Protectionnisme et industrialisation - La théorie économique de Mihail Manoilescu

Par Bogdan C. Enache

Ex: https://blog.ignaciocarreraediciones.cl/proteccionismo-e-industrializacion-la-teoria-economica-de-mihail-manoilescu-por-bogdan-c-enache/

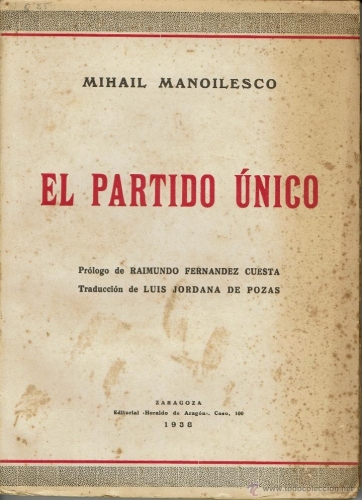

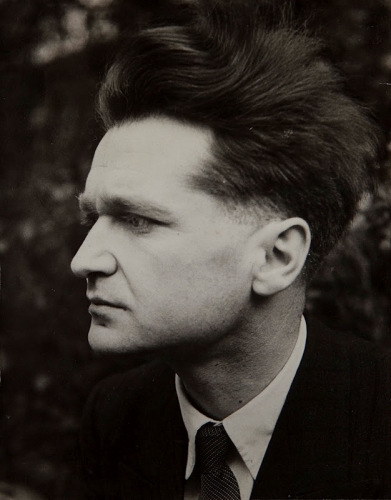

(Note de la rédaction : Mihail Manoilescu (1891-1950) était un économiste roumain très influent dans l'espace des pays périphériques, notamment en Europe de l'Est et en Amérique latine, en particulier au Brésil, au début du XXe siècle. Ses idées sur le développement de l'industrie nationale et le protectionnisme stratégique contredisent clairement l'orthodoxie néolibérale dominante, mais l'environnement dans lequel elles ont été générées et débattues présente encore de nombreuses similitudes - et donc une pertinence - avec la situation des États qui cherchent actuellement à naviguer dans un système économique mondial d'échanges asymétriques, d'exploitation commerciale et de coercition de la souveraineté aux mains d'acteurs nationaux et transnationaux et d'entités multilatérales telles que la Banque mondiale et le Fonds monétaire international).

(Version espagnole de Gonzalo Soaje, gonzalosoaje@ignaciocarreraediciones.cl)

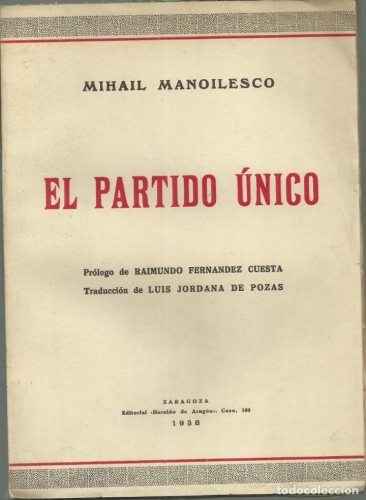

En dehors du Brésil et de la Roumanie, Mihail Manoilescu est essentiellement un économiste oublié, et même dans ce dernier pays, lorsque son nom est mentionné, il est généralement enseigné comme un théoricien du commerce ou un protectionniste, bien qu'il soit un théoricien du développement, de la croissance, du commerce et de la planification industrielle, tous réunis en un seul. En bref, il était essentiellement un théoricien implicite de la macroéconomie (1) à une époque où la macroéconomie commençait tout juste à s'imposer comme une discipline. Le peu de choses que l'économie anglo-saxonne d'après-guerre a assimilé de lui s'est produit indirectement et presque par hasard, par l'intermédiaire d'économistes en dehors du courant dominant de Paul Samuelson qui, peut-être en raison de leurs positions idéologiques "entachées", ou du peu d'attention accordée à la Roumanie après l'établissement du régime communiste, ont rarement mentionné son nom, comme ils ne l'ont pas fait, mentionnent rarement son nom, comme la "théorie des pièges du développement" de Paul Rosenstein-Rodan ou la "théorie des cycles de dépendance des produits de base" de Raul Prebisch (*), même si, dans les années 30, Manoilescu avait une énorme influence intellectuelle et politique. À l'époque, il était une sorte d'icône intellectuelle pour le groupe des économies moins développées des institutions de Genève - le Fonds monétaire international (FMI)/la Banque mondiale/l'Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC) naissante de l'ère de la Société des Nations - contre l'orthodoxie de l'économie politique de l'époque, ainsi qu'un intervenant régulier aux conférences de style Davos organisées par les régimes d'António de Oliveira Salazar (2), de Benito Mussolini (3) et aussi d'Adolf Hitler (4).

Keynes des pauvres

Bien que le lien soit rarement fait, sa théorie a plus de points communs avec celle de John Maynard Keynes qu'avec la pensée protectionniste antérieure. Dans la macroéconomie de Keynes, qui s'applique aux économies industrialisées ou développées, la théorie classique de l'équilibre de l'offre et de la demande est réfutée par l'existence de ressources inutilisées, de la pauvreté au milieu de l'abondance. Dans la théorie de Manoilescu, un programme protectionniste d'industrialisation "big push" qui brise les contraintes apparentes telles que l'avantage comparatif est basé sur l'existence de ressources sous-utilisées, d'une abondance au milieu de la pauvreté. Alors que Keynes devait s'attaquer au problème du chômage de masse dans les sociétés industrialisées, Manoilescu se concentrait sur le sous-emploi de masse dans les sociétés agraires, qui devenait également un risque politique compte tenu de l'élévation du niveau d'éducation et des attentes (en effet, le mouvement en Roumanie (**) qu'il a approché dans la dernière partie de sa carrière était, par essence, une révolte en Roumanie), en substance, une révolte de la première génération de paysans ayant reçu une éducation universitaire, une conséquence de la fracture rurale-urbaine plutôt qu'une fracture urbaine-urbaine, correspondant parfaitement à ce que Samuel Huntington définira plus tard, sans jamais faire référence à la Roumanie, comme des "révolutions rouges-vertes" simultanées dans des sociétés en mutation).

Le commerce était plus essentiel pour Manoilescu que pour Keynes, car pour une économie essentiellement agraire, en particulier une économie souffrant d'inflation en temps de guerre comme celle de la Grande-Bretagne, mais également privée de ses réserves d'or, les exportations de matières premières vers les économies industrielles étaient essentielles pour maintenir la stabilité monétaire. Il ne faut pas oublier qu'au sommet de son influence, Manoilescu était, sinon un théoricien monétaire travaillant pour l'administration coloniale britannique en Inde comme Keynes, du moins un praticien monétaire, en tant que gouverneur de la Banque nationale de Roumanie. Dans une économie où les importations consistent principalement en biens industriels, qu'ils soient destinés à l'investissement en capital ou à la consommation ostentatoire de la classe riche selon Veblen, la demande et la volatilité des prix des produits agricoles dans les pays industriels importateurs ont eu un impact négatif sur la stabilité monétaire du pays exportateur. Par conséquent, l'industrialisation par la substitution des importations et le protectionnisme promus par la théorie de Manoilescu avaient non seulement une dimension de croissance et de développement, mais aussi une dimension monétaire.

Le libre-échange en déclin

L'intérêt de Manoilescu pour l'industrialisation et les tarifs douaniers comme moyen d'y parvenir n'était pas original. Après l'ère Cobden-Chevalier des accords de libre-échange au milieu du XIXe siècle, l'Europe s'oriente vers des politiques tarifaires bien avant le début de la Première Guerre mondiale. Bien qu'elles n'aient été officiellement indépendantes qu'en 1877, les Principautés roumaines, puis les Principautés unies de Roumanie et enfin simplement la Principauté de Roumanie ont non seulement participé, bien que souvent d'office, à la vague de libre-échange de Manchester, mais ont été une sorte de berceau de la politique de laissez-faire, à tel point que certains historiens parlent aujourd'hui encore d'une grande expérience de modernité appliquée pour la première fois sur ces terres. Étant officiellement des États vassaux de l'Empire ottoman, mais sous la protection partagée des grandes puissances de l'époque et, après 1859, pratiquement indépendants, la politique de libre-échange sans restriction sur les terres roumaines convenait non seulement aux puissances rivales mais aussi, du moins à cette période de formation de l'État-nation, aux élites roumaines, qui l'ont intériorisée après le démantèlement du monopole commercial ottoman en 1828 et y ont vu un gage de sécurité, compte tenu notamment de l'importance croissante de la route fluviale du Danube, qui a donné naissance à la première institution internationale permanente : la Commission du Danube. Ainsi, le premier et unique prince dirigeant des Principautés unies de Roumanie, Alexandru Ioan Cuza, a pu déclarer au Parlement, en harmonie quasi totale avec les libéraux de 1848 et l'opposition conservatrice, que le pays était opposé à tout régime protectionniste, car la véritable bataille de politique économique de l'époque était la redistribution de la propriété foncière. Cependant, dans les décennies qui ont suivi l'indépendance du pays et la proclamation d'un royaume, dans toute l'Europe, l'idéologie du libre-échange a atteint son apogée et a simultanément commencé à perdre du terrain. En Roumanie, ce passage d'un régime de libre-échange à une protection modérée a commencé avec la loi générale sur les tarifs de 1886, renouvelée et améliorée par la loi générale sur les tarifs de Costinescu en 1906. Cette politique établie, ainsi que sa formation saint-simonienne, ont fait de Manoilescu l'un des principaux promoteurs de l'industrialisation du pays : un néo-libéral (sic !) dans le vocabulaire politique de l'époque, c'est-à-dire un libéral qui croyait en l'utilisation de l'État pour réaliser le progrès économique, contrairement aux vieux libéraux (5) qui s'accrochaient encore au libre-échange et à une politique relativement non interventionniste, qui, dans la Roumanie de l'entre-deux-guerres, ont fini par se ranger du côté du Parti national paysan plutôt que du côté des libéraux. Ce fut le cas de Gheorghe Tașcă, le plus sérieux critique de Manoilescu en Roumanie. Selon lui, et selon d'autres économistes du Parti national paysan comme Virgil Madgearu, une politique de protectionnisme visant à accélérer l'industrialisation serait préjudiciable à la population agraire et empêcherait ou retarderait la modernisation du secteur car les agriculteurs devraient payer un coût plus élevé pour acquérir des outils.

"La protection à court terme impose un coût à court terme au consommateur pour un bénéfice national à long terme ; à long terme, pour ainsi dire, elle devrait se payer d'elle-même".

Guerre commerciale avec l'Autriche-Hongrie

Les droits de douane de 1886 sont le résultat d'une longue guerre commerciale avec l'Autriche-Hongrie après la signature d'une convention de libre-échange en 1876 sur le mouvement du bétail. Bien que l'accord ait réduit les droits de douane et comporte une clause de libre transit mutuel, il ne contenait pas de réglementations non tarifaires telles que les réglementations vétérinaires, et les autorités de Vienne ont profité de cette lacune pour interdire les exportations de bétail roumain, décimant ainsi l'industrie et contribuant à convertir le secteur agricole roumain d'exportateur de bétail en producteur de céréales. Mais les tarifs douaniers de 1886 étaient également fondés sur l'argument de l'industrie naissante, aujourd'hui tout à fait dominante, de créer un marché pour la production industrielle nationale. Selon l'argument de l'industrie naissante à la Friedrich List, les tarifs douaniers restaient un coût irrécupérable pour les consommateurs, mais un coût temporairement irrécupérable nécessaire pour qu'une entreprise ou une industrie émerge là où il n'y en avait pas, face à une concurrence dévastatrice et pas toujours loyale. En bref, l'argument du tarif pour les industries naissantes était que, sans lui, il n'y aurait pas de marché de taille suffisante pour rendre la construction d'une usine plus rentable que l'importation de biens industriels, mais qu'une fois l'usine en activité, c'est-à-dire lorsque l'industrie arrive à maturité, le tarif, qui couvrait essentiellement le coût de l'investissement fixe dans la nouvelle industrie, n'est plus nécessaire et les biens de consommation produits peuvent alors être encore moins chers que ceux importés. Ainsi, la protection à court terme impose un coût à court terme au consommateur pour un bénéfice national à long terme ; à long terme, pour ainsi dire, elle devrait s'amortir.

Conformément à l'industrie naissante et à la politique de développement naissante, les tarifs généraux de 1886 et 1906 n'étaient pas des mesures protectionnistes grossières. Ils prévoyaient des exemptions pour l'importation de machines et d'autres biens d'équipement nécessaires à l'investissement dans les installations de production nationales et étaient accompagnés de lois facilitant l'accès au crédit (un autre problème dans les économies moins développées) pour les entrepreneurs en herbe, qui pouvaient toutefois faire l'objet d'abus et créer une relation clientéliste corrompue entre la politique, la bureaucratie et les entreprises. Toute cette industrie de promotion des politiques commerciales, fiscales et de crédit, déjà en place depuis la fin du XIXe siècle, constitue l'arrière-plan de la théorie de Manoilescu. Mais sa théorie, bien qu'elle puisse être considérée comme une systématisation de la politique roumaine établie - du parti libéral, en particulier - du début du 20e siècle, va au-delà des arguments protectionnistes antérieurs sur certains points importants.

Programme de Vintilă Brătianu

Le décideur économique le plus influent de la Roumanie du début du XXe siècle est Vintilă Brătianu, issu de la famille Brătianu qui a pratiquement présidé successivement le Parti national libéral depuis sa création jusqu'aux années 1930. Il est l'auteur du programme économique libéral dont le slogan électoral a saisi l'essentiel avec une concision élégante et durable, "Par nous". Alors que Manoilescu était un fonctionnaire de bas niveau, dont le milieu familial était lié au mouvement socialiste qui, en 1899, a rejoint le Parti national libéral en tant que faction autonome, Vintilă Brătianu était l'homme politiquement et financièrement bien connecté en charge du développement de l'industrie roumaine.

Pays agraire, par la proportion de l'occupation de la population et de la production nationale, la Roumanie était aussi un pays riche en ressources naturelles, surtout en ressources naturelles qui étaient alors à l'avant-garde du développement industriel, comme le pétrole. Le slogan du Parti libéral faisait avant tout référence à un débat sur la meilleure façon de promouvoir le développement de ces ressources. Le parti conservateur, bientôt remplacé, avec l'introduction du suffrage universel masculin en 1917, par le parti national paysan en tant que deuxième parti le plus important, était plus enclin à une politique de laissez-faire, comme le montre le compromis de la loi sur les mines de 1895, qui, dans le programme du parti national paysan, est devenu connu sous le nom de "politique de la porte ouverte". Cela signifiait qu'il fallait autoriser des investissements étrangers débridés, car cela correspondait aux intérêts de ses électeurs agraires orientés vers l'exportation, tandis que les libéraux promouvaient une série de politiques fiscales et réglementaires (quotas de propriété du capital, quotas de représentation de la nationalité des dirigeants, etc.), dont le point culminant était un article constitutionnel de 1923 établissant la propriété publique des ressources souterraines, conçu pour donner au gouvernement roumain et aux propriétaires roumains de l'industrie d'exploitation des ressources un rôle majeur.

Lien avec le socialisme

La théorie de Manoilescu est autant le produit de la pensée et des politiques économiques libérales de l'époque que celui des débats socialistes locaux. Le principal théoricien socialiste de la Roumanie de la fin du XIXe siècle, un pays qui avait une communauté de phalanstères de type Fourrier (***) dès 1830, était un homme appelé Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea, l'un des fondateurs du Parti roumain des travailleurs socialistes démocratiques (1893), dont la grande originalité était d'avoir remarqué que la théorie économique marxiste orthodoxe ne correspondait pas tout à fait aux faits de pays comme la Roumanie, car au lieu d'un grand prolétariat opprimé comme en Allemagne, on pouvait trouver une grande paysannerie opprimée comme en Allemagne, on pouvait trouver une grande paysannerie opprimée dont la conscience de classe fonctionnait différemment de celle des travailleurs (David Mitrany, un théoricien britannique des relations internationales né en Roumanie au milieu du 20e siècle, écrira plus tard que l'existence de cette grande paysannerie, dotée de la propriété foncière, dans des pays comme la Roumanie ou la Pologne, d'ailleurs, était précisément ce qui rendait la révolution bolchevique peu attrayante dans ces pays). L'accent mis par Manoilescu sur le produit global de la valeur du travail et sa distribution, bien que filtré par David Ricardo, remonte à ces débats socialistes et libéraux de gauche roumains sur la paysannerie. Le point culminant a été atteint dans la décennie qui a suivi le soulèvement des paysans de 1907 contre les propriétaires terriens qui louaient souvent leurs biens à des administrateurs, soulèvement qui, dans de nombreuses régions du pays, a dû être réprimé par l'armée. La paysannerie roumaine a mis le feu aux poudres, renversé un gouvernement conservateur, fait des milliers de morts selon un bilan encore indéterminé, et le bouleversement a fait la une des journaux du monde entier. Avec la génération de Mihail Manoilescu, la paysannerie roumaine va entrer dans la théorie économique.

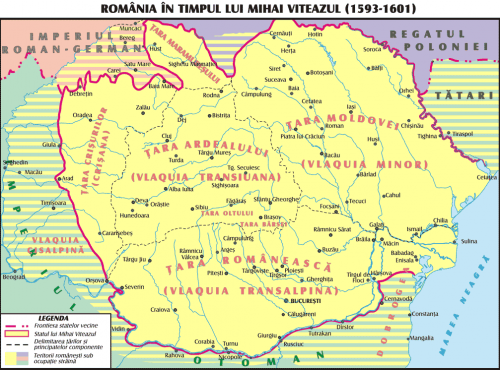

La Roumanie d'après 1918 a considérablement accru la portée de la politique de développement industriel du Parti national libéral. Bien que le pays ait plus que doublé en taille, il est resté une nation agraire. L'unification a intégré quelques provinces légèrement plus industrialisées gouvernées par les Austro-Hongrois, ainsi qu'une province pratiquement non industrielle anciennement gouvernée par la Russie, laissant le pays globalement identique à ce qu'il était auparavant. Toutefois, son potentiel et ses ambitions économiques étaient bien plus importants.

L'économie communautaire

Manoilescu développe sa théorie dans ce contexte roumain d'après-guerre, marqué par les grandes ambitions du programme économique national-libéral et les déséquilibres économiques de l'économie de guerre, à savoir l'inflation, la dépréciation de la monnaie, la dette et des économies plus fermées.

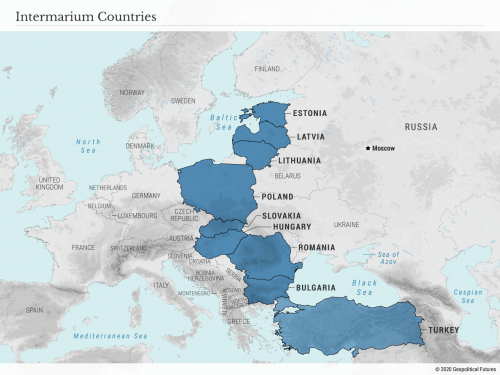

À l'époque, les débats économiques internationaux dans les forums officiels se concentrent sur le rétablissement de la stabilité monétaire d'avant-guerre, un effort auquel la Roumanie, membre du bloc aurifère de l'Union latine, se joint, bien que la plupart de ses réserves d'or aient été confisquées par l'Union soviétique. La Russie, qui y a été envoyée en sûreté en 1917 lorsque l'Allemagne et ses alliés ont envahi plus de la moitié du pays, ne parvient jamais vraiment à établir la parité d'avant-guerre et dévalue sa monnaie à plusieurs reprises. La deuxième grande question était le rétablissement du commerce et des flux de capitaux dans le contexte de l'après-guerre, qui, dans la pratique, est étroitement lié à la première question. Les propositions les plus ambitieuses à cet égard, qui sont aujourd'hui considérées comme les précurseurs de l'Union européenne, prévoyaient une zone de libre-échange à l'échelle européenne, voire une union douanière à l'échelle européenne. La région de l'ancien empire des Habsbourg ou de l'Empire austro-hongrois, qui englobe aussi en partie le royaume de Roumanie, est le plus souvent citée comme exemple dans ces propositions des effets économiques pernicieux de la fragmentation nationale, tandis que d'éminents économistes autrichiens, travaillant à l'intérieur ou à l'extérieur des bureaux de la Société des Nations, comme Gottfried Haberler ou Fritz Machlup, jetteront les bases de la théorie moderne de l'intégration économique. Cependant, aucun État n'était vraiment disposé à démanteler complètement les nombreux contrôles, réglementations et restrictions mis en place pendant la guerre et servant aujourd'hui divers groupes d'intérêts.

Outre ces deux grandes questions, un troisième grand débat économique s'est déroulé à Genève, où se trouvaient les bureaux de la Société des Nations, opposant les intérêts des pays développés ou industrialisés à ceux des économies agraires ou moins développées, représentées principalement par les pays d'Europe centrale et orientale et ceux d'Amérique latine, bien que les pays d'Europe du Sud aient également été impliqués, en ce qui concerne les termes de l'échange déloyaux (6). Le problème sera aggravé pendant l'entre-deux-guerres par l'instabilité du dosage des politiques dans les pays industrialisés, où l'insistance orthodoxe sur les taux de change fixes de l'étalon-or et la libre circulation des capitaux à la fin du XIXe siècle cohabitent avec un système désorganisé de contrôles croissants, de restrictions commerciales et de préférences coloniales, ce qui rend difficile pour les pays exportateurs de matières premières de préserver leur stabilité macroéconomique. C'est dans ces circonstances que la théorie de Manoilescu a acquis une notoriété internationale. Elle promettait aux pays en développement un moyen de prendre en main leur destin économique et l'espoir de combler l'écart avec les économies développées ou, du moins, de devenir plus autosuffisants. Le fait qu'il ait capté le sentiment de repli sur soi et de nationalisme qui régnait partout dans les années précédant et suivant la Grande Dépression faisait partie de son attrait. Aujourd'hui encore, il constitue un remarquable témoignage intellectuel, essentiel à la compréhension de cette période turbulente.

"Cette simple observation se généralise en ce que l'on appelle la constante de Manoilescu ou le ratio de Manoilescu : la productivité de l'industrie est toujours supérieure à celle de l'agriculture. Par conséquent, une politique d'industrialisation se justifie pour des raisons économiques."

Au-delà de Ricardo

La théorie de Manoilescu commence par un ensemble d'observations empiriques. Les biens agricoles, mais aussi les produits de base en général, ont une valeur par unité d'heure travaillée inférieure à celle des biens industriels, car une production plus élevée implique des coûts moyens plus élevés ou un revenu moyen plus faible. Cette simple observation se généralise en ce que l'on appelle la constante de Manoilescu ou le ratio de Manoilescu : la productivité de l'industrie est toujours supérieure à celle de l'agriculture. Par conséquent, une politique d'industrialisation se justifie pour des raisons économiques. Une politique protectionniste quasi-autarcique comme moyen de parvenir à l'industrialisation n'est pas un non-sens, puisque le coût d'opportunité des droits de douane n'est pas le surplus du consommateur auquel on renonce comme dans la théorie orthodoxe, mais la production à valeur ajoutée à laquelle on renonce du fait de l'existence du droit de douane. L'argument de l'avantage comparatif suppose un modèle simple à deux biens et deux prix, tandis que l'argument généralisé de Manoilescu révèle un modèle à deux biens et quatre prix, dans lequel la poursuite de la prescription conventionnelle de l'avantage comparatif est une solution sous-optimale. Comme dans la macroéconomie keynésienne, la prémisse cachée de l'argument était l'existence de ressources sous-développées, plutôt que sous-utilisées, telles que le capital humain, le savoir-faire et l'épargne. Cela n'a pas toujours été le cas, bien que depuis les années 1860, la Roumanie ait eu une série de politiques éducatives, dont l'enseignement primaire obligatoire, de bonnes écoles secondaires dans les villes, des programmes d'alphabétisation et de culture populaire dans les zones rurales, ainsi qu'une élite ayant reçu une éducation occidentale privée ou publique, qui, dans l'entre-deux-guerres, reproduisait et maintenait une vie universitaire, culturelle et scientifique, petite mais vivante, de niveau comparable, dont Manoilescu (et de nombreuses autres personnalités) était un produit (7).

Résultats non concluants

Bien que le programme autarcique de Manoilescu n'ait jamais été appliqué systématiquement en Roumanie, le programme national-libéral "Par nous", plus systématique, dont il s'est inspiré pour son modèle abstrait, a été la politique dominante dans l'entre-deux-guerres, à l'exception du changement de politique inopportun du gouvernement national paysan, lorsqu'en pleine Grande Dépression, alors que le protectionnisme sévissait dans le monde entier, la Roumanie a effectivement essayé son programme de libéralisation "Portes ouvertes". Et malgré les nombreuses critiques que l'on peut formuler à l'encontre de cette politique protectionniste de développement industriel durant cette période turbulente et compliquée, le fait est qu'en 1938, l'industrie, les services et la construction ont dépassé la barre des 50% de la production nationale (8). En quelque trois décennies, marquées par une guerre coûteuse et une dépression mondiale, le pays s'est transformé d'un pays essentiellement agraire, avec une économie essentiellement ferroviaire et portuaire, en un pays agro-industriel, avec quelques industries de pointe et des produits industriels surprenants tels que l'avion de chasse IAR-80, tant admiré et redouté, produit localement et détruit par les Soviétiques jusqu'à sa dernière pièce. Il est vrai que les séries reconstituées du PIB (9) pour la période montrent un taux de croissance par habitant maigre, presque plat, au cours de la période, avec de grands écarts par rapport à la moyenne, ce qui rend très difficile l'évaluation de l'effet endogène de la politique, mais le changement relatif de sa composition n'est pas contesté.

Contacts fascistes

L'esprit du fascisme

Manoilescu était lui-même un personnage controversé, pompeux et quelque peu excentrique, même à son époque, mais il reste l'économiste le plus influent, le plus oublié et le plus discrédité que la Roumanie ait jamais produit. Il est passé du statut d'ingénieur brillant et ennuyeux, d'intellectuel et de haut fonctionnaire à celui d'une personnalité politique influente et pas toujours couronnée de succès, mais sans jamais disposer d'un grand nombre de partisans.

Bien qu'il ait commencé par être une sorte de Vintilă Brătianu néo-libéral, travaillant pour le premier gouvernement libéral de l'après-Première Guerre mondiale, il dédaigna, comme beaucoup d'intellectuels de son temps, en particulier celui issu des boyards ruraux des plaines du sud de la Moldavie, la soi-disant oligarchie libérale organisée autour de la famille Brătianu et entra en politique avec le plus grand rival du Parti libéral au début des années 1920, le Parti du peuple formé par le maréchal Alexandru Averescu, un héros de guerre à la retraite.

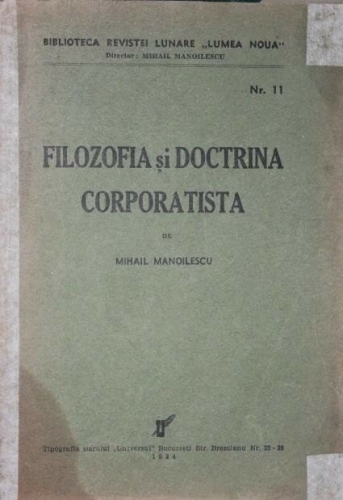

Comme un certain nombre d'intellectuels roumains et européens en général, il a rapidement développé de la sympathie et de l'admiration pour le régime de Mussolini, sur lequel il a théorisé de manière extensive et originale. Il l'a trouvé inspirant pour son efficacité apparente à relever les défis et à surmonter les contradictions de l'économie et de la société modernes, une étape logique dans l'histoire de l'organisation politique et sociale. Et, comme l'a montré l'économiste politique Philippe C. Schmitter, certaines parties de ses idées corporatistes ont perduré jusqu'à aujourd'hui, bien que sous une forme démocratique, dans les multiples organes qui rassemblent les fonctionnaires gouvernementaux, les employeurs et les syndicats de travailleurs qui existent à travers l'Europe et qui constituent une caractéristique du capitalisme continental de la fin du 20e siècle.

En 1930, il soutient le retour sur le trône du prince Carol (le futur roi Carol II), qu'il connaît personnellement depuis ses années d'école et qui avait été déshérité en 1926, sous le gouvernement libéral de Ionel Brătianu. Cela lui vaut une carrière politique de courte durée au sein du Parti national paysan, le parti au pouvoir à l'époque, qui, sous la direction de Iuliu Maniu, a pratiquement permis ce que l'on a appelé "la restauration", dont il s'est retiré après s'être brouillé avec Virgil Madgearu, l'économiste en chef du parti. Pendant un certain temps, au début des années 1930, Manoilescu était considéré comme un membre du cercle étroit des collaborateurs du roi Carol II - la clique, comme l'appelaient ses détracteurs. Cependant, les deux ne se sont pas entendus longtemps. En tant que gouverneur de la Banque nationale de Roumanie en 1931, il a refusé de renflouer une banque roumaine très importante et emblématique de l'époque, la banque Marmorosch, Blank & Co, ce qui, selon les rumeurs et spéculations politiques de la presse enfiévrée de l'époque, l'a monté contre le roi Carol ou les intérêts supposés des amis du roi dans cette affaire.

Quoi qu'il en soit, Manoilescu s'est déplacé vers l'extrême droite, a fondé son propre parti ou sa ligue corporatiste insignifiante et, à la fin des années 1930, est devenu un mécène du mouvement légionnaire, au moment où le roi Carol II commençait à le réprimer durement. En 1940, alors que le régime schmittien du roi Carol II s'effondre, il se voit néanmoins confier le rôle de bouc émissaire chargé de négocier avec la Bulgarie l'arbitrage dit de Vienne, orchestré par Mussolini et Hitler, dont l'intention officielle est de revoir les injustices très médiatisées de la paix de Versailles dans le sud-est de l'Europe, ce qui entraîne la perte de deux comtés côtiers roumains. Le vaniteux Manoilescu a rempli ce rôle dans l'espoir encore plus vain d'éviter une perte territoriale beaucoup plus importante au bénéfice de la Hongrie dans des négociations parallèles qui déboucheraient sur un diktat. Comme d'autres hauts fonctionnaires experts, il a continué à exercer cette fonction sous le régime du général Ion Antonescu, bien que sa gestion de la crise existentielle du pays à l'été 1940, avec les pertes territoriales qui s'ensuivirent sur les trois fronts, ait nui à sa réputation, même auprès des partenaires de la coalition légionnaire pro-nazie du régime militaire d'Antonescu.

Lorsque la Roumanie a rompu son alliance avec l'Allemagne et qu'a pratiquement commencé l'occupation soviétique - qui a d'abord déplacé d'importants équipements industriels, parfois même des usines entières, puis extrait du pays des quantités considérables de ressources naturelles (des céréales et du pétrole à l'uranium) à titre de réparations de guerre par le biais d'une série de coentreprises pendant une dizaine d'années - il a fait partie du premier groupe d'hommes politiques et de hauts fonctionnaires à être arrêtés. Il a réussi à rédiger ses Mémoires pendant une brève période de liberté, avant d'être emprisonné par le régime communiste roumain fantoche installé par les Soviétiques dans la tristement célèbre prison de Sighet, où il mourra plusieurs années plus tard, sans procès et enterré dans une tombe anonyme, comme de nombreuses autres personnalités politiques de l'époque de différentes obédiences.

"Sa théorie du développement industriel par substitution aux importations, fondée sur l'expérience roumaine d'avant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, était en fait une politique répandue dans l'ensemble du monde en développement dans les années 1950 et 1960".

L'oubli et le souvenir

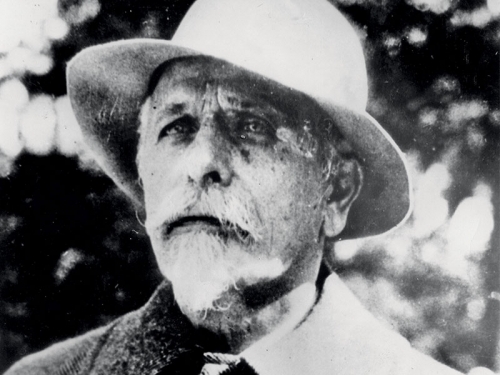

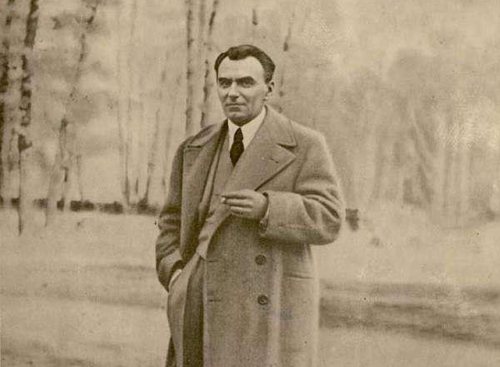

Le plus grand héritage intellectuel de Manoilescu se situe aujourd'hui en dehors de la Roumanie, notamment au Brésil, où le régime de Getúlio Vargas (photo, ci-dessous) à la fin des années 1930 a adopté ses idées comme politique économique officielle, même si son influence opérationnelle officieuse, qu'il serait très intéressant d'étudier systématiquement, est bien plus importante et peut être détectée dans divers pays au-delà de l'Amérique latine, de l'Inde post-coloniale à, en un sens, la politique économique chinoise contemporaine.

Sa théorie du développement industriel par substitution aux importations, fondée sur l'expérience roumaine d'avant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, était en fait une politique répandue dans l'ensemble du monde en développement dans les années 1950 et 1960 et s'apparente à la politique plus réussie du Japon et, plus généralement, de l'Asie de l'Est en matière d'industrialisation et de promotion des exportations, en particulier après la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Aujourd'hui, il est pratiquement inconnu aux États-Unis ou en Grande-Bretagne, où l'on s'attendrait à trouver toute la sagesse de l'économie sous une forme lisible, oublié en France et en Allemagne, où il a publié ses principaux ouvrages, tandis qu'au Brésil, il est toujours enseigné dans les départements d'économie et est connu des intellectuels et des responsables de la politique économique.

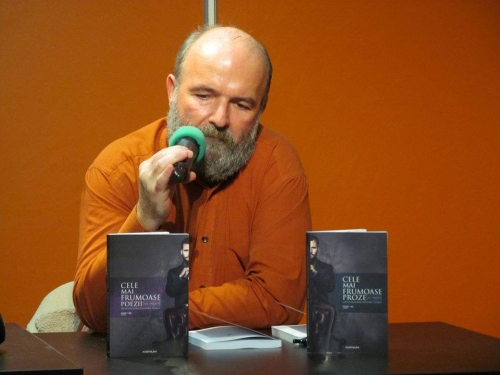

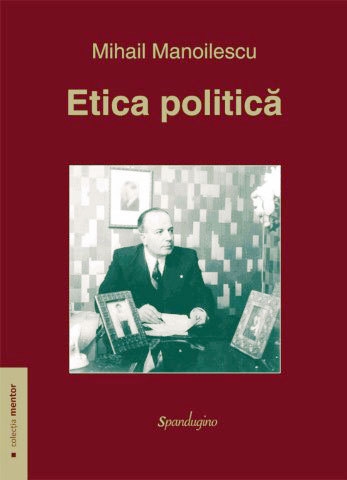

En Roumanie, il semble à première vue presque aussi oublié que n'importe où ailleurs qu'au Brésil ; aucun livre n'a été publié sur lui ou ses idées, seulement des informations éparses ici et là, et très peu de chercheurs, pratiquement aucun éminent, qui prétendent vraiment poursuivre ou engager son héritage intellectuel (ndt: on notera toutefois le livre de Cristi Pantelimon, v. ci-contre) ; mais les vestiges de sa vie et de sa pensée sont toujours là et refont inévitablement surface de temps en temps, généralement avec une certaine controverse concernant son antisémitisme, comme lorsque la Banque nationale de Roumanie a émis en avril 2016 une pièce de collection à l'effigie de Mihail Manoilescu, dans le cadre d'une série commémorant ses anciens gouverneurs.

En Roumanie, il semble à première vue presque aussi oublié que n'importe où ailleurs qu'au Brésil ; aucun livre n'a été publié sur lui ou ses idées, seulement des informations éparses ici et là, et très peu de chercheurs, pratiquement aucun éminent, qui prétendent vraiment poursuivre ou engager son héritage intellectuel (ndt: on notera toutefois le livre de Cristi Pantelimon, v. ci-contre) ; mais les vestiges de sa vie et de sa pensée sont toujours là et refont inévitablement surface de temps en temps, généralement avec une certaine controverse concernant son antisémitisme, comme lorsque la Banque nationale de Roumanie a émis en avril 2016 une pièce de collection à l'effigie de Mihail Manoilescu, dans le cadre d'une série commémorant ses anciens gouverneurs.

Le colonialisme financier mondial

La réapparition la plus notable a eu lieu sous le régime communiste de Nicolae Ceaușescu et pratiquement toutes les connaissances et utilisations qui existent actuellement en Roumanie concernant la théorie de Manoilescu remontent à cette période. Après avoir refusé de participer, et même condamné publiquement, l'invasion de la Tchécoslovaquie par le Pacte de Varsovie en 1968, Ceaușescu a cherché à éloigner la Roumanie communiste de l'hégémonie de Moscou. Sur le plan interne, cela signifiait avant tout une politique de désoviétisation culturelle et de réhabilitation des valeurs nationales, qui avait en fait commencé timidement sous son prédécesseur, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, peu après la négociation réussie du retrait des troupes soviétiques du territoire roumain en 1958, mais sans réforme réelle et profonde du système communiste en tant que tel.

Sur le plan extérieur, elle inaugure une période de diplomatie multilatérale, également initiée par Dej avec une déclaration équidistante sur le conflit de leadership sino-soviétique au sein du bloc communiste, qui comprend, entre autres, l'adhésion exceptionnelle de la Roumanie communiste au FMI et à la Banque mondiale en 1972, avec le statut de pays en développement, le même groupe de pays couvrant l'Amérique du Sud, qui a grandement apprécié et utilisé les idées de Manoilescu dans la Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes (CEPALC), une organisation qui a finalement réalisé une initiative de 1939 formulée pour la première fois à la Société des Nations à Genève.

L'éloignement de Moscou et l'ouverture de la Roumanie communiste à l'Ouest et au reste du monde à la fin des années 1960 et dans les années 1970 ont permis au régime de Ceaușescu d'accéder à des crédits en dollars, à des transferts de technologie et à des marchés étrangers pour mener à bien un ambitieux programme d'industrialisation. Bien que le régime n'ait jamais abandonné la planification centrale et les références de style soviétique, la désoviétisation culturelle, associée à l'engagement économique de l'Occident et du tiers monde, a permis, et même nécessité, la renaissance de certaines idées et pratiques économiques clés qui ont guidé la politique et la pensée économiques précommunistes de la Roumanie. Dès 1965, avant même que Ceaușescu n'accède à la succession, le régime communiste roumain s'est mobilisé pour rejeter la proposition d'un économiste soviétique, le plan dit Emil Valev, pour l'intégration économique de l'Europe de l'Est et de l'Union soviétique, le COMECOM (10), basé sur le principe de la spécialisation de la production, qui aurait transformé près de la moitié de la Roumanie d'après la Seconde Guerre mondiale en une périphérie agricole de Moscou. L'homme chargé de démolir intellectuellement le plan Valev par le Politburo roumain était Costin Murgescu, un historien de l'économie avec un passé idéologique jeune de légionnaire devenu communiste. En 1967, il se voit également confier la direction d'un nouvel institut de recherche économique directement subordonné au ministère du commerce extérieur et de la coopération internationale, bientôt connu sous le nom d'Institut de l'économie mondiale, où a été élaborée la majeure partie de la pensée économique de la dernière partie de la période communiste et où ont été formés la plupart des hauts fonctionnaires qui continuent d'occuper des postes décisionnels importants à ce jour.

Le principal ouvrage de Manoilescu y a été réimprimé en 1986, à une époque où le régime s'engageait pourtant dans une politique autarcique extrêmement coûteuse d'un point de vue social. La crise pétrolière des années 1970 et la chute du régime du Shah en Iran, avec lequel la Roumanie communiste entretenait de bonnes relations ; la hausse des taux d'intérêt sur ses engagements en dollars lorsque Paul Volcker (****) a commencé à contrôler l'inflation ; la perte de la bonne volonté des États-Unis à l'égard du régime de Ceaușescu créée lors des manœuvres diplomatiques d'Henry Kissinger pour mettre fin à la guerre du Vietnam et de la détente qui a suivi, en raison de son bilan décevant en matière de droits de l'homme ; et la concurrence accrue des pays exportateurs d'Asie de l'Est, mobiles vers le haut, bon marché et innovants, sur les marchés du tiers monde, se sont combinés au début des années 1980 pour contraindre le régime communiste roumain à mener ce que l'on appellerait aujourd'hui une politique d'austérité extrême. Contrairement à ce qui se passe dans les économies capitalistes, l'austérité, c'est-à-dire la réduction des dépenses publiques courantes pour rembourser ou contrôler les coûts de la dette encourue, n'a pas été synonyme de chômage et de faillites, mais de pénurie chronique de biens et de détérioration de leur qualité. Cependant, la marche vers l'industrialisation, inspirée par le dogme marxiste-léniniste, mais désormais renforcée par certaines des considérations de Manoilescu et d'autres pré-communistes, n'a pas été abandonnée. Au contraire. La nouvelle politique supposait non seulement la liquidation forcée des établissements ruraux et la construction de luxueux centres civiques, mais, après avoir remboursé toute la dette en dollars acquise pendant la période de détente, elle impliquait de suivre une politique largement planifiée d'octroi de crédits aux pays du tiers-monde pour les importations roumaines (bien qu'à ce jour, on constate que certaines dettes impayées de l'ère Ceausescu figurent dans les registres financiers de pays comme la Libye, Cuba, le Vietnam, etc.) Cette économie de pénurie de biens de consommation est ce qui, selon de nombreuses personnes, a finalement entraîné la chute du régime Ceausescu, tandis que l'indépendance financière vis-à-vis de l'argent soviétique et occidental est ce qui, selon certains, a retardé la transition vers une économie de marché dans le pays après 1989, par rapport à ses voisins du nord-ouest. Cet échec économique de la transition roumaine peut se mesurer assez simplement : d'un niveau de PIB par habitant presque égal, voire supérieur de 4,76%, en 1989 par rapport à celui de la Pologne, le pays était en 2017 environ 12,97% en dessous, selon les statistiques actuelles de la Banque mondiale (11).

L'éléphant dans la pièce

Les appels plutôt populistes en faveur de la protection du capital roumain et d'une nouvelle politique industrielle nationale, lancés crescendo ces dernières années par le parti social-démocrate, souvent soutenu par le parti national libéral ou par des factions indépendantes de ce dernier qui se partagent actuellement le pouvoir, ne font que rarement, voire jamais, référence au programme national libéral de développement industriel d'avant le communisme, aux travaux de Manoilescu ou à l'utilisation par le régime communiste de certaines de ses applications dans ses affaires internationales, bien qu'il existe une étrange similitude. Toutefois, bon nombre des personnes qui avancent ces arguments aujourd'hui sont en fait d'anciens étudiants et de jeunes professeurs qui l'ont lu et édité dans les années 1970, 1980 et même au début des années 1990, et qui devraient bien connaître l'histoire économique de la Roumanie, puisqu'ils en sont en partie et dans une certaine mesure les derniers protagonistes. Ainsi, Cristian Socol, le principal défenseur d'une nouvelle politique industrielle nationale, ne mentionne ni Manoilescu ni les rudiments de la planification industrielle réalisée à son époque, peu avant et pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, qui impliquait un autre économiste roumain de premier plan, Nicolae Georgescu-Roegen, Il a préféré faire la publicité de ses conseils politiques en se référant aux expériences françaises et néerlandaises plus prestigieuses de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, ou au mieux en faisant une référence passagère aux développements brésiliens ultérieurs de ses idées, bien que les observateurs experts puissent facilement lire entre les lignes.

Notes sur la révolution à venir

Et le fait que la Commission nationale pour la stratégie et la prévision, récemment rebaptisée, qui est censée remplir les fonctions de planification et de prévision indicatives des institutions équivalentes fondées par Jean Monnet et Jan Tinbergen à l'apogée de la planification stratégique, a été dotée par le gouvernement social-démocrate de Viorica Dăncilă d'un comité d'anciens membres du Conseil national de planification de l'époque communiste, une institution d'un type très différent, dont la planification était impérative, remplaçant le marché sans le compléter ni le guider. Le gel intellectuel de l'ère communiste, suivi d'une transition dysfonctionnelle et plutôt décevante, a empêché un développement significatif, et pendant longtemps même la reconnaissance, de la théorie, ou de pratiquement toute théorie, en Roumanie, mais très peu de personnes de cette génération allaient réellement contester de manière critique son héritage. Dans un pays dépourvu d'une classe d'affaires et d'une culture capitaliste historiquement fortes, l'étatisme et le dirigisme tendent à être, par défaut, l'idéologie économique préférée des élites, malgré des flirts post-communistes plutôt limités, par circonstance et par nécessité, avec l'idéologie du marché libre.

Entre-temps, la théorie et la politique économiques se sont enrichies même en ce qui concerne la politique de développement industriel, offrant des raisons plutôt orthodoxes basées sur les échecs de coordination, les problèmes d'information et les économies d'agglomération pour que le gouvernement manipule les résultats du marché, alors que l'adhésion de la Roumanie à l'Union européenne (qui, en substance, consiste en une union douanière) est un facteur majeur du développement économique du pays, qui consiste essentiellement en une union douanière et un marché commun) rend l'accent mis par Manoilescu sur les droits de douane et les restrictions à l'investissement direct étranger en tant qu'instruments politiques assez problématique à poursuivre au niveau national, du moins compte tenu des engagements internationaux actuels, soulignant les limites de l'expérience passée.

Notes

(*) Économiste argentin et ancien directeur de la Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes (CEPALC).

(**) La Garde de Fer ou Légion de l'Archange Michel, un mouvement fondé en 1927.

(***) Communauté de production et de résidence théorisée par le socialiste utopique français Charles Fourier comme base de son système social.

(****) Économiste américain et directeur de la Réserve fédérale sous les présidences de Jimmy Carter et de Ronald Reagan, de 1979 à 1987.

(1) Dans le sens où Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira, l'un des derniers continuateurs brésiliens de la théorie de Manoilescu, parle de la macroéconomie du développementalisme.

(2) Le romancier portugais José Saramago, lauréat du prix Nobel, décrit l'émotion produite par l'économiste roumain lors d'un tel événement dans son roman L'année de la mort de Ricardo Reis, ce qui peut donner au lecteur une idée de la raison pour laquelle les théories de Manoilescu ont été plus largement acceptées et développées au Brésil.

(3) Le livre de Manoilescu sur la théorie politique et l'économie, Le siècle du corporatisme (1936), a été approuvé avec enthousiasme par le dirigeant fasciste italien comme une description fidèle de l'économie politique de l'Italie fasciste.

(4) Manoilescu a contribué et publié dans le journal du Kiel Institute für Weltwirtschaft, la principale institution de recherche économique internationale en Allemagne et la plus ancienne au monde. Raúl Prebisch y a lu son travail.

(5) La division entre les nouveaux ou néolibéraux et les anciens libéraux dans la Roumanie du début du XXe siècle, qui est marquée par le livre de Ștefan Zeletin, Le néolibéralisme (1927), n'était pas une division entre des générations biologiques, car Mihail Manoilescu et Gheorghe Tașcă, par exemple, avaient fondamentalement le même âge et venaient même du même comté, mais plutôt une division entre deux générations de dirigeants à la tête du Parti national libéral au tournant du siècle. Quoi qu'il en soit, Zeletin donne une explication roumaine de la transition visible dans toute l'Europe continentale, et plus tard aussi en Grande-Bretagne, d'une idéologie libérale de laissez-faire à une idéologie plus protectionniste et interventionniste.

(6) Dans le cas de la Roumanie, par exemple, le rapport entre la valeur d'une tonne métrique d'exportations et la valeur d'une tonne métrique d'importations passe d'une fourchette de 0,20 à 0,35 entre 1901 et 1915 à une fourchette de 0,06 à 0,19 entre 1919 et 1937, voir. Andrei, Tudorel (ed.), România, un secol de istorie : date statistice , Editura Institutului Național de Statistică, Bucarest, 2018, p. 407.

(7) Ainsi, par exemple, le taux d'alphabétisation, malgré des disparités régionales persistantes, a bondi de 19,6% de la population en 1899 à 61,8% en 1930. Seulement 1,1 % de la population (1,4 % d'hommes, 0,6 % de femmes) avait une formation universitaire cette année-là.

(8) Selon l'Étude économique de l'Europe, publiée à Genève en 1949, en 1938, la part de l'industrie dans le revenu national de la Roumanie était de 16,9%, les services de 39%, la construction de 5,6% et l'agriculture de 38,4%. La valeur nette de la production industrielle roumaine a été estimée à 253 millions de dollars aux prix de 1938.

(9) Les séries de données historiques proviennent d'Axenciuc (2012) et de Maddison (2018). Voir aussi Voinea, Liviu (ed.), Un veac de sinceritate. Recuperarea memoriei pierdute a economiei românești 1918-2018, Editura Publica, Bucarest, 2018.

(10) Le Conseil d'assistance économique mutuelle, l'organisation économique du bloc de l'Est, fondé par l'Union des républiques socialistes soviétiques en 1949 en réponse au plan Marshall américain et aux dernières initiatives de l'Europe occidentale.

(11) Les deux chiffres sont exprimés en prix courants du dollar US, tels qu'ils figurent dans les données des comptes nationaux de la Banque mondiale et les fichiers de données des comptes nationaux de l'Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques (OCDE).

Dès la campagne menant à sa première élection, Klaus Iohannis – suivi en cela par la quasi-totalité de la « droite » roumaine rassemblée autour de lui – a systématiquement évacué la politique de son discours électoral.

Dès la campagne menant à sa première élection, Klaus Iohannis – suivi en cela par la quasi-totalité de la « droite » roumaine rassemblée autour de lui – a systématiquement évacué la politique de son discours électoral. En Roumanie, dès sa campagne de 2014, non content de dénoncer la présence, dans les rangs de la « gauche » roumaine, de quelques personnalités soupçonnées de malversations, Klaus Iohannis a décidé de faire de ses adversaires « socio-démocrates » (à vrai dire : populistes) « le parti de la corruption », tandis que son propre camp (de facto libéral à la Macron) cessait de se définir comme la « droite » roumaine, pour devenir le camp « du travail bien fait ». Ce remplacement relativement brutal (quoique non dénué de précédents dans la vie politique roumaine de l’après-1989) de la politique par la morale a été accompagné :

En Roumanie, dès sa campagne de 2014, non content de dénoncer la présence, dans les rangs de la « gauche » roumaine, de quelques personnalités soupçonnées de malversations, Klaus Iohannis a décidé de faire de ses adversaires « socio-démocrates » (à vrai dire : populistes) « le parti de la corruption », tandis que son propre camp (de facto libéral à la Macron) cessait de se définir comme la « droite » roumaine, pour devenir le camp « du travail bien fait ». Ce remplacement relativement brutal (quoique non dénué de précédents dans la vie politique roumaine de l’après-1989) de la politique par la morale a été accompagné :

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Comme produit de ses réflexions, une théorie entièrement nouvelle sur les processus de formation culturelle émerge, puisqu'il a compris l'homme lui-même comme une sorte de mutation ontologiquement culturelle, la culture étant une réponse imagée ou métaphorique de l'homme pour comprendre le mystère qui se trouve au-delà de l'horizon. L'horizon, pour Blaga, est une sorte d'atmosphère axiologique, d'orientation ou de forme, capable de donner un sens à la création culturelle. La culture est donc une manifestation ou une cristallisation anthropologique et géosophique d'horizons spatiaux subconscients.

Comme produit de ses réflexions, une théorie entièrement nouvelle sur les processus de formation culturelle émerge, puisqu'il a compris l'homme lui-même comme une sorte de mutation ontologiquement culturelle, la culture étant une réponse imagée ou métaphorique de l'homme pour comprendre le mystère qui se trouve au-delà de l'horizon. L'horizon, pour Blaga, est une sorte d'atmosphère axiologique, d'orientation ou de forme, capable de donner un sens à la création culturelle. La culture est donc une manifestation ou une cristallisation anthropologique et géosophique d'horizons spatiaux subconscients.

Le livre de Claudio Mutti est un outil précieux pour comprendre le passé gardiste d'Eliade. C'est un livre petit mais important, qui présente une recherche méticuleuse des sources, une opération qui n'est certainement pas facile, puisque pendant la période de la dictature en Roumanie, beaucoup de documents ont été détruits. Il s'agit d'un ouvrage qui éclaire la période all'ant de 1936 à 1938, alors qu'Eliade était membre du mouvement de la Légion de l'Archange Michel, ou Garde de Fer, comme on l'appelle souvent en Europe occidentale. Cette relecture actualisée de l'ouvrage que Mutti a consacré en 1989 au célèbre historien des religions démontre une fois de plus combien le savant italien est un point de référence pour approfondir le "légionnaire" Eliade.

Le livre de Claudio Mutti est un outil précieux pour comprendre le passé gardiste d'Eliade. C'est un livre petit mais important, qui présente une recherche méticuleuse des sources, une opération qui n'est certainement pas facile, puisque pendant la période de la dictature en Roumanie, beaucoup de documents ont été détruits. Il s'agit d'un ouvrage qui éclaire la période all'ant de 1936 à 1938, alors qu'Eliade était membre du mouvement de la Légion de l'Archange Michel, ou Garde de Fer, comme on l'appelle souvent en Europe occidentale. Cette relecture actualisée de l'ouvrage que Mutti a consacré en 1989 au célèbre historien des religions démontre une fois de plus combien le savant italien est un point de référence pour approfondir le "légionnaire" Eliade.

En Roumanie, il semble à première vue presque aussi oublié que n'importe où ailleurs qu'au Brésil ; aucun livre n'a été publié sur lui ou ses idées, seulement des informations éparses ici et là, et très peu de chercheurs, pratiquement aucun éminent, qui prétendent vraiment poursuivre ou engager son héritage intellectuel (ndt: on notera toutefois le livre de Cristi Pantelimon, v. ci-contre) ; mais les vestiges de sa vie et de sa pensée sont toujours là et refont inévitablement surface de temps en temps, généralement avec une certaine controverse concernant son antisémitisme, comme lorsque la Banque nationale de Roumanie a émis en avril 2016 une pièce de collection à l'effigie de Mihail Manoilescu, dans le cadre d'une série commémorant ses anciens gouverneurs.

En Roumanie, il semble à première vue presque aussi oublié que n'importe où ailleurs qu'au Brésil ; aucun livre n'a été publié sur lui ou ses idées, seulement des informations éparses ici et là, et très peu de chercheurs, pratiquement aucun éminent, qui prétendent vraiment poursuivre ou engager son héritage intellectuel (ndt: on notera toutefois le livre de Cristi Pantelimon, v. ci-contre) ; mais les vestiges de sa vie et de sa pensée sont toujours là et refont inévitablement surface de temps en temps, généralement avec une certaine controverse concernant son antisémitisme, comme lorsque la Banque nationale de Roumanie a émis en avril 2016 une pièce de collection à l'effigie de Mihail Manoilescu, dans le cadre d'une série commémorant ses anciens gouverneurs.

La Roumanie, comme d'autres États européens, est clairement confrontée au problème des fausses alliances. Ce syntagme a été utilisé dans la longue réflexion que le géopolitologue et général autrichien Jordis von Lohausen a consacrée au destin géopolitique de l'Europe après la Seconde Guerre mondiale dans son ouvrage Mut zur Macht. Denken in Kontinenten (1). Lohausen est un chercheur d'autant plus intéressant qu'il propose souvent une solution aux conflits géopolitiques passés sur le mode d'une histoire contrefactuelle, étant extrêmement crédible dans ce registre. Ses réflexions et ses solutions géopolitiques visent à renforcer une conception qui n'était pas pleinement réalisée au moment historique où les événements ont eu lieu, mais qui est encore plus évidente après la fin de ces événements. Ainsi, son continentalisme et son eurasianisme sont d'autant plus crédibles qu'au moment de la Seconde Guerre mondiale (et aussi de la Première), ils n'ont pas été pleinement soutenus par les puissances européennes, avec les conséquences qui sont sous nos yeux aujourd'hui : une Europe qui se trouve, pratiquement, à la discrétion des puissances thalassocratiques (surtout les États-Unis) et de l'OTAN (où l'influence des États-Unis est presque totale) ; une Europe qui ne peut pas résoudre ses problèmes, non pas à cause d'un manque de capacité bureaucratique, mais à cause d'un manque de vision globale d'un point de vue géopolitique et géostratégique. Le moment est venu pour l'Europe de choisir entre des alliances conjoncturelles et souvent opportunistes (celles avec les puissances thalassocratiques) et des alliances durables et logiques (peut-être plus difficiles à articuler pour le moment) avec les puissances continentales, en particulier la Russie.

La Roumanie, comme d'autres États européens, est clairement confrontée au problème des fausses alliances. Ce syntagme a été utilisé dans la longue réflexion que le géopolitologue et général autrichien Jordis von Lohausen a consacrée au destin géopolitique de l'Europe après la Seconde Guerre mondiale dans son ouvrage Mut zur Macht. Denken in Kontinenten (1). Lohausen est un chercheur d'autant plus intéressant qu'il propose souvent une solution aux conflits géopolitiques passés sur le mode d'une histoire contrefactuelle, étant extrêmement crédible dans ce registre. Ses réflexions et ses solutions géopolitiques visent à renforcer une conception qui n'était pas pleinement réalisée au moment historique où les événements ont eu lieu, mais qui est encore plus évidente après la fin de ces événements. Ainsi, son continentalisme et son eurasianisme sont d'autant plus crédibles qu'au moment de la Seconde Guerre mondiale (et aussi de la Première), ils n'ont pas été pleinement soutenus par les puissances européennes, avec les conséquences qui sont sous nos yeux aujourd'hui : une Europe qui se trouve, pratiquement, à la discrétion des puissances thalassocratiques (surtout les États-Unis) et de l'OTAN (où l'influence des États-Unis est presque totale) ; une Europe qui ne peut pas résoudre ses problèmes, non pas à cause d'un manque de capacité bureaucratique, mais à cause d'un manque de vision globale d'un point de vue géopolitique et géostratégique. Le moment est venu pour l'Europe de choisir entre des alliances conjoncturelles et souvent opportunistes (celles avec les puissances thalassocratiques) et des alliances durables et logiques (peut-être plus difficiles à articuler pour le moment) avec les puissances continentales, en particulier la Russie.

Dans l'entre-deux-guerres, un célèbre sociologue et philosophe roumain (martyr du changement brutal de la situation géopolitique européenne en 1945), Mircea Vulcănescu (1904-1952), a proposé une vision intéressante des forces qui ont façonné en profondeur la civilisation roumaine. Sa théorie peut être appelée "théorie des tentations historiques" et consiste principalement en la théorisation subtile d'un mécanisme d'"éternel retour" aux origines du peuple roumain à travers le souvenir (plus ou moins une anamnèse de type platonicien) des éléments constitutifs de son ethnogenèse. Vulcănescu, cependant, ne privilégie pas l'aspect ethnique ou anthropologique au sens biologique, mais plutôt l'aspect strictement culturel et civilisationnel. "Chaque peuple, chaque âme populaire peut être caractérisée par un certain dosage de ces tentations, qui reproduisent dans son architecture interne l'interpénétration dans l'actualité spirituelle des vicissitudes historiques par lesquelles le peuple respectif est passé" (6).

Dans l'entre-deux-guerres, un célèbre sociologue et philosophe roumain (martyr du changement brutal de la situation géopolitique européenne en 1945), Mircea Vulcănescu (1904-1952), a proposé une vision intéressante des forces qui ont façonné en profondeur la civilisation roumaine. Sa théorie peut être appelée "théorie des tentations historiques" et consiste principalement en la théorisation subtile d'un mécanisme d'"éternel retour" aux origines du peuple roumain à travers le souvenir (plus ou moins une anamnèse de type platonicien) des éléments constitutifs de son ethnogenèse. Vulcănescu, cependant, ne privilégie pas l'aspect ethnique ou anthropologique au sens biologique, mais plutôt l'aspect strictement culturel et civilisationnel. "Chaque peuple, chaque âme populaire peut être caractérisée par un certain dosage de ces tentations, qui reproduisent dans son architecture interne l'interpénétration dans l'actualité spirituelle des vicissitudes historiques par lesquelles le peuple respectif est passé" (6).

Dans la culture du 20e siècle, la Roumanie a joué un rôle central. L'étude et la recherche étaient les domaines dans lesquels les jeunes intellectuels de ce pays tentaient de surmonter la marginalité existentielle résultant du fait d'être né dans une province "orientale". Pensez, parmi beaucoup d'autres, à Cioran, Eliade, Noica, Vulcănescu, pour ne citer que quelques exemples exemples éminents de la " jeune génération " formée à l'école de Nae Ionescu, qui était considéré comme un maître incontesté par ces jeunes érudits précoces, à l'esprit très vif. Une biographie reconstituant la vie intellectuelle de Ionescu est désormais disponible pour les lecteurs italiens. Il est dû à la plume de Tatiana Niculescu, Nae Iounescu. Il seduttore di una generazione (= Le séducteur d'une génération), qui vient de paraître dans le catalogue de la maison Castelvecchi, édité par Horia C. Cicortaş et Igor Tavilla (pour les commandes : 06/8412007 ; info@castelvecchieditore.com, pp. 240, euro 22.00).

Dans la culture du 20e siècle, la Roumanie a joué un rôle central. L'étude et la recherche étaient les domaines dans lesquels les jeunes intellectuels de ce pays tentaient de surmonter la marginalité existentielle résultant du fait d'être né dans une province "orientale". Pensez, parmi beaucoup d'autres, à Cioran, Eliade, Noica, Vulcănescu, pour ne citer que quelques exemples exemples éminents de la " jeune génération " formée à l'école de Nae Ionescu, qui était considéré comme un maître incontesté par ces jeunes érudits précoces, à l'esprit très vif. Une biographie reconstituant la vie intellectuelle de Ionescu est désormais disponible pour les lecteurs italiens. Il est dû à la plume de Tatiana Niculescu, Nae Iounescu. Il seduttore di una generazione (= Le séducteur d'une génération), qui vient de paraître dans le catalogue de la maison Castelvecchi, édité par Horia C. Cicortaş et Igor Tavilla (pour les commandes : 06/8412007 ; info@castelvecchieditore.com, pp. 240, euro 22.00).

Entre les deux hommes, presque des contemporains, séparés par seulement quatre ans de vie, est née une amitié qui - entre les hauts et les bas de l’existence, comme cela arrive souvent aux hommes dotés de caractère et de profondeur spirituelle - a duré jusqu'à la fin des jours d'Eliade (Cioran le suivra en 1995). Un monument littéraire à cette relation de longue durée entre deux géants de l’esprit est Una segreta complicità (Adelphi), la première édition mondiale de la correspondance entre les deux exilés roumains, d'où émerge une incroyable complémentarité, mêlée d'antagonisme, souvent non exempte de virulente controverse, comme le rappellent les deux éditeurs, Massimo Carloni et Horia Corneliu Cicortaş, mais toujours sous la bannière d’une entente secrète que Cioran a témoigné à Eliade le jour de Noël 1935 :

Entre les deux hommes, presque des contemporains, séparés par seulement quatre ans de vie, est née une amitié qui - entre les hauts et les bas de l’existence, comme cela arrive souvent aux hommes dotés de caractère et de profondeur spirituelle - a duré jusqu'à la fin des jours d'Eliade (Cioran le suivra en 1995). Un monument littéraire à cette relation de longue durée entre deux géants de l’esprit est Una segreta complicità (Adelphi), la première édition mondiale de la correspondance entre les deux exilés roumains, d'où émerge une incroyable complémentarité, mêlée d'antagonisme, souvent non exempte de virulente controverse, comme le rappellent les deux éditeurs, Massimo Carloni et Horia Corneliu Cicortaş, mais toujours sous la bannière d’une entente secrète que Cioran a témoigné à Eliade le jour de Noël 1935 : De même, la différence entre deux visions du monde opposées concernant l'Est et l'Ouest apparaît chez les deux hommes, Cioran cherchant pour ainsi dire à trouver un Est dans l'Ouest, et Eliade étant poussé à aller dans la direction opposée, sans toutefois se laisser aller à l'exotisme facile, tant à la mode à l’époque que maintenant. Il écrit à Cioran le 23 avril 1941 depuis Lisbonne, où il séjourne en tant qu'attaché de presse à la légation roumaine (le magnifique Journal portugais, publié en italien par Jaca Book, témoigne de son séjour en terres lusitaniennes) : "Vivant face à l'Atlantique, je me sens de plus en plus attiré par des géographies qui m'étaient autrefois insignifiantes. J'essaie de trouver mon salut en dehors de l'Europe. Vasco de Gama est toujours arrivé en Inde".

De même, la différence entre deux visions du monde opposées concernant l'Est et l'Ouest apparaît chez les deux hommes, Cioran cherchant pour ainsi dire à trouver un Est dans l'Ouest, et Eliade étant poussé à aller dans la direction opposée, sans toutefois se laisser aller à l'exotisme facile, tant à la mode à l’époque que maintenant. Il écrit à Cioran le 23 avril 1941 depuis Lisbonne, où il séjourne en tant qu'attaché de presse à la légation roumaine (le magnifique Journal portugais, publié en italien par Jaca Book, témoigne de son séjour en terres lusitaniennes) : "Vivant face à l'Atlantique, je me sens de plus en plus attiré par des géographies qui m'étaient autrefois insignifiantes. J'essaie de trouver mon salut en dehors de l'Europe. Vasco de Gama est toujours arrivé en Inde". Leur relation épistolaire et humaine survivra à cette Europe dont ils avaient tous deux rédigé le rapport d’autopsie, vivant en ses derniers moments comme l’on vit la fin d'une saison, avec cette amère conscience qui transparaît d'une note du Journal portugais d'Eliade datant de novembre 1942 (un an après la lettre précitée) et écrite dans la ville espagnole d'Aranjuez avec ses mille palais et jardins caressés par le Tage : "Le palais rose. Les magnolias. A côté du palais, des groupes de statues en marbre. Vous pouvez entendre le bruit des eaux du Tage qui se déversent dans la cascade. Une promenade dans le parc du palais : de nombreuses feuilles sur le sol. L'automne est arrivé. Les rossignols. Le minuscule labyrinthe d'arbustes. Des bancs, des ronds-points. Nous sommes les derniers". J'aime à penser que dans cette lointaine année 1942, dans l'œil de la tempête, Eliade parlait implicitement de lui et de son vieil ami, à des centaines de kilomètres de là, mais partageant avec lui un destin bien plus élevé, que même la tragédie européenne qui a suivi n'a pas pu écraser.

Leur relation épistolaire et humaine survivra à cette Europe dont ils avaient tous deux rédigé le rapport d’autopsie, vivant en ses derniers moments comme l’on vit la fin d'une saison, avec cette amère conscience qui transparaît d'une note du Journal portugais d'Eliade datant de novembre 1942 (un an après la lettre précitée) et écrite dans la ville espagnole d'Aranjuez avec ses mille palais et jardins caressés par le Tage : "Le palais rose. Les magnolias. A côté du palais, des groupes de statues en marbre. Vous pouvez entendre le bruit des eaux du Tage qui se déversent dans la cascade. Une promenade dans le parc du palais : de nombreuses feuilles sur le sol. L'automne est arrivé. Les rossignols. Le minuscule labyrinthe d'arbustes. Des bancs, des ronds-points. Nous sommes les derniers". J'aime à penser que dans cette lointaine année 1942, dans l'œil de la tempête, Eliade parlait implicitement de lui et de son vieil ami, à des centaines de kilomètres de là, mais partageant avec lui un destin bien plus élevé, que même la tragédie européenne qui a suivi n'a pas pu écraser.

Nous y sommes car nous avons devant nous une conspiration avec des moyens techniques et financiers formidables, une conspiration formée exclusivement de victimes et de bourreaux volontaires. On a vu les bras croisés le cauchemar s’asseoir depuis la mondialisation des années 90 et la lutte contre le terrorisme, puis progresser cette année à une vitesse prodigieuse, cauchemar que rien n’interrompt en cette Noël de pleine apostasie catholique romaine. La dégoutante involution du Vatican s’est faite dans la totale indifférence du troupeau de nos bourgeois cathos, et on comprend ce qui pouvait motiver Drumont, Bloy ou Bernanos contre une telle engeance de bien-pensants. Un pour cent ou un pour mille de résistants ? Le reste s’est assis masqué et a applaudi.

Nous y sommes car nous avons devant nous une conspiration avec des moyens techniques et financiers formidables, une conspiration formée exclusivement de victimes et de bourreaux volontaires. On a vu les bras croisés le cauchemar s’asseoir depuis la mondialisation des années 90 et la lutte contre le terrorisme, puis progresser cette année à une vitesse prodigieuse, cauchemar que rien n’interrompt en cette Noël de pleine apostasie catholique romaine. La dégoutante involution du Vatican s’est faite dans la totale indifférence du troupeau de nos bourgeois cathos, et on comprend ce qui pouvait motiver Drumont, Bloy ou Bernanos contre une telle engeance de bien-pensants. Un pour cent ou un pour mille de résistants ? Le reste s’est assis masqué et a applaudi. Nous sommes donc à la veille d’une gigantesque extermination et d’un total arraisonnement. Et tout cela se passe facilement et posément, devant les yeux des victimes consentantes ou indifférentes que nous sommes. Nous payons ici l’addition de la technique et de notre soumission. De Chateaubriand à Heidegger elle a été rappelée par tous les penseurs (voyez ici mes chroniques). C’est cette dépendance monotone qui nous rend incapables de nous défendre contre les jobards de l’économie et de l’administration qui aujourd’hui veulent faire de leur troupeau humain le bifteck de Soleil vert ou les esclaves en laisse électronique. Et le troupeau est volontaire, enthousiaste comme disait Céline avant juin 40.

Nous sommes donc à la veille d’une gigantesque extermination et d’un total arraisonnement. Et tout cela se passe facilement et posément, devant les yeux des victimes consentantes ou indifférentes que nous sommes. Nous payons ici l’addition de la technique et de notre soumission. De Chateaubriand à Heidegger elle a été rappelée par tous les penseurs (voyez ici mes chroniques). C’est cette dépendance monotone qui nous rend incapables de nous défendre contre les jobards de l’économie et de l’administration qui aujourd’hui veulent faire de leur troupeau humain le bifteck de Soleil vert ou les esclaves en laisse électronique. Et le troupeau est volontaire, enthousiaste comme disait Céline avant juin 40. Voilà pourquoi les parlements et les administrations ne seront arrêtés par rien. Et le troupeau renâclera peut-être trois minutes mais il se soumettra comme les autres fois sauf qu’ici ce sera global et simultané. Quant aux minorités rebelles (1% tout au plus) le moins que l’on puisse dire c’est qu’elles ne sont pas très agissantes…

Voilà pourquoi les parlements et les administrations ne seront arrêtés par rien. Et le troupeau renâclera peut-être trois minutes mais il se soumettra comme les autres fois sauf qu’ici ce sera global et simultané. Quant aux minorités rebelles (1% tout au plus) le moins que l’on puisse dire c’est qu’elles ne sont pas très agissantes… Et comme Chateaubriand Gheorghiu rappelle :

Et comme Chateaubriand Gheorghiu rappelle :

It is important to consider that, over time, Manoilescu not only acquired sympathy for Nazi and fascist regimes, but also he was a believer in these social and political models. The subsequent situation of Soviet dominance in Romania, mainly after the end of the Romanian-German alignment, made impossible any attempt or intention to adopt his economic conceptions.

It is important to consider that, over time, Manoilescu not only acquired sympathy for Nazi and fascist regimes, but also he was a believer in these social and political models. The subsequent situation of Soviet dominance in Romania, mainly after the end of the Romanian-German alignment, made impossible any attempt or intention to adopt his economic conceptions.

Emil Cioran

Emil Cioran A rare and stimulating combination in Cioran’s writings: unsentimental observation and intense pathos.

A rare and stimulating combination in Cioran’s writings: unsentimental observation and intense pathos. But fascism cannot work miracles. Politics must work with the human material and historical trajectory that one has. That is being true to oneself. To wish for total transformation and the tabula rasa is to invite disaster. Such revolutions are generally an exercise in self-harm. Once the passions and intoxications have settled, one finds the nation stunted and lessened: by civil war, by tyranny, by self-mutilation and deformation in the stubborn in the name of utopian goals. The historic gap with the ‘advanced’ nations is widened further still by the ordeal.

But fascism cannot work miracles. Politics must work with the human material and historical trajectory that one has. That is being true to oneself. To wish for total transformation and the tabula rasa is to invite disaster. Such revolutions are generally an exercise in self-harm. Once the passions and intoxications have settled, one finds the nation stunted and lessened: by civil war, by tyranny, by self-mutilation and deformation in the stubborn in the name of utopian goals. The historic gap with the ‘advanced’ nations is widened further still by the ordeal.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher. Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63).

Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63). France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

From this period until his definitive move to France (1941), Cioran would constantly ideologize his discourse, fight against pacifism as well as skepticism, and promote the fanaticization of the masses and the resort to violence in order to destroy critical thought – convinced of having discovered in Hitlerism a model dictatorship to be urgently imported into his own country. He also sought – with force, lyricism, and aggressiveness – to put before his compatriots the following choice: a mission or despair; the birth of a history or rotting in time’s ash-heap; the transfiguring leap or death . . . He wrote in the February 4, 1934 columns of Vremea:

From this period until his definitive move to France (1941), Cioran would constantly ideologize his discourse, fight against pacifism as well as skepticism, and promote the fanaticization of the masses and the resort to violence in order to destroy critical thought – convinced of having discovered in Hitlerism a model dictatorship to be urgently imported into his own country. He also sought – with force, lyricism, and aggressiveness – to put before his compatriots the following choice: a mission or despair; the birth of a history or rotting in time’s ash-heap; the transfiguring leap or death . . . He wrote in the February 4, 1934 columns of Vremea:

Growing up in France, I was never attracted to Emil Cioran’s nihilist and pessimistic aesthetic as a writer. Cioran was sometimes presented to us as unflinchingly realistic, as expressing something very deep and true, but too dark to be comfortable with. I recently had the opportunity to read his De l’inconvénient d’être né (On the Trouble with Being Born) and feel I can say something of the man.

Growing up in France, I was never attracted to Emil Cioran’s nihilist and pessimistic aesthetic as a writer. Cioran was sometimes presented to us as unflinchingly realistic, as expressing something very deep and true, but too dark to be comfortable with. I recently had the opportunity to read his De l’inconvénient d’être né (On the Trouble with Being Born) and feel I can say something of the man. As literally an apatride metic (he would lose his Romanian citizenship in 1946), Cioran, then, did not have much of a choice if he wished to exist a bit in postwar French intellectual life, which went from the fashionable Marxoid Jean-Paul Sartre on the left to the Jewish liberal-conservative Raymond Aron on the right. (I actually would speak highly of Aron’s work on modernity as measured, realistic, and empirical, quite refreshing as far as French writers go. Furthermore he was quite aware of Western decadence and made a convincing case for