Review:

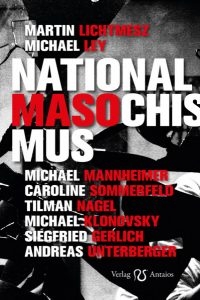

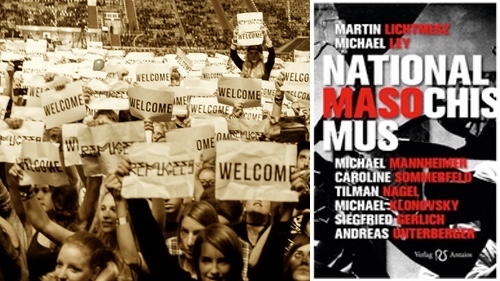

Martin Lichtmesz & Michael Ley (eds.)

Nationalmasochismus [2]

Steigra: Antaios Verlag, 2018

In the Platz der deutschen Einheit (German Unity Square) in Düsseldorf, someone has covered the street name with Simone de Beauvoir Platz. This is one example among many that anyone living in the Federal Republic of Germany may encounter – evidence of the hatred of their country which some Germans feel. Evidence is all around. Now a book has been published stating and stressing this tendency of Germans to despise their birthright and identity.

In the Platz der deutschen Einheit (German Unity Square) in Düsseldorf, someone has covered the street name with Simone de Beauvoir Platz. This is one example among many that anyone living in the Federal Republic of Germany may encounter – evidence of the hatred of their country which some Germans feel. Evidence is all around. Now a book has been published stating and stressing this tendency of Germans to despise their birthright and identity.

Reviewing National Masochismus (National Masochism) places me in an awkward position. I have no wish to be ungracious about the competent and intelligent writers who have contributed to the collection of essays which make up the book, and it may be seen as disloyal to react negatively towards any attempt to take to task what is here described as the “masochism” of the European. Besides, there is an inherent tendency – even a kind of protocol – which insists that those concerned about the predicament of the white race should praise anyone on the same side for their efforts regardless of their quality. The downside of this is that Right-wingers reviewing the writing of people “on their side” lack critical discrimination.

Putting protocol to one side, I believe that National Masochismus is neither a useful nor enjoyable book. It is not poorly written, not untruthful, nor irrelevant, but it offers the reader little new insight and no hope (there are many insights here, but most have been made many times before; of hope, there is none whatsoever that I could find). National Masochismus simply has nothing positive to offer its readers. It is for the most part tedious to read, depressing, and is neither enjoyable nor of practical use, unless one believes enjoyment or practical use can be obtained through having the failings and pathological tendencies of one’s nation or race exposed and condemned with ever more lurid and bizarre examples.

National Masochismus is a collection of nine essays by eight different writers, most but not all of them on the subject of national masochism. Martin Lichtmesz, who has written two of the nine essays, is the author of the book Rassismus, which I have already reviewed for Counter-Currents [3]. In Rassismus, Lichtmesz sought to demonstrate that the bugbear of “racism” used to such effect in contemporary dialogue – or better said, contemporary abuse – is an American import. Lichtmesz called “racism” the “American nightmare.” This collection of essays might have pointed out (but did not) that German masochism, originating in the “shame” of Auschwitz, has spread out to become a European nightmare. What was once a typically German sense of shame about the German past has been gradually extended to embrace the entire West. Europe is saddled with a sense of shame about Europe and Europe’s past, shame about colonialism, shame about slavery, shame about fascism, and shame about racism. Germany had Auschwitz; Portugal, France, and Britain had colonies. Spain has the Conquista. Each white nation to its shame.

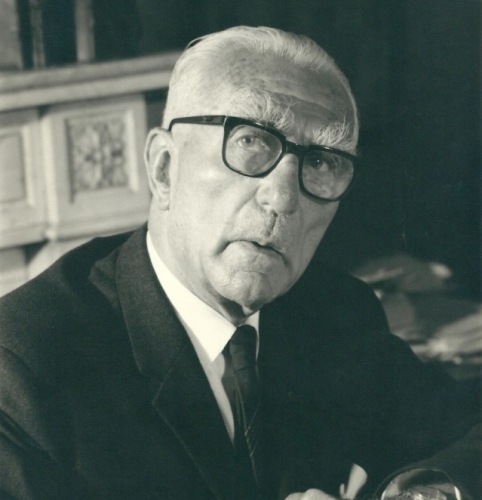

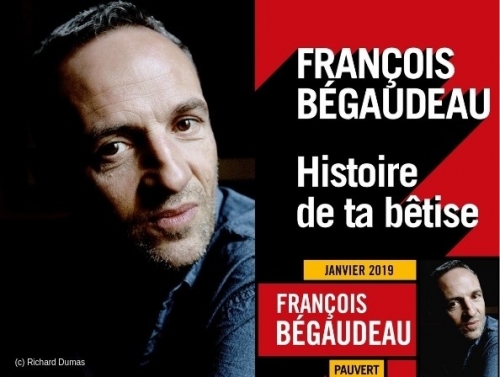

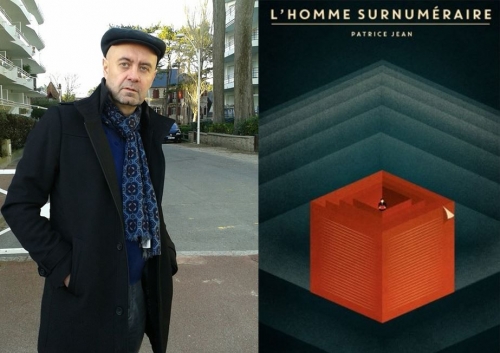

The first essay by Lichtmesz (photo) is an overview of the notion of national masochism. In medical terms, masochism is the desire to obtain and/or the pleasure obtained from pain administered either by oneself or by others to oneself. The earliest use of the expression “national masochism,” according to Lichtmesz, comes from the actor Gustav Gründgens – ironic, if true – since the central figure in Klaus Mann’s Mephisto, Hendrik Höfgen, is a thinly-disguised Gründgens, and that book is a case study in German shame. The novel is about an actor who makes his peace with National Socialism for the sake of his professional career, drawing a parallel between Gründgens working in Germany after 1933 and Faust selling his soul to Mephistopheles for twenty-four years of youth, pleasure, and success. However, this theme had already been appropriated with vastly more skill, talent, and subtlety in his father Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus. Klaus Mann worked for American propaganda during the war and committed suicide in 1949. He himself might serve as an exemplary case of German self-loathing.

The first essay by Lichtmesz (photo) is an overview of the notion of national masochism. In medical terms, masochism is the desire to obtain and/or the pleasure obtained from pain administered either by oneself or by others to oneself. The earliest use of the expression “national masochism,” according to Lichtmesz, comes from the actor Gustav Gründgens – ironic, if true – since the central figure in Klaus Mann’s Mephisto, Hendrik Höfgen, is a thinly-disguised Gründgens, and that book is a case study in German shame. The novel is about an actor who makes his peace with National Socialism for the sake of his professional career, drawing a parallel between Gründgens working in Germany after 1933 and Faust selling his soul to Mephistopheles for twenty-four years of youth, pleasure, and success. However, this theme had already been appropriated with vastly more skill, talent, and subtlety in his father Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus. Klaus Mann worked for American propaganda during the war and committed suicide in 1949. He himself might serve as an exemplary case of German self-loathing.

It is true, as Lichtmesz urges – as many have before him – that the German sense of guilt and shame at being German exceeds that of other European nations. This extreme self-loathing has its roots in the so-called Umerziehung (reeducation) that was carried out in post-war education and propaganda. It is not difficult to find examples to substantiate the case that the rejection of National Socialism in Germany is more than the rejection of a political doctrine; it is in fact a form of masochism, a mental sickness. Lichtmesz offers the example of Philippe Ruch to illustrate his point. Ruch was born in Dresden in 1981 and is the leader of an “alternative” arts troupe. In the manifesto of what he calls the group’s “aggressive humanism,” Ruch raves about himself and his fellow Germans. I have tried to render the awkward style of the original German in English:

We are the country of organizers and creators of the Holocaust. Our ancestors exterminated millions of people. They bumped off millions of innocent civilians. It cannot be repeated often enough: Germany struck the severest blow against humanity in the history of the human race. The moral core of the Federal Republic is the oath to ensure that genocide is banished for all time. The right to enjoy privileges as a German goes hand in hand with the awareness of a unique moral imperative. All those who do not live their lives in awareness of that imperative are politically illegitimate, they bask in a legitimation to which we only have a right on the assumption of that oath (p. 219).

This sort of writing substantiates Lichtmesz’s thesis that German self-loathing in respect of their own past is pathological, and borderline insane.

The second chapter of the book is an essay by Michael Ley, writing, as he says, in the tradition of the Enlightenment. Unlike Left-wing commentators and activists, Ley, who is Jewish, is consistent in his faith in the Enlightenment principles of free speech, individualism, and human rights, for he draws the logical conclusion from his rationalist and Enlightenment beliefs that Islam poses a direct threat to those beliefs. Trying to live in harmony and peace with this religion, so Ley, is a fatal delusion. The reader is confronted again with an example to illustrate the pathological dimensions of German – or in this case Christian – self-abnegation. In Ley’s example, the Archbishop of Cologne commissioned a life-sized model of an Islamic migrants’ boat to be set up outside Cologne Cathedral. Ley goes so far (p. 35) as to describe the demolition of intact buildings as a continuation of the “collective suicide” of the West, of which ignoring Islam’s challenge is the latest manifestation.

Dr. Michael Ley

Ley’s essay throws up the conundrum regarding Israel. Should those defending a European identity against Islamic migration identify with Israel on the grounds that the enemy of my enemy is my friend? In light of the Islamic mass migration into Europe now taking place, many Right-wingers who were formerly sympathetic to Islam – as in, for example, supporting the Mujahideen in Afghanistan fighting the Soviets – have now veered towards sympathy for Israel. The late Guillaume Faye and Steve Bannon come to mind.

In the third chapter, Michael Mannheimer begins his contribution, which is entitled “Vom Nationamasochismus zum nationalen Suizid” (From National Masochism to National Suicide), with an example of what must be regarded as derangement in this statement by a journalist named Wiglaf Droste (p. 41):

The German people have the moral duty to die out, and quickly. Every Pole, Russian, Jew, Frenchman, Black African, and so on has as much right to live on the German land – which has been talked about as though it were holy or blessed – as any German, if not more so (Heinz Nawratil, Kult mit der Schuld [Munich: Universitas, 2012], p. 9).

Michael Mannheimer, who is a leading critic of Islam and who has been subjected to many attacks by the Left, does not subscribe – as do many critics of Islam, such as Guillaume Faye – to the view that Israel is a bastion for the defense of the West (on his blog, he recently published a piece suggesting that the Christchurch massacre may be a Mossad “false flag”). He focuses on the reality of demographics, and cites the sobering fact that in 1950, ninety percent of the population of West and East Germany was ninety-nine percent German, but that in 2018, forty percent (!) of those living in Germany have non-German roots. The turnaround year is projected to be 2035, when more than half the population of Germany will be non-German (p. 43). If he differs with Ley concerning Israel, Mannheimer concurs entirely in drawing attention to the activity of the so-called anti-fascists, whom he describes as “a weapon to crush alternative political opinions,” and especially that no demonstration against Islam or against the replacement of the native population of Germany can take place without the presence of professional anti-fascists (p. 56). It seems to this reviewer that the anti-fascists are a European export to the United States, where they are known by their German abbreviated form as “antifa” – a Coca-Cola infection in reverse.

Mannheimer is a friend of the Federal Republic’s Constitution, a point about which many readers may part company with him, but it is hard to disagree that the government of the Federal Republic and its supporters has begun to abandon its former sense of duty to abide faithfully to the spirit and letter of that Constitution. Mannheimer notes:

The Merkel government is now breaking German laws practically on a daily basis, massively supported by the media, churches, and unions. She is breaking Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution, which binds all governments to uphold existing law (p. 61).

Whereas in the past, the Bonn and Berlin governments could at least claim that they were acting within the bounds of the constitutional rights accorded to them in the establishment of the Federal Republic in 1949, Merkel’s unilateral decisions, which even Right-wingers sometimes implausibly interpret as a “mistake,” is a breach of the provisions of the Constitution, and therefore illegal. Mannheimer regards the failure of the Bundestag to oppose Merkel as capitulation to what Josef Isensee called a Staatsstreich (coup) (p. 61):

A coup from above is a breach of the Constitution on the part of an organ of the state. It can result from inactivity, be it that of institutions set up by the Constitution being cleared away, be it that Constitutional duties are not fulfilled . . . If the organs responsible widely fail to guarantee the free individual safety and security, they will have lost their right to expect obedience from their subjects, and resistance (Widerstandsfall) is the order of the day (Josef Isensee, Das Legalisierte Widerstandsrecht [When Resistance is Legal] [Bad Homburg: Gehlen, 1969], p. 28).

Mannheimer believes that Germany has shifted from being a parliamentary democracy to become what he calls a “parliamentary dictatorship” (p. 62):

Even the politicians of the old conservative parties seem to be intoxicated by their own decline. The slightest opposition to the collective suicide of one of the greatest cultures and nations of the world will be declared “Nazi” or “racist” by a phalanx of politics, the media, and the church (p. 68).

The fourth essay, by Caroline Sommerfeld, brings some humor into what is a deadly earnest subject, and one treated with unrelenting earnestness in most of this book. She considers the psychological implication of the book’s title, namely the manifestation of the pathology of the drive to spiritual, and ultimately biological, self-harm that has germinated in the soil of the modern German psyche. Her essay is not only the sole amusing contribution, but it is the only piece which seems to me to approach the subject from an original perspective and in an original way. The style is discursive, even chummy, and the perspective very personal. Much of the contribution is an account of dialogues she had with her husband, or other people she knows. First, the reader is introduced to a supposedly “conservative” married couple in Berlin. A well-to-do mother is talking to the mother, Caroline Sommerfeld:

She: I think it is a good thing that there are always more brown children. At some stage, blonds will have died out.

Me: And you think that is good?

She: What is good about being blond? The white race has done so much wrong on this planet that it’s a good thing if it dies out (p. 71).

Sommerfeld humorously describes the reductio ad absurdum of the “blonde and blue-eyed,” Buddhistically-inclined, well-to-do mum. This mother rejects racialism for reasons which take fatalism to an altogether new level:

And so you think it is important to maintain white genes? Look, in a hundred years all people will be of mixed blood, and that’s good. Anyway, I see things in a Buddhist way, with no enemies – only teachers on the way. And you need to think globally. One day, humanity will have died out; the Sun will expand, and the whole planet will be destroyed (p. 72).

Caroline Sommerfeld speaking at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2018

Sommerfeld refers approvingly to Martin Sellner of the Austrian branch of Generation Identity for giving the Western world’s masochistic leaders the designation of sect (p. 73). The greater part of her contribution is taken up with an analysis of discussions she has had with her much older husband. He was born in 1939, she in 1979; their age difference provides her with the opportunity to analyze, as she puts it:

. . . what must have happened after 1945 to account for the narrative of the disappearance of the notion of “my own,” a narrative which includes the dissolving of frontiers, nations, and peoples in the cause of globalization, and in which international solidarity replaces national solidarity, and where there is a worldwide exchange of goods, money, and people, and that this is seen not only as a historical imperative, but to be good in itself and necessary (pp. 78-79).

I disagree that the course of events is primarily presented in terms defined by those who accept globalization as a good in itself. Of course there are those who stress their belief that globalization is ipso facto a good thing, but from my experience, the development is much more often seen as something inevitable; people are resigned to it. It is accepted as an inexorable development, rather as Marx insisted that the collapse of capitalism and its transformation into socialism was scientific and inexorable. However, a shift from optimism to fatalism among proponents of globalism may just reflect a difference between generations among one-worlders, with earlier generations greeting globalization as a step in the constant self-improvement of mankind, and a later generation more dispassionately regarding it as inevitable and ethically neutral; a development for which there is “no alternative,” as Merkel justified her own decisions.

Sommerfeld notes – quite correctly, in this reviewer’s opinion – that a major strategy of those who adhere to what she describes as an “alien paradigm” argue against any right of a nation, people, or race to self-determination or survival by insisting that the race or nation in question is a construct of history, enjoying no objective reality. Here we come back to the idea that those in power belong, if not to a conspiracy, at the very least to a sect (whether they do so consciously or unconsciously, she does not discuss). This sect denies as a matter of strategy the existence of that which it seeks to destroy: the white race. Sommerfeld makes a telling point at the end of her contribution:

We are much too much on the defensive. If pressed to acknowledge Germany’s unending guilt, the answer has to be: What do you like so much about a sense of guilt that you expect everyone to share it? What is so wrong about being far-Right? What is wrong with sexism? What is your problem with anti-Semitism? (p. 94)

She explains that she poses these questions for the purpose of studying her husband’s reaction to them. More’s the pity. I believe such questions should be posed to try and get some answers from the only race in the history of mankind which is busily clamoring for its own destruction.

But why is National Masochismus stressing the obvious – not once, but repeatedly? An apt way of describing what these writers are doing is psychologically flagellating themselves. Masochism, ironically, is on full display in these very writings: the writers relish in talking about German shame, ignorance, and decline. And National Masochismus is over 200 pages long.

For my part, I do not believe that the masochism described here is representative of most Germans. It is the masochism of the opinion-makers, not of a majority of the indigenous citizens. In all my experience of talking with Germans, I have heard at the most extreme that a person “does not care,” or is indifferent toward the fate of blonds or the white race, but I have never heard the wish expressed that blonds would do well to die out, or that it will be grand if everyone becomes coffee-colored. On the contrary, a Communist lady (a card-carrying party member, as it happens) said to me in response to regret I expressed concerning the decline of white people, “If you like blonds so much, you should go ahead and marry a blond and have a bevy of blond children. No one is going to stop you.” Thus, in my experience, it is a minority of Germans who are consciously pathological in the manner described in this book. The masochism is accepted with resignation by millions because it is dictated and urged by authority, and Germans, of all people, tend to believe in the inherent legitimacy of certified authority. The reaction of the average German to the masochism described in this book is less to embrace than to ignore it, offering only by way of submission the token sacrifice of widespread self-deprecation regarding some of the smaller things in life. (Example: “Germans go totally overboard when it comes to tax regulation. It’s typically German to make it so complicated!”)

This book exudes a negativity which works on the assumption that a majority of people are committed to the masochistic pleasures which are described and illustrated here, but the writers fall into the error of confusing the opinions of the elite with the acquiescence of the mass. It is not that I am suggesting that the mass is consciously opposed to what the masochists are doing and the damage they are causing, but rather that they are indifferent to it, and they are not so much “brainwashed” (that favorite mantra of Right-wing critics) as stultified and stupefied. They have other things than their country’s masochism or shame on their minds.

A chapter by Tilman Nagel on the Islamic religion simply stresses the incompatibility of Islam with Western society, and seems hardly relevant to the thesis of the book, unless it is to stress the masochism which indeed is likely to be a factor for people who welcome migrants to their country who will be toxic to their way of life.

The sixth chapter by Michael Klonovsky bears the peculiar sounding title of “Betroffenheitsathleten. Aus den Acta Diurna 2014-2017” (Athletes of Consternation: From the Acta Diurna, 2014-2017). In colorful language, Klonovsky recounts his reaction to daily events and statements which serve to illustrate German masochism. He begins by quoting a statement made by one of Dresden’s mayors that “Dresden was not an innocent city” (p. 119) – a masochistic declaration of a particularly distasteful kind, since it implicitly justifies the three-day destruction of a defenseless refugee city by the RAF and US Air Force, which was a war crime if the term “war crime” itself has any meaning. It was an act of terrorism which, given the extent of the destruction it caused, its cold-blooded determination to murder, and its efficiency and thoroughness in committing murder exceeded every act of Islamic terrorism in modern times by far.

Picture, right: Michael Klonovsky

Klonovsky’s writing style is not unlike that of Tarki and other journalists at the British Spectator: intelligent, angry, snide. He recounts a program about Hans Michael Frank and an interview with his son, Niklas Frank. Niklas Frank takes masochism to new heights by explaining that everywhere he goes, he carries a picture with him depicting his father hanging from the gallows at Nuremberg. That way he can always reassure himself that Daddy “is well and truly dead” (p. 123). This must have been a repeat of an old program, since I remember a German girlfriend of mine being appalled by Niklas Frank when she watched the program on television in the late 1980s.

Klonovsky’s writing style is not unlike that of Tarki and other journalists at the British Spectator: intelligent, angry, snide. He recounts a program about Hans Michael Frank and an interview with his son, Niklas Frank. Niklas Frank takes masochism to new heights by explaining that everywhere he goes, he carries a picture with him depicting his father hanging from the gallows at Nuremberg. That way he can always reassure himself that Daddy “is well and truly dead” (p. 123). This must have been a repeat of an old program, since I remember a German girlfriend of mine being appalled by Niklas Frank when she watched the program on television in the late 1980s.

After describing the perverse show, the book proceeds to offer more examples of German self-loathing. My feeling by this stage was, “Yes, all right! I’ve got the message! You don’t have to go on about it anymore.” But go on about it these writers surely do. Harping on the subject of their own self-hatred is the Right-wing German’s way of being anti-German, and paradoxically fulfilling the role which the victors of 1945 gave to the defeated nation. This book indeed proves how masochistic some Germans are today, by either enjoying the rejection and denouncing of their nation or writing and reading about those who do so.

Another instance of self-loathing cited here (and let this by the last example for the purposes of this review) is the changing of names. Names of schools, institutions, barracks, and street signs are often replaced in order to erase any hint of a tribute to anyone or anything associated with the “dark years” of 1933-1945. Not only are the names of people associated with – or even approved of – by the government of those “dark years” being erased, but those who might in any way be seen as having an unsound connection to them – such as having been a forerunner, for example – is subject to scrutiny, and where deemed appropriate, given the equivalent of an anti-smoking health warning. According to Klonovsky, the list of individuals thus tainted in one German city, Freiburg, includes Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Theodor Körner, Richard Wagner, Richard Strauss, and – here one may indeed question the sanity of the masochists – Carl von Linné. Given that the sect of self-loathing whites who decide these things deny the very existence of human races, it is ominous that a cautionary explanation has even been issued against the inventor of the Latin nomenclature for fauna and flora. What is unsound about the hapless Linné? Perhaps it is because he ascribed the various races of man to subspecies status, and thus is considered potentially racist, or perhaps he once spoke disparagingly of broad-nosed, wooly-haired savages.

Has the reader had enough? I dutifully read the entire book, which certainly has trenchant observations and is all-in-all a hard-hitting exposure of what it claims is a national psychological malaise. Siegfried Gerlich rightly points out that Germans suffer, and have always suffered, from a compulsion to plagiarize; maybe it lies in their oft-observed dearth of imagination. But one comment did strike me as simply wrong, however, and its wrongness is significant. In the eighth chapter, Andreas Unterberger states that one finds “real national masochism only in Austria and Germany” (p. 205). I do not know what “real masochism” is, as opposed to “unreal masochism,” but it is a characteristic error of Right-wingers to claim almost with perverted pride that their nation is “worse off” or “further down the road” than other nations. Perhaps this form of nationalistic masochism is especially prevalent among Germans, but it is not unique to them.

In providing an array of writers to express their disdain and bewilderment at their nation’s suicidal self-loathing in different ways, both the editors and contributors of this book provide the paradoxical evidence to back their own argument – namely, that German writers indulge in self-deprecation and self-loathing to a pathological degree.

This book’s contributors disregard two major factors at work which serve to explain the passivity of the mass of Germans in the face of the consistent denigration of their own nation. Perhaps because the book is focused on masochism, they did not consider it relevant, but it offers other causes for the malaise which so often is blamed on the specifically German Umerziehung (reeducation) and Vergangenheitsbewältigung (overcoming the past). I would stress again that I do not share the implicit argument of this book that the masochism displayed by the sect of Federal Republic bigwigs is a widely-held phenomenon, or unique to Germany. In my view, the German masses are indolent and ignorant; too much so to be masochistic.

The first, specifically German, element of the phenomenon is that partly through political propaganda and education (which is more or less the same thing in modern Germany), and partly through folk memory and accounts handed down through the generations, and linked – but not identical to – a sense of guilt, Germans in their great majority are strongly antithetical to war. This means not only wars between nation-states, but war in any form, including war within the state, or even political war at the simplest level of robust rhetoric. As Rolf Peter Sieferle noted in his posthumously published Krieg und Zivilsation (War and Civilization), his study of history at university was marked by an avoidance of the subject of war, and he was amazed when he went to England to see how many books there were on the history of war and war-craft in the London bookshops.

Out of a masochistic sense of shame regarding its military past, Germany eschews war as a topic, and German society regards even public disputes as essentially undesirable. Consensus is the priority of German political life. Consequently, the German Parliament is stupefyingly anodyne. Nothing much happens on the public political stage, and comparatively seldom do prominent personalities clash in public. The important work of horse-trading and lobbying – which is all German politics is – is carried out in committee, unseen by outsiders, and not monitored by the media. German politicians employ a kind of sterile and sanitized language so as not to provoke clashes of personality and principle. The dirty work of engaging in a war against radical Right-wing opponents of the system is left to the “antifa,” whose comportment and even dress significantly plagiarizes and satirizes the historical National Socialists it loves to imagine are all around.

A second factor which is ignored in National Masochismus – albeit not specifically German at all, but which is nowhere more pronounced than in Germany – is the ruling sect’s indifference to the low levels of health and education among large swathes of the population. Not only the rulers of Germany, but also the nationalists and identitarians of different hues who challenge the status quo, do not acknowledge the low state of self-esteem (is that masochism?) and health which characterizes so many Germans. Proponents of multiculturalism frequently seize on this as firstly a reason to “pep up” society by importing labor “which the indigenous population will not do,” and secondly to ridicule the overall inferiority of those opposing immigration and the replacement of the indigenous population by healthy, young “new citizens.”

A cartoon in the national press makes the point: It shows a group of smiling, happy-looking migrants arriving in Germany being confronted by ill-kempt and obese native Germans. “Ihr seid nur hier wegen dem Geld!” (“You are only here because from the money!”) a native German cries. “Nein, wir sind hier wegen des Geldes” (“No, we are here because of the money”), responds the dark-skinned newcomer. The joke mocks the low educational level of many German “nativists,” and especially the inability of many Germans to speak their own language well. It is true that the level of their own language spoken by many Germans is often very low, indeed. For example, it is common to hear what translated would be the equivalent in English to “bigger as,” “because from,” “if I would know,” and the like. Those who advocate for the replacement of the native German population like to stress – if not always as frankly as in the cartoon which I have cited – the low standards of health and education among ethnic Germans as compared to the high levels among many of the “new citizens.” Opponents of immigration either ignore this entirely, or consider such mockery further proof of the elitism of the ruling sect. The issue of the poor health, comportment, and education of the average ethnic German is ignored in this book. A book of 247 pages is published dealing with the way in which Germans “do their country down” as a pathological system of post-war reeducation, but it does not have a word to say about those aspects of German life about which Germans have a genuine reason to be ashamed.

The other side of this is that millions of ethnic Germans are pampered, indolent, and pacifistic. This state of affairs results from the enormous material gains made by post-war Germany and Austria. Practically every citizen can afford a car (and an expensive car at that), every employee enjoys paid holidays of five weeks per year, and lives under stringent rental and employment protection laws, retiring – often at an early age – with a guaranteed pension linked to previous earnings. It is surely obvious that such levels of comfort and financial security tend to make people soft and less inclined to fight for anything, especially as they have much to lose, but it is remarkable the extent to which Germans see no paradox here when they bemoan their lot. It is not always easy to take someone seriously who claims that the country is in rapid decline because of immigrants, and then cites national masochism as the reason, when that same person owns a Mercedes, drinks as much quality wine and beer as he or she wishes, and flies to Thailand on holiday. Thus, Michael Klonovsky – a not altogether oppressed member of the native population – apparently unconscious of the irony, introduces his critique of modern German society by mentioning what he was eating and drinking. He does not name his hotel, but my hunch is there were several stars next to its name:

Yesterday evening, convivially blessed with Wagyu Entrecôte and Châteauneuf-du Pape, I sought out my Berlin hotel. Not properly tired, I managed to avoid the trap of the hotel bat, but not the trap of the television . . . (p. 122)

Germans complain of tax and financial hardship, but changing one expensive car for another every few years is not uncommon (it is very rare to see an old banger on German roads), and the restaurants and cafés in the major cities do a booming business. Health insurance is mandatory. Critics of modern Germany may drown their sorrows in a good meal consisting of the most expensive kind of steak money can buy, accompanied by an exclusive and pricey wine. In terms of well-being, modern ethnic Germans present something of a paradox: many suffer from poor health, and live in accommodations which many Americans would find shockingly cramped; and low levels of property ownership (one of the lowest in Europe) and poor health go hand-in-hand with widespread health insurance coverage, child benefit payments, maternity leave, and rental and employment security. What all these partially contradictory aspects of modern German life have in common, however, is that they lower the fighting spirit of the citizens. The writers of National Masochismus have not a word to say about the lack of national spirit created by comfort and investment as it pertains to the well-being of the state, which ensures docility among the masses in the face of the masochism apparent among the state’s rulers and trendsetters.

The book also fails to make any distinction between the Germany of the immediate post-war years – where the political system of the Third Reich was thrown overboard, but conservative values remained very much in force – and the changes which came in the 1960s, which heralded a wholesale rejection of the puritanism of the ‘50s such that National Socialism and conservatism were regarded as much the same beast to a far greater extent than in other nations. This and much more could have been examined in a book on national masochism, rather than essays concentrating on the threat of Islam. It is not even clear whether this book is only about German national masochism. The title speaks of only national masochism, and most of the book concentrates on Germany, but the last chapter of the book, which is by Martin Lichtmesz, carries the title “White Guilt” and “White Genocide” – expressions very familiar to anyone involved in “the movement” in the United States – and in it, Lichtmesz looks at the devaluation and declining respect for whiteness in the United States.

This book is hard-hitting and at times entertaining, but none of the writers here outline any kind of plan for change, be it ever so vague. What is the purpose of this book other than to underline how dire the situation of white folk is?

The masochism the writers here describe and illustrate with many examples is proof of their own masochism. National Masochismus is a case study in national pathology which discusses no other aspects of the problem other than national masochism to account for the feebleness of the white man, and specifically the German, in the face of long-term racial and territorial dispossession. In an especially disheartening contribution by Siegfried Gerlich on German reeducation (Umerziehung), he quotes the American Vice President Henry A. Wallace: “The German people must learn to unlearn all that they have been taught, not only by Hitler, but by his predecessors in the last hundred years” (p. 169). This book provides ample examples of the success of that unlearning – if not among the German masses, at least among the decision-makers and people of influence. But who among this book’s readers will be greatly influenced by it? What is National Masochismus hoping to achieve? For whom is it even written? Those in prior agreement are unlikely to become more convinced by these texts. It only reinforces what they already believe. And those who hold to the establishment’s narrative will not change their views because of this book. Finally, there is nothing “sexy” enough in any sense of the word to induce the “don’t knows” to read this book and have their opinions swayed.

I look forward to reviewing a book for Counter-Currents which provides not an account of the success of the governing sect, but an account of those who are proposing recipes for change; a report not from pathologists, but from those striving to find a cure and demonstrating the wherewithal to overthrow the masochistic sect.

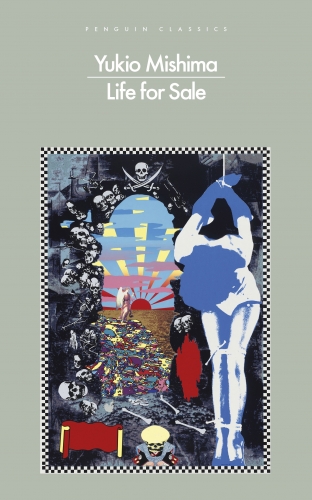

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

One of the seminal ideological battles of recent history has been that between internationalism, in one form or another, and nationalism. Countless words have been devoted to dissecting the causes, effects, merits, and drawbacks of the various incarnations of these two basic positions. Neoliberalism has, however, succeeded in becoming the dominant internationalist ideology of the power elite and, because nationalism is its natural antithesis, great effort has been expended across all levels of society towards normalizing neoliberal assumptions about politics and economics and demonizing those of nationalism.

One of the seminal ideological battles of recent history has been that between internationalism, in one form or another, and nationalism. Countless words have been devoted to dissecting the causes, effects, merits, and drawbacks of the various incarnations of these two basic positions. Neoliberalism has, however, succeeded in becoming the dominant internationalist ideology of the power elite and, because nationalism is its natural antithesis, great effort has been expended across all levels of society towards normalizing neoliberal assumptions about politics and economics and demonizing those of nationalism. Slobodian begins with the dramatic shift in political and economic conceptions of the world following the First World War. As he observes, the very concept of a “world economy,” along with other related concepts like “world history,” “world literature,” and “world affairs,” entered the English language at this time (p. 28). The relevance of the nineteenth-century classical liberal model was fading as empire faded and both political and economic nationalism arose. As the world “expanded,” so too did the desire for national sovereignty, which, especially in the realm of economics, was seen by neoliberals as a terrible threat to the preservation of the separation of imperium and dominium. A world in which the global economy would be segregated and subjected to the jurisdiction of states and the collective will of their various peoples was antithetical to the neoliberal ideal of free trade and economic internationalism; i.e., the maintenance of a “world economy.”

Slobodian begins with the dramatic shift in political and economic conceptions of the world following the First World War. As he observes, the very concept of a “world economy,” along with other related concepts like “world history,” “world literature,” and “world affairs,” entered the English language at this time (p. 28). The relevance of the nineteenth-century classical liberal model was fading as empire faded and both political and economic nationalism arose. As the world “expanded,” so too did the desire for national sovereignty, which, especially in the realm of economics, was seen by neoliberals as a terrible threat to the preservation of the separation of imperium and dominium. A world in which the global economy would be segregated and subjected to the jurisdiction of states and the collective will of their various peoples was antithetical to the neoliberal ideal of free trade and economic internationalism; i.e., the maintenance of a “world economy.”

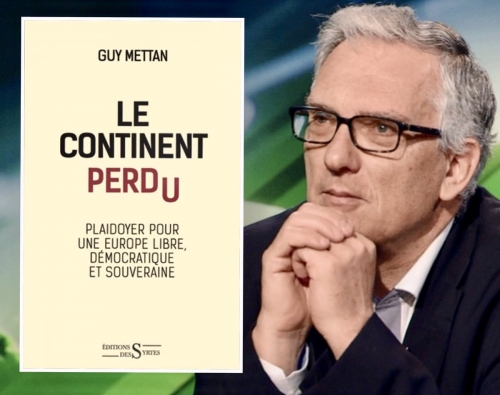

Philippe de Villiers en vilipende les fondements intellectuels. Ceux-ci reposeraient sur un trio infernal, sur une idéologie hors sol ainsi que sur un héritier omnipotent. Le trio regroupe Robert Schuman, Walter Hallstein et Jean Monnet. Le premier fut le ministre démocrate-chrétien français des Affaires étrangères en 1950. Le deuxième présida la Commission européenne de 1958 à 1967. Le troisième incarna les intérêts anglo-saxons sur le Vieux Continent. Ensemble, ils auraient suscité un élan européen à partir des prémices du droit national-socialiste, du juridisme venu d’Amérique du Nord et d’une défiance certaine à l’égard des États membres. Quant à l’héritier, il désigne « le fils spirituel (p. 255) », George Soros.

Philippe de Villiers en vilipende les fondements intellectuels. Ceux-ci reposeraient sur un trio infernal, sur une idéologie hors sol ainsi que sur un héritier omnipotent. Le trio regroupe Robert Schuman, Walter Hallstein et Jean Monnet. Le premier fut le ministre démocrate-chrétien français des Affaires étrangères en 1950. Le deuxième présida la Commission européenne de 1958 à 1967. Le troisième incarna les intérêts anglo-saxons sur le Vieux Continent. Ensemble, ils auraient suscité un élan européen à partir des prémices du droit national-socialiste, du juridisme venu d’Amérique du Nord et d’une défiance certaine à l’égard des États membres. Quant à l’héritier, il désigne « le fils spirituel (p. 255) », George Soros. Outre le rappel du passé national-socialiste de Hallstein, il insiste que Robert Schuman, « le père de l’Europe fut ministre de Pétain et participa à l’acte fondateur du régime de Vichy (p. 67) ». Oui, Robert Schuman a appartenu au premier gouvernement du Maréchal Pétain. Il n’était pas le seul. Philippe de Villiers ne réagit pas quand Maurice Couve de Murville lui dit à l’occasion d’une conversation au Sénat en juillet 1986 : « Je me trouvais à Alger […] quand Monnet a débarqué. J’étais proche de lui, depuis 1939. À l’époque, j’exerçais les fonctions de commissaire aux finances de Vichy (p. 109). » L’ancien Premier ministre du Général De Gaulle aurait pu ajouter que membre de la Commission d’armistice de Wiesbaden, il était en contact quotidien avec le Cabinet du Maréchal. Sa présence à Alger n’était pas non plus fortuite. Il accompagnait en tant que responsable des finances l’Amiral Darlan, le Dauphin du Maréchal !

Outre le rappel du passé national-socialiste de Hallstein, il insiste que Robert Schuman, « le père de l’Europe fut ministre de Pétain et participa à l’acte fondateur du régime de Vichy (p. 67) ». Oui, Robert Schuman a appartenu au premier gouvernement du Maréchal Pétain. Il n’était pas le seul. Philippe de Villiers ne réagit pas quand Maurice Couve de Murville lui dit à l’occasion d’une conversation au Sénat en juillet 1986 : « Je me trouvais à Alger […] quand Monnet a débarqué. J’étais proche de lui, depuis 1939. À l’époque, j’exerçais les fonctions de commissaire aux finances de Vichy (p. 109). » L’ancien Premier ministre du Général De Gaulle aurait pu ajouter que membre de la Commission d’armistice de Wiesbaden, il était en contact quotidien avec le Cabinet du Maréchal. Sa présence à Alger n’était pas non plus fortuite. Il accompagnait en tant que responsable des finances l’Amiral Darlan, le Dauphin du Maréchal !

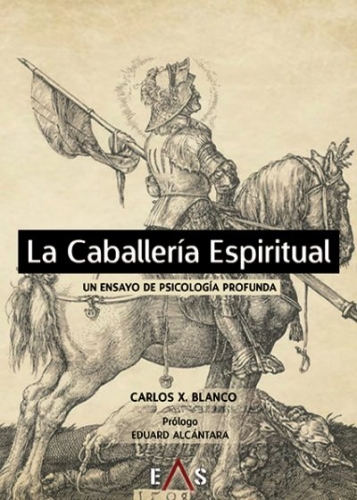

Es en dos etapas bien diferenciadas en donde cabe hablar de la prosapia hispana de la filosofía. Hubo una primera -pero ya remota- etapa de realismo escolástico, en la Edad Moderna, esto es, en los siglos áureos del Imperio. Hubo y hay otra etapa, mucho más reciente, presidida de forma contemporánea por el vitalismo filosófico de nuestro Unamuno y de nuestro Ortega. Es de este vitalismo de donde partimos hoy en la hispana filosofía y de donde, según los pasos que muestra Manuel F. Lorenzo, podemos beber y alzar nuevas construcciones del pensamiento. El vitalismo hispano, como el de toda Europa, bien podría bascular en dos direcciones, entre sí antagónicas. Una dirección posible, hacia donde inclinar su peso, es claramente irracionalista. La Vida como opuesta a la Razón, la Vida como primum que no atiende a razones, que siente las razones como enfermas y como lastres, como artificios y excrecencias. Los pensadores germanos han sido pródigos en este vitalismo irracionalista e irracional. Schopenhauer Nietzsche, Klages, son nombres que acuden entonces a la mente, y su filosofía hiriente incomoda a todo aquel que busca incólumes certezas, cimientos lógico-matemáticos, solideces de plomo, granito y acero. Eran aquellos filósofos de la vida enemigos de la ratio rebeldes muy a la alemana, esto es, rebeldes dados a la reacción.

Es en dos etapas bien diferenciadas en donde cabe hablar de la prosapia hispana de la filosofía. Hubo una primera -pero ya remota- etapa de realismo escolástico, en la Edad Moderna, esto es, en los siglos áureos del Imperio. Hubo y hay otra etapa, mucho más reciente, presidida de forma contemporánea por el vitalismo filosófico de nuestro Unamuno y de nuestro Ortega. Es de este vitalismo de donde partimos hoy en la hispana filosofía y de donde, según los pasos que muestra Manuel F. Lorenzo, podemos beber y alzar nuevas construcciones del pensamiento. El vitalismo hispano, como el de toda Europa, bien podría bascular en dos direcciones, entre sí antagónicas. Una dirección posible, hacia donde inclinar su peso, es claramente irracionalista. La Vida como opuesta a la Razón, la Vida como primum que no atiende a razones, que siente las razones como enfermas y como lastres, como artificios y excrecencias. Los pensadores germanos han sido pródigos en este vitalismo irracionalista e irracional. Schopenhauer Nietzsche, Klages, son nombres que acuden entonces a la mente, y su filosofía hiriente incomoda a todo aquel que busca incólumes certezas, cimientos lógico-matemáticos, solideces de plomo, granito y acero. Eran aquellos filósofos de la vida enemigos de la ratio rebeldes muy a la alemana, esto es, rebeldes dados a la reacción. La razón vital no se limita pensar en y desde "el hombre de carne y hueso". La razón vital implica que la vida humana no es sólo razón, pero sí es ejecución de actos en orden a una gestión de la vida misma, una gerencia y construcción que se hace de acuerdo con principios racionales. El hombre no es, para nada, un autómata racional, sino un sujeto orgánico cuya forma humana de adaptación y supervivencia psicobiológica exige la racionalidad. El hombre viene definido, en rigor, no por una sustancial cogitación ("yo soy una cosa que piensa") sino por una actividad circular, por un circuito entre el Yo y las Cosas (el "no-Yo" de Fichte). Ninguno de los polos del circuito debe ser reificado de antemano, ninguno ha de ser tratado acríticamente como una cosa o sustancia. La constitución de los dos polos, yo y mundo ("circunstancias"), consiste precisamente en el lanzamiento de series de acciones en las que el Yo se hace con el Mundo y recíprocamente el Mundo se presenta y re-presenta ante el Yo. La filosofía de Ortega, que tantas veces bebe de la fenomenología y del existencialismo alemán, es vitalista por cuanto que plantea siempre un sujeto humano orgánico definido como un verdadero sistema racional de operatividad, para quien conocer es, de otro modo, coextensivo con sobrevivir y "hacerse con el mundo". Las circunstancias orteguianas, como el "medio" (Umwelt) de los biólogos, conforman el espacio de las operaciones, un espacio que da pie a redefinir la experiencia en términos de construcción. Ortega no quería echar por la borda la razón, aplastarla bajo el peso de una salvaje o bestial Voluntad o Vida. Antes bien, quería explicar el hecho humano mismo de la razón. Al proceder así, al avanzar desde la dialéctica de Fichte, el raciovitalismo del filósofo madrileño ofrece un programa genético del racionalismo tanto como del empirismo. Se trata de volver al genuino espíritu con el que nació el idealismo: la superación de la magna filosofía europea de la Modernidad, tanto el empirismo isleño como el racionalismo continental, una superación que acude a la génesis misma del conocimiento. Y el conocimiento es al fin entendido no como resultado de acumulación de experiencias o como deducción de principios racionales o ideas innatas, sino como resultado de una experiencia en sí misma racional desde el inicio. Experiencia orgánica que se estructura en forma de sistemas de acciones que, por medio de una lógica material, estructuran nuevos sistemas de acciones más amplios en radio de alcance, más potentes en influjo sobre el medio, más "hábiles" en orden a una adaptación y control sobre el medio. En este sentido, Jean Piaget convirtió en empresa "positiva", científica y experimental, una parte muy importante del proyecto esbozado por Ortega. Piaget llevó a cabo un programa científico de esclarecimiento de los orígenes de la inteligencia y la razón de los sujetos orgánicos partiendo no tanto de un "Yo" que se pone (Fichte) y se limita con el No-Yo (mundo en torno, o "circunstancias") sino de un circuito que ya en la fase pre-intelectual incluye ese centro orgánico que lanza acciones-percepciones, como choca con "dificultades" y "obstáculos" de un entorno con el que deberá luchar. El bebé humano, tanto como cualquier individuo orgánico, es un centro de operaciones y es a la vez el eco y la respuesta de un medio ambiente transformado por las operaciones. Los dos sentidos en los que el sujeto orgánico "choca" con el mundo y lo transforma, a la vez que se transforma él, han recibido por parte de Piaget los nombres de "asimilación" y "acomodación". La asimilación, como proceso que generaliza la asimilación de los alimentos, supone la incorporación cognitiva y no sólo material del mundo. El Yo se "pone", se afirma, incorporando elementos del medio que él necesita para su mantenimiento (conservación, supervivencia). Pero el mundo (el "no-Yo") se le opone, se le enfrenta, le traza caminos por donde poder ejercer la acción y por donde no puede atravesar ese mundo con la acción. La acomodación piagetiana podría verse como el sentido opuesto a las acciones asimilativas. El Yo, como centro orgánico de operaciones, debe transformarse a su vez, debe reestructurar sus esquemas de acción para sortear, horadar, recomponer las barreras y resistencia del mundo-entorno. La razón en el proceso vital no es más que el grado máximo en que un sistema de acciones "se hace con el mundo" y, recíprocamente, el mundo se hace con el yo. Esta es la razón vital, pero investigada desde un punto de vista genético y positivo.

La razón vital no se limita pensar en y desde "el hombre de carne y hueso". La razón vital implica que la vida humana no es sólo razón, pero sí es ejecución de actos en orden a una gestión de la vida misma, una gerencia y construcción que se hace de acuerdo con principios racionales. El hombre no es, para nada, un autómata racional, sino un sujeto orgánico cuya forma humana de adaptación y supervivencia psicobiológica exige la racionalidad. El hombre viene definido, en rigor, no por una sustancial cogitación ("yo soy una cosa que piensa") sino por una actividad circular, por un circuito entre el Yo y las Cosas (el "no-Yo" de Fichte). Ninguno de los polos del circuito debe ser reificado de antemano, ninguno ha de ser tratado acríticamente como una cosa o sustancia. La constitución de los dos polos, yo y mundo ("circunstancias"), consiste precisamente en el lanzamiento de series de acciones en las que el Yo se hace con el Mundo y recíprocamente el Mundo se presenta y re-presenta ante el Yo. La filosofía de Ortega, que tantas veces bebe de la fenomenología y del existencialismo alemán, es vitalista por cuanto que plantea siempre un sujeto humano orgánico definido como un verdadero sistema racional de operatividad, para quien conocer es, de otro modo, coextensivo con sobrevivir y "hacerse con el mundo". Las circunstancias orteguianas, como el "medio" (Umwelt) de los biólogos, conforman el espacio de las operaciones, un espacio que da pie a redefinir la experiencia en términos de construcción. Ortega no quería echar por la borda la razón, aplastarla bajo el peso de una salvaje o bestial Voluntad o Vida. Antes bien, quería explicar el hecho humano mismo de la razón. Al proceder así, al avanzar desde la dialéctica de Fichte, el raciovitalismo del filósofo madrileño ofrece un programa genético del racionalismo tanto como del empirismo. Se trata de volver al genuino espíritu con el que nació el idealismo: la superación de la magna filosofía europea de la Modernidad, tanto el empirismo isleño como el racionalismo continental, una superación que acude a la génesis misma del conocimiento. Y el conocimiento es al fin entendido no como resultado de acumulación de experiencias o como deducción de principios racionales o ideas innatas, sino como resultado de una experiencia en sí misma racional desde el inicio. Experiencia orgánica que se estructura en forma de sistemas de acciones que, por medio de una lógica material, estructuran nuevos sistemas de acciones más amplios en radio de alcance, más potentes en influjo sobre el medio, más "hábiles" en orden a una adaptación y control sobre el medio. En este sentido, Jean Piaget convirtió en empresa "positiva", científica y experimental, una parte muy importante del proyecto esbozado por Ortega. Piaget llevó a cabo un programa científico de esclarecimiento de los orígenes de la inteligencia y la razón de los sujetos orgánicos partiendo no tanto de un "Yo" que se pone (Fichte) y se limita con el No-Yo (mundo en torno, o "circunstancias") sino de un circuito que ya en la fase pre-intelectual incluye ese centro orgánico que lanza acciones-percepciones, como choca con "dificultades" y "obstáculos" de un entorno con el que deberá luchar. El bebé humano, tanto como cualquier individuo orgánico, es un centro de operaciones y es a la vez el eco y la respuesta de un medio ambiente transformado por las operaciones. Los dos sentidos en los que el sujeto orgánico "choca" con el mundo y lo transforma, a la vez que se transforma él, han recibido por parte de Piaget los nombres de "asimilación" y "acomodación". La asimilación, como proceso que generaliza la asimilación de los alimentos, supone la incorporación cognitiva y no sólo material del mundo. El Yo se "pone", se afirma, incorporando elementos del medio que él necesita para su mantenimiento (conservación, supervivencia). Pero el mundo (el "no-Yo") se le opone, se le enfrenta, le traza caminos por donde poder ejercer la acción y por donde no puede atravesar ese mundo con la acción. La acomodación piagetiana podría verse como el sentido opuesto a las acciones asimilativas. El Yo, como centro orgánico de operaciones, debe transformarse a su vez, debe reestructurar sus esquemas de acción para sortear, horadar, recomponer las barreras y resistencia del mundo-entorno. La razón en el proceso vital no es más que el grado máximo en que un sistema de acciones "se hace con el mundo" y, recíprocamente, el mundo se hace con el yo. Esta es la razón vital, pero investigada desde un punto de vista genético y positivo. La incorporación de la filosofía materialista de Gustavo Bueno a todo este enfoque genético-constructivo del pensamiento se hace ineludible en este punto de mi breve recensión. Manuel F. Lorenzo es un buen conocedor del materialismo buenista, como discípulo directo suyo desde los primeros tiempos, miembro activo de la llamada "Escuela de Oviedo", hoy en disolución bajo la sombra de los sectarios y de los arribistas. En "La Razón Manual", el autor nos recuerda el aserto fichteano con que encabezábamos esta reseña: "uno profesa la filosofía que va de acuerdo con la clase de hombre que se es". Profesar el materialismo de Bueno, a pesar de sus deudas para con la epistemología genética piagetiana supone, verdaderamente, profesar una suerte de dogmatismo, de pensamiento antipático a la libertad, dicho en términos fichteanos. Las clases de hombres que, filosóficamente hablando, cabe hallar en el mundo se pueden reducir a dos: los amigos de la libertad (idealismo) y los amigos de la servidumbre (dogmatismo, en donde cabe situar el "materialismo"). "La Razón Manual" es un libro que toma partido expreso y decidido por la libertad, se entronca en el idealismo. No en el idealismo visionario, celeste, construido sobre las nubes. Se entronca en la tradición idealista-vitalista que, desde Fichte, indaga en "el lado activo", esto es, en las operaciones. En ese sentido, la filosofía de Bueno estudiada a la luz de la filosofía de la "Razón Manual" adopta el aspecto de un centauro. Por un lado desarrolla una inmensa y magnífica "Teoría del Cierre Categorial", basada en la obra de Piaget y en una genética de las operaciones gnoseológicas, por otro lado incluye un "preámbulo ontológico" de corte escolástico-marxista, que lastra todo el sistema. El propio nombre de "materialismo filosófico" supone una fuente inagotable de equívocos, que ha dado pie a que muchos farsantes e iletrados lo confundan con una versión sofisticada del leninismo y otros, por el contrario, con un positivismo cientifista o realista. Los grandes logros de Gustavo Bueno, depurados del dogmatismo y su "culto a la materia", se pueden reaprovechar y potenciar siguiendo las indicaciones de "La Razón Manual", todo un programa de investigación que humildemente recomiendo.

La incorporación de la filosofía materialista de Gustavo Bueno a todo este enfoque genético-constructivo del pensamiento se hace ineludible en este punto de mi breve recensión. Manuel F. Lorenzo es un buen conocedor del materialismo buenista, como discípulo directo suyo desde los primeros tiempos, miembro activo de la llamada "Escuela de Oviedo", hoy en disolución bajo la sombra de los sectarios y de los arribistas. En "La Razón Manual", el autor nos recuerda el aserto fichteano con que encabezábamos esta reseña: "uno profesa la filosofía que va de acuerdo con la clase de hombre que se es". Profesar el materialismo de Bueno, a pesar de sus deudas para con la epistemología genética piagetiana supone, verdaderamente, profesar una suerte de dogmatismo, de pensamiento antipático a la libertad, dicho en términos fichteanos. Las clases de hombres que, filosóficamente hablando, cabe hallar en el mundo se pueden reducir a dos: los amigos de la libertad (idealismo) y los amigos de la servidumbre (dogmatismo, en donde cabe situar el "materialismo"). "La Razón Manual" es un libro que toma partido expreso y decidido por la libertad, se entronca en el idealismo. No en el idealismo visionario, celeste, construido sobre las nubes. Se entronca en la tradición idealista-vitalista que, desde Fichte, indaga en "el lado activo", esto es, en las operaciones. En ese sentido, la filosofía de Bueno estudiada a la luz de la filosofía de la "Razón Manual" adopta el aspecto de un centauro. Por un lado desarrolla una inmensa y magnífica "Teoría del Cierre Categorial", basada en la obra de Piaget y en una genética de las operaciones gnoseológicas, por otro lado incluye un "preámbulo ontológico" de corte escolástico-marxista, que lastra todo el sistema. El propio nombre de "materialismo filosófico" supone una fuente inagotable de equívocos, que ha dado pie a que muchos farsantes e iletrados lo confundan con una versión sofisticada del leninismo y otros, por el contrario, con un positivismo cientifista o realista. Los grandes logros de Gustavo Bueno, depurados del dogmatismo y su "culto a la materia", se pueden reaprovechar y potenciar siguiendo las indicaciones de "La Razón Manual", todo un programa de investigación que humildemente recomiendo.

d crib-note interpretation of O’Brien (“zealous Party leader . . . brutally ugly”), but pray consider: a) Connolly was Orwell’s only acquaintance of note who came close to the novel’s description of O’Brien, physically and socially; b) if you bother to read O’Brien’s monologues in the torture clinic, you see he’s doing a kind of Doc Rockwell routine: lots of fast-talking nonsense about power and punishment, signifying nothing.

d crib-note interpretation of O’Brien (“zealous Party leader . . . brutally ugly”), but pray consider: a) Connolly was Orwell’s only acquaintance of note who came close to the novel’s description of O’Brien, physically and socially; b) if you bother to read O’Brien’s monologues in the torture clinic, you see he’s doing a kind of Doc Rockwell routine: lots of fast-talking nonsense about power and punishment, signifying nothing. A good deal of Nineteen Eighty-Four, in fact, is a twisted retelling of Keep the Aspidistra Flying.

A good deal of Nineteen Eighty-Four, in fact, is a twisted retelling of Keep the Aspidistra Flying. To repeat the obvious, Burnham was describing Communism, not some theoretical “totalitarianism,” as in some press blurbs for Nineteen Eighty-Four. As noted, Orwell explicitly disavowed any connection between his fictional “Party” and the Communist one. Nevertheless, the political program that O’Brien boasts about to Winston Smith is the Communist program à la James Burnham. It’s exaggerated and comically histrionic, but strikes the proper febrile tone.

To repeat the obvious, Burnham was describing Communism, not some theoretical “totalitarianism,” as in some press blurbs for Nineteen Eighty-Four. As noted, Orwell explicitly disavowed any connection between his fictional “Party” and the Communist one. Nevertheless, the political program that O’Brien boasts about to Winston Smith is the Communist program à la James Burnham. It’s exaggerated and comically histrionic, but strikes the proper febrile tone. In March 1947, while getting ready to go to Jura and ride the Winston Smith book to the finish even if it killed him (which it did), Orwell wrote his long, penetrating review of The Struggle for the World. He paid some compliments, but also noted some subtle flaws in Burnham’s reasoning. Here he’s talking about Burnham’s willingness to contemplate a preventive war against the USSR:

In March 1947, while getting ready to go to Jura and ride the Winston Smith book to the finish even if it killed him (which it did), Orwell wrote his long, penetrating review of The Struggle for the World. He paid some compliments, but also noted some subtle flaws in Burnham’s reasoning. Here he’s talking about Burnham’s willingness to contemplate a preventive war against the USSR:

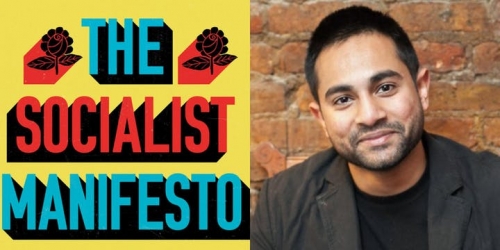

Through most of the book, the arguments are anchored in sturdy common sense, however much one might contest a point or emphasis here and there. On “Third World socialism,” for example, whether in China or Africa or the Americas, Sunkara is right that it turned Marxism on its head, so to speak: “revolutionaries embraced socialism as a path to modernity and national liberation. Adapting a theory that was built around advanced capitalism and an industrial proletariat, they struggled to find ‘substitute proletariats’—from peasants to junior military officers to deprived underclasses—to achieve these ends.” None of it was socialism in the Marxist sense, as coming from the breakdown (literal or not) of capitalism and signifying the liberation of humanity from alienated and exploitative production. It was a “socialism” subordinated to nationalistic ends.

Through most of the book, the arguments are anchored in sturdy common sense, however much one might contest a point or emphasis here and there. On “Third World socialism,” for example, whether in China or Africa or the Americas, Sunkara is right that it turned Marxism on its head, so to speak: “revolutionaries embraced socialism as a path to modernity and national liberation. Adapting a theory that was built around advanced capitalism and an industrial proletariat, they struggled to find ‘substitute proletariats’—from peasants to junior military officers to deprived underclasses—to achieve these ends.” None of it was socialism in the Marxist sense, as coming from the breakdown (literal or not) of capitalism and signifying the liberation of humanity from alienated and exploitative production. It was a “socialism” subordinated to nationalistic ends.

Sommaire :

Sommaire : Aujourd’hui, il publie une plaquette réunissant les pièces du dossier polémique qui opposa Céline à Roger Vailland. Celui qui joua le rôle d’arbitre fut Robert Chamfleury (1900-1972), de son vrai nom Eugène Gohin. Comme chacun sait, il était locataire de l’appartement juste au-dessous de celui de Céline, au quatrième étage du 4 rue Girardon, à Montmartre. Après la guerre, il réfutera Vailland et affirmera que Céline était parfaitement au courant de ses activités de résistant. Au moment critique, Chamfleury lui proposa même un refuge en Bretagne. Dans une version antérieure de Féerie pour une autre fois, Céline le décrit (sous le nom de “Charmoise”) « cordial, compréhensif, conciliant, amical ». Sa personnalité est aujourd’hui mieux connue : parolier et éditeur de musique, Robert Chamfleury était spécialisé dans l’adaptation française de titres espagnols ou hispano-américains. Il fut ainsi une figure marquante de l’introduction en Europe des compositeurs cubains, et des rythmes nouveaux qu’ils apportaient. Il travaillait le plus souvent en duo avec un autre parolier, Henri Lemarchand. Lequel préfaça La Prodigieuse aventure humaine (1951, rééd. 1961) de son ami qui, sur le tard, rédigea plusieurs ouvrages de vulgarisation scientifique et de philosophie des sciences. Céline lui accusa réception avec cordialité de cet ouvrage et l’invita à venir le voir à Meudon. Dans sa plaquette, Andrea Lombardi reproduit la version intégrale de la lettre que Chamfleury adressa au directeur du Crapouillot, telle qu’elle parut, pour la première fois, dans le BC en 1990.

Aujourd’hui, il publie une plaquette réunissant les pièces du dossier polémique qui opposa Céline à Roger Vailland. Celui qui joua le rôle d’arbitre fut Robert Chamfleury (1900-1972), de son vrai nom Eugène Gohin. Comme chacun sait, il était locataire de l’appartement juste au-dessous de celui de Céline, au quatrième étage du 4 rue Girardon, à Montmartre. Après la guerre, il réfutera Vailland et affirmera que Céline était parfaitement au courant de ses activités de résistant. Au moment critique, Chamfleury lui proposa même un refuge en Bretagne. Dans une version antérieure de Féerie pour une autre fois, Céline le décrit (sous le nom de “Charmoise”) « cordial, compréhensif, conciliant, amical ». Sa personnalité est aujourd’hui mieux connue : parolier et éditeur de musique, Robert Chamfleury était spécialisé dans l’adaptation française de titres espagnols ou hispano-américains. Il fut ainsi une figure marquante de l’introduction en Europe des compositeurs cubains, et des rythmes nouveaux qu’ils apportaient. Il travaillait le plus souvent en duo avec un autre parolier, Henri Lemarchand. Lequel préfaça La Prodigieuse aventure humaine (1951, rééd. 1961) de son ami qui, sur le tard, rédigea plusieurs ouvrages de vulgarisation scientifique et de philosophie des sciences. Céline lui accusa réception avec cordialité de cet ouvrage et l’invita à venir le voir à Meudon. Dans sa plaquette, Andrea Lombardi reproduit la version intégrale de la lettre que Chamfleury adressa au directeur du Crapouillot, telle qu’elle parut, pour la première fois, dans le BC en 1990.

Antoine a donc choisi l’obscurité, décevant ainsi son épouse, qui le largue (et cesse de jouer au mécène) et, bientôt, sa fille Blandine, que viendra consoler l’attentionné Thomas. Il vivote dans un HLM de la Grand’Mare (hilarants tableautins du « vivre-ensemble ») et se contente de CDD à la médiathèque Arthur Rainbow (!), l’un des décors du roman – prétexte pour l’auteur à une description aussi comique que glaçante du dispositif d’infantilisation des masses et de leur encadrement « culturel ». Notre bibliothécaire tranche d’avec ses jeunes collègues, acquis à la culture du divertissement et conscients de leur rôle dans le dressage « citoyen » de leurs usagers. Il fera, ô surprise, l’objet d’une dénonciation en règle pour un article littéraire de sa revue consacré à un écrivain qui, dans un français parfait, ose évoquer l’actuel chaos migratoire et ses conséquences sans l’enthousiasme ni la cécité de commande.

Antoine a donc choisi l’obscurité, décevant ainsi son épouse, qui le largue (et cesse de jouer au mécène) et, bientôt, sa fille Blandine, que viendra consoler l’attentionné Thomas. Il vivote dans un HLM de la Grand’Mare (hilarants tableautins du « vivre-ensemble ») et se contente de CDD à la médiathèque Arthur Rainbow (!), l’un des décors du roman – prétexte pour l’auteur à une description aussi comique que glaçante du dispositif d’infantilisation des masses et de leur encadrement « culturel ». Notre bibliothécaire tranche d’avec ses jeunes collègues, acquis à la culture du divertissement et conscients de leur rôle dans le dressage « citoyen » de leurs usagers. Il fera, ô surprise, l’objet d’une dénonciation en règle pour un article littéraire de sa revue consacré à un écrivain qui, dans un français parfait, ose évoquer l’actuel chaos migratoire et ses conséquences sans l’enthousiasme ni la cécité de commande.

3) Tale conoscenza non è sapere se non è innanzitutto uno stato dell’essere; lo stato dell’essere è vedere l’Invisibile, che è l’Indicibile, ma per colui che è Essere non è che l’Uno, l’Istante che è fuori dal tempo: colui che vive nella dimensione dello Spirito è nel tempo pur essendo, nella radice, fuori dal tempo, vedrà il Divenire che è Essere, come indica l’enigmatico sorriso dell’Apollo di Veio, Egli, sorridendo della nostra stupidità, accenna, svela e rivela la Verità: l’Assoluto, il Divino è semplicemente ciò che tu vedi e che sei! Tu però non lo sai!

3) Tale conoscenza non è sapere se non è innanzitutto uno stato dell’essere; lo stato dell’essere è vedere l’Invisibile, che è l’Indicibile, ma per colui che è Essere non è che l’Uno, l’Istante che è fuori dal tempo: colui che vive nella dimensione dello Spirito è nel tempo pur essendo, nella radice, fuori dal tempo, vedrà il Divenire che è Essere, come indica l’enigmatico sorriso dell’Apollo di Veio, Egli, sorridendo della nostra stupidità, accenna, svela e rivela la Verità: l’Assoluto, il Divino è semplicemente ciò che tu vedi e che sei! Tu però non lo sai! Si conosce solo ciò che si è e si è solo ciò che si conosce. Gli Dei non esistono a priori (per fede) ma esistono solo se si conoscono e si conoscono solo se si esperimentano, quindi esistono solo per colui il quale li esperimenta, cioè li vive e quindi li conosce; nel senso che, pur esistendo da sempre, per colui il quale non li conosce Essi non esistono. Tale è il significato della frase: “I Greci non credevano negli Dei; poiché li vedevano!”

Si conosce solo ciò che si è e si è solo ciò che si conosce. Gli Dei non esistono a priori (per fede) ma esistono solo se si conoscono e si conoscono solo se si esperimentano, quindi esistono solo per colui il quale li esperimenta, cioè li vive e quindi li conosce; nel senso che, pur esistendo da sempre, per colui il quale non li conosce Essi non esistono. Tale è il significato della frase: “I Greci non credevano negli Dei; poiché li vedevano!”

Nel corpo della cultura europea scorre sangue «pagano». A muovere dal Settecento, filosofi, storici delle religioni e artisti, si sono prodigati nel tentativo di far riemergere le sorgenti più arcaiche della nostra cultura, richiamando l’attenzione sul suo effettivo ubi consistam. Anzi, questo sforzo è ancora in corso: si pensi, tra i tanti esempi che si possono fare in tema, alla valorizzazione del mondo pre-cristiano, presentata, nella propria opera, da Evola o, più recentemente, da autori quali Marc Augé e Alain de Benoist. Un ruolo rilevante, in tal senso, nel secondo decennio del «secolo breve», lo ha svolto il filologo svevo e storico delle religioni, Walter Friedrich Otto. Il suo lavoro più noto, Gli Dei della Grecia, fu in qualche modo preparato da un libro che egli pubblicò nel 1923, Spirito classico e mondo cristiano, di cui è recentemente apparsa la seconda edizione italiana, per i tipi de L’arco e la Corte (per ordini: arcoelacorte@libero.it, pp. 174, euro 15,00). Si tratta, come ricorda Giovanni Monastra, nell’informata e stimolante Prefazione, di un testo nel quale l’autore mostrò, in tutta la sua forza e con invidiabile spessore erudito, l’attrazione empatica per il mondo classico e, in particolare, per la religiosità ellenica.

Nel corpo della cultura europea scorre sangue «pagano». A muovere dal Settecento, filosofi, storici delle religioni e artisti, si sono prodigati nel tentativo di far riemergere le sorgenti più arcaiche della nostra cultura, richiamando l’attenzione sul suo effettivo ubi consistam. Anzi, questo sforzo è ancora in corso: si pensi, tra i tanti esempi che si possono fare in tema, alla valorizzazione del mondo pre-cristiano, presentata, nella propria opera, da Evola o, più recentemente, da autori quali Marc Augé e Alain de Benoist. Un ruolo rilevante, in tal senso, nel secondo decennio del «secolo breve», lo ha svolto il filologo svevo e storico delle religioni, Walter Friedrich Otto. Il suo lavoro più noto, Gli Dei della Grecia, fu in qualche modo preparato da un libro che egli pubblicò nel 1923, Spirito classico e mondo cristiano, di cui è recentemente apparsa la seconda edizione italiana, per i tipi de L’arco e la Corte (per ordini: arcoelacorte@libero.it, pp. 174, euro 15,00). Si tratta, come ricorda Giovanni Monastra, nell’informata e stimolante Prefazione, di un testo nel quale l’autore mostrò, in tutta la sua forza e con invidiabile spessore erudito, l’attrazione empatica per il mondo classico e, in particolare, per la religiosità ellenica.  In Spirito classico e mondo cristiano, sono presenti: «lampeggianti intuizioni e utili indicazioni che consentono di vedere con occhi nuovi il mondo religioso ellenico» (p. 13). Otto cerca, in ogni modo, di far parlare i Greci e i loro dei, con la voce che gli fu propria. Fino ad allora, infatti, il clamore millenario prodotto dalla cultura dei vincitori, nella contesa storica sviluppatasi nel IV secolo d.c., quella cristiana, aveva impedito di cogliere il senso ultimo della visione del mondo ellenica. La critica al cristianesimo di Otto è radicale, i toni polemici decisamente aspri, in alcuni passaggi rasentano l’invettiva. Per questo, successivamente, il filologo non si riconobbe del tutto in tali affermazioni e non volle che questo studio fosse nuovamente pubblicato (la precedente edizione italiana uscì nel 1973, ad insaputa della figlia dello studioso). Il libro è scritto sotto il segno di Nietzsche. Come il filosofo dell’eterno ritorno, anche Otto distinse l’originario insegnamento del Cristo, insieme a Socrate considerato ultimo esempio di vita persuasa, dalla successiva dottrina cristiana, esito del travisamento teologico operato dalla tradizione paolino-agostiniana. In ogni caso, quale idea ha Otto della religio greca?

In Spirito classico e mondo cristiano, sono presenti: «lampeggianti intuizioni e utili indicazioni che consentono di vedere con occhi nuovi il mondo religioso ellenico» (p. 13). Otto cerca, in ogni modo, di far parlare i Greci e i loro dei, con la voce che gli fu propria. Fino ad allora, infatti, il clamore millenario prodotto dalla cultura dei vincitori, nella contesa storica sviluppatasi nel IV secolo d.c., quella cristiana, aveva impedito di cogliere il senso ultimo della visione del mondo ellenica. La critica al cristianesimo di Otto è radicale, i toni polemici decisamente aspri, in alcuni passaggi rasentano l’invettiva. Per questo, successivamente, il filologo non si riconobbe del tutto in tali affermazioni e non volle che questo studio fosse nuovamente pubblicato (la precedente edizione italiana uscì nel 1973, ad insaputa della figlia dello studioso). Il libro è scritto sotto il segno di Nietzsche. Come il filosofo dell’eterno ritorno, anche Otto distinse l’originario insegnamento del Cristo, insieme a Socrate considerato ultimo esempio di vita persuasa, dalla successiva dottrina cristiana, esito del travisamento teologico operato dalla tradizione paolino-agostiniana. In ogni caso, quale idea ha Otto della religio greca? I Greci, al contrario, non conobbero mai la fides, la loro religio della forma era, in realtà, un susseguirsi di esperienze, di realizzazioni del sacro, da parte dell’uomo. Il tratto politeista consentiva loro di apprezzare i diversi volti dell’Uno e di viverli, di farne esperienza. A ciò contribuivano il mito e il culto. Nel secondo: «è l’uomo che si innalza al Divino, vive e agisce in comunione con gli dei; nel mito è il divino che scende e si fa umano» (p. 21). Il rapporto uomo-dio si manifestava, come rilevato da Rudolf Otto, nell’endiadi Io-Esso. Si trattava, pertanto, di una relazione centrata sull’ethos, sul modo d’essere (Evola avrebbe detto “razza dello spirito”) e non sul pathos, sulla dimensione emotiva e sentimentale. Il trionfo del cristianesimo rese esplicito che il mondo antico aveva perso la propria anima, vale a dire quest’atteggiamento paritetico degli uomini nei confronti degli dei. Ecco perché alla «buona novella» aderirono gli ultimi, i diseredati e le donne, che divennero strumenti mortiferi per lo spirito classico. In quel frangente, pochi tentarono una resistenza. Si ersero in pochi, ricorda Otto, sulle rovine di un mondo al tramonto per proclamarne la grandezza, tra essi Giuliano Imperatore. Monastra ipotizza, e la cosa va segnalata, che Evola, avrebbe potuto trarre il titolo del suo, Gli uomini e le rovine, proprio da un passo del libro del filologo tedesco, che certamente lesse.