Prologue: the Anatomy Lesson of Carl Schmitt and Robert Steuckers[1]

Without power, righteousness cannot flourish,

without righteousness, the world will flounder in ashes and dust

- Guru Gobind Singh

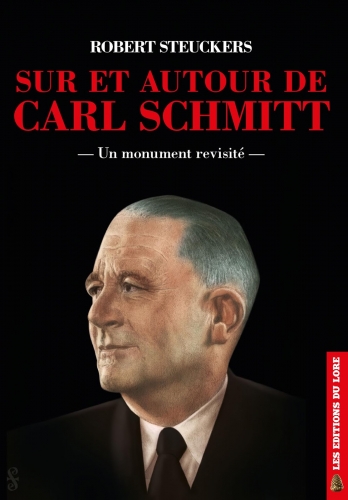

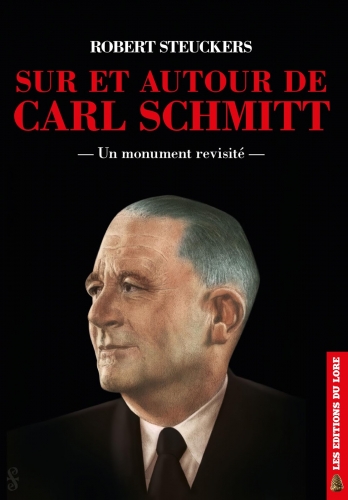

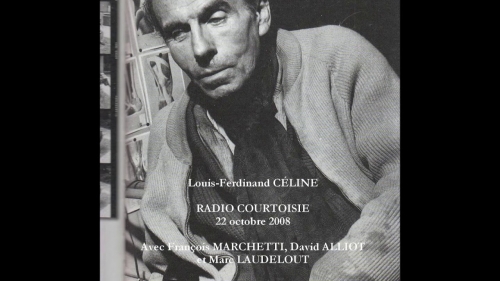

Some aspects of the intellectual heritage of German legal philosopher Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) have already been dealt with by the author in general terms[2] - this essay is meant to look at Schmitt’s scientific oeuvre in more detail. The recent publication of the latest book of Belgian Traditionalist publicist Robert Steuckers affords a suitable opportunity for revisiting Schmitt’ work in a more comprehensive fashion. In the Low Countries, Steuckers’ book Sur et autour de Carl Schmitt represents the first substantial monograph dedicated to the rehabilitation of Schmitt’s highly original - and highly topical philosophy of law.[3] For many years, Schmitt’s intellectual universe and life-world were effectively ‘taboo’ due to his - complex and therefore easily vulgarized - association with the Nazi regime. It is a fact that Schmitt became a member of the NSDAP in May 1933, only a few months after Hitler’s seizure of power, and that he supported Hitler’s authoritarian amputation of the Weimar institutions - as did nearly all other German men and women at the time. It is a fact that he was interned by the American occupation authorities after the downfall of the Third Reich[4] and that he consistently refused to be subjected to the politically correct ‘second baptism’ of semi-obligatory ‘denazification’. His principled stance against foreign occupation cost him his academic career and social status. This stance, however, was not inspired by any great enthusiasm - or even basic respect - for the Nazi regime: in Schmitt’s view, this regime was fatally flawed in terms of higher legitimacy and historical authenticity.[5] After Stunde Null, Schmitt simply refused the new ideological Gleichschaltung demanded by the occupying powers. Irrespective of the exact degree to which Schmitt’s work can be considered intrinsically ‘tainted’ in the context of the virulent excesses of National Socialism, the fact remains that his life’s work was placed in the same post-war quarantine that befell the life work of other great European thinkers. It ended up in history’s cabinet of curiosities, together with that of Italy’s Julius Evola, France’s Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Romania’s Mircea Eliade, Norway’s Knut Hamsun and America’s Ezra Pound.

Some aspects of the intellectual heritage of German legal philosopher Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) have already been dealt with by the author in general terms[2] - this essay is meant to look at Schmitt’s scientific oeuvre in more detail. The recent publication of the latest book of Belgian Traditionalist publicist Robert Steuckers affords a suitable opportunity for revisiting Schmitt’ work in a more comprehensive fashion. In the Low Countries, Steuckers’ book Sur et autour de Carl Schmitt represents the first substantial monograph dedicated to the rehabilitation of Schmitt’s highly original - and highly topical philosophy of law.[3] For many years, Schmitt’s intellectual universe and life-world were effectively ‘taboo’ due to his - complex and therefore easily vulgarized - association with the Nazi regime. It is a fact that Schmitt became a member of the NSDAP in May 1933, only a few months after Hitler’s seizure of power, and that he supported Hitler’s authoritarian amputation of the Weimar institutions - as did nearly all other German men and women at the time. It is a fact that he was interned by the American occupation authorities after the downfall of the Third Reich[4] and that he consistently refused to be subjected to the politically correct ‘second baptism’ of semi-obligatory ‘denazification’. His principled stance against foreign occupation cost him his academic career and social status. This stance, however, was not inspired by any great enthusiasm - or even basic respect - for the Nazi regime: in Schmitt’s view, this regime was fatally flawed in terms of higher legitimacy and historical authenticity.[5] After Stunde Null, Schmitt simply refused the new ideological Gleichschaltung demanded by the occupying powers. Irrespective of the exact degree to which Schmitt’s work can be considered intrinsically ‘tainted’ in the context of the virulent excesses of National Socialism, the fact remains that his life’s work was placed in the same post-war quarantine that befell the life work of other great European thinkers. It ended up in history’s cabinet of curiosities, together with that of Italy’s Julius Evola, France’s Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Romania’s Mircea Eliade, Norway’s Knut Hamsun and America’s Ezra Pound.

But seventy years later it is becoming increasingly evident that the historical-materialist mythology of ‘progress’ and ‘constructability’, now raised to the status of standard doctrine (with a socialist variety in the Eastern Bloc and a liberal variety in the Western Bloc), has brought Western civilization to the brink of extinction. After the fall of Eastern Bloc Realsozialmus, the entire Western world has fallen prey to what may be termed ‘Cultural Nihilism’: a poisonous cocktail of neo-liberal ‘capitalism for the poor and socialism for the rich’ and cultural-marxist ‘identity politics’ (the new ‘class struggle’ of old against young, female against male and black against white). This Cultural Nihilism is characterized by militant secularism (destroying religious cohesion), monetarized social-darwinism (destroying social-economic cohesion), totalitarian matriarchy (destroying family cohesion) and doctrinal oikophobia (destroying ethnic cohesion) and it is practised through the Macht durch Nivellierung (‘power through levelling’) mechanism of the totalitarian-collectivist Gleichheitsstaat.[6] The prime carrier of Cultural Nihilism is still the forever young ‘baby boomer’ generation of rebels without a cause, but that generation is now replacing itself by a time-less, shape-shifting ‘hostile elite’, feeding off continuous new discoveries of ‘repressed minorities’ (resentful feminists, ambitious immigrants, psychotic LBTG-activists). The power of this hostile elite resides in two distinct but intricately linked force fields: (1) the globalist institutional machinery (the ‘letter institutions’ - UN, IMF, WTO, WEF, EU, ECB, NATO) that allows it to overrule state sovereignty and electoral correction and (2) the universalist-humanist discourse of ‘human rights’, ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’ that allows it to monopolize the ‘moral high ground’. This double trans-national and meta-political power position allows the hostile elite to systematically elude any responsibility for the stupendous damage it is inflicting on Western civilization. The crimes committed by the hostile elite - industrial ecocide (anthropogenic climate change, environmental degradation, diabolical bio-industry), hyper-capitalist exploitation (‘free market’, ‘privatization’, ‘social return’), social implosion (matriarchy, feminization, transgenderism) and ethnic replacement (‘asylum policy’, ‘labour migration’, ‘family reunification’) - go unpunished within an institutional and ideological framework that operates literally ‘above the law’. Only an entirely new legal framework can end the legal immunity enjoyed by the hostile elite. Carl Schmitt’s philosophy of law provides that new frame: it offers a restoration of the lost link between institutional law and authentic authority and of what is found between these two - actual justice. To restore this link, Schmitt uses the concept of ‘political theology’, i.e. the assumption that all political philosophies are shaped, directly or indirectly, by theological positions that may or may not take on an ostensibly ‘secularized’ shape. From that perspective, the political imperative of promoting institutional laws aimed at immanent justice is derived from transcendently - theologically - defined authority.

The time has come to end the entirely anachronistic and increasingly untenable ‘taboo’ on Carl Schmitt’s work and thought - and to investigate its relevance during the contemporary Crisis of the Postmodern West.[7] Robert Steuckers’ Sur et autour de Carl Schmitt permits us not only a fascinating visit to a monumental past. It also permits us to find the weapons that are needed in the here and now - it gives us access to the mighty ‘Arsenal of Hephaestus’.[8]

(*) As in the earlier review of Steuckers’ work Europa II,[9] the reviewer has chosen for a double presentation of Steuckers’ original French text - sharp and acidic as usual - as well as an English translation. As stated in that earlier review, the reviewer shares the view of patriotic publicist Alfred Vierling that the French literary culture is essentially different from the English literary culture to a degree that virtually precludes one-on-one ‘translation’. This means that French language skills are actually indispensable for any conscientious studia humanitatis. The lack of such skills among the younger generations of the West, however, is not primarily due to any intellectual complacency: it can be directly attributed to the hostile elite’s anti-education policy of deliberate ‘dumbing down’. The reviewer is therefore willing to meet younger readers half-way by presenting both Steuckers’ original text and his own somewhat ‘free’ English translation. Obviously, the reviewer acknowledges his responsibility for the less successful attempts at transposing Steuckers’ ‘biting’ Walloon-French into English. A glossary of Steuckerian neologisms is added at the end of the text.

(**) This essay is not only meant to provide a review, it is also meant as a metapolitical analysis and a contribution to the patriotic-identitarian deconstruction of the Postmodern Western hostile elite. It is important to know who the enemy is, what he aims at and how he thinks. Carl Schmitt’s life work provides an ‘anatomical’ dissection of the hostile elite’s legal philosophy - it effectively deprives the hostile elite of any authentic foundation. Robert Steuckers has achieved a brilliant rehabilitation of Schmitt’s work - the patriotic-identitarian movement of the Low Countries owes him gratitude and congratulations.

(***) On the one hand, those readers that have still been traditionally educated are asked for patience with the somewhat ‘patronizing’ explanatory notes: these are meant to assist those younger readers that have been deprived of their basic intellectual heritage by decades of anti-education. On the other hand, those readers that lack a traditional education - and that may feel ‘put off’ by any ‘pretentious’ text - are asked for an effort at bettering themselves. They should realize that what may appear ‘pretentious’ reflects, in fact, nothing else than their own stolen heritage - the heritage of Western civilization. If the patriotic-identitarian movement is meant to protect anything of value, then it is exactly that: Western civilization itself - ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ.[10]

1. The World of Normativism as Will and Representation[11]

auctoritas non veritas facit legem

[power, not truth, makes law]

Steuckers commences his extensive overview of the life and work of Carl Schmitt with a reconstruction of the cultural-historical roots of post-war Western legal-philosophical thought. He retraces the historical-materialist reduction - one might say ‘secularization’ - of the Western philosophy of law to the Reformation and the Enlightenment.[12] The religious wars of the 16th and 17th Centuries resulted in the temporary regression of Western civilization into a ‘state of nature’ which could only be partially compensated for by the ‘emergency measure’ of classical Absolutism during the second half of the 17th and the first half of the 18th Century.[13] This ‘emergency brake’ Absolutism is characterized by a highly stylized personification of totally sovereign monarchic power as the last protection of a traditionalist community against the demonic forces of modernist chaos. After the abolition of the old securities of the sacred and feudal order, the ‘absolutist’ monarchs intervene in order to channel the disruptive dynamics of early mercantile capitalism, the incipient civil rights movement and the escalating tendency to religious decentralization. From a cultural-historical perspective, this ultimate resort to ‘hyper-personalized’ Auctoritas can be interpreted as a temporary ‘emergency measure’: ...en cas de normalité, l’autorité peut ne pas jouer, mais en cas d’exception, elle doit décider d’agir, de sévir ou de légiférer. ‘...in normal circumstances, [such an absolute] authority does not play a role, but in exceptional circumstances, it must act in a decisive, over-ruling and legislating fashion.’ (p.4) But this absolutist ‘emergency measure’ is only locally and temporarily effective: the pioneering nations of modernity, such as Great Britain and the Dutch Republic, remain exempt - despite ‘semi-absolutist’ measures such as the Stuart Restoration and the stadtholderate of William III. Even in its heartland, Absolutism reaches its expiry date in less than a century - the American and French Revolutions mark the end of Absolutism and the final Machtergreifung of the bourgeoisie as the new dominant force in the Western political arena.

The bourgeois-capitalist Wille zur Macht is abstractly expressed in a political doctrine that is based on the effective inversion of the preceding Traditionalist philosophy of law (i.e. of the clerical-feudal ‘political theology’): this new Normativism, constructed around bourgeois-capitalist interests, abstractifies and depersonalizes state authority - Thomas Hobbes already describes it as the mythically invisible ‘Leviathan’.[14] Abstractification is achieved through ideologization and depersonalization is achieved through institutionalization: both processes are directed at the foundation and consolidation of the new bourgeois-capitalist hegemony in the political sphere. Rigid routines and mechanical procedures (‘bureaucracy’, ‘administration’, ‘legislation’) replace the human measure and the personal dimension of Traditionalist power: concrete power is replaced by abstract ‘governance’. L’idéologie républicaine ou bourgeoise a voulu dépersonnaliser les mécanismes de la politique. La norme a avancé, au détriment de l‘incarnation du pouvoir. ‘The republican and bourgeois ideology needs to depersonalize the mechanics of politics. It favours normative power over embodied power.’ (p.4) The first consistent experiment with Normativism as Realpolitik ends with the Great Terror of the First French Republic: it illustrates the totalitarian reality that necessarily results from the consistent application of the do-or-die motto that covers the bourgeois-capitalist power project in its formal (republican) as well as its informal (freemasonic) forms: liberté, égalité, et fraternité ou la mort, ‘liberty, equality and fraternity - or death’. The ethical discrepancy between the utopian ideology and the practical application of this power project is ideologically covered by - and established as a norm in - 19th Century Liberalism. Liberalism is the political ‘default setting’ of modernity. The propagandistic surface of Liberalism - its utopia of ‘humanism’, ‘individualism’ and ‘progress’ - covers its deeper substances: the pseudo-scientifically (social-darwinistically) justified economic disenfranchisement (‘monetarization’, ‘free market’, ‘competition’) and social deconstruction (‘individual responsibility’, ‘labour marker participation’, ‘calculating citizenship’) that mathematically result in social implosion (Karl Marx’ Entfremdung and Emile Durkheim’s anomie). In the long term, Liberalism results in a ‘superstructure’ that is based on a very puritanical - and therefore highly resilient - form of Normativism: Liberalism has the highest totalitarian potential of all modernist (historical-materialist) ideologies. Thus, Alexander Dugin historical analysis, translated into English as The Fourth Political Theory, points to the intrinsic - logically-consistent and existentially-adaptive - superiority of Liberalism. ...[L]e libéralisme-normativisme est néanmoins coercitif, voire plus coercitif que la coercition exercée par une personne mortelle, car il ne tolère justement aucune forme d’indépendance personnalisée à l’égard de la norme, du discours conventionnel, de l’idéologie établie, etc., qui seraient des principes immortels, impassables, appelés à régner en dépit des vicissitudes du réel. ‘...[S]till, Liberal Normativism is coercive - it is even much more coercive than the power exerted by any mortal ruler, because it does not tolerate any form of personalized autonomy with regard to its own ‘norm’ (conventional consensus, standard ideology, political correctness), which is elevated to an eternal and unapproachable principle that is permanently exempt from the vagaries of real life’. (p.5) From a sociological perspective, the totalitarian superstructure of Liberal Normativism can be described as ‘hyper-morality’.[15]

The apparently inviolable foundation of the Liberal Normative monolith in the bedrock of Postmodern social psychology raises the question of whether or not it is possible to dislodge by the application of legal philosophy. An affirmative answer to that question depends on breaking through the ‘event horizon’ of Liberal Normative Postmodernity, i.e. stepping beyond its epistemological boundary. A break-out from the ‘timeless’ dimension of Liberal Normativism is by means of an ‘Archaeo-Futurist’ formula: the simultaneous mobilization of re-discovered ancient knowledge and newly discovered strength will provide the necessary combination of imagination and willpower.

2. Through the Glass Ceiling of Postmodernism

ΔΩΣ ΜΟΙ ΠΑ ΣΤΩ ΚΑΙ ΤΑΝ ΓΑΝ ΚΙΝΑΣΩ

[give me a place on which to stand, and I will move the Earth]

- Archimedes

One of the most important childhood diseases of the patriotic-identitarian resistance movement, now rising up against the globalist New World Order throughout the entire Western world, is its inability to correctly assess the nature and power of the hostile elite. The widening (‘populist’) public anger and incipient (‘alt-right’) intellectual criticism that feeds this resistance movement are partially characterized by superficial pragmatism (political opportunism) and emotional regression (extremist conspiracy theories). Both of these phenomena can be understood as the political and ideological reflections of the natural instinct of self-preservation: in a confrontation with direct existential threats, such as the ethnic replacement of the Western peoples and the escalating psychosocial deconstruction of Western civilization, political purity and intellectual integrity simply lack priority. Still, it is of vital importance that the patriotic-identitarian movement outgrows these childhood diseases as quickly as possible - especially its ‘quick fix’ political islamophobia and its ‘shortcut’ ideological anti-semitism.[16] It should be empathically stated that this does not imply any recourse to the kind of ‘preventive self-censorship’ that is now practised by the politically correct journalistic and academic establishment with regard to legitimate cultural-historical questions that are embedded within the larger discourses of ‘islamophobia’ and ‘anti-semitism’. The patriotic-identitarian movement is bound to prioritize authentic - not merely legalistic - freedom of expression: it is bound to the position that politically correct (self-)censorship and repressive media policies are counter-productive because they increase public distrust and because they feed political extremism. The obvious ‘pride and prejudice’ of the system press (which stigmatizes every rational cost-benefit analysis of ‘mass-immigration’, ignores the ethnic profiles of ‘grooming gangs’ and re-interprets incidents of islamist terror) and the governmental policy of ‘shoot the messenger’ with regard to critical media (through ‘fake news’ projections, ‘Russian involvement’ smear campaigns and digital ‘deplatforming’) have caused the public to abandon the journalistic and political ‘mainstream’. The downfall of the traditional (paper and television) media and the splintering of the political landscape merely represent the surface reflections of this development. Now it is up to the patriotic-identitarian movement to lead the defence of the old freedoms of press and opinion, freedoms that have been now been discarded by the hostile elite as superfluous - and dangerous.[17] The task of defending Western civilization, which has been sold out by the neo-liberals and betrayed by the cultural-marxists, has now devolved upon the patriotic-identitarian movement. A correct assessment of the nature and power of the hostile elite is now its highest priority - without it, a winning strategy is impossible. A short-cut identification of the ‘enemy’ as ‘the Islam’ or a ‘Jewish world conspiracy’ simply does not stand up to cold calculus and ruthless realism required from this assessment.

The correct identification of the hostile elite requires more than a simple - albeit ethically and existentially correct - reference to its undeniably ‘demonic’ quality. The absolute evil that results from industrial ecocide, bloodthirsty bio-industry, neo-liberal debt slavery and matriarchal social deconstruction is self-evident.[18] But more is needed: it is necessary to achieve a legal understanding and a political strategy that ‘frames’ the hostile elite in a definitive manner. In this regard, Robert Steuckers’ analysis of Carl Schmitt’s ‘political theology’ is of great value: it offers the intellectual tools that are necessary to complete this - possibly greatest - task of the Western patriotic-identitarian movement.

3. Liberalism as Totalitarian Nihilism

...le libéralisme est le mal, le mal à l’état pur, le mal essentiel et substantiel...

[...liberalism is evil, evil in its purest form, evil in essence and substance...] (p.37)

Steuckers analyzes Liberal Normativism as the ‘default ideology’ of the hostile elite, i.e. the ideology that ultimately legitimizes its hold on power: Le libéralisme... monopolise le droit (et le droit de dire le droit) pour lui exclusivement, en le figeant et en n’autorisant plus aucune modification et, simultanément, en le soumettant aux coups dissolvants de l’économie et de l’éthique (elle-même détachée de la religion et livrée à la philosophie laïque) ; exactement comme, en niant et en combattant toutes les autres formes de représentation populaire et de redistribution qui s’effectuait au nom de la caritas, il avait monopolisé à son unique profit les idéaux et pratiques de la liberté et de l’égalité/équité : en opérant cette triple monopolisation, la libéralisme et son instrument, l’Etat dit ‘de droit’, prétendant à l’universalité. A ses propres yeux, l’Etat libéral représente dorénavant la seule voie possible vers le droit, la liberté et l’égalité : il n’y a donc plus qu’une seule formule politique qui soit encore tolérable, la sienne et la sienne seule. ‘Liberalism monopolizes (1) the law (and the right to legislate) by [permanently] setting its boundaries, by not allowing for any fundamental adaptations and by exposing it to the ‘dissolving’ effects of [an uncontrolled] economy and [borderless] ethics (ethics that escape any religious framework and are hijacked by ‘secular philosophy). By denying and sabotaging all other forms of (2) [non-party political] representation and (3) [non-monetarized economic] redistribution for the sake of its own exclusive profits, liberalism also monopolizes the [entire] ideal and practical [discourse] of freedom, equality [and] fairness. Through this triple monopoly [and] through its state-enforced ‘legal order’, liberalism is able to claim [an absolute] universal validity. In its own eyes, the liberal state represents the sole possible [and sole redeeming] way to achieve law, freedom and equality. Thus, only one acceptable political formula remains: liberalism - and liberalism alone.’ (p.38) This is the background on which neo-liberal globalism is able to project ‘universal’ and ‘absolute’ values such as ‘good governance’ and ‘human rights’. From a Traditionalist perspective, Liberal Normativism as defined by Steuckers represents the political and ideological ‘infrastructure’ that reflects the higher but intangible cultural- and psycho-historical ‘superstructure’ that was here earlier defined as ‘Cultural Nihilism’, viz. the experiential reality that is pre-conditioned by social-economic Entfremdung, psycho-social anomie, urban-hedonist stasis and collectively-functional malignant narcissism.[19] This Traditionalist perspective fits seamlessly into Steuckers’ analysis of the tangible cultural-historical effects of Liberal Normativism. Steuckers explicitly describes Liberal Normativism as ....[le] principe dissolvant et déliquescent au sein de civilisation occidentale et européenne. ...[L]e libéralisme est l’idéologie et la pratique qui affaiblissent les sociétés et dissolvent les valeurs porteuses d’Etat ou d’empire telles l’amour de la patrie, la raison politique, les mœurs traditionnelles et la notion de honneur... ‘...[t]he ‘dissolving’ principle and ‘rot’ in the heart of Western and European civilization. ...[L]iberalism represents the ideology and practice that most effectively weakens communities and that most effectively dissolves the values on which state[s] and empire[s] are build: love of country, responsible statesmanship, traditional loyalty and authentic honour.’ (p.36-7)[20]

From a Traditionalist perspective, the cultural-historical effects of Liberal Normativism are determined by larger meta-historical dynamic, i.e. the downward time spiral that Hindu Tradition interprets as Kali Yuga and that the Christian Tradition interprets as ‘Latter Days’. The historical agency of Liberal Normativism as a carrier of a contextually functional Wertblindheit is explicitly recognized in Steuckers’ prognosis: ...une ‘révolution’ plus diabolique encore que celle de 1789 remplacera forcément, un jour, les vides béants laissés par la déliquescence libérale ‘...[it is] inevitable that, someday, an even more [openly] demonic revolution than that of 1789 will fill the gaping void that has been caused by the liberal rot.’ (p.37) A first indication of the deeper ‘outer dark’ that still lies hidden beyond the Liberal Normativist facade is found in the recent monster alliance between neo-liberalism and cultural-marxism in Western politics (in Dutch politics this alliance is visible in the program of the governing coalition parties, which combines the ‘disaster capitalist’ agenda of the VVD and the ‘deep nihilist’ agenda of the D66).[21] Steuckers highlights Schmitt’s doubly philosophical and theological interpretation of the regressive cultural-historical tendency of Liberal Normativism. Schmitt draws attention to the consistent Liberal-Normativist support for pre-Indo-European primitivism (Etruscan matriarchy, Pelagianist ‘katagogic’ theology) at the expense of Indo-European civilization (Roman patriarchy, Augustinian ‘anagogic’ theology).[22] Traditionalism associates this tendency with a meta-historical movement towards a ‘neo-matriarchy’: this explains the chronological relation between the Postmodern hegemony of Liberal Normativism and typically Postmodern symptoms such as feminization, xenophilia and oikophobia.[23] In sociological terms, this phenomenology can be accurately described as befitting the development of a ‘dissociative society’.[24] The spectre of an absolute nihilist void is already casting ahead its shadow in Postmodern discourses such as ‘open borders’ (genocide-on-demand), ‘transgenderism’ (depersonalization-on-demand), ‘reproductive freedom’ (abortion-on-demand) and ‘completed life’ (euthanasia-on-demand) - discourses that are straightforwardly demonic in any authentic Tradition.[25]

Leaving aside the natural interethnic (effectively ‘neo-tribal’) conflicts of contemporary ‘multicultural societies’ (conflicting bio-evolutionary strategies, interracial libido trajectories, post-colonial inferiority complexes), the prime trigger of the existential conflict between indigenous Westerners and non-Western immigrants is found in the increasingly diabolical life-world of Liberal-Normativist Western ‘society’. For every traditional Muslim from the Middle East, for every traditional Hindu from South Asia and for every traditional Christian from Africa the Liberal-Normativist ‘open society’ or the Postmodern West not only an abstract (theological) evil but also a lived (experiential) horror. Even if the armed terror of the islamicist jihad is (a tolerated) part of the offensive ‘divide and rule’ strategy of the hostile elite in form, in substance it can also be understood as a defensive mechanism against the blasphemous and dehumanizing experience of life under Liberal-Normativist rule. From a Traditionalist perspective, it could be said that for the Western peoples an Islamic Caliphate would, in fact, represent a (very relatively) ‘better’ alternative to the bestial dehumanization that will logically result from the ‘harrowing of hell’ of fully-implemented Liberal Normativism.

Thus, the greatest enemy of all the Western peoples - in fact, the common enemy of all peoples that still live according to authentic Traditions - is politically identified: totalitarian-nihilist Liberalism. Liberal Normativism is politically realized through Liberalism: the program of the hostile elite is shaped by Liberalism. In this regard, it is important to note the fact that, since the Second World War, Liberalism has gradually gained the status of ‘standard political discourse’. Liberalism has infiltrated, disfigured and transformed its political rivals, including Christian Democracy (the Dutch CDA and CU, which have joined the liberal governing coalition without the slightest compunction), Social Democracy (the Dutch PVDA and SP, which have been marginalized through decades of compromise) and Civil Nationalism (the Dutch PVV and FVD, which have failed to formulate a viable alternative vision of society). This process has advanced to point of eradicating any trace of authentic democratic-parliamentarian opposition in key areas such as economic and social policy. Steuckers views this process of ‘politicide’ as a function of Liberalism’s intrinsic power of ‘ideological sterilization’. Even outside of the core party cartels (in the Netherlands these are represented by standard ‘governing parties’ of VVD, D66, CDA, CU and PVDA) Liberalism has become a political habitus[26] - all other parties automatically (largely unintentionally) take on the role of ‘controlled opposition’. The result is ‘mainstream politics’ (in the Netherlands it is explicitly referred as the all-levelling ‘polder model’), now dominating the entire West since the 1980’s rise of ‘Neo-Liberalism’: the rise to power of Margaret Thatcher in Britain, Ronald Reagan in America and Ruud Lubbers in the Netherlands.

4. Liberalism as Politicide

A ‘democratically elected’ parliament can never be the place for authentic debate:

it is always the place where collectivist absolutism issues its decrees.

- Nicolás Gómez Dávila

The formation of Liberalist-led party cartels and Liberalist-guided consensus politics is largely due to the simple practice of parliamentarism: the parliamentary technique of the hyper-democratically dumbed-down and hyper-regulated unrealistic ‘debate’ reduces all ‘opinions’ and ‘viewpoints’ to their lowest common denominator, which is always found in grossly materialist and totally amoral Liberalism. The all-levelling debate replaces quality with quantity (‘democracy’), thought with feeling (‘humanism’), concrete justice with abstract governance (regulation, bureaucracy, protocol) and collective future planning with individual impulse gratification. ‘Purchasing power’ always outweighs generational legacy, ‘lifestyle’ always prevails over ecological sustainability and ‘relationship experiments’ always have priority over family life. Parliamentarism is nothing but the political and institutional reflection of the collectivist levelling sentiment that underpins bourgeois Liberalism: it represents the reductio ad absurdum of politics - politics as talk show entertainment.[L]’essence du parlementarisme, c’est le débat, la discussion et la publicité. Ce parlementarisme peut s’avérer valable dans les aréopages d’hommes rationnels et lucides, mais plus quand s’y affrontent des partis à idéologies rigides qui prétendent tous détenir la vérité ultime. Le débat n’est alors plus loyal, la finalité des protagonistes n’est plus de découvrir par la discussion, par la confrontation d’opinions et d’expériences diverses, un ‘bien commun’. C’est cela la crise du parlementarisme. La rationalité du système parlementaire est mise en échec par l’irrationalité fondamentale des parties. ‘[T]he essence of parliamentarism is found in debate, discussion and publicity. Such parliamentarism may prove itself an asset in an Aeropagus [assembly][27] of rational and clear-minded gentlemen, but this is no longer the case when rigidly ideological parties are confronting each other with claims of possessing the ultimate truth. The latter debate is no longer loyal: the aim of its participants is no longer the discovery of the ‘higher cause’ through a discussion and an exchange of opinions and experiences. Herein lies [the cause of] the crisis of [comtemporary] parliamentarism. The rationality of the [present] parliamentary system fails due to the fundamental irrationality of the parties.’ (p.18-9)

It is inevitable that this self-reinforcing crisis is increasingly fed by groups that were previously ‘invisible’ in the political landscape. The escalating process of political levelling is fed by the individual ambitions and resentments of the self-appointed ‘representatives’ of supposedly ‘discriminated’ groups. Seek and you shall find: there are always more ‘under-privileged’ groups (to be invented): young people, old people, women, immigrants, homosexuals, transgenders. Totalitarian nihilist Liberalism is the deepest (maximally ‘deconstructed’, maximally ‘desubstantivized’ political sediment - and sentiment - that results from this implosive process: it is the political ‘zero position’ that remains after the all-levelling ‘debate’, i.e. after the neutralization of all attempts at political idealism, political intelligence and political willpower.

Liberalism realizes the political (parliamentarist, partitocratic) dialectics of the Liberal-Normativist ideology. In Schmitt’ view, the dialectically vicious circle that results from this ideology can only be broken by a fundamental restoration of political authority. Steuckers states this as follows: Dans [cette idéologie], aucun ennemi n’existe : évoquer son éventuelle existence relève d’une mentalité paranoïaque ou obsidionale (assimilée à un ‘fascisme’ irréel et fantasmagorique) - ...il n’y a que des partenaires de discussion. Avec qui on organisera des débats, suite auxquels on trouvera immanquablement une solution. Mais si ce partenaire, toujours idéal, venait un jour à refuser tout débat, cessant du même coup d’être idéal. Le choc est alors inévitable. L’élite dominante, constituée de disciples conscients ou inconscients de [cette] idéologie naïve et puérile..., se retrouve sans réponse au défi, comme l’eurocratisme néoliberal ou social-libéral aujourd’hui face à l’[islamisme politique]... De telles élites n’ont plus leur place au-devant de la scène. Elles doivent être remplacées. ‘In [this ideology] a [real] enemy cannot be conceived of: even to suggest the possible existence of such an [enemy] is ‘proof’ of the paranoid or obsessive mentality (always associated with an unreal and imaginary ‘fascism’) - ...there are only ‘debating partners’. With [such partners] debates are organized and these debates always end in a solution. But if, one day, this partner - always thought of in abstract terms of rational perfection - would actually refuse the debate, then the ideal [‘discussion’ model] would immediately fail. An [existential] shock would be inevitable. The ruling elite, which is [entirely] made up of conscious and unconscious adherents to [this utterly] naive and infantile ideology..., would have no answer to this challenge - in the same manner that neoliberal and social-democrat eurocrats [have no answer] to [political islamism]... Such elites do not deserve a place on the [political] stage - they have to be replaced.’ (p.245)

5. Liberalism as Anti-Law and Anti-State

A Marxist system can be recognized by its protection of criminals

and its criminalization of opponents.

- Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Sometime during the aftermath of the Machtergreifung of the soixante-huitards the hostile elite has taken the strategic decision to replace the indigenous peoples of the West.[28] Its underlying logic is as clear as it is ruthless. The European peoples have proven to be historically incompatible with Modernity, as it is defined by Culture Nihilism: this is why they have to be mixed with and replaced by more malleable - less intellectual, less demanding, less self-conscious - slave peoples. The European peoples are demographically infertile under totalitarian dictatorship, they are economically unproductive in urban-hedonist stasis and they are politically unreliable in debt slavery.[29] But the ethnic replacement of the Western peoples is a project with considerable risks: even the most optimally calibrated Umvolkung recipe and the most carefully calculated dosage of its various ingredients (mass immigration, ethnically selective natalist policy, affirmative action, native economic deprivation) demand a political balancing act of unparalleled refinement. To achieve the political ‘point of no return’ (the demographically-democratically checkmate of the Western peoples) the hostile elite runs the risk that its amputation-transplantation operation will fail when the double psychological and spiritual anaesthesia fails, causing the patient to awake on the operating table. Until that point is reached, the expiry date of the hostile elite depends on two main anaesthetic medicines: (1) the hedonist-consumerist defined level of ‘wealth’ and ‘wellness’ and (2) the educative-journalistic manipulated politically correct consensus. If one of these two elements fall under a certain critical measure (a measure that is gradually revised downward), the danger of the patient awakening increases exponentially. Thus, a certain minimum remnant (constantly revised downward as well) of the welfare state, labour legislation, political pluriformity and freedom of opinion must be maintained until the process of ethnic replacement has been completed. The neoliberal-globalist ideals of entirely ‘open borders’, of an entirely amoral ‘open society’ and a total social-economic bellum omnium contra omnes can only be fully realized after the ethnic replacement project has reduced the native Western population to the status of ‘endangered species’, confined to marginal ‘reservations’. Until that time, the transition process creates a legal predicament for the hostile elite: it has to carefully manage the maximum speed with which Western state institutions and laws can be demolished and replaced with Liberal anti-state institutions and anti-laws. If this demolition and replacement take place too quickly, the Liberal anti-state risks an uncontrollable backlash: an early overdose of chaos and injustice in the public sphere risks a premature alienation and collective countermovement among the native Western populace.

The increasingly grotesque side-effects of the Liberal demolition of state institutions and legal safeguards are particularly problematic in case of those privileges that are the exclusive preserve of the ‘immigrants’ (‘affirmative action’, ‘preferential treatment’, ‘housing priorities’, ‘targeted subsidies’) and of those sanctions that are explicitly aimed at the natives (student loans, commercial credit and administrative fines for natives vs. scholarships, grants and prosecution dismissal for ‘immigrants’). The contrast between the bureaucratic hurdles, fiscal pressure, labour market congestion and housing shortages faced by the native population (particularly its unfortunates: the homeless, the infirm, the poor) and the red carpet treatment (free legal assistance, free shelter and free money followed by priority housing, start-up facilities and full access to social support) provided to foreign colonists (including masses of fraudsters, thieves and rapists) is becoming more grotesque every year. As the immigrant population explodes due to ‘managed migration’ (‘Marrakesh’),‘family reunification’ (‘human rights’) and ‘child allowances’ (‘legal equality’) - always at the expense by the native population - the hostile elite risks pushing the native population into electoral resistance (‘populist parties’) and civil disobedience (gilets jaunes) too soon and too far. The hostile elite is attempting to abolish the historical gains of 150 years of Western civilization - legal recourse, labour law, social security, educational opportunity, universal healthcare, administrative integrity, responsible governance - in the space of no more than two generations. Here, the generational divide (essentially the divide between baby-boomer and post-baby-boomer) is essential because it is vitally important to ‘clean’ the collective memory of the Western populace: to make sure that inconvenient concepts such as ‘educational standards’, ‘living wage’, ‘income security’, ‘old age insurance’ and ‘justice for all’ are eradicated as quickly as possible. The hostile elite is close to achieving this aim, even if it is not fully ‘in the clear’ yet.

The Liberal anti-state and anti-law of the hostile elite has already basically reduced its hardworking, conscientious and naive indigenous subjects to ‘milk cows’ and ‘slaughter cattle’ to be exploited on behalf of a rapidly increasing mass of ruthless, unproductive, fraudulent and criminal ‘immigrants’. The sickening burden of this colonizing immigration is particularly crushing for the most vulnerable indigenous groups: day labourers, small entrepreneurs, pensioners, the physically and mentally handicapped and single-parent families. The hostile elite is silencing their feeble protests against demographic inundation and social-economic marginalization with mind-twisting and utterly cynical one-liners such ‘multicultural enrichment’ and ‘humanitarian duty’, ‘market forces’ and ‘private responsibility’. In the Dutch context, their situation is best symbolized by a caricature picture that is now frequently becoming reality: the humble indigenous bicyclist who is stopped in the pouring rain by the traffic police to be fined for a defect light, when a few yards away an ‘immigrant’ drugs lord is speeding through the red light in his sports car on the way to launder his ill-gotten riches in the ‘convenient store’ of his family clan.

But worse is yet to come - and many are starting to experience this ‘in the flesh’. Worse is the experience of indigenous girls and women: with the clients of their ‘lover boys’[30] during their school years, with their ‘rapefugee’ stalkers during their college years and with their ‘#metoo’ affirmative action ‘bosses’ during their working lives. And the worst is hidden still: the murderous decolonization (Lari 1953, Algiers 1956, Stanleyville 1964, Kolwezi 1978, Air Rhodesia Flight 827 1979) and the postcolonial atavism (Macías Nguema in Equatorial Guinea 1968-79, Muammar Kaddafi in Libya 1969-2011, Idi Amin in Uganda 1971-79, Pol Pot in Cambodia 1976-79, Saddam Hussein in Iraq 1979-2003) of the Third World bode ill for the future of the remnant native population of the West once it is fully colonized by primitive Africans and resentful Asians. Perversion is already the becoming the standard modality of Western bureaucracies and judiciaries as the indigenous Western peoples are abandoned and left to face terrorism, criminality and persecution without effective recourse. They are left with a toothless police that is caught up in red tape, a matriarchal anti-judiciary that is protecting criminals against victims, a silent media cartel that is hiding the ‘colour of crime’[31] and a perverted political system that prioritizes ‘public perception’ over public responsibility. These collective experiences, however, are now fast accumulating into a critical mass that threatens the whole ethnic replacement: they are, in fact, creating space for an effective collective challenge to the hostile elite. The moral legitimacy of the native resistance is giving it the status of an ‘Authority in the Making’, empowering it to tear up the seemingly inescapable but wholly fraudulent ‘IOU from history’ that the hostile elite is foisting on the Western peoples. The traffic light of history is flashing yellow for Liberalism. The gilets jaunes have already shown the Liberal hostile elite the ‘yellow card of history’: it is now up to the Western peoples to write out its red card - and to transfer it from the political stage to the penalty box of history.

6. The Patriotic-Identitarian Resistance as Authority in the Making[32]

And that, knowing the time, that now it is high time to awake out of sleep:

for now is our salvation nearer than when we believed.

The night is far spent, the day is at hand:

let us therefore cast off the works of darkness,

and let us put on the armour of light.

- Romans 13:11-12

The basis of a successful campaign of Liberal Normativism as an ideological model and of Liberalism as a political force is the realization that both are the mortal enemies of Western civilization. For the Western peoples, the annihilation of Liberalism as a political force is an absolute precondition for a successful reconquista of state sovereignty and ethnic identity. In this case, the absolute right of survival coincides with the ethical imperative of resistance. This ethical imperative applies to all nations with ‘their back against the wall’, as formulated by Marek Edelman, the last leader of the Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa (‘Jewish Combat Organization’): We knew perfectly well that we had no chance of winning. We fought simply not to allow the Germans alone to pick the time and place of our deaths. We knew we were going to die.[33]

In this regard, the Western patriotic-identitarian movement would be well advised to take to heart what Steuckers has to say about the illusion of ‘dialogue’ with the hostile elite. Reasonability and dialogue end - have to end - when one is faced with an existential threat: ...l’ennemi n’est pas bon car il veut ma destruction totale, mon éradication de la surface de la Terre: au mal qu’il représente pour moi, je ne peux, en aucun cas et sous peine de périr, opposer des expressions juridiques ou morales procédant d’une anthropologie optimiste. Je dois être capable de riposter avec la même vigueur. La distinction ami/ennemi apporte donc clarté et honnêteté à tout discours sur le politique. ‘...the enemy simply cannot be good, because he seeks my total destruction [and] my eradication from the face of the Earth: I cannot, when faced with the [absolute] evil that he represents to me, apply the legal and moral prescriptions of [a misguided] anthropological optimism - if I do so, I will become extinct. I must be able to retaliate with equal vigour. Thus, the distinction between friend [and] enemy provides the political discourse with clarity and honesty.’ (p.51)

The hostile elite, which speaks through Liberal Normativism and which acts through Liberalism, has declared war on the Western peoples and on Western civilization: the Western peoples are simply left with no other choice than to fight for their lives and to appoint a newly-legitimate ‘authority in the making’. The weapons with which the Western patriotic-identitarian resistance can deal the intellectual deathblow to the hostile elite can be found in the arsenal of Carl Schmitt - Robert Steuckers’ Sur et autour provides the key to this arsenal. One of the weapons to be found there is Schmitt’s philosophical validation of the restoration of authentic Auctoritas.

7. Decisionism as State Theory

In Gefahr und grosser Noth

Bringt der Mittel-Weg den Tod

[In danger and distress

The middle way leads to death]

- Friedrich von Logau

The weakness of the hostile elite’s pseudo-philosophy of law is ruthlessly exposed in Steuckers’ analysis of Schmitt’s basic notions of the inevitably concrete and personal dimension of all authentic forms of legitimate law and power. The concrete and personal dimensions of law and power are best illustrated in its unavoidable incarnation in the person of the judge: the person of the judge bridges the gap between abstract and historically determined law (legal code, jurisprudence) and the concrete and contemporary reality (event, circumstance). La pratique quotidienne des palais de justice, pratique inévitable, incontournable, contredit l’idéal libéral-normativiste qui rêve que le droit, la norme, s’incarneront tous seuls, sans intermédiaire de chair et de sang. En imaginant, dans l’absolu, que l’on puisse faire l’économie de la personne du juge, on introduit une fiction dans le fonctionnement de la justice, fiction qui croit que sans la subjectivité inévitable du juge, on obtiendra un meilleur droit, plus juste, plus objectif, plus sûr. Mais c’est là une impossibilité pratique. ‘The daily, inevitable and undeniable practice of due legal process contradicts the Liberal-Normativist illusion that laws and norms can [somehow] be realized without a flesh-and-blood intermediary. By imagining an ‘absolute law’ that eliminates the person of the judge, it introduced a legal fiction: a fiction that proposes a better, more just and more objective law without the inevitable subjective [mediation of the] judge. But, [of course,] no such thing is possible in practice.’ (p.5-6) No legal verdict can be conceived of without the physical presence of a Vermittler, i.e. a man of flesh and blood who is - consciously or unconsciously - shaped by values and sentiments. Thus, no legal order can be conceived of without the imprint of the specific (historically and contextually experienced) charisma of the judge. In the Postmodern context, this charisma will tend to be of a collectivist-tainted, resentment-fed and downward-directed negative nature. Parce qu’il y a inévitablement une césure entre la norme et le cas concret, il faut l’intercession d’une personne qui soit une autorité. La loi [et] la norme ne peu[vent] pas s’incarner toute[s] seule[s]. ‘Because there will always be a gap between the [abstract] norm and the concrete [case], mediation by personalized authority is a necessity. [Thus,] the law [and] the norm can never incarnate themsel[ves].’ (p.6) The same concrete and personalized dimension apply with regard to political power: the entirely abstract, institutionalized and bureaucratized form of political power that is wished for, believed in and aimed at my Liberal Normativism is simply impossible. Thus, the inevitable and indispensable incarnation of political authority remains ...le démenti le plus flagrant à cet indécrottable espoir libéralo-progressisto-normativiste de voir advenir un droit, une norme, une loi, une constitution, dans le réel, par la seule force de sa qualité juridique, philosophique, idéelle, etc. ‘...the most definitive argument against the incorrigible liberal-progressivist-normativist hope that it will be possible, one day, to achieve a real-world law, norm [and] order that is solely based on judicial, philosophical and idealist quality.’ (p.6)

Under the aegis of totalitarian Liberal Normativism, however, Postmodern West politics has no longer any space for rational debate and superior argumentation: only ‘might is right’. L’idéologie républicaine ou bourgeoise a voulu dépersonnaliser les mécanismes de la politique. La norme a avancé, au détriment de l‘incarnation du pouvoir. ‘The republican and bourgeois ideology is aimed at the depersonalization of the mechanics of politics. It favours normative power at the expense of personalized power.’ (p.4) The contemporary power of Liberal Normativism is psychosocially anchored in an anti-rational matriarchal conditioning that abolishes all personalized forms of authentic authority in a hyper-collectivist règne de la quantité.[34] Dramatic illustrations of this increasingly oppressive matriarchal reality can be found in the Western European ‘ground zero’ of Postmodernity: in the ex-nation states of ‘Anti-Frankrijk’ en ‘Anti-Germany’ the policies of anti-tradition, anti-nationalism and anti-masculine are now metastasizing into openly sadomasochistic projects of self-mutilating and suicidal Umvolkung à l’outrance. In this context, every form of collectivist resistance (parliamentary ‘opposition’ and extra-parliamentary ‘activism’) against the idiocratic and absurdist excesses of Liberal Normativism is doomed to failure because it will limit itself to pragmatic ‘symptom management’. By limiting themselves to the matriarchal-collectivist (doubly politically-institutional and psycho-social) ‘frame’ of Liberal Normativism, such parliamentary opposition (the AfD in Germany, the FvD in the Netherlands) and such extra-parliamentary activism (the Reichbürger movement in Germany, the gilets jaunes movement in France[35]) are effectively reduced to ‘lightning conductors’. There exists only one true remedy for the matriarchal-collectivist ‘anti-authority’ of Liberal Normativism: patriarchal-personalized authority as defined in Traditionalist Decisionism.

The Decisionist approach to law and politics is always concrete, and therefore also physical and personal. In legal-philosophical terms, it is primarily concerned with the physical protection of the concrete (geographically and biologically bounded) realities of state and ethnicity. In Decisionism, earthly realities always take priority over abstract norms: ist erdhaft und auf Erde bezogen [the law is earth-bound and refers to earthly reality]. In metapolitical terms, it proceeds from the recognized necessity of personalized authority in order to meet physical calamities as well as overdoses of ‘normative’ power. It sanctions personalized authority for the effective management of existential threats against the state and the people: Ausnahmezustand, ‘state of emergency’, Ernstfall, ‘case of emergency’, Grenzfall, ‘borderline case’. This highest command authority is based on the (temporary) suspension (in fact: correction) of (normative) law through its (temporary) personification: this emergency measure is applied whenever the legal order, the power of the state or the survival of the nation are undermined or shaken. ...[E]n cas de normalité, [cet] autorité peut ne pas jouer, mais en cas d’exception, elle doit décider d’agir, de sévir ou de légiférer. ‘...[U]nder normal circumstances, th[is] authority stands outside daily life, but in case of emergency it is obliged to act, to rule and to legislate [directly].’ (p.4) This ‘emergency power’ kicks in case of existential threats from without (natural disaster, enemy invasion) and from within (rebellion, treason). In Traditional societies, this personalized authority is permanently (institutionally) available in the ‘reserve functionality’ of sacred office. In pre-modern Western societies, this reserve functionality is institutionally represented in the Monarchy, regulated either through election or succession. The sacred nature of the highest command authority is derived from the transcendental (and therefore anagogical) concept of state and nation that prevailed in all pre-modern societies. Carl Schmitt’s philosophy of law - inspired by the Traditionalist-Catholic state theory of Donoso Cortés[36] - retains this sacred element in its transcendental definition of a holistically conceived unity of state, nation and society. This unit, as qualified through the ancient notions of Unitas Ordinis, ‘Unified Order’, Societas Civiles, ‘Civil Society’ and Corpus Mysticum, ‘Mystical Body’, is taken to represent a creation that is naturally organic as well as divinely ordained - as such it can never be wholly encompassed by any political institution. The man that fate has called upon to defend the life of this mysterious ‘creature’ is held to be imbued with a sacred vocation of the highest order.

Thus, from a Traditionalist perspective, the state-nation-society agglomerate constitutes a living organism and a historical community with a mystical destiny that constitutes a political a priori: politics should be shaped around its needs and interests and politics serves it. ...[L]e peuple... n’est pas chose formée (par une volonté humaine et arbitraire) mais fait empirique et n’est jamais ‘formable’ complètement; il restera toujours de lui un résidu rétif à tout formatage, un reste qui échappera à la volonté de contrôle des instances dérivées de certaines ‘Lumières’... [L]a souveraineté populaire ne peut être entièrement représentée (par des députés) car alors une part plus ou moins importante de sa présence concrète est houspillée hors des institutions de représentation, lesquelles ne représent[e]nt plus que les intérêts ou des réalités fragmentaires. ‘...[T]he people... is not a ‘construct’ (to be made and unmade according to human will), but rather an empirical given fact that can never be entirely ‘malleable’ [in a political sense]: it always retains an indivisible residue that resists [all attempts at] ‘construction’ - a residue that remains intangible in terms of the kind of institutional control that derives from ‘Enlightenment’ [thought]... [N]ational sovereignty [and electoral mandates] can never be entirely representative through ‘representation’, because a [certain] - larger or smaller - part of the concrete presence [of the nation] will always be excluded from institutional representation, [because such a representation] will be inevitably focussed on fragmentary interest and realities.’ (p.33) The Traditionalist definition of the state-nation-society agglomerate is found in the vision of ... la ‘nation unie’, non mutilée par des dissensions partisanes, donc une nation tournant ses forces vives vers l’extérieur, et non pas vers sa seule sphère interne en y semant la discorde et en y désignant des ennemis, provoquant à terme rapide l’inéluctable implosion du tout. La Nation comme l’Eglise doit être un coïncidentia oppositorum : elle doit faire coïncider et s’harmoniser toutes les forces et différences qui l’irriguent, en évitant les modi operandi politiciens qui sèment les dissensus et ruinent la continuité étatique... ‘...the ‘unified nation’, undivided by partisan strife - a nation that directs its vital force outwards, and not merely inwards, where [that force] will create frictions and factions, results in inevitable and early total implosion. As in the case of the Church, the Nation is called upon to constitute a coïncidentia oppositorum: it must focus all [its] powers and harmonize the differences that feed its growth. It must avoid all politicized modi operandi - [factional divides and party-political narrow-mindedness] - that would cause [societal] friction and that would endanger the continuity of its state [sovereignty]...’ (p.38)

From this follows the double theological and legal imperative of a trans-democratic and trans-secular state authority which is simultaneously open in a downward (earthly) and upward (heavenly) direction and which guarantees the historical continuity of the nation(s) that it represents. A built-in permanent Decisionist ‘reserve option’ - a (temporal) ‘dictatorial’ command structure to deal with the Ernstfall - is an indispensable part of this state authority. Within the Traditionalist philosophy of law of the Christian world this reserve option is always ‘framed’ - and limited - by the higher transcendental principle of Caritas, which is explicitly expressed in the key principles of Catholic politics: Community, Solidarity and Subsidiarity. Caritas: the ‘anthropologically pessimistic’ Christian ethical imperative and pious practice of magnanimity with all creatures that need protection and assistance. First and foremost these are those people that are vulnerable, incapacitated or weak-minded - children, women, the poor, the sick, the handicapped and the dying. But these are also the animals and plants that cannot speak up for themselves and that are subject to man’s dominion. Noblesse oblige. In the Traditionalist philosophy of law of the Christian world the Monarchy was the highest natural and legitimate carrier of Decisionistically defined Auctoritas: ...les familles royales, qui incarnent charnellement les Etats dans l’Ancien régime, offrent de successions de monarques, différents sur le plan du caractère et de la formation, permettant une plus grande souplesse que les régimes normatifs et normateurs. Elles permettent la continuité dans l’adaptation et le changement, apportés par les héritiers de la lignée. En ce sens, les monarchies constituent des contrepoids contre le déploiement purement technique de la raison normative, qui fait basculer les Etats dans l’abstraction et apportent, in fine, la dictature. ‘...royal families - which are made to literally embody the state during the [Absolutist] ancien régime - offer a [continuous] succession of [ever new generations of] monarchs differ in character, upbringing and education: they offer a [‘built-in’ and] much greater flexibility than ‘normative’,... [democratically liberal] regimes. In this sense, monarchies offer a counterbalance against the purely ‘technocratic’ rule of normative ‘reason’ that reduces states to legal abstractions and, eventually, to [normative] dictatorships.’ (p.36) In a Monarchy the principle of Subsidiarity postulates an additional and derivative role for other ‘privileged’ institutions as well: the Clergy and the Nobility are called upon to carry many responsibilities - they are burdened with a secondary Decisionist Pflicht zur Tat, or ‘obligation to act’. All of these Traditional institutions were assumed to take on a number of natural and legitimate obligations on the basis of an existential quality that is simply unimaginable under the aegis of Liberal-Normativist modernity - a quality that can best be grasped in a number of concepts of more ‘aristocratically minded’ languages: solemnidad, ‘solemnity’, gravedad, ‘gravity’, Haltung, ‘composure’, Würde, ‘dignity’. In this regard, Steuckers points to the ‘Roman Form’ that is essential to this existential orientation - an orientation that was largely eliminated from the originally Roman-Catholic Church during the 20th Century aggiornamento that is now associated with Second Vatican Council (1962-65).[37] This Roman Form views ...l’homme... comme un être combattant, un être sans cesse préoccupé de limiter le chaos naturel des choses, de donner forme au réel, de maintenir les continuités constructives léguées par l’histoire... ‘man... as a warrior creature, a creature that is waging an incessant struggle against the chaotic state of the natural [world and that is called upon] to give structure to the reality [around himself and] to maintain the constructive continuities that he has inherited from history...’ (p.41)

This Roman Form is deconstructed in the utterly false ‘anthropological optimism’ of Liberal Normativism, which sets ‘self-made’ - cosmologically ‘autonomous’, sinless ‘free’, morally ‘self-determining’ - ‘modern man’ aside from Divine Creation, the Divine Order and Divine Providence. Liberal Normativism does not offer - cannot offer - any alternative for the Roman Form that it has ‘deconstructed’: Liberal Normativism is an exclusively negative ideology that can only thrive on denial, deconstruction and destruction. In political terms, it represents the abdication of Fortitudo, ‘fortitude’, and its replacement with administrative chaos and legal impunity. In economic terms, it represents the abdication of Temperantia, ‘self-restraint’, and its replacement with greedy materialism and unbridled consumerism. In social terms, it represents the abdication of Castitas, ‘chastity’, and its replacement with public feminization and private immorality. In psychological terms, it represents the abdication of Humilitas, ‘humility’, and its replacement with megalomania and narcissism. Thus, in the sense of Carl Schmitt’s politische Theologie, Liberal-Normativism can be interpreted as the political application of theological antinomianism.

8. The Antinomianist Project of the Hostile Elite

errare humanum est, perservare est diabolicum

[to err is human, to persist is diabolic]

Liberal-Normativism is entirely incompatible with any form of positive (eudaemonic, anagogic) - let alone Traditionalist (holistic, Decisionistic) - philosophy of law or concept of state. Its antinomianism - its pretence to be exempt from Divine Order and the Divine Law - places it outside and under and transcendentally inspired form of philosophy and statecraft. In the words of Robert Steuckers: Le normativisme se place en dehors de tout continuum historique puisque la norme, une fois instaurée, est jugée tout à la fois comme un aboutissement final et comme indépassable et, en théorie, le normativisme exclut toute dérogation au fonctionnement posé une fois pour toutes comme ‘normal’, même en cas d’extrême danger pour les choses publiques. ‘Normativism places itself outside all forms of historical continuity because, as soon as it is installed, its norm achieves the status of necessary and unsurpassable finality. Strictly speaking, normativism excludes any kind of exemption from the once-and-for-always established ‘normal’ functionality [of state power], even if the greater good is threatened in an unprecedented manner.’ (p.35) The epistemological and ontological ‘steel cage’ of Liberal Normativism closes with mathematical precision - in its doctrinal perfection, it wholly excludes all corrective possibilities. In this regard, Steuckers designates the legalism of Liberal Normativism as the ultimate arcanum of Western Postmodernity. This pharisaic legalism guarantees the (mentally preventive) ‘deconstruction’ of all authentic visions of a societas perfecta. It literally rules out the Decisionist (pragmatic, flexible, temporary) Auctoritas that is built into every Traditionalist concept of state power and philosophy of law.

In the chapter La décision dans l’oeuvre de Carl Schmitt, ‘The Decision in the Work of Carl Schmitt’, Steuckers provides a precise analysis of Schmitt’s intellectual Werdegang. He points to the remarkable parallelism between Schmitt’s intellectual development and the 20th Century development of the Liberal-Normativist epistemological-ontological ‘steel cage’. The three phases that Steuckers distinguishes in Schmitt’s work and life can be interpreted as three phases in the development of the antinomian project of the hostile elite, i.e. three phases in the construction of the Liberal-Normativist totalitarian dictatorship that is nearing completion under the aegis of Western Postmodernity. Steuckers names each of these three phases after the historical function of the ‘decision-maker’ - the symbolic personification of highest command power - during the phase in question. In the framework of this essay, which aims at a ‘short anatomy of the ideology of the hostile elite’, it is useful to briefly review each of these three ‘decision makers’ according to an improvised - artificial but investigative - ‘timetable’.

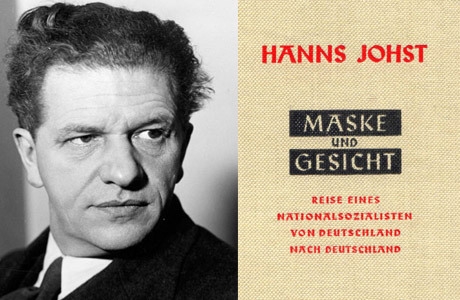

(1) The phase of the Beschleuniger, the ‘Accelerator’, which covers the forty years between two symbolically important years in Western history, viz. 1905, marking the first military-political victory of a non-Western over a Western great power (the Russo-Japanese War) and the ‘constitutionalization’ of the last Traditional Western autocracy (First Russian Revolution), and 1945, marking the final military-political victory by late-modern trans-nationalism (Grossraum, American and Soviet superpower) over the classic-modern nation-state (Lebensraum, Axis powers).[38] This phase is characterized by an ‘engineering ideology’ that allows for a technical acceleration of power, in the sense of a chronological break-through as well as a spatial break-out. Here, ‘1905’ expresses a double breaking-point in terms of significant power expansions in technique (submarine exploration, aviation, ether communication, spectrum analysis) as well as cognition (Einstein’s annus mirabilis, the Weber Thesis, de Saussure’s semiotics, Durkheim’s social fact-finding). The technical suppression of the classic-modern nation-state during this phase starts with an acceleration of sea power (1905 marks the launch of the Dreadnought and the start of the Naval Arms Race) and ends with a break-out into literally supra-terrestrial power: the launch of V-2 Wunderwaffe number MW18014 on 20 June 1944 marks the start of the Space Age and the ‘Trinity Test’ of 16 July 1945 marks the start of the Nuclear Age. It is ironic that the pursuit of revolutionary and transformative forms of power was most explicitly incorporated in the ideologies of the geopolitical losers of 20th Century, viz. in Italian Futurism and in German Technical Idealism.[39] In this regard, Steuckers points to the fact that Schmitt’s legal-philosophical analysis of the economically and technologically motivated Beschleuniger can only be properly understood as an expression of the new ‘titanic’ ontology that is incarnated in German Technical Idealism, i.e. the same ‘spectral’ spirituality that inspires technocrats of the Third Reich such as Albert Speer and Wernher von Braun. The German Technical-Idealist aim of transformative Beschleunigung also characterized the parallel philosophical explorations of Martin Heidegger.[40] Here it should be noted that the search for a way out of the dead-end of Western Postmodernity would benefit from a systematic revaluation of the ideal content of German Technical Idealism - such a revaluation would be much more interesting than the endless ruminations over its ideological weight. A revaluation of German Technical Idealism can proceed from its emphasis on a productive (qualitatively measured) rather than a commercial (quantitatively measured) economy and on an explorative rather than a utilitarian science.

(2) The phase of the Aufhalter, the ‘Inhibitor’, which covers the forty years between the Götterdämmerung of German Technical Idealism and the Promethium Sky over Hiroshima[41] from 1945 till 1985. 1985 is not only the year of Carl Schmitt’s death; it is also symbolically significant as the year after George Orwell’s 1984 and as ‘point of no return’ in anthropogenic global warming - it marks the point at which the Postmodern ‘fall into the future’[42] becomes inevitable and at which all ‘inhibitions’ fail. This phase is characterized by a protracted ‘delaying action’ of the (political, social, cultural) traditional institutions of Western civilization against the rising tide of (doubly technical-industrial and psycho-social mobilized) proto-globalism that starts to flood the Western heartland in 1945. During this phase, these traditional institutions (Monarchy, Church, Nobility, Academy) are gradually pushed back in their role as Katechon. As Aufhalter the Katechon represents the ‘shield of civilization’ that surrounds any Traditional society.[43] Le katechon est le dernier pilier d’une société en perdition; il arrête le chaos, en maintient les vecteurs la tête sous l’eau. ‘The katechon is the last pillar of a society in dissolution: it holds back the [forces of] chaos by holding [its] vectors below the surface.’ (p.10) During this phase, the roots of authentic philosophy of law are gradually cut away: its Ortungen (as expressed in Schmitt’s adage Das Recht ist erdhaft und auf die Erde bezogen, ‘the law derives from the Earth and refers back to the earthly realm’) are abolished in a global process of de-naturalization, de-territorialization and de-location. During this phase, the Katechon institutions are no longer able to stop the literally all-mobilizing but teleologically negative process of globalization - they mere retain a residual function as a temporary inhibitor.[44] The political reflection of this cultural-historical process is found in the deliberate globalist demolition of the nation-state: states and ethnicities are stripped of their sovereign rights and authentic identities. The geopolitical force field is increasingly dominated by an all-mobilizing, all-liquefying and border-less thalassocracy: the all-monetarizing ‘sea power’ that gradually expands outwards from its Atlantic-Anglo-Saxon heartland through tides of money and commerce.[45] Globalist fata morgana’s such as ‘universal human rights’, ‘international law’, ‘free market mechanisms’ and ‘open borders’ are raised to the status of ‘norm’ in the political arena. L’horreur moderne, dans cette perspective généalogique du droit, c’est l’abolition de tous les loci, les lieux, les enracinements, les im-brications. Ces dé-localisations, ces Ent-Ortungen, sont dues aux accélérations favorisées par les régimes du XXe siècle, quelle que soit par ailleurs l’idéologie dont ils se réclamaient. ‘The modern horror that finds expression in this genealogy of law is the eradication of all loci - all placements, all roots [and] all enclosures. These ‘displacements’, these Ent-Ortungen, result from the accelerations that are favoured by all 20th Century regimes, irrespective of the [formal] ideological [discourses] that they claim to represent.’ (p.10)

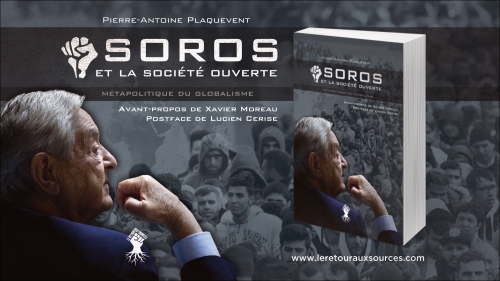

(3) The phase of the Normalisateur, the ‘Normalizer’, approximately coincides with the Postmodern Era. During this phase, the structural inversion of the traditional institutions and values of Western civilization is basically completed. The political-institution and legal-philosophical role of the Katechon, which was previously determined by the positive (anagogic) trajectory of Western civilization is now reversed and replaced by that of the ‘Normalizer’, i.e. by the political-institutional and legal-philosophical ‘anti-christ’ in pursuit of the negative (katagogic) norm of globalist Postmodernity. This is the phase of fully-fledged Liberal Normativism. Steuckers points to the ‘Weimar Standard’ as the ‘factory setting’ of Liberal Normativism: this standard provides, as it were, the ‘sacred’ reference point and the ideal form of secular-bourgeois Liberalism. The thalassocratic ‘New World Order’, enforced by the ‘letter institutions’ (UN, IMF, WEF, EU, NATO), implements this ‘Weimar Standard’ on a global scale, hijacking the technical (digital, virtual) innovations that are now directly linking ‘borderless’ products and services to ‘borderless’ demands and emotions (world wide web, social media, virtual reality). Instability becomes the standard modality in all spheres of life. In the political sphere, ‘open borders’ prevail. In the social sphere, ‘open relations’ prevail. In the psychological sphere, ‘open access’ prevails: relations are reduced to ‘role-playing’, interactions are reduced to narcissist ‘ego communication’ and intimacies are reduced to the ‘pornosphere’. In the cultural sphere, ‘open sources’ prevail: knowledge is reduced to ‘resource management’ and publicity is reduced to ‘(b)log activity’ - Schmitt uses the term Logbücher. The spiritual ‘melt-down’ of Western civilization during this nearly literal new ‘Age of Aquarius’ is a fact. Against this background the role of the ‘Normalizer’ becomes clear. La fluidité de la société actuelle... est devenue une normalité, qui entend conserver ce jeu de dé-normalisation et de re-normalisation en dehors du principe politique et de toute dynamique de territorialisation. Le normalisateur, troisième figure du décideur chez Schmitt, est celui qui doit empêcher que la crise conduirait à un retour du politique, à une re-territorialisation de trop longue durée ou définitive. La normalisateur est donc celui qui prévoit et prévient la crise. ‘The fluidity of society... has [now] become ‘norm’: the [dialectic] process of de-normalization and re-normalization is permanently put beyond the grasp of political power and territoriality. The normalizer, the third avatar of the ‘decision-maker’ in Schmitt[’s work], is appointed to manage all crises in such a way as to prevent any definitive or prolonged return to the [exercise of] political power or re-territorialization. Thus, the normalizer is the one that foresees and prevents such crises.’ (p.14) Effectively, the ‘Normalizer’ is charged with the permanent maintenance of the Liberal-Normativist anti-order: he must prevent the widespread recognition of the Ernstfall and the resulting declaration of a state of emergency. In religious terms, this would be the classical function of the ‘anti-christ’. This ‘Normalizer’ is now incarnated in the hostile elite of the Postmodern West. The functionality of the hostile elite as ‘Normalizer’ explains the extreme forms of its antinomian project: institutional oikophobia, rabid demophobia, politically correct totalitarianism, Orwellian censorship, matriarchal ‘anti-law’, idiocratic anti-education, social deconstruction and ethnic replacement.

9. The Decisionist Alternative

In the beginning of a change the patriot is a scarce man,

and brave, and hated and scorned.

When his cause succeeds, the timid join him,

for then it costs nothing to be a patriot.

- Mark Twain

An answer to the question of whether or not the fast-growing patriotic-identitarian movement in the heavily battered nation-states of the West is able to politically destroy the globalist New World Order in its old heartland will depend on its meta-political - philosophical, ideological - ability to break out of the ‘frame’ of Postmodernity, which was here identified as the ‘steel cage’ of Liberal-Normativism. Within the limited framework of this essay, extensive consideration of this problem is impossible - all that can be done here is to indicate the approximate direction in which this ability must be sought.