Jouissant aujourd’hui d’une paisible retraite, l’anthropologue, historien et sociologue Emmanuel Todd passe pour un franc-tireur dans l’univers béat de l’enseignement dit supérieur français. Ses analyses sur les structures anthropologiques des formes familiales suscitent toujours de vives controverses, mais ce sont ses essais politiques qui en font une personnalité publique.

Opposant résolu au traité de Maastricht en 1992, Emmanuel Todd n’a jamais hésité à rédiger des ouvrages incisifs tels que L’Illusion économique (1998), Après l’empire (2002), Après la démocratie (2008) ou Qui est Charlie ? (2015). Placé sous le patronage de Karl Marx qui « a dit beaucoup de bêtises, mais Marx était un esprit libre, il était capable de regarder la société de son temps avec ironie et cruauté. Il est le remède contre le panglossisme, c’est-à-dire cette propension à croire que tout va pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles (p. 19) », Les Luttes de classes en France au XXIe siècle ne déroge pas aux prédispositions politique de son auteur, républicain souverainiste – nationiste de gauche. « Ayant vécu Mai 68 à l’âge de 17 ans, à une époque où j’étais membre des Jeunesses communistes (p. 276) », il avoue avoir voté en 2017 « héroïquement (p. 250) » pour Jean-Luc Mélenchon avant de s’abstenir au second tour. Il assume aussi un « républicanisme national-cosmopolite ». Par exemple, « j’ai toujours été, me semble-t-il, et je reste, un immigrationniste raisonnable (p. 270) ». Il ajoute que « trois de mes petits-enfants ont un père d’origine algérienne. […] Je trouve mon propre “ remplacement ” par ces petits Français-là merveilleux (p. 267) ».

Opposant résolu au traité de Maastricht en 1992, Emmanuel Todd n’a jamais hésité à rédiger des ouvrages incisifs tels que L’Illusion économique (1998), Après l’empire (2002), Après la démocratie (2008) ou Qui est Charlie ? (2015). Placé sous le patronage de Karl Marx qui « a dit beaucoup de bêtises, mais Marx était un esprit libre, il était capable de regarder la société de son temps avec ironie et cruauté. Il est le remède contre le panglossisme, c’est-à-dire cette propension à croire que tout va pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles (p. 19) », Les Luttes de classes en France au XXIe siècle ne déroge pas aux prédispositions politique de son auteur, républicain souverainiste – nationiste de gauche. « Ayant vécu Mai 68 à l’âge de 17 ans, à une époque où j’étais membre des Jeunesses communistes (p. 276) », il avoue avoir voté en 2017 « héroïquement (p. 250) » pour Jean-Luc Mélenchon avant de s’abstenir au second tour. Il assume aussi un « républicanisme national-cosmopolite ». Par exemple, « j’ai toujours été, me semble-t-il, et je reste, un immigrationniste raisonnable (p. 270) ». Il ajoute que « trois de mes petits-enfants ont un père d’origine algérienne. […] Je trouve mon propre “ remplacement ” par ces petits Français-là merveilleux (p. 267) ».

Exaspéré par la politicaillerie hexagonale, il déplore que « le but fondamental du système politique français est d’organiser des pièces de théâtre successives qui doivent masquer l’absence de pouvoir économique réel du président (p. 226) ». La révolte automnale des Gilets jaunes l’enthousiasme, malgré son refus du RIC (référendum d’initiative citoyenne). Il y voit la fin d’une phase historique commencée en 1968. « Le cycle qui s’ouvre avec les Gilets jaunes correspond au début de la baisse du niveau de vie et il marque le retour de la lutte des classes (p. 278) », d’où sa référence au livre de Marx, Les Luttes de classes en France, publié en 1850.

Une marginalité permise

À travers le phénomène politico-social des « Gilets jaunes », Emmanuel Todd s’attend au rejet impétueux des dogmes financiaristes de ses bêtes noires, les traités européens. N’évoque-t-il pas « le péché originel : Maastricht (p. 167) » ? Certes, il ne pouvait pas prévoir le surgissement imprévu du coronavirus qui ruinerait les critères maastrichtiens plus sûrement que mille manifestations et cinq mille émeutes. Il prévient néanmoins que « ce livre n’est nullement écrit “ contre l’euro ”. En tant que militant opposé à la monnaie unique, je me considère comme un vaincu de l’histoire (pp. 17 – 18) ». La crise sociale de novembre 2018 au printemps 2019 contredit ce qu’il pensait jusque-là, à savoir qu’« à l’heure actuelle, la défaite se manifeste, pour les classes populaires, par une baisse du niveau de vie et une disparition de toute capacité à influer sur la décision politique. Nous courons, depuis le milieu des années 1980, de micro-défaites en micro-défaites (p. 119) ».

Emmanuel Todd ne retient jamais ses coups à l’égard des puissants et des importants. « Depuis vingt ans, écrit-il avec une certaine auto-dérision, je me suis fait une spécialité d’insulter nos présidents. J’ai eu l’occasion de traiter Chirac de “ crétin ” sur France Inter, Sarkozy de “ machin ” sur France 3, Hollande de “ nain ” dans Marianne (je ne suis plus très sûr) (p. 234) ». Il étrille donc Emmanuel Macron, « candidat surprise du Néant (p. 250) ». Son bouquin-programme, « Révolution est un robinet d’eau tiède, parfois distrayant par l’inculture historique qui s’y déploie (p. 230) ». « En le lisant, j’ai eu confirmation de ma première impression : 265 pages (gros caractère) de vide (p. 228). » L’auteur partage l’opinion de Michel Drac qui, lors d’une recension sur sa chaîne YouTube du 8 février 2017, en déplorait déjà la vacuité.

On décèle parfois dans les démonstrations de Luttes de classes en France au XXIe siècle des fortes prégnances anarchistes. Si, pour lui, « au tribunal de l’histoire, Mitterrand pourrait […] plaider une sorte d’irresponsabilité intellectuelle (p. 177) » pour cause d’« européïte » aiguë, le second François présidentiel en prend pour son grade. En 2012, face à un « hyper-président » déconsidéré, Hollande « s’offre en Prozac institutionnel (p. 192) » à ses compatriotes si bien que par ses circonvolutions incessantes, « son quinquennat peut se résumer en un mot, c’est celui de lâcheté (p. 194) ». Son propos est ainsi notoirement « dégagiste », sinon « populiste ». « Avec les rêves néo-libéraux de Macron, dignes des années 1980, les fantasmes ethniques de Le Pen, l’auto-hallucination de Fillon en incarnation de la droiture, l’insoumission de Mélenchon qui veut sortir du capitalisme mais pas de l’euro, la France a véritablement atteint le degré zéro du sérieux politique (p. 249). » Pis, « sous Macron, l’histoire politique reste une comédie (p. 223) ».

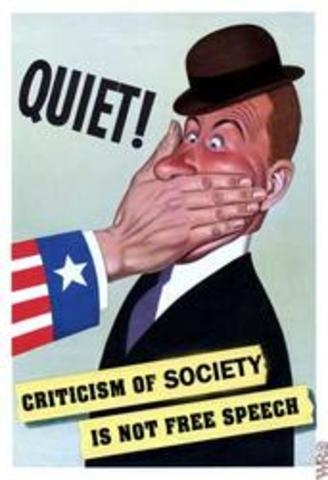

Il s’attaque volontiers aux journalistes et plus particulièrement aux médiacrates. Avec le « Grand Débat » post-Gilets jaunes, « l’information continue devenait bourrage de crâne continue (p. 310) ». Il note qu’« à l’âge d’Internet, les journalistes constituent un groupe menacé de disparition et donc extrêmement vulnérable. Ils ont beau appartenir à la catégorie des cadres et professions intellectuelles supérieures, ils se retrouvent dans la même situation de dominés que les ouvriers de l’industrie : ils n’ont aucune capacité de négociation et doivent donc, sans que les choses soient explicitement dites, obéir. Ou être virés (p. 30) ». Cela confirme ce qu’avance depuis des années le dissident persécuté Alain Soral : les journalistes sont soit des « putes », soit des « chômeurs »… Emmanuel Todd oublie peut-être qu’en France, depuis Théophraste Renaudot et sa Gazette de France (1631) soutenus par des subsides du cardinal de Richelieu, la presse sert le régime en place.

Une autre identité française…

D’après l’auteur, « l’histoire, n’en déplaise aux élitistes et aux complotistes, faces complémentaires d’une même incompréhension, est faite par des masses, aisées, pauvres ou médiocres (p. 31) ». C’est un jugement quelque peu péremptoire de sa part. Il se félicite du phénomène tumultueux (ou chamailleur ?) des Gilets jaunes. Puisqu’il annonce que « les luttes de classes, c’est la France. Marx a certes étendu le concept à l’échelle planétaire, mais il ne faisait aucun doute pour lui que le lieu de naissance des luttes de classes modernes, c’était la France. Beaucoup plus que la chasse aux Arabes ou aux homosexuels, la lutte des classes est notre identité (p. 20) », il estime que « les Gilets jaunes ont, eux, été capables, un court moment, d’unifier la société française, de la rassembler, à l’inverse du “ Rassemblement ” national (p. 282) ». Les Gilets jaunes seraient par conséquent un nouveau facteur « unificateur » des strates sociales françaises en ce premier quart du XXIe siècle. Au siècle précédent, il a le toupet d’écrire que « nous avons eu la “ chance ” de faire la Grande Guerre qui, en envoyant les Vendéens massacrer les Allemands, et se faire massacrer par eux, les a réconciliés avec la nation (pp. 107 – 108) ». Emmanuel Todd valide l’entière responsabilité de la funeste « Union sacrée » dans le « populicide » des campagnes françaises. Il aurait été préférable que Vendéens et Allemands se coalisent au nom de Dieu, de la hiérarchie, de l’autorité et des communautés charnelles contre une République française individualiste mortifère. Un certain nationalisme français porte aussi une lourde responsabilité dans la « victoire » de 1918 qui montre, un siècle plus tard, sa sanglante inutilité.

En homme de gauche, Emmanuel Todd dénigre bien sûr le parti de Marine Le Pen. Arc-bouté sur la décennie 1980, il réduit le vote « lepéniste » à « un sentiment anti-arabe (p. 259) ». Le « fonds de commerce [du FN/RN] est l’hostilité aux immigrés d’origine maghrébine, la haine ethnique. Mais, je puis vous l’assurer, s’opposer au lepénisme ne fait pas de vous un héros de la liberté et de l’égalité si vous avez, par ailleurs, privé le citoyen français de son droit de vote effectif, c’est-à-dire qui puisse servir à quelque chose. Tout au plus pouvez-vous vous présenter comme un oligarque libéral anti-raciste (p. 182) ». A-t-il oublié que le Front national de Jean-Marie Le Pen a toujours défendu, face à l’atlantisme, des États arabes comme l’Irak baasiste, la Libye kaddhafiste ou la Syrie nationale-populaire ? Plus sérieusement, il considère que « l’installation permanente du Front national dans le système politique français offre […] à nos classes dirigeantes une nouvelle fausse virginité démocratique. Occupées à détruire la démocratie en pratique, elles peuvent quand même désormais parler sans cesse de la défendre contre Satan (p. 181) ». Par de savantes analyses statistiques, il énonce une nouvelle fois que l’électorat frontiste se droitise (!) en attirant vers lui retraités et petits commerçants. Mieux, « le Rassemblement national est devenu le parti dominant d’un groupe social qui disparaît. […] L’échec du RN est programmé par son succès prolétarien (p. 344) ». Bref, « les chances du FN d’arriver au pouvoir sont nulles et elles ne risquent pas d’augmenter puisque, justement, sa base électorale principale, le monde ouvrier, est en contraction rapide (p. 258) ».

Tout en regrettant que La France Insoumise n’ait pas négocié ce fameux tournant populiste et souverainiste au lieu de revenir « vers la petite gauche PS (p. 326) », il affirme que « le vote Vert est un vote d’attente, un vote faute de mieux pour l’instant. Une pause, un refuge provisoire pour des électeurs au moi fatigué (p. 328) ». Les élections européennes de 2019 prouvent que l’électorat de Yannick Jadot demeure « un électorat “ bobo ” classique (p. 327) », que c’est un « vote […] : “ Ni Macron ni le peuple ” (p. 327) » qui traduit surtout « un vote contre le Jaune. Non à Macron, non aux Gilets jaunes aussi. Un vote “ ni ni ”, en somme (p. 328) ». S’agit-il d’un nouveau symptôme du pourrissement continu du microcosme politique et donc de la France ? Pas du tout ! « Les modèles de segmentation qui s’efforcent de mettre en évidence la séparation de groupes entraînés par des mœurs, des valeurs ou des destins économiques différents – la fracture territoriale de Christophe Guilluy, l’archipellisation de Jérôme Fourquet, les clivages générationnels de Louis Chauvel – se dirigent vers l’obsolescence. La vérité ultime du moment est sans doute que la société française n’a jamais été aussi homogène dans son atomisation et ses chutes. Avec, au sommet, une caste de vrais riches (pp. 152 – 153). »

Emmanuel Todd remet en cause sa propre théorie anthropologique familiale qui expliquait la complexe diversité française. « Le chercheur, et particulièrement le vieux chercheur, finit par se trouver prisonnier de ses propres modèles et conceptions (pp. 12 – 13). » Or, le « principe d’empirisme […] a guidé toute ma vie de chercheur (p. 66) ». Il entérine la fin de « la polarité entre les valeurs libérales – égalitaires du centre et les valeurs autoritaires inégalitaires de la périphérie (p. 100) ». Maints essayistes, historiens, sociologues, économistes, démographes se sont disputés à propos d’une époque précise de l’unification des territoires français. L’auteur assure que cette intégration unificatrice s’est achevée au cours du cycle 1968 – 2017. Si sa thèse se révèle juste, elle confirmerait notre approche gallovacantiste qui postule l’absorption et donc l’effacement de la France par la République hexagonale.

Achèvement de la France ?

Par-delà les graphiques, les pourcentages et le savant calcul de coefficients, l’auteur ne voit pas que le fort taux de mariages mixtes en France s’explique par l’union au bled des filles d’immigrés d’origine musulmane avec des maris du coin. Il se rit de la « querelle » lancée par Éric Zemmour sur les prénoms non français. « Si s’appeler Mustapha, Kader ou Yasmina signifie que l’on n’est pas un vrai Français, alors, avec près de 20 % de faux Français parmi ses naissances, la France n’existe déjà plus (p. 364). » Eh oui ! Todd serait-il un francovacantiste qui s’ignore ? Bien sûr, le « Grand Remplacement » n’existe pas à ses yeux, quoique… « Nos idéologues, à l’image de beaucoup d’électeurs du Front national, continuent d’être obsédés par les Arabes sans voir qu’une immigration noire africaine massive est en train de changer le pays de couleur et que le nombre de mariages mixtes, surtout si l’on tient compte du caractère récent de cette immigration, est déjà étonnamment élevé (p. 108). » L’africanisation de l’Hexagone avance à un rythme soutenu. L’auteur passe bien entendu sous silence les méfaits calamiteux de cette vague migratoire. Pourtant, « avec ses escalators en panne, ses accidents de train à répétition, ses usines et cathédrales qui flambent, la France, où la pauvreté est devenue un motif d’angoisse générale, me semble moins évoquer un pays sur la pente ascendante qu’une société en voie de re-sous-développement (p. 45) ».

Emmanuel Todd évoque l’euro pour expliquer cette effroyable descente économique et sociale. Il s’inquiète de la baisse évidente de la natalité sans viser les politiques familiales néfastes de « Sarkollande ». À rebours des études de l’INSEE qui « ne calcule plus que le produit intérieur brut (PIB) et a abandonné le concept de produit national brut (PNB) qui permet, lui, de distinguer l’activité des entreprises sur le territoire national, selon leur nationalité, et l’activité des firmes françaises à l’étranger (p. 36) », il insiste sur « la baisse du niveau de vie (p. 34) ». Pourquoi ? « Dans ce monde en régression, qui se concentre sur les services, le chômage peut effectivement régresser lui aussi. Seulement, parce que la richesse réelle d’une population dépend de ses exportations industrielles, les emplois nouvellement créés sont inférieurs à ceux qui ont été détruits : ils requièrent un niveau de qualification plus bas et offrent un niveau de vie plus bas également. Ce vers quoi nous sommes peut-être en train de tendre, c’est en somme une société “ serviciée ” (comme on parle de société “ ruralisée ”) (pp. 58 – 59). »

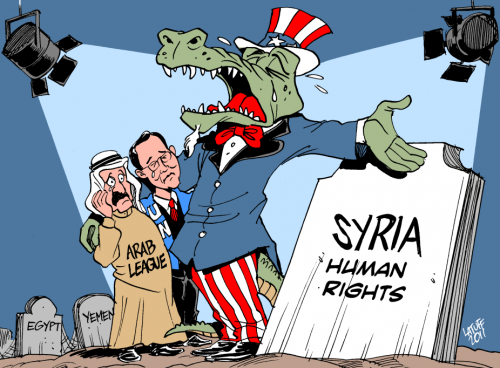

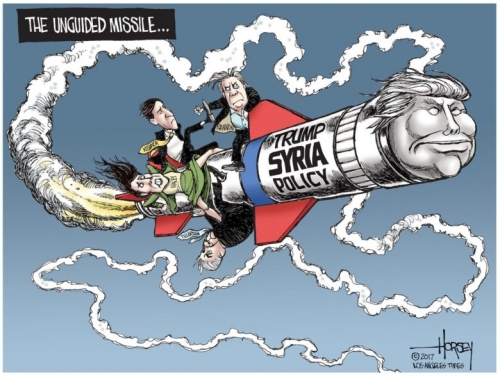

Plus que l’euro, c’est la mondialisation provoque ce déclin. Mais Todd se focalise sur la monnaie unique européenne. « À partir de 1999 [année du lancement de l’euro en tant que monnaie de compte effective] la démocratie représentative, au sens classique et conventionnel du terme, a cessé d’exister en France (p. 182). » Ce lecteur de l’historien royaliste, libéral et germanophobe Jacques Bainville n’aime pas l’Europe. Avec toute l’autorité universitaire qui lui est due, « en tant qu’anthropologue, je sais que les Européens n’existent pas (p. 203) ». Première nouvelle ! Et le Français existe-t-il vraiment en 2020 ? Il reconnaît que « l’euro, monnaie créée pour des raisons politiques et géopolitiques, est en lui-même intensément “ étatique ” (p. 345) », ce qui explique son approbation du Traité constitutionnel européen au référendum de 2005. Il souligne que « l’euro contient […] en lui-même l’idée d’un État si puissant qu’il peut s’opposer aux forces du marché (p. 346) ». Quelle belle perspective anti-libérale ! Emmanuel Todd ne semble pas savoir que les promoteurs initiaux du projet dit européen, en premier lieu les États-Unis, refusent l’émergence sur la scène mondiale d’une nouvelle grande puissance associant la dissuasion nucléaire française, la force monétaire allemande, le dynamisme industriel italien et l’influence géo-linguistique espagnole, qui s’adosserait à la Russie et à l’Eurasie.

Il préfère accuser les enseignants d’européisme anti-national. « À travers les professeurs d’histoire, ils inculquent depuis des décennies l’idée d’un horizon européiste indépassable et ont ainsi contribué à ancrer dans de jeunes esprits une idéologie (objectivement) de droite (p. 239). » Il ignore peut-être que ce monde enseignant, longtemps socle principal du PS, applique des programmes scolaires acceptés par les ministres de l’« Éducation nationale ». L’auteur serait-il favorable à la réintroduction de Vercingétorix, de Clovis, de Louis XIV et de Napoléon ? Pas certain… Il se contredit aussi puisqu’on lit que « l’européisme le plus dense, le plus anti-national, fut socialiste. La droite n’a fait que suivre (p. 224) ». Loin d’inculquer aux adolescents une supposée idéologie de droite, écoles, collèges et lycées déversent chaque jour un « sociétalisme culturel » caractérisé par l’« ouverture obligatoire à l’Autre » (n’est-ce pas, les filles ?) et le consentement forcé au terrorisme psychologique du sectarisme queer.

Phobie allemande

Écartant sans aucune raison valable Italiens et Espagnols de son raisonnement historique, Emmanuel Todd assure que « les Français du XXIe siècle se situent principalement par rapport à deux peuples très proches physiquement : les Allemands, vis-à-vis desquels ils souffrent d’un complexe d’infériorité, et les Arabes, vis-à-vis desquels ils souffrent d’un complexe de supériorité. Il y a une dialectique Allemands – Arabes inconsciente dans la mentalité française, fortement associée à la problématique générale de l’inégalité. Une France obsédée par les Allemands le sera aussi par les Arabes. Et vice versa (p. 189) ». Les Arabes ou les Maghrébins ? Monsieur l’Anthropologue ne sait-il pas que l’Afrique du Nord est toujours berbère et non massivement arabe ? On sait tous de nos jours que ce sont les mots allemands, plus qu’arabes d’ailleurs, qui envahissent le langage courant et que les cinémas ne diffusent que des productions d’outre-Rhin au titre germanique non traduit… Cette explication psychologique simpliste et sommaire ne masque pas une germanophobie tenace.

En écrivant que « les élites allemandes souffrent plutôt d’un complexe d’infériorité vis-à-vis de l’Angleterre, depuis Guillaume II au moins. Elles ont beaucoup rêvé d’un “ couple ” anglo-allemand présidant aux destinées de la planète (note 1 p. 190) », Todd ignore peut-être que l’actuelle dynastie régnante de Buckingham Palace vient du Hanovre et que Guillaume II d’Allemagne cousine avec le père de Georges V d’Angleterre, Édouard VII. Entre 1945 et 1949, les Britanniques occupèrent le Nord-Ouest de la future RFA. La rééducation mentale collective entreprise par les Occidentaux a produit des institutions allemandes vassales de l’atlantisme, des États-Unis, de la City et de Wall Street. Guy Mettan rapporte une « révélation de l’ancien patron du contre-espionnage militaire allemand, le général Gerd-Helmut Komossa, suivant laquelle les chanceliers allemands, depuis la mise en place de la Loi fondamentale créant la République fédérale en 1949, doivent faire acte d’allégeance aux trois anciennes puissances occupantes de 1945 (1) ». Il cite ensuite un ancien collaborateur du chancelier social-démocrate Willy Brandt, Egon Bahr, expliquant qu’« on avait soumis au chancelier fraîchement élu Willy Brandt trois lettres à signer pour les ambassadeurs des puissances occidentales. Avec sa signature, il devait confirmer son accord aux restrictions légales exprimées par les gouverneurs militaires alliés à propos de l’application de la Loi fondamentale du 12 mai 1949 (2) ». Cette soumission perdure-t-elle depuis la réunification de 1990 ? D’une manière indirecte, très certainement. Il ne fait en outre guère de doute qu’Angela Merkel se trouve tenue par les services occidentaux. Son père, le pasteur Horst Kasner, a quitté Hambourg en 1954 pour la RDA. Avant la chute du Mur, la jeune Angela participait à la Jeunesse libre allemande et fut secrétaire à l’Académie des sciences du Département pour l’agitation et la propagande. Or, le journaliste et ancien agent de renseignement Pierre de Villemarest signale que la Jeunesse libre allemande servait souvent d’antichambre aux futurs cadres du Parti et de la Stasi sous la supervision directe du KGB soviétique (3). Il n’est pas non plus anodin d’apprendre qu’une fois la réunification acquise, la mère d’Angela Merkel adhéra au SPD et que son propre frère milita chez les Verts. Imbu de certitudes et sans connaître les coulisses de l’actualité, Emmanuel Todd se trompe sur un projet pseudo-européen qui ne tend pas vers un hypothétique IVe Reich, mais plutôt vers un condominium américain germano-atlantiste sur l’Europe.

En écrivant que « les élites allemandes souffrent plutôt d’un complexe d’infériorité vis-à-vis de l’Angleterre, depuis Guillaume II au moins. Elles ont beaucoup rêvé d’un “ couple ” anglo-allemand présidant aux destinées de la planète (note 1 p. 190) », Todd ignore peut-être que l’actuelle dynastie régnante de Buckingham Palace vient du Hanovre et que Guillaume II d’Allemagne cousine avec le père de Georges V d’Angleterre, Édouard VII. Entre 1945 et 1949, les Britanniques occupèrent le Nord-Ouest de la future RFA. La rééducation mentale collective entreprise par les Occidentaux a produit des institutions allemandes vassales de l’atlantisme, des États-Unis, de la City et de Wall Street. Guy Mettan rapporte une « révélation de l’ancien patron du contre-espionnage militaire allemand, le général Gerd-Helmut Komossa, suivant laquelle les chanceliers allemands, depuis la mise en place de la Loi fondamentale créant la République fédérale en 1949, doivent faire acte d’allégeance aux trois anciennes puissances occupantes de 1945 (1) ». Il cite ensuite un ancien collaborateur du chancelier social-démocrate Willy Brandt, Egon Bahr, expliquant qu’« on avait soumis au chancelier fraîchement élu Willy Brandt trois lettres à signer pour les ambassadeurs des puissances occidentales. Avec sa signature, il devait confirmer son accord aux restrictions légales exprimées par les gouverneurs militaires alliés à propos de l’application de la Loi fondamentale du 12 mai 1949 (2) ». Cette soumission perdure-t-elle depuis la réunification de 1990 ? D’une manière indirecte, très certainement. Il ne fait en outre guère de doute qu’Angela Merkel se trouve tenue par les services occidentaux. Son père, le pasteur Horst Kasner, a quitté Hambourg en 1954 pour la RDA. Avant la chute du Mur, la jeune Angela participait à la Jeunesse libre allemande et fut secrétaire à l’Académie des sciences du Département pour l’agitation et la propagande. Or, le journaliste et ancien agent de renseignement Pierre de Villemarest signale que la Jeunesse libre allemande servait souvent d’antichambre aux futurs cadres du Parti et de la Stasi sous la supervision directe du KGB soviétique (3). Il n’est pas non plus anodin d’apprendre qu’une fois la réunification acquise, la mère d’Angela Merkel adhéra au SPD et que son propre frère milita chez les Verts. Imbu de certitudes et sans connaître les coulisses de l’actualité, Emmanuel Todd se trompe sur un projet pseudo-européen qui ne tend pas vers un hypothétique IVe Reich, mais plutôt vers un condominium américain germano-atlantiste sur l’Europe.

En marxien hétérodoxe, il proclame : « Pas de nation sans lutte des classes (p. 363). » Avant de faire de la France paupérisée une nouvelle patrie prolétaire prête à se dresser contre les « États nantis », il espère beaucoup dans le mouvement des Gilets jaunes. Il y devine une expression de l’unité nationale. « En tant qu’historien de la longue durée et contre les théoriciens de la fragmentation de la société française, je suis prêt à parier que les mutilations et les incarcérations de Français ordinaires mal payés – employés, caristes, chauffeurs routiers, électeurs ou non du Rassemblement national ou parfois de Mélenchon, venant ou non de provinces de l’Ouest où il n’y a pas de problème d’immigration [!] – ont amorcé une réunification de la société française dans ses masses populaires (p. 302). » En se penchant sur le profil des « meneurs » de la fronde jaune, il en déduit une dissociation croissante de l’intelligence et de l’instruction transmise par l’école. Les classes populaires deviendraient-elles moins diplômées et plus intelligentes ? En effet, « comment expliquer que de plus en plus d’enfants obtiennent le bac au sein de générations qui savent de moins en moins écrire et compter ? (p. 65) » Par la haine programmée de la transmission des connaissances de la culture classique européenne et française. Aujourd’hui, les facultés, en particulier en sciences humaines et en psychologie, sont peuplées de sots qui ne le savent pas, à qui on fait miroiter un avenir merveilleux et qu’on manipule par des injonctions impérieuses de la « pensée » inclusive. La responsabilité de tous les présidents depuis Giscard d’Estaing est en cause, même si avant 1995, « le bac général restait le bac, il n’était pas dévalué par rapport à celui qu’avaient pu passer les générations antérieures. […] Non, nous n’avons plus affaire au même bac : il est plus facile à obtenir (p. 64) ».

Des contradictions patentes

Ne souhaitant pas verser explicitement dans le « populisme », Emmanuel Todd se fourvoie totalement quand « n’appréciant pas, d’instinct, le populisme moralisateur de Michéa et surtout l’association systématique que ses fidèles en ont tiré entre libéralisme des mœurs et libéralisme économique, entre réformes sociétales et financiarisation de l’économie, constatant avec tristesse son influence grandissante dans la contestation en France, j’avais relu Lasch dans l’intention, je l’avoue, de pouvoir dire que Michéa ne l’avait pas compris, que Lasch, tout de même, c’était autre chose – par exemple, l’optimisme et le pragmatisme américains, etc. Désillusion. À la relecture, j’ai trouvé Lasch moralisateur (pp. 131 – 132) ». Pointe ici une once de jalousie intellectuelle envers Jean-Claude Michéa, cet Emmanuel Todd qui aurait gagné de nombreux esprits… L’auteur en profite pour dénigrer, peut-être avec raison, « l’utilisation de la notion de common decency, tiré d’Orwell, si présente dans le discours des jeunes contestataires, de droite et de gauche, de l’ordre établi, [qui] résulte d’une fondamentale erreur de perspective historique sur l’anthropologie du monde ouvrier des années 1880 – 1939 (p. 128) ». La « décence commune » ne concerne pas en 2020 dans une société cassée et mondialisée dans laquelle « le diplôme vaut quelque chose même quand il ne vaut rien. Même dépourvu de contenu intellectuel, il est un titre donnant accès, dans un monde désormais stratifié et économiquement bloqué, à des emplois, des fonctions, des privilèges. Le diplôme est devenu, dans une société où la mobilité sociale a dramatiquement chuté, un titre de noblesse (pp. 78 – 79) ». C’est dans ce contexte bouleversé que « nous assistons à l’émergence d’une classe moyenne dominante dans un contexte d’appauvrissement (p. 113) ».

Ne souhaitant pas verser explicitement dans le « populisme », Emmanuel Todd se fourvoie totalement quand « n’appréciant pas, d’instinct, le populisme moralisateur de Michéa et surtout l’association systématique que ses fidèles en ont tiré entre libéralisme des mœurs et libéralisme économique, entre réformes sociétales et financiarisation de l’économie, constatant avec tristesse son influence grandissante dans la contestation en France, j’avais relu Lasch dans l’intention, je l’avoue, de pouvoir dire que Michéa ne l’avait pas compris, que Lasch, tout de même, c’était autre chose – par exemple, l’optimisme et le pragmatisme américains, etc. Désillusion. À la relecture, j’ai trouvé Lasch moralisateur (pp. 131 – 132) ». Pointe ici une once de jalousie intellectuelle envers Jean-Claude Michéa, cet Emmanuel Todd qui aurait gagné de nombreux esprits… L’auteur en profite pour dénigrer, peut-être avec raison, « l’utilisation de la notion de common decency, tiré d’Orwell, si présente dans le discours des jeunes contestataires, de droite et de gauche, de l’ordre établi, [qui] résulte d’une fondamentale erreur de perspective historique sur l’anthropologie du monde ouvrier des années 1880 – 1939 (p. 128) ». La « décence commune » ne concerne pas en 2020 dans une société cassée et mondialisée dans laquelle « le diplôme vaut quelque chose même quand il ne vaut rien. Même dépourvu de contenu intellectuel, il est un titre donnant accès, dans un monde désormais stratifié et économiquement bloqué, à des emplois, des fonctions, des privilèges. Le diplôme est devenu, dans une société où la mobilité sociale a dramatiquement chuté, un titre de noblesse (pp. 78 – 79) ». C’est dans ce contexte bouleversé que « nous assistons à l’émergence d’une classe moyenne dominante dans un contexte d’appauvrissement (p. 113) ».

Todd s’inquiète d’« une nouvelle théorie du ruissellement (p. 260) » via un vigoureux mépris social, car « le mépris est au cœur du macronisme (p. 261) ». Il le résume par « voter Macron, dès le premier tour, c’est donc voter contre Le Pen (p. 248) ». Il ajoute même que « la France “ ouverte ” […] avait montré dès 2017 qu’elle était plus motivée par la haine d’un lepénisme bien français […] que par le désir de découvrir le monde (p. 320) ». Il critique un Hexagone de « petits bourgeois gavés de fausse conscience (p. 339) » pour qui « les réfugiés forment désormais […] le cœur de [leurs] préoccupations socio-politiques (p. 267) ».

Todd s’inquiète d’« une nouvelle théorie du ruissellement (p. 260) » via un vigoureux mépris social, car « le mépris est au cœur du macronisme (p. 261) ». Il le résume par « voter Macron, dès le premier tour, c’est donc voter contre Le Pen (p. 248) ». Il ajoute même que « la France “ ouverte ” […] avait montré dès 2017 qu’elle était plus motivée par la haine d’un lepénisme bien français […] que par le désir de découvrir le monde (p. 320) ». Il critique un Hexagone de « petits bourgeois gavés de fausse conscience (p. 339) » pour qui « les réfugiés forment désormais […] le cœur de [leurs] préoccupations socio-politiques (p. 267) ».

Cette haine des classes laborieuses suspectées de lepénisation avancée se vérifie avec l’épisode des Gilets jaunes. Non seulement l’auteur ne pardonne pas à Emmanuel Macron et à son entourage « l’instrumentalisation de l’antisémitisme dans leur lutte contre (p. 311) » eux, mais « il est clair que la violence de la crise des Gilets jaunes, la violence de la répression en particulier, a fait de lui le président du parti de l’Ordre. […] En 2017, il était le président du XXIe siècle. Au sortir des européennes, il est un président du XIXe siècle (p. 322) ». Irrité par l’agitation sociale et séduite par les « réformes » ambitieuses de démantèlement de la société, l’électorat droitard se rue maintenant en masse vers les candidats de La République en branle. « Telle est l’ironie du macronisme : l’homme qui a aboli l’ISF a été plébiscité par des salariés très moyens. Il existe un terme technique français pour désigner les individus placés dans ce genre de situation : “ cocus ” (p. 240). »

Là où Emmanuel Todd exagère, c’est quand il insinue que « le Rassemblement national au service de l’ordre […] a joué un rôle trouble. Tout en affirmant soutenir les Gilets jaunes, il a, de fait, entériné la répression (p. 308) ». Il remarque de manière pernicieuse qu’« il existe une catégorie qui a voté à 50 % – davantage encore que les ouvriers – pour Marine Le Pen : les gendarmes (p. 242) ». Il se contredit néanmoins puisqu’il mentionne « le journal L’Essor de la gendarmerie nationale du 1er février 2019 [qui] se félicite que “ seuls 10 % des tirs LBD 40 ont été effectués par des gendarmes ” (p. 279) ». Ce faible pourcentage annule sa théorie de convergence implicite entre les deux finalistes de la présidentielle de 2017. Ce n’est pas demain qu’on verra Marine Le Pen nommée Premier ministre par Emmanuel Macron… En revanche, il n’est pas impossible que l’actuel locataire de l’Élysée se projette à « droite » et collabore avec une jeune retraitée de la politique, directrice d’une « école » politique lyonnaise en toc et dont le cercle rapproché aiguillonné par un mensuel inintéressant travaille à une fantasmatique union des droites… Déjà, à l’occasion du second tour des municipales, dans de nombreuses villes telles Lyon ou Bordeaux, LREM fusionne avec Les Républicains chiraco-sarkozystes. Les électorats macronien et filloniste sont finalement très proches dans leurs aspirations de retraités rentiers décatis.

Le coup de tonnerre politique serait en fait l’arrivée à Matignon d’une personnalité « écolo-autoritaire » plus ou moins progressiste (Ségolène Royal ou Valérie Pécresse). Cette nomination ne serait pas une surprise, surtout s’il s’agit d’une manœuvre désespérée de l’« État profond (p. 324) » hexagonal. Bien que niant toute thèse conspirationniste, Emmanuel Todd emploie trois fois ce terme lourd de sens. Il s’interroge même : Macron serait-il « le candidat de l’État profond ? (p. 230) » Lors d’une allocution devant les ambassadeurs en août 2019, le chef de l’État a lui-même employé l’expression. Pour Todd, « Macron l’emporte parce qu’il a, avec lui, non pas le grand capitalisme mais l’État profond et parce que tout en lui suggère que rien ne va changer (p. 249) ». Qu’entend-il par « État profond » ? Todd n’apporte aucune réponse. Il n’a jamais lu les études de Henry Coston et d’Emmanuel Ratier. En bon structuraliste marxien influencé par les travaux précurseurs du conservateur Frédéric Le Play, il entreprend en revanche une nouvelle stratigraphie de la société française.

Les quatre strates sociales de l’Hexagone

À sa base se trouve le « prolétariat (p. 124) », soit environ 30 % de la population composée d’ouvriers et d’employés non qualifiés (25 % sont français ou européens, et 5 % extra-européens). Les agriculteurs, les professions intermédiaires (techniciens et infirmières), les employés qualifiés, les artisans et les petits commerçants, etc., forment 50 % de la population française, ce qui constitue une « majorité atomisée (p. 123) ». La « petite bourgeoisie CPIS (pour cadres et professions intellectuelles supérieures) (p. 122) » représente 19 %. Enfin, le dernier 1 % correspond à l’« aristocratie stato-financière (p. 120) ». Cette dernière coïncide à peu près à l’« État profond ». Emmanuel Todd dénonce le « modèle d’une société où le problème central n’est pas le monstre néo-libéral, mais bien plutôt un État qui dévore la société et qui, par inadvertance idéologique et bureaucratique, menace soudain de mort sociale, par des taxes, les plus fragiles, qui sont souvent du côté de l’entreprise, salariés ou tout petits entrepreneurs (p. 350) ». Cette « aristocratie stato-financière se croit financière, alors qu’elle est étatique (p. 341) ».

Bien que cette nouvelle nomenklatura s’organise autour de deux mondes distincts parfois antagonistes (les ultra-riches et la très haute fonction publique peuplée d’anciens élèves de l’ENA, de Polytechnique, des Écoles des Mines), « la haute-bureaucratie y domine; la culture du marché y est dominée, si bien que l’on y trouve un néo-libéralisme loufoque géré par des énarques qui n’acceptent pas au fond la simple loi de l’offre et de la demande. Un tel magma conceptuel ne peut être que dysfonctionnel (p. 169) ». Le plus bel exemple de ce dysfonctionnement permanent a longtemps été personnifié par Guillaume Pépy, le très discutable président de la SNCF. Ces « aristocrates » d’un nouveau genre « commencent leur carrière à Bercy, mais considèrent qu’ils ont raté leur vie s’ils y travaillent encore à quarante ans. Leur objectif est d’aller dans le privé multiplier par dix, voire par cinquante, un salaire déjà très confortable, quitte ensuite à retourner dans la fonction publique (pp. 213 – 214) ». Le journaliste de L’Obs, Vincent Jauvert, avec ses deux enquêtes (4), ne dit pas autre chose. La facilité de passer du public au privé et réciproquement – le « pantouflage » – s’appuie sur un ensemble de clubs discrets et influents dont le plus important demeure Le Siècle. Ce 1 % incarne la Caste qui parasite et pille la population française.

Tandis que ses chiens de garde médiatiques célèbrent un « vivre ensemble » meurtrier ainsi que le sociétalisme – Todd s’étonne de ces « 66 % des juges désormais [qui] sont des femmes (p. 309) » (Où est donc la fameuse parité ?), d’où son constat amer : « L’émancipation des femmes se déploie simultanément pour assumer la violence, en tant que juges, et pour la rejeter, en tant qu’électrices (p. 328) » -, la Caste peut « tout vendre, tout brader, tout voler à la nation : le rétrécissement du capitalisme industriel français nous garantit l’affaiblissement du secteur privé. Paradoxalement, les politiques “ néo-libérales ” suivies en France, en détruisant le capitalisme industriel, en restreignant, par l’euro, l’initiative privée, ne peuvent que mener à un renforcement de l’État en tant qu’agent autonome (p. 262) ». Loin des sornettes libérales « statophobes », le libéralisme 3.0 a besoin d’un État toujours plus omnipotent qui écrase toutes les résistances culturelles, politiques et sociales au marché. Aux États-Unis, la guerre entre le capitalisme industriel plutôt protectionniste, le néo-capitalisme commercial libre-échangiste et le capitalisme hyper-libéral de l’économie numérique a produit un Donald J. Trump. Dans l’Hexagone, « la victoire de Macron démontre, en un sens, qui est le vrai patron en France : l’État libéré des partis, plutôt qu’un capitalisme sous perfusion. […] À travers Macron nous avons vécu l’arrivée directe au pouvoir de l’État devenu un acteur politique autonome (p. 231) ». Est-ce vraiment une novation pour un pays tel que le nôtre bâti autour et par une volonté régalienne ? Emmanuel Todd ne saisit pas que le Français est d’instinct un homo status. Sans État, – nounou ou pas -, il se perd vite.

Si cette « pègre » s’approprie l’État en France, elle appartient néanmoins, à l’instar des « petits bourgeois CPIS [qui] font partie des perdants du système [… des] “ losers ” d’en haut (p. 240) », à la catégorie sociologique des larbins à leur propre insu. En effet, depuis la Grande Récession de 2007 – 2008, « l’aristocratie stato-financière, si elle peut continuer de s’enrichir et de placer son argent dans des paradis fiscaux, perd son statut de classe dirigeante. Elle devient une sorte de bourgeoisie coloniale, relais d’un système impérial dont elle ne partage plus la direction (pp. 191 – 192) ». Cette « mafia » reporte alors sa frustration vers les classes populaires. « En échec partout, humiliée partout, notre classe supérieure s’est trouvée le peuple français comme bouc émissaire en le traitant de fainéant aux réformes (p. 263) » ou l’infantilise et le culpabilise à propos de l’épidémie de covid-19. Voilà pourquoi Emmanuel Todd assène que « le bon animal totémique pour Macron dans une société dont le tissu est en décomposition, dont il s’acharne à dépouiller les entreprises publiques et à attaquer les blessés, c’est peut-être la hyène (p. 333) ». Il ne recevra pas de si tôt un appel téléphonique du président de la République…

Alignement anglo-saxon

L’auteur l’assume, lui qui craint dans un avenir proche un « coup d’État 2.0 (p. 355) » de la part des autorités. « Ce livre est […] civique et expérimental. Et expérimental par civisme. […] Parce que la France est menacée et que publier, dans dix ans, un livre – écrite sans doute en exil en Angleterre – sur les raisons de l’effondrement de la démocratie dans notre pays aurait présenté très peu d’intérêt (pp. 11 – 12). » Anglophone et ancien étudiant, puis enseignant à Cambridge, Emmanuel Todd garde les yeux de Chimène pour le Royaume Uni. Londres n’est-elle pas la ville la plus vidéo-surveillée d’Europe ?Conservateurs, travaillistes et libéraux-démocrates ont bien restreint la liberté d’expression outre-Manche.

Excessivement germanophobe, il ne cache pas une évidente anglomanie. Pour lui, « l’Angleterre fut et reste notre grande alliée, depuis l’Entente cordiale, et le seul pays d’Europe avec lequel nous ayons une collaboration militaire réelle et efficace (p. 251) ». Quel est le nombre de soldats britanniques qui se battent au Sahel aux côtés des forces françaises ? Cet historien oublie que la diplomatie français fut souvent à la remorque du Foreign Office avant 1914 et pendant l’Entre-deux-guerres. Le 3 septembre 1939, la République déclare la guerre à l’Allemagne après la déclaration de guerre de la Grande-Bretagne au moyen d’une banale loi de finance. Ce suivisme diplomatique catastrophique s’applique aussi aux milieux atlantistes. Le Brexit ne le surprend pas; il le satisfait plutôt. « Dans un pays qui a perdu son indépendance, la reconquête de l’indépendance est la priorité absolue (p. 358). » Certes, mais quelle indépendance « nationale » qu’il ne précise pas ? Politique ? Économique ? Militaire ? Culturelle ? Démographique ?

Excessivement germanophobe, il ne cache pas une évidente anglomanie. Pour lui, « l’Angleterre fut et reste notre grande alliée, depuis l’Entente cordiale, et le seul pays d’Europe avec lequel nous ayons une collaboration militaire réelle et efficace (p. 251) ». Quel est le nombre de soldats britanniques qui se battent au Sahel aux côtés des forces françaises ? Cet historien oublie que la diplomatie français fut souvent à la remorque du Foreign Office avant 1914 et pendant l’Entre-deux-guerres. Le 3 septembre 1939, la République déclare la guerre à l’Allemagne après la déclaration de guerre de la Grande-Bretagne au moyen d’une banale loi de finance. Ce suivisme diplomatique catastrophique s’applique aussi aux milieux atlantistes. Le Brexit ne le surprend pas; il le satisfait plutôt. « Dans un pays qui a perdu son indépendance, la reconquête de l’indépendance est la priorité absolue (p. 358). » Certes, mais quelle indépendance « nationale » qu’il ne précise pas ? Politique ? Économique ? Militaire ? Culturelle ? Démographique ?

Au-delà d’une simple anglophilie, Emmanuel Todd témoigne d’un vibrant tropisme étatsunien. « Nous, Français, sommes du côté de la liberté, n’est-ce pas ?, et nous devrons, comme les géopoliticiens américains, suivre Trump. Nous rallier au populisme américain en somme (p. 161). » Il se félicite que « la répartition constitutionnelle des pouvoirs […] laisse [à Trump] une vaste zone de libre action en matière de politique commerciale et il est en train de tenir ses promesses protectionnistes. Son attitude reste hésitante vis-à-vis de l’Europe et, en particulier, de l’Allemagne, devenue pour les États-Unis un adversaire industriel. Mais il a rallié l’establishment géopolitique à sa stratégie d’affrontement avec la Chine. Sa motivation première était de taxer les importations chinoises pour protéger les travailleurs américains. Or, dans le même temps, l’avancée menaçante de la Chine en mer du Sud inquiétait une bonne partie de l’establishment américain, qui est arrivée à la conclusion que le moment était venu de briser la superpuissance montante (pp. 160 – 161) ». Contrairement toutefois à diverses franges souverainistes, l’auteur appelle clairement à « renoncer à demander la sortie de l’OTAN […]. Pour sortir de l’euro sans trop de casse, soyons clairs, nous aurons besoin d’un appui massif des autorités monétaires américaines, de la FED (p. 360) », soit se libérer de Berlin et de Bruxelles pour se réfugier sous Londres et Washington. La France détient encore l’arme nucléaire ! Il regrette que les Gilets jaunes n’aient pas été la variante française du populisme à la sauce trumpienne… Il justifie son surprenant raisonnement géopolitique. « Un pays qui vit sous emprise doit avoir des alliés puissants pour s’en sortir, qu’il n’a pas à aimer mais à utiliser. Un seul pays peut permettre à la France d’échapper à l’euro. […] C’est celui qui ne veut pas d’un système impérial européen dominé par l’Allemagne : les États-Unis. Le salut de la France passe par l’aide des Américains. Je serais tenté de dire : comme d’habitude (p. 359). » Il ne comprend pas que l’« État profond » US se répartit depuis 1945 les rôles entre les tenants d’un continent européen brisé en États souverains factices malléables à l’exemple de la Pologne nationale-conservatrice du PiS, et les zélotes d’une intégration pseudo-européenne autour d’une Allemagne elle-même fort docile envers Washington et Wall Street. L’auteur écarte dès le départ de sa réflexion quelques « puissances » géopolitiques « secondaires » telles que la Russie, l’Iran, la Chine ou l’Inde. La libération de la France passera nécessairement par l’émancipation réelle des Européens de la servitude volontaire culturelle anglo-saxonne. Emmanuel Todd ne se dirige pas vers cette direction libératrice. Bien au contraire…

Comme son auteur, Les Luttes de classes en France au XXIe siècle est un livre qui agacera par sa relative naïveté. Il donne cependant le point de vue iconoclaste d’un membre du sérail médiatico-intellectuel. Cet ouvrage présente le mérite de démontrer qu’un certain souverainisme français ne se soucie pas de l’enjeu identitaire ethnique et spirituel. D’après Emmanuel Todd, « nous sortons du sociétal et des valeurs identitaires pour retrouver le socio-économique. L’identité de la France, c’est la lutte des classes, pas de taper sur les Arabes ou de se prendre pour des Allemands (5) ». Quant à l’Albo-Européen, l’ennemi est aussi bien le bankster que le républicain cosmopolite anti-européen, les ONG immigrationnistes que l’occidentaliste atlantiste.

Georges Feltin-Tracol

Notes

1 : Guy Mettan, Le continent perdu. Plaidoyer pour une Europe démocratique et souveraine, Éditions des Syrtes, 2019, p. 184.

2 : Idem.

3 : cf. Pierre de Villemarest, Le coup d’État de Markus Wolf. La guerre des deux Allemagnes 1945 – 1991, Stock, 1991.

4 : cf. Vincent Jauvert, Les intouchables d’État. Bienvenue en Macronie, Robert Laffont, 2018, et Les Voraces. Les élites et l’argent sous Macron, Robert Laffont, 2020. La rapacité de la Caste ne date pas de Macron. Elle se manifeste dès le second mandat de Mitterrand avec le retour au pouvoir en 1988 de l’« État PS » aux dépens de l’« État RPR » issu des accointances profondes entre des réseaux bientôt « affairo-gaullistes » et certains parrains criminels liés à la French Connection. Les enquêtes de Jauvert pourraient aussi émaner de quelques factions socialo-hollandaises de l’« État profond » hexagonal critiques envers certains gestes diplomatiques de Macron à l’égard de la Russie.

5 : Entretien avec Emmanuel Todd dans Libération du 22 janvier 2020.

• Emmanuel Todd avec la collaboration de Baptiste Touverey, Les Luttes de classes en France au XXIe siècle, Le Seuil, 2020, 376 p., 22 €.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Breizh-info.com :

Breizh-info.com :

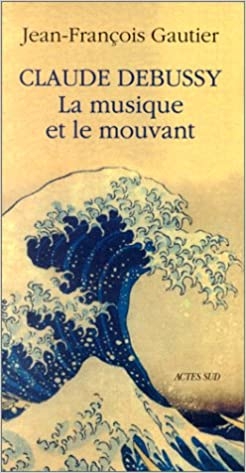

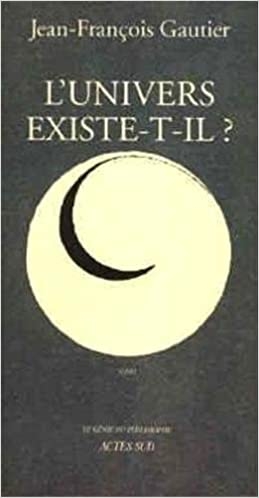

Jean-François Gautier collabora, il y a près d’un quart de siècle, à ma revue Antaios, au moment de la publication simultanée de deux essais remarqués L’Univers existe-t-il ? et Claude Debussy. La musique et le mouvant, tous deux chez Actes Sud. D’emblée, le personnage suscita chez moi une sorte de fascination : docteur en philosophie, assistant à l’Université de Libreville, et donc promis à une carrière sans histoire de mandarin, ce disciple de Julien Freund et de Lucien Jerphagnon, deux grands maîtres de la pensée non conformiste, rompit les amarres pour se lancer dans des recherches personnelles, devenant même rebouteux après de brillantes études d’étiopathie sous la houlette de Christian Trédaniel – encore un personnage haut en couleurs !

Jean-François Gautier collabora, il y a près d’un quart de siècle, à ma revue Antaios, au moment de la publication simultanée de deux essais remarqués L’Univers existe-t-il ? et Claude Debussy. La musique et le mouvant, tous deux chez Actes Sud. D’emblée, le personnage suscita chez moi une sorte de fascination : docteur en philosophie, assistant à l’Université de Libreville, et donc promis à une carrière sans histoire de mandarin, ce disciple de Julien Freund et de Lucien Jerphagnon, deux grands maîtres de la pensée non conformiste, rompit les amarres pour se lancer dans des recherches personnelles, devenant même rebouteux après de brillantes études d’étiopathie sous la houlette de Christian Trédaniel – encore un personnage haut en couleurs !  Plurivoque en revanche, le langage polythéiste traduit et interprète sans cesse ; monotone, le monothéiste se bloque pour se déchirer en controverses absurdes – les hérésies. A la disponibilité païenne, à la capacité de penser le monde de manière plurielle répond la crispation abrahamique, source de divisions et de conflits : ariens contre trinitaires, papistes contre parpaillots, chiites contre sunnites – ad maximam nauseam.

Plurivoque en revanche, le langage polythéiste traduit et interprète sans cesse ; monotone, le monothéiste se bloque pour se déchirer en controverses absurdes – les hérésies. A la disponibilité païenne, à la capacité de penser le monde de manière plurielle répond la crispation abrahamique, source de divisions et de conflits : ariens contre trinitaires, papistes contre parpaillots, chiites contre sunnites – ad maximam nauseam.  Très juste, cette articulation qu’il propose entre Dasein (être-là) et ce qu’il appelle Mitsein (être-avec) : les deux vont bien de pair. Très juste, l’idée que le paganisme en Europe ignore le Livre à prétentions universelles qui dicterait une vérité unique valable en tous temps et en tous lieux au détriment de vérités partielles, locales et plurielles. Nulle illusion de salut, nulle espérance au sens chrétien, mais l’énigme du monde, un monde éternel sans fin ni début, l’honnête reconnaissance de l’inconnaissable et le refus des rassurantes certitudes.

Très juste, cette articulation qu’il propose entre Dasein (être-là) et ce qu’il appelle Mitsein (être-avec) : les deux vont bien de pair. Très juste, l’idée que le paganisme en Europe ignore le Livre à prétentions universelles qui dicterait une vérité unique valable en tous temps et en tous lieux au détriment de vérités partielles, locales et plurielles. Nulle illusion de salut, nulle espérance au sens chrétien, mais l’énigme du monde, un monde éternel sans fin ni début, l’honnête reconnaissance de l’inconnaissable et le refus des rassurantes certitudes.

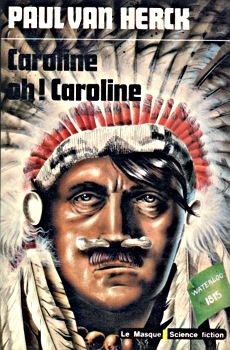

Outre sa couverture, Caroline Oh ! Caroline du Flamand Paul Van Herck (1938 – 1989) brave toutes les convenances historiques en proposant une satire déjantée proprement impubliable aujourd’hui. Inspiré à la fois par le style de Marcel Aymé et de la veine littéraire flamande souvent burlesque, Caroline Oh ! Caroline associe la farce, le fantastique, le psychadélisme et l’uchronie.

Outre sa couverture, Caroline Oh ! Caroline du Flamand Paul Van Herck (1938 – 1989) brave toutes les convenances historiques en proposant une satire déjantée proprement impubliable aujourd’hui. Inspiré à la fois par le style de Marcel Aymé et de la veine littéraire flamande souvent burlesque, Caroline Oh ! Caroline associe la farce, le fantastique, le psychadélisme et l’uchronie. Dans le cadre de sa mission secrète qui nécessite de traverser l’Atlantique par les airs grâce à l’un des tout premiers avions, on adjoint à Bill un second d’origine germanophone, prénommé Adolf, grand fan de Richard Wagner. C’est un « homme à la drôle de petite moustache et aux cheveux gris coiffés à la limande. Son regard était à la fois pénétrant et étrange (p. 46) ». Bien que regrettant la victoire franco-américaine de Waterloo, Adolf est prêt à explorer les « riches gisements au Tex-Ha, ou chez le Caliphe Hornia (p. 53) ».

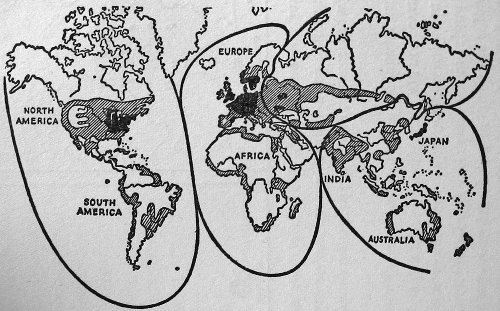

Dans le cadre de sa mission secrète qui nécessite de traverser l’Atlantique par les airs grâce à l’un des tout premiers avions, on adjoint à Bill un second d’origine germanophone, prénommé Adolf, grand fan de Richard Wagner. C’est un « homme à la drôle de petite moustache et aux cheveux gris coiffés à la limande. Son regard était à la fois pénétrant et étrange (p. 46) ». Bien que regrettant la victoire franco-américaine de Waterloo, Adolf est prêt à explorer les « riches gisements au Tex-Ha, ou chez le Caliphe Hornia (p. 53) ». Dans ce monde rêvé par Houria Bouteldja, Rokhaya Diallo et Lilian Thuram, existent dorénavant « deux Europes, l’Europe Noire et l’Europe Rouge. Comme les Noirs venaient de l’ouest, et les Indiens de l’est, ce furent l’Europe occidentale et l’Europe orientale, sans aucune référence à la réalité géographique, car la ligne de démarcation avait de singulières sinuosités (p. 172) ». Les relations entre les deux ensembles victorieux se chargent de méfiance réciproque quand il n’est pas la proie d’attentats à répétition. L’un d’eux revient à Bill.

Dans ce monde rêvé par Houria Bouteldja, Rokhaya Diallo et Lilian Thuram, existent dorénavant « deux Europes, l’Europe Noire et l’Europe Rouge. Comme les Noirs venaient de l’ouest, et les Indiens de l’est, ce furent l’Europe occidentale et l’Europe orientale, sans aucune référence à la réalité géographique, car la ligne de démarcation avait de singulières sinuosités (p. 172) ». Les relations entre les deux ensembles victorieux se chargent de méfiance réciproque quand il n’est pas la proie d’attentats à répétition. L’un d’eux revient à Bill.

Opposant résolu au traité de Maastricht en 1992, Emmanuel Todd n’a jamais hésité à rédiger des ouvrages incisifs tels que L’Illusion économique (1998), Après l’empire (2002), Après la démocratie (2008) ou Qui est Charlie ? (2015). Placé sous le patronage de Karl Marx qui « a dit beaucoup de bêtises, mais Marx était un esprit libre, il était capable de regarder la société de son temps avec ironie et cruauté. Il est le remède contre le panglossisme, c’est-à-dire cette propension à croire que tout va pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles (p. 19) », Les Luttes de classes en France au XXIe siècle ne déroge pas aux prédispositions politique de son auteur, républicain souverainiste – nationiste de gauche. « Ayant vécu Mai 68 à l’âge de 17 ans, à une époque où j’étais membre des Jeunesses communistes (p. 276) », il avoue avoir voté en 2017 « héroïquement (p. 250) » pour Jean-Luc Mélenchon avant de s’abstenir au second tour. Il assume aussi un « républicanisme national-cosmopolite ». Par exemple, « j’ai toujours été, me semble-t-il, et je reste, un immigrationniste raisonnable (p. 270) ». Il ajoute que « trois de mes petits-enfants ont un père d’origine algérienne. […] Je trouve mon propre “ remplacement ” par ces petits Français-là merveilleux (p. 267) ».

Opposant résolu au traité de Maastricht en 1992, Emmanuel Todd n’a jamais hésité à rédiger des ouvrages incisifs tels que L’Illusion économique (1998), Après l’empire (2002), Après la démocratie (2008) ou Qui est Charlie ? (2015). Placé sous le patronage de Karl Marx qui « a dit beaucoup de bêtises, mais Marx était un esprit libre, il était capable de regarder la société de son temps avec ironie et cruauté. Il est le remède contre le panglossisme, c’est-à-dire cette propension à croire que tout va pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles (p. 19) », Les Luttes de classes en France au XXIe siècle ne déroge pas aux prédispositions politique de son auteur, républicain souverainiste – nationiste de gauche. « Ayant vécu Mai 68 à l’âge de 17 ans, à une époque où j’étais membre des Jeunesses communistes (p. 276) », il avoue avoir voté en 2017 « héroïquement (p. 250) » pour Jean-Luc Mélenchon avant de s’abstenir au second tour. Il assume aussi un « républicanisme national-cosmopolite ». Par exemple, « j’ai toujours été, me semble-t-il, et je reste, un immigrationniste raisonnable (p. 270) ». Il ajoute que « trois de mes petits-enfants ont un père d’origine algérienne. […] Je trouve mon propre “ remplacement ” par ces petits Français-là merveilleux (p. 267) ».

En écrivant que « les élites allemandes souffrent plutôt d’un complexe d’infériorité vis-à-vis de l’Angleterre, depuis Guillaume II au moins. Elles ont beaucoup rêvé d’un “ couple ” anglo-allemand présidant aux destinées de la planète (note 1 p. 190) », Todd ignore peut-être que l’actuelle dynastie régnante de Buckingham Palace vient du Hanovre et que Guillaume II d’Allemagne cousine avec le père de Georges V d’Angleterre, Édouard VII. Entre 1945 et 1949, les Britanniques occupèrent le Nord-Ouest de la future RFA. La rééducation mentale collective entreprise par les Occidentaux a produit des institutions allemandes vassales de l’atlantisme, des États-Unis, de la City et de Wall Street. Guy Mettan rapporte une « révélation de l’ancien patron du contre-espionnage militaire allemand, le général Gerd-Helmut Komossa, suivant laquelle les chanceliers allemands, depuis la mise en place de la Loi fondamentale créant la République fédérale en 1949, doivent faire acte d’allégeance aux trois anciennes puissances occupantes de 1945 (1) ». Il cite ensuite un ancien collaborateur du chancelier social-démocrate Willy Brandt, Egon Bahr, expliquant qu’« on avait soumis au chancelier fraîchement élu Willy Brandt trois lettres à signer pour les ambassadeurs des puissances occidentales. Avec sa signature, il devait confirmer son accord aux restrictions légales exprimées par les gouverneurs militaires alliés à propos de l’application de la Loi fondamentale du 12 mai 1949 (2) ». Cette soumission perdure-t-elle depuis la réunification de 1990 ? D’une manière indirecte, très certainement. Il ne fait en outre guère de doute qu’Angela Merkel se trouve tenue par les services occidentaux. Son père, le pasteur Horst Kasner, a quitté Hambourg en 1954 pour la RDA. Avant la chute du Mur, la jeune Angela participait à la Jeunesse libre allemande et fut secrétaire à l’Académie des sciences du Département pour l’agitation et la propagande. Or, le journaliste et ancien agent de renseignement Pierre de Villemarest signale que la Jeunesse libre allemande servait souvent d’antichambre aux futurs cadres du Parti et de la Stasi sous la supervision directe du KGB soviétique (3). Il n’est pas non plus anodin d’apprendre qu’une fois la réunification acquise, la mère d’Angela Merkel adhéra au SPD et que son propre frère milita chez les Verts. Imbu de certitudes et sans connaître les coulisses de l’actualité, Emmanuel Todd se trompe sur un projet pseudo-européen qui ne tend pas vers un hypothétique IVe Reich, mais plutôt vers un condominium américain germano-atlantiste sur l’Europe.

En écrivant que « les élites allemandes souffrent plutôt d’un complexe d’infériorité vis-à-vis de l’Angleterre, depuis Guillaume II au moins. Elles ont beaucoup rêvé d’un “ couple ” anglo-allemand présidant aux destinées de la planète (note 1 p. 190) », Todd ignore peut-être que l’actuelle dynastie régnante de Buckingham Palace vient du Hanovre et que Guillaume II d’Allemagne cousine avec le père de Georges V d’Angleterre, Édouard VII. Entre 1945 et 1949, les Britanniques occupèrent le Nord-Ouest de la future RFA. La rééducation mentale collective entreprise par les Occidentaux a produit des institutions allemandes vassales de l’atlantisme, des États-Unis, de la City et de Wall Street. Guy Mettan rapporte une « révélation de l’ancien patron du contre-espionnage militaire allemand, le général Gerd-Helmut Komossa, suivant laquelle les chanceliers allemands, depuis la mise en place de la Loi fondamentale créant la République fédérale en 1949, doivent faire acte d’allégeance aux trois anciennes puissances occupantes de 1945 (1) ». Il cite ensuite un ancien collaborateur du chancelier social-démocrate Willy Brandt, Egon Bahr, expliquant qu’« on avait soumis au chancelier fraîchement élu Willy Brandt trois lettres à signer pour les ambassadeurs des puissances occidentales. Avec sa signature, il devait confirmer son accord aux restrictions légales exprimées par les gouverneurs militaires alliés à propos de l’application de la Loi fondamentale du 12 mai 1949 (2) ». Cette soumission perdure-t-elle depuis la réunification de 1990 ? D’une manière indirecte, très certainement. Il ne fait en outre guère de doute qu’Angela Merkel se trouve tenue par les services occidentaux. Son père, le pasteur Horst Kasner, a quitté Hambourg en 1954 pour la RDA. Avant la chute du Mur, la jeune Angela participait à la Jeunesse libre allemande et fut secrétaire à l’Académie des sciences du Département pour l’agitation et la propagande. Or, le journaliste et ancien agent de renseignement Pierre de Villemarest signale que la Jeunesse libre allemande servait souvent d’antichambre aux futurs cadres du Parti et de la Stasi sous la supervision directe du KGB soviétique (3). Il n’est pas non plus anodin d’apprendre qu’une fois la réunification acquise, la mère d’Angela Merkel adhéra au SPD et que son propre frère milita chez les Verts. Imbu de certitudes et sans connaître les coulisses de l’actualité, Emmanuel Todd se trompe sur un projet pseudo-européen qui ne tend pas vers un hypothétique IVe Reich, mais plutôt vers un condominium américain germano-atlantiste sur l’Europe. Ne souhaitant pas verser explicitement dans le « populisme », Emmanuel Todd se fourvoie totalement quand « n’appréciant pas, d’instinct, le populisme moralisateur de Michéa et surtout l’association systématique que ses fidèles en ont tiré entre libéralisme des mœurs et libéralisme économique, entre réformes sociétales et financiarisation de l’économie, constatant avec tristesse son influence grandissante dans la contestation en France, j’avais relu Lasch dans l’intention, je l’avoue, de pouvoir dire que Michéa ne l’avait pas compris, que Lasch, tout de même, c’était autre chose – par exemple, l’optimisme et le pragmatisme américains, etc. Désillusion. À la relecture, j’ai trouvé Lasch moralisateur (pp. 131 – 132) ». Pointe ici une once de jalousie intellectuelle envers Jean-Claude Michéa, cet Emmanuel Todd qui aurait gagné de nombreux esprits… L’auteur en profite pour dénigrer, peut-être avec raison, « l’utilisation de la notion de common decency, tiré d’Orwell, si présente dans le discours des jeunes contestataires, de droite et de gauche, de l’ordre établi, [qui] résulte d’une fondamentale erreur de perspective historique sur l’anthropologie du monde ouvrier des années 1880 – 1939 (p. 128) ». La « décence commune » ne concerne pas en 2020 dans une société cassée et mondialisée dans laquelle « le diplôme vaut quelque chose même quand il ne vaut rien. Même dépourvu de contenu intellectuel, il est un titre donnant accès, dans un monde désormais stratifié et économiquement bloqué, à des emplois, des fonctions, des privilèges. Le diplôme est devenu, dans une société où la mobilité sociale a dramatiquement chuté, un titre de noblesse (pp. 78 – 79) ». C’est dans ce contexte bouleversé que « nous assistons à l’émergence d’une classe moyenne dominante dans un contexte d’appauvrissement (p. 113) ».

Ne souhaitant pas verser explicitement dans le « populisme », Emmanuel Todd se fourvoie totalement quand « n’appréciant pas, d’instinct, le populisme moralisateur de Michéa et surtout l’association systématique que ses fidèles en ont tiré entre libéralisme des mœurs et libéralisme économique, entre réformes sociétales et financiarisation de l’économie, constatant avec tristesse son influence grandissante dans la contestation en France, j’avais relu Lasch dans l’intention, je l’avoue, de pouvoir dire que Michéa ne l’avait pas compris, que Lasch, tout de même, c’était autre chose – par exemple, l’optimisme et le pragmatisme américains, etc. Désillusion. À la relecture, j’ai trouvé Lasch moralisateur (pp. 131 – 132) ». Pointe ici une once de jalousie intellectuelle envers Jean-Claude Michéa, cet Emmanuel Todd qui aurait gagné de nombreux esprits… L’auteur en profite pour dénigrer, peut-être avec raison, « l’utilisation de la notion de common decency, tiré d’Orwell, si présente dans le discours des jeunes contestataires, de droite et de gauche, de l’ordre établi, [qui] résulte d’une fondamentale erreur de perspective historique sur l’anthropologie du monde ouvrier des années 1880 – 1939 (p. 128) ». La « décence commune » ne concerne pas en 2020 dans une société cassée et mondialisée dans laquelle « le diplôme vaut quelque chose même quand il ne vaut rien. Même dépourvu de contenu intellectuel, il est un titre donnant accès, dans un monde désormais stratifié et économiquement bloqué, à des emplois, des fonctions, des privilèges. Le diplôme est devenu, dans une société où la mobilité sociale a dramatiquement chuté, un titre de noblesse (pp. 78 – 79) ». C’est dans ce contexte bouleversé que « nous assistons à l’émergence d’une classe moyenne dominante dans un contexte d’appauvrissement (p. 113) ». Todd s’inquiète d’« une nouvelle théorie du ruissellement (p. 260) » via un vigoureux mépris social, car « le mépris est au cœur du macronisme (p. 261) ». Il le résume par « voter Macron, dès le premier tour, c’est donc voter contre Le Pen (p. 248) ». Il ajoute même que « la France “ ouverte ” […] avait montré dès 2017 qu’elle était plus motivée par la haine d’un lepénisme bien français […] que par le désir de découvrir le monde (p. 320) ». Il critique un Hexagone de « petits bourgeois gavés de fausse conscience (p. 339) » pour qui « les réfugiés forment désormais […] le cœur de [leurs] préoccupations socio-politiques (p. 267) ».

Todd s’inquiète d’« une nouvelle théorie du ruissellement (p. 260) » via un vigoureux mépris social, car « le mépris est au cœur du macronisme (p. 261) ». Il le résume par « voter Macron, dès le premier tour, c’est donc voter contre Le Pen (p. 248) ». Il ajoute même que « la France “ ouverte ” […] avait montré dès 2017 qu’elle était plus motivée par la haine d’un lepénisme bien français […] que par le désir de découvrir le monde (p. 320) ». Il critique un Hexagone de « petits bourgeois gavés de fausse conscience (p. 339) » pour qui « les réfugiés forment désormais […] le cœur de [leurs] préoccupations socio-politiques (p. 267) ».

Excessivement germanophobe, il ne cache pas une évidente anglomanie. Pour lui, « l’Angleterre fut et reste notre grande alliée, depuis l’Entente cordiale, et le seul pays d’Europe avec lequel nous ayons une collaboration militaire réelle et efficace (p. 251) ». Quel est le nombre de soldats britanniques qui se battent au Sahel aux côtés des forces françaises ? Cet historien oublie que la diplomatie français fut souvent à la remorque du Foreign Office avant 1914 et pendant l’Entre-deux-guerres. Le 3 septembre 1939, la République déclare la guerre à l’Allemagne après la déclaration de guerre de la Grande-Bretagne au moyen d’une banale loi de finance. Ce suivisme diplomatique catastrophique s’applique aussi aux milieux atlantistes. Le Brexit ne le surprend pas; il le satisfait plutôt. « Dans un pays qui a perdu son indépendance, la reconquête de l’indépendance est la priorité absolue (p. 358). » Certes, mais quelle indépendance « nationale » qu’il ne précise pas ? Politique ? Économique ? Militaire ? Culturelle ? Démographique ?

Excessivement germanophobe, il ne cache pas une évidente anglomanie. Pour lui, « l’Angleterre fut et reste notre grande alliée, depuis l’Entente cordiale, et le seul pays d’Europe avec lequel nous ayons une collaboration militaire réelle et efficace (p. 251) ». Quel est le nombre de soldats britanniques qui se battent au Sahel aux côtés des forces françaises ? Cet historien oublie que la diplomatie français fut souvent à la remorque du Foreign Office avant 1914 et pendant l’Entre-deux-guerres. Le 3 septembre 1939, la République déclare la guerre à l’Allemagne après la déclaration de guerre de la Grande-Bretagne au moyen d’une banale loi de finance. Ce suivisme diplomatique catastrophique s’applique aussi aux milieux atlantistes. Le Brexit ne le surprend pas; il le satisfait plutôt. « Dans un pays qui a perdu son indépendance, la reconquête de l’indépendance est la priorité absolue (p. 358). » Certes, mais quelle indépendance « nationale » qu’il ne précise pas ? Politique ? Économique ? Militaire ? Culturelle ? Démographique ?

Sterker nog: er is eigenlijk véél meer overeenstemming in de geopolitieke wereld dan er in de economische wereld is. Zonder dat die overeenstemming met de macht van de straat afgedwongen wordt (cfr. de zogenaamde consensus in de wetenschappelijke wereld over klimaatopwarming, afgedwongen door activistische politieke instellingen en dito van mediatieke roeptoeters voorziene burgers). Er zijn een aantal verschillende verklaringsmodellen, geen daarvan is volledig, en er is sprake van voortschrijdend inzicht, maar de voorlopige conclusies gaan geen radicaal verschillende richtingen uit. Én het is ook gewoon een razend interessant kennisdomein, zeker in tijden waarin grotendeels gedaan wordt alsof grenzen voor eeuwig vastliggen, handels- en andere oorlogen zich bedienen van flauwe excuses, en gedateerde internationale instellingen hun leven proberen te rekken.

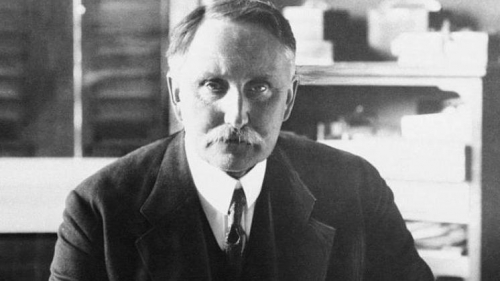

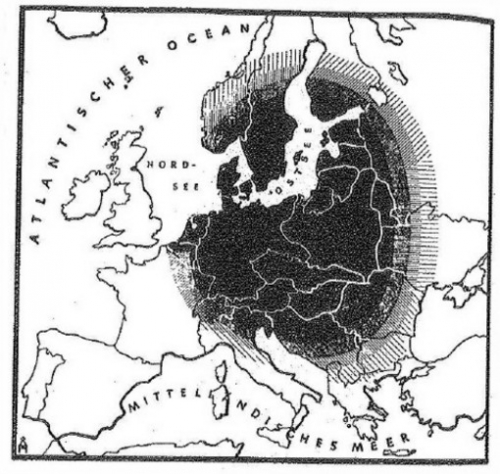

Sterker nog: er is eigenlijk véél meer overeenstemming in de geopolitieke wereld dan er in de economische wereld is. Zonder dat die overeenstemming met de macht van de straat afgedwongen wordt (cfr. de zogenaamde consensus in de wetenschappelijke wereld over klimaatopwarming, afgedwongen door activistische politieke instellingen en dito van mediatieke roeptoeters voorziene burgers). Er zijn een aantal verschillende verklaringsmodellen, geen daarvan is volledig, en er is sprake van voortschrijdend inzicht, maar de voorlopige conclusies gaan geen radicaal verschillende richtingen uit. Én het is ook gewoon een razend interessant kennisdomein, zeker in tijden waarin grotendeels gedaan wordt alsof grenzen voor eeuwig vastliggen, handels- en andere oorlogen zich bedienen van flauwe excuses, en gedateerde internationale instellingen hun leven proberen te rekken. En dan is er natuurlijk ook nog Karl als vader van Albrecht. De twee kwamen na de “vlucht” van Hess in een neerwaartse spiraal terecht (het nationaal-socialistische regime was zich wél bewust van het feit dat er een samenhang was tussen Hess en de Haushofers die véél verder ging dan het promoten van geopolitieke ideeën), maar zelfs binnen die spiraal bleven ze een merkwaardig evenwicht bewaren. Een evenwicht tussen afkeuring en goedkeuring van de Führer, tussen conservatisme en nationaal-socialisme, tussen oost en west, tussen esoterisme en wetenschap. Een evenwicht dat kennelijk heel moeilijk te begrijpen is in hysterische tijden als de onze en dat daarom steeds weer afgedaan wordt als onzin. Een evenwicht dat Karl Haushofer niet kon redden van een gevangenschap in Dachau en Albrecht Haushofer van executie in de nasleep van het conservatieve von Stauffenberg-complot. Een evenwicht dat Karl Haushofer en zijn echtgenote Martha definitief verloren toen ze zich op 10 maart 1946 achtereenvolgens vergiftigden en ophingen (al lijkt me dat, in combinatie met het lot van Hess, sowieso ook weer een eigenaardigheid).

En dan is er natuurlijk ook nog Karl als vader van Albrecht. De twee kwamen na de “vlucht” van Hess in een neerwaartse spiraal terecht (het nationaal-socialistische regime was zich wél bewust van het feit dat er een samenhang was tussen Hess en de Haushofers die véél verder ging dan het promoten van geopolitieke ideeën), maar zelfs binnen die spiraal bleven ze een merkwaardig evenwicht bewaren. Een evenwicht tussen afkeuring en goedkeuring van de Führer, tussen conservatisme en nationaal-socialisme, tussen oost en west, tussen esoterisme en wetenschap. Een evenwicht dat kennelijk heel moeilijk te begrijpen is in hysterische tijden als de onze en dat daarom steeds weer afgedaan wordt als onzin. Een evenwicht dat Karl Haushofer niet kon redden van een gevangenschap in Dachau en Albrecht Haushofer van executie in de nasleep van het conservatieve von Stauffenberg-complot. Een evenwicht dat Karl Haushofer en zijn echtgenote Martha definitief verloren toen ze zich op 10 maart 1946 achtereenvolgens vergiftigden en ophingen (al lijkt me dat, in combinatie met het lot van Hess, sowieso ook weer een eigenaardigheid). Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme: tijd, werk en invloed

Karl Haushofer en het nationaal-socialisme: tijd, werk en invloed

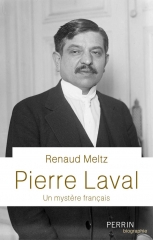

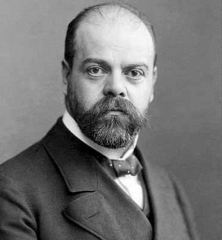

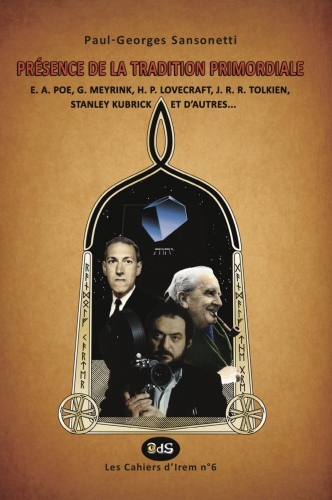

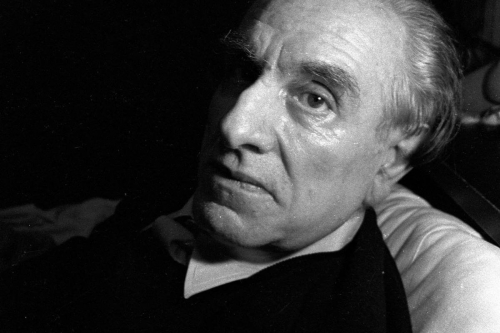

Renaud Meltz vient de livrer, avec les Éditions Perrin, une monumentale et phénoménale biographie de Pierre Laval, l'homme le plus détesté de l'histoire de France. Pacifiste forcené, partant de l’extrême gauche, maire d'Aubervilliers, sénateur, président du Conseil, il bascule vers le centre droit tout en s'enrichissant de façon troublante. Acteur clé de la mort de la République en juillet 40, il invente la Collaboration avec l'Allemagne nazie pensant qu'il "roulera Hitler" et qu'il sera la sauveur de la France. Il finira par céder à tout, à aider au pillage du pays, et à livrer les juifs à la déportation. Renaud Meltz grâce à des archives neuves ou peu exploitées renouvelle profondément la vision que nous avions de Pierre Laval dans ce livre remarquablement écrit et subtilement construit par un mariage réussi de chapitres thématiques et chronologiques. Abonnez vous aux Voix de l'histoire et partagez si vous avez aimé. Merci.

Renaud Meltz vient de livrer, avec les Éditions Perrin, une monumentale et phénoménale biographie de Pierre Laval, l'homme le plus détesté de l'histoire de France. Pacifiste forcené, partant de l’extrême gauche, maire d'Aubervilliers, sénateur, président du Conseil, il bascule vers le centre droit tout en s'enrichissant de façon troublante. Acteur clé de la mort de la République en juillet 40, il invente la Collaboration avec l'Allemagne nazie pensant qu'il "roulera Hitler" et qu'il sera la sauveur de la France. Il finira par céder à tout, à aider au pillage du pays, et à livrer les juifs à la déportation. Renaud Meltz grâce à des archives neuves ou peu exploitées renouvelle profondément la vision que nous avions de Pierre Laval dans ce livre remarquablement écrit et subtilement construit par un mariage réussi de chapitres thématiques et chronologiques. Abonnez vous aux Voix de l'histoire et partagez si vous avez aimé. Merci.

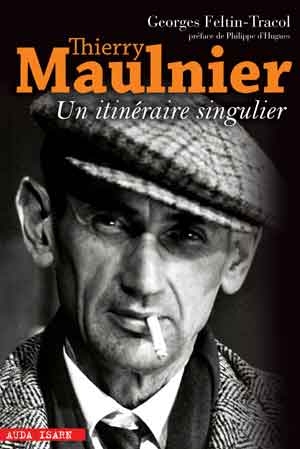

Thierry Maulnier, nom de plume de Jacques Louis André Talagrand (1909 – 1988), a rédigé de nombreux essais, écrit plusieurs pièces de théâtre et donné bien des préfaces. Sa bibliographie comporte cependant une omission de taille : l’absence de Révolution Nationale. L’avenir de la France. Cet ouvrage s’apparente à une sorte de fantôme dont diverses personnes ont nié son existence réelle.

Thierry Maulnier, nom de plume de Jacques Louis André Talagrand (1909 – 1988), a rédigé de nombreux essais, écrit plusieurs pièces de théâtre et donné bien des préfaces. Sa bibliographie comporte cependant une omission de taille : l’absence de Révolution Nationale. L’avenir de la France. Cet ouvrage s’apparente à une sorte de fantôme dont diverses personnes ont nié son existence réelle. Cette hypothèse expliquerait la non reconnaissance de cette édition par Thierry Maulnier d’autant que la même année sort chez Lardanchet La France la guerre et la paix. Dans cet autre recueil, voulu celui-ci par Maulnier, se trouvent trois textes présents dans Révolution Nationale : « Guerre mondiale et Révolution nationale » à l’identique dans les deux ouvrages tandis que les premiers paragraphes de « Rester la France » et « La médiation française » ont été réécrits pour cette parution. Dès la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Thierry Maulnier publie chez Gallimard Violence et Conscience qui « a été écrit en 1942 et 1943 (p. 1) » et qui contient une version modifiée et enrichie à partir du deuxième paragraphe de « Révolution prolétarienne et réaction patriarcale ». En 1946, chez un jeune éditeur moins consensuel, La Table Ronde, paraît Arrière-pensées qui réunit des chroniques « écrites et publiées entre le printemps de 1941 et le printemps de 1944 (p. 5) ». Par rapport à Révolution Nationale, on relit souvent dans une version modifiée, voire changée, « Les poseurs de rails », « Avant l’assaut », « Erreurs de jeunesse », « L’assaut des médiocres », « Les “ intellectuels ” sont-ils responsables du désastre ? », « Un jugement sur Racine », « L’art et l’éducation », « Polémique d’ancien régime » et « L’esprit français est-il coupable ? » qui s’intitule dans Révolution Nationale « Controverses sur l’esprit français » (1). On suppose que les textes qui forment Révolution Nationale proviennent directement des périodiques. Dans le cas des recueils autorisés, Thierry Maulnier a retravaillé certains passages afin de les lier aux autres textes et d’en donner une cohérence interne évidente.