Eduard Alcántara

Ex: https://septentrionis.wordpress.com

Nos resulta tarea inaplazable la de sentar las bases de un proyecto de Europa que supere, hasta en sus más nimios supuestos, el conglomerado agónico y servil en que se ha convertido buena parte de nuestro continente y en el que se han, asimismo, sumido, esas tierras extraeuropeas habitadas por gentes de matriz indoeuropea. Por ello encontramos, además de muy acertado en sus planteamientos, muy oportuna la elaboración de estos Protocolos.

En su elaboración se han tocado, a nuestro parecer, todas las teclas que se debían de tocar: desde las bases socio-políticas en que deberá asentarse esa nueva Europa, que no soslaya cuál será su organización territorial-administrativa, pasando por la geoestrategia que deberá hacer propia, continuando por hasta cuál será la heráldica que deberá representarlo y acabando por tratar la que deberá ser su posición en el tema de la Trascendencia.

En su elaboración se han tocado, a nuestro parecer, todas las teclas que se debían de tocar: desde las bases socio-políticas en que deberá asentarse esa nueva Europa, que no soslaya cuál será su organización territorial-administrativa, pasando por la geoestrategia que deberá hacer propia, continuando por hasta cuál será la heráldica que deberá representarlo y acabando por tratar la que deberá ser su posición en el tema de la Trascendencia.

Compartimos el espíritu, la letra y el contenido de estos Protocolos y nos adherimos a ellos en todos los ámbitos tratados. Y como no se trata de resultar reiterativos con respecto a lo desarrollado en los mismos nos hemos hecho el propósito de centrarnos, especialmente, en una cuestión: la Espiritual. Y lo hemos decidido así por considerar ésta como la basilar si es que uno pretende plantearse una regeneración sustancial, real y digna de ser considerada como algo más que un simple parche puesto al estado paupérrimo y desolador en el que halla subsumida la gens europoide y al estado degradado de todas sus (en ocasiones no tan suyas) creaciones políticas, jurídicas, sociales, económicas, “culturales”,…

Hemos de tener siempre bien diáfana la idea de que toda institución, estructura y/u organización política, jurídica, social, económica y toda deriva cultural son siempre la consecuencia de una determinada manera de contemplar, entender, percibir y vivir la existencia. Son siempre el fruto de una determinada visión del mundo y de la vida. Son, en definitiva, el producto de una cosmovisión concreta. Pueden ser la consecuencia (tal cual acontece en estos destartalados, desangelados e inorgánicos tiempos agónicos y terminales por los que estamos transitando) de atisbar, sentir y vivir la existencia bajo supuestos de corte positivista, utilitarista, reduccionista, relativista y materialista o, por el contrario, pueden ser el reflejo de una concepción Superior del hombre y de la existencia, que no se ve -por tanto- amputada en su dimensión Trascendente y que postula valores eternos e inmutables.

Si la Europa desnortada, atribulada y alienante que pretendemos subvertir es la del triunfo de la Materia no queda otra que alzar la bandera del Espíritu para voltearla íntegramente. Ninguna alternativa que no contemple al hombre como portador no sólo de un compuesto psíquico-físico sino también de una dimensión Trascendente no debemos considerarla como auténtica e integral alternativa sino como parcheamiento que no hará más que alargar la situación decrépita y crepuscular que estamos padeciendo pero que en ningún caso habrá dado con las claves que explican el porqué del estado de decadencia y postración coetáneos. Podemos, labor titánica por otro lado, conseguir cambiar el actual armatoste político por otro que nos resulte orgánico, jerárquico y antiigualitarista. Podemos, aunque de conseguirse resultaría admirable, reemplazar las relaciones y los engranajes sociales actuales basados en criterios económicos por otros de índole comunitario y gremial-corporativo. Podemos, asimismo, sustituir el sistema capitalista-financiero por otro basado en el trabajo y la producción y no en la usura y en la especulación. Podemos, en definitiva, llevar a cabo una revolución en estos tres órdenes (político, económico, social), pero ésta acabará languideciendo debido a que nunca habrá traspasado el dominio de lo material y del plano mundano de la existencia. Al no estar anclada en una cosmovisión metafísica de la vida y de la existencia la revolución irá deshaciéndose como un terrón de azúcar en un vaso de agua, pues el hombre que la habrá hecho triunfar, el hombre que (por la lucha de otros) de ella se beneficie o el hombre que herede sus frutos no vivirá cada cotidiano actuar suyo como una especie de rito que lo aúne con lo Superior y Sacro, pues la revolución no habrá partido de premisas Espirituales, sino que su adhesión a los logros de la Revolución sólo partirá de su voluntad y ésta puede variar como lo hace aquella voluble psique autónoma que no está subordinada a una dimensión Superior a ella cual es la del Espíritu. El Espíritu es permanente, eterno e inmutable y, por ello, el alma-psique supeditada a aquél está informada por valores permanente y no fluctuantes. Y permanentes y no fluctuantes será la voluntad que en ella anide, así como la adhesión y la fidelidad a los principios de la revolución. Una mente autónoma, sin cordón umbilical que la une al Espíritu, irá cayendo, con mayor o menor celeridad, en la inercia del egoísmo, del individualismo y del consumismo y estos “ismos” acabarán dando al traste con aquel tipo de ordenamiento social orgánico y comunitario conquistado por la Revolución incompleta que se olvidó del plano de lo Trascendente, y acabarán desembocando, de nuevo, en un sistema capitalista que se alimenta de ellos (de los dichos “ismos”).

Debe quedar, pues, claro que tanto en el Hombre nuevo que sea el propio de ese Sacro Imperio como en la concepción, vertebración y constitución de este último se debe establecer una jerarquización irrenunciable que tiene en su cúspide al Espíritu, por debajo de éste al alma-psique o mente en el hombre y al elemento cultural en el Imperio y en el plano inferior el cuerpo en el ser humano y la organización económica y social en el dicho Imperio.

Tras haber repasado estas premisas creemos llegado el momento de relacionarlas con lo redactado en estos Protocolos a los que se nos ha concedido el privilegio de prologar.

Así, en el Protocolo I, titulado “Proclama para el despertar de Europa”, se realiza la siguiente declaración de principios …opinamos que la misma representa la clave de bóveda de cualquier ulterior desarrollo y/o enumeración de principios:

“Nosotros somos herederos de una Idea perenne y multisecular que trasciende los tiempos”.

No puede, por menos, que venirnos a la mente aquel aserto que Julius Evola incluía en el capítulo VIII de “Orientaciones” cuando afirmaba que “es en la Idea donde debe ser reconocida nuestra verdadera patria.”

Con ello debe expresarse la asunción de que todo ordenamiento humano y todo discurrir en este mundo debe asentarse siempre en la certidumbre de la existencia de un Principio Supremo (la Idea) eterno e inmutable que se halla en el origen de todo el mundo manifestado y en la certidumbre de que el cosmos que de dicho Principio emana se halla constituido y compenetrado por unas fuerzas sutiles y sacras (macrocosmos) que lo vertebran y armonizan y que cualquier construcción política aquí abajo (en el microcosmos) debe ser fiel reflejo del orden (el Ordo del que se hablaba en el Medievo o el Rita del hinduismo) que rige allá en lo alto (en el macrocosmos), por lo cual el Imperium debe ser considerado, desde la óptica de la Tradición, como la forma más fidedigna de implantar, en el plano terrenal, el Orden de los mundos celestes. Un tal Imperium, así, debe recibir el atributo de Sacro.

Así mismo comentábamos que todo discurrir en este mundo debe asentarse siempre en la certidumbre de la existencia del mencionado Principio Supremo, por lo cual el hombre debe ritualizar y sacralizar todo acaecer de su cotidianidad ya que su accionar debe estar en consonancia y en sintonía con el equilibrio y la armonía que rigen lo Alto.

Por igual motivo se deben sacralizar todo tipo de celebraciones (estacionales, agrícolas,…), pues son recuerdo y recreación de los tempos de formación del mundo manifestado y de los ritmos cósmicos. La ritualización de esas celebraciones contribuye a la armonía, al equilibrio y a la interconexión de todo el entramado cósmico.

Volviendo al concepto de la Idea reseñado en este primer Protocolo escribíamos en cierta ocasión, con el propósito de aunarlo con la institución del Imperium, que “la Idea (en el sentido Trascendente) sería el eje alrededor del cual giraría todo un entramado armónico. Una Idea que a lo largo de la historia de la humanidad ha ido revistiéndose de diferentes maneras. Una Idea que -rastreando la historia- toma, por ejemplo, cuerpo en lo que simbolizaba la antigua Roma. Y Roma representará a dicha Idea de forma muy fidedigna. La Idea encarnada por Roma aglutinará a su alrededor multitud de pueblos diversos que, conservando sus especificidades, participarán de un proyecto común e irán dando cuerpo a este concepto de orden en el microcosmos que representa la Tierra. Estos pueblos dejarán de remar aisladamente y hacia rumbos opuestos para, por contra, dirigir sus andaduras hacia la misma dirección: la dirección que oteará el engrandecimiento de Roma y, en consecuencia, de la Idea por ella representada. De esta manera Roma se convertirá en una especie de microcosmos sagrado en el que las diferentes fuerzas que lo componen actuarán de manera armoniosa al socaire del prestigio representado por su carácter sacro (por el carácter sacro de Roma). Así, el grito del Roma Vincis coreado en las batallas será proferido por los legionarios con el pensamiento puesto en la victoria de las fuerzas de lo Alto; de aquellas fuerzas que han hecho posible que a su alrededor se hayan unido y ordenado todos los pueblos que forman el mundo romano, como atraídos por ellas cual si de un imán se tratase.” (1)

Como sea que en nuestra cita se ha hecho directa alusión a la antigua Roma como buen paradigma de esta idea sacra imperial no estará por menos, con el objeto de ir afinando y perfilando mejor pormenores de esta concretización histórica del Imperium, que acabemos reproduciendo otros desarrollos que de ello hicimos:

“Roma aparece, se constituye y se desarrolla en el seno de lo que multitud de textos Tradicionales definieron como Edad de Hierro, Edad del Lobo o Kali-yuga. Edad caracterizada por el mayor grado de caída espiritual posible al que pueda arribar el hombre: por el mayor nivel de oscurecimiento de la Realidad Trascendente. Roma representa un intento heroico y solar por restablecer la Edad Áurea en una época nada propicia para ello. Roma nada contracorriente de los tiempos de dominio de lo bajo que son propios de la Edad de Hierro. Es por ello que, tras el transcurrir de su andadura histórica, cada vez le resultará más difícil que la generalidad de sus ciudadanos sea capaz de percibir su esencia y la razón metafísica de su existencia (las de Roma). Por ello -para facilitar estas percepciones sacras- tendrá que encarnarlas en la figura del Emperador; el carácter sagrado del cual -como sublimación de la naturaleza sacra de Roma- ayudará al hombre romano a no olvidar cuál es la esencia de la romanidad: la del Hecho Trascendente. Una esencia que conlleva a la sacralización -a través de ritos y ceremonias- de cualquier aspecto de la vida cotidiana, de cualquier quehacer y, a nivel estatal, de las instituciones romanas y hasta de todo el ejercicio de su política.

Con la aparición de la figura del Emperador Roma traspasa el umbral que separa su etapa republicana de la imperial. Este cambio fue, como ya se ha señalado, necesario, pero ya antes de dicho cambio (en el período de la República) Roma representaba la idea de Imperium, por cuanto la principal connotación que, desde el punto de vista Tradicional, reviste este término es de carácter Trascendente y la definición que del mismo podría realizarse sería la de una unidad de gentes alrededor de un ideal sacro. Por todo lo cual, tanto la República como el Imperio romanos quedan incluidos dentro de la noción que la Tradición le ha dado al vocablo Imperium.

Así las cosas la figura del Emperador no podía no estar impregnada de un carácter sagrado que la colocase al nivel de lo divino. Por esto, el César o Emperador estuvo siempre considerado como un dios que, debido a su papel en la cúspide piramidal del Imperio, ejercía la función de ´puente´ o nexo de unión entre los dioses y los hombres. Este papel de ´puente´ entre lo divino y lo humano se hace más nítido si se detiene uno a observar cuál era uno de los atributos o títulos que atesoraba: el de Pontifex; cuya etimología se concreta en ´el hacedor de puentes´. De esta manera el común de los romanos acortaba distancias con un mundo del Espíritu al que ahora veía más cercano en la persona del Emperador y al que, hasta el momento de la irrupción de la misma -de la figura del Emperador-, empezaba a ver cada vez más alejado de sí: empezaba a verlo más difuso debido al proceso de caída al que lo había ido arrastrando el deletéreo kali-yuga por el que transitaba.

Los atributos divinos del Emperador respondían, por otro lado, al logro interno que la persona que encarnaba dicha función había experimentado. Respondían a la realidad de que dicha persona había transmutado su íntima naturaleza gracias a un metódico y arduo trabajo interior que se conoce con el nombre de Iniciación. Este proceso puede llevar (si así lo permiten las actitudes y aptitudes del sujeto que se adentra en su recorrido) desde el camino del desapego o descondicionamiento con respecto a todo aquello que mediatiza y esclaviza al hombre, hasta el Conocimiento de la Realidad que se halla más allá del mundo manifestado (o Cosmos) y la Identificación del Iniciado con dicha Realidad. Son bastantes los casos, que se conocen, de emperadores de la Roma antigua que fueron Iniciados en algunos de los diferentes Misterios que en ella prevalecían: de Eleusis, mitraicos,… Así podríamos citar a un Octavio Augusto, a un Tiberio, a un Marco Aurelio o a un Juliano.

La transustanciación interna que habían experimentado se reflejaba no sólo en las cualidades del alma potenciadas o conseguidas sino también en el mismo aspecto externo: el rostro era fiel expresión de esa templanza, de ese autodominio y de ese equilibrio que habían obtenido y/o desarrollado. Así, el rostro exhumaba gravitas y toda la compostura del emperador desprendía una majestuosidad que lo revestían de un hálito carismático capaz de aglutinar entorno suyo a todo el entramado social que conformaba el orbe romano. Asimismo, el aura espiritual que lo impregnaba hacía posible que el común de los ciudadanos del Imperio se sintiese cerca de lo divino. Esa mayoría de gentes, que no tenía las cualidades innatas necesarias para emprender las vías iniciáticas que podían hacer posible la Visión de lo metafísico, se tenía que conformar con la contemplación de la manifestación de lo Trascendente más próxima y visible que tenían a su alcance, que no era otra que aquélla representada por la figura del Emperador. El servicio, la lealtad y la fides de esas gentes hacia el Emperador las acercaba al mundo del Espíritu en un modo que la Tradición ha definido como de ´por participación´.” (2)

Este recorrido y análisis por la Roma antigua debe ser completado y compenetrado por otro. Así, la concretización histórica del Imperium se podrá cotejar en más de un caso y ayudará a tener un conocimiento más completo acerca de cuáles pueden ser los ejes y los modelos que contribuyan a que el Sacro Imperio perseguido por estos Protocolos sea concebido y entendido de la manera más fidedigna posible. Por estos motivos no vamos a privarnos de recordar lo que en su día expusimos acerca del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico que floreció en la Edad Media y que “que nació con la vocación de reeditar al fenecido, siglos antes, Imperio Romano y convertirse en su legítimo continuador” (no en vano se apela, en el artículo 15º del Capítulo II del Protocolo II, al “milenario anhelo de unidad, nacido ya con el Sacro Imperio medieval”):

“El título de ´Sacro´ ya nos dice mucho acerca de su fundamento principal. También, en la misma línea, es clarificador el hecho de que el emperador se erigiera en cabeza de la Iglesia; unificando además, de esta manera, en su cargo las atribuciones o funciones política y espiritual.

De esta guisa el carisma que le confiere su autoridad espiritual (amén de la política) concita que a su alrededor se vayan uniendo reinos y principados que irán conformando esta idea de un Orden, dentro de la Cristiandad, que será el equivalente del Orden y la armonía que rigen en el mundo celestial y que aquí, en la Tierra, será representado por el Imperium.

La legitimidad que su carácter sagrado le confiere, al Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico, es rápidamente reconocida por órdenes religioso-militares que, como es el caso de la del Temple, son dirigidas por una jerarquía (visible u oculta) que conoce de la Iniciación como camino a seguir para experimentar el ´Segundo Nacimiento´, o palingénesis, que no es otro que el nacimiento al mundo del Espíritu. Jerarquía, por tanto, que tiene la aptitud necesaria para poder reconocer dónde se halla representada la verdadera legitimidad en la esfera espiritual: para reconocer que ella se halla representada en la figura del emperador; esto sin soslayar que la jerarquía templaria defiende la necesidad de la unión del principio espiritual y la vía de la acción –la vía guerrera- (complementariedad connatural a toda orden religioso-militar) y no puede por menos que reconocer esta unión en la figura de un emperador que aúna su función espiritual con la político-militar.

Para comprender aún mejor el sentido Superior o sagrado que revistió el Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico se puede reflexionar acerca de la repercusión que tuvo el ciclo del Santo Grial en los momentos de mayor auge y consolidación de dicho Imperio. Una repercusión que no debe sorprender a nadie si nos atenemos a los importantes trazos iniciáticos que recorren la saga griálica y a cómo se aúnan en ella lo guerrero y lo sacro en las figuras de unos caballeros que consagran sus vidas a la búsqueda de una autorrealización espiritual simbolizada en el afán mantenido por hallar el Grial” (3)

En el Artículo 3º del Capítulo I del Protocolo V se nos recuerda que “El Sacro Imperio se mantuvo como entidad predominante en Europa durante mil años hasta que en 1806 fue disuelto por Napoleón contra toda legitimidad.” (4)

En el Protocolo I se explica que “la Idea no es propiedad de ningún régimen político sino de una Fuerza independiente del tiempo”. Y no se piense que se habla en abstracto, que se lanzan ocurrentes sentencias para rodear esta obra de cierto halo dilettante. No es así. Esa Fuerza no es otra que la que hace de la Tradición algo vivo y cargado de un sentido Superior. Es por ello que en el Protocolo VI, dedicado a “Religión y Espiritualidad”, se propugna una “religiosidad que contempla el Mundo como expresión de una Fuerza sagrada, de un Espíritu que es increado, absoluto y eterno, de un Dios Incognoscible al cual veneramos sin temor pero con respeto.”

Así, Julius Evola nos legó esta definición: “En su significado verdadero y vivo, Tradición no es un supino conformismo a todo lo que ha sido, o una inerte persistencia del pasado en el presente. La Tradición es, en su esencia, algo metahistórico y, al mismo tiempo, dinámico: es una fuerza general ordenadora en función de principios poseedores del carisma de una legitimidad superior -si se quiere, puede decirse también: de principios de lo alto-, fuerza que actúa a lo largo de generaciones, en continuidad de espíritu y de inspiración, a través de instituciones, leyes, ordenamientos que pueden también presentar una notable variedad y diversidad”. (5)

¿Y de dónde proviene esta Fuerza? Pues de lo Alto. Entiéndase, pues, que “las esencias del Mundo Tradicional emanan de de lo Alto; de lo que eleva al Hombre y lo transforma realmente por dentro, liberándolo de las ataduras y condicionamientos que más lo esclavizan: pasiones, egos engordados, impulsos incontrolados, pulsiones incontrolables, sentimentalismos turbadores del ánimo, bajos instintos,… Una alternativa auténtica al materialismo (verdadero meollo del Sistema) no puede pensarse si no es en base a una cosmovisión de corte metafísico; esto es, Tradicional.” (6)

Nos ha parecido muy acertada esa fórmula que, en el Protocolo I, habla de “Hombres contra el tiempo”, porque de ella se extraen múltiples enseñanzas, como la de que ese Hombre va ineludiblemente ligado a las Civilizaciones del Ser y no a las Civilizaciones del Devenir. El Sacro Imperio es el Imperio del Ser. Es el Imperio penetrado hasta el tuétano por la Luz del Espíritu. Es el Imperio asentado en lo Inmutable, Eterno e Imperecedero. Es el Imperio que insufla valores eternos a todos los que forman parte de él. Las Civilizaciones del Devenir, por el contrario, se sustentan en la perecedera materia, en los cambiantes impulsos de la psique y en los arrebatos pasajeros …son, pues, civilizaciones inestables que aunque parezcan todopoderosas, por lo asfixiantes y represivas que resultan, no son más que gigantes con pies de barro.

De esa fórmula también se extraen enseñanzas como la de que son Hombres Integrales los que emergerán al albor del Sacro Imperio. Son Hombres que serán señores de sí mismos y que enarbolarán valores tales como el de la lealtad, la fidelidad, el espíritu de servicio y sacrificio, el heroísmo, el equilibrio interior, la gravedad (tal como, p. ej., entendían la gravitas los antiguos romanos), la derechura interna, el honor o, más aún, el pundonor. Finiquitarán, pues, esos hombres esclavos de sus pasiones desaforadas, de sus impulsos exacerbados, de sus emociones incontroladas y de sus bajos instintos. Se acabarán esos hombres vulgares, propios de los tiempos crepusculares en los que nos agitamos vermicularmente, carentes de personalidad y que se mueven por los innumerables estímulos externos a que son sometidos y que los convierten en presa fácil del más alienante consumismo, del más obsesivo pansexualismo y del más monstruoso materialismo. Ese hombre fugaz y variable ya no encontrará lugar alguno en el seno del Sacro Imperio.

A ese hombre fugaz lo pretendimos situar y definir cuando, hace un tiempo, comentábamos que “si la Edad de Oro equivale al Mundo de la Tradición Primordial y puede ser calificada como la Edad del Ser y de la Estabilidad (de ahí su mayor duración) las restantes edades comportan la irrupción de un mundo moderno que puede, a su vez, ser denominado como mundo del devenir y del cambio (de ahí la cada vez menor duración de sus sucesivas edades). En verdad, no en balde, se puede constatar que en los últimos 50 años la vida y las costumbres han cambiado mucho más de lo que habían cambiado en los 500 años anteriores. Los traumáticos conflictos generacionales que se sufren, hoy en día, entre padres e hijos no se habían dado nunca en épocas anteriores (al menos con esta intensidad) debido a que los cambios en gustos, aficiones, hábitos y costumbres se sucedían con más lentitud. Los cambios bruscos, frenéticos y continuos propios de nuestros tiempos han dado lugar a lo que Evola definió como ‘el hombre fugaz’. Hombre fugaz que es el propio de la fase crepuscular por la que atraviesa la presente Edad de Hierro, caracterizada (esta fase) no ya por la hegemonía del Tercer ni del Cuarto Estado o casta (léase burguesía y proletariado) sino por la del que, con sagacidad premonitaria, Evola había previsto, pese a no haber vivido, como preponderancia del Quinto Estado o del financiero o especulador propio del presente mundo globalizado, gregario y sin referentes de ningún tipo. Este sujeto hegemónico en el Quinto Estado equivaldría al paria de las sociedades hindúes que no es más que aquél que ha sido infiel, innoble y disgresor para con su casta y ha sido expulsado del Sistema de Castas para convertirse en alguien descastado y sin tradición ni referentes. El hombre fugaz no se siente jamás satisfecho, vive en continua inquietud y convulsión. Su vacío existencial es inmenso y nada le llena. Intenta distraer dicho vacío con superficialidades, por ello su principal objetivo es poseer, tener y consumir compulsivamente. Cuando consigue poseer algo enseguida se siente insatisfecho porque ansía poseer otra cosa diferente, de más valor económico o de mayor apariencia para así poder impresionar a los demás. Y es que el mundo moderno es el mundo del tener y aparentar, en oposición del Mundo Tradicional que lo es del Ser. Este hombre fugaz se mueve por el ‘aquí y ahora’, pues lo que desea lo desea inmediatamente, no puede esperar. Su agitación no le permite pensar en el mañana.” (7)

Es ante este despojo, cual es el hombre fugaz, ante el que se erige el Hombre Integral. Ese hombre que es capaz de gobernarse a sí mismo porque no depende de los inputs que le pretenden inocular desde afuera. Ese hombre que es consciente, tal como se afirma en el Protocolo I, de que “nuestra fuerza creadora reposa en nosotros y que de nosotros depende dominar la vida” …y no ser dominados por ella.

………………………..

En la conclusión del primer Protocolo se nos recuerda esa sentencia vertida por Nietzsche (8) que rezaba así: “Mirémonos de frente: Somos hiperbóreos”. Y es que resulta esencial ser conscientes de que nuestro Sacro Imperio no será nunca un imperio cosmopolita ni mundialista sino un Imperio cimentado en un hombre concreto, el hombre descendiente de los indoeuropeos de antaño. De los indoeuropeos que vivieron acorde a los parámetros propios del Mundo de la Tradición y que eran portadores de una manera determinada de concebir el Hecho Trascendente que en poco o nada se asemejaba a la que sostenían (y sostienen) otros grupos antropológicos para los cuales no vemos propio el tipo de Imperio Sacro objeto de nuestro estudio y objeto del proyecto presentado en el trabajo que estamos teniendo a bien prologar.

No se trata, en consecuencia, de aspirar a edificar un Imperio sobre una basa inconcreta. No se trata de construir un Imperio sobre el hombre abstracto que el liberal-individualismo ha excretado. No sobre un hombre vaciado de contenido, sin identidad ni referentes. No sobre un hombre intercambiable por cualquier otro del Planeta. No sobre un individuo atomizado sino sobre un hombre concreto, con cara y ojos. Así, leemos en el artículo 14º del Capítulo II del 2º Protocolo que “el Sacro Imperio (…) busca integrar a los pueblos europeos en un solo concepto sagrado sobre la base de la Tradición ancestral y de la identidad étnica.”

Los indoeuropeos de antaño eran, a su vez, los descendientes de los hiperbóreos (o pueblos boreales) aludidos por Nietzsche.

Para una óptima comprensión, de parte del lector, de este origen hiperbóreo de las gentes indoeuropeas no creemos que esté de más el reproducir algunos fragmentos de nuestro “Prólogo a Rivolta contro il mondo moderno”, tales como los que siguen:

“El mito y las tradiciones y textos sacros nos hablan de un cataclismo, en forma de inhóspita glaciación, que asoló de manera especialmente cruda las latitudes septentrionales de la Tierra. Se trataría del final del benigno -climáticamente hablando- período interglacial propio del geológico pleistoceno. Dichos textos correlacionan -y hacen derivar- esa catástrofe con una caída espiritual de nivel que se habría, pues, reflejado, exteriormente, en la irrupción de esas terribles heladas. Como consecuencia de ellas los hombres boreales hubieron de abandonar su hogar circumpolar y desplazarse hacia el sur, estableciéndose en tierras del norte de Europa y, posteriormente (una vez ya finiquitado el pleistoceno y, por tanto, discurriendo el holoceno -la etapa geológica postglacial por la que, a día de hoy, seguimos transitando) descendiendo hacia el centro de la Península Escandinava, dando, entonces, origen al urheimat -o lugar originario-indoeuropeo. A partir de este momento ya sí se puede hablar de este tronco antropológico y de su correspondiente lengua (el indoeuropeo originario). Este pueblo se desplaza algo más hacia el sur de la actual Suecia dando forma, ya en el llamado Neolítico, a la cultura de Ertebolle-Ellenberck, que es considerada como la vagina gentum de los pueblos indoeuropeos, esto es, la cultura y el enclave a partir de los cuales estos pueblos se irán diversificando y desplazando hacia destinos geográficos diversos. Así, también hacia el sur de la actual Suecia florecería la ‘cultura de los vasos de embudo’, para posteriormente, continuando con estos flujos de poblaciones indoeuropeas, constituirse -hacia zonas no alejadas del Mar del Norte y, sobre todo, del mar Báltico- la ‘cultura de los vasos globulares’ y, tras ésta, la de la ‘cerámica cordada’; también conocida como la del ‘hacha de doble filo’. Siguiendo, desde su original enclave escandinavo, esa diagonal de la que nos habla Evola llegan a tierras de la actual Ucrania y, aquí, aparece la ‘cultura de los Kurganes’ o de los ‘túmulos’ (por ser en lo alto de éstos donde se depositaban en urnas las cenizas de los fallecidos). Posteriormente arribarán donde hoy en día se halla Irán y se constituirá la cultura irania, de cuya concepción del Hecho Trascendente representa insuperable testimonio su libro sagrado: el Avesta; del cual ya mencionamos su descripción estacional, fenomenológica y/o climática del hogar en el que se vivió la Edad de Oro y que no pudo ser otro que el polar y circumpolar de nuestro planeta …certidumbre que también se corrobora en los Vedas de esa India que igualmente alcanzaron después las gentes indoeuropeas; o, ya allí, indoarias.

El por algunos denominado como ‘el último gibelino’ -Evola- nos sigue explicando que desde aquellas tierras del norte de Europa, desde las que tuvo lugar este movimiento migratorio en diagonal que llega hasta la India, también acaeció, con posterioridad, un segundo flujo en dirección norte-sur encarnado en los aqueos y dorios que encontramos en los orígenes de la civilización griega o en los latinos que fundaron Roma. Asimismo nos habla de que, desde ese emplazamiento del norte europeo, aconteció, bastante después, la tercera y última emigración, también en sentido norte-sur, que sería la de los pueblos germánicos que acabaron, a partir del s. V d. C., invadiendo el Imperio Romano occidental: visigodos, francos, ostrogodos, lombardos, vándalos, suevos,…” (9)

Que el Sacro Imperio está indisociablemente ligado a un concreto tipo antropológico se reafirma en Protocolo VI cuando, en su cuarto artículo, se lee que “creemos en la Tradición Indoeuropea que nos habla del concepto de lo divino y trascendente, nos enseña nuestros principios éticos, nuestras costumbres sociales y nuestros ritos y ceremonias familiares o públicos.”

………………………………………..

En la “Exhortación final” al Protocolo I se nos advierte que si aspiramos a constituir el Sacro Imperio “es tiempo de poner la economía al servicio de la política”. Sólo en la antítesis al Mundo de la Tradición, cual es el mundo moderno, se ha podido la economía erigir en la rectora de la sociedad. La política se ha sojuzgado a ella. El demon de la economía lo anega todo. Las castas que en el Mundo Tradicional se hallaban situadas en las franjas inferiores de la pirámide social se han ido arrogando el papel rector en el mundo moderno. Primero, con la irrupción del capitalismo, fueron los mercaderes los que violentaron el natural ordenamiento jerárquico Tradicional. Más tarde les tocó el turno, al menos sobre el papel, a los proletarios, los cuales, en buena parte del orbe, implantaron regímenes comunistas (o, para ser más exactos, ‘dictaduras del proletariado’). Hoy en día son los financieros, especuladores, usureros y accionistas de las grandes multinacionales los que, a menudo en la sombra, se han erigido en amos y señores del actual mundo globalizado (10).

La sociedad de clases que engendró el liberalcapitalismo ya no estructuraba la sociedad según las diferentes funciones que en ella se desempeñaban sino que lo hacía bajo el criterio estrictamente económico, por lo que esta función económica la copó en su totalidad. Ya no sucedía pues, tal cual era lo consutancial al orden estamental, que el cuerpo social se estructurase en orden a las funciones sacro-dirigente, guerrera y productiva.

Es debido a esta anomalía por lo que se habla en el Artículo 3º del Capítulo I del segundo Protocolo de este proyecto de “La supresión tajante de la sociedad de clases, basada en el poder adquisitivo de los individuos y su reemplazo por una sociedad de rangos, basada en el valor de cada persona en su servicio a la comunidad.”

…………………………………..

Si, después de todo lo dicho, aún a alguien no le ha quedado clara cuál es la jerarquía de valores que debe guiar el establecimiento del Sacro Imperio en la mencionada “Exhortación final” de este primer Protocolo se nos habla de “Convergencia de las ideas nobles, de los espíritus libres, de los corazones puros, de los movimientos rebeldes ante este sistema de cosas, hacia un mundo de justicia y libertad, de renacimiento espiritual, de diversidad étnica y cultural en armonía. Ese mundo podemos construirlo si sabemos unir a Europa con vocación imperial.”

Tras los desarrollos que hemos llevado a cabo queda diáfana la idea de que no se trata de desechar el actual armatoste demoliberal y partitocrático para sustituirlo por algo sin referentes previos, sino que la plutocracia tiene su radical alternativa en formas políticas, económicas y sociales que no deben ser una reedición de otras que hayan existido en otras épocas pero que sí deben compartir semejante cosmovisión y mismos valores que las que rigieron en el Mundo de la Tradición. Por esto se debe ser revolucionario no en el sentido que la modernidad le ha otorgado a este vocablo sino en el de “re-volvere”, retornar a las bases existenciales y axiológicas de la Tradición, tal como se lee en el Artículo 6º del capítulo I del Protocolo II:

“Nos definimos como revolucionarios y con ello queremos decir que pretendemos re-volver el sistema, es decir, volver a poner todas las cosas en su lugar natural y racional.”

…………………………………

Nos resulta grato que en el Protocolo V dedicado a “Heráldica y Vexilografía del Imperio” se elija el águila bicéfala como símbolo imperial, pues su simbolismo tiene esa dimensional terrenal de, tal como se nos explica, “dominar de oriente a occidente” pero también atesora otra de carácter metafísico, parangonable a la caracterización de la importante deidad romana del Janus bifronte, uno de cuyos rostros representaba el solsticio de invierno o renacimiento del Sol Invictus y el otro el solsticio de verano en el que el dicho Sol Invictus se hallaba (y se halla) en su máximo apogeo; siempre teniendo presente que el Sol Invictus simbolizaba, a su vez, el Principio Espiritual.

También nos resulta harto significativo que como emblema se proponga colocar la mencionada águila bicéfala, negra, “sobre escudo blanco que campea en medio de una bandera o estandarte rojo” (artículo 4º del quinto Protocolo), ya que, en un nivel interpretativo de lectura Superior, tal como se nos recuerda en este artículo, “son también estos colores los de la Alquimia tradicional”. (11)

A vueltas con el simbolismo del águila bicéfala seguimos leyendo, en este mismo Protocolo, que “representa por otra parte la potéstas y la auctóritas, es decir, los poderes político y espiritual del Imperio en la línea del gibelinismo medieval”. Tal como era inherente al “Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico, cuya cúspide jerárquica, en la figura del Emperador, aunaba las funciones sacra y temporal (política) como es propio de cualquier ordenamiento Tradicional en el que, por este motivo, el gobernante también ejerce de Pontifex o ´hacedor de puentes´ entre lo terrestre y lo celestial; entre sus súbditos y la Trascendencia.” (12)

En la separación de ambas funciones acaecieron los primeros pasos de la caída que desde el Mundo Tradicional el hombre ha ido padeciendo hasta llegar al marasmo existencial actual: “(…) Esta segunda caída o involución espiritual supuso un mayor alejamiento del hombre con respecto a lo Trascendente y vino aparejada con la separación entre los principios espiritual y temporal y, en consecuencia, entre la autoridad espiritual y la temporal o política. Desaparecieron, pues, la realeza y la aristocracia sacras y de la separación de los atributos espirituales y los temporales aparecieron dos castas autónomas: la sacerdotal (1ª casta) y la regio-aristocrático-guerrera (2ª casta). Esta aristocrático-guerrera quedó desacralizada y la sacerdotal, a su vez, renunció a la vía activa propia del guerrero y perdió, de esta manera, no sólo la vocación hacia la acción exterior sino también la vocación hacia una acción interna que es la única capaz de hacer factible el acometer cualquier intento de transustanciación interior. Renunció, pues, la casta sacerdotal a la Iniciación y, consecuentemente, a la Visión y Conocimiento de lo Absoluto. La casta sacerdotal o bramánica pasó a ocupar la cima de la pirámide social y el poder político quedó delegado en una casta aristocrático-guerrera desacralizada que quedó subordinada a aquélla.” (13)

Por mantenir unidos los atributos sacro y temporal bregó, en una época ya tardía pero como un intento heroico de Restauración del Orden Tradicional, el bando gibelino y por separar ambos se esforzó el güelfo en ese conflicto medieval que tuvo al Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico como adalid del primero y al Papado y a sus aliados como portaestandartes del segundo. El triunfo del güelfismo desacralizó al poder político y, a la postre, a las sociedades por él regidas. Los procesos posteriores ahondan en este alejamiento con respecto al plano Superior de la existencia y conocen del humanismo antropocéntrico renacentista, del racionalismo, de la Ilustración, de las revoluciones liberales y de la irrupción de la democracia capitalista liberal, del comunismo y del actual gregario, nihilista y relativista (hasta la náusea) mundialismo de la Aldea Global postmoderna.

…………………………………………..

A lo largo de este prólogo ha sido nuestro empeño el de afirmar la convicción de que este proyecto Sacro Imperial, inaplazable en estos tiempos de zozobra general que padecemos, debe tener su fundamento en una concepción Trascendente de la existencia. El Imperio será Sacro o no será. Hemos querido aprovechar estas líneas para trazar y delinear algunos de los principios, algunas de las esencias y algunas de las concretizaciones históricas de la Tradición y/o del Imperium, así como algunos de los procesos de decadencia que han llevado desde un Orden Tradicional hasta el presente estado de paroxismo y de resquebrajamiento generalizados. Nuestra posición en pos de bases Espirituales para articular el Imperium se ha visto refrendada sistemáticamente a lo largo de estos Protocolos. Véase, en este sentido, y como colofón a estas nuestras líneas, lo expresado en el Artículo 4º del sexto Protocolo cuando se nos habla de “una religiosidad que nos impulsa a buscar la Verdad desde el misterio de los orígenes hasta el sentido de la vida y nuestra razón de ser en el Universo”; ”misterios de los orígenes” que no son otros que los de nuestros ancestros hiperbóreos que en illo tempore (la Edad de Oro o, de acuerdo a la tradición indoaria, Satya-yuga) fueron portadores de un tipo de Espiritualidad Solar (14) …y “razón de ser en el Universo” que no es otra, por un lado, que la de la conquista heroica de lo Eterno en cada uno de los que puedan, por aptitud y por voluntad, aspirar a ello (o la de la ritualización sacral de cada quehacer cotidiano en aquellos congéneres para los que no esté al alcance la transformación de su ser interior) y “razón de ser en el Universo”, por otro lado, que debe ser la de la de la Restauración de la Tradición perdida: la de la Restauración, en definitiva, del Sacro Imperio.

NOTAS:

- 1“El Imperium a la luz de la Tradición”. Capítulo IV de “Reflexiones contra la modernidad”. Ediciones Camzo. https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2009/02/08/el-imperiu...

- 2. Íbidem

- 3. Cit.

- 4. “A medio camino entre el imperio español (“El Imperio Español”: https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2015/07/08/el-imperio...) y otros de corte eminentemente antitradicional (por lo mercantilista de los mismos), como el caso del imperio británico (que alcanzó su máxima expresión en el s. XIX) o del conocido como imperialismo ´yanqui´ (tan vigente en nuestros días), podríamos situar al de la Francia napoleónica. Y no sólo lo situamos a medio camino por una evidente razón cronológica, sino que también lo hacemos porque a pesar de haber perdido cualquier orientación de carácter espiritual (el laicismo consecuente con la Ilustración y la Revolución Francesa fue una de las banderas que enarboló), a pesar de ello, decíamos, más que motivaciones de naturaleza económica (como es el caso de los citados imperialismos británico y estadounidense), fueron metas políticas las que ejercieron el papel de motor de su impulso conquistador. Metas políticas que no fueron otras que las de exportar, a los países que fue ocupando, las ideas (eso sí, deletéreas y antitradicionales) triunfantes en la Revolución Francesa.”

- 5. “Los hombres y las ruinas”, Julius Evola. Ediciones Heracles.

- 6. “El Tradicionalismo y Julius Evola”: https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2011/02/23/el-tradici...

- 7. “Evola frente al fatalismo”. Capítulo III de “Reflexiones contra la modernidad”. Ediciones Camzo.

https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2010/08/19/evola-fren...

- 8. No querríamos desaprovechar la ocasión para fijar nuestra posición acerca de la obra del filósofo alemán, pues este ejercicio pensamos que puede contribuir a delimitar y configurar, eliminando ciertos equívocos que se pudiesen tener, cuál debe ser el tipo de hombre sobre el cual sustentar el Sacro Imperio y al cual éste debe tener por empeño “engendrar”. Así, decíamos en cierta ocasión que “la tragedia de Nietzsche estriba en haber ignorado el hecho Trascendente. Su Superhombre es aquel ser humano que se ha conseguido desprender de todo tipo de limitaciones, ataduras, ligazones, morales, miedos, fobias y filias, sentimientos, pasiones,… En este momento, una vez limpia y vacía el alma de apegos y condicionamientos, podría aspirar a ir ´llenándola´ de Ser para experimentar una auténtica Transubstanciación interna, para Renacer -Palingénesis- a otra naturaleza verdaderamente Superior, pero como Nietzsche no concibe lo Metafísico su Superhombre se encuentra -tras haber ´vaciado´ su alma- sin puntos de referencia, sin soportes. No tiene puntos de referencia Superiores ni tiene los puntos de referencia inferiores de los que se ha conseguido desapegar y sin los cuales se ha quedado como sin suelo bajo los pies. Se encuentra, pues, en tal situación, ante la nada, ante un vacío que le empuja a una situación dramática.”——————“Nietzsche no concibió el Hecho Trascendente …esa dimensión metafísica y Superior que anida, aletargada (y a la espera de ser despertada por un tipo de hombre diferenciado que se niegue a ser arrastrado por la inercia existencial del mundo moderno) en el interior del ser humano: el Espíritu. El hombre indoeuropeo y su predecesor arcaico-boreal tienen un origen sacro y el darle la espalda a esto es propio de la modernidad (en sus sucesivas fases: incluyendo la fideísta en la cual sólo se mira a lo Alto cual pasivo creyente pero no cual Héroe capaz de conquistar la Inmortalidad a través del Despertar de lo eterno –Atman– que anida en él). Al judeocristianismo Nietzsche acertadamente lo atacó como semilla del nihilismo que ya en su época se vivía pero no lo hizo para rescatar las esencias divinas del hombre indoeuropeo sino (¡y tampoco es poco!) para ayudarle a sacudirse miedos, complejos, sentimientos de culpa y el estigma del pecado que había convertido al homo europaeus en un ser mediatizado, empequeñecido y acomplejado. El siguiente paso que debería de haberse planteado el gran filósofo alemán debería de haber sido éste: una vez descondicionados –ataraxia o apatheia– de ataduras mentales y existenciales hemos de ir en busca de la transustanciación interior –metanoia– y del conocimiento de los planos Suprasensibles y sutiles de la realidad e incluso, después, hemos de ir en busca de la gnosis del Principio Supremo Inmanifestado e Indefinible (el ´motor inmóvil´ aristotélico) que se halla en el origen del mundo manifestado (del cosmos); gnosis que sólo será posible si hemos conseguido actualizar -Despertar- ese Principio Primero –Brahman– en nosotros mismos: así habremos llegado no sólo a la categoría de dioses sino a ser más que un dios (pues las divinidades no son más que esas fuerzas –numina– que forman parte del entramando sutil del cosmos). La culminación de este proceso -la Gran Liberación- representaría el retorno del hombre a su origen sacro perdido con el fin de la Edad de Oro, que nos narró un Hesíodo, y con la irrupción del mundo moderno (cuya etapa más oscura es el presente kali-yuga; y más aún la fase crepuscular de ésta, por las que estamos transitando).”

9. “Prólogo a Rivolta contro il mondo moderno”: https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2017/09/25/prologo-a-...

10. Sobre este proceso de caída y destrucción total de cualquier residuo de Sociedad Tradicional y en el que la economia domina tiránicamente a la política ya comentamos hace algunos años que: “(…) a partir de entonces y a lo largo de esta ‘edad contemporánea’ la 3ª casta se adueñará del poder, salvo en los períodos en los que la 4ª casta (sudras) –la de la ‘mano de obra’- dirija (por lo menos aparentemente) los regímenes políticos comunistas e imponga el llamado Cuarto Estado. Bien es cierto que, tras la caída del comunismo en la Europa Oriental a fines de la década de los ’80 del siglo pasado, hay quien ha considerado, acertadamente, que el clásico mundo del liberal-capitalismo burgués (Tercer Estado impuesto por la 3ª casta) ha sido sustituido por un tipo de vida aún más colectivista, gregaria, amorfa, uniformizada y desarraigada que la impuesta por el marxismo y en la que ya cualquier referente ideológico ha sido enterrado. El único impulso, y referente, que actúa es el económico y las actividades que, avasalladoramente, se imponen son la producción y el consumo desaforados. Mundo sin referentes al igual que sucedía, en la India Tradicional, con aquellos individuos que se hallaban fuera y por debajo del sistema de castas (los ‘sin casta’ o parias) y que le habían dado la espalda a cualquier norma formadora y a cualquier tipo de raigambre: los ‘sin tradición’ y ‘sin linaje’. Individuos que por sus disolventes o deshonrosas conductas habían sido expulsados de sus respectivas castas: ‘los desterrados’. Evola predijo de manera magistral este devenir y al tipo de sociedad que del mismo se derivara la definió como la de la hegemonía del Quinto Estado; y que, sin duda, corresponde al actual modelo planetario de globalización y de homogeneización alienante y desenraizadora.” (“Los Ciclos Heroicos”. Capítulo II de Reflexiones contra la modernidad”: https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2009/02/08/los-ciclos...

11. Sobre las tres fases de las que habla la tradición alquímica comentábamos en cierta ocasión, a propósito de la tesis doctoral elaborada por un amigo nuestro, que:

“El ´más allá celestial´ es asimilable al mundo Superior y es al que se accede una vez el Iniciado ha dominado sus vínculos y pulsiones condicionadores -primarios, psíquicos: sentimentales, emocionales, pasionales,…- y se ha convertido en ´señor de sí mismo´; en el Gran Autarca que apuntaba Julius Evola allá por los años ´20 de la pasada centuria. Una vez superado lo cual (una vez superada la ´obra al negro´ o nigredo de que nos habla la tradición hermético-alquímica) el Iniciado accede, de forma definitiva, al conocimiento del plano sutil metafísico de la Realidad y es capaz, incluso, de activarlo en su fuero interno (sería el equivalente a la ´obra en blanco´ o albedo). Más aún, tras estos logros, puede aspirar a la Gnosis de lo Inmanifestado que se halla más allá incluso del plano sacro-sutil de la realidad y puede, paralelamente, aspirar a Despertar en su mismo interior ese Principio Supremo y Primero Inmanifestado Eterno e Indefinible que anida en él y aspirar, así, a Espiritualizar e Inmortalizar su alma (´obra al rojo´ o rubedo), que ya fue purificada de escorias psíquicas y condicionadoras tras la superación de la nigredo.” (“Reseña de La tradición guerrera de la Hispania céltica”:https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2014/02/22/resena-de-...)

12. “Evola frente al fatalismo”. Capítulo III de “Reflexiones contra la modernidad”, Ediciones Camzo: https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2010/08/19/evola-fren...

13. “Los Ciclos Heroicos”. Capítulo II de Reflexiones contra la modernidad”, Ediciones Camzo: https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2009/02/08/los-ciclos...

- Con el objeto de no airear términos sin dotarlos de contenido queremos comentar que cuando manejamos el de Solar lo hacemos en el sentido en el que en su día escribimos para hablar de los primordiales indoeuropeos:

“Raza portadora de un tipo de espiritualidad y de una cosmovisión solar-uránica, olímpica (inmutable, serena, sobria), viril, patriarcal, ascendente, vertical, jerárquica, diferenciadora, ordenada y ordenadora, heroica (en el ámbito del carácter y en el sentido del que lucha por reconquistar la divinidad, la inmortalidad que se encontraba en estado latente, casi olvidada, en su interior),… Representativa, dicha cosmovisión, de lo que Evola definió como Luz del Norte.”

Para más ahondar en el significado de este concepto (‘Luz del Norte’) también, en ocasiones, lo hemos tratado confrontándolo a su vez con su opuesto: el de una ´luz del sur´ de cuyos nefastos influjos deberíamos ser ajenos:

“La denominada como ´luz del norte´ vendría asociada a conceptos como el de la jerarquía, la diferencia, lo vertical, lo solar, lo estable, lo inmutable, lo eterno, lo imperecedero, lo patriarcal y a valores como el honor, el valor, la disciplina, el heroísmo, la fidelidad,… Y, por el contrario, la calificada como ´luz del sur´ abanderaría conceptos como el del igualitarismo, lo uniforme y amorfo, lo horizontal, lo lunar, lo inestable, lo mutable, lo caduco, lo perecedero, lo matriarcal, lo sensual, lo instintivo, lo hedonista, lo concupiscente,…”

Incluso, circunscribiéndonos a un plano psíquico o anímico “podríamos decir que la Luz del Norte contemplaría a aquél que rebosa autocontrol, equilibrio, serenidad, sobriedad, coherencia, prudencia, templanza, medida, discreción, calma,…, mientras que la Luz del Sur iluminaría a los individuos tendentes a lo disoluto y disolvente, al desenfreno, a la inestabilidad, al desequilibrio, a la jarana, a la embriaguez, al desorden referente a hábitos y modo de vida,…” (“Septentrionis Lux”: https://septentrionis.wordpress.com/2009/08/)

Eduard Alcántara

eduard_alcantara@hotmail.com

Les raisons de ce relatif abandon intellectuel sont multiples : mondialisme, faiblesses intellectuelles et historiques chez la grande majorité du personnel politique et l’inventaire de la Révolution est de plus en plus connu… Cela étant, un homme situé à l’extrême gauche de l’échiquier politique républicain n’a pas hésité, tout récemment, à commettre une œuvre dans laquelle il assume se reconnaître dans l’héritage jacobin.(1)

Les raisons de ce relatif abandon intellectuel sont multiples : mondialisme, faiblesses intellectuelles et historiques chez la grande majorité du personnel politique et l’inventaire de la Révolution est de plus en plus connu… Cela étant, un homme situé à l’extrême gauche de l’échiquier politique républicain n’a pas hésité, tout récemment, à commettre une œuvre dans laquelle il assume se reconnaître dans l’héritage jacobin.(1)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Robert Malthus’s essay on population growth is widely known and widely refuted, mostly by commentators who have not read it. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus argued that population growth undermined the achievements which technology had brought and was bringing to human society and ironically had first made that population growth possible. Populations, he wrote, increased faster than the rate of increase in food production necessary to keep pace with the demand for more food. According to Malthus, this discrepancy between supply and demand would lead inevitably to a decline in living standards and to famine. That Malthus’s prediction proved (broadly) not to be the case in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is largely due to the fact that human societies have vastly improved agricultural efficiency and available agricultural land far in excess of the slow growth in food production which Malthus had projected. This improvement in food production to meet the demands of growing populations could only be achieved, and was only achieved, by improved logistics, improved science, and exploiting nature — not only more efficiently, but also more extensively. The fear of famine and outbreaks of famine have continued down to the present day, however, and although Malthus is officially repudiated, his ghost has not been lain to rest. The burden put upon nature incurred by meeting the challenge of the appetites of the human population increase continues to this day. Has Malthus been proved entirely wrong, and is his thesis applicable in relation to challenges other than that of famine?

Robert Malthus’s essay on population growth is widely known and widely refuted, mostly by commentators who have not read it. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus argued that population growth undermined the achievements which technology had brought and was bringing to human society and ironically had first made that population growth possible. Populations, he wrote, increased faster than the rate of increase in food production necessary to keep pace with the demand for more food. According to Malthus, this discrepancy between supply and demand would lead inevitably to a decline in living standards and to famine. That Malthus’s prediction proved (broadly) not to be the case in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is largely due to the fact that human societies have vastly improved agricultural efficiency and available agricultural land far in excess of the slow growth in food production which Malthus had projected. This improvement in food production to meet the demands of growing populations could only be achieved, and was only achieved, by improved logistics, improved science, and exploiting nature — not only more efficiently, but also more extensively. The fear of famine and outbreaks of famine have continued down to the present day, however, and although Malthus is officially repudiated, his ghost has not been lain to rest. The burden put upon nature incurred by meeting the challenge of the appetites of the human population increase continues to this day. Has Malthus been proved entirely wrong, and is his thesis applicable in relation to challenges other than that of famine?

Another highly interesting factor highlighted in this book is the notion of the sanctity of life. From the end of the Roman Empire to the sixteenth century, Europe did not experience a dramatic increase in population nor did it experience a birth rate anything like as high as that which began suddenly at the end of the fifteenth century and continued down to the twentieth century. What had happened? According to Heinsohn, the notion of the “sanctity of life” and hostility towards contraception, infanticide, and abortion of an intensity not seen since the days of Rome (but highly characteristic of Islamic society) began at the end of the fifteenth century — and it is at the end of the fifteenth century that Europe set out on a course of world conquest. The writer refers to well-documented evidence from several English counties. On the basis of this evidence, between 1441 and 1465, 100 fathers were leaving 110 surviving sons. Between 1491 and 1505 a dramatic change had taken place: 100 fathers were leaving behind them 202 surviving sons. By the nineteenth century, between 5 and 6.5 children per mother were being raised in Europe, a rate only reached in the last century by twenty-four states in Sub-Saharan Africa and Afghanistan.

Another highly interesting factor highlighted in this book is the notion of the sanctity of life. From the end of the Roman Empire to the sixteenth century, Europe did not experience a dramatic increase in population nor did it experience a birth rate anything like as high as that which began suddenly at the end of the fifteenth century and continued down to the twentieth century. What had happened? According to Heinsohn, the notion of the “sanctity of life” and hostility towards contraception, infanticide, and abortion of an intensity not seen since the days of Rome (but highly characteristic of Islamic society) began at the end of the fifteenth century — and it is at the end of the fifteenth century that Europe set out on a course of world conquest. The writer refers to well-documented evidence from several English counties. On the basis of this evidence, between 1441 and 1465, 100 fathers were leaving 110 surviving sons. Between 1491 and 1505 a dramatic change had taken place: 100 fathers were leaving behind them 202 surviving sons. By the nineteenth century, between 5 and 6.5 children per mother were being raised in Europe, a rate only reached in the last century by twenty-four states in Sub-Saharan Africa and Afghanistan. It is worth noting the paradox that only does the white race have far fewer children per capita than other races, but those who are most conscious of the demographic decline and most readily deplore it themselves usually have few or no children at all.

It is worth noting the paradox that only does the white race have far fewer children per capita than other races, but those who are most conscious of the demographic decline and most readily deplore it themselves usually have few or no children at all. It is fourteen years since the renowned philosopher Peter Sloterdijk opined enthusiastically in the pages of the Kölner Stadt Anzeiger that Söhne und Weltmacht would become required reading for politicians and journalists. His prediction has not been fulfilled, and this new and updated edition has been published by a small Swiss imprint. The fact is that books like Söhne und Weltmacht cannot expect to receive much attention from journalists or politicians. They point to truths which the presently-dominating ideology is loathe to review or discuss.

It is fourteen years since the renowned philosopher Peter Sloterdijk opined enthusiastically in the pages of the Kölner Stadt Anzeiger that Söhne und Weltmacht would become required reading for politicians and journalists. His prediction has not been fulfilled, and this new and updated edition has been published by a small Swiss imprint. The fact is that books like Söhne und Weltmacht cannot expect to receive much attention from journalists or politicians. They point to truths which the presently-dominating ideology is loathe to review or discuss.

Son nouvel ouvrage, Devant l’effondrement, ne peut que déplaire aux hiérarques d’Europe Écologie – Les Verts (EE-LV) et à leurs potentiels électeurs bo-bo prêt à tout pour sombrer une nouvelle fois dans l’hédonisme « éthique ». Avec cet « essai de collapsologie », Yves Cochet « avoue avoir rédigé cet ouvrage d’une main tremblante (p. 120) ». Son propos sciemment pessimiste contrarie les desseins merveilleux d’EE – LV au moment où leurs homologues autrichiens et bientôt allemands gouvernent et vont gouverner en partenariat avec les conservateurs chrétiens-démocrates. Il s’agace du réformisme radieux qui émane de son parti. « Collés à l’actualité, obsédés par la rivalité pour les places – comme dans les autres partis, en somme -, la quasi-totalité des animateurs Verts se bornent à décliner les clichés rassurants du développement durable, aujourd’hui renommé “ Green New Deal ” ou “ transition écologique ” (p. 221). »

Son nouvel ouvrage, Devant l’effondrement, ne peut que déplaire aux hiérarques d’Europe Écologie – Les Verts (EE-LV) et à leurs potentiels électeurs bo-bo prêt à tout pour sombrer une nouvelle fois dans l’hédonisme « éthique ». Avec cet « essai de collapsologie », Yves Cochet « avoue avoir rédigé cet ouvrage d’une main tremblante (p. 120) ». Son propos sciemment pessimiste contrarie les desseins merveilleux d’EE – LV au moment où leurs homologues autrichiens et bientôt allemands gouvernent et vont gouverner en partenariat avec les conservateurs chrétiens-démocrates. Il s’agace du réformisme radieux qui émane de son parti. « Collés à l’actualité, obsédés par la rivalité pour les places – comme dans les autres partis, en somme -, la quasi-totalité des animateurs Verts se bornent à décliner les clichés rassurants du développement durable, aujourd’hui renommé “ Green New Deal ” ou “ transition écologique ” (p. 221). »

Si Yves Cochet oppose trois modèles : le productiviste, l’augustinien et le modèle discontinuiste qui « pourrait être compatible avec l’un et l’autre, puisqu’il se focalise surtout sur la forme de l’évolution du monde, et non sur sa substance (p. 55) », on remarque qu’il se réfère à un sermon de Saint-Augustin de décembre 410 qui aurait inspiré Oswald Spengler et le vitalisme civilisationnel… Suite aux travaux précurseurs de Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen et à la prise en compte de la non-linéarité des systèmes complexes, il distingue l’économie biophysique de l’économie écologique qui « tente d’évaluer le prix des services des écosystèmes en intégrant la finitude des ressources et la pollution dans le cadre de l’économie néo-classique (p. 73) ». À l’économie néo-classique, il propose l’« économie biophysique [qui] se concentre explicitement sur les relations de puissance, à la fois dans le sens physique d’énergie par unité de temps et dans le sens social de contrôle sur les autres (p. 71) ». À la jonction des sciences exactes et des sciences humaines, l’économie biophysique se base « sur les stocks et les flux de matière et d’énergie plutôt que sur les comportements individuels (les “ préférences des consommateurs ”). L’accent est mis sur la qualité de l’énergie, ainsi que sur la quantité d’énergie disponible (p. 71) ». Il parie que « l’économie biophysique, qui envisage un monde au climat déréglé et à l’énergie rare, est une meilleure base d’orientation pour la construction d’une société soutenable que les formes individualiste et croissanciste de la théorie économique néo-classique (p. 91) » parce que « plutôt que de prendre la rareté relative comme point de départ, [elle] se concentre sur le surplus économique et la pénurie absolue (p. 86) ».

Si Yves Cochet oppose trois modèles : le productiviste, l’augustinien et le modèle discontinuiste qui « pourrait être compatible avec l’un et l’autre, puisqu’il se focalise surtout sur la forme de l’évolution du monde, et non sur sa substance (p. 55) », on remarque qu’il se réfère à un sermon de Saint-Augustin de décembre 410 qui aurait inspiré Oswald Spengler et le vitalisme civilisationnel… Suite aux travaux précurseurs de Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen et à la prise en compte de la non-linéarité des systèmes complexes, il distingue l’économie biophysique de l’économie écologique qui « tente d’évaluer le prix des services des écosystèmes en intégrant la finitude des ressources et la pollution dans le cadre de l’économie néo-classique (p. 73) ». À l’économie néo-classique, il propose l’« économie biophysique [qui] se concentre explicitement sur les relations de puissance, à la fois dans le sens physique d’énergie par unité de temps et dans le sens social de contrôle sur les autres (p. 71) ». À la jonction des sciences exactes et des sciences humaines, l’économie biophysique se base « sur les stocks et les flux de matière et d’énergie plutôt que sur les comportements individuels (les “ préférences des consommateurs ”). L’accent est mis sur la qualité de l’énergie, ainsi que sur la quantité d’énergie disponible (p. 71) ». Il parie que « l’économie biophysique, qui envisage un monde au climat déréglé et à l’énergie rare, est une meilleure base d’orientation pour la construction d’une société soutenable que les formes individualiste et croissanciste de la théorie économique néo-classique (p. 91) » parce que « plutôt que de prendre la rareté relative comme point de départ, [elle] se concentre sur le surplus économique et la pénurie absolue (p. 86) ».

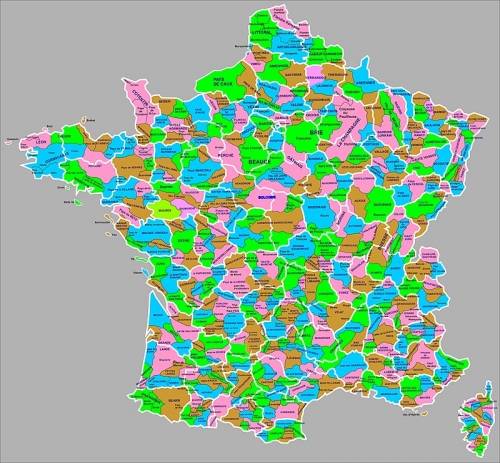

Yves Cochet évacue bien trop rapidement la violence humaine. La grève contre la réforme des retraites déclenchée le 5 décembre 2019 a déjà démontré la sauvagerie sous-jacente des Franciliens et des Parisiens qui essayaient de monter dans le seul train de banlieue ou dans l’unique rame de métro. Certains n’hésitèrent pas à se battre. Et ne parlons pas des rapports conflictuels en ville entre piétons, automobilistes, cyclistes, patineurs à roulettes et « trottinettistes ». Cette agressivité propre à la nature humaine, accentuée par la modernité tardive pourrait atteindre rapidement son paroxysme au moment de l’effondrement social. La vie en zone urbaine après la « Grande Déflagration » sera certainement plus difficile que dans la France périphérique déjà habituée aux privations. « Il faudra réapprendre à maîtriser une agro-écologie alimentaire, énergétique et productrice de fibres pour les vêtements, cordes et papiers, la production de matériaux de construction indigènes, voire la fabrication de quelques substances secondaires, mais utiles, telles que l’alcool, l’ammoniac, la soude, la chaux… Tous ces domaines étant équipés en outils low tech aptes à êtres fabriqués, entretenus et réparés par des ouvriers locaux (p. 118). » En pratique, on utilisera le bois de chauffage, le charbon de bois et les biogaz dont le méthane.

Yves Cochet évacue bien trop rapidement la violence humaine. La grève contre la réforme des retraites déclenchée le 5 décembre 2019 a déjà démontré la sauvagerie sous-jacente des Franciliens et des Parisiens qui essayaient de monter dans le seul train de banlieue ou dans l’unique rame de métro. Certains n’hésitèrent pas à se battre. Et ne parlons pas des rapports conflictuels en ville entre piétons, automobilistes, cyclistes, patineurs à roulettes et « trottinettistes ». Cette agressivité propre à la nature humaine, accentuée par la modernité tardive pourrait atteindre rapidement son paroxysme au moment de l’effondrement social. La vie en zone urbaine après la « Grande Déflagration » sera certainement plus difficile que dans la France périphérique déjà habituée aux privations. « Il faudra réapprendre à maîtriser une agro-écologie alimentaire, énergétique et productrice de fibres pour les vêtements, cordes et papiers, la production de matériaux de construction indigènes, voire la fabrication de quelques substances secondaires, mais utiles, telles que l’alcool, l’ammoniac, la soude, la chaux… Tous ces domaines étant équipés en outils low tech aptes à êtres fabriqués, entretenus et réparés par des ouvriers locaux (p. 118). » En pratique, on utilisera le bois de chauffage, le charbon de bois et les biogaz dont le méthane.

Der Nachlass Carl Schmitts ist eine reiche Quelle. Fast wundert es aber, dass er so reichlich sprudelt. Denn seine Edition wurde nicht generalstabsmäßig geplant. Das lag auch an Schmitt selbst. Zwar entwickelte der zahlreiche interpretative Strategien im Umgang mit seiner Rolle und seinem Werk. Anders als etwa Heidegger organisierte er aber seine posthume Überlieferung nicht im großen Stil. Er betrieb keine Fusion von Nachlassinterpretationspolitik und Nachlasseditionspolitik, bei der interpretative Strategien kommenden Editionen vorarbeiteten. Initiativen zu einer großen Werkausgabe scheiterten deshalb auch nach Schmitts Tod. Damals wurde eine Chance vertan, denn personell und institutionell haben sich die Bedingungen nicht verbessert. Schmitts letzte Schülergeneration, die „dritte“ Generation bundesdeutscher Schüler (Böckenförde, Schnur, Quaritsch, Koselleck etc.), tritt ab und den Institutionen geht das Geld aus. Heute ist keine historisch-kritische Gesamtausgabe in Sicht. Die Zukunft ist solchen Projekten auch nicht rosig. Das gerade erschienene Berliner „Manifest Geisteswissenschaften“ etwa, ein revolutionäres Dokument der „Beschleunigung wider Willen“, plädiert für eine Überführung akademischer Langzeitvorhaben in „selbständige Editionsinstitute“.

Der Nachlass Carl Schmitts ist eine reiche Quelle. Fast wundert es aber, dass er so reichlich sprudelt. Denn seine Edition wurde nicht generalstabsmäßig geplant. Das lag auch an Schmitt selbst. Zwar entwickelte der zahlreiche interpretative Strategien im Umgang mit seiner Rolle und seinem Werk. Anders als etwa Heidegger organisierte er aber seine posthume Überlieferung nicht im großen Stil. Er betrieb keine Fusion von Nachlassinterpretationspolitik und Nachlasseditionspolitik, bei der interpretative Strategien kommenden Editionen vorarbeiteten. Initiativen zu einer großen Werkausgabe scheiterten deshalb auch nach Schmitts Tod. Damals wurde eine Chance vertan, denn personell und institutionell haben sich die Bedingungen nicht verbessert. Schmitts letzte Schülergeneration, die „dritte“ Generation bundesdeutscher Schüler (Böckenförde, Schnur, Quaritsch, Koselleck etc.), tritt ab und den Institutionen geht das Geld aus. Heute ist keine historisch-kritische Gesamtausgabe in Sicht. Die Zukunft ist solchen Projekten auch nicht rosig. Das gerade erschienene Berliner „Manifest Geisteswissenschaften“ etwa, ein revolutionäres Dokument der „Beschleunigung wider Willen“, plädiert für eine Überführung akademischer Langzeitvorhaben in „selbständige Editionsinstitute“.

Breizh-info.com :

Breizh-info.com :

Pierre-Antoine Plaquevent : Shahin Vallée travaille depuis 2015 pour le Soros Fund Management sur les questions économiques et monétaires dans la zone euro. Shahin Vallée (dont le nom et le parcours rappellent un peu le « Mustapha Meunier » du livre Le Meilleur des Mondes d’Aldous Huxley) fût conseiller économique d’Herman Van Rompuy puis celui d’Emmanuel Macron quand celui-ci était ministre de l’Économie. « Homme pressé » aux multiples activités, Shahin Vallée fût aussi conseiller d’Europe Écologie les Verts. Comme George Soros avant lui, il est un élève de la London School of Economics, cette pouponnière de l’élite de l’anglosphère qui fût fondée en 1895 par plusieurs membres de la célèbre Société fabienne (Fabian Society). Shahin Vallée fût celui par qui le contact entre LREM et le Mouvement 5 étoiles continuait de se maintenir lors des tractations entre la Lega de Matteo Salvini et le M5s en 2018. Le but de la stratégie Macron-Shahin était alors de ne pas se couper des éléments européistes et globalistes du M5s. Cette stratégie s’avérera payante puisque le M5s bloquera systématiquement les actions de Salvini poussant ce dernier à faire exploser la coalition alors au pouvoir afin d’obtenir des élections en août dernier. Action qui s’est soldée par l’échec du pari de Salvini et par la constitution d’un gouvernement Parti Démocrate / Mouvement 5 Étoiles comme le souhaitaient le couple Macron / Shahin Vallée.

Pierre-Antoine Plaquevent : Shahin Vallée travaille depuis 2015 pour le Soros Fund Management sur les questions économiques et monétaires dans la zone euro. Shahin Vallée (dont le nom et le parcours rappellent un peu le « Mustapha Meunier » du livre Le Meilleur des Mondes d’Aldous Huxley) fût conseiller économique d’Herman Van Rompuy puis celui d’Emmanuel Macron quand celui-ci était ministre de l’Économie. « Homme pressé » aux multiples activités, Shahin Vallée fût aussi conseiller d’Europe Écologie les Verts. Comme George Soros avant lui, il est un élève de la London School of Economics, cette pouponnière de l’élite de l’anglosphère qui fût fondée en 1895 par plusieurs membres de la célèbre Société fabienne (Fabian Society). Shahin Vallée fût celui par qui le contact entre LREM et le Mouvement 5 étoiles continuait de se maintenir lors des tractations entre la Lega de Matteo Salvini et le M5s en 2018. Le but de la stratégie Macron-Shahin était alors de ne pas se couper des éléments européistes et globalistes du M5s. Cette stratégie s’avérera payante puisque le M5s bloquera systématiquement les actions de Salvini poussant ce dernier à faire exploser la coalition alors au pouvoir afin d’obtenir des élections en août dernier. Action qui s’est soldée par l’échec du pari de Salvini et par la constitution d’un gouvernement Parti Démocrate / Mouvement 5 Étoiles comme le souhaitaient le couple Macron / Shahin Vallée.

Autre terrain d’influence majeure : la justice. Au travers de l’Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI), les réseaux Soros fournissent un appui financier à de nombreuses initiatives d’ingérence dans le système judiciaire français. Par exemple dans le financement d’études sur les contrôles de police au faciès. Ainsi le programme « Profiling Minorities. A Study of Stop-and-Search Practices in Paris » réalisé en 2009 avec le soutien du CNRS. Il s’agit comme toujours d’utiliser des cas d’abus de pouvoir ou d’arbitraire policier afin de s’immiscer au sein des institutions d’un État et d’y faire de l’ingérence.

Autre terrain d’influence majeure : la justice. Au travers de l’Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI), les réseaux Soros fournissent un appui financier à de nombreuses initiatives d’ingérence dans le système judiciaire français. Par exemple dans le financement d’études sur les contrôles de police au faciès. Ainsi le programme « Profiling Minorities. A Study of Stop-and-Search Practices in Paris » réalisé en 2009 avec le soutien du CNRS. Il s’agit comme toujours d’utiliser des cas d’abus de pouvoir ou d’arbitraire policier afin de s’immiscer au sein des institutions d’un État et d’y faire de l’ingérence.

Pierre-Antoine Plaquevent : Je ne crois pas, je pense plutôt que l’étude des réseaux, de l’action et de la pensée d’un George Soros est en fait un point d’entrée dans ce monde opaque et très fermé que Michel Geoffroy appelle «

Pierre-Antoine Plaquevent : Je ne crois pas, je pense plutôt que l’étude des réseaux, de l’action et de la pensée d’un George Soros est en fait un point d’entrée dans ce monde opaque et très fermé que Michel Geoffroy appelle «

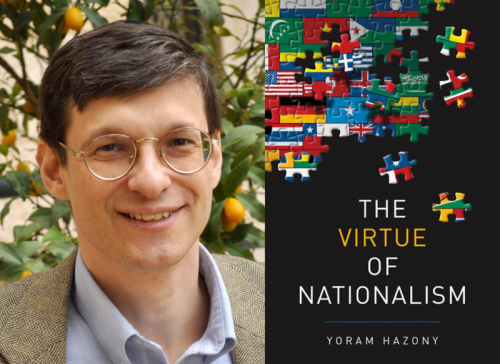

Cette ligne de fracture traverse tout l’Occident contemporain et voit se confronter juifs de gauche internationalistes, cosmopolites et sorosiens face aux juifs de droite conservateurs et sionistes. Dans un article au titre explicite («

Cette ligne de fracture traverse tout l’Occident contemporain et voit se confronter juifs de gauche internationalistes, cosmopolites et sorosiens face aux juifs de droite conservateurs et sionistes. Dans un article au titre explicite («

En su elaboración se han tocado, a nuestro parecer, todas las teclas que se debían de tocar: desde las bases socio-políticas en que deberá asentarse esa nueva Europa, que no soslaya cuál será su organización territorial-administrativa, pasando por la geoestrategia que deberá hacer propia, continuando por hasta cuál será la heráldica que deberá representarlo y acabando por tratar la que deberá ser su posición en el tema de la Trascendencia.

En su elaboración se han tocado, a nuestro parecer, todas las teclas que se debían de tocar: desde las bases socio-políticas en que deberá asentarse esa nueva Europa, que no soslaya cuál será su organización territorial-administrativa, pasando por la geoestrategia que deberá hacer propia, continuando por hasta cuál será la heráldica que deberá representarlo y acabando por tratar la que deberá ser su posición en el tema de la Trascendencia.

Cependant, Brice Couturier reconnaît volontiers que le libéralisme de gauche présidentiel se mêle à d’autres influences politiques. Il s’attarde d’ailleurs volontiers sur la formation intellectuelles du huitième président de la Ve République, son « chemin de culture, une Bildung, comme disent les Allemands. Car la pensée de Macron s’est élaborée au cours d’études assez inhabituelles chez nos dirigeants (p. 43) ». Le futur chef de l’État « a raté à deux reprises le concours d’entrée de l’École normale supérieure alors que, reçu au bac avec la mention “ Très bien ”, il avait été admis à l’une des khâgnes les plus prestigieuses de France, celle du lycée Henri-IV (p. 50) ». « Avant de s’inscrire à Sciences Po, poursuit Brice Couturier, il avait suivi des cours de philosophie à l’université de Nanterre (p. 52). » Le futur Macron apprécie alors de souvent citer Hegel au point qu’il peut être qualifié d’« hégélien de gauche ». Il consacre « son mémoire de DEA (travail de 3e cycle universitaire qui donne l’autorisation de poursuivre son doctorat) à La Raison dans l’Histoire de Hegel (p. 60) » en 2001. Il avait l’année précédente « rédigé son mémoire de maîtrise, consacré à Machiavel (p. 233) » sous la direction d’Étienne Balibar. Brice Couturier en déduit que « Macron dispose d’une colonne vertébrale théorique impressionnante. Sa pensée est structurée. Elle vient de loin (p. 36) ».

Cependant, Brice Couturier reconnaît volontiers que le libéralisme de gauche présidentiel se mêle à d’autres influences politiques. Il s’attarde d’ailleurs volontiers sur la formation intellectuelles du huitième président de la Ve République, son « chemin de culture, une Bildung, comme disent les Allemands. Car la pensée de Macron s’est élaborée au cours d’études assez inhabituelles chez nos dirigeants (p. 43) ». Le futur chef de l’État « a raté à deux reprises le concours d’entrée de l’École normale supérieure alors que, reçu au bac avec la mention “ Très bien ”, il avait été admis à l’une des khâgnes les plus prestigieuses de France, celle du lycée Henri-IV (p. 50) ». « Avant de s’inscrire à Sciences Po, poursuit Brice Couturier, il avait suivi des cours de philosophie à l’université de Nanterre (p. 52). » Le futur Macron apprécie alors de souvent citer Hegel au point qu’il peut être qualifié d’« hégélien de gauche ». Il consacre « son mémoire de DEA (travail de 3e cycle universitaire qui donne l’autorisation de poursuivre son doctorat) à La Raison dans l’Histoire de Hegel (p. 60) » en 2001. Il avait l’année précédente « rédigé son mémoire de maîtrise, consacré à Machiavel (p. 233) » sous la direction d’Étienne Balibar. Brice Couturier en déduit que « Macron dispose d’une colonne vertébrale théorique impressionnante. Sa pensée est structurée. Elle vient de loin (p. 36) ».