Jérôme Fourquet is a mainstream pollster with the venerable French Institute of Public Opinion (IFOP), the nation’s leading polling agency. He made a splash last year with his book, The French Archipelago: The Birth of a Multiple and Divided Nation, which presented a fine-grain statistical analysis of socio-cultural changes in French society and, in particular, fragmentation along ethno-religious and educational lines.

The book persuasively makes case that the centrist-globalist Emmanuel Macron’s election to the presidency and the collapse of the traditional parties of government in 2017 were not freak events, but the reflection of long-term trends which finally expressed themselves politically. The same can be said for the growing popularity of anti-establishment movements like Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (RN) and the yellow-vests.

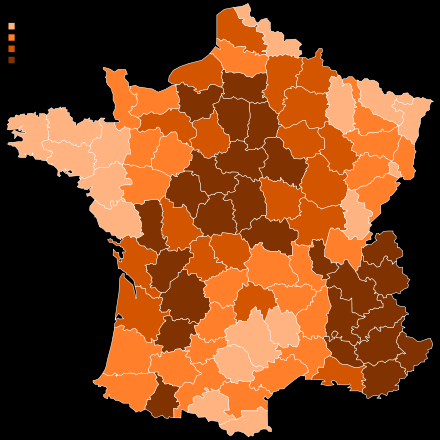

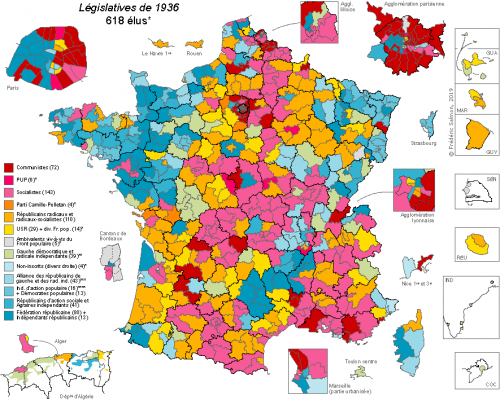

Following the works of many sociologists and historians, Fourquet sees French politics as historically divided between a Catholic Right and secularist Left. This divide had been highly stable since the French Revolution, if not earlier, with a dechristianizing core stretching out from the greater Parisian basin into the Limousin, with most of the periphery remaining relatively conservative. These subcultures united people of different classes within particular regions and corresponded politically with the conservative and Socialist parties who have taken turns governing France since World War II.

Since 1945, the collapse of Catholicism and the steady cognitive/economic stratification of French society have destroyed the reach and unity of the Catholic-right and secularist-left blocs. Macron was able to tap into the latent political demand of the wealthiest, most educated, and mobile 20% of French society, while the increasingly alienated and déclassés lower classes of French Whites have been falling out of the mainstream political system altogether.

Fourquet meticulously documents the social trends of the past 70 years: the decline of Catholicism, the Communist Party, and traditional media, the triumph of social liberalism, the division of cities into gentrified areas, crime-ridden ghettos, and the (self-)segregation of individuals along educational and ethnic lines. In all this, Fourquet’s book serves as an excellent statistical companion piece to Éric Zemmour’s Le Suicide français, which looks at many of the same themes through the lens of political and cultural events.

What’s in a first name? Quite a lot, actually

Fourquet uses a wealth of socio-economic and polling data to make his case. Some of the most innovative and striking evidence however is the big-data analysis of first names in France’s birth registries since 1900. This looks into the trends for numerous different types of names: Christian, patriotic, regional (Breton and Corsican), Muslim, African, and . . . Anglo. Far from being random, Fourquet shows that the trends in first-name giving correlate with concurrent social and political phenomena. For example, the number of people giving their girls patriotic names like France and Jeanne spiked during moments of nationalist fervor, namely the first and second world wars (p. 35).

More significantly, Marie went from being the most common name for girls (20% of newborns in 1900) to 1-2% since the 1970s. Unsurprisingly given the Virgin Mary’s importance in the Catholic religion, Marie was more popular in more religious regions and declined later in the conservative periphery. Marie’s decline thus seems to be a solid temporal and geographical marker of dechristianization (mass attendance and traditional Christian values, such as marriage and opposition to abortion and gay marriage, also collapsed during this period).

First names also provide a marker for assimilation of immigrant groups. Fourquet shows how Polish first names exploded in the northern mining regions of France in the 1920s and then fully receded within two decades. He shows the same phenomenon for Portuguese immigrants and first names in the 1970s. This assimilation is in accord with sociological data showing that European immigrants tend to rapidly converge in terms of educational and economic performance with the native French population.

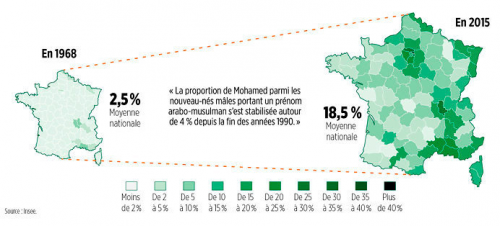

By contrast, Fourquet shows that people with Muslim last names almost never choose to give their children traditional French first names. He documents a massive increase in the proportion of newborns given Muslim first names from negligible in the 1960s to around a fifth of the total. There is also an increase in the number of people with Sub-Saharan African names.

Somewhat similarly to Europeans, Asian immigrants (disproportionately from the former Indochina) are much more likely to adopt French first names and perform comparably in economic and educational terms.

Beyond these stark ethno-religious demographic changes, Fourquet also highlights more subtle trends that often fall below the radar. First names also provide a marker for the degree to which the French have a common culture or, conversely, of heightened individual or sectoral identities.

Fourquet identifies an explosion in the number of different names used by the French. This figure was stable around 2000 from 1900 to 1945, rising to over 12,000 today. And this does not count the proliferation “rare names” – those for which there are less than 3 people with that name – among all populations. Fourquet takes this as evidence of increased individualism and “mass narcissism,” more and more people wishing to differentiate themselves.

In principle, until recently the French were forced by Napoleonic-era legislation to choose their first names from the Christian calendar, medieval European names, or Greco-Roman antiquity. All of France proper used a common corpus of names, with little local variation. The list of acceptable names was extended by ministerial instruction to regional and mythological names in 1966, while in 1993 the restriction was abolished. However, the trend of more-and-more names in fact long predates these legal changes. Evidently municipal authorities already were tolerating unusual names more and more.

What are the names in question? All sorts. The use of Breton (Celtic) names in Brittany has more tripled from 4% to around 12% (p. 127), with sharp rises corresponding to moments of heightened Breton regionalist politics in the 1970s.

Similarly, Italian-Corsican first names have risen from virtually nil in the 1970s to 20% of Corsican newborns today, coinciding with the rise of the Corsican nationalist vote on the island to 52.1% in 2017 (p. 130). Corsican nationalism has risen despite the fact that use of the French language has largely supplanted the Corsican dialect. Many Corsicans resent colonization both by wealthy metropolitan French buying up properties on the fair isle and by Afro-Islamic immigrants.

There has also been a steady increase of the use of markedly Jewish first names like Ariel, Gad, and Ephraïm – which were virtually unheard of in 1945 (p. 213)

One of the most intriguing trends is the proliferation of Anglo first names from a mere 0.5% of newborns in the 1960s to 12% in 1993, today stabilized around 8% (p. 120). Names like Kevin, Dylan, and Cindy became extremely popular, evidently influenced by American pop stars and soap operas (The Young and the Restless was a big hit in France under the title Les Feux de l’Amour). Significantly, Anglo names are more popular among the lower classes, going against the previous trend of French elites setting top-down fashion trends for names. Indeed, many yellow-vest and RN cadres in France have conspicuously (pseudo-)Anglo first names, such as Steeve [sic] Briois (mayor of the northern industrial city of Hénin-Beaumont), Jordan Bardella (RN youth leader and lead candidate in the 2019 EU parliamentary elections), and Davy Rodriguez (youth deputy leader).

A fragmented France: Globalists, populists, and Muslims

Fourquet sees France as an “archipelago” of subcultures diverging from one another. Among these: Macron-supporting educated metropolitan elites, the remaining rump of practicing Catholics (6-12% of the population), conservative-supporting retirees, expats outside of France (whose numbers have more than tripled to around 1.3 million since 2002), alienated lower-class suburban and rural Whites (often supporting the yellow-vests and/or Marine Le Pen), and innumerable ethnic communities, mostly African or Islamic, scattered across France’s cities.

The French are less and less united by common schools, media, and life experiences. The fifth or so of most educated, wealthy, and deracinated French finally manifested politically with Macron’s triumph in 2017. But will these other subcultures become politically effective? Fourquet concludes that

Thus, over the past 30 years, many islands of the French archipelago are becoming politically autonomous and obey less and less the commands of the capital-island and its elites. Though indeed the scenario in which the [subculturally] most distant islands or provinces would declare their independence does not seem to be on the order of the day. (pp. 378-79)

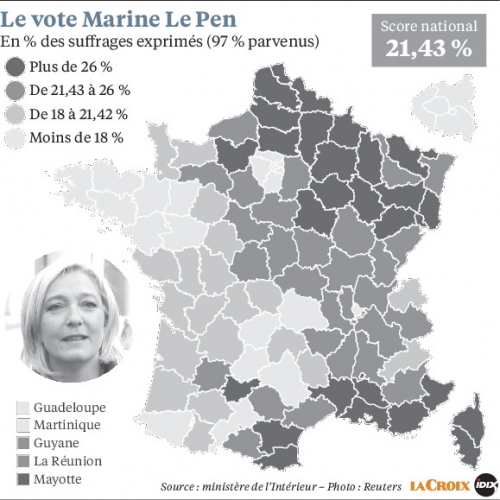

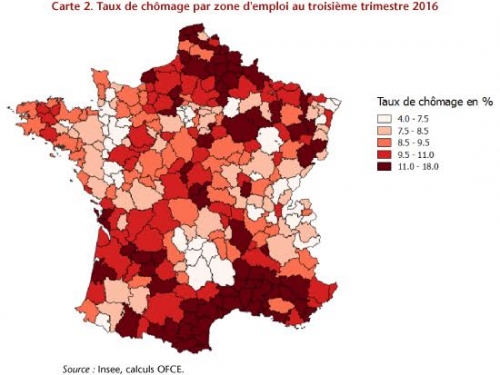

Still, we can see major subcultural blocs consolidating. In the immediate, the most important is the vast suburban and rural bloc of alienated Whites. Support for Marine Le Pen correlates with distance from city-centers, the presence of Afro-Islamic immigrants (until these overwhelm the natives), and/or chronic unemployment. Fourquet says that “the yellow-vest movement has been particularly revealing not only of the process of archipelization underway but also of the peripheries’ inability to threaten the heart of the French system” (379). It seems probable the bloc of alienated Whites will continue to grow and develop politically.

The White “popular bloc” is not coherent politically but is basically entropic. The yellow-vests, themselves not an organized group at all, did not so much have a political program but a set of concerns essentially revolving around purchasing power, public services declining areas, and direct democracy. The most clear and political demand of the yellow-vests was the famous Citizen Initiative Referendum (RIC), similar to practices in Switzerland or California. This measure, whatever its merits, is more about means than ends and is entropic as such.

Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, the other great manifestation of this bloc, is characterized by a mix of socialistic civic nationalism and political opportunism. Given the travails of the Brexit and Trump experiences, one wonders how an eventual National Rally administration would or could govern, especially if virtually the entire French educated class would similarly rise in opposition.

The other great emerging bloc(s) is that made up of France’s fast-growing African and Islamic communities. I would have liked more information on this group. There is data indicating that French Muslims are considerably endogamous (most marry within their own ethny, though there is some variation by community). While the French overwhelmingly support abortion and homosexuality, only small majorities of Muslims do, an important marker of limited convergence. He also observes that a significant minority of Muslims are entering the middle and upper classes, and indeed that the more educated a Muslim is the more likely he or she is to be married to a native French.

However, other indicators of “assimilation” have if anything gone into reverse since the early 2000s: more Muslim women are wearing headscarves, Muslim youth are more likely to say sex before marriage is immoral than their elders (75% to 55%), and two thirds of young Muslims support censorship blasphemy and one quarter condones the murder of cartoonists mocking Mohamed. The War on Terror and renewed Arab-Israeli conflict appear to have rekindled Muslim identity in France. What’s more the sheer number of Muslims and the unending flow from the home country appear to be making them more confident in rejecting assimilation.

In the coming decades, we can reasonably expect French society to become polarized between an Afro-Islamic bloc, united by economic interests and ethno-religious grievances, and a middle/lower class White bloc. And I use the word White, rather than native French, advisedly: many prominent French nationalists and their supporters are of Italian, Polish, or Portuguese origin.

To his credit, Fourquet repeatedly emphasizes the scale and unprecedented nature of the ethno-religious changes in the French population. He also discretely observes the potential for conflict, saying of Paris: “This great diversity is the source of tensions (the demographic balance within certain neighborhoods is changing according to the arrival or reinforcement of this or that group)” (p. 377). And then hidden away in a footnote: “In a multiethnic society, the relative weight of different groups becomes a crucial matter, as individuals seek a territory in which their group is the majority or at least sufficiently numerous.” Indeed.

Fourquet concludes:

At the heart of the capital-island [Paris], the elites reassure themselves in the face of their opponents’ impotence. In so doing, they think that they can rely on the traditional exercise of authority without having to draw the consequences of the birth of a France with a new form and new drives: a multiple and divided nation. (p. 379)

This book left me curious, but also unnerved, about the further social transformations in store for our societies, even beyond the ethnic factor. The disturbing trends in France very much have their analogues in other Western nations. White proles – vilified by their own ruling class or left to their own devices – are in sorry shape. Western elites have lost their collective minds. Looking further afield, how will individualism and social fragmentation manifest in other nations, such as Israel or Japan? Will authoritarian states like China be better able to manage these tendencies, or not? To what extent will these trends intensify? What new trends will emerge in coming decades with advent of yet more new technologies? Amidst this uncertainty, there will certainly also be political opportunities.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Ultra-Graal est un petit livre merveilleux ; il s’adresse à l’âme de ceux qui croient encore possible d’aller en quête du « Saint Vase » à la suite des rois cachés, des chevaliers errants et des fidèles d’amour. Dans une sorte d’exhortation adressée à ses frères d’esprit, Bertrand Lacarelle invite à reprendre ce voyage qui mène au cœur de la France, dans la forêt sombre et épaisse où, parmi les ronces et les fougères, s’élève une « cathédrale oubliée ». On y trouvera sur l’autel de marbre blanc, éclairé par le grand soleil, la coupe du Graal – celle qui a recueilli le sang du Christ.

Ultra-Graal est un petit livre merveilleux ; il s’adresse à l’âme de ceux qui croient encore possible d’aller en quête du « Saint Vase » à la suite des rois cachés, des chevaliers errants et des fidèles d’amour. Dans une sorte d’exhortation adressée à ses frères d’esprit, Bertrand Lacarelle invite à reprendre ce voyage qui mène au cœur de la France, dans la forêt sombre et épaisse où, parmi les ronces et les fougères, s’élève une « cathédrale oubliée ». On y trouvera sur l’autel de marbre blanc, éclairé par le grand soleil, la coupe du Graal – celle qui a recueilli le sang du Christ.

Dans toute l’Europe francophone apparaît brusquement « rénové », c’est-à-dire en rupture avec l’autorité magistrale, les techniques de dressage (Roland Barthes qualifie l’orthographe de « fasciste »), l’enracinement dans l’histoire nationale et l’apprentissage des langues anciennes (latin, grec). On retrouve dans la mentalité des Partout cette hantise de la « réalisation de soi » au mépris de toute règle contraignante, de toute référence au passé et de tout sentiment d’appartenance à une communauté organique.

Dans toute l’Europe francophone apparaît brusquement « rénové », c’est-à-dire en rupture avec l’autorité magistrale, les techniques de dressage (Roland Barthes qualifie l’orthographe de « fasciste »), l’enracinement dans l’histoire nationale et l’apprentissage des langues anciennes (latin, grec). On retrouve dans la mentalité des Partout cette hantise de la « réalisation de soi » au mépris de toute règle contraignante, de toute référence au passé et de tout sentiment d’appartenance à une communauté organique. À l’époque où j’étudiais à l’Université de Bruxelles, il y avait deux cités universitaires : l’une pour les garçons au cœur du campus, l’autre pour les jeunes filles légèrement en dehors. Ainsi pouvaient déjà se côtoyer, vers 1970, des jeunes provenant de toutes les provinces du Royaume. Le programme Erasmus, d’abord à l’échelon européen, puis au plan mondial, accentue ensuite cet élargissement des horizons et l’impression que « le monde est un village », pour reprendre le titre d’une émission créée par la radio belge francophone en 1998. « La massification de l’enseignement supérieur », l’émergence d’un « secteur universitaire hypertrophié » : voilà des phénomènes qui remontent aux années 1960, vont de pair avec une disqualification du travail manuel et ipso facto avec l’immigration fournissant au patronat une armée de réserve, une classe ouvrière de rechange.

À l’époque où j’étudiais à l’Université de Bruxelles, il y avait deux cités universitaires : l’une pour les garçons au cœur du campus, l’autre pour les jeunes filles légèrement en dehors. Ainsi pouvaient déjà se côtoyer, vers 1970, des jeunes provenant de toutes les provinces du Royaume. Le programme Erasmus, d’abord à l’échelon européen, puis au plan mondial, accentue ensuite cet élargissement des horizons et l’impression que « le monde est un village », pour reprendre le titre d’une émission créée par la radio belge francophone en 1998. « La massification de l’enseignement supérieur », l’émergence d’un « secteur universitaire hypertrophié » : voilà des phénomènes qui remontent aux années 1960, vont de pair avec une disqualification du travail manuel et ipso facto avec l’immigration fournissant au patronat une armée de réserve, une classe ouvrière de rechange.

J

J 1 :

1 :

Après bien d’autres, d’ailleurs cités par l’auteur (y compris Charles Murray

Après bien d’autres, d’ailleurs cités par l’auteur (y compris Charles Murray C’est la sélection croissante, au cours de 70 dernières années, sur les performances cognitives dans l’éducation supérieure qui a abouti à la création d’une classe cognitive, renforcée aujourd’hui par l’endogamie cognitive (combinant héritage génétique et ressources pour l’éducation), rendue plus facile avec l’accès croissant des femmes à l’éducation supérieure. Dans Coming Apart , Charles Murray avait montré que Princeton et Yale accueillaient plus d’étudiants provenant du dernier centile que des 6 premiers déciles de revenu.

C’est la sélection croissante, au cours de 70 dernières années, sur les performances cognitives dans l’éducation supérieure qui a abouti à la création d’une classe cognitive, renforcée aujourd’hui par l’endogamie cognitive (combinant héritage génétique et ressources pour l’éducation), rendue plus facile avec l’accès croissant des femmes à l’éducation supérieure. Dans Coming Apart , Charles Murray avait montré que Princeton et Yale accueillaient plus d’étudiants provenant du dernier centile que des 6 premiers déciles de revenu. Et en politique

Et en politique L’économie du soin a un double problème : il est de moins en moins attractif et ceux qui y travaillent s’en vont, souvent désenchantés. Les hommes, particulièrement ceux qui ont un faible statut, ont perdu, sans pouvoir rien mettre à la place, leur rôle principal qui était celui de gagner l’argent de la famille. Un nombre disproportionné de métiers qui ne peuvent être automatisés sont traditionnellement occupés par des femmes, métiers qui n’attirent pas les hommes. Daniel Susskind, dans A World Without Work, publié en 2020, rapporte les résultats d’une enquête au Royaume-Uni selon laquelle « la plupart des hommes qui ont perdu leur emploi industriel préfèrent ne pas travailler que de prendre un “pink collar work” » (traduction personnelle).

L’économie du soin a un double problème : il est de moins en moins attractif et ceux qui y travaillent s’en vont, souvent désenchantés. Les hommes, particulièrement ceux qui ont un faible statut, ont perdu, sans pouvoir rien mettre à la place, leur rôle principal qui était celui de gagner l’argent de la famille. Un nombre disproportionné de métiers qui ne peuvent être automatisés sont traditionnellement occupés par des femmes, métiers qui n’attirent pas les hommes. Daniel Susskind, dans A World Without Work, publié en 2020, rapporte les résultats d’une enquête au Royaume-Uni selon laquelle « la plupart des hommes qui ont perdu leur emploi industriel préfèrent ne pas travailler que de prendre un “pink collar work” » (traduction personnelle). S’il faut préserver les procédures de sélection méritocratiques, il faut aussi veiller à répartir respect et statut plus équitablement en élargissant les sources de réussite et en élevant le statut de ceux qui ne vont pas à l’université. Les dernières recherches sur les capacités cognitives pourraient nous y aider. Une étude menée à l’université Carnegie Mellon aux États-Unis définit trois types de styles cognitifs : la verbalisation (journalistes, avocats…) ; la visualisation spatiale (ceux qui pensent analytiquement : ingénieurs, mathématiciens…) ; la visualisation des objets (artistes…) qui ont tendance à penser un contexte plus large. Mais la diversité doit aussi s’appliquer aux idéologies et valeurs politiques.

S’il faut préserver les procédures de sélection méritocratiques, il faut aussi veiller à répartir respect et statut plus équitablement en élargissant les sources de réussite et en élevant le statut de ceux qui ne vont pas à l’université. Les dernières recherches sur les capacités cognitives pourraient nous y aider. Une étude menée à l’université Carnegie Mellon aux États-Unis définit trois types de styles cognitifs : la verbalisation (journalistes, avocats…) ; la visualisation spatiale (ceux qui pensent analytiquement : ingénieurs, mathématiciens…) ; la visualisation des objets (artistes…) qui ont tendance à penser un contexte plus large. Mais la diversité doit aussi s’appliquer aux idéologies et valeurs politiques.

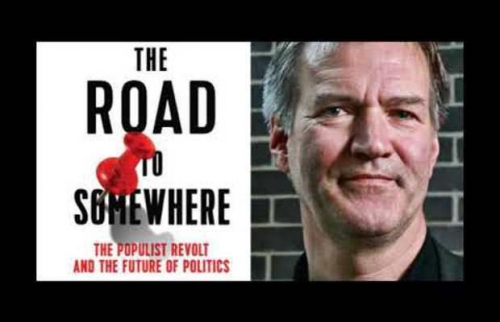

David Goodhart

David Goodhart Vocation

Vocation The three top professions are medicine, the law, and the clergy. If you feel called to do any of these jobs, don’t pass them up. As far as enlisting, I must state upfront that there are many ways to serve your country outside of the infantry. Some further advice on this can be found

The three top professions are medicine, the law, and the clergy. If you feel called to do any of these jobs, don’t pass them up. As far as enlisting, I must state upfront that there are many ways to serve your country outside of the infantry. Some further advice on this can be found

¿Cómo surgió la idea de escribir el librito “Vascos y Navarros”?

¿Cómo surgió la idea de escribir el librito “Vascos y Navarros”?

Lo que hace el Gobierno Vasco para la defensa de la lengua vasca me parece bastante acertado, a pesar de todas las acciones caricaturescas y desprovistas de sentido que han sido tomadas en contra del idioma castellano o -mejor dicho- del español, una de las dos o tres lengua más habladas del mundo. Ya sabemos que el idioma no es suficiente, pero además de esto no se debe esconder que los resultados de las políticas a favor del euskera son más bien escasos. La realidad es que no hay nación o patria posible sin un legado histórico combinado a un consentimiento y una voluntad de existencia por parte del pueblo. Nicolas Berdiaev y otros autores europeos famosos como Ortega y Gasset hablaban de unidad o comunidad de destino histórico. Pues bien, sin la combinación armoniosa del fundamento histórico-cultural y del factor voluntarista o consensual, sin esos dos ejes, no puede haber nación. Y por eso ya no hay hoy una verdadera nación española como no hay tampoco hoy verdaderas nacionalidades o naciones pequeñas dentro de España.

Lo que hace el Gobierno Vasco para la defensa de la lengua vasca me parece bastante acertado, a pesar de todas las acciones caricaturescas y desprovistas de sentido que han sido tomadas en contra del idioma castellano o -mejor dicho- del español, una de las dos o tres lengua más habladas del mundo. Ya sabemos que el idioma no es suficiente, pero además de esto no se debe esconder que los resultados de las políticas a favor del euskera son más bien escasos. La realidad es que no hay nación o patria posible sin un legado histórico combinado a un consentimiento y una voluntad de existencia por parte del pueblo. Nicolas Berdiaev y otros autores europeos famosos como Ortega y Gasset hablaban de unidad o comunidad de destino histórico. Pues bien, sin la combinación armoniosa del fundamento histórico-cultural y del factor voluntarista o consensual, sin esos dos ejes, no puede haber nación. Y por eso ya no hay hoy una verdadera nación española como no hay tampoco hoy verdaderas nacionalidades o naciones pequeñas dentro de España.

Nos auteurs pensent que l’illibéralisme qui se caractérise par le phénomène des populismes qui émergent sous différentes modalités est « une marée montante menaçante » prenant la forme de l’anarchie illibérale et antidémocratique. Ils ne conçoivent pas que les populismes puissent au contraire être l’expression d’une attente de démocratie, cette démocratie depuis trop longtemps confisquée par les élites libérales mondiales et leur soft power pernicieux. Le plafond de verre de leur analyse du populisme vu sous l’angle réducteur du danger constitue la limite principale de l’ouvrage.

Nos auteurs pensent que l’illibéralisme qui se caractérise par le phénomène des populismes qui émergent sous différentes modalités est « une marée montante menaçante » prenant la forme de l’anarchie illibérale et antidémocratique. Ils ne conçoivent pas que les populismes puissent au contraire être l’expression d’une attente de démocratie, cette démocratie depuis trop longtemps confisquée par les élites libérales mondiales et leur soft power pernicieux. Le plafond de verre de leur analyse du populisme vu sous l’angle réducteur du danger constitue la limite principale de l’ouvrage.

Review:

Review: Salazar had written on various relatively obscure subjects before achieving fame with the 2015 publication of his reports on ISIS, Paroles Armées (Armed Words). His specialist field of study is rhetoric: how the power and associative imagery of words can be used as a tool in appropriating or resisting power. Rhetoric as a legitimate democratic tool recalls the sophists who marketed their skills in Ancient Athens to ambitious politicians and were lambasted for so doing by Socrates. Salazar seems interested in words less as tools to discover the truth than as tools in a struggle to gain ascendancy.

Salazar had written on various relatively obscure subjects before achieving fame with the 2015 publication of his reports on ISIS, Paroles Armées (Armed Words). His specialist field of study is rhetoric: how the power and associative imagery of words can be used as a tool in appropriating or resisting power. Rhetoric as a legitimate democratic tool recalls the sophists who marketed their skills in Ancient Athens to ambitious politicians and were lambasted for so doing by Socrates. Salazar seems interested in words less as tools to discover the truth than as tools in a struggle to gain ascendancy. From this alone the reader can see we are far from the earnestness of the usual “investigative reporter.” There is a lightness about this inquiry, a certain half-suppressed amusement which gives a very great advantage and a very great drawback to the study.

From this alone the reader can see we are far from the earnestness of the usual “investigative reporter.” There is a lightness about this inquiry, a certain half-suppressed amusement which gives a very great advantage and a very great drawback to the study. Here is an example of Salazar’s showmanship approach. This is how the chapter entitled “A Cosmopolitan Croatian” begins:

Here is an example of Salazar’s showmanship approach. This is how the chapter entitled “A Cosmopolitan Croatian” begins: A chapter with more substance than many is “A Global White Nationalist” (English in the original), Salazar’s talk with the editor of Counter-Currents, Greg Johnson. Johnson’s clear aims are outlined. A question and answer session ensues on page 183 which reminded me of a Roman Catholic catechism recital.

A chapter with more substance than many is “A Global White Nationalist” (English in the original), Salazar’s talk with the editor of Counter-Currents, Greg Johnson. Johnson’s clear aims are outlined. A question and answer session ensues on page 183 which reminded me of a Roman Catholic catechism recital.

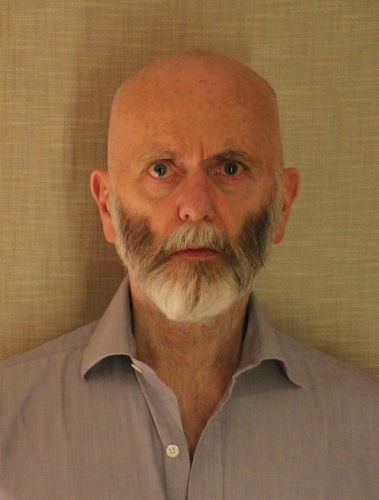

Camus’ definition of race is original: cultural apprenticeship plus natural reproduction equals race. This perhaps Evolian notion of race runs counter to the biological rationalist understanding of most North Americans. Salazar visits Camus, a Baron de Charlus character, in his Medieval castle tower in the Gers in rural France. He passes a Peugeot dealership in the middle of the countryside on his way to Camus and enigmatically states that “it should not be.” (p. 244). Salazar is not making a moral judgment here. He means the machine is not appropriate to this setting. Some might argue to the contrary: bringing small industry home to the nation and away from the big cities is too little, too late; it is what would have prevented the land drain that transformed France in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Then the question: How should and could regional identity work? Would home industry prove more a blessing or a bane? What of Trump’s insistence on prioritizing home industries in contrast with the EU’s extreme globalism? Salazar has nothing to say on this and presumably does not encourage Camus to say anything about it. Again, we have a debate that wasn’t. Salazar makes it clear that the interview with Camus was a disappointment, albeit the two part on friendly terms. Salazar dismissively asks himself rhetorically how many thinkers of the alt-right have read the book so praised by Camus as a key to understanding the true meaning of racial and cultural replacement, La Grande Peur des bien-pensants (The Great Fear of right-thinking people) by Georges Bernanos? (p. 252) Nevertheless he concedes, seemingly contradicting himself, and citing Barthes, that Camus is right about the evocative power of words:

Camus’ definition of race is original: cultural apprenticeship plus natural reproduction equals race. This perhaps Evolian notion of race runs counter to the biological rationalist understanding of most North Americans. Salazar visits Camus, a Baron de Charlus character, in his Medieval castle tower in the Gers in rural France. He passes a Peugeot dealership in the middle of the countryside on his way to Camus and enigmatically states that “it should not be.” (p. 244). Salazar is not making a moral judgment here. He means the machine is not appropriate to this setting. Some might argue to the contrary: bringing small industry home to the nation and away from the big cities is too little, too late; it is what would have prevented the land drain that transformed France in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Then the question: How should and could regional identity work? Would home industry prove more a blessing or a bane? What of Trump’s insistence on prioritizing home industries in contrast with the EU’s extreme globalism? Salazar has nothing to say on this and presumably does not encourage Camus to say anything about it. Again, we have a debate that wasn’t. Salazar makes it clear that the interview with Camus was a disappointment, albeit the two part on friendly terms. Salazar dismissively asks himself rhetorically how many thinkers of the alt-right have read the book so praised by Camus as a key to understanding the true meaning of racial and cultural replacement, La Grande Peur des bien-pensants (The Great Fear of right-thinking people) by Georges Bernanos? (p. 252) Nevertheless he concedes, seemingly contradicting himself, and citing Barthes, that Camus is right about the evocative power of words:

Machiavel conseille un peu de chaos, un peu de dissonance et d’incohérences pour contrôler la masse :

Machiavel conseille un peu de chaos, un peu de dissonance et d’incohérences pour contrôler la masse : Les réformes ? Mais l’Etat adore réformer la France, l’Europe, le monde, les retraites :

Les réformes ? Mais l’Etat adore réformer la France, l’Europe, le monde, les retraites : Enfin le peuple maso aime et comprend les coups, le 11 septembre, et tous les Bataclan :

Enfin le peuple maso aime et comprend les coups, le 11 septembre, et tous les Bataclan :

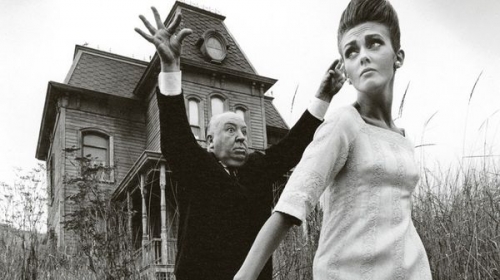

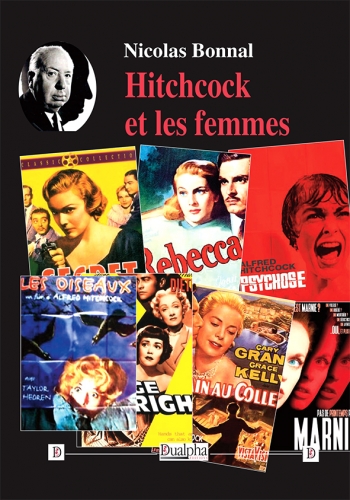

Tu distingues de nombreux type de femmes…

Tu distingues de nombreux type de femmes… Tu évoques beaucoup les décors dans ton essai…

Tu évoques beaucoup les décors dans ton essai… Et il y a Shirley McLaine dans Harry…

Et il y a Shirley McLaine dans Harry…

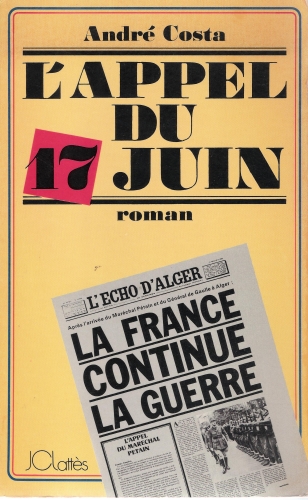

Navigateur, pilote automobile et historien à ses heures perdues, André Costa (1926 – 2002) a dirigé L’Auto-Journal, le fleuron du groupe de presse de Robert Hersant entre 1950 et 1991. Sa passion pour les sports mécaniques en fait un journaliste féru d’essais des nouveaux modèles automobile. Souvent présent aux courses motorisées en circuit fermé ou en rallye, il écrit des ouvrages spécialisés (Les roues libres). Il se distingue aussi par L’appel du 17 juin, un brillant récit uchronique.

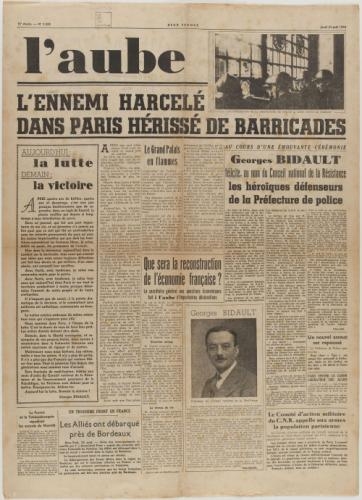

Navigateur, pilote automobile et historien à ses heures perdues, André Costa (1926 – 2002) a dirigé L’Auto-Journal, le fleuron du groupe de presse de Robert Hersant entre 1950 et 1991. Sa passion pour les sports mécaniques en fait un journaliste féru d’essais des nouveaux modèles automobile. Souvent présent aux courses motorisées en circuit fermé ou en rallye, il écrit des ouvrages spécialisés (Les roues libres). Il se distingue aussi par L’appel du 17 juin, un brillant récit uchronique. Berlin nomme comme Gauleiter de la France occupée Otto Abetz. Afin de contrer la légitimité du gouvernement français d’Alger, il incite Pierre Laval à devenir le chef d’un gouvernement embryonnaire avec pour seuls ministres Marcel Déat à l’Intérieur et Jacques Doriot à la Défense nationale. L’auteur s’inscrit ici dans la convenance historique. On peut très bien imaginer que les militants du « Grand Jacques » suivent l’appel du Maréchal et s’engagent dans une féroce guérilla. Celle-ci n’est pas le fait comme en 1870 de francs-tireurs, mais de soldats français restés en métropole et regroupés en « Unités spéciales ». La n° 1 est directement dirigée par un prisonnier de guerre évadé et ancien corps-franc en 1939 – 1940 : Joseph Darnand. Celui-ci monte de multiples actions meurtrières contre les occupants allemands. André Costa tient probablement à rappeler ce qu’écrivait Georges Bernanos : « S’il y avait eu plus de Darnand en 1940, il n’y aurait pas eu de miliciens en 1944. » Exempt donc de toute interprétation « paxtonite », L’appel du 17 juin décrit les premières persécutions de la population juive dans tout le pays dès l’été 1940.

Berlin nomme comme Gauleiter de la France occupée Otto Abetz. Afin de contrer la légitimité du gouvernement français d’Alger, il incite Pierre Laval à devenir le chef d’un gouvernement embryonnaire avec pour seuls ministres Marcel Déat à l’Intérieur et Jacques Doriot à la Défense nationale. L’auteur s’inscrit ici dans la convenance historique. On peut très bien imaginer que les militants du « Grand Jacques » suivent l’appel du Maréchal et s’engagent dans une féroce guérilla. Celle-ci n’est pas le fait comme en 1870 de francs-tireurs, mais de soldats français restés en métropole et regroupés en « Unités spéciales ». La n° 1 est directement dirigée par un prisonnier de guerre évadé et ancien corps-franc en 1939 – 1940 : Joseph Darnand. Celui-ci monte de multiples actions meurtrières contre les occupants allemands. André Costa tient probablement à rappeler ce qu’écrivait Georges Bernanos : « S’il y avait eu plus de Darnand en 1940, il n’y aurait pas eu de miliciens en 1944. » Exempt donc de toute interprétation « paxtonite », L’appel du 17 juin décrit les premières persécutions de la population juive dans tout le pays dès l’été 1940. Il est probable qu’André Costa ait lu la trilogie des Waffen SS français de « Maît’Jean ». Rédacteur en chef de L’Auto-Journal, il devait de temps en temps rencontrer son grand patron, Robert Hersant, ancien du Jeune Front du Parti français national-collectiviste de Pierre Clémenti. Ce passionné de l’automobile côtoyait par ailleurs Jean-Marie Balestre, président de la Fédération internationale du sport automobile (FISA) entre 1978 et 1991, qui, dans sa jeunesse, avait été un volontaire français de la Waffen SS tout en restant proche des milieux de la Résistance intérieure. Affecté au journal SS français Devenir, il rédigeait sous l’autorité de… Saint-Loup. Il est envisageable qu’après avoir épuisé leur conversation favorite consacrée aux voitures, André Costa et Jean-Marie Balestre en viennent à parler de leur engagement militaire respectif passé.

Il est probable qu’André Costa ait lu la trilogie des Waffen SS français de « Maît’Jean ». Rédacteur en chef de L’Auto-Journal, il devait de temps en temps rencontrer son grand patron, Robert Hersant, ancien du Jeune Front du Parti français national-collectiviste de Pierre Clémenti. Ce passionné de l’automobile côtoyait par ailleurs Jean-Marie Balestre, président de la Fédération internationale du sport automobile (FISA) entre 1978 et 1991, qui, dans sa jeunesse, avait été un volontaire français de la Waffen SS tout en restant proche des milieux de la Résistance intérieure. Affecté au journal SS français Devenir, il rédigeait sous l’autorité de… Saint-Loup. Il est envisageable qu’après avoir épuisé leur conversation favorite consacrée aux voitures, André Costa et Jean-Marie Balestre en viennent à parler de leur engagement militaire respectif passé. Élu chef de l’État, le Maréchal nomme le général de Gaulle Premier ministre. Ce prisme institutionnel « gaullien » dénote dans l’économie générale du récit. L’auteur ne se rapporte jamais à la loi Tréveneuc du 23 février 1872 qui, en cas d’empêchement du Parlement, permet à tous les conseils généraux disponibles de choisir en leur sein deux délégués qui forment alors une assemblée nationale provisoire. Cherche-t-il aussi à réconcilier à travers ce récit fictif gaullistes et pétainistes ? Lors d’une nouvelle discussion entre les deux plus grands personnages français du XXe siècle, il fait dire à Charles de Gaulle les conséquences qu’aurait eues un éventuel armistice :

Élu chef de l’État, le Maréchal nomme le général de Gaulle Premier ministre. Ce prisme institutionnel « gaullien » dénote dans l’économie générale du récit. L’auteur ne se rapporte jamais à la loi Tréveneuc du 23 février 1872 qui, en cas d’empêchement du Parlement, permet à tous les conseils généraux disponibles de choisir en leur sein deux délégués qui forment alors une assemblée nationale provisoire. Cherche-t-il aussi à réconcilier à travers ce récit fictif gaullistes et pétainistes ? Lors d’une nouvelle discussion entre les deux plus grands personnages français du XXe siècle, il fait dire à Charles de Gaulle les conséquences qu’aurait eues un éventuel armistice : André Costa se plaît ici à reprendre la célèbre formule du Colonel Rémy (alias Gilbert Renault). Ce résistant royaliste de la première heure, plus tard Compagnon de la Libération, fondateur du réseau résistant « Confrérie Notre-Dame », principal orateur du mouvement gaulliste d’opposition RPF (Rassemblement du peuple français), soutient en 1950 dans l’hebdomadaire Carrefour la « théorie des deux cordes », soit un accord tacite entre l’« épée » de Gaulle et le « bouclier » Pétain. Une version aujourd’hui hérétique dans l’université putréfiée hexagonale, mais qui reste largement valable, n’en déplaise aux sycophantes en place.

André Costa se plaît ici à reprendre la célèbre formule du Colonel Rémy (alias Gilbert Renault). Ce résistant royaliste de la première heure, plus tard Compagnon de la Libération, fondateur du réseau résistant « Confrérie Notre-Dame », principal orateur du mouvement gaulliste d’opposition RPF (Rassemblement du peuple français), soutient en 1950 dans l’hebdomadaire Carrefour la « théorie des deux cordes », soit un accord tacite entre l’« épée » de Gaulle et le « bouclier » Pétain. Une version aujourd’hui hérétique dans l’université putréfiée hexagonale, mais qui reste largement valable, n’en déplaise aux sycophantes en place. Sans le savoir, André Costa anticipe ici la thèse, contestée bien évidemment par les historiens de cour, de Victor Suvorov dans Le brise-glace (3). « Hitler croyait l’invasion inévitable, mais il ne pensait pas qu’elle serait imminente. Les troupes allemandes étant employées à des opérations secondaires, l’opération “ Barbarossa ” fut même reportée à plusieurs reprises. Elle commença enfin le 22 juin 1941. Hitler ne se rendit manifestement pas compte à quel point il avait eu de la chance. S’il avait repoussé son plan une nouvelle fois, par exemple au 22 juillet, il aurait très certainement fini la guerre bien avant 1945. Nombre d’indices tendent à prouver que la date fixée par Staline pour l’opération “ Orage ” était le 6 juillet 1941 (4). » Dans le contexte géopolitique propre à L’appel du 17 juin, à la vue des défaites successives de l’Axe, Staline peut fort bien avancer au mois de février son plan de conquête de l’Europe. L’auteur ne dit rien sur l’éventuel déclenchement parallèle, coordonné et simultané par les appareils clandestins communistes de grandes grèves générales et d’actes révolutionnaires subversifs dans l’Europe entière ainsi qu’en Afrique du Nord. Joachim F. Weber rappelle pour sa part dans la revue jeune-conservatrice

Sans le savoir, André Costa anticipe ici la thèse, contestée bien évidemment par les historiens de cour, de Victor Suvorov dans Le brise-glace (3). « Hitler croyait l’invasion inévitable, mais il ne pensait pas qu’elle serait imminente. Les troupes allemandes étant employées à des opérations secondaires, l’opération “ Barbarossa ” fut même reportée à plusieurs reprises. Elle commença enfin le 22 juin 1941. Hitler ne se rendit manifestement pas compte à quel point il avait eu de la chance. S’il avait repoussé son plan une nouvelle fois, par exemple au 22 juillet, il aurait très certainement fini la guerre bien avant 1945. Nombre d’indices tendent à prouver que la date fixée par Staline pour l’opération “ Orage ” était le 6 juillet 1941 (4). » Dans le contexte géopolitique propre à L’appel du 17 juin, à la vue des défaites successives de l’Axe, Staline peut fort bien avancer au mois de février son plan de conquête de l’Europe. L’auteur ne dit rien sur l’éventuel déclenchement parallèle, coordonné et simultané par les appareils clandestins communistes de grandes grèves générales et d’actes révolutionnaires subversifs dans l’Europe entière ainsi qu’en Afrique du Nord. Joachim F. Weber rappelle pour sa part dans la revue jeune-conservatrice

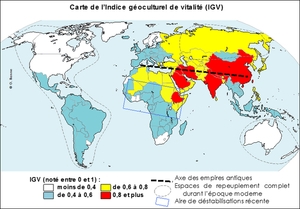

En réalité, ce primat de l’économie se révèle une illusion d’optique. Il est d’ailleurs contesté par les mouvements altermondialistes et écologiques, les chiffres de l’abstention électorale et le retour de la rhétorique patriotique. Partout, des appels à une autre « gouvernance » se font entendre. Un nouvel avenir est annoncé, celui du renversement des échanges de marchandises au profit des solidarités sociales. Mais, paradoxalement, la contestation altermondialiste ne remet pas fondamentalement en cause le primat de l’économie : la décroissance, l’inversion des profits et la taxation des bénéfices financiers ne servent qu’à promouvoir une nouvelle révolution matérielle mondiale. Bref, même chez ceux qui souhaitent abolir le capitalisme marchand, tout ne reste qu’économique. Or les données chiffrées ne nous offrent qu’une idée imparfaite des risques à venir. De plus, ces indicateurs complexes se manipulent aisément. La réduction du monde au simple jeu des forces économiques fait finalement obstacle à l’intelligence car elle passe deux dimensions essentielles sous silence : l’affirmation des cultures et la volonté de puissance.

En réalité, ce primat de l’économie se révèle une illusion d’optique. Il est d’ailleurs contesté par les mouvements altermondialistes et écologiques, les chiffres de l’abstention électorale et le retour de la rhétorique patriotique. Partout, des appels à une autre « gouvernance » se font entendre. Un nouvel avenir est annoncé, celui du renversement des échanges de marchandises au profit des solidarités sociales. Mais, paradoxalement, la contestation altermondialiste ne remet pas fondamentalement en cause le primat de l’économie : la décroissance, l’inversion des profits et la taxation des bénéfices financiers ne servent qu’à promouvoir une nouvelle révolution matérielle mondiale. Bref, même chez ceux qui souhaitent abolir le capitalisme marchand, tout ne reste qu’économique. Or les données chiffrées ne nous offrent qu’une idée imparfaite des risques à venir. De plus, ces indicateurs complexes se manipulent aisément. La réduction du monde au simple jeu des forces économiques fait finalement obstacle à l’intelligence car elle passe deux dimensions essentielles sous silence : l’affirmation des cultures et la volonté de puissance.

Or ce qui est vrai pour les empires ne l’est pas moins pour les entreprises, dont la durée de vie et la santé financière sont menacées par leur croyance au mythe techniciste. Ainsi en est-il au dernier stade pour les familles qui se perpétuent dans la longue durée lorsqu’elles adhèrent à des valeurs spirituelles forçant leurs membres à se dépasser ou à l’inverse s’atomisent en une multitude d’individus rivaux, attirés, tels des lucioles, vers le profit qui les calcinera. Les nations durables s’enracinent par conséquent dans des cultures qui peuvent être d’une variété inouïe, mais qui pour perpétuer la vie, doivent pouvoir se renouveler sans pour autant se renier.

Or ce qui est vrai pour les empires ne l’est pas moins pour les entreprises, dont la durée de vie et la santé financière sont menacées par leur croyance au mythe techniciste. Ainsi en est-il au dernier stade pour les familles qui se perpétuent dans la longue durée lorsqu’elles adhèrent à des valeurs spirituelles forçant leurs membres à se dépasser ou à l’inverse s’atomisent en une multitude d’individus rivaux, attirés, tels des lucioles, vers le profit qui les calcinera. Les nations durables s’enracinent par conséquent dans des cultures qui peuvent être d’une variété inouïe, mais qui pour perpétuer la vie, doivent pouvoir se renouveler sans pour autant se renier.

Fort peu de lecteurs auront la chance de tenir entre leurs mains la belle quadruple étude de Jacques Dewitte, Le pouvoir de la langue et la liberté de l'esprit, sous-titré Essai sur la résistance au langage totalitaire, que l'éditeur, Michalon, n'a pas jugé utile de rééditer depuis 2007. Il n'est donc pas étonnant que cet ouvrage atteigne désormais des sommes coquettes sur les différents sites de librairies en ligne. Au moins, ce lecteur curieux n'aura pas le regard épouvanté par la première de couverture, très laide illustration imbriquant un labyrinthe et un goéland toutes ailes déployées qui, je le suppose, dans l'esprit du crétin responsable d'un tel saccage inesthétique, doit parfaitement convenir au mouvement de balancier que l'auteur imprime à sa problématique : d'un côté le langage à visée totalitaire, englobant tout, prétendant du moins tout englober, de l'autre la réalité qu'il tente à n'importe quel prix de gauchir, de grimer, jusqu'à ce qu'elle corresponde à ses mots et slogans pourris. Il ne s'agit cependant point, en analysant le langage vérolé, de s'exonérer du langage lui-même, car Jacques Dewitte a raison de nous rappeler que, sans la médiation complexe qu'imposent les mots, la réalité n'est rien. Dès lors, il faut parier qu'il n'y a «dépassement de l'emprise totalitaire que par un mouvement double où l'on retrouve une forme de circularité», à savoir «un mouvement vers les choses», mais aussi la «mise en œuvre des mots», et, à cette fin, la «remise en route de la parole lorsqu'elle s'est enlisée, mais encore, compte tenu de sa fréquente détérioration», la «remise en état de la langue» (1). Nous verrons qu'il n'est pas si facile que cela, en soignant le langage contaminé par le bacille du slogan, de la langue de bois, de la fausse langue à visées hégémoniques, de retrouver le monde : le langage totalitaire, le langage maléfique, même, que Jacques Dewitte évoque hélas trop peu, ont pour particularité, en contaminant celles et ceux qui l'emploient, de saper les fondements de notre confiance dans le monde.

Fort peu de lecteurs auront la chance de tenir entre leurs mains la belle quadruple étude de Jacques Dewitte, Le pouvoir de la langue et la liberté de l'esprit, sous-titré Essai sur la résistance au langage totalitaire, que l'éditeur, Michalon, n'a pas jugé utile de rééditer depuis 2007. Il n'est donc pas étonnant que cet ouvrage atteigne désormais des sommes coquettes sur les différents sites de librairies en ligne. Au moins, ce lecteur curieux n'aura pas le regard épouvanté par la première de couverture, très laide illustration imbriquant un labyrinthe et un goéland toutes ailes déployées qui, je le suppose, dans l'esprit du crétin responsable d'un tel saccage inesthétique, doit parfaitement convenir au mouvement de balancier que l'auteur imprime à sa problématique : d'un côté le langage à visée totalitaire, englobant tout, prétendant du moins tout englober, de l'autre la réalité qu'il tente à n'importe quel prix de gauchir, de grimer, jusqu'à ce qu'elle corresponde à ses mots et slogans pourris. Il ne s'agit cependant point, en analysant le langage vérolé, de s'exonérer du langage lui-même, car Jacques Dewitte a raison de nous rappeler que, sans la médiation complexe qu'imposent les mots, la réalité n'est rien. Dès lors, il faut parier qu'il n'y a «dépassement de l'emprise totalitaire que par un mouvement double où l'on retrouve une forme de circularité», à savoir «un mouvement vers les choses», mais aussi la «mise en œuvre des mots», et, à cette fin, la «remise en route de la parole lorsqu'elle s'est enlisée, mais encore, compte tenu de sa fréquente détérioration», la «remise en état de la langue» (1). Nous verrons qu'il n'est pas si facile que cela, en soignant le langage contaminé par le bacille du slogan, de la langue de bois, de la fausse langue à visées hégémoniques, de retrouver le monde : le langage totalitaire, le langage maléfique, même, que Jacques Dewitte évoque hélas trop peu, ont pour particularité, en contaminant celles et ceux qui l'emploient, de saper les fondements de notre confiance dans le monde. C'est dire qu'il ne faut pas seulement parler de «bouclage absolu» (2) à propos de la fable langagière génialement dépeinte par George Orwell dans 1984, mais, aussi et voilà qui ne laisse pas d'être inquiétant, pour notre si irénique et consensuelle société dont nous ne manquerions pas de choquer les commis si nous leur prouvions qu'ils ne tolèrent rien de ce qui serait susceptible de heurter leurs petites convictions normativement castrées. Et force est alors de constater que le langage totalitaire n'est pas celui, d'acier ou d'airain, mis en circulation par les seuls régimes autoritaires, puisque nous pourrions à bon droit prétendre que la novlangue (3) démocratique, comme n'importe lequel de ces langages cherchant à triompher de ses concurrents,

C'est dire qu'il ne faut pas seulement parler de «bouclage absolu» (2) à propos de la fable langagière génialement dépeinte par George Orwell dans 1984, mais, aussi et voilà qui ne laisse pas d'être inquiétant, pour notre si irénique et consensuelle société dont nous ne manquerions pas de choquer les commis si nous leur prouvions qu'ils ne tolèrent rien de ce qui serait susceptible de heurter leurs petites convictions normativement castrées. Et force est alors de constater que le langage totalitaire n'est pas celui, d'acier ou d'airain, mis en circulation par les seuls régimes autoritaires, puisque nous pourrions à bon droit prétendre que la novlangue (3) démocratique, comme n'importe lequel de ces langages cherchant à triompher de ses concurrents,  Jacques Dewitte, hélas, ne poursuit pas plus avant son exploration de ces contrées interdites, ne se dirige pas, hardiment, vers le Kurtz de Conrad et son décalque steinerien comme j'ai pu tenter de le faire dans

Jacques Dewitte, hélas, ne poursuit pas plus avant son exploration de ces contrées interdites, ne se dirige pas, hardiment, vers le Kurtz de Conrad et son décalque steinerien comme j'ai pu tenter de le faire dans  Cette confiance dans le langage sortira même renforcée de «l'expérience totalitaire» et de «la crise contemporaine» (p. 235) sur laquelle, hélas, Jacques Dewitte ne s'attarde guère (6), préférant insister, je l'ai dit, sur des remèdes qui sont à la portée de tout un chacun mais me paraissent pourtant absolument ridicules face au déferlement des langages viciés, dont la novlangue managériale, que Baptiste Rappin analyse comme le bras armé de la Machine, est le masque le plus grimaçant et redoutable. S'il est certes absolument évident à mes yeux que «l'existence d'un ordre stable du monde et de la langue (7) est une condition de la liberté (et pas seulement de la vérité), et qu'une liberté devenue un arbitraire institutionnalisé se révèle le pire ennemi de la vraie liberté individuelle» (p. 252), je suis bien davantage sceptique sur la belle confiance dont témoigne Jacques Dewitte évoquant «la fin du cauchemar engendré par les utopies», censé inaugurer «le retour à une vie humaine finie et imparfaite», ainsi qu'un «retour au champ où la parole rencontre la réalité, où une relation mutuelle peut s'établir entre elles», un «retour à une situation où la pensée qui se cherche doit aussi chercher et choisir ses mots, c'est-à-dire effectuer un va-et-vient entre la chose-à-dire et les ressources de la langue héritée, sans être d'emblée captivée par tel vocable devenu quasi compulsif».

Cette confiance dans le langage sortira même renforcée de «l'expérience totalitaire» et de «la crise contemporaine» (p. 235) sur laquelle, hélas, Jacques Dewitte ne s'attarde guère (6), préférant insister, je l'ai dit, sur des remèdes qui sont à la portée de tout un chacun mais me paraissent pourtant absolument ridicules face au déferlement des langages viciés, dont la novlangue managériale, que Baptiste Rappin analyse comme le bras armé de la Machine, est le masque le plus grimaçant et redoutable. S'il est certes absolument évident à mes yeux que «l'existence d'un ordre stable du monde et de la langue (7) est une condition de la liberté (et pas seulement de la vérité), et qu'une liberté devenue un arbitraire institutionnalisé se révèle le pire ennemi de la vraie liberté individuelle» (p. 252), je suis bien davantage sceptique sur la belle confiance dont témoigne Jacques Dewitte évoquant «la fin du cauchemar engendré par les utopies», censé inaugurer «le retour à une vie humaine finie et imparfaite», ainsi qu'un «retour au champ où la parole rencontre la réalité, où une relation mutuelle peut s'établir entre elles», un «retour à une situation où la pensée qui se cherche doit aussi chercher et choisir ses mots, c'est-à-dire effectuer un va-et-vient entre la chose-à-dire et les ressources de la langue héritée, sans être d'emblée captivée par tel vocable devenu quasi compulsif».

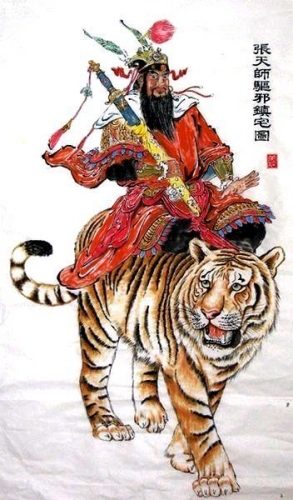

Le tigre, au sens qu'envisage Evola, c'est la force dissolvante et destructive qui entre en jeu vers la fin de tout cycle cosmique. En face d'elle, dit l'auteur, il serait vain de maintenir les formes et la structure d'une civilisation désormais révolue ; la seule chose qu'on peut faire, c'est de porter la négation au-delà de son point mort et de la faire aboutir, par une transposition consciente, non pas au néant mais à « un nouvel espace libre, qui sera peut-être la prémisse d'une nouvelle action formatrice ».

Le tigre, au sens qu'envisage Evola, c'est la force dissolvante et destructive qui entre en jeu vers la fin de tout cycle cosmique. En face d'elle, dit l'auteur, il serait vain de maintenir les formes et la structure d'une civilisation désormais révolue ; la seule chose qu'on peut faire, c'est de porter la négation au-delà de son point mort et de la faire aboutir, par une transposition consciente, non pas au néant mais à « un nouvel espace libre, qui sera peut-être la prémisse d'une nouvelle action formatrice ».