist self-defence. It renders Europe helpless in the face of acute existential threats such as the social implosion, mass-immigration and jihadist terror that are deliberately fostered by its enemies. This globalist ‘anti-European’ Europe is realized in the internalization of the cognitively dissonant globalist ‘mainstream media’ discourse of self-destructively interpreted ‘human rights’, ‘multiculturality’ and ‘diversity’. L’arme principale qui est dirigée contre l’Europe est donc un ‘écran moralisateur’, à sens unique, légal et moral, composé d’images positives, de valeurs dites occidentales et d’innocences prétendues menacées, pour justifier des campagnes de violence politique illimitée. [The main weapon employed against Europe is the uniquely ‘moralist [television, computer and telephone] screen’ that [is imposing specific] legal and moral ‘values’ [through] the positive ‘frame’ of so-called ‘Western values’ and supposedly ‘threatened innocence’ by justifying a [systematic] campaign of endless political terrorism.] (p.281)

This perspective is best formulated by Steuckers himself: La globalisation, c’est... le maintien de l’Europe, et de l’Europe seule, en état de faiblesse structurelle permanente. Et cette faiblesse structurelle est due, à la base, à un déficit éthique entretenu, à un déficit politique et culturel. Il n’y a pas d’éthique collective, de politique viable ou de culture féconde sans que Machiavel et les anciens Romains, auxquels le Florentin se référait, appelaient des ‘vertus politiques’, le terme ‘vertu’ n’ayant pas le sens stupidement moraliste qu’il a acquis, mais celui, latin, de ‘force agissante’, de ‘force intérieure agissante’... [Globalization means this: ...the maintenance of Europe - and only Europe - in a permanent state of structural weakness. In the final analysis, this weakness is due to a permanent ‘ethical deficit’ [that translates into] a political and cultural deficit. Collective ethics, viable politics [and] fruitful cultures are impossible without what Machiavelli, and the ancient Romans on whom the Florentine based hi[s thought], termed the ‘political virtues’ - a phrase in which the meaning of the word ‘virtue’ does not have the short-sighted moralistic charge that it has attracted recently, but rather the [original] Latin [meaning] of ‘acting force’ [and] ‘inner guiding force’.] (p. 279-80) Steuckers correctly points to the ‘ethical deficit’ of Europe as being imposed by globalist cognitive warfare, resulting in Europe’s debilitating lack of purpose and willpower. This deficit prevents psycho-historical catharsis, geopolitical assertiveness and decisionist self-defence. It renders Europe helpless in the face of acute existential threats such as the social implosion, mass-immigration and jihadist terror that are deliberately fostered by its enemies. This globalist ‘anti-European’ Europe is realized in the internalization of the cognitively dissonant globalist ‘mainstream media’ discourse of self-destructively interpreted ‘human rights’, ‘multiculturality’ and ‘diversity’. L’arme principale qui est dirigée contre l’Europe est donc un ‘écran moralisateur’, à sens unique, légal et moral, composé d’images positives, de valeurs dites occidentales et d’innocences prétendues menacées, pour justifier des campagnes de violence politique illimitée. [The main weapon employed against Europe is the uniquely ‘moralist [television, computer and telephone] screen’ that [is imposing specific] legal and moral ‘values’ [through] the positive ‘frame’ of so-called ‘Western values’ and supposedly ‘threatened innocence’ by justifying a [systematic] campaign of endless political terrorism.] (p.281)

Everywhere across Europe this globalist discourse is entirely internalized and primarily represented by the soixante-huitard generation that achieved a power monopoly in the wake of its ‘long march through the institutions’. Pendant les années de leur traversée du désert, ...les [utopistes]de [la] génération soixante-huitard] feront... un ‘compromis historique’ qui repose, ...premièrement, sur un abandon du corpus gauchiste, libertaire et émancipateur, au profit des thèses néolibérales, deuxièmement, sur une instrumentalisation de l’idée freudo-sartienne de la ‘culpabilité’ des peuples européens, responsables de toutes les horreurs commises dans l’histoire, et troisièmement, sur un pari pour toutes les démarches ‘mondialisatrices’, même émanant d’instances capitalistes non légitimées démocratiquement ou d’institution comme la Commission Européenne, championne de la ‘néolibéralisation’ de l’Europe, dont le pouvoir n’est jamais sanctionné par une élection. [During their years in the desert... the [utopists] of the [‘68] generation... made a ‘historical compromise’ that is based... on [three complementary strategies]: (1) an [abandonment and] betrayal of their [core] leftist ideology [of] freedom and emancipation in favour of neo-liberalism, (2) a [political] application of the Freudian-Sartrean notion of the ‘guilt’ of the European peoples, [who are held] responsible for all crimes in history and (3) an adherence to ‘globalizing’ processes - even [if those processes] are driven by [un]democratic [and] illegitimate capitalist powers of institution[s] such as the European Commission, [which has become] the champion of the ‘neo-liberalisation’ of Europe and which has never received a democratic mandate.[18]] (p.293) This ideological betrayal and this globalist collaboration, now the standard modalities of the European hostile elite, have brought European civilization to the brink of the abyss.

Steuckers points to the functionality of the treason of the European soixante-huitards in the larger framework of globalist geopolitics: this treason delivers Europe into the hands of a de facto ‘monster pact’ between two quintessentially anti-European globalist forces: liberal-normativism, as symbolized by American ‘Puritanism’, and islamism, symbolized by Saudi ‘Wahhabism’. Aujourd’hui, nous faisons face à l’alliance calamiteuse de deux fanatismes religieux : le wahhabisme, visibilisé par les médias, chargé de tous les péchés, et le puritanisme américain, camouflé derrière une façade ‘rationnelle’ et ‘économiste’ et campé comme matrice de la ‘démocratie’ et de toute ‘bonne gouvernance’. Que nous ayons affaire à un fanatisme salafiste ou hanbaliste qui rejette toutes les synthèses fécondes, génératrice et façonneuses d’empires, qu’elles soient byzantino-islamiques ou irano-islamisées ou qu’elles se présentent sous les formes multiples de pouvoir militaire équilibrant dans les pays musulmans, ou que nous ayons affaire à un fanatisme puritain rationalisé qui entend semer le désordre dans tous ces états de la planète, que ces états soient ennemis ou alliés, parce que ces états soumis à subversion ne procèdent pas de la même matrice mentale, nous constatons que toutes nos propres traditions européennes... sont considérées par ces fanatismes contemporains d’au-delà de l’Atlantique ou d’au-delà de la Méditerranée comme émanations du Mal, comme des filons culturels à éradiquer pour retrouver une très hypothétique pureté, incarnée jadis par les pèlerins du ‘Mayflower’ ou par les naturels de l’Arabie du VIIIe siècle. [In the contemporary world we are facing a disastrous [globalist, anti-European] alliance between two religious fanatisms: Wahhabism,[19] which is visualized as the scapegoat [‘bad cop’] in the [mainstream] media - and American puritanism, which is portrayed as a stable rational and economist reference frame [‘good cop’] that provides ‘democracy’ and ‘good governance’. But such [fanatisms] are [entirely] incompatible with our own European traditions. This is not only true for [‘Wahhabism’ and its] ‘Hanbalite and ‘Salafist’ [fellow-traveller] fanatisms[20] that are incompatible with the fertile, creative and imperial syntheses characteristic of [Traditional Islam, such as] Byzantine Islam and Persian Islam, but [it is] also [true] for the puritanically rationalized and militarily enforced [America-based] fanatism that is [now] creating chaos throughout the entire world (because all other cultural circles, irrespective of their allied or enemy status, necessarily represent incompatible mental worlds). To the fanatisms [that face Europe] across the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, [all of Europe’s authentic traditions] represent incarnations of Evil [pure and simple]: they represent mental worlds that they will fight to the death for the sake of their - highly hypothetical - purity, as modelled on the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ [of the 17th Century] Mayflower[21] and the bons sauvages[22] of the 8th Century Arabian Desert.] (p.261-2)

The totalitarian-regressive fanatisms of ‘Puritanical’ liberal-normativism and ‘Wahhabist’ islamism have to be overcome emotionally, intellectually and spiritually if European civilization and the European peoples are to survive the Crisis of the Modern West. At this critical juncture, the therapy that Traditionalism can recommend as having the greatest chance of success is the ultimate political-philosophical ‘emergency option’: Archaeo-Futurism.

4.

The Archaeo-Futurist Alternative

(political-philosophical therapy)

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet.

Lest we forget - lest we forget!

- Rudyard Kipling

The Archaeo-Futurist alternative for the globalist anti-European ‘EU project’ is based on a simultaneous retrograde recovery and forward projection of a Traditionalist concept that has long played a vital role in European history and may do so again: the European Imperial Idea. This is an idea that is strictly speaking supra-historical and can, therefore, be reactivated at any given point in history. The ideological abuse and historiographical misinterpretation of the European Imperial Idea in 19th and 20th Century (hyper-)nationalism - most recently in the ‘Third Reich’ - does not invalidate its supra-historical vitality. In this regard, Steuckers points to the vital importance of a correct understanding of the larger Traditionalist framework in which the Imperial Idea functions. Traditionalism states that all collective (linguistic, religious, ethnic, national) identities and the horizontally (worldly, physically) experienced differences between them are potentially organic parts of larger, synergetically unique entities with a higher, vertical, and transcendentally (spiritually, psychologically) experienced functionality. This entity can be identified as Imperium (German: Reich) - in the Western Tradition it derives its legitimacy from the ancient Roman Empire. Its numinous character becomes obvious from the fact that its mere mention conjures up a feeling of awe among those that naturally belong to it - and that inspires a feeling of fear among those that are unworthy of it.

Pour résumer brièvement la position traditional[iste],... disons que les horizontalités modernes ne permettent pas le respect de l’Autre, de l’être-autre. Si l’Autre est jugé dérangeant, inopportun dans son altérité, il peut être purement et simplement éliminé ou mis au pas, sans le moindre respect de son altérité, car l’horizontalité fait de tous des ‘riens ontologiques’, privés de valeur intrinsèque. Tel est l’aboutissement de la logique égalitaire, propre des idéologies et des systèmes qui ont voulu usurper et éradiquer la tradition ‘reichique’ : si tout vaut tout dans l’intériorité de l’homme, ou même dans sa constitution physique, cela signifie, finalement, que plus rien n’a de valeur spécifique, et si une valeur spécifique cherche à pointer envers et contre tout, elle sera vite considérée comme une anomalie qui appelle l’extermination. L’intervention fanatique et sanglante de ‘colonnes infernales’. La verticalité, en revanche, implique le devoir de protection et de respect, un devoir de servir les supérieurs et un devoir des supérieurs de protéger les inférieurs, dans un rapport comparable à celui qui existe, dans les sociétés et les familles traditionnelles, entre parents et enfants. La verticalité respecte les différences ontologiques et culturelles ; elle ne les considère pas comme des ‘riens’ qui ne méritent ni considération ni respect. [To summarize the traditional[ist] perspective... it may be said that modern[ist] horizontality impedes a[ny true] respect for [what is] Other and [what is D]ifferent. When the Other-ness of what is [D]ifferent is judged to be [mere] ‘interference’ [and] ‘inconvenience’, than it can be simply eliminated or ignored without the least respect for [its] Other-ness: [thus], modern[ist] horizontality reduces all [forms of authentic] identity to ‘ontological nullities’ without intrinsic value. This is the [inevitable] end result of the egalitarian logic that shapes ideologies and systems that aim at supplanting and erasing the imperial tradition. When everything is assumed to depend exclusively on human [subjective value], or even exclusively on [individual] human physical [existence], then nothing of specifically [objective] value remains. When any specific value points in a different [non-egalitarian] direction against the [perceived ‘common good’], then it is quickly identified as an ‘aberration’ that needs to be eliminated. This [results] in the fanatic and bloody intervention of ‘infernal columns’[23] [of modernist collectivism]. The principle of [Traditionalist] verticality, on the other hand, proceeds from a [reverse] duty: to protect and respect [the Other]. [This implies] the duty of [the commoners] to serve those set above them, and the duty of the higher-ranked to protect the lower-ranked, in a relationship that can be compared to that of parents and children in traditional communities and families. This verticality respects ontological differences and the cultural [expressions of these differences]: it does not reduce them to ‘[ontological] nullities’ unworthy of consideration and respect.] (p. 157)

Thus, the Traditionalist Imperial Idea implies a holistic vision in which all collective and individual [authentic] identities are organically fitted into a larger entity of synergetic ‘added value’. Il faut enfin... que chaque communauté et chaque individu aient conscience qu’ils gagnent à demeurer dans l’ensemble impéria[ux]au lieu de vivre séparément. Tâche éminemment difficile qui souligne la fragilité des édifices impériaux : Rome a su maintenir un tel équilibre pendant les siècles, d’où la nostalgie de cet ordre jusqu’à nos jours. ...[L]a civitas de l’origine... de l’Urbs, la Ville initiale de l’histoire impériale, ...s’est étendue à l’Orbis romanus. Le citoyen romain dans l’empire signale son appartenance à cet Orbis, tout en conservant sa natio et sa patria, appartenance à telle nation ou telle ville de l’ensemble constitué par l’Orbis. [In the final analysis, it is necessary... that every community and every individual realizes that it stands to benefit more from its allegiance to the imperial entity than from a separate existence. [This requires] a difficult balancing act, underlining the vulnerability of [all] imperial projects: for centuries, Rome managed to maintain such a balance - hence the nostalgi[c longing] for the [Roman] order that pervades [Europe] up to today. ... [as the Roman Empire grew], the original civitas... of the ancestral Urbs, [i.e.] the City from which imperial history unfolded,... grew into an Orbis romanus. In th[at] empire, Roman citizenship meant identification with that Orbis, even if [citizens] still belonged to a particular natio and a particular patria, [i.e.] even if [they permanently] retained [their] specific nationality and fatherland within the [larger] Orbis.] (p.129-31) D’abord, il faut préciser que le ‘Reich’ n’est pas une nation, même s’il est porté, en théorie, par un populus (le populus romanus) ou une ‘nation’ (la deutsche Nation) : ...[c’est] n’est pas [une chose] nationaliste, [c’est] même [une chose] anti-nationaliste. [I]l n’a rien contre les sentiments d’appartenance nationale, contre la fierté d’appartenir à une nation. De tels sentiments sont positifs... mais doivent être transcendés par une idée. Cette transcendance conduit à une verticalité, qui oppose à toutes les formes modernes d’horizontalité, ce qui est, par ailleurs, le noyau idéel, de toutes les traditions... [Above all, it should be made clear that an ‘Empire’ is no nation, even if it is theoretically carried by a [particular] populus ([i.e. a ‘people’ such as] the populus romanus) or a [particular] nation ([i.e. a ‘nation’ such as] the deutsche Nation): ...[the Empire] is not nationalist, [it is, in fact,] anti-nationalist. [I]t does not oppose the [collective] nationalist sentiment or the [individual] pride that [rightly] derives from national identity. Such sentiments are positive [in themselves]... but they should be surpassed by the [still higher imperial] idea. This transcendence determines a vertical direction that opposes all modern forms of horizontality. In the final analysis, this [verticality] constitutes the ideal core of all [authentic T]raditions.] (p. 156-7)

The practical combination of collective and individual identities is realised in the political application of the Traditionalist principle of subsidiarity, a late trace of which can still be detected in the Dutch anti-revolutionary principle of ‘sphere sovereignty’[24]). ...[L]e principe de ‘subsidiarité’, tant évoqué dans l’Europe actuelle mais si peu mis en pratique, renoue avec un respect impérial des entités locales, des spécificités multiples que recèle le monde vaste et diversifié. [...The principle of ‘subsidiarity’, often claimed by seldom practised in contemporary Europe, can provide [a new] imperial[ly legitimate] respect for the [many] local communities [and] specific identities that are found in the real world of great [authentically-rooted] diversity.] (p. 139)

In relation to the Imperial Idea, ‘identity politics’, ‘multiculturality’ and ‘diversity’ are effectively reduced to ‘non-issues’: they are organically resolved by - and dissolved in - a sublimation into the higher functionality of the Empire. L’empire est donc fait de multiplicités, de différences, qui n’ont rien de commun avec la fausse multiculturalité vantée par les médias d’aujourd’hui. Cette multiculturalité, escroquerie idéologique, relève justement de cette horizontalité qui vise à vider tous les hommes, autochtones et allochtones, de leur substance ontologique. Cette multiculturalité tue l’essentiel qui vit en l’homme. Toute politique qui cherche à la promouvoir est une politique criminelle, exterministe... [Thus, an Empire is based on [necessarily complex] pluralities [and] diversities that have nothing in common with the counterfeit ‘multiculturality’ currently promoted by the [main stream] media. This [fake] multiculturality represents an ideological deception that is based on [modernist] horizontality [and] that is meant to deprive all people - indigenous as well as non-indigenous - of their ontological substance. [That perverse kind of] multiculturality kills the essence that animates humanity. [Any form of] politics that aids and abet [this counterfeit multiculturality] constitutes criminal - and ethnocidal - politics....] (p.158) It is ironic that the Traditionalist concepts of the Imperial Idea and the Imperial Community provide much more tolerance and much more freedom than any kind of modernist ‘diversity’ and ‘democracy’ ever could.

5.

Sacrum Imperium

(neo-imperial therapy)

Hier die Ma[h]nen hehrer Krieger

Seien euch ein Musterbild

Führen euch vom Kampf als Sieger

[May the memory of the fearsome warriors

who fought before you, here inspire you

and lead you to glorious victory in battle]

- Joseph Hartmann Stuntz[25]

Western civilization is based on a vulnerable balance of complementary authentic identities that obtain synergetic ‘added value’ in a variety of historical interactions. This ‘added value’ can be expressed in the ‘hyper-boreal’ archetypes of Techne (technological liberation), Nomos (judicial liberation) and Evangelion (spiritual liberation).[26] But this ‘added value’, and the ethnicities on which it is based, require constant protection and guarding - this is the basis of the Traditionalist European Imperial Idea. En Europe, les structures de type impérial sont... une nécessité, afin de maintenir la cohérence de l’aire civilisationnelle européenne, dont la culture a jailli du sol européen, afin que tous les peuples au sein de cette aire civilisationnelle, organisée selon les principes impériaux, puissent avoir un avenir. [In Europe, structures of the imperial type... are indispensable for the cohesion of the European civilization sphere, which is grounded in the European soil - and for the future of the peoples that are indigenous to that sphere. [The maintenance of that cohesion requires] the organization of that sphere on imperial principles.] (p.214) A simultaneously idealistic and realistic - Archaeo-Futurist - reconsideration of the European Imperial Idea is essential for the protection of the European peoples and their common civilization. The extension of the European Imperial Idea to include the overseas peoples of European descent is a logical next step: this step has already been Archaeo-Futuristically explored in the concept of a ‘Boreal Alliance’. At a global level, such an alliance would find natural allies in the other two Indo-European Imperial Ideas: Persia and India - an Archaeo-Futurist exploration of this theme can be found in Jason Jorjani’s concept of the ‘World State of Emergency’. The alternative geopolitics that is required to do justice to these Archaeo-Futurist visions is already the object of concrete study in the anti-globalist Neo-Eurasianist movement.[27]

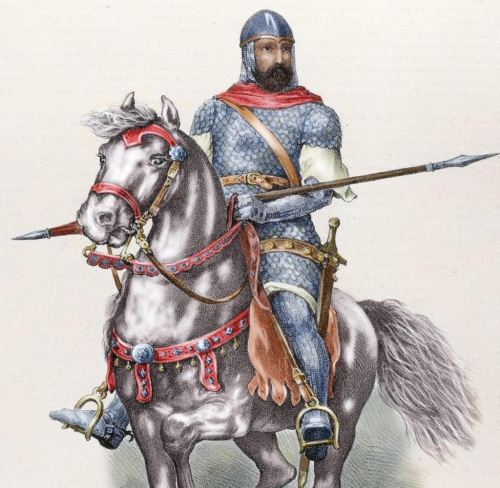

Traditionalism is tasked with the defence of the collective ‘Higher Vocation’ of the European peoples whenever it faces a serious threat.[28] Steuckers acts on this obligation by restating the Traditionalist vision of Europe: L’Europe, c’est une perception de la nature comme épiphanie du divin... L’Europe, c’est également une mystique du devenir et de l’action... L’Europe, c’est une vision du cosmos où l’on constate l’inégalité factuelle de ce qui est égal en dignité ainsi qu’une pluralité de centres... [C’est] une nouvelle vision de l’homme, impliquant la responsabilité pour l’autre, pour l’écosystème, parce que, ... sur [s]es bases philosophiques, ...l’homme... est un collaborateur de Dieu et un miles imperii, un soldat de l’empire. Le travail n’est plus malédiction ou aliénation mais bénédiction et octroi d’un surplus de sens au monde. La technique est service à l’homme, à autrui... La construction de l’Europe... nécessite de revitaliser une ‘citoyenneté d’action’, où l’on retrouve la notion de l’homme coauteur de la création divine et l’idée de responsabilité. [‘Europe’, [as a Traditionalist concept,] is a vision in which the natural world is treated as Divine Epiphany... [Such a] Europe is a mystery of becoming and enacting... [Such a] Europe is a cosmic vision that recognizes the factual inequality of all things as well as their equality in dignity - and [that validates cultural-historical and geo-political] multipolarity... [This] new vision of humanity implies a responsibility for [all that] is different [and] for the entire [natural and human] ecosystem because... at its philosophical [this vision establishes]... every man as a collaborator of God - [as] a miles imperii, a soldier of the [divinely instituted] Empire. Thus, work no longer represents a curse or alienation,[29] but a blessing as a duty regarding a [higher sense of] responsibility for [all of creation]. Technology serves man in his work - [also] for the benefit of the other...[30] The construction of Europe... demands a new ‘activist citizenship’ that is based upon the idea of man as a co-worker in the Divine Creation - and upon the idea of a [cosmic] responsibility that is rooted in authentic identity and vocation.] (p.138-9). It is clear that the Higher Vocation of the European peoples does not stop at the geographical borders of the European subcontinent: it is retained by the European peoples that have moved across these boundaries to dominate the boreal and austral regions overseas.

Inwardly, this Higher Vocation requires individual self-discipline, individual work ethic and individual acceptance of hierarchical order - and therefore a radical reversion of the narcissist, hedonist and collectivist existential modality that is fostered and maintained by the liberal-normativism that dominates the postmodern West. This requires a transition to a new (or re-newed) existential condition, dominated by authentic norms and values - and by a legitimate Authority. In the European Tradition, which is based on a Roman archetype, this Authority bears the title ‘Caesar’ - Emperor.[31] Dans la conception [traditionaliste] hiérarchique des êtres et des fins terrestres... l’empire constituait le sommet, l’exemple impassable pour tous les autres ordres inférieurs de la nature. De même, l’empereur, également au sommet de cette hiérarchie par la vertu de sa titulaire, doit être un exemple pour tours les princes du monde, non pas en vertu de son hérédité, mais de supériorité intellectuelle, de son connaissance ou des ses connaissances. Les vertus impériales sont justice, vérité, miséricorde et constance... [In the [Traditionalist] vision of the hierarchy of creatures and purposes... the Empire represents the highest aim, the unrivalled example for all lower natural orders. This means that the emperor, who stands at the apex of this hierarchy on the basis of his title, provides an example for all [other] worldly princes - not on the grounds of his [earthly] descent but [on the grounds] of his intellectual superiority and of his abilities and insights. [In him,] the imperial ‘[political] virtues’ of justice, truth, mercy and stability [are realized]...]. (p. 136) Obviously, a recognizably legitimate Authority is difficult to imagine in the present European context, but still, the archetype of this Authority is indispensable as a fixed point of reference. To a certain extent, the same applies to the Imperial Idea as such: within the present-day discourse of political philosophy, the concept is primarily meant as a thought experiment that allows the patriotic-identitarian movement to chart a new course towards a new destination. In the same way that the ‘Kingdom of Heaven’ embodies the Higher Vocation of Christianity, thus the Imperial Idea embodies the Higher Vocation of European civilization - even if the ideal has not yet been tangibly realized in the here and now. Thus, the old Traditionalist Imperial Idea can serve as a reference point for a new Archaeo-Futurist Imperial Idea. Here too, the hierarchical political philosophy of Neo-Eurasianism can serve as a bridge.

Outwardly, any Traditionalist Imperial Idea requires collective self-identification, collective pride and collective dedication - to the point of supreme self-sacrifice. In this regard, it is important to emphasize that the Imperial Idea, as it is defended by the highest command authority, has a positive relation to the various authentic identities that are protected by the Empire through subsidiary guarantees: it literally has ‘added value’. Thus, a Traditionalist definition of a European - or even Western - Empire does not diminish specific linguistic, religious, cultural and ethnic identities that it contains: it merely adds an extra identity, viz. a European - or even Western - identity. This identity is not dominant in an inward sense (i.e. in citizens’ self- representation on the individual level), but it is dominant in an outward sense: to the outside world it represents a collective will. This implies that, to the outside world, the Empire represents an absolute standard that must be expressed in physical boundaries. Thus, the liberal-normative delusion of globalist ‘universal values’ and ‘open borders’ are entirely incompatible with effective maintenance of the classical norms of civilization that are incarnated in the Traditionalist Imperial Idea. L’empire se conçoit comme un ordre, entouré d’un chaos menaçant, niant par là même que les autres puissent posséder eux-mêmes leur ordre ou qu’il ait quelque valeur. Chaque empire s’affirme plus ou moins comme le monde essentiel, entouré de mondes périphériques réduits à des quantités négligeables. L’hégémonie universelle concerne seulement “l’univers qui vaut quelque chose”. Rejeté dans les ténèbres extérieures, le reste est une menace dont il faut se protéger. [The Empire conceives of itself as an order that is surrounded by threatening chaos [and in doing so] it must effectively deny that other [civilizations] may have their own order of [equal] intrinsic value. To a certain extent, every Empire views itself as a ‘world on its own’, surrounded by ‘peripheral worlds’: these ‘other worlds’ are reduced to negligible entities.[32] Universal hegemony exclusively applies to the ‘valuable universe’ [that is one’s own]. The rest [of reality] is intellectually and psychologically rejected [and thrust] into the Outer Dark: it is reduced to a threat that should be defended against.[33]] (p. 129)

6.

Ex oriente lux

(psycho-historical therapy)

Hail to our Prince!

We have searched the northwest winds for you

To you we offer our mortality

You are our Oath!

- freely inspired by Hereditary

The effectiveness of any Archaeo-Futurist therapy for the psycho-historical self-mutilation of Western civilization depends on the re-discovery and the re-activation of its archetypes.[34] From a meta-historical perspective, the political experiment of the narrowly nationalist and hyper-biodeterminist ‘Third Reich’ represents a rather improvised attempt at re-activating of these archetypes. The (actually rather tenuous) association of the Traditionalist Imperial Idea with the ‘Third Reich’ and the European Götterdämmerung of 1945 effectively removed these archetypes from Western public discourse. Thus, the idealistic, knightly and ascetic existential models that are linked to these archetypes, as incarnated in the ancient vocations of Academy, Nobility and Church, lost their raison d’être - the utter decay of the West’s academic, military and ecclesiastical institutions proves this point beyond a reasonable doubt. This psycho-historic Untergang has recently reached the point that anything that even vaguely refers to ‘aristocratic’, ‘aryan’ or ‘masculine’ quality is automatically considered ‘subject’ in the public sphere. Deep conditioning in matriarchal oikophobia and resentful feminization has destroyed the old Western institutions of Academy, Army and Church.

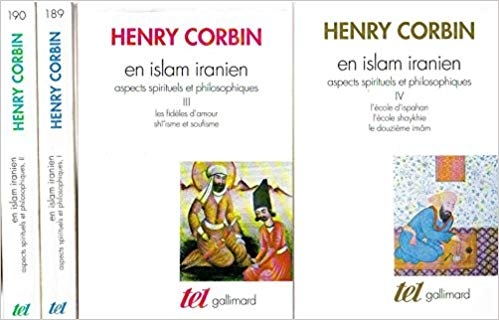

Even so, this process is far from irreversible - it may even be considered as an indispensable part of a purifying ‘dialectic process’.[35] In such a process, an extreme negative polarity is a necessary precondition for any extreme discharge of positive energy. Thus, the ‘deconstruction’ of the improvised and superficial ‘hyper-nationalist’ and ‘hyper-biodeterminist’ ideology of the ‘Third Reich’ may, in fact, turn out to be a necessary precondition for a re-discovery and re-activation of the deepest archetypes of the Indo-European Tradition. The Archaeo-Futurist exploration of these deepest archetypes has started only recently, but the direction in which the new Golden Dawn of the West must be sought is already clear: - ex oriente lux. Jason Jorjani, the philosophical pioneer of the Archaeo-Futurist Revolution in the New World has already crossed the ‘event horizon’ of Western Modernity and he has already reported back on the civilizational outlines that are becoming visible in the first rays of what may be termed its coming ‘Golden Dawn’. It is cannot be a coincidence that Robert Steuckers, the foreman of Traditionalism in the Low Countries, is pointing in the same direction. Both are pointing to the oldest Indo-European archetypes that have been preserved in the Persian Tradition - and both point to their imminent return to the West.