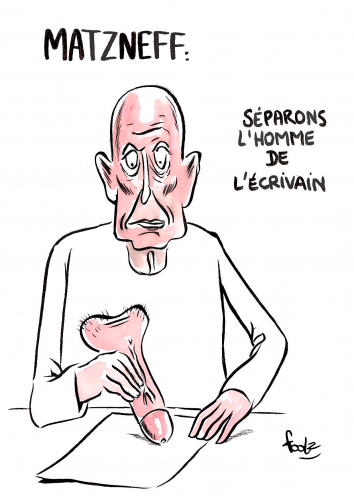

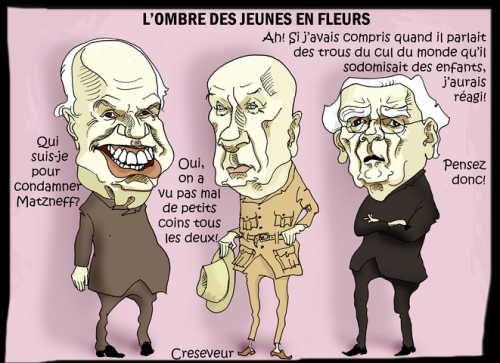

Nous pouvons lire, à l'entrée Robert Brasillach du truculent Dictionnaire des injures littéraires de Pierre Chalmin (1), une méchanceté écrite par Gabriel Matzneff pour Le Figaro littéraire : «Brasillach que plus personne ne lirait aujourd'hui si, au lieu d'avoir été fusillé, il était mort écrasé par un autobus en juin 1944».

Nous pourrions retourner cette saillie du reste assez stupide car Brasillach continue d'être lu, à Gabriel Matzneff, en lui faisant remarquer que plus personne ne le lirait aujourd'hui si, à la place des orifices de jeunes enfants des deux sexes, il évoquait dans ses livres si paresseux, comme tout un chacun ou presque, ceux de ses seules épouse (notre Lovelace des bacs à sable a été marié, brièvement) et (innombrables) maîtresses. Lire Gabriel Matzneff, ce n'est en effet pas être sensible à sa prétendue petite musique, ce n'est pas manifester sa dilection pour les auteurs antiques, ce n'est pas soutenir, plus ou moins silencieusement, un de ces hérauts, de plus en plus fatigué à vrai dire et qui a besoin pour se déplacer de sa canne à pommeau doré, de la droite buissonnière qui fut très souvent garçonnière, ce n'est pas s'intéresser au subtil mélange entre envolées métaphysiques et cabrioles priapistiques, ce n'est certainement pas défendre la liberté de l'esprit contre ce qu'il appelle les quakers et les quakeresses de la pruderie.

Lire Gabriel Matzneff, ce n'est même pas s'offrir un de ces petits plaisirs secrets que, bien jeune, nous nous accordions en lisant en cachette les textes de Sade et de Casanova alors même que, selon l'auteur, nous ne saurions lire la description détaillée de fines parties de plaisir entre un adulte et un jeune enfant sans éprouver nous-même un désir trouble. Or, si l'imagination d'un jeune adolescent (et même celle d'un adulte) peut être ravie, au sens premier du terme, par les pages où Sade déploie ses infernales machines de souffrances et de plaisir ou par la truculence arsouille et irrévérencieuse du Vénitien, les passages où Gabriel Matzneff évoque ses parties de jambes en l'air, eux, sont absolument tout ce que l'on voudra, libidineux, pornographiques donc cliniques, ridicules ou drôles, mais jamais érotiques.

Lire Gabriel Matzneff, c'est donc très sûrement perdre son temps. Lire Gabriel Matzneff, c'est assez vite tout de même (sauf lorsque l'on ne sait pas lire, cette cécité est fort répandue) découvrir que le maître que nous cherchions, jeune, que tout jeune enfant passant sa vie à dévorer des livres cherche plus ou moins sans le savoir, est un petit professeur bagué, cravaté et dégénéré, que l'esprit libre tant vanté dans notre société soumise à des milliers de diktats aussi invisibles que sournois n'est qu'un pleurnicheur vouant aux gémonies celles (les renégates, dit-il) qui l'ont plaqué et renié, que l'homme fort ne craignant aucune polémique est un pauvre type esseulé et qui, devenant vieux, sera non seulement toujours esseulé, de plus en plus seul à vrai dire mais surtout de plus en plus pathétique, un vit bientôt flaccide condamné à subir les gestes du personnel soignant d'une maison de retraite en guise de fier étendard affichant son mépris des «vieux culs nécrophages de la rue Sébastien-Bottin» (2), que le théologien à la mode de Vladivostok est un mécréant à la petite semaine affirmant que le Christ semble s'être «fait chair, flesh, que pour nous permettre de tringler les premières communiantes et de tailler des pipes aux petits chanteurs à la queue de bois» (pp. 12-3, l'auteur souligne), que le pécheur impénitent, Gilles de Rais saupoudré de talc ayant sa place à toutes les bonnes tables de Saint-Germain-des-Prés, écrit chacun de ses textes ou presque sans jamais parvenir à masquer son cri («Pardonnez-moi ! Pardonnez-moi !»), rêvant de «confession publique» comme au temps où le sacrement de pénitence représentait quelque chose «chez les chrétiens primitifs», et saisissant l'occasion inespérée que lui offre Jacques Chancel en réintroduisant ladite «confession publique dans nos mœurs» (p. 13) par le biais de sa collection, tout en hurlant de trouille et de sainte horreur au moment de monter sur le bûcher, alors que Gilles de Rais, lui, comme oublie de le rappeler notre hagiographe gaminophile, est devenu grand parce que ses crimes immondes sont indissociables du pardon qu'il a demandé, à genoux, aux mères et aux pères des enfants qu'il a dilacérés, violés et tués, avant de finir rôti, pour la plus grande gloire des cieux et la purification nécessaire d'un monstre trahi par le diable qu'il n'est jamais parvenu à conjurer.

Petit auteur, auteur mineur si l'on veut, Gabriel Matzneff n'est pas un homme mineur mais un petit homme ridicule et exécrable.

Je ne perdrai toutefois pas mon temps à ferrailler avec ce pédéraste comme lui-même aime à se décrire, qu'il s'agisse de l'affubler de cet épithète de nature plutôt que de celui de paidophile ou pédophile qui lui convient du reste admirablement, ou de rejoindre ce vieux rétiaire cacochyme et larmoyant, autrefois éphèbe impertinent pressé de vivre et de jouir, sur le terrain boueux où il a livré l'un de ses combats les plus minables et truqués (3), insultant ceux qu'il appelle les sycophantes de persister à ne pas comprendre que son art littéraire, dont il se fait une si haute opinion, ne saurait être jugé à l'aune sordide et lilliputienne de la morale.

Je me contenterai donc de frapper au point censé être le plus douloureux pour un cacographe, étant donné que ces hongres sont toujours persuadés que non seulement ils savent écrire, mais que leur œuvre, rare ou abondante, possède quelque qualité indéniable dans la sphère esthétique. Ce point, c'est justement le livre et lui seul, sa qualité littéraire supposée donc, qui devrait le hisser hors de la tourbe puante des minables considérations moralisatrices ou sentant le vieux slip de l'ordre prétendûment conservateur voire réactionnaire qui serait la mort de notre écrivain réputé libre et affranchi de tout, et qui se laisserait pourtant mourir s'il devait passer plus d'une journée sans pouvoir bénéficier du bienfait immarcescible d'une salutaire pédicure.

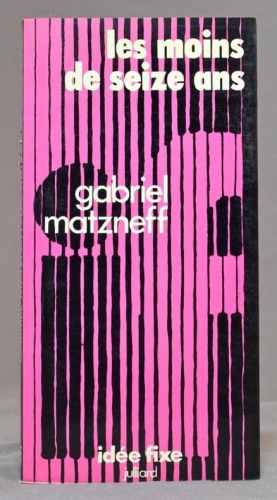

Les moins de seize ans ne constituent même pas un livre scabreux, et il est infiniment drôle de relire les stupidités qui furent écrites lorsqu'il parut, sous la plume de Roland Jaccard pour Le Monde qui évoque un «livre provocant et salutaire, courageux et spirituel» ou de Thierry Garcin pour Le Quotidien de Paris qui parle d'un ouvrage ayant créé de «salutaires remous, pour avoir mis les professionnels du progressisme au pied du mur».

Ce livre, s'il constitue, en effet, une confession non point douloureuse ou choquante mais ridicule, s'il évoque la plus grande idée fixe ou obsession, le mot est de Matzneff lui-même, de l'auteur, qui avoue que ses «obsessions sont pareilles à ces baudruches qu'on attache sous les aisselles des petits enfants qui apprennent à nager : qu'elles crèvent [et il] coule à pic» (p. 14), s'il détruit donc définitivement le rempart lilliputien pitoyable que les imbéciles et les vicieux (l'un et l'autre pouvant aller de concert bien sûr) dressent comme une muraille de Chine autour de l'écrivain qui n'écrirait qu'une fiction, soit une réalité purement esthétique, forcément et férocement artistique, parfaitement éloignée de la réalité (4), ce livre est la confession, navrante bien davantage que terrible, d'une solitude.

Solitude d'un écrivant qui se croit écrivain, parce qu'il a beaucoup lu les auteurs antiques, ce qui lui permet de saupoudrer son livre de latin non pas de cuisine mais d'alcôve («Mille puellarum, puerorum mille furores», repris aux Mémoires de Casanova) et de nous rappeler que l'Antiquité consommait les très jeunes enfants de façon immodérée, et solitude parce que, comme tous ceux de son espèce, Gabriel Matzneff est un écrivain mineur qui se croit grand. Il suffit, pour se convaincre de cette nullité bienheureuse, de relire les lettres de la petite fille au vilain monsieur qui ponctuent Les moins de seize ans, et qui sont censées, nous précise l'auteur en note, avoir «été écrites par une adolescente de quinze ans». «Il n'y a pas une ligne qui ne soit d'elle», termine, on s'en doute fièrement, Matzneff (p. 19) et, ma foi, je ne sais s'il s'agit de lettres bien réelles ou d'un jeu de l'écrivain s'étant mis à la place d'une jeune fille mais, dans les deux cas, leur nullité purement littéraire est patente, tout comme est ridicule, mais j'avais déjà souligné cette étonnante dimension à propos des larmoyants Carnets noirs, leur bêtise et fadeur érotiques : «X, mon amant pain d'épice, sucre d'orge, sucre d'or, je t'aime, tu sais, je t'aime» (p. 51). Gabriel Matzneff, aussi sordide qu'un phallus gonflé à l'hélium au beau milieu d'une aventure de Maya l'abeille.

J'ose donc affirmer, contre l'évidence même semblerait-il, que la solitude est le sujet réel, profond, évident même des Moins de seize ans, et non pas les goûts sexuels de Gabriel Matzneff qui écrit pourtant qu'il n'a «jamais eu de rapports sexuels avec une personne de [s]on sexe qui soit âgée de plus de dix-sept ans, sauf une fois avec un garçon de vingt-deux, mais ce soir-là [ils avaient] fumé force sebsi de hasch, [ils étaient] complètement défoncés» (p. 22, l'auteur souligne).

Ce sujet réel, profond, évident, est la solitude et non pas la différence entre l'homosexualité, comiquement moquée, avec un don de prescience qu'il convient de saluer si nous songeons à l'épisode grotesque du mariage homosexuel («ils veulent l'honorabilité et la sécurité, le sourire de leur concierge et les palmes académiques, le certificat de bonnes mœurs et le contrat de mariage», p. 82) et la pédérastie ou plutôt, nous dit l'auteur qui pourtant prend grand soin de distinguer ces deux dernières réalités, la pédophilie (5).

Ce sujet réel, profond, évident, le seul à vrai dire, n'est pas ce que nous pourrions nommer la perversité de Gabriel Matzneff qui sait parfaitement que «la dissemblance psychique entre un adulte et un enfant est, elle aussi, une évidence» (p. 23) et qui jouit donc, mais en cachette, de l'étalage de cette dissemblance, comme tout pervers qui se respecte. Deux façons et deux façons seulement existent de pervertir l'innocence : la force brutale de la bête, et le coupable termine derrière des barreaux emmailloté dans une camisole de force et la ruse de l'esprit, qui est la marque des prédateurs supérieurs dont Gabriel Matzneff, qui se vante de n'avoir jamais rien arraché qui ne lui eût été par avance donné, fait évidemment partie. Je ne me prononce pas sur le type de peine que j'imagine pouvoir convenir à ce type de salopard amateur de «marginalité, [de] bohème, [de] solitude» (p. 81) et, surtout, qui n'est attiré que par une seule chose, moins les très jeunes filles et garçons qui, comme il le confesse, forment une espèce de troisième sexe (cf. pp. 24-5), que l'innocence (cf. p. 72).

Ce sujet unique est la solitude, pas même le caractère clandestin des amours de Gabriel Matzneff, qui affirme qu'il se «tamponne le coquillard» de l'approbation de la société, la «transgression» étant son équilibre, sa santé, sa joie (p. 84), qui écrit que «la chasse aux gosses [doit] demeure[r] un sport périlleux, et défendu !» (p. 85), qui avoue grivoisement qu'il s'est rapproché des scouts, un temps, pour disposer plus facilement de jeunes proies (cf. p. 93, Matzneff se décrivant même comme un «membre actif, il va sans dire» des scouts, sa carte de membre certifiant donc sa qualité de «pédagogue professionnel», bonne ruse pour qu'un père sourcilleux surprenant l'auteur en train de «sodomiser» son rejeton ne puisse donc que croire qu'il s'agissait «d'un de ces «grands jeux» éducatifs dont les scouts ont le secret», p. 94), Gabriel Matzneff qui ne cesse de nous rappeler qu'il est contraint de cacher ce qu'il appelle poétiquement ses «aventures de traverse» (p. 63), de se cacher, surtout avec les garçons, pour étancher ses passions non point secrètes, puisque l’œuvre de Gabriel Matzneff est tout entière une apologie lucide, revendiquée, décomplexée (6), passionnée de la pédérastie, mais condamnable moralement et, surtout, pénalement : «Pour les garçons, c'est une autre paire de manches. Si je ne cache pas trop mon amante de quinze ans, mes aventures avec les petits garçons se déroulent dans une stricte clandestinité» (p. 29).

Je discutais, il y a quelques jours à peine, avec une matznévienne hystérique (pléonasme) qui me soutenait par A + B que Gabriel Matzneff n'avait jamais commis ses larcins pédérastes mais qu'il les avait imaginés dans ses textes, donc sublimés. En somme, nul n'avait le droit de reprocher à un écrivain ce qu'il écrivait, et de citer bien évidemment d'autres salauds des lettres comme Céline : il me fut facile de lui opposer une bonne centaine des propres textes de l'auteur pour lui rappeler que Gabriel Matzneff ne s'est jamais caché d'aimer les «très jeunes [qui] sont tentants», surtout lorsqu'ils résident dans certains pays pauvres, Maroc ou Égypte, «où les gosses attendent souvent quelque profit de leurs complaisances amoureuses» (p. 44), l'auteur confessant très clairement qu'il a donc payé des gamins bien que, s'empresse-t-il d'ajouter, «si violence il y a, la violence du billet de banque qu'on glisse dans la poche d'un jean ou d'une culotte (courte) est malgré tout une douce violence. Il ne faut pas charrier. On a vu pire» (p. 45). En effet, nous avons par exemple vu un pédéraste écrire des livres pédérastiques depuis des dizaines d'années sans que personne ou presque n'y trouve à redire, alors, de quoi nous plaindrions-nous, sycophantes envieux que nous sommes ?

Le sujet évident, profond, unique de notre livre n'est pas la concaténation de sophismes qui tous n'ont qu'un seul but : décomplexer, légitimer, ancrer au passé le plus ancien et illustre des pratiques que la société contemporaine réprouve, y compris pénalement, à tort ou à raison, ce n'est pas du tout l'objet de cette note modeste : «La pédérastie, seule forme possible de la paternité pour celui qui répugne à fonder une famille» (pp. 73-4) ou bien encore : «Les adultes qui n'aiment pas les enfants ne supportent pas que les enfants soient aimés par ceux qui les aiment» (p. 41), sophismes d'autant plus vite enchaînés que, comme le sait parfaitement Gabriel Matzneff qui s'en vante (même s'il ne parle pas, dans ce cas, de lui-même), jamais aucun de ses jeunes amants «n'a trahi le secret, jamais aucun des enfants n'a porté plainte». L'auteur évoque l'affaire, à l'automne 1973, d'un «quinquagénaire, gros, moche, borgne, qui dans un village de l'Est, proche de Forbach, organisait chez lui des ballets roses» (pp. 42-3), mais il est évident que sous le masque du repoussant «Tonton Lucien» se cache le visage si lisse et beau (comme me le confia, le regard chaviré, l'une de ses récentes maîtresses) de Gabriel Matzneff. Il en évoque d'autres, de ces affaires scabreuses, comme celle liée à Mlle Hindley et M. Brady, «accusés d'avoir séduit, torturé et assassiné deux enfants et un adolescent» en 1964, l'auteur ayant d'ailleurs pris le soin d'écrire un article de défense, une «chronique, non recueillie en volume pour l'instant», pour ces «ogres» pour lesquels il avoue avoir «un faible» (p. 46). On a vu pire.

Le sujet évident, unique, profond, inavouable des Moins de seize ans n'est même pas ce jeu malsain avec le vocabulaire religieux, le pervertissement de l'amour, la parodie sacrilège consistant à affirmer que l'amour du pédéraste pour sa proie doit «être un amour qui féconde, libère, «donne le vie», tel l'Esprit-Saint dans la prière byzantine» (p. 65), puisque Matzneff claironne qu'il a donné, avant que du plaisir, de l'amour à ses amants et maîtresses, le sujet véritable de ce livre et de chacun des livres de l'auteur n'est pas cet appel constant, répété, troublant, au Jugement, à «l'heure adorable et terrible où nous nous présenterons devant l'autel nuptial du Christ» et où «nous serons jugés sur l'amour» (p. 33).

L'unique sujet, profond, véritable, incontournable des Moins de seize ans n'est pas le sacrilège et l'évocation de la souillure physique mais surtout spirituelle que cet homme indigne inflige à l'une de ses jeunes maîtresses : «Profitant de l'absence de ses parents, nous faisons pour la première fois l'amour dans sa chambre d'enfant, dans son petit lit, parmi ses poupées» (pp. 72-3).

L'unique sujet profond, véritable, évident, scandaleux, n'est pas le détournement parodique du sacré qui peut faire écrire à Gabriel Matzneff, minable chanoine Docre, des horreurs qui devraient le conduire à macérer durant les dernières années de sa vie dans une trappe oubliée où il passera ses journées à demander le pardon de Dieu sans oser ne serait-ce que chuchoter ses prières : «Coucher avec un/une enfant, c'est une expérience hiérophanique, une épreuve baptismale, une aventure sacrée» ou bien : «Pour un esprit religieux, faire l'amour avec un/une enfant, c'est célébrer la divine liturgie, épiclèse, communion au corps et au sang, dithyrambe du seigneur Dionysos» (p. 75).

Le sujet évident, unique, profond des Moins de seize ans et en fait de tous les livres de Gabriel Matzneff n'est pas sa peur, son immense peur de voir l'une de ses chères maîtresses ou cher amant prendre la poudre d'escampette (l'auteur maîtrise la rupture, à laquelle il a consacré un livre, tout comme il nous rappelle ici, plusieurs fois, l'insensibilité amoureuse de certains de ses jeunes compagnons de jeux, cf. p. 60), mais sa peur de s'entendre dire qu'il n'y a pas eu d'amour, mais du sexe et du vice, pas de beauté, mais de la baise sordide face à la «nécessaire clandestinité» (p. 67), grande peur du mal-pensant que celui-ci exorcise comme il peut, par exemple en faisant tenir à sa maîtresse de 15 ans ce discours qui exsude la peur, sous une apparente bonhomie, le bonheur ridicule d'une gamine confondant un vieux pervers avec l'homme de sa future vie de femme : «Mais même si un jour tu devais me faire souffrir, beaucoup souffrir, jamais l'idée ne pourrait seulement m'effleurer de regretter t'avoir connu. Je suis par avance payée au centuple de mon bonheur présent» (p. 51).

L'unique sujet, profond, visible, indéniable, de Gabriel Matzneff n'est pas le seul argument qu'il juge recevable pour interdire la pédérastie, du moins, soyons prudents, la réfréner : «Une femme, à la rigueur, on la prend, puis on la jette; mais c'est un jeu qu'à moins d'être un salaud ont doit s'interdire avec les très jeunes. Quinze ans est l'âge où l'on se tue par désespoir d'amour, ne l'oublions pas» (p. 57). Ne l'oublions pas en effet, et rappelons que des femmes ou des hommes de tout âge peuvent, par amour, tenter de se suicider ou réussir à le faire, et n'oublions pas les innombrables passages des Carnets noirs où Gabriel Matzneff traite comme une chienne l'une de ses maîtresses, surnommé Gilda, jeune femme qu'il sait pourtant fragile psychologiquement, et qu'il n'hésite pas à virer chaque fois qu'il a terminé de la baiser, oh, pardon, ce terme est grossier, choisissons celui, utilisé par l'auteur, de «gamahucher». Mais Gabriel Matzneff n'était sans doute pas, nous pouvons rêver (7), à l'époque où il a écrit ses Moins de seize ans, le Monsieur Ouine d'opérette et dolent qu'il est devenu quelques années plus tard, puisque, dans les années 70, il affirmait et écrivait que le fait d'aimer «un gosse n'a de sens que si cet amour l'aide à s'épanouir, à s'accomplir, à devenir pleinement soi-même, à faire voler en éclats les barreaux de la cage familiale, à repousser d'une main légère les faux devoirs auxquels le société prétend l'assujettir» (p. 65) comme celui, sans doute, d'honorer, par sa piété, une vertu antique que Matzneff devrait connaître, sa mère et son père.

La solitude de Gabriel Matzneff est le sujet de chacun de ses livres, exprimée en termes pathétiques (au sens premier de l'adjectif qui évoque la souffrance) lorsqu'il évoque, et il a raison, le fait que «la société occidentale moderne [...] rejette le pédéraste dans le non-être, royaume des ombres, Katobasiléia» (p. 30), le pédéraste étant «réduit à la fuite, au néant, au royaume de la mort» (p. 31).

La solitude de Gabriel Matzneff est le sujet de ce livre et de tous ses autres livres, lui qui se décrit comme «l'homme du discontinu», «l'homme de l'instant» qui «n'aime pas l'avenir», seul le présent le captivant (p. 63). Il est troublant de constater que c'est justement Gabriel Matzneff qui, il y a quelques années, me conseilla de lire un livre tout à fait remarquable, L'Homme du néant, dont je rendis d'ailleurs compte dans ma série intitulée Langages viciés, ouvrage surprenant dans lequel Max Picard analyse Hitler comme surgeon historique le plus accompli de l'homme creux, c'est-à-dire gonflé de néant, réduit à vivre dans un monde et une époque caractérisés par leur discontinuité radicale.

La solitude de Gabriel Matzneff, sa meilleure compagne, ne cesse-t-il de nous rappeler, et bien évidemment sa pire ennemie, qu'il s'agit de vaincre en multipliant, au long d'une journée, les amours décomposés, en multipliant les maîtresses car non seulement avoir «tenu dans vos bras, baisé, caressé, possédé un garçon de treize ans, une fille de quinze ans» fait paraître «fade, lourd, insipide» tout le reste (p. 69), mais aussi parce que même ces petits plaisirs peuvent, à la longue, surtout lorsqu'ils sont monodiquement répétés et enchaînés depuis des années tout de même, devenir ennuyeux.

La solitude de Gabriel Matzneff non pas tant, comme Richard Millet, dernier écrivain de langue française autoproclamé, que faiseur tout à fait conscient de n'être qu'un faiseur, la petite ritournelle de cet auteur n'étant confondue, après tout, avec une littérature digne de ce nom que par les imbéciles, à savoir toute une partie de la droite blogosphérique branchée qui aime Causeur et les raouts du Cercle cosaque (quoi, vous me dites que c'est la même chose ? En effet, Leroy ou Guillebon ont déjà colonisé ces petites officines de la contestation murrayienne branchée), ainsi que la gauche léoscheerienne, qui n'a pas encore, je crois, été suffisamment caractérisée, bien qu'il s'agisse d'un épiphénomène, comme l'est du reste toute mode. Plus curieux est le soutien du Point où Matzneff signe ses chroniques ridicules, mais il est vrai que Yann Moix, l'un des plus navrants barbouilleurs de la décennie, officie au Figaro pour le bonheur de ses lecteurs, alors...

Solitude du faiseur qui écrit comme il baise, en rigolant et en passant à la suivante ou au suivant : «C'est un trip super-débandant» (p. 70) pour sûr, tout comme l'est aussi, d'un seul point de vue stylistique, la platitude avec laquelle Matzneff évoque la nullité érotique de l'une de ses maîtresses : «Tout ce qu'elle savait faire, c'était écarter les cuisses et attendre que ça se passe. Jamais une initiative, jamais une caresse un peu sensuelle, d'évidence un corps d'homme ça ne l'intéressait ni ne l'excitait, ça la gênait plutôt. Une vraie bûche» (p. 71).

La solitude de Gabriel Matzneff, pur narcissisme et même «fixation autoérotique survenue à l'époque ambiguë de l'adolescence» (8) est l'unique sujet qu'il importe de lire et de critiquer : solitude de celui qui se croit écrivain et n'est qu'écrivant, parfois même cacographe poussif qui, à force de jouer de la flûte comme un moderne Joueur de Hamelin, finit quand même par connaître son unique petit air, grâce auquel il charmera les gosses, les vieilles salopes et les vieux porcs, solitude existentielle du prédateur contraint de se cacher, en France du moins, pour assouvir sa passion pédérastique et même pédophilique, solitude amoureuse de celui qui, à mesure qu'il se transforme en momie coquette, voit ses anciennes proies se transformer en ce qu'il appelle des renégates, solitude intellectuelle de ce Casanova des cours d'école, solitude spirituelle de celui qui, après la publication d'Isaïe réjouis-toi, perdit son «père spirituel» et qui, du moins à l'époque, se déclarait «éloigné de toute vie liturgique et sacramentelle», solitude eschatologique de ce Monsieur Du Paur qui, en baisant des gamins, déclare éprouver la «nostalgie du Christ, né de la Femme et de l'Esprit, adolescent vierge qui transfigure les contraires, sexe divinisé, intégrité retrouvée, plénitude, androgyne primordial, descendu au plus profond de l'enfer pour [le] ressusciter d'entre les morts, tel l'enfant bénie qui un soir d'août a posé sa main fraîche sur [son] front ardent» (p. 115).

Finalement, notre fier entrepreneur de démolitions n'est qu'un pervers lacrymal, qui planque sa trouille et son vice sous des paletots stylistiques et des prétentions littéraires censées frapper de nullité la morale petite-bourgeoise, à laquelle il aspire pourtant tout entier, que chacune de ses jérémiades invoque pour qu'elle daigne le reprendre et lui accorder un pardon mérité.

Finalement, notre Lovelace aux mille et une maîtresses et amants n'est qu'un vieil homme, désormais, qui réclame le jugement et le pardon et fait absolument tout ce qu'il peut pour procrastiner avec ce qu'il sait constituer son unique salut, intime, visible, évident, à savoir : une solitude rédimée qui ne permettra sans doute pas à son œuvre surestimée de survivre, mais qui conférera, peut-être, un semblant d'honneur à un homme qui, par chacun de ses actes et ses écrits, a bafoué cet honneur.

Finalement, notre libre penseur, notre hérésiarque, notre impénitent mécréant n'est qu'un cathare mal dans sa peau, un jouisseur affamé de chasteté et même de continence, un pervertisseur de l'esprit d'enfance qui confond le respect de la pureté et de l'innocence enfantines avec sa fringale comique et pathétique de baiser un Christ à l'image d'un angelot, un Origène qui attire les badauds en levant bien haut une paire de ciseaux avec laquelle il menace de se châtrer, et qu'il range aussitôt dans la poche de son veston jusqu'à son prochain numéro une fois qu'il a reçu un peu d'attention.

Pauvre Gabriel Matzneff, si pressé de jouir comme un bouc en éternelle érection, pauvre diable affamé de grandeur et de cohérence rimbaldienne, spirituelle donc, qui ne tirera même pas le dernier enseignement de celui qui fut son maître, Henry de Montherlant, qui eut l'élégance de ne pas imposer à ses semblables la vision d'un homme se transformant en pourriture libidineuse.

Notes

(1) Le Livre de poche, 2012, p. 96.

(2) Les moins de seize ans (Julliard, coll. Idée fixe, 1974), p. 12. Les pages entre parenthèses renvoient à cette édition.

(3) Truqué car enfin, sauf erreur de ma part, Franz-Olivier Giesbert, un de ces cumulards des honneurs factices à la française (puisqu'il est membre du Siècle, membre de l'Association Universelle des Cultures, membre du jury du Prix P. J. Redouté, du Prix Aujourd'hui, du Prix de la Fondation Mumm, du Prix Louis Pauwels, Président du Prix de la Fondation Alexandre Varenne et membre du Conseil d'Administration de l'Établissement public du Musée du Louvre depuis octobre 2000) qui lui a ouvert les colonnes du Point est aussi membre du jury du Prix Renaudot qui a récompensé son dernier ouvrage paru, Séraphin c'est la fin !.

(4) Lisons l'auteur : «Ces idées fixes, ces passions, ces obsessions, ces expériences nourrissent ma vie, qui elle-même nourrit mes livres, car je n'ai aucune imagination, et je ne puis exprimer sur la page blanche que ce que j'ai vécu, connu, éprouvé» (p. 16). À ce titre, le passage qui suit, et qui développe le fait que des auteurs comme Dostoïevski ou Thomas Mann ont été contraints de passer par la fiction pour mettre en scène leur goût immodéré des enfants, est exemplaire et sans la moindre ambiguïté, Gabriel Matzneff soulignant le fait que, lui au contraire, va ôter son masque à Dionysos, lequel peut «manger le morceau» (p. 17).

(5) «[...] à dix-huit ans passés on n'est plus un enfant; le règne de la pédophilie s'achève, commence celui de l'homosexualité» (p. 25).

(6) «J'ai horreur de Socrate, de Platon, de toute la mélasse sublime dont ils enrobent le désir et le plaisir, j'ai horreur de la pédérastie à prétentions pédagogiques. On peut caresser un jeune garçon sans se croire obligé de lui donner une leçon de maths ou d'histoire-géo dans la demi-heure qui suit. Et qu'on ne nous casse pas les pieds avec l'amour des âmes. L'âme, ça n'existe pas, et si ça existe, ça n'existe qu'incarnée, chair dorée, duveteuse [...]» (p. 32).

(7) Nous pouvons en effet rêver, car Matzneff semble avoir toujours été ce monstre propret et impeccablement vêtu que nous montrent ses plus récentes photographies : «Le plus important service que je puisse rendre à un adolescent, après lui avoir transmis tout ce que je suis capable de lui transmettre, c'est de lui enseigner à se passer de moi» (p. 66).

(8) Gabriel Matzneff cite à la page 81 le professeur Albeaux-Fernet, dans un article du Monde daté du 7 mai 1974.

Le livre de Grégory Roose, Pensées interdites, est parfait pour celui qui n’a jamais ouvert un ouvrage de politique ou que rebute l’idée de se plonger dans de grandes dissertations philosophiques, bref, un ouvrage idéal pour le Millénial ou quiconque lit peu.

Le livre de Grégory Roose, Pensées interdites, est parfait pour celui qui n’a jamais ouvert un ouvrage de politique ou que rebute l’idée de se plonger dans de grandes dissertations philosophiques, bref, un ouvrage idéal pour le Millénial ou quiconque lit peu.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Het lijkt erop dat de Iraniërs over een sterke mentaliteit beschikken om met een wereldmacht de confrontatie op te zoeken. Is hiervoor een historische verklaring?

Het lijkt erop dat de Iraniërs over een sterke mentaliteit beschikken om met een wereldmacht de confrontatie op te zoeken. Is hiervoor een historische verklaring?

Hazony defines the nation-state in contradistinction to two alternatives: tribal anarchy and imperialism. Tribal anarchy is basically a condition of more or less perpetual suspicion, injustice, and conflict that exists between tribes of the same nation in the absence of a common government. Imperialism is an attempt to extend common government to the different nations of the world, which exist in a state of anarchy vis-à-vis each other.

Hazony defines the nation-state in contradistinction to two alternatives: tribal anarchy and imperialism. Tribal anarchy is basically a condition of more or less perpetual suspicion, injustice, and conflict that exists between tribes of the same nation in the absence of a common government. Imperialism is an attempt to extend common government to the different nations of the world, which exist in a state of anarchy vis-à-vis each other. Hazony argues that nationalism has a number of advantages over tribal anarchy. The small states of ancient Greece, medieval Italy, and modern Germany wasted a great deal of blood and wealth in conflicts that were almost literally fratricidal, and that made these peoples vulnerable to aggression from entirely different peoples. Unifying warring “tribes” of the same peoples under a nation-state created peace and prosperity within their borders and presented a united front to potential enemies from without.

Hazony argues that nationalism has a number of advantages over tribal anarchy. The small states of ancient Greece, medieval Italy, and modern Germany wasted a great deal of blood and wealth in conflicts that were almost literally fratricidal, and that made these peoples vulnerable to aggression from entirely different peoples. Unifying warring “tribes” of the same peoples under a nation-state created peace and prosperity within their borders and presented a united front to potential enemies from without. The “mutual loyalty” at the heart of nation-states is a product of a common ethnicity. How does ethnic unity make free institutions possible? Every society needs order. Order either comes from within the individual or is imposed from without. A society in which individuals share a strong normative culture does not need a heavy-handed state to impose social order.

The “mutual loyalty” at the heart of nation-states is a product of a common ethnicity. How does ethnic unity make free institutions possible? Every society needs order. Order either comes from within the individual or is imposed from without. A society in which individuals share a strong normative culture does not need a heavy-handed state to impose social order. In fact, Hazony argues, imperialism is far more conducive to hatred and violence than nationalism.

In fact, Hazony argues, imperialism is far more conducive to hatred and violence than nationalism. The third principle is “government monopoly of organized force within the state” (p. 177), as opposed to tribal anarchy. A failed state is one in which different ethnic groups create their own militias.

The third principle is “government monopoly of organized force within the state” (p. 177), as opposed to tribal anarchy. A failed state is one in which different ethnic groups create their own militias. The difference between good nationalism and bad nationalism is simple: Good nationalism is universalist. A good nationalist wants to ensure the sovereignty of his own people, but does not wish to deny the sovereignty of other peoples. Instead, he envisions a global order of sovereign nations, to the extent that this is possible. Hazony, however, wishes to stop short of the idea of a universal right to self-determination, which I will deal with at greater length later.

The difference between good nationalism and bad nationalism is simple: Good nationalism is universalist. A good nationalist wants to ensure the sovereignty of his own people, but does not wish to deny the sovereignty of other peoples. Instead, he envisions a global order of sovereign nations, to the extent that this is possible. Hazony, however, wishes to stop short of the idea of a universal right to self-determination, which I will deal with at greater length later.

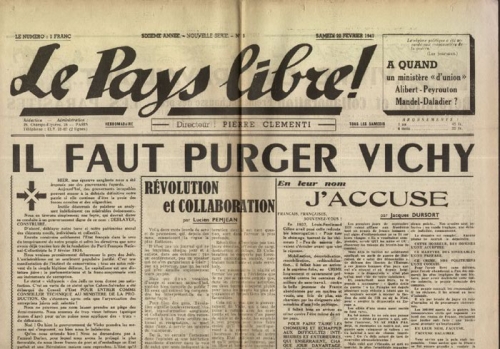

Aux débuts des années 1990, inquiète de la résistance nationale-patriotique en Russie contre Boris Eltsine, une certaine presse de caniveau fantasmait sur une hypothétique convergence « rouge – brun » en France. Sa profonde inculture l’empêcha de mentionner le national-bolchevisme allemand de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le souverainisme communiste réalisé en RDA et en Roumanie ou le national-communisme du philosophe Régis Debray à la fin des années 1970. Le philosophe français aurait certainement été surpris de savoir que son pays connut naguère un embryon national-communiste ou national-collectiviste six décennies plus tôt.

Aux débuts des années 1990, inquiète de la résistance nationale-patriotique en Russie contre Boris Eltsine, une certaine presse de caniveau fantasmait sur une hypothétique convergence « rouge – brun » en France. Sa profonde inculture l’empêcha de mentionner le national-bolchevisme allemand de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le souverainisme communiste réalisé en RDA et en Roumanie ou le national-communisme du philosophe Régis Debray à la fin des années 1970. Le philosophe français aurait certainement été surpris de savoir que son pays connut naguère un embryon national-communiste ou national-collectiviste six décennies plus tôt.

Acquis au racialisme scientifique, il popularisa le concept du Blut und Boden (Sang et Sol), espérant abolir une société industrielle fermée au monde des affaires afin de la remplacer par une société organique prenant sa base sur un système de nobilité agreste héréditaire.

Acquis au racialisme scientifique, il popularisa le concept du Blut und Boden (Sang et Sol), espérant abolir une société industrielle fermée au monde des affaires afin de la remplacer par une société organique prenant sa base sur un système de nobilité agreste héréditaire. Most widely held works

Most widely held works

Vous insistez beaucoup, pour l’efficacité de l’action métapolitique, sur la compréhension d’un contexte fait de l’emboîtement de trois éléments : l’Occident, le Système et le Régime. En quelques mots, que voulez-vous dire par là ?

Vous insistez beaucoup, pour l’efficacité de l’action métapolitique, sur la compréhension d’un contexte fait de l’emboîtement de trois éléments : l’Occident, le Système et le Régime. En quelques mots, que voulez-vous dire par là ?

R. R. Reno

R. R. Reno

La thèse n’est pas nouvelle. En 1984, le Club de l’Horloge sortait chez Albin Michel Socialisme et fascisme : une même famille ?. Ne connaissant pas ce livre, Frédéric Le Moal arrive néanmoins aux mêmes conclusions. Il se cantonne toutefois à la seule Italie en oubliant ses interactions européennes, voire extra-européennes (le péronisme en Argentine). Il circonscrit le fascisme en phénomène italien spécifique. Certes, il mentionne l’influence d’Oswald Spengler sur Mussolini, mais il en oublie le contexte international, à savoir l’existence protéiforme d’une révolution conservatrice non-conformiste. En outre, l’auteur ne souscrit pas à la thèse de Zeev Sternhell pour qui le fascisme italien a eu une matrice française.

La thèse n’est pas nouvelle. En 1984, le Club de l’Horloge sortait chez Albin Michel Socialisme et fascisme : une même famille ?. Ne connaissant pas ce livre, Frédéric Le Moal arrive néanmoins aux mêmes conclusions. Il se cantonne toutefois à la seule Italie en oubliant ses interactions européennes, voire extra-européennes (le péronisme en Argentine). Il circonscrit le fascisme en phénomène italien spécifique. Certes, il mentionne l’influence d’Oswald Spengler sur Mussolini, mais il en oublie le contexte international, à savoir l’existence protéiforme d’une révolution conservatrice non-conformiste. En outre, l’auteur ne souscrit pas à la thèse de Zeev Sternhell pour qui le fascisme italien a eu une matrice française.

Pourtant, la question du conservatisme est complexe car le terme, lui-même, renvoie à des phénomènes – et des réalités – politiques différents, du parti conservateur britannique (les Tories, au pouvoir au Royaume-Uni en alternance démocratique avec le Labour travailliste) au monolithique ancien Parti communiste soviétique (PCUS), dont les caciques étaient qualifiés de « conservateurs », sans doute en partie en raison de leur âge… Une seule chose est sûre, l’absence pérenne – ou presque (l’exception Fillon vaincue par le très progressiste hebdomadaire Le Canard enchaîné) – du terme dans le débat français, depuis la fin de la Révolution française au moins jusqu’à récemment (puisque l’on parle de néo-conservateurs que la gauche morale n’hésite pas, d’ailleurs, à qualifier de « néo-cons » – le discrédit sémantique est toujours au cœur des débats et fonctionne d’ailleurs, mais s’agissant de cette tendance, il s’agit, le plus souvent, de « libéraux américains » – donc, la gauche américaine issue des démocrates – défendant des thèses conservatrices liées à la défense de la nation : identités fédérées réaffirmées, rejet du « politically correct », rejet du fiscalisme…).

Pourtant, la question du conservatisme est complexe car le terme, lui-même, renvoie à des phénomènes – et des réalités – politiques différents, du parti conservateur britannique (les Tories, au pouvoir au Royaume-Uni en alternance démocratique avec le Labour travailliste) au monolithique ancien Parti communiste soviétique (PCUS), dont les caciques étaient qualifiés de « conservateurs », sans doute en partie en raison de leur âge… Une seule chose est sûre, l’absence pérenne – ou presque (l’exception Fillon vaincue par le très progressiste hebdomadaire Le Canard enchaîné) – du terme dans le débat français, depuis la fin de la Révolution française au moins jusqu’à récemment (puisque l’on parle de néo-conservateurs que la gauche morale n’hésite pas, d’ailleurs, à qualifier de « néo-cons » – le discrédit sémantique est toujours au cœur des débats et fonctionne d’ailleurs, mais s’agissant de cette tendance, il s’agit, le plus souvent, de « libéraux américains » – donc, la gauche américaine issue des démocrates – défendant des thèses conservatrices liées à la défense de la nation : identités fédérées réaffirmées, rejet du « politically correct », rejet du fiscalisme…). En effet, originellement, l’esprit conservateur est de nature collective : il vise à préserver un ordre naturel préexistant alors que le libéralisme post-révolutionnaire naît du développement des besoins exprimés individuellement. Le conservatisme ne nie pas la liberté mais se rattache davantage à la liberté concrète, plus qu’abstraite, à la liberté collective, plus qu’individuelle. Le triomphe de l’individualisme, état suprême du libéralisme, s’oppose au conservatisme des systèmes normatifs. C’est ici, à mon sens, que le renouveau du conservatisme prend tout son sens : le développement de l’individualisme a contribué à l’effacement des repères collectifs, identitaires, religieux ou culturels. La fin du bien commun a rendu la modernité, expression d’un libéralisme fondé sur l’individu, exécrable pour les « oubliés » du Système. L’extension des droits individuels comme le droit à l’enfant, exalté par les « progressistes », vient à exclure ce bien commun qu’est le droit de l’enfant à vivre au sein d’une famille. Alexandre Soljenitsyne dénonçait déjà, en 1978, dans Le déclin du courage, le matérialisme occidental issu de la société de consommation. Le déracinement, fruit de ce conservatisme anglo-saxon, a touché d’abord les classes populaires souvent qualifiées d’« oubliées » par nos chercheurs sociologues. La France des oubliés, c’est d’abord l’expression d’une société qui a fait de l’individualisme libéral son étalon, son exigence. Or, le conservatisme, forme d’enracinement, aurait pu, pourrait, peut encore venir tempérer ce système économique certes nécessaire mais qui doit constituer un des piliers d’une société tridimensionnelle et non le pilier central.

En effet, originellement, l’esprit conservateur est de nature collective : il vise à préserver un ordre naturel préexistant alors que le libéralisme post-révolutionnaire naît du développement des besoins exprimés individuellement. Le conservatisme ne nie pas la liberté mais se rattache davantage à la liberté concrète, plus qu’abstraite, à la liberté collective, plus qu’individuelle. Le triomphe de l’individualisme, état suprême du libéralisme, s’oppose au conservatisme des systèmes normatifs. C’est ici, à mon sens, que le renouveau du conservatisme prend tout son sens : le développement de l’individualisme a contribué à l’effacement des repères collectifs, identitaires, religieux ou culturels. La fin du bien commun a rendu la modernité, expression d’un libéralisme fondé sur l’individu, exécrable pour les « oubliés » du Système. L’extension des droits individuels comme le droit à l’enfant, exalté par les « progressistes », vient à exclure ce bien commun qu’est le droit de l’enfant à vivre au sein d’une famille. Alexandre Soljenitsyne dénonçait déjà, en 1978, dans Le déclin du courage, le matérialisme occidental issu de la société de consommation. Le déracinement, fruit de ce conservatisme anglo-saxon, a touché d’abord les classes populaires souvent qualifiées d’« oubliées » par nos chercheurs sociologues. La France des oubliés, c’est d’abord l’expression d’une société qui a fait de l’individualisme libéral son étalon, son exigence. Or, le conservatisme, forme d’enracinement, aurait pu, pourrait, peut encore venir tempérer ce système économique certes nécessaire mais qui doit constituer un des piliers d’une société tridimensionnelle et non le pilier central.

En prenant sept cas d’école de la conduite du changement dans les armées, Michel Goya propose ainsi avec S’adapter pour vaincre une analyse des rouages de l’adaptation des grandes structures militaires sous la pression de leur époque : qu’il s’agisse de l’ascension de l’armée prussienne au XIXe siècle, de la métamorphose de l’armée française durant la Première Guerre mondiale, du déclin de la Royal Navy au cours de la première moitié du XXe siècle ou encore de la confrontation de l’US Army avec la guerre moderne à partir de 1945, l’animateur du blog La Voie de l’épée met à chaque fois en lumière les inducteurs de la mue de la Pratique (avec un grand « P » sous la plume de l’auteur) au sein de ces organisations complexes. Car, pour Michel Goya, « faire évoluer une armée, c’est faire évoluer sa Pratique », cette même Pratique étant « le point de départ et d’arrivée du cycle de l’évolution ».

En prenant sept cas d’école de la conduite du changement dans les armées, Michel Goya propose ainsi avec S’adapter pour vaincre une analyse des rouages de l’adaptation des grandes structures militaires sous la pression de leur époque : qu’il s’agisse de l’ascension de l’armée prussienne au XIXe siècle, de la métamorphose de l’armée française durant la Première Guerre mondiale, du déclin de la Royal Navy au cours de la première moitié du XXe siècle ou encore de la confrontation de l’US Army avec la guerre moderne à partir de 1945, l’animateur du blog La Voie de l’épée met à chaque fois en lumière les inducteurs de la mue de la Pratique (avec un grand « P » sous la plume de l’auteur) au sein de ces organisations complexes. Car, pour Michel Goya, « faire évoluer une armée, c’est faire évoluer sa Pratique », cette même Pratique étant « le point de départ et d’arrivée du cycle de l’évolution ». Au-delà de la rétrospective historique, le principal intérêt de l’ouvrage est ainsi l’analyse percutante que livre Michel Goya sur les conditions d’apparition de cette innovation au sein d’une structure militaire. S’adapter pour vaincre montre comment les innovations de rupture ne viennent pas souvent de l’intérieur – contrairement à l’innovation dite « continue » – mais sont généralement imposées de l’extérieur, sous la pression de l’ennemi par exemple. On y voit également les viscosités et les biais cognitifs à l’œuvre, que ce soit l’effet générationnel des décideurs, la propension des armées à reproduire des modèles connus, la rivalité entre les services d’une même armée ou encore l’illusion de pouvoir piloter de manière centralisée le cycle du changement. Le rôle du politique pour faire passer les évolutions de rupture est également mis en avant, tout comme l’importance de créer les conditions de l’émergence d’un courant de pensée libre de réflexion non institutionnelle – que l’auteur considère d’ailleurs comme une forme indispensable de « réserve » opérationnelle pour les temps mauvais. On retiendra enfin l’importance pour une organisation militaire de pouvoir expérimenter, grâce à un surplus de ressources matérielles et de temps libre, comme ce fut le cas notamment dans les décennies qui précédèrent la Première Guerre mondiale : « Plus les unités disposent de temps libre et de moyens autonomes, et plus ce capital d’adaptation rapide est important. Inversement, plus les moyens sont comptés, surveillés et centralisés, et plus l’armée devient rigide. »

Au-delà de la rétrospective historique, le principal intérêt de l’ouvrage est ainsi l’analyse percutante que livre Michel Goya sur les conditions d’apparition de cette innovation au sein d’une structure militaire. S’adapter pour vaincre montre comment les innovations de rupture ne viennent pas souvent de l’intérieur – contrairement à l’innovation dite « continue » – mais sont généralement imposées de l’extérieur, sous la pression de l’ennemi par exemple. On y voit également les viscosités et les biais cognitifs à l’œuvre, que ce soit l’effet générationnel des décideurs, la propension des armées à reproduire des modèles connus, la rivalité entre les services d’une même armée ou encore l’illusion de pouvoir piloter de manière centralisée le cycle du changement. Le rôle du politique pour faire passer les évolutions de rupture est également mis en avant, tout comme l’importance de créer les conditions de l’émergence d’un courant de pensée libre de réflexion non institutionnelle – que l’auteur considère d’ailleurs comme une forme indispensable de « réserve » opérationnelle pour les temps mauvais. On retiendra enfin l’importance pour une organisation militaire de pouvoir expérimenter, grâce à un surplus de ressources matérielles et de temps libre, comme ce fut le cas notamment dans les décennies qui précédèrent la Première Guerre mondiale : « Plus les unités disposent de temps libre et de moyens autonomes, et plus ce capital d’adaptation rapide est important. Inversement, plus les moyens sont comptés, surveillés et centralisés, et plus l’armée devient rigide. »

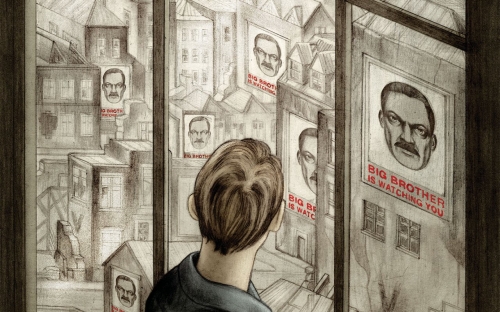

To his credit, Ryan does not spend much ink on critical analyses of the various presentations. That would make for a very fat and dreary book. In nearly every instance he’d have to tell us that the production was uneven and woefully miscast. I wondered if he was going to carp about the misconceived film adaptation of Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1997; American title: A Merry War). Not a bit of it; he leaves it to us to do the carping and ridicule. What he does provide is a rich concordance of Orwell presentations over the years, with often amazing production notes, technical details, and contemporary press notices. And if you don’t care to get that far into weeds, George Orwell on Screen is still an indispensable guidebook, pointing you to all sorts of bio-documentaries and dramatizations you might never discover on your own. This is particularly true of the many (mostly) BBC docos produced forty or fifty years ago, where you find such delights as Malcolm Muggeridge and Cyril Connolly lying down in tall grass and trading tales about their late, great friend.

To his credit, Ryan does not spend much ink on critical analyses of the various presentations. That would make for a very fat and dreary book. In nearly every instance he’d have to tell us that the production was uneven and woefully miscast. I wondered if he was going to carp about the misconceived film adaptation of Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1997; American title: A Merry War). Not a bit of it; he leaves it to us to do the carping and ridicule. What he does provide is a rich concordance of Orwell presentations over the years, with often amazing production notes, technical details, and contemporary press notices. And if you don’t care to get that far into weeds, George Orwell on Screen is still an indispensable guidebook, pointing you to all sorts of bio-documentaries and dramatizations you might never discover on your own. This is particularly true of the many (mostly) BBC docos produced forty or fifty years ago, where you find such delights as Malcolm Muggeridge and Cyril Connolly lying down in tall grass and trading tales about their late, great friend.

« Pour une évidente clarté sémantique, écrit-il, il serait préférable de laisser au Flamby normal, à l’exquise Najat Vallaud-Belkacem et aux morts vivants du siège vendu, rue de Solférino, ce mot de socialiste et d’en trouver un autre plus pertinent. Sachant que travaillisme risquerait de susciter les mêmes confusions lexicales, les termes de solidarisme ou, pourquoi pas, celui de justicialisme, directement venu de l’Argentine péronisme, seraient bien plus appropriés. »

« Pour une évidente clarté sémantique, écrit-il, il serait préférable de laisser au Flamby normal, à l’exquise Najat Vallaud-Belkacem et aux morts vivants du siège vendu, rue de Solférino, ce mot de socialiste et d’en trouver un autre plus pertinent. Sachant que travaillisme risquerait de susciter les mêmes confusions lexicales, les termes de solidarisme ou, pourquoi pas, celui de justicialisme, directement venu de l’Argentine péronisme, seraient bien plus appropriés. »

Certes, depuis une seconde rencontre à Hanoï en février 2019 qui fut un échec et une brève entrevue sur la ligne de démarcation de Panmunjom en juin dernier qui fit néanmoins de Donald Trump le premier président des États-Unis à fouler un instant le sol de la République populaire et démocratique de Corée (RPDC), les tensions reprennent entre Washington et Pyongyang en raison de la suffisance des États-Unis incapables de conclure le moindre compromis.

Certes, depuis une seconde rencontre à Hanoï en février 2019 qui fut un échec et une brève entrevue sur la ligne de démarcation de Panmunjom en juin dernier qui fit néanmoins de Donald Trump le premier président des États-Unis à fouler un instant le sol de la République populaire et démocratique de Corée (RPDC), les tensions reprennent entre Washington et Pyongyang en raison de la suffisance des États-Unis incapables de conclure le moindre compromis.

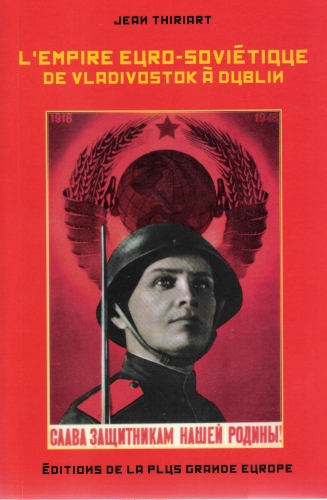

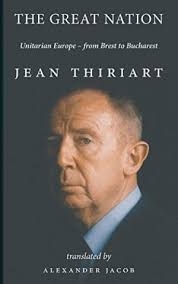

Dans cette ambitieuse perspective géopolitique, il dénonce bien sûr l’influence du sionisme en Europe et s’inquiète de la prolifération prochaine des lois liberticides. Il consent cependant à ce que l’Europe unifiée et libérée de l’emprise atlantiste protège « un “ petit ” Israël bucolique (frontières décrites par l’ONU) […]. Par contre, la paranoïa biblique d’extrême droite qui rêve du grand Israël jusqu’à l’Euphrate doit être dénoncée et combattue avec vigueur (p. 108) ». Cette approche ne doit pas surprendre. L’auteur a toujours revendiqué la supériorité de l’omnicitoyenneté politique sur les appartenances communautaires linguistiques, religieuses et ethniques. « La citoyenneté euro-soviétique ou grand-européenne doit devenir ce qu’a été la citoyenneté romaine (p. 237). » On comprend mieux pourquoi Alexandre Douguine s’en réclame bien que les deux hommes divergeaient totalement sur le plan spirituel. La République euro-soviétique de Thiriart serait une Fédération de Russie élargie à l’Eurasie septentrionale.

Dans cette ambitieuse perspective géopolitique, il dénonce bien sûr l’influence du sionisme en Europe et s’inquiète de la prolifération prochaine des lois liberticides. Il consent cependant à ce que l’Europe unifiée et libérée de l’emprise atlantiste protège « un “ petit ” Israël bucolique (frontières décrites par l’ONU) […]. Par contre, la paranoïa biblique d’extrême droite qui rêve du grand Israël jusqu’à l’Euphrate doit être dénoncée et combattue avec vigueur (p. 108) ». Cette approche ne doit pas surprendre. L’auteur a toujours revendiqué la supériorité de l’omnicitoyenneté politique sur les appartenances communautaires linguistiques, religieuses et ethniques. « La citoyenneté euro-soviétique ou grand-européenne doit devenir ce qu’a été la citoyenneté romaine (p. 237). » On comprend mieux pourquoi Alexandre Douguine s’en réclame bien que les deux hommes divergeaient totalement sur le plan spirituel. La République euro-soviétique de Thiriart serait une Fédération de Russie élargie à l’Eurasie septentrionale.