mercredi, 14 octobre 2015

Un autre cinéma est possible

Méridien Zéro #249: "Un autre cinéma est possible"

Cette semaine, Méridien Zéro a l'honneur et l'avantage de vous proposer un entretien avec la réalisatrice Cheyenne-Marie Carron, à quelques jours de la sortie de son film Patries (le 21 octobre). L'occasion pour nous d'éclairer l'oeuvre de cet auteur atypique et de revenir sur quelques aspects du cinéma français...

A la barre et à la technique Eugène Krampon et Wilsdorf.

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Entretiens, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cheyenne-marie caron, cinéma, méridien zéro, entretien, film |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 01 octobre 2015

«De l’anti-héros au héros mauvais: apologie de l’individualisme et destruction du lien social dans les séries contemporaines»

«De l’anti-héros au héros mauvais: apologie de l’individualisme et destruction du lien social dans les séries contemporaines»

Ex: http://www.arretsurinfo.ch

Attention spoilers : cet article contient des éléments-clés de Game of Thrones, jusqu’à la saison 4 incluse, et un tout petit spoil de Desperate Housewives (saison 8). D’autres séries sont évoquées mais aucun élément-clé n’est révélé.

NB : Cet article n’engage que moi. Il se fonde grandement sur mes propres sensibilité et subjectivité et s’apparente bien plus à un fil de réflexions personnelles (qui pourraient néanmoins en intéresser d’autres) qu’à une véritable étude systématique et scientifique.

Nos héros sont des estropiés bourrés de vices. Cela peut sembler caricatural, mais c’est pourtant bien ce qui se détache d’une analyse de nos séries contemporaines.

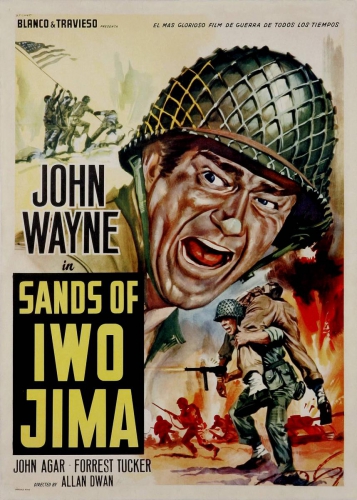

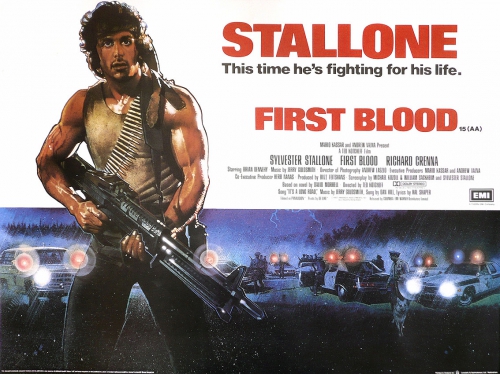

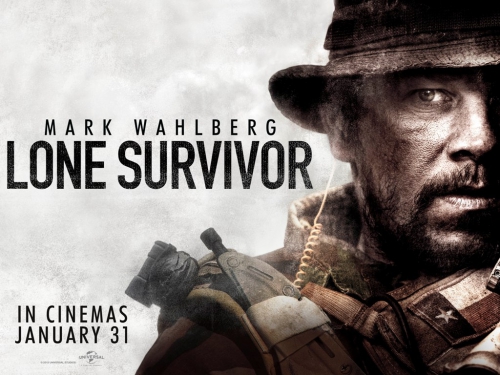

Dans un précédent article, j’ai évoqué le concept de héros. Traditionnellement, il est un personnage exemplaire, censé édifier le lecteur ou le spectateur, l’inspirer, lui présenter une conduite modèle. Il peut bien sûr avoir des défauts, des failles, mais il tend globalement à la vertu, accomplit des actions nobles. Ce concept n’a pas entièrement disparu, et l’on a des héros de ce type aujourd’hui (Harry Potter, pour n’en citer qu’un). Néanmoins, on a aussi de nombreuses séries qui présentent des héros cyniques, vicieux, mais malgré tout charismatiques (beaucoup plus que les personnages vertueux !) Qu’est-ce que cela veut dire ?

Un point tout à fait marquant est le fait que plusieurs héros souffrent d’un lourd handicap. On a par exemple Dr House et Tyrion Lannister. Ajoutons quelques précisions. House est bel et bien infirme : le muscle de sa cuisse a subi des dommages qui le gênent fortement dans ses déplacements et, surtout, engendrent une douleur difficilement tolérable, qui le rend accro aux médicaments. Tyrion Lannister est nain, ce qui n’est pas en soi un handicap, mais engendre, dans son cas, le mépris général, jusqu’à celui de sa propre famille. Tous deux ont pour point commun de compenser ce handicap (physique pour House, social pour Tyrion) par un maniement habile de la parole, ce qui les rend extrêmement brillants par rapport aux autres personnages. Tyrion explique d’ailleurs dès le début (saison 1, épisode 2) qu’il cultive son penchant intellectuel pour pallier sa petite taille et la déconsidération sociale qu’elle engendre (en des termes bien plus drôles, évidemment !). Paradoxalement, ces personnages en souffrance deviennent les plus charismatiques de la série, les plus attirants, même les plus séduisants. Et pourtant, ils sont bien loin de la vertu. House est un cynique misanthrope qui ne voit dans la médecine qu’un puzzle à résoudre et envisage la vie humaine bien plus comme un calcul arithmétique que comme une fin en soi. Il est vrai que cela donne lieu à des situations qui proposent parfois une réflexion éthique très intéressante, les autres personnages incarnant des visions différentes et soulevant des cas de conscience épineux ; mais House reste souvent celui qui a la réplique la plus cinglante, qui trouve toujours le bon mot, ce qui fait pencher implicitement la balance de son côté. Tyrion, lui, commence la série ivre et entouré de prostituées, et continue sur cette voie pendant un certain temps. Les repères se brouillent quand il rencontre Shae, ancienne prostituée, et semble trouver en elle une certaine rédemption. Le spectateur apprécie qu’il ne se jette pas sur la jeune Sansa qu’on lui a mariée de force (une attitude, il faut le dire, peu courante dans ce monde où le viol apparaît comme tout à fait anecdotique). Mais c’est pour mieux appréhender une nouvelle déchéance : il tue, presque d’un même coup, la femme qu’il aime et son propre père (acte tabou s’il en est). Mais malgré cela, Tyrion reste le personnage le plus sympathique de la série, le seul personnage drôle d’ailleurs (tout comme House).

Ce phénomène ne se cantonne pas à ces deux personnages, mais semble être plus global. Une simple étude de Game of Thrones suffirait à souligner toute l’ambiguïté axiologique dont est porteuse la série : le seul personnage clairement mauvais est, semble-t-il, Joffrey, tous les autres étant extrêmement ambivalents. Bien sûr, un personnage ne peut pas être parfait, au risque de tomber dans un sirupeux remake du Club des Cinq. Mais ce qui est dérangeant dans ces séries, c’est que les repères sont brouillés et que l’on ne distingue plus le bien du mal.

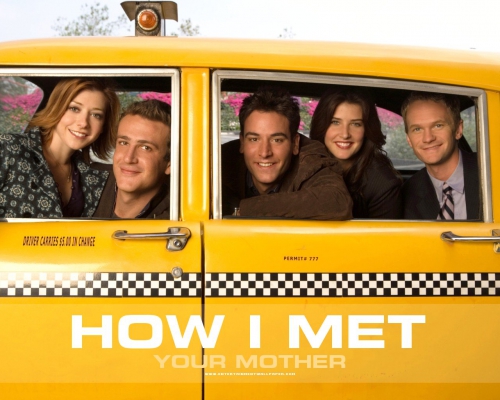

Est-il besoin de rappeler que Dexter est un tueur en série qui a un goût prononcé pour le sang et met en pratique la peine de mort (nous sommes aux États-Unis où elle est en vigueur dans la plupart des États, d’accord, mais ici le débat semble tranché d’avance) ? L’idée lumineuse du héros de Breaking Bad à qui l’on diagnostique un cancer en phase terminale est de mettre ses talents de chimiste au service de la fabrication de méthamphétamines… Barney, dans How I Met Your Mother, qui vole progressivement la vedette à Ted, à la fois dans le scénario et dans le cœur des spectateurs, n’est autre qu’un sex addict manipulateur et misogyne (et néanmoins il est celui qui nous aura fait le plus rire et qui tient le rôle central des meilleurs épisodes). Bon courage pour trouver l’ombre d’une vertu dans des séries historiques comme Rome ou Les Tudors, où les scénaristes ont même pris soin de remplir les vides laissés par l’histoire par de nouveaux vices (inceste, sadomasochisme, manipulation…). Ce serait un affront au lecteur de rappeler qu’un récit historique en dit plus sur notre temps que sur la période présentée…

Et qu’est-ce que cela nous dit, justement ? Pourquoi cherche-t-on à jouir et à nous faire jouir du vice, de la perversion, de la méchanceté, de la manipulation ? Pourquoi nos héros sont-ils malades, physiquement et psychiquement ? Pourquoi associe-t-on le charisme, l’habileté, la virtuosité à des « anti-héros », comme on entend si fréquemment ? À se demander si l’« anti » n’est pas en réalité devenu la norme. Vit-on une époque boiteuse et en souffrance, à l’image de House ? Estime-t-on plus le vice que la vertu ?

Ce qui est flagrant, c’est que ces séries développent très peu des sentiments de solidarité, de charité, de générosité. Peu d’actes sont gratuits et désintéressés ; toutes les actions des personnages semblent s’inscrire dans un vaste projet géopolitique où chacun serait un État en plein exercice de sa volonté de puissance. C’est, par exemple, particulièrement marqué dans Desperate Housewives où les relations les plus intimes que ces femmes entretiennent avec leur mari ou leurs enfants sont toutes faites de manipulations et de calculs froids. Et, paradoxalement, ces plans machiavéliques s’avèrent particulièrement divertissants, et la série devient de moins en moins intéressante quand elle se met à verser dans quelque chose de plus mielleux et moralisateur, surtout à partir du bon en avant de cinq ans à la suite de la saison 4 (à mon sens, la seule scène sincèrement touchante est celle où Gaby raccompagne Carlos, ivre, oubliant pour une fois son image sociale pour venir en aide à son mari qui a sombré dans l’alcoolisme (saison 8, épisode 5), mais c’est une appréciation tout à fait personnelle).

D’une manière générale, les séries nous présentent comme séduisants l’égoïsme, le mépris de l’autre, en somme l’individualisme. Le mot est lancé. Se pourrait-il que les séries répondent à une certaine idéologie, l’idéologie dominante, celle du néolibéralisme, du « chacun pour soi » ? Un néolibéralisme qui marche doit casser les luttes sociales ; et quoi de plus facile que de les anéantir à la racine ? En faisant l’apologie de l’individualisme et en traitant avec mépris les actions généreuses, ces séries tendent à dissoudre la solidarité qui pourrait (et devrait) se créer face à l’oppression. Margaret Thatcher l’avait dit : « Il n’y a pas de société, il n’y a que des individus ». Je ne dis pas qu’il s’agit là d’un « complot », car je sais que le mot est mal vu. On peut davantage poser l’hypothèse d’une auto-alimentation du système : on fait rire le public par le vice et l’irrespect d’autrui, il en redemande, on lui fait croire que c’est ce qu’il aime, on n’envisage plus que ce biais pour créer des scénarios, etc. Il est vrai qu’on a (que j’ai ?) du mal à envisager un humour sans une bonne dose de répliques cinglantes, et elles passent souvent par le mépris.

C’est en tant que grande amatrice de séries que je m’interroge. Je m’interroge sur le bien-fondé de ce que je regarde, sur l’influence que cela peut avoir sur moi, sur nous. Est-on condamné à ne regarder que Plus belle la vie et La petite maison dans la prairie si l’on veut rester sain d’esprit (et d’âme) ? Réjouissante perspective…

Hannah Arendt disait que nous nous trouvions dans une brèche entre le passé et l’avenir (« a gap between past and future ») et que nous avions perdu le contact avec la tradition ; elle mettait son espoir dans les neoi, les nouveaux venus sur terre, qui pourraient créer à nouveau. Nietzsche a brillamment identifié la mort de Dieu qui nous a déconnectés des valeurs chrétiennes (ou religieuses au sens large) ; il en appelait de nouvelles, mais quelles sont-elles ? Spengler, quant à lui, parlait du déclin de l’Occident…

Clara Piraud

Source: brunoadrie.wordpress.com

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cinéma, films, 7ème art, sociologie, moeurs contemporaines, anti-héros |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 05 septembre 2015

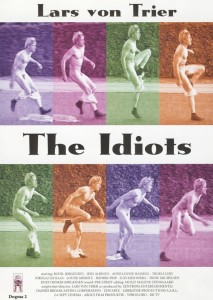

Lars von Trier’s The Idiots

Lars von Trier’s The Idiots

By Tonio Kröger

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

I. (Minor Spoilers)

The Idiots (Idioterne) is not an accessible film, and neither is it is easy to digest. The sexual content is so extreme that The Idiots is rated the same as any pornographic film in the United Kingdom, Spain, Australia, Norway, and several others. The depiction of mentally disabled individuals, both real and those merely acting as such, is alarming and controversial. During the screening at the Cannes Film Festival in 1998, film critic Mark Kermode was removed from the venue for exclaiming, ‘Il est merde!’ He was responding less to the actual quality of the film, and more to its remarkably provocative and unsettling subject matter.

Lars von Trier, of course, thrives on such reactions. His aim is to disturb and unnerve, to stir the viewer out of his seat and out of his comfort zone. This is done not simply for the ‘shock value’ in itself, as there is no legitimate artistic worth in managing to provoke or enrage the audience; instead this is done in order to communicate something through the shocking material. By knocking the viewer out of his ordinary perspective, where everything is comfortably perceived and organized according to a familiar worldview, Lars von Trier can assault him with a new perspective, a new challenge that might threaten his old way of viewing reality.

Lars von Trier, of course, thrives on such reactions. His aim is to disturb and unnerve, to stir the viewer out of his seat and out of his comfort zone. This is done not simply for the ‘shock value’ in itself, as there is no legitimate artistic worth in managing to provoke or enrage the audience; instead this is done in order to communicate something through the shocking material. By knocking the viewer out of his ordinary perspective, where everything is comfortably perceived and organized according to a familiar worldview, Lars von Trier can assault him with a new perspective, a new challenge that might threaten his old way of viewing reality.

This is truer of The Idiots than any other LvT film, and that includes the psychological horror of Antichrist and the raw sexual trauma of Nymphomaniac. This is due to the highly abrasive nature of the film’s narrative, which tells the story of a group of people who act like they are mentally retarded as a form of rebellion against what they understand to be a constrictive, conformist, and sterilizing society. Their antics, which they call ‘spazzing,’ include going into town to sell Christmas ornaments that they have made, going to the pool to create mischief with the other swimmers, and eating at restaurants only to spazz and leave without paying.

It is during the last antic that the group comes into contact with Karen, a seemingly ordinary person who becomes drawn and intimately attached to the spazz community over the next two weeks. Karen initially provides the neutral perspective of the group, the backdrop of normality to their witting insanity; she is very curious, though, and constantly questions the reasoning behind their activities, allowing the viewer to get a keener understanding of what they do. She firstly represents the ignorant audience who nevertheless desire to know more, but later, as we will see, she represents the fulfilment of the ‘spazz way of life.’

The group is led by a man named Stoffer, who is clearly the one who takes their mission the most seriously, ostensibly giving it an ideological basis and a higher cause than merely acting like idiots. Karen asks Stoffer why they do what they do, and Stoffer replies, ‘In the stone age all the idiots died. It doesn’t have to be like that nowadays. Being an idiot is a luxury, but it is also a step forward. Idiots are the people of the future. If one can find the one idiot that happens to be one’s own idiot . . .’ Stoffer finds in idiocy an outlet for what bourgeois society has repressed or camouflaged, namely a kind of personal creativity that does not accord with social normalcy. It is a new freedom, one which was obviously unavailable in a more brutal time, but which is presently imperative in an era that prizes comfort, material luxury, and ostracizes everything that is not conducive to ‘making one’s way in the world,’ i.e., becoming rich and popular. Stoffer asks meaningfully, ‘What’s the idea of a society that gets richer and richer when it doesn’t make anyone happier?’ Stoffer’s idea is instead to make one happier regardless of riches.

The means of achieving this are chiefly to ‘find the one idiot that happens to be one’s own idiot,’ a demonstrably individualistic and interiorized path that cannot help but hearken back to the Dionysian nature of the Breaking the Waves heroine, Bess. The idea is to determine the other side of oneself, the side that society has dispelled and rejected from its embrace. It is in this sense that we are reminded of C. G. Jung’s conception of the ‘shadow,’ or the secret personality that is imbued with our darker elements, with everything that has been evicted from and cannot fit into conscious life. Stoffer’s aim is essentially to reconcile modern man with his shadow self in a radical way; he aims to reintegrate man with his inner darkness to create something that is once again whole, independent of outer definitions and social parameters. When one character wakes him up, telling him that another spazzer is breaking things on the property, Stoffer responds, ‘Sheds are bourgeois crap. Smashing windows is obviously part of Axel’s inner idiot.’ The smashing of windows is an act that is socially reprehensible, but, since it allegedly exists as part of Axel’s ‘inner idiot,’ his ‘shadow self,’ it is perfectly acceptable in spazzer society.

This opposition between consciousness and the shadow is present not only in the individual sense, where the characters play out this drama in themselves, but in the collective sense as well. What this means is that the bourgeoisie, which is invariably treated as a great evil and as something to be rebelled against, represents the conscious side, and the spazzer society represents the shadow side; they are the ‘reservoir of darkness’ that has spilled out from respectable society, and has come to life after society has failed to suppress it. They even use society’s own tools against it, inverting the logic of social machinations to serve immoral ends. In one scene, for example, Stoffer has one of the spazzers pretend to have tripped over a loose cobblestone near a well-to-do homeowner’s property, then pesters the man to pay them off in order to avoid a lawsuit. When the wealthy man asks whether the spazzer didn’t simply trip on his own rather than a loose stone, Stoffer answers, ‘Are you saying they drag their feet? that they are clumsy?,’ which forces the man to retreat, unwilling to be responsible for anything that might be considered ‘politically incorrect.’ Stoffer considers this to be a victory over the ‘fascist’ system that he hates, contemptuously gazing into its soul and mocking it.

There are other scenes, too, that reveal other ‘victorious’ moments against other, more typical members of society. The house where they are staying, for example, is that of Stoffer’s uncle, who has entrusted Stoffer to sell it. When he visits the house, he remarks that he take better care of it, saying that, ‘These floors have been waxed every day for fifty years,’ which of course exemplifies the hated bourgeois attitude. Later on, coming into possession of caviar, Stoffer shows his group how to ‘eat it the way they eat caviar in Soelleroed [their town],’ stuffing it into his mouth as though he were a child eating chocolate. Allured by the antics of her new friends, Karen also learns to spazz, and though she meaningfully does not participate to the same extent as the others, she says that, ‘We’re so happy here. I’ve no right to be so happy.’

II (Major Spoilers)

The ‘paradise’ of Soelleroed is largely an illusion, however, as the final third of the film reveals. It is in these segments that the real darkness of the shadow comes out, which altogether reflects the failure of Stoffer’s mission to reconcile it with their conscious lives. This is as manifest in Stoffer himself as in any of the others. In one scene, for instance, a city official arrives at the house to offer them a government grant and a new location where they might stay, somewhere that is further away from normal society and which therefore makes it harder for them to intrude upon normal people. Stoffer of course reacts violently to this, ripping off his clothes and chasing the official all the way back to town naked, screaming ‘Fascist! fascist!’ the whole time. The others drag him back to the house, but they have to physically restrain him, strapping him to a bed overnight as he has reverted to a purely irrational state, succumbing to an episode that was formerly merely an act.

Another character, too, after the girl he fell in love with is stolen away from the house by her father, chases after him, running into his car, gesturing wildly and speaking nonsense. Affected so deeply by his feeling for her, he is no longer able to bridge the gap between his conscious self and the primitive he used to play at but has now become reality. This is not a successful integration between consciousness and the shadow; this is the conquest of the former by the latter, resulting in the personality regressing to something animalistic and instinctual. Stoffer’s experimentation in human happiness has failed, because there is no longer anything human in his subjects.

There are more obvious instances of this darkness, too. After the night which Stoffer spends in straps, they have a party, and at the end of the party he requests a gangbang. Most of his fellows willingly participate, but some do not; this leads Stoffer and another to chase one of the unwilling women down, essentially raping her in a violently disturbing scene of spazz sex. It is significant that Karen retreats from this scene altogether, abstaining from the evil that has infiltrated the rest of the ‘shadow group.’ It is even more significant that she is not raped, for she has maintained her own sense of self in contradistinction to the others; her personality is still intact while those of the others have been overwhelmed and utterly ransacked of their humanity.

Nearing the end of the film, Stoffer comes to doubt the sincerity of his fellow idiots, suspecting that this is all just some sort of game to them. He orders them to play ‘spin the bottle,’ with whomever the bottle points at having to demonstrate his commitment to the cause by spazzing in ‘real life’ places such as at work or at home with the wife and kids. The first fails completely, refusing to spazz in front of his family; he elects a normal life instead of the idiot life and the mistress he kept among them. The second opts to spazz in front of an art class he will be teaching, but he fails as well, causing Stoffer to storm out of the class, saying, ‘You love this middle class crap. These old dames use more make-up than the national theatre.’ The teacher, Henrik, says, ‘I had no pride in my inner idiot.’ The shadow self was just an illusion for them, something to play at in an insubstantial expression of inward identity.

Stoffer himself comes no closer to the reconciliation between the shadow and the ego. Instead of being the romantic and anarchic hero revolting against the oppressive bourgeois system that he likes to consider himself, he is infact a representation of it in its inverted sense; he is the ‘other side of the same coin,’ reflecting the absence of a genuine morality that extends to both the ‘middle class’ and the bohemian individualism. His ethos is fundamentally the same as that of his bourgeois uncle: ‘In reality, the acceptance of the shadow-side of human nature verges on the impossible. Consider for a moment what it means to grant the right of existence to what is unreasonable, senseless, and evil! Yet it is just this that the modern man insists upon. He wants to live with every side of himself — to know what he is. That is why he casts history aside. He wants to break with tradition so that he can experiment with his life and determine what value and meaning things have in themselves, apart from traditional presuppositions’ (C. G. Jung, ‘Psychotherapists or the Clergy’).

Stoffer is the epitome of the ‘modern man’ in that he wants to throw off all social inhibitions, not merely those of the 20th Century middle class, but the entire framework of human society. His revolt is the same as the student and hippy revolts of the sixties, revolts which were ultimately codified into the same bourgeois vassals that they originally reacted against. This is what makes Stoffer the superficial counterpart to the bourgeoisie; this is what makes him its useful idiot.

Karen is the only one who volunteers to spazz in her own life. Taking along her friend Suzanne for company, Karen returns to her home, somewhere she has not been for two weeks. We soon learn that her son had died, and that her son’s funeral was the day after she joined the group. Her husband comes home, and they sit down to eat – and Karen drools and dribbles at her food, which causes her family to stare, and her husband to hit her. Suzanne takes her hand, and they leave together, smiling naively, innocently.

Earlier in the film, Karen says to Stoffer, ‘I just want to be able to understand why I’m here,’ to which he replies, ‘Perhaps because there is a little idiot in there that wants to come out and have some company.’ While that is true in a certain, limited sense, it is truer to say that Karen’s ‘little idiot’ needed to come out to save her conscious self. Besieged by an impossible grief and a mother’s mourning, Karen’s ego longed for an escape route from the world’s immense difficulty. That she alone found it amongst all the idiots testifies both to the extent of her trauma and her extraordinary capability of dealing with it; she alone could make real sense of what the idiots were only playing at. Their reactions (aside from Stoffer, who was overcome by his own shadow) were conditioned by their belonging to the bourgeois order, something from which they recoiled in theory, but which they nevertheless could not do without; Karen’s reaction, on the other hand, was conditioned by a more profound disorder, which demanded an extreme process in order to be able to cope with it. Her struggle was far more real than that of the others, which is why she was the only one to find the solution to it.

The Idiots reveals both the positive and the negative scenarios that are the consequence of a Dionysiac revolt against the Apollonian dream-world. In order to ‘revolt successfully,’ to truly indulge in Dionysian fruit, the individual’s actions must be founded on something universally real that transcends particular circumstances; he must determine himself based on who he really is rather than merely a perception or a projection of who he is. This is where most of the idiots failed: ‘The shadow is a moral problem that challenges the whole ego-personality, for no one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort. To become conscious of it involves recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real. This act is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge’ (C. G. Jung, Aion). The idiots never really became conscious of their shadow; they acted it out either as a meaningless game that allowed them an illusion of rebellion against their bourgeois lives, or, in the case of Stoffer, as a license to perform whatever irrational and pernicious acts that occurred to him, as long as they did not agree with the prevailing social order. They never addressed the shadow as a ‘moral problem,’ as something that directly influences the person; they addressed it as a ‘social problem,’ and thus remained chained to the illusions of Apollo’s dream-world.

Karen alone represents Dionysus as the purveyor of dynamic, uninhibited truth. She refused the moral violations of the other idiots, she refused their pretensions of abandoning society, and she refused their needless and unlawful interdictions with the rest of the town; in a word, Karen rejected rejection, and she did so because her rebellion was founded on an affirmation of self rather than on its negation. Unlike Stoffer, who loses control when he is confronted with that which he hates and fears most (the bourgeois city official), Karen maintains perfect control as she releases her inner idiot in front of her family, again exemplifying a personal command that eluded the others.

Speaking of her return home, where she demonstrates her restored personal strength, she says to the idiots, ‘We’ll see if I can show you if it has all been worthwhile.’ This follows a farewell in which Karen expresses an open, authentic love for many of the idiots, and repeats her avowal of happiness to have been amongst them. Karen’s family, cold, unfeeling, and uncomprehending of what it must be for a mother to lose her son, failed to ease her grief; it was only in her introspection, the confrontation with her ‘inner idiot’ as a lifeboat that carries her from the drowning ego, that actually saves the ego. By acknowledging her despair in this radical context, she could dilute and eventually sublimate it into something far more positive, to the extent that, all things considered, she does not even know why or how she can be so happy. In this sense, the freedom of Dionysus is attained not as a rejection of Apollo, but as a victorious affirmation of the reconciliation between the unconscious and the conscious; while the rest of the idiots founded their shadow-search on a rejection of Apollo, Karen had to be rejected by him instead. This is what led to her final freedom; this is what made it all worthwhile.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2015/08/lars-von-triers-the-idiots/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: https://secure.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/TheIdiots.jpg

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lars von trier, cinéma, film, danemark |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 28 août 2015

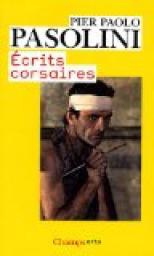

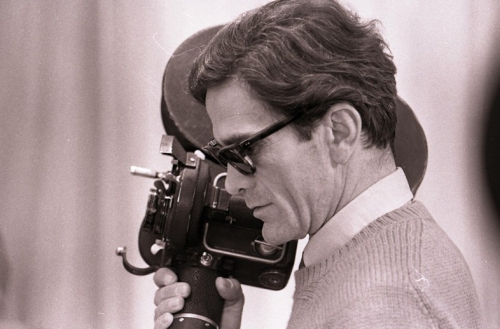

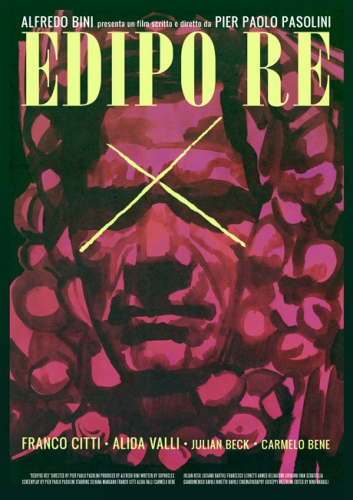

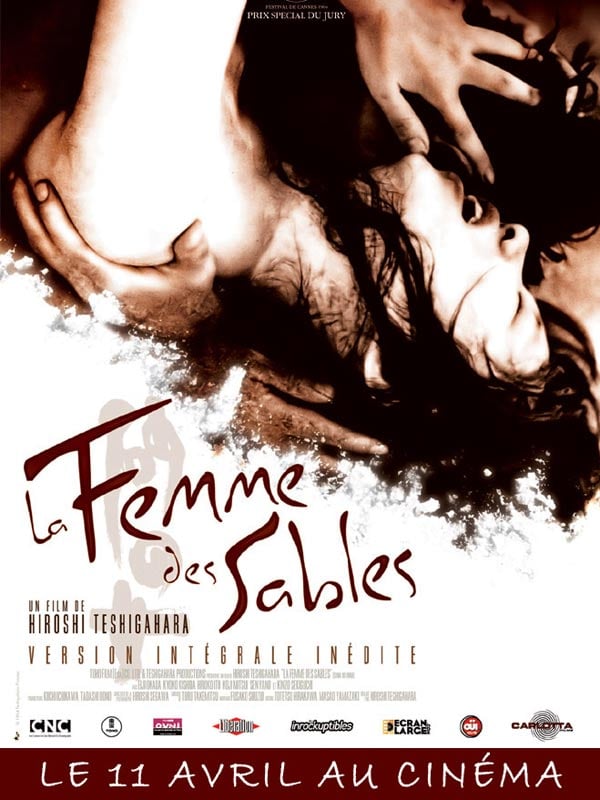

Le théorème irrésolu de Pier Paolo Pasolini

Le théorème irrésolu de Pier Paolo Pasolini

par Patrice-Hans Perrier

Ex: http://www.dedefensa.org

La figure iconoclaste du cinéaste italien nous interpelle en cette époque de soumission et de trahisons multiples. Nous avons décortiqué les derniers écrits polémiques de Pasolini publiés sous le titre d’« Écrits corsaires » (*). Déjà, au beau milieu des années 1960, ce dernier avait compris que la Société de consommation était un fascisme en état de gestation. Nous nous débattons, quarante années après son assassinat, dans les méandres d’un véritable Léviathan qui achève de consommer ce que nous avions de plus précieux : notre innocence.

Fasciné, très tôt, par la culture populaire des bidonvilles et des banlieues ouvrières de l’après-guerre, le cinéaste Pier Paolo Pasolini prendra la relève du néoréalisme italien en travaillant la pellicule sur un mode à mi-chemin entre le documentaire et la fable surréaliste. Reprenant les canons esthétiques du néoréalisme, Pasolini termine en 1962 un film poignant intitulé Mamma Roma. Mettant en scène une Anna Magnani qui deviendra son égérie, et une source d’inspiration pour d’autres cinéastes prometteurs, le metteur en scène brosse un tableau saisissant des faubourgs de la Ville éternelle. Jeune quarantenaire, Pasolini aborde, finalement, le cinéma à la manière d’un écrivain et d’un sociologue qui a vécu « pour de vrai » auprès des classes défavorisées de l’Italie de l’après-guerre.

Praticien d’un « cinéma-vérité » proche de la tradition documentaire, Pasolini capte l’ambiance extraordinaire des bas-fonds romains en faisant déambuler son personnage principale – une prostituée qui tente de fuir son inhumaine condition – dans les alentours du Parc des aqueducs et de l’aqueduc de l’Aqua Claudia. Cet opus cinématographique inaugure une pratique qui deviendra sa véritable signature : filmer le plus possible les décors naturels de la cité et mettre en scène des figurants qui ne sont pas des professionnels du septième art. Tourné en noir et blanc, Mamma Roma ressemble à une véritable plongée au plus profond de l’existence quotidienne de ce « petit peuple » qui n’est déjà plus qu’un lointain souvenir.

Le témoin oculaire d’une époque de transition

Le témoin oculaire d’une époque de transition

« … la société de consommation de masse, en recouvrant artificiellement le tissu vivant de l’Italie par un ensemble insipide et uniforme de valeurs pragmatiques propres à l’idéologies du « bien-être », a littéralement étouffé l’identité du pays, a broyé dans une même machine imbécile de normalisation tous les particularismes culturels, les « petites patries » et les mondes dialectaux de la campagne italienne, jusqu’à modifier moralement et même physiquement le paysan pauvre … »

Pier Paolo Pasolini, in « Écrits corsaires – Scritti Corsari »

Artiste manifestement en porte-à-faux face aux élites de son époque, Pasolini tente de témoigner du délitement des anciennes cultures populaires au profit de l’impérialisme de cette société de la consommation qui ne tolère plus aucune forme de dissidence. Militant communiste de la première heure, pourfendant les nostalgiques de l’ancien régime fasciste, le bouillant polémiste refuse de basculer dans le « camp du bien » représenté par un gauchisme à la mode qui fera, de plus en plus, le jeu du grand capitalisme international. Réalisant que la démocratie-chrétienne d’après-guerre sert toujours les mêmes intérêts qui contrôlaient les fascistes de l’ère mussolinienne, Pasolini tente de cerner avec une précision sans faille la transition qui s’est amorcée durant les « trente glorieuses » (1945 – 1975).

Le portrait de cette période de transition est loin d’être reluisant. Pendant que la masse des anciens prolétaires, comparés à des « néo-bourgeois », se laisse embrigader par la société de consommation, un véritable pouvoir occulte tisse sa toile et provoque des crises artificielles qui auront pour effet d’accélérer la transformation en profondeur de la société italienne. Les élites aux manettes utiliseront une « stratégie de la tension », savamment dosée, afin de mettre en scène ses troupes de choc. Cette montée en crescendo de la tension atteindra son point culminant avec l’attentat terroriste de la gare de Bologne en 1980. Ce qui constitue un des attentats terroristes les plus meurtriers du XXe siècle aura des conséquences considérables sur les futures orientations de la vie politique en Italie.

Pier Paolo Pasolini sera, envers et contre tous ses détracteurs, l’observateur lucide et prophétique d’une époque charnière qui peut se comparer à celle qui fut le théâtre de la dissolution du gaullisme en France. Pasolini décrypte, avec plusieurs coups d’avance, la mutation de l’ancien monde paysan et patriarcal vers une société de consommation qui permet d’agréger les citoyens au sein d’une « internationale » néolibérale qui ne dit pas son nom. Parlant de la démocratie-chrétienne, il souligne que « bien que ce régime ait fondé son pouvoir sur des principes essentiellement opposés à ceux du fascisme classique (en renonçant, ces dernières années, à la contribution d’une Église réduite à n’être plus qu’un fantôme d’elle-même), on peut encore très justement le qualifier de fasciste. Pourquoi ? Avant tout parce que l’organisation de l’État, à savoir le sous-État, est demeurée pratiquement la même; et plus, à travers, par exemple, l’intervention de la Mafia. La gravité des formes de sous-gouvernement a beaucoup augmenté ». Faisant allusion aux lobbys de l’ombre qui poussent leurs pions, Pasolini se rapprochait des conceptions actuelles qui ont trait à l’« État profond » et autres réseaux de gouvernance « occulte » ayant fini par court-circuiter l’appareil d’état.

Quand le discours des politiques sonne faux

Profondément influencé par la pensée critique d’Antonio Gramsci – un théoricien marxiste qui mettra de l’avant le primat de l’ « hégémonie culturelle » comme moyen central de maintien et de consolidation de l’appareil d’état dans un monde capitaliste –, Pasolini réalise que les élites italiennes aux commandes utilisent un discours politique caduc. Manipulant des concepts qui avaient leur raison d’être avant la Deuxième guerre mondiale, la classe politique italienne se comporte en véritable somnambule, incapable de comprendre ce qui se trame derrière la scène. La dislocation des anciens lieux de reproduction des habitus socioculturels et religieux semble avec été provoquée par la mutation d’un capitalisme qui ne se contente plus d’exploiter les masses.

Il s’agit de transformer les citoyens en consommateurs dociles, sortes de citadins décervelés qui ont perdu la mémoire. Chassés de leurs anciens faubourgs, relocalisés dans des banlieues uniformes et grises, les nouveaux citoyens de la société de consommation ne possèdent plus de culture en propre. Il s’insurge contre le fait qu’«une telle absence de culture devient [devienne], elle aussi, une offense à la dignité humaine quand elle se manifeste explicitement comme mépris de la culture moderne et, par ailleurs, n’exprime que la violence et l’ignorance d’un monde répressif comme totalité».

Le délitement de l’ancienne société

Pasolini s’intéresse à cette perte des repères identitaires qui finit par gruger les fondations d’une société déshumanisée par le passage en force du nouveau capitalisme apatride des années d’après-guerre. Il n’hésite pas à parler de « révolution anthropologique » et va jusqu’à affirmer « que l’Italie paysanne et paléo-industrielle s’est défaite, effondrée, qu’elle n’existe plus, et qu’à sa place il y a un vide qui attend sans doute d’être rempli par un embourgeoisement général, du type que j’ai évoqué … (modernisant, faussement tolérant, américanisant, etc.) ». À la manière des précurseurs du cinéma-vérité et documentaire québécois, Pier Paolo Pasolini filme, enregistre et consigne les derniers sédiments d’une société archaïque en voie de dissolution. Pris à parti, dans un premier temps, par les ténors de la droite, ce créateur iconoclaste finira par s’attirer les foudres de l’intelligentsia au grand complet.

Un humaniste dégouté par la violence ordinaire

Un humaniste dégouté par la violence ordinaire

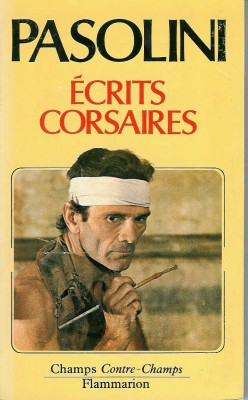

Il est impératif de lire (ou de relire) ses « Écrits corsaires » qui rassemblent un florilège de ses meilleurs pamphlets et autres écrits polémiques. Démontrant une intelligence critique sans pareil, Pasolini demeure un véritable hérétique qui n’a jamais baissé le ton fasse aux trop nombreuses impostures d’une intelligentsia, de droite comme de gauche, corrompues jusqu’à la moelle. Militant communiste, non-croyant et anticonformiste, il se désole, néanmoins, de la disparition de cette foi catholique qui représentait un des « relais » de l’authentique culture populaire. S’il s’est élevé contre le pouvoir démagogique des autorités ecclésiastiques et politiques de l’ancien régime, il admet que celui de la nouvelle classe technocratique est encore plus effrayant.

Il tente d’esquisser le profil de cette hyper-classe mondiale qui s’est installée à demeure depuis : « Le portrait-robot de ce visage encore vide du nouveau Pouvoir lui attribue des traits « modernes » dus à une tolérance et à une idéologie hédoniste qui se suffit pleinement à elle-même, mais également des traits féroces et essentiellement répressifs : car sa tolérance est fausse et, en réalité, jamais aucun homme n’a dû être aussi normal et conformiste que le consommateur; quand à l’hédonisme, il cache évidemment une décision de tout pré-ordonner avec une cruauté que l’histoire n’a jamais connue. Ce nouveau Pouvoir, que personne ne représente encore et qui est le résultat d’une « mutation » de la classe dominante, est donc en réalité – si nous voulons conserver la vieille terminologie – une forme « totale » de fascisme ».

Plus que jamais d’actualité, le vibrant témoignage de Pier Paolo Pasolini interpelle ceux et celles qui ont à cœur de refonder les agoras de nos cités prises en otage. Ses écrits polémiques, ses films et sa truculente poésie sont encore accessibles. Mais, pour combien de temps encore ?

Patrice-Hans Perrier

Notes

(*) Écrits corsaires – Scritti corsari, une compilation de lettres brulantes mise en forme en 1975. Écrit par Pier Paolo Pasolini, 281 pages – ISBN : 978-2-0812-2662-3. Édité par Flammarion, 1976.

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cinéma, italie, philosophie, pier paolo pasolini, pasolini |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 15 juin 2015

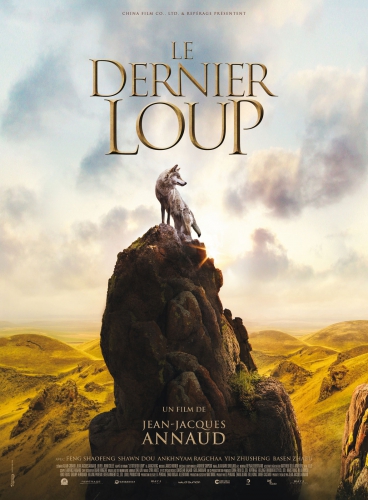

Sept films à voir ou à revoir sur les Vikings

Sept films à voir ou à revoir sur les Vikings

Ex: http://www.cerclenonconforme.hautetfort.com

Du 8ème au 11ème siècle, de terribles raids ravagent une majeure partie de l'Europe du Nord. Débarquant de leurs impressionnants drakkars et ne connaissant pas de Dieu unique, les Vikings ont très abondamment imprégné l'imaginaire collectif médiéval européen. L'Histoire ne retiendra qu'une imagerie guerrière de ces conquérants venus de l'Hyperborée. Or, s'il apparaît indéniable que les Scandinaves ne dédaignaient pas faire périr par le glaive et si leur perception des échanges commerciaux se confondait parfois avec la rapine, les Vikings apparurent également comme de formidables commerçants dont les colonies surent se dissoudre parmi les communautés autochtones, au point de disparaître progressivement en tant que peuple distinct et abandonner leurs croyances païennes. Le cinéma consacra quelques réalisations à ces redoutables guerriers-commerçants. Pour le meilleur comme pour le pire car rares sont les films parvenus à maintenir une certaine distance entre l'Histoire et la légende.

ALFRED LE GRAND VAINQUEUR DES VIKINGS

Titre original : Alfred the Great

Film anglais de Clive Donner (1968)

871 dans le Wessex au Sud de l'Angleterre. Le jeune prince Alfred, frère du roi du Wessex, se destine à une vie sacerdotale. Ce parcours est contrarié par son amour pour Edwige, fille du roi de Murcie. Il l'épouse. Une chute mortelle à cheval du Roi endeuille les noces le jour même, favorisant ainsi l'accès d'Alfred au trône. La tâche n'est guère aisée en ces temps où toute l'Europe du Nord est harcelée par les raids scandinaves. Le chef des Vikings, Guthrun, exige un trésor et prend en otage la jeune reine dont il fait sa maîtresse. Abandonné par la noblesse, Alfred est contraint de se cacher dans les marais. Seuls des hors-la-loi et des gueux acceptent de prendre les armes pour faire face à l'envahisseur danois...

Si Donner prend quelques libertés avec l'Histoire d'Alfred, premier unificateur des royaumes anglo-saxons, il livre néanmoins ici une œuvre sérieuse retraçant fidèlement les villes et campagnes médiévales britanniques. Les scènes de batailles constituent un autre point fort du film et sont particulièrement réussies. La dernière bataille est tout simplement épique grâce à certaines prises de vue réalisées depuis un avion. Une réalisation à voir absolument et ne sombrant jamais dans les facilités dans sa représentation des Vikings.

BEOWULF, LA LEGENDE VIKING

Titre original : Beowulf & Grendel

Film américain de Sturla Gunnarsson (2009)

Le Danemark au 6ème siècle. Le roi Hrothgar fait appel à Beowulf, un guerrier réputé invincible, et le charge de l'élimination d'un troll nommé Grendel, accusé de semer la terreur dans le royaume. Beowulf part immédiatement sur les traces du troll et réalise rapidement que Grendel n'est pas cet être sanguinaire et détenant des pouvoirs surnaturels tel que décrit à la cour. Bien au contraire, Beowulf est rapidement convaincu que le Roi cache bien des choses et pourrait être à l'origine de la monstruosité et de la soif de vengeance du troll. Beowulf ne sait s'il doit tuer le troll, d'autant plus qu'il fait la rencontre de Selma, une mystérieuse et sensuelle sorcière...

Hollywood qui se préoccupe d'un poème épique majeur des littératures anglo-saxonne et germano-scandinave, ça donne ça... Cependant moins catastrophique que les deux premières adaptations de la légende de Beowulf qui invitaient au suicide, la réalisation de Gunnarsson offre de belles images tournées en Islande bien qu'elles dénaturent totalement la localisation danoise de l'histoire originelle. Certaines séquences sont vraiment réussies et ne peuvent que faire regretter la faiblesse de l'ensemble malgré le bénéfice d'un budget ambitieux.

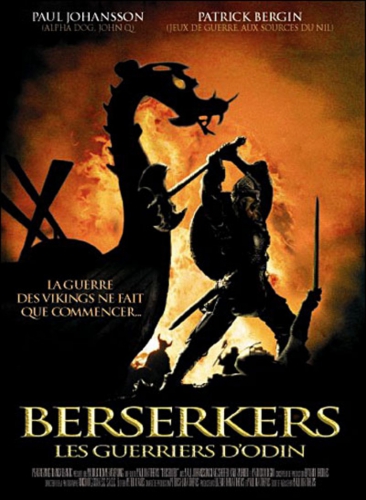

BERSERKERS, LES GUERRIERS D'ODIN

Titre original : Berserker

Film sud-africain de Paul Matthews (2004)

Thorsson, seigneur viking, établit un pacte avec le dieu Odin et ses Berserkers, guerriers intrépides, pour défendre ses terres et prendre possession de celles de ses ennemis. Thorsson triomphe et trahit aussitôt sa promesse d'offrir le fruit de leurs conquêtes aux Berserkers. Au contraire, il entreprend leur exécution. Odin mène une terrible vengeance sur Thorsson et sa descendance. Barek, son fils héritier, et sa promise Brunhilda la Valkyrie seront traqués sans relâche par les Berserkers. La malédiction éternelle ne peut se voir conjurée que par la hache du guerrier viking le plus impitoyable...

On peut craindre le pire de ce film et c'est bien le pire qui ressort... Le premier tiers du film ne manque pourtant pas d'attrait et masque relativement bien le criant manque de moyens. Et patatras ! Vous pensiez ne jamais pouvoir visionner un film sur les Vikings dont l'histoire se déroule jusqu'au 21ème siècle ? Vous avez bien lu ! L'intrigue du film se transporte jusqu'à nos jours. Grâce soit rendue à Paul Matthews qui a osé le faire et est même parvenu à convaincre des financeurs de le suivre dans son projet abracadabrant. Il n'y a désormais plus qu'à espérer qu'Odin transpose sa malédiction sur le cinéaste.

VALHALLA RISING, LE GUERRIER SILENCIEUX

Titre original : Valhalla Rising

Film anglo-danois de Nicolas Winding Refn (2009)

Autour de l'an mil en Ecosse, l'exacerbation des tensions entre chrétiens et païens est à son comble. Des chefs de clans vikings et écossais font se livrer leurs prisonniers esclaves à de terribles combats à mains nues. Un guerrier muet et borgne, surnommé One-Eye, et demeurant invaincu, s'affranchit en assassinant son maître Barde et s'échappe avec un enfant. Les fuyards rejoignent bientôt une troupe de Vikings convertis au Christianisme cherchant à se croiser en direction de la Terre Sainte. Le brouillard fait dériver l'embarcation dans une mauvaise direction et nos héros débarquent sur une terre inconnue. Les tensions entre chrétiens et païens affranchis augmentent tandis qu'ils sont la cible de redoutables indigènes...

Curieux phénomène que cette pléthore de films sur les Vikings et la mythologie scandinave. Valhalla Rising n'est pas un chef-d'œuvre et les puristes de la Weltanschuung Nordique s'arracheront encore quelques cheveux de plus. Mais diversifier les scénarii ne permet-il pas de faire vivre notre plus longue mémoire et la sortir du chloroforme d'un certain élitisme universitaire ? Et tant pis, si on frôle parfois l'iconoclasme. Nonobstant, la photographie est magnifique et le scénario parvient à tenir en haleine.

LES VIKINGS

Titre original : The Vikings

Film américain de Richard Fleischer (1957)

Vers 900, l'Angleterre est harcelée par les raids vikings conduits par le chef Ragnar. Edwin, roi de Notrhumbrie, est tué et son épouse violée. Son successeur, Aella, ordonne l'arrestation de son cousin Egbert, suspecté de complot, qui parvient finalement à rejoindre les envahisseurs scandinaves. Les deux fils de Ragnar, Einar et Erik, fruit du viol de la reine, se vouent une haine farouche. Lors d'un nouveau raid, Einar capture Morgana, la fiancée d'Aella, qui parviendra à s'échapper grâce à la complicité d'Erik. Erik est également accusé d'avoir donné une épée à Ragnar qui, capturé, a été offert à l'appétit des loups. Si les deux frères parviennent à se réconcilier en vue de l'assaut du château d'Aella, la bonne entente ne semble pas pouvoir durer...

La réalisation de Fleischer est LE bijou sur les peuples venus de l'Hyperborée. Un film d'une extraordinaire beauté dans ses paysages et dans la reconstitution des drakkars. Les nombreuses scènes de combat sont remarquables et d'une violence inouïe. Les acteurs, Kirk Douglas en tête, sont tous plus convaincants les uns que les autres. On pardonnera aisément un côté images d'Epinal et la grosse bévue de l'utilisation du Fort-la-Latte totalement anachronique. Un pur chef-d'œuvre par Thor et Odin !

VIKINGS

Série canado-irlandaise de Michael Hirst (2013-2016)

La Scandinavie à la fin du 8ème siècle. Ragnar Lodbrok est un jeune guerrier viking aussi intrépide qu'assoiffé de gloire et de conquêtes. Simple fermier, il est l'homme lige de Haraldson. Ragnar se lasse de mener inlassablement les mêmes raids sur les terres de la Baltique et se met en tête d'étendre les pillages en direction de l'Ouest. Haraldson lui interdit de se lancer dans une telle entreprise. Mais le tenace Ragnar est bien décidé à mener ses plans comme il l'entend. Se fiant aux signes et à la volonté des dieux, Ragnar fait clandestinement construire une nouvelle génération de vaisseaux aussi légers que rapides. La désobéissance de Ragnar va modifier à jamais l'histoire des peuples hyperboréens et d'une majeure partie de l'Europe...

Splendide ! Il n'y a pas d'autres mots ! Un scénario solide et prenant sublimé par un important travail de documentation. C'est à une véritable plongée au cœur des sociétés vikings à laquelle le spectateur est invité. Les profils psychologiques de certains personnages manquent néanmoins parfois d'un peu de profondeur. On a hâte de découvrir les prochaines saisons avec l'espoir que Vikings ne sombre pas dans le politiquement correct comme tant d'autres séries ou films qui s'émoussent au fil des saisons et des épisodes. Game of Thrones et Le Hobbit sont malheureusement là pour nous le rappeler.

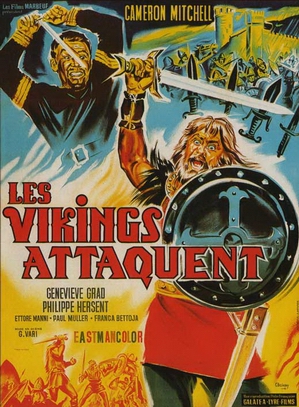

LES VIKINGS ATTAQUENT

Titre original : I Normanni

Film franco-italien de Giuseppe Vari (1962)

Au 9ème siècle, nombre de seigneurs anglais s'affrontent pour établir et consolider leur pouvoir. Wilfred, neveu du roi Dagobert est un jeune intriguant. Faisant la cour à la reine Patricia, il parvient à faire retenir prisonnier le Roi et porter les soupçons de félonie sur des contingents Normands, commandés par Olaf, établis sur ses terres et souhaitant y demeurer pacifiquement. Olivier d'Anglon, un jeune comte, s'éprend de Svetlana qu'il pense être la fille du chef viking mais qui se révèle en réalité être la fille issue des premières noces de Dagobert. A l'intrigue amoureuse, se joint la cupidité de Wilfred à qui Dagobert refuse de faire connaître la cachette de son trésor. Le sang ne peut que couler...

Au 9ème siècle, nombre de seigneurs anglais s'affrontent pour établir et consolider leur pouvoir. Wilfred, neveu du roi Dagobert est un jeune intriguant. Faisant la cour à la reine Patricia, il parvient à faire retenir prisonnier le Roi et porter les soupçons de félonie sur des contingents Normands, commandés par Olaf, établis sur ses terres et souhaitant y demeurer pacifiquement. Olivier d'Anglon, un jeune comte, s'éprend de Svetlana qu'il pense être la fille du chef viking mais qui se révèle en réalité être la fille issue des premières noces de Dagobert. A l'intrigue amoureuse, se joint la cupidité de Wilfred à qui Dagobert refuse de faire connaître la cachette de son trésor. Le sang ne peut que couler...

Le succès de la réalisation de Fleischer a certainement fait fleurir des idées dans la tête d'autres cinéastes. Ainsi de Vari dont le film demeure très largement en dessous de celle du réalisateur américain. Mais on a connu pire depuis sur les Vikings à l'écran alors ne boudons pas celui-ci qui se laisse regarder. Particularité intéressante, les Scandinaves ne sont pas présentés de prime abord comme des barbares sanguinaires avides de rapines et de combats mais bien comme des envahisseurs commerçants et soucieux de quiétude.

Virgile /

Note du C.N.C.: Toute reproduction éventuelle de ce contenu doit mentionner la source

C.N.C.

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cinéma, films, vikings, 7ème art |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 16 mai 2015

Sisters of Salome: Femmes Fatales, Left & Right

Sisters of Salome:

Femmes Fatales, Left & Right

By Fenek Solère

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Left/Right dichotomies in the representation of female militants in the movies The Baader Meinhof Complex (2008) and A Student named Alexander (2011).

‘Although typically villainous, or at least morally ambiguous, and always associated with a sense of mystification and unease, femme fatales have also appeared as heroines in some stories . . .’

— Mary Ann Doane

From the Levantine Lilith to the Celtic Morgan Le Fay; and from Theda Bara’s vamp in Hollywood’s A Fool There Was to Eva Green in Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, the notion of the fille d’Eve tantalizes us. In sociological terms the notion of diabolic women is potent with misogyny, witchcraft and the negative aspects of anima, how woman appears to man, from the Jungian viewpoint. To take the cinematic angle, licentious dames mean box office receipts, plain and simple. Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman (1957), starring starlet Brigitte Bardot and Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Betty Blue (1986) with Beatrice Dalle being just two cases that prove the point.

Stereotypes range from enchantress to succubus, haunting our consciousness in different guises, such as the spectral Cathy from Emily Brontë’s classic Wuthering Heights (1847) or the more malign character of Rebecca in Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 book of the same name. As Charles Baudelaire (1821-67) (1), Once mused, ‘The strange thing about woman — her pre-ordained fate — is that she is simultaneously the sin and the Hell that punishes it’. Indeed, a whole academic industry has grown up deconstructing such iconography with writers like Toni Bentley’s Sisters of Salome (2002); Bram Dijkstra’s Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture (1986); and Elizabeth K. Mix’s Evil by Design: The Creation and Marketing of the Femme Fatale in 19th-Century France (2006) leading the way.

Baudelaire’s own magnum opus Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) epitomizes the dichotomy perfectly. The schizophrenia embodied in his poetic creations, Jean Duval (Black Venus) and Apollonie Sabatier (White Venus), both mirroring and reinforcing some male fantasies about women’s sexuality in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. The dialectics of Serpent Culture and Snake Charmer sensuality, so beautifully carved in Auguste Clesinger’s (picture here above) writhing milk white statue Woman Bitten by a Snake (1847), a representation of Apollonie Sabatier currently on display in the Musée d’Orsay, raises the question, is she squirming in agony or riding a paroxysm of pleasure from the venomous bite?

Moving beyond the arts, literature and film to the political milieu? What evidence do we have for Femme Fatale’s within the Left/Right dichotomy? There is certainly a colorful cast of charismatic characters to choose from: Inessa Armand, Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, Jiang Quing, Bernardine Dohrn, and Angela Davis to name but a few on the left-side. Unity Mitford, Savitri Devi, Alessandra Mussolini, Beate Zschape, Yevgenia Khasis, and Marine Le Pen, as examples from the right side of the aisle.

It is my intention to dismiss empathetic documentaries like Confrontation Paris, 68, The Weather Underground (2002) and hatchet-job investigative journalism like Turning Point’s Inside the Hate Conspiracy (1995) about America’s The Order without further comment. Instead arguing that there are few, if any, historically accurate, unbiased and insightful fictional or factional celluloid representations of female (or for that matter male) political militants in circulation. Instead, what we are served up are predictable stereo-types and clichéd cartoonesque parodies, completely aligned with the liberal left Euro-68 ethos, wherein, a mélange of well-meaning but misguided (and always attractive) socialist idealists try to change society for the better, juxtaposed with psychopathic rightist harridans, or male sexual inadequates, portrayed as vacuous outsiders, decidedly uncool and devoid of social capital.

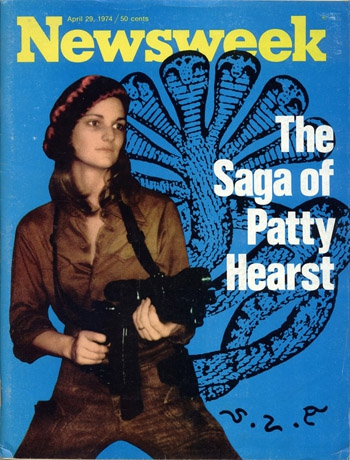

Indicative examples of the genre being, from the left: The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1975), The Underground (1976), Running on Empty (1988), What to Do in Case of Fire (2002), Baader (2002), The Dreamers (2004), Guerilla — The Taking of Patty Hearst (2005), Regular Lovers (2005), Mesrine: Killer Instinct (2008), Che (2008), The Baader Meinhof Complex (2008), The Company You Keep (2012) and Something in the Air (2013). As opposed to the more objectionable characterizations of rightists in productions like The Day of the Jackal (1973), The Odessa File (1974), The Boys from Brazil (1978), Betrayed (1988), Siege at Ruby Ridge (1996), Brotherhood of Murder (1999), and A Student named Alexander (2011).

For the sake of argument I have been deliberately selective and will focus specifically on Uli Edels’s Baader Meinhof Complex and Enzo De Camillis’s fifteen minute short A Student named Alexander. Risking the approbation of cultural commentators by possibly extrapolating too general a hypothesis from too limited a sample, I nevertheless press my case, that the content, reaction and intent of both these films exemplify the paradox of Left/Right caricatures in the entertainment media.

For the sake of argument I have been deliberately selective and will focus specifically on Uli Edels’s Baader Meinhof Complex and Enzo De Camillis’s fifteen minute short A Student named Alexander. Risking the approbation of cultural commentators by possibly extrapolating too general a hypothesis from too limited a sample, I nevertheless press my case, that the content, reaction and intent of both these films exemplify the paradox of Left/Right caricatures in the entertainment media.

Recipient of 6.5 million euros from various film boards and Golden Globe and Oscar nominee in the Best Foreign Film category, The Baader Meinhof Complex, rode the wave of resurgent seventies retro, a movie filled with baby boomer nostalgia for the late sixties and early seventies. Simpler times, when idealism meant Sartre, anti-Vietnam protest, Che Guevara posters, and smoking pot in bedsits listing to the sitar music of Ravi Shankar.

The movies all-star cast includes Martina Gedeck as Ulrike Meinhof, Moritz Bleibtreu as Andreas Baader, Johanna Wokalek as Gudrun Ensslin, and Alexandra Maria Lara as Petra Schelm. All of whom had already or were soon to appear in mainstream feature films like: The Lives of Others, Run Lola Run, The Good Shepherd, Pope Joan, North Face, Control, and Downfall.

The action begins with the 1967 Schah-Besuch mass street protest in Berlin against the Shah of Iran. Mohamed Reza Pahlavi’s supporters are depicted launching an unprovoked attack on the anti-Pahlavi elements, resulting in running battles and the shooting of Benno Ohnesorg in Krumme Strasse 66, by what appears to be a reactionary police officer, Karl-Heinz Kurras, but who was in reality a card-carrying member of the Communist Party acting as an undercover operative for the East German Stasi.

We are then treated to scenes where Maoist students hold packed meetings, intercut with footage of American warplanes strafing and bombing Vietnamese peasants. Rapidly followed by ‘Red’ Rudi Dutschke (3) of 2nd June Movement fame (named after the aforementioned riot) raising his clenched fist, the Messianic leader of the Gramscian ‘Long March through the Institutions’.

Dutschke is elevated to intellectual martyr status when he is mercilessly gunned down in the street by Josef Bachmann, portrayed by actor Tom Schilling, whose cinematic appearance is clearly meant to conjure images of a Hitler Youth or a die-hard Werewolf with a chronic nervous disposition. Which is ironic given that the Baader Meinhof gang and the various later incarnations of the Red Army Faction relied so heavily on a group linked to Heidelberg University, the Sozialistisches Patientiv Kollektiv (Socialist Patient Collective), an organization that sought to convince neurotics and the insane that they were not wrong, it was the system that was wrong, and social revolution was the cure.

‘Shooting is like fucking,’ screams Baader as Bernd Eichinger’s screenplay and Rainer Klausman’s hypnotic lens combine to present a seductive and fast paced cine-orgasm of free love, role model women for Second Wave feminism, cool people smoking cigarettes in coffee shops debating Marxist dialectics, driving around in BMWs, burning department stores, shooting up road signs, Robin Hood bank robbers sunning themselves topless in PLO training camps, liberating captives in a back glow of exploding gelignite and the swashbuckling rat-a-tat of 9mm shells.

Even the capture of Baader, Ensslin, and Meinhof for their egregious crimes are contextually ambiguous. Baader, in a scene more reminiscent of the end of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) than the original television footage of his stand-off with police; Meinhof, kicking and screaming in outrage, rather than the deflated, depressed, and played-out fantasist she was; and Ensslin, by pure chance, when a shop assistant notices a gun in her handbag. Another martyr is then injected into the story as Holger Meins (4) is depicted a la Bobby Sands (5), going on hunger strike and the subsequent trial in Stammheim (6), more Monty Python farce than a serious attempt to enact justice.

One is left in doubt as to where the audience’s sympathy is meant to lie. Especially, with our ever heroic protagonists making fun of the trial judges and gaining increasing support from those in attendance with their witty quips and stunning mind-games. Even The movie’s ending perpetuates the on-going myth that the ‘night of death’ was not triggered by the failure of the Mogadishu hijack (7) to negotiate their release but was in fact a pre-arranged multiple state murder made to look like simultaneous suicide. The movie culminating in a defiant cadre of young stern faced acolytes holding a graveside vigil, determined eyes set on continuing the struggle.

As a consequence, Christina Gerhardt writing in the Film Quarterly describes the movie thus: ‘During its 150 minutes, the film achieves action film momentum, bombs exploding, bullets spraying and glass shattering’. While Christopher Hitchens commenting in Vanity Fair refers to the movie’s ‘Uneasy relationship between sexuality and cruelty . . . an almost neurotic need to oppose authority’. A theme implied by Michael Bubach, son of Siegfried Bubach, the former Chief Federal prosecutor assassinated by the Red Army Faction in 1977, who’s summation of the feature pointed to the fact that the film ‘concentrates almost exclusively on portraying the perpetrators, which carries the danger that the viewer will identify too strongly with the protagonists’.

Examples of how this claim can be justified are so numerous that they would prove tedious to list. However, two personifications, beyond the central characters, stand out in particular, the first involving a chase sequence where Petra Schelm, portrayed by the beautiful Alexandra Maria Lara, is cornered and dies defiantly in a shoot-out with a horde of drone-like cops. The second is the murderous Brigitte Mohnhaupt, depicted by the stunning Naja Uhl, who is shown bedding Peter-Jurgen Boock, played by the teenage heart-throb actor Vinzenz Kiefer, before cold bloodedly slaughtering Siegried Bubach in his own home, organizing the ‘hit’ on Jurgen Ponto, Chairman of the Dresdner Bank of Directors, and the kidnap and murder of Hanns Martin Schleyer. Mohnhaupt, the leader of the second generation of the urban guerillas was also implicated in the 1981 attempt to kill NATO General Frederick Kroesen with a PRG-7 anti-tank missile. In fact, just the sort of unrepentant femme fatale we meet in her polar-opposite, the rightist Francesca Mambro in A Student Named Alexander, but who is treated in the diametrically opposite way.

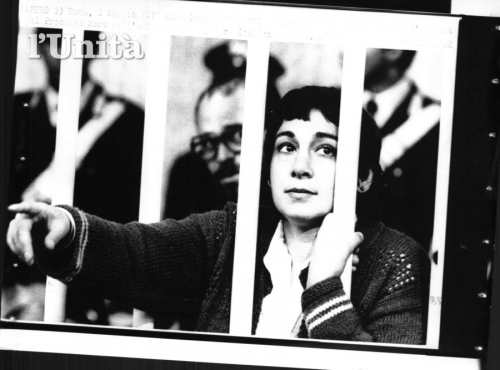

In Enzo De Camillis’s 15 minute silver ribbon winning short, shown at the Roma Film Fest and lauded for its journalistic quality, the much maligned Mambro is portrayed by Valentina Carnelutti (8), who at least partially resembles Mambro. De Camillis, a blood relative of the Alexander in question, (so no conflict of interest there?) indicated his intent in making the movie was to ‘show young people what they do not know, to reflect on a period of history that should not be repeated’. So, following a showing at The House of Cinema to an audience of impressionable students, a discussion is initiated, moderated by Santo Della Volpe (9), who declares at the outset, that ‘The goal of the short is not to re-open old wounds or discussions on the years of lead (10), but to bring to light the issue of the victims that are set aside, of which we no longer speak’.

Really? Well, that is somewhat convenient given the long list of crimes committed by the Italian Brigate Rosse during the period in question. The most notorious being the ambush at Via Fani on the 16th March 1978 and the kidnap and murder of the President of the Christian Democrats, Aldo Moro. But it should also be remembered, especially given the context of De Camillis’s film, that the Left also killed activists from the right wing Italian Social Movement (MSI) and the University National Action group, like Miki Mantakas, murdered in Via Ottaviano in Rome in 1975, and Stephan and Virgilio Mattei, the sons of the MSI party District Secretary for Prati.

It is also a disingenuous claim given the vociferous presence of the Association of Families of victims of the massacre at Bologna train station of 2nd August 1980, whose demands echo down the decades through documentaries and dramas. The latter being the main event used to demonize Mambro and her then lover, now husband, Valerio Fioravanti (11). Although, they have long denied involvement in the Bologna attack, though freely admitting, like their Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (Armed Revolutionary Nuclei) NAR accomplices to other political killings, such as, the assassination of Judge Vittorio Occorsio (12) in 1976 and Magistrate Mario Amato (13) in 1980.

Fioravanti maintains that the bombing was the work of Libya, but the Italian government were reluctant to pursue that line of enquiry because of the state’s dependence on Libya’s oil and blamed neo-fascists instead. Mambro and Fioravanti also confessed to planning an attack on the then Prime Minister Francesco Cossiga (14), so one can hardly accuse them of hiding their intentions. When the initial 16 year prison term for Mambro was converted into house arrest in 1998, the Bologna Association’s President Paolo Bolognesi, described Mambro’s parole as ‘A disgrace. It is outrageous that this parole was granted to a terrorist who does not have the requirements, who was sentenced and has never expressed any feelings of detachment from her past’. This, despite the fact that the NAR, never claimed responsibility for the incident and there is substantive cause to believe that the Mafia Banda della Magliana gang (15) and prominent politician Licio Gelli’s (16) secretive Masonic Propaganda Due P2 Lodge (17) linked to the NATO’s Cold-War Operation Gladio architecture (18) had a hand in the incident.

The prosecution’s main witness against Mambro’s partner Fioravanti, Massimo Sparti, of the banda della Magliana, was even contradicted by his own son. ‘My father has lied about his part in the Bologna history’, he declared. Similarly the sinister presence of German terrorists Thomas Kram and Margot Frohlich, closely linked to both the PLO and Carlos the Jackal, who were in Bologna that very same day was never properly investigated. Coincidences like this and the possible link to the Ustica Massacre (19), when Aerolinea Itavia flight 870 was brought down by a missile, gave President Francesco Cossiga pause for thought, leading him to state on the 15th March 1991 that he felt the attribution of the Bologna Massacre to fascist activists may be based on misinformation supplied by the security services.

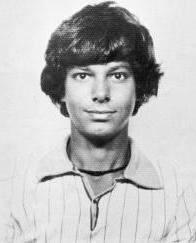

Returning to A Student named Alexander, unlike the Baader Meinhof Complex, the detail is nearly entirely on the victim, showing his cluttered bedroom, his journey by car to the art school in Piazza Risorgimento. No context is provided as to why Mambro and the NAR are robbing the Banca Nazionale on the 5th March 1982. Neither is reference made to the murder of her fellow MSI activists Franco Bigonzetti and Francesco Ciavatta, gunned down in the Acca Larentia by Left extremists, the Armed Squads for Contropotere Territorial, despite the fact that this led Mambro and her cohort to confront both their political opponents and the police in three days of shootings, stabbings and torching cars across Prenestino:

‘A few of us knew what this meant. Francesco Ciavatta was in our small circle. Our immediate reaction was shock, as if a relative had died. We looked at each other not knowing what to do. All around the city young militants flocked to us. The Italian Social Movement did not react. Kids like us were being used to keep order at meetings of Giorgi Almirante (20) , ready to take the blows and hit back . . . Acca Larentia marked the final break with the MSI . . . It could no longer be our home. For three days we shot at police and this marked the point of no return . . .’

— Francesca Mambro

Even, the circumstances of Alexander’s death are disputed. The movie depicts Mambro standing over the boy, firing into his head execution style, apparently mistaking him and his small umbrella for an armed plain clothes policeman. The counter argument is that he was killed in cross-fire as the NAR broke out of a police encirclement. A shoot out in which Mambro did not have in her possession the gun that was identified as the murder weapon and was herself very seriously wounded in the abdomen. She later recalls, hiding out in a garage, where a young doctor visits her and confirms ‘that it is only a matter of time . . . saying I could die . . .’

A discussion followed as to whether or not her compatriots should kill her there and then because she may talk under anesthetic but instead the NAR cell, led by Giorgio Vale (21), who went on later to found Terza Posizione (22), deposited her on the roadside outside an Emergency room.

When Mambro’s Rome based lawyer Amber Giovene challenged the authenticity of the way Mambro is depicted in the movie, claiming it ‘harmed her image’ she was met with a barrage of criticism. The case, overseen by prosecutor Barbara Sargent, was opened three months after the film opened and came like a bolt from the blue to the self-righteous director and the cultural association School of Arts and Entertainment. People in Bologna were whipped up into a state of frenzy, signing a petition in support of the film, which had already received a letter of commendation from the President of the Republic, Giorgio Napolitano. Expressions like censorship and statements like ‘You cannot stop a cultural work, you cannot stop history’, were bandied around with the usual air of moral indignation.

The 2013 Appeal notes relating to the accusation of defamation of Mambro’s character read: due to the benefit of the law, Francesca Mambro, who has never repented of her criminal and terrorist past, nor as ever wanted to work together to build the truth about serious events like the Bologna Massacre, will remain free. The request for the seizure of the short film is extremely serious because it sets a precedent on the freedom of cultural expression, journalism and news, and also because it opens the door to dangerous revisions and attempts to wipe clean historical memory’. The account continues: ‘A country without memory will never understand the present or the future’.

The double standards and contradictions exemplified in the differing responses to A Student Called Alexander and The Baader Meinhof Complex cannot be more stark. Memorialization of such actions are to be glamorized and mythologized if of the Left and censored and misrepresented if of the Right. The word revision is of itself loaded, implying an attempt to challenge supposedly known historical facts and is a term usually reserved for historians deviating from the legend of the Jewish Holocaust. Indeed, it seems that anything that transgresses the Left’s self-serving narrative is to be expunged, cast down the Orwellian memory hole, or twisted beyond all recognition.

Roberto Natale, the auteur of such movie classics as Kill Baby Kill and Terror Creatures from the Grave, also reiterated before his recent demise, that ‘there is a right and duty to tell. Art strengthens the record and citizens need to know. We journalists are on the side of those who stubbornly continue to speak against the custom in our country to silence uncomfortable voices, instead of being willing to speak. This short film has to circulate and be seen in schools, but not only in Rome’.

So, is the movie meant to educate or perpetuate the questionable conviction of Mambro for that specific crime? Be re-assured De Camillis states: ‘I tell you a story, I do not give you a political speech. I want to get out of games of this type. The short film I made for a number of reasons that I think are important. It is a warning to our politicians. Right now, if you do not listen to the needs of young people, you risk terrorism, perhaps we have already. We remember the riots in San Giovanni in Rome in October (23), the bullets that came in envelopes and the letter bombs’.

Then specifically commenting on the release of Francesca Mambro, but of course not being invested in any way, De Camillis adds:

I will not even enter into legal issues because one relies on the judgment of the judiciary already formulated in 1985. But a citizen reflecting on the penalties imposed on others for far less serious offenses fully expatiated are still in prison. Mambro was guilty of 97 murders and was sentenced to nine life sentences. Yet, she walks outside, lives 400 meters from my house, and I may happen across her path by accident. There is a whisper that this story has resurfaced because of my family bonding and friendship with Alexander . . . Who was Alexander Caravillani? He was a boy of 17, he ran with the times, had a girlfriend, and harbored all the fantasies of a 17-year-old. He was not political, nor left or right. He passed in front of the bank, was simply crossing the street, going to school when he was shot, his short umbrella tumbling from his jacket, leading Mambro to believe he was a plain clothes policeman. Then she came back and put a bullet in his head. For that, she was sentenced to life imprisonment.

This is a story, he insists once again, to preserve the history of the years of lead.

And if that is indeed the case, why not tell the story of one of the murdered MSI Youth Front members, Sergio Ramelli, 18; Francesco Cechin, 19; and Paolo Di Nella, 20, contemporaries of Alexander Caravillani (picture) and Mambro, who met their deaths by beating, shooting, and stabbings from Leftist brigands like the Autonomus Workers in the late ’70s and early ’80s? But of course, that will never happen. It does fit their agenda.

And if that is indeed the case, why not tell the story of one of the murdered MSI Youth Front members, Sergio Ramelli, 18; Francesco Cechin, 19; and Paolo Di Nella, 20, contemporaries of Alexander Caravillani (picture) and Mambro, who met their deaths by beating, shooting, and stabbings from Leftist brigands like the Autonomus Workers in the late ’70s and early ’80s? But of course, that will never happen. It does fit their agenda.

On February 11th 2012, De Camillis in direct contradiction to his supposed non-political stance is quoted, ‘Today, the city of Rome is right’, referring to the ‘post fascist’ Mayor Gianni Alemanno (24), MSI Youth Front veteran and graduate of Campo Hobbit (25), who was elected in April 2008 to the sound of Fascist-era songs and shouts of ‘Duce’. ‘Who are those who have called me to present the short film?’ asked Camillis, ‘They are Alemanno’s allies, Berlusconi’s Il Popolo della Liberta (26) . . . When it all came out I was in silence and I decided to just promote it, as I always do. But in the face of this attack, I mean to defend it at all costs. It is a ‘cultural action’ like opposition to gagging journalists. This is a way to silence not only the news but also the authorship of the image’.

There is clearly no intention of admitting even the possibility of bias or inaccuracy. De Camillis and his people are intent on staking their claim to the moral high ground. The following day, Mambro’s lawyer responded: ‘I write in the name and on behalf of the my client Francesca Mambro about the article published yesterday . . . I understand the presentation of the short film flatters the author. But I do not understand the claim that Mambro came back and shot him in the head. I do not know if Mr. De Camillis’s draws from insider sources? Caravillani, unfortunately died in the firefight because a bouncing bullet caused his immediate death. A bullet from an assault rifle that Mambro had never had in her possession, either as she entered the bank or as the NAR shot their way out. The scene is constructed in a way that will definitively condemn Mambro’. When Caravillani was struck, the judges concluded, it was because the young man, after he had run, suddenly found himself in the trajectory of shots fired between the various agents . . . Unfortunately, even the trailers of the short graphically depict Mambro in the disputed manner, astride a guy lying on the ground, shooting the coup de grace . . . I am sure, that in the name of the need to preserve the memory of the years of lead, both you and the newspaper for which he writes would give an account of this correction’. My personal advice is not to hold your breath for a retraction. Smear and distortion is their modus operandi.

Sentenced, for the killing of 9 individuals between May 1980 and March 1982, and the alleged involvement in the massacre of the Bologna bombing on 2nd August 1980, Mambro served 16 years in prison. Sometimes sharing a cell with Anna Laura Braghetti (27) (picture), of the Brigate Rosse, then after 1998 home detention until the 16th September 2008 when she was granted parole on the basis of ‘repeated and tireless dedication to reconciliation and peace with the victims’ families (28). Parole was ended on September 16th 2013 when the sentence was disposed of . . .’

So to end has I began with a quote from a French man of letters, Alexandre Dumas (29), author of The Three Musketeers, ‘she is purely animal; she is the babooness of the Land of Nod; she is the female of Cain: Slay her!’ Or at least besmirch her reputation and disparage her cause so that no one will want to emulate her.

Notes

1. Along with Edgar Allan Poe, Baudelaire identified counter enlightenment philosopher Joseph de Maistre as his maître a penser and adopted aristocratic views. He argued ‘There are but three things worthy of respect: the priest, the warrior and the poet. To know, to kill and to create . . .’

2. Auguste Clesinger (1814-1883), French sculptor who created Bacchante, the Infant Hercules Strangling Snakes, Nereid, and Sappho, was an Officier de la Legion d’honneur.

3. Rudi Dutschke (1940-1979), disciple of Rosa Luxemburg and critical Marxist, survived Josef Bachmann’s attack, but drowned as consequence of having an epileptic fit in the bath.